Inspired by lines from Shelley's Epipsychidion

Even the dim words which obscure thee now

To me are a great city, the wide

polyphonic avenues, and the leafy, quiet

side streets asleep in their own dream.

Beyond that city, a forest, hickory

and pine. Broken shadows. One star.

Full moon paints the ground

like first snow. And that’s me, the dim figure

where the road ends. Or goes

somewhere else. In that shroud of light.

*

I am not thine: I am a part of thee

I will remember you, your arms

the white hem of the returning ocean.

Mount San Miguel glows with sunset

like a rose window lit by centuries.

The ocean waves cool like molten steel.

Venus lights a rippled path. Oh my New Life

that never was, I will remember you

when night breaks in a storm of stars.

*

My moth-like Muse has burned its wings

From the night’s indigo I learned the dark fact:

we don’t choose whom we love or what we love.

My moth-like soul, on singed wings

fly as you burn, star-deep into the night.

*

A well of sealed and secret happiness

When I heard how the monks

plead for the harshest cell, the pit,

I understood my life.

And the weeping within me stopped.

~ Oriana

*

MARY SHELLEY’S THE LAST MAN — WHAT MAKES LIFE WORTH LIVING

Half a century before Walt Whitman considered what makes life worth living when a paralytic stroke bowed him to the ground of being, Mary Shelley (August 30, 1797–February 1, 1851) placed that question at the beating heart of The Last Man (free ebook | public library) — the 1826 novel she wrote in the bleakest period of her life: after the deaths of three of her children, two by widespread infectious diseases that science has since contained; after the love of her life, Percy Bysshe Shelley, drowned in a boating accident.

From that fathomless pit of sorrow, on the pages of a novel about a pandemic that begins erasing the human species one by one until a sole survivor — Shelley’s autobiographical protagonist — remains, she raised the vital question: Why live? By her answer, she raised herself from the pit to go on living, becoming the endling of her own artistic species — Mary Shelley outlived all the Romantics, composing prose of staggering poetic beauty and singlehandedly turning her then-obscure husband into the icon he now is by her tireless lifelong devotion to the posthumous editing, publishing, and glorifying of his poetry.

Shelley had set her far-seeing Frankenstein, written a decade earlier, a century into her past; she sets The Last Man a quarter millennium into her future, in the final decade of the twenty-first century, culminating in the year 2092 — the tricentennial of her beloved’s birth.

The novel’s narrator, Lionel Verney — an idealistic young man, more porous than most to both the deepest suffering of living and the most transcendent beauty of life — is the closest Mary Shelley, stoical and guarded, came to painting a psychological self-portrait. As the pandemic sweeps the world and vanquishes his loved ones one by one, Shelley’s protagonist returns home to seek safety “as the storm-driven bird does [to] the nest in which it may fold its wings in tranquillity.” There, in the strange stillness, stripped of the habitual busynesses and distractions of social existence, he finds himself contemplating the essence of life:

~ How unwise had the wanderers been, who had deserted [the nest’s] shelter, entangled themselves in the web of society, and entered on what men of the world call “life,” — that labyrinth of evil, that scheme of mutual torture. To live, according to this sense of the word, we must not only observe and learn, we must also feel; we must not be mere spectators of action, we must act; we must not describe, but be subjects of description. Deep sorrow must have been the inmate of our bosoms… sickening doubt and false hope must have chequered our days… Who that knows what “life” is, would pine for this feverish species of existence? I have lived. I have spent days and nights of festivity; I have joined in ambitious hopes…: now — shut the door on the world, and build high the wall that is to separate me from the troubled scene enacted within its precincts. ~

In consonance with Whitman — “After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains?” the American poet would ask across space and time, then answer: “Nature remains.” — Shelley’s protagonist finds the meaning of life not in the whirlwind of the human-made world with its simulacra of living but in the simple creaturely presence with nature’s ongoing symphony of life:

Let us… seek peace… near the inland murmur of streams, and the gracious waving of trees, the beauteous vesture of earth, and sublime pageantry of the skies. Let us leave “life,” that we may live.

At the height of the deadly pandemic, nature seems all the more quietly determined to affirm the resilience of life — spring arrives with its irrepressible bursts of beauty, untrammeled by human suffering and a supreme salve for it. It is by observing nature’s unbidden delirium in its littlest expression, by surrendering to its sweep, that Lionel regains his faith not only in survival but in the beauty, the worthiness of life.

A generation before the young Emily Dickinson delighted in the poetry of spring, Shelley writes:

Winter passed away; and spring, led by the months, awakened life in all nature. The forest was dressed in green; the young calves frisked on the new-sprung grass; the wind-winged shadows of light clouds sped over the green cornfields; the hermit cuckoo repeated his monotonous all-hail to the season; the nightingale, bird of love and minion of the evening star, filled the woods with song; while Venus lingered in the warm sunset, and the young green of the trees lay in gentle relief along the clear horizon.

From this open presence with the non-human world, Shelley’s protagonist extracts the essence of what it means to be human:

~ There is but one solution to the intricate riddle of life; to improve ourselves, and contribute to the happiness of others. ~

Oriana:

That’s my resolution regardless of who wins the election, but particularly if the side threatening us with shooting squads does — to dive into beauty as if my life depended on it, because it does.

In terms of impact on Western culture, Mary Shelley left a greater impact than her husband, yet "back in my days," college curricula mentioned her merely as a footnote to her husband.

*

Think well before you say something, and after you think, don't say anything. ~ Chinese proverb

*

Word of the day: LATIBULATE = to stand in a corner in order to escape reality

*

THE FORCE OF CHANCE: THE DISCOVERY OF THE CHAOS THEORY

The social world doesn’t work how we pretend it does. Too often, we are led to believe it is a structured, ordered system defined by clear rules and patterns. The economy, apparently, runs on supply-and-demand curves. Politics is a science. Even human beliefs can be charted, plotted, graphed. And using the right regression we can tame even the most baffling elements of the human condition. Within this dominant, hubristic paradigm of social science, our world is treated as one that can be understood, controlled and bent to our whims. It can’t.

Our history has been an endless but futile struggle to impose order, certainty and rationality onto a Universe defined by disorder, chance and chaos. And, in the 21st century, this tendency seems to be only increasing as calamities in the social world become more unpredictable. From 9/11 to the financial crisis, the Arab Spring to the rise of populism, and from a global pandemic to devastating wars, our modern world feels more prone to disastrous ‘shocks’ than ever before.

Though we’ve got mountains of data and sophisticated models, we haven’t gotten much better at figuring out what looms around the corner. Social science has utterly failed to anticipate these bolts from the blue. In fact, most rigorous attempts to understand the social world simply ignore its chaotic quality – writing it off as ‘noise’ – so we can cram our complex reality into neater, tidier models. But when you peer closer at the underlying nature of causality, it becomes impossible to ignore the role of flukes and chance events. Shouldn’t our social models take chaos more seriously?

The problem is that social scientists don’t seem to know how to incorporate the nonlinearity of chaos. For how can disciplines such as psychology, sociology, economics and political science anticipate the world-changing effects of something as small as one consequential day of sightseeing or as ephemeral as passing clouds?

*

On 30 October 1926, Henry and Mabel Stimson stepped off a steam train in Kyoto, Japan and set in motion an unbroken chain of events that, two decades later, led to the deaths of 140,000 people in a city more than 300 km away.

The American couple began their short holiday in Japan’s former imperial capital by walking from the railway yard to their room at the nearby Miyako Hotel. It was autumn. The maples had turned crimson, and the ginkgo trees had burst into a golden shade of yellow. Henry chronicled a ‘beautiful day devoted to sightseeing’ in his diary.

Nineteen years later, he had become the United States Secretary of War, the chief civilian overseeing military operations in the Second World War, and would soon join a clandestine committee of soldiers and scientists tasked with deciding how to use the first atomic bomb. One Japanese city ticked several boxes: the former imperial capital. The Target Committee agreed that Kyoto must be destroyed. They drew up a tactical bombing map and decided to aim for the city’s railway yard, just around the corner from the Miyako Hotel where the Stimsons had stayed in 1926.

