*

CYPRESSES

Tuscan cypresses,

What is it?

Folded in like a dark thought

For which the language is lost,

Tuscan cypresses,

Is there a great secret?

Are our words no good?

The undeliverable secret,

Dead with a dead race and a dead speech, and yet

Darkly monumental in you,

Etruscan cypresses.

Is it the secret of the long-nosed Etruscans?

The long-nosed, sensitive-footed, subtly-smiling Etruscans,

Who made so little noise outside the cypress groves?

Among the sinuous, flame-tall cypresses

That swayed their length of darkness all around

Etruscan-dusky, wavering men of old Etruria:

Naked except for fanciful long shoes,

Going with insidious, half-smiling quietness

And some of Africa’s imperturbable sang-froid

About a forgotten business.

What business, then?

Nay, tongues are dead, and words are hollow as seed-pods,

Having shed their sound and finished all their echoing

Etruscan syllables,

That had the telling.

Yet more I see you darkly concentrate,

Tuscan cypresses,

On one old thought:

On one old slim imperishable thought, while you remain

Etruscan cypresses;

Dusky, slim marrow-thought of slender, flickering men of Etruria,

Whom Rome called vicious.

Vicious, dark cypresses:

Vicious, you supple, brooding, softly-swaying pillars of dark flame.

Monumental to a dead, dead race

Embowered in you!

Were they then vicious, the slender, tender-footed

Long-nosed men of Etruria?

Or was their way only evasive and different, dark, like cypress-trees in a wind?

They are dead, with all their vices,

And all that is left

Is the shadowy monomania of some cypresses

And tombs.

The smile, the subtle Etruscan smile still lurking

Within the tombs,

Etruscan cypresses.

He laughs longest who laughs last;

Nay, Leonardo only bungled the pure Etruscan smile.

What would I not give

To bring back the rare and orchid-like

Evil-yclept Etruscan?

For as to the evil

We have only Roman word for it,

Which I, being a little weary of Roman virtue,

Don’t hang much weight on.

For oh, I know, in the dust where we have buried

The silenced races and all their abominations,

We have buried so much of the delicate magic of life.

There in the deeps

That churn the frankincense and ooze the myrrh,

Cypress shadowy,

Such an aroma of lost human life!

The say the fit survive,

But I invoke the spirits of the lost.

Those that have not survived, the darkly lost,

To bring their meaning back into life again,

Which they have taken away

And wrapt inviolable in soft cypress-trees,

Etruscan cypresses.

Evil, what is evil?

There is only one evil, to deny life

As Rome denied Etruria

And mechanical America Montezuma still.

~ D.H. Lawrence

*

The say the fit survive,

But I invoke the spirits of the lost.

Those that have not survived, the darkly lost,

To bring their meaning back into life again,

Which they have taken away

And wrapt inviolable in soft cypress-trees,

Etruscan cypresses.

~ Fortunately, as we shall see, the Etruscans left us much more than the cypresses. They were the first great civilization on the Italian peninsula, and bequeathed to the Romans much of what the Romans later bequeathed to us.

This is a beautiful elegy for a lost culture — though I'm sure that like any culture, it had its negative aspects. Lawrence chooses to see only the good. He romanticizes the Etruscans. And thus we get, though thankfully not in overdose, the typical DH Lawrence romantic thinking: feelings are good, life of the mind is unnatural; joy of life is good, restraint of “instincts” is bad. Of course the Romans saw the Etruscans as decadent hedonists (never mind what happened to stern Roman virtues later); of course the “machine” civilization of Rome (and later America) knows only how to destroy the more sensual cultures centered in the joy of life.

Grand generalizations simplify too much. Fortunately, “Cypressses” is a poem, and not an essay, with just enough beauty and real poetry to save it from Lawrence’s sermonizing.

THE ETRUSCANS: GREAT TEACHERS OF THE ROMANS

~ The Etruscans were an ancient and powerful pre-Roman civilization who lived in Etruria. If Italy is a thigh-high boot, then Etruria is an inverted triangle which begins just above the front of the ankle and swoops upwards and across the thigh to the Veneto. Although there is evidence of Etruscan inhabitation at either end of Italy, the real focus is in north Lazio, Tuscany and western Umbria.

I have lived in Etruria for over 25 years. My house is a few hundred yards from an Etruscan temple and altar. I have found an Etruscan coin in my garden, a little bronze fragment with tiny Etruscan hands and sherds of their black pottery in the nearby field. I have learned as much as I can about the Etruscans. The more I discover, the more I am convinced that the Romans did a pretty good job of whitewashing these clever, literate, fun-loving people from history.

Some historians believe Rome was originally an Etruscan city and that Rome’s first kings were actually Etruscans. Unquestionably, the civilization shaped the way the Romans thought, their numerals, alphabet and their religion. The architectural features many people associate with Rome: roads, dikes, sewage and drainage systems, bridges and water diversion channels were designed by the Etruscans.

The Etruscan civilization was really a collection of independent city states that shared a common culture and language. Although the Etruscan golden period was between the fourth and sixth centuries BC, they were subsumed into the Roman civilization by the 1st century BC.

ETRUSCAN ORIGINS

There are a number of theories about where Etruscans came from and speculation has been going on a long time. The historian Herodotus says they originated from Lydia, Turkey. Famine hit the land and the people drew lots to stay or go. The Etruscans were the “go” group according to the ancient historian.

His contemporary Hellanicus was of the belief that they were Pelasgians from the Aegean.

Meanwhile Greek historian Dionysus believed the Etruscans were “home-grown” and had their origins in the prehistoric Iron Age period known as the Villanovan in the 10th century BC.

Modern theories are helped by DNA analysis and advanced techniques. There are basically three, which rather pleasingly coincide strongly with the ancient theories:

1. They came as a group from the near East, perhaps Lydia in Asia Minor. In 2007, Italian geneticist Alberto Piazza announced the results of analysis he had carried out on paternal DNA from three groups of people in Etruscan areas: Murlo, Volterra and my own adopted Tuscan valley, the Casentino. The groups were chosen because they were already known to be genetically different from other Italians and they had strong family links going back at least three generations. The scientists claimed there was overwhelming genetic evidence that the Etruscans originated in old Anatolia, now southern Turkey. However, a subsequent study of maternal DNA in 2013 found no links to Turkey.

2. They were descendants of the Pelasgians [early inhabitants of Greece], with a bit of Eastern influence.

3. They were descendants of the Raeti people, a group of Alpine tribes from areas corresponding to present-day central Switzerland, the Tyrol in Austria, northeast Italy, and Germany, south of the river Danube.

Everyone wants to lay claim to the Etruscans. I read a long comment thread on a linguistics site recently where someone was making a passionate case for the Etruscans having originated in Serbia. There is a very intriguing connection between Serbian and Etruscan. The Etruscans called themselves “Rasna” or “Rasenna” which may have been a reference to their roots or could just mean “the people”. The name for ancient Serbia is Rasena.

WRITING AND LANGUAGE

The question mark over their origins is just one of the reasons the Etruscans are often described as “mysterious”. This is alluring and romantic but not exactly true. If you are interested then there is a lot to discover, from physical evidence in the form of cities, tombs, artifacts and museum exhibits, to books and research online in Italian and English.

The epithet arose in part because of the lack of written literature. We have no Etruscan poems, stories or historical accounts, although there are tantalizing references to the fact these works existed. Their art depicts books and scrolls. Roman historian Varro refer to the Tuscae historiae (Etruscan histories) and the Emperor Claudius wrote a 20-volume history of the Etruscans called Tyrrenika. These works have been lost.

It could be chance, of course. Or the fact that they mainly wrote on linen cloth and wax tablets, so nothing remains. But a more sinister and more likely explanation is that this was a calculated, systematic elimination of the history of a pagan people, perhaps as a result of the spread of Christianity.

The Etruscans did leave something for us, though. There is one text of about 1200 words taken from a book written in ink on linen and dating back to the first century BC. It was only preserved because the strips of linen were subsequently used to wrap an Egyptian mummy, now in Zagreb museum. It contains a calendar and instructions for sacrifice and is the longest piece of Etruscan text to date.

