skip to main |

skip to sidebar

A bookstore in the ruins of Warsaw, 1945; photo: K. Szczeciński (don't even try). The sign says: Sheet Music - Books. I find it very moving that in such desperate conditions, literally in the ruins, people would try to find books — definitely including poetry.

A bookstore in the ruins of Warsaw, 1945; photo: K. Szczeciński (don't even try). The sign says: Sheet Music - Books. I find it very moving that in such desperate conditions, literally in the ruins, people would try to find books — definitely including poetry.

*

NEAR THE PALACE OF CULTURE

I never told anyone: the first time

I took a taxi by myself —

twelve years old,

waving my shaking hand:

“To the Palace of Culture” —

near the plaza theaters

adorned with the colossal

bas-reliefs of workers and peasants,

the driver veered away

from the rushing wide avenues

into a silent part of town

no buses or streetcars entered.

The streets were lined

with gutted buildings,

charred stumps of walls

singed with the shadow of fire.

I couldn't speak: my mouth ran dry,

my heart pounded as if trying to leap

from its scaffolding of bones.

I looked at the empty window frames,

doors to nowhere

standing by themselves;

a stairway climbing

into jagged air.

An old man in a black coat, black hat

suddenly stepped through a hole

from the raw space inside,

poking with his cane

into a heap of loose brick,

tapping against a torn pipe.

No one told me; I didn’t yet know

those were the ruins

of the Jewish Ghetto.

The gaping doorways

were entrances to hell.

~ Oriana

Warsaw 1946; photo: Michael Nash. This is so human, this bit of “fake news” as practiced by old-time photographers.

Cleaning up after a war takes time. If the devastation is overwhelming (the initial plans were simply to abandon Warsaw and move the capital to Krakow — but the returning inhabitants simply began cleaning up the rubble), and if the country isn’t rich, it can take years. Still, I couldn’t figure out why a certain area near the Palace of Culture — prime real estate in the center of the city — was left as ruins for so many years, a surreal ghost town. Only during my first trip back, when I learned that this had been the Jewish Ghetto, did it dawn on me that perhaps I wasn’t the only one to feel so much horror just being there that perhaps people didn’t want to go near.

Warsaw 1946; photo: Michael Nash. This is so human, this bit of “fake news” as practiced by old-time photographers.

Cleaning up after a war takes time. If the devastation is overwhelming (the initial plans were simply to abandon Warsaw and move the capital to Krakow — but the returning inhabitants simply began cleaning up the rubble), and if the country isn’t rich, it can take years. Still, I couldn’t figure out why a certain area near the Palace of Culture — prime real estate in the center of the city — was left as ruins for so many years, a surreal ghost town. Only during my first trip back, when I learned that this had been the Jewish Ghetto, did it dawn on me that perhaps I wasn’t the only one to feel so much horror just being there that perhaps people didn’t want to go near.

Eventually, of course, this area too got rebuilt. I am amazed that circumstances (including a taxi driver who said he wanted to avoid traffic) still granted me a glimpse of it.

Monument to the Heroes of the Ghetto Uprising (news photo, May 2011)

Monument to the Heroes of the Ghetto Uprising (news photo, May 2011)

WHAT GOOD IS HEAVEN WITHOUT ART?

If I were brought across the sea to Paradise

and forbidden to write, I’d refuse Paradise,

since what good is heaven without art,

which has a joyousness beyond the self?

(lines from a poem by Edward Hirsch, "Marina Tsvetaeva")

I’ve often thought about it: for me the only heaven would be the kind in which I could do some meaningful work. It wouldn’t have to be writing, but I can see that for my younger self, completely in love with poetry, it would indeed need to be writing, or I’d be dejected and begging to be returned to my desk.

These lines in the poem also fascinated me:

When you love a person you always want him

to disappear so your mind can work on him.

The imagination is a storm-cloud of rapture . . .

~ Edward Hirsch, in the volume "On Love"

I wouldn’t insist on “always,” but most of the time. For me being able to relive the experience, to meditate on it, has been as important as the experience itself — sometimes more so.

A cherub with cherubic clouds

A cherub with cherubic clouds

THE WAR ON FACTS

"The best way to keep a prisoner from escaping is to make sure he never knows he’s in prison.” ~ Fyodor Dostoyevsky

You simply feed him “alternative facts.” The prisoner needs to think he is in paradise!

Compared to the War on Facts, all other “wars” are secondary. Orwell understood this perfectly. All successful dictators understand this.

CHAIRMAN MAO’S WAR ON FACTS

~ “The Long March” by Sun Shuyun (Doubleday, 2007). In 1934, surrounded by Chiang Kai-shek’s forces in the south, Mao’s Red Army marched more than eight thousand miles to a new base, in the northwest. The march, completed by only a fifth of the original army, was a defeat in all ways but one: it returned Mao from the political wilderness to power.

Mao transformed the march into the founding myth of modern China and, in doing so, created a new narrative around victories that never happened. Shun, a Chinese-born BBC documentary producer, retraces the route and interviews the few remaining survivors, in an account that shows the human cost of Mao’s revisionism. Along the way are huge memorials to spurious victories and countless unmarked graves of those who died in defeats that Mao later denied. (New Yorker, July 30, 2007)

The Prisoner by Nikolai Yaroshenko, 1878

The Prisoner by Nikolai Yaroshenko, 1878

~ “Mr. Samsa smart to throw apple at disgusting cockroach son, any father would. My sons will never turn into anything.” ~

Of course it’s expecting too much to assume that Trump is familiar with Kafka, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Dickens, and other classics. He may not even know children’s literature like Winnie the Pooh. That kind of psyche is not shaped by literature, which has been shown to expand empathy.

(This is a cut and paste from a recent article in the New Yorker.)

@realDonaldTrumpWeak Hamlet should stop moaning about past and get on with his life. All talk, no action! King Claudius has my full support.

@realDonaldTrumpTremendously fat honey thief Winnie-the-Pooh deserves to get stuck in Rabbit’s hole. Not crying for him, believe me, or low-energy Eeyore.

@realDonaldTrumpSmall farmers need our support not meddling spiders ruining livestock sales. Creepy Charlotte should stick to catching flies!

@realDonaldTrumpSuccessful businessmen should be left alone by boring ghosts and sad employees. Bob Cratchit is a loser. No enthusiasm! Also . . .

@realDonaldTrumpTiny Tim is a lazy con who manipulates media with whining. He should save “blessings” for himself. Pathetic!

@realDonaldTrumpLittle Miss Muffet doesn’t deserve curds or whey if she can’t deal with a bug. No strength or stamina and her tuffet is a disgrace.

@realDonaldTrumpDeport Don Quixote with fat idiot Sancho Panza. We have enough problems without terrorists attacking energy plants.

@realDonaldTrumpNo one is saying Owl and Pussycat can’t be together, just don’t rub it in our face. And the boat is an embarrassment!

@realDonaldTrumpKnow from much experience Eastern European women are the most faithful in the world. Cheating Anna Karenina makes me sick!

@realDonaldTrumpAnyone who thinks a good relationship with Mordor is a bad thing is stupid. And crooked Frodo should return ring to rightful owner.

@realDonaldTrumpWolf well within rights to evict disgusting pigs from below-code structures.

@realDonaldTrumpOverrated king’s horses and men are failed élites. Humpty Dumpty deserves better and will get it after Obamacare repeal.

@realDonaldTrumpVery Little Jack Horner’s biggest accomplishment: putting in thumb, pulling out plum. Sad!

@realDonaldTrumpStepsisters deserve compensation for loss of employee. Shame on you, prince!

@realDonaldTrumpMr. Samsa smart to throw apple at disgusting cockroach son, any father would. My sons will never turn into anything.

@realDonaldTrumpBetter British schools and Hogwarts would fail on its own. Instead, England has disastrous witch problem. i won’t let it happen here!!!

@realDonaldTrumpFeel bad for amazing candy house after disgusting fat pigs Hansel and Gretel got through with it. Not nice! Admire witch’s restraint.

@realDonaldTrumpRumpelstiltskin made a very smart business deal with miller’s daughter, distorted by fake news media.

