*

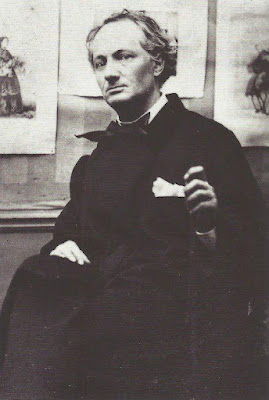

BAUDELAIRE IN THE SIERRAS

High in the Sierras, the ghost of the moon

follows the granite ledge of the lake.

I think of the cursed poet.

It's impossible to like him:

so much suffering is grotesque.

The path leads to the ridge,

then nowhere.

*

Suffering was his true mistress,

his dark opium Muse,

communion of laudanum and cheap wine —

not the mulatto woman

who stole, lied, cheated

with waiters and servants —

What I deplore is her taste.

All his life he begged

his mother for money and love, and did

die in her arms,

paralyzed, mute, syphilitic.

*

The obscenity trial. Artificial Paradises

remaindered at fifty centimes.

The locked mouth, eyes like peepholes.

I feel the terror of a frightened dog.

In a dream, he presents a madam

with a copy of his work.

Mother, is there still time

for us to be happy?

With what an ecstasy of scorn

he must have rolled on his tongue

the slow syllables of sordid.

*

The woman he loves

offers herself to him:

You were a divinity;

now you are only a woman.

Every street is Babylon,

the sky a coffin lid.

No one’s more Catholic than the devil.

He dresses almost like a clergyman.

In a church, admiring the confessionals,

he falls down. The end begins.

*

A branch like green fire

divides the pulsing altitudes.

The prodigious music that rolls across the treetops

sounds to me like the translation of human grief.

What could anyone tell him?

To say yes to life? To look

at lilies and balsam,

these flowers of good,

and eat the world like the body of a god?

Why is he here, in me, asking

is there still time to be happy —

mind burning through Parisian sleet,

nerves stretched like convulsive outlines

of rain-tossed trees along winter boulevards.

His good-boy prayer: every morning to do

my duty promptly, and thus become

a hero and a saint.

Between the granite and the moon,

those eyes with the knowledge of never.

~ Oriana

*

No book saddened me so much as a brief biography of Baudelaire. I couldn't shake it off. It haunted me: his poverty, his humiliation. His hearbreaks haunted me as much as his poem, The Cracked Bell, and Rilke's Washing the Corpse.

*

BAUDELAIRE: THE FIRST MODERN POET

~ Charles Baudelaire was the first modern poet. In both style and content, his provocative, alluring, and shockingly original work shaped and enlarged the imagination of later poets. His influence was not limited to France but spread across Europe and the Americas. His work guided the symbolist movement, which became the dominant school of modernist poetry, and inspired the Decadent and Aesthetic movements. Half a century later, his presence still haunted Surrealism. Nor was Baudelaire’s impact restricted to literature. His ideas on the autonomy of art, the alienation of the artist, the irrationality of human behavior, the intellectualization of poetry, the cult of beauty (and the beauty of evil), and the frank depiction of sexuality became central to modernist aesthetics. He also popularized less exalted cultural trends such as Satanism, sexual degradation, and the use of drugs for artistic inspiration. Not all of these ideas originated with Baudelaire, but his distinctive articulation of these principles became the lingua franca of international Modernism.

For Baudelaire, the goal of poetry is beauty, but beauty is not an end in itself. Through beauty, poetry brings the reader into a new relationship with reality. The experience of beauty changes consciousness; it allows one to perceive qualities and correspondences of things not apprehensible in quotidian existence. There is an almost mystical sense of transcendent consciousness in Baudelaire’s notion of beauty. Art is so ecstatic that it momentarily annihilates the self, freeing human awareness from its ennui and egotism: “In certain almost supernatural states of the soul,” he wrote, “the profundity of life reveals itself, completely in any spectacle, however ordinary it may be, upon which one gazes. It becomes its symbol.” The ecstasy of beauty, in Baudelaire’s poetics, creates a consciousness that apprehends the hidden correspondences between the physical and spiritual realms of existence.

Scholars debate whether Baudelaire’s theory of beauty was meant to be understood in literal or figurative terms. Perhaps here, as so often in his work, Baudelaire endorsed two contradictory ideas at once. He could never replace God in his worldview. (Why else did he need to “revolt” against divine order rather than merely ignore it?) He believed in a numinous supernatural level of reality toward which art aspired. This conviction gave the revelations of beauty an objective quality; one actually participates in something real, even if the experience is difficult to articulate in conceptual terms. To borrow Jacques Maritain’s haunting phrase, beauty represents “the splendor of the secrets of being radiating into intelligence.” From this perspective, beauty has redemptive power; it allows fallen humanity to participate briefly in a mysterious grace.

Now comes the revolutionary twist in Baudelaire’s poetics that gave his work its transfigurative impact on his early readers. If beauty is a heightened form of perception that reveals the occult correspondences of reality, then such intense consciousness can also transform the perception of objects considered ugly or evil. Discovering the beauty in such objects—disease, vice, intoxication, decay—reveals the secret purposes of their troubling existence. If art is to redeem human existence from purposelessness and ennui, then it must develop the capacity to accommodate the sordid and evil aspects of modern life. Art must develop, therefore, a poetics of evil.

Baudelaire saw an essential duplicity in human nature with its “simultaneous allegiances” to both God and Satan. His poetics sought to reconcile their contradictory claims. In this synthesis, his vision represents a secularization of the Christian notion that everything that exists, including evil, serves a divine purpose. Baudelaire relocates the theological concept from God to humanity. Since his poetics is human, it must reflect the duality of fallen humanity, half spirit and half animal. The individual exists in a perpetual tension between the two antithetical forces. “Invocation of God, or Spirituality, is a desire to climb higher,” he wrote in his journals, “that of Satan or animality is delight in descent.” Baudelaire did not conceive of one force without the other; neither was sufficient by itself to encompass reality.

For Baudelaire, beauty exists in an endless dialectic between the spiritual and animalistic elements of human nature. The energy of that dialectic animates Baudelaire’s work. It also explains why his poetry is so difficult to interpret; it does not present static insights but a dynamic relationship between contradictory forces. He believes that art needs to embody and express both the divine and demonic sides of human nature without entirely separating them.

Baudelaire did not seek to go beyond good and evil; he strove to see both clearly as part of the dialectic of reality. He understood the power of ambiguity to express the double nature of the human soul.

In the final lines of “Le Voyage,” Baudelaire brings Les Fleurs du mal to its visionary conclusion. Even on the final journey towards death, the poet rejoices in the “ecstatic prescience” of being fully alive, open to the mysterious beauty of mortal existence:

To plunge to the depths of the abyss, Hell or Heaven, who cares?

https://newcriterion.com/issues/2021/9/baudelaires-modernism

Oriana:

It’s worth it to look at the entire last section of TheVoyage:

Verse-nous ton poison pour qu'il nous réconforte!

*

Pour on us your poison to refresh us!

~ Geoffrey Wagner (slightly modified), Selected Poems of Charles Baudelaire (NY: Grove Press, 1974)

Spleen and the Ideal, agony and ecstasy, constantly juxtaposed — that's Baudelaire.

*

THE FIRE THAT CHANGED AMERICA: THE TRIANGLE SHIRTWAIST FIRE, FRANCES PERKINS, THE SEEDS OF THE NEW DEAL

~ On March 25, 1911, Frances Perkins was visiting with a friend who lived near Washington Square in New York City when they heard fire engines and people screaming. They rushed out to the street to see what the trouble was. A fire had broken out in a garment factory on the upper floors of a building on Washington Square, and the blaze ripped through the lint in the air. The only way out was down the elevator, which had been abandoned at the base of its shaft, or through an exit to the roof. But the factory owner had locked the roof exit that day because, he later testified, he was worried some of his workers might steal some of the blouses they were making.