Stimson pleaded with the president Harry Truman not to bomb Kyoto. He sent cables in protest. The generals began referring to Kyoto as Stimson’s ‘pet city’. Eventually, Truman acquiesced, removing Kyoto from the list of targets. On 6 August 1945, Hiroshima was bombed instead.

The next atomic bomb was intended for Kokura, a city at the tip of Japan’s southern island of Kyushu. On the morning of 9 August, three days after Hiroshima was destroyed, six US B-29 bombers were launched, including the strike plane Bockscar. Around 10:45am, Bockscar prepared to release its payload. But, according to the flight log, the target ‘was obscured by heavy ground haze and smoke’. The crew decided not to risk accidentally dropping the atomic bomb in the wrong place.

Bockscar then headed for the secondary target, Nagasaki. But it, too, was obscured. Running low on fuel, the plane prepared to return to base, but a momentary break in the clouds gave the bombardier a clear view of the city. Unbeknown to anyone below, Nagasaki was bombed due to passing clouds over Kokura. To this day, the Japanese refer to ‘Kokura’s luck’ when one unknowingly escapes disaster.

Roughly 200,000 people died in the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – and not Kyoto and Kokura – largely due to one couple’s vacation two decades earlier and some passing clouds. But if such random events could lead to so many deaths and change the direction of a globally destructive war, how are we to understand or predict the fates of human society? Where, in the models of social change, are we supposed to chart the variables for travel itineraries and clouds?

In the 1970s, the British mathematician George Box quipped that ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’. But today, many of the models we use to describe our social world are neither right nor useful. There is a better way. And it doesn’t entail a futile search for regular patterns in the maddening complexity of life. Instead, it involves learning to navigate the chaos of our social worlds.

Before the scientific revolution, humans had few ways of understanding why things happened to them. ‘Why did that storm sink our fleet?’ was a question that could be answered only with reference to gods or, later, to God. Then, in the 17th century, Isaac Newton introduced a framework where such events could be explained through natural laws. With the discovery of gravity, science turned the previously mysterious workings of the physical Universe – the changing of the tides, celestial movements, falling objects – into problems that could be investigated. Newtonian physics helped push human ideas about causality from the unknowable into the merely unknown.

A world ruled by gods is fundamentally unknowable to mere mortals, but, with Newton’s equations, it became possible to imagine that our ignorance was temporary. Uncertainty could be slain with intellectual ingenuity. In 1814, for example, the French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace published an essay that imagined the possible implications of Newton’s ideas on the limits of knowledge. Laplace used the concept of an all-knowing demon, a hypothetical entity who always knew the positions and velocities of every particle in Newton’s deterministic universe. Using this power, Laplace’s demon could process the full enormity of reality and see the future as clearly as the past.

These ideas changed how we conceived of the fundamental nature of our world. If we are the playthings of gods, then the world is fundamentally and unavoidably unruly, swayed by unseen machinations, the whims of trickster deities and their seemingly random shocks unleashed like bolts of lightning from above. But if equations are our true lords, then the world is defined by an elegant, albeit elusive, order. Unlocking the secrets of those equations would be the key to taming what only seemed unruly due to our human ignorance. And in that world of equations, reality would inevitably converge toward a series of general laws. As scientific progress advanced in the 19th and 20th centuries, Laplace’s demon became increasingly plausible. Better equations, perhaps, could lead to godlike foresight.

The search for patterns, rules and laws wasn’t limited only to the realm of physics. In biology, Darwinian principles provided a novel guide to the rise and fall of species: evolution by natural selection acted like an ordered guardrail for all life. And as the successes of the natural sciences spread, scholars who studied the dynamics of culture began to believe that the rules of biology and physics could also be used to describe the patterns of human behavior. If there was a theoretical law for something as mysterious as gravity, perhaps there were similar rules that could be applied to the mysteries of human behavior, too?

One scholar who put such an idea in motion was the French social theorist Henri de Saint-Simon. Believing that scientific laws underpinned social behavior, Saint-Simon proposed a more systematic, scientific approach to social organization and governance. Social reform, he believed, would flow inexorably from scientific research. The French philosopher Auguste Comte, a contemporary of Saint-Simon and founder of the discipline of sociology, even referred to the study of human societies as ‘social physics’. It was only a matter of time, it seemed, for the French Revolution to be understood as plainly as the revolutions of the planets.

But there were wrinkles in this world of measurement and prediction, which the French mathematician Henri Poincaré anticipated in 1908: ‘it may happen that small differences in the initial conditions produce very great ones in the final phenomena. A small error in the former will produce an enormous error in the latter.’

*

The first of those wrinkles was discovered by the US mathematician and meteorologist Edward Norton Lorenz. Born in 1917, Lorenz was fascinated by the weather as a young boy, but he left that interest behind in the mid-1930s when he began studying mathematics at Harvard University. During these studies, the Second World War broke out and Lorenz spotted a flyer recruiting for a weather forecasting unit. He jumped at the chance to return to his childhood fascination. As the war neared its end in 1945, Lorenz began forecasting cloud cover for bombing runs over Japan. Through this work, he started to understand the severe limitations of weather prediction – forecasting was not an exact science. And so, after the war, he returned to his mathematical studies, working on predictive weather models in the hope of giving humanity a means of more accurately glimpsing the future.

One day in 1961, while modeling the weather using a small set of variables on a simple, premodern computer, Lorenz decided to save time by restarting a simulation that had been stopped halfway through. The same simulation had been run previously, and Lorenz was running it again as part of his research. He printed the variables out, then programmed the numbers back into the machine and waited for the simulation to unfold as it had before.

At first, everything looked identical, but over time the weather patterns began to diverge dramatically. He assumed there must have been an error with the computer.

After much chin-scratching and scowling over the data, Lorenz made a discovery that forever upended our understanding of systemic change. He realized that the computer printouts he had used to run the simulation were truncating the values after three decimal points: a value of 0.506127 would be printed as 0.506. His astonishing revelation was that the tiniest measurement differences – seemingly infinitesimal, meaningless rounding errors – could radically change how a weather system evolved over time. Tempests could emerge from the sixth decimal point.

If Laplace’s demon were to exist, his measurements couldn’t just be nearly perfect; they would need to be flawless. Any error, even a trillionth of a percentage point off on any part of the system, would eventually make any predictions about the future futile. Lorenz had discovered chaos theory.

The Lorenz attractor is the iconic representation of chaos theory.

The core principle of the theory is this: chaotic systems are highly sensitive to initial conditions. That means these systems are fully deterministic but also utterly unpredictable. As Poincaré had anticipated in 1908, small changes in conditions can produce enormous errors. By demonstrating this sensitivity, Lorenz proved Poincaré right.

Chaos theory, to this day, explains why our weather forecasts remain useless beyond a week or two. To predict meteorological changes accurately, we, like Laplace’s demon, would have to be perfect in our understanding of weather systems, and – no matter how advanced our supercomputers may seem – we never will be. Confidence in a predictable future, therefore, is the province of charlatans and fools; or, as the US [Buddhist] theologian Pema Chödrön put it: ‘If you’re invested in security and certainty, you are on the wrong planet.’

The second wrinkle in our conception of an ordered, certain world came from the discoveries of quantum mechanics that began in the early 20th century. Seemingly irreducible randomness was discovered in bewildering quantum equations, shifting the dominant scientific conception of our world from determinism to indeterminism (though some interpretations of quantum physics arguably remain compatible with a deterministic universe, such as the ‘many-worlds’ interpretation, Bohmian mechanics, also known as the ‘pilot-wave’ model, and the less prominent theory of superdeterminism).

Scientific breakthroughs in quantum physics showed that the unruly nature of the Universe could not be fully explained by either gods or Newtonian physics. The world may be defined, at least in part, by equations that yield inexplicable randomness. And it is not just a partly random world, either. It is startlingly arbitrary.