There are also over 10,000 fragments of writing, mostly taken from tombs. This inevitably leads to an incomplete picture. If you imagine trying to construct a history of our own civilization based solely on what you find written in cemeteries, then you will have a fair idea of the problem.

Their writing, which starts to appear in the 7th century BC after contact with Greek traders, is unlike any other in the world, yet to me is reminiscent of runic script. It takes some letters from the Greek alphabet and often reads from right to left, although sometimes it has been found with alternate lines reading left to right then right to left.

The problem lies not with the alphabet, but with the meaning of the words. Some breakthroughs have been made. The Pyrgi tablets, three golden pages, two in Etruscan, one in Phoenician, were discovered in 1964 in the old city of Pyrgi, now Santa Severa, on Italy’s Tyrrhenian coast. They are a kind of mini Rosetta stone, the first bilingual text to be found. They are a dedication to the Phoenician goddess Astarte, but the rest is not totally clear.

NATURAL RESOURCES

Etruria was a very rich natural environment, which helped Etruscan society flourish. They proved themselves experts in hydraulics, regulating water courses and draining marshland and lagoons. This meant they could cultivate the land and grow food. They created enclosed fields and grew vines, fruit trees, grain and fibers for textiles using advanced agricultural techniques. (It wasn’t the Romans who “invented” square fields.)

They used the abundant forests of the region to build ships and houses and to fuel the burgeoning metalwork industry made possible because of the area’s mineral resources including silver, copper, tin, and lead.

Their successful exploitation of natural resources led to increased international trade with many maritime nations including the Greeks, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Near East. The Etruscans exported wine, olive oil, iron and bucchero pottery and imported raw materials and ceramics, particularly Greek pottery. Inevitably this trade also led to interchange of ideas, technology, culture and art.

Their metalwork is stupendous, particularly their jewelry. Their belief in the afterlife meant that they left glorious, colorful pieces in tombs. They used gemstones, glass beads and gold, often depicting the natural world.

It’s hard to believe these exquisite items — earrings, brooches, necklaces — were made 2500 years ago. The Etruscans took existing techniques known in Egypt and Mesopotamia to a whole new level, using filigree, embossing and granulation. Granulation is where tiny beads of gold are fixed to a base through heat only, no solder. Their craftsmanship was so impressive that there was an Etruscan revival in the nineteenth century, notably led by Italian jeweler Fortunato Pio Castellani.

GROWING POWER, FADING POWER

The Etruscan civilization was in essence a collection of powerful and independent cities, each with its own way of doing things, which was not always the best tactic and which would ultimately head to their defeat by the Roman empire.

The early and middle years were good though. By the fifth century, the Etruscans dominated the Italian coast and its seas. Thanks to lots of forests, they had amazing wooden ships powered by oars and used them to great advantage. This power did not go unchallenged. There were many battles with the Greeks and the trading rival Syracuse. It was after being heavily defeated by Dionysius I of Syracuse, who basically attacked everything the Etruscans owned along the coastline, that they lost their control of the ports and seas and by the third century BC their maritime dominance had gone.

The Etruscans were warriors as evidenced by their grave goods: spears, shields, bronze breastplates and helmets, despite historians describing them as cowards. (Never believe history written by the winning side). They loved horses and were skilled riders, although the ornate chariots found in their tombs may not have been used in battle. They had a lot to defend and a lot of people to defend it from: the Celts from the north, the increasingly powerful Rome from the south, each other (sometimes city fought city) — there were wars, treaties, truces, sieges (like the 10-year siege of Veii by the Romans), alliances, more wars…

The end was inevitable as Rome’s power grew and the Etruscan cities failed to unite against the common enemy. Cities fell like ninepins: Chiusi, Perugia, Tarquinia, Orvieto and Troilum. When Cerveteri fell in 273 BC it was pretty much the last straw and Rome became the dominant force in Italy. The Etruscans still had to fight both alongside and against their Roman counterparts over the next couple of centuries, but their days as the master civilization and superpower were over.

The famous she-wolf that nourished Romulus and Remus was actually an Etruscan bronze. The children were added later.

GODS AND DIVINATION

Religion played a big part in Etruscan society. They believed that the universe was ruled by gods and that humans had only a small, albeit meaningful, part to play in the cosmos. They thought that the gods’ intentions could be seen in almost every aspect of the natural world, from the vagaries of the weather to how wild fruits grew.

Although we don’t have the original Etruscan texts (if only!) Roman historians relate the story of how these beliefs, which they call the Etrusca disciplina, were delivered to the people by a founding prophet called Tages, a strange mix of boy and wise old man. The myth says that a man was plowing his field when suddenly Tages emerged from an especially deep furrow and started talking to him. A crowd gathered, as they do, and Tages told them how to tell the future using signs, and other magical things. It was probably quite hard to go back to plowing after that, I imagine.

Interpreting lightning was one Etruscan divination discipline, while another involved the flight of birds. The third common method of prediction was haruspicy — examining the liver of a sacrificed sheep or chicken for particular features which the “haruspex” (priest specializing in liver reading) would then interpret. This may sound far-fetched, but the practice was practiced by the Babylonians and has also been depicted on Greek vases.

A 2000-year-old bronze model of the liver divided into 40 sections inscribed with the names of 24 gods was found in Piacenza and is now on display in the Etruscan Museum in Rome.

The Romans relied heavily on Etruscan methods when predicting the future. Remember the famous soothsayer’s line from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar: “Beware the Ides of March?” This comes from an incident related by Roman historian Suetonius where Spurinna, an Etruscan haruspex, used those very words to warn Julius Caesar of the date of his assassination.

TWISTING HISTORY

One of the most attractive aspects of Etruscan culture is their equal treatment of women. They dined and reclined with their men and, married or single, were allowed to go out freely in public, dressed up to the nines. They liked to sing, dance and drink, rode horses astride, raised children and had their own names, rank and legal rights. The Romans (and Greeks) were horrified at Etruscan women’s behavior, distorting history to portray them as sex-mad, debauched, out-of-control prostitutes.

This rewriting of history is not unusual. In Maria Beatrice Bittarello’s paper, The Construction of Etruscan ‘Otherness’ in Latin Literature she points out that Virgil, Livy and Silius talk of the Etruscans cowardice, effeminacy, pride, obsession with divination and love of luxury. She quotes a passage from Virgil’s Aeneid, stating Etruscans are only interested in “serving Venus and Bacchus in sacred banquets where they drink, eat, make love and dance.”

In the paper’s introduction Bittarello puts it rather well when she says: “…the stereotypical descriptions of the ancient Etruscans in the works of Roman historians originate in a carefully calculated and consciously realized attempt to marginalize a prestigious civilization, whether Rome had an Etruscan past (or a cultural debt towards Etruria) or not.”

EARLY HISTORIES

There’s little doubt that Etruscan artifacts have been found for many hundreds, if not thousands of years. But it was really only during the Renaissance that people started to recognize the importance of this civilization, thanks to collectors like Medici Pope Leo X and the first Archduke of Tuscany Cosimo I de Medici. Cosimo is rumored to have been so enthusiastic about Etruscan finds that he is said to have personally helped with the restoration of the famous chimera of Arezzo. His collection forms the foundation of the Archaeological Museum in Florence.

Even then it would be a few centuries before real Etruscan excavations began, and the first major archaeological evidence in Tarquinia, Cerveteri, and Vulci was only found in the nineteenth century. That was when the passion for Etruscheria really took off. Museums began to add the objects unearthed in various digs to their collections, as did the aristocracy of Europe. Who knows how many precious relics lurk in the attics and cellars of assorted castles and stately homes across the continent.

In 2000, divers searching for a Second World War plane 60 meters down off the southern coast of France found something completely unexpected — about 60 Etruscan amphorae of the same design, scattered along the ocean bed. Subsequent investigation discovered the intact lower hull of the ship lying under hundreds of amphorae, the best-preserved Etruscan shipwreck ever found. State-of-the-art tests on several of the unbroken amphorae have shown that they contained tartaric acid — a biochemical marker of wine, as well as pine resin, rosemary and thyme. In other words, the Etruscans were exporting wine to France, possibly for medicinal reasons, given the addition of herbs. The amphorae were from Cisra now Cerveteri, in central Italy.