“The people had just begun to jump when we got there,” Perkins later recalled. “They had been holding until that time, standing in the windowsills, being crowded by others behind them, the fire pressing closer and closer, the smoke closer and closer. Finally the men were trying to get out this thing that the firemen carry with them, a net to catch people if they do jump, the[y] were trying to get that out and they couldn’t wait any longer. They began to jump. The… weight of the bodies was so great, at the speed at which they were traveling that they broke through the net. Every one of them was killed, everybody who jumped was killed. It was a horrifying spectacle.”

By the time the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was out, 147 young people were dead, either from their fall from the factory windows or from smoke inhalation.

Perkins had few illusions about industrial America: she had worked in a settlement house in an impoverished immigrant neighborhood in Chicago and was the head of the New York office of the National Consumers League, urging consumers to use their buying power to demand better conditions and wages for workers. But even she was shocked by the scene she witnessed on March 25.

By the next day, New Yorkers were gathering to talk about what had happened on their watch. “I can't begin to tell you how disturbed the people were everywhere,” Perkins said. “It was as though we had all done something wrong. It shouldn't have been. We were sorry…. We didn't want it that way. We hadn’t intended to have 147 girls and boys killed in a factory. It was a terrible thing for the people of the City of New York and the State of New York to face.”

The Democratic majority leader in the New York legislature, Al Smith—who would a few years later go on to four terms as New York governor and become the Democratic presidential nominee in 1928—went to visit the families of the dead to express his sympathy and his grief. “It was a human, decent, natural thing to do,” Perkins said, “and it was a sight he never forgot. It burned it into his mind. He also got to the morgue, I remember, at just the time when the survivors were being allowed to sort out the dead and see who was theirs and who could be recognized. He went along with a number of others to the morgue to support and help, you know, the old father or the sorrowing sister, do her terrible picking out.”

“This was the kind of shock that we all had,” Perkins remembered.

The next Sunday, concerned New Yorkers met at the Metropolitan Opera House with the conviction that “something must be done. We've got to turn this into some kind of victory, some kind of constructive action….” One man contributed $25,000 to fund citizens’ action to “make sure that this kind of thing can never happen again.”

The gathering appointed a committee, which asked the legislature to create a bipartisan commission to figure out how to improve fire safety in factories. For four years, Frances Perkins was their chief investigator.

She later explained that although their mission was to stop factory fires, “we went on and kept expanding the function of the commission 'till it came to be the report on sanitary conditions and to provide for their removal and to report all kinds of unsafe conditions and then to report all kinds of human conditions that were unfavorable to the employees, including long hours, including low wages, including the labor of children, including the overwork of women, including homework put out by the factories to be taken home by the women. It included almost everything you could think of that had been in agitation for years. We were authorized to investigate and report and recommend action on all these subjects.”

And they did. Al Smith was the speaker of the house when they published their report, and soon would become governor. Much of what the commission recommended became law.

Perkins later mused that perhaps the new legislation to protect workers had in some way paid the debt society owed to the young people, dead at the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. “The extent to which this legislation in New York marked a change in American political attitudes and policies toward social responsibility can scarcely be overrated,” she said. “It was, I am convinced, a turning point.”

But she was not done. In 1919, over the fervent objections of men, Governor Smith appointed Perkins to the New York State Industrial Commission to help weed out the corruption that was weakening the new laws. She continued to be one of his closest advisers on labor issues. In 1929, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt replaced Smith as New York governor, he appointed Perkins to oversee the state’s labor department as the Depression worsened.

When President Herbert Hoover claimed that unemployment was ending, Perkins made national news when she repeatedly called him out with figures proving the opposite and said his “misleading statements” were “cruel and irresponsible.” She began to work with leaders from other states to figure out how to protect workers and promote employment by working together.

In 1933, after the people had rejected Hoover’s plan to let the Depression burn itself out, President-elect Roosevelt asked Perkins to serve as Secretary of Labor in his administration. She accepted only on the condition that he back her goals: unemployment insurance; health insurance; old-age insurance, a 40-hour work week; a minimum wage; and abolition of child labor. She later recalled: “I remember he looked so startled, and he said, ‘Well, do you think it can be done?’”

She promised to find out.

Once in office, Perkins was a driving force behind the administration’s massive investment in public works projects to get people back to work. She urged the government to spend $3.3 billion on schools, roads, housing, and post offices. Those projects employed more than a million people in 1934.

In 1935, FDR signed the Social Security Act, providing ordinary Americans with unemployment insurance; aid to homeless, dependent, and neglected children; funds to promote maternal and child welfare; and public health services.

In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established a minimum wage and maximum hours. It banned child labor.

Frances Perkins, and all those who worked with her, transformed the horror of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire into the heart of our nation’s basic social safety net.

“There is always a large horizon…. There is much to be done,” Perkins said. “It is up to you to contribute some small part to a program of human betterment for all time.” ~ Heather Fox Richardson

I want to see Frances Perkins’s face on some US paper currency. She deserves to have folks look at her face everyday and be reminded of the tremendous contribution she made to our society. ~ Sandra Blevins

Mary: SOMETIMES GREAT CHANGES CAN ONLY BECOME POSSIBLE AFTER GREAT TRAGEDIES

The terrible tragedy of the Shirtwaist Fire may have been what spurred Frances Perkins to work for reforms, but society had to be ready to enact them, to recognize their importance. The horror of that fire, of young people leaping to their deaths from a burning building they could not otherwise escape, was witnessed, experienced, by many as it happened, and by many more as it was reported widely. This was certainly not the first instance of workers’ welfare, and their very lives, being threatened by working conditions, but it was huge, dramatic, and public. It was not the story of one worker's injury, but of many, not over time, but at once. It made an indelible impression on the public, like our own witnessing of falling bodies from the Towers on 9/11.

Perkins' fortuitous contact with Roosevelt became the impetus for his reforms. As with all historical change, part serendipity, part courage and insight, part passion and humanity. The changes not only have to be needed, they have to be seen as needed...then seen as actually possible, before anything is done. Sometimes great changes can only become possible after great tragedies, when pain and outrage make problems clear and impossible to ignore, and there is someone with the passion and courage, and the opportunity, to respond, to act.

Oriana:

I was particularly struck by Mary's invocation of 9/11 as a more recent "indelible event." But the Triangle Fire led to extremely positive changes. The atrocity of 9/11, however, resulted in a severe setback. Now the question of security, not social and economic progress, moved to the foreground, strengthening the conservatives, as always happens when the level of fear escalates.

(One bizarre memory: President Bush's appeal to Americans to show their faith in America by going shopping. Of course that was before we started having mass shootings at shopping malls, among other places.)

And extremely capable people such as FDR and Frances Perkins do not always "happen" when needed. Biden does not have FDR's charisma and has to fight a hard battle against the anti-democratic forces that have become energized since 9/11.

When it came to the improvement of workers' conditions, there were plenty of practical answers. I am certainly glad that Social Security, and later Medicare, became the law of the land, because in today's climate they would have no chance.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jeremy Sherman:

Oriana:

No, life doesn't have a screenwriter, but it seems important to have at least one significant other rooting for our success. Just one person's belief in us can make all the difference.

*

“Literature is essentially loneliness. It is written in solitude, it is read in solitude — and, in spite of everything, the act of reading allows a communication between two human beings.” ~ Paul Auster

Hedy Habra: The Pleasures of Reading

*

HOW WITTGENSTEIN WAS SHAPED BY THE GREAT WAR

~ A young man—not so young as some—is going to war. He is small, aquiline, Jewish, gay, cultivated, and preposterously rich. He speaks the high-toned German of fin-de-siècle Vienna, and has decent enough English to argue with Bertrand Russell, who expects him to take the next big step in philosophy. He is the youngest son of a family ruled with ferocious love by a patriarch, recently dead, who insisted his children live by das harte Muss—the hard must of duty.

