EYEGLASSES

Before my grandparents left Auschwitz,

they went to the mountain of eyeglasses,

thinking that by a miracle

they might find their own.

But it was hopeless to sift

through thousands of tangled pairs.

They tried one pair after another.

They had nothing to read, so they traced

the wrinkles on their hands.

They’d bring the hand up close,

follow the orbits of knuckles,

the map of fate in the palm.

if one eye saw right,

the other was blurred.

Haze stammered the line of life.

They took several pairs.

My mother is embarrassed

telling me the story,

embarrassed her parents

took anything at all

from the piles of looted belongings.

But I would have been like them.

Those stripped to nothing end up

with too much, except nothing fits

after reading your hands

through the glasses of the dead –

This is how beauty looks

through those eyeglasses:

blurred, skeletal,

a man and a woman

help each other up,

lean on a handcart, walk on.

~ Oriana*

My grandparents didn’t end up in Auschwitz because they were Jewish (although genetically, but not culturally, my grandmother could be called Jewish). It was a retaliation for the Warsaw Uprising. The Nazis took all the inhabitants of a certain district of Warsaw and put them in trains to Auschwitz. It was just a matter of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

My grandparents were classified as Catholic Poles, which meant they would be slowly starved to death rather than automatically sent to the gas.

My mother took part in the Uprising and was in another transport, but the members of the Resistance bribed the German guards and she was let out in Krakow. That’s mentioned in the poem “My Mother Is Prepared.”

**

This reminds me of something related. The Polish Resistance (commonly known as the AK, usually translated as the Home Army), was well informed about what was happening in Auschwitz. My Uncle Zygmunt was the commander of the Southwestern section, which kept a close watch on Auschwitz, especially toward the end of 1944, because of the possibility that the Nazi might decide to massacre all the inmates. The AK’s response to that would be attack the camp and try to liberate the prisoners. This was the “worst-case-only” scenario, since the casualties, including those among the inmates, would be very high (the Germans were unfortunately very well armed and hard to fight).

Instead of a massacre, the SS chose to lead the inmates out on a death march to the German camps, allowing the old and the sick to remain on the grounds of Auschwitz. My grandparents decided to stay, which turned out to be their salvation.

My grandmother Veronika remembered with pleasure January 27, 1945. A Russian soldier rushed into her barracks, shouting Svoboda! — Freedom. Minutes later, a Polish soldier (some Poles fought alongside the Red Army) rushed in, shouting the word Freedom in Polish. Another memory she loved was how the Russian cook set up a big kettle to boil potatoes. After peeling a potato, he’d toss it over his shoulder into the kettle. My grandmother and a few other women would crouch in the back and catch some of those potatoes. I know this seems like a scene from a slapstick comedy, but there it was — humor and horror.

The horror of the camps is of course almost beyond comprehension. My grandmother had recurrent nightmares for the rest of her life, moaning loud enough to wake me up. I don’t mean night after night — only now and then. But that — and more — gave me some understanding of the horror. Imagine my shock, later, when I first encountered Holocaust denial (my definition of Holocaust extends to all the atrocities, not strictly confined to the Jewish population).

*

WHY TOLSTOY HATED SHAKESPEARE

~ Though William Shakespeare is beloved by many, appreciation for his work is not universal, and there are several equally famous writers who have resisted his reign as the greatest dramatist of all time. After spending three short years as a theater critic, George Bernard Shaw felt compelled to open our eyes to the “emptiness of Shakespeare’s philosophy.” As a scholar of English literature, J.R.R. Tolkien was known and feared for his disdain of the bard, and Voltaire couldn’t talk about him without his blood starting to boil. However, no giant of literature despised Shakespeare quite as much as Leo Tolstoy.

Born in an aristocratic family, the author of War and Peace was exposed to Hamlet and Macbeth from an early age, and he grew annoyed when he turned out to be the only one among his friends and family members who did not see them as true masterpieces. Shakespeare’s jokes struck him as “mirthless.” His puns, “unamusing.” The only character that actually owned their pompous dialogue was the drunken Falstaff.

When Tolstoy asked Ivan Turgenev and Afanasy Fet — two writers whom he admired and respected — to tell him just what made the bard so great, he found that they were only able to respond in vague terms, without the precision of language or the profound level of analysis they had frequently demonstrated in their fictions. Tolstoy figured he might come to appreciate Shakespeare in old age, but when — upon his nth re-read at age 75 — he still found himself untouched, he decided to work his criticisms out on paper.

Though not without its flaws and biases, the 1906 essay that resulted from this endeavor is an emphatic attack on Shakespeare’s legacy and the institutions that helped build it. First, Tolstoy questioned the bard’s ability as a playwright. His characters were placed in unbelievable circumstances like biblical killing sprees and sitcom-esque identity swaps, making it difficult for audiences to relate to them. They also often acted out of character, following not the mandates of their personality but the schedule of the plot.

Common for Russian writers of the time, Tolstoy tried to give every character in his fiction a distinct voice, one that varied depending on their age, gender, or class. Princesses spoke delicately and had rich vocabularies, while drunken peasants slurred and mumbled. With Shakespeare, who always wrote in the same poetic style, “the words of one of the personages might be placed in the mouth of another, and by the character of the speech it would be impossible to distinguish who is talking.”

Tolstoy became interested in Shakespeare not because he wanted to understand his own dislike of the man, but because he was surprised by and suspicious of the readiness with which other people rushed to his aid. “When I endeavored to get from Shakespeare’s worshipers an explanation of his greatness,” Tolstoy wrote, “I met in them exactly the same attitude which I have met, and which is usually met, in the defenders of any dogmas accepted not through reason but through faith.”

In the second half of the essay, Tolstoy speculates about how this religion around Shakespeare may have come about. Tracing the history of scholarly writing on his plays back to the late 16th century, he concluded that the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had played a key role in elevating the work of Shakespeare from the bawdy kind of lower-class entertainment it was seen as during the bard’s own time, to the work of sensitive and inexhaustive literary genius we know today.

Disillusioned by the French dramas that had once inspired them, German intellectuals settled on Shakespeare, whose emphasis on emotions over thoughts and ideas made him a suitable bedrock upon which to build their new school of romantic storytelling. It was a school that Tolstoy, who believed art should not just be aesthetically pleasing but serve a social purpose, did not think highly of. In fact, he accuses them of having “invented aesthetic theories” in an attempt to turn their opinions into facts.

Shakespeare, having died a few centuries before Tolstoy’s birth, was unable to respond to the latter’s accusations. Fortunately, his compatriot — the British writer George Orwell — wrote Tolstoy a reply in the bard’s defense, one that offers an equally compelling argument for why we should read Shakespeare. Before he does so, though, Orwell exposes the holes in Tolstoy’s reasoning, starting with the notion that deciding whether an artist was good or bad is simply impossible.

It is an argument that we have heard many times over, but one worth hearing again if only for its especially relevant conclusion. Just as Tolstoy’s own ideas about art were different if not outright opposed to those of the German romantics he denounced, so too were the ideas of the writers that followed in his footsteps. “Ultimately,” Orwell wrote in his essay, “Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool“ (1947), “there is no test of literary merit except survival, which is itself an index to majority opinion.”

Orwell did not think it fair of Tolstoy to chastise his compatriots for their inability to assess Shakespeare’s genius when his own conceptions of literature — that it had to be “sincere” and try to do something “important for mankind” — were just as ambiguous. Orwell also takes issue with the summaries that Tolstoy gives of Shakespeare’s plays, paraphrasing the heartfelt speech King Lear makes after Cordelia dies as: “Again begin Lear’s awful ravings, at which one feels ashamed, as at unsuccessful jokes.”

Most egregiously, thought Orwell, was that Tolstoy judged Shakespeare by the principles of a prose writer instead of what he was: a poet. Considering that most people appreciate Shakespeare not for his story structures or characterizations but his sheer use of language — the powerful speeches from Julius Caesar, the clever wordplay in Gentlemen of Verona, and the striking metaphors exchanged between the lovers Romeo and Juliet – this is quite the oversight on Tolstoy’s part.

