THE MOST OF IT

He thought he kept the universe alone;

For all the voice in answer he could wake

Was but the mocking echo of his own

From some tree-hidden cliff across the lake.

Some morning from the boulder-broken beach

He would cry out on life, that what it wants

Is not its own love back in copy speech,

But counter-love, original response.

And nothing ever came of what he cried

Unless it was the embodiment that crashed

In the cliff's talus on the other side,

And then in the far distant water splashed,

But after a time allowed for it to swim,

Instead of proving human when it neared

And someone else additional to him,

As a great buck it powerfully appeared,

Pushing the crumpled water up ahead,

And landed pouring like a waterfall,

And stumbled through the rocks with horny tread,

And forced the underbrush — and that was all.

~ Robert Frost

Here is Milosz’s response to the poem:

“[It shows] how very alone man is in relation to nature, which is absolutely indifferent to him, even though he wishes to receive some sign of understanding. Alone, not only in relation to nature, because each “I” is isolated from all others, as if it were the sole ruler of the universe and seeks love in vain, while what it takes to be a response is only the echo of his own hope.” (“Robert Frost” in Selected Essays).

When it comes to the first two-thirds or so of the poem, I am with both Milosz and Frost himself. “He thought he kept the universe alone” — such a thought never occurred to me, and it strikes me as masculine and “dominionist,” but we have to take the speaker — who seems similar to the speaker in Stevens’s “Snowman” — at face value. As Milosz himself observed elsewhere, man has a great sense of solitude as a species — there is no “soulmate” species anywhere else on earth.

Cats and dogs? They can respond to us emotionally, but not on an intellectual level. (Would we want them to? Can you imagine being criticized by your cat?)

The speaker yearns for a conversation. “He thought he kept the universe alone” can be interpreted not as an arrogant expression of dominion, but rather as a lament about being the most intelligent species with no equal with whom to carry on a conversation.

He thought he kept the universe alone;

For all the voice in answer he could wake

Was but the mocking echo of his own

From some tree-hidden cliff across the lake.

All he gets is an echo. Personally I enjoy the phenomenon of the echo, and love to hear it. But if you live in the country and are used to the echo, maybe the magic of it wears off.

Rather than hearing an echo of his own voice, the speaker wants an “original response” he can’t predict:

Some morning from the boulder-broken beach

He would cry out on life, that what it wants

Is not its own love back in copy speech,

But counter-love, original response.

Again, I am not sure I’d want the cliff to say something like, “A beautiful day, isn’t it?” Also, even if rocks had intelligence, the cliff would reply in its own rock language, with, I assume, hard, dense sounds. No, I'm not mocking the speaker, only trying to imagine the possibilities.

The speaker does not feel a union with nature; he feels separate, alone. And yet, doesn’t he love nature? Don’t we know it from Frost’s other poems? He is not indifferent to the beauty of the forest, for instance. But he wants “counter-love.” He apparently wants nature (or some being out there in nature) to love him back. Yet nature is notoriously indifferent and responds only with beauty. Worse, its indifference to the joy or suffering of living things (though living things also ARE nature, so there is a complication here) can show itself in blatant light: in this poem, the speaker cries out from “the boulder-broken beech.” A boulder fell and broke a tree — it happens.

Note how the triple alliteration — “boulder-broken beech” — calls attention to this image. Until the masculine “great buck” appears, that (feminine?) boulder-broken tree stands for life in nature, and the harm that nature casually inflicts (maybe the broken tree also stands for the speaker’s wife, but that’s a more remote connection).

So we have a love-hate relationship with nature. But later in the poem we learn that the speaker is actually thinking of a human counter-response. If nature can’t be humanized and remains indifferent, at least there could be another human out there, a lively companion.

But there is no Eve for this lonely Adam. Yet one time another being did emerge: a large deer swam in the speaker’s direction, and then disappeared in the brush:

Instead of proving human when it neared

And someone else additional to him,

As a great buck it powerfully appeared,

Pushing the crumpled water up ahead,

And landed pouring like a waterfall,

And stumbled through the rocks with horny tread,

And forced the underbrush — and that was all.

