*

JACKPOT

now I lay me down to sleep

I pray the lord my soul to keep

and if I die before I wake

I pray the lord my soul to take

this little poem ran through my mind

last night

as I lay in bed, slipping

off to sleep

a memory of my bedtime prayer

when I was a small child

and as I remembered the prayer

I remembered also that in the mind

of the child I was, it did not

seem so unlikely that my last thought

before sleep might be

the last thought of my life

I pondered it then as sleep

beckoned, pondered it as a child ponders

all that mysteries that surround it,

thought about what it would mean to have

it all end sometime

during the night, the world without me

disappearing as I did also

(even as a child I knew

it was my presence, my conscious,

that made the world real

and that without my dreams

the world itself would be just another

fading dream)

a conviction of the imminence of death

as each night’s sleep began…

I’ve been a fatalist all my life,

and maybe that explains

it

so that even now, though I drift into sleep

every night with plans for the next

day, that conviction that

there well could be no next day,

the acceptance of death’s constant presence

and inevitability, lies also in that repository of

childhood dreams

it is the upside of a fatalistic outlook

that makes each new day

a surprise party,

like winning a casino jackpot,

beating the odds, winning another

chance at life

~ Allen Itz

*

Oriana:

I know the feeling — first a certain anxiety about falling asleep, since it seems like dying, and then the amazement of waking up in the morning, which does feel like a resurrection, not just of me but of the whole world.

Kerry:

That bedtime prayer was my older brother's.... we shared twin beds ...I thought it diabolical ...and never liked it except for the rhythm....

Mine was also a given but I was allowed to add a lot at the end... sensible and kind...though mundane.

I thank You for food and drink

I thank you for the power to think

I thank you for each happy day

I thank you for long hours of play

I thank you for bright butterflies

I thank you for my own two eyes

I think you for the birds that sing

I thank you for everything

Then I would add what I wanted …please may mommy and daddy and everyone live a happy life may those who are sick get well ...and then whatever.

Oriana:

Mine was just one Our Father and one Hail Mary. That late in the day the words meant nothing to me. Sometimes I fell asleep before I was done, and then during confession duly reported, "inattentive during prayers."

Ah, but the child's ability to fall asleep so easily! Sleep was the real prayer.

JOAN DIDION’S FEAR OF NOT DYING: THE PORTRAIT OF THE WRITER WHEN SHE WAS IN HER SEVENTIES

~ Opening the door to her cavernous Upper East Side apartment, the writer murmurs a monotone “hello” but doesn’t shake hands. There’s bottled water, she says, waving in the direction of a double-size Sub-Zero in her double-size kitchen. She wears a sun-faded white sleeveless skirt-suit fashioned from the raw silk curtains in her old house in Brentwood. She is 76 but looks older. She has always been birdlike, five two and wire-thin, but never quite this frail. Her arms are translucent river systems of veins. Her face is worn, unyielding. “She doesn’t express it,” says her agent and friend Lynn Nesbit, but “you see the pain in her face.”

It’s true that drawing out her feelings in person is a doomed project—that ice is thicker than it looks. Possibly the best living American essayist and probably the most influential, Didion has always maintained that she doesn’t know what she’s thinking until she writes it down. Yet over the past decade, she’s been writing down more about her own life than ever before. If you want to know about her upbringing, read Where I Was From, about the delusions of her California pioneer ancestors. If you want to know how she feels about the sudden 2003 death of her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, you can read The Year of Magical Thinking, her stark but openhearted account of emotional dislocation. And if you want to know how she feels about the drawn-out death of her adopted daughter, Quintana Roo, two years later at the age of 39, you can order her memoir, Blue Nights, on Amazon.

Having dissected the pain of others for decades, Didion has spent the last few years turning the scalpel on herself. This introverted late phase is as coherent and revealing as Philip Roth’s. The essayist who once reprinted her own psychological evaluation has always used her personal story, but in her early years she only feinted at confession on the way to observations of the larger world. Beginning with Where I Was From, which presents California’s history as her own, she’s reversed the bait-and-switch, writing about those close to her as a way of bringing herself, finally, into public view.

“Writers are always selling somebody out,” Didion wrote at the beginning of her first essay collection, 1968’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. That warning, later echoed infamously by Didion’s contemporary Janet Malcolm, is a statement of mercenary purpose in the guise of a confession: not a preemptive apologia but an expression of grandiose, even nihilistic ambition. We think of memoirs, especially memoirs of grief, as a soft art, one that necessarily humanizes the writer. And Didion the memoirist is painfully human—heartsick, vulnerable, and honest about her fears. But she’s also as ruthless as she’s ever been, tearing down the constructs she’s built to protect herself and her family. If she’s selling anyone out with Blue Nights, it’s Joan Didion.

The book is about many things: mental illness, fate, and our overgrown faith in medical technology. But it is most importantly a reckoning with her shortcomings as a mother.

Quintana died just six weeks before the publication of The Year of Magical Thinking, after a lifetime of suffering and a series of cascading illnesses (pneumonia, septic shock, pulmonary embolism, brain bleeding) exacerbated by emotional difficulties for which Didion wonders if she’s partly responsible. “I don’t think anybody feels like they’re a good parent,” Didion tells me. “Or if people think they’re good parents, they ought to think again.”

In Blue Nights, Quintana’s truncated, troubled life is interwoven with Didion’s own physical decline. The title, she explains, comes from those twilights that linger in northern latitudes in the early summer, giving the eerie impression that darkness might never come. “I found my mind turning increasingly to illness, to the end of promise, the dwindling of the days, the inevitability of the fading, the dying of the brightness. Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but they are also its warning,” she writes. And later: “I was no longer, if I had ever been, afraid to die: I was now afraid not to die.”

*

The Year of Magical Thinking transformed Didion, who looks today like the world’s unlikeliest self-help guru. Perched on a white slipcovered love seat in front of the fireplace in her split-level living room—which is where her husband died—she speaks reluctantly but in sudden crescendos, punctuated by nervous laughs. On a vast coffee table between us sit neatly stacked books of all sizes—many of them unread, she tells me. And all around—on shelves, mantels, and dressers, and arrayed along a hallway that leads to two offices and two bedrooms—are pictures of mostly bygone family. “I hadn’t thought that I was generally a pack rat, but it turns out I am,” she says, showing me around the orderly apartment. “Everything here is a mess.”

By far the best-selling book of her nearly half-century career, The Year of Magical Thinking sold more than a million copies and made its author, for the first time, a truly public figure, even a kind of literary saint—no longer a cult favorite but a celebrity writer embraced by book clubs and heralded in airport bookstores. That success was a disorienting shock, she says—especially the crowds. “People would stop me in airports and tell me what it had done for them,” she tells me. “I had no clue; I hadn’t done anything as far as I could see.” When that happens, “I go remote on them,” she says. “I actively do not want to be a mentor. I never liked teaching, for that reason.”

Nonetheless, she got busy touring. “I promised myself that I would maintain momentum,” she writes dispassionately in Blue Nights of a mourning period she filled with distractions. She let Scott Rudin persuade her to adapt Magical Thinking into a play directed by playwright David Hare. Vanessa Redgrave was the star. Critics would complain Redgrave was far too large and strident to play Didion, who weighed less than 80 pounds. The crew set up a table backstage, which they called Café Didion, in order to make sure she ate daily.

And Didion kept working, tirelessly. There were screenplays, which she had so often written with her husband: a movie on Katharine Graham and an adaptation of her novel The Last Thing He Wanted. There were also articles for The New York Review of Books, including a takedown of Dick Cheney and a devil’s-advocate essay on the vegetative Terri Schiavo—an essay she says she wrote for reasons unrelated to Quintana’s hospital experiences.

She continued to see friends, as she still does today, a few times a week. Some of them insisted Didion take a vacation. She was in her seventies, after all, and had just lost both members of her immediate family, then wrestled with the loss in a remarkably public way. One day, during the run of the play, she came down with a very bad case of shingles. A doctor said she was making an “inadequate adjustment to aging.” She corrected him: She was making no adjustment to aging. Instead of taking a vacation, she began to think about another, more painful project.