Though his late father was one of the wealthiest steelmen in Europe, he has volunteered as a private soldier in an artillery regiment. In his backpack he has a sheaf of notes for a book on philosophy—specifically, the logical form of propositions. When the book is published after the war few will read it, perhaps none will grasp it as its author would wish, but it will make him a metonym for genius, the intellectual counterpart of Caspar David Friedrich’s high peak wanderers. For now he is a citizen of an empire and a soldier in an army that, by the end of the war, will have fallen apart, and after the war he will wear his blue field jacket until it falls apart.

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, first published in German in 1921, is the most formidably opaque work of modern philosophy, but it is more than this. The first English translation, published in 1922, the year of The Waste Land and Ulysses, might easily have been mistaken for a Modernist war poem—in its structure a satire on the bureaucracies and ranks of the war machine, and in its language a meditation on the inexpressible things its author had witnessed as a soldier.

Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. The limits of my language mean the limits of my world. The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem. Even some of the densest passages—“Does ‘~~p’ negate ~p, or does it affirm p—or both?”—could stand for the sheer din of the war, the polyglot hubbub of an Austro-Hungarian barracks or a set of coordinates barked over a barrage.

Marjorie Perloff—the critic who pioneered an aesthetically attentive reading of the Tractatus—argues that “this note of irresolution, this recognition of a mystery that cannot be solved” should lead us to bracket the book with the foundational texts of Modernism. And Ray Monk, Wittgenstein’s biographer, has pointed out that Wittgenstein’s reflections on “ethics, aesthetics, the soul and the meaning of life” are entirely absent from the notes he took to war. The Tractatus as it appeared in 1921 was a confluence of three streams: Wittgenstein’s deeply conflicted sense of duty; his work on logic with Russell; and his time as an artillery observer at the Eastern Front. As he wrote to his nephew years later, “[the war] saved me; I don’t know what I’d have done without it.”

Wittgenstein grew up in a world of duty. He and his contemporaries struggled to work out exactly what was expected of them, as Austrians, as sons and as men, and how on earth they could possibly live up to these diffuse but exacting obligations. Karl, Wittgenstein’s father, took duty to mean obedience, and sought to shape his sons in his own formidable image. Young Ludwig seems to have escaped the full force of his father’s resolve, but it left its mark. His family regarded him as an obliging boy, rather dim, with a certain aptitude for mechanics.

After school Wittgenstein studied aeronautical engineering in England, flying kites on the moors above Manchester, and happened to read Principles of Mathematics—Russell’s attempt, ultimately flawed, to reconstruct mathematics on a foundation of logic. Family connections led to conversations with the German mathematician Gottlob Frege, who suggested a term of study with Russell. From their first encounter in Cambridge in October 1911 the older man and the younger infuriated, impressed, disappointed and astonished one another. Russell, anxious that his own powers were waning, sought an heir. Wittgenstein, consumed with self-doubt, wanted to know if philosophy could be his vocation.

In Cambridge Wittgenstein worked, and harangued his supposed supervisor, and took tea with the undergraduate mathematician David Hume Pinsent, his closest English friend and (perhaps) the first love of his adult life. Within two years he had grown tired of the airlessness of academic philosophy. Seclusion would give him space to write and think, and in autumn 1913 he moved to a cottage beside a fjord in western Norway. He intended to stay until his work was finished, but a summer visit to his family caught him in Vienna in the late summer of 1914.

Why did Wittgenstein volunteer? His chronic hernias could have secured a medical exemption, or a little string-pulling might have obtained a comfortable sinecure in Vienna. Patriotism, in part—though he was always undeceived about the Central Powers’ chance of victory—but most of all his ingrained sense of duty. For so many of his generation August 1914 promised to satisfy their “quest for authenticity and self-fulfilment” (in Perloff’s phrase). Going to war was a kind of experiment, a chance to find out, empirically, what he would become when he faced death. Within two months Private LJJ Wittgenstein was patrolling the Vistula aboard a captured Russian gunboat.

One could write two almost distinct histories of Wittgenstein’s war: the outward story of postings and promotions, battles and retreats; and the war within him, his incessant labor for decency and integrity. His first months of service brought out a monkish aspect, consumed with horror at the cowardice and complacency he found inside himself, and disgusted at the peasant soldiers who were now his equals. After reading The Gospel in Brief, Tolstoy’s recasting of Christ as a visionary teacher, he experienced something like a Christian conversion, one that fed in him a sense of what lay beyond words and the flesh. I am spirit and therefore I am free: what happens to me in the world of events is of little moment compared with the purity of my soul.

If duty is the discipline of living selflessly in the face of mortality, the Tolstoyan pilgrim must always seek closer encounters with death. Dissatisfied with comparatively safe rear-echelon duties, Wittgenstein petitioned for a front-line posting, and in spring 1916 he was sent to the Eastern front with an artillery regiment. Here he volunteered for the most dangerous assignment, as a forward artillery observer, stationed far out in front of his own lines. Within a few weeks of his arrival the Russian army launched the most concentrated offensive of the Eastern war.

Wittgenstein served long days and nights in his dugout; he received medals for his precise reports under vicious bombardment; and, as Monk has observed, his philosophy and his attitude to life were transformed. His recurrent Sorge—anxiety or fear—was replaced with a sense of utter safety. I am spirit and therefore I am free. The austere logician was drawn to reflect on silence, on death, on forms of experience that cannot adequately be put into words. We can see ethical, aesthetic, even religious truths, but we cannot say them, and if we try we will talk nonsense.

As the Russian advance became an Austrian rout he faced another kind of exhausting confrontation, with the limits of his own flesh. Night after night of retreat left him so tired that he almost fell from his horse, and impressed on him that he was, like his comrades and his enemies, only another kind of brute.

Recuperating in Olmütz over the winter of 1916 Wittgenstein befriended the architect-turned-soldier Paul Engelmann. A discussion of Ludwig Uhland’s poem “Count Eberhard’s Hawthorn” provoked Wittgenstein to an insight that seems to anticipate Beckett: “And this is how it is: if only you do not try to utter what is unutterable then nothing gets lost. But the unutterable will be—unutterably—contained in what has been uttered!” Wittgenstein’s outward war had some way to run: he would serve on the Italian front, spend a year in a prisoner-of-war camp, and be driven almost to suicide by the news of Pinsent’s death in an air accident. His inner war, though, was over. For the moment, at least, he had worked out how to say everything that could meaningfully be said.

The young man who came back from the war looked, like so many survivors, much older than his years. He divided his inheritance among his (incredulous and suspicious) siblings, and for a decade or more seemed to want to do anything but philosophy. He taught, brilliantly and imperiously, in an Austrian village school; he tended the monastery garden at Klosterneuburg; he designed a crisp rectilinear townhouse in Vienna for his sister. As in war, so in peace, he sought to immerse himself in duty and, in doing so, to see the vanishing of the problem of life. He returned to philosophy only when he became convinced that silence was not the end of the matter.

https://lithub.com/how-the-war-made-wittgenstein-the-philosopher-he-was/?fbclid=IwAR2zqP8Y4vhv-IndL2Wcc6snYfCWfat7OKKoHnzgF141tPmvhTwyiZK0Sfs

*

“I personally think we developed language because of our deep need to complain.” ~ Lily Tomlin

Oriana:

I think this beats anything Wittgenstein said on the subject of language.

*

“To hold power has always meant to manipulate idiots and circumstances; and those circumstances and those idiots, tossed together, bring about those coincidences to which even the greatest men confess they owe most of their fame.” ~ Alfred de Vigny, Stello

Oriana:

By contrast, I think how much the common soldiers loved Napoleon — because he treated them with respect.

*

TWO MAIN REASONS WHY SOME PARENTS REGRET HAVING CHILDREN

“A small but significant proportion of mothers and fathers wish they’d never had children.”