At the end of the day, Orwell likes to imagine Shakespeare as a little kid happily playing about and Tolstoy as a grumpy old man sitting in the corner of the room yelling, “Why do you keep jumping up and down like that? Why can’t you sit still like I do?” This may sound silly, but those who studied Tolstoy’s life — and are familiar with his controlling impulse and serious nature — will find themselves thinking of other critics who have made similar statements.

While all of Shakespeare’s characters may talk in that familiar, flowery, Shakespearean manner, each of his plays still feels unique and completely distinct from the one that came before it. In his essay, The Fox and the Hedgehog, the German-born, British philosopher Isaiah Berlin favorably compared the childlike curiosity with which Shakespeare hopped from one genre to another with the single-minded and unchanging way in which Tolstoy’s fiction explored the world.

In a similar vein, the Bolshevik playwright Anatoly Lunacharsky once called Shakespeare “polyphonic to the extreme,” referencing a term invented by his contemporary Mikhail Bakhtin [to describe the work of Dostoyevsky). Put simply, Lunacharsky was amazed by Shakespeare’s ability to create characters that seemed to take on lives of their own, existing independently from their creator. This was in stark contrast to Tolstoy, who treated every character as an extension or reflection of himself and used them as mouthpieces for his own beliefs.

The conflict between Leo Tolstoy and William Shakespeare was about more than taste; it was a clash between two different ways of looking at life and art. Orwell brought this discussion into focus. Perhaps his greatest contribution to it, though, was pointing out the similarities between Tolstoy and the Shakespearean creation he hated most: King Lear. Both old men renounced their titles, estates, and family members thinking it would make them happy. Instead, they ended up roaming the countryside like madmen. ~

https://bigthink.com/high-culture/tolstoy-shakespeare/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR1FKJAmsZpsz6hiezHYIoldPke8BFIz_ebuf-7rOD_e2vbg6wtiOfupqkI#Echobox=1642088029-1

Oriana:

In my teens, I too had no idea why Shakespeare was called a genius — until I was able to read him in English. Then he didn’t disappoint, to put it mildly. Then, in his best plays, he showed himself to be an enchanter.

As for Shakespeare’s humor not being especially funny to us, the answer seems to be that humor dates quickly. What was funny centuries ago may become at best mildly amusing. Not that Shakespeare’s “comedies” such as Midsummer’s Night Dream are not worth reading. They are immortal classics, but not because they are funny. Again, it’s the language and the imagination that make them worth reading and performing.

As far as the plots of the plays go, they were all derived from earlier sources. I still don’t care for them, whether it’s revenge or family feuds. The play that set me on fire when I was in high school was Antigone — not the escalating murders of Macbeth or what seemed to me a ridiculously hasty marriage of Romeo and Juliet. Now I see the plot as mere scaffolding for the masterful speeches. The same way, we don’t go to the opera for the sake of the plot — it’s about the singing. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow . . .

Mary:

I have a vivid memory of the scene with Lady Macbeth pacing and rinsing her hands. It was the Hallmark television Theater production of Macbeth, aired in black and white in 1954. I was 4 years old, and that left an indelible impression. I was watching, of course, with my mother, sitting on the dining room table across from the small black and white TV. Later, in 1959, we saw the Hallmark production of The Tempest, with Richard Burton and Roddy Macdowall...images and characters I never forgot.

Yes, Shakespeare used old stories, but those old stories are old because they speak to something basic in human experience, in the same way folk and fairy tales do. And I can’t see saying his characters are not fully distinct individuals. No one could confuse Juliet with Cleopatra, or Goneril with Miranda. Lear, Macbeth, Prospero, Othello are all rich and full individuals even when they are also archetypes. Each is distinct and unforgettable.

But of course the wonder of Shakespeare is the glory of his language. So rich, so inventive, such glorious poetry, inexhaustible . And always, in every play, in each character's lines, what is most unavoidably evident is the joy Shakespeare finds in language itself, its rhythms and invention, the play of words and all their powers..to create, amuse, convince, entertain, discover and pursue truth, reveal character, conceal motive, cast a spell on all who hear them. He is a magician with language.

I think Tolstoy takes himself much too seriously, especially in his demand that art serve some social purpose. It leads him, I think, in his masterpiece, War and Peace, to the burden of all those analytic and didactic chapters on the nature of change in history. He doesn't trust his art alone to examine and demonstrate these complexities. If he did he would allow the story and characters themselves to embody and illustrate these themes and ideas..and they do, despite the constant interruptions of the didactic chapters. Listen to Pierre, watch him observe and learn. Follow the path of the armies and their soldiers. Watch Natasha, trying to grow up.

This may all be apostasy but I think it is proved by his other masterwork Anna Karenina. I find Anna to be a close to perfect novel. Tolstoy trusts her and her story enough to give it without interruption, and as Anna's fate plays out among the expectations and restrictions of society we have a solid, growing sense of her own tragedy, the narrowing and narrowing of possibilities, the reduction in all her choices and all the relationships and connections in her life...Anna comes to her last inevitable act with the same convincing gravitas as Oedipus. No other end is possible, and has not been possible since the very first steps in these characters' stories. They can neither win nor be forgiven. There is no way out or around their fate.

Oriana:

I totally agree with you about the greatness of Anna Karenina as a novel. It’s appallingly realistic, showing us the fading and ultimate death of romantic love — and it’s still a heresy to admit that romantic love doesn’t last, no exception. It may become transformed into a kind of friendship-love, a deep attachment to someone without the need to idealize the person. But more typically romantic love simply ends, sooner for one partner than the other, a fact that can cause dreadful suffering.

And it’s somewhat disturbing to realize that people love a dog or a cat in a much more reliable manner. And that love, especially for a dog, can be so intense that the pet’s death is a genuine trauma. Pet cemetery? I saw one in Torrance (I used to live in Torrance — part of the LA basin), and the outpouring of love for the dead pets went far beyond what you see in human cemeteries. Is it because dogs never criticize us? Or that a dog can give you a more soulful look than a human can . . . And that total trust . . .

MACBETH (THE MOVIE): ALL ABOUT STYLE

from the New York Times:

~ The poet John Berryman wrote of “Macbeth” that “no other Shakespearean tragedy is so desolate, and this desolation is conveyed to us through the fantastic imagination of its hero.” The universe of the play — a haunted, violent patch of ground called Scotland — is as dark and scary as any place in literature or horror movies. This has less to do with the resident witches than with a wholesale inversion of moral order. “Fair is foul and foul is fair.” Trust is an invitation to treachery. Love can be a criminal pact or a motive for revenge. Power is untempered by mercy.

Macbeth himself, a nobleman who takes the Scottish throne after murdering the king he had bravely served, embodies this nihilism as he is destroyed by it. The evil he does — ordering the slaughter of innocents and the death of his closest comrade — is horrific even by the standard of Shakespeare’s tragedies. And yet, Berryman marvels, “he does not lose the audience’s or reader’s sympathy.” As Macbeth’s crimes escalate, his suffering increases and that fantastic imagination grows ever more complex and inventive. His inevitable death promises punishment for his transgressions and relief from his torment. It also can leave the audience feeling strangely bereft.

The director Joel Coen’s crackling, dagger-sharp screen adaptation of the play — called by its full title, “The Tragedy of Macbeth” — conjures a landscape of appropriate desolation, a world of deep shadows and stark negative space. People wander in empty stone corridors or across blasted heaths, surveyed at crooked angles or from above to emphasize their alienation from one another. The strings of Carter Burwell’s score sometimes sound like birds of prey, and literal crows disrupt the somber, boxy frames with bursts of nightmarish cacophony.

For filmmakers, Shakespeare can be both a challenge and a crutch. If the images upstage the words, you’ve failed. But building a cinematic space in which the language can breathe — in which both the archaic strangeness and the timelessness of the poetry come to life — demands a measure of audacity. Coen’s black-and-white compositions (the cinematographer is Bruno Delbonnel) and stark, angular sets (the production designer is Stefan Dechant) gesture toward Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier, two of the 20th century’s great cinematic Shakespeareans. The effect is to emphasize the essential unreality of a play that has always been, in its own words, weird.