In 2010 the first ever intact Etruscan house was discovered by archaeologists in Vetulonia about 120 miles north of Rome. Dating back 2400 years it still had terracotta tiles, brickwork, ceramics and household furniture; there were even 100 iron nails which had held the wooden beams in place and two bronze door handles. Having lived in central Italy for over 25 years I can tell you that the bricks and tiles could have come from my house! Local architecture has changed very little and the digital reconstruction of this Etruscan home looks exactly like many of the farmhouses you see all around the area. The house had been destroyed by fire in around 79 AD and the chief archaeologist described it as “a kind of little Pompeii.”

A rare discovery was made in Forcello, Mantua, in 2017. The charred remains of bees, honeycomb and honey found in a workshop dating back to 510–495 BC were analyzed and showed that the bees fed on aquatic plants as well as grapevines, both surprising revelations, pointing to a practice of beekeeping on boats along rivers. This was described a few centuries later by Pliny the Elder.

In 2016, there was an incredible find at Poggio Colla, near Vicchio in Tuscany. During the annual excavations of the Mugello Archaeological Project, sponsored by the University of Pennsylvania and the Southern Methodist University, archaeologists found an ancient Etruscan stone stele which had been used in the foundations of a temple wall. The 500-pound slab had been buried there for over 2500 years and subsequent examination showed that it contained over 120 Etruscan characters along its sides, making this the longest Etruscan inscription ever found. It is still being translated but was a dedication to the fertility goddess Uni and may possibly also contain instructions for worship. It is incredibly rare to find a non-funerary inscription and scholars are wildly excited about the new words they are likely to find.

The site also yielded a shard of bucchero pottery depicting the earliest scene of childbirth in European art, which together with the Uni stele, lends credence to the idea of some kind of fertility cult at Poggio Colla.

The Etruscan civilization reached its zenith in the sixth century BC, but by the second century they had all but disappeared or been subsumed into Roman culture, their weakening power evidenced in archaeological terms by increasingly modest tombs, a decline in imported pottery and no more public building.

I don’t think it is putting it too strongly to say that without the Etruscans, the Romans would not have been the culture and superpower the world remembers and reveres. They had great teachers.

https://fcameronlister.medium.com/why-the-romans-dont-want-you-to-know-about-the-etruscans-2a0ddb26233

(The Etruscans were called “Tusci” by the Romans. This is the origin of the name “Tuscany.”)

THE SPECTER OF DEPOPULATION — OR RESTORING NATURE’S BALANCE?

~ For many years it seemed that overpopulation was the looming crisis of our age. Back in 1968, the Stanford biologists Paul and Anne Ehrlich infamously predicted that millions would soon starve to death in their bestselling, doom-saying book The Population Bomb; since then, neo-Malthusian rumblings of imminent disaster have been a continual refrain in certain sections of the environmental movement – fears that were recently given voice on David Attenborough’s documentary Life on our Planet.

At the time the Ehrlichs were publishing their dark prophecies, the world was at its peak of population growth, which at that point was increasing at a rate of 2.1% a year. Since then, the global population has ballooned from 3.5 billion to 7.67 billion.

But growth has slowed – and considerably. As women’s empowerment advances, and access to contraception improves, birthrates around the world are stuttering and stalling, and in many countries now there are fewer than 2.1 children per woman – the minimum level required to maintain a stable population.

Falling fertility rates have been a problem in the world’s wealthiest nations – notably in Japan and Germany – for some time. In South Korea last year, birthrates fell to 0.84 per woman, a record low despite extensive government efforts to promote childbearing. From next year, cash bonuses of 2m won (£1,320) will be paid to every couple expecting a child, on top of existing child benefit payments.

The fertility rate is also falling dramatically in England and Wales – from 1.9 children per woman in 2012 to just 1.65 in 2019. Provisional figures from the Office for National Statistics for 2020 suggest it could now be 1.6, which would be the lowest rate since before the second world war. The problem is even more severe in Scotland, where the rate has fallen from 1.67 in 2012 to 1.37 in 2019.

Increasingly this is also the case in middle-income countries too, including Thailand and Brazil. In Iran, a birthrate of 1.7 children per woman has alarmed the government; it recently announced that state clinics would no longer hand out contraceptives or offer vasectomies.

Thanks to this worldwide pattern of falling fertility levels, the UN now believes that we will see an end to population growth within decades – before the slide begins in earnest.

An influential study published in the Lancet last year predicted that the global population would come to a peak much earlier than expected – reaching 9.73 billion in 2064 – before dropping to 8.79 billion by 2100. Falling birthrates, noted the authors, were likely to have significant “economic, social, environmental, and geopolitical consequences” around the world.

Their model predicted that 23 countries would see their populations more than halve before the end of this century, including Spain, Italy and Ukraine. China, where a controversial one-child per couple policy – brought in to slow spiraling population growth – only ended in 2016, is now also expected to experience massive population declines in the coming years, by an estimated 48% by 2100.

It’s growing ever clearer that we are looking at a future very different from the one we had been expecting – and a crisis of a different kind, as aging populations place shrinking economies under ever greater strain.

But what does population decline look like on the ground? The experience of Japan, a country that has been showing this trend for more than a decade, might offer some insight. Already there are too few people to fill all its houses – one in every eight homes now lies empty. In Japan, they call such vacant buildings akiya – ghost homes.

Most often to be found in rural areas, these houses quickly fall into disrepair, leaving them as eerie presences in the landscape, thus speeding the decline of the neighborhood. Many akiya have been left empty after the death of their occupants; inherited by their city-living relatives, many go unclaimed and untended. With so many structures under unknown ownership, local authorities are also unable to tear them down.

Some Japanese towns have taken extreme measures to attract new residents – offering to subsidize renovation expenses, or even giving houses away to young families. With the country’s population expected to fall from 127 million to 100 million or even lower by 2049, these akiya are set to grow ever more common – and are predicted to account for a third of all Japanese housing stock by 2033.

As the rural population declines, old fields and neglected gardens are reclaimed by wildlife. Sightings of Asian black bears have been growing increasingly common in recent years, as the animals scavenge unharvested nuts and fruits as they ripen on the bough.

Closer to home, in the EU, an area the size of Italy is expected to be abandoned by 2030. Spain is among the European countries expected to lose more than half its population by 2100; already, three- quarters of Spanish municipalities are in decline.

Picturesque Galicia and Castilla y León are among the regions worst affected, as entire settlements have gradually emptied of their residents. More than 3,000 ghost villages now haunt the hills, standing in various states of dereliction. Mark Adkinson, a British expat who runs the estate agency Galician Country Homes, told the Observer that he has identified “more than 1,000” abandoned villages in the region, adding that a staff member of his was continually on the road, leaving letters at abandoned properties in the hope of tracking down their owners and returning them to the market.

“I’ve been here for 43 years,” he said. “Things have changed considerably. The youngsters have left the villages, and the parents are getting old and getting flats closer to the hospital. You don’t want to get stuck up in the hills when you can no longer drive.”

As in Japan, nature is already stepping into the breach. According to José Benayas, a professor of ecology at Madrid’s University of Alcalá, Spain’s forests have tripled in area since 1900, expanding from 8% to cover 25% of the territory as ground goes untilled. Falling populations would continue to trigger land abandonment, he said, “because there will be fewer humans to be fed.”

France, Italy and Romania are among countries showing the largest gains in forest cover in recent years, much of this in the form of natural regrowth of old fields. “Models indicate that [afforestation of this kind] will continue at least until 2030,” Benayas said.

Rural abandonment on a large scale is one factor that has contributed to the recent resurgence of large carnivores in Europe: lynx, wolverines, brown bears and wolves have all seen increases in their populations over the last decade. In Spain, the Iberian wolf has rebounded from 400 individuals to more than 2,000, many of which are to be found haunting the ghost villages of Galicia, as they hunt wild boar and roe deer – whose numbers have also skyrocketed. A brown bear was spotted in Galicia last year for the first time in 150 years.

