*

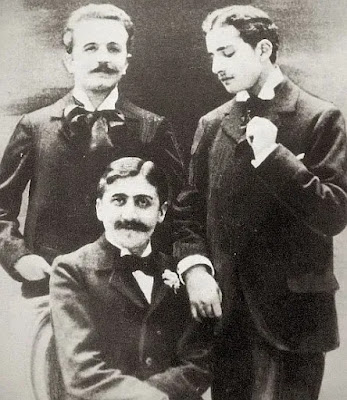

PROUST TO HIS MOTHER

Dearest Maman: A disastrous dawn.

I woke to go to the lavatory, lost

the safety pin I use to close my drawers.

Went wandering through a dozen creaky rooms,

rummaging in your dressers for another pin;

only managed to get slightly chilled.

(Slightly! Hah, hah, what a joke!)

That was the end of sleep, so I picked up

my mother-of-pearl fountain pen

and the blue stationery

you gave me for my birthday

(I had asked for lilac).

People might find it odd

that we write letters to each other

though we live under the same roof.

But you and I understand.

You have a writer’s soul:

that’s why you made me a writer.

I have to dream for us both.

Thank you for the flowers and the thorns.

Why do you torture me? A month ago

you put me in such fury that I seized

a visitor’s new hat and stomped on it,

then mailed you the torn lining

as proof of what you do to me.

You know I can’t get up before seven

in the evening, and expose myself to drafts.

So what if I dine alone at the Ritz

at four a.m., or sit in two pair

of long underwear and a fur coat

in front of a blazing fireplace —

go to bed fully dressed, in gloves and slippers,

or use fifteen towels when I wash —

even that is my art.

Do you have talent? means

Are you abnormal enough?

You say many men could boast

more misfortunes than I,

yet they get out of bed,

kiss their wife and go to work.

But can they suffer as much?

— the first requirement for a writer.

And so I gasp for breath

in the echoes of your widow’s flat.

Another tram shudders by

and your cabinets ring

that high-pitched note that dissects my nerves.

I long for spring — tulips and narcissi —

but I feel so helpless around flowers . . .

As for the time when I broke

a crystal vase because you wanted me

to wear the yellow gloves

while I preferred the gray —

I treasure the letter you wrote:

May this shattered glass, as in the Temple,

be a symbol of indissoluble union.

Even my asthma

is a language between us.

But I must ration myself.

Tomorrow I’ll write in more detail.

A thousand kisses, Marcel.

~ Oriana

*

WHY READ PROUST

~ In Search of Lost Time, like many great literary works, is a quest whose structure resembles that of a symphony. The novel’s major themes—love, art, time, and memory—are carefully and brilliantly orchestrated throughout the book. The opening pages, which Proust called the overture, state in a musical, intimate, and subtle manner the goal of the quest, which is to find the answer to life’s essential questions: Who am I? What am I to make of this life? As Proust’s title indicates, the main character, known as the Narrator or Marcel, is searching for his own identity and the meaning of life. As he tells his story, he speaks to us in a voice that is one of the most engaging and enchanting in all of literature.

I always tell anyone who might be intimidated by the many pages to be read that, although In Search of Lost Time is rich and complex and demands an attentive reader, the novel is never difficult. In spite of its length and complexity, most readers find it readily accessible. Vladimir Nabokov, who considered it the best novel of its era, described its major themes and effervescent, Mozartean style: “The transmutation of sensation into sentiment, the ebb and tide of memory, waves of emotions such as desire, jealousy, and artistic euphoria—this is the material of this enormous and yet singularly light and translucent work.”

In spite of its “enormity” and complexity, Proust’s book has never been out of print and has been translated into well over 40 languages. In Search of Lost Time has not been kept alive by the academy. The work is seldom taught in its entirety in university courses, but maintains its presence among us thanks to readers all over the world who return to it again and again.

Over the years, I have received unsolicited testimony from many such readers who say that Proust changed their lives by giving them a new and richer way of looking at the world. In fact, rendre visible (to make visible) is Proust’s succinct definition of what an original artist does. In Proust’s case, I think he helps us to see the world as it really is, not only its extraordinary beauty and diversity, but his observations make us aware of how we perceive and how we interact with others, showing us how often we are mistaken in our own assumptions and how easy it is to have a biased view of another person.

And I think the psychology and motivation of Proust’s characters are as rewardingly complex as are those of Shakespeare’s characters. Just as the Bard describes Cleopatra, many of Proust’s characters are creatures of “infinite variety.” Speaking of Shakespeare, Shelby Foote, in an interview, placed Proust in the top tier of writers he most admired: “Proust has been the man that hung the moon for me. He’s with Shakespeare in my mind, in the sense of having such a various talent. Whenever you read Proust, for the rest of your life, he’s part of you, the way Shakespeare is part of you. I don’t want to exaggerate, but I truly feel that he is the great writer of the 20th century.”

Great texts are those that involve the reader to an extraordinary degree. We find ourselves placed at the center of the action. In Proust’s case, because of the intimate, engaging first-person narrative, we become the hero’s companion as he seeks to discover the truth about the human condition. In order to discover the truth about our experience and depict it in a novel, Proust brought to bear his extraordinary powers of observation and analysis. Joseph Conrad saw this endless probing as the key to his genius: “Proust’s work . . . is great art based on analysis. I don’t think there is in all creative literature an example of the power of analysis such as this.”

And how does In Search of Lost Time continue to speak to generation after generation in a voice that seems fresh and vigorous? Far from being the culminating opus of decadent literature, as some early critics believed, this novel constitutes one of the most dynamic texts ever written. Its tremendous energy acts as a rejuvenating force. All its narrative elements—plot, characters, style—create, as Iris Murdoch said of its effect, “the most intense pleasure which one does take in great art.”

Here are a few of the outstanding features of this novel: It is arguably the best book ever written about perception. (Proust’s legendary hypersensitivity is obviously linked to his skills as a writer.) He was the first novelist to analyze and depict the full spectrum of human sexuality. There are even passages that might allow him to claim to be the founder of gender studies and a proponent of gay marriage. And his sense of humor allows him to create comic scenes that satirize the foibles and vanity of his characters, especially those of high society. Proust fits perfectly Gilles Deleuze’s definition of a great author: “A great author is one who laughs a lot.”

My favorite quote by one famous writer about another is Virginia Woolf’s description of her reaction to Proust’s prose:

'Proust so titillates my own desire for expression that I can hardly set out the sentence. Oh if I could write like that! I cry. And at the moment such is the astonishing vibration and saturation and intensification that he procures—there’s something sexual in it—that I feel I can write like that, and seize my pen and then I can’t write like that. Scarcely anyone so stimulates the nerves of language in me: it becomes an obsession. But I must return to Swann.'

Proust’s words have enchanted Virginia Woolf and many other writers, dramatists, filmmakers, and choreographers so that often his book becomes a central or significant element in their works. Here is one example: In Search of Lost Time and Albertine, one of its major characters, play a role in Iris Murdoch’s The Good Apprentice. Near the end of her novel, we find Edward, one of the main characters, resuming his reading of Proust:

“Oh—Proust—” Edward had been looking for the passage which had so amazed him . . . about Albertine going out in the rain on her bicycle, but he couldn’t find it. He had turned to the beginning. [Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.] What a lot of pain there was in those first pages. What a lot of pain there was all the way through. So how was it that the whole thing could vibrate with such a pure joy? This was something which Edward was determined to find out.

Although we do not know whether Edward found the answer, Murdoch’s tease at the end of her book is intended as an invitation for us to make our own investigation. This joy stems in part, I believe, from the compassion Proust shows for his characters, even those with whom he finds the most fault. He loves and wants to redeem them all, a sentiment that constitutes a powerful moral force, endowing his characters with life and making them seem real.