As many critics have noted, it is at the same time unnervingly acute in its grasp of human psychology. “Macbeth” is therefore a quintessential actor’s play, even if actors are famously superstitious about uttering its name. And Coen’s version is, above all, a triumph of casting.

By which I mean: Denzel Washington. Not only him, by any means: the ensemble of thanes and wives, hired killers and servants, witches and children is pretty much flawless. Kathryn Hunter is downright otherworldly as all three of the shape-shifting, soothsaying weird sisters. Stephen Root, in a single scene as Porter, lifts the grim, forensic business of regicide and its aftermath into the realm of knockabout farce. Alex Hassell plays Ross as a perfect paragon of courtly cynicism, always obliging and never to be trusted. Bertie Carvel’s Banquo and Corey Hawkins’s Macduff carry the burden of human decency with appropriate feeling.

I could go on — every scene is a mini-master class in the craft of acting — but “The Tragedy of Macbeth” is effectively the portrait of a power-mad power couple. The madness manifests itself in different ways. Frances McDormand’s Lady Macbeth is sometimes reduced to a caricature of female villainy: ambitious, conniving, skilled at the manipulation of her hesitating husband. McDormand grasps the Machiavellian root of the character’s motivation, and the cold pragmatism with which she pursues it. But her Lady Macbeth is also passionate, not only about the crown of Scotland, but about the man who will wear it. Her singular and overwhelming devotion is to him.

The Macbeths may be ruthless political schemers, but there is a tenderness between them that is disarming, and that makes them more vivid, more interesting, than the more cautious and diligent politicians who surround them. Which brings me back to Washington, whose trajectory from weary, diffident soldier to raving, self-immolating maniac is astonishing to behold.

Whereas Lady Macbeth has drawn up the moral accounts in advance — rationalizing the murder of Duncan (Brendan Gleeson) even though she knows it can’t be justified — her husband perceives the enormity of the crime only after the fact. Macbeth’s guilt is part of what propels him toward more killing (“blood will have blood”) and Washington somehow entwines his escalating bloodthirstiness with despair. The man is at once energized by violence and terrified of his appetite for it.

Washington’s voice is, as ever, a marvel. He seethes, raves, mumbles and babbles, summoning thunderstorms of eloquence from intimate whispers. The physicality of his performance is equally impressive, from his first appearance, trudging heavily through the fog, until his final burst of furious, doomed mayhem.

“The fantastic imagination of the hero” is what reveals the profound desolation of “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” but also what redeems the play from absolute bleakness. There is no comfort in Coen’s vision, but his rigor — and Washington’s vigor — are never less than exhilarating.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/22/movies/the-tragedy-of-macbeth-review-denzel-washington.html

MACBETH AS A FILM NOIR

~ “The Tragedy of Macbeth” visually leans into a noirish interpretation. It’s shot in silvery, at times gothic black and white by Bruno Delbonnel, has a moody score by the great Carter Burwell, and takes place on incredible (and obviously fake) sets designed by Stefan Dechant. It also has more fog than San Francisco, the setting for so many great noirs.

This [movie] also features McDormand as a shady lady, namely Lady Macbeth. She’s married to Washington’s Macbeth, the Thane of Glamis. As the casting indicates, this couple is older than the one the Bard envisioned, which changes one’s perception of their motivations. Youthful ambition has given way to something else; perhaps the couple is way too conscious of all those yesterdays that “lighted fools/The way to dusty death.” At the Q&A after the free IMAX screening of this film, McDormand mentioned that she wanted to portray the Macbeths as a couple who chose not to have children early on, and were fine with the choice. This detail makes the murder of Macduff’s (Corey Hawkins) son all the more heartless and brutal, an act Coen treats with restraint but does not shy away from depicting.

Since The Scottish Play was first performed 415 years ago, all spoiler warnings have expired. Besides, you should know the plot already. Banquo (Bertie Carvel) and the Thane of Glamis meet three witches (all played by theater vet Kathryn Hunter) on his way back from battle. They prophesy that Macbeth will eventually be King of Scotland. But first, he’ll become the Thane of Cawdor. When that part of the prediction becomes true, Macbeth thinks these medieval Miss Cleos might be onto something. Though he believes chance will crown him without his stir, Lady Macbeth goads him to intervene. As is typical of Shakespeare’s tragedies, the stage will be littered with dead bodies by the final curtain, each of whom will have screamed out “I am slain!” or “I am dead!” before expiring. Coen leaves that feature out of the movie, as you can see quite graphically how dead the bodies get on the screen.

King Duncan’s murder is especially rough. Washington and Brendan Gleeson play it as a macabre dance, framed so tightly that we feel the intimacy of how close one must be to stab another. It’s almost sexual. Both actors give off a regal air in their other scenes, though Washington’s is buoyed by that patented Den-ZELLL swagger. He even does the Denzel vocal tic, that “huh” he’s famous for, in some of his speeches, making me giddy enough to jump out of my skin with joy. Gleeson brings the Old Vic to his brief performance; every line and every moment feels like he’s communing with the ghosts of the famous actors who graced that hallowed London stage.

The other actors are well cast and bring their own gifts to their work. Stephen Root almost walks off with the picture as Porter. Alex Hassel gets more to do as Ross than I remembered. And there’s a great scene with an old man played by an actor I will not reveal. (Look real closely when he appears.) As for McDormand, she has her usual steely reserve, but I don’t think she fully shakes that off once we get to that “out, damned spot” scene. I had a similar problem with Washington’s scene at the banquet when he is haunted by a familiar specter. Both seem too confident to be in the thrall of temporary madness.

This “Macbeth” is as much about mood as it is about verse. The visuals acknowledge this, pulling us into the action as if we were seeing it on stage. But nowhere is the evocation of mood more prominent than in Kathryn Hunter’s revelatory performance as the Witches. There’s an otherworldliness to her appearance and her voice, as if she came from a dark place Macbeth should fear. You will have a hard time forgetting her work. She’s fantastic here, and Coen’s depiction of her cauldron bubbling is a highlight, as is the narrow staging of Macbeth’s final battle. Hawkins holds his own against the behemoth that is Denzel Washington, and their swordplay is swift and nasty.

One note of caution: High school students who use movies instead of reading the play will, as always, continue to fail English class. If chance would have you pass, then chance would pass you without your stir. So read the play, kids! ~

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-tragedy-of-macbeth-movie-review-2021

Oriana:

Although Shakespeare’s plays were certainly meant to be performed onstage, after 400 years they must, above all, be read — and with the help of good notes, too. Only then can we fully appreciate the genius of Shakespeare’s language — those immortal soliloquies.

No adaptation can truly render the macabre grandeur of Macbeth. It’s only a question of how close you can come to that nightmarish perfection. And of course each viewer will have a different perspective. Though critics rave about the idea of using one actress to portray all three witches, I personally missed the witches as a trinity. I think it was a mistake not to have three different actresses. That’s because they are also the parallel to The Three Fates.

They are called the Weird Sisters — Weird or Wyrd means “Fate.” And the notion of “fate” is important in this play. Early on, Macbeth thinks that if it’s his fate to become king, then that will happen without his trying to force fate’s hand. Fate is fate — it will unfold even against our will.

The movie sets are extremely stylized. The architecture of the castle is not based on the actual medieval Scottish castles, but on the paintings of De Chirico — the repeated arches, the emptiness.

The crows (or is it ravens?) probably aren’t meant to make us think of Hitchcock’s sinister Birds, but it’s an unavoidable association. Instead, we should strive to remember that crows and ravens were associated with death and the underworld, and were also seen as messengers from the underworld. But in this movie, it's simply their blackness. Stylistically, they belong. And these are the only birds we see. No lark sings at the heaven's gate in this movie. Fair is foul and foul is fair, but bleak is only bleak in this bleakest of all Macbeths.