A vision of the future, perhaps, in a post-peak world: smaller populations crowding ever more tightly into urban centers. And outside, beyond the city limits, the wild animals prowling. ~

Selas, a village near Molina de Aragon, one of the least populated parts of Spain

Oriana:

Much as I welcome the news of the declining human population, a blessing for the planet, I also see the problems that go with it. It could eventually become humanity's greatest challenge.

It seems that financial incentives, no matter how generous, are not enough to induce women to bear more children than they want, which in some cases is none. What seems more effective is help with raising children, e.g. affordable, high-quality childcare.

For now, though, we can rejoice in the fact that population growth is no longer exponential, and a decline is on the horizon. The more optimistic projections predict peak global population at eight billion, rather than the dreaded eleven billion. We badly need more new forests and other places where nature can heal itself.

As for the problems created by low birthrate, some solutions are bound to emerge, given how enterprising humans have proved, on the whole. I'm not saying that it will be easy and painless. Pretty much everything is both good and bad at the same time.

Lilith:

I loved reading about the natural regrowth of old forests and the mega-fauna coming back as the people disappear. Do you remember a wonderful book from 2008 by Alan Weisman: The World Without Us? He imagined the human race disappearing (form a a pandemic, most likely!) and the processes by which all of our creation would break down as the world went on without us.

I revisited my hometown in the rural midwest after having been away over 40 years. The population was half what it had been during my childhood, the schools had closed because there weren't enough children, and the once thriving Main Street was a ghost street of boarded-up storefronts. Even the bank and the grocery store were shuttered. I knew in my bones that the bird songs I heard were from the descendants of my childhood birds.The bird population had obviously survived.

With America's “flyover country” emptying of people, wouldn't it be nice if Central American asylum seekers could populate it? And in Europe, wouldn't it be nice if the North African and Middle Eastern refugees trying to get to Europe could settle in the ghost towns and transform them into thriving communities? This would be natural human migration, but racism is in the way of it.

Oriana:

Several of the dying Italian small towns did try the experiment of welcoming refugees — and it worked!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8EoHMjM2xSI

Mary: A WORLD OF PLENTY FOR ALL

I found the discussion of falling fertility and population rates very interesting, and encouraging. We always think things are just going to keep on going as they are, and yet we are always surprised that they do not. Common thinking was that population would grow and grow exponentially, past the capacity of the planet's resources, even with our most ingenious strategies to keep up.

The green revolution, modern intensive methods of agriculture — all had their limits, and even built-in failures, as pesticides fail when insects and weeds adapt, setting up an endless cycle where it takes more and more chemicals, and more and more deadly poisons to grow our crops. Agribusiness and factory farming diminishes food diversity. Farms become factories that are monocultures, and in the process we lose variety, adaptability, and taste. Farms are heavily subsidized, and farmers caught in the endless round of chemical warfare, where each new weapon only succeeds for a while, until pests and weeds find their way around them.

It would be wonderful, I think, to step off that treadmill, to replace the constant pressure of growth and more growth, with a pause, a step back, a world that seeks not endless growth, but balance. The transitions won't be easy: there will be a population weighted to a greater number of older people, and a fraction of the young population we are used to. There will be empty houses and ghost villages, but a world more full of wild places, of forests repopulated with wildlife. In these changed circumstances we may very well re evaluate our priorities, find new sustainable ways to live, recover things now threatened with extinction, decide that continuous unrelenting growth is as bad an idea for a society as it is for the cells of a body, where that kind of growth is what defines cancer.

And it seems, as noted, that it's not so simple to reward and encourage population growth. Once women see the possibility of controlling their bodies, of choosing when and even if to have children, there's no turning back. Just as uncontrolled population growth could leave us a world where life is full of pain, starvation and hopelessness, a world with falling population will certainly be quite a different place, with room for everyone, and a life with much less toil and struggle. A world where plenty, where having enough, will be possible for all.

Oriana:

Yes, what a surprise that instead of the “population bomb” we get to witness the first stages of depopulation. Reality is indeed more interesting than fiction — it’s unpredictable. Decades ago, who’d imagine seeing young couples with a baby carriage, and inside the carriage is not a baby but a small dog! I'm no longer astonished when I see that.

Where I live, the trend to fewer children (or none) is evident even in Hispanic families. Suddenly it’s just one school-age child rather than 5-8. I don’t mean one child on average, but still, that one even sees a Hispanic couple with just one school-age child is astonishing in the light of the past, and of course parents always pushing for grandchildren.

And we see a growing number of “child-free” couples. Once the word spreads that raising a child means a horrendous amount of work and trouble and sacrifice, the idea that parenthood brings enormous joy tends to disappear. And now that women have become more outspoken, some say taboo things like, “If I could do it over again, I wouldn’t have had kids.” There is even a Facebook page called “I regret having children.”

Society needs to make having children less punitive.

There is no question that a smaller human population would benefit the planet. As you point out, some problems would simply disappear— we wouldn’t be running out of resources, and the standard of living could be higher for everyone. The exciting news that it’s going to happen: in most countries, family size has gone down dramatically.

At the same time, as with most things, almost nothing is all good or all bad. The transition could indeed be rough, with a large population of the elderly. And you wonder, too, how come so many couples prefer a dog — or several dogs — rather than have children. We don’t want the human species to become extinct . . . But that’s hardly a worry of our times. You and I will continue to suffer from the problems of overpopulation: traffic jams, ever-rising food and utilities prices, environmental destruction, overcrowded cities, and no end of other problems. Still, how fascinating to ponder the future, even though we won’t be here to see it.

*

UNCLE VAN, TROTSKY, AND LOGIC

~ In the summer of 1938 the French surrealist writer André Breton visited Mexico City. During his visit he spent much time with Leon Trotsky, then living in exile and in constant fear of assassination by Stalinists. On his return to Paris, Breton gave a glowing description of Trotsky and his small circle of followers, assistants and protectors, singling out for particular praise a man he called “Comrade Van,” who worked as both Trotsky’s secretary and his bodyguard.

“Anyone who has anything to do with him,” Breton said, “is aware of his extraordinary intelligence and sensitivity and the quickness and clarity of his judgment… I hope he will pardon me for speaking about how moving his life is.” He went on to give a brief account of Comrade Van’s life, emphasizing the moment when, at the age of 18, though he had been admitted to the École normale supérieure, he gave up everything and “spontaneously offered his services to Trotsky.” “At present, he is very poor,” Breton told his listeners, “because Trotsky does not have the means to give anything to his secretaries except room and board. He continues to live without having the least little thing in the way of personal possessions.” He ended by describing Comrade Van as “everything Trotsky could want in a man… here is a real man, a friend in every sense of the word.”

You might have expected the object of this panegyric to be flattered, but Comrade Van was anything but. Instead, he wrote to Breton to correct some of the inaccuracies in his speech. He was 20, not 18, when he went to work for Trotsky, he told him. And he did not “spontaneously offer his service,” he had been asked. As for being “very poor,” that was not how he saw it. He was serving a cause, and money had nothing to do it with it. After all, did the disciples expect payment from Jesus?

Comrade Van evidently was a man for whom precision and accuracy were important, a trait that served him well in later life when he switched from political activism to academia. To philosophers, logicians and mathematicians he is known by the name given to him at birth: Jean van Heijenoort, the editor of From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879-1931, a book that has been regarded as essential by serious Anglophone students of logic since its appearance in 1967. It contains English versions of the most important contributions to the subject during a crucial period in its development.

The papers, many of which had previously been available only in foreign languages or obscure journals, include indispensable writings by some of the most formidable minds of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Russell (who is here with “Mathematical logic as based on the theory of types”), the Italian Peano (“The principles of arithmetic, presented by a new method”) and the Dutch Brouwer (“On the significance of the principle of excluded middle in mathematics, especially in function theory”), as well as the two geniuses who made the book’s title. Most readers of the book, I imagine, have no knowledge of van Heijenoort’s Trotskyist past, nor, indeed, unless they have read Anita Feferman’s excellent biography, From Trotsky to Gödel: The Life of Jean van Heijenoort, are they likely to know much about the life of this extraordinary man.