@realDonaldTrumpHumbert Humbert is a degenerate and should be jailed. Also, Ivanka is ten times hotter than Lolita.

@realDonaldTrumpHare was cheated in rigged race! Low-energy Tortoise continued during rest breaks. Not fair!

Oriana:

The line between satire and reality is no longer easy to discern. Trump’s tweets can be so surreal that it’s difficult for comedians to compete. He lives in his own version of reality, and the danger is that that alternate reality, repeated often enough, might begin to displace the actual.

At the same time, to a writer, he’s addictive — it seems like great material. But we should do some hard thinking about whether to keep giving him such wide exposure.

**

The Charlatan; school of Bosch, early 1500s

The Charlatan; school of Bosch, early 1500s

**

The Charlatan, Pietro Longhi, 1757

The Charlatan, Pietro Longhi, 1757

CAN WE OUTGROW A LANGUAGE?

The Latvian student was struggling with his assignment. I had asked all the students in my writing class at Maastricht University in the Netherlands — where instruction was in English — to translate one of their stories into their native language.

The Latvian student, B., was one of 23 who had signed up for the first year of creative writing minor I had designed for the university. This inaugural class comprised one of the most linguistically diverse groups I had ever taught. Only one — my single American — was monolingual. The rest spoke 12 different languages among them. For most of my students, English was their second or third language and yet they used it beautifully, writing stories and poems that were among the most interesting I had come across as a teacher of writing.

So I was surprised to discover that this last assignment requiring them to write in the language they had first spoken was especially difficult. Like B., many students found it nearly impossible to complete.

B. had been born in Latvia and had moved to the Netherlands with his family around the age of 10. He had already written an accomplished, rather adult story, a gothic tale involving a bit of violence and a bit of love. The translation assignment nearly did him in. He was in my office every week, unable to start the project, and then when he did, unable to make any progress. Finally, I asked him to try to pinpoint what was the root of his problem. He thought for a moment and then lit up.

“The problem,” he explained, “is that this is a very dark story and Latvian is just not that kind of language.”

I asked him what he meant.

“You see,” he replied. “Latvian is a very sweet and beautiful language.”

A sweet and beautiful language. I smiled. And then gently broke it to him that it’s not the language that was sweet and beautiful; it was the 10-year-old boy who stopped using it exclusively when he acquired a new one. He was able to finish his translation after that. But I don’t know if he ever quite believed me. Latvian will always remain for him the sweet and innocent language of childhood. As it probably must.

**

A similar thing happened when I taught a different workshop in Miami in 2014. Though many students spoke other languages, all wrote exclusively in English. I asked why. A student whose parents were from Gujarat explained.

“I’ve talked about this with my other friends,” she said. “None of us write in Gujarati because it’s not a nice language for us.”

I asked why. And after a moment of thought, she said, “Because it’s the language of scolding!”

Today, I ask my classes to reflect on what language means to them. I ask how many now use a language different from the one they grew up speaking. I ask: What is your language of scolding? What is your sweet language?

**

Eva Hoffman in her memoir Lost in Translation writes about emigrating from Poland to Vancouver at the age of 13 and encountering the shock of the new language.

She writes: “The problem is that the signifier has become severed from the signified. The words I learn now don’t stand for things in the same unquestioned way they did in my native tongue. “River” in Polish was a vital sound, energized with the essence of riverhood, of my rivers, of my being immersed in rivers. “River” in English is cold—a word without an aura. It has no accumulated associations for me, and it does not give off the radiating haze of connotation. It does not evoke.”

And yet, as an adult, she chooses to write in English. “If I’m to write about the present, I have to write in the language of the present, even if it’s not the language of the self.”

Later, she realizes that each language “modifies the other, crossbreeds with it, fertilizes it. Like everybody, I am the sum of my languages.”

In her essay collection Create Dangerously, Edwidge Danticat comes to a similar conclusion:

One of the advantages of being an immigrant is that two very different countries are forced to merge within you. The language you were born speaking and the one you will probably die speaking have no choice but to find a common place in your brain and regularly merge there.

For me, language was a kind of initiation into multiple realities. For if one language could be certain of a table’s gender and another couldn’t be bothered, then what was true of the world was intimately tied, not to some platonic ideal, but to our way of expressing it.

That, to me, is the great gift of bilingualism. And I usually begin a workshop by asking students to translate a short poem into their native tongues (I usually use Alfred Tennyson’s “The Eagle,” after I learned to translate it in a charming workshop given by the Dutch poet Wiel Kusters). Those students who do not speak another language are asked to rewrite the poem without using the letter “e”, a translation hurdle in itself.

To translate, one must really understand what is being said. The translator crawls inside a text and inhabits it in a way not even the careful reader can. This is why every writer must read as the translator does.

In the 20th century, some of the most celebrated figures in literature were multilingual, either through exile, immigration, colonialism or family circumstance.

Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote his first novels in Russian, became an international star after he started writing in English. Jorge Luis Borges spoke English as a child and wrote in Spanish. The Irish Samuel Beckett, who studied English, French and Italian at Trinity College, wrote his most well known work in French, preferring that language because, as he famously noted, it allowed him to write “without style.”

This list grows longer towards century’s end when we add the refugees of the era’s great upheavals: Eva Hoffman, Charles Simic, Anchee Min, Edwidge Danticat, Milan Kundera, Nuruddin Farah, and Amin Maalouf, to name just a few. Many of them, like my uncle Dionisio Martinez, left their homeland in their early teens and went on to write in the language of a new land.

http://lithub.com/are-we-different-people-in-different-languages/

Finnich Glen, Loch Lomond, Scotland

THE SIXTIES: A DEVELOPMENTAL CROSSROADS NOT TOO DIFFERENT FROM THE TWENTIES

Finnich Glen, Loch Lomond, Scotland

THE SIXTIES: A DEVELOPMENTAL CROSSROADS NOT TOO DIFFERENT FROM THE TWENTIES

~ “I've been thinking recently about sixtysomethings and how much they're like twentysomethings.

Author and photographer Bill Hayes calls it the Post-Anything-Is-Possible stage. A few months ago he wrote a New York Times op-ed about the relief it brings. When you're middle aged, he wrote, certain doors have finally and irrevocably closed: you won't ever have that baby or become a doctor or sail solo around the world. There's an upside to the loss of these dreams. "When possibilities stop being endless," Hayes wrote, "you can narrow the choices. Indeed, you can make hard choices, without resorting to dreams, without relying on maps, without abandoning duty. Is that not what wisdom is? Knowing when to unload what one will not need or use before approaching the next bridge."

The prolongation of the lifespan has led to a reassessment of all the traditionally-understood stages. And just as the transition between adolescence and young adulthood has become more elastic, arguably creating a new developmental stage between ages 18 and 29 that some are calling "emerging adulthood," so has the transition between middle age and old age begun to transform.

No one has given it a formal name yet, but people are definitely studying it. The same kind of scholarly consortium that looked at the "transition to adulthood" was also created to investigate "Midlife in the United States" -- in both cases, a group of scholars united into a professional network sponsored by the MacArthur Foundation. And in the case of midlife, the resulting publications have led to the overall impression that midlife (which they define as 40 to 60, younger than the important decade I'm talking about here) is a time of psychological turning points, growth, and — despite the conventional wisdom and my own idiosyncratic hang-ups — overall happiness.

Mary Catherine Bateson, the daughter of Margaret Mead, followed her mother's lead in thinking about how societal roles affect individual's psychological development. The lengthening of overall life expectancy, she writes in Composing a Further Life: The Age of Active Wisdom, has "opened up a new space partway through the life course, a second and different kind of adulthood that precedes old age." Not only are the ages between 60 and 70 changing, according to Bateson, but so is every other stage of life as a result, the ones that come before as well as those that come after. She thinks of the sixties as the dawn of a period of life she calls "Adulthood II." I like that way of looking at it.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/cusp/201301/sixtysomethings-and-twentysomethings

Oriana:

Twenty-somethings are beginning to work in earnest while sixty-somethings are retiring from working for a living — and in some cases, beginning to live as they always wanted to, becoming so busy that they can’t understand how they ever managed to hold a job. But it’s not always an easy transition. For some, the freedom turns into boredom — though it seems that eventually most people work out a new schedule of activities. But I’ve seen sad examples of men mowing the lawn into the ground and pruning trees that don’t need pruning just to appear useful. The lucky ones have developed satisfying pursuits while still employed.