When American parents older than 45 were asked in a 2013 Gallup poll how many kids they would have if they could “do it over,” approximately 7 percent said zero. In Germany, 8 percent of mothers and fathers in a 2016 survey “fully” agreed with a statement that they wouldn’t have children if they could choose again (11 percent “rather” agreed). In a survey published in June, 8 percent of British parents said that they regret having kids. And in two recent studies, an assistant psychology professor at SWPS University, Konrad Piotrowski, placed rates of parental regret in Poland at about 11 to 14 percent, with no significant difference between men and women. Combined, these figures suggest that many millions of people regret having kids.

Feelings of ambivalence about parenthood aren’t necessarily going to do harm to children. But when regret suffuses the parent-child dynamic, the whole family can suffer. Although the research on parental regret is still nascent, Piotrowski told me, some evidence looking at adolescent mothers suggests an association between regretting parenthood and a harsher, more rejecting attitude toward their children. Kara Hoppe, a family therapist and co-author of Baby Bomb: A Relationship Survival Guide for New Parents, told me her work with patients suggests that children might feel emotional neglect “if the parent consistently really does not want to be there.” Children are so focused on themselves, developmentally, that they can internalize lack of interest from their mother or father as a personal failing, she said.

Though neither Piotrowski’s studies nor the surveys directly asked parents what caused these feelings, experts believe that there are two major pathways to parental regret. One of them is burnout. Parents might be devoted to their children, but feel exhausted and inadequately supported. Some parents used to feel like effective caregivers but ended up facing unexpected responsibilities and saying things like “I’m not cut out to be a mom” and “I love my kids, but I don’t have what it takes.”

Isabelle Rooks, a prominent scholar in parental burnout at Belgium’s Université Catholique de Louvain and a clinician, told me that in this scenario, “they don’t want to be a parent, because they are not able to be the perfect parent.” In one of Piotrowski’s studies, perfectionists were more likely to have trouble seeing themselves as a parent, to burn out in the role, and to experience regret. He also found that severe financial strain, being a single parent, and a history of rejection or abuse in one’s own childhood could contribute to parental regret. Burnout can be temporary and unrelated to regret. But Piotrowski essentially concluded that as the gap between the resources available to a parent and the demands of caring for a child grows, the odds of regret increase.

Not surprisingly, parental burnout has risen during the pandemic, Roskam said. As-yet-unpublished data from a team led by Hedwig van Bakel, a behavioral-science professor at Tilburg University, in the Netherlands, estimated the global prevalence of parental burnout in 2020 at 4.9 percent (up from 2.7 percent in data collected in 2018 and 2019); parents who spent more days in lockdown and had to give more attention to children were particularly affected.

Laura van Dernoot Lipsky, the founder and director of the Trauma Stewardship Institute, told me that she has seen an uptick in parental regret related to the relentlessly taxing events of the past year, and an internalization of the resultant pressure. Parent after parent thinks, “I’m not enough. There’s something wrong with me,” she told me. They’ve started to question their identity as caregivers. Piotrowski pointed me to research showing that parents who are burned out may be more likely to become neglectful or violent toward their children; kids with burned-out parents are more likely to experience symptoms of depression and anxiety.

The other key reason for parental regret is that some parents simply never wanted kids in the first place. Mary is a stay-at-home mother of two in South Dakota. (She also requested to be identified by only her first name, for freedom to discuss the subject.) In 2014, she accidentally became pregnant and experienced a stillbirth. Around the same time, her mentor died by suicide. Feeling that she wanted to prove she could do pregnancy “correctly,” Mary conceived again. “I let hormones and feelings and trauma trick me into having kids,” she told me. When her first son was nine months old, she accidentally became pregnant again.

“I hate it,” Mary said. “I just don’t like kids.” She reads aloud to her children, cooks for them, and generally adheres to textbook parenting strategies for well-adjusted children. But Mary also ruminates about what she could do and who she could be without them, and counts down the days until they’re totally independent. When her friends who have teenagers bemoan their babies’ growing up, she told me, “I’m like, ‘You lucky bitch.’” Roskam said that for many of her parental-burnout patients who regret having children, the feeling is not permanent—but Mary told me that her therapist has ruled out both postpartum depression and burnout. Her regret isn’t a phase.

Orna Donath, an Israeli sociologist and the author of Regretting Motherhood: A Study, confirms this second route to regret. In her research, she interviewed 10 fathers who regretted becoming parents; eight of them reported not wanting children but having them to appease their partner. Some of Donath’s female subjects had supportive partners and the financial resources to raise kids but still felt an “ever-present” burden, she wrote.

Piotrowski concluded that choosing parenthood is a predictor of adapting to it; he noticed apparently higher rates of regret in Poland relative to Germany, which tracked with considerably lower access to abortion in the former. Research from UC San Francisco supports this idea: In one study, mothers with a child born as a consequence of abortion denial were more likely to report having difficulty bonding, as well as feeling trapped or resentful, than mothers who had an abortion and subsequently had a child.

Kara Hoppe has seen this reflected in her adult patients. One woman told her, “I don’t think my mom ever really wanted to be a mom,” and attributed the neglect and abuse she experienced as a child to birth control not yet being available for her mother’s generation. As a kid, however, she thought, “What’s wrong with me?”Some people simply aren’t cut out for raising children, and their kids suffer as a result. But perhaps fewer parents would be regretful if society didn't make parenting so hard. Decreasing parental regret could be possible, with a host of structural shifts: access to reproductive choice as well as individualized treatment for parental burnout and change to policies regarding child care, family leave, work schedules, and the gender pay and promotion gaps.

People might also feel less shame in their regret—and more motivation to address it—if society held more realistic expectations of parents. Women in particular are told that the early years of parenting are tough, but that they will naturally adapt to motherhood; when the sacrifices don’t get easier, that’s supposedly because they’re selfish, damaged, or both. This research tells a different story: Parental regret is the experience of a sizable minority of mothers and fathers. Talking about it could decrease pressure on parents to raise children perfectly, on women to become subsumed by motherhood, or on people to have kids at all. After I spoke with Mary, she sent me an email. “I cried for like an hour after I got off the phone,” she wrote. “I didn’t realize how much I needed to hear that there really are other moms who feel this way.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2021/08/why-parents-regret-children/619931/

Oriana:

So, one main reason is caretaker burnout, and the other is never having wanted to have children to begin with — having become an "accidental parent" or else having given in to pressure from one’s partner.

Still, when a friend told me that a woman said to him that if she could do it over again, she wouldn't have had kids, I was startled. Sure, I realized that sometimes parents wish they could just flush their kids down the toilet, but expressing an outright regret was taboo. That taboo is apparently not as strong now. (Imagine saying something like that in the fifties. But now a woman who says, “I hate being a Mom” has plenty of company on the internet. And the usual response is that it’s perfectly normal — at least from time to time.)

And it’s not all that unusual to stumble across this type of statement: “I really hate to admit this but I hate my children. I feel like they've trapped me in a life that I never wanted. I can't remember the last time I was happy” or “I secretly hate my children, they bring me nothing but torment. It scares me that I could run away and be perfectly okay with leaving them behind.”

https://www.indy100.com/offbeat/parents-hate-their-children-secrets-revealed-whisper-anonymous-confessions-8055601

Oriana:

Practically all my life I noticed is that there is a lot of talk about how motherhood is a great sacrifice and “endless stress,” and very little talk about the pleasures of parenthood. Supposedly society promises the joys of parenthood. What joys? Nobody ever promised me any kind of rose garden. Rather a crown of thorns.

The only pro-parenthood statement that I kept hearing was “If you don’t have a child, later you’ll regret it.”

(I've also read an interesting article about a father's experience of "post-partum depression." He described it as "a deep mourning for the life I used to have, and lost.")