Pamela Hansford Johnson, another British writer, sees this as his novel’s great lesson: “There is no novel in the world that changes its readers more profoundly . . . above all it teaches compassion, that relaxing of the mind into gentleness which makes life at once infinitely more complex and infinitely more tolerable.” And: “Proust makes the reader love [the Narrator] so that Proust himself, perhaps more than any writer except Shakespeare, becomes an intimate.”

In the closing pages, Proust urges each of us to comprehend, develop, and deploy our remarkable faculties. He intends his entire enterprise to persuade us that we are incredibly rich instruments, but that most often we let our gifts lie dormant or we squander them. The joy that so many readers feel at the conclusion of the book derives from the long-delayed triumph of the hero and the realization that we too can, by following his example, attempt to lead the true life. When the Narrator completes his quest, after many ups and downs and misunderstandings, the myriad themes—major and minor—beautifully orchestrated throughout, are gloriously resolved in the grand finale. This happy ending makes In Search of Lost Time a comedy of the highest order, one that amuses, delights, and frequently dazzles, as it instructs.

Shelby Foote, as a writer, had a unique relationship with Proust’s novel in that each time he finished one of his own novels or his vast history of the Civil War, he gave himself a special reward: “I’ve always given myself a reward when I finish something and the reward I give myself is always the same thing. I read A la recherche du temps perdu. That’s my big prize. C’est mon grand prix. I think I’ve read it nine times, now. It’s like a two-month vacation because it takes that long to read Proust. I like it better than going to Palm Beach.” ~

https://lithub.com/really-heres-why-you-should-read-proust/

*

People do not die for us immediately, but remain bathed in a sort of aura of life which bears no relation to true immortality but through which they continue to occupy our thoughts in the same way as when they were alive. ~ Marcel Proust

*

NOT EVERYONE LOVES PROUST

Kazuo Ishiguro, in an interview with HuffPo:

To be absolutely honest, apart from the opening volume of Proust, I find him crushingly dull. The trouble with Proust is that sometimes you go through an absolutely wonderful passage, but then you have to go about 200 pages of intense French snobbery, high-society maneuverings and pure self-indulgence. It goes on and on and on and on. But every now and again, I suppose around memory, he can be beautiful.

Evelyn Waugh, in a 1948 letter to Nancy Mitford:

I am reading Proust for the first time—in English of course—and am surprised to find him a mental defective. No one warned me of that. He has absolutely no sense of time. He can’t remember anyone’s age. In the same summer as Gilberte gives him a marble & Francoise takes him to the public lavatory in the Champs-Elysees, Bloch takes him to a brothel. And as for the jokes—the boredom of Bloch and Cottard.

D. H. Lawrence, in his essay “The Future of the Novel”:

Let us just for the moment feel the pulses of Ulysses and of Miss Dorothy Richardson and M. Marcel Proust . . . Is Ulysses in his cradle? Oh, dear! What a grey face! . . . And M. Proust? Alas! You can hear the death-rattle in their throats. They can hear it themselves. They are listening to it with acute interest, trying to discover whether the intervals are minor thirds of major fourths. Which is rather infantile, really.

So there you have the “serious” novel, dying in a very long-drawn-out fourteen-volume death-agony, and absorbedly, childishly interested in the phenomenon “Did I feel a twinge in my little toe, or didn’t I?” asks every character of Mr. Joyce or of Miss Richardson or M. Proust. Is my aura a blend of frankincense and orange pekoe and boot-blacking, or is it myrrh and bacon-fat and Shetland tweed? The audience round the death-bed gapes for the answer. And when, in a sepulchral tone, the answer comes and length, after hundreds of pages: “It is none of these, it is abysmal chloro-coryambasis,” the audience quivers all over, and murmurs: “That’s just how I feel myself.”

Which is the dismal, long-drawn-out comedy of the death-bed of the serious novel. It is self-consciousness picked into such fine bits that the bits are most of them invisible, and you have to go by smell.

Germaine Greer, writing in The Guardian:

If you haven’t read Proust, don’t worry. This lacuna in your cultural development you do not need to fill. On the other hand, if you have read all of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, you should be very worried about yourself. As Proust very well knew, reading his work for as long as it takes is temps perdu, time wasted, time that would be better spent visiting a demented relative, meditating, walking the dog or learning ancient Greek.

Susan Hill, writing in The Spectator:

Since I was 18 I have been told I should read Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu by people who knew all seven volumes by heart and loved every line. You cannot, it seems, be lukewarm about Proust. Knowing that love of it is a badge of honor, and mark of a finely attuned and appreciative literary mind, I have tried eversomany times to get beyond Book One.

Indeed, I have probably read Book One more often than I have read Great Expectations, which is saying something. I have even plucked Volume Three or Seven off the shelf and tried to start there, so please don’t judge me, or tell me I haven’t given it a chance. It’s no good. I find the endless sentences distancing, the people without interest. I cannot care about upper-class French people of the 19th century. Mea culpa, of course. My loss too. But if I have not managed to find the key by the age of 70, I guess I never will. I am denied any enjoyment of Proust’s great novel and there it is. I tried to find one word to sum up how it seems to me. The word is “anaemic.”

Candace Bushnell, in her “By the Book” interview with The New York Times:

I’m too old to be embarrassed by books I haven’t read, people I haven’t slept with and parties I haven’t gone to. However, the one writer I’ve never been able to tolerate is Proust.

James Joyce, in a 1920 letter to Frank Budgen:

I have read some pages of his. I cannot see any special talent but I am a bad critic.

Anatole France, famously (but probably apocryphally):

Life is too short, and Proust is too long.

Frank Triolo:

The difficulty of the novel is that half is tedious and half is sublime. However, it is not possible to sort out these two streams. Listening to the audio version will ease the pain for most. It is simultaneously humorous and touchingly poignant. I would rank rank Ulysses above ROTP because it is a far more radical experiment and filled with a more profound compassion.

Jon Rutherford:

French snobs — or snobs of any nationality — simply do not interest me enough; I've tried many times to get through volume one and failed. I can read Proust in French with little trouble; but it's just not worth it for me, especially at age 82. At age 20 or 30 I probably would have persevered and got through a couple of the volumes. By age 40 or 50 I was starting to wise up a little. Now my interest focuses on highly intelligent, non-snobbish, hopefully compassionate people, and such do not populate volume one, or apparently the rest.

Donald M Wright:

I was told by a French teacher when I was 18 that I absolutely must read Proust because he wrote so beautifully about music (I was a piano major at the time). Mr. Conlon was right. I think it took me about 10 years to read all 7 volumes because I would finish one and then turn to other books before resuming with the next volume. I agree that Du côté de chez Swann was the most interesting volume. Sometimes it's true that beautiful passages and profound and fine-grained observations about human nature were buried in the midst of pages of fatuous French fluff, but I don't agree that the other volumes were dull. It was a bit amusing when a character Proust had killed off in an earlier volume suddenly reemerged in a later one, but then, the invalid Proust did not have a computer at the ready in his cork-paneled bedroom as he wrote!

https://lithub.com/not-everyone-loves-proust/

Oriana:

Like several respondents here, I found the introductory portion and the first volume (about Swann and Odette) quite captivating. Then I reached for Volume Two. A few pages into it, I felt bored. I had zero interest in these characters and their lives, and especially the details of their clothes. This is where good abridgments would be a godsend.

I saw a movie based on Proust’s opus. At long last, this was the abridgment I had hoped for. It was well-crafted, beautifully photographed, but ultimately, what did it have to say?

Still, I wouldn’t go as far as to say that Proust has nothing or very little to give us. He was a keen observer of human psychology. If he were writing now, he might become a best-selling author of self-help books.