I've noticed that the term "the Golden Years" is hardly ever used anymore. Yet the part of older age when health is still sturdy can really be that. Of course we are assuming no financial hardship. Older often means richer — another pleasant surprise.

And for women, it can mean the autonomy of widowhood, finally being fully yourself and living for yourself — without having to take care of someone else. You stop being such a people pleaser. Let’s face it — such a slave.

In the best-case scenario, you discover the bliss of being “posthumous”: the stage of life where you no longer feel you “should” do anything. Been there, done that. It’s an incredible relief to realize that I’ve been in over 100 magazines, so I don’t need more magazine publications. I’ve published, I’ve won awards, it’s enough. I may *choose to* work on creative projects, but I no longer have to to accomplish anything — what relief! Likewise, it’s no longer possible to have a child, so the torment caused by the idea that I “should” have at least one is history. This is the gift of growing older: torment and anxiety fall away because possibilities close — and that’s fantastic!

I realize that I protest too much. Poetry was indeed agony and ecstasy — and I do miss the ecstasy part, now much attenuated. I loved my passionate commitment to poetry, even if at times it felt like enslavement and demonic possession. The challenge of the transition is to work out a new mode of living that is not all mundane and same old, same old.

WHY THE SECOND HALF OF LIFE IS HAPPIER FOR MOST PEOPLE

In Sonia Lubomirsky’s “The Myths of Happiness” I found the predictable section “The best years are in the second half of life” — with one finding that was new to me. The most frequent explanation for increased happiness in older age is “when we begin to recognize that our years are limited, we fundamentally change our perspective about life.” We invest more in things that truly matter and make it a priority to enjoy the present. We choose peacefulness over risk and excitement. We focus on positive memories. We have more wisdom and better social skills — and so forth.

OK, here is something obvious that I didn’t expect: “The older we are, the more likely we are to be treated with respect and kindness. Others confront and criticize us less, acquiesce to us and forgive us more, and work hard to resolve tensions and de-escalate conflicts.”

That’s certainly been true in my life. In my youth I used to be criticized and attacked all the time. This has certainly calmed down. True, I’ve withdrawn from participating in poetry workshops and other poetry events where I was most likely to encounter unpleasantness. I’ve learned how to block the nasties on Facebook. But even so, I’d say that Lubomirsky’s conclusion holds. And when I look at the really old ladies, who can be oh so very slow, I'm struck by the patience with which they are treated by cashiers, say. Somehow no one tells grandma to hurry up and make up her mind. It seems to me that we’re as indulgent toward the really old as we are toward little children — perhaps even more so.

Silence is one of the great arts of conversation. ~ Cicero

What do you mean, “But is it art?”

What do you mean, “But is it art?”

THE END OF THE “AMERICAN CENTURY”

~ “In 1941, a year before America entered World War II, Henry Luce, the founder and publisher of Time, wrote an essay called “The American Century.” It was an argument not just against isolationism but for America as a global moral beacon. Luce, the son of American missionaries to China, wrote that America must “accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence exert upon the world the full impact of our influence.” That vision, he wrote, was only possible if it reflected “a passionate devotion to great American ideals.” He enumerated them as a love of freedom and justice, equality of opportunity, and a commitment to truth and charity and cooperation.

The inaugural address of Donald Trump did not contain the word justice or cooperation or ideals or morals or truth or charity. It has only one reference to freedom. It did mention carnage and crime and tombstones and a variety of words never uttered before in a presidential inaugural. Since then, the president has doubled-down on his desire to build a wall on America’s Southern border and has said his administration will re-evaluate accepting refugees from designated Muslim countries and cut back by half the relatively small number of refugees accepted by the Obama administration.

I spent seven years as editor of Time before I worked in the State Department as under secretary for public diplomacy and public affairs. While I was editor of Time, I never wanted to be the first of Luce’s successors to pronounce the end of the American Century. In part, this was because of a misunderstanding of the term. Most people thought it meant American power or hegemony and there was not much diminution in America’s global power. What it really means is America as a global model and guarantor of freedom and rule of law and fairness.

Trump’s vision does not spell the end of American power, but a retraction of American influence. It suspends American involvement as a global leader on global decision-making for a resolute policy of non-interference. At the State Department, when I traveled abroad for discussions with another nation’s government, I talked not only about agreements and exchanges and trade deals, but also about freedom of religion and expression, transparency, and rule of law. I sat in diplomatic “pull-asides” with President Obama and Secretary Kerry and foreign heads of state where they talked not only about America’s interests but universal values—free expression, religious liberty, rule of law.

I sat next to Kerry as he demanded the release of political prisoners and journalists who were behind bars. These were uncomfortable discussions. I once had an African foreign minister say to me with a touch of annoyance: “You come and talk to me about transparency, but the Chinese come and build a super-highway.”

And that was often the case. And no other nation, I promise you, ever talked to that foreign minister about transparency. That is America’s strength, not its weakness. The Chinese, and now the Trump administration, will resolutely practice non-interference in other nations’ affairs. America First is not a policy that any of our allies around the world want to hear. Our adversaries are delighted. Our power and influence with our friends and adversaries came in large part because we were the one nation that did not always put ourselves first.

American presidents operate along the realistic and idealistic sides of the foreign-policy continuum. But ever since Woodrow Wilson, Americans have always seen themselves as being the moral beacon that Luce talked about all those years ago. As Obama has said many times, our ideals are our policy. Trump appears to see those ideals as, at best, irrelevant, and at worst, effete.

Having traveled around the world on behalf of the State Department for the past three years, I can promise you that governments do not worry that America is too engaged—they worry when we disengage. And wherever we may disengage around the world, we are never replaced by a better actor. The president’s vision of putting up our national drawbridge and hunkering down mirrors the transformation of Great Britain to Little England after the end of World War II. The American Century was a term of pride for many and it represented the flowering not only of American power but American values.

That seems to have ended beginning last Friday.” ~

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/01/end-of-the-american-century/514526/

Oriana:

Of course all empires end, but what follows is not necessarily better.

*

DIFFERENT GOSPELS, DIFFERENT MEANING

*

DIFFERENT GOSPELS, DIFFERENT MEANING

~ “The author of Mark (who, by the way, was not really an apostle or named Mark) was most likely writing to a community that lived through the time of the Jewish revolt (and subsequent massacre). They also knew that, during his lifetime, Jesus was understood by his followers (even his disciples) to be the Jewish messiah—not one equal to God himself, but a figure like King David who would overthrow the Roman rule and usher in the Kingdom of God. But, they wondered, how could he be the messiah given that he was crucified? Mark gives them an answer: because no one at the time understood what it meant to be the messiah. Before Jesus was to usher in the Kingdom, God intended for him to suffer and die “as a ransom for many.” Only later would he return to establish the Kingdom.

Why didn’t people realize this at the time? Mark reinterprets (misremembers) Jesus’ life to make sense of this. Mark says that Jesus intentionally kept his mission a secret; and he did tell his disciples, but they were just too dumb to understand. That’s why Jesus death was such a surprise to everyone. Mark seems to be letting his readers in on this secret for the very first time. He is reinterpreting what it means to be the messiah, and misremembering Jesus life to fit into that interpretation.

According to Mark, God’s plan also included a subsequent era in which followers of Jesus would suffer just like he did (which Mark’s community was currently experiencing). But not to worry, says Mark. Jesus will be returning soon, in judgment, to fulfill is ultimate goal as messiah and finally establish God’s Kingdom on Earth. That’s the promise God had made, through Jesus, to the Christian community…according to Mark.

