photo: Ira Joel Harber

photo: Ira Joel Harber*

AN ALTOGETHER DIFFERENT LANGUAGE

There was a church in Umbria, Little Portion,

Already old eight hundred years ago.

It was abandoned and in disrepair

But it was called St. Mary of the Angels

For it was known to be the haunt of angels.

Often at night the country people

Could hear them singing there.

What was it like, to listen to the angels,

To hear those mountain-fresh, those simple voices

Poured out on the bare stones of Little Portion

in hymns of joy?

Perhaps it needs another language

That we still have to learn,

An altogether different language.

~ Anne Porter (1911-2011)

from Wiki:

Porziuncola, also called Portiuncula (in Latin) or Porzioncula, is a small Catholic church located within the Papal Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels in Assisi in the frazione of Santa Maria degli Angeli, situated about 4 kilometers (2.5 mi) from Assisi, Umbria (central Italy). It is the place from where the Franciscan movement started.

The name Porziuncola (meaning “small portion of land”) was first mentioned in a document from 1045, now in the archives of the Assisi Cathedral.

The original name of Los Angeles was “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles del Río de Porciúncula.”

**

The Miracle of Porziuncola seems to refer to how St. Francis once resisted a temptation by throwing himself onto thorns. This transformed the thorn bush into a thornless rose bush.

Zbigniew Herbert ended one of his poems with these lines

thorns and roses

roses and thorns

we pursue happiness

I admit that what attracted me to this poem was precisely “Little Portion.” But it’s high time to address the poem itself.

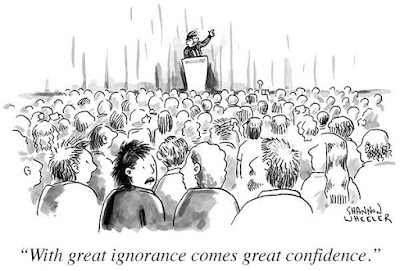

I certainly don’t mean to detract from the legend of the Little Portion being the “haunt of angels,” heard singing by the country people of Umbria. Still, I strongly disagree with the need for “an altogether different language.” Angels are projections of our idealized selves. They are always kind and soft-spoken. Their speech and singing sound oh so sweet, we imagine.

And this leads me to a memory of something I experienced at the Frankfurt Airport on my way to the US when I was 17. I knew a bit of German. Since earliest childhood I could recognize German, one of the languages around me — Poles commonly described it as “barking.” Primo Levi called it “subhuman barking.” A famous Polish poet who shall remain unnamed said that it sounded “really vulgar.”

I didn’t have my first German lessons until I was 16. My very eccentric teacher decided to skip most of the grammar and mundane vocabulary, and proceeded to Goethe and Heine. Soon I was mesmerized by Erlkönig and Lorelei, even if I understood only half the words.

Bear with me. Having grown up with the belief that German was “barking,” it actually took me a while to admit it was a beautiful language — or at least it had many beautiful words. Strangely, it seemed both the ugliest and the most beautiful language I ever heard. Forward to the Frankfurt Airport. Near me sat a German woman and her little daughter. The daughter was a bit pouty. The mother seemed to try to soothe her. She spoke to the child in such a soft, singing way that I was in awe of that music. I didn’t know that, spoken with affection, German could sound *that* beautiful. I was listening to the singing of an angel.

Yes, German has those gorgeous umlauts and long vowels, but my guess is that any language sounds like the singing of angels when spoken softly to someone we love. So we don’t need an “altogether different language.” Any human language will do. Just add love.

The chapel of Porziuncola, "Little Portion" -- originally a small church that St. Francis restored from disrepair.

I feel very attracted to the phrase “Little Portion.” Chide me if you want for “diminished expectations,” for my constant praise of Less, and Think Small. Settling for the “Little Portion” has been my personal salvation from bitterness and depression. Nor is there any feeling of deprivation or scarcity. On the contrary, it’s only thanks to Little Portion that I have fully experienced the richness of enough.

Mary:

Every language has its own music, and I think we hear that music through the filters of experience and history. It is hard to hear the beauty in a language that has been put to terrible purpose, used to promote and normalize atrocity — this is a problem with German. I too find it difficult to hear the music in German, thinking of the barking voices of Nazis and their horrific crimes. Then I remember my grandmother singing us German lullabies, (I assume they were lullabies, I didn't know the words). Maybe the truth is that love is beautiful in any language.

