*

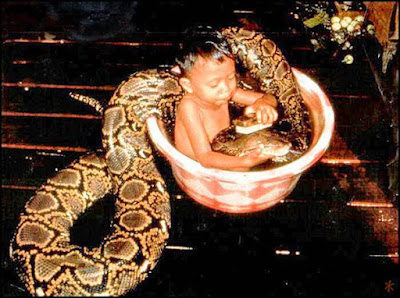

HOLDING THE PYTHON

I thought he’d hang

slack, but he flowed

through my hands,

a body made of motion —

a darkness leaning to enter

the leafwork of shadows.

I felt his colossal strength

pour itself through me,

the progressive

diamond along the center.

I had to follow,

I had to flow into earth —

liquid animal,

unending arrival —

~ Oriana

*

The poem was inspired by the actual experience of my trying to hold a python in a nature center. The trouble was that I didn’t have the muscle it took to actually hold it and restrain it from flowing through my hands and onto the ground. Then, seeing that I was just not up to it, the man (an employee of the nature center) who had draped the python around my shoulders stepped up to the task: he took the python away from me and draped it around himself. He seemed to be enjoying it. I think he was showing off, especially to the children who gathered around.

The poem started a tad longer:

HOLDING THE PYTHON AT THE VISITOR CENTER

I don’t know if his earth eyes

saw me, or just angles

of arms and back —

Yet he seemed to like

people: they were a species

of small, unsteady trees.

I thought he’d hang

slack, but he flowed

through my hands: a body

made of motion,

a darkness leaning to enter

the leafwork of shadows — (etc, etc)

I may yet restore those first tercets. It’s hard to choose — but then, it’s “only a poem.” Not that many people are going to read it. As for the future generations, no, I'm not delusional as some beginning poets are. Perhaps it's a necessary stage in any of the arts, that idea that the future generations will surely appreciate your worth.

“The visitor center” is so mundane, I feel it subtracts from the magic of the poem (which most readers like this poem — I was surprised by a recent negative reaction to it). At this point I lean to the short version, but recognize the merit of adding details that confirm the reality of this unique and unforgettable experience. I feel fortunate to have had it.

The poem brings back the experience to me: the incredible strength of the python and his fluid motion (I say “he” but of course it might have been a female — which reminds me that a priestess at Delphi was called a pythoness — another poem starts here, but it won’t be mine)

Here is Richard Avedon’s iconic image of Nastassja Kinski “dressed” in a python:

*

WHAT’S THE BEST THING IN THE WORLD?

~ In the early 1920s, Stalin and a few colleagues were relaxing in Morozovka Park, lying in the grass. One asked, “What’s the best thing in the world?” “Books,” replied one. “There’s no greater pleasure than a woman, your woman,” said another. Then Stalin said, “The sweetest thing is to devise a plan, then, being on the alert, waiting in ambush for a goo-oo-ood long time, finding out where the person is hiding. Then catch the person and take revenge!” ~

Miklos Kun, Stalin: An Unknown Portrait (cited in David Murphy’s What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa)

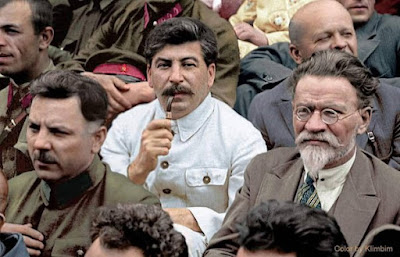

Stalin and Trotsky

Oriana:

Trotsky seems prematurely aged in this photo, and already looks like a loser. Or is it just that

we know history? And would Trotsky have been a less ruthless head of state, or would the task make him Stalin-like? Power corrupts — no one argues with that observation.

Regardless, what's the best thing in the world? It depends on the stage of one's life. I'd never believe that at this point my answer would be: being able to take long walks without pain. But aside from that, my answer would be close to "books" -- learning something new and fascinating, whether facts or ideas (and ideas change facts, and facts can change ideas).

But beauty is also enormously important to me, and kindness and affection. Those are also the "best things in the world."

Stalin had excellent military intelligence about the German plans to invade Russia. He chose to disregard it all, apparently thinking that Hitler would not be so foolish as to invade Russia. Not that Hitler was ignorant of Napoleon’s fiasco; his generals begged him not to repeat Napoleon’s mistake. But it turned out that Hitler was indeed foolish enough, and caught Stalin by surprise, his troops mostly not combat-ready.

Steven Kotkin makes the interesting case that Stalin never actually gave up on the world revolution and that Socialism in One Country was merely a strategy of defending socialism where it could be preserved until it was strong enough that it could be spread.

It is known according to the Soviet archives that into the late 1930s, Stalin believed that there would be another world war between the two capitalist world factions (the Axis and the West) and that the Soviets would be able to exploit it to, paraphrasing here, “bring about the final battle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie.” I don’t think he ever gave up on the idea, just merely made tactical retreats when he believed it was necessary. He remained a devoted communist his whole life. ~ Chris Roberts, Quora

Luke Hatherton:

One author wrote in “What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa” that because Britain was still in the war, Stalin stuck firmly to the belief that the capitalist countries would fight it out until one had achieved victory, and only then would he be in danger. I also think he went into denial about the dire situation he was in, and perhaps used this belief to help his denial.

*

WAS STALIN MENTALLY ILL?

Alla Baskakova:

He was examined by the famous psychiatrist Vladimir Bechterev. The examination took place on December 23, 1927. On December 24 the world famous neurologist and psychiatrist was dead. His family was arrested and destroyed as well. There is no records left, the legend said that Bechterev had whispered “paranoia…” when he was leaving the room where he was seen Stalin.

Niall Clugston:

US ambassador W. Averell Harriman said: “It is hard for me to reconcile the courtesy and consideration he showed me personally with the ghastly cruelty of his wholesale liquidations. Others, who did not know him personally, see only the tyrant in Stalin. I saw the other side as well – his high intelligence, that fantastic grasp of detail, his shrewdness and his surprising human sensitivity that he was capable of showing, at least in the war years. I found him better informed than Roosevelt, more realistic than Churchill, in some ways the most effective of the war leaders... I must confess that for me Stalin remains the most inscrutable and contradictory character I have known – and leave the final word to the judgment of history.”

Stalin was able to operate under immense pressure in World War Two, as the quote from Harriman indicates. He wasn’t paranoid. He knew perfectly well that the people he imprisoned or executed were innocent. Personally, he used to downplay and ridicule the personality cult that had developed around him, so he doesn’t seem to have been grandiose.

Regarding his childhood, he had an alcoholic and abusive father but had a supportive mother. At the end of his life he kept in touch with friends from his early days. He was married twice and had relationships with several other women. He was a recognized Georgian poet and very well-read.

With regard to his rebelliousness, that has to be understood within the context of the time. Tsarist Russia was falling apart, and so was the rest of Europe. Socialism was on the rise. The Bolshevik faction was more extreme, but also — as it turned out — more effective. Stalin’s involvement in robbery etc was sanctioned by the party. It was not a personality trait. Lenin only started to view Stalin as problematic at the end of his life when Stalin started to try to ride roughshod over other people. In his subsequent struggle against Trotsky and others, Stalin had the overwhelming support of his colleagues.

Up to the point where he embarked on mass murder, I don’t think there was anything to suggest that he was mentally ill. After this point, he still gained the respect of people such as Harriman, Khrushchev, and General Zhukov. He oversaw the emergence of the USSR as an industrial power. He was able to operate under the extreme pressure of World War Two and maintain cordial relations with Churchill and Roosevelt. After the war, he dealt with the emerging Cold War and the Korean War.