The gospel of John, on the other hand, is written (again, not by John) in a completely different era—an era when the early Christian expectation of the Jesus’ “imminent return” was nearly a century old and thus beginning to look a bit silly. As a result, John remembers Jesus’ life in a completely different way. Although John still thinks part of Jesus’ mission is to suffer and die, Jesus’ ultimate goal is not to overthrow Roman rule and establish an Earthly Kingdom of God. That’s not the promise John’s Jesus makes. He instead promised his followers eternal life after death. Think John 3:16.

To make this offer, Jesus must be one with God himself. And so in John, Jesus doesn’t keep his mission or his true nature a secret, like he does in Mark. In John, the main purpose of his ministry is to declare who he is (one with God himself), prove it by performing miracles,[26] and then do what is necessary to grant this enteral life to his followers by suffering and dying. The resurrection is the final proof that he was telling the truth.

Ehrman draws an analogy between how Mark and John remembered Jesus and how people in the American North and South remember the civil war. For the former, it was a war brought on by southern rebellion, motivated by their desire to keep slavery legal. For the latter, it was the war of northern aggression, motivated by their desire to keep southern states from governing themselves. Same war, different memory.

For Mark, Jesus was someone who would deliver his community from their suffering and bring judgement on the political authorities who were suppressing them. For John, Jesus was someone who promised and provided the means to eternal life. Same guy, different memory.” ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/logical-take/201604/book-review-bart-ehrman-s-jesus-the-gospels

Oriana:

Ehrman sees the “historical Jesus” (he opposes mythicism) as one of many apocalyptic preachers common around that time. Not that he thinks we can reliably extract a historical Jesus from the gospels (including those gospels that didn't make it to the canon), but he thinks there is a certain “gist” in those stories that adds up to an apocalyptic preacher.

The gospel of John, however, strikes out in a new direction, more relevant to the times and

less Judaic. The promise of the Second Coming is now displaced in favor of eternal afterlife. Of course what really happened is that instead of the Coming of the Kingdom we got the Coming of the Church . . .

We are long-eared owls. Short-eared owls are “alternative owls.”

We are long-eared owls. Short-eared owls are “alternative owls.”

ending on beauty

The forest, letting me walk among its naked

limbs, had me on my knees again in silence

shouting — yes, yes my holy friend,

let your splendor devour me.

~ Hafiz

FROM EVA BRAUN

There are only two beings I trust:

my dog and Eva Braun.

~ Adolph Hitler

When Hitler was away, which was constantly

I ate my meals alone with his photograph

propped across from me on the table.

In public I had to address him Mein Führer.

Afraid I’d slip, I called him Mein Führer

even in the bedroom.

*

I disobeyed him only in one thing,

He detested smoking; I smoked on the sly.

Once he unexpectedly walked into the parlor.

I put my cigarette under my skirt

and sat on it, chirping like a cheerful little bird

while the smoldering butt went on burning

my most sensitive flesh.

*

Against his orders I came to Berlin:

“‘Do you think I’d let you die alone?” —

the only time he kissed me

on the mouth in public.

Russian shells were falling near the Chancellery.

Hitler said in a chair, with trembling hands

stroking a puppy in his lap. He told me

his secret dream: after the war,

to live with me in a small Austrian town,

and give himself to art.

*

Hitler wore his military uniform,

I, a black taffeta gown;

the women in tears,

as always at weddings.

They said I looked radiant.

I began to sign with a B for Braun,

crossed the letter out;

for the first and last time,

signed myself Eva Hitler.

A moment later a bomb

hit the bunker’s roof;

flakes of cement from the ceiling

fell on us like deathly rice.

*

Hitler, though a tee-totaler,

drank a little Tokay wine,

joked with the guests, then walked out

to dictate his “Political Testament”:

The German people

have not proved worthy of me.

The phonograph played over and over

the only record there was,

Blutrote Rosen erzählen dir von Glück —

“blood-red roses tell you of happiness.”

There are many of us Eurydices,

dancing at our wedding in hell.

He said, I had one flaw as a leader:

kind-heartedness. Tell me,

do we choose the one we love?

*

“I want to be a pretty corpse,”

I said and chose cyanide.

Krebs had advised a pistol.

Hitler said, “I couldn’t shoot her.”

Three-twenty in the afternoon:

a shot,

swallowed up

by the bunker’s stifling walls.

When the two guards entered, blood

was still flowing from Hitler’s temple

onto his freshly pressed uniform.

Do we

choose the one we love?

I leave you with this

photograph of my life: my body curled

in the corner of the sofa,

my hand reaching for my Führer’s arm.

~ Oriana

She was 33 at the time of her double suicide with Hitler, on April 30, 1945.

She could have stayed away and saved herself. But . . . love.

And even though it’s Hitler, something in us is touched by the romantic gesture of his marrying Eva Braun the night before the suicide, and her refusal to let him die alone.

The poem presents a younger woman point of view: you don’t choose whom you love, no matter how destructive that man is to you. An experienced woman has learned to recognize red flags. Above all, she has accomplished a few things over the years, whether in terms of a career or motherhood or both, and values herself enough to guard against a destructive man (a malignant narcissist, for instance). True, the brain’s limbic system loves familiarity, but developing more awareness (generally the hard way, through a lot of suffering) can teach us how to escape the “fate” of imprinted childhood patterns.

As one friend of mine said, the first marriage is generally what New Age people euphemistically call a “learning experience.” But we don’t have to stay in hell (or Hitler’s bunker). Whether we sing our way out of it and find another means of escape, once we are ready for a mutually nurturing relationship, it awaits. First a nurturing relationship with oneself, discovering you’re your own beloved — then someone truly capable of loving, so you can “call yourself Beloved on this earth” — to quote Raymond Carver again.

This poem is part of a chapbook-in-waiting called The Dancing Eurydices. It seemed on schedule for getting published in time for my birthday in April, but . . . the best-laid plans hit a snag. So be it. Fortunately I'm well-indoctrinated by a friend who used to repeat: “It’s only a poem.” It’s only a chapbook.

It’s wonderful to have a different venue: a blog with an international audience. To all my readers: thank you.

**

Here is a painting with the theme of the Underworld, this time in the guise of Christ descending into Limbo ~ Andrea Mantegna, 1475

Mantegna also did an engraving of descent into Limbo that is perhaps more interesting than the painting.

Adam and Eve are about to leave Limbo, but the most interesting figure is the Devil, with a second face on his buttocks. Note that Adam seems to have aged while Eve has remained "ageless." By Martin Schongauer, late 1400s.

Adam and Eve are about to leave Limbo, but the most interesting figure is the Devil, with a second face on his buttocks. Note that Adam seems to have aged while Eve has remained "ageless." By Martin Schongauer, late 1400s.

SOUL AS AN APTITUDE TO TRANSFORM SORROW

~ “For Keats, who calls the world itself the "vale of Soul-making," the soul isn’t an eternal substance, but an aptitude — we cultivate it over a lifetime — for affirming the "Pains and troubles" of the world and transforming them into meaningful, potent aesthetic forms, which can be poems or paintings but also gardening and good parenting.

This soul-work is what differentiates us from one another, makes us "Identities," individuals. No one can suffer my pain but me, and my response to that is my singularity. The kind of self I make, base or noble, depends upon how I interpret my sorrow, whether narrowly or expansively.” ~

http://www.chronicle.com/article/Keats-s-Sensual-Shock/234901/

Roseate spoonbill; photo: Rachel Meadow

Roseate spoonbill; photo: Rachel Meadow

“THE MAN THAT HATH NO MUSIC IN HIMSELF”

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are dull as night,

And his affections dark as Erebus.

Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music.

~ Shakespeare in the voice of Lorenzo in The Merchant of Venice

[Erebus = darkness, sometimes personified as a deity, consort of Nyx, Night; also used as a synonym for the Underworld]

I was especially struck by the first line: “The man that hath no music in himself” — a soulless person devoid of the sense of beauty or subtlety; someone who does not relate to others or nature with empathy, tenderness, love.

Image: one of the couples here has music in them — do I hear “I’ve got you Babe”? I didn’t watch Trump’s Inauguration, both did watch both of Obama’s. What struck me most back in 2013 was the love between Michelle and Barack, their quick little kisses on the sly. Maybe this is the most important gift they gave to America: a portrait of a married couple who love

each other after many years.