*

THE PHILOSOPHY OF GRATITUDE

Marcel Proust was a writer, author, and spiritual thinker in the early 20th century. His most famous work, In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu) is known for being the longest novel ever written — and for its radical views on life.

Proust is really interesting to me because he started out in life just like anyone else of his day. He was brought up in rather violent surroundings, during the consolidation of the French Third Republic, but despite this, his parents being well-educated people provided him with the best opportunities to learn.

His father was a leading pathologist who studied cholera and helped many people learn about hygiene in order to keep the disease at bay. Inspired by this, Proust sought to help humanity with his novels.

The main concept he shared? Gratitude. Although his most famous connotation is the recovery of memory through stimulation of the unconscious — referred to as a Proustian moment, his contribution to a somewhat Eastern outlook on life goes mostly unnoticed. Proust gave us more than just a madeleine moment — he showed us what life could be if only we were grateful.

PROUST WANTS US TO BE GRATEFUL FOR OUR CIRCUMSTANCES

“Desire makes everything blossom; possession makes everything wither and fade.”

Proust first and foremost wanted us to be grateful for our initial circumstances in life. He wanted us not to despair at how our life is but rather, feel appreciative for what we have.

Proust grew up in an upper-middle-class household and found as he got older, that being high up in society was shallow if one was looking for complete fulfillment. As he writes into his character in La Recherche du Temps, socializing and keeping up appearances will not bring everlasting happiness.

What he did find brings happiness is not seeking to always escape our current circumstances in order to be somewhere else that is more perfect in the illusion that it would make us happier. Proust asks us to plant our feet on the ground where we are right now and find happiness anyway.

Proust knew that happiness was not found somewhere else; it is found within ourselves, through gratitude for our initial circumstances.

PROUST CALLS US TO LOVE OURSELVES FIRST

“Love is not vain because it is frustrated, but because it is fulfilled. The people we love turn to ashes when we possess them.”

The second important observation Proust makes is that gratitude for the self (or self love) is vitally important to one's sense of security. In the novel, the protagonist spends a lot of time chasing after a woman. The fluttering of the heart in love is all the protagonist wants to live for.

Proust illustrates that when we are looking for love, we are really looking for someone else to love us completely as we are. We are aiming to substitute loving ourselves, with the distraction of someone else's love. In the end, Proust helps us to see that no one else will 'complete' us.

We must complete ourselves through our own self-love — which in its essence is being grateful for ourselves. We must accept ourselves completely as we are. This way, when we do share our lives with someone else, we are able to enjoy the other's company and companionship. As Proust puts it they won’t “turn to ash” because we won’t try to possess them to mend our own inadequacies.

PROUST INVITES US TO BE GRATEFUL FOR THE PRESENT MOMENT

A real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new lands but seeing with new eyes. ~ Marcel Proust

The final important observation about life Proust makes is that life can be enjoyed to the fullest if we are grateful for each moment as it is. Proust saw those around him in high society becoming depressed and consumed by their melancholy, simply because they were always searching for more. The aristocrats would never be satisfied with what they had, or the circumstances in which they were in, because of their detachment from the present moment.

Proust playing air guitar with a tennis rocket

Proust saw that children, who are innately grateful for everything, were always happy with whatever they had, whether it was deemed significant or not. Children also see the world with a different perspective than adults. Proust coined the term “seeing with new eyes” to describe how an innocent child sees the world.

He deduced that if more people saw the world with new eyes, they would not feel the need to travel to every part of the Earth, seek new romantic partnerships, or strive after more money. In a very Eastern way, Proust encourages us to change our perception.

By being present in the moment, as a child, we too can find joy and happiness. Gratitude for our present moment can revolutionize how we perceive the world, and make us happier because of it.

https://www.claudiamerrill.com/blog/philosophy-of-marcel-proust

Mary:

In Proust's quoted address to his mother he reveals himself as neurasthenic and peculiar, sensitive to an extreme almost comical and grotesque...his extraordinary susceptibility to drafts, for instance, and his measures to avoid them. Sleeping fully dressed and in slippers, sitting in double long underwear wrapped up in a fur coat, next to a roaring fire, using 15 towels to dry himself — habits, or requirements, eminently peculiar and comical.

I must confess I read all seven volumes without much enjoyment, and wrote a paper about it framed entirely in the passive voice...an unconscious stylistic choice that echoed my feeling of distance and alienation from the work. I just could not either identify with or care about all these upper class characters and their mannered, intricate, highly ornamental world.

Proust was not at all in Shakespeare's class for me. The books I read over and over were by Dostoyevsky, Dickens, Bronte...whose characters, despite difference in the era and culture, moved in a world I recognized as real, with lives full of struggles and concerns I felt as vital, authentic, familiar and interesting. Intimacy with Proust's narrator Marcel did not happen for me, and after so many hundreds of pages, yes, endless boredom, the feeling of enclosure in a stuffy room with too many pieces of small furniture, and fussy, breakable, silly ornaments on every surface.

I guess that's my own kind of snobbery.

Oriana:

Dickens would have had fun describing a Proust-like character. He was incredibly eccentric. But his asthma was real.

This was before any effective treatments. One could argue that his prolific output in spite of the exhausting disease also makes him heroic.

I enjoyed the introductory chapter and the volume devoted to Swann and Odette, but never got more than several pages into the second volume. As in your case, I simply couldn’t get interested in Proust’s characters. Those people never did anything interesting. Even the summaries bored me. I admire your endurance in having read all seven volumes. Wow!

*

*

WHY DON’T MORE WOMEN PROPOSE?

Rebekah Kendall, a New York City public school teacher, used her February 2021 break to do something few women ever get to do: she proposed to her boyfriend, Bilig Bayar, an assistant principal at a different New York City school, on a beach at a resort in Jamaica. "I got down on one knee, did the whole thing," says Kendall.

She had scoped the perfect spot while Bayar was at the gym, set up her phone to take pictures under the pretense she wanted vacation snaps, and bought a fancy watch to give him instead of a ring. "I really had the element of surprise on my side," she says. "He had no expectation of it and he was just shocked and so elated and it was really special and really fun." (He said yes.)

She shared her plans with her friends beforehand, and their reaction was muted. "They didn't try to talk me out of it, but they definitely didn't have the reaction that I would have liked," says Kendall. "They were like, 'That's ... that's so you!' Like, 'Good for you!'" She told her mother in advance but not her father: "I didn't really know the protocol on how to ask you for my own hand in marriage to give to someone else," she told him.

The process by which men and women meet, mate, and manufacture more humans is undergoing a radical realignment. Half a century ago two-thirds of Americans ages 25 to 50 were living with a spouse and a smattering of offspring. Today, that fraction is closer to one-third. Whereas marriage used to be an institution widely adopted across all socioeconomic levels, today marriage is much more prevalent among people who are wealthy and educated.

About one in a hundred marriages in the U.S. are between people of the same sex. An unknown but growing fraction of them, including the former Mayor of New York City's, are openly non-monogamous.

But plenty of things about the process of getting married have remained stubbornly unchanged. Men still buy women expensive engagement rings, even when a couple already shares expenses.

American women married to men continue to take their husband's last names, at a rate of 80:20. After a lull during the pandemic, the wedding industry is back in the black or, um, white. And the overwhelming number of proposals are still made by men.

Data on how many women propose is not robust. But Michele Velazquez, who helps plan proposals with her company The Heart Bandits, says she has seen no increase in the number of women proposing in the 13 years she has been in business. She estimates that only three women from heterosexual couples contact her per year.