It is very hard to understand what Stalin was thinking. The mass murder seems utterly unnecessary. But evil and mental illness are not the same thing. There doesn’t seem to be anything in his behavior as a person to suggest he was mentally ill, as apart from criticism of his political regime. People who met him had a positive assessment of his personality. And he was obviously able to function at a high level mentally and psychologically. There doesn’t seem to be much evidence that he had a mental illness. ~

Gene Smoke:

Psychopaths are not fanged rabid animals thirsting for blood all the time. They can be very charming, they can be very gracious and generous even. But if you get in the way of what they want, if they perceive they have been slightest in the least, they can turn on a dime and become very brutal.

Julio Pino:

I will give you the judgment of two of his contemporaries. “Stalin started out as a file clerk and he is still a file clerk.” ~ Adolf Hitler. “Stalin is the best mediocrity in the Party.” ~ Leon Trotsky. Stalin, much more than Eichmann, personified the banality of evil. He contributed nothing to Marxism. His speeches and books were ghost written. He never got over his seminary school education, i.e. thinking in the manner of a catechism: “Why is the Communist Party of the Soviet Union the greatest political party in the world? The Communist Party of the Soviet Union is the greatest political party because…”. His power owed nothing to charisma or rhetoric, only a vast state machine he had inherited from Lenin and then expanded into the stratosphere.

Stalin was a mass murderer but in many ways the opposite of a sociopath. He killed in the name of a dogma. If ever there was a man who believed “If the facts don’t fit the theory, change the facts,” that man was Joseph Stalin.

Lytiek Gethers:

Stalin was ruthless, temperamentally cruel, and had a propensity for violence high even among the Bolsheviks. He lacked compassion, something Volkogonov suggested might have been accentuated by his many years in prison and exile, although he was capable of acts of kindness to strangers, even amid the Great Terror.

He was capable of self-righteous indignation, and was resentful, and vindictive, holding on to grudges for many years.

By the 1920s, he was also suspicious and conspiratorial, prone to believing that people were plotting against him and that there were vast international conspiracies behind acts of dissent.

He never attended torture sessions or executions, although Service thought Stalin "derived deep satisfaction" from degrading and humiliating people and enjoyed keeping even close associates in a state of "unrelieved fear.”

*

Oriana:

One thing we need to remember about Stalin is that he was a devout communist, and a workaholic. Historians such as Stephen Kotkin seem to agree that Stalin didn’t just cynically use the Marxist ideology to further his power; Stalin appeared to be a true believer. Kotkin goes as far as to call him an idealist.

Surprisingly, he also loved to read books of all sorts, including novels. He remains a puzzle because he was a real person with various contradictory traits.

Let’s not forget that he started out as a seminary student.

Mary:

*

THE FAILURE OF “MARXISM-LENINISM” EVERYWHERE IT HAS BEEN TRIED

~ Having been born in Soviet Estonia in 1972, with half of the family repressed and the other half with blood on their hands I share the dim view of Communism. Of course USSR was not communist, not even socialist. Communism in Soviet Russia (like in every other socialist experiment the history knows, from Cambodia to Venezuela) died in early 20s, simply because its unsuitability for running the society became absolutely clear for everyone with some brains. Everything that followed was just country run by bureaucracy and bunch of paranoid leaders for whom no crime was too big to retain their power. Millions died. For almost half a century world was divided in half, just a push of a button away from nuclear war.

Communism does not work. They tried in earnest in Russia, half of Europe, China, Vietnam, Cuba, Cambodia, Nicaragua, Venezuela. I am quite sure all of these experiments started with the best intentions. Well, road to hell is paved with the best intentions. They all ended in ruin and misery - and not because of bad capitalists but because it did not work out. The system is flawed, the ideology is flawed. All the attempts to make it work have ended up in violence - the more earnestly communists try to make it work, the more people die. USSR actually became a lot safer place to live in when in 60s nobody gave a damn about the ideology anymore, except for show and propaganda. Those of us who have seen these experiments from inside understand why they did not work.

Communism has been often compared with Nazis and that is a fair comparison if you consider the amount of victims. There’s a difference, though. You see, Dima [Vorobiev, former Soviet propagandist] and his colleagues did much, much better work than certain Mr Goebbels. It was not just about producing news items. It was about producing and doctoring most of the data available. Of course, Soviet statistics did not produce any meaningful numbers anyway, lies started from the enterprise level, those lies were added together on regional level, then oblast and republic level and because everyone understood well that whatever result they got up there had no contact with reality whatsoever, they were then doctored on USSR level to say exactly what was necessary at that point in time. The system was built in such a way that lies were inevitable.

~ Vahur Lokk, Quora

Joseph Milosch: BOTH COMMUNISM AND CAPITALISM ARE FORMS OF CAPITALISM

The discussion of which economic system is successful: communism or free market, is a red herring. Both are a form of capitalism, and their weakness is that wealth ends up in the hands of a few. Communism is a venture financed by the government, while in America, theoretically, an individual funds the enterprise. Every economist knows that over time capitalism puts economic power into the hands of a few. Today, a few individuals control the American economy. They hide behind a corporation, but everyone knows the Kochs, the Waltons, the Fords, and others are the power behind the system, which we call corporate or global capitalism.

As in the Western economies, the economic disappointment with communism is another example of the failure of capitalism. The American taxpayer has bailed out every sector in the last forty years. When Trump imposed tariffs on China, he needed to bail out the corporate farmers of America. Under Republican leadership, the taxpayer continues to subsidize hospitals, banks, manufacturers, and utility companies. If American capitalism is so good, why do citizens fund corporations?

For years, the coal industry has blamed environmental laws for its inability to earn profits and hire more miners. Trump rescinded many of those laws, and the coal industry put five hundred people to work. No one mentioned that the coal companies became unprofitable when they broke the unions. The profitability depended not on the wage and benefit package but enforcement of the industry safety requirements.

In the eighties and nineties, the non-union mines caved in almost monthly. The industry claimed it was too expensive to safely re-open the mines. Yet the coal corporations still received federal subsidies. Because of their mismanagement, the US coal industry failed to fulfill its Asian contracts, and its business went to China. They did not outcompete the United States with their efficiency. The American mines closed due to greed-driven mining practices.

Why do people refuse to complain about the corporations deciding that short-term profits are more important than sustainability? In China, the government forbids citizens from criticizing the economic policy. American corporations restrict criticism of their economic power. If you do, you are labeled a socialist, a communist, or, worse, a Democrat. Let us look at the price of gas. The press and the people criticize Biden for doing little to prevent high gas prices. Economists agree that the president could lower the cost of fuel by as much as seventy-five cents per gallon. That is the same amount that the gas prices should have increased because of the War in Ukraine.

Few in Congress or the press complain about the gas industry overcharging. It is rare for a politician to suggest taking millions in subsidies away from the fossil fuel sector and returning it to the people. Oil companies state that high prices result from COVID, The Eastern European conflict, and a shortage of refineries. Yet oil companies made billions during the epidemic. Since the invasion of Ukraine, oil companies are making record profits. According to an oil company spokesman, the industry reduced the number of refineries because Americans will use less gas twenty years from today. Today, the West lives better because we live in the transition zone from a non-corporate to a corporate economy

Oriana: "COMMUNISM" AS STATE CAPITALISM

Many years ago someone told me that communism doesn’t exist anywhere in the world: it’s state capitalism.

What makes sense to me is that a mixed system is best: a well regulated capitalism, with unionized employees.

I'm also reminded of what Misha Iossel once wrote: "The Soviet Union was not a communist state. It was a fascist state."

*

WHAT WOULD STALIN THINK OF PUTIN? (Dima Vorobiev)

~ Stalin would have Putin immediately executed. A swift show trial would roll out a long list of charges among which five items would certainly be very prominent:

1) Deserting the cause of defending Soviet rule against the forces of Imperialism and counter-revolution by seeking discharge from KGB in the summer 1991 and the failure to defend the achievements of Socialism at the crucial points in August 1991 and December 1991.