“My intention had been to make Magical Thinking less polished, and I thought I had done that until I finished it,” Didion says. “And then I realized that it was exactly as polished as everything I wrote had always been.”

She set out to try something rougher—though not quite as rough, she says, as the book she ultimately published. “I was going to make it more theoretical than it turned out to be, less specifically about Quintana,” she says. “It was going to be much less personal.” Instead, she wrote the most personal, wrenching book of her life. Magical Thinking, not exactly a breezy piece of work, “simply wrote itself,” she says. “This did not write itself.”

Didion has always been known for the crystal sheen of her writing—as a child she retyped pages from A Farewell to Arms—and the seeming casualness of her prose has long divided readers. The critic John Lahr once condemned Didion for suffusing her writing with nothing more than her own anomie, which he memorably called “the Brentwood Blues. She meditates on her desolation and makes it elegant,” he wrote. “Sent to get the pulse of a people, Didion ends up taking her own temperature. Narcissism is the side show of conservatism.”

And yet Didion owes her stature to more than solipsistic style. She’s also a soothsayer, always timely and often prescient. By virtue of her age—just ahead of the baby-boomers, young enough to recognize them and old enough to see them clearly—Didion has made a career as a canary in the American coal mine. In the sixties, she observed, from the vital center, the dangers of the counterculture, and long before Woodstock. Beginning in the nineties, she anticipated the shallow polarization that now dominates American politics. In the aughts, just in advance of aging contemporaries like Joyce Carol Oates, she anatomized the pain of widowhood. And, in Blue Nights, she warns against the false comforts of helicopter parenting and industrial medicine.

In each case, she makes the story her own—slyly conflating private malaise and social upheaval, a signature technique that has launched a thousand personal essayists. But sometimes it’s difficult to tell which of her confessions are genuine and which calculated for literary effect, how much to trust her observations as objective and how much to interrogate them as stylistic quirks. Her clinical brand of revelation can sometimes feel like an evasion—as likely to lead the reader away from hard truths as toward them.

In person, Didion does concede to me the occasional hard criticism. She admits that her writing might lack empathy, even human curiosity. “I’m not very interested in people,” she says. “I recognize it in myself—there is a basic indifference toward people.”

*

But there is one critique that still gets her hackles up, decades later. In “Only Disconnect,” published in 1980, Barbara Grizzutti Harrison called Didion a “neurasthenic Cher” whose style was “a bag of tricks” and whose “subject is always herself.” That wasn’t the worst of it: “My charity does not naturally extend itself,” Harrison wrote, to “someone who has chosen to burden her daughter with the name Quintana Roo.” Asked 25 years later, in this magazine, whether she felt Magical Thinking was criticproof, Didion replied, “Not if my daughter’s name wasn’t criticproof.”

It’s a telling scar. From the very beginning of her career, family has been the secret heart of Didion’s work, the empathic center of that otherwise icy moral universe. Critics may charge Didion with a lack of feeling for her subjects, but her reverence for blood ties and her esteem for clan loyalty animate everything she wrote about the social disorder wrought by the generation that followed hers.

Didion took the title of Slouching Towards Bethlehem from the apocalyptic Yeats poem “The Second Coming,” with its proclamation that “the center cannot hold.” For her, the true center that could not hold was the family—sacrificed, she felt, on the altar of universal love and self-fulfillment. No Didion scene is more evocative than the kicker of the title essay of Slouching Towards Bethlehem: A neglected 3-year-old hippie child, having just burned his arm in a fire, is caught chewing on an electrical cord.

The real engine of this scene, Didion now acknowledges, was Quintana, whom she worried that she was herself neglecting. “I was leaving her alone while I was in San Francisco,” she says. “I went home to Los Angeles on weekends, and she would turn her face away when I would kiss her because I had been away for a week. So I was feeling very strongly the sense of failing at parenting there.” In her libertarian cri de coeur, “On Morality,” Didion criticizes the tendency of social movements to “assuage our private guilts in public causes.” It wasn’t just the American family she was worrying about, but her own.

Blue Nights dwells on the warning signs of Quintana’s incipient instability, which one doctor diagnosed as borderline personality disorder. It started, Didion now believes, at a very young age, perhaps not long after she was adopted at birth. (Didion and Dunne had tried and failed to conceive for two years.) As a toddler, Quintana would go on about a “Broken Man” who haunted her nightmares. At age 5, she called Camarillo, the mental institution rumored to have inspired “Hotel California,” to ask what she should do if she went crazy—a story Didion insists is not just family lore. When Quintana got chicken pox, she told her parents coldly, “I just noticed I have cancer.”

At 14, she informed them that she’d written a novel “just to show you”: It involved a girl named Quintana who got pregnant. Her parents “said that they would provide the abortion but after that they did not even care about her any more … Her father had a bad temper, but it showed that they cared very much about their only child. Now, they didn’t even care any more.”

Didion had always wanted to be a novelist. Like Tom Wolfe and Susan Sontag, she grew up thinking she was put on Earth to write fiction, and it’s in her novels that she is typically most revealing and reflective. They usually feature a distant woman, intelligent but inscrutable and generally fatalistic. Almost invariably, she has a troubled daughter.

In Play It As It Lays, she writes about a 4-year-old who’s in treatment for “an aberrant chemical in her brain.” In A Book of Common Prayer, a broken woman finds herself in a fictional banana republic, dreaming of being reunited with her daughter, a fugitive radical. (“It was about having your children grow up,” Didion realizes now. “Quintana was reaching that age.”) Inez Victor, the mother in Democracy, published when Quintana was 18, has the all-too-familiar “capacity for passive detachment,” but in the course of the novel she is forced into action when her daughter, Jessie, runs off to Vietnam just before the 1975 evacuation of Americans. One night, Inez discovers Jessie prostrate in her bedroom with a heroin needle in her Snoopy wastebasket. “Let me die and get it over with,” Jessie says. “Let me be in the ground and go to sleep.”

“Let me be in the ground and go to sleep,” a teenage Quintana is quoted as saying, several times, in Blue Nights. Or, rather, she is quoted once, while depressed, on the floor of their Brentwood home. But, having appropriated the line for Democracy, Didion appropriates it once more in Blue Nights, repeating the phrase again and again throughout the book, like a mantra of self-flagellation.

It’s unclear when exactly Quintana began exhibiting what Didion calls “quicksilver changes of mood,” or when she first became depressed, or when she began to have problems with alcohol. It’s also unclear, even in Didion’s mind, whether she and Dunne had anything to do with it. Dissecting herself in Blue Nights, Didion seems unable to decide if she was too coddling as a mother—“I had been raising her as a doll”—or too cold—“Did we demand that she be an adult?” She did once bring up her parenting with a grown-up Quintana, she says. Her daughter reassured her, sort of: “I think you were a good parent, but maybe a little remote.”

If Didion was remote with Quintana, she was consumingly close to the third member of the family, her husband, John Gregory Dunne. The central, immutable premise of both memoirs is John and Joan’s idyllic marriage—the one Utopia in which the skeptical Didion placed her faith. “They were always together,” as their old friend Calvin Trillin puts it. “They could finish each other’s sentences.” Working on screenplays together, they did. Beginning with The Panic in Needle Park, they embarked on a lucrative career that put them in rarefied celebrity company and earned them, for the indignity of not having final cut, paychecks that made them two of the highest-paid screenwriters in Hollywood. In this setting, as in others, Joan was the greater writer but the lesser social force—the observer. “I liked being on set more than John did,” Didion says, “because you could just sit there and have other people do things around you. You could just watch.”