And I'm not sure why, but I never saw angels as gentle guardian creatures. I saw the angel with the flaming sword at Eden's gate, and for me, the angel of the annunciation was no kind messenger — being God’s chosen (any god’s) is not a gift, but a life sentence, leaving you with nothing of your own. If God is a kind of bully, angels are his enforcement squad.

Oriana:

Mary, what a wonderful insight! Yes, it’s love that sounds beautiful in any language.

And great observations on angels. We get imprinted on that famous saccharine of an angel with hands above two small children crossing a rickety wooden bridge, with a missing plank (talk about decaying infrastructure) — or, in another version, the children are on a edge of a cliff — and forget that the first time we encounter an angel in the bible is the angel driving Adam and Eve out of Eden, and then the Cherubim (no harmless little cherubs) barring the way to the Tree of Life with swords of fire.

Masaccio: Expulsion, 1425

Masaccio: Expulsion, 1425THE TWO RUSSIAN MILITARY MEN WHO SAVED THE WORLD

~ “Stanislav Petrov was a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Union's Air Defense Forces, and his job was to monitor his country's satellite system, which was looking for any possible nuclear weapons launches by the United States.

He was on the overnight shift in the early morning hours of Sept. 26, 1983, when the computers sounded an alarm, indicating that the U.S. had launched five nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles.

"The siren howled, but I just sat there for a few seconds, staring at the big, back-lit, red screen with the word 'launch' on it," Petrov told the BBC in 2013.

It was already a moment of extreme tension in the Cold War. On Sept. 1 of that year, the Soviet Union shot down a Korean Air Lines plane that had drifted into Soviet air space, killing all 269 people on board, including a U.S. congressman. The episode led the U.S. and the Soviets to exchange warnings and threats.

Petrov had to act quickly. U.S. missiles could reach the Soviet Union in just over 20 minutes.

"There was no rule about how long we were allowed to think before we reported a strike," Petrov told the BBC. "But we knew that every second of procrastination took away valuable time, that the Soviet Union's military and political leadership needed to be informed without delay. All I had to do was to reach for the phone; to raise the direct line to our top commanders — but I couldn't move. I felt like I was sitting on a hot frying pan."

Petrov sensed something wasn't adding up.

He had been trained to expect an all-out nuclear assault from the U.S., so it seemed strange that the satellite system was detecting only a few missiles being launched. And the system itself was fairly new. He didn't completely trust it.

After several nerve-jangling minutes, Petrov didn't send the computer warning to his superiors. He checked to see if there had been a computer malfunction.

He had guessed correctly.

Petrov died on May 19, at age 77, in a suburb outside Moscow, according to news reports Monday. He had long since retired and was living alone. News of his death apparently went unrecognized at the time.

His story was not publicized at the time, but it did emerge after the Soviet Union collapsed. He received a number of international awards during the final years of his life, and was sometimes called "the man who saved the world."

But he never considered himself a hero.

"That was my job," he said. "But they were lucky it was me on shift that night.”

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/18/551792129/stanislav-petrov-the-man-who-saved-the-world-dies-at-77

from another source:

“It was later determined the false alarms were caused by a rare alignment of sunlight reflecting from clouds, which was mistaken for a missile launch.”

If the world seems insane nowadays, it may be some slight consolation to remember that it used to be even more insane.

We know of yet another hero who averted a nuclear holocaust during the Cuban missile crisis: Vasili Arkhipov.

from Wiki:

~ As flotilla commander and second-in-command of the diesel powered submarine B-59, only Arkhipov refused to authorize the captain's use of nuclear torpedoes against the United States Navy, a decision requiring the agreement of all three senior officers aboard. In 2002 Thomas Blanton, who was then director of the US National Security Archive, said that "Vasili Arkhipov saved the world”.

