THE LAST HOUR

Suddenly, the last hour

before he took me to the airport, he stood up,

bumping the table, and took a step

toward me, and like a figure in an early

science fiction movie he leaned

forward and down, and opened an arm,

knocking my breast, and he tried to take some

hold of me, I stood and we stumbled,

and then we stood, around our core, his

hoarse cry of awe, at the center,

at the end, of our life. Quickly, then,

the worst was over, I could comfort him,

holding his heart in place from the back

and smoothing it from the front, his own

life continuing, and what had

bound him, around his heart—and bound him

to me—now lying on and around us,

sea-water, rust, light, shards,

the little eternal curls of eros

beaten out straight.

~ Sharon Olds, Stag’s Leap

This poem from the latest collection by Sharon Olds has been haunting me. I keep seeing the husband bumping the table as he stands up. Such a small, trivial thing, it happens thousands of times and means nothing, is quickly forgotten -- and yet, in the context of the last hour together, suddenly unforgettable. The whole description of the stumbling is excellent, though I’d gladly skip the simile --“like a figure in an early / science fiction movie he leaned” -- in order to keep the narrative fast-paced. But it could be argued that the simile creates distance and lessens the pain through a bit of humor that, like the attempt at an embrace, doesn’t quite work.

The way these two people who have been married for thirty years now suddenly can’t hug with habitual ease, without awkwardness and bumping and stumbling, says everything. And yet the speaker manages to assume the woman’s archetypal role of the comforter, the ever-supportive angel “holding his heart in place”:

Quickly, then,

the worst was over, I could comfort him,

holding his heart in place from the back

and smoothing it from the front

The wife’s steadying him conveys her understanding and forgiveness. I almost want to exclaim: Are you sure you want to break up? You are still so loving toward each other; you are a good team . . .

For me the poem could end right here: “holding his heart in place from the back / and smoothing it from the front” is brilliant writing, a fusion of metaphor and physical detail; it would make a perfect closure. Until the point the poem is achingly physical. And we are made aware that these two were closely bound by the sexual bond: all the love-making that had gone on for thirty years, what the speaker considers to have been the core of their togetherness:

and then we stood around our core, his

hoarse cry of awe, at the center,

at the end, of our life.

It’s his come-cry that enters here like a ghost, that must be parted with now. And the erotic bond dissolves:

the little eternal curls of eros

beaten out straight.

“Beaten out” is a great choice of words. The couple is no longer in the realm of the winged god.

Still, for all the good moments in this poem, I can’t seem to forget the husband’s bumping the table as he gets up. For some reason that has registered more strongly for me than his bumping her breast in what I assume is a sideways embrace, or in any case an awkward half-embrace. The ghost of his come-cry and the departure of Eros are interwoven here, but the hardness of the table and the slight jabbing pain have a physical reality that engraves itself on memory.

This is meant to be an amicable parting, so there is no mention of the fact that he is leaving for another woman. Besides, and here I speak on the basis of interviews, Olds understands that they had grown unsuited to each other, and this was indeed for the best -- the letting go as the last act of caring, of true love that leaves behind erotic possessiveness. Yet parting is never easy -- not for the one being left, who can’t help feeling hurt, nor for the one doing the leaving, who feels bad about causing the hurt.

*

*“The Last Hour” is a near-perfect example of “taking a narrow slice,” focusing on one specific incident. What defines the moment of parting is the husband’s bumping the table as he rises. I hardly need the rest to tell me about his nervousness and awkwardness -- precisely when he means to be gracious and magnanimously affectionate. This one detail establishes the truthfulness of the poem.

*

Something as mundane as bumping the table selected by the speaker to convey emotional tension reminded me of Akhmatova’s famous lines about the glove from “The Song of the Last Meeting”:

My breast was so cold, so helpless,

But light was my step.

I put the left glove

On my right hand.

Hardly anything is so eloquent as the right detail.

