*

ASHES AND DIAMONDS

When life is over, burnt to ash,

Under the ashes will remain

Victory’s dawn, a starry diamond.

~ Cyprian Norwid

You was born under an unlucky star,

a fake Gypsy declared

at my half-price palm reading.

On her neon-lit windowsill,

a row of porcelain Madonnas

and a Jesus with a light bulb heart.

Do you believe in God?

the Gypsy pressed. “I believe

in a higher wisdom,” I stammered.

a comet of ill omen.

starry scatter of the poisonous blossoms.

You don’t even know what love is,

the fake Gypsy wailed.

But perhaps I did.

My star the color of ash. But underneath

that death, immortal

diamond.

~ Oriana

Thinking about the best-remembered stage of life, I'd have to agree with the view that the late teens are most vividly remembered. Then it was my late twenties. Both the happiest year of my life and the worst. And in fact I don't remember my early twenties as well as my late twenties, the years of perdition, the years I don't really want to remember. My ideas about America, love, marriage, and career all went belly up. But I did learn a lot the hard way.

And I remember my thirties more vividly than my early twenties, which seem a strange oasis of college routine and housewifely routine on top of that. As for my thirties, then it's again the late thirties -- my creative blossoming, the sense of having "found my way in life." Not for long. But let me stop here. My last year in Warsaw and my last year in Los Angeles -- those were the best years of my life, the years of the most intense development . . . and happiness. I'm so glad that I can point to at least two years in my life and say, "I was happy then." I don't mean contentment, much as I treasure contentment; I mean joy.

Remembering that I was happy feels like a triumph to me — a triumph over depression. When I was depressed, I had no access to happy memories. But I did remember the fake Gypsy’s words, “You was born under an unlucky star. You don’t even know what love is.”

She was wrong. But if there is a pattern in my life — a trinity — then perhaps the third happiest year of my life will be the last one. Why not go out on a high note? Of course I realize that we don’t have any control over this. The Greeks wisely thought that even the gods were subject to Fate.

REMEMBERING 9/11

~ I was teaching a morning freshman-preceptorial class at Union College in Schenectady, NY. "Hamlet" as a hall of mirrors. A student who was always late to class and usually quite blasé about it, burst in, looking rather wild and disheveled and out of breath. "I just watched a plane fly into World Trade Center on TV," he blurted out.

"That's a really original one, haven't heard this before," I told him, and the class snickered.

"No, seriously," he said. "Really. A real plane."

A few minutes later, there came the clattering sound of manifold running footsteps down the Humanities building hallway outside, and a stern voice announced over the PA system that due to an emergency situation, classes were being canceled and students and faculty were to leave campus immediately.

Shortly thereafter, as I drove the seven-minute distance along Union Street toward my house in the Stockade neighborhood, nothing seemed out of the ordinary, everything was exactly the same as always: the sun was shining, an unhurried construction crew was jackhammering the pavement, and on the radio Shaggy was insisting "It Wasn't Me.”

Then I got home, and the world has never been the same since. ~ Mikhail Iossel

Oriana:

That was the day I discovered that I really was an American. The sense of a psychic wound was very deep. I could no longer distance myself, thinking that I was not a member of this culture, but a European — nor did I try to. Later that day I had to go to Costco to pick up a prescription. The place seemed almost dead. There was a minimum of talking, in low voices. Everyone looked somber and sad, as if mourning. Perhaps we should have let ourselves cry, but it was too early for that. We were still in emotional shock.

I was finally able to cry almost a month later, listening to Mozart's Requiem. It became my requiem for the lost lives — but also for the lost hope for a new century of peace and flourishing.

Plunging into war in the Middle East was the worst possible solution, I felt. That was exactly what Bin Laden wanted — America showing its worst side. But the government had no inspiring vision for recovery. George W. Bush told the shocked and grieving nation to “show your faith in America — go shopping.”

Only Mozart came to my rescue, be it with some delay. Only Mozart.

*

9/11’S DOUBLE TRAGEDY: A MISSING LEGACY (NEW YORK TIMES)

~ It isn’t hard to imagine how Bush might have responded to Sept. 11 with the kind of domestic mobilization of previous wars. He could have rallied the country to end its reliance on Middle Eastern oil, a reliance that both financed radical American enemies and kept the U.S. enmeshed in the region. While attacking Al Qaeda militarily, Bush also could have called for enormous investments in solar energy, wind energy, nuclear power and natural gas. It could have been transformative, for the economy, the climate and Bush’s historical standing.

Some wars have left clear legacies of progress toward freedom — like the anti-colonization movement and the flowering of European democracy that followed World War II. The post-9/11 wars have not. If anything, the world has arguably become less democratic in recent years.

Twenty years after Sept. 11, the attacks seem likely to be remembered as a double tragedy. There were the tangible horrors: The attacks on that day killed almost 3,000 people, and the ensuing wars killed hundreds of thousands more. And there is the haunting question that lingers: Out of the trauma, did the country manage to create a better future?

(The New York Times’s newsletter, 9-11-21)

*

~ "Jules, this is Brian. Listen, I'm on an airplane that's been hijacked. If things don't go well, and it's not looking good, I just want you to know I absolutely love you.”

~ Brian Sweeney, a Navy pilot, died on one of the hijacked planes that hit the Twin Towers

Let us remember the human side: the passengers on the hijacked planes who managed to call home and whose last words were “I love you.”

*

The 9/11 Tear Drop Memorial, gift from Russia

ČAPEK AND ZAMYATIN: EARLY VISIONARIES OF DYSTOPIA

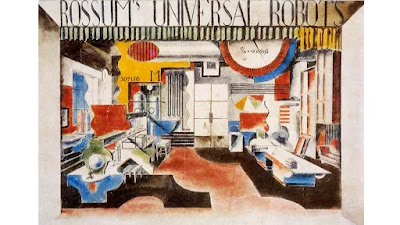

~ One day in 1920, the Czech writer Karel Čapek sought the advice of his older brother Josef, a painter. Karel was writing a play about artificial workers but he was struggling for a name. "I'd call them laborators, but it seems to me somewhat stilted," he told Josef, who was hard at work on a canvas. "Call them robots then," replied Josef, a paintbrush in his mouth. At the same time in Petrograd (formerly St Petersburg), a Russian writer named Yevgeny Zamyatin was writing a novel whose hi-tech future dictatorship would eventually prove as influential as Čapek's robots.

Both works are celebrating a joint centenary, albeit a slippery one. Čapek (pronounced Chap-ek) published his play, RUR, in 1920 but it wasn't performed for the first time until January 1921. And although Zamyatin submitted the manuscript of his novel, We, in 1921, it was mostly written earlier and published later. Nonetheless, 1921 has become their shared birth date and thus the year that gave us both the robot and the mechanized dystopia – two concepts of which, it seems, we will never tire. As Čapek wrote in 1920, "Some of the future can always be read in the palms of the present”.

RUR stands for Rossum's Universal Robots, Rossum being a pun on the Czech word rozum, or "reason", and Robota meaning “serfdom" [O: the literal meaning is “menial work”]. Čapek's "comedy, partly of science, partly of truth" is a Frankenstein story for the age of mass production. Rossum's robots are more akin to the replicants in Bladerunner than to C-3PO or WALL-E: bioengineered artificial humans, almost indistinguishable from the real thing, who do most of the world's labor so that their masters can enjoy a post-work utopia. Inevitably, the plan goes awry. Humans grow lazy and infertile while the robots plot genocidal revolution. "We have made machines, not people, the measure of the human order," Čapek later wrote, "but this is not the machines' fault, it is ours.”

RUR was an immediate international success; by 1923 it had been translated into 30 languages, and staged in the West End and on Broadway. Remarkably, it became both the first radio play aired by the BBC, in 1927, and the world's first televised science-fiction drama, in 1938. Fond allusions to RUR have since appeared in Star Trek, Doctor Who and Futurama.