MANIC LEADERS CAN BE EFFECTIVE IN TIMES OF CRISIS

~ “People with manic symptoms show less empathy for others, compared with those who suffer depression, who have increased empathy. You can draw inferences based on this observation, perhaps, for some of Mr. Trump’s policies, depending on your political viewpoint. Manic symptoms also are associated with impulsivity, an inability to hold back when one needs to hold back, which many commentators have observed in Mr. Trump’s debate performances, as well as in other aspects of his life, such as his sexual behavior.

So how does it all add up? Does he have the "temperament" to be president?

A few years ago, I published A First-Rate Madness, in which I argued that there are some positive benefits to manic-depressive illness. In particular, many of our greatest crisis leaders, like Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill, had a version of that condition. In contrast, some of our worst leaders, like Neville Chamberlain, were stable, personable, mentally healthy. Being “normal” is a drawback for crisis leadership, in times of great change. But in times of peace and prosperity, “normal” leaders do better, since all that is needed is moderation and caution at the helm. Churchill was a miserable failure in the British Cabinet in peacetime prosperity in the 1920s, while Chamberlain was a great success. When war came, the reverse was the case.

The question of whether Trump is the right man for the times is not really about whether he is psychologically “normal” or not, but whether we are in a time of the kind of crisis where a hyperthymic leader does best. One might argue that 2016 is much less a time of crisis than 2008, in the midst of the Great Recession and multiple Middle Eastern wars. If things are more stable than many believe, it could be that the hyperthymic leader would just cause more trouble, like Churchill in the 1920s, rather than solve the problems we have. In that case, Trump would be the wrong man for these times.” ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/mood-swings/201610/trumps-temperament-not-narcissistic-not-normal?collection=1098329

Oriana:

Oriana:

This is not the first time I see “manic” or “hypomanic” applied to Trump. What this article argues, and I suspect it's right on, is that in times of crisis a manic or a depressive person does better than someone mentally healthy (e.g. Neville Chamberlain). In "normal" times, a normal leader is best.

A manic person is shallow and lacks empathy; a depressive has increased empathy. It seems to me that politics is custom-made for those on the manic side. But it’s the fit with the times that decides a manic leader’s success or failure.

We tend to lament the fact that fools and fanatics are filled with certainty, which gives them strength, while the wise see a thousand shades of gray and can become paralyzed with doubt. Again, in times of war or an equivalent crisis, a fanatic can be a better leader.

NOT JUST EUROPE IN THE THIRTIES — FATHER CHARLES COUGHLIN ALSO WANTED TO “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN”

~ “Coughlin initially supported Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal, but most historians think the priest turned against FDR when the president failed to seek his religious counsel after winning in 1932. That’s when Coughlin turned his radio pulpit into a bully pulpit, calling Roosevelt “anti-God” and union leaders “Bolsheviks.”

In doing so, Coughlin turned away from the Left, seeking another way forward. Mussolini and Hitler — to whom Coughlin sent emissaries in the early ’30s — offered another direction. Coughlin started preaching about a new American order, with unitary strength at the top, single morality, deep suspicion of democracy, brute force toward socialism and taking back the country from “the interests.” He didn’t call it fascism, opting instead for “social justice.” But in the late ’30s Coughlin wrote that “the … principles of social justice are being put into practice by Italy and Germany.” He also targeted Jews, speaking about “international bankers” perpetuating the Depression and later accusing them of being Bolshevik insurrectionists.

In summer 1938, Coughlin’s newsletter serialized the anti-Semitic sham Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and in November that year, he argued that Germany’s Jews had brought Kristallnacht upon themselves. The start of World War II did little to dampen Coughlin’s enthusiasm for Germany and Italy. By this point, says Stanley Payne, history professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Coughlin was “the most important direct apologist for fascism in the United States.” And the radio priest made no secret of his hope that the British — still waiting for the U.S. to join the war at that point — would lose.

Despite Coughlin’s anti-Semitism, Catholic leaders seemed to fear that Coughlin was too popular to shut down. But by 1940, with American animosity growing toward the Axis, the Church finally acted, making Coughlin give up his microphone and, in 1942, halt production of his newsletter, forcing him back into private life as a priest outside Detroit.” ~

Oriana:

The Catholic church, an anti-democratic, authoritarian institution, was (and is) pro-fascist in some countries. Unquestioning obedience is a “virtue” demanded by the church. Fortunately in the US the church authorities finally turned against Father Coughlin. This was not necessarily a display of moral values as much as political cunning. The church tends to support the winning side, or the strong men already in power. Note the Russian Orthodox church’s support of Putin.

*

“In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” ~ George Orwell

“Trump’s real war isn’t with the media. It’s with facts. He needs to delegitimize the media because he needs to delegitimize facts. It’s not difficult to imagine the Trump administration disputing bad jobs numbers in the future, or claiming their Obamacare replacement covers everyone when it actually throws millions off insurance.” – Ezra Klein

~ When do you mean to cease abusing our patience, Trump ~ (changed to Trumpolina to rhyme with “Catilina” in the original quotation from Cicero)

To quote Latin in an anti-intellectual culture is an act of courage . . . though this certainly isn’t a Trump rally, where a display of education might possibly provoke assault.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS MARCH OF 1913

Over 100 years ago, another women’s march coincided with a presidential swearing-in, this time of Woodrow Wilson in March of 1913.

The parade was filled with pageantry. “Clad in a white cape astride a white horse,” writes the Library of Congress, “lawyer Inez Mulholland led the great woman suffrage parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in the nation’s capital. Behind her stretched a long line with nine bands, four mounted brigades, three heralds, about twenty-four floats, and more than 5,000 marchers.”

The parade drew a huge global coalition. It also drew ridicule, harassment, and violence from groups in DC for the following day’s festivities. As the Library of Congress writes:

[A]ll went well for the first few blocks. Soon, however, the crowds, mostly men in town for the following day’s inauguration of Woodrow Wilson, surged into the street making it almost impossible for the marchers to pass. Occasionally only a single file could move forward. Women were jeered, tripped, grabbed, shoved, and many heard “indecent epithets” and “barnyard conversation.” Instead of protecting the parade, the police “seemed to enjoy all the ribald jokes and laughter and in part participated in them.” One policeman explained that they should stay at home where they belonged.

Many marchers were injured; “two ambulances ‘came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor.’” The event included several prominent figures, including Helen Keller, “who was unnerved by the experience.” Also present was Jeannette Rankin, who, writes Mashable, “would become the first woman elected to the House of Representatives four years later.” Nelly Bly marched, as did journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, “who marched with the Illinois delegation despite the complaints of some segregationist marchers.”

In fact, though the selective images suggest otherwise, the march was more inclusive than the suffragist movement is generally given credit for. Over the objections of mostly Southern delegates, many black women joined the ranks. After “telegrams and protests poured in” protesting segregation, members of the National Association of Colored Women “marched according to their State and occupation without let or hindrance,” noted the NAACP journal Crisis. And yet, when the women’s vote was finally achieved in 1920, that general category still did not include black women. The misogyny on display that day was vicious, but still perhaps not as endemic as the country’s racism, which existed in large degree within suffragist groups as well.

Once the press broadcast news of the marchers’ mistreatment, there was a massive public outcry that helped reinvigorate the suffrage movement. Several other artists than McKay found inspiration in the march; Cleveland Plain Dealer cartoonist James Donahey, for example, “substituted women for men in a cartoon based on the famous painting ‘Washington Crossing the Delaware,’” writes the Library of Congress. Another cartoonist, George Folsom, documented the stages of the hike from New York, with captions addressed to male readers. The strip above says, “they are making history mates—be sure you save it for your descendants.” Another strip reads “Brave women all, none braver mates. Put this away and look at it when they win.”

http://www.openculture.com/2017/01/the-womens-suffrage-march-of-1913-that-overshadowed-another-presidential-inauguration.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+OpenCulture+%28Open+Culture%29

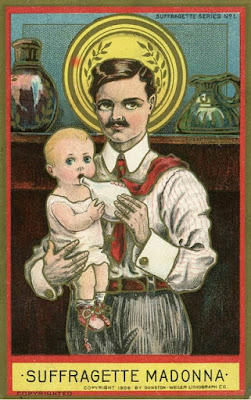

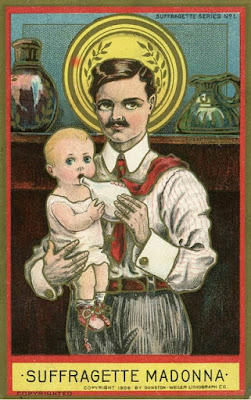

Special postcards were part of the anti-suffragist propaganda. This one caught my attention, in being so particularly out of date. Nowadays we think of a man holding a baby as an entirely natural and endearing image, but a hundred years ago it was regarded with horror.