On 27 October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, a group of eleven United States Navy destroyers and the aircraft carrier USS Randolph located the diesel-powered, nuclear-armed Soviet Foxtrot-class submarine B-59 near Cuba. Despite being in international waters, the Americans started dropping signaling depth charges, explosives intended to force the submarine to come to the surface for identification. There had been no contact from Moscow for a number of days and, although the submarine's crew had earlier been picking up U.S. civilian radio broadcasts, once B-59 began attempting to hide from its U.S. Navy pursuers, it was too deep to monitor any radio traffic. Those on board did not know whether war had broken out or not.[6][7] The captain of the submarine, Valentin Grigorievitch Savitsky, decided that a war might already have started and wanted to launch a nuclear torpedo.[8]

Unlike the other subs in the flotilla, three officers on board the B-59 had to agree unanimously to authorize a nuclear launch: Captain Savitsky, the political officer Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov, and the second-in-command Arkhipov. Typically, Russian submarines armed with the "Special Weapon" only required the captain to get authorization from the political officer to launch a nuclear torpedo. However, due to Arkhipov's position as flotilla commander, the B-59's captain also was required to gain Arkhipov's approval. An argument broke out, with only Arkhipov against the launch.[9]

Even though Arkhipov was only second-in-command of the submarine B-59, he was in fact commander of the entire submarine flotilla, including the B-4, B-36 and B-130, and equal in rank to Captain Savitsky. According to author Edward Wilson, the reputation Arkhipov had gained from his courageous conduct in the previous year's Soviet submarine K-19 incident also helped him prevail. Arkhipov eventually persuaded Savitsky to surface and await orders from Moscow. This effectively averted the nuclear warfare which probably would have ensued if the nuclear weapon had been fired. The submarine's batteries had run very low and the air-conditioning had failed, causing extreme heat and high levels of carbon dioxide inside the submarine. They were forced to surface amidst its U.S. pursuers and return to the Soviet Union as a result.” ~

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasili_Arkhipov

Oriana:

Shouldn’t we have statues to honor Arkhipov and Petrov, and who knows how many American heroes like them (probably still classified info). Imagine — statues to those saviors of humanity rather than to Confederate traitors . . .

WHY MEDIEVAL STAIRWAYS WERE CLOCKWISE

~ “Stairwells were often very carefully designed in medieval castles. Stairwells that curved up to towers often curved very narrowly and in a clockwise direction. This meant that any attackers coming up the stairs had their sword hands (right hand) against the interior curve of the wall and this made it very difficult for them to swing their swords. Defenders had their sword hands on the outside wall, which meant they had more room to swing. Another ingenious design of stairs was that they were designed with very uneven steps. Some steps were tall and other steps were short. The inhabitants, being familiar with the uneven pattern of the stair heights could move quickly up and down the stairs but attackers, in a dimly lit stairwell, would easily fall and get bogged down in the stairwells. This made them vulnerable to attacks and slowed their attacks down significantly.” ~

http://www.thevintagenews.com/2016/08/03/the-secrets-of-medieval-castles-stairs-are-built-in-a-clockwise-fashion-for-a-very-good-reason/

Oriana:

This is fantastically clever — but how tragic that human genius had to be applied to such problems.

By the way, the main function of the moat was to prevent digging tunnels under the walls.

And the bride on the left side so the man’s “sword hand” would be free for action, if required. Brilliant, yes, but just tragic.

Not even angels were exempt from military duties

angel statue by Raffaello de Montelupo, 16th century, Castel Sant'Angelo — note the elementary armor; originally there was probably a sword or a lance in the angel’s right hand — the military-religious complex

angel statue by Raffaello de Montelupo, 16th century, Castel Sant'Angelo — note the elementary armor; originally there was probably a sword or a lance in the angel’s right hand — the military-religious complexMEMOIRS OF DYING: ONE WOMAN’S EXPERIENCE

~ “The questions, as it turned out, were unsurprising. Did I have a bucket list, had I considered suicide, had I become religious, was I scared, was there anything good about dying, did I have any regrets, did I believe in an afterlife, had I changed my priorities in life, was I unhappy or depressed, was I likely to take more risks given that I was dying anyway, what would I miss the most, how would I like to be remembered? These were the same questions I’d been asking myself ever since I was diagnosed with cancer, back in 2005. And my answers haven’t changed since then. They are as follows.

No, I don’t have a bucket list. From the age of fifteen, my one true ambition in life was to become a writer. It is my bliss, this thing called writing, and it has been since my school days. It isn’t just the practice that enthralls me—it’s everything else that goes with it, all the habits of mind.