Excuse me, Mr. Frost, I want to say. You watch a powerful buck swim toward you and come ashore, the water “pouring like a waterfall” from the antlers and the whole magnificent body — and your response is “And that was all”?

That’s it. That’s all. There ain’t no more. Atheists are forever being confused with nihilists because they don’t believe in the afterlife, the pie in the sky, a detachable immortal soul independent of the brain (never mind the brain no longer exists; the soul is brain-free). No, the atheists have the nerve to claim that when brain function ceases, consciousness ceases. It doesn’t “go” anywhere; it simply ceases the way flame doesn’t go anywhere, but ceases to be when the fuel that supported it is gone.

To atheists, this world and this life is indeed all there is — but then the universe seems more than enough. Just the earth is almost too much, overwhelming in its beauty and variety. Just the whirl of perceptions seems to be enough to make life worth living, out of simple curiosity. But to see a “great buck as it powerfully appeared” — the marvelous animal swimming, then climbing out, water pouring from his body” — that is more than enough. That is a feast.

*

“As a great buck it powerfully appeared”

~ when I read the poem for the first time, for a moment I was confused. Was it a buck, or something like [“as”] a buck? But the lines that follow leave no doubt that it was a spectacular buck:

As a great buck it powerfully appeared,

Pushing the crumpled water up ahead,

And landed pouring like a waterfall,

And stumbled through the rocks with horny tread,

And forced the underbrush

So yes, that noise was not a rock falling into the water, but a full-grown buck that swims across, then lands “pouring like a waterfall” — and the speaker feels no sense of wonder and delight? Instead, he’s disappointed: “And that was all.”

And yet, the contradiction: the magnificent poetic language used to describe the buck, e.g. “pushing the crumpled water up ahead,” belies the dismissive last phrase. And the more times I read those lines, the more I sense the concealed wonder. Should we take Frost at face value, or yield to the power of the poetic language? It seems to convey a message that is directly contrary to what the poem is ostensibly trying to say.

In summary: Frost’s language and imagery contradict the explicit final statement. The language and the imagery — the “poetry” of the poem — reveal the grandeur of nature. And that, indeed, is all — but that is more than enough. It’s not possible to experience that grandeur and be disappointed.

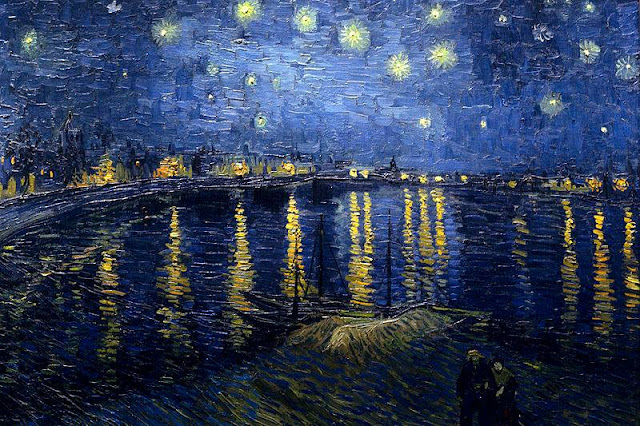

Franz Marc, Deer in the Forest

*

But let’s try a psychological approach here. Of course if someone is used to seeing swimming bucks climb on shore, that sight might get to feel ordinary. But this seems to have happened only once. “And that was all”?

I have only one psychological guess to offer: the speaker is suffering from depression and can’t — or isn’t willing to — rise above bitterness. We need to take a look at Frost’s personal life. I do it with reluctance, since in college we were taught to stay away from biography and try to read the poem as a purely esthetic product, but here biography forces itself on us like a large boulder.

Frost’s father drank and bullied his wife. The biography in the Norton Anthology refers to “sporadic brutality.” The father died young, leaving his wife and children in financial hardship. Depression ran in Frost’s family. Both his mother and Frost himself suffered from it. His younger sister became mentally ill and had to be committed to a hospital. His wife Elinor also had bouts of depression and died relatively young. One son committed suicide; one daughter became mentally ill. Of the six children, only two outlived the poet.

Various business ventures, such as poultry farming, all failed (though Frost later secured a university teaching job and gained increasing fame). Elinor was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1937. A year later she died of heart failure. Frost began to drink heavily; the teaching job at Middlebury College seems to have rescued him.

