ANGEL WITH THE SUNDIAL (II)

In the storm that rages round the strong cathedral

like a denier thinking on and on,

your tender smile suddenly engages

our hearts and lifts them up to you.

Smiling angel, sympathetic stone,

your mouth distilled from a hundred mouths:

do you not mark how from your always-full

sundial our hours slide off one by one —

that so impartial sundial, upon which

the day’s whole sum is balanced equally

as though all our hours were rich and ripe?

What do you know, stone-born, of our plight?

And does your face become more blissful still

as you hold the sundial out into the night?

~ Rainer Maria Rilke, tr, J. B. Leishman

(slightly modified by Oriana)

**

Oriana:

I fell in love with this poem at first reading, when I first discovered Rilke in my late twenties — so many years ago that it seems like another lifetime. Unpredictable, the words that may connect one stage of our life with another; timeless ripples in time.

There are so many great lines here, and the poem works so well in English (including the rhymes, often a translator’s downfall — but here we see Leishman at his best) that I am surprised that this exquisite piece from The Book of Images is little known. You’d think that many Rilke lovers could recite the second stanza by heart:

Smiling angel, sympathetic stone,

your mouth distilled from a hundred mouths:

do you not mark how from your always-full

sundial our hours slide off one by one —

The poem flows by itself, each word inevitable, even in translation. But this sublime angel remains largely undiscovered, obscured by its larger, lethal kin perched in the Duino Elegies.

(Rilke thought that those giant angels were Islamic.)

Let’s “take it from the top,” as a quirky (but aren’t they all?) professor of mine used to say. The first stanza is interesting in itself. What is this “storm that rages round the cathedral”? I no longer remember my source for this information, but one explanation may be biographical. When Rilke and Rodin visited Chartres together, Rilke, for whom it was his first visit, was surprised by the wind around the cathedral — “the wind in which we stood like the damned.” Rodin replied that there is always a wind around the great cathedrals. (Oriana: and around skyscrapers; massive buildings change the air flow)

Before we go into the metaphorical meaning of the “storm around the strong cathedral,” let me dispose of a more literal interpretation. The stone walls of medieval cathedrals (which used to double as fortresses in wartime) are massive not only in height, but in thickness. That’s why it’s always cold inside, even on a hot summer day. The turbulence noted by Rilke may have been due to the complicated air currents as the wind pushes against and flows around the giant walls (and oh, how the wind whistles if you open a side door! as if a blizzard were going on . . . )

Also, Rilke might have known the legend of the wind around the Strasbourg cathedral: the wind there waits for the devil (trapped inside god’s fortress) to ride it again. Hence the “denier” might refer to the “spirit that always denies [or “always says No”), a line from Goethe’s Faust.

But let’s assume that the denier refers to an atheist who feels enraged against religion, but rather than express his hatred in a purely emotional outpouring, tries for rational arguments. Though Rilke was influenced by Lou Andreas-Salomé’s belief that all religions were human invention, like Lou he shared a longing for a “real god,” one who does not divide humanity into the saved and the damned.

This “real god” understands our wounds (rather than condemn our “sins”) and accepts everyone. Nothing could separate us from that loving essence of the universe (now if we could only find even the slightest evidence that the “real god” exists . . . )

Rilke felt that it was possible to experience this kind of divine presence, with no need for either rationalized doctrine or blind belief in what we suspect (or even know) isn’t there. Though outwardly hostile toward Catholicism (he forbade the presence of a priest at his funeral), he was drawn to the poetics of Catholicism, the tenderness embodied in Mary and, now and then, other figures — in this case an angel. In spite of the literal as well as emotional and intellectual storm around the cathedral, the angel greets us as a beautiful, loving, and all-accepting being:

your tender smile suddenly engages

our hearts and lifts them up to you

*

I especially love the lines that open the second stanza:

O smiling angel, sympathetic stone,

your mouth distilled from a hundred mouths:

The sculptor made the angel in man’s image. It’s a collective image: “your mouth distilled from a hundred mouths.” An angel is a human self-portrait. But it’s a wishful self-portrait, with wings. That’s how beautiful and serene we’d look if we’d known nothing but affection instead of being screamed at and punished. This is how we’d smile if we knew nothing about abandonment or betrayal. This is how smooth and soft our faces would be if we never experienced stress and suffering (mentally handicapped people sometimes have that soft and smooth look long past childhood — they generally encounter nothing but kindness, since no one judges them; they are granted innocence, so their faces stay unmarked by stress).

The angel, a stone man-bird, cannot know that all our hours are not “rich and ripe.” It can know nothing of the human life, and yet

your tender smile suddenly engages

our hearts and lifts them up to you

That happens thanks to the power of art and the power of a smile, whether on someone’s face or in a painting or on a statue. A smile expresses affection and trust. When we see a smile, we tend to relax and smile back, which automatically makes us feel better.

And then the final irony:

What do you know, stone-born, of our plight?

And does your face become more blissful still

as you hold the sundial out into the night?

The angel is blissful because he is blind and innocent — innocent in the sense of “ignorant.” He doesn’t even know night from day. Alas, we can’t recommend ignorance as a prescription for happiness, though “ignorance is bliss” holds in enough cases to remind me of Esther Perel’s admonition: “Not all truth needs to be told.”

What we can recommend, looking at the angel — and also at the joyfulness of most dogs, for that matter — is that children can be raised without constant judgment and condemnation. I HAVE seen much progress in this area, and a decline in toxic, punitive religion that encourages child abuse. Minimal punishment combined with a lot of affection seems to produce happy, friendly children to whom self-control comes more easily because they aren’t filled with hate and anger. I’ve said this a gazillion times, but I never tire of saying it.

*

WHY “WRITING” REQUIRES ONE T BUT “WRITTEN” REQUIRES TWO

This comes from a medieval spelling reformer, Orm, aka Ormin, an Augustinian canon and grammarian. His name means “Dragon” in the more northern dialect of East Midlands Middle English (very cool!). Orm came up with a method in which you can indicate whether a vowel is long or short by doubling the consonant after it.

(He had a bunch of other spelling laws too regarding doubled vowels, but this is the one applicable to your question. His work that introduces various spelling rules of this sort is called the Ormulum. The Ormulum is mostly fragmentary homiletic work, but it does include asides in which Orm complains about lack of consistency in spelling.)

So, suppose you came across two imaginary English words:

*Xate (with one t)

*Xatt (with two ts)

If I ask you to read both words aloud, you will probably pronounce #1 as “xayte” and make it rhyme with words like “late.” You will probably pronounce #2 as “xaht” or “xat” and either make it rhyme with “bought” or “bat.”

The reason you do that is the same reason you distinguish between hoped and hopped or rated and ratted. You have absorbed the spelling rule that two repeated consonants after a vowel usually indicate the previous vowel is short. If it’s not a doubled consonant (and especially if there’s a silent e on the end), you have absorbed the rule that the previous vowel is long.

English had to create kludgy variations like that because we inherited a very limited number of vowel symbols from the Roman alphabet, but we actually have a lot more vowel sounds in English than the number of letters we inherited.

In the case of write, the word write has an i pronounced as a long vowel. In the case of written, the word written has an i pronounced as a short vowel. It’s exactly the same as the difference between bite and bitten, where the first vowel is pronounced two different ways. ~ Kip Wheeler, Quora

*

ARE WE FOCUSING ON THE WRONG THINGS ABOUT AI?

Conversations about the future of AI are too apocalyptic. Or rather, they focus on the wrong kind of apocalypse.

There is considerable concern of the future of AI, especially as a number of prominent computer scientists have raised, the risks of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—an AI smarter than a human being. They worry that an AGI will lead to mass unemployment or that AI will grow beyond human control—or worse (the movies Terminator and 2001 come to mind).

Discussing these concerns seems important, as does thinking about the much more mundane and immediate threats of misinformation, deep fakes, and proliferation enabled by AI. But this focus on apocalyptic events also robs most of us of our agency. AI becomes a thing we either build or don’t build, and no one outside of a few dozen Silicon Valley executives and top government officials really has any say over.

But the reality is we are already living in the early days of the AI Age, and, at every level of an organization, we need to make some very important decisions about what that actually means. Waiting to make these choices means they will be made for us. It opens us up to many little apocalypses, as jobs and workplaces are disrupted one-by-one in ways that change lives and livelihoods.

We know this is a real threat, because, regardless of any pauses in AI creation, and without any further AI development beyond what is available today, AI is going to impact how we work and learn. We know this for three reasons: First, AI really does seem to supercharge productivity in ways we have never really seen before. An early controlled study in September 2023 showed large-scale improvements at work tasks, as a result of using AI, with time savings of more than 30% and a higher quality output for those using AI. Add to that the near-immaculate test scores achieved by GPT-4, and it is obvious why AI use is already becoming common among students and workers, even if they are keeping it secret.

We also know that AI is going to change how we work and learn because it is affecting a set of workers who never really faced an automation shock before. Multiple studies show the jobs most exposed to AI (and therefore the people whose jobs will make the hardest pivot as a result of AI) are educated and highly paid workers, and the ones with the most creativity in their jobs. The pressure for organizations to take a stand on a technology that affects these workers will be immense, especially as AI-driven productivity gains become widespread. These tools are on their way to becoming deeply integrated into our work environments. Microsoft, for instance, has released Co-Pilot GPT-4 tools for its ubiquitous Office applications, even as Google does the same for its office tools.

As a result, a natural instinct among many managers might be to say “fire people, save money.” But it doesn’t need to be that way—and it shouldn’t be. There are many reasons why companies should not turn efficiency gains into headcount or cost reduction. Companies that figure out how to use their newly productive workforce have the opportunity to dominate those who try to keep their post-AI output the same as their pre-AI output, just with fewer people. Companies that commit to maintaining their workforce will likely have employees as partners, who are happy to teach others about the uses of AI at work, rather than scared workers who hide AI for fear of being replaced. Psychological safety is critical to innovative team success, especially when confronted with rapid change. How companies use this extra efficiency is a choice, and a very consequential one.

There are hints buried in the early studies of AI about a way forward. Workers, while worried about AI, tend to like using it because it removes the most tedious and annoying parts of their job, leaving them with the most interesting tasks. So, even as AI removes some previously valuable tasks from a job, the work that is left can be more meaningful and more high value. But this is not inevitable, so managers and leaders must decide whether and how to commit themselves to reorganizing work around AI in ways that help, rather than hurt, their human workers. They need to ask “what is my vision about how AI makes work better, rather than worse?”

Rather than just being worried about one giant AI apocalypse, we need to worry about the many small catastrophes that AI can bring. Unimaginative or stressed leaders may decide to use these new tools for surveillance and for layoffs. Educators may decide to use AI in ways that leave some students behind. And those are just the obvious problems.

But AI does not need to be catastrophic. Correctly used, AI can create local victories, where previously tedious or useless work becomes productive and empowering. Where students who were left behind can find new paths forward. And where productivity gains lead to growth and innovation.

The thing about a widely applicable technology is that decisions about how it is used are not limited to a small group of people. Many people in organizations will play a role in shaping what AI means for their team, their customers, their students, their environment. But to make those choices matter, serious discussions need to start in many places—and soon. We can’t wait for decisions to be made for us, and the world is advancing too fast to remain passive.

https://time.com/6961559/ethan-mollick-ai-apocalypse-essay/?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

*

WHY BULLYING IN SCHOOLS IS SO COMMON

Schools are children’s prisons. They are basically similar totalitarian institutions like prisons, military, mental institutions or concentration camps. The same basic rules apply there and the human relations in all of them are the same. The same patterns of human relations which are evident in prisons, also exist in schools.

The main reason is heterogeneous materiél. The more heterogenous a body of people is, the more there are also internal conflicts. When an immense number of children with vastly different IQ, coming from different social backgrounds, different attitudes on society and education etc are put together, internal conflicts and competition of dominance and subjugation will emerge. Bullying is basically resolving the pecking order and who gets to beat up whom. This is very much evident also in prisons.

Bullying is rarer in schools where the pupils are more homogeneous by their IQ, social class or attitude on education; it diminishes radically once the mandatory basic education is over, and the Great Centrifuge of Life begins to spin. The pupil materiél in senior secondary schools is vastly more selected and sieved than in the comprehensive schools, and there is no similar competition over dominance or pecking order as in the comprehensive schools. There are also far less conflicts — unless someone is a total jerk, psycho or narcissist.

Low IQ and bullying go hand in hand. This is perhaps best illustrated in the Russian military, where dedovshchina (military brutalization and bullying) is an unresolvable problem (as if someone really wanted to do anything about it). Russia has conscription, but the military is so unpopular that any boys who are able to, dodge the draft. The result is that the military only gets the dumbest, the least talented and the least connected of the cohort — and they are no better than an Orc horde. The pathetic performance of the Russian military in the Ukrainian war is a demonstration of this sad culture.

The same applies to schools. Bullying is most common where the average IQ of the pupils is lowest. And God help if there are kids whose IQ is 30+ points higher — or lower — than the average of the class! Exclusion, ostracism and bullying is certain to emerge.

Jerk jocks are so commonplace it is a trope. Whenever a bully is an athlete, he is without an exception either a hockey jock, footballer, basketballer or similar team sports athlete. The reason is that stupidity condenses in a team. Team sports encourage tribalism, antisocial behavior towards outsiders, dilution of responsibility and mobbing. Ice hockey is the worst: ice hockey has a Pharisean attitude on violence in the rink — officially it is not tolerated, unofficially it is encouraged. The only individual sports jerk jocks are either boxers (simply because the average IQ of boxers is very low) or ski jumpers (because it takes a certain type of personality to jump off the slope and risk one’s life). This kind of behavior is seriously discouraged in true martial arts.

There is also a trope Adults Are Useless — and it has strong connotations in the real life. “Boys will be boys” is a very common excuse, as is “let the kids resolve their own pecking order”. So I cannot suggest anyone experiencing bullying to try seeking adults’ help — it often only exacerbates the situation. ~ Susanna Viljanen, Quora

Mike Bell:

The only thing that seems to fix it is to engage in some retaliatory violence once in a while.

I had to do it in school. Amazingly, the extremely credible threat of a beating unless it stopped “right now”, even from a weak guy like me, was enough to make it stop the one time it happened in high school. In elementary school, it had happened more… and a teacher quietly took me aside and told me that the only solution was to hit them—and he was right. It stopped at that point.

My rather gentle father had a similar experience in school: some idiot kept on bullying him repeatedly… until eventually he lost his cool and cracked the dude’s head into a brick wall. It ended then.

Anyone who has had such experiences, which is to say, the vast majority of people, and still believes in non-violence in any circumstances, is totally deluded, if you ask me. Because never being willing to engage in violence means being a perpetual victim. On the other hand, it’s surprising how a little infrequent violence is enough to keep it well under control.

Frederico Leal:

I feel introversion is far more problematic than IQ. The “bullied nerd” stereotype has some validity, but my impression is that is because a good number of high IQ boys are also introverts. I remember kids who were high IQ and extroverts were not bullied so much, and low IQ introverts got it the worst of all.

Niall Macdonagh:

Now make the school a boarding school where you do not even get to home at the end of the day. This is a clip from the autobiography of a classmate, Nick Hewer.

*

WHAT’S AHEAD FOR RUSSIAN ECONOMY?

Novosibirsk is the hometown of Maxim Geikin, who can now only look at the filthy streets from a billboard. Geikin is one of hundreds of thousands of Russian men sent by Putin to die in Ukraine. All Russia is covered with these posters. And posters to sign up for the army contract.

~ The Russian economy is falling further and further through the cracks, while Putin is spending USD $300 million per day on the war in Ukraine.

new orthodox church near St. Petersburg

The scenery above is indicative of what is going on in Russia: a brand-new church in a “sleeping quarters” suburb of St. Petersburg (called in Russia “the cultural capital”), with typical lack of parking and flooding muddy roads.

That’s the type of environment that an average Russian city dweller experiences every day.

In the near future, Russians will be deprived of foreign goods: Russian leader Vladimir Putin demanded to reduce the share of imported goods in the economy to the levels of the Soviet Union.

Putin wants the share of imported goods and materials to drop to 17% of GDP by 2030. That’s how much the USSR was importing in 1990 — there had never been such a low level of imports in the history of the Russian Federation, since its inception 33 years ago, in 1991.

I still remember the times of the USSR when buying imported goods was a lucky break: clothes and shoes made by Soviet factories were not only ugly but also hugely uncomfortable to wear.

Soviet-era clothing store

Typical assortment of the Soviet clothing store: tweed coats — in spring, summer and winter. I have no idea why this was deemed to be a necessary item to produce and flood all clothing stores.

It’s only that dull and baggy merchandise that was available in Soviet stores: imported goods were sold only at the end of the month, “to make plan” — I’ll explain what it is.

Each store had a “plan” how much money they had to make per month.

If the sales of ugly, dull Soviet clothing didn’t achieve the required amount, the store would be allocated ”deficit” to achieve the planned amount: some imported clothing or shoes of good quality, to be sold on the last day, to just cover the difference to “make the plan” — so that the director and employees weren’t reprimanded by the communist party committee (and could get their bonuses).

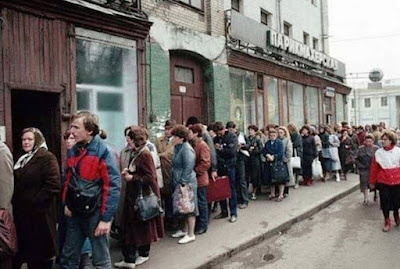

Queue to buy imported shoes in the USSR.

On the last day of the month, the queue of grannies and non-working youth waiting for the sale would form in the morning. No one knew what would be sold, but they knew that something would be “thrown in”.

The sale would usually begin after the lunch break and end when the “deficit” goods were sold out (sometimes even after the working hours).

The rule was: one item per person. You’d be lucky to buy something in your size; most people would buy anything imported that was for sale, and then re-sell to friends or family.

It wasn’t allowed to re-sell goods for profit, but people were doing it, adding 50–200% on top. (That’s why they stood in the queue for hours, waiting for goods.)

Since I was about 13, I was standing in these “last day of the month” queues. I was saving the money that my parents were giving me for lunches, and used the funds to buy “deficit” goods — and then re-sell them in the markets, which were held on Sundays in a small town outside the city (had to take a train to get there).

The income was tremendous, and by the age of 14 I could make more money in a month than my mother was earning; she was the chief of a chemical laboratory at an industrial plant with 5,000 employees. My parents didn’t know what I was doing. (I skipped school to stand in queues.) I used some of the profits to buy fashionable clothes for myself, which I was hiding at home and lied to my parents that I was borrowing the clothes from friends.

What I was doing was highly illegal and risky: selling goods for more than their official state-regulated price was called “speculation” and it was punishable by a prison term.

“Large scale” of the crime of speculation was 2,500 rubles (at the time, the minimum wage in the USSR was 70 rubles per month).

”Regular income stream” would be if the police could establish that you have sold items for profit on a regular basis, or if you were caught for the second time, while trying to sell something for more than the state-assigned price.

Luckily, the crime of “speculation” was removed from the list of punishable violations in 1990. If I kept doing what I was doing, I could end up in jail.

I knew people who served time in prison for “speculation” in goods.

I also met people who were imprisoned for organizing an “illegal business” (sewing fashionable clothing for sale) — this wasn’t allowed; only the state had the right to own a profit-making enterprise; individuals were only allowed to work for hire.

That type of structure is what Putin dreams to restore: the situation where only the state is making money, and any citizen only has the right to work for a state enterprise for a low, survival-only salary, not owning anything except their clothes and bed sheets.

The USSR was a state of quasi-slavery: factory workers were attached to homes by “a registered place of residence”, while peasants didn’t have passports and weren’t allowed to leave villages until 1970s. The state owned all the land and all the buildings; people were allocated small flats to live in, but they didn’t own them.

After decades of mass killings, deportations to Siberia and GULAG labor camps, by 1970s, Soviet quasi-slaves were conditioned to do as they were told and don’t complain.

No dreams of a different life.

No dreams of being free.

Only dreams of an upgrade on the apartment or buying a car (to purchase a car would take years of saving money — with the average wage being 110 rubles per month, a car cost 7,000 rubles).

Slaves never make good workers. Despondent quasi-slaves won’t be doing their best, they won’t dare to venture beyond their prescribed work obligations. No private enterprise; no initiative; no creativity.

Soviet Union lunch hour in a factory canteen

It’s pretty clear that the Russian economy is going downhill, but if Putin has his way (and he had already moved under state control over 180 large companies, and plans to move more), the ability of the industries to remain competitive will be impaired at the very base level.

Will Russia be a top-5 economy in 3 years?

Only in Putin’s dreams. ~ Elena Gold, Quora

Sean Martin:

Considering Russia has used 44% of their liquid assets for the war in Ukraine, another two years of war and the government will be nearly broke.

David Peters:

Thanks Elena for your memories. I lived in Communist China for a while and underneath the surface it was just like this, a drain of humanity and creativity.

Putin is a champion of special interests, his own.

The war makes no sense to a rational person, only one steeped in dogma but there are plenty in Russia willing to believe the dogma. That Ukrainian government is drug addled Nazis, that NATO attacked or were about to attack Russia, that they were protecting Russians living in Ukraine.

Fascists and propagandists are winning in Russia.

Bruce Reitz Irwin

A huge step backwards into anarchy and slavery once again!

And no one cares.

So sad . . .

Star:

It's scary how familiar it sounds. The deficit goods everyone tried to procure, the illegal business — we even created a word for it, bișniță, meaning speculative illegal business. Often if you wanted a book you couldn't just buy it, you had to buy also the unsellable stuff like Ceaușescu's speeches; a package deal. Don't Russians remember their (and our) recent history?

Mark Kempson:

Sad isn’t it? For a nation so rich in natural resources, it need not be this way. They ought to have living standards like their Nordic neighbors.

Barcha S:

It’s just incredible how delusional Putin is, thinking that going back to these times would be an improvement.

For a long time, I thought that Putin perhaps had some masterplan that was behind all his seemingly irrational behavior. But this plan to go back to the Soviet times with little imports, makes me realize he’s just completely lost it.

He’s just batshit crazy.

Paul Vincent:

The Russian government should be waging war on outhouses, not on Ukraine.

*

A CRACK IN PUTIN’S ARMOR

~ On Friday, March 22, gunmen toting assault rifles stormed Crocus City Hall, west of Moscow in the Krasnogorsk district, shot the guards and, as graphic videos show, opened fire on the concert audience without restraint. More than 6,000 tickets had been sold for the performance by the famed Russian rock band Piknik. At least 137 people were killed and many more wounded, some critically; the final death tally could be higher. That even more people were not shot may owe to the perpetrators’ plan to decamp before Russian security forces arrived on the scene. In a move that seemed calculated to maximize the terror, generate publicity, and broadcast the Russian government’s ineptitude, the assailants set parts of the building ablaze. According to some reports, 90 minutes elapsed before Russian special forces arrived. Putin waited until Saturday afternoon before addressing the Russian people in a televised address. By then, an offshoot of the Islamic State, Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K), had already claimed responsibility.

The attack reverberated through Russian society, but also rattled the government, which was caught unaware and unprepared. For Putin, the attack came at a particularly bad time. He had been basking in his recent electoral victory—no surprise, since any candidate with even a slight chance to garner votes of a meaningful magnitude had been declared ineligible to run—and talking up the Russian army’s capture of the Ukrainian town of Avdiivka and its grinding westward advance. Putin has always presented himself as a leader to whom Russians can confidently entrust their safety.

Yet even before the attack by IS-K, that image had been tarnished by Ukrainian drone attacks on more than a dozen of Russia’s 44 oil refineries and incursions into provinces adjacent to the Russia–Ukraine border by anti-Putin insurgents, both of which brought the war into Russian daily life. Furthermore, on March 16, while the Russian presidential election was still underway, Ukrainian missile attacks forced the governor of Belgorod province to order the closing of schools and shopping centers for two days.

But those embarrassments and failures were nothing compared to the Crocus City Hall massacre, the most spectacular attack on Russian territory in nearly twenty years. (The two worst attacks in Russia before this one occurred at a school in Beslan, North Ossetia in 2004 and at Moscow’s Dubrovka Theater in 2002. More than 330 people died in the Beslan attack and at least 130 in Moscow; both were perpetrated by Chechen militants.)

The concert hall attack doesn’t threaten Putin’s hold on power, but it certainly challenges the competent, tough-guy image that has been his stock-in-trade for nearly a quarter of a century. To distract from the state’s security lapse, the Kremlin’s most strident spokespeople lost little time trotting out a time-worn strategy: blaming Ukraine. Margarita Simonyan, director-general of RT, Russia’s state-run television channel, scoffed at the theory that the attack was the handiwork of IS and called it a Ukrainian operation, adding for good measure that Western intelligence agencies had played a “direct” role in it.

The Russian Foreign Ministry’s spokeswoman, Maria Zakharova, reacting to American officials’ statement that Ukraine had played no part in the plot, retorted that such exculpations of Ukraine amounted to evidence of Kyiv’s culpability given that the investigation into the incident had yet to be completed. “The terrorist activities of the Kyiv organized crime group by American liberal democrats,” she declared, had been “going on for many years.”

Well-known media personalities who routinely reinforce the government’s political pronouncements also chimed in to point fingers at Ukraine. One of them, Sergei Markov, said that “the Pentagon” knew about the attack in advance and bore responsibility for the operation, which was organized by “Ukrainian military intelligence.” In the televised statement following the attack, Putin didn’t blame Ukraine’s leaders directly (nor mention IS-K), but he did say that four terrorists had been caught while trying to flee across the Russia-Ukraine border, where “a window was opened for them.” Since then, he has acknowledged the role of “radical Islamists” in the attack but continued to speculate about their true motives. The attack’s perpetrators had a “customer,” he alleged—and who else but the country Russia is at war with?

The Russian government’s key theme has been that the attack underscores the necessity of waging war with Ukraine relentlessly—a rallying cry which, at the very least, amounts to an indirect if transparent effort to implicate its government in the terrorist plot. Ukraine, for its part, was quick to declare the allegations absurd, a desperate attempt to deflect attention from the Russian state’s failures. President Volodymyr Zelensky, for his part, noted that Putin had remained silent for many hours following the shooting.

The extent of the security lapse was made worse by the fact that Russia might have known an attack was coming. On March 7, the American embassy in Moscow issued a terrorism alert warning of possible attacks, including on concerts. But on March 19, three days before the mass shooting at the concert hall, Putin dismissed that warning as “outright blackmail” and a scheme “to intimidate and destabilize our society.” The Russian media has not mentioned this warning.

If the allegations against Ukraine are baseless and we can take IS-K’s claim of responsibility seriously, there are several plausible motives for its attack. To make sense of them, we first need to understand the recent history of the Islamic State.

The Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, which I’ll refer to here as IS, emerged in 2013. A year later, the group announced the creation of a “caliphate,” which covered parts of western Iraq and eastern Syria—a testing ground for a state based on its conception of true Islamic political and social principles. The caliphate came to an end by 2019 as a result of a military campaign by the United States and its local allies, most importantly Syrian Kurdish fighters opposed to the Russian-backed regime of Bashar al-Assad. That same year, IS’s “emir,” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (his nom de guerre), died during an October 2019 American military raid in northwest Syria, reportedly after activating a suicide vest.

The caliphate’s collapse scuttled IS’s most spectacular achievement, but the proto-state’s progressive loss of territory did not stop the movement and its transnational affiliates from conducting terrorist operations, some of which were daring and dramatic. The April 2019 Easter attack in Sri Lanka killed 359 people. In August 2021, as American troops departed Afghanistan, IS conducted a suicide bombing at Kabul airport that claimed at least 170 lives, including those of 13 American military personnel. In the ensuing years, it struck additional targets in Afghanistan as well as in Pakistan and Iran. No attack, though, equaled its slaying of 1,500 or more Iraqi Shia cadets outside the Tikrit Air Academy in 2014.

The IS affiliate that carried out the Moscow attack, IS-K, arose following a 2015 split within the Taliban caused by the belief of some members of its Pakistan wing, the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), that the Taliban’s leaders were not following the principles of Islam, including the sharia code, faithfully. That conviction led them to pledge fealty to IS, and they were joined eventually by like-minded Islamist groups from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan. IS-K’s recruitment and operations have encompassed Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, and Central Asia (parts of which constitute the historic region referred to as “Khorasan”), as well as Russia’s predominantly Muslim North Caucasus region, which includes, among other territories, Chechnya, Dagestan, and Ingushetia. The largest proportion of the thousands of men from various parts of Russia who went to Iraq and Syria to fight alongside the IS hailed from the North Caucasus.

The March 22 attack is not the first conducted by IS and IS-K that has involved the killing of Russians. The others include the October 2015 bomb explosion aboard a Russian airplane flying over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, which killed all 234 occupants; the 2017 bomb explosion on the St. Petersburg metro that killed 14 people; the bombing that same year in a St. Petersburg supermarket that also left 14 dead; the September 2022 suicide bombing at the Russian embassy in Kabul; and a string of attacks in the North Caucasus as well as other parts of Russia between 2015 and 2018.

There are many long-simmering tensions underlying these IS and IS-K attacks. First among them is Russia’s 2015 aerial bombing campaign in Syria. Undertaken to prevent the fall of Bashar al-Assad, an Alawite whom IS regards as a heretic, the campaign killed fighters from many opposition groups, many of whom were IS members. Since then, the movement has proven that it has a long memory—and that it does not lack for vengefulness.

Second is the feud between IS-K and the Taliban, which remains fierce. IS-K has condemned Russia’s dealings with its foe, which it has attacked for “befriending Russians, the murderers of Chechen Muslims” and the killers of Muslims in Syria. The Russian government still classifies the Taliban as a terrorist group but has nonetheless been seeking closer ties, diplomatic and even economic, with Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, especially following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the consequent near-rupture of its relations with the West. IS-K has conducted many terrorist attacks inside Afghanistan, including one in Kandahar the day before it attacked the concert venue in Moscow.

Then there’s Russia’s alignment with Iran, which has become more pronounced as Moscow has turned to Tehran to supply some of the drones, artillery shells, and surface-to-surface missiles it uses in Ukraine. IS, a doctrinaire Sunni movement, has conducted terrorist attacks inside Shia Iran, which it regards as an apostate state, and it stands to reason that the group does not look kindly on Moscow’s bond with Tehran.

Reaching further back, there are Russia’s two brutal wars against Islamist separatists in Chechnya—1994-1996 and 1999-2000—which laid waste to the capital, Grozny, and claimed tens of thousands of lives (according to some estimates as many as 160,000 Chechen combatants and civilians). These wars seem too far removed from the present to have been a prime motive for the attack on Crocus City Hall. But as with the Soviet army’s war in Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, they comport with IS’s persistent depiction of Russia as a country that stands guilty of slaughtering Muslims.

*

The March 22 attack is unlikely to have much effect on Russia’s politics or its war in Ukraine. Putin’s reputation may have been sullied, but most Russians are consumed by grief and shock. Not only does the state control the media, which gives it an enormous capacity to frame the narrative on the attack and to shield the country’s leadership from blame, it also has formidable means of repression and has demonstrated a willingness to use them against dissenters. Many Russians will accept their government’s account of what happened and who’s to blame. Those who won’t will be deterred by the high price paid by people who publicly criticize the authorities, to say nothing of calling for street protests. Those dissidents who might have had the stature to use this security failure to mobilize demonstrations against the government are dead, imprisoned, or in exile.

Meanwhile, the state has moved rapidly to regain public confidence, touting the arrest of four perpetrators and detainment of eleven others. For good measure the security services—perhaps to show that they were now on the case, perhaps assuming that Russians yearned for revenge—released gruesome photos of the suspects after they had been beaten up and tortured.

As for the war in Ukraine, now entering its third year, Putin will continue to do whatever he can, short of using nuclear weapons, to win it. The attack on the concert hall won’t necessarily change his strategy: the combination of continuing to blame Ukraine while targeting its cities and power grid with drones and rockets will still play well with the Russian public, as it has since the invasion started more than two years ago.

Putin will only face a more serious problem if this attack is followed by others: say, continual Ukrainian attacks on Russian energy infrastructure and defense-related industries plus more cross-border attacks from armed insurgents. If the Russian state fails again to discharge the elemental duty of a government—protecting its citizens—the public’s trust in a leader whose appeal derives in no small measure from projecting strength and competence could quickly erode. If, in addition, the war drags on, Putin’s tactic of deflecting blame onto others for security lapses may eventually wear thin. But for the moment, there’s no evidence that he faces dissent within his inner circle or bottom-up disaffection sufficient to produce rebellions.

Substantial gains on the battlefield might help Putin overcome whatever doubts might have arisen about his leadership. In the meantime, though, he’s managed to control the narrative surrounding the attack by pushing the message that it is an occasion for Russians to demonstrate their resilience, compassion, and patriotism. Left unsaid, but well understood by Russians, is that other reactions, especially those that point fingers at the state, will signal a lack of these qualities. Few Russians want to be seen in that light: some because they support Putin, others because they are unwilling to face the consequences of opposing him, still others because they largely ignore politics and immerse themselves in the routines of day-to-day life.

Putin’s political position could change for the worse; however, if the war against Ukraine continues with no apparent end in sight, the already substantial number of dead and wounded, estimated to be about 70,000 and 280,000 respectively, continues to rise, and the state resorts to mass mobilization. The political ground could then shift and catch Putin off guard.

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/a-crack-in-putins-armor/?utm_source=Boston+Review+Email+Subscribers&utm_campaign=79505edde1-ourlatest_4_3_24&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_2cb428c5ad-79505edde1-40729829&mc_cid=79505edde1

*

ANOTHER TAKE ON THE FUTURE OF RUSSIAN ECONOMY: Misha Firer

My friend Nick has sent me photos of the state of the road near his place in Povarovo, a locality just twenty miles from Moscow. He wanted to show Americansky readers who think that Russia’s economy is booming.

He believes there are no road construction funds anymore because war expenditures have drained the budget. He also wondered why Americansky don’t put tires into potholes? Maybe you can answer him better than I did.

If authorities don’t have money to fix potholes in a Moscow suburb, just think what it’s like in the rest of the country.

EDIT: Povarovo administration repaired the potholes two days after the publication of this post.

This predicament is certainly nothing new. Russia has inherited Byzantium’s centralized government, and has remained far less developed than the West for centuries, to this day.

The authoritarianism that liberal democracies have decried is necessary for military command to fight invaders that have historically come from every direction except the Arctic Ocean.

Russian leadership has tried to push borders as far as possible from the capital because they have been paranoid that if they don’t, they would be attacked and conquered, which has become a self-fulfilling prophesy.

For example, a botched invasion of Finland in 1939 to push borders from St. Petersburg, demonstrated unpreparedness of the Red Army and convinced Hitler that the Soviet Union would be a piece of cake.

However, Western leaders keep forgetting to take into account that Russia is structured for military victory at any cost.

The state treats citizens as cannon fodder and command economy permits the national leader to spend every ruble in the coffers to manufacture arms and generals are lauded for high casualty rate in the units under their command to deliver results on the battlefield.

This single-minded pursuit of military objectives time and again bankrupts the state like it happened because of Cold War.

Nowadays, Russia’s elites are once again Westernized and speak Western languages, and pursue Western lifestyle of comfort and luxury, while peasants punch anyone in the face for daring to speak a language of the foes.

A good example is Pyotr Tolstoy, a descendant of the aristocratic novel writer Leo Tolstoy. He’s a politician and deputy chairman of the legislature branch.

He used to work for French daily Le Monde as a Russian correspondent and recently gave an interview to a French blogger speaking in French.

A puzzling idea that circulated in the Western press about how 23 High Mobility Artillery Systems delivered to Ukraine would cause Russia to break up into twenty seven independent nations has caused Kremlin to double down in paranoia and shift economy to the war footing.

Tolstoy in the interview paid back promising that Russia is going to fight in Ukraine until they succeed in breaking up the European Union.

While Pyotr Tolstoy enjoys a bottle of French champagne, he in all seriousness believes that “Vladimir Putin’s Russian model” is morally superior to “the decadent West” and therefore they are gonna win.

Russians have always confused Western decadence with their backwardness and provincial character. But whatever the cultural disagreements, as usual, it’s the peasants who fight Westernized elites’ war, which they are doing now in Ukraine.

Will there be a point when Russian soldiers wake up and realize that they get maimed and die for the French speaking politicians and English speaking oligarchs whose families live in Miami and Paris?

Alas, in Russia, if you are against the state it means you are a traitor pulling for foreign invasion. However, Ukraine didn’t attack Russia, it’s paranoid Russia that invaded Ukraine.

Ordinary people are getting poorer and poorer and the Westernized pompous elites who prey on the concept of family values, country and patriotism are getting richer.

Public safety is degrading with almost daily arsons, terrorism, and shelling of the border regions. Remember that the FSB, political police, wrestled power from the oligarchs on the promise of improving state security.

In 2022, the FSB arrested theater directors Berkovich and Petriychuk and a criminal case was opened against them for justifying terrorism over their play about women who met representatives of the terrorist organization Islamic State (ISIS) on the Internet and decided to go to Syria with them. Both young artists are still in the detention center awaiting trial.

In the meantime, real representatives of the real terrorist organization who staged a real terrorist attack in the concert hall are most likely still at large unless you believe that the four scrawny Tadzhiks from a restaurant kitchen are professionally trained fighters capable of shooting dozens of people in cold blood. Oh my, that restaurant doesn’t look safe to me anymore!

Rampant inflation is wiping out standards of living. The only opportunities to prosper are military service in war zone, producing arms — occupations full of perils of being two-smokered out and HIMARSed, and vast majority of people are falling further and further behind struggling just to make the ends meet.

Another military disaster. Another revolution. ~ M. Firer, Quora

Robert Ottawa:

“Ordinary people are getting poorer and poorer. Westernized pompous elites who prey on the concept of family values, country and patriotism are getting richer.”

That's maybe a reason why Putin doesn't want to end the war in Ukraine. At the end of the war, thousand of battle hardened soldiers will be coming home to watch their families live on pittance while witnessing the opulence of the elite. The resentments will be tremendous.

If the march on Moscow by the Wagner group last year was an indication, it should be clear to Kremlin by now that an army of angry and disillusioned military-trained men is a clear danger to the regime.

Mike Horton:

Russia will collapse on the economic front before it collapses militarily in Ukraine.

Sure Putin has huge support, but the more oppressive the tyrant the faster the support will flip. Once it starts and it may well be this year, it will be measured in days if he is lucky.

Nancy Knight:

I was very interested to read your remarks about the guys arrested for the attack. I watched video of the shooters, and they looked pretty beefy to me, not very skinny like those arrested. The big loser here is Poo-in-a-tin. He’s got egg all over his face from ignoring America’s warning. We have a policy of sharing intelligence like this with other countries, even our adversaries, but of course someone who is a psychopath like Pooty-poot would never believe that.

Patrick Cox:

Interesting point, it was the failed militarism that gave Lenin the opening in 1917. Could Ukraine provide another such opening for some new ‘strong man’?

Robert Beyer:

At least the Russian situation does not seem as bad as what I encountered when I worked for USAID in Tbilisi in the early 2000s, where impoverished people stole the manhole covers to sell for scrap, leaving the hole exposed, which in my neighborhood someone tried to remedy by sticking a log down the hole to give drivers a warning, which was not very effective at night because of blackouts. The regular potholes were so bad that every month or so I had to take my car to a garage to have the wheels re-rounded.

As for Russia's having inherited Byzantium’s practice of centralized control of all government levels, USAID in both Ukraine and Georgia had special programs to develop local government autonomy and responsibility for services, going so far as to pay for garbage trucks for local municipalities to be able to provide sanitation services. The programs were quite popular in both countries with both the local governments and the populace, and resulted in increased citizen involvement in local issues and local elections.

*

UKRAINIAN FORCES KEEP DESTROYING RUSSIAN TANKS

A new important achievement unlocked! 7,000+ Russian tanks have been destroyed since the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

In 2024 alone, Ukrainian warriors destroyed more than 1,000 tanks. Every day, Ukraine makes the Russian invader weaker, but Ukraine still needs more weapons to defeat the aggressor.

*

RUSSIANS EXIST IN THEIR OWN PARALLEL REALITY, WHERE RUSSIA IS THE BEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD.

The Russian world and the Western world are 2 different realities — the war in Ukraine is no longer just the war for the territory. It is the war of the worlds.

With Russia’s speedy regress towards sadistic dictatorship, these 2 worlds simply cannot co-exist anymore. Only 1 world can survive.

Russian leader Vladimir Putin is hellbent on making his reality the only reality.

For Russia to be the best country in the world, all other countries must either live worse — or they should cease to exist.

That’s why Putin invaded Ukraine in February 2022 — he couldn’t allow that another country next door, where people can also speak and understand Russian, will be living better than Russia.

Putin spelled out his desire to destroy the Western world many times — and his propagandists go further, constantly threatening to drop nukes on Europe, Britain and the USA.

By April 2024, the majority of Russians are consumed by their hatred of the West — the amount of hateful anti-West propaganda from the shows of Solovyov and Skabeeva is so overpowering that people become hysterical in their drive to destroy Europe and America, even if this means they will also die.

Text in the photo translated to English

This may seem like insanity — well, it is insanity.

A very dangerous insanity that has already cost hundreds of thousands of Russian lives — and most certainly, will cost Russia many more.

It might cost tens of thousands of lives to remove the criminal Putin’s regime — or it could be tens of millions of lives who will suffer the consequences of the distorted reality, where Russia is the best country in the world.

~ Elena Gold, Quora

Deeptanshu Singh:

Its just as well that they don't have kids, this will probably be the last generation of Russians to trouble the world before their own demographics screw them over.

*

MISHA’S TAKE ON “WHY RUSSIA IS THE BEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD”

The Head of the Russian Orthodox Church Patriarch Kirill (the bearded man in a floppy ear hat) awarded the Order of Dmitry Donskoy 1st degree to the head of the FSO federal guard service Dmitry Kochnev (the man that holds the umbrella) for protecting him.

There is so much to unpack in this brief summary!

To start with, why does the head of the church need physical protection when he’s the representative of God on earth? Kirill doesn’t put his faith in God to protect him?

Secondly, FSO is a federal security agency tasked with presidential protection. According to its constitution, the Russian Federation is a secular state. The church is separate from the state. Why does the head of the church have the state agency’s protection?

Thirdly, why on earth does the head of the church hand out medals instead of blessings? To add insult to injury, for achievements completely unrelated to spiritual merits but for professional secular duties.

And fourthly, only commander-in-chief and senior military personnel of the Russian Armed Forces are authorized to award military medals — and the Order of Dmitry Donskoy is a military medal awarded “to generals, war veterans, and other persons who showed courage in defending the Fatherland.”

So then who has authorized the head of the Russian Orthodox Church to award a military medal to the head of the federal guard service?

The answer is simple: Patriarch Kirill Gundyaev has a rank of a senior military officer.

He served to protect the Fatherland as a KGB officer in the past and continues to do so in his role of the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. It’s highly likely that he even has a rank of a general, but this information remains secret.

The medal was launched by his predecessor, Patriarch Patriarch Alexy II Ridiger of Moscow. Ridiger was a KGB officer stationed in Estonia, a Baltic republic, and as his name suggests was a Protestant who became a fake Orthodox Christian to serve the Fatherland in the capacity of a fake priest.

Shoigu and Mordichev: Another award ceremony, more interesting facts.

Russian Minister of Defense Sergey Shoigu presented the hero star to the the commander of the Central Group of Forces, General Andrei Mordvichev, who’s responsible for 17,000 KIAs and 30,000 WIAs according to Z milbloggers in order to capture Avdeevka, a suburb of the city of Donetsk, in Eastern Ukraine.

“This is the highest rank in our country and, of course, you deserve it,” Shoigu said.

Let’s unpack it. Why would a man responsible for killing and wounding enough of his own soldiers to populate a medium-sized town be a hero who deserves the highest merit?

No new towns have sprung up in the Russian Federation since its creation in 1991, but whole towns have been getting depopulated. Why award a man who’s helping to send the county into a downward spiral?

Russia cannot create new technologies and build a civilization on its own. Therefore, to preserve the state in all its glorious backwardness, soldiers must be vanquished on the battlefield in great numbers.

These are the sacrifices to the pagan gods to keep progress and cultural evolution at bay and far away from the borders protected by the FSB officers.

General Mordvichev has sacrificed a truly great number of Russians and so the gods must be celebrating, thumbs-upping and high-fiving him down from the Valhalla. ~ Misha Firer, Quora

*

ANTI-MISSILE DEFENSE ACCORDING TO TRUMP

Trump has described

using an “iron dome” missile defense system as “ding, ding, ding, ding,

ding, ding. They’ve only got 17 seconds to figure this whole thing out.

Boom. OK. Missile launch. Whoosh. Boom.” https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/apr/06/donald-trump-speech-analysis

*

THE SELF-CLEANING HOUSE

After Work: A History of the Home and the Fight for Free Time

~ Helen Hester and Nick Srnicek

The Right to Be Lazy and Other Writings ~ Paul Lafargue, translated by Alex Andriesse

~In 1980 Frances Gabe applied for a patent for a self-cleaning house. The design was based on her own home, which she had worked on for more than a decade. Each room had a sprinkler system installed; at the push of a button, Gabe could send sudsy water pouring over her specially treated furniture. Clean water would then wash the soap away, before draining from the gently sloped floors. Blasts of warm air would dry the room in less than an hour, and the used water flowed into the kennel, to give the Great Dane a bath.

The problem with most houses, Gabe thought, was that they were designed by men, who would never be tasked with cleaning them. The self-cleaning house, she hoped, would free women from the “nerve-twangling bore” of housework. Such hopes are widely shared: a 2019 survey found that self-cleaning homes were the most eagerly anticipated of all speculative technologies.

Cleaning, like cooking, childbearing, and breastfeeding, is a paradigm case of reproductive labor. Reproductive labor is a special form of work. It doesn’t itself produce commodities (coffee pots, silicon chips); rather, it’s the form of work that creates and maintains labor power itself, and hence makes the production of commodities possible in the first place.

Reproductive labor is low-prestige and (typically) either poorly paid or entirely unwaged. It’s also obstinately feminized: both within the social imaginary and in actual fact, most reproductive labor is done by women. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that political discussions of work often treat reproductive labor as an afterthought.

One place this elision shows up is in the “post-work” tradition. For the post-work tradition—whose influence on the Anglo-American left has been growing for the last decade—the aim of radical politics should not (just) be for higher wages, more secure employment, or more generous parental leave. Rather, radical politics should aim for a world in which work’s social role is utterly transformed and highly attenuated—a world in which work can no longer serve as either a disciplining institution or the fulcrum for our social identities.

Two new publications bookend the tradition. Paul Lafargue’s 1880 essay, “The Right to Be Lazy”—a touchstone for post-work theorists—was recently reprinted in a new translation by Alex Andriesse. (A Cuban-born revolutionary socialist, Lafargue married one of Karl Marx’s daughters, Laura, in 1868.) Helen Hester and Nick Srnicek offer a more contemporary contribution. In After Work: A History of the Home and the Fight for Free Time, they blend post-work conviction with feminist scruples. A post-work politics must, they argue, have something to say about reproductive labor. The post-work tradition grapples with the grandest themes in politics—the interplay between freedom and necessity. But within its lofty imaginaries, there must also be space for a dishcloth, and a changing table.

Automation has always been central to the post-work imaginary. In “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” (1891), Oscar Wilde envisages a world in which “the machine” is made to “work for us in coal mines, and do all sanitary services, and be the stoker of steamers, and clean the streets, and run messages on wet days, and do anything that is tedious or distressing.” But Wilde gives little thought to the soul of woman under socialism. While the machine frees men from “that sordid necessity of living for others,” it does not lend a hand with the laundry, or feeding the baby. Even in the age of the machine, it seems, women are mopping up after others.

Maybe Wilde thought breastfeeding would be harder to automate than coalmining. But even if we could automate reproductive labor, it’s not clear that we should. It’s one thing to imagine robots taking over the factory, the warehouse, and the office. But, as Hester and Srnicek point out, it’s quite another to envisage them in charge of the hospital, the nursing home, or the kindergarten. A world where no one spends tedious hours on the assembly line is a world worth aspiring to. But a world where no one nurses their children or cooks food for their friends? That sounds like a nightmare.

Reproductive labor, then, resists automation. Can we still aspire to a world without work? One might argue that reproductive labor is not really work (because it is unwaged, or because it happens inside the home, or because it is bound up with love) and therefore lies beyond the scope of a post-work politics. Hester and Srnicek are (rightly) unconvinced. Reproductive labor is work—and work that we can’t offload to a machine. But, they argue, when properly understood, the post-work project can absorb the stubborn realities of reproductive labor; indeed, they write, it “has significant contributions to make to our understanding of how we might better organize the labor of reproduction.”

Critiques of capitalism tend to come in one of three flavors. Distributive critiques locate the badness of capitalism in its tendency toward an unjust distribution of goods. Others identify the wrong of exploitation as capitalism’s core moral flaw. Hester and Srnicek work within a third critical paradigm, whose key moral grammar is that of alienation. Under this rubric, the true badness of work under capitalism—traditional wage labor and unpaid reproductive labor alike—lies in its distortion of our practical natures.

When we fashion the world in accordance with our freely chosen ends, we realize ourselves within it. We exercise a key human capacity: the capacity to make ourselves objective. But under capitalism, we are not free to choose and pursue our own ends; we are forced into projects that we value only instrumentally. We mop floors, deliver packages, or babysit not because we think these activities have value in and of themselves, but because we need the money. We act on the world, yes, but we cannot properly express ourselves within it.

Hester and Srnicek don’t actually talk in terms of alienation; their critical registers are those of “temporal sovereignty” and “free time.” But these are novel placeholders, used to freshly mint an argument for which alienation has been the customary coin. “The struggle against work,” they say, “is the fight for free time.” And free time matters because, they argue, it is only when we have free time that we can engage in activities that are chosen for their own sake: activities in which we can “recognize ourselves in what we do.”

Such activities needn’t be leisurely. Someone who composes a sonata might be composing just for the sake of it—laboring with “the most damned seriousness, the most intense exertion.” (Here Hester and Srnicek quote the Marx of the Grundrisse.) Even dull, menial, and repetitive activities may enter into this “realm of freedom” when they are a constitutive part of appropriately valued projects. “Laboring over a hot stove,” Hester and Srnicek write, “can take on the quality of being a freely chosen activity in the arc of a larger self-directed goal.”

Hester and Srnicek, then, are not advocating indolence. For them, the problem with work is not that it is effortful. Humans are agents. We make and we do. Work, though, catches our making and doing in a trap: it is caged agency. Hester and Srnicek want us to open the cage.

Hester and Srnicek’s friendliness to effort marks one point of difference between their approach and Lafargue’s. For Lafargue, freedom is more closely tied to idleness. Hot stoves don’t feature in his post-work world. His vision of the good life centers on lazing about, smoking cigarettes, and feasting.

The differences don’t stop there. Hester and Srnicek offer a moral critique of capitalism, one that appeals to values. Despite Lafargue’s title, with its talk of a “right,” his main focus is political economy. He is best read as offering a “crisis theory” of capitalism: a form of critique that appeals not to moral damage but rather to capitalism’s structural instability. Capitalism, says the crisis theorist, is a flawed economic system not because it is (say) cruel, but because it is a self-undermining system. It destroys its own capacity to function.

The roots of crisis, for Lafargue, lie in the inevitable mismatch between the productive capacities of a capitalist society and that society’s capacity to consume what is produced. Capitalism, he thinks, requires that workers play two roles: they need to make things, but they also need to buy them. Eventually, these two roles will come into conflict. Suppose that a commodity is overproduced, so that its supply outstrips demand. Its price will fall. To compensate, factory owners will cut costs or slow production. And that means they will pay their workers less or lay them off. Consumer demand will then further contract, incentivizing further wage cuts, which will further suppress demand. Worker and capitalist will both be trapped in an ever-tightening fist of economic dysfunction.

Lafargue’s innovation was not to link overproduction with crisis—hardly an original suggestion—but rather lay in his proposed solution. Where twentieth-century Keynesian reformists proposed to coordinate production and consumption by stimulating demand, Lafargue pushes in the opposite direction. We should coordinate by suppressing production; workers should simply work less. Thus, Lafargue posits not so much a right to be lazy as a duty. Those who shirk it are to blame for overproduction. “The proletarians,” he writes, “have given themselves over body and soul to the vices of work [and so] they precipitate the whole of society into those industrial crises of overproduction that convulse the social organism.” (This haughty tone is of a piece with the rest of the essay, which is consistently disdainful.)

This argument makes for an unusual brand of crisis theory. Most crisis theorists trace overproduction to structural features of the capitalist economy. This underpins their contention that overproduction is not just bad luck but a sine qua non of capitalism. “It is in the nature of capital,” Marx wrote in Theories of Surplus Value (1863), to “drive production to the limit set by the productive forces . . . without any consideration for the actual limits of the market.” Insofar as overproduction is sufficient for crisis, then, it will also be “in the nature of capital” to undermine its own productive capacity. For Lafargue, by contrast, overproduction is not a structural necessity but a function of working-class myopia.

Lafargue doesn’t worry that suppressing production will lead to scarcity. If the proletariat do manage to withhold their labor, he thinks, then laziness will become not a duty but a default. If workers work less, industrial equipment will be developed more quickly to compensate; and this trend will eventually result in a post-scarcity, post-work idyll.

And Lafargue is at best impressionistic as to what life in such a world might be like. The niceties of (say) institutional design are quite beyond his ken. This marks a third point of contrast between Lafargue’s essay and After Work. Lafargue is primarily focused on the pathologies of industrial capitalism and on how they might be overcome. After Work, by contrast, is more interested in providing a blueprint than a roadmap—less concerned with how we might arrive in a post-work world, that is, than with how to organize things once we get there.

*

After Work begins with a puzzle. Post-work theorists propose “free time for all!” But what if the parents’ free time can only be purchased at the cost of their baby going hungry or unwashed? How can free time for all be secured alongside care for all?

In their attempt to realize both, Hester and Srnicek make three key moves. First, they argue that a lot of reproductive labor is unnecessary. They give the example of ironing. If style norms became more crumple-tolerant, ironing one’s shirts could become an optional eccentricity rather than a burdensome chore. And if caring for someone doesn’t mean doing their ironing, care and free time become more compatible as goals.

Of course, some reproductive labor is nonnegotiable; Hester and Srnicek know this. So they make a second move. Reproductive labor’s resistance to automation, they contend, has been overstated by the squeamish (and the privileged). Waged care workers often “point to elements of their jobs that could usefully be automated,” giving them more time to focus on the bits of their job that require a genuine human connection. Hester and Srnicek cite surveys showing that pensioners are significantly more open to the use of robots in elder care than other groups are. This is perhaps not surprising when we remember—Hester and Srnicek are careful to remind us—that we should not sentimentalize caring relationships. Many older adults are abused by their caregivers.

Hester and Srnicek are not crude techno-optimists. They realize that tech can be labor-extractive as well as labor-saving. Despite the “industrial revolution in the home” in the first half of the twentieth century, full-time housewives spent more hours per week on housework in 1960s (fifty-five) than they did in 1924 (fifty-two). Social expectations tend to ratchet up alongside technological proficiency. If it now takes half the time it used to take to hoover—well, you’ll just be expected to hoover twice as much. Hester and Srnicek give a deadpan account of a 1940s advertisement for a washing machine: “once the clothes are in the washing machine,” says the delighted customer, “I’m free [sic] . . . to do other housework.” Automated reproductive labor, then, doesn’t guarantee more free time; we must also lower our collective standards. (That’s good news for slobs like me: crumpled clothes, hairy legs, and messy houses can be figured as a kind of a kind of lo-fi political resistance.)

Nonetheless, Hester and Srnicek do still have a somewhat coarse view of the relationship between technology and freedom. For Hester and Srnicek, technology expands the realm of freedom. It does this by adding new options. Without a dishwasher, I have no choice but to do the dishes. But once I have a dishwasher—here they quote Martin Hägglund—“doing dishes by hand is not a necessity but a choice.”

The example is not as compelling as it might seem. I once could have traveled by horse and carriage from Oxford to London, but thanks to the internal combustion engine, the public infrastructure required for such a trip to be feasible no longer exists. The United States’ car-focused public infrastructure prevents its citizens from doing simple things, like walking to work. When it comes to social arrangements, technology both adds options and takes them away. It destroys some forms of compulsion while creating its own mandates. It need not roll back the sphere of necessity.

Hester and Srnicek might more be sanguine than most about automating some reproductive labor. But they are not sanguine about automating all of it. This technological remainder motivates a third move: efficiency. The basic social infrastructure of the Global North funnels reproductive labor into the sealed-off space of the household, which is tied to biogenetic kinship and “nuclear” living arrangements. This enclosure prevents specialization and (temporal) economies of scale: when everyone has their own kitchen, everyone has their own kitchen to clean.

But such an arrangement is not inevitable; the atomic household needn’t function as the default locus for care work. We might instead rely, as the United Kingdom did during World War II, on public canteens—decorated with art from Buckingham Palace—that cooked nutritious meals prepared at scale. (These “British Restaurants,” Hester and Srnicek point out, were initially called “communal feeding centres,” but the name was vetoed by Winston Churchill for “sounding too communist.”)

It’s helpful to situate this suggestion in terms of three social dynamics posited by Nancy Fraser. First, there is the struggle for social protection: demands for material security. Second, there is marketization: the tendency for more aspects of social life to be commodified. Third, there is the struggle for emancipation: demands that social hierarchies like those of race and gender be dismantled. Fraser notes that each of these forces is politically ambivalent. The family and the welfare state are iron fists as well as velvet gloves: they can offer protection, but they also discipline those who break its rules. Marketization breeds vulnerability, but it can also offer a route to freedom. You might, like me, prefer for your material security to depend on your earning power than on your ability to keep your husband happy. And emancipation struggles may weaken social bonds—and thus a basis of social protection—in the course of dismantling hierarchy.

In terms of this typology, After Work attempts to show that demands for social protection—specifically in the form of care—can be met without compromising on emancipation. Existing models of care provision tend heavily towards privatization: your care is either a business (traded on the open market), or nobody’s business but yours (a family affair). After Work suggests a third option: care should be communal. Households should be more porous—for example, they should share communal goods and spaces—and they should no longer be the centers of gravity around which informal relations of care revolve. As a result, the burden of care is lifted from the household, but not offloaded onto the market. What’s not to like?

Yet real life is messier than this solution allows. Communal spaces can be lovely; they can also be deeply unpleasant. I don’t like cleaning my kitchen, but I also like not having to share it. When I read After Work, I was visiting my brother in Edinburgh, and we sat talking about it on the bus. He was enthusiastic about the idea that more of our lives should take place in shared spaces. Then a baby started to scream, and we couldn’t talk for the rest of the journey. “I guess this is why people like cars,” my brother said, darkly.

It could well be that other people’s screaming children are a price worth paying for a functional care infrastructure. But there’s no getting around the fact that there are costs to making our lives more communal. No transition to a post-work world is (democratically) possible unless people can be persuaded that the form of life on offer in the communal feeding center is a form of life that they would want.

Such persuasion might well be possible, but it’s not a task that Hester and Srnicek really attempt. They do acknowledge that “not everybody would feel comfortable living in fully collectivized living spaces for any great length of time, and many will want more than a single bedroom to retreat to.” And collective living, they are clear, “cannot be imposed from the top down.” Hester and Srnicek argue that, if we want free time, we will need to live more communally. But what they take as an argument for more collective living, someone else might read as an argument against shrinking reproductive labor to a minimum. After Work maps the territory for political battle but doesn’t begin to fight it.

The book’s vision doesn’t end here. Hester and Srnicek realize that while we might be able to shrink the amount of reproductive labor that needs to get done, we can’t shrink it to zero. So alongside their main approach—lessening the burden—they offer two other strategies.

The first is to incorporate care work into their picture of flourishing: what it means to live a good life. In a truly just society, this strategy says, caring labor will no longer be alienating, because we will value service to others—either for its own sake, or as part of an authentically valued project. In the lesbian separatist communities of second wave feminism—the landdyke commune, the Oregon-based “WomanShare”—participants dug ditches, converted livestock outbuildings into homes, and went in for low-tech farming. Under different conditions, such work could easily be alienating. But when folded into a larger political project to which the women freely subscribed, even their drudgery became meaningful—an expression of agency, rather than a straitening of it.

Wilde thought a post-work utopia would mean a world in which we are relieved of the “sordid” requirement to care for others and would be free to “realize” our own personalities. But Wilde got things back to front, say Hester and Srnicek. Caring for others is not a squalid compromise with scarcity; rather, we can realize our personalities by caring for others.

The analytic Marxist G. A. Cohen illustrated the logic of such arguments by analogy. Say we want a world where there’s a plentiful supply of blood for transfusions, but also where no one is coerced into giving blood. It might seem that there is a tension between these two goals. But there isn’t, Cohen says: if we create a culture in which people want to give blood, then we can have both blood and freedom. Similarly, After Work suggests, a just society will shape the souls of its citizens, so that they want to serve. One might wonder whether soul-making is really an alternative to coercion, rather than a particularly subtle form of it. But in Hester and Srnicek’s hands, at least, it is not sinister social programing so much as the insight that necessary labor could be structured on “more agential terms,” thus making it a more attractive pastime.