Writing, even if, most of the time, you are only doing it in your head, shapes the world, and makes it bearable. As a schoolgirl, I thrilled at the power of poetry to exclude everything other than the poem itself, to let a few lines of verse make a whole world. In fiction, for much of the time you are choosing what to exclude from your fictional world in order to make it hold the line against chaos. And that is what I’m doing now: I am making a shape for my death, so that I, and others, can see it clearly. And I am making dying bearable for myself.

*

Yes, I have considered suicide, and it remains a constant temptation. If the law in Australia permitted assisted dying I would be putting plans into place right now to take my own life. Once the day came, I’d invite my family and closest friends to come over and we’d have a farewell drink. I’d thank them all for everything they’ve done for me. I’d tell them how much I love them. I imagine there would be copious tears. I’d hope there would be some laughter. There would be music playing in the background, something from the soundtrack of my youth. And then, when the time was right, I’d say goodbye and take my medicine, knowing that the party would go on without me, that everyone would stay a while, talk some more, be there for each other for as long as they wished. As someone who knows my end is coming, I can’t think of a better way to go out. Nor can I fathom why this kind of humane and dignified death is outlawed.

*

No, I haven’t become religious; that is, I haven’t experienced a late conversion to a particular faith. If that means I’m going straight to hell when I die, then so be it. One of my problems with religion has always been the idea that the righteous are saved and the rest are condemned. Isn’t that the ultimate logic of religion’s “us” and “them” paradigm?

Perhaps it’s a case of not missing what you have never had. I had no religious instruction growing up. I knew a few Bible stories from a brief period of attendance at Sunday school, but these seemed on a level with fairy tales, if less interesting. Their sanctimoniousness put me off. I preferred the darker tones of the Brothers Grimm, who presented a world where there was no redemption, where bad things happened for no reason, and nobody was punished. Even now I prefer that view of reality. I don’t think God has a plan for us. I think we’re a species with godlike pretensions but an animal nature, and that, of all of the animals that have ever walked the earth, we are by far the most dangerous.

Cancer strikes at random. If you don’t die of cancer you die of something else, because death is a law of nature. The survival of the species relies on constant renewal, each generation making way for the next, not with any improvement in mind, but in the interests of plain endurance. If that is what eternal life means, then I’m a believer. What I’ve never believed is that God is watching over us, or has a personal interest in the state of our individual souls. In fact, if God exists at all, I think he/she/it must be a deity devoted to monumental indifference, or else, as Stephen Fry says, why dream up bone cancer in children?

*

Yes, I’m scared, but not all the time. When I was first diagnosed, I was terrified. I had no idea that the body could turn against itself and incubate its own enemy. I had never been seriously ill in my life before; now suddenly I was face to face with my own mortality. There was a moment when I saw my body in the mirror as if for the first time. Overnight my own flesh had become alien to me, the saboteur of all my hopes and dreams. It was incomprehensible, and so frightening, I cried.

“I can’t die,” I sobbed. “Not me. Not now.”

But I’m used to dying now. It’s become ordinary and unremarkable, something everybody, without exception, does at one time or another. If I’m afraid of anything it’s of dying badly, of getting caught up in some process that prolongs my life unnecessarily. I’ve put all the safeguards in place. I’ve completed an advanced health directive and given a copy to my palliative-care specialist. I’ve made it clear in my conversations, both with him and with my family, that I want no life-saving interventions at the end, nothing designed to delay the inevitable. My doctor has promised to honor my wishes, but I can’t help worrying. I haven’t died before, so I sometimes get a bad case of beginner’s nerves, but they soon pass.

*

No, there is nothing good about dying. It is sad beyond belief. But it is part of life, and there is no escaping it. Once you grasp that fact, good things can result. I went through most of my life believing death was something that happened to other people. In my deluded state, I imagined I had unlimited time to play with, so I took a fairly leisurely approach to life and didn’t really push myself.

*

Yes, I have regrets, but as soon as you start rewriting your past you realize how your failures and mistakes are what define you. Take them away and you’re nothing. But I do wonder where I’d be now if I’d made different choices, if I’d been bolder, smarter, more sure of what I wanted and how to get it. As it was, I seemed to stumble around, making life up as I went along. Looking back, I can make some sense of it, but at the time my life was all very makeshift and provisional, more dependent on luck than on planning or intent.

