WAITING FOR THE BARBARIANS

What are we waiting for, assembled in the forum?

The barbarians are due here today.

Why isn’t anything going on in the senate?

Why are the senators sitting there without legislating?

Because the barbarians are coming today.

What’s the point of senators making laws now?

Once the barbarians are here, they’ll do the legislating.

Why did our emperor get up so early,

and why is he sitting enthroned at the city’s main gate,

in state, wearing the crown?

Because the barbarians are coming today

and the emperor’s waiting to receive their leader.

He’s even got a scroll to give him,

loaded with titles, with imposing names.

Why have our two consuls and praetors come out today

wearing their embroidered, their scarlet togas?

Why have they put on bracelets with so many amethysts,

rings sparkling with magnificent emeralds?

Why are they carrying elegant canes

beautifully worked in silver and gold?

Because the barbarians are coming today

and things like that dazzle the barbarians.

Why don’t our distinguished orators turn up as usual

to make their speeches, say what they have to say?

Because the barbarians are coming today

and they’re bored by rhetoric and public speaking.

Why this sudden bewilderment, this confusion?

(How serious people’s faces have become.)

Why are the streets and squares emptying so rapidly,

everyone going home lost in thought?

Because night has fallen and the barbarians haven't come.

And some of our men just in from the border say

there are no barbarians any longer.

Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

Those people were a kind of solution.

~ C. P. Cavafy; Russian translation by Nina Kossman, reverse translation by Facebook

*

"I am here to be mad, not to write.”

Robert Walser, a brilliant writer deeply relevant to our times, who spent the last twenty-seven years of his life in a mental institution, responding to visiting journalist's question as to why he was not writing anymore.

In “The Walk,” his most famous short story, he describes a stroll through a rural landscape in the minutest of fantastic and tragically funny detail. Here he is, on that walk from Herisau to Wil, Austria, in 1939.

At seventy-eight, he disappeared from that mental asylum in Herisau and later was found dead in the snow.

*

ONE PERSON’S REACTION TO SEEING THE VIDEO COMPILATION OF OCTOBER 7 ATROCITIES

~ Truthfully, I did not want to be asked to come. But I also knew that if I were asked, I would have to go. To bear witness.

Here are my initial thoughts:

1. The joy, the gleeful laughter, the depraved happiness over killing Jews. The exclamations of celebration over death and pain. The callousness, inhuman pleasure and amusement over slaughtering innocent lives. The shameless brutality. These are monsters. They can never be rehabilitated. They can never be forgiven.

2. The systematic, organized, methodical approach to killing. Go back and shoot this person in the head. Make sure those girls are dead. The organization of mass killing. We’ve seen this before: organized chains of command, strong communications, uniforms.

3. The Gazan ‘innocent civilians’ who came over the border in the third wave that morning, to loot, rape, kill, and capture bodies, live and dead, for Hamas rewards. And the joy of the ‘innocent civilians’ who rejoiced in the streets as hostages and bodies were paraded in the streets. The cheering. The spitting and kicking and beating. The hate. The cruelty. The social acceptance of kidnapping and killing Jews in Palestinian society.

There are images seared into my brain that haunt me now.

The two boys seeing their father killed, watching as a terrorist takes a bottle of coke out of their fridge.

The tortured and raped young girl with her underwear around her ankles, joints bent backwards.

The girls screaming.

The burned bodies, wrists tied behind their backs.

Mutilated corpses.

The first responder trying to find live bodies and realizing that everyone, everyone around him was killed.

As I walked out of the screening room there were Israelis in the corridor, just hugging people who were walking out crying. ~ Dov Ben-Shimon, Facebook

*

DOES ISLAM TEACH MUSLIMS TO BE VIOLENT?

(Muslims interpret verses from the Quran relating to committing violence to only be done out of self defense and that Prophet Muhammad pbuh never initiated wars himself.)

~ The thing you need to realize is that Islam has messed up definitions for words and phrases we in the West take for granted and Islam means something totally different in their use of these words. Islam is a war cult intent on taking over the world. Islam wouldn’t be where it is if it was a passive movement of non-aggression.

Islam believes in self-defense as defense of Islam being able to exist and propagate. If you disrespected Islam in anyway, Muslims will turn violent and attack you and think they are perfectly in the legal and moral right to do so as they were defending the honor of their religion.

When these gunmen stormed the offices of Charlie Hebdo and gunned down 12 people for drawing Mohammed cartoons, you saw news videos of them screaming “We have defended the honor of our prophet” while shooting people dead. Every Muslim afterwards thought they didn’t do a single thing wrong.

Try going to the youtube channels for the news reports of these Charlie Hebdo attacks and read the comments left by Muslims. You will see Muslims in the comments universally all saying “they did nothing wrong that day, Charlie Hebdo deserved to die for disrespecting our prophet.” Same applies to the Samuel Paty incident and the Batley Grammar school and every other issue where a follower of Islam turned violent onto someone for them disrespecting Islam.

Same with the Israel / Palestine conflict. Piers Morgan has been having supposedly respectable Muslim scholars on his show to interview them. Not a single one of them think Hamas did anything wrong on October 7th. They all think it was justified resistance of Jewish oppression against Islam.

These scholars think legitimate “self-defense” is Muslims flying on paragliders into Israel and mass raping and killing a bunch of teenagers attending peace concert they setup trying to achieve peace with Palestine. And they won’t have it any other way.

You need to realize what Islam means by "you can only be violent in self-defense." It means self-defense of Islam. It does not mean individual Muslims self-defense. You can be the aggressor and just go and kill people if doing that somehow furthers the goals of Islam.

Islam is an evil violent cult. Anytime in Islam you see something that sounds nice and rosy and pacifist. Keep reading the scriptures and you will see you’ve misunderstood and it means something else completely. ~ Anthony, Quora

Mary:

Islam does not teach Muslims to be violent — violence is a requirement. Notice that the violence, the hideous brutality carried out against Jews, cartoonists, anyone who has "disrespected" them, their prophet, their "holy book," is NEVER criticized by any Muslim ever. It's all just fine with them. More than fine, they cheer and grin and celebrate in monstrous and barbaric joy. Make no mistake, "the barbarians are here" wherever there are Muslims.

In fact, the only example I can think of, at least equal in its barbarism, is the rites and rituals of the Aztecs, whose altars flowed with human blood and who used human skulls as architectural elements. Islam's horrific depersonalization of women, its psychopatholoy of sexuality cannot be ignored or excused away. Islam admires, and demands grotesqueries like "honor killings," rape as a terrorist weapon, and the mass murders terrorists employ to further their agenda. An agenda set out in their basic tenets — death to all infidels, the whole world transformed into an Islamic state.

You cannot negotiate any peace with an enemy who will settle for nothing less than your annihilation, and thinks that would be the holiest of acts, blessed by god.

Absolutely none of the violent passages from the Bible are open-ended commands. The Quran and Hadith contain open-ended commands to kill anyone who leaves Islam and anyone deemed an “Infidel.”

J. Pierre Baspeyre:

For Bible interpretation, there is the distinction between descriptive passages and prescriptive passages. The description of what happened is one thing; prescription is another distinction present for the Koran.

Also, the Bible contains the Old Testament and the New Testament, the old culminating in the teachings of Jesus, whose teachings can be unequivocally summed up in the Sermon on the Mount and the word ‘’love’’: love your neighbor including your enemies.

Steve Bloxham:

You don’t understand. It's gone way beyond logic and common decency. Do you understand what happened on Oct 7? Enough attempts have been made to bring Muslims into the brotherhood of mankind. I lived with Muslims in Michigan. I would give them every benefit of the doubt. I hope they want to be good citizens. Yet too many of them still support killing a cartoonist for making fun of Mohammed. It's perplexing. And sad.

