*

REVENGE

But if it came to light,

*

Likewise … I

But if he turned

Nazareth , April 15, 2006

~ Taha Muhammad Ali, translated by Peter Cole, Yahya Hijazi, and Gabriel Levin

*

WHY COMMUNISM HASN’T WORKED

~ Probably the biggest flaw in communism can be linked to the famous Marxist slogan, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” This describes a world in which everyone contributes 100% of their ability allegedly in exchange for having 100% of their needs met.

The problems with such an arrangement are myriad: humans are not equal in ability or need, and if only your needs — never wants — are met regardless of what you do, there's little incentive to do more than the bare minimum, let alone give it 110%. Thus, you wind up with productivity problems and a lack of innovation.

But beyond this, communism ignores human nature: the vast majority of people care more about themselves and their loved ones than others. That doesn't mean that people don't care anything for others — people pay taxes and donate to charities because they recognize that there are needs beyond their own — but human nature is such that if people are working hard, they want to be able to reap the rewards. A joyless system of perpetual sacrifice for the state gets old quickly for non-zealots.

Second, controlled economies are always teetering on the edge of disaster because the wisdom of a small in-group, no matter how intelligent, is less skilled at identifying people's highest use and anticipating need compared to the free market, and is less adaptive when there are misses. Thus, communism often struggles to meet even basic needs.

Finally, because of the issues above, end-stage communist nirvana has never been achieved, because it devolves into authoritarianism, an attempt to stop the complaining and do away with human nature at gunpoint. ~ Ty Doyle, Quora

Andrew Olson:

You, like almost everyone else, left off the prerequisite to ‘from each according …’

Which is a post scarcity economy.

Pete Smoot:

There’s also the practical problem that in order to transition to communism, 20th century experiments went through autocracies or tyrannies. The autocrats and tyrants never seemed to want to give up power and have a universally horrible track record of murder and human rights abuses.

Peter LaFond:

There is no concept of economic growth. American progressives have the same blind spot.

Richard Morris:

Great post. I want to emphasize your point about innovation. Communism cannot “reward” innovation. Rewards are needed to provide feedback for successful business practices. Without rewards a system becomes stale and complacent.

Murali Tumahai:

People espousing the benefits of these experiments never allow for the presence of narcissists and psychopaths in society.

Bill Lovell:

Plus the line that didn’t come from Marx, but should have: “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.”

Lee Jacobson:

Even in small scale communism, such as the Kibbutz in Israel, eventually collapse due to this disagreement on distribution of the resources (i.e. to each according to his need) by a small cadre of officials. For example, “the Kibbutz has decided that your son is too stupid for us to support his university education”, and there is no appeal but leaving the Kibbutz. And so Kibbutzim have, for the most part, shut down.

SUSANNA VILJANNEN: THINK OF LIVING IN THE MILITARY 24/7

Communism fails because it does not take into account the innate, biological nature of human being and the human psychology. It assumes humans are collective animals (like ants or bees or termites) whose psyche is a blank slate, which is completely programmable, who have no individuality nor innate traits whatsoever and who are completely fungible.

The biggest failure is assumption that humans can selflessly work for the common good without self-interest. And alas, it doesn’t work that way.

In reality, humans are ba5tards. Ba5tard-filled ba5tards with ba5tard coating. We are selfish to the boot, and our traits are mostly innate — either inherited by the genes or triggered by the epigenetics. We are programmable only to an extent. And we act only on selfish interests.

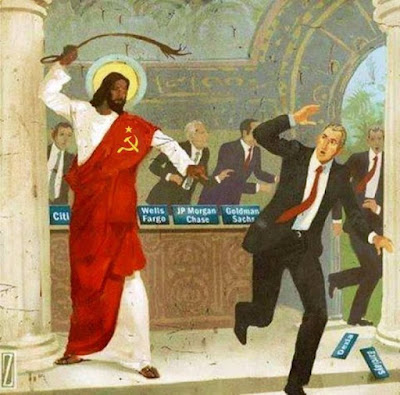

The only way humans can act on unselfish interests for the common good is religion. It is the only way how humans can overcome their selfish interests and work altruistically for the common good. And Communism is utterly hostile to religion!

All secular utopian societies have collapsed in less than a century, usually latest at the third generation, due to internal disputes and chaos. Conversely, religious ideal societies can last for millennia. Monte Cassino monastery has been founded 529. Still functional. Likewise, Heian monastery has been founded 711. Still functional. We know the Hutterite farms in North America. Likewise, all the remaining kolkhozes in Russia and kibbutzim in Israel are religious.

Communism is basically a self-defeating memeplex. It is based on wrong assumptions and wrong interpretation on input, so it will quickly turn chaotic.

Garbage in, garbage out.

The only way to impose Communism without religion is brutal discipline and coercion. This is the reason why all Communist regimes have eventually become little Soviet Unions. The horrible monolithic regime, coercion, ineffective and corrupt means of production, utter disdain on human decency and continuous lack of resources and means. This is what happens when the feedback loop between the control tier and the productive tier is too long; the system becomes unstable due to the impulse lag.

Capitalism is NOT self-stabilizing nor self-correcting (no system where there is at least one positive feedback ever is), but the feedback loop between the control tier and productive tier is much shorter and quicker. Therefore capitalism can react on any disturbances on the system much quicker and prompter and produce far more desirable results. ~ Quora

KARL VANBRABANT: NATURAL HIERARCHY OF LOYALTIES

Normally, to every person there is a system of loyalties that is partly based on self-interest. First comes the individual itself. Or as the German saying goes: first belly full, after that morality (“Erst das fressen und dann die moral”). After that comes family. After that the local community. After that the wider community or the area, and after that the ethnicity to which the individual belongs. only after that comes the state or a political party.

Communism wants to reverse all that: First the state, and all the rest will be placed at the same level. Since it can’t work if there are many parties with different ideas, this state will have to be a single-party state. This means people who don’t believe in this reversal of the loyalty system, either have to be persuaded , or they have to be suppressed and persecuted. This means a lot of people will think about themselves and their family first and play along. It will end with a grandiose charade that’s bound to one day collapse.

Add to that the fact that Marx was against religion. If you’d take the above loyalty system, the religion will always fit at almost every level. Marx simply wanted to do away with religion, but when you look at history, that’s a stupid idea: people have always worshipped something, even if it was the sun and the moon, or a mountain or whatever. It’s just human nature. However, religion can make it difficult to abandon the loyalty system, as it can be closely interwoven with it. That’s why religion prevailed in communist countries: people refused to place communism above their beliefs.

Mac Dara Mac Donnacha: TOO MUCH GOVERNMENT VERSUS NOT ENOUGH

~ Capitalism (by which I assume you mean a market economy) doesn’t really need much administration to work. If there’s a demand, odds are someone will meet it with supply. If demands change, supply changes with it. Now, absent administration, capitalist systems will inevitably lead to economic crashes (and even with administration, you can mostly just delay the crashes, or cushion the blow), but also inevitably the capitalist system will pick itself up, step over the bodies of the casualties of the crash, and move on.

So I’m assuming by communist you mean something like Soviet Style communism, or in other words a centrally planned economy. This is an economy in which the government makes decisions on production. Instead of being driven by the desire for profit, the economy is driven by the desire to do what is best for the country as a whole. On the surface this seems like a good idea, but the problem is in the implementation.

Consider for example that the government has deduced that there is a need for increased agricultural production, due to an increasing population. So they order the farmers to grow more food. But to grow more food, the farmers need more material — fertilizer, farming equipment etc. They ask the government to provide these things, and eventually the government agrees. But then when the food is produced, you need transportation vehicles, storage facilities, distribution facilities, and the staff for all of the above. And consider the requirements hidden behind each of those: if you want more trucks to move the food, you need to build more trucks, which means more materials for the trucks, possibly new factories, factory workers…

If the government fails to anticipate and provide for any of the steps in the above, the system breaks down a bit. Maybe there’s not enough trucks, or too many. Maybe food ends up rotting in a warehouse somewhere because there’s not enough workers to distribute it. Inefficiencies begin to creep in. And as the decades go by, they get worse. These can eventually be identified and fixed, but by then the necessities of the economy will probably have changed again, and you’re already behind.