The story begins in 1912, when Jean van Heijenoort was born in Creil, France. His mother, Charlotte Hélène Baligny, who came from, as he put it, “peasant stock,” was a remarkably intelligent and resourceful woman who would remain throughout his life the person whom he loved and respected most. His father, Jean Théodore van Heijenoort, was a Dutchman who had come to France looking for work. Jean never truly knew his father because he died in September 1914, when Jean was still just two.

In the community in which he grew up, it was not expected that children would pursue an education beyond primary school, but Jean was so outstandingly brilliant that he was sent to the district secondary school, Clermont-de-l’Oise. There, to his mother’s great pride, he was top of almost every class he attended and won almost every prize on offer. From there he progressed to the prestigious Lycée Saint-Louis in Paris, where he was a member of a group of advanced mathematics students preparing for the École normale supérieure, but the rounded preparatory education he received was so excellent that by 1932, even without actually taking up his place at the elite institution, he had advanced knowledge of mathematics, philosophy, physics, chemistry and French literature and could read Latin, Greek and German. He also taught himself Russian. At this point, primarily because of his fluency in languages, he was hired to be Trotsky’s secretary.

He had been drawn to communism while still a schoolboy. At Clermont he joined a communist youth group; while in Paris he joined the Ligue Communiste, the French affiliate of Trotsky’s International Left Opposition. He was by this time so committed to the cause that when he was asked by the leader of the movement in France, Raymond Molinier, if he would consider working as Trotsky’s secretary, he had no hesitation in abandoning his plans of further study and travelling to Prinkipo Island in Turkey, where Trotsky and his partner Natalia had been living in exile since 1929.

For the next seven years, van Heijenoort was Trotsky’s right-hand man, making arrangements on his behalf and transcribing and translating his writings, which in these years covered the deteriorating situation in Europe and the nature of the Nazi threat as well as developments in the Soviet Union. Van Heijenoort also acted as Trotsky’s bodyguard, carrying a gun at all times. Trotsky was forced to keep on the move during those years, and van Heijenoort accompanied him to Denmark, France, Norway and, finally, Mexico City. During that time, he got to know Trotsky extremely well, as he describes in With Trotsky in Exile: From Prinkipo to Coyoacán, published in 1978.

Despite the constant anxiety that Trotsky would be targeted by Stalinist assassins, life in Mexico City, for a short time at least, was fairly pleasant for their small entourage. They mixed with intellectuals, political activists and artists, including Diego Rivera, thanks to whom they had a very nice house in which to live. It is now famous as Frida Kahlo’s “blue house,” the home of the museum dedicated to her life and painting. Like many men before and after him, van Heijenoort became bewitched by Kahlo’s charm, outspokenness and beauty. He had an affair with her that, though brief and discreet, was something that he cherished for the rest of his life. “Ah, Frida,” he once said. “She was one of the great women of my life. Deeply sensual, extremely intelligent, strikingly beautiful, she was like no other woman I have ever known.”

In Mexico, van Heijenoort played a large role in putting together Trotsky’s defense against the accusations made about him during the show trials held in Moscow in 1936 and 1937. At Trotsky’s request, an international commission of inquiry was set up, with the eminent philosopher John Dewey as its chairman, to investigate the charges made by Stalin. The task of preparing for the inquiry was huge, and much of it fell to van Heijenoort. He was in charge of searching the massive pile of relevant documents that Trotsky had collected, of issuing the daily press releases and, as ever, of security. The hearings took place in April 1937, and were extensively covered by the world’s media. Almost every photograph of Trotsky at the hearings has van Heijenoort sitting to his right. Dewey described working on the commission as “the most interesting single intellectual experience of my life.” The verdict reached was that Trotsky was “not guilty” of Stalin’s charges.

Before moving to Mexico, during Trotsky’s exile in France, van Heijenoort had married Gaby Brausch, a fellow communist he had met while a student in Paris. Three months later, Gaby gave birth to their son, Jean, who would be known throughout his life as Jeannot. When the time came for Trotsky to leave France, Jeannot was still just a few months old, but van Heijenoort had no qualms about leaving him and Gaby to accompany Trotsky wherever he went. In November 1937, Gaby and Jeannot rejoined van Heijenoort in Mexico. However, Gaby and Natalia—no strangers to conflict—had an argument so intense that Gaby felt she had to leave. “This time,” van Heijenoort said later, “we both knew that it was really the end.” Their marriage was over.

In the summer of 1939, van Heijenoort married again, this time to a young American called Bunny Guyer, who had come to Mexico to meet Trotsky. A few months later, van Heijenoort decided that he had to leave Mexico. “I had lived for so many years in the shadow of Trotsky,” he later explained, “that I needed to be by myself for myself.” They settled in New York, so that van Heijenoort could investigate the American Trotskyist movement at Trotsky’s behest. It was assumed that he would return to Mexico again before too long. In fact, he never saw Trotsky again.

In New York, while Bunny acted as the breadwinner, van Heijenoort had meetings with the American Trotskyists, wrote articles for their journal, the Fourth International, and spent as much time as he could in the New York City Public Library on 42nd Street, voraciously reading works of history, politics, literature, philosophy and mathematics. The van Heijenoorts moved frequently between New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore. They were in Baltimore when, on 21st August 1940, news came that Trotsky had been assassinated. Van Heijenoort, inevitably, blamed himself. If he had been there, he insisted, he would have recognized immediately that the assassin, the Spaniard Ramón Mercader, was not, as he claimed to be, a Belgian. “I would never have let Mercader into the house to talk to Trotsky alone.”

The last sentence of van Heijenoort’s book, With Trotsky in Exile is: “Darkness set in,” and one has a sense that, after Trotsky’s death, van Heijenoort’s world was a gloomier, colder place than it had been when he was still alive. For the following few years he kept up his association with the American Trotskyists and continued to write for them but, bit by bit, he moved away from political activism and towards academia. In the summer of 1945, he enrolled as a graduate student in mathematics at New York University and, from then on, academic study occupied him more than Trotskyism. The final break came in 1948 when he published an article called “A Century’s Balance Sheet,” in which he repudiated all forms of Marxism. “Bolshevik ideology,” he later said, “was, for me, in ruins. I had to build another life.”

And so, “Comrade Van” became a US citizen and started calling himself “John van Heijenoort.” In the second half of his life, the obsessive precision he had previously brought to bear in his work for Trotsky and his political thinking and political writing would be redirected. He now began to publish brilliantly-written articles on logic, mostly of a historical or expository nature and, for seven years, devoted himself to compiling his source book on mathematical logic. He also helped to edit the papers of Kurt Gödel, known for his famous (and famously difficult) Incompleteness Theorems, which establish that there can be no consistent axiomatic theory of logic from which the whole of mathematics can be derived, a man who has been called the most important logician since Aristotle.

Van Heijenoort’s connection with Trotsky was not altogether forgotten, however. He was heavily involved in the acquisition by Harvard of Trotsky’s papers and in 1958, he returned to Mexico to negotiate with Natalia the addition of her papers to that archive. But Trotsky’s grandson, Sieva, noted sadly that the previously charming, active, dynamic and sympathetic Van had become a different person: “silent, sad, distant.”

By this time, not only had van Heijenoort’s second marriage fallen apart but, within a few years, he had married and divorced a third wife. In Mexico City he married his fourth wife, Anne-Marie, the daughter of Natalia’s lawyer. This was to be the most tempestuous marriage of them all. They divorced in 1981 and then remarried three years later. As Anne-Marie’s mental state deteriorated, so did their relationship. They kept breaking up, only to get back together again.

When van Heijenoort tried to make a final break, Anne-Marie threatened to kill herself. “Of course, she wants to kill me too,” van Heijenoort told a friend. In March 1986, he headed from Stanford back once more to Mexico City, to try to reason with her. Two days after he arrived, Anne-Marie’s maid found his dead body in bed. Three shots had been fired into his head. After killing him, Anne-Marie had put the gun into her own mouth and fired once more.