We want to welcome them. Then they happily kill us. And raise their children to kill for these things. It's just unbelievable until we see it done by those who we thought were our friends. It's beyond ridiculous. It is beyond understanding. There is no gray zone. The time has come for the two cultures to go their separate ways. It's sad and hard to see that this is necessary. God knows we tried.

Beth Ann Dvorak:

Maybe it’s just the culture of Arab nationalism that tends towards violence and not the religion.

Anthony:

5:32 effectively instructs Muslims to kill to stop corruption from spreading in the land. Islam classifies doing anything against Islam is corruption in the land. If you doubt that then 5:33 says it more directly to kill anyone who does anything against Islam.

Any book that tells its followers you can kill everyone on earth if you want to is evil.

Kladyn Amundsen:

“Indeed, the penalty for those who wage war against Allah and His Messenger and spread mischief in the land is death, crucifixion, cutting off their hands and feet on opposite sides, or exile from the land. This penalty is a disgrace for them in this world, and they will suffer a tremendous punishment in the Hereafter.”

Douglas Jacobs:

It depends on what is considered evil.

It is against Israel’s law to rape, as well as most countries and cultures, but does that make it “evil”?

Allah, by way of Muhammad, said it is OK to rape women which you possess, therefore it is not evil.

The Hamas freedom fighters possessed the women that they raped, therefore it was not “evil". The rapes would be considered wrong by most standards, but not in Islam.

By some definitions, rape is considered “evil"; by Islam standards, it is not, if you possess the woman. It all depends on the definition of “evil.”

Tim Hardy:

Islam is full of rapists. That is a fact, not just what I think. It really is a violent, evil cult, supported by people who have been indoctrinated.

Anonymous;

I'm getting tired of those who are in denial. Not every Muslim is violent..... but let's stop pretending that Islam doesn't have a problem.

This child of a Muslim terrorist is holding up a decapitated head.

[Oriana: I decided to omit the photo, even though it was partly blacked out already. The obscene thing is that the child is clearly happy and proud.]

When are progressives going to start criticizing Islam? They loathe and revile Christianity and Judaism, and yet inexplicably think that any criticism of Islam is racist and intolerant. Laughable for a number of reasons including the fact that Islam is not a freaking race. It's a religion.

Kevin Dwyer:

Islam has not gone through a Reformation like Christianity, and it has no single voice like the Pope speaking for all Catholics.

So... peaceful-minded people pick and choose which parts they follow, and extremist-minded people find what they are looking for as well.

Some religions are more attractive to extremists than others, but a better predictor of violence seems be societal rather than religious. A peaceful prosperous society tends to breed peaceful prosperous people. A rigidly intolerant society is fertile ground for extremism.

Gawaine Ross:

“Carnage is better than idolatry,” said the angel Gabriel. ("Slay them wherever you find them...Idolatry is worse than carnage...Fight against them until idolatry is no more and God's religion reigns supreme." (Surah 2:190-)

Nor is that quote taken out of context. The Quran breathes fire against unbelievers and is the most violent scripture ever written.

Blasphemy, sacrilege and apostasy are capital offenses in Islam. Apostasy means abandoning Islam after conversion. If you convert, you will be in a prison from which there is no escape. Islam is all about becoming a slave of Allah, which is regarded as a holy act, because then you can’t sin any more.

George Graham:

In 12 Muslim countries atheism is punishable by death. Apostates don't seem to fare much better. Other religions are treated as inferior and their adherents discriminated against. They seem to be incapable of offering their citizens equality in diversity or justice equality under the law.

Joshua Kaplan:

What we all do know is that while the majority of Muslims are peace-loving people, there is a minority that does seek to cause violence and mayhem to non-Muslims. They may be a small minority but they are obviously large enough to significantly effect the security of the rest of the world.

Often this violence is obvious and unabashedly self-declared by the perpetrators as Jihad against infidels. In other cases it is masked or excused as politically or self defense motivated. There are conflicts and attacks that are genuinely motivated by secular reasons but the overlap of rhetoric, tactics and groups involved between secular and religious conflicts is significant that it is often difficult to determine objective motivations.

Being that most of the violence is perpetrated by a relatively small minority, it should not be that difficult for the majority to address the issue and if not put an end to the violence, at least make it clear that it is not something that the vast majority has any agreement with or part in. This begs the question: Why has this not happened?

In my humble opinion, the very first step must be the admission by the general Muslim population that the problem exists.

It is much easier to believe in a conspiracy by unknown forces (be it the C.I.A., the Zionists, rich Jewish bankers, Hollywood etc), then to believe that your deeply held religious convictions — of which you are certain have nothing to do with promoting violence — are somehow the motivation behind such evil acts.

But it is this, conscious or unconscious, willful blindness that must be dealt with before any hope of Islamic violence disappears.

Frank Dauerhauer:

This is a naive question. You could just as well ask “Why are humans violent?” You should qualify it in some way, such as, “Why are some Muslims violent, and other Muslims peaceful?”

Joe Milosch:

After three months of death and destruction, there is no moral or strategic reason for Israel to continue the destruction of the Gaza Strip, and Netanyahu’s strategy of unshackled violence is responsible for Bethlehem’s cancellation of its Christmas celebrations. Maybe the citizens of Christ’s birthplace realized that the term God’s Love is a euphemism for His vengeance. On television, pictures of the rubble of Mosques, churches, hospitals, schools, and houses showed that Netanyahu plans to bomb the Palestinians out of existence. Automatically, the Israeli government labels the above as antisemitic, but today, almost the entire world views the continued bombing of Gaza as overkill.

Hamas’ attack was horrendous, but Netanyahu’s refusal to fight within the expected norms of battle is turning the world against his war. Despite this, people continue to look at the Muslim religion as though violence is a doctrine that is either explicitly or implicitly taught in religious schools and mosques.

Islam does not teach violence more than any other religion. A study showed that the Mayan civilization started in one village that was very successful in agriculture. After the harvest, other tribes would raid and steal their food. To protect themselves, they formed an army, and to ensure their success, the religious leaders found a god of war to pray to, and he demanded continual human sacrifice. This practice led to a never-ending state of war and an empire. The Mayan empire began the same way as the ancient empires of the Middle East.

Today, some religious scholars believe that the deity of war became the God that the Judeo-Christian-Muslim religions believe in. At first, worship required human sacrifices, but animals were less expensive, and eventually, the high priests discovered that prayer was the most economical way of appeasing the gods.

Today, every country has a dominant religion, and to keep the religious leaders powerful and wealthy, religion supports hatred of the other. The leaders use the idea of God’s love to con people into joining them, and as a person regularly attends religious services, they become indoctrinated into the army of Christ, The Ark, or The Jihad. The war in the Gaza Strip is proof of the successful implementation of the old axiom priests: God-sanctified hatred is more satisfying than His love. Thus, every war is a religious war, and it is invalid to claim that Islam is a more violent religion than Christianity or Judaism.

Oriana:

I think that Christianity went through its period of violence, aka "Trail of Blood."I'm thinking of the Crusades and the Inquisition. But that was long ago. Islam has never had a Reformation, and seems still stuck in its violent stage. I realize that, as practically always, most Muslim are not violent, but it's the violent ones who get all the publicity. They can quote the Koran on how to treat Jews: "Kill them wherever you find them."

Joe:

Yes, you are right. It is the violent minority, but the majority seldom steps in until it is too late.

Mosque in Moscow

*

“NEVER AGAIN IS NOW”

“Never again is now" was projected onto the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin for the 85th anniversary of Kristallnacht — photo on November 9, 2023

*

THE RISE (AGAIN) OF GLOBAL ANTISEMITISM

~ Many of us don't understand what is going on, why global antisemitism rears its ugly head with such force. Actually, it's very simple. The Jew is not supposed to fight back. The Jew is supposed to go to his death like a lamb to the slaughter. And he did so, many-many times throughout history. (Please note that when I say " the Jew," I am speaking about the collective rather than an individual Jewish person.) If he does, the world will commiserate with him, light up its Eiffel Towers in the colors of his flag, build museums in his memory with objects plundered from burned synagogues and nostalgic photos of what Jewish life was like in "Jewish places," etcetera.