Quintana didn’t always fit easily into this universe of two; sometimes she must have felt like the clumsy apprentice in a sleek dream factory. Susan Traylor, Quintana’s best friend since nursery school, used to envy the structure of Quintana’s household—but Quintana envied the freedom of Traylor’s. “It used to drive her crazy that her parents were so on top of things,” says Traylor. She remembers warmly one ride to elementary school with Dunne and his daughter. Quintana showed him a paper she was going to turn in. He asked her if she’d given it to him or Didion to proof, and when she said no, he threw it out the window. There’s an echo of that moment in Blue Nights, when Didion unearths a journal Quintana kept—in which Quintana dwelled on her “present fear of life”—and finds herself proofreading it. “Considerable time passes before I realize that my preoccupation with the words she used has screened off any possible apprehension of what she was actually saying.”

Then, one Saturday in 1998, Quintana got a FedEx package from her birth sister, whom she had never known, and flew down to Dallas to meet the rest of the clan. (Didion had learned the names of Quintana’s biological parents by accident, and writes that she dreaded the possibility that they’d ever meet Quintana.) Her birth mother began calling all the time, interfering with her job. Quintana tried to declare a temporary break, but her birth mother overreacted, disconnecting her phone. Soon after that, her birth father got in touch. He wrote, “What a long strange journey this has been.” Quintana responded with what became the funniest line in Blue Nights. “ ‘On top of everything else,’ she said through the tears, ‘my father has to be a Deadhead.’ ”

Dunne’s nephew Griffin Dunne says meeting the birth family “had an enormous effect on Quintana, and not for the better.” Her newfound relatives “were a troubled lot, and it struck Quintana: ‘That’s my DNA too; am I more like that or am I more like my parents?’ It was the beginning of a real emotional struggle.”

“Because she was depressed and because she was anxious she drank too much,” Didion writes in Blue Nights. “This was called medicating herself. Alcohol has its well-known defects as a medication for depression but no one has ever suggested—ask any doctor—that it is not the most effective anti-anxiety agent yet known.”

At loose ends, Didion began seeing a therapist. “I think she was very interested in how she could better communicate with Quintana,” says a friend. The counseling helped her realize she’d been infantilizing her grown daughter. These are thoughts that went straight into Blue Nights: “She was already a person. I could never afford to see that.” In person she is more pointed: “I had treated Quintana like a baby and not a human being.”

She also realized that she might have treated herself the same way—reluctant to play the grown-up in the family. “One of her abiding fears,” she writes of Quintana, perhaps projecting her own worries, “was that John would die and there would be no one but her to take care of me.” But gradually, Didion did begin to grow more assertive and more reflective, prompted by her therapist, by her troubles with her daughter, and especially by the death of her mother, in 2001.

Unsurprisingly, the first sign of that transformation was in her writing. Where I Was From tore apart the California pioneer mythos that had shaped her emotional life and driven so much of her work. “That was a book that was very important to her,” says her friend Christopher Dickey, “and it didn’t get much of a reception at all. People didn’t understand it. My wife and I both read it in galleys, and my wife, who is very sensitive and very close to Joan as well—she said, ‘This is really about Quintana … She was kind of Slouching Towards Quintana.’ ”

Near the end of the book, Didion walks with her mother and Quintana through a re-created section of Old Sacramento. Quintana is 5 or 6, and Didion wants to explain her family’s roots there. But then, she realizes, “Quintana was adopted. Any ghosts on this wooden sidewalk were not in fact Quintana’s responsibility,” she writes. “In fact I had no more attachment to this wooden sidewalk than Quintana did: It was no more than a theme, a decorative effect. It was only Quintana who was real.”

How many vast shelves of literature are devoted to the misunderstandings between fathers and sons and mothers and daughters,” asks Dickey, who wrote a memoir about his own father and thinks it’s obvious why Magical Thinking was so much easier to write. “When you have a partner, someone you love, who’s your age, with the same terms of reference, and you are together for decades, you really do understand each other,” he says. “Your child is never going to be understood in that way.”

Didion agrees. “I guess I do know her better than anyone else. But as well as I knew her, I barely touched knowing her,” she says. “I couldn’t possibly have written a biography of her.”

“The goal of the book was to get it off my mind,” says Didion of Blue Nights. But she contradicts herself just a moment later by saying it was meant to “bring it back.” Anne Roiphe, one of the authors who followed Didion into widow-memoir territory, wrote in her book Epilogue, “I will be sad often but not always.” Didion says she doesn’t feel that way about Quintana, at all. “I will be sad always,” she says.

“I don’t think she’s a masochist,” says Dickey. “But one of the things that happens when you write an intimate memoir, an honest memoir, is that you think it will be cathartic—that you can say, ‘I have now positioned this memory, and now I can move on.’ But very often it just doesn’t work that way.”

https://nymag.com/arts/books/features/joan-didion-2011-10/

Oriana:

It’s the “Roo” in “Quintana Roo” that strikes me as rather awful. Was it meant to be funny? To invoke a “kangaroo”? Did the parents want to satisfy their need for a unique name rather than think of what’s best for the child?

Yet people with worse names have turned out all right — and sometimes took the brilliant action of having their name legally changed. An ugly name is not doom — but it certainly doesn’t help. Still, "Quintana," by itself, is not what anyone would call awful. And my guess is that no one mocked the girl by calling her "Roo."

I think Quintana’s problems were chiefly genetic — alcoholism runs in the family, and Quintana’s biological family seems to have been the unfortunate sort. I would certainly not blame Joan’s adoptive parents for the child’s alcoholism or her various mental disorders — the “borderline personality disorder” seems to fit best. At its core lies an intense fear of abandonment. Joan Didion wrote that adoption usually works well for the adoptive parents — they love the baby from Day One — but until recently no one voiced the opinion that adoption may not always work so well for the child.

And I wonder: had Didion known that alcoholism and the bipolar disorder are largely genetic, would she have avoided the torture of being self-critical about her mothering? No, Joan Didion did not cause her adoptive daughter to be bipolar, nor did she cause her to be an alcoholic. Alas, Didion belonged to the generation when everything that was wrong with the child was blamed on the mother.

There is, however, a certain factor here that touches on mental disorders: when the parents adore each other, the child realizes that she is loved less than the mother's life partner. And that may make the child think she is not important, because she isn't loved loved as totally as the other parent. And that's something to be depressed about.

What stays in my mind is that “The Year of Magical Thinking” turned out to be easy to write — “It wrote itself.” I think that’s a testimony of the great love and closeness between Joan Didion and Gregory Dunne, who were literary collaborators as well as life partners. Blue Nights was the opposite of easy writing; it brought back the pain of dealing with Quintana’s multiple problems and her drawn-out dying. I admire Didion’s ability to write that book at all.

Great personal pain may make writing (or even talking) about certain subjects impossible; it’s almost a miracle that we have personal accounts of the Holocaust. And even those accounts — do they say everything, or is the worst still buried in silence?

Mary: WANTING THE BIG SLEEP

It seems to me both Joan Didion's struggle with herself as "mother" and the damage that can result from making New Year's resolutions can be answered by the same acts: forgiveness and radical acceptance. We are too ready to judge ourselves as failures, often in regard to things we have no control over . Quintana's suffering and decline owed most to genetics, not to Didion's behavior as parent, yet she examined herself again and again trying to pin down how and where she failed, what responsibilities she had and how she had avoided them .

Another thing that struck me here was Didion's "fear of not dying" and Quintana's plea to "Let me die and get it over with. Let me be in the ground and go to sleep." In my mother's last years she became desperate to sleep, claimed she would feel better if only she could sleep, was always trying to sleep. The truth of it was she did not have trouble sleeping, actually slept most of the time. But she wanted to sleep ALL of the time.

Fear of not dying? Wish to get it over with? Yes. But to me the essence of these wishes is for an end to consciousness, to be unconscious, asleep, rid of the pain of awareness, when awareness has become nothing but pain. A death wish that is a wish to be rid of the pain of consciousness. Not to know, not to see, not to think, not to feel.

And to come full circle, when does consciousness mean nothing but unceasing pain?? When we judge ourselves as failures, our lives and efforts as useless, hopeless, unloveable, unforgivable, unchangeable. There the rise of self disgust and self condemnation can become predictive and overwhelming, the pain of consciousness so severe we would do anything to end it.