DESIRE FOR SEX VERSUS CONVERSATION: WHAT CHANGES FOR TRANSGENDERED MEN AND WOMEN

~ Less interest in sex. “When I was a man,” one told me, “I thought about sex all the time, almost constantly. I experienced my libido as a driving force that sometimes felt irresistible. And if I didn’t get sex, I masturbated. I masturbated a lot. Now that I’m a woman, I still enjoy sex, but I think about it much less and masturbate less.”

More interest in conversation. “When I was a man,” this MTF transsexual continued, “my then-wife used to complain that I didn't talk with her as much as she wanted and that when we talked, I didn’t listen to her. As far as I was concerned, I talked and listened—just not as intently as she hoped. Now that I’m a woman, I see what she meant. I find men to be aloof and lacking verbally. Now, given a choice between having sex or talking with my girlfriends, most of the time, I’d choose the conversation.”

Chaz (nee Chastity) Bono, the daughter, now son, of singer-actress Cher and the late-singer-turned-politician Sonny Bono. As Chaz Bono transitioned, he noticed two main changes:

• More interest in sex. He says he thinks about it much more than he did as a woman and “needs release much more often.”

Less interest in conversation. “As a woman, I used to really enjoy dishing with the girls. As a man, I have less tolerance for women’s talking. I’ve noticed that Jen [his girlfriend] can talk endlessly. But there’s something in testosterone that makes that really grating. I’ve stopped talking as much. And when she talks, sometimes I just zone out.”

No doubt women will continue to complain that guys are horn-dogs, and men will continue to complain that women run at the mouth. But transsexuals show us that neither gender is out to drive the other crazy. It’s nothing personal, just our hormones.

It appears that about 1 percent of the population is potentially transsexual. And that 1 percent of humanity teaches the rest of us that key elements of gender identity—libido and conversation—are heavily influenced by our hormones.” ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/all-about-sex/201501/libido-conversing-what-transsexuals-can-teach-heteros

Oriana:

Oriana:

Women's levels of oxytocin, the pleasure and “trust” hormone, rise as much after talking as after orgasm.

THE DIRT ON QUEEN VICTORIA’S FAMILY LIFE

Though sexually infatuated, the young couple were locked into a power struggle. Albert took over more and more of Victoria's work as queen as her pregnancies forced her to step aside. Victoria was conflicted: she admired her “angel” for his talents and ability but she deeply resented being robbed of her powers as queen.

There were terrible rows and Albert was terrified by Victoria's temper tantrums. Always at the back of his mind was the fear she might have inherited the madness of George III. While she stormed around the palace, he was reduced to putting notes under her door.

Though she was a prolific mother, Victoria loathed being pregnant. Repeated pregnancies she considered “more like a rabbit or a guinea pig than anything else and not very nice”.

Breastfeeding she especially disliked, finding it a disgusting practice. And she was not a doting mother — she thought it her duty to be "severe". She didn't do affection.

Relations with her eldest son Bertie, later Edward VII, were especially fraught. From the start he was a disappointment for Victoria.

Like all the royal princes, he was educated at home with a tutor. Bertie did badly at lessons and his parents considered him a halfwit. Victoria remarked: “Handsome I cannot think him, with that painfully small and narrow head, those immense features and total want of chin.”

When Bertie was 19, he spent time training with the army in Ireland and a prostitute named Nellie Clifden was smuggled into his bed. When the story reached Albert, he was devastated and wrote Bertie a long, emotional letter lamenting his “fall”.

He visited his son at Cambridge and the two went for a long walk together in the rain. Albert returned to Windsor a sick man and three weeks later he was dead.

Albert probably died of typhoid. Another theory is that he suffered from Crohn's disease, but for years afterwards Victoria blamed Bertie for his death. She could not bear to have him near her. "I never can or shall look at him without a shudder," she wrote.

For the next 40 years — the rest of her life — Victoria wore black mourning and only appeared in public rarely and reluctantly. To her people, the tiny "widow of Windsor" seemed a pathetic, grief-stricken figure. The truth was very different.

Though Victoria was invisible, her need to control her children was almost pathological. She set up a network of spies and informers who reported back to her on her children's doings.

When Bertie married the Danish princess Alexandra, Victoria instructed the doctor to report back on every detail of her health, including her menstrual cycle. Court balls were scheduled so that they did not coincide with Alexandra's periods.

Victoria's eldest daughter Vicky married Fritz, the heir to the throne of Prussia, when she was 17. She was the mother of Kaiser William II.

Even in faraway Germany, Vicky could not escape her mother's interfering. Victoria wrote almost daily and her micromanaging made her daughter ill with worry.

When Vicky announced she was pregnant, Victoria replied: "The horrid news... has upset us dreadfully".

Vicky and her younger sister Alice, also married to a German prince, colluded to defy their mother. Secretly, they breastfed their babies. When Victoria discovered, she was furious and called them cows.

Victoria's changes of mind were bewildering and her rages could be terrifying. She was not only her children's mother but also their sovereign and she never let them forget it.

She kept her youngest child Beatrice (known as Baby) at home; she was terrified of her mother.

Victoria wanted Beatrice to remain unmarried. When Beatrice announced that she was engaged to a handsome German prince, Victoria refused to speak to her for six months and agreed only on condition that the couple lived with her.

Victoria controlled her sons just as tightly. Leopold, who inherited haemophilia, suffered especially. Victoria described him as "a very common-looking child".

She tried to make him live the life of an invalid, wrapping him in cotton wool. As a boy, he was bullied by the Highland servant who looked after him, but Victoria refused to listen to Leopold's complaints. She wouldn't let him leave home but he finally won the long battle to study at Oxford. He died aged 30.

She tried to make him live the life of an invalid, wrapping him in cotton wool. As a boy, he was bullied by the Highland servant who looked after him, but Victoria refused to listen to Leopold's complaints. She wouldn't let him leave home but he finally won the long battle to study at Oxford. He died aged 30.

Victoria wanted her sons to grow up like Prince Albert. The only one who resembled his father was Prince Arthur, the third of the boys, later Duke of Connaught. He was her favourite - he did what he was told and had a successful military career.

The son with whom Victoria quarreled most was the eldest, Bertie. She once remarked that the trouble with Bertie was that he was too like her. She was right. Like his mother, Bertie was greedy and highly sexed, with an explosive temper. But he possessed one supreme gift — personal charm.

As Prince of Wales, Bertie lurched from one scandal to another. In spite of his repeated requests, Victoria never allowed him access to government documents.

But the story had an unexpected ending. Bertie never broke off relations with his mother. When he eventually succeeded her as king at the age of 59, he did a very good job.

He modernised the monarchy, which was one reason why the British monarchy survived World War I when so many others did not. Perhaps Queen Victoria was not such a bad mother after all." ~

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20782442

Oriana:

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20782442

Oriana:

Victoria’s lack of affection as a mother seems convincing, given her own miserable childhood, at least in terms of her own mother. And it's true that being a “severe” parent was seen as a cultural ideal. What a revolution in attitudes we have witnessed . . . But the idea that children's primary need is to be loved rather than disciplined didn't quite catch on until after WW2, when psychology became an important field — and when the general standard of living went up.

ending on beauty:

For every bird there is a stone thrown at a bird.

