*

CROSSING SAN ANDREAS

Frazier Park, California

Cosmo, my neighbor, who believed

that rocks have consciousness,

they are just slow,

showed me at last where lay

the San Andreas Earthquake Fault:

“Right here. It’s the river.”

He meant the muddy trickle

meandering through sagebrush —

the bridge that spanned it ran

a quarter of a block. Each time

I crossed the bridge, I crossed

from the Pacific Plate

among the piñon pines

on the Pacific Plate; I crossed

both tectonic plates.

half of here will shear

toward San Francisco;

the other half will slide

down toward Baja.”

San Francisco or Baja?

I had to have both.

The soul too is a housewife

and requires both.

From parent to teacher

to artist, from I love you

to oil for the salad,

fissures, earthquake faults,

a bridge where you drop

your name like a lost coin —

knowing any instant

took place two hundred

years ago. Great oaks

snapped like saplings,

rifts opened ten feet wide.

“I built the house myself.

I put in the best

studs and bolts.”

though I felt shaken myself,

every day stepping across

from the Pacific Plate

overdue, but rocks

have a different sense of time.

Now and then one could spot

with his long-legged

instruments, his metal

measuring rod —

rocks thinking

their stone thoughts,

drunk with blossoms,

the pressure building up.

*

LIVING AND WRITING IN THE FEAR OF THE BIG ONE

I did not set out to write a book about a very-pregnant woman trying to survive an earthquake.

I did not set out to write a book at all. I was simply a very-pregnant woman with a horrible case of insomnia, lying awake at night imagining a massive earthquake. Would the roof cave in? With my stomach as distended as it was, would I even fit under the bed? Would I have to give birth alone, without running water or a doctor?

I lay in bed on my phone, reading accounts of women giving birth in Haiti after the earthquake, in war zones, during snowstorms. I tried to prepare myself by watching YouTube videos of women giving birth alone in the woods. The volume turned down low so I wouldn’t wake my husband sleeping beside me. Tears streamed down my face.

I wanted so badly to sleep, and the only way to sleep was to know more, but the more I knew, the less I could sleep.

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is seven hundred miles long and runs from northern California to British Columbia. When the two tectonic plates finally get unstuck, it will set off a massive earthquake—magnitude eight or higher. The last one was in January 1700, which means the odds of the big Cascadia earthquake happening in the next fifty years are roughly one in three.

Like so many Portlanders, I had never even heard of the earthquake until I read Kathryn Schulz’s New Yorker article, “The Very Big One,” which detailed with brutal exactness how the earthquake would devastate the region, collapsing bridges, setting off gas fires, damaging seventy-five percent of all buildings in the state. For a day or two after I read the article, I was freaked out.

But then I moved on. I was in my twenties, trying to build a career as a writer, trying to make friends, trying to figure out adult life.

For years, my earthquake anxiety lay dormant, beneath the surface of my psyche. It popped up sometimes; a friend moved into an third-story apartment in a brick building, and sometimes I would sit on her couch and imagine the building collapsing. She invited me to sleepover and I made an excuse about needing to be home for the dog.

Then I got pregnant. Suddenly, the earthquake was all I could think about.

One day, I was at IKEA shopping for some last-minute baby items and the building started to shake. My entire body went electric. This was it, this was the big one. I was wearing a maternity dress and ballet flats that could barely contain my swollen feet. I left my water bottle in the car. Nobody knew where I was. So this was how it all ended.

Except the shaking wasn’t an earthquake, it was a large truck driving by.

After the building stopped shaking, I knew immediately that I was going to write a novel about a pregnant woman walking home from IKEA after the Cascadia earthquake. And I knew immediately that I wanted every detail in the book to be accurate.

How long the shaking would last. How the IKEA in Northeast Portland would fare during a massive quake. The way heat stroke makes you dizzy, makes you sick. Which bridges will go down. How many minutes before the tsunami wipes out the coast. How much effort it takes to lift a concrete beam off a human body. The way a road looks when it’s been swallowed by liquefaction.

I walked the same route as my main character, through the golf course, through the industrial area, through the neighborhoods of Northeast Portland. I drove over and over to IKEA with my newborn child, to get lost in the warehouse labyrinth. I talked to a geologist, to a structural engineer, to a first responder who was in Kashmir days after the 2005 earthquake, trying to rescue children from collapsed schools.

Every street I mention in the book is real, most of the places I describe are real. The length and severity of the shaking, the devastation of the city, the conditions of streets and bridges, the failure of the power grid and cell towers, the outmatched official response, the danger of brick buildings, the risk of gas fires—I lost hours researching how quickly sprinklers would run out of water after the earthquake.

Sometimes I couldn’t tell if I was trying to write a novel, or just chasing a fear the way my dog chases the scent of a cat. The more I learned, the more I had to know.

Friends, writing teachers, agents, everyone kept telling me I was too worried about getting it right. “It’s a novel,” they told me. “You can just make this stuff up. Nobody is expecting this to be accurate.”

But even if I’d wanted to fictionalize the facts, how could I make up a very real disaster that is coming? Not just coming, but coming to my city, to my neighborhood, to my door? What would be worse, understating the enormity of what this earthquake will do to our city, and letting people feel soothed into apathy? Or overstating it, and terrifying people for no reason? I became obsessed with accuracy.

At one point, I had my main character walking through a hilly neighborhood. Would the entire hill slide south? I told myself it didn’t matter. That I should just write the scene without worrying about it. At this point, I had an agent and a second baby on the way. The reality is that I simply didn’t have the time to obsess.

But again and again, I sat down to write and found that I couldn’t. I thought of all the people who lived in those houses, in that neighborhood. How could I guess so casually about the destruction of real homes, of real lives? I ended up spending the better part of a week looking through old survey documents before I finally gave up and hired a graduate student to research the issue.

He wrote me this:

This has taken a good amount of thought. It’s made of sand, gravel, and boulders deposited by the Missoula glacial floods about 15,000 years ago—so it is unconsolidated, basically a pile of rocks. However—it has survived many, many major earthquakes in that time without collapsing. It appears that with the dry soil conditions we have in October (note from Emma: this is when the book is set, so we adjusted outcomes to match likely weather), there shouldn’t be too much landslide activity.

Knowing that the hill would likely be standing, I was able to write the scene.

The more I wrote about the earthquake, the less it scared me. As it turns out, the worst case scenarios that were playing out in my mind simply weren’t supported by the facts. And the facts led me not just to devastation and chaos, but also to a sense of hope and wonder that culminated in a profound optimism about humanity.

Through my research into how humans act during disasters, I came across Rebecca Solnit’s book, A Paradise Built in Hell. Solnit lays out a compelling argument that disasters cause people to experience incredible altruism, connection and even joy. That when the world falls apart around us, we actually realize how much of modern life is isolating and exhausting us, and we get the chance to experience something much more potent and meaningful.

Anxiety about the Cascadia earthquake is not a unique experience. It belongs to thousands of people who live in this region of the world, and many who don’t. I meet these people and we nod silently to each other while people joke around us about “the big one!”

I met a man who had twin babies and he told me that he and his wife made a vow to never both be on the other side of the river from their children. I imagine them sometimes, their days a coordinated dance.

I spoke to a man who cried on the phone because he was so worried about the brick school his children attended. A woman who doesn’t go the Oregon coast anymore. Another woman who told her children that they have to go to college out of state.

At first, I worried that my book, written to relieve my own anxiety, was now the harbinger of anxiety for others. But the more I talk to readers, the more I hear that there is relief in seeing their fears written in black and white, in having the space and excuse to talk about the earthquake with their communities. For me personally, what started as a self-protective obsession has turned into a deep commitment to try and help my city prepare for this disaster.