In a capitalist system, such problems are almost inevitably spotted by someone and identified as an opportunity for profit. If there’s a need for more trucks, the price for trucks goes up as they get snapped up, and producers quickly build more. If there’s food waiting in a warehouse, someone will quickly hire staff to sell it. And if anyone spots a method to make any part of the process more efficient, they’ll implement it — for a price.

Now, to be clear: capitalism, if left to its own devices, is terrible. While centrally planned economies have their problems, it’s arguable as to whether they’re worse than a totally free market economy. For a market economy to not be a total shitshow, it requires careful regulation and plenty of government intervention.

There are certain services that the free market is terrible at providing — e.g. law enforcement, defense, healthcare, education — and you need government regulation to stop the formation of monopolies and other economic dead end phenomena that free markets otherwise eventually spit out. Most of these issues are what economists call ‘market inefficiencies’ (you can google a few examples), and they will lead to a Great Depression/Great Recession/Armageddon if you let them. ~

Don Callaghan:

Capitalism, in theory, allowed the greatest freedom and most diverse solutions. The problem is it leaves too many by the wayside.

Ke’Aun

Workers across the planet tend to associate far more strongly with their nation or state than they do their class. Few are as fervently patriotic, nationalistic, or ethnocentric than the world’s “workers and peasants” — the exact class the Communists want on their side.

*

DIMA VOROBIEV: THE IDEA OF COMMUNISM SPRANG FROM CHRISTIAN MONASTERIES

The cardinal flaw in Communism lies in the amazing fact that this collectivist ideology only seems to work for people who believe in individual salvation.

Communism is basically two things:

No private property. You share with other people the tools, land, trees, ideas, cars, works of art that make your living.

You contribute to the common pot what you can, you get out of the pot what you need.

The idea sprang from the Christian monasteries. People there who had enough spare time to pray and used little of it to enjoy themselves, sooner or later came to ask themselves and everyone around: why can’t the whole humanity live the same pious, quiet and spiritual lifestyle as us? There will be no wars, no angry people, no famines, no suffering.

Then Marxists came with a very practical answer: we can make it work if we mandate that everyone give up their private property. Everyone will work for everyone’s salvation. To top it, no one will need to die to get the Communist salvation: it all will happen in this world, not the next one!

In the XX century, Communists managed to organize themselves to grab power across much of the world. They met much resistance, but ultimately overcame it. The largest and the most populous countries in the world even became a clear and present danger to the most prosperous and strong Capitalist countries. Eat that, you bourgeois scum!

There turned up to be just one problem: humans are shaped by evolution to be a bunch of lazy, selfish, sneaky, predatory bitches. Only fear of pain, starvation and death gets us off our idle behinds to make ourselves useful. There are also a tiny minority of people who are driven of curiosity, vanity and the desire to make a difference. But they are a maddeningly selfish bunch. They prefer to do their own stuff and object strongly when other people tell them what to do.

There’s also a powerful unselfish thing called love. It can do wonders and prevail over everything. But the unselfishness of love makes it the most dangerous enemy of Communism: people eagerly sacrifice the common good for their kids, their lovers, their family and their friends.

There is only one thing that seems to be able to trump our (1) selfishness, greed, laziness and (2) our loyalty to the loved ones. It’s the love of God and faith in individual salvation. This is what the tale of Abraham and sacrifice of Isaac is about. For us common people, this means: God is willing to give us individual salvation if we are ready to betray for him our loved ones. (We have a Communist rendition to the Abraham’s test, “Who do you love more, the Soviet rule or your Dad?”)

The history of Communism shows that the idea of Marx about the ideal society requires the degree of individual discipline and self-policing that no totalitarian society can assure. You need a community of people who are obsessed with individual responsibility in the face of God. If you start mixing these pious creatures with lazybones, creeps and men/women in love with each other, the latter ones get a ginormous unfair advantage. They will be piggybacking, leeching and stealing for themselves wherever possible, while the self-sacrificing dimwits will be busting their backs to make everyone’s life better.

You may of course put the police, workers’ watchers, KGB operatives and neighbor informants on the task of enforcing Communist morals. What happens next is the lazybones, leeches and thieves find every possible hole to become the enforcers. This is exactly what happened in every single place from Soviet Russia, to the Red Khmer’s Kampuchea, to the Chavisto Venezuela.

Upshot to the story: you may make Communism work, in some places, for some time. For achieving that, you need (1) people who believe in individual responsibility before God, (2) a wall between them and people who don’t believe in God, (3) a preferential arrangement from the government in terms of property protection and economic incentives, because on even terms greedy people always outcompete selfless people.

The poster below “Protect your honor from young age!” sends a subliminal signal to new recruits in the Soviet workforce: if you don’t perform at the top of your capacity, pretty girls won’t date you. The girl disparagingly points to a poster that shames a “deviator from workplace requirements” where the lazybag looks confusingly like the young male worker to the right.

Charles Tips: FREEDOM TO BE CREATIVE

I moved to Berkeley in 1977 and met a few newly arrived Russian refugees. I was asked at one point, because I had a car, if I wouldn't show a just-arrived-the-day-before refugee around. He was late-20s like me and I found out that he was a welder, so I took him to the work studios down near the waterfront where artisans crafted unique items.

He was stunned. After a couple of welding shops, he confided that his true love was cabinet work; the state had mandated he be a welder. We found a studio where a couple of craftsmen were working on a table top, circular, maybe twelve feet in diameter with intricate inlays of several exotic woods. He talked in his broken English with them for almost an hour, and they invited him back to help for pay.

When we left, he thought he was in Heaven. The idea that you could choose your own profession, own your own tools--even your own shop, work your own hours, hire your own help (and do it so informally), create your own designs... this was unbelievable to him.

Djin Dueh Nuphen: INCENTIVES MATTER

Simple. Capitalism has a built in appeal to human nature: Reward.

In a capitalist system, if you are smart, work hard, maybe invent something you can succeed. By your success you can have things like food, shelter, etc. Those things, and the other fruits of your labors are YOURS. they belong to YOU. And those things tend to be distributed by the amount and the quality of your efforts to be a productive and contributing member of society.

Under a communist system the exact opposite is true. Success is disincentivized. Nothing you produce belongs to YOU; everything you produce belongs to the COLLECTIVE. People who work hard get just as much as those who shirk. Or perhaps it is better to say those who contribute the least get as much as those who contribute the most. Worse than that, “the nail standing up gets the hammer”. If one is smarter, stronger, better, etc., that person is either a threat to the others in the collective, or is expected to be worked harder than one’s peers for the same pay. The more you produce, the more is taken from you.

When you set up a society based upon “From each according to ability, to each according to need”, you wind up with a lot of needy people incapable of doing much of anything.

Casey Jones: THE FREELOADER EFFECT

It has something to do with the freeloader effect. Capitalism provides incentive to work hard and guarantees that you will be able to collect the fruits of your labor if you do. It rewards exceptionalism and innovation and allows the best and brightest to rise to the top and bring everyone else with them. This is the reason why capitalism is so successful and has even been allowed in small doses in places like China.

Communism stifles creativity and forces the best and brightest to work in jobs that are below their capabilities. It also provides lazy and uninspired people additional opportunities to slack off and freeload knowing that the government will still provide for them. This is why communism has ALWAYS ended badly. Talented hard working people get frustrated, lazy people take advantage, and the whole thing falls apart, usually with disastrous consequences.

Harpo Veld: PEOPLE CARE MORE ABOUT THEIR OWN FAMILIES

Communism works fine in families.

In rare cases, it works in communities larger than a family, but still very small.

It has never been observed to work for any large group of people.

Capitalism works everywhere for large groups.

Even in horrendously corrupt third world shitholes, it works orders of magnitude better than any collectivist scheme. The reason is simple — nobody cares about others as much as they care about their own family. Collectivism is unnatural, and can only be established and maintained through violence.