2) Willingly siding with the most wicked anti-Soviet forces by taking a job as a fixer for one of the most prominent anti-Communist politicians of the 1990s, Anatoly Sobchak.

3) Succumbing to the bourgeois mindset by amassing great wealth and indulging bourgeois lifestyle.

Strengthening the deadly grip of exploitative classes over the working masses of the former Soviet Union as President of Capitalist Russia.

Helping the forces of Imperialism and economic exploitation in the international arena.

**

Tone:

Siding with and promoting the Russian Orthodox Church.

The early Soviets despised the church with its links to the Romanovs and the bourgeoisie.

Daniel Vianna:

Well that was too easy. Were Putin an outstanding defender of the Communist cause, he would still be assigned the same fate. Stalin didn’t tolerate competitors.

Dima:

[Here’s what Stalin would think of Putin]: “A competent man, experienced politician, dangerous enemy. We better shoot him right away”.

Vijay Duraiswamy:

Knowing Stalin, he would have purged all Soviet presidents post WW2.

Austin Neece:

Isn't there a Russian joke that goes something like “if Putin met Stalin, Stalin would say ‘Kill all of your political opponents and paint the Kremlin blue’.’Why blue?’ ‘I knew you wouldn’t question the first part.’”

**

Blackboard in one of the Kharkiv schools. The last entry on it is dated February 23rd. Topic for study: The Black Sea. The following day Russia attacked Ukraine.

The stolen childhood of Ukrainian children. Photo: Pavlo Guk.

*

CAN PUTIN STOP RUSSIA’S DE-INDUSTRIALIZATION AND BRAIN DRAIN? (Dima Vorobiev)

Stopping de-industrialization and brain drain from Russia is not feasible for President Putin.

The main unavoidable obstacle is the catastrophic shortage of workforce.

Unemployment in Russia stays under 5%. We need to import hundreds of thousands of guest workers from Central Asia and Ukraine. Among the natives, industrial work is considered low-status, slightly above living on the dole, and often not even that. Among high school and college graduates, “everyone” set their sights on high-paying jobs in the petroleum and banking sector, or the safe and cushy chairs in the State.

Russia depleted the countryside for the available workforce almost half a century ago. Creation of many new labor-intensive industrial businesses in a country like this requires two things:

A major crisis that causes the State to shed hundreds of thousands of prospective workers who are now employed as public servants and in the military.

An ambitious nationwide re-training program that capitalizes on the generally high education level of our population and teaches them the skills necessary for industrial jobs.

President Putin will do whatever it takes to prevent No. 1, and there’s no way he blows his war chest on No. 2. Below, a projection of our available workforce for the rest of the century.

John Todd Gray:

Would you be concerned that immigration from China could eventually cause a loss of territory to China?

Dima:

Not really. Our place is too cold, poor and boring for them.

Igor Routine:

Russia needs a high-tech industry, which can be highly profitable, as American experience shows, highly paid, prestigious, and requires Russian college graduates and not an unskilled mass from Central Asia. Due to the Russian traditionally strong math, informatics, and physics, and the hundreds of thousands of Russians trained in the West, that would be very realistic to achieve, except that the resource-selling oligarchs in power are not interested in investing. The existing system puts stop to any development. Stalin 1931

Stalin 1931

PUTINISM IS NOT FASCISM (Dima Vorobiev)

Putinism differs from fascism in three essential ways:

Conservatism

Classical Fascism and Nazism were revolutionary far-right ideologies. They marked a populistic break with old aristocratic societies under the banner of nationalist revival, communitarian justice, and equality.

Putinism is allergic to anything revolutionary. Even reforms became a dirty word during the last decade of Putin’s presidency.

There’s no place for far-right vigilantism in Russia. If you can gather on your own a hundred thousand for a loyalist rally in downtown Moscow today, who can guarantee you all won’t march on the Kremlin tomorrow? Therefore, stay put, shut up, and Instagram your cat’s frolics.

Elitism

Classical Fascism, just like its Marxist counterpart, is populist. It preaches brotherhood and equality within the Fascist nation. It promises to destroy the rigid hierarchical orders of the old — if you selflessly serve Führer or Duce

Russia is elitist as it gets. For anyone who’s someone, conspicuous consumption is a must. The distance between our ochlophobic [crowd-fearing] President with his retinue and the man in the street is cosmic.

Rallying against the oligarchs and the appalling contrast between the charmed life of the “best 100,000 families” and the plight of millions of commoners is ”extremism”. Preaching class struggle and expropriation of the usurers and exploiters assures you a prison sentence for “inciting hatred against particular social groups”.

Non-ideology

Fascism is a totalitarian ideology. It permeates the whole society, controlling the lives of its subjects both in public space and at home. It insists on you loving it from the bottom of your heart. It puts enormous effort into chiseling the tiniest details of its theoretical foundation.

Putinism is non-ideological. The only requirement it has his loyalty to the Kremlin, no matter what. Little wonder that even Russian gangsters support our President. In his new release of the old Russian Estates of the realm, there’s a place for any group—Communists, Fascists, Muslims, atheists—who support him and his system.

Putinism is devoid of any coherent ideology beyond teaching the rest of the world a lesson not to mess with the Kremlin. For all its defiance, Fascism is the opposite of this. As with any totalitarianism, Fascism offers a clear vision of the future and a well-shaped ideology of radical change.

The dichotomy between Moscow and impoverished regions is another pain point of the potential civil war.

Jaime Torres Molinos:

Regarding point 1:

Conservatism is also right wing, far right is not necessarily revolutionary. The more defining feature to me is hyper-nationalism. Putin definitely seems to have consummated that one when he said there are Russians and then there are Russians who are not Russians and Russia will spit them out. In other words, if you are not a Putin patriot, you are not even a real Russian according to him.

Regarding point 3:

Hyper-nationalism is in fact an ideology. Russia is not totalitarian at this point, but there is already severe interference in ordinary people’s lives, like cutting off Facebook, for example and then all the consequences of this war, foreign companies leaving, massive inflation, travel bans, banning words (!), military draft (!) etc. At a certain point the actions of the government do have a totalitarian type effect on people when their life changes drastically. Currently Russia is not militarized like fascism was, but at what point do you call authoritarian totalitarian? If I was in Russia now, I would definitely feel like it’s totalitarian.

As a matter of fact, fascists were fascists even before they managed to fully consolidate fascism in their respective countries. Neither did they, nor did others wait to call them fascists until they actually made everything they wanted happen.

Also you did not list the similarities, especially the perhaps most famous “liberalism is obsolete” which Putin said a few years ago. Many quotes by Mussolini seem to perfectly align with Putin’s thinking also.

Dima:

But Mussolini was the opposite of Conservatism, just like Xi. “Futurism” sits perfectly on both, albeit in deeply nationalistic garbs. Meanwhile, Putinism is all in the past, part Alexander III, part Andropov.

Richard Watson: PUTIN IS NOT A HITLER BUT A CAESAR

Putinism is a cult of personality linked with nationalism, devoid of ideology. Similar to Caesar.

Caesar & Augustus conflated themselves as Rome and without them all would fall to ruin. Putin has conflated himself in the minds of Russians as Russia, without him all falls to ruin. The Caesars had no ideology but themselves and Rome. Thus Putin is not a Hitler but a Caesar.

*

UKRAINE AS PUTIN’S OUTSOURCED STRUGGLE AGAINST LIBERAL VALUES

~ Soldiers and officers refuse to go die or lose limbs in Ukraine. They believe there’s a meat grinder over there, and they are not meant to come back so they wouldn’t tell the truth about the so-calle*d special military operation.

And the truth, they believe, is that Putin is a western stooge, and in cahoots with Biden and Zelensky pitted Russia against Ukraine in order to make it fall apart again so that America can have both countries.

Nobody dares to say the name of Putin aloud. He’s become a cross of a tsar and demon. A semi-divine entity who does not divulge to simple mortals his plans and grand strategies.