For every loved child, a child broken, bagged,

sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children. I am trying

to sell them the world. Any decent realtor,

walking you through a real shithole, chirps on

about good bones: This place could be beautiful,

right? You could make this place beautiful.

~ Maggie Smith, Good Bones

Barack Obama as a child and his grandfather. You can see the grandfather's face in the adult Obama's face. The love goes on.

AT NORTH FARM

AT NORTH FARM

Somewhere someone is traveling furiously toward you,

At incredible speed, traveling day and night,

Through blizzards and desert heat, across torrents, through narrow passes.

But will he know where to find you,

Recognize you when he sees you,

Give you the thing he has for you?

Hardly anything grows here,

Yet the granaries are bursting with meal,

The sacks of meal piled to the rafters.

The streams run with sweetness, fattening fish;

Birds darken the sky. Is it enough

That the dish of milk is set out at night,

That we think of him sometimes,

Sometimes and always, with mixed feelings?

~ John Ashbery

Who’s “traveling furiously toward you”? Who is it who wants you so madly? The suggested answer, the one according to all the critics, I hate to tell you, is not Love but the Angel of Death — or, if we drop “Angel” with all the beauty usually attributed to angels, then it’s death itself. The D word, normally avoided and called by euphemisms such as “passing.”

But is it really the Big D? Surely “he” would know where to find you and how to recognize you. So perhaps it’s the “imperial messenger” from Kafka, traveling from the capital and the dying emperor to deliver a message to you, a unique and supremely important message that somehow, as always in Kafka, keeps coming but never arrives. Still, we think of it “sometimes and always” — and with mixed feelings.

But let me go against the truism that all poems are about mortality, and suggest that the furious rider it is NOT the Big D. I suspect that what is at work is a half-conscious association of

Somewhere someone is traveling furiously toward you,

At incredible speed, traveling day and night,

Through blizzards and desert heat, across torrents, through narrow passes

with a typical romantic plot of a lover speeding toward the beloved. It’s the archetype of true love overcoming all obstacles, blizzards and desert heat and so on. (For those who know the famous Russian song: Yedet’, yedet’, yedet’ k’ney, yedet’ k’dyevushkye svoyey — he’s riding, riding, riding to her, riding to his beloved.) And what do we want most? To be loved, deeply loved — to be the great love of the one who’s our great love.)

Jung said that a writer who uses archetypes speaks with a thousand mouths. And what archetype do we have here? That of a man in love, traveling as fast as he can to the woman he loves.

He doesn’t stop to eat or sleep. That’s the energy of love. In a way, that’s what we MUST believe if we are to carry on with all the idiotic chores of living. We must believe that someone somewhere cares enough about us that if called, he’d drop everything and travel toward us at full speed.

Once it was mother on whom we could count like that. Later it’s the romantic partner, the life partner. Or, if we aren’t so lucky, an imaginary lover. But we have to have someone we can imagine riding furiously toward us, through blizzards and narrow passes.

**

Of course that’s just the first three lines. We now have the difficult task of making sense of the rest of the poem.

The second stanza presents images of agricultural abundance, or even excess — even though “hardly anything grows here.” Is something biblical going on here, some mythologizing of a piece of desert as the land of plenty, of milk and honey (since “the streams run with sweetness”)? Don’t ask. Take it in but don’t try to make everything fit.

The milk set out at night invokes the folk custom of leaving an offering to the fairies (or goblins, or “little red people” in Polish folklore) — guardians of the house who perform all kinds of useful tasks while we sleep. Rilke mentions leaving milk to the spirits of the dead. Regardless, it’s meant as a duty — or at least a courtesy toward the unseen world.

Or maybe the poem isn’t meant to be coherent, but to evoke certain emotions and give certain pleasure nevertheless, especially in the first stanza. Ashbery does make use of an archetype, even if he subverts it with uncertainty

But will he know where to find you,

Recognize you when he sees you,

Give you the thing he has for you?

~ and then shifting into an assertion of barrenness, and ending on “mixed feelings.” Thus, the romantic archetype is subverted, but its presence in the first three lines has already worked its magic. We are enchanted by the image of someone traveling furiously toward us, bringing a gift. Our secret great longing is to be the beloved.

As Ray Carver put it

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

~ “Late Fragment”

We must imagine Sisyphus as happy not only because he’s striving toward a goal, but because he knows what it’s like to be beloved.

Barn and clouds, Minor Martin White, 1955

Barn and clouds, Minor Martin White, 1955

**

“What Is Love? I have met in the streets a very poor young man who was in love. His hat was old, his coat worn, the water passed through his shoes and the stars through his soul.” ~ Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

DALI’S TAROT: THE FOOL

“~ There are two motifs which Dali used throughout the deck: the butterfly and the linear figures. Both motifs can be seen in The Fool, shown above. On the left is the figurative image of a person raising a staff above the Fool's head. The staff reflects the shape of Hebrew letter Shin. The figure is also painted in red which may represent the element associated with this Hebrew letter: Fire. A blue butterfly can be seen over the belly of the rider, and a pattern of butterfly wings can be seen in the blanket which covers the horse. "The intellectual plane is symbolized by butterflies, expressive of irrationality and the alienated soul, the consequence of fickleness and disorder." The Fool himself is not identified, but appears to be a depiction of either a saint or Don Quixote. The "prophetic meaning" given for this card is the expiation of disorder.” ~ Rachel Pollack

“~ There are two motifs which Dali used throughout the deck: the butterfly and the linear figures. Both motifs can be seen in The Fool, shown above. On the left is the figurative image of a person raising a staff above the Fool's head. The staff reflects the shape of Hebrew letter Shin. The figure is also painted in red which may represent the element associated with this Hebrew letter: Fire. A blue butterfly can be seen over the belly of the rider, and a pattern of butterfly wings can be seen in the blanket which covers the horse. "The intellectual plane is symbolized by butterflies, expressive of irrationality and the alienated soul, the consequence of fickleness and disorder." The Fool himself is not identified, but appears to be a depiction of either a saint or Don Quixote. The "prophetic meaning" given for this card is the expiation of disorder.” ~ Rachel Pollack

*

THE PAST IS NEVER COMPLETE

“The past is not static, or ever truly complete; as we age we see from new positions, shifting angles. A therapist friend of mine likes to use the metaphor of the kind of spiral stair that winds up inside a lighthouse. As one moves up that stair, the core at the center doesn't change, but one continually sees it from another vantage point; if the past is a core of who we are, then our movement in time always brings us into a new relation to that core.” ~ Mark Doty

Oriana:

Core? What core? Basically I can't quite believe that my past was what it seems to have been. It's not “in character.” So much was sheer accident and desperation, way too stormy for the quiet life I always wanted. And if I didn't have my poems as testimony, I might just refuse to believe certain things happened because they don't fit my values, my intelligence, etc.

But then -- considering my parents and WWII -- who am I to complain that my circumstances didn’t fit my personality . . .

My two best friends also report being completely astonished by what their lives have been. We like to joke that if at twenty a psychic accurately foretold us what lay ahead, we would have laughed our heads off (or maybe run out of the room screaming). Who knows, maybe it’s true for a great number of people . . . whose lives may seem staid, and yet, for all we know, might have contained all kinds of storms and catastrophes.

And, as Faulkner famously observed, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

And as Sartre said, and Mark Doty confirms, the present changes the past. So there's always hope for the past.

BORGES: THE PASSING OF THE PAST

“Events that fill up space and reach their end when someone dies may cause us wonder, but some thing—or an endless number of things—dies with each man’s last breath, unless, as theosophy conjectures, the world has a memory. In the past, there was a day when the last eyes to have seen Christ were closed; the battle of Junín and Helen’s face each died with the death of some one man.

What will die with me when I die, what pathetic or worthless memory will be lost to the world? The voice of Macedonio Fernández, the image of a brown horse grazing in an empty lot at the comer of Serrano and Charcas, a stick of sulphur in the drawer of a mahogany desk?”

~ Borges, “The Witness”

It’s somewhat odd that a famous writer would be asking this, since presumably his most significant (or colorful — I love that brown horse grazing in an empty lot) memories are preserved — be it in a changed form — in his writing. Not that this work will live forever — Homer, Dante, Shakespeare are great exceptions.