From another source:

~ “I don’t think it was worth it.” Tammy is a mother who wishes she hadn’t been. “Don’t get me wrong, I love my kids. But it comes at a huge cost; mentally, emotionally and physically.” Writing anonymously on feminist website the Vagenda, Tammy says: “My body was ruined, I had to have surgeries later in life to repair what was done to me by forcing an almost 9lb child through my body. And worse yet, it seems as though expressing this honestly makes me a monster ... It seems as though your entire self becomes nothing more than a functional enabler for your kids’ success.”

“Motherhood is no longer an all-encompassing role for women now, it can be a secondary role, or you don’t have to choose it,” says Toni Morrison in Andrea O’Reilly’s Motherhood: A Politics of the Heart. But, she adds, “It was the most liberating thing that ever happened to me.” For Morrison, and countless others, “the children’s demands on me were things that nobody ever asked me to do. To be a good manager. To have a sense of humor. To deliver something that somebody could use. And they were not interested in all the things that other people were interested in, like what I was wearing or if I were sensual. If you listen to [your children], somehow you are able to free yourself from baggage and vanity and all sorts of things, and deliver a better self, one that you like.”

Across cultures and continents, society projects this ideal of motherhood, placing a premium on why mothering matters so much, with a list of things moms must not do: smoke, have casual sex, work instead of taking maternity leave. The biggest taboo, however, is when a mother says that she regrets becoming one at all. Which is why the debate around viral hashtag #regrettingmotherhood has become so intense in recent weeks.

It started with Orna Donath, an Israeli sociologist who decided not to have children and was fed up with being considered an aberration in a country where women have, on average, three children. Last year, Donath published a study based on interviews with 23 Israeli mothers who regret having had children. In it she argues that while motherhood “may be a font of personal fulfillment, pleasure, love, pride, contentment and joy”, it “may simultaneously be a realm of distress, helplessness, frustration, hostility and disappointment, as well as an arena of oppression and subordination”. But the purpose of this study was not to let mothers express ambivalence towards motherhood, but to provide a space for mothers who actually have “the wish to undo motherhood”, something that Donath describes as an “unexplored maternal experience”.

Donath’s study sparked a stormy debate. In Germany alone, novelist Sarah Fischer published Die Mutterglück-Lüge (The Mother-bliss Lie), with the subtitle Regretting Motherhood – Why I’d Rather Have Become a Father; writers Alina Bronsky and Denise Wilk analyzed the irreconcilable realities of Germany’s traditional mother image and modern-day demands of working environments in their book The Abolishment of the Mother; while leading German columnist Harald Martenstein wrote that these “motherhood regretters” are committing child abuse if they confront their own children with their negative feelings about motherhood (even if they also say that they love their children, as most of these mothers do). To Martenstein, regretting motherhood is the result of naive black-and-white thinking: a product of unrealistic expectations, the wrong partner, the mother’s personality and perfectionism. To him, it’s as pointless as crying over spilt milk.

“The ideological impetus to be a mother,” as Donath describes it, can be found across all walks of society and is founded on the powerful conception that complete female happiness can only be achieved through motherhood. Those who seek to challenge this narrative face overwhelming opposition, which makes an honest, open debate difficult.

It doesn’t seem to matter that mothers who regret the maternal experience almost always stress that they love their children.

Donath speaks of the ideological promises made to prospective mothers about the joys of raising children, and of the “simultaneous delegitimization of women who remain childless”, who are reckoned to be “egoistic, unfeminine, pitiful and somehow defective”.

Over on Mumsnet, multiple threads exist with women mourning the loss of their old lives and battling with the daily reality of motherhood.

“It is not post-natal depression,” writes one user. “I am not depressed or ‘down’. No doubt someone will try to convince me it is, just like unhappy Victorian ladies were labelled as mentally ill when they were desperately unhappy with the lives society gave them. I am perfectly happy with my life, or rather, I was. My son is perfectly lovely, and my partner is extremely helpful. I adore them both. And, no, I wasn’t pressured into it, either. I was in love with the idea. I thought it was what I wanted. Society told me it was what I wanted, right?”

I am a mother, too, and while I don’t regret it, I can deeply sympathize with women who feel betrayed by the eternal myth that enjoying motherhood is a biological predisposition. And I wonder if I would have chosen to be a mother had I not been indoctrinated all my life to believe that motherhood is the only thing that will complete my happiness. I’m not so sure.

Donath’s aim is simple: she wants to allow mothers to live motherhood as a subjective experience, one that can combine love and regret, one that will be accepted by society, no matter how it looks.

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/may/09/love-regret-mothers-wish-never-had-children-motherhood

Oriana:

“Being a mother is the most difficult thing in the world,” is another thing I used to hear pretty frequently. And no one ever disagreed. Still, I remember how one woman I met at arts colony said, “Motherhood is the most difficult thing in the world, but it’s also the most rewarding.” Maybe not for all women, but probably for a great many.

Also, there are countries in Europe whose higher birth rate suggests that parenthood isn’t as stressful. France and Sweden are examples. They appear to have discovered the best way is to actively help parents raise their children by providing affordable child care. They provide financial incentives as well, but so do many other countries where the the birth rate is very low. The answer seems to be the availability of child care. Parents need help, and grandparents my live far away or be too beset with ill health to help. I am happy to see that going to preschool is finally being perceived as normal.

In addition, I believe in Helen Hay’s observation: “We are the victims of victims.” (This idea has also be stated as "Hurt people hurt people.") Parents who can’t endure their children may not be good at coping with stress in general, due to their own stressful childhood. Such people need a healing relationship first. They need a lot of love. The most reliable source? A dog.

Mary:

It seems to me I always knew I never wanted to be a mother, and this was a reaction to watching my own mother. She had seven children fairly close together. I am the oldest; the last came along when I was thirteen. I and my sisters became caregivers to the youngest, but what affected me most was simply watching my mother work. Every day but Sunday, huge loads of washing done with a wringer washer and strung clothesline, three meals a day, every day, scrubbing the floors, washing the windows, ironing for hours (no permanent press in those days). All this with only the help of the three oldest, and no thanks from anyone. Her only luxury came for an hour or so in the evening, after all were in bed, and she could read without interruption. I loved my mother, but I didn't want to be her.

Oriana:

Being overwhelmed with practical chores and decisions seems, the never-ending trivialities of living with small children — the unappetizing side of parenting is hard not to witness. And you’re not the first woman to testify that taking care of younger siblings when growing up greatly diminishes (or even extinguishes) the desire for motherhood.

Of course there is a sadness too — ideally, motherhood should be a joy, and not a soul-crushing drudgery. For a long time now, there has been talk about “affordable child care.” I wonder if that will happen within our lifetime. It seems to have happened in France, Holland, and the Scandinavian countries. The US would have to severe re-evaluate its budget priorities. This won’t happen unless there is a crisis.

*

THE UNITED STATES AS A SETTLER STATE

~ The United States has never been “a nation of immigrants.” It has always been a settler state with a core of descendants from the original colonial settlers, that is, primarily Anglo-Saxons, Scots, Irish, and Germans. The vortex of settler colonialism sucked immigrants through a kind of seasoning process of Americanization—not as rigid and organized as the “seasoning” of Africans, which rendered them into human commodities, but effective nevertheless.

In the 1960s, U.S. historians were having to adjust the historical narrative of the white republic and progress in response to Black civil rights demands for a reckoning about racism. But in the process of those adjustments and reforms, the settler state was never a subject of debate. Mahmood Mamdani writes:

If America’s greatest social successes have been registered on the frontier of race, the same cannot be said of the frontier of colonialism. If the race question marks the cutting edge of American reform the native question highlights the limits of that reform. The thrust of American struggles has been to deracialize but not to decolonize. A deracialized America still remains a settler society and a settler state.

Mamdani correctly observes that the very existence of Indigenous nations “constitutes a claim on land and therefore a critique of settler sovereignty and an obstacle to the settler economy.”