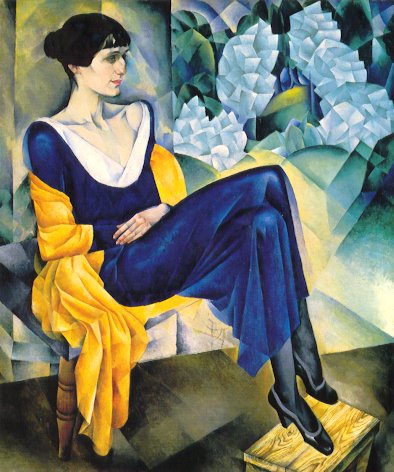

“The Last Hour” also brought back to me Akhmatova’s “Parting.” That poem too has a very memorable opening -- memorable in a different way, not through detail but through a broad, panoramic statement that distills insight about the entire relationship. The poem offers both a “narrow slice” -- the whole extraordinary second section -- and a broader perspective about the years it took these two history-crossed lovers to part (Nikolay Punin, an eminent art critic and curator of the Hermitage museum, died in a gulag).

It is also a poem of irony. “The Last Hour” contains some irony, if that’s the way we choose to look at the awkwardness. But “Parting” delivers painful irony over and over.

The last section is usually presented as a separate poem, and yet I feel it belongs to the sequence, as suggested by one of Akhmatova’s translators, A. S. Kline. In “The Last Toast” history asserts itself, the whole age, “cruel and coarse.” The thirties were a dreadful time in the Soviet Union. When we read Akhmatova, we cannot forget history. The speaker’s personal suffering is a small part of the great grief all around her. As Akhmatova wrote:

That was the time when only the dead

could smile, happy to be at rest.

*

PARTING

I

Not weeks, not months – years

We spent parting. Now at last

The chill of real freedom,

And the gray garland above the temples.

No more treasons, no more betrayals,

And you won’t be listening till dawn

As the stream of evidence

Of my perfect innocence flows on.

II

And as always happens in the last days,

The ghost of the first days knocked at our door,

And in burst the silver willow

In branching magnificence.

To us, frenzied, disdainful and bitter,

Not daring to raise our eyes from the ground,

A bird began to sing in a rapturous voice

About how we cherished each other.

III The Last Toast

I drink to our ruined house,

To all life’s evils too,

To the loneliness we shared,

And I, I drink to you –

To the eyes, dead and cold,

To the lips, lying and treacherous,

To the age, cruel and coarse,

To the fact that God has not saved us.

~ Anna Akhmatova, tr. Judith Hemschemyer and A.S. Kline (modified)

The opening instantly refers to a theme so vast it seems infinite: time. Akhmatova takes in a panorama of time. Though she is “in the moment” in Section II, the emotional power of that section comes from the hold of the past on the present: the return, during the last days, of the “ghost of first days.” But the genius of Section I lies in precisely in distilling the workings of time: “Not weeks, not months -- years / We spent parting.” Anyone who’s been through a reasonably long marriage and a divorce understands this.

But let’s turn to irony. The first instance of irony we encounter lies in the fact that the couple spent years in parting. This goes counter to any romantic notion of marriage. Yet it’s only some couples who keep growing closer over the years, forming a deeper attachment that we honor more than the waning excitement of romantic love. It’s lasting love, the commitment of married love: patiently letting the marriage go through its various stages until a beautiful cooperation prevails. As someone put it, the husband and wife need to realize that they are both on the same side. Sometimes it can’t be done; the two people are too ill-matched, or perhaps the circumstances have changed and are against the marriage. Many couples “keep parting.”

And then comes the overtly ironic statement about what freedom means: now the partner will not have to “listen till dawn / As the stream of evidence / Of my perfect innocence flows on.” The hyperbole of “perfect innocence” makes it plain that the speaker knows that both parties are “guilty” but self-justifying.