Still, as the British psychotherapist and essayist Adam Phillips says, we are all haunted by the life not lived, by the belief that we’ve missed out on something different and better. My favorite reverie is about the life I could have led in Paris if I’d chosen to stay there instead of returning home like I did. I was twenty-two.

The problem with reverie is that you always assume you know how the unlived life turns out. And it is always a better version of the life you’ve actually lived. The other life is more significant and more purposeful. It is impossibly free of setbacks and mishaps. This split between the dream and the reality can be the cause of intense dissatisfaction at times. But I am no longer plagued by restlessness. Now I see the life I’ve lived as the only life, a singularity, saturated with its own oneness. To envy the life of the alternative me, the one who stayed in Paris, seems like the purest kind of folly.

Van Gogh: Olive Orchard, June 1889

Van Gogh: Olive Orchard, June 1889*

No, I don’t believe in an afterlife. Dust to dust, ashes to ashes sums it up for me. We come from nothingness and return to nothingness when we die. That is one meaning of the circle beloved of calligraphers in Japan, just a big bold stroke, starting at the beginning and traveling back to it in a round sweep. In my beginning is my end, says T. S. Eliot. Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth / Which is already flesh, fur and faeces / Bone of man and beast, cornstalk and leaf. When I first read “Four Quartets,” at school, it was like a revelation. The world was just as he described it and no other way, a place where beauty and corruption cohabit and are often indistinguishable.

I’m much more drawn to all of the ordinary ways in which we cheat death. It might be through the evocative power of the objects we leave behind, or it might be in a form of words, a turn of the head, a way of laughing. I was sitting at dinner the other night with some very old friends of ours. They’d met my mother many times, back when she was still herself, before she became ill. The wife looked hard at me for a while.

“You get more and more like her,” she said.

It felt for a moment as if my mother had joined us, that us all being together had conjured up her presence at the table. It was only a fleeting thing. But then I can’t imagine an afterlife that consists of anything more than these brief and occasional visits with the living, these memories that come unbidden and out of nowhere, then vanish again into oblivion.

*

No, my priorities remain the same. Work and family. Nothing else has ever really mattered to me.

To say that family has been my other chief priority in life is to understate the case. Marriage, children, the whole catastrophe, as Zorba called it. To become a mother is to die to oneself in some essential way. After I had children, I was no longer an individual separate from other individuals. I leaked into everyone else. I remember going to a movie soon after Nat was born and walking out at the first hint of violence. It was unbearable to think of the damage done. I had never been squeamish in my life before, but now a great deal more was at stake. I had delivered a baby into the world. From now on my only job was to protect and nurture him into adulthood, no matter what it cost me. This wasn’t a choice. It was a law.

That makes it sound like a selfless task, but it wasn’t. I got as much as I gave, and much more. The ordinary pleasures of raising children are not often talked about, because they are unspectacular and leave no lasting trace, but they sustained me for years as our boys grew and flourished, and they continue to sustain me now. I can’t help but take pleasure in the fact that my children are thriving as I decline. It seems only fitting, a sure sign that my job in the world is done. It’s like the day Dan, then in the fourth grade, turned to me twenty yards from the school gate and said, “You can go now, Mum.” I knew then that the days of our companionable walks were over, and that as time went by there would be further signs of my superfluity, just as poignant and necessary as this one.

*

No, I am not unhappy or depressed, but I am occasionally angry. Why me? Why now? Dumb questions, but that doesn’t stop me from asking them. I was supposed to defy the statistics and beat this disease through sheer willpower. I was supposed to have an extra decade in which to write my best work. I was robbed!

Crazy stuff. As if any of us are in control of anything. Far better for me to accept that I am powerless over my fate, and that for once in my life I am free of the tyranny of choice. That way, I waste a lot less time feeling singled out or cheated.

As I told the young psychologist, I rely on friends to divert me from dark thoughts. I don’t have a lot of friends, but the ones I do have are so good to me, so tender and solicitous, it would seem ungrateful to subside into unhappiness or depression.