Multiculturalism was the response to civil rights demands, which required a revised narrative of U.S. history. For this scheme to work—and affirm U.S. historical progress—Indigenous nations and communities had to be left out of the picture or somehow woven into the story. As territorially and treaty-based peoples in North America, they do not fit the grid of multiculturalism, but were included by transforming them into an inchoate, oppressed racial group, while oppressed Mexican Americans and colonized Puerto Ricans were dissolved into another such group, variously called “Hispanic” or “Latino,” and more recently “Latinx.” The multicultural approach emphasized the “contributions” of oppressed groups and immigrants to the United States’ presumed greatness. Indigenous peoples were thus credited with contributing corn, beans, buckskin, log cabins, parkas, maple syrup, canoes, hundreds of place names, ecology, Thanksgiving, and even contributing to the Constitution the concepts of democracy and federalism.

This idea of the gift-giving Indian helping to establish and enrich the development of the United States is a screen that obscures the fact that the very existence of the country is a result of the looting of an entire continent and its resources, reducing the Indigenous population, and forcibly relocating and incarcerating them in reservations. The fundamental unresolved issues of Indigenous lands, treaties, and sovereignty could not but scuttle the premises of multiculturalism for Native Americans. Multiculturalism persisted into the neoliberal twenty-first century, culminating in widespread “diversity” training, the coining of a new term, “people of color,” and the production of Hamilton, which not only erased the Indigenous peoples and African slavery but also turned the white founding fathers, who authored a Constitution that recognized only white people as citizens, into brown and Black men.

The Black Power and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s gave birth to “identity politics,” which saw the coalescence of Mexican American youth as Chicanos, Native American Red Power, and a trans-Asian Pacific American identity. A generation that came to adulthood in the 1960s who could not speak Chinese or Spanish, as their immigrant parents felt it might hold their children back, embraced bilingualism. European immigrants or second-generation U.S. Americans, whose parents and grandparents had strived so hard to be considered white, saw the cultural power of whiteness diminishing and began to hyphenate their identity as Polish American, Italian American, and Irish American, while white Appalachians and New Mexico Hispano settlers claimed indigeneity. Instead of the melting pot that erased ethnic heritage, there was talk of patchwork quilts and threads, multiculturalism and diversity.

Immigration in the new millennium looked different from past immigration in that Asia was the major region of origin rather than Latin America, at 41 percent of all immigrants, with 38.9 percent from Latin America, primarily Mexico. Between 2000 and 2017, the top three countries of origin were China, India, and Pakistan, followed by the Philippines. Most importantly, nearly half of the new immigrants were college graduates, many with advanced degrees. They were not heading only to Silicon Valley or other high-tech industrial centers, nor were they, as had immigrants in the past, settling mainly in the large coastal cities. Rather, they could be found in the Deep South, the Great Plains, the intermountain West, and Appalachia. In North Dakota, where immigrants represented about 4 percent of residents, immigrant numbers increased by 87 percent after 2010, while West Virginia and South Dakota increased in foreign- born residents by a third, and Kentucky and Tennessee by over a fifth.

And many of these immigrants—some of whom were refugees, others undocumented—came not only from South, West, and East Asia but also from African and Arab countries, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. Like the Chinese and Mexican immigrants before them, they experienced racialization, thereby lacking a key element of settler colonialism: potential whiteness. They or their children could become thoroughly Americanized but still remain contingent, even the son of a Kenyan who was twice elected president but whose citizenship was questioned by a substantial part of the population, including by the president who followed him.

The trend of “third world” immigration began with the 1965 immigration law, but accelerated with the Western nations’ retreat from funding and supporting decolonization and nation-building, which accelerated debt, austerity, and famine, and, in the case of the United States, fronting and arming counterinsurgencies, making the countries of origin unlivable. Suketu Mehta immigrated with his family from Mumbai at age fourteen. A prize-winning author and associate professor of journalism at New York University, he observes in his book This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto (2019) that “they are here because you were there.” He corrects the idea that immigrants clamor to leave their homelands to pursue the American Dream.

When migrants move, it’s not out of idle fancy, or because they hate their homelands, or to plunder the countries they come to, or even (most often) to strike it rich. They move—as my grandfather knew—because the accumulated burdens of history have rendered their homelands less and less habitable.

Mehta points out that migrants, as we have seen with Mexican and Philippine migrants, send back to their home countries some $600 billion in remittances every year, amounting to four times more than all the Western foreign aid and a hundred times more than the amount of all debt relief. In addition to the ruin wrought by European colonization and U.S. wars and interventions, plus extreme economic inequality, Mehta sees catastrophic climate change as a source of mass migrations in the twenty-first century, displacing far more people than were displaced at the end of World War II. By 2050 up to 30 percent of the planet’s surface could be unlivable desert, forcing a 1.5 billion people into migration. In Bangladesh alone, 20 million people could be forced out due to rising sea levels, and by the end of the century, the lands of 650 million people could be underwater. Obviously, rich countries will be increasingly a destination for desperate migrants and need to plan to provide assistance, not build walls or increase mass deportations.

Mehta’s manifesto is deeply researched and insightful and should be a refreshing rejoinder to the American Dream and bootstrap stories that many immigrants, and more Anglo settlers, are asked to tell themselves. But Mehta does characterize the United States as “a nation of immigrants” that does not live up to that aspiration. Although he is critical of U.S. imperialism and immigration policies, Mehta does not acknowledge settler colonialism and the immigrant’s role in perpetuating it. The Native is mentioned as an oppressed demographic, but otherwise is invisible.

The migrant to the United States or other states structured on settler colonialism—Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Israel—is susceptible, as Saranillio points out, to the ideology of settler colonialism, which in the United States is imprinted in the content of patriotism and Americanism. Without consciousness of and resistance to this pull, the migrant can passively contribute to the continued settler-colonial order. The desire to relieve the non-European migrant or descendants of enslaved Africans from responsibility is understandable but not sustainable if the settler-colonial foundation is to be eradicated—that is, the decolonization of the entire apparatus of the settler state. What would that entail? U.S. social movement organizer Clare Bayard likely captured the dilemma for most non-Indigenous activists in the United States, saying: “The difficulty that a lot of non-Native people have in imagining what unsettling would look like in this country is that it’s not seen as a political possibility. We can’t even imagine what that would look like—how do we do that?” ~

https://bostonreview.net/race/roxanne-dunbar-not-nation-immigrants?utm_source=Boston+Review+Email+Subscribers&utm_campaign=66bd1e8bd6-MC_roundup_8_30_21&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_2cb428c5ad-66bd1e8bd6-40729829&mc_cid=66bd1e8bd6&mc_eid=97e2edfae1

Oriana:

The article makes some valid points, but — what is to be done? Obviously we can’t ask all people with Irish last names to “go back” to Ireland, the people with Italian last names to go to Italy, and so on. Even first-generation Americans become fairly automatically rooted in their new country, and after ten years or so, when they visit their homeland, they are likely to feel different from those who never left, not to mention that the country itself has changed (I'll never forget my shock when I saw that a former bookstore near where I used to live had become a shoe store!)

Those who left no longer really fit in with their relatives; nor does the home country fit them. And their children are American through-and-through, and consider themselves lucky to have been born in this country. They can’t imagine any other life.

History is mostly not reversible. Even the Native Americans originally came from somewhere else — in their case, probably northeastern Asia (Siberia). Would any sane person insist that they go back to Asia? Or that Afro-Americans try to settle back in Africa?

No. The only solution that makes sense is tolerance, acceptance, equal rights — and a deep appreciation of the many different cultures that have contributed to the building of this country.