The other night, I thought I felt the house starting to shake. The earthquake, I thought. But the bookshelves are strapped to the wall. And I leave sneakers beside my bed. If the earthquake is coming tonight, I better get some rest, I thought, and I rolled over and went back to sleep. Because now I know. I know.

https://lithub.com/earthquake-anxiety-living-and-writing-in-fear-of-the-big-one/

Oriana:

“A paradise built on fault lines” is how one of my poems (Credo) describes California.

Now I believe only in California,

dressed in flames each scarlet,

smoky year. A paradise built on

fault lines. Like my life, split

at seventeen. Not even the body

remains our native country.

At least once a month I can’t help but imagine the Big One. It used to happen more often when I lived in Los Angeles, with its more frequent tremors, shocks, and aftershocks. Questions without answers would flash through my mind: the meaning, if any, of my life; have I been a good person; was I leaving behind anything worthwhile? Would the memories of others, the survivors, include me at all, and would those be memories of generosity or immigrant awkwardness? Would I feel grateful, or furious to be interrupted, now that I finally “got it”?

And all that time I knew that if the shaking started, with that rattling, pounding noise that an urban earthquake makes, I wouldn’t have the time for any such existential luxuries as those unanswerable questions. I hope I’d experience a few nanoseconds of gratitude for the best I’ve experienced, and a few more nanoseconds of love for those who made it easier for me to take risks such as living in California, for the sake of its beauty that comes with the price of knowing that in an instant you could lose it all.

We go on in our blind trust, because all we know is that we were made to go on, a part of the great journey of humanity.

*

On the 29th of March, 1958, during a walk in a park in the Argentinian town of Tandil, Witold Gombrowicz came upon a sparrow hanged from a branch, an image he used later in “Cosmos.”

“This earth on which we walk is covered with pain. We wade in pain up to the knees — and it today’s pain, the pain of yesterday, of the day before yesterday, as well as the pain from thousands of years ago — since we mustn’t delude ourselves, pain doesn’t dissolve over time, and the scream of a child from thirty centuries ago is not a bit less the scream that sounded three days ago. It’s the pain of all generations and of all existence — not only the pain of a human being. ~ Gombrowicz, Diary, 1960)

*

*

AFTER CHRISTIAN WIVES WERE TOLD TO TEXT THEIR HUSBANDS

A group of women went on a spiritual retreat to improve their relationships with their husbands.

The priest asked them:

"How many of you love your husbands?"

All the women raised their hands. They were then asked:

"And when was the last time you told your husbands that you loved them?"

Some responded today, others yesterday, others didn't even remember.

They were then asked to take out their cell phones and send the following message to their husbands:

"My love, I love you so much and appreciate everything you do for me and our beautiful family. I love you."

They were then asked to read their husbands' answers aloud.

These were the answers:

1. What bit you? Are you okay?

2. Omg, dude! Don't tell me you crashed again.

3. I don't understand, what the hell do you mean by that?

4. What did you do now? I won't forgive you this time!

5. What happened? Are you on drugs or something?

6. Don't fuck around, just tell me how much you need!

7. I'm dreaming, or this message is for the neighbor.

8. If you don't tell me who the hell this message is for, I'm going to block you.

And the best of all:

9. Who are you? I don't have this number registered, but I'd like to meet you. Send me a photo.

~ Farghan Saghir, Quora

Oriana:

I realize this may be fake, but it sounds reasonably convincing for any long-term relationship.

*

IS IT TIME TO RETHINK THE AMERICAN DREAM?

Young adults face financial struggles, with rising costs and stagnant wages making homeownership increasingly unattainable.

As a therapist and Gen Xer, I can’t help but notice how the conversation around success has shifted across generations. Many of my peers followed a familiar script—get an education, land a stable job, buy a house, start a family. It wasn’t easy, but there was a sense that if you put in the work, you’d get there.

Now, I listen to millennial and Gen Z clients talk about juggling multiple jobs, drowning in student debt, and watching home prices soar beyond reach. The American Dream we were sold feels more like a relic than a roadmap.

Maybe the real question isn’t just why it’s so hard to attain but how we process the loss of what we thought was possible. If the dream is no longer within reach, how do we grieve it—and what do we build in its place?

The Psychological Impact of a Deferred Dream

For many young adults today, the American Dream feels more like a mirage than an achievable goal. This disillusionment takes a psychological toll, particularly when individuals were raised to believe that hard work alone guarantees success. Systemic barriers and financial instability have led to an increase in mental health challenges, especially among marginalized communities.

The emotional and psychological effects of this disillusionment include:

Loss of hope: Many young adults expect to build a life similar to previous generations, only to find themselves struggling to afford rent, let alone buy a home or start a family. The gap between aspiration and reality fosters deep disillusionment, making it difficult to remain optimistic about the future.

Internalized blame and decreased self-esteem: The pressure to achieve financial independence can lead young adults to blame themselves when they fall short. Despite systemic economic disparities, many internalize their struggles as personal failures. The cultural emphasis on meritocracy reinforces these feelings of inadequacy and low self-worth.

Chronic stress and anxiety: The constant effort to overcome economic and social barriers generates high levels of stress and anxiety. Young adults today face economic precariousness—jobs with stagnant wages, soaring housing costs, and a lack of affordable healthcare. The uncertainty of financial stability, coupled with student loan burdens, creates chronic stress that affects both mental and physical health.

Social isolation and a sense of falling behind: Societal expectations around life milestones exacerbate feelings of alienation. Young adults compare themselves to peers who have achieved traditional success or to previous generations who could afford homes and start families earlier. Social media intensifies this phenomenon, reinforcing the belief that they are failing while others thrive. As a result, some withdraw from social interactions, feeling like they do not belong.

Reduced motivation and apathy: When dreams feel unattainable, motivation can dwindle. Clients often express a sense of futility—why strive for homeownership when housing prices continue to rise beyond reach? Why invest in relationships when financial instability makes marriage and children seem impossible? This apathy can lead to stagnation, where individuals stop striving toward their goals, believing them unachievable.

Intergenerational trauma and economic disparities among BIPOC communities: For BIPOC [black, indigenous, person-of-color) individuals, the effects of a deferred American Dream are even more pronounced due to systemic racism and generational economic disparities.

The racial wealth gap persists: In 2022, the median wealth of white households was nearly eight times that of black households and five times that of Hispanic households (Federal Reserve, 2023). Discriminatory policies in housing, education, and employment have historically excluded marginalized communities from opportunities to build generational wealth. The economic struggles of today’s young adults in BIPOC communities are inherited, compounding the psychological impact.

How to Mitigate the Psychological Toll — Community Support and Collective Healing

Building strong social networks and finding supportive communities can provide a sense of belonging. Mutual aid groups, financial literacy programs, and community-driven initiatives offer resources and solidarity to those facing economic hardships. Within many communities, embracing resilience and collective healing practices can help mitigate the psychological toll of systemic barriers.

Mental health support and grief-focused therapy: Grief therapy can be particularly useful in addressing the loss of the American Dream as an attainable reality. Many young adults need space to grieve the life they envisioned but cannot achieve due to systemic economic shifts. Therapy can help them process feelings of frustration and hopelessness while guiding individuals toward redefining success in meaningful and attainable ways.

Advocacy and radical acceptance: Addressing these issues requires a shift in how we understand resistance and advocacy. Radical acceptance—acknowledging the reality of systemic inequality without denying or minimizing it—becomes a form of both advocacy and change.

Instead of simply fighting against oppressive structures, radical acceptance empowers individuals to recognize and sit with the realities of their circumstances while still finding ways to create change. By embracing reality while pushing for change, individuals reclaim agency. Accepting what is allows us to fight more effectively for what could be.

Redefining the Dream: Finding Hope in a Changing World

While the traditional American Dream may no longer be realistic for many, young adults do not have to abandon all hope. Therapy can help individuals shift their expectations and redefine success on their own terms. Perhaps fulfillment comes not from homeownership but from cultivating meaningful relationships. Maybe financial stability looks different—building security through alternative career paths, cooperative living arrangements, or nontraditional family structures.