Few people know of the turbulent life that van Heijenoort led, but From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879-1931 remains an essential purchase for all serious students of logic. ~

Trotsky, Kahlo, Jean Van Heijenoort

Oriana:

Reading about Comrade Van's giftedness, I can't help but mourn that most of it was wasted on being Trotsky's secretary and body guard. Trotsky (another immensely gifted man, unfortunately responsible for much evil) is now on his way to becoming a non-entity, of interest only to historians. It's still a fascinating drama, worthy of a novel by Dostoyevsky (complete with an axe murderer). But no such novel has emerged, and ultimately I have a sense of an immense waste of intellect in service to a wrong cause.

*

“With us, no one is irreplaceable.” ~ Joseph Stalin, quoted by Joseph Brodsky, who continues: “The common denominator of all those [atrocities] is the anti-individualistic notion that human life is essentially nothing — i.e., the absence of the idea that human life is sacred, if only because each life is unique.”

Oriana:

This photo and similar ones used to infuriate my mother. But Churchill, who coined the phrase "the iron curtain," realized that this was "a pact with the Devil."

*

“I think that the romantic impulse is in all of us and that sometimes we live it for a short time, but it's not part of a sensible way of living. It's a heroic path and it generally ends dangerously. I treasure it in the sense that I believe it's a path of great courage. It can also be the path of the foolhardy and the compulsive.” ~ Jane Campion

Oriana:

There is romance and then there is marriage. We need not worry that the sensible way to live will ever be lost in favor of non-stop passion. And yes, as the example of various revolutionaries shows, the path of heroic courage can also lead to great evil.

*

THE VATICAN AND THE JEWS

~ At the center of this drama was an official of the Vatican curia who, as we now know from other newly revealed documents, helped persuade Pope Pius XII not to speak out in protest after the Germans rounded up and deported Rome’s Jews in 1943—“the pope’s Jews,” as Jews in Rome had often been referred to. The silence of Pius XII during the Holocaust has long engendered bitter debates about the Roman Catholic Church and Jews. The memoranda, steeped in anti-Semitic language, involve discussions at the highest level about whether the pope should lodge a formal protest against the actions of Nazi authorities in Rome. Meanwhile, conservatives in the Church continue to push for the canonization of Pius XII as a saint.

The newly available Vatican documents, reported here for the first time, offer fresh insights into larger questions of how the Vatican thought about and reacted to the mass murder of Europe’s Jews, and into the Vatican’s mindset immediately after the war about the Holocaust, the Jewish people, and the Roman Catholic Church’s role and prerogatives as an institution.

Most telling is a remarkable pair of memoranda written as the pope considered whether he should take any action—or make any statement—following the Gestapo’s roundup, on October 16, 1943, of a thousand of Rome’s Jews for deportation to Auschwitz. As of that September, much of Italy was under German control, aided by a Mussolini-led puppet government established in the north. The Germans’ encirclement of the old Roman ghetto and their hours-long rousting of the terrified Jews had been traumatic for the Romans and presented the pope with a problem. Although he had a dim view of Adolf Hitler, he had also taken pains to avoid angering him and was eager to maintain cordial relations with the Germans who occupied Rome and whose goodwill helped keep Vatican City unharmed. Meanwhile, more than a thousand Jews—mainly women, children, and old men—were being held for two days in a building complex right next door to the Vatican, awaiting deportation. The pope was well aware that a failure to speak out could be seen as an abdication of his moral responsibility.

In the end, he judged it imprudent to raise his voice. The Jews were herded onto a train to Auschwitz—and to death for all but a few of them. In the aftermath of this traumatic event, and amid a continuing roundup of Jews throughout German-controlled Italy, the pope’s longtime Jesuit emissary to the Italian Fascist regime, Father Pietro Tacchi Venturi, proposed that some kind of Vatican protest be made. What he suggested was presenting a brief to the German authorities—in the context of a private meeting, not issued as a public document—calling on them to put an end to their homicidal campaign against Italy’s Jews. Two months after the deportation of the Jews of Rome, he went so far as to write a draft of what the official statement should say. The text he wrote, newly discovered in the archives and reprinted verbatim in translation at the end of this article, was titled “Verbal Note on the Jewish Situation in Italy.”

The thrust of the plea was far from pro-Jewish. The proposed Vatican statement argued that Mussolini’s racial laws, instituted five years earlier, had successfully kept the Jews in their proper place, and as a result there was no need for any violent measures to be taken against them. Italy’s Jews, Tacchi Venturi argued, did not present the grounds for serious government concern that they clearly did elsewhere. Nor had they engendered the same hostility from the majority “Aryan” portion of the population that Jews engendered in other countries. This was partly because there were so few Italian Jews and partly because so many of them had married Christians. New laws confining Italy’s Jews in concentration camps, the Jesuit insisted, offended the “good sense of the Italian people,” who believed that “the racial Law sanctioned by the Fascist Government against the Jews five years ago is sufficient to contain the tiny Jewish minority within its proper limits.”

Tacchi Venturi wrote, “For these reasons one nourishes the firm faith that the German Government will want to desist from the deportation of the Jews, whether that done en masse, as happened this past October, or those done by single individuals.”

On receiving the proposed protest, the cautious Pius XII turned to Dell’Acqua for advice. Dell’Acqua responded quickly, sending the pope a lengthy critique two days later, advising against using Tacchi Venturi’s verbal statement, not least because, in Dell’Acqua’s view, it was overly sympathetic to the Jews. “The persecution of the Jews that the Holy See justly deplores is one thing,” Dell’Acqua advised the pope, “especially when it is carried out with certain methods, and quite another thing is to be wary of the Jews’ influence: this can be quite opportune.” Indeed, the Vatican-overseen Jesuit journal, La Civiltà Cattolica, had been repeatedly warning of the need for government laws to restrict the rights of the Jews in order to protect Christian society from their alleged depredations.

Nor, thought the monsignor, was it wise for the Vatican to be saying, as Tacchi Venturi had proposed, that there existed no “Aryan environment” in Italy that was “decisively hostile toward the Jewish milieu.” After all, Dell’Acqua wrote, “there was no lack in the history of Rome of measures adopted by the Pontiffs to limit the influence of the Jews.” He also appealed to the pope’s eagerness not to antagonize the Germans. “In the Note the mistreatment to which the Jews are allegedly being subject by the German Authorities is highlighted. This may even be true, but is it the case to say it so openly in a Note?” It was best, he concluded, that the whole idea of a formal Vatican presentation be abandoned. Better, he advised, to speak in more general terms to the German ambassador to the Holy See, “recommending to him that the already grave situation of the Jews not be aggravated further.”

Dell’Acqua ended his memo to the pope with advice for the Jews who kept making so much noise about the dangers they faced and the horrors they had already experienced: “One should also let the Jewish Signori know that they should speak a little less and act with great prudence.”

(.. . . ) the horrors of the Holocaust were slow to move the Roman Catholic Church to consider its own history of anti-Semitism or the role it played in making the Nazis’ mass murder of European Jews possible. Pope Pius XII was undoubtedly horrified by the slaughter, but as pope or, earlier, as the Vatican’s secretary of state, he had never complained about the sharp measures taken against the Jews as one Catholic nation after another introduced repressive laws (Italy in 1938, for instance, and France in 1940).

The only complaint Pius XII made about Italy’s anti-Semitic laws was the unfairness of applying them to Jews who had converted to Catholicism. That there might have been a link between the centuries of Church demonization of the Jews and the ability of people who thought of themselves as Catholics to murder Jews seems never to have crossed his mind. The fact that Mussolini’s regime relied heavily on Church materials—its newspapers and magazines filled with references to the measures popes had taken over the centuries to protect “healthy” Christian society from the threat posed by the Jews—to justify its anti-Semitic laws led to little rethinking of Church doctrine or practice under his papacy.