But if he fights back, he becomes, in the subconscious of all nations, the representative of Evil, the concentration of everything they repress in themselves. When the Jew is strong, he is hated. When the Jew is weak (or dead), he is loved (or laughed at, the way one laughs at something that seemed dangerous but proved to be no more than a popped bubble). We've seen it plenty of times. In a nutshell, the Jew is not allowed to be strong, and antisemitism rears its head as soon as he, the Jew, insists on his right to live and to be strong (to crush his very real enemies ) no matter what.

This changes only when the Jew himself "changes". He is allowed to be strong only if he renounces being a Jew, i.e. if he converts or simply stops identifying as a Jew, although there are exceptions to this rule: the Inquisition tortured converted Jews ("marranos") until they "confessed" to being Jews.

And in the Soviet Union, as we know, even renouncing one's Jewishness wasn't enough; even when religion was no longer part of "being a Jew," there was that infamous line #5 in Soviet passports, and if you managed to hide under a Russian "nationality," you could still be outed, there was the evidence of your last name and if, say, you managed to hide your Jewishness under a non-Jewish sounding name, there were other signs that gave you away — your "long nose", your "dark hair", etc.

As for Nazi Germany, it killed even quarter-Jews, i.e., even those who had one Jewish grandparent and who did not identify as Jews at all. I could go on and on listing exceptions to the rule of "we'll accept you if you stop being a Jew," but Facebook requires brevity. This mystery, the origins of antisemitism, puzzled me for years. I read a lot about it, and even wrote a 300-page novel ("Queen of the Jews"), examining the roots of antisemitism from antiquity to our time, in some detail. ~ Nina Kossman, Facebook

Jerusalem, Wailing Wall

*

PUTIN’S CLAIM TO “HISTORICAL JUSTICE” (Dima Vorobiev)

President Putin started the Ukraine war out of the logic of historical justice.

Our story

In his 2021 treatise “On historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” our beloved ruler says that our nations are basically twins separated almost at birth because of enemies. The attempts of nationalists in Kiev to assert a Ukrainian identity that is separate from and even hostile to Russia must therefore be nothing more than an evil Russophobic plot.

One of the last big news in Russia was our head of the Supreme Court bringing to the Kremlin a French map from the 17th century. He dug it up in the archives where no one found it before. The loyalist media widely broadcast the scene of the justice and Putin in the Kremlin sharing the joy of finding no Ukraine in it.

If the Europeans knew nothing about this “Ukraine” thing in the era of Imperial France, they’ve got no reason to insist that Ukraine has an agency separate from Russia.

Dissident view

Detractors of Putin often deride his theory with references to the Golden Horde.

We were part of the Mongol Empire for more than two centuries. No legally binding document confirms that we indeed became independent from them in the late 15th century.

Peter the Great’s treaty with the Ottomans that formally ended Russia’s tributary dependence to the Chingizides was signed without the participation of Mongol representatives. In other words, following our President’s legalistic approach, the Mongols have the formal grounds to consider themselves our masters until today.

The Jewish take

However, a truly hardcore approach to the issue brings up an even more bizarre view of Russia’s identity. Consider the following:

The first written source found on the territory of what we used to call Kievan Rus is in Hebrew.

Our first rulers called themselves Kagans. This is what Jews called their high priests.

Several letters of our alphabet have Jewish origins. The Greek Orthodox clergy that invented the Cyrillic alphabet reworked Hebrew letters for Slavic hissing sounds that the Greeks didn’t have. (Did you know our Lord Jesus Christ was a Jew, too?)

The Russian criminal slang, favored by our political class for sending strong messages to each other and to Russia-haters internationally, comes from the Jewish underworld in the city of Odessa in the 19th century.

*

Below, Marx and Lenin impersonators earning money in the Red Square in Moscow by posing for tourist photos in the company of foreign visitors.

Marx was officially a Jew, and Lenin’s mother was allegedly Jewish, too. This makes applied Marxism-Leninism, the official ideology of the USSR, a 75% Jewish thing. It made our country a world superpower, and Soviet rule the pinnacle of our millennial history- Another possible reason for Israel to claim a historical unity of Jews and Russians.

In the no-nonsense world of historical justice, there’s only one thing that truly stops the Mongolians and Israelis from claiming the Kremlin once President Putin vacates the place. It’s the fact that we are big and have thousands of nukes, and they do not. ~ Quora

Oriana:

Much as I enjoy the “Jewish take” on Russia’s history, “Kagan” is a word of Turkic origin, meaning "ruler", "King of Kings" (alternatively spelled as Kağan, Khagan or Hakan, meaning "Khan of Khans”).

So Turkic, rather than Yiddish.

But I’m glad I found out, since various forms of Kagan or Kaganovich are a fairly common last name, and now I have some idea of the meaning of that word, related to “Khan” (as in Genghis Khan).

I’m also fascinated to have learned that Fenya, the Russian criminal slang, is derived from Yiddish. Now I finally understand why it’s not comprehensible to the average Russian.

*

MISHA IOSSEL COMMENTS ON UKRAINE

Valerii Zaluzhnyi, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, has named his main mistake to NEXTA information agency:

"My main mistake is that I thought that such a number of losses as we inflicted would stop anyone. But it did not stop Russia.”

That's because Putin has zero regard for the value of the human life. Because in the imperial Russian/Soviet culture, the worth of human life is close to zero. That also, in more practical terms, is because Putin's regime isn't recruiting soldiers from political power centers, such as Moscow and SPB, but is conscripting young men from small towns and villages in the far-flung regions of Siberia and the Far East, for instance, as the bulk of his army's cannon fodder.

And it is precisely this total disregard for the value of the human life which in and of itself is the sufficiently essential reason why the West, if it wants to survive, must help Ukraine to defeat Russia in this unconscionable war.

Oriana:

Putin’s motto could be summarized as “No lives matter.”

Except his own. He is allegedly paranoid that his enemies will manage to kill him. He's afraid he'll be poisoned, or pushed out the window. "What goes around comes around."

*

NINA KOSSMAN ON THE ROLE OF THE SOVIET UNION AS A NEGATIVE MODEL

I think that, while the Soviet Union existed, it gave the American left a vicarious experience of the realization of far-left ideas, i.e. a look at what that realization could be like. The very existence of the USSR was a warning to the world: see? don't be like me!

It wasn't done intentionally of course, but that was the effect both on the American left and the American right: neither left nor right in those days went to the extremes that we are seeing now. Now we have two generations — Millennials and Gen Z — that grew up in the post-Soviet era, so there's nothing that can serve as a warning to them in the “See? Don't be like me!” way.

By the way, the American right was also more moderate back then ( during the Cold War), because the fear of a revolution and its consequences were a bit more real when the Soviet Union still existed.

The Soviet Union was like a scarecrow that said: "Don't go the way of the radical left or you'll end up like me!" The surge in antisemitism we are seeing now is like that proverbial canary in the coal mine showing us where we are heading — and saying "Stop!"

I am talking about the subconscious of the political left and the political right, not about something that's evident and visible on the surface. The Soviet Union was a boogeyman of the political subconscious of both left and right ( in different ways of course) in those years.NB: Please note that I'm talking about "radical left" — not just “left". ~ Nina Kossman, Facebook

*

Geoff Manger:

While the USSR existed and 'competed' with the USA in areas of, for example, the space race, it drove American technology and industrialization to extents that may not have been achieved had there been no USSR. It was of course inevitable to give context that a USSR eventuated as soon as Hitler invaded Russia. As a reaction to Russian communism and particularly the USSR the McCarthy era brought its own attack on left wing political activists in the USA. So, I think it bit of an urban myth that the political divide is now at its zenith. If anything, political apathy is the bigger danger to democratic society.