The latest figures from the U.S. Census Bureau say that there are only 90 unmarried men for every 100 unmarried women. More women than ever are earning money of their own and thus less reliant on men for financial stability. And most women are already living with the men they are going to marry before any proposal is plotted. These market conditions—an undersupply of men, an ability to provide, and the willing presence of a local candidate—would seem to clear the way for women to do the asking. Yet they don’t.

What prevents a woman who wishes to marry her partner from proposing to him? Is it mortification, the suggestion that a woman had to force the issue because she was not desirable enough to be chosen? Is it the unspoken prohibition on any act that whiffs of female aggression or ambition? Does it seem forward and loose, as if these women were throwing themselves at men? "Sometimes women are embarrassed to admit they proposed," says Julie Gottman, co-founder of The Gottman Institute and co-author of the marriage-advice staple, The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. "It makes them seem pushy and controlling, and perhaps not loved enough to receive a proposal.”

She points to the mesmerizing effect of years of saturation in romantic fairy tales. "As much as we’ve tried to establish new, more egalitarian standards for ourselves, those images and their influence have seeped into our bones," says Gottman. "It’s nice to be begged to marry. That’s really being wanted.”

For Aaron Renn, a conservative thinker and writer at the American Reformer, the converse is also true. To ask someone to marry you is to risk being spurned. "I think men have traditionally always just had this understanding that they have to bear the risk of rejection," he says. Women hold the high ground in that encounter, and they may not wish to cede it. "Do you want to be the party that is in the position to decide: 'I accept or reject,'" asks Renn, "or do you want to be the party who is at risk of being accepted or rejected?”

When New Yorkers Amy Shack Egan and John Egan decided to get married in 2017, they opted for a third alternative. They both love sunsets, so they researched the best places to see the sun set and planned a covert trip to the Grand Canyon. They flew to Los Angeles, splurged on a convertible, and drove to their chosen spot where, as the sun went down, they each read something they'd written about why they wanted to spend their lives together.

"We drove up and I remember thinking: 'It's that very rare moment in your life when you know everything is different when you come back to this car,'" says Shack Egan. They each bought their own engagement rings (Shack Egan's was a chunky turquoise) and surprised each other with gifts. She bought him an outdoor couples' massage. He bought her a couples' skydive, because of the metaphorical leap they were taking and "because I've always wanted to go and he's terrified of heights." They had a week alone together before announcing the news to family and friends, who Shack Egan said were pleased, if a bit puzzled by the methodology.

Did she not want the surprise proposal? "I hear proposal stories every day, and the thing I hear the most is that it's never a total surprise," says Shack Egan, who runs the wedding-planning company Modern Rebel. "The conversation around marriage should never be a surprise. If it's a surprise, that's not a great sign." Couples who come to Modern Rebel, which calls its events "love parties," usually want to think outside the box when planning their nuptials, but she has noticed that a proposal from a guy has proved to be a hardy perennial.

Both Shack Egan and Kendall would call themselves feminists but say their motivation was to do something romantic and meaningful and fun rather than strike a blow for equality. Shack Egan told her partner that if he had always dreamed of proposing, she was happy to fulfill that dream. Bayar also surprised Kendall with a proposal of his own a few weeks later, by a waterfall. She says that Bayar had already told her in a hundred different ways that he'd like to spend his life with her, but having had divorce in her family of origin, she was the reluctant one. "I sort of came to the realization that it just is a weird thing that we expect that, like, because he, I don't know, has a penis, that he's meant to be the one to prostrate himself on one knee.”

Rosemary Hopcroft, professor emeritus of sociology at University of North Carolina, Charlotte, thinks the male proposal has been deeply carved into society over millennia. Women want men to propose, with a ring, she says, because historically they needed a mate who could provide for them and their offspring. She points to studies that suggest that across different cultures, women value partners who are providers more than men do. "There's a psychological and emotional reason why women still want their husbands to provide and that doesn't seem to have changed," even as women have become financially independent, she says. "It's obviously not rational. There is no need for it. But we're not just rational actors. We're emotional.”

Shack Egan sees couples every day who are rewriting the rules of weddings and she thinks that's healthy. "We still kind of hold fast to some bridal traditions," she says. "I think if most people stop to think about it, they might realize, 'Yeah, I want parts of this. I don't want parts of this.'"

https://time.com/6314262/why-women-should-propose/?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

*

MORE SINGLE MEN THAN WOMEN

Almost a third of adult single men live with a parent. Single men are much more likely to be unemployed, financially fragile and to lack a college degree than those with a partner. They’re also likely to have lower median earnings; single men earned less in 2019 than in 1990, even adjusting for inflation. Single women, meanwhile, earn the same as they did 30 years ago, but those with partners have increased their earnings by 50%.

These are the some of the findings of a new Pew Research analysis of 2019 data on the growing gap between American adults who live with a partner and those who do not. While the study is less about the effect of marriage and more about the effect that changing economic circumstances have had on marriage, it sheds light on some unexpected outcomes of shifts in the labor market.

Over the same time period that the fortunes of single people have fallen, the study shows, the proportion of American adults who live with a significant other, be it spouse or unmarried partner, also declined substantially. In 1990, about 71% of folks from the age of 25 to 54, which are considered the prime working years, had a partner they were married to or lived with. In 2019, only 62% did.

Partly, this is because people are taking longer to establish that relationship. The median age of marriage is creeping up, and while now more people live together than before, that has not matched the numbers of people who are staying single. But it’s not just an age shift: the number of older single people is also much higher than it was in 1990; from a quarter of 40 to 54-year-olds to almost a third by 2019. And among those 40 to 54-year-olds, one in five men live with a parent.

The trend has not had an equal impact across all sectors of society. The Pew study, which uses information from the 2019 American Community Survey, notes that men are now more likely to be single than women, which was not the case 30 years ago. Black people are much more likely to be single (59%) than any other race, and Black women (62%) are the most likely to be single of any sector. Asian people (29%) are the least likely to be single, followed by whites (33%) and Hispanics (38%).

Most researchers agree that the trend lines showing that fewer people are getting married and that those who do are increasingly better off financially have a lot more to do with the effect of wealth and education on marriage than vice versa. People who are financially stable are just much more likely to find and attract a partner.

“It’s not that marriage is making people be richer than it used to, it’s that marriage is becoming an increasingly elite institution, so that people are are increasingly only getting married if they already have economic advantages,” says Philip Cohen, a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. “Marriage does not make people change their social class, it doesn’t make people change their race, and those things are very big predictors of economic outcomes.”

This reframing of the issue may explain why fewer men than women find partners, even though men are more likely to be looking for one. The economic pressures on men are stronger.

Research has shown that an ability to provide financially is still a more prized asset in men than in women, although the trend is shifting. Some studies go so far as to suggest that the 30-year decrease in the rate of coupling can be attributed largely to global trade and the 30-year decrease in the number of stable and well-paying jobs for American men that it brought with it.

When manufacturing moved overseas, non-college educated men found it more difficult to make a living and thus more difficult to attract a partner and raise a family.

But there is also evidence that coupling up improves the economic fortunes of couples, both men and women. It’s not that they only have to pay one rent or buy one fridge, say some sociologists who study marriage, it’s that having a partner suggests having a future.

“There’s a way in which marriage makes men more responsible, and that makes them better workers,” says University of Virginia sociology professor W. Bradford Wilcox, pointing to a Harvard study that suggests single men are more likely than married men to leave a job before finding another. The Pew report points to a Duke University study that suggests that after marriage men work longer hours and earn more.

There’s also evidence that the decline in marriage is not just all about being wealthy enough to afford it. Since 1990, women have graduated college in far higher numbers than men.

“The B.A. vs. non B.A. gap has grown tremendously on lots of things — in terms of income, in terms of marital status, in terms of cultural markers and tastes,” says Cohen. “It’s become a sharper demarcation over time and I think that’s part of what we see with regard to marriage. If you want to lock yourself in a room with somebody for 50 years, you might want to have the same level of education, and just have more in common with them.”