But nobody is eager to sacrifice his life to this celestial entity. Putin is running out of cannon fodder and has ordered formations of ethnic battalions to kill Ukrainians.

A Tatar battalion rides T62 museum exhibits waving Bashkortostan flag. A Chechen battalion with conscriptions under gun point head to Donbas. An Ossetian battalion with another museum exhibit suddenly dreams of freedom.

War in Ukraine is an outsourced liberal revolution. Putin rules the silent majority, but it is passive, while the liberal minority has been active and gets assistance from the west. In case of victory, their ultimate prize is presiding upon the return to business as usual with the West.

And what Putin did, although unconsciously, he outsourced that struggle against liberal values he’s been waging, to Ukraine.

Yet, that civil war exported to Ukraine, is not going to stay behind the border.

Eventually, following a war of attrition, it will bounce back to bring Russia into a violent confrontation when brothers will fight brothers, the pro war and against war camps. And ethnic minorities will rebel against central authorities and insist they don’t want to pay taxes to Moscow.

Autocracy and democracy will clash, ardent believers in values that stand at opposite ends.

Russians live in denial, oblivious to the fact that they are rushing towards the edge of the abyss.

Moscow is a country of its own: wealthy and bourgeois. Salaries are up to 10 higher than in the regions. They are not asked to fight wars. They have the best healthcare and services and infrastructure.

For now, Russians think the crises will blow itself out, and eventually they return to some sort of normality.

Their glum faces will stay glum. Inside though they will have a small jubilation for having outlived the tsar who thought he was Peter the Great but turned out to be Nicholas the Second.

A new tsar will ascend and make more promises he’s not going to keep. In Russia, glum faces and tsars are like American apple pie and pickup trucks. ~ Misha Firer, Quora

*

M. Marcus Harrison:

Revolution? That's only possible when the officer corps of those returning ethnic troops is with them, and part of them. But the majority of officers will be ethnic Russians I'm sure.

Individual, discharged, weaponless ex-soldiers are not much of a threat to anyone, except their wives.

Alan Taylor:

Well done, Misha. Your observation that Russia’s internal struggle has been “outsourced” to Ukraine and that the conflict will erupt once the SMO is concluded strikes me as particularly profound.

David Pan:

Only when the pain is felt in Moscow and St. Petersburg will things start to change.

Andrew Vashevnik:

Current war is made by old people who are still unhappy about the collapse of the Soviet Union. Time is obviously not on their side. Change will inevitably come but we need to wait a little bit.

I think that Russia’s potential is enormous: very good education (especially in STEM) and a lot of natural resources.

I am optimistic about potential change. Stalin’s personal cult was denounced in 1956, but USSR collapse happened only 35 years later. Change of generations was needed — next step forward was possible only for people who had no experience working under Stalin.

Now we are heading to 1991 + 35 years. People who worked in USSR are getting old and are retiring. New generation will be much better. But it very unfortunate that generation which was sad about USSR collapse decided to go on the offensive rather than peacefully retire.

*

VLADIMIR SOROKIN: I UNDERESTIMATED THE POWER OF PUTIN'S MADNESS

~ I quote his recent claim that Russians themselves are to blame for the war. Is that fair, I ask. After all, you could argue Putin took the whole country hostage, gradually turning a makeshift democracy into a dictatorship. Aren’t you blaming the victims?

“Clever people have had 20 years to figure out who Putin is,” he says. During the early years of his presidency, oil prices rose, living standards improved and people turned a blind eye to his autocratic excesses. “They wallowed in luxury,” Sorokin says. “They traded their conscience for material wellbeing. And now they’re reaping the reward.”

On the subject of Putin, a man he describes as the “great destroyer”, Sorokin is now really hitting his stride. “He has ruined everything he’s touched,” he says — not only Russia’s free press and democratic parliament but its economy and even its army. “He claims he’s lifted Russia from its knees, but really he’s just destroyed it,” he says.

Sorokin has a point when it comes to the army: western experts have been surprised by its poor performance in Ukraine. But he himself never had any illusions. In one short story, “Purple Swans”, Russia is plunged into an existential crisis after all the uranium in its nuclear warheads turns to sugar.

The implication: Russian power is just a Potemkin village. Maybe, Sorokin suggests, Putin doesn’t even aspire to victory in Ukraine. He repeats Salvador Dalí’s famous line about Hitler unleashing the second world war “not to win, as most people think, but to lose”.

“Exactly as in Wagner’s operas, it has to end for him, the hero, as tragically as possible,” Dali wrote in 1944. I think Putin’s the same, “ Sorokin says. ~

https://www.ft.com/content/1f4bd315-7753-4e7a-be4e-0ea7e31522b9?fbclid=IwAR0ugjwXO3Mb1vrHnH6U1cB1AaGhuy5JBqQhVZpWuuTtCQGiF1ZzV06UNjE

*

TURN YOUR GARDEN INTO A CARBON SINK

~ If every one of the UK's 30 million gardeners planted one medium-sized tree and let it grow to maturity, they would store the same amount of carbon as is produced by driving 284 billion miles (457 billion km), 11 million times around the planet, research by the RHS shows [RHS = Royal Horticultural Society]. If every gardener produced 190kg of compost each year, they would save the amount of carbon produced by heating half a million homes for a year.

As governments and companies race to slash their emissions, there is increasing interest in the ability of natural landscapes, such as forests, wetlands and mangroves, to protect against the risks posed by climate change. Horticulturalists say the humble garden can also serve as a powerful tool in this fight.

"Gardens are becoming shop windows for the wider environment, demonstrating the dangers of pests and threats of climate change and showing what can be done to tackle it," says Simon Toomer, curator of living collections at Kew Gardens in the UK.

To cope with climate change, gardens must become more resilient to hotter and drier conditions in the summer and more rainfall in the winter, the RHS warns.

The ideal low-carbon garden has a wildness to it. It is packed with plants and teeming with life. The gardener in this sustainable haven is equally mindful of nurturing life below the ground as she is of tending to her flower displays and shrubs. She recycles every grass clipping, fallen leaf and broken twig within the garden and avoids toxic chemicals to boost plant growth, relying instead on home-made compost and living mulch to create a thriving habitat.

WILD LAWNS

"In the past everyone wanted a pristine lawn, but now there's a big movement in gardening for more natural landscapes which is really quite exciting," says Justin Moat, senior research leader on Kew Gardens' Nature Unlocked program, which explores nature-based solutions to climate change and food security.

"We need to put up with scruffy lawns," says Moat. This may be wishful thinking, as BBC Future revealed recently: we appear addicted to manicured lawns.

In the UK, gardeners were recently encouraged to let nature take its course during "No Mow May". Environmentalists say if left alone, lawns could become thriving wildlife hotspots. Given that an estimated 23% of urban land is covered by lawns, there is great potential for them to help fight the global biodiversity crisis.

Leaving the lawn mower in the shed also benefits the climate. One of the most important things gardeners can do in the short-term is reduce their energy consumption, from lawn mowers and sprinklers, says Toomer.

Operating a petrol lawn mower for one hour releases as much smog-forming pollution as driving for 160km (100 miles), says the California Air Resources Board (CARB).

Sally Nex, a professional gardener and author of the book How to Garden the Low Carbon Way, switched her petrol mower for a battery-powered one years ago after learning how many toxic fumes it spews out.

"There's no regulation on the maximum emissions for petrol powered tools – it's really shocking," says Nex.

Other gardening tools are just as polluting as mowers. Using a petrol-powered leaf blower produces the same amount of emissions as a 1,770km (1,100 mile) car journey – the distance from Los Angeles to Denver – according to CARB.

TRAPPING CARBON

Moat says the Nature Unlocked program has highlighted the "phenomenal" power soil has to transform our gardens into biodiverse havens that can help mitigate climate change.