*

MACBETH: GUILT KNOCKING ON THE GATE

“. . . when the deed is done, when the work of darkness is perfect, then the world of darkness passes away like a pageantry in the clouds: the knocking at the gate is heard, and it makes known audibly that the reaction has commenced; the human has made its reflux upon the fiendish; the pulses of life are beginning to beat again; and the re-establishment of the goings-on of the world in which we live first makes us profoundly sensible of the awful parenthesis that had suspended them.” ~ Thomas De Quincy, “On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth” — a brilliant essay on how the knocking re-establishes the human world in which a crime has consequences. It is indeed the turning point of the play: now we'll see the workings of guilt.

**

WHY WE FALL IN LOVE

~ Adrienne Rich, in contemplating how love refines our truths, wrote: “An honorable human relationship — that is, one in which two people have the right to use the word ‘love’ — is a process, delicate, violent, often terrifying to both persons involved, a process of refining the truths they can tell each other.” But among the dualities that lend love both its electricity and its exasperation — the interplay of thrill and terror, desire and disappointment, longing and anticipatory loss — is also the fact that our pathway to this mutually refining truth must pass through a necessary fiction: We fall in love not just with a person wholly external to us but with a fantasy of how that person can fill what is missing from our interior lives.

Psychoanalyst Adam Phillips addresses this central paradox with uncommon clarity and elegance in Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life.

Phillips writes:

All love stories are frustration stories… To fall in love is to be reminded of a frustration that you didn’t know you had (of one’s formative frustrations, and of one’s attempted self-cures for them); you wanted someone, you felt deprived of something, and then it seems to be there. And what is renewed in that experience is an intensity of frustration, and an intensity of satisfaction. It is as if, oddly, you were waiting for someone but you didn’t know who they were until they arrived. Whether or not you were aware that there was something missing in your life, you will be when you meet the person you want.

What psychoanalysis will add to this love story is that the person you fall in love with really is the man or woman of your dreams; that you have dreamed them up before you met them; not out of nothing — nothing comes of nothing — but out of prior experience, both real and wished for. You recognize them with such certainty because you already, in a certain sense, know them; and because you have quite literally been expecting them, you feel as though you have known them for ever, and yet, at the same time, they are quite foreign to you. They are familiar foreign bodies.

This duality of the familiar and the foreign is mirrored in the osmotic relationship between presence and absence, with which every infatuated lover is intimately acquainted — that parallel intensity of longing for our lover’s presence and anguishing in her absence. Phillips writes:

However much you have been wanting and hoping and dreaming of meeting the person of your dreams, it is only when you meet them that you will start missing them. It seems that the presence of an object is required to make its absence felt (or to make the absence of something felt). A kind of longing may have preceded their arrival, but you have to meet in order to feel the full force of your frustration in their absence.

Falling in love, finding your passion, are attempts to locate, to picture, to represent what you unconsciously feel frustrated about, and by.

Nowhere is the unlived life more evident than in how we think of loves that never were — “the one that got away” implies that the getting away was merely a product of probability and had the odds turned out differently, the person who “got away” would have been The One. But Phillips argues this is a larger problem that affects how we think about every aspect of our lives, perhaps most palpably when we peer back on the road not taken from the fixed vantage point of our present destination:

We are always haunted by the myth of our potential, of what we might have it in ourselves to be or do… We share our lives with the people we have failed to be.

Our lives become an elegy to needs unmet and desires sacrificed, to possibilities refused, to roads not taken. The myth of our potential can make of our lives a perpetual falling-short, a continual and continuing loss, a sustained and sometimes sustaining rage.

Missing Out is an unmissable read in its totality, exploring how the osmosis of frustration and satisfaction illuminates our romantic relationships, our experience of success and failure, and much more. It is a magnificent read in its totality. Complement this particular portion with Stendhal on the seven stages of romance, Susan Sontag on the messiness of love, and the great Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hahn on how to love, then revisit Phillips on balance, the essential capacity for “fertile solitude,” and how kindness became our guilty pleasure.

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/why-we-fall-in-love?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Chagall: Lovers, 1913

*

HOW HUMANITY CAME TO CONTEMPLATE ITS POSSIBLE EXTINCTION

~ With Covid-19 afflicting the world, and a climate crisis looming, humanity’s future seems uncertain. While the novel coronavirus does not itself pose a threat to the continuation of the species, it has undoubtedly stirred anxiety in many of us and has even sparked discussion about human extinction. Less and less does the end of the species seem an area of lurid fantasy or remote speculation.

Indeed, the opening decades of the 21st century have seen investigation into so-called ‘existential risks’ establish itself as a growing field of rigorous scientific inquiry. Whether designer pathogen or malicious AI, we now recognize many ways to die.

But when did people first start actually thinking about human extinction?

The answer is: surprisingly recently. As ideas go, the idea of the extinction of the human species is a new one. It did not, and could not, exist until a few centuries ago.

Of course, we humans have probably been prophesying the end of the world since we began talking and telling stories. However, the modern idea of human extinction distinguishes itself from the tradition of apocalypse as it is found across cultures and throughout history.

In the ancient mythologies you will not find the idea of a physical universe continuing, in its independent vastness, after the annihilation of humans. Neither will you find the idea of the end of the world as a totally meaningless event. It is invariably imbued with some moral significance or revelatory lesson. Meaning and value lives on in a spiritual afterlife, in anthropomorphic gods, or an eventual rebirth of creation.

Only very recently in human history did people realize that Homo sapiens, and everything it finds meaningful, might permanently disappear. Only recently did people realize the physical universe could continue — aimlessly — without us.

However, this was one of the most important discoveries humans have ever made. It is perhaps one of our crowning achievements. Why? Because we can only become truly responsible for ourselves when we fully realize what is at stake. And, in realizing that the entire fate of human value within the physical universe may rest upon us, we could finally begin to face up to what is at stake in our actions and decisions upon this planet. This is a discovery that humanity is still learning the lessons of — no matter how fallibly and falteringly.

Such a momentous understanding only came after centuries of laborious inquiry within science and philosophy. The timeline below revisits some of the most important milestones in this great, and ongoing, drama.

[BP = “Before Present”]

c.75,000 BP: Toba supervolcanic eruption rocks the planet. Some evidence implies Homo sapiens nearly goes extinct (though scientists disagree on the details). Around the same time, advanced human behavior and language emerge: This kickstarts cumulative culture, as recipes for technology begin to accumulate across generations. An immense journey begins…

PHASE 1 (PREHISTORY–1600): INDESTRUCTIBLE VALUE

No clear distinction between ethics and physics, so no true threat to the existence of ethics in the physical universe. Indestructibility of value. No ability to think of a possible world without minds.

c.400 BC: Even though they talk of great catastrophes and destroyed worlds, ancient philosophers all believe that nature does not leave eternally wasted opportunities where things, or values, could be but never are again. Whatever is lost in nature will eventually return in time — indestructibility of species, humanity, and value.

c.360 BC: Plato speaks of cataclysms wiping away prior humanities, but this is only part of eternal cycling return. Permanent extinction is unthinkable.

c.350 BC: Aristotle claims that everything valuable and useful has already been discovered. Everything knowable and useful can be found in the ‘wisdom of the ages.’ Precludes thinking on perils and risks that have not previously been recorded. Material conditions of mankind cannot radically change, or fail.

c.50 BC: Lucretius speaks of humankind ‘perishing,’ but also asserts that nothing is ever truly destroyed in nature, and that time eventually replenishes all losses. Our world may die, but it will eventually be remade.

c.1100 AD: Persian theologian Al-Ghazâlî develops ways of talking about possibilities in terms of their logical coherence rather than availability to prior experience — crucial to all later thinking on risks previously never experienced.

c.1200: Hindu-Arabic numeral system introduced to Europe, later allowing computation of large timespans that will be instrumental in discovery of the depth (rather than eternity) of past and future time.

c.1300: Islamic and Christian philosophers invent logical possibility as a way of thinking about the ways God could have created the world differently than it actually is. Theologians like William of Ockham conduct first thought experiments on a possible world without any human minds. Still, God would never manifest such a world, they believe.

1350: Black death kills up to 200 million people in Europe and North Africa. Around 60 percent of Europe’s population perishes.

1564: Using new logical conceptions of possibility, Gerolamo Cardano inaugurates the science of probability by thinking of each dice throw as the expression of a wider, abstract space of possibilities.

Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle. Front piece for “Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds,” 1686.

PHASE 2 (1600–1800): COSMIC NONCHALANCE

Modern physics implies that ours is one planet among many, but it is generally presumed that the universe is habitable and filled with humanoids. For every populated planet destroyed, another grows. Species cannot die. Indestructibility of value continues. Inability to recognize existential stakes.

1600s: Copernican Revolution gains momentum. Growing acceptance, following supernova sightings, that planets and suns can be destroyed. But from stars to species, nothing can be lost: It will regrow again elsewhere.

1680s: Breaking with orthodoxy, Robert Hooke and Edmond Halley controversially endorse the idea of prehistoric extinctions caused by massive geological cataclysms. Such conjectures remain fringe, however.

1705: Following Leibniz and Newton’s invention of calculus, long-term prediction of nature becomes feasible. Halley predicts the return of his comet.

1721: Population science takes hold: People start thinking of Homo sapiens as a global aggregate. Baron de Montesquieu writes of humanity expiring due to infertility.

1740s: Reports of behemoth fossil remains found in Siberia and America begin to interest, and confuse, naturalists. Could these be extinct beasts?

1750s: Speculations on human extinction, as a naturalistic possibility, begin to emerge. Yet many remain confident that humans would simply re-evolve on Earth.

1755: Lisbon Earthquake shocks Europe. Influential geologist Georges Buffon accepts prehistoric species extinctions, ponders on which animals will inherit the Earth after we are gone.

1758: Linnaeus adds genus Homo to his taxonomy.[Oriana: this is revolutionary, since it places man in the animal kingdom.] Halley’s comet returns, confirming his prediction.

1763: Thomas Bayes’s revolutionary work on probability is published, providing rules for thinking about probabilities of events prior to any trials. Proves essential to later thinking on risks beyond precedent.

1770s: First declarations that Homo sapiens may be specific and unique to the Earth, and thus contingent upon the planet’s particular conditions. Baron d’Holbach writes that, if Earth were destroyed, our species would irreversibly disappear with it.

1773: Probability theory applied to issues of global catastrophic risk: Joseph Lalande computes likelihood of Earth being hit by a comet intersecting our orbit.

1778: Georges Buffon provides first experimental calculations of the window of planetary habitability, argues that eventually Earth will become irreversibly uninhabitable.

1781: Enlightenment philosophy culminates in Kant’s critique of the way we bias and distort our objective theories with our moral prejudices. We may like the idea that the amount of value is constant in the universe, and that valuable things cannot irreversibly be destroyed, but that doesn’t mean it is true.

1790s: Deep time and prehistoric extinctions accepted as scientific consensus. Modern paleontology and geology are born. They unveil a radically nonhuman past. Georges Cuvier theorizes our planet has been wracked by many catastrophes throughout its past, wiping out scores of creatures.

1796: First notions of long-term human potential — to alter material conditions and alleviate suffering — begin to come together in the work of (e.g.) Condorcet. Meanwhile, Marquis de Sade becomes the first proponent of voluntary human extinction. Pierre-Simon Laplace says that the probability of a cometary collision is low but will ‘accumulate’ over long periods of time. He remains confident that civilization would re-emerge and be replayed, however.

1800: By the century’s close, George Cuvier has identified 23 extinct prehistoric species.

PHASE 3 (1800–1950): COSMIC LONELINESS

Growing recognition that the entire universe may not be maximally habitable nor inhabited.

Cosmic default is hostility to life and value. Many accept human extinction as irreversible and plausible — but not yet a pressing probability.

1805: Jean-Baptiste François Xavier Cousin De Grainville writes first fiction on “The Last Man.” He then kills himself.

1810s: Human extinction first becomes a topic in popular culture and popular fiction. People start more clearly regarding it as a moral tragedy. Value begins to seem insecure in the universe, not indestructible.

1812: Scientists claim the Mars-Jupiter asteroid belt is the ruins of a shattered planet. Joseph-Louis Lagrange attempts to precisely compute the exact explosive force required.

1815: Eruption of Mount Tambora causes famine in China and Europe and triggers cholera outbreak in Bengal. Volcanic dust in the atmosphere nearly blots out the sun; the perturbation provokes visions of biosphere collapse.

1826: Mary Shelley’s “The Last Man,” depicting humanity perishing due to a global pandemic. First proper depiction of an existential catastrophe where nonhuman ecosystems continue after demise of humanity: Our end is not the end of the world.

1830s: Proposing catastrophes as explanations in astrophysics and geophysics falls into disrepute, the argument that the cosmos is a stable and steady system wins the day, this obstructs inquiry into large-scale cataclysms for over a century.

1844: Reacting to Thomas Malthus’s theories of overpopulation, Prince Vladimir Odoevsky provides first speculation on omnicide (i.e. human extinction caused by human action). He imagines our species explosively committing suicide after resource exhaustion and population explosion cause civilization’s collapse. Odoevsky also provides first visions of human economy going off-world in order to stave off such outcomes.

c.1850: Large reflecting telescopes reveal deep space as mostly empty and utterly alien. Artistic depictions of Earth from space begin to evince a sense of cosmic loneliness.

1859: Darwin’s “The Origin of Species” published. Progressivist tendencies in early evolutionary theory fuel confidence in human adaptiveness and inexorable improvement. Fears of extinction are eclipsed by fears of degeneration.

1863: William King hypothesizes that fossil remains found in Neander valley represent an extinct species of the genus Homo. The ‘Neanderthal man’ becomes first extinct hominin species to be recognized.

1865: Rudolf Clausius names ‘entropy’ and theorizes the universe’s heat death. Despite provoking gloomy visions from writers like Henry Adams and Oswald Spengler, it seems far off enough to not be pressing.

1890s: Russian Cosmism launched with the first writings of Fedorov and Tsiolkovsky, making clear the stakes of extinction: They both realize that the only route to long-term survival is leaving Earth. First calls to escape X-risk by securing humanity’s foothold in the wider cosmos.

1895: Tsiolkovsky provides first vision of a Dyson sphere: a sun-girdling sphere that allows full harnessing of solar energy. Suggests mega-scale restructuring of the Solar System in order to further secure human civilization and ensure its long-term future.

1918: Great War provokes many intellectuals (including Winston Churchill) to ponder omnicide, but still a remote possibility. Physicists begin to realize how stringent and rare the conditions of habitability may be. Yet belief in humanoids inevitably re-evolving remains high.

c.1930: J.B.S. Haldane and J.D. Bernal provide first coherent synthesis of ideas regarding long-term potential, existential risk, space colonization, astroengineering, transhumanism, bioenhancement, and civilizational pitfalls. Haldane notes that if civilization collapses, yet humanity survives, there is no guarantee advanced civilization would re-evolve.

1937: Olaf Stapledon further synthesizes these ideas into a comparative study of omnicide in his awe-inspiring “Star Maker.”

PHASE 4 (~1950–PRESENT): ASTRONOMICAL VALUE

Nuclear weapons, for the first time, make extinction a policy issue. It shifts from speculative possibility to pressing plausibility. Anthropogenic risks come to fore. Birth of internet gives critical mass to previously disparate communities. Finally, a rigorous framework for thinking analytically about X-risk is developed around the millennium.

1942: Edward Teller fears that a nuclear fission bomb could plausibly ignite the atmosphere of the Earth and destroy all life. Development of the bomb goes ahead regardless, even though scientists later concluded more research was needed to ascertain that this biosphere-annihilating event would definitely not occur.

1945: Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Atom bomb changes how we relate to intelligence’s place in the cosmos. Faith in inevitable progress takes a battering. Rather than recurrent and omniprevalent owing to its adaptiveness, technological intelligence comes to be considered as potentially rare and even maladaptive.

1950: Leó Szilárd suggests the feasibility of a planet-killing ‘cobalt bomb.’ Enrico Fermi articulates the most significant riddle of modern science, the Fermi Paradox [why don't we have clear evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence?]. Catastrophism begins to reassert itself, with scientists asking whether supernovas caused past mass extinctions.

1950s: The modern field of AI research begins in earnest.