At Middlebury, he appears to have had an affair with the wife of a faculty member, and to have proposed to her. But she refused to leave her husband, though she remained the poet’s confidante. Frost lived alone until his death in 1963.

Frost was intensely private, but we can safely say that he had an unhappy childhood and later an unhappy marriage. There is stoicism in his poems, and only sometimes bitterness or immense sadness. There is wisdom, as in all great poetry. There is lyricism (“the woods are lovely, dark and deep”). But a true sense of joy is rare.

Having said all this, I am still astounded that in the poem Frost does not celebrate seeing the buck. True, the poem sets out to develop a certain theme, that of complete human loneliness and not receiving a “counter-love, an original response.” Nevertheless, it’s still imaginable that even a short poem can make a turn from dejection to a sense of wonder and excitement. Wordsworth might start “lonely as a cloud,” but would certainly not dismiss seeing a magnificent buck with “and that was all.”

Only Stevens, perhaps, might be equally dismissive of the so-called “grandeur of nature.” Stevens too seemed to yearn for a soul-mate, but settled for an imaginary lover, an “interior paramour.” Stevens, who had a terrible marriage, perhaps the worst one on record as poets’ marriages go. When the marriage is bad, nothing can quite make up for it.

THE NOISY BUCK AND THE SILENCE OF GOD

All this, a reader might argue, is an evasion of the modern man’s despair at the silence and apparent absence of god. Frost was baptized in a Swedenborgian Church of New Jerusalem, but left it when he reached adulthood. No one would call Frost a religious poet.

Not in the traditional sense. He was a poet of this world, but not quite in the sense of celebrating the world. He comes close to being the American Larkin, seeing darkness more often than light.

Still, when the speaker calls out and only the echo of his voice comes back to him, does it not sound like “calling out to god” to give some sign, even the slightest, of his existence and — dare we say it? — not just existence, but caring for the speaker? Some capacity for a personal relationship?

The Swedenborgian version of Christianity is Christ-centered. Yahweh has somehow disappeared. It’s Christ, the “human form divine,” who rules the universe. Swedenborgian heaven and hell reflect states of mind, and a soul in hell (which has no fire, but looks rather like a dilapidated section of town) is not doomed to remain there. Though Frost left the Swedenborgian church, it’s not likely that he found the doctrines emotionally and morally abhorrent — they simply aren’t.

If anything, the doctrines are emotionally appealing — just improbable. I suspect Frost left simply because he could find no evidence of a benevolent supra-personal ruler. Unlike Swedenborg with his mystical visions, Frost sensed no such presence. Nor could he perceive events such as his mother’s death or his sister’s insanity as simply a reflection of his own negative states of mind (not that Swedenborg is ever as extreme as some New Age writers).

Still, there is human love, and there is the beauty of nature. But the beauty of nature may not be enough if the failure of love goes deep enough. Can a bad marriage blot out even the Wow! response that the average person would have if a large buck suddenly climbed out not far from them, water not just dripping but pouring from his antlers and his body — “landed pouring like a waterfall”?

I am not entirely convinced. On the esthetic level, I realize that the poet wished to maintain a consistently bleak tone throughout. Whether he wants a deity or a human lover, and gets “only” a powerful buck, we must accept the disappointment of “And that was all.” No transcendentalism for Frost, no Wordsworthian Nature worship (Nature needs to be spelled with a capital N when mentioned in relation to Wordsworth). Wordsworth would find the buck sublime; Frost acknowledges that the buck is powerful, but — a deer is only a deer, and not a “dear” (groan, yes; well, I just had to). It is not “another self” that the speaker craves.

Are we to universalize from this poem and conclude that we are alone — and I mean really ALONE? Are we to ponder morosely how every person is an isolated individual, and nature can offer only the echo of our voice and, instead of soft, responsive lover, the brute roughness of a buck crashing through the underbrush (the buck “forces” the underbrush, as if a rape were involved)? That’s perhaps the “moral” of this poem, but we need not accept it.

I know depression well. It’s a rare human being who manages to live through life without “getting acquainted with the night,” to use another of Frost’s tropes. Depression can get so deep that all positive memories are blocked and thinking becomes downright delusional under the burden of sadness.