We need, not narcissism, but both honesty and forgiveness, to allow ourselves kindness and forbearance, permission to practice, to stumble and recover as many times we need to keep moving on.

*

DIDION ON WRITING AS AGGRESSION

~ In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions—with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space. ~ Joan Didion

Oriana:

I remember reading somewhere that Joan Didion discovered that in writing she could be aggressive . . . I had to think about it for a while, and finally came to agree that basically women are supposed to be sweet and suppress any aggressive feelings, to look on the bright side etc. Una invariably corrected me if I dared sound negative. There's something to that, but then we lose the sense of truth, or at least of what is closer to the reality of any situation.

Mary:

And there you have it. Language always a source of power. I have always been impressed with that opening phrase: in the beginning was the word.

Oriana:

Speaking about the power of words: words can kill and words can heal. And if you live long enough, you're almost sure to hear something that nearly kills you, and then, if you are lucky, you'll hear the antidote.

For me it was the statement, "Perhaps the talent is just not there," which I translated as "You have no talent." And after three miserable years I met someone who said, "Your letters were a revelation to me: you have talent."

*

MAKING NEW YEAR RESOLUTIONS COULD BE BAD FOR YOUR MENTAL HEALTH

~ While setting New Year’s resolutions may seem like a positive step toward making these changes, they can actually put unnecessary pressure on you to make and stick to them. And failing to keep these resolutions can be damaging to your mental health, leading to feelings of guilt, disappointment, and depression.

New Year’s resolutions can be particularly harmful for those recovering from eating disorders, such as anorexia, binge eating, or bulimia. I’ve found that many patients in recovery overemphasize resolutions related to healthy eating behaviors and that this practice can be counterproductive to the recovery process. Instead, a more beneficial approach is that of radical acceptance.

I’m sure you probably can’t even count how many times you’ve heard the phrase, New year, New you, in your lifetime. It can be hard not to internalize messaging that implies you aren’t good enough the way you are, so you must make improvements—whether it’s related to body size or shape, exercise habits, or eating patterns. Moreover, you may find it difficult to avoid exposure to this type of rhetoric, as gyms begin trying to sell memberships and “health” companies push diets and cleanses.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Once you free yourself from the new year-new you mentality, you can begin to adjust your mindset to that of developing a new relationship with yourself. You don’t need to change; you only need to take this opportunity to radically accept yourself as you are, for all your strengths and weaknesses, accomplishments and mistakes.

Here are some tips for learning to radically accept yourself in the new year:

Practice self-compassion: This means that you accept slipups, or returns to disordered eating, with compassion, kindness, and forgiveness. You acknowledge that recovery is a lifelong process and that you are human, capable of making mistakes.

Move away from goal-oriented behavior: New Year’s resolutions put unnecessary pressure on you to make changes and seek perfection. Instead, instill mindfulness and joy into everything you do: Engage in movement that provides you with pleasure, eat intuitively by listening to your body’s cues, and practice gratitude for delicious meals.

Recognize what you can and cannot control: Let go of things beyond your control, and focus on what you can control, such as how you react to stressors, negative emotions, or relapses.

Practice journaling: Journaling can be a great way to reflect on your experiences, emotions, and behaviors, as well as to process unwanted or complicated emotions, particularly those related to disordered eating or other mental health issues.

Forgive yourself: Nothing good comes from holding onto your regrets. Recognize and accept your past behaviors so that you can move toward a place of healing.

Practice mindfulness: If you are in a distressing or upsetting situation, focus on what you are feeling, acknowledge those feelings, and let them exist without judgment. You can also turn your attention to your breath, to its natural rhythm and flow.

Create a list of coping statements: Compile a list of coping statements for radical acceptance that you can turn to whenever you are struggling. Having these on hand can help you react to painful situations in a mindful way.

Another tip that can help you learn to radically accept yourself is a term I coined called “choosing the loving behavior,” or CTLB. I use it a lot with my eating-disorder patients to encourage them to think of love not as a feeling, but as an action. In choosing to care for yourself and to accept who you are— what you feel, how you look, and what you struggle with—you are making the decision to behave in a loving, nourishing way. Even if you feel disdain for your body in a particular moment, you can acknowledge that negative feeling without choosing a damaging behavior.

Although it may seem difficult at first to practice radical acceptance, the benefits are undeniable. Take it slow, and don’t punish yourself if it doesn’t come naturally to you. Just as recovery takes time, so does learning to change your perspective. But once you radically accept yourself and your reality, you are able to focus on what you can control and start moving through life in a nonjudgmental way, better able to cope with painful emotions and situations. Now, doesn’t that sound so much better than a resolution to change who you are and what you do? ~

https://www.fastcompany.com/90706566/why-its-time-to-drop-the-new-year-new-you-bs-and-learn-to-accept-yourself?utm_source=pocket-newtab

*

BUT IF YOU CHOOSE TO MAKE RESOLUTIONS ANYWAY, HERE’S A NEW WAY YOU MIGHT TRY

~ We recommend an unconventional but more promising approach.

We call it the “old year’s resolution.”

It combines insights from psychologists and America’s first self-improvement guru, Benjamin Franklin, who pioneered a habit-change model that was way ahead of its time.

With the “old year” approach, perhaps you can sidestep the inevitable challenges that come with traditional New Year’s resolutions and achieve lasting, positive changes.

A PERIOD TO PRACTICE — AND FAIL

First, identify a change you want to make in your life. Do you want to eat better? Move more? Sock away more savings? Now, with Jan. 1 days away, start living according to your commitment. Track your progress. You might stumble now and then, but here’s the thing: You’re just practicing.

If you’ve ever rehearsed for a play or played scrimmages, you’ve used this kind of low-stakes practice to prepare for the real thing. Such experiences give us permission to fail.

Psychologist Carol Dweck and her colleagues have shown that when people see failure as the natural result of striving to achieve something challenging, they are more likely to persist to the goal.

However, if people perceive failure as a definitive sign that they are not capable—or even deserving—of success, failure can lead to surrender.

If you become convinced that you cannot achieve a goal, something called “learned helplessness” can result, which means you’re likely to abandon the endeavor altogether.

Many of us unintentionally set ourselves up for failure with our New Year’s resolutions. On Jan. 1, we jump right into a new lifestyle and, unsurprisingly, slip, fall, slip again – and eventually never get up.

The old year’s resolution takes the pressure off. It gives you permission to fail and even learn from failure. You can slowly build confidence, while failures become less of a big deal, since they’re all happening before the official “start date” of the resolution.

A GARDENER WEEDING ONE BED AT A TIME

Long before he became one of America’s greatest success stories, Franklin devised a method that helped him overcome life’s inevitable failures – and could help you master your old year’s resolutions.

When he was still a young man, Franklin came up with what he called his “bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection.” With charming confidence, he set out to master 13 virtues, including temperance, frugality, chastity, industry, order and humility.

In a typically Franklinian move, he applied a little strategy to his efforts, concentrating on one virtue at a time. He likened this approach to that of a gardener who “does not attempt to eradicate all the bad herbs at once, which would exceed his reach and his strength, but works on one of the beds at a time.”

In his autobiography, where he described this project in detail, Franklin did not say that he tied his project to a new year. He also did not give up when he slipped once – or more than once.

“I was surpris’d to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined; but I had the satisfaction of seeing them diminish,” Franklin wrote.

Repeated failures might discourage someone enough to abandon the endeavor altogether. But Franklin kept at it – for years. To Franklin, it was all about perspective: This effort to make himself better was a “project,” and projects take time.He made his progress visible in a book, where he recorded his slip-ups. One page – perhaps only a hypothetical example – shows 16 of them tied to “temperance” in a single week. (Instead of marking faults, we recommend recording successes in line with the work of habit expert B.J. Fogg, whose research suggests that celebrating victories helps to drive habit change.)