The ability to dream, even amidst economic hardship, is essential for psychological well-being. By recognizing and grieving the loss of the old dream, individuals can make room for new possibilities—ones that align with today’s evolving realities.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/communal-healing/202502/is-it-time-to-rethink-the-american-dream

Mary:

*

PROTESTERS IN GAZA WANT HAMAS OUT

“Leave us, Hamas, we want to live freely,” a crowd could be heard chanting at a demonstration in Beit Lahia in northern Gaza on Wednesday.

Protests in Gaza calling for an end to the war with Israel and for Hamas' ouster gathered momentum Wednesday, with hundreds of demonstrators for a second day displaying rare dissent against the militant group that has run the Palestinian enclave for nearly two decades.

The protests began with an initial demonstration Tuesday in Beit Lahia, where protesters chanted anti-Hamas slogans as Palestinians also railed against the resumption of Israel's military offensive in Gaza. Renewed fighting shattered a ceasefire deal after two months of relative calm.

Why now?

It was not immediately clear who organized the protests or how many joined them with the intention of rallying against Hamas.

But some demonstrators told NBC News' crew that they had reached the limit of their suffering and blamed Hamas for failing to bring an end to the war.

More than 50,000 people, including thousands of children, have been killed in Israel’s offensive in Gaza, according to the local Health Ministry in the enclave, which has been run by Hamas since 2007 after Israel ended its 38-year occupation.

"We came out to demand that Hamas stop the war and hand the ruling to any merciful body so that God may have mercy upon us," one man, Eyad Gendia, told NBC News at Wednesday's protest in the Shujaiya neighborhood of eastern Gaza City.

"The impact of the war is that we are sleeping in the streets ... We have lost all of our children," he said.

Before this week, NBC News had documented smaller anti-war protests in Gaza but this week's demonstrations represent the biggest since the conflict began after Hamas led terrorist attacks in Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, in which some 1,200 people were killed and around 250 others taken hostage, according to Israeli officials.

Israel, which continues to block the entry of aid and goods into the Gaza Strip, has said it wants to eliminate Hamas to ensure that the Oct. 7 attacks will not be repeated. The United States has supported Israel in its campaign, with President Donald Trump also sparking widespread condemnation by suggesting that America take over the enclave and turn it into the "Riviera of the Middle East."

"If the Israel problem is Hamas, we will expel Hamas to resolve this issue," said another man, who did not share his name. "We are demanding an end to the frantic war against Gaza's children, women and elderly."

"We need a permanent ceasefire," said a third demonstrator, who spoke without offering identification.

The Israeli Foreign Ministry said in a post on X on Wednesday that the anti-Hamas slogans shouted at the protests were proof that "Hamas' refusal to release the hostages" was "fueling war and the suffering of the people of Gaza."

Basem Naim, a senior political official for Hamas, told NBC News on Wednesday that "everyone has the right to scream in pain and to raise their voice against the aggression towards our people," but he said it was "unacceptable to exploit these tragic humanitarian situations for questionable political agendas or to shift blame away from the real aggressors."

Mounting pressure

Hamas' popularity in Gaza is hard to gauge, due to fears over speaking out and the difficulties of conducting polling during a war. But a poll released in September by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, a think tank based in the occupied West Bank, found support for Hamas in the Gaza Strip to be at 35%, compared to 38% three months before.

Sanam Vakil, director of the London-based think tank Chatham House’s Middle East and North Africa program, said the protests put fresh pressure on Hamas as Israel and the U.S. push the militant group to agree to an extension of the first phase of the ceasefire deal, which expired March 1, and to release more hostages.

Hamas has refused, instead demanding a return to negotiations aimed at launching the second phase of the deal, as had been planned under the framework of the truce deal. The second phase was meant to pave the way to an end to the war, although the truce disintegrated when Israeli forces resumed airstrikes on Gaza.

"The big questions for Hamas are really, how it can be a resilient political force in the climate of so much pressure?" Vakil said in a phone interview Wednesday.

Hamas has previously signaled it would be willing to cede political power and administrative governance of Gaza to a Palestinian unity government, but said it would be unwilling to disarm until internationally recognized independent Palestinian statehood is achieved.

*

*

Derek Miller: THE EXPULSION OF MAHMOUD KHALIL

As I'm neither a segregationist nor a neo-Nazi, perhaps it would be best to hear this from me. I'm a Boston native, a life-long Democrat, and I have a Ph.D. and two masters degrees and also worked at the UN for over a decade on international peace and security where I lead a research team on developing new methods and systems to generate and apply local knowledge to the design of community security programs. I'm also the author of seven critically acclaimed novels including Norwegian by Night.

Come at me from the left and I own you.

To quote from the article — and I encourage everyone to try and remember what you have actually seen and experienced since Oct.7th — "It is always dangerous to speak in public for Palestinian rights, safety, and freedom with your face uncovered and your name declared. You can be sure you will be harassed, doxed, terrorized.”

Um … really?

I would like everyone to take a moment and try and think of all the Jewish neighborhoods you are afraid to visit; the Jews who have harassed, doxed and terrorized you over the years; and the Jews who have fought against civil liberties, human rights, freedom of speech, and tolerance.

I assume you're done.

I'm fed up with this kind of nonsense. More than 30% (and in cases far more) of the "students" were not students. American Muslims for Palestine is a terrorist supporting network backed by the Muslim Brotherhood and the SJP was out in force against JEWISH students on Oct. 8th before Israel even responded with military force.

Freedom of speech is a deeply American value. What is not an American value is incitement to violence; harassment; sedition; seditious conspiracy and the list goes on. The man is publicly committed to the destruction of Western Civilization (his words) and he is providing material support to a designated terrorist organization.

(People like him are what we need to defend ourselves AGAINST in order to MAINTAIN freedom of speech.

I find it especially ironic that a professor of classics — that is, an expert in the wellspring of Western civilization itself — would be so uninterested (and prepared to publish and publicize that lack of interest) in the behavior and conduct (not speech) of the person he is defending.

No. No one who has publicly and calmly spoken up for Palestinian rights (many of them Jews!) has faced terrorism. This is Orwellian and rather shocking to read and I'm ashamed that I have to read it here. ~ Derek Miller, Facebook

*

*

MUD, WATER AND WOOD: THE SYSTEM THAT KEPT A 1604-YEAR-OLD CITY AFLOAT

Most modern structures are built to last 50 years or so, but ingenious ancient engineering has kept this watery city afloat for more than 1,600 years – using only wood.

As any local knows, Venice is an upside-down forest. The city, which turned 1604 years old on March 25, is built on the foundations of millions of short wooden piles, pounded in the ground with their tip facing downwards.

These trees – larch, oak, alder, pine, spruce and elm of a length ranging between 3.5m (11.5ft) to less than 1m (3ft) – have been holding up stone palazzos and tall bell towers for centuries, in a true marvel of engineering leveraging the forces of physics and nature.

In most modern structures, reinforced concrete and steel do the work that this inverted forest has been doing for centuries. But despite their strength, few foundations today could last as long as Venice's. "Concrete or steel piles are designed [with a guarantee to last] 50 years today," says

Alexander Puzrin, professor of geomechanics and geosystems engineering at the ETH university in Zurich, Switzerland. "Of course, they might last longer, but when we build houses and industrial structures, the standard is 50 years of life.”

*

Building to last

Only once, early on in his career, Puzrin has been asked to provide a guarantee of 500 years for a construction a Baháʼí temple in Israel.

"I was kind of shocked because this was unusual," he recalls. "I was really scared, and they wanted me to sign. I called my boss in Tel Aviv, a very experienced, old engineer and I said, 'What are we going to do? They want 500 years.' He answered, '500 years? [pause]. Sign.' None of us is going to be there.”