And yet a part of our consciousness (some select neural pathways, if we want to turn to brain function here) is not depressed. It’s a fascinating phenomenon, and I know I'm not the only one who’s experienced it. A part of you is never depressed, but simply watches the drama of spiraling down and down. I call that part of consciousness the Witness (by interesting coincidence, I came up with the name myself, before learning of the Buddhist terminology of the Witness).

The Witness knows all along that human love and caring exist, and life is worth living no matter what. The Witness could never dismiss the buck’s swimming and climbing out, “pouring like a waterfall,” as nothing remarkable — in fact a disappointment. But it cannot be a disappointment — it is a magnificent once-in-a-lifetime sight. Besides, most of us have at least some human love in our lives, so we can appreciate the non-human nature for what it is.

And yet I am still grateful to Frost for having described the incident. Thanks to the poem, the buck is now part of my psyche, along with all the actual deer I’ve enjoyed seeing. They can indeed be noisy moving through the underbrush, but does anyone mind that? And regardless of what the poem says, I am sure that the memory of that buck was special to Frost. He chose to cultivate a bleak persona. But to be a real poet, as Frost certainly was, you need to have a sense of enchantment. So I can pity Frost only so much. Rather, I admire his artistry and feel grateful for all that he gave us.

MILOSZ ON SWEDENBORG (A shameless digression)

Milosz, a public Catholic (after a period of atheism and disgust with the reactionary, anti-Semitic Polish Catholic right wing), was fascinated by all kinds of heresies, chiefly Gnosticism and the system dreamed up by Swedenborg — who is almost like Dante, traveling through heaven and hell, but without Dante’s literary genius.

Swedenborg, though regarded as an eminent geologist and naturalist, turned away from the scientific worldview and became preoccupied with his visions of the spirit world. Let me quote from Milosz’s essay, “Dostoyevski and Swedenborg” in Emperor of the Earth:

[According to Swedenbog], “man has withdraw himself from heaven by the love of self and love of the world.”

But the “world” that Swedenborg refers to is presumably not nature but civilization, and the negative aspects of civilization at that — not palaces and gardens, not art, music, and literature, but “worldly ambition,” greed, and deceit. Swedenborg had a religious orientation, and religions tend to focus exclusively on the negative aspects or the self and the world. They don’t find “the world” to be heaven the way so many solitary people do (Wordsworth, Rousseau, Thoreau), finding joy and companionship in nature.

Swedenborg and Blake humanized and hominized God and the universe to such an extent that everything, from the smallest particle of matter to planets and stars, was given but one goal: to serve as a fount of signs for human language. [Oriana: a large buck would be a very abundant fount — and indeed it becomes that for Frost. It’s just that instead of being thrilled to have received this occasion for poetry, he claims to be disappointed.]

Here is the really fascinating part:

“When [a man] dies, he finds himself in one of the innumerable heavens or hells which are nothing other than societies composed of people of the same inclination. Every heaven or hell is a precisely reproduction of the states of mind a given man experienced when on earth and it appears accordingly — as beautiful gardens, groves, or the slums of a big city. Thus everything on earth perceived by the five senses will accompany a man as a source of joy or suffering.”

This is certainly an interesting vision of the afterlife, but isn’t it essentially true of THIS life? A person in a negative state of mind is more likely to see ugliness rather than beauty, though the opposite also holds true: living in beautiful surroundings is more likely to result in a pleasant state of mind.

Finally, people also transform their surroundings. Put artists in abandoned industrial buildings, and watch a fantastic transformation. People can create their heaven and hell. It’s not completely under their control, no. Yet even during the war, a piece of heaven can be created. Here the Syrian artist Tammam Azzam painted Klimt's Kiss on a ruined buildling:

Frost’s bleak vision reflects reality as he sees it. Someone else in the same spot might experience thrill and joy.

THE SENSE OF ABSENCE

There seems to be a new argument for the existence of god, and that’s the argument from presence. According to some religious apologists, everyone senses god’s presence. Atheists only pretend not to sense it.