A BETTER AND A HAPPIER MAN

Many years later, Franklin admitted that he never was perfect, despite his best efforts. His final assessment, however, is worth remembering:

“But, on the whole, tho’ I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavor, a better and a happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it.”

Treating self-improvement as a project with no rigid time frame worked for Franklin. In fact, his scheme probably helped him succeed wildly in business, science, and politics. Importantly, he also found immense personal satisfaction in the endeavor: “This little artifice, with the blessing of God,” he wrote, was the key to “the constant felicity of his life, down to his 79th year, in which this is written.”

You can enjoy the same success Franklin did if you start on your own schedule – now, during the old year – and treat self-improvement not as a goal with a starting date but as an ongoing “project.”

It might also help to remember Franklin’s note to himself on a virtue he called, coincidentally, “Resolution”: “Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.” ~

Mary:

One thing New Year's resolutions share is the certainty they will be broken. What is missing is the act of forgiving the lapse, regarding it as one instance, not as total loss filling us with self contempt, not as reason to abandon the effort . "Failures," lapses, are normal, and can be a learning experience if accepted without condemnation, as part of a process or journey of change . In parenting and self improvement our intent, our effort, is to do our best, and coming short of our goal can be reconciled with forgiveness and acceptance rather than guilt and self loathing. We can feel disgust for our own failures like the disgust for anything putrefying and rotten, and self disgust is a dead end.

Kindness and compassion are essential in dealing with the self, and the idea of "practicing" changes you want to make is pure genius. It allows for failures and improvements both, largely by acknowledging change as a process rather than a sudden and absolute event. Every misstep doesn't mean the end, but a bump in the road, only to be expected. What progress we make in our practicing is reason for celebration, the satisfaction Franklin, that wise experimenter, felt for his own efforts.

*

Mieczyslaw Kasprzyk:

As the great man said, “Trying is the first step to failure.”

*

Oriana: But seriously, this is my favorite statement about failing:

***

“We are born into this time and must bravely follow the path to the destined end. There is no other way. Our duty is to hold on to the lost position, without hope, without rescue, like that Roman soldier whose bones were found in front of a door in Pompeii, who, during the eruption of Vesuvius, died at his post. That is greatness. The honorable end is the one thing that can not be taken from a man.” ~ Oswald Spengler, Man and Technics: A Contribution to a Philosophy of Life

Oswald Spengler, known chiefly for his influential The Decline of the West

Oriana:

I'm definitely not an admirer of Oswald Spengler. But to do him justice, he loathed the Nazis and antisemitism. He despised Hitler, whom he described as "vulgar."

*

MIKHAIL IOSSEL: WHAT IF DEMOCRACY FAILS IN AMERICA?

~ Today (1-1-2022) is one day of the year implicitly reserved for optimism, so I'll try not to harp on the negative, all the more so that I do believe we'll soon leave the bane of Covid in the rearview mirror (yes, I do know fully vaccinated and boosted people who've had breakthrough cases, but both anecdotal evidence and the available data indicate that these cases are usually mild; and so, generally, for those acting responsibly, we're down — almost — to normal-risks-of-life levels); and as for the terrifying problem of the climate change, we…

No, sorry: I have nothing even mildly optimistic to say with regard to the looming planetary cataclysm of climate change, except to note that at this point, that fear has been overtaken in my mind by a more immediate, near-term risk of political catastrophe in America. I am a US citizen living in Canada, and if democracy fails and falls in the US, it will send tsunami-sized shock waves all through the rest of the world.

What's happening right now in America is not an ordinary battle of ideologies, not the typical violent clashes of the tectonic plates of “culture wars” — those have been par for the course throughout the country's history (and more often than not, the more pernicious ideas and more horrible cultural takes have won out; but that's a different story). Rather, what we're witnessing now is the wholesale repudiation of democracy in America, the very notion of the democratic rule, by one of the two major American political parties —and, indeed, by many tens of millions of Americans.

Half of the political spectrum in America is now controlled by a faction that is ruled not by ideology but by the raw, naked will to power and animated exclusively by an all-out sense of victimhood and unmitigated racial resentment.

That faction — the GOP — has now essentially endorsed the attempted coup of a year ago, and is now busy laying the groundwork for future cancellation of democracy. As its policy on vaccines has demonstrated, it is now a party of know-nothingism, bottomless cynicism and downright insanity.

What is to be done? (Yes, that is the title of a very boring and poorly written 19th-century novel by Nikolai Chernyshevsky, beloved by Lenin, that we — young people of my generation, at any rate — had to read in the ninth grade of Soviet high school, loathing every minute of it.) Despair is not an answer. Giving up is not a plan.

But one would need to be willfully blind and wholly heedless not to be extremely worried. ~

https://www.facebook.com/iosselm

IS A MILITARY COUP POSSIBLE IN THE UNITED STATES?

~ As the anniversary of the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol approaches, three retired U.S. generals have warned that another insurrection could occur after the 2024 presidential election and that the military could instigate it.

The generals – Paul Eaton, Antonio Taguba and Steven Anderson – made their case in a recent Washington Post op-ed. "In short: We are chilled to our bones at the thought of a coup succeeding next time," they wrote.

The real question is does everybody understand who the duly elected president is? If that is not a clear-cut understanding, that can infect the rank and file or at any level in the U.S. military.

And we saw it when 124 retired generals and admirals signed a letter contesting the 2020 election. We're concerned about that. And we're interested in seeing mitigating measures applied to make sure that our military is better prepared for a contested election, should that happen in 2024.

General Eaton:

I see it as low probability, high impact. I hesitate to put a number on it, but it's an eventuality that we need to prepare for. In the military, we do a lot of war-gaming to ferret out what might happen. You may have heard of the Transition Integrity Project that occurred about six months before the last election. We played four scenarios. And what we did not play is a U.S. military compromised — not to the degree that the United States is compromised today, as far as 39% of the Republican Party refusing to accept President Biden as president — but a compromise nonetheless. So, we advocate that that particular scenario needs to be addressed in a future war game held well in advance of 2024.

I'm a huge fan of Secretary [of Defense Lloyd] Austin, a huge fan of the team that he has put together and the uniformed military under [Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark] Milley. They're just superb. And I am confident that the best men and women in the U.S. and in our military will be outstanding. I just don't want the doubt that has compromised or infected the greater population of the United States to infect our military.

I had a conversation with somebody about my age, and we were talking about civics lessons, liberal arts education and the development of the philosophical underpinnings of the U.S. Constitution. And I believe that bears a reteach to make sure that every 18-year-old American truly understands the Constitution of the United States, how we got there, how we developed it and what our forefathers wanted us to understand years down the road. That's an important bit of education that I think that we need to readdress.

I believe that we need to war-game the possibility of a problem and what we are going to do. The fact that we were caught completely unprepared — militarily, and from a policing function — on Jan. 6 is incomprehensible to me. Civilian control of the military is sacrosanct in the U.S. and that is a position that we need to reinforce.

A component of that — unsaid — is that we all know each other very well. And if there is any doubt in the loyalty and the willingness to follow the Oath of the United States, the support and defend part of the U.S. Constitution, then those folks need to be identified and addressed in some capacity. When you talk to a squad leader, a staff sergeant, a nine-man rifle squad, he knows his men and women very, very well. ~

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/31/1068930675/us-election-coup-january-6-military-constitution

General Paul Eaton

*

BE CAREFUL HOW YOU SPEAK TO CHILDREN

~ As adults, sometimes we forget how much impact our words can have on the children in our lives. But most of us can recall things that were said to us as kids, positive or negative, that stuck with us. Some of those words may have influenced how we see ourselves our whole lives, for better or for worse.

Elyse Myers is a popular TikTok user who has a knack for storytelling. Most of her videos are funny, but one of her most recent ones has a serious—and seriously important—message for us all.

"It is no secret that as a child, and specifically as a middle schooler, I was a little bit…round," she said. "That would have been one way to describe me. Other ways that would have been more appropriate? Funny, cute, has curly hair, determined, sarcastic, witty, smart, talented, musical —so many ways to describe me, but the one thing that people loved to latch onto was the size of my body."