Consider, for example, the seemingly ordered progression of Darwinian evolution. Alfred Russel Wallace, who discovered evolution around the same time as Charles Darwin, believed that the principles of life had a structured purpose – they were teleological. Darwin was more skeptical. But neither thinker could anticipate just how arbitrary much of evolutionary change would turn out to be.

In the 1960s, the Japanese evolutionary biologist Motoo Kimura discovered that most of the genomic tweaks driving evolution at the molecular level are neither helpful nor harmful. They are fundamentally arbitrary, even accidental. Kimura called this the ‘neutral theory of molecular evolution’. Other scientists noticed it, too, whether they were studying viruses, fruit flies, blind mole rats, or mice. Evidence began to accumulate that many evolutionary changes in species weren’t driven by structured or ordered selection pressures. They were driven by the forces of chance.

The US biologist Richard Lenski’s elegant long-term evolution experiment, which has been running since 1988, demonstrated that important adaptations that help a species (such as E coli) thrive can emerge after a chain of broadly meaningless mutations. If any one of those haphazard and seemingly ‘useless’ tweaks hadn’t occurred, the later beneficial adaptation wouldn’t have been possible. Sometimes, there’s no clear reason, no clear pattern. Sometimes, things just happen.

E coli populations from Richard Lenski’s long-term evolution experiment, 25 June 2008

Kimura’s own life was an illustration of the arbitrary forces that govern our world. In 1944, he enrolled at Kyoto University, hoping to continue his intellectual pursuits while avoiding conscription into the Japanese military. If Henry Stimson had chosen a different destination for his sightseeing vacation in 1926, Kimura and his fellow students would likely have been incinerated in a blinding flash of atomic light.

*

Linear regressions rely on several assumptions about human society that are obviously incorrect. In a linear equation, the size of a cause is proportionate to the size of its effect. That’s not how social change works. Consider, for example, that the assassination of one man, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, triggered the First World War, causing roughly 40 million casualties. Or think of the single vegetable vendor who lit himself on fire in central Tunisia in late 2010, sparking events that led to the Syrian civil war, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths and the fall of several authoritarian regimes. More recently, a bullet narrowly missed killing Donald Trump in Pennsylvania: if the tiniest gust of wind or a single bodily twitch had altered its trajectory, the 21st century would have been set on a different path. This exemplifies chaos theory in the social world, where tiny changes in initial conditions can transform countless human fates.

Another glaring problem is that most linear regressions assume that a cause-and-effect relationship is stable across time. But our social world is constantly in flux. While baking soda and vinegar will always produce a fizz, no matter where or when you mix them together, a vegetable vendor lighting himself on fire will rarely produce regional upheaval. Likewise, many archdukes have died – only one has ever triggered a world war.

Timing matters, too. Even if the exact same mutation in the exact same coronavirus had broken out in the exact same place, the economic effects and social implications of the ensuing pandemic would have been drastically different if it had struck in 1990 instead of 2020. How would millions of people have worked from home without the internet? Pandemics, like many complex social phenomena, are not uniformly governed by stable, ordered patterns. This is a principle of social reality known to economists as ‘nonstationarity’: causal dynamics can change as they are being measured. Social models often deal with this problem by ignoring it.

The deeply flawed assumptions of social modeling do not persist because economists and political scientists are idiots, but rather because the dominant tool for answering social questions has not been meaningfully updated for decades. It is true that some significant improvements have been made since the 1990s. We now have more careful data analysis, better accounting for systematic bias, and more sophisticated methods for inferring causality, as well as new approaches, such as experiments that use randomized control trials. However, these approaches can’t solve many of the lingering problems of tackling complexity and chaos. For example, how would you ethically run an experiment to determine which factors definitively provoke civil wars? And how do you know that an experiment in one place and time would produce a similar result a year later in a different part of the world?

Chaos theory emerged in the 1960s and, in the following decades, mathematical physicists such as David Ruelle and Philip Anderson recognized the significance of Lorenz’s insights for our understanding of real-world dynamical systems. As these ideas spread, misfit thinkers from an array of disciplines began to coalesce around a new way of thinking that was at odds with the mainstream conventions in their own fields. They called it ‘complexity’ or ‘complex systems’ research. For these early thinkers, Mecca was the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, not far from the sagebrush-dotted hills where the atomic bomb was born. But unlike Mecca, the Santa Fe Institute did not become the hub of a global movement.

Public interest in chaos and complexity surged in the 1980s and ’90s with the publication of James Gleick’s popular science book Chaos (1987), and a prominent reference from Jeff Goldblum’s character in the film Jurassic Park (1993). ‘The shorthand is the butterfly effect,’ he says, when asked to explain chaos theory. ‘A butterfly can flap its wings in Peking and in Central Park you get rain instead of sunshine.’ But aside from a few fringe thinkers who broke free of disciplinary silos, social science responded to the complexity craze mostly with a shrug. This was a profound error, which has contributed to our flawed understanding of some of the most basic questions about society. Taking chaos and complexity seriously requires a fresh approach.

When we try to explain our social world, we foolishly ignore the flukes. We imagine that the levers of social change and the gears of history are constrained, not chaotic. We cling to a stripped-down, storybook version of reality, hoping to discover stable patterns. When given the choice between complex uncertainty and comforting – but wrong – certainty, we too often choose comfort.

In truth, we live in an unruly world often governed by chaos. And in that world, the trajectory of our lives, our societies and our histories can forever be diverted by something as small as stepping off a steam train for a beautiful day of sightseeing, or as ephemeral as passing clouds.

~ Parts of this essay were adapted from Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters (2024) by Brian Klaas.

We control nothing, but influence everything. ~ Brian Klaas

Udit Narayan:

This perspective is very useful for understanding the workings of the real world. Interestingly, complex adaptive systems theory has already been scholarly applied to a very unsusual field of mass hostage rescue in a seminal and exhaustive book Dignity of Life: Moral Philosophy, Organizonal Theory, and Hostage Rescue by Avichal (2023). I read it recently and Brian Klaas may also look into it; the author shares his vision

Michael Coney:

Great article about a fundamentally important fact of life. Despite our best effort to understand and control it, our social world is fundamentally chaotic and unpredictable. The tragedy is that people don’t know it or believe it or worse believe that everything is divinely ordered and controlled by prayer.

It’s not clear to me—a retired actuary who spent 50 years measuring risk and forecasting economic loss—that scientific attempts to model it will ever reach a point that would produce accurate forecasts. The precision required of model parameters and calculations increases exponentially with the forecast period. The upside: We try anyway and get paid for it.

Aarush Buthra:

This article is a powerful reminder that chaos and randomness play an unavoidable role in shaping history and society. It challenges the belief that we can fully control or predict outcomes through models, suggesting instead that we must embrace uncertainty. In a world driven by chance events, perhaps the best we can do is learn to navigate the unpredictable currents, not master them.

Michael Mcbrearty:

In the intellectual landscape of the micro-historian, there are no forests, only trees. Marx believed that the moving force behind the apparent chaos of history is the conflict between the ruling class and the oppressed class

Haywood Blum:

Not all things social need to be explained by Chaos theory. As an example from physics, consider a container of gas, filled with innumerable molecules moving randomly. With the use of statistical mechanics one can understand not only the laws governing how a gas maintains a pressure but also what one means by temperature. The averaging over the great number of microscopic molecules results in a marvelous interpretation of a macroscopic emergent property. In a similar fashion, Einstein showed the existence of molecules through his derivation of the properties of Brownian motion. In the stock market, charting produced winning protocols early on, although now supplanted by other techniques.

Mike Davis:

We are are determined by our genetics, biology and experiences. Chaos is something that we can’t control by faith or reasoning, but is extremely important and necessary to our values and existence. Make the best of what you have, grow with understanding of your limitations and find happiness being the best you can. Forget about free will, you can’t ‘control’ your height or the relationship that was determined by the natural phenomenon of life. Social science is perfectly suited to address this contradiction and contrasting difference in the philosophy of free will vs determinism.