"So much more is happening underground than above it," he says. "We need healthy soil for our food production and we need it to trap carbon.”

Replenishing and restoring the world's soils – both in farming and natural landscapes – could help remove up to 5.5 billion tons of CO2e every year, according to a 2020 study. That is equivalent to the annual greenhouse emissions of the US, the world's second largest polluter, in 2020.

Healthy soil offsets emissions by soaking up carbon from dead plant matter. To lock in as much carbon as possible, soil needs a good balance of water, pockets of air, living organisms, such as fungi, and nutrients. Gardeners maintain this balance by constantly adding organic material to their soil.

"I compare it to a carbon checking and savings account," says Andrea Basche, assistant professor at the department of agronomy and horticulture at University of Nebraska. "You need a constant input of decaying plant matter and roots into the soil checking account to feed all the living organisms.”

Gardeners shouldn't press the soil down too much or use heavy equipment when it's wet as this will cause it to become compacted, closing vital air pockets and preventing water from draining, Gush says.

If left bare and exposed to the elements, soil will degrade and its carbon stocks will deplete. Covering the bare soil with plants, such as clover, and mulches – loose coverings of biodegradeable materials – is therefore key to prevent CO2 from seeping into the atmosphere, Gush says.

A recent study by Penn State University found that cover crops were more effective at protecting corn and soybeans from pests than applying pesticides.

Mulching has transformed Nex's garden. "When I stopped digging and started mulching, I realized my topsoil was getting deeper and deeper," she says. "The soil is black and teeming with life – it's very rewarding.”

Mulching also suppresses weeds, helps soil retain moisture and protects plant roots from extreme temperatures.

Fallen leaves and broken twigs don't need to be removed from flower beds but can be treated as "living mulches", which are contributing vital nutrients to the soil. "Essentially leave any organic matter to feed into the soil," says Toam.

Living mulches can also reduce gardeners' reliance on nitrogen fertilizers, many of which have a high carbon footprint. Basche says farmers in Nebraska are having to use less fertilizer on their crops after growing a cover crop and using living mulches for several years. Legumes, such as beans and peas, act as a green manure by adding valuable nitrogen – vital for plant growth – to the soil when they decompose. Introducing a legume crop for one year at a cereal farm in Scotland could reduce the amount of nitrogen fertilizer needed over the entire five-year cycle by almost 50%, according to a 2021 study.

An easy way to enrich your soil is by adding homemade compost. Healthy compost should contain a 50:50 mix of materials that are rich in nitrogen, such as grass clippings and vegetable peels, and carbon, such as woody stems and paper towels.

Composting also allows you to discard any leftover food in a sustainable way. When dumped into landfill without oxygen, food waste rots and releases methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas which, although shorter-lived in the atmosphere, has a global warming impact 84 times higher than carbon dioxide (CO2) over a 20-year period.

But on a compost heap, exposed to oxygen, organic waste is converted into stable soil carbon, while retaining the water and nutrients of the original matter. Food which is composted releases just 14% the greenhouse gases of food that is thrown away.

"I dispose of all my garden waste, vegetables and peelings in the garden. Every time I harvest vegetables or prune roses, I'm removing carbon from the garden, so it's important to return that carbon to the soil," says Nex.

Compost heaps must be turned regularly – the RHS recommends once a month – to add air to the biomass and keep it moist. Garden compost can take up to two years to reach maturity, when it turns a dark brown color, has a crumbly texture and smells like damp woodland.

If you plan on buying compost, avoid one containing peat, says Gush. Peatlands cover just 3% of the planet's surface, but store twice as much carbon as all the world's forests. They lock in carbon over thousands of years, with 1cm of peat forming roughly every 10 years.

"Peat bogs are very important sinks, they have accumulated carbon over millennia," says Gush. "As soon as they are drained and the peat is exposed to the air, carbon is unlocked and released back into the atmosphere.”

The UK government said last year it plans to ban the sale of peat compost to gardeners by 2024, but critics warn that the two-year delay will add more than 1.5 million tons of CO2 to the atmosphere – the equivalent of the annual emissions of 214,000 UK residents.

PLANT ABUNDANCE AND DIVERSITY

While some gardeners might desire a uniform look for their flower beds and lawns, growing a wide range of plants is beneficial if you are looking to transform your garden into a miniature carbon sink.

Plant diversity has been shown to increase productivity and the amount of carbon stored in the soil. "Increased plant diversity boosts carbon sequestration by optimizing use of available space in a garden, both above-ground and below-ground," says Gush.

It's important to grow layer plants in your garden and grow crops with roots that will reach different depths so that they can penetrate all parts of the soil and spread nutrients around. "This facilitates maximum carbon drawdown," says Gush.

For those on a mission to transform their gardens into a carbon sink, growing long-lived trees seems like the most obvious option. To make your garden climate-resilient, the RHS recommends planting a mix of drought-tolerant trees, such as snow gum and holm oak, and ones that can withstand waterlogging, such as red maple and golden willow.

But trees are far from the only plants that can help offset your garden's carbon footprint. Native grasses have extensive root systems – reaching more than 2ft into the ground – and act as reservoirs for carbon, which transfers into the soil when the roots die and decompose.

Woody shrubs, such as spindle and sweet briar and herbs like rosemary and thyme, can help boost your garden's carbon stocks, Nex recommends in her book.

If you're set on sprucing up your garden with colorful crops, it's best to steer clear of annual flowers which need to be dug up every year – releasing locked-in carbon in the process – and opt for hardy perennials instead, such as peonies and sunflowers, says Nex.

Planting hedges is another worthwhile investment. A well-grown hedge, rich in biomass, helps suck carbon out of the atmosphere and into plants and soil. One study found that hedgerows store similar amounts of carbon to woodland. Hedges also harbor rich biodiversity and are teeming with wildlife. A British ecologist who monitored an old hedgerow near his home in Devon counted a remarkable 2,070 species, ranging from pollinators to lizards and mammals, visiting or residing there.

Gardeners who adopt low-carbon practices will be rewarded with thriving biodiversity and borders brimming with lush plants.

"My plants now grow so much better. It's very flattering to me as I'm not doing very much!" says Nex. "It has really improved the appearance of my garden – it's quite breath-taking actually.”

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220610-how-to-turn-your-garden-into-a-carbon-sink

HOW TO REVOLUTIONIZE CHILD CARE

~ In her new book, Parent Nation, Suskind says millions of kids in America are getting left behind during their first three years of life — years that a heap of scientific evidence says are crucial to their brain development. To fix that, she argues, America needs much stronger policies to support parents and caregivers at this early stage. Kindergarten — even pre-K — might well be too late.

"We've got this powerful brain science that is just so clear," Suskind says. "Yet we have a society that is built in absolute diametric opposition to supporting children, supporting families and caregivers in putting this into action.”

Suskind's path toward trying to revolutionize child care and education in America began in an operating room. A pediatric surgeon at the University of Chicago, Suskind specializes in implanting cochlear hearing devices in deaf children. This procedure gives kids the chance to hear for the first time in their lives.

Doing this remarkable work, Suskind began to notice a big divergence in her patients' outcomes. After the procedure, some kids learned to talk and understand spoken language with relative ease. Other kids not so much. Kids older than 3 and underprivileged kids consistently fared worse. That bothered Suskind, so she began searching for answers in neuroscience and social science for reasons why.

At the University of Chicago, Suskind audited a course on child development, where she was introduced to a growing body of research that helped explain the disparities she saw. For Suskind, one study, in particular, struck a chord. The study found that — before the age of 4 — kids who grow up in poverty hear a staggering 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers. The finding resonated with Suskind because she saw this same socioeconomic disparity with her deaf patients — many of whom were born to hearing parents who were not fluent in sign language. That hampered those parents' ability to communicate with their kids. Suskind came to believe that the consequent effects on these kids' brain development could help explain why some of her patients struggled with spoken communication even after receiving the physical means to hear.