We is an equally important piece of work. A number of writers, including Jack London and HG Wells, had previously attempted anti-utopian novels but Zamyatin was the first to combine a coherent concept with a satisfying narrative to create something like a blueprint for dystopia. We takes place in the ultra-rational One State, where everything from work to sex to music is mathematically regimented, uniformed "ciphers" have numbers rather than names, and everybody is surveilled by the Guardians, under the command of an enigmatic dictator known as the Benefactor. The protagonist, D-530, is a drab and dutiful rocketship engineer who is seduced into an underground revolutionary movement by a charismatic female dissident called I-330. After a great deal of mayhem, the rebels are routed, I-330 executed and D-530 lobotomized into total obedience. Zamyatin insisted on the freedom to be imperfect, irrational and sometimes unhappy, which is to say human.

If that plot sounds a little like 1984, then that's because George Orwell admired We so much that he attempted to get a proper English translation published in the 1940s, and is largely responsible for its modern reputation. Although he wrote the outline for his novel before he knew that We existed, it clearly influenced him on the level of narrative and character. Its influence is also obvious in Ayn Rand's Anthem, George Lucas's THX 1138, Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano and (to more cheerful effect) The Lego Movie.

The two books' combined legacy is incalculable – if you have had any experience with science fiction, you will probably have imbibed some trace elements of RUR and We. Far less well-known, however, are the parallel lives of the men who created them. Čapek and Zamyatin were born six years apart, and died within two years of each other, shortly before World War Two. Both were free thinkers of extraordinary intelligence and courage who wrote plays, novels, stories, translations and journalism. Both were anglophiles with a particular affection for HG Wells. Both were extraordinarily alert to the dangers of dogma, tribalism and the corruption of language in the inter-war years.

Quick to identify the threat of totalitarianism, they were both ultimately crushed by it. Both their lives were changed by their most famous works but in radically divergent ways: RUR made Čapek a literary superstar, while We made Zamyatin a pariah. You can't really understand their vast gifts to the popular imagination without knowing a little about their lives and why they were driven to write fables about the horrors that technology can unleash when it converges with the worst of human nature.

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin was born in 1884 in the Russian town of Lebedyan, 400km (249 miles) south of Moscow. His father was an Orthodox priest and his mother a musician. Zamyatin graduated from school in 1902 with a gold medal for flawless grades and went to study naval engineering at the St Petersburg Polytechnic Institute, where he became a Bolshevik. He was a questing, combative soul who invariably chose the hardest path. "I've always sought novelty, variety, dangers – otherwise [life] would all have seemed too cold, too empty," he told his future wife Lyudmila Nikolaevna in 1906.

Karel Čapek was born in 1890 in a village in northern Bohemia, which then belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A childhood bout of scarlet fever left him with Bechterew's disease, a form of arthritis which gave him chronic spinal pain, headaches and a stooped posture. He walked with a cane and was unable to turn his head. His brain, however, was formidable. In a 1932 radio talk called How I Have Come to Be What I Am, he wrote that he had inherited his pragmatism and intellectual curiosity from his father, a country doctor, and his "romantic sensibility" and "fantasticality" from his mother. Despite being expelled from high school in 1905 for belonging to a clandestine pro-independence society, he went on to study literature in Berlin and Paris.

Around the same time that Čapek was being expelled, Zamyatin was being arrested for the first time by the Tsar's secret police for belonging to a Bolshevik cell. He was held in solitary confinement for three months, an experience that inspired his first short story, Alone. When he was arrested again in 1911, and exiled from the city, he began writing novels. "If I mean anything in Russian literature, I owe it all to the Petersburg Secret Police," he quipped in an autobiographical sketch, neglecting to mention that this was also when he began suffering from depression and chronic colitis.

When World War One broke out, Čapek was exempted from military service on account of his condition and continued his studies, graduating from the University of Prague with a doctorate of philosophy in 1915. Zamyatin, however, had valuable engineering skills, so the Russian government dispatched him to Newcastle in 1916, where he designed icebreakers for the Russian navy. Like D-530, he was a shipbuilder. Zamyatin's gentlemanly bearing, dry wit and emotional reserve led friends to nickname him "the Englishman". He returned to St Petersburg just in time for the revolution.

Fictional revolutions

The events of October 1917 loom over both We and RUR. The fictional revolutions may be opposites – Čapek's robots overthrow their human masters while Zamyatin's rebels are crushed by the technological state – but in both cases the machines win. Zamyatin was warning of Russia's potential to replace one tyranny with another but, like Čapek, he was also satirizing capitalist innovations that made people "machinelike," chiefly the management science of Frederick Winslow Taylor and the assembly lines of Henry Ford.

As he explained in a 1932 interview: "This novel is a warning against the two-fold danger which threatens humanity: the hypertrophic power of the machines and the hypertrophic power of the State." The third context was the aftermath of the first mechanized global conflict, whose casualties included pre-war optimism about technological progress. A war fought with tanks, airplanes and poison gas, Zamyatin wrote, reduced man to "a number, a cipher”.

With the defeat of Austro-Hungary, Czechoslovakia became an independent nation in October 1918. "It was a revolution in which not even a drop of blood was spilled, in which not even a window was broken," Čapek would write proudly on its 20th anniversary. He became his young country's first literary celebrity. During 1920 and 1921 alone, as well as writing RUR, he started a column for the progressive People's Newspaper, became a writer-director at Prague's Vinohrady Theatre, and launched a weekly intellectual salon in his garden whose attendees became known as the "Friday Men". He also fell in love with a 17-year-old actress named Olga Scheinpflugová, who he eventually married in 1935. His letters to Olga revealed a shy, insecure side (he once attended a performance of RUR with the French writer Romain Rolland and spent the whole show apologizing for its flaws) but on the page he radiated confidence and wit. Zamyatin likewise concealed his vulnerabilities beneath a glossy shell of charm and professionalism.

While Čapek was revelling in his country's new dawn of freedom and democracy, Zamyatin was writing as early as 1918 that the revolution "has not escaped the general rule on becoming victorious: it has turned philistine… And what every philistine hates most of all is the rebel who dares to think differently from him". Blending politics, philosophy and physics, he warned in a string of brilliant essays that revolutionary energy was freezing into something static and oppressive, and argued that the only cure was permanent revolution. "Revolutions are infinite," I-330 tells D-530 in We. Zamyatin's heretical philosophy inevitably made him unpopular with the new regime. He was denounced as "an internal emigré" by Trotsky himself and twice arrested by the secret police – in 1919 and 1922. "It's amusing, isnt it?" he wrote to the critic Alexsandr Voronsky. "That I was imprisoned then as a Bolshevik, and now I'm imprisoned by the Bolsheviks.”

He would have had an even harder time without the protection of Maxim Gorky, the literary giant who carved out a liminal space for those vulnerable writers who supported the revolution but were not loyal communists. Hard-working and well-liked, Zamyatin joined Gorky's publishing house World Literature and personally oversaw the publication of translations of books by HG Wells, whom he met in Petrograd in 1920. Čapek also met Wells, on a visit to England in 1924, and his "remarkable philosophic-fantastic novel" The Absolute at Large (1922) was praised by Zamyatin as an example of the influence of Wells's "mechanical, chemical fairy tales". Thanks to the author of The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, early science fiction was an inherently political playground for ideas about how the world was, or could be.