*

TRUMP SAYS HE REGRETS HAVING LEFT THE OFFICE IN 2021

Donald Trump, who said in Pennsylvania on Sunday that he regrets leaving the White House in 2021, is ending the 2024 campaign the way he began it — dishing out a stew of violent, disparaging rhetoric and repeated warnings that he will not accept defeat if it comes.

At a rally in the must-win battleground state, the former president told supporters that he “shouldn’t have left” office after losing the 2020 election; described Democrats as “demonic”; complained about a new poll that shows him no longer leading in Iowa, a state he twice carried; and said he wouldn’t mind if a gunman aiming at him also shot through “the fake news.”

Trump spent much of his speech pushing unfounded claims of cheating by Democrats in the 2024 election and sowing doubts about its integrity as polls show him and Vice President Kamala Harris deadlocked nationally. He ranted about alleged election interference this year and lamented his departure from office after losing to Joe Biden four years ago.

“I shouldn’t have left. I mean, honestly, because we did so, we did so well,” Trump said during his rally in Lititz as he claimed the US-Mexico border was more secure under his administration.

It was a rare public admission of regret over participating in the peaceful transfer of power after he incited his supporters to violently storm the US Capitol as he tried to subvert the results of the 2020 election that he lost but refused to concede — something Trump is currently facing federal charges over.

Trump, whose voice sounded hoarse throughout his speech, repeatedly railed against the new Iowa survey released Saturday night, which showed no clear leader between him and Harris in the state.

“We got all this crap going on with the press and with fake stuff and fake polls,” Trump said, claiming the poll from the Des Moines Register and Mediacom was put out by “one of my enemies.”

At one point, the former president, who has been the target of two assassination attempts, suggested he’d be OK with a gunman aiming at him also shooting through the “the fake news.”

“I have this piece of glass here. But all we have really over here is the fake news, right? And to get me, somebody would have to shoot through the fake news,” Trump said. “And I don’t mind that so much. I don’t mind.”

A Trump campaign spokesman said after the rally that the former president was actually musing about how the press was protecting him.

“President Trump was stating that the Media was in danger, in that they were protecting him and, therefore, were in great danger themselves, and should have had a glass protective shield, also. There can be no other interpretation of what was said. He was actually looking out for their welfare, far more than his own!” Steven Cheung said in a statement.

Responding to Trump’s comments Sunday, a senior Harris campaign official said in a call with reporters that “for Trump, this election really is all about his own grievances and he’s not focused on the American people.”In his speech, Trump baselessly claimed Democrats are “fighting so hard to steal this damn thing,” and that voting machines would be tampered with.

“They spend all this money, all this money on machines, and they’re going to say, we may take an extra 12 days to determine. And what do you think happens during that 12 days? What do you think happens?” Trump said.

The crowd yelled back: “Cheating!”

“These elections have to be, they have to be decided by 9 o’clock, 10 o’clock, 11 o’clock on Tuesday night. Bunch of crooked people, these are crooked people,” Trump said.

The former president’s newest round of threats caps off a campaign with one of the darkest, most menacing closing messages in modern American history. In the last few weeks alone, Trump has doubled down on a pledge to use the military to combat the civilian “enemy within” and mused — in the guise of arguing he was the pro-peace candidate — about how former Rep. Liz Cheney, one of his loudest conservative Republican critics, would fare with guns “trained on her face” in a war zone.

This weekend has brought its own slate of bizarre moments. On Sunday, Trump told NBC News that Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s recent post on X about removing fluoride from public water if Trump were to win a second term “sounds OK to me.”

“Well, I haven’t talked to him about it yet, but it sounds OK to me,” Trump told NBC. “You know, it’s possible.”

And a night earlier in North Carolina, Trump chuckled approvingly at an audience member’s suggestion that Harris worked as a prostitute. After Trump insisted yet again that Harris did not work in a McDonald’s when she was younger, a supporter in Greensboro shouted, “She worked on a corner!”

Trump laughed, paused for a beat, then declared, “This place is amazing.”

As the crowd laughed, he added: “Just remember it’s other people saying it, it’s not me.”

His response to the crude remark underscored how the rot in American political discourse, a long-running spiral, went into overdrive after Trump’s arrival on the presidential campaign trail in 2015. It’s a contrast from seven years earlier, when a supporter of John McCain said during a campaign event that Barack Obama was lying about his identity, claiming, “He’s an Arab,” and the then-GOP nominee took the microphone from her hands, insisting his rival was “a decent family man (and) citizen that just I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues.”

Even then, though, Trump was lurking. He would soon emerge as one of the leading proponents of the “birther” conspiracy theory, a racist narrative that said Obama was not born in the US.

In the run-up to this year’s election, Trump has used the former president’s full name — Barack Hussein Obama — in an attempt to demonize him. He frequently mispronounces Harris’ first name, though he has shown before he knows the proper way to say it, and called her a “sh*t vice president.”

At other times, Trump has descended into farce. During a rally in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, last month, he spent some time recalling the late, great golfer Arnold Palmer’s naked body.

“Arnold Palmer was all man, and I say that in all due respect to women, I love women,” Trump said. “This man was strong and tough, and I refused to say it, but when he took showers with the other pros they came out of there, they said, ‘Oh, my God. That’s unbelievable.’”

Trump’s message to — and more often, about — women has also become increasingly bizarre. At a rally in Green Bay, Wisconsin, last week, he told the crowd that his aides had asked him to stop saying he would be the “protector” of American women, in part because they recognized it as inappropriate.

“‘Sir, please don’t say that,’” Trump said he was advised. “Why? I’m president. I want to protect the women of our country. Well, I’m going to do it, whether the women like it or not.”

Recent polls have shown the former president trailing Harris with female voters by a significant margin across demographic lines. Neither Trump nor his allies have pushed back on the numbers, instead imploring more men to vote.

“Early vote has been disproportionately female,” said Charlie Kirk, the leader of a right-wing group that Trump has entrusted with managing much of his ground game. “If men stay at home, Kamala is president. It’s that simple.”

Harris has mostly countered Trump’s bleak offerings with promises to bring an end to the tribal clashes that have defined most of the past decade.

“Our democracy doesn’t require us to agree on everything. That’s not the American way,” Harris said during a speech last week from the Ellipse in Washington, DC. “We like a good debate. And the fact that someone disagrees with us, does not make them ‘the enemy from within.’ They are family, neighbors, classmates, coworkers.”

“It can be easy to forget a simple truth,” she added. “It doesn’t have to be this way.”

The vice president has also zeroed in on Trump’s attacks on rivals and detractors, including a persistent insistence he wants to use the power of the federal government to punish them. By contrast, Harris likes to say, she is focused on policy, like a push to restore federal abortion rights following the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade.

“On day one, if elected, Donald Trump would walk into that office with an enemies list,” Harris said in Washington. “When elected, I will walk in with a to-do list full of priorities on what I will get done for the American people.”

https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/03/politics/trump-dark-closing-message/index.html

“I saw him when the cameras were off, behind closed doors. Trump mocks his supporters. He calls them basement dwellers. He was mad that the cameras were not watching him. He has no empathy, no morals and no fidelity to the truth. He used to tell me, ‘It doesn’t matter what you say, Stephanie — say it enough and people will believe you.’ But it does matter — what you say matters, and what you don’t say matters.”

*

AFTER STALIN DIED

After Stalin’s death, he was announced a tyrant who abused power, and he wasn’t considered a positive historical figure — until Vladimir Putin came to power and started promoting Stalin as a hero.

Because Putin wanted to be just like him.

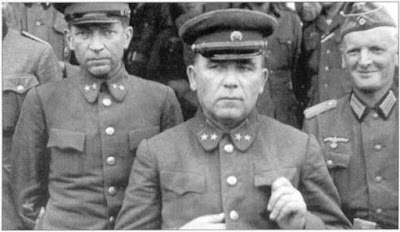

From left: Malenkov (standing), Beria, Khrushchev, Stalin

After Stalin’s death in 1953 (reportedly, he died in a puddle of his own urine after a stroke, no one was willing to help him — not even his own guards), the power struggle among top communists began.