*

The Venetian piles technique is fascinating for its geometry, its centuries-old resilience, and for its sheer scale. No-one is exactly sure how many millions of piles there are under the city, but there are 14,000 tightly packed wooden poles in the foundations of the Rialto bridge alone, and 10,000 oak trees under the San Marco Basilica, which was built in 832AD.

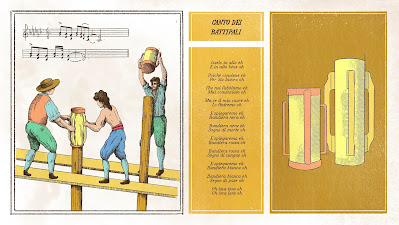

"I was born and raised in Venice," says Caterina Francesca Izzo, environmental chemistry and cultural heritage professor at the University of Venice. "Growing up, like everyone else, I knew that underneath the Venetian buildings, there are the trees of Cadore [the mountain region next to Venice]. But I didn't know how these piles were placed, how they were counted and knocked down, nor the fact that the battipali (literally the 'pile hitters') had a very important profession. They even had their own songs. It is fascinating from a technical and technological point of view."

The battipali would hammer down the piles by hand, and they would sing an ancient song to keep the rhythm – a haunting and repetitive melody with lyrics that praise Venice, its republican glory, its Catholic faith, and declare death to the enemy of the time, the Turks. On a more lighthearted note, a Venetian expression still in use today, na testa da bater pai (literally 'a head that is good to pound down the piles') is a colorful way of saying that someone is dull or slow-witted.

The people who drove the piles into the silt were known as battipali, or pile hitters, and used a song to help them keep the rhythm as they worked

The piles were stuck as deep as possible, until they couldn't be pounded down any further, starting at the outer edge of the structure and moving towards the center of the foundations, usually driving nine piles per square metre in a spiral shape. The heads were then sawn to obtain a regular surface, which would lay below sea-level.

Transverse wooden structures – either zatteroni (boards) or madieri (beams) – were placed on top. In the case of the bell towers, these beams or boards were up to 50cm (20in) thick. For other buildings, the dimensions were 20cm (8in) or even less. Oak provided the most resilient wood, but it was also the most precious. (Later on, oak would only be used to build ships – it was too valuable to stick in the mud.) On top of this wooden foundation, workers would place the stone of the building.

The Republic of Venice soon began protecting its forests to provide sufficient wood for construction, as well as for ships. "Venice invented sylviculture," explains Nicola Macchioni, research director at the institute for bioeconomy at Italy's National Council for Research, referring to the practice of cultivating trees. "The first official sylviculture document in Italy is indeed from the Magnificent Community of the Fiemme Valley [to the north-west of Venice], dating from 1111AD. It details rules to exploit the woods without depleting them."

According to Macchioni, these conservation practices must have been in use years before they were written down. "That explains why the Fiemme Valley is still covered by a lush fir forest today." Countries such as England, however, were facing wood shortages by the middle of the 16th Century already, he adds.

The wooden piles beneath Venice are slowly degrading as anaerobic bacteria attack the cell walls of the wood fibers

Venice is not the only city relying on wooden piles for foundations – but there are key differences that make it unique. Amsterdam is another city partially built on wooden piles – here and in many other northern European cities, they go all the way down until they reach the bedrock, and they work like long columns, or like the legs of a table.

"Which is fine if the rock is close to the surface," says Thomas Leslie, professor of architecture at the University of Illinois. But in many regions, the bedrock is well beyond the reach of a pile. On the shore of Lake Michigan in the US, where Leslie is based, the bedrock could be 100ft (30m) below the surface. "Finding trees that big is difficult, right? There were stories of Chicago in the 1880s where they tried to drive one tree trunk on top of another, which, as you can imagine ended up not working. Finally, they realized that you could rely on the friction of the soil."

The principle is based on the idea of reinforcing the soil, by sticking in as many piles as possible, raising substantial friction between piles and soil. "What's clever about that," says Leslie, "is that you're sort of using the physics… The beauty of it is that you're using the fluid nature of the soil to provide resistance to hold the buildings up." The technical term for this is hydrostatic pressure, which essentially means that the soil "grips" the piles if many are inserted densely in one spot, Leslie says.

Indeed, the Venetian piles work this way – they are too short to reach bedrock, and instead keep the buildings up thanks to friction. But the history of this way of building goes back further still.

The technique was mentioned by 1st-Century Roman engineer and architect Vitruvius; Romans would use submerged piles to build bridges, which again are close to water. Water gates in China were built with friction piles too. The Aztecs used them in Mexico City, until the Spanish came, tore down the ancient city and built their Catholic cathedral on top, Puzrin notes. "The Aztecs knew how to build in their environment much better than the Spanish later, who have now huge problems with this metropolitan cathedral [where the floor is sinking unevenly]."

Puzrin holds a graduate class at ETH that investigates famous geotechnical failures. "And this is one of these failures. This Mexico City cathedral, and Mexico City in general, is an open-air museum of everything that can go wrong with your foundations.”

The wood, soil and water all combine to provide Venice's foundations with remarkable strength.

After more than a millennium and a half in the water, Venice's foundations have proved remarkably resilient. They are not, however, immune to damage.

Ten years ago, a team from the universities of Padova and Venice (departments ranging from forestry to engineering and cultural heritage) investigated the condition of the city's foundations, starting from the belltower of the Frari Church, built in 1440 on alder piles.

The Frari belltower has been sinking 1mm (0.04in) a year since its construction, for a total of 60cm (about 24in). Compared with churches and buildings, belltowers have more weight distributed on a smaller surface and therefore sink deeper and faster, "like a stiletto heel", says Macchioni, who was part of the team investigating the city’s foundations.

Caterina Francesca Izzo was working on the field, core drilling, collecting and analyzing wood samples from underneath churches, belltowers and from the side of the canals, which were being emptied out and cleaned up at the time. She said that they had to be careful while they were working on the bottom of the dry canal, to avoid the wastewater sporadically gushing from the side pipes.

The team found that throughout the structures they investigated, the wood was damaged (bad news), but the system of water, mud and wood was keeping it all together (good news).

They debunked the common belief that the wood underneath the city doesn't rot because it's in an oxygen-free, or anaerobic, condition – bacteria do attack wood, even in absence of oxygen. But bacteria action is much slower than the action of fungi and insects, which operate in the presence of oxygen.

Furthermore, water fills up the cells that are emptied out by bacteria, allowing wooden piles to maintain their shape. So even if the wooden piles are damaged, the whole system of wood, water and mud is held together under intense pressure, and is kept resilient for centuries.

"Is there anything to worry about? Yes and no, but we should still consider continuing this type of research," says Izzo. Since the sampling 10 years ago, they hadn't collected new ones, mainly because of the logistics involved.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20250324-the-ancient-forest-that-supports-venice

*

THE WEIRD WAY THE LOS ANGELES BASIN ALTERS EARTHQUAKES

Los Angeles sits above an enormous bowl of sediment that alters how seismic waves move under the city

Southern California is frequently shaken by earthquakes. How they feel to people living in Los Angeles has a lot to do with the sediment-filled basin the city sits upon.

Hollywood stars were just starting to arrive at their afterparties following the Oscars when the ground suddenly jolted. There were a few screams and high-rise buildings reportedly wobbled.

The magnitude 3.9 earthquake that hit North Hollywood on 2 March 2025 was the latest in a number of jolts to have hit the area. The earthquake was measured to have occurred at a depth of around 9 miles (15km), but was felt in parts of the city several miles away. Another much smaller magnitude 1.3 earthquake was detected almost in the same location a few hours later. No damage to buildings was reported.

It wasn't a terribly unusual event, by California's standards. The state is the second-most seismically active in the United States behind Alaska, with Southern California experiencing an earthquake on average every three minutes. In the week leading up to the post-Oscars quake, 36 earthquakes occurred in the LA area, with most being under magnitude 2.0. While most are too small to be felt, around 15-20 events exceed magnitude 4.0 each year.