Mark Shvarts:

But we have North Korea and a host of other so called “communist” countries today. They don’t serve as examples?

Nina Kossman:

I think they don't serve as examples because in America they are not perceived as “far left.” Yes, North Korea and Cuba are “Comnunist” countries, but here in the US, North Korea is perceived mostly as a totalitarian country, while Cuba is perceived as a kind of failed state, a poor Latin American country. And although China calls itself "Communist," it's actually quite capitalist, and its "Communism" is just a convenient ideology that simply makes it easier for the party to rule ( and fool) the people.

So the Soviet Union was the main scarecrow.

Andrei Shipunov:

Ever since I plunged into the English-language information space, I have watched with anxiety and sometimes horror how the bloody Soviet experience is systematically ignored. However, both neutral and positive aspects are also ignored. And here are the results it leads to (only the brightest examples):

The left wrote to me more than once in the comments that Holodomor is a Nazi propaganda;

The right-wing believed the Kremlin propaganda and declared with amazing confidence that Ukraine is actually not a real state, and as an argument they cited the unfinished demarcation of the borders between us and the Russian Federation.

Against the backdrop of such indecency, it is not so impressive, of course, but also interesting: many do not believe that my dad and mom, being engineers, received the same salary. And here I have to explain that, surprisingly, in the absence of a blatant Pay Gap, women's lives did not become much sweeter, as all the housework fell on them.

One of my acquaintances had a grandmother who was a chemist, so his American friends didn't want to believe it. "It's the USSR, there couldn't have been anything we consider good" — is that the way it works?

It would all be funny and amusing if the KGB hadn't used such illiteracy for its own purposes.

Osoba Kaz:

You are absolutely right! The Kremlin propaganda is so strong that it beats not only the overseas flock, but also the post-scoop. My blue-eyed nephew was explaining to me how good it was there. Okay, he was born after the Soviet Union, but you can ask his parents what it was like there.

*

HEMP COFFEE

One of Nina Kossman’s memories of Kyiv: hemp coffee. Hemp coffee? In Poland there used to be “grain coffee” — real coffee was expensive. One advantage of grain coffee was that it was OK for children to drink — and the taste, though I remember it vaguely at best, was tolerable, especially with milk.

*

Misha on the normalization of Russia’s violence against Ukrainian civilians:

~ Last night (December 28) Russian missiles struck a maternity hospital and scores of residential buildings all across Ukraine. The goal is to kill as many civilians as possible, with no military objective in mind. The world has come to expect such barbarous conduct from Russia. It no longer is shocking to the world — and that's the shocking part of it. The world continues to tolerate these atrocities. ~

Oriana:

No one in the West wants to start a war with Russia, which would mean WW3. But the world was also willing to tolerate Hitler’s various preliminary land grabs and depredations — to approve of “appeasement” (“Peace in our time!”)— until it was too late.

*

LEARNING FROM THE GULAG

15. I realized that one can live on anger.

16. I realized that one can live on indifference.

17. I understood why people do not live on hope—there isn’t any hope. Nor can they survive by means of free will—what free will is there? They live by instinct, a feeling of self-preservation, on the same basis as a tree, a stone, an animal.

~ From "Forty-Five Things I Learned in the Gulag," in "Kolyma Stories," by Varlam Shalamov. Translated by Donald Rayfield.

Varlam Shalamov

*

“WILL POWER” MAKES A COMEBACK

~ Until recently, the prevailing psychological theory proposed that willpower resembled a kind of battery. You might start the day with full strength, but each time you have to control your thoughts, feelings or behavior, you zap that battery’s energy. Without the chance to rest and recharge, those resources run dangerously low, making it far harder to maintain your patience and concentration, and to resist temptation.

Laboratory tests appeared to provide evidence for this process; if participants were asked to resist eating cookies left temptingly on a table, for example, they subsequently showed less persistence when solving a mathematical problem, because their reserves of willpower had been exhausted. Drawing on the Freudian term for the part of the mind that is responsible for reining in our impulses, this process was known as “ego depletion”. People who had high self-control might have bigger reserves of willpower initially, but even they would be worn down when placed under pressure.

In 2010, however, the psychologist Veronika Job published a study that questioned the foundations of this theory, with some intriguing evidence that ego depletion depended on people’s underlying beliefs.

Job, who is a professor of motivation psychology at the University of Vienna, first designed a questionnaire, which asked participants to rate a series of statements on a scale of 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). They included:

When situations accumulate that challenge you with temptations, it gets more and more difficult to resist temptations.

Strenuous mental activity exhausts your resources, which you need to refuel afterwards

and

If you have just resisted a strong temptation, you feel strengthened and you can withstand new temptations.

Your mental stamina fuels itself. Even after strenuous mental exertion, you can continue doing more of it.

If you agree more with the first two statements, you are considered to have a “limited” view of willpower, and if you agree more with the second two statements, you are considered to have a “non-limited” view of willpower.

Job next gave the participants some standard laboratory tests examining mental focus, which is considered to depend on our reserves of willpower. Job found that people with the limited mindset tended to perform exactly as ego depletion theory would predict. After performing one task that required intense concentration – such as applying fiddly corrections to a boring text – they found it much harder to pay attention to a subsequent activity than if they had been resting beforehand.

The people with the non-limited view, however, did not show any signs of ego depletion, however: they showed no decline in their mental focus after performing a mentally taxing activity.

The participants’ mindsets about willpower, it seemed, were self-fulfilling prophecies. If they believed that their willpower was easily depleted, then their ability to resist temptation and distraction quickly dissolved; but if they believed that “mental stamina fuels itself”, then that is what occurred.

Job soon replicated these results in other contexts. Working with Krishna Savani at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, for example, she has shown willpower beliefs seem to vary by country. They found that the non-limited mindsets were more common in Indian students than those in the USA – and that this was reflected in tests of their mental stamina.

In recent years, some scientists have debated the reliability of the laboratory tests of ego depletion, but Job has also shown that people’s willpower mindsets are linked to many real-life outcomes. She asked university students to complete twice-daily questionnaires about their activities over two non-consecutive weekly periods.

As you might expect, some days had much higher demands than others, leading to feelings of exhaustion. Most of the participants recovered to some degree overnight, but those with the non-limited mindsets actually experienced an increase in their productivity the following day, as if they had been energized by the extra pressure. Once again, it seemed that their belief that “mental stamina fuels itself” had become their reality.

Further studies showed that the willpower mindsets could predict students’ procrastination levels in the run-up to exams – those with the non-limited views showed less time-wasting – and their ultimate grades. When facing high-pressure from their courses, the students with the non-limited views were also better able to maintain their self-control in other areas of life; they were less likely to eat fast food or go on an impulsive spending spree, for example. Those who believed that their willpower was easily depleted by their work, in contrast, were more likely to indulge in those vices – presumably because they felt that their reserves of self-control had already been depleted by their academic work.

The influence of willpower mindsets may also stretch to many domains, such as fitness. For example, Navin Kaushal, an assistant professor in health sciences at Indiana University, US, and colleagues, have shown that they can influence people’s exercise habits; people with non-limited beliefs about willpower find it easier to summon up the motivation to work out.

A study by Zoë Francis, a professor of psychology at the University of Fraser Valley, found strikingly similar results. Following more than 300 participants over three weeks, she found that people with non-limited mindsets are more likely to exercise, and less likely to snack, than those with the limited mindsets. Tellingly, the differences are especially pronounced in the evenings, when the demands of the day’s tasks have started to take their toll on those who believe that self-control can easily run down.

Galvanizing your willpower

If you already have the non-limited mindset about willpower, these findings might be a cause for self-satisfaction. But what can we do if we have been living under the assumption that our reserves of self-control are easily depleted?

Job’s studies suggest that simply learning about this cutting-edge science – through short, accessible texts – can help shift people’s beliefs, at least in the short term. Knowledge, it seems, is power; if so, simply reading this article might have already started to galvanize your mental stamina. You might even enhance this by telling others about what you have learnt; the research suggests that sharing information helps to consolidate your own shift in mindset, a phenomenon known as the “saying-is-believing effect”, while also helping to spread the positive attitudes to others.