*

No, I’m not likely to take more risks in life, now that I know I’m dying. I’m not about to tackle skydiving or paragliding. I’ve always been physically cautious, preternaturally aware of all the things that can go wrong when one is undertaking a dangerous activity.

The irony is that, despite my never having tempted death the way daredevils do, I’m dying anyway. Perhaps it is a mistake to be so cautious. I sometimes think this is the true reason for my reluctance to take my own life. It is because suicide is so dangerous.

*

I will not miss dying. It is by far the hardest thing I have ever done, and I will be glad when it’s over.” ~

*

Cory Taylor, an Australian writer, was the award-winning author of “Me and Mr. Booker,” “My Beautiful Enemy,” and “Dying: A Memoir.” She died of melanoma on July 5, 2016. She was 61.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/personal-history/questions-for-me-about-dying?mbid=social_facebook_aud_dev_kw_paid-questions-for-me-about-dying&kwp_0=521631&kwp_4=1866166&kwp_1=789788

It’s been a strange summer. It started with a major surgery that I thought might be the end of me: I was haunted by an automatic imagery of having a heart attack in the middle of it, hearing the anesthesiologist say, slowly, “We’ve lost her.” Those words like a tolling bell, for lack of a tolling bell. But I did wake up, realized I’d made it, and smiled a big smile. Toward the end of July, though, a neighbor I’d known for thirty years, and who seemed like the kind who’d live to one hundred — so fit and lively, curious, always active — died of a sudden heart attack. He never recovered consciousness. The first week of September, a friend who was only 60 died of a ruptured aneurysm. She fainted and never regained consciousness.

And, as always, but perhaps more intensely than “always,” the news with apocalyptic overtones. A summer saturated with mortality. Would I want to cease suddenly, in midst of ordinary life, or slide away slowly? Of course there won’t be a choice. That’s the good part.

My neighbor’s last words to me — what in effect became his last words — were: “So, are you planning to travel?” And Jordan: such a rich, daring life. I feel timid by comparison.

And yet, always the same consolation: I have written some fine poems. They will eventually be forgotten, but I like to say, with Hölderlin:

Once I lived as the gods.

More is not needed.

What a gift, those two luminous lines, worth more than volumes written about creativity.

And also these two lines by Milosz:

The history of my stupidity will not be written.

For one thing, it’s late. And the truth is laborious.

And the most recent gift, this beautiful statement by Cory Taylor: “Now I see the life I’ve lived as the only life, a singularity, saturated with its own oneness. To envy the life of the alternative me, the one who stayed in Paris, seems like the purest kind of folly.”

Insert Warsaw for Paris, and that’s me. Am I entirely done envying the life of “the alternative me, the one who stayed in Warsaw?” I hope I am, though some regret flickers now and then, perhaps out of sheer habit. But it’s too late for regret. And besides, that wouldn’t be “me.” I would have become a different person — one who’d regret not having acted on the chance of going to the U.S. The symmetry of this irony (I typed “agony”) is a bitter delight (I typed “delete”). Like strong coffee, it wakes me up.

Mary:

It has always been a comfort to me that dying is something very ordinary, something everybody does . . . how hard can it be?? Not dying is not a choice, is not natural for anything alive. I can understand the fear, as it is terrifying to imagine yourself Gone, and when we witness death the difference between life and death is so absolute, so stunning, there is the feeling something enormous has just gone and left the body, empty, behind. The immediate feeling is — where did all that something, that force, that energy, that coherence, go??? It is almost impossible to believe it has simply disappeared. And so we have stories we tell ourselves about dying and not dying, making sense of what we can't fully understand.

That is also the problem with the randomness of death, not just accidental deaths, but deaths we see as being "out of order" in some way. The mother who outlives all her children, the seemingly healthy suddenly struck down by a catastrophic physical event like an aneurysm, the child who suffers and dies with cancer — all challenge us to make sense of them. Because we always want to make sense of things. We make stories, coherent narratives, out of our lives, and tell them to ourselves and each other. We can't stand to see life, history on a personal scale or a universal scale as "just one damn thing after another." No plot, no meaning, no structure, no plan — it drives us crazy.

Oriana:

Dying takes care of itself, a natural process like any other. The founding idea of the hospice movement is perfect: don’t interfere, just relieve pain. “Unlimited pain relief” — the only irony is that we have to be dying to be allowed unlimited pain relief, stingily doled out until then.