The most recent occured a little over an hour after sunset on 6 August 2024, when a sparsely populated belt of farmland near Bakersfield, Southern California, was shaken from a restful evening. A magnitude 5.2 earthquake, followed by hundreds of smaller aftershocks, shuddered through the area as a fault near the southern end of the Central Valley ruptured – the largest earthquake to hit Southern California in three years. The epicenter was about 17 miles (27km) south of Bakersfield and people reported shaking nearly 90 miles (145km) away in portions of Los Angeles and as far away as San Diego. Then, a few days later, another jolt rattled the Los Angeles area due to a rupture on a small section of the dangerous Puente Hills fault system. The resulting magnitude 4.4 earthquake had its epicenter just four miles northeast of the city's downtown area.

Although there was minimal damage caused by both quakes in August 2024 and the less severe shake in Hollywood in March 2025, they highlighted just how the geology under California's largest city can alter the effects of fault movements in the area. The relatively shallow depth of the 6 August earthquake appeared to create more intense or prolonged shaking in some parts of the city, while others felt almost nothing at all.

There are various reasons for why this might be – including what people were doing at the time of the earthquake – but the enormous five-mile-deep (8km), sediment-filled basin that LA is built upon plays a surprising role in the effects felt above ground.

The traveling earthquake

While the ground feels steadfast at the surface, deeply buried bedrock can resemble a shattered window pane. These cracks, or faults, are where earthquakes occur. Faults are put under tremendous stress by the slow and steady movement of the Earth's tectonic plates.

In California, the North American plate and the Pacific Plate are grinding past each other along the infamous San Andreas fault, averaging about 30-50 millimeters (1-2 inches) every year. The movement is anything but fluid. Cracked rocks are rough and wedge against each other, sometimes staying stuck for thousands of years. Over time, stress created by the slow marching tectonic plates builds up and when the fault reaches its stress limit, it "slips" and ruptures, causing an earthquake.

A rupture begins at one location and travels in one direction along the fault, stretching up to hundreds of kilometers. The longest rupture ever recorded was a 994 mile (1,600km) portion of a fault that caused the Great Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and resulting tsunami on Boxing Day 2004. "The farther it goes, the longer [the earthquake] lasts, and the more energy that's released. So the longer the fault, the bigger the earthquake," explains seismologist Lucy Jones, a researcher at the California Institute of Technology and former seismologist with the US Geological Survey.

During an earthquake, the stored energy saved within the sticky fault is released suddenly. Seismic waves radiate out from the rupture like the ripples created by throwing a rock into a pond, spreading in all directions through the surrounding rock and earth.

The magnitude of an earthquake tells scientists about the length of the ruptured fault as well as the duration of shaking, says Jones. But the intensity of an earthquake – the ground motions we feel at a location – is shaped by how close we are to the epicenter, which direction the fault ruptured, and the geological layers under our feet.

Geology-induced complications

Los Angeles is located south of a giant a bend in the San Andreas fault where the plate boundary clearly changes direction. "If you see it from the air, it's amazing," says Jones. "It's so bizarre – you can look down and see the fault valley and then it just turns."

Around the turn, the region is chock full of faults. Over millions of years, the faults churned and pushed slabs of bedrock into multiple mountain ranges and deep basins. Gravity, water and wind act like sandpaper, wearing down the mountains, and carrying debris into the basins. Over time, the basins have been filled with sediment.

The bowl-shaped basin of rock under Los Angeles is up to five miles (8km) deep, filled with a mixture of gravel, sand and clay. The contrast between the hard rock and softer sediment are big factors that cause some seismic weirdness for cities like Los Angeles.

During an earthquake, seismic waves are modulated by geology, says John Vidale, professor of seismology at University of Southern California. "The primary factor is just how hard is the ground and how deep is the structure that has soft [material] near the surface," he says. Seismic waves will move faster in denser material like rock, versus softer and less dense sediment.

As seismic waves travel through the basin, their behavior changes when they encounter the loose sediment. "[The wave] is now having to travel at a much slower speed, but it still has to carry the same amount of energy per unit time," said Jones. As the wave slogs through the sediment, the amplitude, or wave height, gets bigger.

Put another way, imagine the Los Angeles basin as a giant bowl of jelly – the dense rocky mountains and underlying rock make up the bowl, while the sediment fill is represented by the gelatinous mixture. "If you shake the bottom [of the bowl] a little bit, the top flops back and forth quite a bit," says Vidale. And atop this quivering mass of jelly is the megacity of Los Angeles.

The San Andreas fault between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates is clearly visible from the air in places

This means the amplitude of the waves within a basin can be significantly bigger than those moving through rock. In one study, researchers using earthquake measurements in the Los Angeles region from the 1992 Landers earthquake found that seismic waves inside the Los Angeles basin were three to four times larger than sites outside the basin.

As if that wasn't enough for Los Angeles, the close proximity of the San Bernadino and San Gabriel Basins to the Los Angeles Basins can create a funneling effect, directing seismic waves towards Los Angeles.

Even within a basin, there can be differences in how the sediment interacts with seismic waves. "There's variability in the shaking… there's variations in the geology," says Vidale. Sediment in the upper 330ft (100m) of the basin tends to be looser and less dense than the deeper, compacted sediment below. Sediment changes can also happen quickly at the surface. "Old stream channels, for example, can be filled with a kind of wet, soft material," Vidale says. "So, if you happen to be in an old stream channel, you'll get hit a lot harder than somebody even a quarter mile away that's on firmer ground."

Even those in the same house can have different experiences, especially if the earthquake is on the smaller side. "I'm in Pasadena, on the sediment in the San Gabriel Valley," say Jones. Despite both being in the house, she and her husband had different experiences of the earthquake on 6 August 2024. "I felt it, my husband didn't," she says.

BASINS, BASINS EVERYWHERE

While the city of Los Angeles ticks a lot of seismic hazard boxes, it is not the only urban center that needs to worry. Throughout human history, people have tended to build cities on flat ground near water bodies.

It just so happens that these sites tend to form above geologic basins and sometimes near faults.

While the US has a few famous cities built on basins – Seattle, Portland, and Salt Lake City – there are many others around the world that experience amplified seismic waves due to where they are situated. After the European settlers drained Lake Texcoco in the 1500s, Mexico City was built on the flat, old lake bottom. In 1985 and 2017, the city experienced significant damage from earthquakes that shook the basin sediments.

The desert megacity of Tehran in Iran also sits atop a geologic basin filled with river sediments, and there is growing concern about the risk of a major earthquake in the area.

Understanding the earthquake risk is the first step in bolstering protection for a city against significant shaking. Enacting robust building codes can be another way to protect people and infrastructure, but it often takes a major event for stricter regulations to be implemented. After the devastating earthquake in 1985, for example, Mexico City enacted stringent building codes, and retrofitted older buildings.

"The very first earthquake codes [in California] went in after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake," adds Jones. At that time, schools were built out of firesafe, unreinforced brick. "Seventy schools were completely destroyed – luckily, it was at six o'clock at night," says Jones. The horror of collapsing schools spurred regulation, but initial codes were meager. "They basically just said, 'don't build unreinforced masonry in California. That was sort of the first basic code.

Today, assessing earthquake risks is a lot more nuanced.

In the US, a team of seismologists, geoscientists and geophysicists have created a seismic hazard map, showing the chances of a damaging earthquake shaking in the next 100 years. In their latest version of the report, the team found that that nearly 75% of the US could experience damaging shaking. To help policymakers and engineers, the team included information on the implications for building and structural designs.

While building codes can protect lives, scientists like Jones want building codes to go further. Designing buildings so they can be more easily repaired rather than needing to be demolished would cost an extra 1% in the construction phase, Jones estimates. "We're calling it 'functional recovery'," she says.