To me the only constant in regard to god has been his total and absolute absence. God didn’t exist for me before religion lessons, and I was quite happy and unaware that anything was missing. Then came the heavy Catholic indoctrination and the Invisible Man in the Sky acquired some degree of psychological reality.

I want to emphasize “some degree” — though, oddly enough, I seemed to have certainty as to the reality of hell. Otherwise, especially during prayer, experience constantly confronted me with the absence of that Invisible Man. I couldn’t help suspecting that I was talking to empty air. Looking up, I saw only clouds. Then, at fourteen, I stopped lying to myself under the pressure of the church, and acknowledged that my true personal experience was that of absence of anyone up there or anywhere.

The Emperor had no clothes! Or rather, it could be argued, it was all clothes and no Emperor. No Emperor, King of Kings, Creator, the Almighty. No such being has ever existed except as one of the hundreds of fictional deities made up by humans over the millennia.

Though long in making, my final epiphany took essentially a moment. After some minutes of terror when I literally waited to be struck by lightning for daring to declare that god didn’t exist, I began to breathe freely and was no longer afraid to think for myself. Fuller recovery from the Big Lie (and the intricate web of related lies, e.g. suffering is good for you) has been the journey of a lifetime.

But I don’t feel an iota poorer for not seeing a tree as a manifestation of the divine rather than a tree. Looking at a tree, I don’t generally think of it as a product of evolution, though of course it is that; rather, I respond to the tree’s beauty. I love it just for being a tree, and a deer for being a deer.

The enormous mental revolution of modernity has been precisely about loving the self and loving this world. Loving animals has been a part of this evolution.

(Loving children the way we moderns love them has been relatively recent. That is why we are so appalled that a mother nursing her baby daughter would choose to abandon the child in the most final of ways, that of dying for the promise of paradise as reward of killing the infidels. That a toxic theology could prove more powerful than the strongest of human bonds shakes us to the core.)

ELIZABETH BISHOP’S JOY AT SEEING A MOOSE

Frost’s poem is an anomaly. One of the best-known modern poems about a wild animal is Elizabeth Bishop’s The Moose. Let me quote the most memorable part of it:

—Suddenly the bus driver

stops with a jolt,

turns off his lights.

A moose has come out of

the impenetrable wood

and stands there, looms, rather,

in the middle of the road.

It approaches; it sniffs at

the bus’s hot hood.

Towering, antlerless,

high as a church,

homely as a house

(or, safe as houses).

A man’s voice assures us

“Perfectly harmless....”

Some of the passengers

exclaim in whispers,

childishly, softly,

“Sure are big creatures.”

“It’s awful plain.”

“Look! It’s a she!”

Taking her time,

she looks the bus over,

grand, otherworldly.

Why, why do we feel

(we all feel) this sweet

sensation of joy?

~ now this is the normal human response to seeing a large wild animal that does not represent a threat. Children tend to adore animals. Note that in this poems, the adult passengers become like children — as they should. An animal stands for innocence.

Also, there are no Christian, Jewish, or Muslim animals. Animals do not celebrate holidays because every day is a holiday — a feast of existence.

*

Finally, I can’t resist quoting my own poem about my most memorable encounter with a large male deer. Walking on forever is of course wishful thinking, but my sense of awe at the beauty of nature is not.

Hurricane Ridge is in Olympic National Park in the state of Washington.

HURRICANE RIDGE

The glaciers tongue me, cliffs of ice,

pools of polar green.

Across eternal snow, a deer

steps out on the trail.

His antlers hold the flame-blue sky,

his crown of shining branches.

He stares at me without fear,

then climbs straight up,

barely nudges the slippery scree.

How could I know it would be

neither a lover nor a holy sage,

but a deer in a tundra of clouds —

this messenger making me feel

one day I’ll walk forever —

when thirsty, eating snow,

when tired, leaning on the wind.

My shadow compassing late sun,

I want one wish granted to me:

to hike again along the crest

here on Hurricane Ridge,

and let a deer like that once more

step out before me on the path,

look at me calmly, and walk on.

Let the wind wave a branch.

~ Oriana © 2015

The joy at seeing a beautiful wild animal is no surprise. It’s part of the joy of being alive. Beauty is reason enough.

photo: Huib Peterson

photo: Huib Peterson