But should be really worry about being forgotten, or some precious (or pathetic and worthless — but it’s never worthless if it’s ours) memory being lost to the world when our personal memory ceases? I think for most of us the point is not any kind of “legacy,” or where we stand with the world as witnesses to history. The point is rather to take a little time to ponder which memories first come to mind — right now, in this mood and moment,

at this stage of life.

It may be very important to Borges to be symbolically "holding hands" with the ancient statue, a symbol of cultural continuity. But we also know that the statue, which might stand here for the "world's memory," doesn't know or care. Yet that's too harsh: what counts is the collective cultural memory of humanity, and Borges was eminent enough, both unique and universal enough, to have added a crumb of richness to that cultural memory.

It may be very important to Borges to be symbolically "holding hands" with the ancient statue, a symbol of cultural continuity. But we also know that the statue, which might stand here for the "world's memory," doesn't know or care. Yet that's too harsh: what counts is the collective cultural memory of humanity, and Borges was eminent enough, both unique and universal enough, to have added a crumb of richness to that cultural memory.

Another image of Borges in Palermo, 1984 — he’s completely blind at this point.

Another image of Borges in Palermo, 1984 — he’s completely blind at this point.

**

Portland Police Bureau: Forensic Evidence Division Criminalist Walker Berg took this amazing photo from the 12th floor of the Justice Center. We're calling it “Crows on Snow.”

**

**

~ “Futterneid = Food-Envy

The feeling when you’re eating with other people and realize that they’ve ordered something better off the menu that you’d be dying to eat yourself. Perhaps you were trying to be abstemious; now you’re just in agony. The word recognizes that we spend most of our lives feeling we’ve ordered the wrong thing. And not just in restaurants.” ~

I have to admit that I often suffer from Futterneid . . . By the way, “Futter” is a coarse word, more like “feed” for animal (“fodder” sounds like a cognate in English). In any case, looking at the marvelous dishes that others have ordered reveals to us that we just don’t love ourselves enough. On the other hand, we may also be deluding ourselves about all those other dishes — they are not always better than what we ordered. After all, who knows how many others are looking at our plate (not just the literal plate at a restaurant) and thinking they blew it, and should be having what we are having . . .

Heck, I can’t even go to a taco truck without lusting after what others are having.

Osias Beert (1580-1624): Still Life with Oysters. That insect (I hope it’s just a fly, not a cockroach) on the bread totally takes away your appetite, doesn’t it? The elegance of the glassware, the luxury of oysters — all annihilated by an insect.

Osias Beert (1580-1624): Still Life with Oysters. That insect (I hope it’s just a fly, not a cockroach) on the bread totally takes away your appetite, doesn’t it? The elegance of the glassware, the luxury of oysters — all annihilated by an insect.

THE ANSWER LIES OUTSIDE (OUTWARD FOCUS)

I was reading the summary of Abraham Maslow’s work over the morning coffee, and this item in the description of self-actualizing people suddenly blazed:

~ “Problem-centeredness (focus on questions or challenges outside themselves — a sense of mission or purpose — resulting in an absence of pettiness, introspection, and ego games)” ~

There is was: “the answer lies outside.” It was one of my crucial discoveries when I analyzed my success ending depression. We are constantly bombarded with “The answer lies within.” I an early blog I dared to propose that “the answer lies without.”

That’s it — having a purpose in life automatically resolves a myriad other problems. When a larger meaning is born, those problems become irrelevant — they are transcended instantly.

I re-read the statement about self-actualizers, simplifying it:

~ Problem-centeredness — focus on questions or challenges outside themselves — a sense of mission or purpose — resulting in an absence of introspection. ~

Yet the therapeutic tradition favors self-centered analysis of one’s childhood and rarely addresses the sense of purpose in life — Viktor Frankl’s “Search for Meaning” is the one exception that springs to mind.

I wish I could find that early blog, but I’d have to comb through a dozen. A quick search yielded this (the writing is my own):

“Be a gazer at the world, not an obsessive gazer within.” I owe this motto to Larry Levis, who pointed out that bad advice was often given to beginning poets, to the effect that the source of poems is introspection. Look at the world, Levis insisted. Not that introspection is forbidden, but that looking at the world is likely to result in richer poems. Likewise, bringing other people into a poem will often enlarge and improve the poem.

Introverts do not need to be told to “look within.” They do that on automatic. The harder part is learning to look at the world. As with so many “good for you” things, it’s a matter of establishing a new habit.

**

Training myself to "gaze at the world" rather than listen to my thoughts — even just daydream while driving instead of really seeing the road, the trees, the sky — was one of the best things I've done in my life. I didn't really try to suppress thoughts about, for instance, a bad relationship I had in my twenties; those thoughts simply didn't occur when I looked with true interest at trees, buildings, people's faces — anything “out there.”

The brain has the so-called default mode network: when we are not focused on a task we begin to daydream and experience drifting thoughts. When the default network becomes highly active and excessively connected, the result can be depression or another mental disorder. Cognitive training involving intense focus on something external acts as a corrective. The brain can rewire to pay attention to the right things.

I keep pondering the wisdom of the statement I heard a long time ago at a science conference: all mental disorders stem from paying attention to the wrong things.

**

Someone familiar with my early writing about conquering depression could easily object to the foregoing: “Wait a moment! Your life-changing insight wasn’t: here is my newfound purpose.”

That true. My insight was: “It’s too late in life to be depressed.” The first step was to realize that I didn’t want to waste what little time remained on idiotic brooding about all the catastrophes of the past.

Then things followed on automatic, i.e. on the unconscious level without conscious clarity. I am now trying to recreate the process on the crude, conscious level — to present a sequence where the process was by no means Step 1, Step 2, etc. But let me try anyway:

Step One was deciding it was too late to be depressed (I also call this “being cornered by mortality” — it’s enough to ask oneself, “How many good years do I still have”?) This led to Step 2: diving into productivity to replace brooding. In my case, productivity meant writing.

I instantly knew — don’t ask — that the new writing could not be introspective. Instead, I could write book reviews and movie reviews. I could search out and analyze poems for the Poetry Salon. I could surf health news and find something at least mildly provocative, e.g. Alzheimer’s is auto-immune. This kind of writing may not sound like a great purpose in life, but it was a modest being of service. At least I wasn’t spending my days brooding and loathing myself.

Perhaps purpose “purpose in life” is too grand a phrase to start with. The healing lay in external focus. And in prose, since prose is more like sketching — a craft. A painter doesn’t need inspiration to start sketching. A poet and writer can always write some good-enough prose — a book review, for instance, especially if she’s done scores of those.

Step 3 was simply a refinement of Step 2, productivity = writing. I got better at the blog-type writing, and could even start thinking in terms of purpose. I wanted to nourish my readers in a certain way. “Ending on beauty” became very important. Striking images became more important. I stepped up to being unapologetically intellectual in an anti-intellectual culture, and more radical and outspoken.

At the beginning I had strict “no-thinking zones.” I simply didn’t allow myself any conscious thinking on certain subjects, knowing that a tide of immense sadness might turn into a tsunami. As I grew emotionally stronger, I didn’t have to be on guard against introspection quite as much. Even so, I realized that my insights about my life, my own past included, usually came on their own when the time was ripe. Generally they were not the product of introspection.

I am presenting this strictly as my own process, not as a universal prescription. I was very lucky to have already developed the skills that would serve working with an external focus. Others have reported success throwing themselves into work of a different sort, e.g. volunteer services, animal rescue, or devoting themselves to music. It’s still external focus as I see it — just the details differ.

“Works works” — especially the kind of work you love doing, so love and work are combined.

Time spent with cats is never wasted ~ Sigmund Freud (allegedly)

Time spent with cats is never wasted ~ Sigmund Freud (allegedly)

PUTIN’S AND TRUMP’S WAR ON MODERNITY IN THE NAME OF PAST “GREATNESS” AND “TRADITIONAL VALUES” VERSUS HUMAN RIGHTS