While Zamyatin dazzled and goaded his readers with radical ideas and angular, ultra-modern prose, Čapek sought to befriend his. Claiming "I am interested in everything that exists," he wrote more than 3,000 articles, as well as novels, stories, plays, screenplays and children's books. His short columns, or feuilletons, read like precursors of Orwell in their chatty, companionable tone; their witty aphorisms; their celebration of ordinary lives and the natural world; their criticism of snobbery and elitism; their hatred of dehumanizing abstractions; and their fascination with language. A dozen years before Orwell's landmark essay Politics and the English Language, Čapek was describing the relationship between bad writing and dangerous politics: "The cliché blurs the difference between truth and untruth. If it were not for clichés, there wouldn't be demagogues and public lies, and it wouldn't be so easy to play politics, starting with rhetoric and ending with genocide." He was, however, capable of greater kindness and optimism about human nature than Orwell. "I believe that seeing is great wisdom," he wrote in 1920, "and that it's more beneficial to see a lot than to judge”.

Čapek was a close friend of Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia's first president, whose government he saw as a humane, democratic middle way between the rising extremes of communism and fascism. In 1924, he wrote an essay called Why Am I Not a Communist? His answer was that communists weren't really interested in people as individuals, only as revolutionary masses. "Hatred, lack of knowledge, fundamental distrust, these are the psychic world of communism," he wrote. By contrast, "I count myself among the idiots who like man because he is human". He believed that people should be "revolutionary like atoms", and change the world by first changing themselves.

The essay infuriated Czech communists but they were not in charge. For Zamyatin, living in a one-party state, such a declaration of political independence was perilous. As Stalin succeeded Lenin, his letters were censored, his articles were rejected and the periodicals and publishers he worked for were shut down. In 1925, he was informed that We was, as he suspected, officially unpublishable in Russia. "I often encounter difficulties, because I'm an unbending and self-willed man," he told a friend. "And that’s how I shall remain”.

In 1929, his enemies used the unlicensed publication of Russian-language extracts from We by Russian emigrés in Prague as an excuse to condemn Zamyatin for disseminating "anti-Soviet" ideas, and thus to pass what he called a literary "death sentence". In 1931, he won permission from Stalin to leave Russia forever but his life in exile in Paris with Lyudmila failed to revive him as a writer. After a few frustrating years consumed by an unfinished novel and mostly unproduced screenplays, he died of heart failure on 10 March, 1937.

Čapek, conversely, went from strength to strength. He was nominated more than once for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and asked by Wells to become the president of the international writers' group PEN. Yet his success was clouded by his awareness of Hitler's designs on his homeland, and he became one of Czechoslovakia's most prominent anti-fascists. "All of us have begun to feel that there is something odd and insoluble about the conflicts between world-views, generations, political principles, and whatever else divides us," he wrote in 1934.

Čapek revisited RUR's themes of hubris, greed and conflict in War with the Newts (1936), a spectacularly inventive satire on nationalism, colonialism, militarism and racism. When humans discover a race of intelligent newts living in the sea, they put them to work as slaves, but the fast-evolving amphibians become too numerous to control and demand more living space. Under the Hitleresque command of Chief Salamander, the newts flood and annex vast swathes of land. Čapek explains in War with the Newts how the world will end: "No cosmic catastrophe, nothing but state, official, economic and other causes… we are all responsible for it". There is a similar anti-fascist message in his 1937 play The White Plague, in which a pro-war mob destroys the only antidote to a pandemic, resulting in a kind of national suicide.

In War with the Newts, the European powers sell out China to the newts in the hope of saving themselves. In October 1938, the Munich Agreement between Britain, France and Germany did much the same to Čapek's country. "My world has died," he told his friend Ferdinand Peroutka. "I no longer have any reason to write". Despite denunciations and death threats from the right, he refused to abandon the country he loved. The Gestapo placed him on its hitlist of people to arrest after the invasion of Czechoslovakia.

Yet when the Nazis arrived at his door in March 1939, they found that they were too late. While working in his beloved garden, Čapek had caught a cold which developed into double pneumonia and he died on Christmas Day, 1938. "As a doctor I know that he died because in those days there was no antibiotics and sulfa drugs," said his friend Dr Karel Steinbach, "but those who say that Munich killed him also have a great deal of the truth". It's unlikely that he would have survived Nazi occupation. Among the Friday Men who died in concentration camps was Josef, who perished in Bergen-Belsen just days before it was liberated. An inscription on Karel's Prague tombstone reads: "Here would have been buried Josef Čapek, painter and poet. Grave far away.”

Čapek's writing career coincided almost precisely with the birth and death of independent Czechoslovakia; Zamyatin's extended from the last days of the Romanovs to Stalin's Great Terror. As members of that brave and tragic inter-war tribe of intellectuals who rejected fascism, communism and imperialism alike, they witnessed the crushing defeat of the values that they lived by. Ultimately, the only thing that exceeded their imaginations was their moral courage. Their lives were not blighted by robots or spaceships but by people who had surrendered something of their humanity to unforgiving ideologies. As one of Čapek's characters says in The Absolute at Large, "You know, the bigger the things a man believes in, the more fiercely he despises those who don't. And yet the greatest of all beliefs would be to believe in people”. ~

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210902-the-100-year-old-fiction-that-predicted-today?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Evgeni Zamyatin, a portrait by Boris Kustodiev, 1923

Oriana:

One can speak "truth to power" only when power is not too brutal. One couldn't speak truth to Hitler or Stalin.

*

CHINA’S “RECTIFICATION CAMPAIGN” AND “XI JINPING THOUGHT” — A GREAT LEAP BACKWARD?

~ The orders have been sudden, dramatic and often baffling. Last week, “American Idol”-style competitions and shows featuring men deemed too effeminate were banned by Chinese authorities. Days earlier, one of China’s wealthiest actresses, Zhao Wei, had her movies, television series and news mentions scrubbed from the Internet as if she had never existed.

Over the summer, China’s multibillion-dollar private education industry was decimated overnight by a ban on for-profit tutoring, while new regulations wiped more than $1 trillion from Chinese tech stocks since a peak in February. As China’s tech moguls compete to donate more to President Xi Jinping’s campaign against inequality, “Xi Jinping Thought” is taught in elementary schools, and foreign games and apps like Animal Crossing and Duolingo have been pulled from stores.

A dizzying regulatory crackdown unleashed by China’s government has spared almost no sector over the past few months. This sprawling “rectification” campaign — with such disparate targets as ride-hailing services, insurance, education and even the amount of time children can spend playing video games — is redrawing the boundaries of business and society in China as Xi prepares to take on a controversial third term in 2022.

“It’s striking and significant. This is clearly not a sector-by-sector rectification; this is an entire economic, industry and structural rectification,” said Jude Blanchette, who holds the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

At China’s national congress next fall, Xi is expected to retain his title as general secretary of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a move that would upset a decades-old system of term limits and leadership succession. To build momentum, he is pushing an agenda of tackling income inequality under the banner of “common prosperity,” a campaign that gives officials and companies rallying around the cause opportunity to show their loyalty before the reshuffle of party personnel.

Male Chinese celebrities known for their androgynous style have also become a threat in Beijing’s eyes. Last week, regulators ordered broadcasters to encourage “masculinity” and put a stop to “abnormal beauty standards” such as “niangpao,” a slur that translates to “sissy men.”

“The party does not feel comfortable with expressions of individualism that are in some ways transgressive to norms that it puts forward,” said Rana Mitter, a professor of modern Chinese history and politics at the University of Oxford. “The party-state makes it clear that it has the first and last word on what is permitted in mass culture.”

Internet users criticized the order against “sissy” culture as state-sponsored homophobia. “Sissy men will not harm the country, but prejudice and narrow thinking will,” said one comment that was censored on WeChat after getting more than 100,000 views.

Jo Tan, 33, an administrator at a test prep school in Changsha in Hunan province, said the limits on tutoring have done more harm than good. Her company has halved its head count and teachers must work longer hours.

“Students still have to compete to get into good schools and colleges, and many of us are now on the verge of being unemployed,” she said.

“Whoever came up with this policy probably never had to worry about their children’s education,” Tan said, adding that making high school and universities free would do more to promote equality in education.

Michael Shou, general manager of an on-demand English tutoring platform, said he expects more regulatory action in more sectors.