About a decade ago, Suskind founded a research initiative and then wrote a bestselling book that each used the term "Thirty Million Words." But in the years since, she's come to feel the slogan puts too much focus on the number of words a child hears while their brain is forming. Really, it's more complex than that. More importantly, she agrees with criticisms of the landmark study that originally found the 30 million-word gap. The study, for example, had only a small sample size (42 families) and subsequent replications found much smaller word gaps. Suskind now shies away from using the 30 million number.

Nonetheless, the general gist of the scientific evidence remains the same, and it's only gotten stronger over the last decade: roughly 85% of the physical brain is formed in the first three years of a child's life. "This is building the foundation for all thinking and learning later on," Suskind says. While the brains of older kids and adults are relatively hard to mold, babies' brains are like silly putty. To use the jargon, the brains of kids under the age of three have much more "neuroplasticity" than older kids and adults. It's why, for example, it's typically much easier for young kids to learn new languages than adults.

Suskind's core message: creating a nurturing, interactive environment for kids aged zero to 3 is vital for their development — and many kids are getting left behind during this critical period. Kindergarten — and even preschool — may be too late for interventions to try and close an opportunity gap that begins to open up at birth. She argues we need to start much earlier.

With her research organization, the TMW Center for Early Learning + Public Health at the University of Chicago, Suskind has developed strategies and curricula to help parents create a more optimal environment to nurture their kids' brains. They've done randomized controlled trials and published research showing that their strategies work.

Since launching the TMW initiative, Suskind has had a big awakening. In working with parents, often from low-income communities, she's come to recognize that there's only so much that focusing on the choices and behaviors of individual parents can do. She beats herself up a bit in her new book, calling her original focus on changing society by simply educating parents "naive." She continues to champion strategies to educate parents on brain science and give them the tools to stimulate their kids' brains. But more important, she now says, is tackling the structural forces in society that are stacked against parents.

"Despite parents wanting the best for their children, it was like barrier after barrier after barrier was being placed in front of them," Suskind says. Some of the parents who participated in the TMW initiative had to work multiple jobs and had less than an hour per day to spend with their child. Some parents got sick, lost their jobs, and their families became homeless. Others were incarcerated, depriving their kids of a two-parent household to raise and provide for them. All lacked social infrastructure to support them, like paid family leave or high-quality child care centers to take care of their kids when they had to work.

In Parent Nation, Suskind calls for new policies and a new culture "that truly values the labor and love of parents and caregivers and puts families, children, and their healthy brain development at the center.”

America, she says, is currently failing to do that. The data backs her up.

The average OECD nation spends around $14,000 a year for each toddler's care. America spends only about $500, or about less than 4% of the average. America is literally at the bottom of the list.

One in 4 American mothers returns to work within two weeks of having a baby. America is one of the only six nations in the entire world — and the only rich nation — to not have some form of national paid leave.

Around half of Americans live in "child care deserts" that lack adequate facilities to look after their kids. A study by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development finds that only 10% of America's child care centers provide high-quality care. "Child care providers are often paid less than dog walkers," Suskind says. Meanwhile, the cost of child care has risen 65% since the 1980s.

Around 11 million American kids — or about 16% of all kids nationwide — live in poverty. Children under 5 are the poorest age group in America.

With institutions like K-12 public education, America already spends billions upon billions to educate the next generation. Suskind argues we should focus more on the critical early years of kids' lives, when interventions can make a big — even the biggest — difference. Numerous studies by top economists find that, when it comes to the bang for the buck from public spending, early childhood programs have far and away the highest returns for society.

Child advocates have been arguing for greater spending on kids for decades. However, for the most part, they've lost again and again. Just this year, the expanded Child Tax Credit — a kind of "Social Security for kids" that reduced child poverty by around 30% — expired. Congress failed to renew it.

Despite America's sustained failure to invest in kids, Suskind has found some hope in the history of another demographic group of Americans. Senior citizens, not children, were once the poorest age group in America. In the early 1930s, roughly half of all seniors lived in poverty.

But then, in the mid-20th century, seniors got Social Security, Medicare and a host of other benefits. When the tide turned against the welfare state, and politicians began trying to roll back benefits, Suskind says, a powerful organization protected seniors: the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP).

The AARP is powerful, she says, for multiple reasons. It provides a collective identity to seniors for political action. It helps cement a cohesive voting bloc. And because of its structure, it has tons of resources. The AARP isn't merely a lobbying organization for seniors. It's a business. It offers a range of products that generate revenue. And, with about 38 million members, the organization has a collective buying power that entices Corporate America to offer its members special discounts. These perks incentivize more seniors to become members.

"People often joke that people join the AARP for the travel discounts and the insurance — and they stay for the community and the impact," Suskind says.

Suskind imagines a similar organization for parents, one that entices them to become members with lots of perks, creates a collective identity and a cohesive voting bloc for political action, generates revenue by selling products and services, and then uses its resources for lobbying and campaign contributions to serve parent — and child — interests.

Little kids may not be able to vote or organize, but their parents can. ~

https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2022/05/17/1098524454/the-case-for-revolutionizing-child-care-in-america

Oriana:

This is the first time I encountered the concept of “Social Security for children.” It makes so much sense!

While the assessment of Headstart program varies, quite a few studies do find long-term benefits, such as higher high school graduation rate and less poverty in adulthood. However, this article suggests that intervention needs to start even earlier. That would be my guess too: it all starts with good prenatal care.

And I'll never forget what one elementary teacher told me: children whose parents read to them at bedtime are way ahead.

*

RISING INTEREST RATES AND THE END OF ASSET ECONOMY

“Why not take the loan?” has been a pretty good summary of American wealth building and class dynamics in the past few decades. An extended period of low interest rates has translated into surging asset values. That has made the small share of Americans capable of investing in homes, farmland, stocks, bonds, commodities, art, patents, water rights, start-ups, private equity, hedge funds, and other assets breathtakingly rich, fostering astonishing levels of wealth inequality. Given low labor-force participation and sluggish wage growth, the United States has come to look like what the theorists Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings have termed an “asset economy”—in which prosperity is determined not by what you earn but by what you own.

The “why not take the loan” days are at least on hold. The Federal Reserve is hiking interest rates as it struggles to tamp down on inflation. That has pushed equities into a bear market (because corporate profits are at risk and investors are pulling back to safe assets), the housing market into a correction (because mortgages have become much more expensive), and the tech sector into free fall (as many companies are being asked to deliver profits, for once).

Financing for mergers, acquisitions, and start-ups has dried up. And the economy might be on the verge of its second recession in two years, particularly if gas prices remain high. Animal spirits and a few hundred additional basis points have erased colossal sums of paper wealth in the past half year: $2 trillion and counting in crypto, $7 trillion and counting in stocks, uncalculated sums of home equity.

Rising interest rates and spiraling inflation might be killing off our age of asset capitalism, with no more 1.05 percent loans available for anyone, not even the richest of the rich. Does this mean a new economic equilibrium going forward, one less advantageous to capital and more advantageous to labor, less favorable for high-wealth rentiers and more favorable to regular-old renters? The uncomfortable answer is no. Low interest rates helped bolster growth and employment, even if they fostered inequality. But high interest rates are not going to build a more equitable economy either.

In some ways, this financial moment resembles the one that kicked off our grand, unequal age to begin with. In the ’70s, the United States economy was characterized by high rates of inflation, strong wage growth, and falling asset prices. (Fun fact: The S&P 500 gained essentially no value during the ’70s.) Inflation ate away at the earnings of working families, while stagnant asset prices squeezed high-income households.

Then, work started to pay less and ownership to pay more. The forces cleaving labor and capital were many and complicated. The share of employees in blue-collar professions declined, as did the unionization rate, as manufacturing became automated and shifted offshore. Corporations ballooned in size, and their tax bills fell, with big players’ dominance of their respective markets becoming more absolute and the financial economy going global. The minimum wage started falling in real terms, and the government deregulated the transportation, telecommunications, and financial sectors. All of these factors suppressed wage growth while jacking up corporate profits and increasing investment returns.