Blake Davis:

Capitalism thrives because it depends on human greed. Socialism often doesn’t work because it depends on altruism. Communism almost never works because the “leaders” are self-appointed and have no responsibility to the rest of the population.

Peter McKenna:

There had never been an example of a country using pure capitalism or pure communism. The only systems that have thrived are a mix of capitalism and socialism.

Franz Kawabata:

There are no economic systems that work for everyone. Every economic system has had those for who it didn’t work for.

Most economic systems end up having a Pareto type distribution where 80 percent of the wealth is controlled by 20% of the population. It doesn’t matter if the system is a market-based system or a socialized system or a communist system. 80% of the wealth will end up in the hands of 20% of the population.

A market-based system with some social safety nets seems to work fairly well for most people. But no system is going to work for everyone.

Joe: BOTH ECONOMIC SYSTEMS OPERATE IN A MACROECONOMY BASED ON CAPITALISM

Most people know about communism’s failures but ignore the malfunctions of capitalism. In the United States, people deny the failure of the free market to provide for the least skilled people. The homeless problem demonstrates the inability of capitalism to provide work for the least skilled labor. Labeled as lazy, alcoholics, addicts, or mentally unstable, the homeless remain invisible to those counting the unemployed. Another example is the lack of affordable housing.

Many examples of capitalism’s failure exist, beginning in the 13th and 14th centuries. American schools fail to teach the deficiencies of capitalism. We learn only about the one percent representing the most successful individuals in a free market system.

Maybe there is a difference in their production systems that has a significant impact. Comparing communism and capitalism as they work in the real world, we find that a factory in the USSR and a factory in the United States use very similar divisions of labor.

Below is an organizational chart depicting the organizational breakdown of the factory structure.

It displays the relationship between wage and rank. The higher-paid workers are at the top, and the lower-paid workers are at the bottom.

· Management

· Engineering

· Quality Assurance

· Machinist/mechanics

· Assembly (line-workers)

· Materiel handlers

Whether production is under a communistic or a capitalistic system, manufacturers sell their goods for a profit, and it depends on a growing market. Thus, both economic systems operate in a macroeconomy based on capitalism. Therefore, both economic systems must differ in dispersing their profits.

Neither says how they distribute profits equally. In both systems, wages are considered part of the production cost. Profit is the difference between the price and the cost of a product.

Communism argues that the state will distribute profit more equitably than a business, and capitalism believes the opposite is true. Neither communism nor capitalism provides for equitable profit sharing, and we need to discuss fairly distributing the monetary returns.

Maybe the most significant difference between the two systems is whether they operate under a dictatorship or a democracy.

Oriana:

In response to Joe's main point: Perhaps the most frequent statement about communism is that no country has ever been able to implement this utopian system. What we get instead is "state capitalism." The government tries to manage factories and stores; except for special cases like the postal service, law enforcement, first responders, and the military, we basically end up with inefficient capitalism. And for political reasons, under "communism," it's more difficult to find competent mangers, and even more difficult to fire one.

"The business of America is business" — that certainly seems true. But what exactly was the business of the Soviet Union? To create an earthly paradise for assembly-line workers? It's hard not to burst in laughter at any such answer. And those who live in officially capitalist countries have all been taugh that capitalism is the only system that produces wealth. It rewards business skills rather than loyalty to the boss.

I keep returning to this topic because I grew up behind the Iron Curtain in a very Catholic country, and saw that the church was more powerful than the state. The church had much better propaganda and made more attractive promises (one can’t really compete with the invention of heaven and hell). Even so, the similarities were inescapable. I speak about the past. At present the power of religion is declining, and yet many people, and not just the young people, long for something they could believe in, some ideals they could work toward — without having to believe a bunch of garbage, i.e. the supernaturalism of religion.

So it’s back to working out one’s own limited happiness and meaning in life, and learning the hard lessons: not everything is possible. What works well for one person may be a disaster for someone else. Don’t attempt too much at one time. The Golden Rule — which I’d call the law of empathy — how would I want to be treated in a particular situation? — is the only principle that appears to work practically all the time (I say “practically” because another hard lesson is that there are exceptions to every rule, and you need a case-by-case approach).

I lean to the position that it’s a good thing that communism has been attempted — otherwise we’d always be wondering if such a system could work, and if so, what kind of paradise we're missing for lack of trying. And I also feel grief that untold millions of lives have been lost and/or made miserable because of that experiment. And, above all, remember that nothing is perfect.

“We manage best when we manage small.” Who said that? Linda Gregg, a poet who arguably never achieved greatness, but to whom I’m immensely grateful for that particular line. And to write even one line who helped one particular reader is already something rather than nothing.

Or to plant even one tree. Or to raise and love even one child. To help even one neighbor in his or her hour of need. To teach someone even one useful thing. I think best when I think small. But other people operate differently, and that’s fine. Tolerance. Respect. Empathy — or call it the Golden Rule — or just ordinary decency.

*

Ideology is the curse of public affairs because it converts politics into a branch of theology and sacrifices human beings on the thoughts of abstractions. ~ Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.

*

THE FREEDOM LEGION: RUSSIANS WHO FIGHT AGAINST PUTIN ON THE SIDE OF UKRAINE

On the morning of March 12, 2024, several armed groups crossed the border with Russia in Kursk and Belgorod regions on pickup trucks and tanks, supported by mortar and artillery fire.

The shocked residents posted videos of tanks with blue flags passing through their villages.

The groups that crossed the border are the Siberian battalion, the Legion Freedom of Russia and the Russian Voluntary Corps. These regiments consist of citizens of Russia who fight on the side of Ukraine against the armed forces of the Russian Federation.

Russian citizens join these regiments to fight against Putin’s regime, for the freedom of Russia.

Lozovaya Rudka, a village near the border in the Belgorod region, is completely under the control of the RVC.

After a shooting battle, Tyotkino in Kursk region is also under control of the rebel forces.

On March 11, drones attacked Moscow, St. Petersburg, Tula, Nizhny Novgorod regions, Belgorod, Kursk, Oryol, and Voronezh in Russia.

Oil depots, refineries and other infrastructure facilities are burning after the hits.

In the Nizhny Novgorod region, a drone attacked a Lukoil oil depot. The main crude distillation unit was damaged in the attack.

At the oil depot in Orel, one of the fuel tanks was set on fire, which has been expanding for hours, destroying everything in its path.

In St. Petersburg, the Southern Thermal Power Plant is on fire.

As a result of explosions following a Ukrainian drone attack in the Belgorod region, power lines were damaged, leaving 7 settlements without power. Videos of drones freely flying over Belgorod are all over Russian social networks.

Su-27 plane was shot down over Belgorod region.

Another plane, transport aircraft Il-76 with 15 military personnel on board, crashed in Ivanovo region.

Meanwhile, Russian RIA News reported that “Kyiv is building up its forces near the Russian border.”

The Legion "Freedom of Russia" recorded an appeal on the Russian-Ukrainian border.

“Putin is planning to rule till his death. We won’t allow it! We are Russian citizens, just like you. We too have the right to express our will. And our will is to not recognize the bloody dictator as the president of Russia,” said the commander of The Legion.

“We will take our land back from the regime, centimeter by centimeter. Russians will sleep peacefully, they won’t be afraid of the doorbell, and will be able to say what they think without fear. Russians will vote for whom they want, and not for whom they should. Russians will live freely!” ~ Elena Gold, Quora

*

MORE RUSSIAN REFINERIES ON FIRE

2 more oil refineries went on fire in Russia today. (March 16, 2024)

Drones attacked oil refineries in Syzran and Novokuybyshevsky, Samara region.

Notably, Syzran is 1,300 km from the border with Ukraine.

The governor of the region, Azarov, officially confirmed to RIA Novosti that fire broke at oil processing plants.

It’s already refineries #13 and #14 that suffered hits in Russia.

In response, Russia hit a residential building in Odesa, Ukraine, with a ballistic missile. And then Russia hit it with a ballistic missile again, targeting first responders – emergency services and medics, in an effort to obtain maximum civilian casualties.

20 people died as the result of the “double-tap” attack, more than 70 people wounded, several of them are in critical condition.

And to all these asking, “What did you expect?”, the answer is “Ukrainians expected to live their lives in their country without Russia or its useful idiots asking stupid questions”.

Ukrainian families experience pain and suffering every day. Only the complete destruction of the "beast from the east" will put an end to suffering.

Dmitry Medvedev (who always expresses what Putin wants to say but can’t) proposed the Russian version of “peace formula”: Ukraine must capitulate, the whole territory of Ukraine must become Russia, all Ukrainian officials must be removed, and Ukraine must pay a compensation to Russia for the Russian soldiers killed and wounded in the war.

So, we now have Russia’s “peace plan” — anyone who would like to suggest to Ukraine to negotiate with Russia, should be simply directed to Medvedev’s Telegram to read this remarkable plan in full.

Now any country should know: if Russia attacks you, this means they are going to keep killing your people and destroying your cities unless you surrender. And then they are going to annex your land and demand compensation for the inconvenience. And, of course, they are going to torture and kill the people who don’t love Russia, deport half of population to Siberia, and relocate Russians from Russia to live in the homes of deported locals.

This all had already happened before. The Soviet Union was attacking smaller countries and demanding capitulation, and when the governments signed capitulation, Soviets immediately began executions and deportations, and brought hundreds of thousands of their own settlers to change the ethnic composition of the annexed territories.

There is nothings that Putin is doing now that the leaders of Russia and the Soviet Union haven’t done before. That’s what they always do

This inhumane regime must be destroyed once and for all.

French president Macron stated that this war is existential for Europe. Putin can’t be appeased. Any appeasement only leads to increased appetites of Kremlin elders. The free world must unite efforts to help Ukraine put an end to the Kremlin’s genocidal war. ~ Elena Gold, Quora

*

MISHA FIRER: INSIDE RUSSIA

~ Capitalism divides people into winners and losers. Possession of capital is viewed as the ultimate virtue by almost everyone in the society and lack of thereof as a cardinal sin.

The educated middle class abandoned Vladimir Putin after he staged his third, illegal term in office. His support base ever since have been the people whom the Russian capitalist system would characterize as losers if it were honest with itself, plus business and political elites who have benefited financially from this social contract.

Losers turned May 9, Victory Day street celebration, into a validation of their secret cravings for self-identification with the strong and all-powerful state.

All of them dressed up in Red Army uniforms, transformed their sets of wheels into flashy battle tanks and hoisted Soviet flags proclaiming that they are headed to Berlin to win BIG.

They didn’t want to fight. They cosplayed meat assaults of their grandfathers to boost their fragile egos with victories they couldn’t bring themselves to achieve within the framework of the new capitalist society.

Losers pretended to be winners for a day and limped home with a tail between their legs to the dreary lives of underpaid clerks, small business owners, mechanics , security guards.

And then, oh miracle! Putin had offered them an opportunity of a lifetime to join the actual WW2 style fighting against the new Nazis in Ukraine!

He called out for “partial mobilization” that was meant to recruit ONLY combat veterans and reservists of certain specialties, the very contingent who bought them by means of five year car loans big shiny Toyotas the size of their flats in prefab panel blocs, built in post-WW2 to house survivors cheaply, efficiently, and quickly.

You would expect the brave cosplayers (Hitler kaput! Russians are coming!) who pumped fists in the air and swore “we can repeat the march to Berlin!” and “Not a step back!” to form long lines outside the recruitment offices. To walk the talk. To put words into action.

In September 2022, I watched on a TV screen in my Moscow apartment men on bicycles crossing into Georgia and Kazakstan and couldn’t help laughing as I recalled vividly how those same morons dressed in fake military uniforms blocked roads and sidewalks with their stupid cars and bumper stickers that harped on how they all gonna defeat Nazis.

“There are Nazis at the gates! Your hero-dictator had told you! Where are you all running??”

In fact their grandfathers did exactly the same — when Hitler’s army crossed the border into Belarus, Red Army soldiers and officers skedaddled all the way to the outskirts of Moscow occasionally chucking hundreds of thousands of peasants under the well-oiled tracks of the German tanks hoping against all hopes that this would make Hitler change his mind and then burying the corpses in the common grave and later sticking a monument to the Unknown Soldier on top because nobody bothered to learn any names of the soldiers sent on a suicide mission…while leadership in the West from the Pope to Anglo leaders preached appeasement and invited everyone to lay down their guns and conform to the new realities on the ground.

However, to their credit not everyone had tried to skirt responsibilities of self-proclaimed Nazi fighters (although majority had to be baited with generous wages), and there were volunteers who joined the Russian forces to thwart momentum of the Ukrainian army that began to de-occupy swathes of land in the east.

Some of military cosplayers who believed that they fought like their grandfathers got captured. A few of them were deprogrammed and formed the Russian Freedom Legion and the Siberian Battalion with the set goal to change the direction of the march, from Berlin to Moscow!

“To Moscow!” was their new credo. Putin is the new Hitler and he must be defeated. But what flag to hoist on top of a real battle tank? A Soviet one can’t do, naturally.

What about a European Union flag?

A Russian woman woke up this morning and heard the already familiar sounds of thunderous rumblings.

She peered out of the window of her house in Shebekino, Belgorod region that borders Ukraine in the east and to her greatest horror saw a tank with a European Union flag on top.

In the gray hues of sky and bare early spring ground, bright blue fabric stood out like an invitation to a beheading.

“Baby Jesus, Virgin Mary, and Patriarch Killkill!” She exclaimed and crossed herself .

The cross border raid of the Russian freedom fighters fighting on the side of Ukraine followed a pronouncement from Ilya Ponomarev, leader of the Freedom Legion who claimed that if they cross into Russia with 100 troops, they gonna reach Moscow with 100,000 troops next day. So many volunteers would wish to join them!

He referenced the mutiny of Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of the mercenary army. He marched to Moscow from Rostov-on-Don in the south and managed to reach Kaluga, mere hundred miles from Moscow, at which point he stopped and decided not to engage in a battle with the National Guards.

The Russian army didn’t try to stop Prigozhin’s mercenaries at any time, apart from the botched attempt to blow up the convoy by the Air Force warplanes.

Deprogrammed Russian Freedom Legion believed that if the Russians see an EU flag they would think that they are being liberated from Putin’s regime by the good guys, too.

They mixed up narratives. It’s Ukraine that wants to join the EU. Not Russia!

Had Prigozhin hoisted an EU flag on his SUV, his own mercs would have shot him 236 times on the spot. And so the collective madness continues where conflicting narratives jive for attention, credibility and victory.

The winner takes it all. Loser has to fall. ~ Quora

Belgorod

*

PUTIN’S PARANOIA

Putin is very paranoid when it comes to staying in power. But that is an uninteresting fact, despite being decorated by a host of prominent corpses.

It is far more interesting to speculate about national paranoia, which the phrasing of this question invites.

I’m probably going to depart from the expected script here and suggest that there’s very little actual fear of NATO or the Anglo-Saxon Kabal driving Russian foreign policy or resonating deeply with common people. It’s just a story that they’ve all agreed to parrot. Defending against an existential threat hearkens back to the Great Patriotic War and just sounds a whole lot better than ‘reconquering what we used to control.”

More than paranoia, I believe the national character of today’s Russians is constructed on an inferiority complex and fear of becoming an irrelevant (worse, economically subservient) apparition on the world stage. Like China, and like the anti-globalist movements in the West, Russia regards world trade as a zero-sum game, one that it is losing badly.

The solution—go back to what worked before: expansionism at the expense of weaker neighbors. It’s just too bad that this time there’s no power vacuum left after the collapse of an empire like the Mongols or Ottomans. Too bad that the rest of the world has moved on, and has figured out a way to protect sovereign countries, even if smaller. Too bad the former USSR satellites in Europe rushed to join NATO in their correct assessment that history will be repeated.