Of course you don’t have to be told that the “life force” doesn’t go anywhere. It simply ceases, the way flame ceases when the fuel is gone. And, as Edna St. Vincent-Millay reminds us, the question is not how long the flame lasted, but whether it gave off a beautiful light.

**

"One world at a time." ~ Henry David Thoreau, on being asked about the afterlife

The Eternalists versus the Perishables: Eternal life and truth versus This too shall pass. That’s the core culture war. ~ Jeremy Sherman

Plato, the Eternalist-in-Chief

Plato, the Eternalist-in-Chief**

“Never fear that your insights are wrong. Many are. It’s a percentage game. Be intrepid.” ~ Jeremy Sherman

Oriana:

Some people strangely believe that intuition can never be wrong -- as if they never had a premonition that didn't come to pass. Many of us "intuitively knew" that Trump would never become president. Maybe that's part of the reason it hurt so much -- that cherished if tacit belief in the infallibility of intuition was dealt a huge blow. And when it comes to insight, it's all the more so -- how could this eye-opening, sometimes even life-changing moment be off the mark after all? But you are absolutely right -- human, all too human.

But it’s impossible to live without relying on intuition to a huge degree. And it would be a sad life if we were to be deprived of those marvelous flashes of insight. So yes, a percentage game. Intrepid, we carry on. But we would be wise to remember our fallibility.

One of the thousands of toppled Lenin statues in Ukraine

One of the thousands of toppled Lenin statues in UkraineTHE DREAM OF TWO RIVERS

I was visiting a friend who lives in a semi-rural area near Monterey. She was sitting outdoors, in her spacious woodland-like yard, at an old wooden table she was using more like a desk, were through a magazine. She pointed a photo of a long purple cotton skirt to me, the breezy kind that started as a summer skirt but later became all-season in California, somewhat bohemian but nothing extreme. “Remember the time when we all wanted skirts like that?” she said. “I’d still want a skirt like that,” I replied.

And off I went for a walk (unsupported — no walker, no cane, no walking sticks) through the woodland, and walked without pain until I came to a place where a rushing stream split off into two “young rivers.” Most people would call them mountain streams — rushing onward, fast and loud, full of boulders. I was so excited by the sight that I hurried back to my friend and suggested we both walk to see the rivers— though it was getting late in the day, the first signs of dusk already apparent.

The dream ended with me, impractically, urging her to come along — I couldn’t wait to see the magical place again! She was comfortably ensconced at her table, it was getting late, but I was just so enraptured. And no pain! Alas, that wasn’t completely true when I woke up, but the kind of pain I experience now could be called mere “discomfort” compared to the pain of the first two months, and during my two agonizing setbacks.

After waking, it occurred to me that both the skirt and the rivers were symbols of youth. I tend to think of mountain streams as “young rivers” — and in my dream, I was naming the streams “rivers.” It was a dream of two rivers, but above all of “young rivers.”

We speak of “second childhood,” but obviously no one wants that. On the other hand, I'm not the only one who has spoken of the “second youth.” Why two rivers? Maybe precisely to indicate the first youth and the second youth.

Mary:

I love your dream. Water is always such a healing image. I have had several dreams about walking in a river, in the shallows near the shore, but for miles and miles. The sense of freedom and wonder in these dreams is healing in itself. When my father was dying I dreamed of walking in the river with him, toward the sea, where I knew he would go on and I would not.

JESUS AS AN APOCALYPTIC PROPHET (“heavenly forces joined by human forces”)

~ “The biblical books of Mark and Luke both state that at least one (and probably two or more) of Jesus’s followers was carrying a sword when Jesus was arrested shortly after the Last Supper, at the time of the Jewish festival of Passover. One disciple, Simon Peter, even used his sword to cut off the ear of one of those arresting Jesus, according to the Gospel of John.

Why were Jesus’s followers armed at all, especially during a religious festival?

Dale Martin makes the case that Jesus and his followers were likely expecting that an apocalyptic showdown was on the horizon, one in which divine forces (in the form of angels) would destroy Rome and Herod’s temple and usher in a holy reign. And this might require some fighting by Jesus’s disciples, he adds.