1960s: Initial SETI projects return only ominous silence. Biologists begin to insist that humanoids would not necessarily evolve on other planets. Dolphin research suggests alternative models of intelligence. Technological civilization appears increasingly contingent, heightening the perceived severity of X-risk.

1962: Rachel Carson’s book “Silent Spring” raises the alarm on environmental catastrophe.

1965: I.J. Good speculates that an AI could recursively improve itself and thus trigger a runaway ‘intelligence explosion,’ leaving us far behind. It will be our ‘last invention,’ he muses.

Late 1960s: Fears of overpopulation reassert themselves in neo-Malthusianism. Growing discussion that space colonization is the only long-term guarantee for human flourishing and survival. In line with this, scientists like Freeman Dyson propose large-scale astroengineering as a method to further entrench and fortify the foothold of intelligence within the universe.

1969: First crewed mission lands on the moon.

1973: Brandon Carter articulates the Anthropic Principle. Goes on to derive the Doomsday Argument from it, which uses Bayesian probability to estimate how many generations of humans are likely to yet be born.

1980s: Bayesian methods vindicated in statistics. Luis and Walter Alvarez report findings that lead to consensus that an asteroid or comet killed the dinosaurs. Through this, catastrophism is vindicated: astronomical disasters can significantly affect (and threaten) terrestrial life.

1982: Jonathan Schell pens “The Fate of the Earth,” stressing nuclear threat and the moral significance of the foreclosure of humanity’s entire future.

1984: Derek Parfit publishes “Reasons and Persons.” Population ethics clarifies the unique moral severity of total human extinction.

1986: A year after a hole in the ozone layer is discovered in Antarctica, Eric Drexler publishes “Engines of Creation,” hinting to X-risks from nanotech.

1989: Stephen Jay Gould publishes “Wonderful Life,” insisting that humanoid intelligence is not the inevitable result of evolution. In his “Imperative of Responsibility,” Hans Jonas demands a ‘new ethics of responsibility for the distant future.’

1990s: NASA tasked with tracking threats from asteroids and near-Earth objects. Internet allows convergence of disparate communities concerned about transhumanism, extropianism, longtermism, etc.

1996: John Leslie publishes “The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction.” Landmark text meticulously studying Carter’s Doomsday Argument.

2000: Marvin Minsky suggests that an AI tasked with solving the Riemann Hypothesis might unwittingly exterminate humanity by converting us, and all available matter in the Solar System, into ‘computronium’ so that it has the resources for the task.

2002: Nick Bostrom introduces the term ‘existential risk.’

2010s: Deep learning takes off, triggering another boom in AI research and development.

2012: Researchers engineer artificial strains of H5N1 virus that are both highly lethal and highly virulent.

2013: CRISPR-Cas9 first utilized for genome editing.

2018: IPCC special report on the catastrophic impact of global warming of 1.5ºC published.

2020: Toby Ord publishes “The Precipice.” Covid-19 pandemic sweeps the globe, demonstrating systemic weakness and unpreparedness for global risks.

https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/how-humanity-discovered-its-possible-extinction-timeline/

*

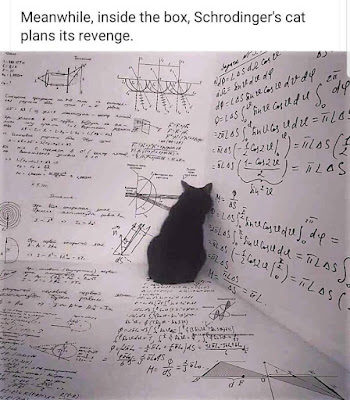

QUANTUM PHYSICS MADE SIMPLE (HAH-HAH!): THE MANY-WORLDS THEORY

~ The quantum rules, which were mostly established by the end of the 1920s, seem to be telling us that a cat can be both alive and dead at the same time, while a particle can be in two places at once. But to the great distress of many physicists, let alone ordinary mortals, nobody (then or since) has been able to come up with a common-sense explanation of what is going on. More thoughtful physicists have sought solace in other ways, to be sure, namely coming up with a variety of more or less desperate remedies to “explain” what is going on in the quantum world.

These remedies, the quanta of solace, are called “interpretations.” At the level of the equations, none of these interpretations is better than any other, although the interpreters and their followers will each tell you that their own favored interpretation is the one true faith, and all those who follow other faiths are heretics. On the other hand, none of the interpretations is worse than any of the others, mathematically speaking. Most probably, this means that we are missing something. One day, a glorious new description of the world may be discovered that makes all the same predictions as present-day quantum theory, but also makes sense. Well, at least we can hope.

Meanwhile, I thought I might provide an agnostic overview of one of the more colorful of the hypotheses, the many-worlds, or multiple universes, theory. For overviews of the other five leading interpretations, I point you to my book, “Six Impossible Things.” I think you’ll find that all of them are crazy, compared with common sense, and some are more crazy than others. But in this world, crazy does not necessarily mean wrong, and being more crazy does not necessarily mean more wrong.

If you have heard of the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI), the chances are you think that it was invented by the American Hugh Everett in the mid-1950s. In a way that’s true. He did come up with the idea all by himself. But he was unaware that essentially the same idea had occurred to Erwin Schrödinger half a decade earlier. Everett’s version is more mathematical, Schrödinger’s more philosophical, but the essential point is that both of them were motivated by a wish to get rid of the idea of the “collapse of the wave function,” and both of them succeeded.

As Schrödinger used to point out to anyone who would listen, there is nothing in the equations (including his famous wave equation) about collapse. That was something that Bohr bolted on to the theory to “explain” why we only see one outcome of an experiment — a dead cat or a live cat — not a mixture, a superposition of states. But because we only detect one outcome — one solution to the wave function — that need not mean that the alternative solutions do not exist.

In a paper he published in 1952, Schrödinger pointed out the ridiculousness of expecting a quantum superposition to collapse just because we look at it. It was, he wrote, “patently absurd” that the wave function should “be controlled in two entirely different ways, at times by the wave equation, but occasionally by direct interference of the observer, not controlled by the wave equation.”

Although Schrödinger himself did not apply his idea to the famous cat, it neatly resolves that puzzle. Updating his terminology, there are two parallel universes, or worlds, in one of which the cat lives, and in one of which it dies. When the box is opened in one universe, a dead cat is revealed. In the other universe, there is a live cat. But there always were two worlds that had been identical to one another until the moment when the diabolical device determined the fate of the cat(s). There is no collapse of the wave function. Schrödinger anticipated the reaction of his colleagues in a talk he gave in Dublin, where he was then based, in 1952. After stressing that when his eponymous equation seems to describe different possibilities (they are “not alternatives but all really happen simultaneously”), he said:

Nearly every result [the quantum theorist] pronounces is about the probability of this or that or that … happening — with usually a great many alternatives. The idea that they may not be alternatives but all really happen simultaneously seems lunatic to him, just impossible.

In fact, nobody responded to Schrödinger’s idea. It was ignored and forgotten, regarded as impossible. So Everett developed his own version of the MWI entirely independently, only for it to be almost as completely ignored. But it was Everett who introduced the idea of the Universe “splitting” into different versions of itself when faced with quantum choices, muddying the waters for decades.

Everett himself never promoted the idea of the MWI. It wasn’t until the late 1960s that the idea gained some momentum when it was taken up and enthusiastically promoted by Bryce DeWitt, of the University of North Carolina, who wrote: “every quantum transition taking place in every star, in every galaxy, in every remote corner of the universe is splitting our local world on Earth into myriad copies of itself.” This became too much for Wheeler, who backtracked from his original endorsement of the MWI, and in the 1970s, said: “I have reluctantly had to give up my support of that point of view in the end — because I am afraid it carries too great a load of metaphysical baggage.” Ironically, just at that moment, the idea was being revived and transformed through applications in cosmology and quantum computing.