It would only be after Pius XII’s death that Church attitudes toward the Jews would change in a meaningful way, thanks to his successor John XXIII, who convened a Vatican Council devoted in part to rooting out the vestiges of medieval Church doctrine on the Jews. The culmination of those efforts came only after Pope John XXIII’s death; in 1965, the Second Vatican Council issued the remarkable declaration Nostra Aetate [in our time]. Reversing long-held Church doctrine, it called on the faithful to treat Jews and their religion as worthy of respect. ~

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/the-popes-jews/615736/

Oriana:

I’ve omitted large portion of the article which deal with the old doctrine that once a child has been baptized, even against the parents’ will, the child remains a Catholic and can’t be returned to the parents or close relatives. This is of course criminal in itself, but the silence in the face of the Nazi mass murder remains the main issue. Fortunately Vatican II was a turning point in the the official attitude of the church toward the Jews, who were finally found to be “worthy of respect.”

This was revolutionary. When I was growing up, Catholicism deemed itself the only true religion; all others, including not just Jews but non-Catholic Christians, were doomed to hell forever. This shook me up: was Gandhi in hell? And my few Jewish classmates, who sang with us and played with us — were they headed for the eternal fire?

Again, the doctrine changed dramatically soon after I left the church. Still, the news made headlines, and millions of Catholics who had been uneasy with the doctrine could rejoice in how fast the church was moving away from the Middle Ages.

*

KATE WARNE, DETECTIVE

~ In 1856, twenty-three-year-old widow Kate Warne walked into the office of the Pinkerton Detective Agency in Chicago, announcing that she had seen the company’s ad and wanted to apply for the job. “Sorry,” Alan Pinkerton told her, “but we don’t have any clerical staff openings. We’re looking to hire a new detective.” Pinkerton would later describe Warne as having a “commanding” presence that morning. “I’m here to apply for the detective position,” she replied.

Taken aback, Pinkerton explained to Kate that women aren’t suited to be detectives, and then Kate forcefully and eloquently made her case. Women have access to places male detectives can’t go, she noted, and women can befriend the wives and girlfriends of suspects and gain information from them. Finally, she observed, men tend to become braggards around women who encourage boasting, and women have keen eyes for detail. Pinkerton was convinced. He hired her.

Shortly after Warne was hired, she proved her value as a detective by befriending the wife of a suspect in a major embezzlement case. Warne not only gained the information necessary to arrest and convict the thief, but she discovered where the embezzled funds were hidden and was able to recover nearly all of them. On another case she extracted a confession from a suspect while posing as a fortune teller. Pinkerton was so impressed that he created a Women’s Detective Bureau within his agency and made Kate Warne the leader of it.

In her most famous case, Kate Warne may have changed the history of the world. In February 1861 the president of the Wilmington and Baltimore railroad hired Pinkerton to investigate rumors of threats against the railroad. Looking into it, Pinkerton soon found evidence of something much more dangerous—a plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln before his inauguration. Pinkerton assigned Kate Warne to the case. Taking the persona of “Mrs. Cherry,” a Southern woman visiting Baltimore, she managed to infiltrate the secessionist movement there and learn the specific details of the scheme—a plan to kill the president-elect as he passed through Baltimore on the way to Washington.

Pinkerton relayed the threat to Lincoln and urged him to travel to Washington from a different direction. But Lincoln was unwilling to cancel the speaking engagements he had agreed to along the way, so Pinkerton resorted to a Plan B. For the trip through Baltimore Lincoln was secretly transferred to a different train and disguised as an invalid. Posing as his caregiver was Kate Warne. When she afterwards described her sleepless night with the President, Pinkerton was inspired to adopt the motto that became famously associated with his agency: “We never sleep.” The details Kate Warne had uncovered had enabled the “Baltimore Plot” to be thwarted.

During the Civil War, Warne and the female detectives under her supervision conducted numerous risky espionage missions, with Warne’s charm and her skill at impersonating a Confederate sympathizer giving her access to valuable intelligence. After the war she continued to handle dangerous undercover assignments on high-profile cases, while at the same time overseeing the agency’s growing staff of female detectives.

Kate Warne, America’s first female detective, died of pneumonia at age 34, on January 28, 1868, one hundred fifty-three years ago. “She never let me down,” Pinkerton said of one of his most trusted and valuable agents. She was buried in the Pinkerton family plot in Chicago. ~

https://pinkerton.com/our-insights/blog/unsung-heroes-first-female-detective-kate-warne

Charles:

The story about kate Warne was tear wrenching. There should be a movie about her.

Oriana:

Kate Warne’s story is indeed a movie waiting to be made. It’s so easy to imagine her entering Pinkerton’s office and shocking him by wanting to be a detective. And her rescue of Lincoln . . . wow. And finally, Pinkerton has her buried in the Pinkerton family plot. One could hardly ask for better material.

*

WHY EVANGELICALS ARE ESPECIALLY PRONE TO CONSPIRACY THEORIES

Here are some of the reasons I believe too many evangelicals/fundamentalists (E/Fs) are prone to believing conspiracy theories:

Their view of the Bible. If the Bible is held to be true in the same way a science or mathematics textbook is “true,” then all sorts of folly is sure to follow. Such a view opens the door to doubting acknowledged experts, the academy, proven authorities, and accepted bodies of knowledge, if they disagree with or don’t support this groups’ interpretation of the Bible, whatever the subject matter. This allows E/Fs to dismiss or discount information they think contradicts the Bible (or their interpretation thereof). This in turn creates an openness to a belief in conspiracy theories, often the alternative explanation for whatever the issue might be.

Their eschatology or understanding of the End Times. Any E/F growing up in the 70s, 80s, and even 90s can tell stories about pastors and leaders taking the book of Revelation and applying it to current world events. How they applied it though is key. The assumption was always that whatever was being reported, no matter how mundane or banal, they knew the “true” meaning of the event, because they understood the book of Revelation.

Thus, for example, any new technology pertinent to commerce was really about getting people to accept the Mark of the Beast (666), and any new helicopter the Israelis developed was really what the book of Revelation (9:7) described as locusts. This type eschatology, it turns out, is a gateway to believing conspiracy theories and frankly, all sorts of nonsense.

Their past pastors, theologians, and leaders. For decades, E/Fs have followed and listen to a parade of people spouting conspiracy theories. Indeed, many were quite influential and revered. E/Fs bought their books, went to their conferences, and supported their ministries. From Hal Lindsey, to Tim Lahaye, to Pat Robertson and many others, the E/F landscape is strewn with famous figures spewing conspiracy theories. These theories ranged from the identity of the anti-Christ, to the fear of Freemasons, the Rothschilds, the Illuminati, and a one-world-government. Long before the internet, the so-called “fake news,” and QAnon, E/Fs were already believing in, and echoing, conspiracy theories. They are a ready-made audience for our present moment and current conspiracy theories.

Additionally, a significant factor is the reliance upon conspiracy minded “news” platforms such as Fox News, One America News (OANN), YouTube, Right-Wing Talk Radio, and a myriad of internet black holes of unmitigated ignorance and misinformation.

As long as E/Fs continue to understand the Bible the way they do, this gullibility and lack of discernment as to conspiracy theories will probably abide. An understanding of the Bible as literal truth, or as something we should view like a modern science textbook or encyclopedia, has a tendency to form people prone to conspiracy theories. Why? Because the Bible is not that type of literature. It’s another reason E/Fs tend to be receptive to, and easily manipulated by, television preachers and political leaders (see our current moment).

Here is what I believe these evangelical critics are missing as they rightfully and courageously address this problem in their own camp: A key factor is the underlying theology, specifically a view of the Bible, and how E/Fs understand inspiration, authority, and beliefs like “Scripture alone.” Until they are willing to address those issues, the problem is sure to continue, as it has now, for decades.

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/divergence/2020/06/22/evangelicals-are-attracted-to-conspiracy-theories-why/

Joe: A CHURCH OPERATES AS A BENIGN MOB

Conspiracy theories are popular among evangelicals because they provide psychological cover for their believers from their feelings of submissiveness, timidity, and herd-mindedness of their mob mentality. These feelings give conspiracy followers a feeling of inferiority, and there are key in understanding the mentality of conspiracists.

