Rogier van den Weyden: St. Michael Weighing the Souls, from the Last Judgement, C.1445-50

*

ANTIGONE

The moon is the thinnest

crescent tonight.

The guards wait for me,

idly thrusting their lances

into the helpless ground.

It’s a dance we’ve learned by heart:

I do what I know is right.

They follow orders.

There is no sign from heaven.

I sprinkle water and dirt

over my brother’s gaping

mouth, and mumble sacred words.

Sometimes the cry of crickets

pierces the night with such

pure prayer that I want to

live forever. . . but no, I must.

My practical uncle dislikes

the unpleasantness of an execution.

He’ll talk to me again

about the changing times,

how there is no such thing

as a “higher law.”

“You’re a smart girl. Why

throw away your future? Why?”

I'm dangerous to the state.

The stream in the ravine

glistens like black sun.

Even to my sister I won’t

say how something within

cries Despair! Despair!

And daily something replies,

Truth cannot be defeated.

~ Oriana

We studied Antigone in high school. I was astounded that the Polish Ministry of Education would let us. Didn't they see how the play encouraged resistance against the morally wrong laws of a dictatorship? Or perhaps someone in the Ministry was secretly a kind of Antigone?

*

TURGENEV’S LIBERAL SENSIBILITY

~ Two newly coined words dominated Russian discussions in the early 1860s: intelligentsia and nihilism. The first referred not to educated people generally but to those professing a new radical ideology formulated by the critic Nicholas Chernyshevsky. The “new people,” as Chernyshevsky called his young followers, advocated materialism, determinism, utilitarianism, free love, and rude (they said “frank”) manners. In his great novel Fathers and Children [more often translated as “Fathers and Sons”], Ivan Turgenev called them “nihilists.” Although many young radicals first deemed this term slanderous, they soon adopted it with pride. When the assassin and writer Sergei Stepniak published a novel in 1889 celebrating terrorism, he entitled it The Career of a Nihilist.

Even Dostoevsky, who cherished a lifelong hatred for Turgenev, regarded Fathers and Sons as a masterpiece. Turgenev had perfected the novel of ideas, the genre that, over the next two decades, was to include not only all Dostoevsky’s greatest works, but also Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Anna Karenina as well as two more important Turgenev novels, Smoke and Virgin Soil. The glory of Russian fiction, this genre later inspired works by Pasternak, Grossman, and Solzhenitsyn reflecting, like their nineteenth-century predecessors, on the ultimate questions of life. [Oriana: Vasily Grossman isn't as well known in the West, but his novel Life and Fate is regarded as a masterpiece.]

Many Russian novels of ideas have adopted Turgenev’s device of describing intellectual dispute as a conflict of generations. Turgenev’s “fathers,” represented by the brothers Pavel Petrovich Kirsanov and Nikolai Petrovich Kirsanov, profess liberalism indebted to British politics, admire refined manners taken from French society, and adhere to the misty, sentimental idealism of German philosophy. Though living far from society on his brother’s estate, Pavel Petrovich dresses to perfection while surrounding himself with evidently useless symbols of enlightened Western ideas. Nikolai Petrovich recites Pushkin’s verses, plays romantic music on his violincello, and indulges in nostalgic reveries while admiring the beauties of nature. The young nihilists, for their part, scorn all high ideals and abstract principes (Pavel Petrovich uses the French term) as so many empty words accomplishing nothing. “Aristocracy, Liberalism, progress, principles,” declares the novel’s nihilist hero Evgeny Bazarov. “No Russian needs them, even as a gift.” Turgenev appreciates that the nihilists’ scorn is no less rhetorical than the idealists’ poetic flourishes.

As the novel begins, Nikolai Petrovich has been waiting five hours at the station for his son Arkady, coming home from the university. Lonely since his beloved wife died, and a devoted father, Nikolai Petrovich has spent months in the capital attending lectures and keeping up with new ideas so as to be close to his son, but all in vain. When Arkady arrives, he has brought his friend Bazarov, whom he idolizes. One of the new people and the son of a poor local doctor, Bazarov not only lacks aristocratic manners but despises them, to the immense irritation of Pavel Petrovich. “This son of a medico,” Arkady’s uncle thinks, “was not only unintimidated; he gave abrupt and indifferent answers, and in the tone of his voice there was something coarse, almost insolent.”

As Nikolai Petrovich sadly recognizes how distant his son has grown, he voices one of the book’s key themes, the tragedy of passing time. Against the backdrop of social change and the progress of generations—as fathers yield to children who will soon suffer the same fate—people learn what it means to survive into an estranging future. Blink and you are passé. The ones you love the most no longer understand you, and the loneliness of outdated beliefs overwhelms you. It doesn’t matter whether those beliefs are truer or better than those that have replaced them.

Lingering in the arbor, Nikolai Petrovich overhears Bazarov tell Arkady: “Your father’s a nice man . . . but he’s behind the times; his day is done. . . . The day before yesterday I saw him reading Pushkin. . . . Explain to him, please, that that’s entirely useless . . . what an idea to be a romantic these days!” Reporting this conversation to his brother, Nikolai Petrovich regrets the futility of the liberal reforms on his estate and of his strenuous efforts not to fall behind. The very emotions that prompted him to those efforts, his idealism and “sentimentality,” testify to his outdatedness. “Do you know what I was reminded of, brother?,” Nikolai Petrovich asks:

I once had a dispute with our late mother; she shouted, and wouldn’t listen to me. At last I said to her, “of course, you can’t understand me; we belong,” I said, “to two different generations.” She was dreadfully offended, while I thought, “it can’t be helped. It’s a bitter pill, but she has to swallow it.” You see, now, our turn has come, and our successors can say to us, “You are not of our generation; swallow your pill.”

Turgenev himself belonged to the older generation and represented its values, as Chernyshevsky insisted in his influential essay “The Russian at the Rendezvous,” a review of Turgenev’s novel Asya. In reply, Fathers and Sons examined Chernyshevsky’s views by giving them to Bazarov and Arkady.

The very fact that Turgenev replied in a novel was itself an ideologically charged act, because the “new people” rejected not only romantic poems like Pushkin’s but also realist novels like Turgenev’s. As both sides recognized, literary genres embody philosophical assumptions. As epics take for granted the value of glory and heroism, and saints’ lives the existence of holiness, so realist novels presume the complexity of human psychology and the uniqueness of each individual. That, after all, is why so many novels—Effi Briest, Anna Karenina, Père Goriot, Jane Eyre, Doctor Thorne, Asya—are named for a hero or heroine. The radicals, on the other hand, insisted that psychology was simple and denied that individuality exists at all. In their view, the interchangeability of people is precisely what makes possible a hard social science, which Chernyshevsky thought already existed. A few simple laws, based on “physiology and chemistry,” explain everything needed to understand and reconstruct life. So-called individuals, Chernyshevsky explained, are “only special cases of the operation of the laws of nature.”

Look closely, Chernyshevsky instructed, and you will discover in each landowner or merchant “all the shades of thinking appropriate to his class.” As with cedars or mice, he continued, the differences within the human species are too trivial to matter. “You have practically reached the limits of human wisdom,” he concluded with absolute confidence, “when you become convinced of the simple truth that every person is exactly like every other one.”

Bazarov echoes these views: “Studying separate individuals is not worth the trouble. All people resemble each other. . . . [E]ach of us has brain, spleen, and lungs made alike; and the moral qualities are the same in all; the slight variations are of no importance. A single human specimen is sufficient to judge all the rest . . . no botanist would think of studying each individual birch-tree.” Even the differences among species don’t matter much. Bazarov dissects frogs to show how closely they resemble people. So influential did these fictional dissections become that countless real frogs lost their lives to young people proving their nihilist credentials. “In the splayed frog,” the radical critic Dmitri Pisarev famously declared, “lies the salvation of the Russian people.”

In novels, love unites unique souls, revealed in their essence through the intensity of emotional experience. But for Bazarov, there is nothing to reveal. That whole view of love, he intones, is just so much “romanticism, nonsense, rot, artiness.” “And what of all these mysterious relations between a man and woman?,” he sneers. “We physiologists know what these relations are. Study the anatomy of the eye a bit; where does the enigmatical glance [described by novelists] come in there?” No novelist ever surpassed Turgenev in using fine shading of verdure to suggest the elusive shadings of feeling, but for Bazarov “nature’s not a temple, but a workshop, and man’s the workman in it.”

The plot of Fathers and Sons exemplified the pattern for ideological fiction to come. The works of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and European writers test theories not by logic, evidence, or counter-argument, as philosophical treatises do, but by examining what it means to live by them. Theories are subjected to two ironies, which I like to call the irony of origins and the irony of outcomes.

The first irony, directed primarily at Arkady, shows that, however certain we may be of ideas, we accept them not because of their cogency but, at least in part, because of their capacity to meet our psychological needs. Wanting to prove how grown up he is, Arkady experiences “that awkwardness which usually overtakes a youth when he has just ceased to be a child and has come back to a place where they are accustomed to regard and treat him as a child.” Voicing shocking views—art is bunk, everything should be destroyed!—becomes his way to demonstrate adulthood. He remains naïvely unaware that proving one’s adulthood is a childish thing to do.

Arkady “blushes with delight” when he shocks his father and uncle by rejecting idealism,

liberalism, the appreciation of nature, and anything else they might believe in. “You are aware of my views,” he tells his father, and Turgenev comments: “it was very sweet to Arkady to utter that word.” Looking at his authority, Bazarov, for approval, he rejects all authorities; but Bazarov appears to understand that Arkady has made a principle of denying principles and has adopted materialism for idealistic reasons. The condition of the peasants requires universal destruction, Arkady tells the old folk: “We are bound to carry out these requirements. We have no right to yield to the satisfaction of our personal egoism.”

This last phrase apparently displeased Bazarov. There was a flavor . . . of romanticism about it . . . . [B]ut he did not think it necessary to correct his young disciple.

Personal egoism is what a nihilist is supposed to satisfy, what he believes he cannot help satisfying since that, according to the new philosophy, is the only human motivation. It is the idealists of the previous generations who are concerned to overcome egoism. These lapses from nihilist doctrine indicate how much it runs counter to Arkady’s fundamental nature and the beliefs he really holds. We smile gently at his childish self-deception.

Turgenev subjects Bazarov’s views to a less forgiving scrutiny, the irony of outcomes. In this respect, Fathers and Sons exemplifies the masterplot of novels of ideas. They narrate the story of how life, presenting unforeseen consequences that cannot be gainsaid, demonstrates a theory’s inadequacy. In The Brothers Karamazov, for instance, Ivan maintains, first, that good and evil are mere social conventions, and, second, that even if evil does exist, it applies only to actions and not to wishes. Contrary to both beliefs, he winds up feeling intense guilt for a murder he has not committed, but only desired. In War and Peace, Prince Andrei’s experience of lying severely wounded on the battlefield and contemplating the “infinite heavens” proves to him the triviality of the “glory” he has lived for and the faith in military “science” that has guided his actions.

Turgenev sets the pattern by having Bazarov fall in the sort of love whose existence he has denied. Precisely because he denies it, indeed, a sophisticated woman can captivate him all the more easily, especially when she intoxicates him with the beauties of nature he has also dismissed. In the novel’s key passage, Turgenev describes his hero “tortured and maddened” by a feeling “he would at once have denied with scornful laughter and abuse, if anyone had ever so remotely hinted at what was taking place in him.”

Bazarov used to wonder why “Toggenburg and all the minnesingers and troubadours had not been put into a lunatic asylum,” but now he cannot overlook that something “was taking root at him, something . . . at which his pride revolted.” Trying to banish all these shameful thoughts, Bazarov would “obstinately . . . try to force himself to sleep, in which of course, he did not always succeed.” The narrator’s favorite phrase “of course”—no explanation is necessary for those with experience enough to understand life—suggests the superior knowledge that he and the presumably mature reader share.

It would have been easy enough for Turgenev to rest content with this triumph over his hero, which is really the victory of novels over naïve materialism, but Turgenev is too self-aware for that. Refuting nihilism in a novel is like exposing sin in a saint’s life or discrediting cowardice in an epic: the very choice of genre renders the outcome almost inevitable. As they used to say in the old Westerns (and perhaps in some contemporary proceedings), “first we’ll give him a fair trial, and then we’ll hang him.” What makes Fathers and Sons a true masterpiece is how genuinely evenhanded it is. Turgenev also focuses the novel’s unforgiving lens on his own most cherished beliefs and brings their weaknesses into focus.

“I am Nikolai Petrovich,” Turgenev declared in one letter; and when Nikolai Petrovich measures himself against Bazarov, he recognizes that, for all the young man’s arrogance and naïve scientism, there really is something superior about him. For one thing, Bazarov has “fewer traces of the slaveowner” in him, by which Nikolai Petrovich means to suggest that his own way of life, dependent as it is on the labor of serfs, is morally compromised. That would apply to the wealthy nobleman Turgenev as well. Nikolai Petrovich also recognizes—and so does the novel’s narrator—that Bazarov has one quality they utterly lack: courage.

When facts refute our most cherished beliefs, most of us explain away the facts. Bazarov does not. After he falls in love, he recognizes that experience has disproved his theories. Surrendering his sense of certainty, he entertains doubts that are new to him. He becomes, in fact, something of an existentialist facing a meaningless universe. He echoes the thoughts that led Pascal to faith.

Lying on a haystack with Arkady, Bazarov reflects, as he never would have before, on his insignificance:

The tiny space I occupy is so infinitely small in comparison with the rest of space . . . which has nothing to do with me; and the period of time in which it is my lot to live is so petty beside the eternity in which I have not been, and shall not be . . . . And in this atom, this mathematical point, the blood circulates, the brain works and wants something . . . . Isn’t it hideous?

Bazarov now calls the shocking things he used to say “reverse commonplaces”: claiming that education is beneficial, for instance, is a commonplace; claiming that it is injurious, “that’s a reverse commonplace. There’s more style about it,” but it’s just as shallow.

Bazarov turns the logic he has applied to others—their beliefs are the product not of serious reflection but of chemicals in the brain—on his own convictions. It’s as if a Marxist at last recognized that Marxism, too, is just another ideology serving class interest, in this case, of the intelligentsia professing it. When Arkady marvels at Bazarov’s refutation of his former views, Bazarov replies forthrightly: “If you’ve made up your mind to mow down everything, don’t spare your own legs.” If honesty is, as he has said, only a “sensation,” it is one that shapes his deepest self.

Bazarov faces his untimely death from typhus with courage—more courage, indeed, than Turgenev, for whom his hero’s end is almost too tragic to bear. The novel concludes by describing the intense grief Bazarov’s parents suffer as they frequent their son’s grave, “where they seem to be nearer to him.” In his closing lines, Turgenev focuses not on their sorrow but on his own tormenting doubts:

Can it be that their prayers and their tears are fruitless? Can it be that love, sacred, devoted love, is not all-powerful? Oh, no! However passionate, sinning, and rebellious the heart hidden in the tomb, the flowers growing over it peep serenely at us with their innocent eyes; they tell us not of eternal peace alone, of that great peace of “indifferent” nature; they tell us, too, of eternal reconciliation and of life without end.

“Oh, no!” the narrator says, as if he lacks the moral strength to accept what he knows to be true. One imagines how the bravely dying Bazarov might have responded: prayer is not all-powerful; flowers say nothing unless we supply the words; and the only eternal peace is endless silence and death without end.

The greatness of this book lies in the way it goes beyond most novels of ideas, whether by Joseph Conrad, Henry James, or even Dostoevsky. It refuses to exempt the presuppositions of novels from unwelcome scrutiny and concedes that the wisdom of the most sophisticated novelists—like Turgenev himself—may exact a moral price. The wisest people may not be the best. Instead of refuting opposing values, this novel initiates a dialogue with them.

*

Dostoevsky regarded Turgenev’s moral shortcomings as much worse than he allowed. Even Turgenev’s willingness to question his own assertions served, in Dostoevsky’s view, as just another way of demanding praise. No matter the topic, for Turgenev it matters less than his own reactions to it. A moral weakling, Turgenev was for Dostoevsky one of those limp liberals prepared to succor revolutionaries to win their favor. The danger of such self-congratulatory thinking shaped the plot of Dostoevsky’s The Possessed, which, as if to answer Fathers and Sons, also examined the ideological bases of generational conflict. The liberal parents in Dostoevsky’s novel engender, literally and figuratively, the terrorist children dedicated to destroying them.

No reader could have missed the remarkable resemblance between the novel’s most repulsive liberal, the “great writer” Karmazinov, and Turgenev. As Joseph Frank has observed, “the takeoff on Turgenev’s literary mannerisms and personal foibles could not have been deadlier and it enriches The Devils [i.e. The Possessed] with a dazzling display of Dostoevsky’s satiric virtuosity.”

Looking for alternatives to Tsarist and Bolshevik repression, critics often idolize Turgenev, who professed Western liberal values. To these critics, Turgenev represents the path that was not, but could have been, taken. That may be true, but Turgenev also illustrates the weaknesses of Russian liberals that, in the decades preceding the revolution, ensured their failure. Like Karmazinov (whose name comes from the French word for “crimson”), they were ready to justify anyone to their left, even terrorists who killed thousands of officials and bystanders, threw bombs laced with bullets and nails into crowded cafés, and mutilated victims’ faces with sulfuric acid.

Not once did Rech’, the newspaper of the liberal Kadet (Constitutional Democratic) party, denounce terror, and when the Tsar issued an amnesty for political prisoners, Kadet leaders demanded it include terrorists who pledged to continue killing. In an article extolling the imprisoned killer “Marusia” (affectionate for Maria) Spiridonova, a columnist in Rech’ intoned: “her life [zhizn’] has ended, her saint’s life [zhitie] has begun.”

“Condemn terror?,” exclaimed Kadet leader I. Petrunkevich. “Never! that would mean the moral death of the party.” Why did these liberals not understand they were playing with fire? Within a few weeks of their takeover, the Bolsheviks declared the Kadets “outside the law”—meaning anything could be done to them—and a mob promptly lynched two hospitalized Kadet leaders. Even Bolshevik attempts to annihilate the Kadets entirely did not convince most leaders who had escaped abroad of their error in sanctifying terrorists.

Would Turgenev himself have praised terrorists? The fact is, he did. Revolutionaries routinely cited one of his last works, the prose poem “The Threshold,” as admiring their violence. Written in the midst of Russia’s first major terrorist campaign, it pictures a young woman about to cross the threshold into a life of terror. “Do you know what awaits you?,” a voice asks. Do you know you face “cold, hunger, hatred, mockery, scorn, resentment, imprisonment, even death? . . . Are you prepared for any sacrifice . . . to commit a crime,” and, perhaps, “realize that you have deceived yourself and destroyed your young life in vain?” Yes, she answers to all questions, and crosses the threshold. The prose poem ends:

“Fool!” someone shrieked from behind it.

“Saint!” came from somewhere in reply.

Oddly enough, the first voice, though accusing her of folly, omits questioning her readiness to sacrifice not only her own life but also those of others.

*

If Turgenev represents the liberal sensibility Russians wrongly rejected, he also exemplifies the psychology that has given liberals, especially Russian liberals, a bad name. From vanity, from the desire to be accepted by the right people, and from fatal short-sightedness, Russian liberals celebrated revolutionaries who despised their values and sought to destroy them. The lessons to be learned from Turgenev go beyond his masterly novel. ~

https://newcriterion.com/issues/2021/9/turgenevs-liberal-sensibility

Oriana:

This is relevant today, as we watch "progressives" failing to speak out against anything, however wrong-minded, coming from the extreme left. Turgenev's masterpiece stands out by pointing out the weaknesses and flaws of both sides.

As for the scene of the initiation of a young woman into a revolutionary organization, it's up to the reader to decide whether she is a saint or a fool (and a potential murderess). It's a test of the reader's values. Turgenev doesn't preach; he makes us question and think.

Mary:

It is interesting that Turgenev has the nihilists as the young generation. I am sure that's a reflection of the historical situation, that these were the new ideas of a new generation, but it seems particularly apt that his nihilists are adolescents. It seems impossible for anyone who is mature to seriously take up such a philosophy. The radical stance, the egoism, the refusal of not only tradition, but culture, values, liberalism in favor of....what?? Eventually, the "celebration of terrorism.”

It is particularly delicious that the ideologue who despises the romanticism of his elders finds himself swept up in a romantic passion...to his consternation, and the reader's delight. I am certainly reminded of Dostoyevsky's Raskolnikov, who acts on this kind of belief, commits an act of terrorism, a murder simply to demonstrate he can...achieving only his own long suffering..That too, is the act of an adolescent, and proves only the opposite of his radical presumption.

It is also interesting that Turgenev's hero, Bazarov, sees how his experience puts his ideology in question. The ideas have to tumble in the face of his physical and psychological reality, and he ends up with something much like an existentialist position — that all ideologies come down to the material reality of brain chemistry, and physiology, and nothing more. Yes, there is courage in that honesty. A courage and honesty, as you note, conspicuously absent from progressives who won't speak out against the wrongs of the extreme left. We've all seen how that plays out, and into, the creation of totalitarianism.

Oriana:

Precisely. The book is a masterpiece. Bazarov is brilliant, and, once chastened by unrequited love, he becomes a tragic figure. The reason that the woman he loves doesn’t return his feelings is that she’s a young widow who’s known a bad marriage, and doesn’t want to lose her freedom. We must remember that back then you couldn’t just have a “relationship.”

As for the book's political relevance, it's hard for me to believe how little humanity seems to learn from history. Perhaps it's because the heads of state are often madmen, just like cult lealders, even in the clinical sense.

*

LIMITS TO GROWTH STUDY PREDICTED SOCIETAL COLLAPSE IN MID-21ST CENTURY

~ A 1972 study conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology known as “The Limits to Growth” predicted that society would collapse sometime in the middle 21st century. Contemporary research from a director at one of the world’s largest accounting firms shows that the study’s prediction alarmingly appears to be accurate.

In 1972, MIT scientists set out to study what it would take for society to collapse under real world conditions. Their system dynamics model, commissioned by the Club of Rome, showed that there were “limits to growth,” a kind of cap on how many resources we could produce and consume as a society, especially considering factors of “population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption of nonrenewable natural resources” according to the study.

Using a computer simulation to model these factors, the scientists found that civilization would likely collapse in the mid-21st century due to the strain of the rabid consumption of the planet’s resources.

The report, which was published under the name “The Limits to Growth,” quickly became a sensation. It has sold 30 million copies in 30 different languages. The results were the source of much controversy and cutthroat debate between experts and journalists alike.

New research shows “The Limits to Growth” is accurate.

Now a senior director at KPMG, a Dutch firm that is amongst the “Big Four”– a nickname for the four largest accounting firms in the world — has published her own study affirming the results found over thirty years ago by MIT.

That director is Gaya Herrington, who leads Sustainability and Dynamic System Analysis at KPMG’s office in the United States. Herrington’s study, which was published in the Yale Journal of Industrial Ecology in November 2020, can be read on KPMG’s own website.

Asked why she had decided to take up the gauntlet of the infamous study, Herrington said that “Given the unappealing prospect of collapse, I was curious to see which scenarios were aligning most closely with empirical data today.

“After all, the book that featured this world model was a bestseller in the 70s, and by now we’d have several decades of empirical data which would make a comparison meaningful. But to my surprise I could not find recent attempts for this. So I decided to do it myself.”

Herrington’s study analyzes the same factors as the original Limits to Growth. What she found was that if our civilization continued to grow “population, fertility rates, mortality rates, industrial output, food production, service, non-renewable resources, persistent pollution, human welfare, and ecological footprint,” — the ten key variables she outlines — at a rate that was “business as usual,” or consistently upward, with no change in consumption, we would indeed be on track for collapse within this century.

“Economic and industrial growth will stop, and then decline, which will hurt food production and standards of living… In terms of timing, the BAU2 (business-as-usual) scenario shows a steep decline to set in around 2040” said Herrington in her sobering recent report. ~

https://greekreporter.com/2021/08/05/the-limits-to-growth-predicted-society-collapse-research/

Mary:

Only two small thoughts on the limits of growth and the collapse of society. Continual and endless growth is a principle and requirement of capitalism. And a description of cancer. Does development always necessarily mean growth? Might less not be more here as well as in so many other places? An example that irritates me is the continual and absurd proliferation of consumer products. Look at a supermarket's shelves. Ok toothpaste. A good thing, but do we need hundreds of slightly different kinds? Each brand (and there are many) has a long list of (slightly) different flavors, colors, types, sizes, etc. And that's just one product. It becomes a job in itself, and I would argue an unnecessary irritant, if not an outright burden, simply to shop for basics. All this choosing takes up time and attention that could be used better elsewhere. Everything becomes a big job, a big deal, from toothpaste to cars...and this choosing is an illusion of plenty and an illusion of freedom. More and more, as the products proliferate, they are more and more and more of the same.

My second thought, is that these predictions of collapse are predicated on things going on the same as they have been. I think there is a very good chance they won't. We are inventive. Every time we come up against some obstacle, or have some new desire, we get ideas. New science, new technologies, new ways to travel, work, communicate, and the world changes. It has been noted that everywhere, globally, the birthrate is falling — at least partly, and maybe largely, due to the rise in education and opportunity for women, and, crucially, to the availability of birth control. A woman with access to birth control will have fewer children than a woman who has no such access. A falling birthrate will undoubtedly bring its own problems (fewer young people working to provide for proportionally larger population of elderly), but they won’t look like the problems facing an ever growing population.

I must confess, I have great hopes for the future, and wish I could be here to see more of it!

Oriana:

I am very curious as well — even about ten years from now. Much as I lament the fact that my neighbors are tearing out greenery and filling their yards with rocks, I must admit that even this shows that rapid change is possible. Of course I don’t mean just this — it’s a million other things relentlessly changing — because the only thing that doesn’t change is change itself. Maybe that’s where the hope lies.

What sometimes drives me to despair is the human tendency not to do anything until the last minute. For instance, the technology to take out carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere already exists, but not the avid interest it should generate, given the choice between an amazing future and extinction.

*

WHY ARE AMERICANS LESS HAPPY NOW?

~ In the first year the World Happiness Report was published (2012), the United States came in 11th. But the most recent report finds the U.S.A. down eight happiness rungs, to the 19th position.

In reality, Americans aren’t particularly sad compared to the rest of the world — in fact, they’re objectively among the happiest. The United States ranks 19th out of 149 countries, after all. But whether it’s because the U.S. is the wealthiest country in the world; or because of that relentless optimism Americans are known for worldwide; or a widely held belief (by Americans) that America is innately different from the rest of the world, scholars and politicians have wondered why this country isn’t at the top of the list.

COVID-19 may be responsible for much of the drop. But more than a global pandemic, a mix of economic, social and cultural circumstances have joined together over time to create a particular kind of American discontent. And though Americans still enjoy relatively happy existences, there are ways they can do better.

The impact of COVID-19 might explain some of the downward happiness trends America has been seeing. Increased loneliness, uncertainty and joblessness have made American problems, and other problems, much worse. American life satisfaction took a tumble and kept falling after April of 2020, and “negative affect” (a measure of emotions and self-concept) began to crawl up. Then the COVID Response Tracking Study found that more Americans than in the past were pessimistic and unhappy about the future.

But COVID-19 can’t explain the trend Americans have experienced since long before the pandemic hit — according to a number of sources, they’ve been trending downward for years.

AN ECONOMIC STORY

“We're always convinced we're exceptional. And now it seems to me we're exceptional in our stupidity more than anything else,” says Carol Graham. Graham is a Senior Fellow at the Brookings institute, a think tank specializing in social sciences; Graham’s expertise is in measuring American well-being.

“We were the only rich country in the world prior to COVID where mortality rates were going up rather than down,” Graham says. “And that was due to deaths of despair in less than college educated middle aged whites.” Suicide, drug overdose, and liver disease from alcohol are typically known as “deaths of despair” because they happen more in groups with little hope for improved economic or social conditions.

Graham’s research tells a story of economic upheaval beginning long before the pandemic hit — bolstered by a racist history — that’s had unexpected outcomes. As well-paying blue collar jobs for white men in American manufacturing disappeared and Walmarts moved in, joblessness, low education, addiction and despair followed.

Meanwhile, non-white Americans, who spent centuries battling discrimination in American workplaces, economies and society, built informal networks of support in extended family or religious institutions. They prioritized higher education as a way to improve life. In fact, while Black and Hispanic Americans (two major groups for whom census data is gathered) still face higher student loan debt, healthcare disparities, and higher rates of poverty, they are more optimistic than ever before.

But as rural, white communities continued to hang on to the American dream with fewer and fewer prospects, they saw their own belief system crumbling.

“The group that most believe, hook line and sinker, ‘you work hard to get ahead, you don't want government support, government support’s for losers,’ all of a sudden needs collective support, needs all sorts of things, and doesn't have those natural, informal social linkages,” Graham says. And because America is still majority white, American unhappiness went down overall.

This isn’t the first time social scientists have pointed toward American economics as the root of American unhappiness. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a psychologist at Claremont Graduate University who was known for his work on happiness and creativity, wrote back in 1999 about capitalistic measures of our own success,

THE SOCIAL STORY

Economics, however, may not tell the entire story of American discontent. Tied up in the classic narrative of hard work, material payoff and more recently, workaholism, is a reliance on the individual and not the group. In one study on the US, Russia, Germany and East Asia,

researchers found that those in cultures that value collectivism versus individualism tended to be more successful in pursuing happiness because of an emphasis on social engagement.

“The richest countries are not happiest, the healthiest countries are not always the happiest. The happiest countries are the ones who do have the highest levels of a whole range of things,” says John Helliwell, an editor of The World Happiness Report and professor emeritus of the Vancouver School of Economics. “They include, especially, a willingness to trust each other to work for each other, and to come together in times of difficulty.”

Helliwell describes speaking to executives in Denmark, the second happiest country according to the World Happiness Report, about their workplaces, which he described as more collaborative and communal. “They share the same lunch room, they share the same conversations about what to do to make a better product, knowing about what's going on in the other's families,” Helliwell says. Pay was also, crucially, more equal. That is, the gap in pay between the highest- and lowest-paid workers at a company was relatively small. “These flat structures are happier places to work. And they're often more effective.”

The United States, on the other hand, is one of the most unequal rich countries, and the most unequal of the G7 nations, according to the Pew Research Center. Inequality, which the World Happiness Report uses as one of the strongest measures of social trust, plays a big role in happiness. Access to healthcare and education is also unequal, Helliwell adds. “Despite lots of people's efforts, it probably is less equal than it was 50 years ago. And that has consequences.”

Continental poverty divide

SOCIAL COMPARISON IN AMERICA

It may not be that inequality would affect individuals in a vacuum. After all, if we didn’t know how well-off Jeff Bezos — or even our neighbor — was, we might not care. But the feeling of relative scarcity, that one has less compared to others, is a powerful one. And we’re not just limited to our neighborhood or commute in absorbing what others have — social media, with its roots in America, allows us to be bombarded with it at all hours of the day.

“That idea of wanting to have a better car, or a better backdrop for your vacation photo, or your wedding is probably more prevalent in the United States than elsewhere,” adds Helliwell. And a growing body of research supports this phenomenon. One study found that more Facebook, Instagram and Twitter use resulted in less well-being, while the opposite was true of real, face-to-face social interaction.

There’s also much less bullying and arguing. “Once people get a chance to meet each other and sit down and talk together,” says Helliwell, “they're much less likely to even consider the option of saying negative things about each other or act in negative ways. Social media has a built-in distance.”

And, Helliwell points out, mass media has a way of overreporting the bad and exaggerating perceptions of danger and mistrust. But it’s not all doom and gloom. Helliwell says that based on findings from the World Happiness Report, COVID-19, surprisingly, allowed people worldwide to see more examples of people helping one another out.

“People are now acutely aware that there are people who need help. And what's more, they're doing something about it,” Helliwell says. “People who are not going to Brazil on a mountaintop on their holidays, but are walking in their block and meeting their neighbors, ended up getting happier.”

https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/why-are-americans-getting-unhappier?utm_source=acs&utm_medium=email&utm_email=ivy333%40cox.net&tm_campaign=News0_DSC_210822_00000_Health

* * *

“Has it ever struck you that life is all memory, except for the one present moment that goes by you so quick you hardly catch it going?” ~ Tennessee Williams

Oriana:

That's why the thought of Alzheimer's or any other memory-erasing condition is so frightening. You'd think that would result in a lot of research funding for brain diseases. Not so. Cancer comes ahead. And aging itself (most chronic diseases are the diseases of aging) is in 15th place. Alzheimer's Disease is in 35th place.

*

“Anyone who ever gave you confidence, you owe them a lot.” ~ Truman Capote, Breakfast at Tiffany

Oriana:

I'm infinitely grateful to all those who gave me confidence. They say it takes only one person who believes in you, and you'll be OK. That may be true, but after you get used to being attacked and put down every day, and having been bullied in school, it helps if it's many supportive people rather than just one -- though every supportive comment helps. I bless every editor who took a minute to scribble a note, even every man whose face lit up when he looked at me (no sexual harassment, that!) I bless every unknown driver who's ever let me into a lane -- that too has added to my confidence — in the basic goodness of humanity and myself (studies found that performing an act of kindness makes people happy).

*

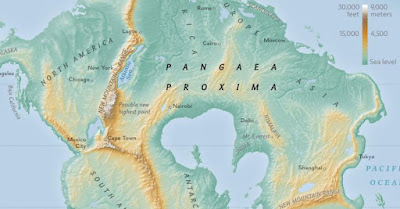

THE WORLD 250 MILLION YEARS FROM NOW

~ Africa is going to smash into Europe as Australia migrates north to merge with Asia. Meanwhile the Atlantic Ocean will probably widen for a spell before it reverses course and later disappears. ~

If our existence spanned hundreds of millions of years instead of just a handful of decades, we would see land masses constantly merge and break up again, their dance around the earth powered by a near-continuous orgy of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

For at least a few times already, all of our planet's dry bits have come together to form a single, giant island in a single, giant sea. Roughly 200 million years ago, Pangaea was the last iteration of this recurring supercontinent. That deep history will repeat itself. In another 250 million years, we'll have the next supercontinent. We've already got the name: Pangaea Proxima.

Here's what our world will look like at that time: the Americas attached to Africa in the north and Antarctica in the south; Africa slammed into Europe and the Middle East; and Australia welded to Asia's east. The giant continent is centered around the remains of the Indian Ocean, now an interior sea mirroring the former Mediterranean, with a boot-like India posing as a replacement Italy.

Where continents have collided, new mountain ranges have arisen. The world's new high point is no longer located in the Himalayas, but in the as yet unnamed range that has sprung up where Florida and Georgia have slammed into South Africa and Namibia.

It's unlikely that there will be any humans around to witness the reunification of the world's land masses – we'll be lucky to survive the next century, let alone the current millennium – but the map includes some present-day cities nevertheless, for your orientation.

Or more likely, for your disorientation. On Pangaea Proxima, Cape Town and Mexico City are just a day's drive apart. Lagos is to the north of New York, and both are close to the Atlantic Sea, the shrunken remnant of the former ocean. And you could travel from Sydney to Shanghai and on towards Tokyo without having to cross a single body of water.

Europe has attached itself to Africa, and Britain – Brexit notwithstanding – has rejoined Europe. One thing has remained reassuringly the same: New Zealand is still an isolated place, forever threatening to fall off the bottom right part of the map.

https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/what-the-world-will-look-like-in-the-year-25000

*

THE EYE IN THE SKY: FUSING GOD AND SATAN

One morning I had a naughty thought, “If I were god, I would do good things for people.” Later, an even more subversive thought arose (I take no responsibility for my thoughts. They simply arise). Remembering how god was presented to us as the eye in the sky, spying on everyone’s sins, I realized that in the book of Job there was a hint that this was the function of one of the sons of god, Satan (ha Shatan) — THE ADVERSARY. The Prosecution. It was Satan who “walked up and down the earth,” building the case against this or that human being.

It was bad enough that god would make bets with Satan. There was no need to fuse the two entities. God was unlovable enough as judge and executioner. To make him also collect the evidence for the Prosecution was really going too far.

In Rogier van der Weyden’s painting, the task of “weighing the souls” (the heavier ones went to hell) seems to have been delegated to Archangel Michael. In the town where I was born, right under the “ambona” (from where the priest preached the sermon) there was a baroque naked angel (with a sculpted loincloth billowing about) weighing the souls, one scale dipping down: a new meaning to “heavy soul.”

St. Michael Weighing the Souls, from The Last Judgement, C.1445-50

*

BLASPHEMY: NOT MISSING THE MISSING GOD

I see, or rather read, more and more “blasphemy.” My father had nothing but contempt for the catholic church, but in childhood I didn’t consider it blasphemy, the church being a flawed human institution, a fear-of-hell-based substitute for real holiness. So what if priests had “relations” (I didn’t even know what the word meant).

But then, when I was ten or so, my mother saw my anguish, guessed that it was over sin and hell, and said, out of the blue, “There is no hell. God wouldn’t be so cruel.” BLASPHEMY! I winced with horror: hell was the very foundation of sacred teachings, and now my mother, a blasphemer, was going straight to hell for sure.

Then at 14, it was my turn. After the insight that the religion that had been forced on me was just another mythology, still half-believing but having decided that a cruel god like that did not deserve worship, I said in my mind, “If god exists, let him strike me with lightning.” And waited, utterly terrified. I’ll never forget those five minutes of terror. I stood in one spot -- I vaguely remember pavement and trees, the cooing of pigeons -- I literally could not move, paralyzed with fear. I was waiting for that lightning (it wasn’t even a stormy day, but that did not matter to the part of me that still believed; the laws of nature were irrelevant; I had blasphemed and would be punished).

Finally I unfroze and continued walking to wherever I was going — maybe to the nearest kiosk to buy the newspaper for my blaspheming parents.

Many years later, in the less Catholic-repressed US, I had a boyfriend who several times called god as asshole. In spite of the lapse of time I still experienced shock. That was before the “new atheism." Now “blasphemy” is nothing special. If anything, it’s ridiculous, given that someone is insulting a fictitious character. If a modern reader calls Achilles an asshole, that's just literary criticism.

But the awareness that blasphemy was once punishable by burning at the stake is always with me. The clergy understood that in the absence of divine punishment, they had to be the executioners. Recently I was thinking about capital punishment for blasphemy in some Islamic countries (unbelief falls under the category of blasphemy). It struck me that such punishment itself constituted blasphemy, a lack of faith that god himself would exact revenge. Punishment simply could not be left in god’s hands! And, come to think of it, nothing could be left in god’s invisible hands. The most religious countries seem to have the least faith.

*

. . . and we were taught that god had unlimited powers, down to reading every thought in our head (even if we are wearing a helmet).

But this meme is more than facile satire. Jimmy Bakker has accidentally revealed the assumptions of the Fundamentalist clergy: You can't trust God to do the "right thing." You have to do it for him.

*

"THE POWER OF PRAYER"

There's an overlooked power to prayer that could help explain why people engage in this repetitive recitation of words that in any other situation would strike us as perverse. I mean, imagine if you ended up in conversation with someone who talked to you like they were praying to whatever. Pop-tarts or Cancun, God or Teslas. You'd think they were weird.

Prayer makes people feel good about themselves. They feel virtuous and humble. It's the buzz of posturing as a pious saint. As such it's a kind of moral mental masturbation.

I have nothing against that kind of moral mental masturbation. I think humans need it. I just don't think it's a whole other ballgame from sexual masturbation, which I also think is useful. Close your eyes and picture yourself either a moral or a sexual studmuffin. Harmless so long as afterward, you remember that you're just a human, neither saint nor studmuffin. ~ Jeremy Sherman

Oriana:

I find it wonderful how Jeremy subverted the usual meaning of that very common phrase, "the power of prayer."

I also think that praying gives the devotees of prayers the illusion of doing something useful, either for themselves or for others, when in fact they are doing absolutely nothing to help. When you have no intention to send money or to volunteer your time, you can always say, "I'm sending my prayers."

Jeremy Sherman:

*

WHY SOME PEOPLE RESIST MASKS AND VACCINES; THE BOOK ON THE PSYCHOLOGY OF PANDEMICS THAT TURNED OUT TO BE PROPHETIC

~ In October 2019, a month or so before Covid-19 began to spread from the industrial Chinese city of Wuhan, Steven Taylor, an Australian psychologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, published what would turn out to be a remarkably prophetic book, The Psychology of Pandemics.

Even his publishers had doubts about its relevance and market potential. But in the 22 months since, the book has become like a Lonely Planet guide to the pandemic, passed around and marked up like waypoints along a new and dreadful global health journey.

Taylor’s book, as its foreword points out, is a picture of “how human factors impact the spreading of disease and emotional disturbance”. The stops along the way include prejudices, the role of the media, attitudes to vaccinations, how society manages rumors, and the psychology of conspiracy theories.

The western world, with its enviable access to healthcare compared with much of the planet, is approximately at Chapter 10 in this journey: improving vaccine adherence. “Vaccine hesitancy doesn’t really get at the motivational roots for why people don’t want to get vaccinated,” Taylor told the Guardian.

CDC data showing that urban and rural rates of Covid-19 transmission closely shadow each other, and broad availability of vaccines across much of the western world, suggests denser psychological complexities around “hesitancy” than described by political or economic orthodoxies to explain why 90 million adult Americans remain unprotected by any vaccine.

A preferable term, Taylor writes, and one that has been used by psychologists for close to 60 years, is psychological reactance – a motivational response to “rules, regulation, or attempts at persuasion that are perceived as threatening to one’s autonomy and freedom of choice”.

Despite this, Taylor says that what people say about vaccination is often different from what they do, and studies before vaccines were released predicted a lower take-up than what has actually taken place when faced with a lethal pandemic. That, in many ways, is an optimistic sign, as are signs that vaccination take-up is again rising as the Delta variant surges, especially among unvaccinated populations.

What is clear, Taylor says, is that anger directed politically or personally toward vaccinate-hesitant groups is likely to be counterproductive, especially when available vaccines are both overwhelmingly safe and highly effective.

“Psychological reactance has been an issue around any public health guidance, whether that’s increasing the intake of more fruit and vegetables, good dental hygiene or vaccinations and masks,” Taylor said. “The you’re-not-the-boss-of-me kind of response is seen particularly in people raised in cultures that take pride in freedom and individualism.”

Despite this, Taylor says that what people say about vaccination is often different from what they do, and studies before vaccines were released predicted a lower take-up than what has actually taken place when faced with a lethal pandemic. That, in many ways, is an optimistic sign, as are signs that vaccination take-up is again rising as the Delta variant surges, especially among unvaccinated populations.

“The anti-lockdown, anti-mask, anti-vax protests have been a lot more prevalent than they were 100 years ago, even if they were motivated for the same reasons,” he said.

One exception, Taylor says, is the prominence of conspiratorial thinking. “A lot of conspiracy theorists who had tended to communicate with one another emerged from their silos to promote their theories more widely and, I suppose, indoctrinated more people as a result of Covid-19.”

Taylor theorizes that with the Delta variant on the rise, any return to lockdown could trigger an exaggerated backlash and rebellion – part of the psychological phenomenon commonly known as pandemic fatigue.

Lockdowns, he says, are not a long-term strategy for managing pandemics. “They’re a necessary evil but if we have another wave when people have just got a taste of freedom it’s going to demoralize people and be bad for mental health,” he said.

By the same token, people’s desire to get back to pre-pandemic life doesn’t speak to health resilience any more than psychological reactance, he says.

“The consequence of people rushing out to socialize prematurely is part of the uncertainty, especially for people who see themselves as impervious or of robust health,” Taylor points out.

“We’re going to see recurrent outbreaks of Covid, but the desire to socialize is stronger than the fear of getting infected.” And that is psychology. ~

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/aug/19/book-psychology-pandemics-steven-taylor?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

Parents are cursed with the phenomenon of psychological reactance in their children, especially adolescents. The basic attitude is "I won't let you boss me around." The folk wisdom calls it "cutting off your nose to spite your face."

You can also encounter psychological reactance in addicts of all sorts, e.g. in alcoholics who insist they have a constitutional right to drink and/or kill themselves if they so please.

Still, even with 90 million adults remaining unvaccinated, it's interesting that earlier studies predicted an even greater rejection of vaccines.

My own experience with the vaccine was amazing (at least to myself). I chose the J&J vaccine so I'd be sick afterwards only once. My self image of myself was as somebody rather sickly – after all, I am officially handicapped since after my knee replacement surgery I need to use a walker (and have not committed suicide only thanks to methyl salicylate, the main ingredient in Bengay and a miracle drug for my chronic knee pain; it works for migraines too). Thus, I expected severe side effects.

To my astonishment, there were . . . none. Tiny discomfort at the injection site was gone within minutes. The day passed, then another – and nothing. Did I really get the vaccine – or perhaps Costco gave me an injection of saline instead? I realized that wasn't likely – so that means I did as well as those various people (chiefly men) who triumphantly reported no side effects on social media. And the self-image as a "sicko" that was sold to me by my primary physician began to slightly fade away . . .

Lilith:

Thanks for the word reactance. I think it’s true we get energy from rebelling against what experts advise us to do. But it’s childish and self-destructive energy. If I decided not to floss my teeth tonight, I imagine I’d get a kick out of that decision. But what a stupid kick.

Oriana:

Sometimes I get a kick out of not buying things — in spite of the implicit pressure that to be a good citizen you should also be a super-consumer, to keep the economy going. I like old-fashioned thrift. And I love to say “Hah-hah!” to the whole advertising industry. No, I won’t buy all the stupid junk you want me to buy, and you can't make me, hah-hah!

On the other hand, this may not be a pure case of reactance since buying less (have you heard of the “Buy Nothing” movement?) helps protect the environment. Minimalist consumers get to feel virtuous.

Mainly, yes, reactance is frequent in children and adolescents — they don’t want to be “bossed around” and may do foolish things just to spite parents. Another highly reactant group is alcoholics and other addicts.

On the whole, it's probably unavoidable that putting pressure on anyone will result in reactance. That's why rewards and incentives work better.

*

MICROBIOME AND DENTAL CAVITIES

~ Our dental health changed with our diets. Ancient humans and their hominin ancestors really didn’t have much of a problem with cavities. Unhappy smiles became more common only after the advent of farming led to humans eating a lot more carbs — a shift that went even further following the widespread availability of refined flour and sugar in the 19th century.

But in the past decade or so, scientists sequenced the DNA from ancient dental plaque and figured out that something else in our mouths was changing at the same time as our dental health. Turns out, there are specific strains of bacteria — streptococcus mutans, in particular — that are more common in mouths with cavities. And as human diets changed and cavities became more common, those bacteria started taking over our mouths. Our modern communities of oral bacteria are less diverse than our ancestors’ were, and they’re dominated by these cavity-causing strains.

Increasingly, scientists are thinking of cavities as a microbiome problem. The advice you got as a kid — brush your teeth, floss, eat less candy — is still important. But it’s becoming more clear that the types of bacteria inhabiting your mouth matter, too. Some people do all the oral hygiene stuff right and still get cavities because of the bacteria living in their mouths. Which presents a question: If the types of bacteria in your mouth can make you more prone to cavities, could you fix your teeth by getting different bacteria?

I got interested in this question for selfish reasons: Namely, I am one of those people who brush and floss and eat a diet lower in sugar compared with the average American and still — still — end up with cavities on the regular. Obviously, this is unfair, but even worse, it looks like one of my two children might be in the same position. I wondered if I had caused my kid’s cavities by passing my bacteria on to her and if, somehow, I could solve the problem with … a spit transplant? (I dunno, man, you think wild things at the pediatric dentist.)

Mouth bacteria are connected to cavities because of the tiny creatures’ digestive process. “Cavity bugs,” as my daughters’ dentist calls them, feed on bits of sugar and carbs stuck to your teeth. The bacteria ferment those things, creating natural acids that start to dissolve the tooth enamel, similar to how water combines with carbon dioxide to dissolve limestone in a cave.

My fear that I had spread cavity-causing bacteria to my kid is, unfortunately, substantiated by science, said Robert Burne, a professor of oral biology at the University of Florida. “You can take an animal that naturally develops cavities and feed it a high-sugar diet, and it will get cavities. And if you house it with animals that seem to be naturally resistant to cavities, they will then develop cavities,” he said. Cavities, in other words, are a transmissible, infectious disease.

What’s more, Burne told me, research has shown that a caregiver’s susceptibility to cavities — be it a parent or a day care provider — can predict how likely a kid is to get cavities.

And transplanting the bacteria of a not-cavity-prone person to someone who’s cavity-impaired isn’t really an option. Rob Knight, director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation at the University of California, San Diego, was once approached by a dentist in Colorado who wanted his help with a study based on that very idea. “He had noticed that some of his patients tended to get cavities at very high rates, even though they were absolutely scrupulous about brushing and flossing, and other patients did basically nothing and they got no cavities at all. So he was hoping to do an oral microbiota transplant, essentially, by transferring saliva from people who did not get cavities to people who did get cavities,” Knight said. The dentist’s proposed mechanism? Hire attractive women with few cavities to kiss cavity-prone participants. The plan never made it past an institutional review board.

Now the basic idea here — to give people better oral health by changing their oral microbiome — isn’t a bad one, Knight said. But the problem (besides the whole bit with the beauty subjectivity and the kissing) is that scientists simply don’t know enough about the oral microbiome to guess whether a spit transplant would work, would work only temporarily or would make things worse. That’s because the connections between specific bacterial strains and cavities are merely correlations — nobody knows yet if one causes the other.

Studies comparing the oral microbiomes of people who have healthy teeth with people who don’t find more streptococcus mutans in the cavity-prone. However, as Knight explained, changing a kid’s microbiome does not necessarily mean changing whether that kid gets cavities. “We might just be seeing a side effect of something else,” he said. Does the bacteria cause the cavities, or are the bacteria and the cavities together a response to some other factor? Nobody knows.

On top of this, your oral microbiome isn’t static. It changes over the course of your life, over the course of the day and even from one part of your mouth to another, Knight said. What does that mean for the idea of changing the oral microbiome? Again, nobody knows. But it does suggest that the issue is more complicated than one that could be solved simply by kissing some strangers with low dental bills.

But there is some good news in all this. Scientists know a handful of surefire ways to make your oral microbiome healthier. Are you ready for this insider knowledge? OK, here goes: You have to brush twice a day, floss, use mouthwash and eat a diet low in sugars and refined carbohydrates. Yeah, the advice you were getting all along is also a form of biohacking. Those activities change the pH levels in your mouth, Burne told me, making an environment that is less acidic and more friendly to the kinds of bacteria that aren’t associated with cavity formation. Decreasing the acidity also helps promote remineralization — basically the process of your teeth fixing themselves. The opposite of this advice — eating a lot of sugar and not reliably cleaning your teeth — creates an environment that is more friendly to streptococcus mutans and its buddies. “It’s a [natural] selection process,” Burne said.

At some point in the future, researchers may well find out enough about the oral microbiome to start hacking it in a more high-tech way — a way that could address the plight of people who do the basics but still get less-than-stellar results. But despite the promises of a plethora of sketchy probiotic “supplements” on the market, we just aren’t there yet.

So the best thing to do is double down on the stuff you’ve already (hopefully) been doing. That is not, shall we say, what I wanted to hear. I wanted some easy solution that would improve my life and my child’s. But in the time it took to research and write this story, I stumbled upon her stash of empty candy wrappers. And that, at least, gives us a place to start making changes. Step one: Don’t give the cavity bugs a buffet.

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-people-who-brush-still-get-cavities/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

The obvious solution — until we have more specific data — is simply to eat fewer carbs. This creates a dilemma, since a lot of nutrients are present in “good carbs,” such as beets and sweet potatoes. But wait! there are vegetables like raw carrots that actually help clean your teeth. More on this below.

FOOD AND DRINKS THAT ARE GOOD FOR YOUR TEETH

WATER. Water helps wash away food particles and keeps your saliva levels high.

MILK, CHEESE, AND YOGURT

Cheese is one of the best foods for healthy teeth for a number of reasons. First, it is low in sugar and high in calcium. It contains casein, which is a protein that is particularly useful for fortifying tooth enamel. Cheese is high in calcium, which is important for maintaining bone density. Cheese is also high in phosphate content, which helps balance pH levels in the mouth, which helps to preserve tooth enamel. Another great reason cheese is a friend to our teeth is that chewing it increases saliva production, which helps to wash away bacteria in the mouth.

[Oriana: Gouda cheese in particular is rich in Vitamin K2, which helps prevent cavities]

Aside from water, milk is the best drink when it comes to your teeth. It’s rich in calcium and other important elements. Milk, like cheese, also lowers the acid levels in the mouth, which helps fighting tooth decay.

Yogurt is packed with calcium and probiotics that protect you against cavities, gum disease and even bad breath.

CELERY, CARROTS, AND OTHER CRUNCHY VEGETABLES

Many vegetables are good for teeth because they require a lot of chewing to clean teeth surfaces. Crunchy, firm foods that contain lots of water are great natural teeth cleaners because they stimulate the flow of saliva, which helps to scrub away food particles and bacteria. These fresh crunchy veggies are usually also packed with some of the most important minerals and vitamins for your mouth.

Celery is probably the closest thing to nature’s dental floss. The crunchy and fibrous texture makes for a very effective natural teeth cleaner.

In addition to packing lots of nutrients, carrots are also one of the great cavity-fighting vegetables. Carrots contain lots of vitamin C, calcium and keratins which all offer dental benefits. Eating fresh carrots also helps to clean your teeth – like a natural toothbrush. When combined with your saliva, carrots help to wash away stain-causing bacteria and food particles.

In addition to packing lots of nutrients, carrots are also one of the great cavity-fighting vegetables. Carrots contain lots of vitamin C, calcium and keratins which all offer dental benefits. Eating fresh carrots also helps to clean your teeth – like a natural toothbrush. When combined with your saliva, carrots help to wash away stain-causing bacteria and food particles.

LEAFY GREENS

Super healthy, leafy greens are rich in calcium, folic acid and lots of important vitamins and minerals that your teeth and gums love. Crunchy fresh greens in salads and sandwiches also help in cleaning your teeth.

APPLES AND PEARS

Will an apple a day keep the dentist away? Maybe not, but it will certainly help. Eating apples or other hard fibrous fruits can help clean your teeth and increases salivation, which can neutralize the citric and malic acids left behind in your mouth. And while sugary apple juice may contribute to tooth decay, fresh apples are less likely to cause problems. This is because chewing the fibrous texture of apples stimulates your gums, further reducing cavity-causing bacteria and increasing saliva flow.

Unlike many acidic fruits, raw pears are good at neutralizing acids in your mouth that cause decay.

NUTS

Nuts are full of health benefits for your teeth. They are packed with tons of important elements like calcium and phosphorus. Especially beneficial are almonds, Brazil nuts and cashews, which help to fight bacteria that lead to tooth decay. For instance, peanuts are a great source of calcium and vitamin D, and almonds offer good amounts of calcium, which is beneficial to teeth and gums. Cashews are known to stimulate saliva and walnuts contain everything from fiber, folic acid, iron, thiamine, magnesium, iron, niacin, vitamin E, vitamin B6, potassium and zinc.

MEATS AND FATTY FISH

Most meats offer some of the most important nutrients mentioned above, and chewing meat produces saliva. And more saliva is good, because it decreases acidity in your mouth and washes away particles of food that lead to decay. Red meat and even organ meats are especially beneficial.

Fatty fish (like salmon), and tofu are loaded with phosphorus, an important mineral for protecting tooth enamel.

TEA AND COFFEE

Heard of polyphenols? Polyphenols are a category of chemicals that naturally occur in many of the foods and drinks we consume, including teas and coffee. They offer several health benefits, including their role as antioxidants, which can combat cell damage, as well as their effects on reducing inflammation and helping to fight cancer. Green and black teas are rich in polyphenols and offers a number of other health benefits.

RAISINS (?!)

There is a long-held perception that raisins promote cavities. However, one study suggests that compounds in raisins may actually fight tooth decay. One of the five phytochemicals the study identified in raisins is oleanolic acid. In the study, oleanolic acid inhibited the growth of two species of oral bacteria: Streptococcus mutans, which causes cavities, and Porphyromonas gingivalis, which causes periodontal disease.

STRAWBERRIES

We all know that vitamin C is good for the body because of its antioxidant properties and for growth and repair of tissues in all parts of your body. This also true for teeth. The collagen in the dentin of teeth depends on vitamin C for maintaining its strength and structure through synthesis.

Strawberries are packed with Vitamin C, antioxidants and also malic acid, which could even naturally whiten your teeth. Be sure your diet includes fresh fruits and veggies rich in vitamin C, such as apples, pears, strawberries, pineapples, tomatoes, broccoli, bell peppers, and cucumbers.

GARLIC AND ONIONS

Okay, maybe garlic isn’t a go-to for fresh breath. However, the allicin that is contained in garlic has strong antimicrobial properties, which can help fight tooth decay and especially periodontal disease.

Again, maybe not the first choice for fresh breath. When eaten raw, onions have powerful antibacterial properties especially against some of the bacteria that causes cavities and gum disease.

SHIITAKE MUSHROOMS

These mushrooms pack a bold flavor, and offer anti-microbial properties for fighting tooth decay. Researchers found that shiitake mushrooms contain a poly-saccharide called

lentinan, which prevents the growth of bacteria in the mouth.

ABOVE ALL:

Drink plenty of water during and after meals to help wash away sugars and acids left from snacks and meals.

https://dentistry.uic.edu/news-stories/the-best-foods-for-a-healthy-smile-and-whole-body/

Oriana:

A fascinating article — I had no idea about shiitake, for instance!

I started munching on raw carrots while reading this — so simple. Good for your teeth and your digestion ("Disease starts in the gut" is true in many cases).

*

ending on beauty:

Last night your memory stole into my heart

the way spring steals into a desolate field

Or the breeze spills all its tenderness on a parched desert

Or the infirm one suddenly feels well-- for no reason

~ Faiz Ahmed Faiz, tr from Urdu: Shadab Zeest Hashmi

(photo: Doug Chesser)

No comments:

Post a Comment