Mary: HISTORY IS IRREVERSIBLE

On being a "settler nation" and colonialism, I can only echo "what can be done?" While it is essential to understand the injustices of history, that history is itself irreversible. The only way to move is into the future, the only way to heal is to remove those injustices for the future. This takes not only effort but imagination, especially in a world that has marginalized and mythologized the indigenous nations, and doesn't admit to its own colonialism. The impetus for change here comes from that marginalized population, not from any crisis of conscience in the "settler" or immigrant"groups.

No one can go back. Not to their ancestral countries of origin, as recent waves of immigration came not so much out of desire to be here as the impossibility of remaining at home..whether due to the effects of political oppression or climate change — and refugees from lands made uninhabitable by climate change are sure to keep increasing. Injustices cannot be undone by recapturing a past, especially a mythologized past. It is interesting to watch as people construct a bridge to the future from their talents, intelligence and imagination. For instance, there are Native Americans who are creating a place for themselves, a bridge between their culture and the larger world, in the realm of couture, of high fashion. Their work is beautiful and astounding, and making quite an impact already.

Oriana:

No, history is not reversible. It can only move forward, toward another stage of development — where each ethnic culture contributes its richness.

*

A FOUR-DAY WORKWEEK IS COMING

In 1886, the standard workweek in the United States consisted of six, ten-hour days. On May 4th of that year, a riot took place in Chicago after an unknown person threw a bomb at officers trying to break up a peaceful rally in favor of the then-radical notion of an eight-hour work day. While it took a few more decades to get there, today, the eight-hour workday seems quite natural.

Today, the discussion centers around the possibility of a further cut in the workweek, from five days to four days. Joining the pile of studies on this topic is a new report out of Iceland documenting the recent success of one of the largest experiments to date on a reduced workweek. Carried out by the Icelandic government and published by Autonomy, a UK think tank, the report suggests that a substantial portion of the economy could switch over to a short workweek tomorrow with little in the way of negative effects.

AN EXPERIMENT IN ICELAND

Icelandic workers spend more hours per year in the office than do those of several other European nations and can be less productive during that time than some of those other workers. The experiment was designed in hopes of meeting the work-life balance of Icelanders, improving productivity in the workplace, and providing a route for bringing hours in line with their neighbors.

The first of the trials was carried out by Reykjavík's city government between 2014 and 2019 at a few government offices and service centers. The trials eventually expanded to include more than 2,500 workers at "playschools, city maintenance facilities, care-homes for people with various disabilities and special-needs, and beyond.”

Workers in the experimental locations saw their hours reduced from 40 to 36 or 35 hours per week with no loss in pay. The exact way these hours were organized was determined by the individual workplace involved. Many opted to split the hours among four days, while others worked a five-day week with one workday being shorter.

A second trial was carried out by the Icelandic national government at about the same time, starting in 2017 and ending in 2021. This involved 17 workplaces across the country.

Both studies produced similar results. The reduction in hours caused either no change or an increase in productivity and improvements in the reported work-life balance of employees. While many employees were concerned that more work would be crammed into less time, the data show that the workers were actually working less.

Improvements in efficiency were found in every workplace. Employees worked faster. Time-wasting events, like unnecessary meetings, were curtailed. Routines were changed to be more efficient, and shifts and schedules were restructured. Overtime was needed in some offices, but only sparingly.

Importantly, services were provided at the same levels as they were before the reduction in work hours. The well-being of workers dramatically improved, with many reporting increased time with their families, lower stress levels, and a better ability to balance their work and home lives.

The two trials included more than 1 percent of Iceland's workforce. Thanks to its success, 86 percent of Icelandic workers are on contracts that either reduce their workweek or grant them the right to reduce their workweek in the future.

The idea of a four-day workweek or reduced hours with no cut in pay is being discussed and tested in many places. The six-hour day has been tried in Sweden to great fanfare. Offices in New Zealand saw dramatic gains in productivity after switching to a shorter week. Microsoft tried a four-day week in Japan and got similar results.

Indeed, the results from Iceland are typical. Anna Coote, principal fellow at the New Economics Foundation, explained in an email to BigThink how the report was well in line with previous studies: "It confirms other evidence that reduced working time is popular with employees, provided there is no loss of pay. It also confirms the importance of combating low pay at the same time as moving towards shorter working hours. A four-day week (or its equivalent in hours) must benefit lower income groups, not just those on higher pay. No one should have to work long hours just to keep a roof over their head and food on the table.”

In the book The Case for a Four Day Week, Coote and her co-authors examine the impact of a four-day workweek on society. They foresee a number of changes for society at large.

For example, it is still the case that women do more housework than men. However, the Iceland experiments showed that men in the study performed a larger share of household duties due to spending less time at the office. A four-day week could also benefit the environment through wasting less energy and fewer commutes.

In an email to Big Think, Coote reminds us that a "new normal" may be coming: "What is 'normal' is not natural or heaven sent — it is constructed over time by human-made structures and systems. Yesterday's 'normal' was a 10-hour day. Working people won the right to an eight hour day through a protracted struggle over many years of social and economic change. Tomorrow's 'normal' is likely to be a 4-day week or its equivalent in hours across a week, month, year or lifetime.”

If the four-day workweek indeed becomes the norm, we all owe a debt of gratitude to Iceland. ~

https://bigthink.com/politics-current-affairs/four-day-week-

The 40-hour work week was introduced in 1938. It’s indeed time to experiment with different schedules. While we are certainly not anywhere near the 15-hour week predicted long ago, perhaps the eventual result will be different hours for different people. For some, shorter is better, but I suspect there’ll always be those — and not just the self-employed — who will choose to work extra hours and days. That’s their way of thriving.

*

DID JESUS REALLY EXIST? HISTORY MYTHICIZED OR MYTH HISTORICIZED?

Most antiquities scholars think that the New Testament gospels are "mythologized history." In other words, based on the evidence available they think that around the start of the first century a controversial Jewish rabbi named Yeshua ben Yosef gathered a following and his life and teachings provided the seed that grew into Christianity. At the same time, these scholars acknowledge that many Bible stories like the virgin birth, miracles, resurrection, and women at the tomb borrow and rework mythic themes that were common in the Ancient Near East, much the way that screenwriters base new movies on old familiar tropes or plot elements. In this view, a "historical Jesus" became mythologized.

For over 200 years, a wide ranging array of theologians and historians grounded in this perspective have analyzed ancient texts, both those that made it into the Bible and those that didn't, in attempts to excavate the man behind the myth. Several current or recent bestsellers take this approach, distilling the scholarship for a popular audience. Familiar titles include Zealot by Reza Aslan and How Jesus Became God by Bart Ehrman.

By contrast, other scholars believe that the gospel stories are actually "historicized mythology." In this view, those ancient mythic templates are themselves the kernel. They got filled in with names, places and other real world details as early sects of Jesus worship attempted to understand and defend the devotional traditions they had received.

The notion that Jesus never existed is a minority position. Of course it is! says David Fitzgerald, the author of Nailed: Ten Christian Myths That Show Jesus Never Existed at All. Fitzgerald points out that for centuries all serious scholars of Christianity were Christians themselves, and modern secular scholars lean heavily on the groundwork that they laid in collecting, preserving, and analyzing ancient texts. Even today most secular scholars come out of a religious background, and many operate by default under historical presumptions of their former faith.

Fitzgerald–who, as his book title indicates, takes the "mythical Jesus" position–is an atheist speaker and writer, popular with secular students and community groups. The internet phenom, Zeitgeist the Movie introduced millions to some of the mythic roots of Christianity. But Zeitgeist and similar works contain known errors and oversimplifications that undermine their credibility. Fitzgerald seeks to correct that by giving young people accessible information that is grounded in accountable scholarship.

More academic arguments in support of the Jesus Myth theory can be found in the writings of Richard Carrier and Robert Price. Carrier, who has a Ph.D. in ancient history uses the tools of his trade to show, among other things, how Christianity might have gotten off the ground without a miracle. Price, by contrast, writes from the perspective of a theologian whose biblical scholarship ultimately formed the basis for his skepticism. It is interesting to note that some of the harshest critics of popular Jesus myth theories like those from Zeitgeist or Joseph Atwill (who argued that the Romans invented Jesus) are academic Mythicists like these.