In the superb second section, Akhmatova beautifully observes what many others confirmed: that as break-up becomes inevitable, something from the first days of love comes back to remind the couple how intensely they fell for each other. It’s the irony of circumstances: it takes the ending to remember the beginning. The intensity is back, if only temporarily. Some divorcing couples, suddenly again attractive to each other, even being dating again.

Another irony here is very simple: it’s springtime, the season of love. Hence the silver catkins of the willow and the birdsong. There’s freshness and joy in the air -- but these two lovers are parting. (By the way, it’s worth noting that here Akhmatova lets nature come into the poem -- the wider world -- something that we don’t see in Olds’s poem.)

And then the last toast -- surely the most bitter toast in all of poetry. The bitterness is so deep that “sarcasm” would be a better word than mere irony. Normally we raise toast to all the good things in life: health, happiness, prosperity, success. Akhmatova uses the custom of toasting to turn in its head: she raises a toast to dreadful things. Some of it is straightforward irony: instead of drinking to companionship, she drinks to “the loneliness we shared.” But history forces itself in. The lying lips are not just the lover’s lips; they are the lips of spies and others who seek gain in denouncing their neighbors. The lover’s cruelty is overwhelmed by the massive cruelty of the era. And the last illusion is shattered: the speaker knows that “God has not saved us.” This is desolate knowledge: God, to whom millions have been praying for salvation, has not stirred to save anyone -- not the whole country.

As for history, Akhmatova experienced an excess of it. To get the flavor of just how horrible the times were, let’s consider this passage from her biography by Elaine Feinstein:

With Lev [Akhmatova’s son] in the Kresty prison, Akhmatova stood outside in the long queues in the hope of learning something about him, or to beg the guard to take in a food parcel for him. Lydia Chukovskaya [Akhmatova’s close friend] often waited with her in the same queue, hoping to have news of her husband. Unknown to Chukovskaya, Bronstein’s sentence of “ten years’ exile without benefit of correspondence” was in reality a euphemism for execution and he had already been shot.” (p. 169)

The reason that Chukovskaya’s husband was arrested and executed was that his last name happened to be the same as Trotsky’s real last name: Bronstein. It didn’t matter that the husband, like many other Bronsteins in Russia, wasn’t related to the exiled leader of the October Revolution and the organizer of the Red Army, at one time second only after Lenin.

(A shameless digression: A Moscow rabbi said like a prophet, “Lev Trotsky signs the check, but Leyba Davidovich Bronstein will pay the price.”)

Propaganda poster of Trotsky, 1918

Propaganda poster of Trotsky, 1918Why was Akhmatova seen as a threat to the Soviet state? No one denounced her for having written a poem in which Stalin’s mustache is compared to cockroach’s whiskers (that was Mandelstam’s doom). She was known as a poet of love; romantic love and the loss of it are her number one subject. As for later poems such as the Requiem sequence, they were memorized by Akhmatova and Chukovskaya, and the text was burned; the state had no evidence against her. And yet she was a threat precisely as a poet who wrote mainly about love. Or, to put it more broadly, about human connections.

In 1946 Akhmatova was expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers, her poetry denounced as “utterly individualistic.” A totalitarian regime or religion cannot tolerate individualism. Inner life is not even supposed to exist. Instead of giving oneself totally to the service of the state or the church, a true poet dares to write about such private matters as falling in love. It’s not propaganda. Romance is subversive. The family is subversive. Both insist that values other than those officially sanctioned come first. Akhmatova was accused of poisoning the minds of Soviet youth.

Nor is a poet ever going to agree that making a profit is the highest value, so poetry does not go well with unregulated capitalism either. The beloved -- can this word even be pronounced when blind obedience to the state, the church, or any system or institution is demanded?

Nikolay Gumilyov, Lev Gumilyov, Akhmatova, 1913

Lost Tram

It rushed like a dark, winged storm,

And was lost in the abyss of time . . .

Tram-driver, stop,

Stop the tram now.