Lessons in the non-limited nature of willpower can come at a young age. Researchers at Stanford University and the University of Pennsylvania recently designed a storybook to teach pre-schoolers the idea that exercising willpower can be energizing, rather than exhausting, and that self-control can grow the more we practice it. Children who had heard this story showed greater self-control in a test of “delayed gratification”, in which they were given the chance to forgo a small treat to receive a bigger treat later on, compared to their classmates who had heard another tale.

One useful strategy to change your mindset may be to remember a time when you worked on a mentally demanding task for the pure enjoyment of the activity. There might be a job at work, for example, that others appear to find difficult but you find satisfying. Or maybe it’s a hobby – such as learning a new piece on the piano – that demands intense concentration, yet feels effortless for you. A recent study found that engaging in this kind of recollection naturally shifts people’s beliefs to the non-limited mindset, as they see proof of their own mental stamina.

To provide yourself with further evidence, you might begin with small tests of self-control that will bring about a desired change in your life – such as avoiding snacking for a couple of weeks, disconnecting from social media as you work, or showing greater patience with an irritating loved one. Once you have proved to yourself that your willpower can grow, you may find it easier to then resist other kinds of temptation or distraction.

You mustn’t expect miracles immediately. But with perseverance, you should see your mindset changing, and with it a greater capacity to master your thoughts, feelings and behavior so that your actions propel you towards your goals.

https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20230103-how-to-strengthen-willpower

*

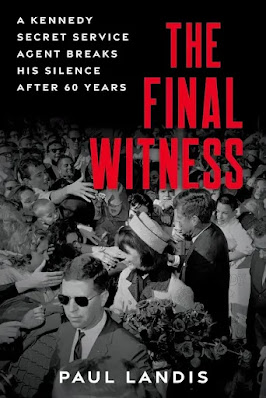

A NEW CLUE IN JFK ASSASSINATION MYSTERIES?

~ Twenty-three-year-old Paul Landis applied to become a Secret Service agent in 1958. He came from Worthington, Ohio, a suburb of Columbus, and had graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University 15 months earlier. A neighborhood boy, Bob Foster, who was friends with Landis’s sister, had joined the Secret Service two years before. After speaking with Foster, Landis thought being in the Secret Service sounded like the “coolest job in the universe.”

Landis was intrigued. But because he has always been slight of build, his immediate concern was whether he could meet the minimum height requirement (five feet, eight inches). During the physical exam, he stretched himself like a rubber band and, as he recalls, barely made it.

He started work in October 1959, at the time the youngest special agent, at 24. Just over a year later, John Kennedy was elected president; soon the young recruit was assigned the job of guarding the Kennedy children and, eventually, along with Special Agent Clint Hill, Mrs. Kennedy herself. Not all agents were given code names, but as a result of Landis’s new assignment, and because of his youth and boyish looks, he was eventually christened “Debut.”

Landis found himself deep in the inner workings of Camelot, coinciding with the apex of Jackie’s popularity. As an international superstar, she was the Princess Di of her era, and Landis was on hand as the media followed her every move. Landis traveled with the first lady and her daughter, Caroline, to Italy in 1962. (John Jr., her young son, remained back home.) Landis was the agent who helped speed and accompany Jackie to the Otis Air Force Base emergency facilities when she went into premature labor with son Patrick, who died two days after his birth in August 1963. That October, at the suggestion of Jackie’s sister, Lee Radziwill, a trip to Greece followed for an excursion aboard the luxury yacht of the shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis.

Then came November 22, 1963. A month after returning from Greece, Landis stood on the right rear running board of the Secret Service follow-up car, code-named “Halfback,” in the president’s motorcade as the vehicle headed from Dallas’s Love Field airport to a luncheon at the city’s Trade Mart. Landis was approximately 15 feet away when Kennedy was mortally wounded, a close witness to unspeakable horror.

That horror was compounded when the president’s limo reached Parkland Memorial Hospital, where Landis and Clint Hill tried to coax Jackie to release the president, whom, by that point, she had cradled in her lap. Climbing into the back seat area, which had been spattered with blood and brains and bullet fragments, both agents, according to their subsequent accounts, gently encouraged the first lady to let go.

As she did—standing up to follow Hill and another agent, Roy Kellerman, who lifted her husband’s body onto a gurney and raced into the hospital—Landis saw and did something that he has kept secret for six decades, he says now. He claims he spotted a bullet resting on the top of the back of the seat. He says he picked it up, put it in his pocket, and brought it into the hospital. Then, upon entering Trauma Room No. 1 (at that stage, he was the only nonmedical person in the room besides Mrs. Kennedy, and both stayed for only a short period), he insists, he placed the bullet on a white cotton blanket on the president’s stretcher.

Landis, to this day, attests that in the first few years following the assassination, he was simply unable to overcome his PTSD from witnessing the murder firsthand. He says that the mental image of the president’s head, exploding, had become a recurring flashback. He maintains that he desperately tried to push down the memories. He also says he felt unable to read anything in detail about the assassination until some 50 years later, starting in 2014, when he began to come to grips with all that he had witnessed, suppressed, and finally processed.

Over the decades, there have been endless theories surrounding the assassination, but not one of them considered that a Secret Service agent might have brought a fully intact bullet, found on top of the rear seat of the limousine, into Parkland Memorial Hospital and placed it on the president’s stretcher. Not one.

That theory posits that a single bullet caused all of the wounds in Kennedy’s neck as well as all of the serious injuries to Texas governor John Connally—who was sitting in front of the president at the time—including the shattering of four inches of Connolly’s fifth rib and the fracturing of a major bone in his right wrist.

Yet the bullet that Landis now claims to have discovered that morning emerged largely intact and only moderately damaged, its base having been squeezed in.

By possibly placing the “magic bullet” theory in doubt, Landis’s disclosure raises as many questions as it answers. I will try to address some of them here.

First, it makes sense to retrace the main tenets of the Warren Commission’s official version of the assassination. According to the panel’s final report, issued in September 1964, three gunshots rang out as the president’s limousine passed by the Texas School Book Depository building in Dallas. Witnesses’ auditory memory differed, their testimony ranging from two to six shots. Most, however, recalled hearing a trio of blasts.

Three spent shells, in fact, were found under a window on the sixth floor of the book depository. Nearby, partially hidden by some cartons, a rifle with a scope was discovered, a cheap Mannlicher-Carcano. Lee Harvey Oswald, the man history identifies as the lone assassin, worked in that building. The commission determined that the three shots all came from the sixth floor of the book depository.

The commission concluded that two of the three shots had hit the occupants of the limousine: One bullet had transited Kennedy’s neck and then, most probably, hit Governor Connally, and one had fatally wounded Kennedy, striking his head. (Connally survived the attack, later becoming President Richard Nixon’s Treasury secretary.)

In the view of the task force, one of the shots had likely missed the limo and, though the conjecture was inconclusive, possibly struck a nearby cement curb, sending a fragment that hit a spectator some distance away, near an overpass, slightly grazing his face.

But what of the ammunition itself? Two large bullet fragments were found in the front seat of the limo, and slivers of lead fragments were recovered from an area below the jump seat where the governor’s wife, Nellie Connally, had been sitting.

At Parkland Memorial Hospital, on the day of the assassination, an additional intact bullet was discovered on a stretcher. Through testing, commission investigators determined that the copper-jacketed, 6.5-millimeter bullet matched the rifling of the Mannlicher-Carcano that had been abandoned on the sixth floor of the depository. Testing on the bullet fragments resulted in a similar finding.