Over time, wealth inequality became more pernicious to society than income inequality. The problem is not just that a chief executive at a big company makes 33 times what a surgeon makes, and a surgeon makes nine times what an elementary-school teacher makes, and an elementary-school teacher makes twice what a person working the checkout at a dollar store makes—though that is a problem. It is that the chief executive also owns all of the apartments the cashiers live in, and their suppressed wages and hefty student-loan payments mean they can barely afford to make rent. “The key element shaping inequality is no longer the employment relationship, but rather whether one is able to buy assets that appreciate at a faster rate than both inflation and wages,” Adkins, Cooper, and Konings argue in their excellent treatise, The Asset Economy. “The millennial generation is the first to experience this reality in its full force.”

This reality took on its full force amid the monetary surfeit and fiscal austerity of the Obama years. Borrowing costs had been falling since the early ’80s. When the global financial crisis hit, the Fed dropped interest rates all the way to zero and started buying up trillions of dollars of safe financial assets, spurring investors to invest. Officials at the central bank begged—in their own way—members of Congress to spend more money to help the Fed get the country out of its slump. Instead, after a skimpy initial round of stimulus during Barack Obama’s first term, politicians started shrinking the deficit.

This kind of giving-with-one-hand, taking-with-the-other policy mix helped lower the unemployment rate, though not as much as it would have if the country had deployed more stimulus. It also flushed ungodly sums of money into financial markets and corporate ledgers. With money essentially free to borrow, rich people loaded up on pieds-à-terre and index funds. Businesses bought up their rivals and soaked up their own shares. Working families hobbled along. The Fed helped the country avoid a double-dip recession, and the outcome was yawning inequality. The Mark Zuckerbergs of the world got 1.05 percent mortgages they did not even need, while everyone else got priced out of the Bay Area entirely.

At the same time, other policy forces came along to screw over many Millennials. Cities stopped building houses, causing or intensifying housing shortages and driving up rents. Millennials got locked out of the housing market for a decade, and prices had swelled by the time they were able to get in. As housing got more expensive, everything got more expensive, particularly child care. Student-loan debt soared too, yoking young people to decades of repayments.

The rise of the asset economy has not just disadvantaged the poor relative to the rich or the young relative to the old. It has also disadvantaged Black families relative to white families. Black students are more likely to have student-loan debt and more likely to owe large balances than their white counterparts, making it harder for them to save, buy homes, or start businesses. The housing bust hit Black homeowners far harder than it hit white homeowners, and relatively few Black families have benefited from the recent increase in prices. White families remain much richer than Black ones, and much more capable of passing wealth on, generation to generation.

Things started to turn around for the 99 percent during the Trump years. Wages started to tick up among low-income Americans, in part because of states and cities hiking their minimum wages. The jobless rate fell enough that the country neared full employment. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Republicans were in charge, so they decided deficit spending was fine, and Congress suffused the economy with stimulus. Families are still living off the savings from the stimulus checks and extended unemployment-insurance payments and child allowances sent out during the Trump and Biden administration.

But supply-chain problems, rising energy prices, and all that stimulus have ginned up the highest rates of inflation in four decades, forcing the Fed to hike interest rates. Once again, as in the ’70s, working families are getting sacked by rising prices as rich families watch their paper wealth go up in flames. We are in a bear market, a punishing one for the roughly half of Americans who own stock and a particularly punishing one for the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans, who own about 90 percent of all equities. Trillions of dollars of wealth have vanished this year. Trillions of dollars more might vanish in the coming months. Low, low interest rates—ones that many people expected to be around for years to come—underpinned that entire run-up in wealth.

Despite the gyrations in the financial markets and the collapse in the price of homes, crypto, and so on, the underlying real economy retains some real strength. The unemployment rate is very low, and households have not yet pulled back on spending. But inflation is dampening consumer sentiment and bleeding working families of cash; gas prices are particularly troublesome. To try to return the country to price stability, the Federal Reserve is continuing to hike interest rates, raising its benchmark rate 0.75 percent this week, the biggest jump since 1994. The central bank has no track record of pulling off the kind of “soft landing” it is aiming for. There’s a good chance the Fed will smother so much demand that the unemployment rate will climb and the economy will shrink, putting millions of families in financial peril. Everybody might end up worse off for a while.

In the future, should the Fed avoid lowering interest rates and flooding the country with money to avoid ginning up more inequality? That notion is certainly out there in progressive circles. “The basic thrust of the argument is that low interest rates make life sweet and easy for big corporate predators, who can do more of their bad predatory things thanks to lower financing costs. Stock valuations rise, the rich get richer, the powerful and corrupt thrive while the weak and ordinary are ignored,” writes Zachary D. Carter, the biographer of the economist John Maynard Keynes.

But this line of argumentation, as Carter notes, downplays the downsides of high interest rates for regular families. High interest rates mean slower growth means higher unemployment means smaller wage increases for low-income workers, in particular Black and Latino workers. In that way, low interest rates might help hold down wage inequality, even as they amp up wealth inequality. Sharply higher borrowing costs also make it harder for working families to pay off their credit cards, buy cars, start businesses, and fix up their homes.

The answer to our unequal age lies not in better monetary policy. It lies in better fiscal and regulatory policy. The central bank has enormous influence, but primarily over borrowing costs and the pace of economic growth. The power to alter the distribution of wealth and earnings—as well as expand the supply of child care, housing, energy, and everything else—lies with Congress.

It could spend huge sums of money to hasten the country’s energy transition and make it less vulnerable to gas-price shocks. It could overhaul the country’s system of student-loan debt, helping Black families build wealth. It could break up monopolies and force companies to compete for workers and market share again. It could task states and cities with increasing their housing supplies, so that regular families could afford apartments in Queens and houses in Oakland and condo units in Washington, D.C. It could implement labor standards that would mean the middle class could afford to buy into the stock market too. Yet it remains hamstrung by the filibuster, and by a minority party dedicated to upward redistribution.

The problem with our asset age is not that so much wealth has been generated. It is that so much wealth has been generated for so few. If everyone could own some Facebook stock and a house in Palo Alto, everyone would be better off, even in a down market. But low interest rates cannot create that world on their own.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/06/asset-economy-high-interest-rates-inflation/661323/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Federal Reserve Bank in New York

*

WEALTH: TALENT OR LUCK?

~ The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report in 2017 concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.8 billion people.

This seems to occur in all societies at all scales. It is a well-studied pattern called a power law that crops up in a wide range of social phenomena. But the distribution of wealth is among the most controversial because of the issues it raises about fairness and merit. Why should so few people have so much wealth?

The conventional answer is that we live in a meritocracy in which people are rewarded for their talent, intelligence, effort, and so on. Over time, many people think, this translates into the wealth distribution that we observe, although a healthy dose of luck can play a role.

But there is a problem with this idea: while wealth distribution follows a power law, the distribution of human skills generally follows a normal distribution that is symmetric about an average value. For example, intelligence, as measured by IQ tests, follows this pattern. Average IQ is 100, but nobody has an IQ of 1,000 or 10,000.

The same is true of effort, as measured by hours worked. Some people work more hours than average and some work less, but nobody works a billion times more hours than anybody else.

And yet when it comes to the rewards for this work, some people do have billions of times more wealth than other people. What’s more, numerous studies have shown that the wealthiest people are generally not the most talented by other measures.

What factors, then, determine how individuals become wealthy? Could it be that chance plays a bigger role than anybody expected? And how can these factors, whatever they are, be exploited to make the world a better and fairer place?