Malenkov, Beria, and Khrushchev all competed for the position of the leader.

Malenkov immediately established himself in Stalin’s cabinet in the Kremlin and took Stalin’s title of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers. That was the most powerful position at the time.

Beria, who was the chief of secret police (predecessor of the KGB), became Malenkov’s first deputy and head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

In June 1953, Beria was arrested on accusations of spying (the same accusation his department used in purges) — his arrest was engineered by Khruschev.

After the arrest of Beria, Nikita Khrushchev requested to create the position of the First Secretary of the communist party's Central Committee in September 1953, which he took for himself — and used it to become de facto leader of the USSR.

Beria was executed in December 1953, together with the group of his close supporters. All of them were accused of treason, trying to destroy the Soviet system and restore capitalism.

Malenkov spoke about Stalin’s “cult of personality” already in 1955. However, Malenkov was forced to leave his post after accusations of abuse of power. Khrushchev got rid of another competitor.

In 1956, Khrushchev made a report on the 20th Congress of the Communist party, where he denounced Stalin's “cult of personality” and condemned mass terror, initiating "de-Stalinisation" of the Soviet society.

Nikita Khruschev at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR in 1956 (it’s also known as “the Congress of those who Survived” — those top communists who were not arrested or killed under Stalin).

By that time, there had already been thousands of rehabilitation cases open for victims of Stalin's purges — but there wasn’t an official condemnation of the deceased leader of the USSR.

As Khrushchev was talking about Stalin’s crimes, someone from the audience yelled, “So, why didn’t you say anything before?”

Khruschev barked aggressively: “Who said that?!”

Silence in the audience was palpable.

”That’s why,” calmly stated Khrushchev. ~ Elena Gold, Quora

Luke Hatherton:

Stalin’s inner circle was frequently forced to attend late-night dinner parties with him, as he was terrified of being alone (and simultaneously always paranoid of assassination or being overthrown, especially as he got old and sick). He would tell Khrushchev to do his traditional peasant dances. Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs, “When Stalin says dance, a wise man dances”.

Without Stalin, there never would have been a WW2. The fear of Stalin was a key reason why the Nazi Party was able to gain power in Germany. Stalin also sabotaged the German communist party, as only he could be the leader of the world communist revolution. He had no idea what Hitler was capable of.

The rapid industrialization wouldn’t have been nearly as costly if someone less brutal than Stalin had directed it. The Gulag always operated at a loss — slave labor is not efficient. It would have been much better if all those people had been legitimately employed and treated humanely. When Beria of all people was appointed head of the NKVD, he recognized this and improved conditions in the camps to increase productivity.

The Holodomor and the collectivization famine in general happened because Stalin was a bumbling figure whom everyone was afraid to say no to and also because Stalin saw that Ukraine was suffering and took the opportunity to destroy Ukrainian morale by allowing millions to starve. Many historians recognize the Holodomor as a genocide, and those who don’t recognize it as a crime against humanity.

The purges were a complete waste of human capital — there was no plot in the military, and so many apparently secretly plotting writers and musicians were murdered.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact gave Hitler a free hand to fight on one front and win the Battle of France. Then he turned on Stalin. The culture of fear Stalin had instilled in the military was a significant factor in the disasters of Barbarossa, as everyone was terrified to make any major decisions without Stalin’s explicit consent. Stalin was also militarily incompetent. He issued insane stand-fast orders, one of which, despite repeated requests to withdraw by the commanding general, led to the largest encirclement in history at Kiev.

After the successful Soviet offensive that saved Moscow in December 1941, Stalin became overconfident and, against the advice of Zhukov, whom had already proven himself right that Moscow could be held when Stalin asked him to speak bluntly in October 1941, Stalin launched offensives up and down the front that winter and spring, which were all smashed with huge losses. These defeats allowed Germany to launch the massive Case Blue summer offensive in 1942, which led to further huge losses for the Soviet Union and further starvation as the Nazis occupied the rich Caucasus breadbasket.

So yeah, the nearly uninterrupted string of disasters that marked the first year of the Great Patriotic War were mostly Old Joe’s fault. Coming back from them was very difficult, and the Soviet Union barely survived.

The Soviet Union would have been better off if Stalin had never existed. Another nasty figure or group of figures would have occupied a similar position, as in a fundamentally corrupt system like Bolshevism, the shit floated to the top, but a lot of what happened need not have happened even under that regime, with somebody different and less *totally* amoral and horrifying.

Some Russians continue to worship Stalin

*

WHY RUSSIA IS PARANOID

~ It all begins in 1223 and the first Mongol invasion of Russia.

When the Mongols first invaded Russia, the country was wildly divided into mutually hostile and competing princedoms, whose cooperation was rather bad. The Mongols were expert spies, and quickly found out the weaknesses of the Russians. It all ended in the battle of river Kalka, where the Russian army was obliterated.

Fourteen years later Mongols conquered Russia and subjugated it. The Western influence in Russia ended and Russia slid irrevocably into the Mongol cultural sphere. The 243 years of slavery — the Mongol Yoke — began.

The Russians adopted the Mongol style of government, the Mongol ruthlessness and disregard of human lives, the Patrimonial concept of state and the concept of Derzhava — monolithic, single empire under the scepter of one man and everything within being his personal property. The Russians realized the Kievan Rus fell because it was so divided and individualistic; the remedy of this weakness would be a monolithic state where absolutely everything has been concentrated to one single ruler.

Derzhava describes “a strong state with the idea of a great power and protection from foreign threats”. By projecting Russia as Derzhava, i.e., a powerful state able to defend its distinct interests and norms, Russian statecraft has aimed to compensate for Russia’s semi-peripheral position in the global arena and for its historical socioeconomic backwardness.

These concepts — ruthlessness, disregard of human lives, tyrannical totalitarian government, Authoritarian Patrimonialism, Derzhava, absolutely disdain on any human dignity, international treaties, international laws, human rights and respecting only physical violence or threat of thereof — have been the characteristics of Russia ever since 1480 and battle of Urga river.

The very system of Russia — Authoritarian Patrimonialism — creates an atmosphere of distrust, paranoia, suspicion and fear. Poison and dagger have always been perfectly good means of making politics in Russia, and everyone wants to be the caliph instead of caliph. The country is full of Iznogouds and no Harun el Plassid anywhere. Add in the Russian characteristic dishonesty, propensity to cheat and play foul game whenever there is a chance, and their propensity to understand truth and lie not as binary concepts as in West, but as a subjective and relative thing, the soup is ready.

Of all forms of Christianity, Orthodoxism is the most rotten and corrupt, and in Russia, the church has always been merely the ruler’s tool to fool, subjugate and deceive the subjects. The czarist state dominated the Orthodox Church, but by making its priests into government employees, it won their loyalty and obedience. With one swoop, the state cemented an alliance with Russia's intellectual class. The intelligentsia thus were not independent critics of the state, but its hired apologists. Such twisted religion, emerging from a palace to establish order in a military encampment, cannot fulfill the highest needs of the human soul, but merely assists the police in deceiving the people. Shepherds who are slaves can only lead barren spirits: an Orthodox priest will never teach is flock anything except to bow to force.

The czarist alliance of Church and State foreshadowed the Communist system in two crucial respects. The Communist state, like the czarist state, created a kept class of intellectual apologists to inculcate its rigid dogma; instead of priests, these were the Party theoreticians, lecturers, professors, journalists, and writers. And while the Communists initially waged war against all forms of religion, it did not take them long before they restored the priests of the Orthodox Church to the government's payroll and the government's service.

Russian style of governance has always been based on deceit and blatant lying. Honesty is considered as a special kind of stupidity. There are three words for “lie” in Russian language: lozh, which is a blatant lie, vranyo, which is tactical lying, and nepravda, which is untruth. There are two words for truth: pravda, which is subjective truth on behalf of the narrator, and istina, which is scientific truth. Everything is subjective and relative, and for the Russians, things may be true or not whether one decides to believe or not.