Wilcox agrees: “You get women who are relatively liberal, having gone to college, and men who are relatively conservative, still living in a working class world, and that can create a kind of political and cultural divide that makes it harder for people to connect romantically as well.”

What seems to be clear is that the path to marriage increasingly runs through college. While the figures on single men’s declining economic fortunes are the most sobering, they are not what surprised the report’s authors the most.

“It’s quite startling how much the partnered women have now outpaced single women,” says Richard Fry, a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center. “About 43% of partnered women have completed at least a bachelor’s degree compared to a third of single women.” He speculates that women may be going to college in greater numbers because it helps them attract a partner in the same way it helps men. “Not only are they rewarded in the labor market with higher earnings, but increasingly, partnership also depends on educational attainment.” ~

https://time.com/6104105/more-single-men-than-women

Joe:

Does the Christian Nationalist movement contribute to single men living at home?

Historically, men were taught to be breadwinners by joining a trade union or obtaining a college education. After Ronald Reagan became president, boys learned that a free man owns a rifle, shuns unions, and rejects higher education.

George Bush, a Yale Graduate, is an example of an educated man who acts like a working bloke. He bought a ranch and arranged for photos of himself cutting wood with a chainsaw or hunting with his dogs. His speeches used few polysyllabic words. When he retired, he sold his ranch and moved into a penthouse to paint landscapes.

Trump is another example of a president who hides his college education and embraces the poor man’s language. The white working man believes Trump understands him, and he mocks Biden, the son of a union man and a supporter of unions and education. Those single males are economically fragile, but they are not stupid.

Many spend their time on their computers, playing games using AI. To an extent, they are self-taught computer programmers with a limited scope, which shrinks their employment opportunities. It is not their intelligence or ability that holds them back. It is their family and church affiliation.

Most of these men come from conservative Christian families who promote ignorance and blame minorities for their children’s lack of opportunity. They believe in the Replacement Theory, derived from Nazi propaganda. After World War I, Germans blamed their loss on the Jewish businesses and banks for failing to support the German State.

Today, in America, the Neo-Nazis say that the Jewish community works to defeat White America by replacing white workers with Latin Americans and African Americans. The focus of Christian Nationalist propaganda is Hollywood, and it originated in the 1920s. Jewish men owned the principal studios.

Movies by the Marx brothers, Benny Goodman, and other Jewish actors treated black men as equals. In the film The Jazz Singer, a young man severs his Jewish family ties and finds success by singing with his face blackened. Although blackface existed for many years, by the 1920s, it gave Jewish performers a path into theaters, previously out of reach.

The Jazz Singer uses the same plot as a Polish movie where a young man becomes successful after he abandons his Jewish family. Later, he rejoins his family, and The Jazz Singer is an example of how Neo-Nazis use antisemitism to reinvigorate racism and allow parents to excuse their support for fascism. However, it limits their children’s prospects. ~

Oriana:

“As of 2022, Pew Research Center found, 30 percent of U.S. adults are neither married, living with a partner nor engaged in a committed relationship. Nearly half of all young adults are single: 34 percent of women, and a whopping 63 percent of men.”

Remember the big concern that young people, especially men, are having lots of sex? It turns out that partnered sex is also at an all-time low: “Recent Pew research indicates that over 60% of young men are currently single. Sexual intimacy is at a 30-year low across genders.”

It’s been interesting to watch the reversal of various trends. “Population bomb” turned into a “de-population bomb”; the perception of youth as the happiest years of one’s life turned into the acknowledgment that “older is happier.” The ideal of a woman shifted from a dependent housewife and dedicated mother to an independent woman who pursues her ambition. As for diets, the fanatic avoidance of fat yielded to fat-rich keto diet. Change is of course inevitable, but this shift from one extreme to the other has been a strange phenomenon to watch. We certainly live in interesting times.

*

BARBIE IS A HIT IN RUSSIA

Officially, the Barbie movie isn't showing in Russia.

But unofficially…

I'm in a Moscow shopping center. A giant pink house has been erected next to the food court. Inside: pink furniture, pink popcorn and life-size cardboard cut-outs of Barbie and Ken who are beaming from ear to ear.

No wonder they're smiling: the Barbie film is pulling in the crowds at the multiplex opposite, despite Western sanctions. After Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a string of Hollywood studios stopped releasing their movies in Russia. But unauthorized copies are getting through and being dubbed into Russian.

Over at the cinema it's a bit cloak and dagger. When I ask one visitor which movie he's come to watch he names an obscure 15-minute Russian film and smiles.

To avoid licensing issues, some cinemas in Russia have been selling tickets to Russian-made shorts and showing the Barbie feature film as the preview.

Russia's culture ministry is not amused. Last month it concluded that the Barbie movie was "not in line with the aims and goals laid out by our president for preserving and strengthening traditional Russian moral and spiritual values.”

Mind you, the cinema goers I speak to are tickled pink that Barbie's hit the big screen here.

"People should have the right to choose what they want to watch," Karina says. "I think it's good that Russian cinemas are able to show these films for us.”

"It's about being open-minded about other people's cultures," says Alyona. "Even if you don't agree with other people's standards, it's still great if you can watch it.”

But Russian MP Maria Butina believes there's nothing great about Barbie: the doll or the film.

"I have issues with Barbie as a female form," she tells me. "Some girls — especially in their teens — try to be like a Barbie girl, and they exhaust their bodies."

Ms Butina adds that the film has not been licensed to appear in Russian cinemas.

"Do not break the law. Is this a question for our movie theaters? Absolutely. I filed several requests to cinemas asking on what basis they are showing the film," she says.

"You talk about the importance of following the law," I say, "but Russia invaded Ukraine. The United Nations says that was a complete violation of international law.”

"Russia is saving Ukraine," she replies, "and saving the Donbas.”

You hear this often from those in power in Russia. They paint Moscow as peacemaker, not warmonger. They argue that it is America, Nato, the West, that are using Ukraine to wage war on Russia. It is an alternative reality designed to rally Russians around the flag.

Amid growing confrontation with Europe and America, the Russian authorities seem determined to turn Russians against the West.

From morning till night state TV here tells viewers that Western leaders are out to destroy Russia. The brand-new modern history textbook for Russian high-school students (obligatory for use) claims that the aim of the West is "to dismember Russia and take control of her natural resources.”

It asserts that "in the 1990s, in place of our traditional cultural values such as good, justice, collectivism, charity and self-sacrifice, under the influence of Western propaganda a sense of individualism was forced on Russia, along with the idea that people bear no responsibility for society.”

The text book encourages Russian 11th graders to "multiply the glory and strength of the Motherland.”

In other words, Your Motherland (not Barbie Land) needs you!

At the Moscow multiplex I'd found many people still open to experiencing Western culture and ideas. But what's the situation away from the Russian capital?

I drive to the town of Shchekino, 140 miles from Moscow. There's a concert on at the local culture centre. Up on stage four Russian soldiers in military fatigues are playing electric guitars and singing their hearts out about patriotism and Russian invincibility.

One of the songs is about Russia's war in Ukraine.

"We will serve the Motherland and crush the enemy!" they croon.

The audience (it's almost a full house) is a mixture of young and old, including school children, military cadets, and senior citizens. For the up-tempo numbers they're waving Russian tricolors that have been handed to them.

As the paratrooper pop stars sing their patriotic repertoire, film is being projected onto the screen behind them. No Barbie or Ken here. There are images of Russian tanks, soldiers marching and shooting and, at one point, of President Vladimir Putin in the Kremlin.

Patriotic messaging is effective. Barbie mania isn't a thing on the streets of Shchekino.