"Was I ashamed of that?" she asked. "No. Other people seemed to be. You would be shocked at how determined other kids and adults were at making sure that I knew that they knew that I was larger than other kids my age.”

Myers then made a statement that millions of people, especially women, can identify with:

"I was made aware of the size of my body long before I was ever taught how to love it.”

Myers is dead on. Her story about a male substitute teacher going out of his way to "save her from herself" by telling her in so many words that she should give up the idea of being a cheerleader because of her size is appalling, but unfortunately not uncommon.

"The audacity of a man to walk up to a 7th-grade girl, in front of her friends, and comment on her appearance in any way is disgusting," she said. "I met that man for one hour when I was like 11, and I am 28 and still undoing the damage that that one sentence had on my life. So if you are an adult, if you are around children—if you are around humans in any way—I want you to understand how powerful your words are. As easily as they can tear someone down, they can build someone right back up, but it's going to take a hell of a lot more work to build them up after you've torn them down.”

In reality, it's always far easier and faster to break something than to build it. In fact, research from The Gottman Institute found that in a happy, stable relationship, couples had an average of five positive interactions for every one negative one. Couples who had a smaller ratio than that were less happy, and a 1:1 ratio, meaning evenly balanced between positive and negative interactions, equaled an unhealthy relationship “teetering on the edge of divorce.”

It takes far more positive words to create a positive experience than it does negative ones to create a negative experience, which is why it's so important for us to choose our words carefully. And because children are so impressionable, what we say to them sticks.

“I was taught how to perceive my body through the eyes of other people that didn’t love me, that didn’t care about me, that thought they could just make a passing comment and move on with their life, and I carried that forever," said Myers.

"We have to teach people how to speak kindly about themselves, how to love themselves, how to see them as beautiful and worthy and more than just what they look like. If I had as much attention poured into the things that I was good at, and I cared about, and I loved, I would have been a completely different kid.” ~

https://www.upworthy.com/tik-tok-power-of-words-kids?rebelltitem=3#rebelltitem3

*

HOW DISGUST EXPLAINS EVERYTHING

~ Once you are attuned to disgust, it is everywhere. On your morning commute, you may observe a tragic smear of roadkill on the highway or shudder at the sight of a rat browsing garbage on the subway tracks. At work, you glance with suspicion at the person who neglects to wash his filthy hands after a trip to the toilet. At home, you change your child’s diaper, unclog the shower drain, empty your cat’s litter box, pop a zit, throw out the fuzzy leftovers in the fridge. If you manage to complete a single day without experiencing any form of disgust, you are either a baby or in a coma.

Disgust shapes our behavior, our technology, our relationships. It is the reason we wear deodorant, use the bathroom in private and wield forks instead of eating with our bare hands. I floss my teeth as an adult because a dentist once told me as a teenager that “Brushing your teeth without flossing is like taking a shower without removing your shoes.” (Do they teach that line in dentistry school, or did he come up with it on his own? Either way, 14 words accomplished what a decade of parental nagging hadn’t.)

Unpeel most etiquette guidelines, and you’ll find a web of disgust-avoidance techniques. Rules governing the emotion have existed in every culture at every time in history. And although the “input” of disgust — that is, what exactly is considered disgusting — varies from place to place, its “output” is narrow, with a characteristic facial expression (called the “gape face”) that includes a lowered jaw and often an extended tongue; sometimes it’s a wrinkled nose and a retraction of the upper lip (Jerry does it about once per episode of “Seinfeld”). The gape face is often accompanied by nausea and a desire to run away or otherwise gain distance from the offensive thing, as well as the urge to clean oneself.

The more you read about the history of the emotion, the more convinced you might be that disgust is the energy powering a whole host of seemingly unrelated phenomena, from our never-ending culture wars to the existence of kosher laws to 4chan to mermaids. Disgust is a bodily experience that creeps into every corner of our social lives, a piece of evolutionary hardware designed to protect our stomachs that expanded into a system for protecting our souls.

Darwin was the first modern observer to drop a pebble into the scummy pond of disgust studies. In “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals,” he describes a personal encounter that took place in Tierra del Fuego, where Darwin was dining on a portion of cold preserved meat at a campsite. As he ate, a “naked savage” came over and poked Darwin’s meat with a finger, showing “utter disgust at its softness.” Darwin, in turn, was disgusted at having his snack fingered by a stranger.

Darwin inferred that the other man was repelled by the unusual texture of the meat, but he was less confident about the origins of his own response. The hands of the “savage,” after all, did not appear to be dirty. What was it about the poking that rendered Darwin’s food inedible? Was it the man’s nakedness? His foreignness? And why, Darwin wondered — moving on to a remembered scenario — was the sight of soup smeared in a man’s beard disgusting, even though there was “of course nothing disgusting in the soup itself”?

Kolnai was the first to arrive at a number of insights that are now commonly accepted in the field. He pointed to the paradox that disgusting things often hold a “curious enticement” — think of the Q-tip you inspect after withdrawing it from a waxy ear canal, or the existence of reality-TV shows about plastic surgery, or “Fear Factor.” He identified the senses of smell, taste, sight and touch as the primary sites of entry and pointed out that hearing isn’t a strong vector for disgust. “One would search in vain for any even approximately equivalent parallel in the aural sphere to something like a putrid smell, the feel of a flabby body or of a belly ripped open.”

For Kolnai, the exemplary disgust object was the decomposing corpse, which illustrated to him that disgust originated not in the fact of decay but the process of it. Think of the difference between a corpse and a skeleton. Although both present evidence that death has occurred, a corpse is disgusting where a skeleton is, at worst, highly spooky. (Hamlet wouldn’t pick up a jester’s rotting head and talk to it.) Kolnai argued that the difference had to do with the dynamic nature of a decomposing corpse: the fact that it changed color and form, produced a shifting array of odors and in other ways suggested the presence of life within death.

Angyal argued that disgust wasn’t strictly sensory. We might experience colors and sounds and tastes and odors as unpleasant, but they could never be disgusting on their own. As an illustration, he related a story about walking through a field and passing a shack from which a pungent smell, which he took for that of a decaying animal, pierced his nostrils. His first reaction was intense disgust. In the next moment, he discovered that he had made a mistake, and the smell was actually glue. “The feeling of disgust immediately disappeared, and the odor now seemed quite agreeable,” he wrote, “probably because of some rather pleasant associations with carpentry.” Of course, glue back then probably did come from dead animals, but the affront had been neutralized by nothing more than Angyal’s shifting mental associations.

Disgust, Angyal contended, wasn’t merely smelling a bad smell; it was a visceral fear of being soiled by the smell. The closer the contact, the stronger the reaction.

*

Paul Rozin’s interest in disgust, he said, started with meat. Although he is now pescatarian “with some exceptions” (bacon), he was still a full-spectrum omnivore when he started puzzling over meat. Despite being one of the world’s favorite food categories — both nutritionally complete and widely considered tasty — meat is also the most tabooed food across many cultures. Rozin wasn’t interested in the health implications of meat or in its economic or environmental significance. That stuff had been studied. What he zeroed in on was a kind of affective negativity around meat. When people disliked it, they really disliked it. A rotten cut of beef evoked an entirely different reaction than a rotten apple. Why? Or rather, what? What was the difference between accidentally biting into a moldy Granny Smith and a moldy steak? A bad apple might be icky and distasteful, but befouled meat caused a related, but totally distinct, sensation cluster of contamination, queasiness and defilement.

It was the Angyal paper that really got Rozin’s neurons firing, and on its foundation he began to construct the theory that would go on to inform — and this is no exaggeration — every subsequent attempt at defining and understanding disgust over the following decades. In Rozin’s view, the emotion was all about food. It began with the fact that humans have immense dietary flexibility. Unlike koalas, who eat almost nothing but eucalyptus leaves, humans must gaze at a vast range of eating options and figure out what to put in our mouths. (The phrase “omnivore’s dilemma” is one of Rozin’s many coinages. Michael Pollan later borrowed it.) Disgust, he argued, evolved as one of the great determinants of what to eat: If a person had zero sense of disgust, she would probably eat something gross and die.