The arguments on both sides of this question—mythologized history or historicized mythology—fill volumes, and if anything the debate seems to be heating up rather than resolving. Since many people, both Christian and not, find it surprising that this debate even exists—that serious scholars might think Jesus never existed—here are some of the key points that keep the doubts alive:

1. No first century secular evidence whatsoever exists to support the actuality of Yeshua ben Yosef.

In the words of Bart Ehrman (who himself believes the stories were built on a historical kernel):

"What sorts of things do pagan authors from the time of Jesus have to say about him? Nothing. As odd as it may seem, there is no mention of Jesus at all by any of his pagan contemporaries. There are no birth records, no trial transcripts, no death certificates; there are no expressions of interest, no heated slanders, no passing references – nothing. In fact, if we broaden our field of concern to the years after his death – even if we include the entire first century of the Common Era – there is not so much as a solitary reference to Jesus in any non-Christian, non-Jewish source of any kind. I should stress that we do have a large number of documents from the time – the writings of poets, philosophers, historians, scientists, and government officials, for example, not to mention the large collection of surviving inscriptions on stone and private letters and legal documents on papyrus. In none of this vast array of surviving writings is Jesus' name ever so much as mentioned." (pp. 56-57)

2. The earliest New Testament writers seem ignorant of the details of Jesus' life, which become more crystalized in later texts.

Paul seems unaware of any virgin birth, for example. No wise men, no star in the east, no miracles. Historians have long puzzled over the "Silence of Paul" on the most basic biographical facts and teachings of Jesus. Paul fails to cite Jesus' authority precisely when it would make his case. What's more, he never calls the twelve apostles Jesus' disciples; in fact, he never says Jesus HAD disciples –or a ministry, or did miracles, or gave teachings. He virtually refuses to disclose any other biographical detail, and the few cryptic hints he offers aren't just vague, but contradict the gospels. The leaders of the early Christian movement in Jerusalem like Peter and James are supposedly Jesus' own followers and family; but Paul dismisses them as nobodies and repeatedly opposes them for not being true Christians!

Liberal theologian Marcus Borg suggests that people read the books of the New Testament in chronological order to see how early Christianity unfolded.

Placing the Gospels after Paul makes it clear that as written documents they are not the source of early Christianity but its product. The Gospel — the good news — of and about Jesus existed before the Gospels. They are the products of early Christian communities several decades after Jesus' historical life and tell us how those communities saw his significance in their historical context.

3. Even the New Testament stories don't claim to be first-hand accounts.

We now know that the four gospels were assigned the names of the apostles Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, not written by them. To make matter sketchier, the name designations happened sometime in second century, around 100 years or more after Christianity supposedly began.

For a variety of reasons, the practice of pseudonymous writing was common at the time and many contemporary documents are "signed" by famous figures. The same is true of the New Testament epistles except for a handful of letters from Paul (6 out of 13) which are broadly thought to be genuine. But even the gospel stories don't actually say, "I was there." Rather, they claim the existence of other witnesses, a phenomenon familiar to anyone who has heard the phrase, my aunt knew someone who . . . .

4. The gospels, our only accounts of a historical Jesus, contradict each other.

If you think you know the Jesus story pretty well, I suggest that you pause at this point to test yourself with the 20 question quiz at ExChristian.net.

The gospel of Mark is thought to be the earliest existing "life of Jesus," and linguistic analysis suggests that Luke and Matthew both simply reworked Mark and added their own corrections and new material. But they contradict each other and, to an even greater degree contradict the much later gospel of John, because they were written with different objectives for different audiences. The incompatible Easter stories offer one example of how much the stories disagree.

5. Modern scholars who claim to have uncovered the real historical Jesus depict wildly different persons.

They include a cynic philosopher, charismatic Hasid, liberal Pharisee, conservative rabbi, Zealot revolutionary, and nonviolent pacifist to borrow from a much longer list assembled by Price. In his words (pp. 15-16), "The historical Jesus (if there was one) might well have been a messianic king, or a progressive Pharisee, or a Galilean shaman, or a magus, or a Hellenistic sage. But he cannot very well have been all of them at the same time." John Dominic Crossan of the Jesus Seminar grumbles that "the stunning diversity is an academic embarrassment.”

For David Fitzgerald, these issues and more lead to a conclusion that he finds inescapable:

Jesus appears to be an effect, not a cause, of Christianity. Paul and the rest of the first generation of Christians searched the Septuagint translation of Hebrew scriptures to create a Mystery Faith for the Jews, complete with pagan rituals like a Lord's Supper, Gnostic terms in his letters, and a personal savior god to rival those in their neighbors' longstanding Egyptian, Persian, Hellenistic and Roman traditions.

In a soon-to-be-released follow up to Nailed, entitled Jesus: Mything in Action, Fitzgerald argues that the many competing versions proposed by secular scholars are just as problematic as any "Jesus of Faith:”

Even if one accepts that there was a real Jesus of Nazareth, the question has little practical meaning: Regardless of whether or not a first century rabbi called Yeshua ben Yosef lived, the "historical Jesus" figures so patiently excavated and re-assembled by secular scholars are themselves fictions.

We may never know for certain what put Christian history in motion. Only time (or perhaps time travel) will tell. ~

https://www.alternet.org/2021/08/historical-jesus/

Oriana:

My own personal view: I don’t know. But even if he existed, the legend had so overgrown whatever may have really happened that it’s impossible at this point to separate myth from history. Of course his mother had to be a virgin — gods and human virgins have a long history. Of course he had to be born in Bethlehem, the City of David — but no census in history has ever required that people travel to the city of their birth; the very idea is absurd. There was no slaughter of the innocents, no return from Egypt — that’s a mythic echo of Moses and exodus. And so on and so on. There are several books on the subject, including Bishop Spong's excellent and Jesus-friendly Jesus for the Non-Religious.

Still, while so much in the Gospels is certainly pure invention, there may be a kernel of historicity that can’t be easily dismissed. One commentator on Amazon, Paul Clark, summarizes it: “There are some facts in the Gospels that are very inconvenient for early Christians, among them Jesus coming from Nazareth, his baptism by John (for the washing away of his sins) and the fact that he was crucified. The authors would never have put these things in if they didn’t believe them to be true.”

Likewise, Bart Ehrman’s interpretation of Jesus as a leader of an apocalyptic cult makes a lot of sense (e.g. the insane-sounding statements such as “Let the dead bury the dead”).

I also further agree with Paul Clark's assessment of Bart Ehrman: ” Like most critical scholars, he places Jesus firmly within the traditions of Jewish apocalyptic thinkers who believed that the world as we know it was about to end. Jesus was a man of his time and place, not the man of Christian myth, and he didn’t have anything much to say to us about the issues we face today. This, he says, is what atheists should concentrate on, not on mythicist claims that are entirely without merit.”

But ultimately, what I what like instead of a debate of the actual existence or non-existence of Jesus would be a deep debate over the teachings of Christianity. First of all, what are they? It seems to me that there is no clear layout of 1, 2, 3 etc, that practically all scholars and Christians would agree on. For instance, is Satan, the Prince of Air, the real ruler of the world? Do Satan and God have a contract dividing their powers, a sort of Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact? Is everyone some version of Job, being stress-tested? (You can see that I was indoctrinated with the toxic “God-of-Punishment” Catholicism.)

Or, to pass to the ethical teachings, are we really supposed to take no thought of tomorrow, sell all our possessions, and give the money tot he poor? What about turning the other cheek? How come we don’t see the examples of such behavior?

Then, once we know what the teachings are, let’s discuss if they make sense. I would welcome any discussion of ethics, and we don’t even have to call them “Christian ethics.”

John Guzlowski: