*

FOURTH OF JULY, ATLANTIC CITY BOARDWALK

It was the money night. The gaudy dark

steamed with muggy heat.

The casinos were packed;

eighty-eight-cent stores competed

with the ninety-nine-cent stores.

The fake Gypsy fortune-tellers

tugged back fake Gypsy scarves.

On every block someone was

performing: a raggae band

with dreadlocks bleached to rust,

a kazoo player, a one-man orchestra

pounding on a washboard

with a foot-strung drum.

Then the fireworks, twice:

the family show at nine,

and the midnight extravaganza.

rockets from an off-shore boat

burst into cartwheels, rings and hearts —

even a wobbly peace sign.

The full moon rose from the sea,

orange-pink like a salmon.

When fireworks fizzed their last gasp,

we turned toward the casinos:

Caesar’s Palace lined with giant

statues saluting Caesar, and the gilded,

candy-striped Taj Mahal.

High over the sprawling edifice,

in floodlights shifting across the dark,

spiraled an eddy of seagulls.

More than a hundred seagulls, luminous,

soaring three hundred feet up!

At first I thought they too

were only part of the show —

perhaps trained doves, or a laser

fantasy of flight. But the birds

were too high, and they didn’t

advertise anything.

A passer-by explained,

“They are attracted to the lights.”

I couldn’t stop watching them:

against that circus night, the white

birds, incomprehensible as artists,

high above greed.

Over the garish casino,

seagulls spiraled in shifting beams,

their bodies weightless,

as if made of light.

~ Oriana

My thanks to Charles, who made the trip possible.

*

Mary:

The opening poem is wonderful in its recreation of the dizzying activity

of artificial celebration, the lights, sounds, fireworks, street

entertainers and eager to be entertained crowds.. all outshone by the

epiphany of gulls rising like light into the sky. The reader feels

wonder like a blessing with that image of a hundred gulls eclipsing all

the tawdry carnival gaudiness of the streets.

*

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON

Novelist Robert Louis Stevenson traveled often, and his global wanderings lent themselves well to his brand of fiction. Stevenson developed a desire to write early in life, having no interest in the family business of lighthouse engineering. He was often abroad, usually for health reasons, and his journeys led to some of his early literary works. Publishing his first volume at the age of 28, Stevenson became a literary celebrity during his life when works such as Treasure Island, Kidnapped and Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were released to eager audiences.

*

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850, to Thomas and Margaret Stevenson. Lighthouse design was his father's and his family's profession, and so at the age 17, Stevenson enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering, with the goal of following his father in the family business. Lighthouse design never appealed to Stevenson, though, and he began studying law instead. His spirit of adventure truly began to appear at this stage, and during his summer vacations, he traveled to France to be around young artists, both writers and painters. He emerged from law school in 1875 but did not practice, as, by this point, he felt that his calling was to be a writer.

In 1878, Stevenson saw the publication of his first volume of work, An Inland Voyage; the book provides an account of his trip from Antwerp to northern France, which he made in a canoe via the river Oise. A companion work, Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (1879), continues in the introspective vein of Inland Voyage and also focuses on the voice and character of the narrator, beyond simply telling a tale.

Also from this period are the humorous essays of Virginibus Puerisque and Other Papers (1881), which were originally published from 1876 to 1879 in various magazines, and Stevenson's first book of short fiction, New Arabian Nights (1882). The stories marked the United Kingdom's emergence into the realm of the short story, which had previously been dominated by Russians, Americans and the French. These stories also marked the beginning of Stevenson's adventure fiction, which would come to be his calling card.

*

A turning point in Stevenson's personal life came during this period, when he met the woman who would become his wife, Fanny Osbourne, in September 1876. She was a 36-year-old American who was married (although separated) and had two children. Stevenson and Osbourne began to see each other romantically while she remained in France. In 1878, she divorced her husband, and Stevenson set out to meet her in California (the account of his voyage would later be captured in The Amateur Emigrant). The two married in 1880, and remained together until Stevenson's death in 1894.

After they were married, the Stevensons took a three-week honeymoon at an abandoned silver mine in Napa Valley, California, and it was from this trip that The Silverado Squatters (1883) emerged. Also appearing in the early 1880s were Stevenson's short stories "Thrawn Janet" (1881), "The Treasure of Franchard" (1883) and "Markheim" (1885), the latter two having certain affinities with Treasure Island and Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde (both of which would be published by 1886), respectively.

The 1880s were notable for both Stevenson's declining health (which had never been good) and his prodigious literary output. He suffered from hemorrhaging lungs (likely caused by undiagnosed tuberculosis), and writing was one of the few activities he could do while confined to bed. While in this bedridden state, he wrote some of his most popular fiction, most notably Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886), Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) and The Black Arrow (1888).

The idea for Treasure Island was ignited by a map that Stevenson had drawn for his 12-year-old stepson; Stevenson had conjured a pirate adventure story to accompany the drawing, and it was serialized in the boys' magazine Young Folks from October 1881 to January 1882. When Treasure Island was published in book form in 1883, Stevenson got his first real taste of widespread popularity, and his career as a profitable writer had finally begun. The book was Stevenson's first volume-length fictional work, as well as the first of his writings that would be dubbed "for children." By the end of the 1880s, it was one of the period's most popular and widely read books.The year 1886 saw the publication of what would be another enduring work, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which was an immediate success and helped cement Stevenson's reputation. The work is decidedly of the "adult" classification, as it presents a jarring and horrific exploration of various conflicting traits lurking within a single person. The book went on to international acclaim, inspiring countless stage productions and more than 100 motion pictures.

FINAL YEARS

In June 1888, Stevenson and his family set sail from San Francisco, California, to travel the islands of the Pacific Ocean, stopping for stays at the Hawaiian Islands, where he became good friends with King Kalākaua. In 1889, they arrived in the Samoan islands, where they decided to build a house and settle. The island setting stimulated Stevenson's imagination, and, subsequently, influenced his writing during this time: Several of his later works are about the Pacific isles, including The Wrecker (1892), Island Nights' Entertainments (1893), The Ebb-Tide (1894) and In the South Seas (1896).

Toward the end of his life, Stevenson's South Seas writing included more of the everyday world, and both his nonfiction and fiction became more powerful than his earlier works. These more mature works not only brought Stevenson lasting fame, but they also helped to enhance his status with the literary establishment when his work was re-evaluated in the late 20th century, and his abilities were embraced by critics as much as his storytelling had always been by readers.

Stevenson died of a stroke on December 3, 1894, at his home in Vailima, Samoa. He was buried at the top of Mount Vaea, overlooking the sea.

https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/robert-louis-stevenson

I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel's sake. The great affair is to move.

There is only one difference between a long life and a good dinner: that, in the dinner, the sweets come last.

Oriana:

I beg to differ somewhat about the sweetness of life coming early, rather than nearer the end. True, the very last years of life may be marred by a nasty disease and/or disability. But assuming health and sufficient prosperity, the last two or three decades of life, the proverbial "age of wisdom," may indeed be the time of harvest and enjoyment that we can hardly imagine during the years of struggle. We can at last relax into a state of contentment and greater receptivity to life's pleasures, large and small. The longer I live, the more I love life, even if health "isn't what it used to be."

I think one factor that creates this late contentment is that we manage to learn what is important to us, and, with luck, we concentrate on that, rather than on things that feel like customary but unimportant clutter and ultimately make us unhapppy. People often say that they peruse a multitude of news sites because it is "important" to know what's happening in the world, to be "well informed." But is it? What difference does it make except leave us less time for what is truly important, which might be doing creative work, communing with nature and maintaining friendships.

Mary:

I read Treasure Island when I was quite young, and its characters and adventures fed my imagination like few other stories. I wanted to be a pirate on the high seas with crazy wild men with wonderful names: Long John, Billy Bones, Black Dog, Captain Flint, Old Blind Pew. I wanted to have swashbuckling adventures, sing about "sixteen men on a dead man's chest," and search for treasure. I identified with Jim Hawkins and somehow it didn't matter that I was a girl. I don't know why that didn't have cognitive dissonance for me, but do remember that when we would play we would often take different gendered roles...you didn't have to settle for being Wendy, you could play as Peter or Captain Hook.

*

ARISTOTLE ON MEANING AND HAPPINESS

I sometimes ask my medical students, “What’s the strongest predictor of a long and happy life?” They invariably reply with exercise or diet, and these are of course very important. But the strongest predictor of a long and happy life is in fact a sense of meaning—which is why people deteriorate very quickly once they feel they have lost their purpose.

According to the London-based Institute of Economic Affairs, retirement increases the likelihood of developing depression by about 40 percent, and the likelihood of developing at least one physical condition by about 60 percent. While there may be other factors involved, such as inactivity, boredom, and loneliness, even these are tied to a lack of purpose—it being much harder to get bored or lonely, or even negatively stressed, if one has a clear direction of travel.

So, how to choose a purpose? How to find a meaning?

ENTER ARISTOTLE

In the Nicomachean Ethics (c. 330 BCE), Aristotle searches for the “supreme good for man”—that is, for the best way to lead our life and give it meaning.

For Aristotle, a thing is most readily understood by looking at its end, purpose, or goal (Greek, telos). For example, the purpose of a knife is to cut, and it is by seeing this that one best understands what a knife is; the goal of medicine is good health, and it is by seeing this that one best understands what medicine is, or, at least, ought to be.

If one persists with this, it soon becomes apparent that some goals are subordinate to other goals, which are themselves subordinate to yet other goals. For example, a medical student’s goal may be to qualify as a doctor, but this goal is subordinate to their goal to heal the sick, which is itself subordinate to their goal to make a living by doing something useful. This could go on and on, but unless the medical student has a goal that is an end-in-itself, nothing that they do is actually worth doing.

What, asks Aristotle, is this goal that is an end-in-itself? What, in other words, is the end purpose of everything that we do? The answer, says Aristotle, is happiness:

And of this nature happiness is mostly thought to be, for this we choose always for its own sake, and never with a view to anything further: whereas honor, pleasure, intellect, in fact every excellence we choose for their own sakes, it is true, but we choose them also with a view to happiness, conceiving that through their instrumentality we shall be happy: but no man chooses happiness with a view to them, nor in fact with a view to any other thing whatsoever.

Why did we get up and get dressed this morning? Why do we go to the dentist? Why do we go on a diet? Why am I writing this post? Why are you reading it? Because we want to be happy. Simple as that.

That the meaning of life is happiness (Greek, eudaimonia, "flourishing") may seem moot, but it is something that most of us have forgotten somewhere along the way.

DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN MEANS AND ENDS

Oxford and Cambridge are infamous for their fiendish admission interviews, and one question that is sometimes asked is, “What is the meaning of life?” So, when I help prepare applicants for their interviews, I frequently put this question to them.

When they flounder, as they invariably do, I ask them, “Well, just tell me, why are you here? Why are you sitting here with me, prepping for your interviews, when you could be outside enjoying the sunshine?”

The students reply that they are sitting here with me because they want to do well in their interview … because they want to get into medical school … because they want to become a doctor.

“But why do you want to become a doctor?” I ask, playing devil's advocate. “Why on Earth would you want to put yourself through all that trouble?”

Among all the umming and ahing, the one thing that the students never tell me is the truth, which is, “I am sitting here, putting myself through all this trouble, because I want to be happy, and this is the best way I have found of becoming or remaining so.”

Somewhere along the way out of childhood, the students, even though they are only a tender 17, lost the woods for the trees. With the passing of the years, their short-sightedness will only get worse—unless, of course, they read and remember their Aristotle.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/ataraxia/202406/the-real-reason-we-get-up-in-the-morning

*

THE MANIC DEFENSE

The manic defense is the tendency, when confronted with threatening thoughts and feelings, to distract the conscious mind with a flurry of activity or with the opposite thoughts and feelings.

A paradigm of the manic defense is the person who spends all their time rushing around from one task to the next, unable to tolerate even short stretches of inactivity.

Other examples include the socialite who attends one event after another, the small and dependent boy who charges around declaiming that he is Superman, and the insecure teenager who laughs “like a maniac” at the slightest intimation of sex.

In Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925), one of several ways in which Clarissa Dalloway prevents herself from thinking about her life is by planning needless events and then fussing over their every detail—in the withering words of Woolf, “always giving parties to cover the silence.”

THE ESSENCE OF THE MANIC DEFENSE

The essence of the manic defense is to prevent feelings of despair and helplessness from entering the conscious mind by occupying it with opposite feelings of euphoria, purposeful activity, and omnipotent control.

This might be why people feel driven not only to mark but also celebrate such depressing milestones as entering the workforce (graduation), getting ever older (birthdays, anniversaries, New Year), and even, in more recent times, death and dying (Halloween).

It can be no coincidence that Christmas, originally a pagan solstice festival, is celebrated in the bleak mid-winter, in the shortest and darkest days of the year. Last year, I spent Christmas in New Zealand, where it is summer at that time of year—and people there made much less of a deal of it.

The manic defense may also take on more subtle or covert forms, such as creating a commotion over something trivial; filling every “spare moment” with reading, study, or on the phone to a friend; spending several months preparing for some civic or sporting event; seeking out status or celebrity so as to be a “somebody” rather than a “nobody”; entering into baseless relationships; and even, sometimes, getting married and having children.

WHEN THE MANIC DEFENSE BECOMES A PROBLEM

Everyone uses the manic defense, but some people use it to such an extent that they find it difficult to cope with even short periods of unstructured time such as holidays, weekends, and long-distance travel—which explains why airport shops are so profitable.

Since the advent of smartphones, it can be a struggle to go a few hours, or even the space of a toilet break, without checking our screen. God forbid that we should be left alone, even for five minutes, with our own thoughts.

“To do nothing at all,” observed Oscar Wilde, long before the advent of the smartphone, “is the most difficult thing in the world, the most difficult and the most intellectual.”

People with a strong manic defense are unable to live in the moment, unable to be truly alive. They leave no opportunity in which to integrate their thoughts or process their emotions, that is, no opportunity in which to gather perspective or come to terms with reality.

Because they never let it in, they lose all immunity to despair. And so when it finally hits them, it hits them like a tidal wave. ~ Neel Burton

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/202406/ego-defenses-the-manic-defense

*

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF LATENESS

The advent of the railways in the 19th century forced towns in Great Britain to align themselves with London Time, or Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Some towns held out for longer than others. One town that stood its ground was Oxford, and for a time, the great clock on Tom Tower at Christ Church college featured not one but two minute hands. Still today, if one is about five minutes late in Oxford, one can claim to be 'running on Oxford time’; and Great Tom, the loudest bell in the city, rings out 101 times every night at five past nine to mark the old curfew time for the 101 members of Christ Church.

Of course, no one bears a grudge if you are just five minutes late, which is why the 'Oxford time' excuse is a bit of a joke. To be five minutes late is not really to be late. Late is when people start getting annoyed. They get annoyed because your lateness betrays a lack of respect and consideration for them—and so they get more annoyed, and more quickly if they are (or think they are) your social or hierarchical superiors.

Unless you present a very good excuse for being late, preferably something that is out of your control (e.g. an elephant on the motorway), being late sends out the message, “My time is more valuable than yours”, that is, “I am more important than you”, and perhaps even, “I am doing you a favor by turning up at all”. It is particularly rude to be late to a formal or important occasion such as a wedding or funeral, or one involving many parts and precise timings such as an elaborate dinner party or civic event.

Being late insults others, but it also undermines the person who is late, because it may betray a lack of intelligence, self-knowledge, willpower, or empathy. For instance, it may be that the person who is late has set unrealistic goals and overscheduled his day, or underestimated the time that it takes to travel from one place to another.

But there are also some more perfidious reasons for being late than mere mediocrity. Some involve anger and aggression, and others self-deception. Let’s start with anger and aggression. Angry people who behave with almost exaggerated calm and courtesy might nevertheless express their anger through passive means, that is, through (conscious or unconscious) resistance to meeting the reasonable expectations of others.

Examples of passive-aggressive behavior include creating doubt and confusion; forgetting or omitting significant facts or items; withdrawing usual behaviors such as making a cup of tea, cooking, cleaning, or having sex; shifting blame; and, of course, being late—often on a frequent and unpredictable basis. As the name suggests, passive-aggressive behavior is a means of expressing aggression covertly, and so without incurring the full emotional and social costs of more overt aggression. It does, however, prevent the underlying issue or issues from being identified and resolved, and can lead to a great deal of upset and resentment in the person or people on its receiving end.

Now let’s talk about the second perfidy, self-deception. As we have seen, being late, especially egregiously or repeatedly late, sends out the message, “I am more important than you”. Of course, one can, and often does, send out a message without it being true—indeed, precisely because it isn't true. Thus, a person may be late because he feels inferior or unimportant, and being late is a way for him to impose himself on a situation, attract maximal attention, and even take control of proceedings. You may perhaps have noticed that some people in the habit of being late are also in the habit of making a scene out of it: apologizing profusely, introducing themselves to everyone in turn, moving furniture around, asking for a clean glass, and so on. Needless to say, such behavior far from excludes an element of passive-aggression.

Staying with self-deception, being late could also be a form of resistance, a way of showing one’s disapproval for the purpose of the meeting, or resentment for its probable outcome. In the course of psychotherapy, an analysand is likely to display analogous resistance in the form not only of being late, but also of changing the topic, blanking out, falling asleep, or entirely missing appointments. In the context of psychotherapy, such behaviors suggest that the analysand is close to recalling repressed material but fearful of the consequences.

I ought to point out that being late is not necessarily unhealthy or pathological. Sometimes, being late is your unconscious (intuition) telling you that you don’t want to be there, or that it would be better for you not to be there—for instance, it could be that a meeting (or even a job) is not the best use of your time, or will inevitably work against your own best interests. Note that headaches can serve a similar function—they certainly do for me.

Whenever you are late, you can learn a great deal simply by asking yourself, "Why exactly am I late?" Even if it is ‘only’ because you are too busy, why are you too busy? Often, we keep ourselves as busy as possible so as not to be left alone with our deepest thoughts and feelings, which is, of course, highly counterproductive in the short, medium, and long term. And this is another reason for being late: to avoid being left with no one and nothing but ourselves (thank God for smartphones!).

Finally, I have a little confession to make. In many social situations, I am often exactly eight minutes late. Why? Well, being early is just as rude, if not more so, than being late, while being exactly on time can sometimes catch out your host (I am often caught out by people who are bang on time, which I guess is a form of me being late). On the other hand, being eight minutes late is not perceived as being late, and gives your host just enough time to sit down for a couple of minutes, gather his or her thoughts, and begin to look forward to your arrival.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201406/the-psychology-of-lateness

*

DO IMMIGRANTS COMPETE WITH AMERICAN WORKERS FOR LOW-LEVEL JOBS?

Short answer: No.

Longer answer: My family owns a small dairy farm. We are white, and we have some Americans working for us (and some of them are even white Americans). But we’ve had to lean hard on (legal) immigrants to get the work done. We have tried to hire Americans. It would be much more convenient to hire Americans. But we end up with immigrants three-quarters of the time.

Rather than go with the grouchy “Americans just don’t want to work” I’ll try to break this down into some main points.

1a. Americans won’t work for that pay.

I’m going to speak most about the food industry, because it’s what I know, but: this is not work you get rich on. Most of the jobs even for citizens or legal workers are low-paid. Illegals can be paid even less, and they make up something like 40% of the workforce.

1b. … and no one wants those workers paid more.

And look, when I say no one, I mean you. Yeah, you. The country that’s gone crazy over inflation and grocery store prices this past year or two? What exactly do you think will happen if that 40% of the workforce is getting paid $15 an hour, like they absolutely should be?

Because this is all cheap food. Not just crop pickers and field workers: dairy. Pork. Chicken. Meat packing operations. Restaurant kitchens. All of these and more are absolutely running on the back of underpaid, illegal immigrants. If you can buy it on sale at Kroger, it’s got illegal fingerprints on it.

This isn’t new. It’s been hyper-ramped up by the US industrial-ag complex, which is a whole another rant, but before illegal immigrants it was slaves. And before slaves, it was feudalism. The system that lets us have a city of 8 million people living in 300 square miles, not devoting any of their time to food production, and not starving requires that somewhere, there be a lot of people getting worked to death for peanut wages.

I don’t have a solution for this one (saving Western civilization is probably out of scope for a Quora answer) but I’ve found that the Venn diagram of people bitching about Biden’s inflation and people bitching about “illegals taking our jobs” is quite near a perfect circle, so. Do the math, guys.

2. Americans don’t know how to work hard.

So you know how the military has boot camp? They aren’t doing that for fun. They’re doing that because there’s nothing currently in our education system, our home life, or frankly elsewhere that trains people how to do physical labor and if you don’t have that training, and you try to do physical labor, you will fail. And farms (as well as packing plants, construction sites, and other dirty jobs), unlike the military, don’t have the time or resources to spend ten weeks pounding those basics into people.

And more than not being trained, people just do not get this. I have had to explain to grown adults what sore muscles were, and that no, they didn’t necessitate going to a doctor. I have had applicants who interviewed for a job that specified “must be able to lift 50 pounds and be on your feet all day” that had to stop for breath midway up a flight of stairs.

My brother, out on the farm, now makes people do “walking interviews” where he has them carry a bucket or two while he gives them a “tour” of the dairy. Some just walk out mid-interview. The last American we hired lasted two hours before he made an excuse to get off the farm then stopped answering text messages. Nothing in these people’s lives had prepared them for the reality of how hard “hard work” was, or that it wasn’t going to just take some willpower and a training montage but time, effort, and some serious discomfort to get even passable at physical labor.

I don’t know enough to give a full explanation on why this problem is so much less marked in immigrants, but it is very much so.

3. Americans take a lot for granted.

A decade or so ago, during one of the periodic times of bad feeling towards immigrants, we were doing a construction project. The (white) contractor showed up with one other white guy on the crew; the rest were Hispanic. A day or two into the project, that white guy was gone. My dad mentioned it in passing to the contractor, who shook his head glumly.

“People don’t like it,” he said. “But what am I supposed to do? The Mexicans show up for work on time, clean, and sober, every morning. They never need time off for their court dates. End of the day they clean up their site, they put away their tools, and they’re back again the next morning. What am I supposed to do?”

I really hate to use the word “entitled” because it’s got some connotations these days, and also because I don’t think this is entirely a positive phenomenon — a lot of the time immigrants are being grateful for, frankly, some really shit jobs and shit treatment, and I don’t like that. But the plain truth is Americans, by and large, think that, as Americans, they’re entitled to a certain level of… comfort in their work, for the lack of a better word. And if the job can’t provide that because it’s inherently uncomfortable, there’s a tendency to act as though the job owes them for that. They deserve to just toss the tools down and walk off at the end of the day; didn’t they work hard? It’s the boss’s tools, let the boss worry about it. They deserve to go out drinking that night. Why fuss if they come to work late and hung over? They showed up, didn’t they?

Combined with a blissful and privileged belief that consequences for actions (driving drunk, doing meth, a spot of beating the wife) are for other people, primarily people of color (who rarely suffer under the delusion that the cop who pulls them over will totally understand) — the pay doesn’t matter, frankly. They’re just less desirable workers than people who drive like getting stopped for speeding will get them jailed or deported, who expect to get fired for showing up late or showing disrespect, who work like their family’s future depends on it.

Are all Americans terrible workers? Of course not. Are all immigrants great ones? Obviously, no. But the median for both means that we’ve found a distinct hierarchy of hires, with immigrants at the top, non-white Americans second, and white Americans a dubious, sometimes risky third. Add in the ingrained need for cheap labor in our current system, and you start to see how we got to where we are.

So no. In my experience, Americans don’t compete with immigrants for low-level jobs, because those jobs pay poorly and most Americans are physically and psychologically unsuited to them.

It’s not a good system, and it’s not a stable system. But going after the immigrants for it is like cutting off your toes to cure your lung cancer. All you’ve achieved is finding a faster, uglier way to die. ~ Kat Feete, Quora

Andy W.:

Well-put. Especially the part about the Hispanic laborers (we have more Dominicans and Hondurans than Mexicans) showing up regularly, on time, and sober.

TonyN:

They work hard because they have to — because they know they are illegal and can be exploited — reported at the drop of a hat.

Kathryn:

The vast majority of *legal* immigrants, no matter where they come from or to where they immigrate, work hard.

Because immigrants, by their very nature, are highly motivated, determined, perseverant, industrious people. They wouldn't immigrate anywhere if they weren’t.

I'm a legal immigrant to the US. I'm a child of immigrants to Canada. I grew up in one of the most diverse cities on the planet, where about 50% of the population are immigrants. I'm a volunteer ESL teacher, something I've enjoyed for years. I'm pretty familiar with the (legal) immigrant experience. Thanks!

Adge:

That is a really good comment. And the US isn't the only country where this is true. Malaysia is also facing this kind of problem, with many "dirty, dangerous and difficult" jobs being done by migrant workers (not all of them legally in the country), primarily from Indonesia, India. Bangladesh, Myanmar and Nepal.

Andrew Olson:

Very well said. I am one of those white people who can do that kind of work and have.

The other kinds I've found? Marines (and some military who have done more than one tour of duty, but both are almost always from military families) and other people who grew up doing ag labor.

That's it. Amazon has the same problem, except they can't hire illegals.

Why can those people do it and ‘normal’ Americans can’t?

You have to start young. I barely made the cut, but generally they have to be physically working from at the very latest 8-10 years old. So, yes, farm kids, generational military and the like. Kids who grew up with PE being their biggest activity literally cannot do it.

And even then, unless they start from when they can walk, it is extremely rare they can keep working like that much past 40-50. I know I can't do it anymore at 54. Maybe HVAC, electrical or plumbing work, where it isn't constant 10-12 hours on concrete (much less in 100+ degree heat), but I did a stint at Amazon and don't think I could physically do it again.

Let me put it this way. I had two surgeries back to back, one of which left me with incisions over half way around my rib cage.

With a couple of Tylenol, I was driving a manual the next day, complete with drains. No big deal. It was a couple of days after the abdominal surgery because they gave me oxycontin. (Never again!)

The pain level of being cut open was a negligible fraction of the daily pain of my job. I blacked out more than once at work from how much it hurt. That was a ‘normal’ shift. Surgery was trivial.

That's why almost no Americans can do the work.

Oh. The ones who could work at Amazon indefinitely? Almost all from Mexico, the Pacific Islands, and Central/South America. Farm kids.

Oliver Schnee:

Same in Germany, just replace Hispanic with Eastern European and non-white American with Turkish.

Philip:

I suspect also that the white people who would have been able to do the job are able to get better jobs, so frankly you’re comparing the white trash (you mentioned court dates) with a more average to high-quality subset of the Latino population.

Elizabeth Wayland-Seal:

The Land of the Free remains dependent on a “servant class” to function. We had the Irish and the Welsh, then the Germans and Italians, and now the Mexicans and Guatemalans. Through it all, we’ve had all the West Africans we kidnapped and dragged here, whose descendants we “promoted” to the servant class after slavery was abolished.

Our nation was constructed by the Winners — people who were wealthy and/or educated in Great Britain and Spain, or people who “came with nothing” and gained power on the backs of others. No American goes into “service” willingly, and very few kids are rigorously trained to do the lifting, hauling, scrubbing, climbing, hammering, digging and picking required of workers in “menial” jobs. Instead, people with no skills and/or no ambition go into retail and food service — nearly the same shit pay, slightly better shit working conditions, but much less in the way of physical demands (and a higher likelihood of a/c in the summer).

In a sense, we still have this hierarchy between “house slaves” and “field hands” even though we are supposed to be industrialized and technologically advanced. The people picking the apples and the people stacking the apples at the Walmart SuperCenter are probably getting paid roughly the same amount (after taxes and “payroll deductions” and the added costs associated with presenting a professional facade to the public) but the apple pickers are looked down on by the apple stackers, even though they are both occupying the same rung of society.

It’s a crap system and an unfair system but it is a system that is literally thousands of years old and offers WAY too many benefits to the upper echelons of society to fall of its own accord. Unfortunately.

Steve Peterson:

Matches my experience. In high school I was the fastest American picker in the orchard, but on a daily basis I picked, at max, half of what the slowest immigrant picked. (I picked from 7am to 3pm, whereas they picked from sunup to sundown, but they were still much much faster than me.)

Russell King:

I had a friend who ran a restaurant years ago. He said that the types of Americans he had to rely on if immigrants were unavailable were typically lazy, unreliable, often had addiction issues, and in some cases were just plain stupid. Even with a language barrier, the immigrants learned better and were there to work: many would work a shift at his restaurant and then go directly to work a shift at another one.

Philip Klossner:

Excellent answer. It’s as bad in office work, where many of the white Americans I interviewed had never exercised their brains either. No 6-month training program before my first assignment? And so on. Very sad situation.

Lawrence Bloom:

It’s amazing how hard and good these immigrants work. Americans just can’t compete on hard labor. They don’t have the same incentive.

Oriana:

I have been continually amazed at how hard some people are willing to work, often for mediocre wages. But while it’s true, it seems, that those born in Mexico or other Hispanic countries are more likely to be reliable and capable workers, excellent at jobs that require traditional male skills — skills often taught to them by their father, grandfather or uncle at a young age — even there you find the typical variation: some are sheer gold, but some are alcoholics, and some are perpetually late or absent. Those who are truly excellent are in high demand, since they get recommended over and over again. But my guess is that we get the twenty/eighty phenomenon here: twenty percent of the people do eighty percent of the work. (Step into any large office, and you'll see the same; the 20/80 ratio is also known as Pareto's Law.)

Another paradox: when you hear the term “Hispanic culture,” do you think about “strong work ethic”? Or are you more likely to think of the food and music, of fiesta and siesta? Is it perhaps that people who know how to work hard are also the ones who know the art of enjoying life?

The ratio of hard workers is perhaps higher among immigrants because immigrants are not a typical sample of the general population of their home country. They are the more ambitious and courageous sort — listen, it’s not easy to be an immigrant, and ethnic prejudice, though maybe not as vicious as in the past, still exists. It’s not easy to learn a foreign language at a functional level. Some can, some can’t — and many give up, sometimes as soon as the first month, and end up going back home.

Those who would like to go back but can’t often become embittered, and rant about all the things that are wrong with America. They become bitter and irrationally negative, finally complaining about everything. But these “losers” get forgotten, and we are left with the cultural stereotype of of the resilient, industrious, highly motivated and reliable immigrant worker.

Not that this positive stereotype is a bad thing, but let’s not forget that ruthless Darwinian competition has been at work here. Those prone to intense homesickness, those who night after night cry themselves to sleep thinking of the people and places they lost, those sensitive souls who “can’t take it” — “it” being the highly competitive “real” world, with its high rejection rate — those who “don’t know how to sell themselves” — no one’s heart breaks for them, only their own.

As for those who heap contempt on those failed immigrants, I wonder how they would do if dropped in the middle of Germany, for instance, not as a tourist but as someone who desperately needs to get a job or some sort of foothold just to survive. Now guess who’s crying themselves to sleep.

The native-born are sometimes puzzled why people for whom settling in America represents an undeniable improvement in the standard of living are still longing for the”lost paradise” of their homeland. One answer is what psychologists have labeled “the loss of the familiar.” We tend to feel more comfortable with what is familiar — even if the familiar is worse than the new according to some objective criteria. And we will find some rational reason for our emotional reaction. The new food may offer a much greater variety, but it doesn’t feel as fresh and natural. The new friends may be very nice people but the friendships feel shallow for some reason, and so on. What at first seemed new and exciting after a while feels alien and out of kilter with our personalities. You don't understand the local jokes, but laugh with the others to cover up the blankness in your mind. You try to be polite, and end up seeming too formal. Your body language comes across as too much or too little. You stand too close, or too far. You smile too much, or not enough. You don't know when or how to engage in small talk . . . and on and on.

Fortunately, time heals. The unfamiliar becomes the new familiar. Small new pleasures become necessities. “Hotel America” can no longer be called that once you buy your own piece of land. The house that seemed just an address and not a place where we belong over time becomes — surprise! — a real home.

For me a special question was this: if I had stayed in Poland, would I have become a poet? One Polish woman poet gave me a compelling answer: of course you would have become a poet — “but of course as a completely different person.”

I think in Polish I might become a language poet. Polish is endlessly flexible and inventive, marvelously suited to play on words. It also can be very emotionally expressive, yes. But I was too repressed, too intimidated into silence to try to be emotionally expressive in Polish. I could be imagistic, though, when describing nature and the seasons. Anything except myself — that would release not the artist in me, but the depressive with her laments of delusional negativity. But mainly, English gave me enough emotional distance to shed repression and that strangling silencing by the teachings of both state and church.

So yes, I'd probably write, but escape into humor and language games. I would be a "completely different person." Probably married to a near-intellectual equal or above. I'd have one child, and everyone seems to agree that the experience of motherhood changes a woman.

I could imagine myself as a mother in Poland, but not in America, where I saw motherhood as a personal death, an erasure of my intellectual versatility (there, I found a nicer term than "greed").

In more realistic moments, I knew that the location wasn't that important. I would be a compulsive mother, possibly to the child's detriment. As is, I can say,'I have not hurt an innocent being." No poems, though. Writing poetry is much too devouring. And, crucially, it involves having long periods of quiet and solitude.

And that was the end of my fruitless imaginings.

*

HOW THE WESTERN MIND NEARLY TOOK AN EASTERN TURN

In antiquity, Pythagoras was better known as a philosopher than a mathematician. Although he may have introduced it to the West, the theorem that came to bear his name had been discovered centuries earlier by the Babylonians and Indians. His association with this theorem suggests some kind of Eastern connection.

PYTHAGORAS

Pythagoras of Samos (c. 570-c.495 BCE) was a near contemporary of Anaximander and Anaximenes, as well as the Buddha. He might even have met Thales of Miletus—"the first scientist”—who, it is said, advised him to travel to Memphis to take instruction from Egyptian priests.

At the age of 40, Pythagoras left Samos for Croton in southern Italy, where he established a philosophically minded religious community. Unusually for the time, Pythagoras admitted men and women alike. Of the 235 famous Pythagoreans listed by Iamblichus, 17 are women.

The men and women who entered the community’s inner circle were governed by a strict set of ascetic and ethical rules, forsaking personal possessions, assuming a mainly vegetarian diet, and—since words are so often careless and misleading—observing the strictest silence.

In India, at around the same time, the Buddha’s followers were organizing into monasteries. The Buddha delivered many of his discourses in the monastery of Jetavana in Shravasti, which had been donated to him by the banker Anathapindada. Buddhist monks could eat meat if it was offered to them, but only after ensuring that the animal had not been slaughtered on their behalf. At her insistence, the Buddha’s aunt Mahapajapati became the first of many Buddhist nuns.

PARMENIDES

After Pythagoras’ death in c. 495 BCE, the Pythagoreans deified him, and attributed him with a golden thigh and the gift of bilocation (being in two places at once).

In India, the first Upanishads, the Chandogya Upanishad and Great Forest Upanishad, had by then already been written. The central vision of the Upanishads is one of pantheism (all is God), with God hidden in nature “even as the silkworm is hidden in the web of silk he made.” God is Brahman and the part or aspect of Brahman that is in us is Atman. The aim then becomes to achieve the knowledge and unity of Atman and Brahman, which is wisdom, salvation, and liberation (moksha). When Socrates argued for self-knowledge over knowledge, he made the same turn as the Upanishads.

The student of Western philosophy might be reminded of Parmenides (c. 515-c.440 BCE), who was still young when Pythagoras died. In his poem, On Nature, Parmenides contrasted the way of truth to the way of opinion. Through a chain of strict à priori deductive arguments from premises deemed incontrovertible, Parmenides argued that, despite appearances (the Way of Opinion), the universe must consist of a single undifferentiated and indivisible unity, which he called “the One”—comparable, of course, to Brahman.

PLATO

In the Metaphysics, Aristotle says that Plato’s teachings owed much to those of the Pythagoreans; so much, in fact, that Bertrand Russell upheld not Plato but Pythagoras as the most influential of all Western philosophers. Pythagoras’ influence is perhaps most evident in Plato’s mystical approach to the soul and in his emphasis on mathematics, and, more generally, reason and abstract thought, as a secure basis for the practice of philosophy.

Just as Plato (c. 437-c. 348 BCE) leaned upon Heraclitus and his theory of flux (“No one ever steps twice into the same river”) for his conception of the sensible or phenomenal world, so he leaned upon Parmenides for his conception of the intelligible or noumenal world, which he rendered as the ideal, immutable realm of the forms.

Plato’s Phaedo, in which Socrates discusses the immortality of the soul with a pair of Pythagorean philosophers, is essentially an Upanishad in both form and content. Socrates argues that the forms cannot be apprehended by the senses, but only by pure thought, that is, by the mind or soul. Thus, the philosopher seeks in as far as possible to separate soul from body. As death is the complete separation of soul and body, the philosopher aims at death, and can be said to be almost dead.

Although the Phaedo is at the root of Western psychology, philosophy, and theology, it is also deeply Eastern in advocating supreme detachment and ego suppression or disintegration as the route to salvation. Also, death is an illusion … we will be reincarnated … according to our karma. These, however, are not the aspects that the West has retained.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/ataraxia/202406/how-the-western-mind-nearly-took-an-eastern-turn

*

The tomb of Cyrus the Great (c. 550 BCE), located in Pasargadae, Iran, bears an inscription in Old Persian cuneiform. One widely accepted version of the inscription reads: "O man, whoever you are and wherever you come from, for I know you will come, I am Cyrus who founded the Persian Empire. Do not begrudge me this bit of earth that covers my body.”

The humble, almost pitiful tone here makes me think that when the dead body of Alexander the Great was being passed through Persepolis, at his own request the conqueror’s hands were arranged to be palms up, showing that they were empty and he was taking nothing with him.

As my cousin Janusz said, “Death is the only real democracy.”

*

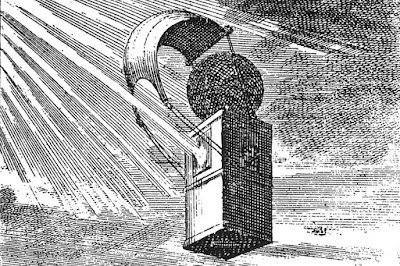

SPACE TRAVEL IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

A flock of swans strapped to a wooden harness, with a smiling, lace-ruffed gallant dangling below: this is spaceflight, circa 1638. More than three hundred years before Apollo 11, the popular pamphlet The Man in the Moone: or A Discourse of a Voyage Thither offered a first-hand account of a lunar landing.

Written anonymously by a bishop of the Church of England, it was presented as a fantasy. Nonetheless, it was inspired by the latest scientific developments. The swan harness, for instance, was drawn from a contemporary theory about migration, viz. Where do the birds all disappear to in the winter? Well, they fly off to the Moon.

In the story, explorer Domingo Gonsales passes through a swarm of demons and finds himself above the clouds. Like an astronaut witnessing the “blue marble,” he sees Earth from the outside.

“[I]t seemed to me no other than a huge mathematical Globe turned round leisurely before me, wherein successively all the Countries of our earthly World were within twenty-four Hours represented to my View,” he observes.

No one, at this time, had ever been in an airplane; no one had seen the Earth’s topography from high above. A map was the only possible reference point.

Landing on the lunar surface, Gonsales falls in with a society of long-lived, peaceable giants. Beautiful and wise, they attire themselves in garments of “moon-color,” a hue that doesn’t exist on Earth, and travel from place to place simply by flicking feather fans.

“You must understand,” our voyager recounts,

the Globe of the Moon has likewise an attractive Power, yet so much weaker than the Earth, that if a Man do but spring upward with all his Strength… he will be able to mount fifty or sixty Foot high… being then above all Attraction from the Moon’s Earth, he falls down no more, but by the help of these Fans, as with Wings, they convey themselves in the Air.

These giants, it emerges, have a policy for keeping their utopian society peaceful: they exile any ill-behaved youngsters to the Earth.

*

Gonsales noted another interesting characteristic of the Moon-giants: they kneeled instinctively at the name of Jesus Christ. In the 1600s, the existence of aliens wasn’t only—or even primarily—a scientific question. It was a religious one.

When Galileo’s early observations of the lunar surface were made public, they kick-started a wave of moon-mania across Europe. A generation of astronomers followed in his footsteps, embroidering over his rough topography; gazing at the cracks and dark patches of the Moon’s face, the reputedly “lynx-eyed” Johannes Hevelius filled them in with a world of marshes, seas, rivers, and islands.

“Our description of the [M]oon is so particular,” writes Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, circa 1686, “that if a learned man was to take a journey there, he would be in no more danger of losing himself than I should in Paris.”

If the Moon had a topography like Earth, people thought, it might very well be inhabited. And, as historian David Cressy writes in “Early Modern Space Travel and the English Man in the Moon,” that raised a number of dangerous questions.

Had God in his plenitude created one world or many? Was humankind the unique focus of divine attention, or were there creatures on other planets enjoying God’s love and suffering his anger? If there were inhabitants on other worlds, were they, like us, the seed of Adam and participants in original sin, and did they benefit from Christ’s atonement and enjoy the prospect of eternal life? Or did Christ die only for us, leaving any other creatures to a kind of limbo or perdition?

In 1638, John Wilkins published The Discovery of a World in the Moone: Or, A Discourse Tending To Prove That ‘Tis Probable There May Be Another Habitable World In That Planet, in which he argued that “a plurality of worlds doth not contradict any principle of reason or faith.” On the specifics, though, he remained circumspect, writing that “whether they [the lunar inhabitants] are the seed of Adam, whether they are there in a blessed estate, or else what meanes there may be for their salvation… I shall willingly omit.”

This caution was not enough to protect him from critique. As Cressy describes, Alexander Ross, a minister of the Church of England, had plenty to say. In his retaliatory pamphlet, The New Planet No Planet; or, The Earth No Wandring Star: Except in the Wandring Heads of Galileans, he argues that Wilkins had “found out that which God never made, to wit, a rolling earth, a standing heaven, and a world in the [M]oon; which indeed are not the works of God, but of your own head.”

Cressy notes that for others, the discovery of outer planets called for a total rethinking of the theological scheme. For instance, in 1638, following the discovery of the rings of Saturn, the Reverend James Usher voiced his melancholy speculations in a private letter, writing

I only say, as upon the discovery of some sumptuous, richly hung house, and all shining with lights and torches, surely that house was not so made and furnished for rats and mice to dwell in… So might the spider, nested in the roof of the Grand Seignior’s Seraglio, say of herself, all that magnificent and stately structure, set out with gold and silver, and embellished with all antiquity and mosaic work, was only built for her to hang up her webs and toil to take flies.

On Earth as it is on heaven; on heaven as it is on Earth.

https://daily.jstor.org/the-seventeenth-century-space-race-for-the-soul/?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

THE EARTH’S INNER CORE HAS SLOWED DOWN AND IS NOW ROTATING BACKWARDS

New research confirms the rotation of Earth's inner core has been slowing down as part of a decades-long pattern. How this slowdown might affect our planet remains an open question.

Deep inside Earth is a solid metal ball that rotates independently of our spinning planet, like a top whirling around inside a bigger top, shrouded in mystery.

This inner core has intrigued researchers since its discovery by Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann in 1936, and how it moves — its rotation speed and direction — has been at the center of a decades-long debate. A growing body of evidence suggests the core’s spin has changed dramatically in recent years, but scientists have remained divided over what exactly is happening — and what it means.

Part of the trouble is that Earth’s deep interior is impossible to observe or sample directly. Seismologists have gleaned information about the inner core’s motion by examining how waves from large earthquakes that ping this area behave. Variations between waves of similar strengths that passed through the core at different times enabled scientists to measure changes in the inner core’s position and calculate its spin.

“Differential rotation of the inner core was proposed as a phenomenon in the 1970s and ’80s, but it wasn’t until the ‘90s that seismological evidence was published,” said Dr. Lauren Waszek, a senior lecturer of physical sciences at James Cook University in Australia.

But researchers argued over how to interpret these findings, “primarily due to the challenge of making detailed observations of the inner core, due to its remoteness and limited available data,” Waszek said. As a result, “studies which followed over the next years and decades disagree on the rate of rotation, and also its direction with respect to the mantle,” she added. Some analyses even proposed that the core didn’t rotate at all.

One promising model proposed in 2023 described an inner core that in the past had spun faster than Earth itself, but was now spinning slower. For a while, the scientists reported, the core’s rotation matched Earth’s spin. Then it slowed even more, until the core was moving backward relative to the fluid layers around it.

At the time, some experts cautioned that more data was needed to bolster this conclusion, and now another team of scientists has delivered compelling new evidence for this hypothesis about the inner core’s rotation rate. Research published June 12 in the journal Nature not only confirms the core slowdown, it supports the 2023 proposal that this core deceleration is part of a decades-long pattern of slowing down and speeding up.

Scientists study the inner core to learn how Earth’s deep interior formed and how activity connects across all the planet’s subsurface layers.

The new findings also confirm that the changes in rotational speed follow a 70-year cycle, said study coauthor Dr. John Vidale, Dean’s Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Southern California’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

“We’ve been arguing about this for 20 years, and I think this nails it,” Vidale said. “I think we’ve ended the debate on whether the inner core moves, and what’s been its pattern for the last couple of decades.”

But not all are convinced that the matter is settled, and how a slowdown of the inner core might affect our planet is still an open question — though some experts say Earth’s magnetic field could come into play.

MAGNETIC ATTRACTION

But not all are convinced that the matter is settled, and how a slowdown of the inner core might affect our planet is still an open question — though some experts say Earth’s magnetic field could come into play.

When scientists attempt to “see” all the way through the planet, they are generally tracking two types of seismic waves: pressure waves, or P waves, and shear waves, or S waves. P waves move through all types of matter; S waves only move through solids or extremely viscous liquids, according to the US Geological Survey.

Seismologists noted in the 1880s that S waves generated by earthquakes didn’t pass all the way through Earth, and so they concluded that Earth’s core was molten. But some P waves, after passing through Earth’s core, emerged in unexpected places — a “shadow zone,” as Lehmann called it — creating anomalies that were impossible to explain. Lehmann was the first to suggest that wayward P waves might be interacting with a solid inner core within the liquid outer core, based on data from a massive earthquake in New Zealand in 1929.

By tracking seismic waves from earthquakes that have passed through the Earth’s inner core along similar paths since 1964, the authors of the 2023 study found that the spin followed a 70-year cycle. By the 1970s, the inner core was spinning a little faster than the planet. It slowed around 2008, and from 2008 to 2023 began moving slightly in reverse, relative to the mantle.

FUTURE CORE SPIN

For the new study, Vidale and his coauthors observed seismic waves produced by earthquakes in the same locations at different times. They found 121 examples of such earthquakes occurring between 1991 and 2023 in the South Sandwich Islands, an archipelago of volcanic islands in the Atlantic Ocean to the east of South America’s southernmost tip. The researchers also looked at core-penetrating shock waves from Soviet nuclear tests conducted between 1971 and 1974.

When the core turns, Vidale said, that affects the arrival time of the wave. Comparing the timing of seismic signals as they touched the core revealed changes in core rotation over time, confirming the 70-year rotation cycle. According to the researchers’ calculations, the core is just about ready to start speeding up again.

Compared with other seismographic studies of the core that measure individual earthquakes as they pass through the core — regardless of when they occur — using only paired earthquakes reduces the amount of usable data, “making the method more challenging,” Waszek said.

However, doing so also enabled scientists to measure changes in the core rotation with greater precision, according to Vidale. If his team’s model is correct, core rotation will start speeding up again in about five to 10 years.

The seismographs also revealed that, during its 70-year cycle, the core’s spin slows and accelerates at different rates, “which is going to need an explanation,” Vidale said. One possibility is that the metal inner core isn’t as solid as expected. If it deforms as it rotates, that could affect the symmetry of its rotational speed, he said.

The team’s calculations also suggest that the core has different rotation rates for forward and backward motion, which adds “an interesting contribution to the discourse,” Waszek said.

But the depth and inaccessibility of the inner core mean that uncertainties remain, she added. As for whether or not the debate about core rotation has truly ended, “we need more data and improved interdisciplinary tools to investigate this further,” Waszek said.

FILLED WITH POTENTIAL

Changes in core spin — though they can be tracked and measured — are all but imperceptible to people on Earth’s surface, Vidale said. When the core spins more slowly, the mantle speeds up. This shift makes Earth rotate faster, and the length of a day shortens. But such rotational shifts translate to mere thousandths of a second in day length, he said.

“In terms of that effect in a person’s lifetime?” he said. “I can’t imagine it means much.”

Scientists study the inner core to learn how Earth’s deep interior formed and how activity connects across all the planet’s subsurface layers. The mysterious region where the liquid outer core envelops the solid inner core is especially interesting, Vidale added. As a place where liquid and solid meet, this boundary is “filled with potential for activity,” as are the core-mantle boundary and the boundary between mantle and crust.

“We might have volcanoes on the inner core boundary, for example, where solid and fluid are meeting and moving,” he said.

Because the spinning of the inner core affects movement in the outer core, inner core rotation is thought to help power Earth’s magnetic field, though more research is required to unravel its precise role. And there is still much to be learned about the inner core’s overall structure, Waszek said.

“Novel and upcoming methodologies will be central to answering the ongoing questions about Earth’s inner core, including that of rotation.”

https://www.cnn.com/2024/07/05/science/earth-inner-core-rotation-slowdown-cycle-scn/index.html#openweb-convo

*

STOP FIGHTING OVER THE SETTING OF THE AIR CONDITIONING

~ Micah Pollak had no idea the trouble he was getting himself into when he shared his preferred thermostat settings on social media. “I just discovered most of our friends set their AC at 68-73F during the summer,” Micah, who is an economist at Indiana University, posted on Threads in late June. “We keep ours at 77-78F. Are we monsters!?” Nearly a thousand replies later, the consensus was that, yes, Micah’s family are monsters, probably some type of lizard.

Although he didn’t realize it, Micah has been following a set of numbers from the Environmental Protection Agency that tends to spark an internet freakout every summer, often after a local news station does a segment on how to reduce your energy consumption and lower your utility bills. The recommendations include keeping your thermostat at 78º when you’re at home during the day, 82º at night, and 85º when you’re away during the warm months.

To many people, sleeping in 82º heat is simply outrageous. (Not to mention terrible for your sleep, according to experts.) But energy prices are crazy too, and they’re only expected to rise as utility companies spend more and more to make the grid more resilient to the effects of climate change. Extreme weather events are becoming more common, and heat waves in particular can strain the power grid, especially when thousands of people are running their ACs at full tilt.

So maybe cranking up your thermostat isn’t such a bad deal. Typically, I’m inclined to set my AC to 72 on a really hot day. If I could get used to a balmy 78º inside, I’d not only save money, I’d be doing my part to keep the grid running smoothly so that everyone can enjoy a little bit of air conditioning, too. And the savings are real. The EPA says that for every degree warmer you set your AC, you can save 6 percent on your cooling costs, although you get diminishing returns as you go higher and higher. Put simply, if your cooling bill is usually $170, setting your thermostat a single digit higher will save you over $10 a month.

There’s one big problem, though. That 78º baseline isn’t a real federal government recommendation. The EPA’s Energy Star program does have a guide for programmable thermostat settings, but it doesn’t recommend a specific number to set your thermostat to in the summer. The numbers that show up in the news actually come from a table in a 2009 document that offered examples of what energy-saving settings could look like.

“Your household temperatures are very much a personal choice, and ultimately people should do what makes them comfortable,” Leslie Jones, a public affairs specialist from Energy Star, told me.

The agency’s official position is that you can save “up to 10 percent on heating and cooling settings by simply turning your thermostat 7°-10°F for 8 hours a day from its normal setting.” In other words, if you keep it at 71 while you’re home, go ahead and set it to 78 if you leave for the day.

Then again, setting your thermostat at 78º at all times is not a monstrous idea. And setting it at 72º probably means you’re wasting some energy.

Nobody wants the government telling them to suffer more in the summer heat. A lot of our assumptions, though, about how air conditioning works, how to optimize the effectiveness of this century-old technology, and how to save energy in the process are just that: assumptions. To clear up the outrage over where we set out thermostats, I talked to experts in thermal comfort, HVAC technology, and the built environment.

It turns out, some of the most effective ways to stay cool are both simple and cheap.

WHY WE FIGHT OVER THE THERMOSTAT

It’s a time-honored American tradition to fight over the thermostat. Winter, summer, spring, and fall, any given home will be too hot or too cold for someone in the family.

This is for good reason, too. Physiologically, we each have our own optimal thermal comfort level. It comes down to a few key factors, according to Boris Kingma, a human thermal performance researcher at the Netherlands Institute of Applied Technology (TNO). The environment, including temperature, humidity, wind, and solar radiation, is obviously the big one. If it’s hot outside, you’ll feel hot. But a person’s metabolic rate and general physiology, including age and overall health, also play a big role — as does the clothing you’re wearing.

Metabolism is what’s at play when you talk to people who say they “run hot.” They might literally do that if they have a high metabolism, which causes your body to produce more heat. People with more muscle mass, for instance, tend to have higher metabolism, retain heat, and prefer cooler temperatures. The opposite goes for people with lower metabolism, who lose heat and might need to wear a sweater in their over-air-conditioned office. Our metabolism decreases with age, which might be why you think your grandparents keep their house too warm.

It is therefore difficult, if not impossible, to find a single thermostat setting that will make all of America happy. Heck, it’s hard enough to agree on anything in a single family. But the good news is that our bodies are very good at acclimating to new environments. Kingma told me that it only takes about 14 days for your body to adjust to a new baseline temperature. So if you’re used to New York City’s relatively mild summer average of 80°F and then move to Miami, where it’s closer to 90°, you’ll probably get used to it.

The same holds for thermostat settings. If you do try and save some money by moving your thermostat one digit up, your body will adjust in a couple weeks, especially if you use a fan and wear lightweight clothing inside. Fans are especially effective, since they move air around your skin, helping sweat evaporate. Loose clothing has the same effect.

“Many of the solutions to this particular problem don’t need to be high tech,” said Kingma. “Dealing with temperature is about as old as humans.”

The role of evaporation cannot be overstated here. Sweating cools us down because the fluid on our skin evaporates and helps us shed heat. This explains why humidity is so miserable: The air is already so saturated with moisture that your sweat doesn’t evaporate effectively, which means you don’t cool down as easily. On windy days or in dry climates — a dry heat, if you will — sweat evaporates more readily, making it easier to stay cool. Fans can help in either scenario.

Focusing on reducing humidity is actually how we got air conditioning in the first place. In 1902, an engineer named Willis Carrier installed an “apparatus for treating air” at a printing company in Brooklyn that was having problems with magazine pages wrinkling in the summer heat. The machine sent air through coils filled with cold water, which removed humidity from the air and cooled the room. It wasn’t until 1922 that the Carrier Air Conditioning Company of America introduced the first practical centrifugal refrigeration compressor that would become the foundation for modern air conditioners.

Most AC units today do the job with three simple steps. They pull warm air out of the room, cool it down by running it over coils filled with refrigerants, and then pump the cold air back into the room while releasing the heat to the outside world by using a compressor, which is why your AC can sound like a starting car. Heat pumps, which can heat and cool a home, operate using the same principles when cooling — more on that in a minute.

Air conditioning is an energy-intensive process, and the refrigerants used in them present a few problems of their own. The most common refrigerants needed to make these machines work include chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HCFCs), commonly known as “freon,” which are greenhouse gasses that deplete the ozone and contribute to climate change. The EPA has been banning many of these chemicals in recent decades to comply with the Montreal Protocol on Substances Depleting the Ozone Layer. However, many modern replacements that do not damage the ozone are still potent greenhouse gasses.

In other words, air conditioning has historically been great for comfort but bad for the climate.

Not only do they require a lot of energy, which may or may not be supplied by fossil fuels, but most air conditioners also pump more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. ACs can keep us cool, but they’ll also warm the planet in the process. It’s a real paradox.

Technologies like heat pumps promise a greener future for heating and cooling, but it will take years to update our HVAC infrastructure due to the cost and sheer scale of trading old, inefficient equipment with new systems. And for many, including renters and certain businesses, those upgrades may even be impossible. So for now, the fight over the thermostat continues.

THE FUTILE EFFORT TO MAKE EVERYONE COMFORTABLE

There is no magical thermostat number to make everyone happy and maximize energy savings. For some, like Micah, the economist, 78º during the day is just fine. For others, 68º is perfect. There have been attempts to solve this problem on an institutional level. And if you’ve ever spent a hot summer day in a large office building, you know that some of those attempts have failed.

The big difference between setting a thermostat at work and at home, of course, is that you typically don’t have any control over the office thermostat. A look at how offices attempt to make everyone comfortable does, however, provide some insight into how we make decisions at home.

First formed as the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air-Conditioning Engineers, ASHRAE sets the industry standards for all things HVAC-related. One specific standard, ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55, provides guidance on how to optimize thermal comfort in the built environment. That includes adapting temperature, humidity, air movement, and thermal radiation in an occupied space to the activity and clothing of the people occupying it. If you’re building a business and want to figure out how to make everyone inside the office comfortable, this is the guide.

ASHRAE, unlike the EPA, specifies an ideal number to set a building’s thermostat to. It’s a range, actually: around 23°-26°C, or 73.4°-78.8°F, in the summer. According to Bjarne Olesen, a former ASHRAE president, “At least 80 percent of men and women are satisfied in that range.” Some might say that the upper end of that range is a bit too warm for good productivity. That assumption would line up with a 2021 review of scientific studies about temperature and work performance, which found the optimal temperature is between 22°-24°C, or 71.6°-75.2°F. But again, the number on the thermostat is not the only thing to consider.

Even fancy office buildings are not immune to energy costs. While the EPA suggests that a single digit, or setpoint, higher on the thermostat can add up to 6 percent savings on your cooling bill, the savings are magnified if you scale them up to an entire building or even an entire city. A 2023 study of three decades of weather and energy cost data concluded that a single setpoint change coupled with behavioral changes could result in 20 percent energy savings. Behavioral changes, which include everything from using fans in addition to AC and wearing lighter clothing, are especially essential in cities, which are designed to depend on air conditioning.

“The technology of cool air allowed people to design buildings that would not normally be comfortable in our environment,” said Robert Bean, a fellow and lecturer at ASHRAE. “And as this environment changes, it puts us in a tough spot.”

There have been some high-profile experiments in thermostat tweaks and energy savings. In 2005, Yuriko Koike, who was Japan’s environment minister at the time, launched an initiative called Cool Biz that pushed government offices to turn their thermostats up to 82ºF from May to September to save energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As an incentive of sorts, workers were allowed to ditch their formal office attire — suits and ties, for instance — in favor of lighter, more casual attire, like aloha shirts and linen pants. There were fashion shows and everything. Big corporations followed the government’s lead, and within a couple years, Cool Biz was a national pastime. By 2023, some 86 percent of workplaces participated in the initiative.

When it comes to energy savings, turning the thermostat up works, too. Estimates vary, but Cool Biz reportedly saves Japan between 1 and 3 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions every year. The program became even more significant in the aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, when reactors across the country shut down and the government mandated further energy savings. They called it Super Cool Biz. There’s even an initiative to turn thermostats down during the winter months. And yes, it is called Warm Biz.

“It’s not rocket science,” said Kingma, the Dutch researcher. “As long as you have the ability to adapt, the problem may be solved by actually adapting.”

Not everybody in Japan loves this, of course. And there is research that shows productivity starts to dip once the temperature rises to 77°F. But Japan’s example shows that an entire nation can adapt to different indoor temperatures for the greater good — and they can look good while they do it. Maybe the rest of the world can, too.

HOW TO STAY COOL AND SAVE THE PLANET

Let me make a confession: I like the thermostat set at 72. If it’s 72 or less outside, I’ll open a window and enjoy the breeze. If it’s warmer, I seal myself into my Brooklyn apartment, let the AC do the work, and wait for nightfall.

Or at least, that’s what I used to do. I actually stopped setting my thermostat at 72 while reporting this story. After my conversations with thermal comfort researchers and HVAC professionals, I realized that cranking up the AC unnecessarily isn’t just a waste of energy, it’s not that comfortable either. It’s silly to get goosebumps inside in the middle of a July day because your cooling machine has cooled the room down too much. That’s why I started to heed the advice of the experts. And let me tell you, these experts are fans of fans.

Stefano Schiavon, a professor at the University of California Berkeley and a member of ASHRAE, told me his colleagues stick with a “fans first” strategy to cooling. “If you feel hot,” he said, “the first thing you turn on is a fan.” You can also use fans to supplement your AC, especially if you’re trying to stay comfortable at a high setpoint. Wearing loose clothing will only add to the cool enjoyment of it all.

“There's been a movement — arguably driven by the air conditioning industry — to say the fan is a technology of the past, we don't want them,” Schiavon explained. “But fans cost much less to manufacture, they use a small fraction of the energy, and they're very intuitive to people so people know how to use them.”

There are also less obvious strategies to stay cool and save energy. Running your dishwasher and doing laundry at night cuts down on bringing excess heat into the home. You can also try spending time in the rooms of your house or apartment furthest from the sun, like on the northern side of the building or in a basement.

Maintenance also plays a big role in making sure everything is running at peak efficiency. That means cleaning your air conditioner vents and changing filters regularly. You should also be sure to keep cool air in and hot air out, so be careful about opening windows and doors unless you’re doing so to ventilate the space.