On the other hand, if a person was too easily disgusted, she would probably fail to consume enough calories and would also die. It was best to be somewhere in the middle, approaching food with a healthful blend of neophobia (fear of the new) and neophilia (love of the new). It was Rozin’s contention that all forms of disgust grew from our revulsion at the prospect of ingesting substances that we shouldn’t, like worms or feces.

The focus on food makes intuitive sense. After all, we register disgust in the form of nausea or vomiting — nausea being the body’s cue to stop eating and vomiting our way of hitting the “undo” button on whatever we just ate. But if disgust were solely a biological phenomenon, it would look the same across all cultures, and it does not. Nor does it explain why we experience disgust when confronted with topics like bestiality or incest, or the smell of a stinky armpit, or the idea of being submerged in a pit of cockroaches. None of these have anything to do with food. Rozin’s next project was to figure out what linked all of these disgust elicitors. What could they possibly have in common that caused a unified response?

In 1986, Rozin and two colleagues published a landmark paper called “Operation of the Laws of Sympathetic Magic in Disgust and Other Domains,” which argued that the emotion was a more complicated phenomenon than Darwin or the Hungarians or even Rozin himself had ventured. The paper was based on a series of simple but illuminating experiments. In one, a participant was invited to sit at a table in a tidy lab room. The experimenter, seated next to the participant, unwrapped brand-new disposable cups and placed them in front of the subject. The experimenter then opened a new carton of juice and poured a bit into the two cups. The participant was asked to sip from each cup. So far, so good. Next, the experimenter produced a tray with a sterilized dead cockroach in a plastic cup. “Now I’m going to take this sterilized, dead cockroach, it’s perfectly safe, and drop it in this juice glass,” the experimenter told the participant. The roach was dropped into one cup of juice, stirred with a forceps and then removed. As a control, the experimenter did the same with a piece of plastic, dipping it into the other cup. Now the participants were asked which cup they’d rather sip from. The results were overwhelming (and, frankly, predictable): Almost nobody wanted the “roached” juice. A brief moment of contact with an offensive — but not technically harmful — object had ruined it.

In another experiment, participants were asked to eat a square of chocolate fudge presented on a paper plate. Soon after, two additional pieces of the same fudge were produced: one in the form of “a disc or muffin” and the other shaped like a “surprisingly realistic piece of dog feces.” The subjects were asked to take a bite of their preferred piece. Again, nearly no one wanted the aversive stimuli, which is how psychologists refer to “nasty stuff.” (When asked about the outliers who opted for the nasty stuff, Rozin waved a hand and said, “There’s always a macho person.”)

Until this point, sympathetic magic had been a term psychologists used to account for magical belief systems in traditional cultures, such as hunter-gatherer societies. Sympathetic magic features a handful of iron laws. One is the law of contagion, or “Once in contact, always in contact.” The sterilized roach juice demonstrated this law; if you stuck the “roached” juice in a freezer and offered it to participants a year later, they still wouldn’t drink it. A second is the law of similarity, or “Things that appear similar are similar. Appearance equals reality.” That would be the dog-doo fudge.

Both the reality-puncturing and social elements of disgust make it ripe for comedy. Take this monologue from a 1995 “Seinfeld” episode:

Jerry: “Now, I was thinking the other day about hair — and that the weird thing about it is that people will touch other people’s hair. You will actually kiss another human being, right on the head. But, if one of those hairs should somehow be able to get out of that skull, and go off on its own, it is now the vilest, most disgusting thing that you can encounter. The same hair. People freak out. There was a hair in the egg salad!”

Relatedly, there’s no unambiguous evidence that nonhuman animals experience disgust. Distaste, yes. Dislike, yes. But the capacity to be disgusted is, as Miller put it, “human and humanizing.” Those with ultrahigh thresholds are those whom “we think of as belonging to somewhat different categories: protohuman like children, subhuman like the mad or suprahuman like saints.” The 14th-century saint Catherine of Siena is famous for drinking the pus of a woman’s open sore in an act of holy self-abasement.

The theorist Sianne Ngai has written about disgust as a social feeling. A person in the thick of it will often want her experience confirmed by other people. (As in: “Oh, my God, this cheese smells disgusting. Here, smell it.”) More recently, researchers have shown that disgust is an accurate predictor of political orientation, with conservatives displaying a far higher disgust response than liberals. In a 2014 study, participants were shown a range of images — some disgusting, some not — while having their brain responses monitored. With great success, researchers could predict a person’s political orientation based on analysis of this f.M.R.I. data.

Rozin’s most famous student is Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and co-author of “The Coddling of the American Mind,” who received his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania and collaborated with Rozin on a number of papers. “I came to see him because I was studying moral psychology, and I hadn’t really thought about disgust,” Haidt told me over the phone. “But when I started reading ethnographies, I saw they almost all had purity and pollution norms. Tons of rules — about menstruation, how you handle corpses, sexual taboos, food taboos.” Western societies, he noticed, were the global exception in their lower regulation of disgust-related activities. But then, this wasn’t entirely true, Haidt realized; within America, there were plenty of groups that legislated bodily practices related to disgust, like Orthodox Jews and Catholics and, to a lesser degree, social conservatives. It was only among Western secular progressives that disgust remained somewhat lawless.

Haidt continued to zero in on the political uses of the word, noticing that Americans often listed as “disgusting” such things as racism, brutality, hypocrisy and ambulance-chasing lawyers. “Liberals say that conservatives are disgusting. Conservatives say that welfare cheaters are disgusting,” he wrote in a paper with Rozin and two others in 1997. What was that about? Was the use of “disgust” for such a wide range of activities simply a metaphoric quirk of the English language? Did the pundits who sat around all day expressing disgust on TV have to keep a vomiting bucket next to their desks, or were they just being linguistically imprecise?

Neither, exactly. When Haidt and Rozin looked at other languages, they found that many contained words with a compound meaning equivalent to “disgust” — single words that could be applied to both legislation and diarrhea. German had ekel. Japanese had ken’o. Bengali had ghenna. Hebrew had go-al. When an Israeli woman was asked what situations made her feel go-al, she cited “a horrible accident and you see body parts all over the place” and a person “who just picked his nose and ate it later.” But she also said that “If you really dislike a politician, you would use the word go-al.”

If the initial function of disgust was like a piece of caution tape plastered over our mouths, the tape had — over time — wound itself around our other holes (to regulate sexual activity) and our minds (to regulate moral activity). This potency of the emotion is such that a single anecdote can taint an entire presidential campaign. You may remember a 2019 story about how Senator Amy Klobuchar once ate a salad with a comb. According to the article, an aide purchased a salad for Klobuchar at an airport. Later, when the senator wanted to eat her salad on the plane, she discovered that there were no utensils available. After berating the aide, Klobuchar retrieved a comb from her purse and (somehow) ate her salad with it. When finished, she handed the comb to her aide with orders to clean it.

The comb story was part of a larger narrative about the senator’s treatment of her staff, which Klobuchar bravely tried to spin into evidence of her exactitude. You have to admire the effort, but the senator’s defense was useless. Nobody came away thinking that her mistake was in having high expectations. Her mistake was in doing something gross in front of multiple witnesses. That image was indelible. You couldn’t read the story without imagining the comb, a hair perhaps still caught in its teeth, plunging into an oily airport salad. Like all disgusting stories, it had a contaminating effect. Now the anecdote was in you, the voter. The taste of the comb was upon your own tongue, and you had no choice but to resent Klobuchar for putting it there.