Such society creates deep distrust and paranoia. The American flat earthers and anti-vaxxers are nothing compared to the Russians and their distrust. When everyone lies and cheats, and you cannot trust on anyone or anything, paranoia results.

Russia is extremely jealous to the West, and perpetually seeks conflict with the West just to get a chance to cause havoc and destruction for its own sake. This is why the Russian leaders blame the West for their own problems and blame NATO being a hostile alliance hellbent to destroy the Almighty Derzhava.

A burst pipe in Moscow produces a fountain of raw sewage

But Russia is not the victim; Russia is the predator. ~ Susanna Viljanen, Quora

*

SHOOTING THEIR OWN: A RUSSIAN TRADITION

Russia paid for loyalty with bullets since forever — Soviets shoot not only their own soldiers in WW2, who were trying to retreat. Soviets even shot their own generals captured by Nazis, when they returned.

In August 1941, Soviet generals Ponedelin and Kirillov were captured by Hitler’s troops.

Stalin sentenced the generals to death in absentia, declaring them traitors, despite their refusal to collaborate with the Nazis.

After their release from the concentration camp in April 1945, the generals rejected the U.S. offer to move to America — and returned to their homeland, where they were executed on the same day.

My grandfather, too, was captured by Germans in WW2. After he managed to survive for nearly 4 years in a concentration camp, he was freed and returned to the Soviet Union, where he was declared a traitor and sent to a Siberian GULAG.

He was conditionally released only after Stalin’s death in 1953 — but he still had to live for 2 years at the same “in the middle of nowhere” place where he was imprisoned, only in the village nearby. He couldn’t return to his wife and 4 kids who were waiting for him in a village on Volga River for 12 years — 4 years of Nazi captivity and then 8 years of Stalin’s GULAG.

Russia is shooting their own soldiers because it had been ruled through cruelty and fear for over 100 years.

“Do as we say or you are dead,” is the order not only to the enemies, but to their own people as well.

And the only possible way out of it is for Russia to lose big and repent.~ Elena Gold, Quora

Mark Kempson:

This is sad, but you are saying the country needs to be "deconstructed", in order to be put back together in a more meaningful and benevolent way for the future. I still believe with all of those natural resources, Russia could be a good place to live and raise a family. There is no reason, (with the right government) that they cannot live lives like their Nordic neighboors, in prosperity and harmony. I hope so, anyway. I have some fond memories of my time visiting Russia back in the 1980s

Elena Gold:

I think for Russian people to be free, the Russian Federation must cease to exist.

“Make Russia small again”

Steve Barlow:

Interestingly, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn documented the maltreatment of Soviet Veterans by the USSR, particularly while Stalin was alive. According to Solzhenitsyn, it was not only the POWs who were abused, Stalin feared that anyone who had been in Germany or interacted the western allies was tainted.

Elena Gold:

Yes, the civilian prisoners as well. Including stolen Soviet kids.

*

A HISTORICAL NOTE: STALINGRAD

In the winter of 1942/43, Hitler sacrificed twenty-two divisions through his command to hold out at Stalingrad. More than 100,000 German soldiers fell, froze, or starved to death even before the surrender of the Sixth Army. Over 90,000 men ended up in Soviet prisoner-of-war camps—only around 6,000 of them survived.

https://www.gdw-berlin.de/en/offers/exhibitions/exhibition/view-aus/deutschland-muss-leben-deshalb-mu/

*

IS “FORGIVE AND FORGET” THE BEST POLICY?

Reckoning with a painful history or forgetting and ‘moving on’ is a familiar conundrum for many countries. Those choosing reckoning might prosecute former leaders, organize a truth commission and issue reparations. Argentina, Germany and South Africa have each chosen this path.

Forgetting offers less clarity. More often than not, it means doing nothing, as was the case in Russia after the collapse of communism or the United States after the abolition of slavery. But it can also mean adopting policies that actively promote political amnesia, as in Spain. Following the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, Spain’s political parties voluntarily agreed to a ‘pact to forget’, the Pacto del Olvido.

The pact extended a blanket amnesty to anyone associated with Franco’s reign of terror, especially the so-called ‘Spanish Holocaust’, a campaign intended to eradicate left-wing dissidents following the end of the civil war in 1939. It also ruled out policies that would rekindle the memory of the war, such as erecting memorials to its victims, observing war-related anniversaries and using the events of the war to attack political opponents.

Despite its obvious problems, the Pacto del Olvido contributed to the making of Spanish democracy. It allowed for the construction of a new political system unencumbered by painful debates over who was to blame for the war. This is no small achievement for a country that, before 1978, had never experienced stable democratic rule.

The 2007 Law of Historical Memory ended the Pacto del Olvido. While upholding the amnesty of the democratic transition, the law condemned the Franco regime, offered reparations, ordered the removal of monuments honoring Franco and created a national center for the study of the civil war. A subsequent law opened the way for the exhumation and removal of Franco’s remains from state property.

Spain’s experience suggests that forgetting need not mean condemning the past to eternal oblivion, but rather setting it aside until society is ready to deal with it. It also reveals that, contrary to received wisdom, a democratic transition can succeed without reckoning with the past.

GERMANY BEGAN TURNING ITS ENTIRE PUBLIC LANDSCAPE INTO A HISTORY LESSON

You cannot walk down the street in Berlin without stumbling across the past. It is in the concrete slabs of the Holocaust Memorial, in the hollow emptiness of the bombed-out church on the Kurfürstendamm and even in the shiny modern buildings that have risen confidently from the ruins of the war, symbols of Germany’s reconstruction. Germany has chosen not to forget. But it wasn’t always this way.

After 1945 many Germans embraced a kind of collective amnesia. The nation wanted to ‘draw a line under’ the atrocities of the war and rebuild. 1945 was the ‘zero hour’ – a chance to start again. The Nazis’ victims were a taboo subject. But, with time, this attempt to forget began to fray. In the 1960s there were trials of Auschwitz guards and student protests against lingering fascist tendencies in West German society.

The whole country watched aghast when the American television show Holocaust was broadcast in 1979 – a moment that triggered national reflection. By 1985 West Germany’s president Richard von Weizsäcker could declare that the nation would never forget. Remembering the Nazi past became a national obligation.

Enter Vergangenheitsbewältigung – an unwieldy term for the exhaustive process of ‘coming to terms with the past’. Germany began turning its public landscape into a history lesson. Memory was institutionalized through school trips, memorials, exhibitions and strict laws against Holocaust denial.

But does all this remembering prevent history from repeating itself? The rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), a far-right political party that dismisses the Nazi era as a speck of dirt on an otherwise pristine history, suggests otherwise. With its calls to end a ‘cult of guilt’, the AfD has become one of the largest parties in Germany over the past ten years. They say there’s been enough remembering, that it’s time to move on. And they’ve found a receptive audience.

Forgetting comes at a price: the gradual erosion of the moral lessons that history has taught us. While memory alone may not have stopped the rise of the AfD, abandoning that memory altogether could pave the way for more dangerous currents of revisionism and denial. The alternative for Germany? We’ve seen where that path leads already.

*

TRUMP AND HITLER

Donald Trump’s response to being described as a Hitler-loving fascist by his former White House chief of staff was a characteristic one: to call the accuser–a decorated retired Marine Corps general–a “lowlife.”

Trump, in a Truth Social post Wednesday night, lashed out at Kelly, whom he claimed was motivated to share damning details about his time with him due to “Trump Derangement Syndrome Hatred.”

“This guy had two qualities, which don’t work well together. He was tough and dumb,” Trump wrote, in yet another instance of him smearing someone he had appointed to a role in his administration. “The problem is his toughness morphed into weakness, because he became JELLO with time!”

Trump also denied that he called American troops killed in action “suckers” and “losers”—something that Kelly, whose elder son was killed in Afghanistan in 2010, confirmed last year.