“Right now it's important to make patriotic Russian films to raise morale," Andrei tells me. "And we need to cut out Western habits from our lives. How can we do that? Through film. Cinema can influence the masses.”

"In Western films they talk a lot about sexual orientation. We don't support that," Ekaterina tells me. "Russian cinema is about family values, love and friendship.”

But Diana is reluctant to divide cinema into Russian films and foreign movies.

"Art is for everyone. It doesn't matter where you're from," Diana tells me. "And we shouldn't restrict ourselves to art from one nation. To become a more cultured, sociable and a more interesting person, you need to watch films and read books from other countries, too.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-66934838

*

THE ALCOHOL RATION FOR SOVIET SOLDIERS

100-gram vodka ration for the advancing (not retreating or defending) troops fighting on the frontline was a thing, but a lot of soldiers were not drinking. They were smart enough to understand that even a small loss of concentration could be deadly in battle. And nobody was forcing soldiers to drink. It was just an option. Vodka was offered right before the attack, usually by the petty officer.

Otherwise, the Red Army was technically dry. Soldiers were provided with 100-gram vodka ration only on key Soviet holidays (New Year, Revolution Day, etc).

The real problem was not officially provided vodka. It was the alcohol “found in the field”. German Army alcohol taken as trophies, gifts from the rescued civilians, bottles stolen in Europe… In 1945, the situation became especially dire. Marshal Zhukov, for example, at some point ordered to immediately destroy German tank cars with spirits, “freed” by his troops. It helped, but only a little. There was a lot of civilian alcohol in West and Central Europe.

It wasn’t just about the loss of discipline. Not every seemingly alcoholic substance was safe to drink. On May 9th, 1945, 22 Red Army soldiers died from drinking methanol in Linz, Austria. They were celebrating the German surrender. That wasn’t an isolated incident.

The actual disaster, though, was yet to come. Soon after the war, alcoholism became a national scourge. Soviet people, both men and women, tried to soften the psychological impact of the war by drinking. And it was really easy because alcohol was readily available. Unlike a lot of other things in the Soviet Union.

As for the supplying soldiers with relatively small amounts of vodka, it wasn’t that hard. It was just a minor part of the army supply chain. Constantly supplying troops with reinforcements, food, war machines, ammo, and artillery shells was a lot harder. Vodka doesn’t spoil, it doesn’t take up a lot of space, and it’s easy to divide it into small portions that even a weakened or overburdened person can carry. ~ Boris Ivanov, Quora

Boris Ivanov:

It certainly was like that for my grandfather. He was a very nice, soft-hearted man showered with family love in his childhood. War was the complete opposite of that. It didn’t break him exactly, but there was a fracture in his mind that had never healed. He screamed in his sleep for decades. And he became an alcoholic over the years, little by little. By the end, it was a sorry sight.

Alexander Shakhnovsky:

My grandma was a girl back than. She worked in hospital helping wounded. Then she worked as collecting food from locals in Siberia. In summer she would go up the river Yenisey, during winter use the ice road. While at the same time she was a daughter of enemy of the state and almost never she drank vodka, or other hard spirits.

But my grandfather on mother's side became an alcoholic. His wife died from cancer very fast and he couldn't cope with loss. That's why my mom was raised in Leningrad.

It became a problem rather at the end of the Soviet Union in the mid 80s.

Andrei Tupkalo:

Actually, the standard of living improved tremendously. Soviet Union before the war was not just poor, it was pauper-level poor. But there was a sort of an economic boom after the war. Even the much-maligned housing campaign of Khruschev was unimaginable before. Millions moved from barracks and dugouts into tiny, but fully functional family apartments with such amenities as hot and cold water, heating, sewers (meaning, no crapping into a pit in a plywood shack at -20°C), etc. Which didn’t need to be shared with the other families!

Politically, though, not so much.

Kristoff Etranos:

I think the Soviet officer Corps already had a drinking problem even before Barbarossa.

Boris Ivanov:

Yep, that was always a problem. Even in the Tsarist Army. According to the official statistics of the Tsarist Army hospitals, at one point, there were 36 alcoholic officers for each alcoholic soldier. Of course, it was officially discouraged, but it was hard to make officers quit drinking. Having good times with other officers was an important part of their life.

Aldo Rovinazzi:

Most foreigners have no idea that a large part of the Russian population are teetotalers and that many religious and cultural currents are forcefully anti-alcohol.

Luke Hatherton:

“Spirits freed by his troops.” The Red Army, liberating alcohol across Europe

*

CAN RUSSIA REGAIN THE POWER IT ONCE HAD?

On October 3, the whole of Russia will conduct civil defense training.

All regions will be doing the exercises in one day, for the 1st time in the history of Russia.

Training legend:

martial law in parts of the country;

full mobilization has been completed;

70% of housing is destroyed;

severe radiation contamination;

danger of chemical contamination;

complete destruction of life support facilities.

Meanwhile, Putin’s buddy Mikhail Kovalchuk, who was given the title of President of Kurchatov Institute of Physics, demanded to blow a nuke in Arctics “at least once”, to scare the West.

Kovalchuk is confident that if Russia blows a nuke on its remote Arctic island, Americans will immediately beg Russia to negotiate.

Novaya Zemla as a proposed site for dropping a nuclear bomb.

During the Cold War, the USSR propagandists were talking about throwing nukes in the ocean and threatening Americans with giant tsunamis.

Everyone remembers what happened to the USSR.

Now, Russia — the country that’s never even ready for the winter season, snowfalls are a big surprise for authorities every year — is trying to prep for an all-in nuclear war.

The truth is, Russia simply cannot “get ready” for a nuclear war — it’s impossible in principle.

*

WHAT PUTIN HAS ACCOMPLISHED IN THE RUSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR

• Doubled borders with NATO

• Lost profitable markets for oil and gas

• Made Russia a vassal of China

• Arranged the largest hole in the budget since the late nineties

• Provoked a record drain of brains and capital from the country

• Achieved the highest number of sanctions in history

Received the status of a wanted war criminal by The Hague

~ Crystal Rose, Quora

*

PERCEPTION OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIETAL IMPROVEMENT IN EASTERN EUROPE

Despite no universal agreement on whether the economic situation is better today than it was under communism, the belief that it is better has become more common in every country since 2009, except Russia. In Poland, 47% held this view in 2009, but today that figure has jumped to 74%. However, in Russia fewer people now say the economic situation is better than under communism.

In Poland, the Czech Republic and Lithuania, majorities say the economic situation for most people is better today than it was under communism. In Hungary and Slovakia, more people say it is better, but substantial minorities still say it is worse. And in Bulgaria, Ukraine and Russia, more than half believe the economic situation is worse today than it was under communism. (This question was not asked in Germany.)

Most Russians characterize the end of USSR as great misfortune.

More than six-in-ten Russians agree with the statement “It is a great misfortune that the Soviet Union no longer exists.” This represents an increase of 13 percentage points since 2011. Only three-in-ten disagree with the statement.

Russians who lived most of their lives under the Soviet Union are more likely to say its dissolution was a great misfortune than are those who grew up under the new system. Among Russians ages 60 and older, roughly seven-in-ten (71%) agree it is unfortunate that the USSR no longer exists, compared with half of Russians ages 18 to 34.

*

Germans view unification positively but feel the East has been left behind economically

Germans are in strong agreement that the 1990 unification of East and West was a good thing for Germany. Roughly nine-in-ten Germans, living in both the regions that correspond with the former West Germany and East Germany, agree with this statement.

However, when asked whether East and West Germany have achieved the same standard of living since unification, only three-in-ten Germans say this is the case.