“I do believe we are seeing a profound transformation of society, especially given that the government has implemented definitive and strict regulatory measures in such a short amount of time and in so many different industries,” he said.

Xi’s crusade has left the country’s previously all-powerful tech titans, such as Alibaba’s Jack Ma and Tencent’s Pony Ma, in no doubt about who controls China’s future. But it has also alarmed investors.

Regulators on Wednesday summoned Tencent and Netease over their online gaming platforms, ordering the companies to eliminate content promoting “incorrect values” such as “money worship” and “sissy” culture. Both firms promised to “carefully study” and implement the orders.

The scope and velocity of the society-wide rectification has some worried China may be at the beginning of the kind of cultural and ideological upheaval that has brought the country to a standstill before.

Last week, an essay by a retired newspaper editor and blogger described the changes as a response to threats from the United States. “What these events tell us is that a monumental change is taking place in China, and that the economic, financial, cultural, and political spheres are undergoing a profound transformation — or, one could say, a profound revolution,” wrote Li Guangman.

The essay, picked up by China’s state media outlets, prompted comparisons with a 1965 article that launched China’s chaotic decade-long Cultural Revolution, and left even some in the party establishment worried.

Differences over the article may be a sign of deeper dispute within the party, according to Yawei Liu, a senior adviser focusing on China at the Carter Center in Atlanta, who wrote that such disagreement indicates “raging debate inside the CCP on the merits of reform and opening up, on where China is today . . . and about what kind of nation China wants to become.”

Residents expect more measures to come, targeting regular life as well as other sectors. While the Ministry of Culture and Tourism is preparing a ban on karaoke songs deemed out of line with “the core values of socialism,” city officials are regulating dancing in China’s parks, a popular pastime for retirees. In an editorial in the People’s Daily last week, the vice chairman of the Chinese Film Association called on filmmakers to make more patriotic films and “further promote” Xi Jinping Thought. ~

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-crackdown-tech-celebrities-xi/2021/09/09/b4c2409c-0c66-11ec-a7c8-61bb7b3bf628_story.html?utm_source=pocket-newtab Xi Jinping celebrating the centenary of Chinese Communist Party

Xi Jinping celebrating the centenary of Chinese Communist Party

It seems that in many ways the world has become a worse place since 9/11/2001. Twenty years already . . . As usual, an increase in fear has produced mostly negative developments, from the rise of new repressive dictatorships and extremist movements, to disquieting developments of the sort I just learned about — Facebook has banned the iconic photo showing a man falling to his death from one of the World Center towers. It’s a grisly photo, but, as with the Triangle Fire, it makes the suffering real. It helps us remember and mourn.

In mid-twentieth century, people kept wondering about the wonders that the year 2000 would bring. Space exploration would be well underway, cancer and other diseases long conquered, famine and genocide only history. Then, in 2001, on 9/11, we learned the hard way about the rise of religious fanaticism. It’s the old modernists versus fundamentalist struggle, but with a level of hardened hatred, made worse by the echo chambers of social media, that has led to ominous comparisons with the unrest and rise of fascism a hundred years ago.

The stock market is booming, and some are talking about the new “Roaring Twenties.” But we know how the original Roaring Twenties ended. History doesn’t repeat itself exactly the same way, and we can point with pride to how, thanks to progress in science and medicine, our pandemic resulted in only a fraction of the deaths compared with the horrific toll of the 1918 flu pandemic. While doom-sayer regard the coming stock-market crash as inevitable, the more optimistic thinkers point out that now we know how to prevent another Great Depression. But the climate catastrophe looms over us, a new threat of profound disruption.

Yet that’s how civilization has always unfolded itself, with periods of blossoming between catastrophes. And that’s what we see on a small scale in individual lives: blossoming, then adversity, then, with luck, another resurrection. Just as we learn that democracy is fragile, so we see that productivity and good health are fragile also. “It will work out somehow,” we think — because we have to, because otherwise we succumb to despair.

“No one has ever lacked a reason to commit suicide” — but the great majority of us don’t, sensing that just staying alive is “Victory’s dawn, a starry diamond.”

*

WHY PEOPLE FEEL LIKE VICTIMS

~ In a polarized nation, victimhood is a badge of honor. It gives people strength. “The victim has become among the most important identity positions in American politics,” wrote Robert B. Horwitz, a communications professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Horwitz published his study, “Politics as Victimhood, Victimhood as Politics,” in 2018.1 He focused on social currents that drove victimhood to the fore of American political life, arguing it “emerged from the contentious politics of the 1960s, specifically the civil rights movement and its aftermath.”

What lodges victimhood in human psychology?

In 2020, researchers in Israel, led by Rahav Gabray, a doctor of psychology at Tel Aviv University, conducted a series of empirical studies to come up with an answer. They identify a negative personality trait they call TIV or Tendency toward Interpersonal Victimhood. People who score high on a TIV test have an “enduring feeling that the self is a victim in different kinds of interpersonal relationships,” they write.

The study of TIV is built around four pillars. The first pillar is a relentless need for one’s victimhood to be clearly and unequivocally acknowledged by both the offender and the society at large. The second is “moral elitism,” the conviction that the victim has the moral high ground, an “immaculate morality,” while “the other” is inherently immoral. The third pillar is a lack of empathy, especially an inability to see life from another perspective, with the result that the victim feels entitled to act selfishly in response. The fourth pillar is Rumination—a tendency to dwell on the details of an assault on self-esteem.

You only need to spend only a few minutes watching or reading the news, in any country, to hear and see victimhood raging. We caught up with Gabray to get the science behind the headlines.

Is TIV an aberration in the personality?

Sometimes it may be, if one is high on the TIV scale. But we didn’t research clinical patients. That’s not what interested me. I’m interested in how this tendency appears in normal people, not those with a personality disorder. What we found was that like in a bell curve, most people who experience TIV appear in the middle range.

You found a correlation between TIV and what you referred to as “anxious attachment style”, as opposed to “secure and avoidant” styles. What is the anxious style?

Another way to say it is an “ambivalent attachment style.” So when a child is very young, and care is uncertain, perhaps the caregiver, or the male figures in the child’s life, don’t act consistently, sometimes they may act very aggressively without warning, or they don’t notice that the child needs care. That’s when the anxious attachment style or ambivalent attachment style is created.

So victimhood is a learned behavior after a certain age.

Yes, normally children internalize the empathetic and soothing reactions of their parents, they learn not to need others from outside to soothe themselves. But people with high TIV cannot soothe themselves. This is partly why they experience perceived offenses for long-term periods. They tend to ruminate about the offense. They keep mentioning they are hurt, remembering and reflecting on what happened, and also they keep dwelling on the negative feelings associated with the offense: hopelessness, insult, anger, frustration.

Why is it so difficult for people with a high degree of TIV to recognize that they can hurt other people?

They don’t want to divide up the land of victimhood with other people. They see themselves as the ultimate victim. And when other people say, “OK, I know that I hurt you, but you also hurt me,” and want them to take responsibility for what they did, the person with TIV is unable to do it because it’s very hard to see themselves as an aggressor.

In one of your studies, you conclude that TIV is related to an unwillingness to forgive, even to an increased desire for revenge. How did you come to that?

In an experiment, participants were asked to imagine they were lawyers who had received negative feedback from a senior partner in their firm. What we found was that the higher the tendency of participants to perceive interpersonal victimhood, the more they tended to attribute the criticism by the senior partner to negative qualities of the senior partner himself, which led to a greater desire for revenge. Our study finds that not only do people with high TIV have a higher motivation for revenge, but have no wish to avoid their offenders.

How does the fourth pillar of TIV, Rumination, reinforce this tendency?

In the framework of TIV, we define rumination as a deep and lengthy emotional engagement in interpersonal offenses, including all kinds of images and emotions. And what’s interesting is that rumination may be related to the expectation of future offenses. Other studies have shown that rumination perpetuates distress and aggression caused in response to insults and threats to one’s self-esteem.