“John Kelly is a LOWLIFE, and a bad General, whose advice in the White House I no longer sought, and told him to MOVE ON!“ Trump continued. ”His wife once told me, at Camp David, John admires you tremendously, and when he leaves the Military, he will only speak well of you. I said, Thank you!”

Kelly, in an interview with The New York Times on Tuesday, said Trump praised Adolf Hitler while president, and warned that he would rule like a dictator if elected again.

“Certainly the former president is in the far-right area, he‘s certainly an authoritarian, admires people who are dictators—he has said that. So he certainly falls into the general definition of fascist, for sure,” said Kelly, who spent 18 months as Trump’s chief of staff. “He certainly prefers the dictator approach to government.”

Mark Milley, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Trump, has likewise described the Republican candidate as “a total fascist.”

https://www.thedailybeast.com/trump-rages-at-lowlife-john-kelly-after-hitler-controversy/

Oriana:

But AfD is not obsessed with the past. It's trying ao prevent an unacceptable future:

*

POLAR DINOSAURS

Polar dinosaurs would have witnessed regular displays of Aurora Borealis

It was the middle of winter under a moody Alaskan sky. On one side stretched the flat expanse of the Colville River. On the other, a soaring cliff face of frozen pewter-grey rock, backing onto hundreds of miles of desolate tundra.

Armed with an ice-axe and crampons, buffeted by frigid Arctic winds in temperatures that hovered around -28C (-20F), Pat Druckenmiller was searching for something special.

It was 2021 and just getting to the cliff had been an extreme expedition. In this remote northerly corner of Alaska, there are no roads, so the palaeontologist and colleagues from the University of Alaska traveled to the site on snow scooters, then set up a camp nearby. It was so cold, each tent was equipped with its own wood-burning stove. For the coming weeks, the team would be constantly battling frostbite — "we had some close calls," says Druckenmiller — rockfalls, and hungry polar bears. But it was worth it.

Squinting through ski goggles in the dusky light, Druckenmiller finally found what he was looking for. Buried within the cliff strata, around 50ft (15m) above the river, was a single layer of clay and sand, about 10cm (4in) thick.

Around 73 million years ago, when the sediment was laid down, the world was warmer than it is now, but the region would have been even further north. While today this part of Alaska gets a few hours of twilight each day during the winter, back then it was plunged into total darkness for four months of the year, from October to February. It regularly dipped below -10C (14F), with occasional dustings of snow.

And yet, hidden within this silty seam are the last remains of a bizarre epoch in history – tiny bones and teeth, mere millimeters across, that belonged to the offspring of giants. This is where thousands of dinosaurs made their nests, and the unhatched fetuses that didn't make it are still there to this day.

"It's probably the most interesting layer of dinosaur bones in the entire state of Alaska," says Druckenmiller. "They were practically living at the North Pole.”

Nanuqsaurus eggs; Nauqsaurus weighed about as much as two large male polar bears

Though we tend to think of dinosaurs as tropical creatures – monstrous, toothy reptiles that patrolled the world's forests and swamps when the planet was warm and wet, scientists are increasingly realizing that this is not entirely correct. There were dinosaurs in cooler places too, and it's becoming clear that they were far from occasional, fair-weather visitors.

From Australia to Russia, scientists have now unearthed tens of dinosaurs that may have once lived at frigid extremes – closing their beady, hawk-like eyes under skies filled with dancing aurora light displays each night, and sometimes foraging for food among blankets of pristine silver snow. These dinosaurs weren't just clinging on in at the fringes of their habitable range – in places like Alaska, they were thriving.

The findings have implications far beyond the strange scenes they conjure – with tyrannosaurs shaking the snow off their (possible) feathers, or fluffing themselves up to wait out a blizzard. With each new discovery, polar dinosaurs are revealing fascinating insights into the group's physiology and behavior. And as scientists learn more about them, they're helping to answer one of the most intractable questions in palaeontology: were dinosaurs warm or cold-blooded?

A surprise discovery

In 1961, Robert Liscomb was mapping the banks of the Colville River for the oil company Shell, when he found something unexpected: a handful of bones, sticking out of the strata of the cliff. He assumed they must be from mammals, but took them with him anyway and put them in a cupboard. The same year, he was tragically killed in a rockfall.

For two decades, the bones were forgotten, safely locked away in storage at the company's archives. Meanwhile, scatterings of dinosaur fossils began emerging in other northerly locations, including footprints on the Norwegian island of Svalbard.

Then one day, in 1984, there was an exciting discovery: scientists had uncovered skin impressions and footprints from dinosaurs along the very same northern slope of the Colville River where Liscomb found his. With this in mind, the old bones were rapidly retrieved from their drawer – and revealed to have belonged to dinosaurs all along. This ignited a fierce debate among palaeontologists. Surely there couldn't really have been cold-blooded animals this far north? Century-old assumptions were being called into question, and things were getting heated.

But before long, it became clear that the Colville River bones had been no fluke – the outcrops along its banks were positively teeming with dinosaur fossils, more than had been found at any other Arctic or Antarctic location on the planet. "And most importantly, it's far and away the most polar dinosaur site," says Druckenmiller.

As the finds added up, eventually the evidence became overwhelming. Even in those early days, there were abundant fossils from the cow-like herbivore Edmontosaurus and an unidentified relative of Triceratops, as well as a single tooth from the predator Alectrosaurus – a tyrannosaur about the size of the average walrus.

There had indeed been polar dinosaurs, though how they survived remained to be understood. Luckily there was an easy explanation: they only lived there when it was warm – they migrated. Just like their distant cousins, modern-day Arctic terns, the animals may have visited the poles during the summer, then retreated to warmer climates during the winter. Some experts suggested that they traveled up to 3,200km (1,988 miles).

Then this theory also hit a snag.

On a cool summer's day in the Late Cretaceous, a mega-herd of hadrosaurs crossed a muddy floodplain in the Arctic. It was around 10-12C (50-54F), and the cow-like herbivores – equipped with toothless beaks for grinding vegetation and massive, fleshy tails – had just survived a harsh winter in which temperatures dipped to almost freezing. There were thousands of individuals of all ages – juveniles, teenagers and adults.

Their promenade across the mud may only have lasted minutes, but the tracks they left were soon covered with further sediment, and preserved for the coming millennia – until they were found by scientists in 2014. The footprints were so well preserved, it was even possible to make out the scales on the dinosaurs' feet.

The fossils were located in an Alaskan nature reserve, hundreds of miles further south than the Colville bone beds, but still within the Arctic. The presence of tracks from young dinosaurs hinted that they probably remained in the region year-round after all – the smallest ones would not have been able to cope with a long migration.

However, not everyone was convinced. Enter Druckenmiller and his painstakingly located band of rock.

A tricky task

While some palaeontologists were digging up thigh bones the size of dolphins in the sun-baked Badlands of South America, Druckenmiller's approach was necessarily different.

When the team first started working on the Coleville River site in Alaska, they would visit in the summer, when today it's around 1-10C (34-50F). They quickly discovered that this was far from ideal. Between June and August, Alaska is swarming with mosquitoes – giant clouds that bear down upon unsuspecting humans like blizzards of black snow. There are so many, they're playfully referred to as the Alaska state bird. But this was the least of their worries.

The cliff faces they worked on were mostly composed of muddy rock loosely glued together by permafrost. "And there's just enough warming in the summer for some of that ice to melt so these cliffs can catastrophically just collapse. If you're standing under one of those, it's game over," says Druckenmiller.

The scientists decided to go in the winter instead, which presented its own problems. They were working just 20 miles (32km) from the Arctic Ocean – it was simply too cold to lie on their stomachs all day while sifting out the bones of baby dinosaurs. Instead, soon after the team had found their long-anticipated rock layer, the silence of the empty landscape was promptly broken with the sound of chainsaws and jackhammers.

First the team cut some steps into the cliff so they could traverse it, then set to work carving out whole blocks of promising-looking sediment, rather than specific bones. These were loaded onto sleds and snowmobiles, and driven back hundreds of miles across the frozen tundra to the laboratory.