In the Everett version of the cat puzzle, there is a single cat up to the point where the device is triggered. Then the entire Universe splits in two. Similarly, as DeWitt pointed out, an electron in a distant galaxy confronted with a choice of two (or more) quantum paths causes the entire Universe, including ourselves, to split. In the Deutsch–Schrödinger version, there is an infinite variety of universes (a Multiverse) corresponding to all possible solutions to the quantum wave function. As far as the cat experiment is concerned, there are many identical universes in which identical experimenters construct identical diabolical devices. These universes are identical up to the point where the device is triggered. Then, in some universes the cat dies, in some it lives, and the subsequent histories are correspondingly different. But the parallel worlds can never communicate with one another. Or can they?

Simple quantum computers have already been constructed and shown to work as expected. They really are more powerful than conventional computers with the same number of bits. Most quantum computer scientists prefer not to think about [mind-boggling] implications. But there is one group of scientists who are used to thinking of even more than six impossible things before breakfast — the cosmologists. Some of them have espoused the Many Worlds Interpretation as the best way to explain the existence of the Universe itself.

Their jumping-off point is the fact, noted by Schrödinger, that there is nothing in the equations referring to a collapse of the wave function. And they do mean the wave function; just one, which describes the entire world as a superposition of states — a Multiverse made up of a superposition of universes.

The universal wave function describes the position of every particle in the Universe at a particular moment in time. But it also describes every possible location of those particles at that instant. And it also describes every possible location of every particle at any other instant of time, although the number of possibilities is restricted by the quantum graininess of space and time. Out of this myriad of possible universes, there will be many versions in which stable stars and planets, and people to live on those planets, cannot exist. But there will be at least some universes resembling our own, more or less accurately, in the way often portrayed in science fiction stories. Or, indeed, in other fiction. Deutsch has pointed out that according to the MWI, any world described in a work of fiction, provided it obeys the laws of physics, really does exist somewhere in the Multiverse. There really is, for example, a “Wuthering Heights” world (but not a “Harry Potter” world).

That isn’t the end of it. The single wave function describes all possible universes at all possible times. But it doesn’t say anything about changing from one state to another. Time does not flow. Sticking close to home, Everett’s parameter, called a state vector, includes a description of a world in which we exist, and all the records of that world’s history, from our memories, to fossils, to light reaching us from distant galaxies, exist. There will also be another universe exactly the same except that the “time step” has been advanced by, say, one second (or one hour, or one year). But there is no suggestion that any universe moves along from one time step to another. There will be a “me” in this second universe, described by the universal wave function, who has all the memories I have at the first instant, plus those corresponding to a further second (or hour, or year, or whatever). But it is impossible to say that these versions of “me” are the same person. Different time states can be ordered in terms of the events they describe, defining the difference between past and future, but they do not change from one state to another. All the states just exist. Time, in the way we are used to thinking of it, does not “flow” in Everett’s MWI. ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-many-worlds-theory-explained?utm_source=pocket-newtab

John Gribbin, described by the Spectator as “one of the finest and most prolific writers of popular science around,” is the author of, among other books, “In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat,” “The Universe: A Biography,” and “Six Impossible Things,” from which this article is excerpted.

Oriana:

In high school we were taught about the quantum leap, and that resonated with me: energy not as a continuum, but in discrete "packets" -- and the sudden appearance of an electron at a higher energy level. Sometimes it looks that way when we examine our own or someone else's artistic development: the person is all of sudden at a different level of skill.

Another quantum concept I fell in love with is "quantum entanglement." When two particles are entangled, then no matter how far they are, if one particle experiences a change, so does the other -- instantaneously. Though this is purely anecdotal, it was impossible for me not to think of people in love, rather than particles. If one member of the couple is danger, the other one, even if a continent away, suddenly experiences inexplicable anxiety. If one of them dies, the other one feels "hit" by something terrible, and may even collapse.

I realize that this is not how physicists talk about quantum mechanics. But, being a lay person, I can't help but think of a quantum leap and quantum entanglement in human terms. And who knows . . . the universe is full of riddles.

*

GHOST FORESTS ALONG THE ATLANTIC COAST

~ In the Arctic, rapidly melting ice is the surest sign of climate change. In less northern latitudes, it’s the increasingly early onset of spring or the rising frequency of severe weather. On Mid-Atlantic and Gulf Coast shores, though, the loudest example of the impacts of warming temperatures are the stands of dead trees known as ghost forests.

“Ghost forests are the best indicator of climate change on the East Coast,” says Matthew Kirwan, a professor at William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science studying coastal landscape evolution and author of a 2019 review in Nature Climate Change on the appearance of these forests. “In rural, low-lying areas, there are so many dead trees and farmland that’s either stressed or abandoned that the signs of sea level rise are obvious.”

Sea level is expected to increase between 0.4 and 1.2 meters (that’s 1.3 to 3.9 feet) by 2100. And on the East Coast between Massachusetts and North Carolina, sea level is currently rising three times faster than the global average. This is due in part to a long-term geologic processes: when ice sheets weighed down northern areas of the country during the last Ice Age, land adjacent to the ice rose up in a see-saw effect. Since the ice melted, that ice-adjacent land—including the Mid-Atlantic coast—has been sinking back down. It’s also related to a slowing Gulf Stream; as a result, less water is being moved away from the Atlantic coast.

Bare trees killed by encroaching salt water in Robbins, MD; Matthew Kirwan

Much of the Mid-Atlantic and Gulf Coast areas threatened by sea level rise are private, rural lands made up of forests and farms. As saltwater seeps into the forest soils, the trees die of thirst because their roots cannot take up water with high salt content. They may grow weak and die slowly, or, if a storm brings in a flood of seawater, a whole stand of trees might drown at once. What’s left behind are bare trunks and branches—a ghost forest. “When I moved down to the Mid-Atlantic, I was totally struck by these bleached, dead trees,” says the review’s coauthor Keryn Gedan, tidal wetland ecologist at George Washington University. “It was so extensive that I immediately wanted to study it.”

In the Chesapeake Bay area, over 150 square miles of trees have turned to ghosts since the mid 1800s, the review notes. And about 57 square miles of forests along the Florida Gulf Coast have met a similar fate in the past 120 years. Since 1875, ghost forests have been growing at an increasing rate.

As the leaves and needles fall off these dying trees, a community of salt-tolerant marsh plants moves in. It’s not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, coastal wetlands are some of the most valuable ecosystems. These plants filter out pollutants and excess nutrients in the waters that flow into them, they protect shores from erosion by waves, and they store even more carbon than forests do. Coastal wetlands also slow floodwaters, protecting properties and lives from the destruction of storms. “If you’re looking for storm protection, tidal wetlands are a great thing to have,” says Gedan.

As sea levels rise, it’s unknown whether the total area of coastal wetlands on the Atlantic coast will increase or decrease. This depends, in part, on whether the marshes can move upslope fast enough to outpace the water drowning them. Another factor is how landowners will respond to the salty water creeping toward their properties. A ghost forest has little value for timber, and salty soil kills crops. Landowners might become inclined to build structures to block the seawater.

But because of the importance of these ecosystems—the habitat they provide and the many services they give us—Gedan hopes that’s not the case. “We have to both work to understand landowner behavior in response to sea level rise, and we need to guide landowners’ decisions with information for them and incentives to promote the behaviors that we want to see,” she says. “If we want to see coastal wetlands in the future … then we need to incentivize landowner behavior that will allow upland conversion to occur.”

That could mean developing programs that pay landowners to let the ghost forests and salt marshes move in. It could also mean offering landowners advice on how to reap the most benefit from their land as it makes this transition, such as by helping an owner of forested land know when to fell trees to profit off their value as timber (dying or dead trees aren’t worth much).

In the future, some areas will grow more ghost forests than others. Along less steep coasts, saltwater and marshes can more easily move inland.

On the Gulf Coast, seawater is expected to inundate three times as much as the current area of coastal wetlands, which means we could have that much more marshes in the future. But scientists are not sure whether these new wetlands will be of the same quality as ones currently being drowned under rising seawater. A lot of new ghost forest-wetlands of the Delaware Bay area, for example, are dominated by invasive reeds, so native wetland plants—and the animal species that depend on them—can’t live there.