~ Nikolay Gumilyov (executed in 1921)

(Shameless digression: in a dream I was riding a streetcar in Warsaw. I got off in front of the Polytechnic, where the tracks make a wide turn. A row of chestnut trees. But the street and the tracks suddenly break off into white blankness.)

*

I have long been interested in the question of what makes poem great as opposed to “minor.” I think it’s the largeness of vision that puts Akhmatova in a different rank and gives her work its emotional power. I think my own distinction works well of Olds vs Akhmatova: “poetry as higher journalism” (Olds) versus “poetry as underworld” (spare details presented with the knowledge of Time the Destroyer; death enters in some manner, or, if not death, then silence, sleep, absence).

One could also invoke the difference between information and knowledge. Olds seems intent on exploring and saying everything she can. Akhmatova is careful to leave a lot unsaid, to create an atmosphere of mystery and hidden knowledge.

Finally, Akhmatova supremely musical; she uses the power of rhythm, which good translators try to imitate in English. Thus, even in translation, it becomes obvious why Akhmatova is praised for what’s been called the “epigrammatic beauty of her lines.” I immediately think of

Too sweet is the earthly drink,

Too tight the nets of love

~ but many other lines also easily nestle in memory -- which is not true of Olds’s lines. Even after many years, I remember the content of some of her poems, but not specific lines, with one exception: in “Rites of Passage,” about her little boy’s birthday party, she quotes her son as saying, “We could easily kill a two-year-old.”

When it comes to Akhmatova, I remember a number of her striking lines (all in translation, except for one poem where I simply had to make my slow way through the Russian version). Let me share some of them -- remembering that there is no separating the music and the beauty from the underlying insight.

Like most great poets, Akhmatova also has a simplicity that contains a largeness, a complexity. She juxtaposes nature imagery with emotional and even metaphysical drama like no one else -- unless perhaps Emily Dickinson. If Dickinson went more the way of “wild nights,” perhaps she might sound something like this.

How many demands the beloved can make!

The woman discarded, none.

I am glad that the water today

Stands still under colorless ice.

And I stand -- Christ help me! --

On this shroud that is brittle and bright

*

Neither a rose nor a blade of grass

Will I be in my Father’s garden

*

My night nurse insomnia is visiting elsewhere,

I’m not brooding by a cold hearth.

The crooked hand of the tower clock

Doesn’t look like the arrow of death.

How the past loses power over the heart!

Freedom’s at hand. I forgive everything.

I’m watching a sunbeam run up and down

The first moist ivy of spring.

*

My twin in the mirror will stay up.

I’ll sleep soundly. Good night, night.

*

And this is youth, that glorious time

*

Like happy love,

Calculating and malicious.

*

Don’t kiss me, I am weary.

Death will kiss me.

*

And I knew I’d pay a hundred times

In madhouse, prison, tomb:

Wherever such as I would wake.

But torture by happiness continued.

*

Not for anything would we exchange

This granite city of calamity and fame

*

Do I not talk to you

With the screech of birds of prey?

*

The sky sows a fine rain

On the lilacs in bloom.

At the window beating its wings

Is the white Day of the Holy Ghost.

*

The evening light is yellow and wide,

April is tender and cool.

You have come many years too late . . .

Forgive me for so often

Mistaking other people for you.

*

And the burdocks stand shoulder high,

And the forest of dense nettles sings

*

Why are my fingers covered in blood?

This wine burns like poison.

*

We were fated to learn . . .

What it means to find out in the morning

About those who have died in the night.

##

It remains a luminous fact that in spite of her great suffering Akhmatova did not commit suicide. Yesenin did, then Mayakovski, then Tzvetayeva. Life had become more painful than they could bear. What gave Akhmatova the strength to endure? I think it was her dedication to poetry as the sacred task of her life and the miracle of creativity. Secondly, she identified with Russia, with the greater story of the suffering of her country. In one unforgettable poem, “Belated Reply,” she speaks to Marina Tzvetayeva:

We are together today, Marina,

Walking through the midnight capital,

And behind us there are millions like us.