In his book, Paul Landis now says that when Jackie Kennedy stood up to enter Parkland, he looked over and saw that a bullet was improbably sitting on top of the rear seat of the limo, right around the spot where the limo’s detachable roof, which had been removed that day, would have otherwise been affixed to the trunk. Also, amid the blood and gore, Landis remembers, were two bullet fragments on the back seat, next to where Jackie had been sitting.

Landis contends that he reached over, picked up the lone bullet nestled in the crevice, and decided to place it in his pocket, mindful that if it were left there, precariously, it might be overlooked, pilfered by an unauthorized passerby, or misplaced once the president’s body was removed. Accompanying the first lady into Parkland, he says, he brought the bullet with him and, without conferring with Mrs. Kennedy, his fellow agents, or hospital staffers, placed it on JFK’s stretcher, thinking it needed to be with the body for the autopsy. As such, he contradicts a key linchpin underlying the findings of the Warren Commission. The bullet—as Landis tells it—was not from Connally’s stretcher.

A short recap is in order. Initially, President Kennedy was declared dead at Parkland—his body lying face-up on the table after the surgical team had performed a tracheotomy, hoping to provide needed oxygen through a ventilator to keep him breathing (which by that time was described as gasping or agonal respiration). These emergency room doctors used what they believed was an entry bullet wound in the front of the president’s neck to create the tracheotomy. They were apparently unaware of a bullet hole in the president’s back.

But later that night, an autopsy began at Bethesda Naval Hospital, near Washington, DC. During the procedure, doctors examined the president’s remains, only to discover a small bullet hole in the right shoulder, about five inches down from the top of the collar. This injury had gone unnoticed at Parkland since the president was declared dead before his body could be surveyed in its entirety. The Bethesda pathologists were puzzled when they probed the wound because it clearly was an entrance puncture, but it did not seem to have an exit wound, even though X-rays showed no bullet in the body.

In fact, the shoulder wound was shallow. Two doctors found that they could not pass more than half a pinky finger into the opening. Metal probes likewise uncovered no path of the bullet through the body.

Standing in proximity to the doctors were two FBI agents, Frank O’Neill and Jim Sibert, who had been dispatched by the bureau’s director, J. Edgar Hoover, to witness the autopsy and recover bullets or bullet fragments for the FBI lab. In their written statement, the agents discussed the frustration of the Bethesda doctors when they could not locate a bullet or exit wound for the projectile that had entered the president’s shoulder.

The next morning, the Bethesda pathologists, as stated in their Warren Commission testimony, were told by Parkland doctors that the wound in the front of Kennedy’s neck was more than just the result of the tracheotomy they had performed. In fact, the Parkland team stated, there had been a bullet hole in the anterior (front) of the neck, and the ER staff had used that wound to create the tracheotomy. No one at the autopsy, according to FBI agents Sibert and O’Neill, had suspected there was a hole in the front of the president’s neck. With this new information, the Bethesda doctors revised their findings and assumed that the front wound was an exit for the bullet that had entered the president’s body from the back.

Landis’s discovery of the bullet on top of the rear seat, if true, comports with the initial finding: that the bullet had lodged superficially in the president’s back before being dislodged by the final blast to his head. It also explains the “pristine” nature of the bullet.

*

The genesis of the “single bullet” theory was twofold.

First, the Zapruder footage showed Kennedy reacting to the bullet that hit him in the back—and then, apparently, exited through the front of his neck (his arms spasmodically began to rise, elbows out, fists shielding his throat)—about a second or so before Connally seemed to react to his own wounding. To the Warren Commission staff, that double reaction on the part of the two men was puzzling. Given the type of weapon Oswald was using, there would have been no way for him to have gotten off two firings in such a short span of time.

Secondly, when the panel attempted to recreate the shooting in a manner consistent with the Zapruder film, FBI marksmen found that it took about 2.3 seconds to shoot, reload the bolt-action rifle, aim, and shoot again. Given Governor Connally’s reaction time, there did not appear to have been enough time for Oswald to have taken a second shot so quickly, let alone with any accuracy.

Howard Willens, an assistant counsel to the Warren Commission, and the author of the 2013 book History Will Prove Us Right, wrote about this dilemma: “If the interval between the first and second shots covered a span of less than 2.25 seconds, the time estimated to be necessary for the assassin to fire two shots, it might suggest that a second rifle was involved.”

The commission’s solution, however, championed by staff attorney Arlen Specter (who would become a US senator from Pennsylvania), was that the same bullet that hit Kennedy must have gone on to hit Connally on his right side. Connally’s second-later response was explained by the commission as a “delayed reaction” to an earlier wounding.

But, as noted, that theory depended on the single bullet having been found on Connally’s stretcher at Parkland Memorial Hospital, not on Kennedy’s stretcher.

Landis’s recollection, as stated above, is that he found the undeformed bullet on top of the back seat of the limousine. “It was resting in a seam where the tufted leather padding ended against the car’s metal body,” he writes. When Jackie Kennedy stood up to follow her husband into the hospital, he saw it. He picked up the bullet, worried that souvenir seekers or others might take it or move it.

Upon arriving inside the emergency room, as stated above, he was jammed in with the first lady and a gathering horde of doctors and nurses. Standing near the feet of the president’s body, Landis left the bullet on his stretcher, as he believed it was crucial evidence and needed for the autopsy, which, under Texas law, should have taken place in Dallas.

That evening, the initial supposition was that the bullet had come from JFK’s stretcher because the autopsy doctors at Bethesda, attempting to understand the whereabouts of the bullet that had entered Kennedy’s back, thought it might have been lodged in his back and then fallen out when rigorous chest massages were performed at Parkland.

It was only after the autopsy (and after the president’s body had been moved to the White House) that Parkland doctors told the pathologists that they had used a bullet wound in the front of Kennedy’s neck to make a tracheotomy.

Upon hearing this, the autopsy doctors tentatively revised their thesis and surmised that the bullet that entered Kennedy’s back must have exited through the front of his neck.

*

What does all this mean when considering whether Lee Harvey Oswald, as proposed by the Warren Commission, was the lone assassin? It certainly raises the stakes that another shooter might have been involved.

First, if the “pristine” bullet did not travel through both Kennedy and Connally, somehow ending up on Connally’s stretcher, then it stands to reason that Connally might have actually been hit by a separate bullet, coming from above and to the rear. The FBI recreation suggests that Oswald would not have had enough time to get off two separate shots so quickly as to hit Connally after wounding the president in the back. A second shooter must be considered.

But there are other, darker explanations arising from the secrecy surrounding the X-rays and photographs taken at the autopsy and then not made public for decades. Jerrol F. Custer, the principal X-ray technician at the autopsy, testified in 1997 that there were several small metallic fragments in the cervical spine (the spinal region directly below the skull), which were visible in an X-ray, and that this was one of three X-ray exposures he took that night that went missing from the collection in the National Archives.

This might have contained evidence of a shot from the front of the motorcade—a frangible bullet that disintegrated into tiny pieces after entry into the body. A heavy lift, for sure, but medical staffers who saw the front-of-the-neck wound before the tracheotomy believed it was an entrance wound because of its neatness.

In 2013, a week before the 50th anniversary of the assassination, public opinion polls found that more than 60% of Americans believed the president’s murder had not been the work of one man, as the commission contended, but part of some kind of conspiracy.

*

Upon leaving the bullet on Kennedy’s stretcher, Landis explains today, he felt that he had done the right thing, expecting an autopsy and mindful of the need for the bullet to remain with the body. Like all of the Secret Service members on hand that day—and, indeed, the entire nation—he was also racked with grief and loss (to say nothing of PTSD, which was an unrecognized condition at the time). For Landis, however, a man who had been a constant presence in his life had been slain right in front of him—a man whose wife’s safety had been, in part, his own responsibility.

In May, nearly six months after the assassination, Landis realized that the ordeal had taken its toll; concerned about his own mental health, he decided he couldn’t take it anymore. By August, at age 29, he had left the Secret Service. At the time, the Warren Commission had not issued its report, nor had Landis been interviewed for it; the public had not yet heard of the “single bullet” theory.