The reason Russia invaded all of Ukraine is that it viewed its eventual westward pivot as a condemnation of a way of life (which it was), a spurning of a sacred “origin” that can only be explained as a sinister manipulation by the West (it cannot be that our culture, our common roots, our shared destiny, are what is actually being rejected).

I think you probably have to be a Russian with some Ukrainian roots or a Ukrainian with Russian roots to truly appreciate what this bloody conflict is about.

Maybe we can come close if we picture an aging but vicious patriarch in a deeply religious family who wouldn’t mind seeing a young nephew beaten by his enforcers within an inch of his life and dragged back to the village in order to save him from a gay lifestyle in the corrupt, godless city.

In a certain very twisted way, the conflict is more about family than about paranoia.

~ Plamen Arnaudov, Quora

Victor Bennett:

I think you are overlooking the effect of Putin's ego in all of this. Putin appears to be obsessed with his popularity levels in Russia. After he stole Crimea his popularity went sky high but then began to drift downward over time. I think he may have convinced himself that a quick, three week conquest of Ukraine would send his popularity through the roof and he could then bask in the adulation of his adoring peasants.

Christopher Aspen:

Isn't it a bit rich to invade a sovereign nation, all because this nation is inching closer to the “decadent” West and Russian culture in Ukraine is becoming less influential and then expect the world to agree to your reasoning for invading it?

*

“NO PERSON, NO PROBLEM”: SERIAL DEATHS IN THE RUSSIAN OIL INDUSTRY

Vitaly Robertus, vice president of the Russian company LUKoil, suddenly dead “of asphyxia” at the age of 53.

Robertus worked for LUKoil for all his life, joining the company after graduating from the university 30 years ago.

This is the 13th death of a Russian top manager since the beginning of 2022 — almost all of them worked in oil companies.

In LUKoil, it’s already death #5:

1.) May 2022: 44-year-old ex-top manager of LUKoil, billionaire Subbotin, died.

2.) September 2022: 67-year-old head of the board of directors of LUKoil Maganov died (fell from a hospital window).

3.) December 2022: 48-year-old head of one of the major LUKoil subsidiaries, Zatsepin, died.

4.) October 2023: 66-year-old Nekrasov (who replaced Maganov as head of the board of directors of LUKoil), died.

5.) March 2024: 53-year-old vice president of LUKoil Robertus died.

Obviously, it’s purely coincidental that in less than 2 years, 5 top executives of one of the largest oil companies in Russia died.

And it has nothing to do with turf wars among Putin’s “elites”, who are fighting for the shrinking pie of the Russian economy, using the simplest method they know since Stalin’s times: “no person, no problem”. ~ Elena Gold, Quora

Tim Weston:

Except the “person” who is the actual problem is still there, but with absolute, unchecked power. At that time it was Stalin, now it is Putin.

Franz Peter:

Stalinist methods have left their bloody imprint, for sure, and came out of hiding when Poo-tin took over.

Albina Graniute:

I can assure you that none of them is a good person and they all knew exactly what they were getting into when they took the job. Most of them probably have arranged assassinations of their competitors before, or at the very least, have threatened or harmed them in other ways. Nobody gets to be an executive in an oil company in Russia by simply being a competent specialist in the field.

Elena Gold:

They can’t escape Russia and can’t quit their jobs — Putin forbade execs to resign.

Kumar Narain:

Indians bought oil in Indian rupees, ha ha ! So they say. That is all theater to fool the world. Indians paid in dirty dollars too, sitting somewhere.

*

DUNE, PART 2: THE SPACE MUSLIM

Let’s start with a positive review:

~ The word that will likely be used most often to describe Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune: Part Two” is “massive.” Expect a whole lot of variations on the words “epic” and “spectacle” too. Whatever big words you apply to the result, Villeneuve undeniably did not approach Frank Herbert’s beloved sci-fi novel with modest aspirations, and it’s his ambition, along with the top tier of behind-the-scenes craftspeople with whom he collaborated, that have paid off in this superior follow-up to the Oscar-winning 2021 film. While that beloved blockbuster often felt like half a film, “Dune: Part Two” locates significantly higher stakes on Arrakis, while injecting just enough humor and nuanced themes about power and fanaticism to flavor the old-fashioned storytelling. More than a simple savior or chosen one story, “Dune: Part Two” is a robust piece of filmmaking, a reminder that this kind of broad-scale blockbuster can be done with artistry and flair.

“Dune: Part Two” picks up so closely on the heels of the first film that the Fremen are still transporting the body of Jamis (Babs Olusanmokun) home again after he was bested in the fight with Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet). After the massacre of House Atreides, Paul chose to go with the Fremen, much to the consternation of his mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson). Thinking both Paul and Jessica were taken by the desert and all hopped up on violence after destroying the Atreides interlopers, House Harkonnen amplifies its attack on the Fremen, leading to a few remarkably staged battles between the warriors and soldiers.

Villeneuve and his team deftly fill the first hour with battle sequences that counter the firepower of the Harkonnen military and the Fremen tribal combatants, who often literally emerge from the earth to destroy them. Bodies fall from the sky as enormous ships burst into flames in a way that feels nearly operatic. Amidst the chaos, Dave Bautista cannily sketches Rabban Harkonnen as a wartime leader who is in way over his bald head while Stellan Skargard leans even harder into a sort of blend between Nosferatu and Jabba the Hutt.

As the battle between the Fremen and the Harkonnens for control of Arrakis serves as the backdrop for “Dune: Part Two,” Paul’s arc from nervous young man at the beginning of the first film to potential leader plays out in the foreground. A Fremen tribal leader named Stilgar (Javier Bardem) is convinced that Paul Atreides is the chosen one that has been foretold among his people for generations. Even as so much of the mythology points to Paul’s savior role, the Emo King tries to blend into the Fremen, forming a relationship with a young warrior named Chani (Zendaya). Paul passes the tests put in front of him by the Fremen, takes on the tribal name of Muad’Dib, and vows vengeance against the Harkonnens who were behind his father’s death.

On another planet, an Emperor named Shaddam IV (Christopher Walken) counsels with his daughter Irulan (Florence Pugh) and a Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother (Charlotte Rampling) on the state of Arrakis. It’s revealed early on that Shaddam basically sent House Atreides to its destruction, meaning he’s on that vengeance list that Paul’s been keeping, while Irulan serves as a sort-of narrator for “Dune: Part Two,” dictating some of the political developments into a device that’s really designed to keep audiences with the plot.

If the interstellar politics aren’t enough, writers Villeneuve and Jon Spaihts inject +Lady Jessica becomes a powerful religious figure of her own among the Fremen, guiding her son’s ascendance in a manner that feels nefarious and unsettling. “Dune: Part Two” is not a traditional hero’s journey in that it’s constantly questioning if being led by an outsider from another culture is the right move—Chani sure doesn’t think so, and Zendaya subtly finds notes to make viewers wonder what a happy ending would be for these characters. As Jessica and Paul learn more about Fremen history and culture, they threaten not to lead it as much as dismantle and own it. There’s a big difference.

While the plotting in “Part Two” is undeniably richer than the first film, its greatest assets are once again on a craft level. Greig Fraser, who won the Oscar for cinematography the first time, tops his work there with stunning use of color and light. It’s in the manner the sun hits Chalamet’s face at a certain angle or the wildly different palettes that differentiate the Harkonnens and the Fremen.

The browns and blues of the desert culture don’t feel arid as much as grounded and tactile, while the Harkonnen world is so devoid of color that it’s often literally black and white—even what look like fireworks pop like someone throwing colorless paint at a wall. Hans Zimmer’s Oscar-winning score felt a bit overdone to me in the first film, but he smartly differentiates the cultures here, finding more metallic sounds for the cold Harkonnens to balance against the heated score for the Fremen. Finally, the effects and sound design feel denser this time, and the fight choreography reminds one how poorly this has been done in other blockbuster films.

As for performers, Chalamet is likely to be the most divisive element, often feeling a bit flat for someone believed to be the Neo of this world. However, those choices add up in a way that makes thematic sense, enhancing the uncertainty of Paul’s rise. Zendaya is solid—although she lacks chemistry with Chalamet that would have helped—but it’s Ferguson’s slippery performance and Bardem’s playful one that really add flavors here that weren’t in the first outing. Finally, Austin Butler leans hard into the exaggerated role of Feyd-Rautha, playing the sociopathic nephew of the Baron with all the scenery-chewing intensity that a character like this needs to work, finding the emotional void to balance out against Chalamet’s tempestuous inner monologue.

“Dune: Part Two” has been compared to “The Empire Strikes Back” in the run-up to its release, and that’s not quite right. The better comparison is “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers,” another film that built on what we knew about the characters from the first film, added a few new ones, and really amplified a sense of continuous battle and danger. Like both films, a third chapter feels inevitable. Critics will have to come up with a new synonym for massive.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/dune-part-two-movie-review-2024

and then I found this gem:

SPACE MUSLIM VERSUS CRUSADERS

"It has been (accepted) by all Muslims in every epoch, that at the end of time, a man from the family (of the Prophet) will without fail make his appearance, one who will strengthen Islam and make justice triumph," wrote Ibn Khaldun in The Muqqadamiah. "Muslims will follow him, and he will gain domination over the Muslim realm. He will be called the Mahdî."

In the Tunisian-born sociologist, philosopher, and historian's exhaustive 14th-century introduction to the Islamic world of theology, philosophy, ecology, economics, power and politics, there is no escaping just how influential it was on Frank Herbert's original Dune novel series.

The sci-fi series borrows and repurposes many of his observations about civilizations to build an Imperial universe set 20,000 years in the future.

From desert life versus sedentary culture, the rise and fall of dynasties and the diversity of religious practice, Herbert weaved these weighty historical concepts and themes into a sweeping narrative that delivers an epic critique of the Messiah Complex.

In the realm of Dune's Old Imperium, Paul Atreidis is his "Mahdi," albeit a reluctant one.

What's Dune Part Two about?

Having survived the devastating attack on House Atreides by rivals the Harkonnens in Dune — Part One, and the betrayal of Emperor Shaddam IV who supported the overthrow, Paul (Timothee Chalamet) and his mother Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) are forced into the desert and taken in by Fremen leader Stilgar (Javier Bardem).

This is after Paul won a fatal duel against the Fremen Jamis and much of the 2hr 48 minute runtime is dedicated to his and Lady Jessica's assimilation into and ultimate leadership over this nomadic warrior people.

As well as lead a revolt against the usurping Harkonnens and the Emperor to claim control over the planet's spice production – the most valuable substance in the universe.

One of Dune Part Two's successes is how acutely it wrestles with the scheming efforts of the Bene Gesserit and the false idolatry they've for centuries laid the groundwork for.

Jessica's superpowered matriarchal order has spent many generations manipulating the Fremen tribes into believing their invented prophecy of the Kwisatz Haderach (AKA the Mahdi/Lisan Al-Gaib) – an off-worlder who will lead them to their salvation.

Aware of dynastic changes of rule, the Bene Gesserit secure bloodlines of Houses to maintain power in the universe but Jessica's self-serving plans for her first child by the fallen Duke Leto I have positioned Paul into that messianic role; a move that creates friction between mother and son as their paths diverge then realign in the third act.

Ferguson injects some of that Doctor Sleep/Rose the Hat eeriness into her performance; there's an increasingly disturbing glint in Jessica's eye as she becomes Reverend Mother and goes on a holy conversion mission to the South of Arrakis.

The ominous conversations she has with her pre-born daughter (growing in her womb) intensify the weirdness that Ferguson revels in. Searing visions, conversations about faith and divination with the Fremen and arguments with Jessica, lay the groundwork for the tumultuous voyage of the mind, body and soul Paul goes through under the influence of spice that shimmers across the vast desert dunes.

There's a rich interiority of these particular characters and Chalamet compellingly charts Paul's emotional evolution from unwilling savior to pragmatic leader. However, the biggest motivating factor for accepting this destiny is oddly underexpressed.

His relationship with Chani (Zendaya) also comes into clearer focus and the sweet-looking pair suits the somewhat basic YA romance filter applied to it; Paul's attempt to mansplain sand-walking to the Arrakis native raises a smile.

But changes from the book mean there isn't an equal exchange of knowledge between the two that truly cements their affections or the genuine depth of their bond to each other – save for an ambiguous headband that might hint at a key plot point that has been erased from this part of the story.

There's a dearth of character development as to who Chani is beyond a member of the Fedeykin (the Fremen's fearsome guerrilla fighter group), devout to her nation but sceptical of their faith.

In the novel, Liet Kynes is her father with Sharon Duncan-Brewster playing a gender-swapped version of that character; here, there's zero acknowledgement of that relationship. Chani is no damsel-in-distress but Zendaya's ability to connect us to her journey is restrained to a typical strong female characterization throwing a romantic spanner in the works for the male lead.

That superficiality is more widespread in the Fremen cast. Little time is spent in establishing these people and their culture beyond fighting, survival and religious fanaticism.

Little do the group feelings and traditions that make them such a formidable, connected community permeate beyond their Islam-inspired prayer rituals.

The casting of Swiss-Tunisian actress Souhelia Yacoub is a win for Arab representation in a film that restricts actors of MENA heritage to background players.

Playing a gender-swapped version of Fedaykin warrior Shishakli, she's shrewd, funny and delivers the Fremen language (Arabic that has been tweaked for the film) with a fluid ease her castmates don't share. Most of the Fremen accents are all over the place; Chani's American accent is jarring. I guffawed when one Fremen with a Scottish lilt said Mahdi like "mardy".

A nonsensical joke about Stilgar's accent coming from "the South" is a reminder that Bardem is cosplaying as a Bedouin Arab. Bardem offers a warm, frequently humorous performance but mostly at the expense of Stilgar's faith. A faith that makes mentions of Jinn and is depicted through costumes including abayas, hijabs and keffiyehs.

Cultural appropriation aside, there are too many characters to do them justice in a film more focused on the grandiose than the granular motivations of its side players or a more fervent exploration of imperialism and colonialism beyond "good vs bad."

Ferguson's Imazighen facial tattoos and headdresses hit home not just the cultural appropriation of Jessica once she becomes Reverend Mother but the film too. That we are not privy to the secret histories and traditions she has inherited (robbed!) through this ritual is another way the film denies the Fremen a more vigorous depiction.

On the other side of the conflict is the pseudo-European Houses Harkonnen and House Corrino which intensifies the well-trodden Christian vs Muslim themes.

A visit to the brutalist, monochrome world of Baron Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgard) introduces his sadistic nephew Feyd-Rautha, who wouldn't look out of place at Berlin's infamous Berghain [gay] nightclub.

Austin Butler does a decent enough Stellan Skarsgard impression and throws himself into the vicious role. In the Medieval England-inspired pastures of Kaitain, Florence Pugh offers a restrained turn as Princess Irulan while Christopher Walken's Emperor offers none of the playfulness we've long been accustomed to.

Han Zimmer's earthy score of heavy drums and ululating is once again oppressive. Some action sequences are thrilling and stylish; an early Fremen ambush on Harkonnen soldiers is gripping.

A later Fremen attack on a spice harvester in wide shots and intense close-ups is riveting. But the final battle between the Fremen and Outworlders, not to mention between Feyd-Rautha and Paul, feels rushed and anticlimactic.

Sure the main conflict of this book is somewhat resolved but a true resolution is not sufficiently achieved. After spending nearly six hours on Dune Part One and Part Two, I can say I had a better time with the latter. But as a whole, audiences deserve a far more satisfying return on their investment.

https://www.newarab.com/features/dune-2-review-flawed-space-muslims-v-crusades-masterpiece

*

“If you want to control people, you tell them a messiah will come…they’ll wait for centuries . This prophecy is how they enslave us!” ~ Chani

Oriana: DUNE AND THE POWER OF RELIGION

This has finally clarified for me what Dune is about. It’s about the use of religion to manipulate people. Tell them that the Messiah will come and they’ll wait for thousands of years.

Not just centuries, no. Millennia. Generally you need to start indoctrinating at an early age, before the brain has the capacity for critical thinking. But once in a while, adult conversion also happens. Or a cynical opportunism, pretending to believe or even becoming a religious leader, all for the sake of holding on to power.

We talk about the power of love. True. But religious faith colonizes not just the earth and one lifetime, but eternity. Lack of evidence is not a problem. In fact not even the evidence for the opposite position is a problem. When Paul at first denies that he is the Messiah, it is taken as as proof of his great humility. He is so humble that he must be the Messiah — “as written.”

The unholy marriage of religion and political power goes back not centuries, but millennia. Think of ancient Egypt.

Karl Marx wrote about religion as a drug that keeps people subservient, but provided no solution. Historians saw it, great writers saw it — but there seems to be no solution. Humans have deep emotional needs, needs that will be satisfied in one way or another, no matter how destructive to self and others.

Yes, religion is in decline, but it will never disappear completely. There are those who simply must have it. And, as has been pointed out many times, an ideology such as fascism or communism has many characteristics of religion. Above all, you need to induce a climate of threat while all the time making attractive promises.

“A specter is haunting Europe — the specter of communism.” But the ground has been prepared by religion.

*

The first "Dune" was fun; the follow-up no longer has the element of surprise and falls flat as a desert mouse getting steamrollered by a giant sand worm. ~ Mark Jackson, Epoch Times

GIANT SOLAR FARMS COULD CREATE THEIR OWN WEATHER

In the United Arab Emirates, water is more valuable than oil. To support the needs of its desert-dwelling residents, the UAE relies on expensive desalination plants and campaigns of cloud seeding from aircraft, which spray particles into passing clouds to trigger rainfall.

But according to a new modeling study, there may be another way to stir up a rainmaker: with city-size solar farms that create their own weather.

The heat from large expanses of dark solar panels can cause updrafts that, in the right conditions, lead to rainstorms, providing water for tens of thousands of people. “Some solar farms are getting up to the right size right now,” says Oliver Branch, a climate scientist at the University of Hohenheim who led the work, published last week in the journal Earth System Dynamics. “Maybe it’s not science fiction that we can produce this effect.”

Branch works in an emerging field that studies how renewable energy, a key response to climate change, can in turn alter regional weather patterns. In a 2020 study, researchers found that implausibly large solar farms, taking up more than 1 million square kilometers in the Sahara desert, could boost local rainfall and cause vegetation to flourish. But the bounty would come with a cost, the researchers found: By altering wind patterns, the solar farms would push tropical rain bands north. “If you push those northward, that’s not good news for the Amazon,” says Zhengyao Lu, a climate scientist at Lund University and lead author of the 2020 study.

Branch and his co-authors wanted to see whether solar farms of more realistic sizes could alter the weather. To do so, they turned to a leading weather model, produced by the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research, that can account for land surface changes. They modeled the solar farms as nearly black fields that absorbed 95% of the incoming sunlight. When the solar farms exceeded 15 square kilometers, they found, the increased heat absorbed at the surface, contrasted with the relatively reflective sand surrounding them, appreciably increased the updrafts, or convection, that drive cloud formation.

Just hacking convection wasn’t enough, however: A source of atmospheric moisture is also needed. The model showed that moist, high-altitude winds from the Persian Gulf would suffice. When conditions were ripe, the model found, a 20-square-kilometer solar field would increase rainfall by nearly 600,000 cubic meters—equivalent to 1 centimeter of rain falling across an area the size of Manhattan. If such rainstorms occurred 10 times in one summer, they would provide enough water to support more than 30,000 people for a year.

The new work makes sense, and it’s “very stimulating,” Lu says. “They are targeting a real solution.” One concern, however, is that the simulated solar panels were darker than most manufacturers make them. Some current solar panels are even reflective, designed to cool their surroundings, Lu says.

Still, Branch is hopeful that the idea could at some point be tested in the real world. Solar farms coming online in China and elsewhere are nearly big enough, he says. If they were built in the right spots, it wouldn’t take much to darken the panels as much as possible, and to plant drought-tolerant darkening crops, such as jojoba shrubs, between panel rows.

The UAE funded Branch’s modeling, but whether it will try the scheme in the real world remains to be seen. The country “is committed to study the potential implementation of all robust strategies, such as optimizing convection,” says Alya Al Mazrouei, director of the UAE’s Research Program for Rain Enhancement Science.

But she adds that for now, the country is deeply committed to its cloud seeding program, carrying out some 300 missions each year.

Branch and his colleagues have identified other areas of the world where the scheme might work, such as Namibia and Mexico’s Baja Peninsula. They’re also trying to improve the realism of their model’s solar panel simulations by cross-checking them with field measurements at existing solar farms. Ultimately, he’s hopeful that the rainmaking potential of solar farms will encourage more construction. “If you can provide evidence that a huge solar farm produces rainfall,” he says, “that might give impetus to increase the size of them.” ~

Solar Farm in UAE*

WHY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS SAW MOTHER TERESA AS A FRAUD

From one associate of an Indian Buddhist center:

An anecdote I tell whenever this comes up. When Teresa was still alive I was studying at a Vipassana meditation center in India when I met a young and idealistic Catholic nurse from Ireland.

She had volunteered to work at the hospice in Calcutta. but had left a few weeks later, shaken and appalled. She had been taken aback by the squalid conditions, the unhygienic needles, the lack of pain control, and the willful withholding of the most basic medical treatments. And when she met Teresa, she found her cold and uncompassionate. But the breaking point had been when they refused to give potentially life-saving treatment to a child.

By her account, they were buying conversions in return for giving the destitute and desperate a few mouthfuls of food. Once their eternal souls had been “saved” they had little interest in helping their human bodies… Indeed, they seemed to believe that the greater the suffering, the greater the spiritual benefit for their patients. She called it a death cult.

Naturally this is all in the context of the $100+ million that the order was hiding in secretive bank accounts around the world. In contrast to the patients, the nuns were very well looked after.

She was so disillusioned with the Church that she had come to the meditation center in search of a more wholesome path to follow in life. ~ Wolfgang Waas, Quora

Boo:

Apparently Mother Teresa thought it was beneficial to the human “soul” to SUFFER. So even though people would be dying of cancer, (and medications HAD been donated to her), she wouldn’t give the medications because…it’s good for your soul to suffer…

Peter Foulds:

When she got sick she was treated by the best money could buy. (Oriana: I was told that one of the medical facilities where she got treatment was UCLA Hospital.)

Tony Barry:

I also met doctors and nurses in Calcutta while Mother Teresa was alive (back in 1986). Many of these medicos were also Catholic.

Their experience was often harrowing (as your Irish nurse recounted). They found Kalighat (the home for the dying) to be an enormous hurdle to get over, as with Shishu Bhavan (the children’s home). The disparity between standard patient care in the West vs Calcutta, caused great distress to many people who had trained in medicine in the West.

But most of the doctors and nurses, while painfully aware of the desperate mess around them, did not lose the plot. These were the medicos who managed the situation, who worked with what was available, and made it work for good. I learned so much from these guys.

I was lucky — I had no medical exposure (just an electrical engineering background), was / am somewhat autistic, and being one of the Born Again made me quite unaware of the visceral nature of the desperation of Kalighat.

I was not excessively stupid, but it took a fair while for me to see what might have been going on — why some of the medicos did lose the plot; who railed against the Catholic church, Mother Teresa, the MC sisters and brothers … and why others did not.

From an engineering viewpoint, it can be seen as a gain — stability amplifier problem.

And although people are not amplifiers, for everyone Kalighat was a perturbation of enormous proportions. Some folk had better methods to deal with the affront, and some folk were overwhelmed.

They often externalized the chaos as a survival method, to deal with it before it wiped them out. The nearest handy items to externalize the focus on were the MC sisters and brothers. Then MT. Then the Catholic church. It was the their problem. And their behavior. And their heartlessness. And the fact that they continued to do what they could despite the fact that — for so many of the destitute — there was no hope.