Once these massive samples were safely at the University of Alaska, they were washed to screen out the clay. "And then what's left is basically like a sand fraction – we look at every single grain of sand under a microscope for little bones and teeth," says Druckenmiller, "This is a very slow, time-consuming process. It's kind of just like panning for gold except for dinosaurs instead." Over the course of a decade, he estimates that his team has looked at millions of sand particles in the search for these tiny fossils.

What the team found was extraordinary. "We didn't have just one or two kinds of baby dinosaurs, we actually have evidence for seven different groups of dinosaurs, including plant-eaters and meat-eaters, small species and large species," says Druckenmiller.

Importantly, the fact that the dinosaurs were nesting means they almost certainly weren't migrating away when it got colder. Some common species of dinosaurs, such as the duck-billed hadrosaurs, needed six months to incubate their eggs – so if the mothers started sitting on them in the spring, it would be almost winter by the time they hatched. To nest in the Arctic but avoid the winter with its months of darkness, these babies would have had to somehow immediately migrate thousands of miles. There just wasn't enough time. "It defies logic. We're pretty sure that these dinosaurs were year-round residents," says Druckenmiller.

So what would life have been like for these polar dinosaurs? And how did they manage to survive?

An icy mystery

It was early March in the Late Cretaceous, at the open Arctic woodland that would eventually become the site of the Colville River. The bare branches of conifers and ancient gingko trees were just coming into bud, casting dappled shade over an understorey of ferns and horsetails below. Herds of hadrosaurs browsed absent-mindedly on the foliage, while male Pachyrhinosaurus, stocky relatives of triceratops, paraded their extravagant neck frills in the hope of attracting a mate – perhaps snorting occasionally through their long, bulbous noses.

Occasionally the relative calm might be punctuated with a chase and a squawk – a hungry Nanuqsaurus, or "polar bear lizard", had managed to catch a scaly, beaky Thescelosaurus in its jaws. With blood dripping down the soft coat of snow-white feathers it's sometimes depicted with, it could have looked remarkably like its modern namesake.

Nearby were a number of nests – possibly at communal nurseries, if the dinosaurs were like their southerly relatives – where the local residents incubated their eggs. Bird-like relatives of velociraptors, saurornitholestines, settled themselves over their broods and may have used their specialised teeth to preen their feathers.

Over decades or hundreds of years, some of the dinosaurs that died in the area ended up being washed into a nearby river or lake. "But the sediment was winnowed away in such a way as to concentrate these bones and teeth into these little discrete deposits," says Druckenmiller.

A number of the dinosaurs identified in silt from sites along the Colville River have been found nowhere else, such as Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis, "ancient grazer" in the local Inupiat language – a kind of hadrosaur.

Of course, this doesn't mean they won't be eventually, and it doesn't necessarily prove that they had any special adaptations to the cold either. But it's promising.

Druckenmiller thinks it's likely that the Alaskan dinosaurs had at least some distinguishing features, such as behaviors that evolved to help them cope in Arctic conditions. "There's reason to believe that maybe some of the smaller species, especially the plant-eaters, maybe some of these were small enough to make a burrow and hibernate over the winter," he says.

These tentative hints come from growth rings in cross sections of bone, like those in tree trunks – markings that show how the animal's growth pattern varied from year to year. If growth stops, such as during hibernation, the gap leaves a ring. According to Druckenmiller, these distinctive bands have been found in several dinosaurs from the slopes of the Colville River, some of which may have hibernated. This adds to the evidence from elsewhere that dinosaurs may have had at least some of the adaptations required, such as burrowing.

In 2007, the fossilized skeleton of an Oryctodromeus – a dinosaur around the size of a German shepherd — was found alongside two of its young in a cozy little hole in south-west Montana. The whole lot had become entombed and lain there undisturbed for around 100 million years. They're part of the Thescelosaurus genus, members of which have also been found at the Colville River site.

"And the fact that we have close relatives in Alaska suggests that it could be that these species also burrow but to hibernate," says Druckenmiller. Unfortunately, proving this would be extremely difficult, short of finding another burrow in the Arctic.

Nanuqsaurus

Another possibility is that dinosaurs coped with the cold much like many modern-day mammals do, by building up a layer of body fat. Druckenmiller gives the example of moose and caribou, which pile on the weight each summer, then survive on a combination of their fat reserves and low-quality forage in the winter when food is sparse – a strategy which has the added bonus of keeping them warm. "…they do it by basically slowly starving," he says. "There's no reason why dinosaurs couldn't have done that."

But there is one adaptation that is more clear-cut: how dinosaurs regulated their body temperature.

Scientists have been debating whether dinosaurs were warm or cold-blooded ever since they were discovered. In the 19th Century, it was widely assumed that they were essentially massive, ectothermic reptiles – they couldn't generate their own body heat, and needed to sunbathe like modern ones. When the iconic Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures were unveiled in London in 1854, they resembled stocky, scaly lizards.

But as experts learned more about dinosaur lives – and began to realize that modern birds are essentially beaky, feathered dinosaurs – many began to question whether this was accurate. Eventually they formed a consensus that dinosaurs probably maintained temperatures somewhere between reptiles and birds, and yet until recently, hard evidence was still somewhat lacking.

Arctic dinosaurs change all this. "One of the things we assume in this whole story is these dinosaurs were almost certainly warm-blooded, to some extent," says Druckenmiller. "Certainly these dinosaurs had some degree of endothermy – they were producing their own internal heat. And that's kind of a prerequisite for living in a cold environment.”

Strikingly, no fossilized remains of reptiles have ever been found in the Alaskan fossil beds – only birds, mammals and dinosaurs. "Now if you work in Montana, and you're looking for dinosaurs, along the way, you're going to find crocodilians, turtles, lizards… we have never ever found a scrap of any of those cold-blooded groups," says Druckenmiller.

Not all dinosaurs were necessarily warm-blooded, of course. There's evidence that their body temperatures may have varied by as much as 17C (31F) depending on the group, from as little as 29C to 46C (115-84F). For comparison, most mammals lie in the range of 36 to 40C (97-104F), while birds are significantly warmer, spanning 41 to 43C (105-109F).

But nevertheless, the implications are huge. Endothermic animals typically share certain characteristics, such as faster growth rates and a requirement for more food. But crucially, it was thought this is what allowed some groups to survive the global cooling historically blamed for the dinosaurs' extinction. If the mammals and birds could handle it, why not the Arctic dinosaurs?

As the evidence for Alaskan dinosaurs began to mount in the 1980s, scientists were already realizing that they might need another explanation. Today it's thought that the real reason most went extinct is their size, which meant they simply required more food than was available. The exception was the "maniraptoran", or "seizing hands" dinosaurs. The smallest, feathered members of this group – those that weighed about a kilogram (2.2lbs) – were able to cling on and adapt. Now we know this lineage as birds.

With each new discovery, these almost-polar dinosaurs are revealing clues to the diversity and resilience of their relatives across the planet – and showing that they were so much more than giant lizards.

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-polar-dinosaurs-revealing-ancient-secrets?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

*

HOW MAMMALS INHERITED THE DINOSAURS’ WORLD

First flying dinosaurs

The asteroid that killed the dinosaurs wiped out the majority of species on Earth – but not mammals.

Sixty-six million years ago, our distant ancestors lived through perhaps the most violent event in Earth's history. How did a band of small, insignificant mammals scuffling in the shadows survive the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs?

Through darkness, ash and deadly heat, a tiny furry animal scurries through the hellscape left behind by the worst day for living things in Earth's history. It picks through the wreckage, snatches an insect to eat, and scuttles back to its shelter. All around it are the dead and dying bodies of the dinosaurs that have terrorized mammals for generations.

These were the early weeks and months after a six-mile-wide (10km) asteroid collided with the coast of present-day Mexico with the force of more than a billion nuclear bombs, ending the Cretaceous spectacularly. At the dawn of the era that followed, the Paleocene, the forests were on fire, tsunamis rocked the coasts, and vast quantities of vaporized rock, ash and dust were rising miles into the atmosphere.