"We are trying to say that 'just not killing you' is an insufficient standard. The reality is, if your building's badly damaged and now has to be torn down after the earthquake, you've hurt your tenants, you've hurt your neighbors, you've hurt the local economy."

Fortunately, the buildings of Los Angeles rode out the latest quakes to rattle Southern California pretty well. But at some point, the city won't be so lucky.

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240816-california-earthquakes-why-the-los-angeles-basin-is-like-a-bowl-of-jelly

*

VAN GOGH’S “GUARDIAN ANGEL”

At the toughest, most turbulent time of his life, the Post-Impressionist painter was supported by an unlikely soulmate, Joseph Roulin, a postman in Arles. A new exhibition explores this close friendship, and how it benefited art history.

On 23 December, 1888, the day that Vincent van Gogh mutilated his ear and presented the severed portion to a sex worker, he was tended to by an unlikely soulmate: the postman Joseph Roulin.

A rare figure of stability during Van Gogh's mentally turbulent two years in Arles, in the South of France, Roulin ensured that he received care in a psychiatric hospital, and visited him while he was there, writing to the artist's brother Theo to update him on his condition.

He paid Van Gogh's rent while he was being cared for, and spent the entire day with him when he was discharged two weeks later. "Roulin… has a silent gravity and a tenderness for me as an old soldier might have for a young one," Van Gogh wrote to Theo the following April, describing Roulin as "such a good soul and so wise and so full of feeling”.

Paying homage to this touching relationship is the exhibition Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits, opening at the MFA Boston, USA, on 30 March, before moving on to its co-organizer, the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, in October. This is the first exhibition devoted to portraits of all five members of the Roulin family. It features more than 20 paintings by Van Gogh, alongside works by important influences on the Dutch artist, including 17th-Century Dutch masters Rembrandt and Frans Hals, and the French artist Paul Gauguin, who lived for two months with Van Gogh in Arles.

"So much of what I was hoping for with this exhibition is a human story," co-curator Katie Hanson (MFA Boston) tells the BBC. "The exhibition really highlights that Roulin isn't just a model for him – this was someone with whom he developed a very deep bond of friendship." Van Gogh's tumultuous relationship with Gauguin, and the fallout between them that most likely precipitated the ear incident, has tended to overshadow his narrative, but Roulin offered something more constant and uncomplicated. We see this in the portraits – the open honesty with which he returns Van Gogh's stare, and the mutual respect and affection that radiate from the canvas.

A new life in Arles

Van Gogh moved from Paris to Arles in February 1888, believing the brighter light and intense colors would better his art, and that southerners were "more artistic" in appearance, and ideal subjects to paint. Hanson emphasizes Van Gogh's "openness to possibility" at this time, and his feeling, still relatable today, of being a new face in town. "We don't have to hit on our life's work on our first try; we might also be seeking and searching for our next direction, our next place," she says. And it's in this spirit that Van Gogh, a newcomer with "a big heart", welcomed new connections.

Before moving into the yellow house next door, now known so well inside and out, Van Gogh rented a room above the Café de la Gare. The bar was frequented by Joseph Roulin, who lived on the same street and worked at the nearby railway station supervising the loading and unloading of post. Feeling that his strength lay in portrait painting, but struggling to find people to pose for him, Van Gogh was delighted when the characterful postman, who drank a sizeable portion of his earnings at the café, agreed to pose for him, asking only to be paid in food and drink.

Between August 1888 and April 1889, Van Gogh made six portraits of Roulin, symbols of companionship and hope that contrast with the motifs of loneliness, despair and impending doom seen in some of his other works. In each, Roulin is dressed in his blue postal worker's uniform, embellished with gold buttons and braid, the word "postes" proudly displayed on his cap. Roulin's stubby nose and ruddy complexion, flushed with years of drinking, made him a fascinating muse for the painter, who described him as "a more interesting man than many people.”

Roulin was just 12 years older than Van Gogh, but he became a guiding light and father figure to the lonely painter – on account of Roulin's generous beard and apparent wisdom, Van Gogh nicknamed him Socrates. Born into a wealthy family, Van Gogh belonged to a very different social class from Roulin, but was taken with his "strong peasant nature" and forbearance when times were hard. Roulin was a proud and garrulous republican, and when Van Gogh saw him singing La Marseillaise, he noticed how painterly he was, "like something out of Delacroix, out of Daumier". He saw in him the spirit of the working man, describing his voice as possessing "a distant echo of the clarion of revolutionary France.”

The friendship soon opened the door to four further sitters: Roulin's wife, Augustine, and their three children. We meet their 17-year-old son Armand, an apprentice blacksmith wearing the traces of his first facial hair, and appearing uneasy with the painter's attention; his younger brother, 11-year-old schoolboy Camille, described in the exhibition catalogue as "squirming in his chair"; and Marcelle, the couple's chubby-cheeked baby, who, Roulin writes, "makes the whole house happy." Each painting represents a different stage of life, and each sitter was gifted their portrait. In total, Van Gogh created 26 portraits of the Roulins, a significant output for one family, rarely seen in art history.

Roulin's wife is portrayed in Lullaby: Madame Augustine Rocking a Cradle (La Berceuse) 1889

Van Gogh had once hoped to be a father and husband himself, and his relationship with the Roulin family let him experience some of that joy. In a letter to Theo, he described Roulin playing with baby Marcelle: "It was touching to see him with his children on the last day, above all with the very little one when he made her laugh and bounce on his knees and sang for her." Outside these walls, Van Gogh often experienced hostility from the locals, who described him as "the redheaded madman", and even petitioned for his confinement. By contrast, the Roulins accepted his mental illness, and their home offered a place of safety and understanding.

The relationship, however, was far from one-sided. This educated visitor with his unusual Dutch accent was unlike anyone Roulin had ever met, and offered "a different kind of interaction", explains Hanson. "He's new in town, new to Roulin's stories and he's going to have new stories to tell." Roulin enjoys offering advice – on furnishing the yellow house for example – and when, in the summer of 1888, Madame Roulin returned to her home town to deliver Marcelle, Roulin, left alone, found Van Gogh welcome company.

Roulin also got the rare opportunity to have portraits painted for free, and when, the following year, he was away for work in Marseille, it comforted him that baby Marcelle could still see his portrait hanging above her cradle. His fondness for Van Gogh shines through their correspondence. "Continue to take good care of yourself, follow the advice of your good Doctor and you will see your complete recovery to the satisfaction of your relatives and your friends," he wrote to him from Marseille, signing off: "Marcelle sends you a big kiss.”

Van Gogh's portraits placed him in the heart of the family home. In his five versions of La Berceuse, meaning both "lullaby" and "the woman who rocks the cradle", Mme Roulin held a string device, fashioned by Van Gogh, that rocked the baby's cradle beyond the canvas, permitting the pair the peace to complete the artwork. The joyful background colors – green, blue, yellow or red – vary from one family member to another. Exuberant floral backdrops, reserved for the parents, come later, conveying happiness and affection – a blooming that took place since the earlier, plainer portraits.

Art history has also greatly benefited from the freedom this relationship granted Van Gogh to experiment with portraiture, and to develop his own style with its delineated shapes, bold, glowing colors, and thick wavy strokes that make the forms vibrate with life. In the security of this friendship, he overturned the conventions of portrait painting, prioritizing an emotional response to his subject, resolving "not to render what I have before my eyes" but to "express myself forcefully", and to paint Roulin, he told Theo, "as I feel him.”

A photograph of Joseph Roulin in 1902, 12 years after the death of his friend Vincent

Had Van Gogh not felt Roulin's unwavering support, he may not have survived the series of devastating breakdowns that began in December 1888 when he took a razor to his ear. With the care of those close to him, he lived a further 19 months, producing a staggering 70 paintings in his last 70 days, and leaving one of art history's most treasured legacies.