Can one develop TIV without experiencing severe trauma or actual victimization?

You don’t need to have been victimized, physically abused, for example, in order to exhibit TIV. But the people who score very high on TIV are generally those who have experienced some kind of trauma, like PTSD. Maybe they didn’t fully recover from it. Perhaps they didn’t complete therapy. Something we often see is that they tend to act very aggressively toward family members.

How debilitating is TIV for those with moderate TIV? Does it affect everyday functioning?

Yes. The higher the TIV, the more you feel victimized in all of your interpersonal relations. So if you are in the middle of the scale, you might feel yourself as a victim in one relationship but not another, like with your boss, but not with your wife and friends. But the more you feel like the victim, the more you extend those feelings to all of your interpersonal relationships. And then of course it can affect every aspect in your life. If you feel being victimized in your work, for example—we did a lot of experiments with the narratives of managers and workers—it means that you cannot let stand an offense by your boss, no matter how trivial. I think everyone knows that offenses in interpersonal relations are very common. I’m not talking about traumas, I’m talking about those small daily offenses, and the question is how you deal with it.

TIV aside, can there be a positive aspect of victimhood?

There could be, when victims gather together for some common purpose, like a social protest to raise the status of women. When I’m talking about victimhood, I’m talking about something that has aggression inside it, a lack of empathy and rumination. But when you express feelings of offense in an intimate relationship, it can be positive. Because in that situation you don’t want to hide your feelings. You want to be sincere. You want to be authentic. So if always you’re trying to please, if all the time you say, “No, everything is fine, I wasn’t offended,” that doesn’t help the relationship. I think it’s very important to authentically express your negative feelings inside meaningful relations, because then the other side can be more impacted and you can have a real exchange.

Do people high on a TIV scale tend to seek out lovers or friends who share the trait?

That’s a very smart assumption, but it’s not something I empirically investigated. Theoretically, yes. I think that people who are very low on TIV, if they have this romantic relationship with someone who is high on TIV, then they would not want to continue the relationship. For the relationship to continue, you need two people who are high on this trait or someone who is like this and someone who has very low self-esteem, which is not the same as low TIV, someone who feels they don’t deserve a better relationship.

Do people in most countries show this trait?

There are very big differences between countries. For example, when I traveled in Nepal I found that their tendency for victimhood is very low. They never show any anger and they don’t tend to blame each other. It’s childish for them to show anger.

Victimhood is also a matter of socialization.

Yes, and you see it when leaders behave like victims. People learn that it’s OK to be aggressive and it’s OK to blame others and not take responsibility for hurting others. This is just my hypothesis, but there are certain societies, particularly those with long histories of prolonged conflict, where the central narrative of the society is a victim-oriented narrative, which is the Jewish narrative. It’s called “perpetual victimhood.” Children in kindergarten learn to adopt beliefs that Israelis suffer more than Palestinians, that they always have to protect themselves and struggle for their existence. What’s interesting is the way in which this narrative enables people to internalize a nation’s history and to connect past and present suffering.

Can you extend this dynamic to groups that share this trait?

It’s a very interesting question, but unfortunately I can’t say much about it. What I can say is that the psychological components that form the tendency for interpersonal victimhood—moral elitism and lack of empathy—are also particularly relevant in describing the role of social power holders. Studies suggest that possessing power often decreases perspective-taking and reduces the accuracy in estimating the emotions of others, the interest of others and the thoughts of others. So not only does TIV decrease perspective, but power itself has the same effect.

Additionally, power increases stereotyping and objectification of other individuals. So when you join TIV tendencies and the negative characteristics of the power holder together, it can be a disaster.

What can we do to overcome victimhood?

It begins with the way we educate our children. If people learn about the four components of victimhood, and are conscious of these behaviors, they can better understand their intentions and motivations. They can reduce these tendencies. But I hear people say that if they don’t use these feelings, if they don’t act like victims, they won’t achieve what they want to achieve. And that’s very sad. ~

https://nautil.us/issue/99/universality/why-people-feel-like-victims

Oriana:

For the most part, feeling like a victim is not a productive attitude. Nevertheless, we must be cautious not to dismiss authentic trauma, in war veterans, for instance, or in rape victims or incest survivors. It's uncomfortable to realize that it's not just because some people love to complain. Many people really have unhealed wounds, and could use help.

*

~ Kindness covers all of my political beliefs. No need to spell them out. I believe that if, at the end, according to our abilities, we have done something to make others a little happier, and something to make ourselves a little happier, that is about the best we can do. To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts. We must try to contribute joy to the world. That is true no matter what our problems, our health, our circumstances. We must try. I didn’t always know this and am happy I lived long enough to find out. ~ Roger Ebert (1942-2013)

*

“YOUR BRAIN IS NOT A COMPUTER; IT’S A BIDIRECTIONAL TRANSDUCER”

People are going back and forth

across the doorsill

where the two worlds touch.

--Rumi (1207-1273), “Don’t Go Back to Sleep”

~ When I speak into a microphone, the pattern of sound waves produced by my voice — a distinctive, non-random pattern of air pressure waves — is being converted by the microphone into a similar pattern of electrical activity. The better the microphone, the more accurately it duplicates the original pattern, and the more I sound like me at the other end.

That conversion process — the shifting of a meaningful, non-random pattern of activity — from one medium (say, the air in front of the microphone) to another medium (say, the wire at the back of a microphone) is called transduction.

And transduction is all around us, even in organic processes. Our bodies are completely encased by transducers. Our sense organs — eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin —transduce distinctive properties of electromagnetic radiation, air pressure waves, airborne chemicals, liquid-borne chemicals, textures, pressure, and temperature into distinctive patterns of electrical and chemical activity in the brain. Organic compounds can even be used these days to create new kinds of transducers, such as OECTs: organic electrochemical transistors.

THE ULTIMATE TRANSDUCER

Nearly all religions teach that immaterial realms exist that transcend the reality we know. For Christians and Muslims, those realms are Heaven and Hell. One of the simplest and clearest statements of such a concept comes from ancient Greek mythology: As long as the deceased had the required toll in hand — well, actually in mouth — he or she would be transported by the ferryman Charon across the river Styx to Hades, the land of the dead — quite literally, to the Other Side. (I’ll call it the OS from this point on.) Unfortunately, not everyone was eligible to make the crossing. If no one thought to bury you or to put that coin in your mouth, you were doomed to roam this side of the river as a ghost.

The idea of a realm transcending the one we experience directly has taken on many forms over the centuries. George Griffith, England’s most prominent and prolific science fiction writer of the late 1800s, published a prescient novel about this realm in 1906: The Mummy and Miss Nitocris: A Phantasy of the Fourth Dimension. The book’s protagonist, professor Franklin Marmion, is a distinguished mathematician and physicist who anticipates discoveries and concepts that real quantum physicists would eventually propose decades later. Over the course of the story, Marmion not only reluctantly accepts the fact that a higher dimension must exist, he also acquires the power to shift his body there, which allows him to become invisible. He also learns, among other counterintuitive things, that multiple objects can occupy the same space at the same time.

Regarding human consciousness, James asserted that a universe-wide consciousness existed that beamed human consciousness into our brains “as so many finite rays,” just as the sun beams rays of light onto our planet. Our brains, he said, being limited in their capabilities, generally suppress and filter real consciousness, while sometimes allowing “glows of feeling, glimpses of insight, and streams of knowledge” to shine through. He called this idea “transmission-theory.”

Ideas like James’s have been around for thousands of years. In his 2006 book, Life After Death: The Burden of Proof, alternative medicine guru Deepak Chopra says that ancient Hindu texts teach that the material world we know is nothing but a projection from the universal consciousness that fills all space. From this perspective, death is not an end; it is a merging of a relatively pathetic human consciousness with that of the dazzling universal one. To add gravitas to this idea, Chopra does what many recent authors have done: he suggests that modern formulations of quantum physics are consistent with his belief in a universal consciousness.