It sounds pretty far-out, but a similar scenario is described in parts of the Book of Revelation. And this scenario of “heavenly forces joined by human forces...was an expectation in a central document of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” a group of texts that shed light on the thinking of various Jewish peoples around the time of Jesus, Martin adds.

Indeed, many academics who study the historicity of the Bible believe “that Jesus was an apocalyptic Jewish prophet who was expecting an imminent arrival of the kingdom of God on Earth,” Martin says.

The paper also suggests that Jesus may have been in favor of fighting, at least in this apocalyptic instance, Ehrman tells Newsweek.

“It’s making me rethink my view that Jesus was a complete pacifist,” he says. “And it takes a lot for me to change my views about Jesus.” ~

http://www.newsweek.com/2014/10/17/jesus-was-crucified-because-disciples-were-armed-bible-analysis-suggests-271436.html

Oriana:

The view of Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet is especially inspiring to the lunatic fringe — people who for some reason wish for mayhem so that a chosen minority may enter paradise.

Islam too has its apocalyptic school. Isa (Jesus) is supposed to descend from the clouds, leading a heavenly army that will defeat the armies of Rome (Rome = America and the West in general, but chiefly America).

Failed prophecy never seems to deter a true believer. Prophets are like Trump — they can proclaim any absurdity, and never lose credibility among their followers.

And prophets never apologize -- again, like Trump. Perhaps prophets were Trump's secret role models — no absurdity is too far out, no need to provide convincing evidence. Just assert, assert, assert. We live in an era of Trumps and Trumpets.

The newest prediction is already getting out of date: Rapture was supposed to take place this Saturday, 9/23/2017.

WHY CALORIE RESTRICTION LENGTHENS LIFE SPAN: METHYLATION DRIFT

Scientists have known since the 1930s that calorie restriction helps mammals stay healthy and live longer. But the mechanisms behind this have been a mystery, until now. Researchers, in a groundbreaking study out of Temple University in Philadelphia, found it has to do with an epigenetic phenomenon known as “methylation drift.”

DNA methylation is the process by which genes are expressed or suppressed. These are chemical markers that essentially activate certain genes by tagging them. The tags will tell a cell what type it will become, whether a blood or skin cell, or what-have-you. They also tell it what operations it will perform and when to perform them.

It’s important when DNA is replicated whether the right genes are turned on or off. Normal methylation is important for our growth and development. But abnormal methylation can cause certain diseases such as lupus, muscular dystrophy, and cancer. As we grow older, methylation begins to drift. Also called epigenetic drift, this is when a buildup of tags occurs within a certain gene, making its expression less pronounced.

Methyl tags "tell the cell what to do and when to do it.” If they’re missing or changed, the identity of the cell erodes. “Methylation 'drift' is a composite measure of how much these tags have changed," Dr. Issa said.

The scientists looked at the “gains and losses of DNA methylation,” along each subject’s genome. While younger subjects had more gains in certain locations, older ones had more losses. Researchers found that the more times a gene was tagged through methylation, the less the gene was expressed. Conversely, the fewer times it was tagged, the more it was expressed.

Next, scientists wanted to see if a restricted calorie diet might increase a mammals’ lifespan. They reduced the caloric intake of mice by 40%. These were almost three and a half months old. The mice stayed on the diet until they were two to three years-old.

Rhesus monkey subjects were between ages seven and 14 and their caloric intake was restricted 30%. The monkeys stayed on the diet until they were between 22 and 30. Though the mice made modest gains, the monkey’s methylation age turned out to be seven years younger than their chronological one. Methylation changes in both species resembled that of younger animals.

http://bigthink.com/philip-perry/heres-why-calorie-restriction-makes-us-live-longer

Oriana:

Intensive exercise also affects methylation -- as does strong coffee. We are barely beginning to understand the mechanisms of aging: what hastens it and what delays it.

Ending on beauty:

That day I saw beneath dark clouds

The passing light over the water

And I heard the voice of the world speak out

I knew then as I have before

Life is no passing memory of what has been

Nor the remaining pages of a great book

Waiting to be read

It is the opening of eyes long closed . . .

Opened at last

Fallen in love

With Solid Ground.

~ David Whyte

photo: David Whyte

photo: David Whyte

No comments:

Post a Comment