Like the intimate portraits he created in Arles, the exhibition courses with optimism. "I hope being with these works of art and exploring his creative process – and his ways of creating connection – will be a heartwarming story," Hanson says. Far from "shying away from the sadness" of this period of Van Gogh's life, she says, the exhibition bears witness to the power of supportive relationships and "the reality that sadness and hope can coexist."

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20250317-the-surprising-story-of-van-goghs-guardian-angel

Mary:

*

WHY ARENT’S HUMANS TRYING TO DRILL TO THE CENTER OF THE EARTH?

The Soviet Union tried to in the 1970s. It was called the Kola Superdeep Borehole, and it is was 40,230ft underground. To put things into perspective for you, commercial aircrafts fly at about 33–39,000ft. The USSR had kept digging for 20 years, before ultimately calling it quits.

The reason for calling it quits? They did not have the technology or equipment to withstand the heat, and pressure. For every kilometer you dig under the earth, the temperature raises about 77 degrees. They only successfully managed to penetrate .2% of the way down to the center of the earth.

With that said, it would be extremely hard to get to the center of the earth. The outer core alone, is about 8,500 degrees of liquid iron and nickel. The Asthenosphere, far above this point, is so pressurized that it holds together melting rocks.

Digging to the center of the earth sounds easy, but I can assure you, it’s not.

~ Joshua 221, Quora

*

SHOULD WE LEARN TO TOLERATE DISEASE?

Creatures that more robustly tolerate infections remain healthy even when their bodies contain levels of pathogens that would sicken or kill others of their kind. Researchers want to understand the nature of such protective mechanisms.

Not all creatures infected by a pathogen succumb to disease — in fact, a well-known scientific yardstick is the dose at which half of a study’s animals die after exposure to a pathogen or toxin. What is the difference between those that survive and those that don’t?

When people think about infectious diseases — as many have, these last three years — they think mainly about the immune system. The severity of an individual’s illness, it’s assumed, is down to how well the immune system detects, attacks and eliminates the pathogenic invader.

The immune system is said to resist disease. Resistance reduces the amount of pathogen residing inside a host, thereby curtailing disease progression, driving recovery or preventing infections altogether. People who are immunocompromised fear infections because they cannot effectively resist pathogens.

And vaccines work because they teach immune systems to recognize — and so more effectively resist — pathogens before the actual bug is encountered.

But there have always been nagging issues with so straightforwardly relating illness to the abundance of pathogen in a host. And when Janelle Ayres, a physiologist now working at the Salk Institute in San Diego, entered grad school 20 years ago, these anomalies bothered her. “I was very interested in the conventional thought or assumption that all that’s necessary to survive an infection is that you have to kill the pathogen,” she says. “I was interested in this because there are clearly examples in humans and animal models where this is just too simplistic.”

Most obviously, there are asymptomatic infections. Long before we knew that certain individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 develop no symptoms, there was the famous case of New York cook Mary Mallon. Christened “Typhoid Mary,” Mallon unknowingly lived with a Salmonella Typhi infection in the early 1900s and, in good health, transmitted the bacteria to dozens of people, some of whom died.

Conversely, there are overreactions to an infection — for example in sepsis, where the immune response is dramatically disproportionate to the infection and the whole-body inflammation that’s set off gravely damages host tissues. Often, the causative pathogen has been virtually eliminated but the overactive and maladaptive immune response to it continues to wreak potentially deadly havoc.

In David Schneider, Ayres found a PhD supervisor who was an expert in infectious disease but keen to move beyond just studying immunology. He wanted to consider the ways that animals interact with microbes growing in and on them, be these harmless, beneficial or disease-causing. Together, the pair helped to kick-start interest in a defense mechanism that, today, they think is central to health and resilience: the ability not to resist an infection but to tolerate one.

Schneider, of Stanford University, had already helped to establish fruit flies and their incredibly well-characterized genetics as a model for studying infectious diseases. But he had started to think that people using this system had become too focused on using it solely to identify new genes involved in the immune response. “I tried to ask a more general question,” he says, “where I said, ‘What does it take for the fly to survive when you give it an infection?’”

Mary Mallon was a cook in the early 1900s and an asymptomatic carrier of Salmonella Typhi, the bacterium that causes typhoid fever. Pictured here in a hospital ward, she lived decades in quarantine after she refused to give up working as a cook.

To tackle this question, for her PhD Ayres took more than 1,200 fly strains — each with a different genetic mutation — and infected them with the pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Then she recorded how long the flies took to die. Eighteen strains died more quickly than average; Ayres then measured how many bacteria had grown in each of the more susceptible strains.

In 12 of them, she found that bacterial levels were higher than normal — indicating that in these flies, the mutations had compromised their immune systems and allowed the bacteria to multiply out of control. In the remaining six strains, however, Listeria levels were normal.

These mutant flies were opposites of Typhoid Mary. Whereas her body had been able to handle an infection without any signs of sickness, these were being killed by levels of pathogen that should not have been fatal. Their immune responses were normal, but they appeared to lack some sort of resilience trait that ordinarily allowed flies to survive this infection.

It was an experiment that set the direction of Ayres’s career — for, she says, “it suggested that there are genes that an animal host has evolved that are important for tolerating an infection.”

“It’s easy to describe what a diseased individual is,” says researcher Janelle Ayres of the Salk Institute. “But how can you have an individual that … has a pathogen, but they’re healthy? How do you describe that mechanistically? What’s going on?”

The nature of these systems, how they work and how they’re controlled are questions that have occupied Ayres, Schneider and a small but growing number of researchers ever since. “It’s easy to describe what a diseased individual is. We know the mechanisms that lead to disease,” says Ayres. “But how can you have an individual that … has a pathogen, but they’re healthy? How do you describe that mechanistically? What’s going on?”

Today, there is a substantial body of research showing various ways in which animals can tolerate, and so survive, maladies such as malaria, sepsis and dysentery. And while there is a feeling among the scientists working in this field that their findings have not yet influenced work on infectious disease as much as they’d like, they are optimistic that their research could help to forge important new medical therapies. “Hopefully we’re finding core mechanisms that protect us against infectious diseases,” says Miguel Soares, an immunologist at the Gulbenkian Science Institute in Portugal, who coauthored an article about disease tolerance in the 2019 Annual Review of Immunology.

In fact, Soares hopes that basic research has already identified one such way. A drug that allows mice to survive sepsis by engaging the animals’ intrinsic resilience mechanisms is now in the first human clinical trial born directly of disease tolerance research.

Replanting an old idea

Schneider and Ayres did not invent the concept of disease tolerance. In fact, it was already more than a century old. As a grad student, Ayres read the work of a peripatetic American scientist named Nathaniel Augustus Cobb. In the late 19th century, working for the newly founded Department of Agriculture in New South Wales, Australia, Cobb had attempted to boost the productivity of local farms. In doing so, he described certain strains of wheat that developed robust fungal infections yet kept on growing and cropping — the pathogen was there but it was barely diminishing these plants’ vitality.

Through the 20th century, plant scientists embraced and dissected this defense mechanism, but the idea never caught on with scientists studying animals. Animals, after all, have immune systems — and that’s what animal and clinical research focused on.

Then, just as Schneider and Ayres were exploring this concept in fruit flies, a group at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland published on similar work in mammals. The study examined what happened when several strains of mice were infected with the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium. Some mouse strains had tolerated high levels of the parasite before becoming sick, while in others, low levels had caused illness. The authors concluded that in mice, pathogen levels alone could not explain disease severity — meaning mammals, too, vary according to how well they tolerate a pathogen, and this variability is genetically controlled.

These twin demonstrations that disease tolerance applies to animals as well as plants was a “very simple kind of conclusion, but very deep,” Soares says. “That’s when we all woke up!”

For one thing, the work suddenly offered a new framework in which to reinterpret sometimes puzzling old data.