In the intervening seven years, Landis struggled with his conscience. His guilt, in my estimation, stemmed in part from a creeping concern that others might accuse him of having done something wrong by moving the bullet. Moreover, he must have worried, to some degree, about not having spoken out about finding the bullet in the first place—and not having sought to clarify the record more speedily once it became apparent to him that many historians and the public at large had cast doubt on the findings of the Warren Commission.

Another factor amplifying his angst, I would imagine, was that the longer he remained silent, the harder it became to speak out.

The only agent who really had a chance to avert disaster was the driver Bill Greer, who might have taken evasive action with the president’s limo once the shooting started. The agent next to Greer in the front passenger seat of the presidential limo, Roy Kellerman, likewise didn’t react in time.

Landis had an underlying guilt about what he might have done. He had found a bullet—the first piece of evidence logged into the record of the assassination of a US president—and then he went on his way, alone, in private.

He was in his late 20s at the time, a man whose values were grounded in those of the 1950s and ’60s. Silence and discretion, to him, had always been virtues. And he didn’t feel that it was appropriate to change his stripes and “go public”—drawing attention to his own behavior—when conspiracy theorists ran rampant, when other agents had been in the press over the years, and when President Kennedy had been killed, in effect, on his watch.

All of this, I contend, contributed to his years of silence.

But nothing, as I see it—and as Landis himself sees it—should detract from the fact that he has now come forward with his version of what happened on that dreadful day. And history will be the better for it.

https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2023/09/new-jfk-assassination-revelation-upend-lone-gunman

Oriana:

I admit I severely abridged this article — but I don’t think that I left out anything of critical importance. To me the single piece of evidence that remains fascinating is not so much the bullet on the stretcher as the fact that the neck wound looked more like an entrance wound — meaning that the shot would have to come from the front of the motorcade, not the back. And that implies at least one more shooter.

Was the CIA involved? We’ll never know. Who could possibly be in better position to erase all traces of evidence than CIA itself? And what about Ruby's silencing of Oswald, and the mysterious death of a woman journalist who had interviewed Ruby? And the unexplained death of one of JFK's long-term mistresses? And, some say, what about Marylin Monroe — was it really a suicide?

There is something very muddy about the sequence of events, and the mud has not settled over the many years — on the contrary, it’s become even more muddy. It’s time to let go of the hope of any clarity.

*

WHY ISLAM FORBIDS THE EATING OF PORK

Mohammed cribbed much of Islam, including the deity, from the Jews. And he included the Jewish proscription against eating pork.

This is actually ironic since so many of the laws in Leviticus were simply shibboleths that the priest class used to create tribal unity among the Hebrews, making clear distinctions between “us” and “them”. “We don’t eat pig like those Canaanite scum, we don’t wear blended fabrics, and unlike those schmucks on the coast, we’re really picky about our seafood.” They sold it to the people by claiming that the deity said so.

So the Muslims bought in to the what, without knowing why.

EDIT: No, no, no. It had nothing to do with health. Every other tribe in the Middle East ate pig, and were just fine, thank you very much. It seems that they all had kitchens, and knew how to cook. The pork proscription was purely a shibboleth.

*Shibboleth — a custom, principle, or belief distinguishing a particular class or group of people, especially a long-standing one regarded as outmoded or no longer important.

Shibboleth has a long and dark history, beginning with the origin of the term in the Hebrew Bible, where it appears in the account of a battle between the Gileadites and Ephraimites. The Gileadites won the battle and the remaining Ephraimites tried to flee. The Gileadites secured the escape route and stopped each person passing to pronounce Shibboleth, a Hebrew word for the kernel of a grain. Those who could not pronounce the word correctly were slaughtered.

There are many similar examples in history where the pronunciation of a difficult word has been used to identify nationality, ethnicity, or background. This is often done for some negative reason such as discrimination.

https://simplicable.com/new/shibboleth#

Oriana:

In Polish the word would probably be CHRZĄSZCZ (cricket, the insect, not the sport) — or the entire phrase, W Szczebrzeszynie chrząszcz brzmi w trzcinie. (In Szczebrzeszyn, the cricket sings in the reeds.)

But the meaning is beside the point. It’s totally about the sound of all those piled-up consonants.

Szczebrzeszyński is an actual last name, which would be fit for a zealous customs employee like Officer Szymański at the US-Canada border, who interrogated me for a good half an hour before letting me return to the US (Canada didn’t even seem to notice my entry, never mind exit).

Don Stursma:

I subscribe to the theory that that pork was prohibited to prevent cultural contamination through associating — especially eating with other peoples. Originally nomadic pastoralists that pig raising was unsuitable for, the Hebrews did not have any history of eating pork so it would not be missed if they remained culturally apart.

*

SECULAR FAITH AND SPIRITUAL FREEDOM

Martin Hägglund argues that only atheists are truly committed to improving our world. But people of faith and socialists have more in common than he thinks.

~ Religious zealots are no longer the only ones to prophesy the apocalypse. Secular scientists and experts regularly warn us that the skies will fall, that plagues will overwhelm us, and that the seas will cover our cities—all of it well-deserved punishment for our sins. We live in an era in which traditionally sacred questions about the nature and end of our world have become political. The old firewall between faith and politics, so lovingly crafted in the eighteenth century to solve problems that are no longer ours, will likely come down whether we like it or not.

Martin Hägglund, a philosopher and literary critic at Yale, has published a book for this moment. This Life is an audacious, ambitious, and often maddening tour de force that argues that major existential questions—about the world and our place in it—must once again inflame our politics. What’s more, he presumes to answer those questions, providing an ambitious defense of secularism and a provocative attempt to link a secular worldview with a robust politics. To fully abandon God, Hägglund proposes, is to become a democratic socialist.

Few have tried harder than Hägglund to consider secularism’s political and ethical consequences. In a world in which Friedrich Nietzsche and Ayn Rand seem to have a stranglehold on the theme, this is a crucially important case to make, and to a crucially important audience. In the United States, and globally too, the number of religiously unaffiliated people grows by the year. This Life asks secular readers to take their own secularism seriously, reminding them that their worldview can and ought to influence their politics as fully as it might for religious believers.

He is not, to be clear, making an empirical claim that secularists are, in fact, the light of the world, but rather a normative argument that, if they understand themselves correctly, they should be. This aspect of Hägglund’s book is convincing, even if his kindred attempt to convince the religious among us to actually become secularists is less successful. Regardless, his project is to be applauded. Its iconoclasm and sweep provide an example of what intellectual activity can and should look like in an era of emergency.

This Life opens with an attack on religion, but of a novel sort. Hägglund is not much interested in whether or not God exists. He prefers to root out the more persistent belief that it would be a good thing if God existed. In his view, even many secular people are nostalgic for faith, and mourn the absence of a deity to command us and save us. This has kept the secular amongst us from deeply thinking through what it means to be secular—what it means, in other words, to accept that the lives we have here are the only ones we will ever have.

In Hägglund’s view, the essence of religion is a flight from finitude. He sees all religions as being basically the same in this regard, in that they all counsel us that the empirical world is essentially unreal. Our salvation, after all, resides in heaven or some kind of afterlife. Given that, the religious believer has no incentive to grant any independent significance to a particular human being, or even to the natural world. In his reading of Augustine, C. S. Lewis, Søren Kierkegaard, and other religious writers, he argues that they are intellectually committed to a devaluation of our shared, finite life. At the same time, he delights in offering evidence that these religious thinkers—despite themselves, in his view—granted meaning and significance to the finite world and its denizens.

His purpose is not merely to root out perceived hypocrisy, but to buttress the claim that devotion to the finite, or what he calls “secular faith,” is intrinsic to what we are as human beings. This anthropology is taken up in the second half of the book, which is devoted to what he calls “spiritual freedom.” In these chapters, Hägglund asks some basic questions: What would be the political and social consequences of true atheism? If we truly are alone in the world, what would it mean for us? These only seem banal because so few writers have the audacity to pose them so baldly.