The connection between physics and modern theories of mind and consciousness is tenuous at best, but modern physicists do take the idea of parallel universes seriously. They debate the details, but they can hardly ignore the fact that the mathematics of at least three of the grand theories at the core of modern physics — inflation theory, quantum theory, and string theory — predict the existence of alternate universes. Some physicists even believe that signals can leak between the universes and that the existence of parallel universes can be confirmed through measurements or experiments. In a recent essay, physicist A. A. Antonov argues that our inability to detect the vast amount of dark energy that almost certainly exists in our own universe is evidence of the existence of parallel universes, six of which, he speculates, are directly adjacent to our own.

Again, setting the details aside, physicists agree that the three-dimensional space we experience is simply not the whole picture. As theoretical physicist Lee Smolin put it recently, “Space is dead.”

Hard evidence that supports a neural transduction theory is lacking at the moment, but we are surrounded by odd phenomena that are at least consistent with such a theory. And, no, I’m not talking about the claims that best-selling authors have made over the decades about proof that telepathy, out-of-body experiences, and communication with the dead are real. No such proof exists, in my view, but other well documented phenomena are difficult to brush aside.

When I was a graduate student at Harvard, I noticed a stranger roaming the hallway near my office and offered to assist her. Doris, it turns out, had heard voices for years, and she was hoping she could find someone in the psychology building — William James Hall — to help her eliminate them because they "caused trouble." I didn’t have the heart to tell her that Harvard, at the time, had no clinical psychology program and that I was doing behavioral research with pigeons. If her voices had sent her there, they were troublemakers indeed.

When internal perception goes awry, people can be overwhelmed by hallucinations, visions, or distortions of reality so extreme they have to be hospitalized, and Doris had been hospitalized at times.

But is Doris that different from the rest of us? After all, even the healthiest among us hallucinate several times each night — we call it dreaming. And we all have at least two highly disorienting experiences each day called "hypnogogic states" — those eerie, sometimes creative interludes between sleeping and waking.

I have sometimes dreamt intricate full-length movies that seemed as good as any Hollywood film. Alas, most of the time, no matter how hard I try, I can’t seem to hold on to even a shred of a dream during the few seconds when I’m staggering from my bed to the bathroom.

Where does all this content come from, and why do we have so little control over it?

In recent years, researchers have explored what they have clumsily labeled "paradoxical lucidity," or, even worse, "terminal lucidity." These labels refer to what some of us know as "the last hurrah" — the burst of mental clarity that sometimes occurs shortly before people die, even people for whom such clarity should be impossible.

For more than two centuries, medical journals have published credible reports of highly impaired, uncommunicative people who suddenly became lucid for a few minutes before they died. There are documented cases in which people with dementia, advanced Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, and even severe brain damage —– people who have not been able to speak or to recognize their closest relatives for years — suddenly recognized their loved ones and spoke normally.

A 2020 study summarizing the observations of 124 caregivers of dementia patients, concluded that in "more than 80 percent of these cases, complete remission with return of memory, orientation, and responsive verbal ability was reported by observers of the lucid episode" and that ‘"[the] majority of patients died within hours to days after the episode." The periods of lucidity typically lasted 30 to 60 minutes.

Some of the historical reports of lucid episodes are truly extraordinary.

Here is one of many cases reported by the German biologist Michael Nahm and his colleagues in 2012:

In a case published in 1822, a boy at the age of 6 had fallen on a nail that penetrated his forehead. He slowly developed increasing headaches and mental disturbances. At the age of 17, he was in constant pain, extremely melancholic, and starting to lose his memory. He fantasized, blinked continuously, and looked for hours at particular objects…. He remained in the hospital in this state for 18 days. On the morning of the 19th day, he suddenly left his bed and appeared very bright, claiming he was free of all pain and feelings of sickness…. A quarter of an hour after the attending physician left him, he fell unconscious and died within a few minutes. The front part of his brain contained two pus-filled tissue bags the size of a hen’s egg (Pfeufer, 1822)….

And another:

Haig (2007) reported the case of a young man dying of lung cancer that had spread to his brain. Toward the end of his life, a brain scan showed little brain tissue left, the metastasized tumors having not simply pushed aside normal brain tissue but actually destroyed and replaced it. In the days before his death, he lost all ability to speak or move. According to a nurse and his wife, however, an hour before he died, he woke up and said good-bye to his family, speaking with them for about five minutes before losing consciousness again and dying.

If the brain is a self-contained information processor, how can we explain the sudden return of lucidity when the brain is severely damaged? For that matter, think about the variability that occurs in your own lucidity over the course of 24 hours, during which you are, at various times, completely unconscious, partially conscious, or fully conscious. If you add drugs and alcohol to the picture, the variability is even greater, and it can be quite bizarre.

The variability problem is addressed in an intriguing paper published by Jorge Palop and his colleagues in Nature in 2006, who note that patients suffering from a variety of neurodegenerative disorders often fluctuate over the course of a single day between states of extreme confusion and relatively normal mental states. Such radical changes, they note, "cannot be caused by sudden loss or gain of nerve cells." They speculate about changes in neural networks, but that doesn’t solve the problem.

What if the variability is not caused by changes in processing power in the brain but rather by transduction effects? By changes occurring not in our local universe but in the OS [other side]? Or by minor changes occurring at the point of connection? Or by changes occurring in brain structures that are essential to signal transfers?

I’ve also been intrigued by what appear to be credible reports about visual experiences that some congenitally-blind people have had when they were near death. Experiences of this sort were first summarized in a 1997 paper by Kenneth Ring and Sharon Cooper, later expanded into a book called Mindsight (1999). The paper and book describe the experiences of 14 people who were blind from birth and who had near-death experiences (NDEs), some of which included content that appeared to be visual in nature. Soon after Vicki U. was in a near-fatal car accident at age 22, she remembered "seeing" a male physician and a woman from above in the emergency room, and she "saw" them working on a body. Said Vicki:

I knew it was me.... I was quite tall and thin at that point. And I recognized at first that it was a body, but I didn't even know that it was mine initially. Then I perceived that I was up on the ceiling, and I thought, "Well, that's kind of weird. What am I doing up here?" I thought, "Well, this must be me. Am I dead?”

Vicki had never had a visual experience before her NDE, and, according to the researchers, did not even "understand the nature of light." While near death, she also claimed to have been flooded with information about math and science. Vicki said:

I all of a sudden understood intuitively almost [all] things about calculus, and about the way planets were made. And I don't know anything about that.... I felt there was nothing I didn't know.

Several aspects of Vicki’s recollections are intriguing, but the most interesting to me are the visual experiences. How can someone who has never had such an experience "No light, no shadows, no nothing, ever," according to Vicki — suddenly have rich and detailed experiences of this sort? Ring and Cooper found others like Vicki – congenitally blind people who not only had visual experiences when near death but whose NDEs were remarkably similar to some common NDEs of sighted people.

Just recently, an Australian woman made the news worldwide when, post surgery, she woke up with an Irish accent. Her strong Australian accent was completely gone. Called ‘the foreign accent syndrome’, this sudden switch in accents is rare but real. The shift doesn’t make sense given the framework of reasoning we usually apply to the world, but what if it’s a transduction error?

And why can’t we remember pain? We can remember facts and figures and images, and we can even get choked up remembering strong emotions we’ve felt in the past — but we can’t remember pain. Are sensations of pain getting filtered out by transduction pathways? Could that be why our dreams are pain free? That begs a question that is both eerie and obvious: Is the OS [other side] a kind of pain-free Heaven?