As much as we may try to carefully adapt to the impacts of human-caused climate change, it’s challenging to simply recoup the ecosystems we’re losing. Says Kirwan, “If we get a gain or break even [with coastal wetlands], will the ecosystem function the same even though it’s a different kind of marsh?” ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/ghost-forests-are-sprouting-up-along-the-atlantic-coast?utm_source=pocket-newtab

*

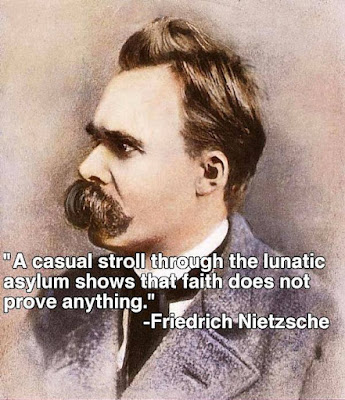

The two great European narcotics: alcohol and Christianity. ~ Nietzsche

It's the unexpectedness of the second narcotic that makes this a startling statement. As someone here said, Nietzsche is the master of the disruptive aphorism.

To my knowledge, Nietzsche wasn't familiar with Marx's "religion is the opium of the people" (Opium des Volkes), published in 1844 but hardly paid much attention to back then (if Marx had to depend on his income from publishing, he would have starved; in fact, he did complain at one point: "both of our servants are reduced to eating nothing but potatoes"). Yet it may be assumed that intellectuals of the era had formed this opinion in one form or another, perceiving religion as a consolation favored by the poor and the desperate. "Your reward will be in heaven" and "Christ will dry every tear" were attractive promises that until fairly recently were not regarded as "pie in the sky.”

And the New Age movement? It offers what might be called an individualist-universalist perspective. Louise Hay (whose wisdom has been helpful to me) says, “In the Aquarian Age we are learning to go within to find our savior. We are the power we are looking for. Each of us is totally linked with the Universe and with Life.”

Does Nietzsche's observation still hold? When faced with an adversity (or, as Dave Bonta said, "Shit happens" is a translation of the First Noble Truth), some people drink, others pray, still others go to a therapist or a psychic (therapists themselves go to psychics). Some meditate and seek an answer within -- and now, increasing, many seek answers on the Internet.

It's interesting that I first remembered this quotation as "the two great American narcotics" -- and, not sure who said it, I wondered if Oscar Wilde would have been so daring. Well, that's the way the brain works -- instead of accuracy, it transforms a statement into what is relevant and more familiar to us. (An besides, America can be seen as an extension of European culture -- though there are some important differences, e.g. in religiosity.)

*

GOD’S FOOTPRINTS

~ A little over forty miles north-west of Aleppo, in northern Syria, set high above a valley, there lie the remains of a gateway to heaven: an ancient temple, the meeting place of the heavenly and earthly planes. A colossal carved lion, its teeth and claws bared, guards the approach. Surrounded by walls of black basalt, its floor paved with pale flagstones, the temple is the dwelling place of a long-lost deity, worshipped by the Syro-Hittites—close cultural cousins of the ancient Israelites and Judahites. Partially destroyed in the eighth century BCE, and devastated again in a Turkish airstrike in 2018, this temple at ‘Ain Dara is the closest we can come to the temple that stood in Jerusalem at the same time. Its structure and iconography map so precisely onto the biblical description of Solomon’s temple, it is as though they shared the same divine blueprint.

When I visited the temple in 2010, shortly before the war in Syria began, wild summer flowers dotted the grass at the temple’s edges, dappling the feet of guardian beings and lions lining the base of its now broken walls. I took off my shoes and walked barefoot up the warm, shallow steps to the entrance of the temple’s outer courtyard. And then I saw them: two giant footprints, each about a meter in length, carved into the limestone threshold; neatly paired, they were pointing into the temple. The toes and balls of each footprint were softly, deeply rounded, as though they had been pressed firmly into wet sand. I stepped into these enormous, yet delicate feet. They dwarfed my own. I was standing in the bare footsteps of a god. As I looked ahead of me, I could see the vastness of the deity’s stride into the temple: the left foot had been imprinted again a few meters inside the temple, this time on the entrance to the vestibule; ten meters or so beyond that was the right footprint, inside the holy of holies—the innermost sanctum, where the deity dwelt. The god had arrived home, and I was there to witness it.

This was the grand residence of a deity whose precise identity has long since been forgotten. But although this god would fade from view, their bodily presence was clearly marked by those giant footprints, traveling in just one direction: inside. There were no exiting footprints; no indication that the deity had left the temple. Rather, the footprints signaled the permanent presence of the god within. It is this sense of material presence that lies at the heart of ancient ideas about deities. The perceived reality of the gods was bound up with the notion that for anything or anyone to exist—and persist—is to be present and placed in some tangible form. It is to be engaged with and within the physical world. The footprints at ‘Ain Dara communicated precisely this sense of placement. They marked the exact place of the deity within the world of humans. At this spot, where the heavenly and earthly realms met, the god was manifest and accessible to worshipers. The deity took on a social life.

The power of the footprint to communicate complex ideas about social presence says as much about what it is to be human as it does about what it is to be a god. When we see footprints, we recognize them as material traces of being; a frozen moment of movement or stillness; a memorial—however fleeting—to a reality by which we configure ourselves in the world and with those around us. Footprints capture something of the extraordinary and the familiar about human life—the orchestrated and haphazard, the durable and flimsy. A toddler’s excited footsteps imprinted in sand or snow. Celebrity shoe-prints set in concrete on Hollywood Boulevard. Muddy shoes accidentally tracked across a kitchen floor.

The footprints of a group of Australopithecus afarensis, some of our earliest bipedal hominid ancestors, solidified in volcanic ash, three and a half million years ago, in Laetoli, northern Tanzania. The famous dusty bootprint of Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon. A footprint isn’t simply a trace or a representation of the foot. It is a material memory of its owner treading upon the surface on which the print appears, conjuring the presence of the whole body—the whole person. Our feet are not simply the pedestals on which we stand, or the motors by which we move, but the foundations of our presence in the world.

The impressions made by our feet have imprinted themselves into the religious cultures we have created. The footprints of gods and other extraordinary beings are celebrated and venerated all over the globe: divine or mystical beings are said to have left their footprints in rock art across Scandinavian and British sites of the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. On an island sacred to the ancient Inca in Lake Titicaca, separating Bolivia from Peru, the footsteps of the sun god Inti are displayed. In southern Botswana, the giant hunter Matsieng left his footprints in wet earth around a waterhole. The extent to which the footprint appears in the ritual settings of human communities across time and space is remarkable.

Some of the earliest examples of divine footprints derive from the ancient sanctuaries of deities who once traveled the lands bordering the Mediterranean. According to Herodotus, the enormous footprint of Heracles could be seen in a rock by a river in Scythia—a print Lucian mockingly claimed to be bigger than the footprint of the god Dionysus, next to it. The Egyptian goddess Isis left impressions of her feet across the Graeco-Roman world: at Maroneia, in Greece, for example, her supersized prints appear alongside those of one of her consorts, Serapis. This divine couple is also invoked in a first-century BCE inscription upon a marble slab in Thessaloniki, beneath which the goddess has approvingly left her footprints.

Such is the power of divine footprints that they often became sites of competing religious claims. Most famous, perhaps, is the depression in rock akin to an enormous footprint on Sri Pada, a high peak in south-central Sri Lanka. For Tamil Hindus, it is the print of Shiva, left as he danced creation into existence; for Buddhists, the footprint belongs to Gautama Buddha, who pressed his foot into a sapphire beneath the rock; for Muslims, it is the print left by Adam as he trod on the mountain following his expulsion from Eden; for Christians, it is the footprint of Saint Thomas, who is claimed to have brought Christianity to the region. Jerusalem, too, has its share of contested holy footprints. As he ascended to heaven, Muhammad is said to have left a single footprint upon the exposed spur of bedrock enshrined beneath the Dome of the Rock, in Jerusalem.

But for Christian pilgrims and Crusaders of the medieval period, the footprint on this sacred rock belonged to Jesus, whose foot is also said to be imprinted on the Mount of Olives, where it has been venerated since at least the fifth century CE. Whether the work of geological erosion, local folklore or ritual art, each of these footprints communicates something of both the earthiness and otherworldliness of a divine or holy being.