Since 2009 there has not been much overall movement on this question in Germany as a whole. In former East Germany, however, people are about twice as likely now to say the standard of living is equal to that of the West than they were the last time this question was asked. Still, majorities of Germans from both regions say the East has not yet achieved equal economic footing with the West.

Politicians and business people are seen as gaining from changes since the end of communism, more so than ordinary people.

People are especially inclined to believe politicians have benefited. Roughly nine-in-ten or more express this view in every nation where the question was asked, with the exception of Russia (still, 72% of Russians agree). Roughly three-quarters or more in every country also say business people have profited from the changes at least a fair amount, including 89% of those in the Czech Republic, Poland and Ukraine.

Publics are less inclined to believe ordinary people have been the beneficiaries of such changes. In Bulgaria, Ukraine and Russia, about one-in-five say this. On the other hand, nearly seven-in-ten Poles think ordinary people have prospered under the new system, as well as 54% of Czechs.

Within countries, there are divides on how people see average citizens making out in the change from communism to a free market. In every country where the question was asked, those with higher incomes are more likely than those with lower incomes to say the changes have benefited ordinary people. For example, in Hungary, those with an income at or above the national median are 20 percentage points more likely than those with lesser means to hold this view.

Education is also a dividing line on this question. In every country but Russia, those with more education are generally more likely to say regular people have prospered in the post-Soviet era than are those with less education.

Additionally, those who lived through the communist era are much more likely to say the changes that took place have had not too much or no influence on ordinary people compared with those who were born near or after the changes took place. For example, in Slovakia, 70% of those ages 60 and older say ordinary people did not benefit from the change to capitalism and a multiparty system, compared with 39% who say this among 18- to 34-year-olds. Double-digit differences of this nature appear in every country surveyed, highlighting how those who lived through communism have a more negative view of the post-communist era.

*

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGES SINCE THE FALL OF COMMUNISM

~ When asked about changes that have taken place since the end of the communist era, people across the former Eastern Bloc express support for the shift from one-party rule and a state-controlled economy to a multiparty system and a market economy. However, Russians in particular are less supportive of these changes.

The move to a multiparty system garners the strongest approval from Poles (85%), those in former East Germany (85%) and Czechs (82%). But majorities in Slovakia, Hungary and Lithuania also approve. Roughly half or more in Bulgaria and Ukraine also support the change, even though there are more who disapprove in those countries. Only in Russia do fewer than half express support for the change to a multiparty system.

Support for the shift to a market economy is also robust in most of the countries surveyed, with majority support for the economic change found in many countries where majorities also favor the change to the political system. However, only 38% in Russia approve of the economic change, while 51% disapprove.

People in many of the countries surveyed are less supportive of the changes to the political and economic systems now than they were in 1991. However, since 2009, there has been a notable uptick in positive sentiment toward these changes in about half of the countries surveyed. Russia, a notable exception, is the only country where support has decreased since 2009.

For example, in Hungary, 74% in 1991 said they approved of the change to a multiparty system, and 80% liked the movement to a market economy. But when surveyed again in 2009, only 56% approved of the change to the political system since 1989 and 46% were positive on the change to the economic system. Now, however, 72% of Hungarians approve of the multiparty system and 70% like the capitalist system.

Russians, however, are even more pessimistic than they were in in the past about these changes. In 1991, 61% of Russians welcomed the multiparty system, but that figure is 43% today, an 18 percentage point decline. And positive views toward the market economy are also down significantly since 1991.

Young people in general are keener on the movement away from a state-controlled economy in many of the countries surveyed. For example, in Slovakia, 84% of 18- to 34-year-olds are in favor of this change, compared with 49% of those ages 60 and older. Double-digit age gaps also appear in Bulgaria, Ukraine, Russia and Lithuania.

In most of the countries surveyed, those with more education are more likely to favor the movement to a capitalist economy than are those with less education. In Bulgaria, 78% of those with more than a secondary education favor the change to a capitalist economy, while only 49% of those with less education do. These differences are also significant for the change to a multiparty system.

Similar differences appear when it comes to income, not just for the movement to a free-market economy but also for the change to a multiparty system. In all countries, those with incomes at or higher than the country median are more likely to approve of these changes than are those with incomes below the country medians.

The transition from a state-controlled economy to a capitalist one is much more highly regarded now than in 2009, during the recession. Perhaps because of an improved economic outlook many more now see the economic benefits of the new system compared with communism. However, there are sharp divides across countries on how the change affected most people.

Despite no universal agreement on whether the economic situation is better today than it was under communism, the belief that it is better has become more common in every country since 2009, except Russia. In Poland, 47% held this view in 2009, but today that figure has jumped to 74%. However, in Russia fewer people now say the economic situation is better than under communism.

In Poland, the Czech Republic and Lithuania, majorities say the economic situation for most people is better today than it was under communism. In Hungary and Slovakia, more people say it is better, but substantial minorities still say it is worse. And in Bulgaria, Ukraine and Russia, more than half believe the economic situation is worse today than it was under communism. (This question was not asked in Germany.)

Majorities of Poles, Lithuanians and Germans say the changes have had a good influence across every category asked, including education, standard of living, pride in their country, spiritual values, law and order, health care and family values. On the other end, roughly half or fewer Bulgarians, Ukrainians and Russians say the changes have had a good influence on these various issues, with the exception of the positive influence on pride in their country among Russians (54%) and Ukrainians (52%).

Sentiment is more mixed in Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary, with people generally seeing the benefits of the changing standard of living and pride in their country. But worries persist about spiritual values in the Czech Republic and health care in Slovakia and Hungary.

The most prominent increase is in the percentage of people who think the changes in 1989 and 1991 have had a good influence on the standard of living within each country. In many of the countries surveyed, there have been multifold increases in this sentiment from 1991 to today. For example, in Lithuania, only 9% of people in 1991 said that the recent changes had a positive influence on the standard of living for people in the country at the time. But in 2019, that figure has shot up to 70%, more than a sevenfold increase.

In Ukraine, those who only speak Ukrainian generally see a more positive influence of the societal changes on each issue than Russian-only speakers or those who speak both languages at home.

In Germany, there are many divides on whether the changes since 1989 have had a good influence on national conditions among those who currently live in the West versus those in the East, though overall sentiment in Germany toward these changes is quite positive.

Since 2009 there has not been much overall movement on this question in Germany as a whole. In former East Germany, however, people are about twice as likely now to say the standard of living is equal to that of the West than they were the last time this question was asked. Still, majorities of Germans from both regions say the East has not yet achieved equal economic footing with the West.

Education is also a dividing line on this question.

In every country but Russia, those with more education are generally more likely to say regular people have prospered in the post-Soviet era than are those with less education.

Additionally, those who lived through the communist era are much more likely to say the changes that took place have had not too much or no influence on ordinary people compared with those who were born near or after the changes took place. For example, in Slovakia, 70% of those ages 60 and older say ordinary people did not benefit from the change to capitalism and a multiparty system, compared with 39% who say this among 18- to 34-year-olds. Double-digit differences of this nature appear in every country surveyed, highlighting how those who lived through communism have a more negative view of the post-communist era.

Many say education, standard of living and national pride have improved in post-communist era, and worry about effects on law and order, health care and family values.