The episode belongs to a list of disgust-related political scandals: the pubic hair on the Coke can, the stain on the blue Gap dress. On a recent weekend I passed a truck in Queens with a giant bumper sticker that said, “Any Burning or Disrespecting of the American Flag and the driver of this truck will get out and knock you the [expletive] OUT.” This was a perfect Haidt litmus test. A liberal might walk past the truck and think some version of: This guy — and it’s definitely a guy — has an anger problem. A conservative might walk past the truck and think: This guy — and it’s definitely a guy — must really love our country. As Haidt put it: “There are people for whom a flag is merely a piece of cloth, but for most people, a flag is not a piece of cloth. It has a sacred essence.” If a person views the American flag as a rectangle of fabric, it is unfathomable to be disgusted by its hypothetical desecration. If a person views the flag as a sacred symbol, it is unfathomable to not feel this way.

These two types of human — which broadly map onto “liberal” and “conservative,” or “relatively disgust-insensitive” and “relatively disgust-sensitive” — live in separate moral matrices. If it seems bizarre that disgust sensitivity and politics should be so closely correlated, it’s important to remember that disgust sensitivity is really measuring our feelings about purity and pollution. And these, in turn, contribute to our construction of moral systems, and it is our moral systems that guide our political orientations.

To ward off disgust, we enact purity rites, like rinsing the dirt from our lettuce or “canceling” a semipublic figure who posted a racist tweet when she was a teenager. We monitor the borders of mouth, body and nation. In “Mein Kampf,” Adolf Hitler described Jews as like “a maggot in a rotting body” and “a noxious bacillus.” Another category of humankind consistently deemed repulsive is women; to take one of several zillion illustrations, one reason long skirts were a dominant fashion in Western Europe for centuries, according to the fashion historian Anne Hollander, was to conceal the bottom half of the body and by extension its sexual organs.

Mermaids aren’t just a folkloric figure but the expression, Hollander argues, of a horrified disgust at the lower female anatomy, which is seen as amphibiously moist and monstrous.

My personal mother lode of benign masochism — and perhaps yours, in the near future — is the F.D.A.’s “Food Defect Levels Handbook,” which is designed for food manufacturers but is available online for anyone to browse, which I do often. It outlines the amount of disgusting matter in a given food that will trigger enforcement action — meaning that any less is just fine. Commercially produced peanut butter, the site will tell you, is allowed to contain anything fewer than 30 insect fragments and one rodent hair per 100 grams. A can of mushrooms may house fewer than 20 maggots. Fewer than a quarter of salt-cured olives in a package may be moldy. A clever entrepreneur could establish a weight-loss program entirely on the basis of alerting people to the larvae and dry rot and beetle eggs that adulterate their favorite foods. But who wants to live that way? The best bulwark against disgust — the only bulwark against so much of life’s wretchedness — is, in the end, denial.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/27/magazine/disgust-science.html?utm_source=pocket-newtab

It seems that survival is the strongest factor — we are wired to avoid obvious or possible pathogens.

*

THE PERSISTENT RELIGIOSITY OF AMERICA

~ Only a couple years ago, Franklin Graham, son of "America's Pastor," Billy Graham, declared any criticism of former president Donald Trump to be the work of demonic powers. The following year, one of the president's closest evangelical advisors, Paula White, publicly commanded "all satanic pregnancies to miscarry." Polling in recent decades indicates that around half of all Americans continue to believe that the Devil and demonic possession are very real, and though some recent numbers suggest that figure may be lower among Democrats, the percentage of Americans who believe in the Devil rose from 55 percent in 1990 to 70 percent in 2007 — as of 2018, even Catholic exorcisms appear to be on the rise.

Around half of all Americans believe the Bible should influence U.S. laws, and 68 percent of white evangelical Protestants believe the Bible should take precedence over the will of the people. In other words, if you find yourself talking to an American Christian, chances are they have been reared in the fear of making a wrong move, of choosing the wrong side, and believe that doing so could have nightmarish results in this life and the next. Chances are that fear is so deeply ingrained that it no longer registers as fear. Fear is simply the lens through which they view the world.

I was 19 and in college before I encountered a single person who challenged the doctrine I was raised in, and I've since had similar experiences in urban Virginia, rural New Hampshire, and suburban Indiana where I now live. Classifying American Christians into the imaginary phyla of cults and not-cults, of dangerous, fringy, irregular churches and a safe, mainstream, religious majority is a terrible mistake and just as dangerous as extremism itself.

In fact, religious extremism has been if not the then a national norm for the duration of my lifetime. In my experience, you only need press most Christians for a few minutes before you encounter many of the "strange and sinister" beliefs that are supposed to be a marker of cults. This is why unlearning religious extremism in America is so difficult, and often takes a lifetime — akin, I imagine, trying to be sober in a brewery.

If more than three quarters of all American evangelicals believe we are living in the End Times described in the Bible, then it is not only probable but inevitable that some of those believers will take action and remove themselves and their families from the corrupt, materialistic, Babylonian world. Likewise, if the Bible was written by the finger of God, as I was taught, then questioning it — in fact, questioning anything about the church and church leaders might render a believer vulnerable to unseen "powers and principalities" that circle above us like vultures, eager for our destruction.

In 1971, just as my father was returning from Vietnam, Billy Graham delivered a message in Dallas, Texas, called "The Devil and Demons," and in the same year, Brother Sam began preaching the End Times that were already a staple of Billy's Crusades. Both men, and many, many other preachers like Oral Roberts, Jimmy Swaggart, Pat Robertson, and Jim Bakker, all technically outside the Body, and Buddy Cobb, John Henson, and Doug McClain, all inside The Body, saw the polluted, diseased, war-torn world as proof that a Great Tribulation was fast approaching.

All taught the very biblical duality-laden concepts of demonology, of believer/nonbeliever, of us/them. And nearly all would fall from grace, charged with numerous crimes from fraud to solicitation to sexual misconduct to kidnapping, though believe me when I say that those falls never mean an end but a beginning, a new flush of pastors, rebranded, contemporized, fortified now by social media, and every bit as eager to wield fear as a weapon in the endless crusade for power.

Not every extreme form of Christianity ends with cyanide Kool-Aid in Guyana. The rapid growth and clout of QAnon is another potential outcome, proof that a legion of pastors have spent decades nudging faithful Americans in the direction of paranoia, conspiracy theories and ultimately the dismantling of a government they insist is on the wrong side. If between 15 to 20 percent of Americans believe the government is controlled by a cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles, and that an apocalyptic storm will soon sweep away the evil elites and restore "rightful leaders" to power, America's pastors are why.

Even decades after my last Body Convention, when I began working as an ER nurse, every time I was assigned a patient with hallucinations of demons or The Devil, I had to exorcise myself of the belief in them. I remember one patient in particular who had attacked her husband with a chainsaw and saw demons in the corners of the locked hospital room where I was caring for her. "There he is!" she kept whispering, pointing behind me, her eyes registering a presence there, her expression shifting dynamically from glare to terror and back to glare. I had to concentrate not to feel the presence, too, to slow my breathing and repeat to myself, "She's just sick, that's all. Just sick, like any other patient."

https://www.salon.com/2021/12/26/best-of-2021-i-grew-up-in-a-christian-commune-heres-what-i-know-about-americas-religious-beliefs/

*

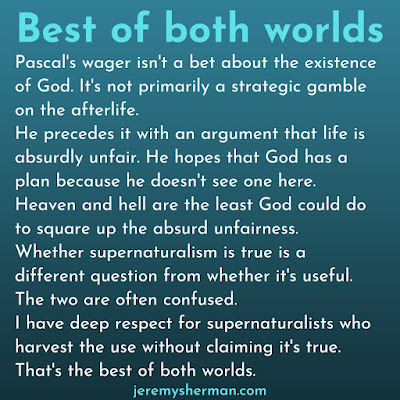

Jeremy Sherman on Pascal's Wager

I like Swedenborg's vision of the afterlife: it's a world of beautiful homes and gardens where you find yourself among kindred minds. You are also provided with the kind of work you love. How marvelous it would be to believe that this is what awaits all good people! But there is always that persistent whisper of reason telling me that this is too good to be true. In fact it's hard for me to believe that someone as intelligent as Swedenborg, a scientist, would confuse his wishful thinking with a much more likely reality.