Soares mainly studies malaria and sepsis — diseases that, respectively, kill around 600,000 and 11 million people annually. He had previously found that when mice were infected with the parasite that causes malaria, the activity of a gene critical for metabolizing iron increased. This allowed the mice to better handle the heightened levels of free iron in their bloodstreams brought about by the infection, thereby improving survival rates.

Suddenly, this seemed like an example of tolerance. And this sort of detailed mechanistic understanding was exactly what was needed to move from an idea (animals have non-immune-cell-mediated defenses against damage wrought by pathogens that have colonized their bodies) to a mature field of biology (this is how animals tolerate pathogens).

Soares stresses that advocates of disease tolerance are not downplaying the centrality of immunity. Rather, they propose that these two protective systems work together. He is also clear in his belief that vaccination and antimicrobial drugs remain the most powerful ways to combat infectious diseases. “But in some cases,” Soares says, “that’s not enough.”

What he wants are additional ways of restricting the illness that an infection causes.

Ayres, Soares, Schneider and others have now looked at multiple pathogens and interrogated how animal bodies respond to them. They have found various means by which health is maintained — or is not. These mechanisms are often complex, but that shouldn’t be a surprise, they say: The direct damage caused by pathogens induces an array of physiological reactions that, in turn, have numerous knock-on effects. And all of these can matter. Frequently, the biology of the whole animal is involved, not just the organ systems that the invader attacks. Progress is being made in mapping these multifaceted pathways.

When pathogens infect the body, they activate the immune system, which responds with resistance measures to fight the pathogen. The pathogen can sicken the animal — but so, too, can the immune system, by inducing inflammation, for example. In disease tolerance, the individual animal and/or species can respond with physiological reactions and adaptations that tamp down the negative consequences of these events, so the creature remains healthy — or at least healthier — in the presence of high counts of pathogens. Clearing the pathogen from the body still remains important, but the animal will suffer fewer ill effects while that process is underway.

Sweet success

Initially, Soares’s group focused extensively on iron in their studies of both malaria and sepsis. Each disease can cause the breakdown of iron-containing red blood cells, which releases iron-containing heme proteins that need to be dealt with in order for the body to survive. But there is a catch. Neutralizing the proteins liberates free iron, which is toxic to the host and is also a mineral that bacteria and other parasites need to survive. So dealing with these iron-containing proteins involves a fine balance between tolerating and succumbing to disease.

In a 2017 paper, Soares and colleagues found two treatments that allowed mice to better survive sepsis. The first was to treat them with a protein that safely mops up iron. The second was to give them glucose.

“Bacteria, they like glucose,” says Soares. Therefore, the body often shuts down glucose production when it is infected, and infections often make animals lose their appetites. These twin actions limit the pathogen’s energy source and so help survival of the host.

In their sepsis model, Soares’s lab found that the changes to iron metabolism had caused glucose production by the liver to decrease — but that this could go too far. “We found that you can drop the glucose, but you cannot drop it below a certain threshold level. Below that threshold level, you develop hypoglycemia and you die,” says Soares. When Sebastian Weis, a postdoc working in his lab, gave dying mice sugar, the animals rallied and lived.

Such an intervention does not help a host eliminate the disease-causing bacteria; rather, it allows it to carry on functioning until that pathogen is gone. It is, in other words, fostering disease tolerance.

Work elsewhere has reported that maintaining blood glucose in a functional range is also key to tolerating other infections; the precise responses are likely to be specific to the pathogen in question, Soares says. Ayres, meanwhile, has demonstrated just how rich and dynamic the relationship between host and a parasite can be — and how glucose levels can be key to this interaction.

To begin studying a new disease, Ayres employs a clever experimental system that entails giving a group of genetically identical mice a dose of pathogen that she knows will kill half of them. She then compares the reactions of survivors and non-survivors to ask what made the critical difference between life and death.

When she decided to use this approach to investigate a strain of Citrobacter — a mouse pathogen that shares virulence factors with E. coli strains that can cause disease in people — “I thought for sure all of the animals would get sick, and then some would recover,” she says.

But that’s not what happened. The mice that lived never got ill. Whatever was saving them kept them healthy all along.

As always with an experiment of this type, Ayres’s team checked whether the surviving mice had simply mounted a quicker, more effective immune response. But they found the amount of Citrobacter in the animals that had died and the ones that had survived were the same. Their immune responses were equivalent.

Turning to the animals’ metabolisms, Ayres’s team saw that surviving animals had changed the way they metabolized iron, and that this, in turn, had made them produce more free glucose in their circulation.

To explore the consequences of this, Ayres asked what effect the raised sugar levels had on the Citrobacter. “It’s really important when you’re studying host-pathogen interactions — or any system where you have two entities interacting — to consider both,” she says. It turned out that when these particular bacteria had their energy demands met by the host, they turned off their disease-causing virulence mechanisms. The bacteria had ceased to be pathogenic invaders and become, instead, essentially harmless microbes coexisting with their healthy host.

But while this suggested a way to protect individuals infected with Citrobacter, the result raised a troubling possibility. What if the surviving mice became walking reservoirs of lethal bacteria, basically little murine Typhoid Marys capable of spreading disease?

Instead, Ayres found something quite different. Citrobacter in tolerant mice quickly became less virulent. And when the bacteria from tolerant mice were transferred to uninfected mice, they didn’t cause illness. In other words, it looked as though well-fed bacteria happily multiplying in their hosts had quickly adapted to live that way, chronically dialing down their virulence. Ayres terms the way that changes in sugar and iron regulate Citrobacter a form of “metabolic bribery.”

“I thought it was terrific — this concept,” says Elina Zuniga, an immunologist at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the work. Zuniga says it highlights how, when the immune system suppresses pathogens, it puts the microbe in a corner, pressuring it to evolve more virulence. In tolerating an infection, Zuniga says, “we’re avoiding this endless arms race between the pathogen and the host.”

From a scientific perspective, these studies give important insights into disease biology and how the trajectory of an infection is shaped. But in terms of their clinical usefulness, Soares’s colleague Weis — who now splits his time between basic research and working as an infectious disease specialist at Jena University Hospital in Germany — is blunt. “The glucose story is boring for clinicians,” he says, and in many ways, managing hypo- and hyperglycemia is already clinical common sense.

What clinicians want, Weis says, are new drugs — and he is leading the first clinical trial that might introduce one, for sepsis.

Switching on defenses

Weis’s own research with Soares suggested that people with sepsis might be helped, as mice were, by proteins that mop up free iron. But since he knew of no such protein available for clinical testing, he took an alternative approach.

He focused instead on what he calls the tissue damage-control response — another mechanism that he believes is elemental to disease tolerance.

Soares’s lab has found that a gene called Nrf2 is switched on in cells undergoing some form of stress and that this gene helps to protect the cells. Nrf2 controls a whole network of genes that serve a damage-control function, and this network appears to be activated whenever tissues are stressed.

Soares first observed this tissue damage-control response in mice with malaria. What’s critical about it, he says, is that “it doesn’t touch the pathogen. It just protects you from the damage.” That includes damage caused directly by pathogens, as well as the inevitable collateral damage mediated by an activated immune system and inflammation. This collateral injury is what makes sepsis so dangerous.

The research suggested that if there was a way of switching on the tissue damage-control system, it might quell disease severity. And it appeared that there was such a way. In 2013, a Portuguese group that Soares knows well showed that mice with sepsis could be saved by giving them epirubicin — a 40-year-old drug used in chemotherapy. Epirubicin induces DNA damage, which at high doses kills cancer cells. But at lower doses, it appears to disrupt things just enough to switch on the tissue damage-control response, thereby protecting the mice and preventing sepsis from killing them.

“The way we perceive this,” says Weis, “is if you have an infection and your system is able to adapt to the infection-associated stress, you will not get organ failure.”