And have you ever met a stranger who made you feel, almost immediately, that you had known him or her your entire life? And sometimes this stranger has the same feeling about you. It’s a strong feeling, almost overwhelming. We can try to explain such feelings with speculations about how a voice or physical characteristics might remind us of someone from our past, but there is another possibility — that in some sense you had actually known this person your whole life. If the brain is a bidirectional transducer, that is not a strange idea at all.

In fact, when viewed through the lens of transduction theory, none of these odd phenomena — dreams, hallucinations, lucidity that comes and goes, blind vision, and so on — looks mysterious.

A BETTER BRAIN THEORY

Let’s set aside both the mundane and the exotic reasons we should take transduction theory seriously and get to the heart of the matter: The main reason we should give serious thought to such a theory has nothing to do with ghosts. It has to do with the sorry state of brain science and its reliance on the computer metaphor. One of my research assistants recently calculated that Beethoven’s thirty-two piano sonatas contain a total of 307,756 notes, and that doesn’t take into account the hundreds of sections marked with repeat symbols. Beethoven’s scores also include more than 100,000 symbols that guide the pianist’s hands and feet: time signatures, pedal notations, accent marks, slur and trill marks, key signatures, rests, clefs, dynamic notations, tempo marks, and so on.

Why am I telling you about Beethoven? Because piano virtuoso and conductor Daniel Barenboim memorized all thirty-two of Beethoven’s sonatas by the time he was 17, and he has since memorized hundreds of other major piano works, as well as dozens of entire symphony scores — tens of millions of notes and symbols.

Do you think all this content is somehow stored in Barenboim’s ever-changing, ever-shrinking, ever-decaying brain? Sorry, but if you study his brain for a hundred years, you will never find a single note, a single musical score, a single instruction for how to move his fingers — not even a “representation” of any of those things. The brain is simply not a storage device. It is an extraordinary entity for sure, but not because it stores or processes information. (See my Aeon essay, “The Empty Brain,” for more of my thinking on this issue.)

Over the centuries — completely baffled by where human intelligence comes from — people have used one metaphor after another to ‘explain’ our extraordinary abilities, beginning, of course, with the divine metaphor millennia ago and progressing – and I use that word hesitatingly — to the current information-processing metaphor. I am proposing now that we abandon the metaphors and begin to consider substantive ideas we can test.

To be clear: I am not offering transduction theory as yet another metaphor. I am suggesting that the brain is truly a bidirectional transducer and that, over time, we will find empirical support for this theory.

Recall that Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, published in 1905, and then his General Theory of Relativity, published in 1915, received no direct and convincing empirical support for years — first regarding predictions his equations made about the perihelion precession of Mercury’s orbit, then about the bending of light around the sun (observed by Sir Arthur Eddington in 1919), and then about the gravitational redshift of light. It took a full century before his predictions about gravity waves were confirmed.

If we can cast some aspects of transduction theory into formal, predictive terms (I’m working on that now and am looking for collaborators), we might be able to make specific predictions about transduction — about subtle variations in reaction times, for example, or about how transduction errors might help us explain schizophrenia. We might also be able to predict quantitative aspects of dreams, daydreams, hallucinations, and more.

IGNORE IT AT YOUR PERIL

If transduction theory has merit, let’s think about what happens if we ignore it. If we transported a 17th century scientist to the present day and showed him or her how well we can converse with someone using a cell phone, he or she would almost certainly want to look inside the phone. The remote voice must be in the phone, after all. To put this another way, a Renaissance scientist would naively view the phone as a self-contained processing unit, much as today’s brain scientists naively view the brain.

But that scientist will never find the remote voice inside the phone, because it is not there to be found.

If we explain to the scientist that the phone is a transducer, however, he or she will now examine the phone in a different way, searching for evidence of transduction, which he or she — aided by appropriate instruments and knowledge — will eventually find.

And here is the problem: If you never teach that scientist about transduction, he or she might never unravel the mysteries of that phone.

This brings me to the claustrum, a small structure just below the cerebral cortex that is poorly understood, although recent research is beginning to shed some light. Many areas of the brain connect to the claustrum, but what does it do? If the claustrum turns out to be the place where signals are transduced by the brain, you will probably never discover this remarkable fact if transduction is not on your list of possibilities. (If you’re a history buff, you might also be aware of another small brain structure — the pineal gland — that could conceivably be a transduction site. In his first book, Treatise of man, written in the early 1600s, French philosopher René Descartes identified this gland as the seat of the soul. Remarkably, in the late 1900s, scientists discovered that tissue in the pineal gland responds to electromagnetic radiation.)

If modern brain scientists begin to look for evidence that the brain is a transducer, they might find it directly through a new understanding of neural pathways, structures, electro-chemical activity, or brain waves. Or they might find such evidence indirectly by simulating aspects of brain function that appear to be capable of transducing signals. They might even be able to create devices that send signals to a parallel universe, or, of greater interest, that receive signals from that universe. Comparative studies of animal brains, which could conceivably have limited connections to the OS, might help move the research along.

Efficient and clear transduction might also prove the key to understanding the emergence of human language and consciousness; here is a possible explanation for what might have been the relatively sudden appearance of such abilities in humans (see Julian Jaynes’s 1976 book, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind). Neural transduction might also prove to be the mechanism underlying Carl Jung’s concept of the “collective unconscious.” Even Noam Chomsky’s theory of universal grammar could get a boost from transduction theory; it would hardly be surprising that most or all human languages share certain grammatical rules if languages are all constrained by signals emanating from a common source. And then there’s that ‘flow’ state my friend Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi taught everyone about. When I’m in a hyper-creative mode – now, for example, as I’m writing – I have almost no awareness of this world or of the passage of time. Is the Other Side the source of our creativity?

It might take decades for us to see significant advances in transduction research, but with vast resources already devoted to the brain sciences, we could conceivably move much faster. And if you’re worried that transduction theory is just another one of those inherently untestable theories — like string theory or theories about parallel universes — think again. With neural transduction theory, we have an enormous advantage: The transduction device is available for immediate in-depth study.

IMPLICATIONS AND FINAL NOTES

Will transduction theory finally clear up the old consciousness problem? That I doubt, because I don’t think there is a consciousness problem. Consciousness is just the experience we have when we’re observing ourselves or the world. It seems grand simply because we’re part of the system we’re observing. It’s a classic example of how difficult it can be to study a system of which one is an integral part; think of this problem as a kind of Gödel’s theorem of the behavioral sciences. (For my whole spiel on this issue, see my 2017 essay, “Decapitating Consciousness.”)

If transduction theory proves to be correct, our understanding of the universe and of our place in it will change profoundly. We might not only be able to make sense of dozens of odd aspects of human experience, we might also begin to unravel some of the greatest mysteries in the universe: where our universe came from, what else and who else is out there — even whether there is, in some sense, a God.

If you are as skeptical about flimsy theories as I am, by now you might be thinking: Has Epstein lost his mind (and, if so, where did it go)? Let me assure you that I am as hard-headed as ever. I won’t believe in ghosts until Casper himself materializes in front of an audience and pushes me off the stage. But I am also acutely aware of how little we actually know, both about ourselves and our universe. If one simple idea — brain as transducer — might stimulate new kinds of research and might also bring order to what seem to be scores of unrelated, bizarre, and highly persistent human beliefs, I’m all for it. ~

Robert Epstein is senior research psychologist at the American Institute for Behavioral Research and Technology in California. He holds a doctoral degree from Harvard University and is the former editor-in-chief of Psychology Today magazine. He's authored 15 books and more than 300 articles on various topics in the behavioral sciences.

https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/your-brain-is-not-a-computer-it-is-a-transducer?utm_source=acs&utm_medium=email&utm_email=ivy333%40cox.net&tm_campaign=News0_DSC_210909_00000

Oriana:

I hesitated about posting this article. Universal cosmic consciousness sounds appealing, but why do musical virtuosos have to practice an incredible number of hours before they are ready to give a concert? Shouldn’t they just be able to plug into the cosmic consciousness, and out rolls out a perfect performance of, say, the Moonlight Sonata? Why does it sometimes take a poet years and years to find the perfect ending? Isn’t the poem already part of the universal consciousness, hanging there like a fruit ripe for picking?