We finally get an answer thanks to the work of Alessandro Pluchino at the University of Catania in Italy and a couple of colleagues. These guys have created a computer model of human talent and the way people use it to exploit opportunities in life. The model allows the team to study the role of chance in this process.

The results are something of an eye-opener. Their simulations accurately reproduce the wealth distribution in the real world. But the wealthiest individuals are not the most talented (although they must have a certain level of talent). They are the luckiest. And this has significant implications for the way societies can optimize the returns they get for investments in everything from business to science.

Pluchino and co’s model is straightforward. It consists of N people, each with a certain level of talent (skill, intelligence, ability, and so on). This talent is distributed normally around some average level, with some standard deviation. So some people are more talented than average and some are less so, but nobody is orders of magnitude more talented than anybody else.

This is the same kind of distribution seen for various human skills, or even characteristics like height or weight. Some people are taller or smaller than average, but nobody is the size of an ant or a skyscraper. Indeed, we are all quite similar.

The computer model charts each individual through a working life of 40 years. During this time, the individuals experience lucky events that they can exploit to increase their wealth if they are talented enough.

However, they also experience unlucky events that reduce their wealth. These events occur at random.

At the end of the 40 years, Pluchino and co rank the individuals by wealth and study the characteristics of the most successful. They also calculate the wealth distribution. They then repeat the simulation many times to check the robustness of the outcome.

When the team rank individuals by wealth, the distribution is exactly like that seen in real-world societies. “The ‘80-20’ rule is respected, since 80 percent of the population owns only 20 percent of the total capital, while the remaining 20 percent owns 80 percent of the same capital,” report Pluchino and co.

That may not be surprising or unfair if the wealthiest 20 percent turn out to be the most talented. But that isn’t what happens. The wealthiest individuals are typically not the most talented or anywhere near it. “The maximum success never coincides with the maximum talent, and vice-versa,” say the researchers.

So if not talent, what other factor causes this skewed wealth distribution? “Our simulation clearly shows that such a factor is just pure luck,” say Pluchino and co.

The team shows this by ranking individuals according to the number of lucky and unlucky events they experience throughout their 40-year careers. “It is evident that the most successful individuals are also the luckiest ones,” they say. “And the less successful individuals are also the unluckiest ones.”

That has significant implications for society. What is the most effective strategy for exploiting the role luck plays in success?

Pluchino and co study this from the point of view of science research funding, an issue clearly close to their hearts. Funding agencies the world over are interested in maximizing their return on investment in the scientific world. Indeed, the European Research Council invested $1.7 million in a program to study serendipity—the role of luck in scientific discovery—and how it can be exploited to improve funding outcomes.

It turns out that Pluchino and co are well set to answer this question. They use their model to explore different kinds of funding models to see which produce the best returns when luck is taken into account.

The team studied three models, in which research funding is distributed equally to all scientists; distributed randomly to a subset of scientists; or given preferentially to those who have been most successful in the past. Which of these is the best strategy?

The strategy that delivers the best returns, it turns out, is to divide the funding equally among all researchers. And the second- and third-best strategies involve distributing it at random to 10 or 20 percent of scientists.

In these cases, the researchers are best able to take advantage of the serendipitous discoveries they make from time to time. In hindsight, it is obvious that the fact a scientist has made an important chance discovery in the past does not mean he or she is more likely to make one in the future.

A similar approach could also be applied to investment in other kinds of enterprises, such as small or large businesses, tech startups, education that increases talent, or even the creation of random lucky events.

Clearly, more work is needed here. What are we waiting for? ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/if-you-re-so-smart-why-aren-t-you-rich-turns-out-it-s-just-chance?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

Luck is the central character in Malcolm Gladwell’s Ouliers. Here is a brief summary by Paul Arnold:

~ Genius is over-rated. Success is not just about innate ability. It’s combined with a number of key factors such as opportunity, meaningful hard work (10,000 hours to gain mastery), and your cultural legacy. Random factors of chance, such as when and where you were born can influence the opportunities you have.

Opportunity knocks for some – often quite arbitrary (e.g. birthdates, in the right place etc)

Timing – Critical to success and opportunity.

Upbringing leads to opportunity – The quality of upbringing a child has been shown to be a key determinant on future success (even more so than pure IQ).

10,000 hours – it typically takes that amount of time to ‘master’ something. People with opportunity have the chance to ‘do’ the 10,000 hours. Others don’t.

Meaningful work – If you feel there is real purpose to your work, it’s more likely you will work hard.

Legacy – Our values drive our behavior. Our values are often passed down from generation to generation.

*

Thus, while we need to put in 10,000 (more or less) hours into mastering a skill, we don’t control if our family is rich and nurturing enough to provide us with the cost of the training. Furthermore, it turns out that practice is only one component. In fact we do need some innate talent for a particular activity — a matter of genetic luck, not choice. ~

*

HOW GRAVITY BATTERIES CAN PROVIDE CLEAN ENERGY

~ A cleaner future will mean focusing on ever-larger lithium-ion batteries, some energy experts say. Others argue that green hydrogen is the world's best hope. And then there are those placing their bets not on chemistry, but the limitless force that surrounds us all: gravity.

"What goes up, must come down" – this is the immutable Newtonian logic underpinning gravity batteries. This new field of energy storage technology is remarkably simple in principle. When green energy is plentiful, use it to haul a colossal weight to a predetermined height. When renewables are limited, release the load, powering a generator with the downward gravitational pull.

A similar approach, "pumped hydro", accounts for more than 90% of the globe's current high capacity energy storage. Funnel water uphill using surplus power and then, when needed, channel it down through hydroelectric generators. It's a tried-and-tested system. But there are significant issues around scalability. Hydro projects are big and expensive with prohibitive capital costs, and they have exacting geographical requirements – vertiginous terrain and an abundance of water. If the world is to reach net-zero, it needs an energy storage system that can be situated almost anywhere, and at scale.

Gravitricity, an Edinburgh-based green engineering start-up, is working to make this a reality. In April last year, the group successfully trialed its first gravity battery prototype: a 15m (49ft) steel tower suspending a 50 ton iron weight. Inch-by-inch, electric motors hoisted the massive metal box skyward before gradually releasing it back to earth, powering a series of electric generators with the downward drag.

The demonstrator installation was "small scale", says Jill Macpherson, Gravitricity’s senior test and simulation engineer, but still produced 250kW of instantaneous power, enough to briefly sustain around 750 homes. Equally encouraging was what the team learned about their system’s potential longevity.

"We proved that we can control the system to extend the lifetime of certain mechanical components, like the lifting cable," says Macpherson. "The system is also designed so that individual components can be easily replaced instead of replacing the entire system throughout its lifetime. So there's real scope for having a decades-long operational life.”

While the Gravitricity prototype pointed upward, the company's focus is now below ground. Engineers have spent the last year scoping out decommissioned coal mines in Britain, Eastern Europe, South Africa, and Chile. The rationale, explains managing director Charlie Blair, is pretty straightforward: "Why build towers when we can use the geology of the earth to hold up our weights?”

It seems like a neat solution. The globe is pockmarked with disused mine shafts deep enough to house a full-sized Gravitricity installation, which will stretch down at least 300m (984ft), and possibly much further. There's political will to make it happen too, Blair says, with policymakers keen to tap into public enthusiasm for a so-called "just transition" – the notion of a new, low-carbon economy that secures the livelihoods of fossil fuel workers and their communities. And so, with enough funding, a subterranean prototype (most likely located in the Czech Republic) should be functioning by 2024. First, though, a series of challenges must be overcome.

"We need to look closely at the existing civil structures – the shaft lining, the shaft’s surroundings – and make sure they're absolutely sound and capable of holding up several thousand tons," Blair explains. "There are also potential safety issues around methane gas, and the mines being flooded.”

With that in mind, Gravitricity is also looking at sinking its own purpose-built shafts: an endeavor that'll cost more upfront, but promises far greater uniformity further down the line.