The feeling of inadequacy is one reason that the educational span ranges from a high-school education to a college education. A perfect example of this inadequacy is Lindsey Graham’s behavior. It isn’t only the fear of their inadequacy that makes conspiracy theories attractive to this personality type. It is the fear that their inadequacy cannot be hidden from the world at large.

Why the evangelicals are more susceptible to conspiracy theories has to do with their religion. A church operates as a benign mob. Every Sunday the preacher demands his congregation be submissive to God or fearing God or humble in God’s presence. The followers must act this way to be in one accord with God’s will.

Fear that makes people timid and acting timid before God is okay, but one must also be timid in front of God’s representative on earth, the preacher. The congregation shows their submissiveness to God by being submissive to the preacher. We see this in people refusing medical treatment or allowing the preacher to molest their children because the preacher tells them this is God’s will.

The religious leaders amplify their control by insisting that their followers believe in the literal interpretation of the Bible. This is a way of restricting freedom of thought and increasing their power. If the churchgoers were encouraged to read the Bible as a metaphor then the common person wouldn’t need a leader to interpret the Bible for them.

An example is the Miracle of the Multiplication of Loaves and Fishes. One simple interpretation of this story is as follows: after a day of preaching, Christ had his disciples gather the food among the people who listened to his sermon.

The time was late in the day, and the crowd was made up of the wealthy and poor citizens as well as soldiers and others. Christ gathered the food blessed it and his followers distributed it to everyone. The crowd ate their fill thank God and went home.

My interpretation, which I got from Albert Schweitzer, is that Christ is a metaphor for God’s love. He had his disciples go into the crowd and gather food. Christ said a blessing and redistributed the food equally among the crowd without any distinction between the rich and the poor or the soldier and the civilian. Everyone received the same amount and had enough food to enable them to walk home. The miracle was not in the quantity of food; it was that Christ was able to have everyone imitate the unconditional love of God.

Oriana:

Voltaire: "Those who make you believe absurdities will make you commit atrocities."

I was also struck by something I read in an article on why people leave the church. I quote from memory: they leave because the church never made them experience the love of Christ.

Only much later I learned that there exist Catholic spiritual exercises meant to make you create a personal relationship with god, e.g. meditating on certain stories from the New Testament. But those were reserved for the church insiders. Young girls didn't count. Or the great majority of the faithful, for that matter. I'm tempted to say all of us never experienced the love of Christ, and had to seek love and the sense of being valued in the world.

PS. I was amazed by your interpretation of the miracle of loaves and fishes. That certainly was not presented to us. Well, even the idea of feeding the crowd is subversive in itself. Free food! We can’t have that. This also reminds me that Jesus healed the sick for free, another scandal.

*

“Say what you will about the sweet miracle of unquestioning faith. I consider the capacity for it terrifying.” ~ Kurt Vonnegut

*

Religion normalizes crazy talk. When you've been taught your whole life that the world could end at any moment, nothing seems completely crazy, or impossible to believe. ~ Neil Carter, Godless in Dixie

*

THE GREAT POTENTIAL OF THE M-RNA TECHNOLOGY

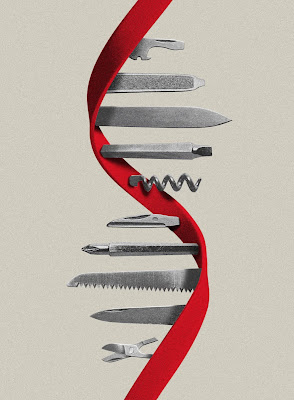

~ Unlike traditional vaccines, which use live viruses, dead ones, or bits of the shells that viruses come cloaked in to train the body’s immune system, the new shots use messenger RNA—the short-lived middleman molecule that, in our cells, conveys copies of genes to where they can guide the making of proteins.

The message the mRNA vaccine adds to people’s cells is borrowed from the coronavirus itself—the instructions for the crown-like protein, called spike, that it uses to enter cells. This protein alone can’t make a person sick; instead, it prompts a strong immune response that, in large studies concluded in December, prevented about 95% of covid-19 cases.

Beyond potentially ending the pandemic, the vaccine breakthrough is showing how messenger RNA may offer a new approach to building drugs.

In the near future, researchers believe, shots that deliver temporary instructions into cells could lead to vaccines against herpes and malaria, better flu vaccines, and, if the covid-19 germ keeps mutating, updated coronavirus vaccinations, too.

But researchers also see a future well beyond vaccines. They think the technology will permit cheap gene fixes for cancer, sickle-cell disease, and maybe even HIV.

For Weissman, the success of covid vaccines isn’t a surprise but a welcome validation of his life’s work. “We have been working on this for over 20 years,” he says. “We always knew RNA would be a significant therapeutic tool.”

PERFECT TIMING

Despite those two decades of research, though, messenger RNA had never been used in any marketed drug before last year.

Then, in December 2019, the first reports emerged from Wuhan, China, about a scary transmissible pneumonia, most likely some kind of bat virus. Chinese government censors at first sought to cover up the outbreak, but on January 10, 2020, a Shanghai scientist posted the germ’s genetic code online through a contact in Australia. The virus was already moving quickly, jumping onto airplanes and popping up in Hong Kong and Thailand. But the genetic information moved even faster. It arrived in Mainz at the headquarters of BioNTech, and in Cambridge at Moderna, where some researchers got the readout as a Microsoft Word file.

Scientists at Moderna, a biotech specializing in messenger RNA, were able to design a vaccine on paper in 48 hours, 11 days before the US even had its first recorded case. Inside of six weeks, Moderna had chilled doses ready for tests in animals.

Unlike most biotech drugs, RNA is not made in fermenters or living cells—it’s produced inside plastic bags of chemicals and enzymes. Because there’s never been a messenger RNA drug on the market before, there was no factory to commandeer and no supply chain to call on.

When I spoke to Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel in December, just before the US Food and Drug Administration authorized his company’s vaccine, he was feeling confident about the shot but worried about making enough of it. Moderna had promised to make up to a billion doses during 2021. Imagine, he said, that Henry Ford was rolling the first Model T off the production line, only to be told the world needed a billion of them.

Bancel calls the way covid-19 arrived just as messenger RNA technology was ready an “aberration of history.”

In other words, we got lucky.

HUMAN BIOREACTORS

The first attempt to use synthetic messenger RNA to make an animal produce a protein was in 1990. It worked but a big problem soon arose. The injections made mice sick. “Their fur gets ruffled. They lose weight, stop running around,” says Weissman. Give them a large dose, and they’d die within hours. “We quickly realized that messenger RNA was not usable,” he says.

The culprit was inflammation. Over a few billion years, bacteria, plants, and mammals have all evolved to spot the genetic material from viruses and react to it. Weissman and Karikó’s next step, which “took years,” he says, was to identify how cells were recognizing the foreign RNA.

As they found, cells are packed with sensing molecules that distinguish your RNA from that of a virus. If these molecules see viral genes, they launch a storm of immune molecules called cytokines that hold the virus at bay while your body learns to cope with it. “It takes a week to make an antibody response; what keeps you alive for those seven days is these sensors,” Weissman says. But too strong a flood of cytokines can kill you.

The eureka moment was when the two scientists determined they could avoid the immune reaction by using chemically modified building blocks to make the RNA. It worked. Soon after, in Cambridge, a group of entrepreneurs began setting up Moderna Therapeutics to build on Weissman’s insight.

Vaccines were not their focus. At the company’s founding in 2010, its leaders imagined they might be able to use RNA to replace the injected proteins that make up most of the biotech pharmacopoeia, essentially producing drugs inside the patient’s own cells from an RNA blueprint. “We were asking, could we turn a human into a bioreactor?” says Noubar Afeyan, the company’s cofounder and chairman and the head of Flagship Pioneering, a firm that starts biotech companies.

If so, the company could easily name 20, 30, or even 40 drugs that would be worth replacing. But Moderna was struggling with how to get the messenger RNA to the right cells in the body, and without too many side effects. Its scientists were also learning that administering repeat doses, which would be necessary to replace biotech blockbusters like a clotting factor that’s given monthly, was going to be a problem. “We would find it worked once, then the second time less, and then the third time even lower,” says Afeyan. “That was a problem and still is.”