The answers certainly are not banal: starting from first principles, Hägglund seeks to reconstruct what a worthwhile human life might look like, and what institutional arrangement might make it possible. The most interesting feature of his analysis is the great attention he gives to temporality. It is not just that human beings are “rational animals,” as Aristotle put it, but that our rationality expresses itself first and foremost through our decisions about how to use our time (hence the importance of finitude as a category).

This is less an ethical principle than a meta-ethical one. We can debate endlessly over whether we should devote ourselves to art, or love, or political organizing. Hägglund simply wants us to see that these debates hinge on how to spend our time.

Time, not carbon or land, is the raw material of our humanity. With this insight in hand, Hägglund turns his attention to the state of our shared world now—one that is organized around literally inhuman premises. If our freedom is defined by the rational use of our time, capitalism is defined by its irrational waste.

In an era of what David Graeber calls “bullshit jobs” and increasing awareness of the crushing requirements of modern labor, there is something plausible about this as a sociological observation. Hägglund presents it as a theoretical insight, too. In all of the excitement over the revival of socialism, it can be easy to lose sight of what capitalism actually consists in—or at least, how Marx understood it. Hägglund reminds us that Marx understood capitalism primarily through temporal categories. The historical significance of wage labor, after all, was precisely its linkage between monetary remuneration and the iron progress of the clock.

This linkage between value and labor-time, codified into the wage, distinguishes capitalism from alternative economic forms. It explains why the explosive technological innovations of the modern era, celebrated by Marx and Hägglund alike, have not shortened our labor time appreciably. And it explains why unemployment is immediately classified as a problem, instead of celebrated as evidence that we can feed and clothe ourselves with less labor than before.

In short, Hägglund believes that we are defined by the way that we spend our time, but that we are enmeshed in a system that devours our time without our rational input.

The only solution, therefore, would be to remake our economic system in a way that honors our finite time precisely by disaggregating the equation of time and economic value that is the hallmark of capitalism.

The book concludes with a robust vision of democratic socialism in which time, and not just capital, serves as a resource to be cherished and distributed. Hägglund is not opposed to the welfarist measures that constitute the horizon of democratic politics today. He does, though, think that they are inadequate given the magnitude of our crisis; they do not arise from a fully articulated philosophy of what man is, and what sort of world would be fit for her flourishing. More pointedly, he thinks that we are focusing too much on the mechanisms of redistribution, and not enough on the capitalist, temporal logic that governs the creation of value.

His form of democratic socialism essentially gives us back our time. The endless hours that are sucked into the maw of production can be ours, once again, if we have the courage to claim them. Partially, this involves the simple exploitation of technology to increase the amount of time we are away from work. It also, though, presumes the revaluation of work and the economy itself. He imagines a world in which our work is unalienated because we have freely chosen it, and because we understand how it contributes to a just world that we want to be our own. This is a world, too, in which we are not riveted to a profession forever, but can exercise our talents in diverse ways across our lives because we are not submitting our bodies to the dictates of the market.

This is a utopian vision, to be sure. Hägglund does not do the work to show how it might plausibly be on the horizon, or ask how it might be possible in a globalized economy where the most unsavory and dangerous sorts of labor are often outsourced. That, though, is the great virtue of the book: it provides a regulative ideal, and a reminder of what kind of world we are actually fighting for. However secular he might be, Hägglund’s is ultimately a project of restoring faith. And if the history of religion teaches anything, it is that faith is not created with concrete proposals. We have faith in a story, and in a promise, and this is what Hägglund seeks to restore to his secular audience. ~

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/james-g-chappel-martin-hagglund/

Mary:

Hagglund’s premise that the matter of humanity is how we spend our time is enlightening when considering how capitalism has bound time, labor and value in a knot heavy and fast as leg irons that bind us to an endless chain of hours not our own. The habits of a lifetime in these chains persist past your working years, everything still measured and ordered by the clock, accomplishment judged in terms of production, pleasure something we still feel we must measure, count, and account for. Time becomes a prison, not a gift... something to fill and use rather than enjoy.

*

LIBERATION THEOLOGY

Fifty years ago, religion met Marxism in the liberation theology movement.

~ In 1984, in the heat of the Cold War, leading neoconservative theologian and American Enterprise Institute fellow Michael Novak took to the pages of the New York Times Sunday Magazine to denounce the decades-old liberation theology movement. For its advocates, the movement was a method that put social emancipation, not the afterlife, at the center of Christian practice. For Novak, it was an unholy alliance between Marxist ideology and Christianity.

Novak detailed how idealistic Latin American clergy, nuns, and missionaries had all been duped by its fusion of religion and revolutionary thought. It had swindled U.S. politicians, too. When the likes of Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill challenged Ronald Reagan’s effort to cast the revolutions rocking Central America as existential threats to U.S. security interests, they were relying on liberation theology’s distorted account of reality, Novak contended. The stakes could not be higher. “If Marxism, even of a mild sort, flourishes” in Latin America and the Philippines, he warned, “and if it were to be officially blessed by Catholicism, two powerful symbolic forces would then have joined hands.”

Novak must have heard how Fidel Castro had discredited a center-right Cuban Catholic hierarchy as “Pharisees” and “white sepulchers” during a fiery August 1960 address. (“To betray the poor is to betray Christ,” Castro declared. “To serve wealth is to betray Christ. To serve imperialism is to betray Christ.”)

And he had surely seen the global outpouring of sympathy after the 1980 murder of El Salvador’s archbishop Óscar Romero at the hand of militias once supported by a U.S.-backed government. Romero had been a relatively conciliatory bishop before assuming the Church’s top post in El Salvador, where he grew increasingly frustrated with state violence and the government’s broken promises of reform and embraced liberation theology’s practical vision.

Romero’s political turn must have shown Novak what was dangerous about the movement: that it could radicalize the faithful, from young priests on the ground to members of U.S. Congress.

For Novak, one book in particular—“electrifying and seminal,” he had to admit—encapsulated the movement: Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez’s A Theology of Liberation, published in 1971 and first translated into English in 1973. (The translation was recently rereleased in a fiftieth-anniversary edition by Orbis Books.)

Born in 1928 of mixed Spanish and Indigenous ancestry, Gutiérrez studied in Louvain, Belgium, at the height of Francophone progressive theological influence in the post–World War II period; he counted among his classmates the Colombian priest and revolutionary Camilo Torres. When Gutiérrez returned to Peru, he sensed the excruciating disconnect between high theology and everyday realities. Surrounded by crushing poverty and anticolonial resistance, he grappled with where a traditional institution like the Catholic Church should stand. It was in these conditions that A Theology of Liberation was born, melding rigorous biblical interpretation, social science, and a vision for social justice.

In the United States today, organized Christianity is mostly associated with restrictions on reproductive autonomy, countermajoritarian and white nationalist agendas, and an embrace of free enterprise economics (even though it has also played a central role in civil rights and progressive movements throughout U.S. history). A Theology of Liberation, by contrast, represents a tradition that put religious reflection at the heart of the struggle of the global poor. By embodying ambition instead of compromise, it also offered an alternative to the schismatic tendencies of multicultural liberalism.

The book is a product of the concerns of its time; it was published years before women and minority voices began to shape the terms of broad political debate. Some of the social and economic crises it combatted—military rule and armed revolutions—are thankfully, for now, in Latin America’s past. But others—issues of economic dependence, political and cultural oppression, and glaring inequalities—remain, and so too does its influence.

A Theology of Liberation combines multiple publications and talks Gutiérrez gave in the 1960s after the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and in the run-up and aftermath of its Latin American successor, the Second Latin American Episcopal Conference (1968) in Medellín, Colombia. The two conferences, which Gutiérrez attended as a theological consultant, sought to guide the Catholic Church in a comprehensive response to a globalizing and modern world.