I get it. It was more than forty years ago, and I can still see these decent, honest, kind medicos having a head crash at some awful example of man’s inhumanity to man. Not an active evil … just a sad reflection that there were too many poor people to help.

But what of the others? who were rocked but continued to function? Well, here is where I can offer some insight. You see, I was one of those guys who cracked during my time in Calcutta. It wasn’t a medical thing that broke my amp, because I was medically clueless. Ignorance is bliss, and a very handy thing at times.

For me it was a roadside distribution board near Sudder St in Calcutta’s tourist district, meant to offer a place where electrical supply can be routed to a submains. I walked past it and the doors were ajar … and inside, the busbars were glowing. Not dull red, but that nice cherry red which you get just before liquefaction. And explosion.

I shit myself. My companions at the time (two excellent guys from Britain) kind of laughed at my reaction, but did not understand why I was bouncing around. I tried to explain, and they just said, OK, let’s just move on.

And I moved on. It was too hard to get anyone to fix the problem. I did not speak the language (Bengali). I did not know who to speak to; and as my mates said, this happens every day in Calcutta, the power is only one half the time and it’s way overloaded.

I felt the same hopelessness as the nice Irish nurse. And it’s really not good. The place is absolutely fucked. I can’t do anything to unfuck it. It’s a disaster. The medicos see their humanitarian disaster. I see this engineering disaster. Everyone who turns up at this shithole sees their own version of whatever their disaster specialty is.

And the crazy thing is that MT started giving cups of cold water to dying people in this dump, and we who were there saw it as a futile gesture of compassion that wasn’t futile at all. It was the stuff of legends. Because in that hopelessness, love still works. Even when it doesn’t.

That’s why MT got the Nobel Prize. And that’s why the nice Irish nurse hates Catholicism.

It all comes down to amplifier instability near the supply rails. Some of us survive, and some don’t.

Joseph George:

A majority of Indian nuns in Mother Theresa's order were from well to do families who joined her out of idealism and missionary zeal. That the mother was a religious fundamentalist and a zealot and that her ultimate aim was conversion of Indians to her church and making money for her church, is a fact. In this way she was evil.

Ian Babineau:

She was raising millions for the Chatholic church (the richest organization in the world), and giving a tiny percentage to those she used as publicity for her fundraising.

If you look at that and say “at least she was giving them something”, I think you are getting the wrong message.

I feel if she told people “2% of your donations will go to help starving children and 98% will go to the richest organization in the world” many of them would have donated to another charity.

Jo M:

This is all well documented and appalling. In India in the 80s I met people who'd volunteered and left quickly for similar reasons. Squalor, lack of any kind of medical treatment etc.

Lee H. Christof:

This is true of almost all popular culture saints like Mandela, MLK and Gandhi. The truth is way different than the way they are portrayed by historians and the media.

*

THE PREDICTED DECLINE OF ISLAM

~ In a hundred years, Islam’s empire of conformity will have crumbled. It is already starting.

Mecca will still be a holy place, and the hajj will still be a thing — but atheism will continue its rise in Muslim countries; women will demand equality; and imams will find it harder and harder to raise crowds of mindless rioters and murderers for Allah.

We are a couple generations from the tipping point, but it is coming.

Poor backward Muslim places like Afghanistan and Somalia will remain poor and backward and Muslim — but Cairo and Jeddah and Jakarta will be converting their mosques to condos.

A race is on: will Islam conquer the west or will the west conquer Islam? My belief is: Islam makes noise and commits hate crimes and has a coercive community structure, so it gains some influence in the west that way — but all the screaming imams have less potency than the western ideas being exported into Muslim nations. ~ Angeli Adeen, Quora

Baruch Cohen:

Maybe Islam Reformation is on the horizon? It s time to change from the 7th century ideals to something more in conformity with reality.

Steve Dutch:

I’d love to believe this, but Islam is not the problem. The culture is. The male misogyny and obsession with female sexualty is really fear of emasculation.

Young Muslims don’t need to be killing Israelis and Westerners. They need to kill their imams and family elders. Those are the people who are really oppressing them.

Angeli Adeen:

Agreed.

Islam is just seventh-century Arab tribal beliefs dipped in Jewish and Christian myths. With “Allah” to unite them and Mohammed/Quran to anchor them firmly to the seventh century, they have not budged in centuries.

But now there are new forces at work in Muslim countries:

Modern Western ideas, including atheism and female equality. These are spread by the internet and Hollywood and migration.

Reaction against modern Western ideas: the Old Guard cracking down.

The modern Arab construct of “We are divinely-appointed conquerors and we are superior to all — but Oh! Woe! we are victims!! Victims of the Zionists and Crusader West and White racists who deny us our place at the top of the food chain.. Conquer the West, for Muslim pride!” This has been embraced by some of the youth.

The desire of dictators to wield Islam as a uniting force for their people, while also suppressing Islamist movements that threaten their power.

How it will all shake out is unclear. BUT: if you google atheism in Arab countries (as measured by confidential surveys, since atheists are not safe to speak up), the number is slowly rising and is now about 5 percent. I consider this the tip of a wedge that is slowly getting thrust into Muslim countries, like a wedge into a log. Eventually the wedge will shatter Islam’s violent coercive hold in some of these countries — and out will pour the long-suppressed voices of loud proud irreligious people who have too strong a voice to continue being silenced with threats and murders.

To mix my metaphors: some Muslim nations are pressure-cookers, with a slow-building pressure to abandon the seventh century — and only the locked lid above (societal and government control) and the danger below (death threats and murders by local Muslim terrorists) are keeping the pot from blowing up. That is not a situation that can last forever.

Obelix:

Social media is killing this outdated stupid religion.

George Dunn:

But that's the major thing the imams are screaming about: the insidious advance of Western values weakening their medieval authority.

At bottom, every jihadi atrocity is an attempt to hold back the tide of reform.

Curtis Morgan:

Christianity looked solid 100 years ago.

What guarantee does Islam have which Christianity did not have?

*

WHY MEMORY IS MORE ABOUT YOUR THE FUTURE THAN YOUR PAST

~ Whenever we remember something, we alter that memory with our needs, beliefs, and perspectives.

According to neuroscientist Charan Ranganath, this and other aspects of how memory works keeps our thinking nimble and flexible.

If we want to keep our memories more vivid, we should pay attention to what makes them distinctive.

Certainly it would be better if our memories were a perfect record of everything we encountered, right? Not necessarily. According to Charan Ranganath, neuroscientist and the author of Why We Remember, humans evolved the memory system we did because it helps us stay attentive to what is important.

Big Think recently spoke with Ranganath to discuss how memories form, how they help keep our thinking quick, and what we can do to connect more with the memories that matter most to us.

Big Think: What’s wrong with the common assumption that memory is a recording stored in the brain?

Ranganath: Although it’s understandable that so many have that assumption, there are a few things off with it. The first thing is that we’re supposed to remember everything. The second is that when we remember, it’s an exact replay of what happened. Neither of those is true scientifically.

People retain only a fraction of the experiences they have. That’s true of everyone I know of who has been quantitatively studied. People also embellish their memories. They can distort them; they can make inferences.

I always say my phone has a photographic memory. I store lots of photos on it, I rarely go back to them, and if I want a particular one, I spend a long time searching for it. [Conversely], the brain is about quality over quantity. It’s designed to carry what you need so that you can be nimble and agile and find what you need when you need it.

Big Think: How do we alter memories when we remember?

Ranganath: There are two schools of thought. One school is that you form a new memory when you are remembering. The other school is that you actually alter the original memory. It doesn’t really matter which explanation is correct, subjectively speaking. The act of remembering changes the way you’ll remember an event later on.

In neurobiology, people talk about a phenomenon called reconsolidation. After a memory is activated, there are all of these chemical changes that effectively make the memory more vulnerable — that is, the connections between the neurons that help bring that memory to life become a bit unstable. Things can happen that can alter that memory at that point.

We can see this when remembering past events. When we tell the same memory over and over, it becomes less detailed and more rote. It reflects a kind of story rather than a re-imagining of what happened.

Big Think: How does imagination play a part in memory embellishment?