And never was a procession more hushed,

And around us funeral bells

And the wild Moscow moans

Of a snowstorm erasing our traces.

**

Addendum: Nikolai Kondratiev, the brilliant economist who described the long-term cycles in capitalism, was also executed under the guise of “10 years without the benefit of correspondence.”

John:

Love the ghost of the last days and the ghost of the first days.

Oriana:

I love that too, that ghost of the first days knocking at the door. Wow!

Una:

A fine piece of prose with a depth of meaning many women will relate to.

Now that is the classic Olds that I like very much. Details are one of her specialties, and she has really captured the parting after a long marriage (30 years). I remember saying as I left, “You will always be the father of my children” -- I felt the need to soften the blow.

Akhmatova is amazing. How I’d love to read Russian so I could hear her voice and not the translation. I love the willow’s “branching magnificence"

It is a wonder to know great poetry from the very good. Akhmatova for sure is a great and Sharon is very good.

Oriana:

Now I realize what bothered me about the poem by Olds: too much telling after this:

Quickly, then,

the worst was over, I could comfort him,

holding his heart in place from the back

and smoothing it from the front

For me the poem could end right here: “holding his heart in place from the back / and smoothing it from the front” is wonderful writing, a fusion of metaphor and physical detail; it would make a perfect closure. Until the point the poem is achingly physical.

Olds is precisely the poet who makes some people object that what she writes is “prose with line breaks.” Early Olds seemed more poetic, though even way-back I noticed that after reading those little narratives I didn't feel like re-reading them. The older Olds has more to say, but has gotten too wordy, too prosy. She just doesn't compress enough to make it poetry. It's more like journal writing, though a high-caliber journal writing. And the images sometimes keep me from wanting to re-read, e.g. the image of her ex and his new wife flying together like storks with medical bags in their beaks. Very striking at first, but you don't really want to encounter it again. It's not delightful enough, at least not for me. Too crude or whatever it is.

**

Akhmatova aimed at perfection. I will never forget how a young woman who knew Russian closed her eyes in ecstasy and chanted (rather than merely said), “Akhmatova’s poems in Russian are soooo beautiful . . . soooo beautiful.”

Akhmatova kept her poems short, but they are as if graven in marble. Her conciseness reminds me of Dickinson. Imagine Dickinson as a poet of love, venturing further into wild nights . . . a heady thought.

Kathleen: (reconstructed from memory -- Macbeth, my computer, seems to have concealed Kathleen’s message)

I really like the comments you made about parting, especially the feelings of the one who is being left and of the one who is doing the leaving. Quite perceptive.

Oriana:

If we live long enough, we become well-traveled in heaven and hell -- various circles of hell, so when it’s our turn to do the leaving, we know what it feels like to be left . . .

I think Akhmatova is marvelously perceptive when she says:

Not weeks, not months -- years

We spent parting.

In long-term relationships, the growing apart does take years. But then, beware: in the last days, the ghost of the first days will knock at the door, and the old intensity and mutual attraction may return for a while, the way someone dying often has that last rally of strength: s/he sits up in bed and starts talking with animation, perhaps even planning life after recovery -- the face suddenly much younger . . .

Charles:

When I first looked at the orchid I thought it was a photo.

Love the ad at the top of the page. You are truly a poetreneur.

If you didn't explain Stag's Leap I wouldn't have understood it in such depth. Thank you.

Actually you explained both poems beautifully.

So interesting that Akhmatova was persecuted because she wrote about the individual -- about personal matters such as love.

"The Beloved" can become the state. I see this happening in America now.

Oriana:

That painting by O’Keefe is perhaps the least known among her flower paintings. I love the title even more than the actual painting, though those lacy fringes of petals are irresistible -- like emerging fractals.

It’s not so much the state that become the Beloved as the dictator. We saw this with Hitler, Stalin, Mao, the North Korean dictators. When humans worship someone, it can be romantic infatuation or it can almost as easily be a deity or a dictator.