The brain certainly receives signals from the outside, but the way it transforms them and arranges them into new patterns points to a much more creative, generative role that Robert Epstein is willing to admit. Sometimes this creative work takes a very long gestation (including struggle on the conscious level) until insight or closure is achieved. And the errors! Even a good writer may overlook the true beginning or the best ending, and keep on going. It’s certainly not just insight, insight, insight, one moment of brilliance after another, as we’d expect if all it took was mainly the reception of the transcendent cosmic consciousness.

A critic may point out to the example to Mozart, who composed with such facility. But even Mozart’s genius underwent deep development, obvious when we compare his kittenish early pieces with the powerful later work.

On the other hand, we still don’t understand much about how the brain works. For instance, there is something to that “last hurrah” burst of clarity not long before dying. It doesn’t always happen, but just the fact that once in a while it does happen should give us a pause. The dying brain has a different biochemistry. Perhaps it takes only a scrap of yet-undamaged neural tissue to suddenly start firing, producing the impression of normal function, if only for a brief while. For now, there is no definitive explanation.

Whatever theory might ultimately gain favor, I think my mother, a neuroscientist, was correct when she said, “The most magnificent thing in the universe is the human brain.”

Mary:

The idea of the brain as a "bidirectional transducer" is fascinating. It seems obvious that the computer model, like the old idea of clockwork, is inadequate, certainly for explaining, or offering any way of understanding, things like sudden lucidity from severely damaged brains, or the near death visionary experiences of people who were blind from birth and hadn't even a way to conceptualize light, much less color and form. The error may be in using a mechanical model at all..the computer is after all a machine, programmed to manipulate data, and even though the circuitry is marvelously intricate and increasingly miniaturized, computers are machines without independent consciousness. They don't ask original questions or have original thoughts, they are dependent on programmers and programs. We all know about "garbage in, garbage out."

The brain, however is a biological organ, living tissue. We know something about the electro-chemical activity, the life of this organ, but are really still at the threshold of understanding. We don't know how consciousness originates, and even less about the what and why of it. The ideas of quantum physics, with it's parallel universes, dark energy, and spooky action at a distance (entanglement) seem to challenge the assumptions of ordinary sensory experience....proposing things like time and space may be illusions dictated by the limits of our own physicality, our bodies and our sensory organs.

These hints and suggestions are like a door into wonderland for us right now..things that tease and tempt the imagination, and baffle understanding, may not be fantasy but scientific reality. This includes things that were part of many mystical traditions: that there are other realities, other worlds, these may be very close, sometimes touching or overlapping, that consciousness may not be finite and limited but infinite, that all things are connected, part of a whole, that sometimes the conscious mind based in living biological tissue, can reach beyond the illusion of separation and connect to a greater whole.

Tantalizing. But we know little about it. Like dark matter and dark energy, it's there but we can't find it yet. I have had strange thoughts of my own — that the universe may be an organic whole, an organism with a development that is more than random, and that is more of a process than an entity, and that consciousness has a function in that process, a role to play greater than the individuals who carry that consciousness. That perhaps consciousness is the ultimate achievement, completion of that process that is the universe.

*

Oriana:

That everything is interconnected somewhat is fine with me. Quantum entanglement fascinates me. That people can sense that a loved one who is far away is suddenly in danger, or maybe has just died — there have been so many accounts of that phenomenon that it would be hard to insist that so many people are deluded or lying. And I’ve experienced it myself.

What bothers me is the all the catastrophic, destructive processes, not just what might be explained away as due to wrongful human activity (maybe Mozart contributed to the illness that killed him at the height of his creative powers; we know Schubert certainly caused his [syphilis]), but natural disasters of all kinds — again, not just those caused or exacerbated by global warming, but volcanic explosions annihilating thriving cities, tsunamis, floods, horrific pathogens wiping out wonderful, beneficial species, and more — all the way up to galaxies colliding. Yes, destruction may be necessary for a new creative cycle, but if there was some transcendent purpose governing all that happens, some beneficent "Other Side" that Epstein assumes exists and beams consciousness to us), we wouldn’t expect the massive suffering. We also wouldn’t see the sheer randomness that appears to be omnipresent, regardless of good and evil.

Again, there are examples of good things that seem to happen against all odds, but frankly, as Mary admits, we don’t know enough. We clutch at the flimsiest straws that can buoy up our belief in a “just universe.” The scientists admit they don’t know, why the average person tends to wishful thinking or worse, conspiracy theories. But we simply don’t know, but it’s possible (arguably even likely) that certain fundamental things will remain unknowable.

Still, let’s by all means rejoice in whatever progress has been achieved by human consciousness at its best — let’s celebrate scientific, technological, and medical breakthroughs, artistic achievements, leaps in social progress (e.g. abolition of slavery, or the miracle of Frances Perkins/ FDR and Social Security and the beginning of social safety net). I call these the triumphs of the collective human genius. It makes me happy to reflect on those.

So perhaps we need to hold both of these in our mind: 1) Life is very random and fragile 2) Life is full of mysterious, wonderful events.

“Death blowing bubbles,” 18th century.

*

The things you put into your head are there forever. You forget what you want to remember and you remember what you want to forget. ~ Cormac McCarthy

Again, this shows we are not in all that much control over our brain function. I think we have some control — nine years ago, I actively chose not to ruminate on past mistakes and misfortunes. I focused on work instead. I did it without drugs or therapy— a friend of mine who happens to be a therapist said I did my own cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) on myself. Still, I had to be completely ready for it, and that readiness came on its own. The recall of positive experiences also happened on its own, as the brain healed at its own pace. I also decided that certain areas were “no-think zones” for me — and I enforced that ban until I had the feeling of “I can cope” no matter where my thoughts strayed. But it took me a year or so of practicing being strong before I got to that more secure place.

*

Jeremy Sherman has some thoughts about dealing with the harshness of reality:

Oriana:

We need to develop a sturdy life philosophy, one that lets us believe that things will work themselves out somehow, and that we are strong enough — and have sufficient emotional support from at least one person — so that we can move forward no matter what hits us (or almost).

*

”In America, we hurry—which is well; but when the day's work is done, we go on thinking of losses and gains, we plan for the morrow, we even carry our business cares to bed with us...we burn up our energies with these excitements, and either die early or drop into a lean and mean old age at a time of life which they call a man's prime in Europe...What a robust people, what a nation of thinkers we might be, if we would only lay ourselves on the shelf occasionally and renew our edges!” ~ Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad

*

THE ONE-BILLION-YEAR GAP IN THE GEOLOGICAL RECORDS — WHERE DID THE MISSING ROCK GO?

~The geologic record is exactly that: a record. The strata of rock tell scientists about past environments, much like pages in an encyclopedia. Except this reference book has more pages missing than it has remaining. So geologists are tasked not only with understanding what is there, but also with figuring out what's not, and where it went.

One omission in particular has puzzled scientists for well over a century. First noticed by John Wesley Powell in 1869 in the layers of the Grand Canyon, the Great Unconformity, as it's known, accounts for more than one billion years of missing rock in certain places.

Scientists have developed several hypotheses to explain how, and when, this staggering amount of material may have been eroded. Now, UC Santa Barbara geologist Francis Macdonald and his colleagues at the University of Colorado, Boulder and at Colorado College believe they may have ruled out one of the more popular of these. Their study appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"There are unconformities all through the rock record," explained Macdonald, a professor in the Department of Earth Science. "Unconformities are just gaps in time within the rock record. This one's called the Great Unconformity because it was thought to be a particularly large gap, maybe a global gap.”