For example, those in the West are 20 percentage points more likely than those in the East to say the changes have had a good effect on the education system. Western Germans are also more likely to see the changes as a good influence on law and order and spiritual and family values compared with the East. However, there are no real differences of opinion between the West and East on how changes have benefited standard of living, health care and pride in their country. ~

In summary:

Those in West and East Germany differ on whether some changes to society and culture were good

Young people see benefits of changes to health care system since 1989/1991

Perceptions about changing standard of living differ by income level

Large increase in people saying the standard of living has improved after 1989/1991 changes

Many say education, standard of living and national pride have improved in post-communist era, worry about effects on law and order, health care and family values

People who lived under communism are more convinced that ordinary people did not benefit from societal changes

Those with higher incomes more likely to say ordinary people benefited from changes since end of communism

Younger groups are more optimistic about children’s financial future

Most are optimistic about relations with other European nations and their own country’s culture

Since 1991, life satisfaction has improved across Europe

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/14/political-and-economic-changes-since-the-fall-of-communism/

*

DESERVINGNESS: FRIENDSHIPS AND THE CHANGE TO POST-COMMUNISM

In June 1992, soon after the fall of the Wall, Berliner Zeitung, a formerly state-run newspaper in the communist-ruled German Democratic Republic (GDR), invited its readers to submit letters to the editors on the topic of friendship. What was the meaning of friendship today? One reader recounted that: ‘when my friend got married, it did not impact our friendship at all … our relationship broke off, strangely – but tellingly – with the fall of the GDR. Fundamental differences in our characters revealed themselves, ones we were tacitly aware of, but which had not impacted our friendship before.’

*

What might those differences in character be? During the 1990s, throughout eastern Europe, people witnessed profound economic changes. The transformation period was characterized by contradictions: it gave rise to great political and economic accomplishments, but also to innumerable socioeconomic tragedies. Social upward-mobility expectations, for many, did not materialize. In disadvantaged regions, poverty surged, and many lives were lost due to health-related complications.

DEATHS OF DESPAIR

In an analogy to the deindustrializing rust belt in the United States, social scientists have described the profound health consequences in certain regions and societies of eastern Europe as ‘deaths of despair’. In some areas, especially in the post-Soviet societies further east, economic shock became a persistent reality. In their book Taking Stock of Shock (2021), Kristen Ghodsee and Mitchell Orenstein have calculated that, on average, it took approximately 17 years for the 28 post-communist societies to return to their levels of economic output of 1989.

As the state retreated from the economy, public resources like healthcare were marketized and defunded. Welfare systems weakened. Life chances diverged and social inequalities surged. Individuals who once resided in the same neighborhoods, possessed the means to acquire similar goods, and embarked on comparable if modest vacations found themselves occupying vastly disparate social positions merely a few years after the collapse of the Iron Curtain. People developed different ways of coping with these new realities.

This is where ideas about economic deservingness come into play. Disruptive economic change and the inequalities it gives rise to are not merely abstract concepts; they resonate deeply within a person’s heart and mind. Often, it is through the lens of economic deservingness that people make sense of such transformative shifts.

Economic deservingness involves two aspects: first, the distribution of material resources, which raises questions about fairness and redistributive justice. After 1989, who succeeded in moving up the social ladder, what did they gain, and what were the reasons behind their success or failure? Second, deservingness is evaluated at a personal level, entailing judgments about individuals and their moral qualities. What personal qualities are reflected in material gains or losses during the transition to this new society?

This uneasy connection between the economic and the moral – unsettling because it brings together two realms that are often, and for good reasons, thought of as separate – is what deeply impacts social relationships. For better or for worse, it is within their social networks that individuals develop a deep understanding of economic inequalities and express their nuanced beliefs about justice. That’s what we can learn from listening to people’s stories and memories of the post-1989 changes.

*

The 1990s are typically remembered as a period of great economic opportunities. With the fall of communism, there was freedom, there was a new market society. People wanted to be part of the process of societal opening-up. It is often expressed that the early 1990s provided a chance for individuals to seize control of their own destinies, liberated from the constraints of socialist complacency and the uniformity of life prospects. But what about those who were not ready to embrace this new future?

The process of privatizing the formerly socialist economy began in the early 1990s, soon after the political transition. Numerous companies underwent downsizing or disappeared altogether; millions of jobs were lost. In certain regions of East Germany, for example, unemployment affected up to a third of the adult population.

Individuals had to navigate the challenges of economic hardship. Some perceived those who were struggling as burdens, lacking the willingness to embrace the available opportunities. Such views allowed the successful to uphold meritocratic values and assert their own commitment to hard work as an intrinsic conviction.

There are also accounts of breaking social ties from the opposite perspective. With swiftly widening inequalities, it was easy to feel stagnant while others, even in modest ways, experienced upward mobility. Some individuals recount distancing themselves from those whom they perceived as becoming ‘arrogant’, suddenly preoccupied with expensive dinners, travels and self-centered pursuits. These stories often revolve around how a former friend introduced a market logic into the realm of interpersonal trust, thereby violating the sacred boundary that once distinguished the two.

Maria, today in her late 60s, was laid off from a large, formerly state-owned East German company during its dissolution in the early 1990s, and endured the challenges of a harsh labor market for years. She vividly recalls an incident at her birthday party in the early 1990s that led to the break with a once close friend of hers: ‘At one point she came to my birthday, as a surprise, but only to acquire customers for her business! She occupied my guests, my friends, in this way! So we separated … So that was a case when we said, “No, I don’t want you around anymore.”’ To Maria, the former bond of equality – founded on an implicit agreement about what truly matters in life – was shattered.

Accounts like hers typically do not concern friends who became extremely affluent. Instead, they center on much smaller, subtler differences. People use these stories to criticize meritocratic beliefs and the detrimental effects they have on the purity of social connections. It’s the nuance that counts here, and the fact that these differences emerged from a previously more egalitarian relationship.

It is remarkable that these narratives frame economic realities in moral terms. They emphasize the character traits of individuals, highlighting the way people perceive and evaluate these experiences based on notions of personal virtue and values. This is noteworthy when considering that, during the 1990s, individuals’ life prospects were shaped not by their personal commitment or effort, but rather by factors such as their prior qualifications, gender, geographic location, ethnicity, the fate of their firms, or social connections – all of which are structural forces.

Taking initiative and not relying on others to take care of you are seen as indicators of being a ‘good’ person. In a similar way, staying true to oneself and avoiding behaviors that prioritize money over friendships are valued traits indicating ‘good’ character. These moral judgments assess an individual’s character.

The moral significance involved in these situations lies in the essence of the social relationship as a grown connection. The breach of trust is a breach of a mutual understanding of the history of the relationship. The philosopher Avishai Margalit has eloquently articulated this idea. According to Margalit, betrayal is fundamentally characterized by the disregard of the shared values that previously united two individuals. Betrayal is the act of shattering the meaning of a shared past. Only a strong tie, understood as a tie of mutual commitment, attachment and recognition, can ever be betrayed. Such ties are found in families, but more so in friendship relations.

Two friends’ understandings of their past – the past of the self, and the past of the other – is mutually entangled. Because it is constitutive of the relation, the shared past is ‘colored by the betrayal’. And only a tie that never had as its purpose an external goal can be betrayed. That tie must have been treated as an end in itself. It must have had no other goal but the flourishing of each of the two persons, or more precisely, the flourishing of the relationship itself. Betrayal is the blow to the relation of commitment, which comes with a profound shock to the status of recognition of the other as person. As Margalit notes in his book On Betrayal (2017): ‘The shocking discovery in betrayal is the recognition of the betrayer’s lack of concern; the issue is not one’s interests but one’s significance.’

This understanding of the influence of the past, the temporal nature of social relationships, enables us to acknowledge the connection between economic deservingness and betrayal more accurately. We come to realize that the question of who deserves what after 1989 becomes a central concern for individuals. The moral belief that individuals deserve certain economic outcomes, whether through hard work or social support, also extends to their entitlement to specific social relationships. The stories of broken friendships highlight the desire to purify one’s social sphere from relationships that contradict their sense of deservingness. People yearn for recognition of their economic choices and strive for others to perceive them as deserving as well. This moral claim on their environment and the importance placed on it reveal the significance of economic justice in social ties.