*

SEVEN GERMANS

told to my mother by a stranger on the train, 1945

Her husband’s broken body thrust

against the electric fence.

She dressed in black, lit a candle

in church, and swore:

seven Germans, by her own hand.

The days grew. The caw of crows

rang in hoarse, nagging echoes.

One afternoon, a knock on her door:

two German soldiers in retreat,

walking without food, without sleep.

She let them in.

They slumped down in the chairs.

Frost lilies shrouded the windows.

In the bedroom, a loaded revolver

pressed cold steel into slips and brassieres.

She stared at their frost-red, fear-eaten

young boys’ faces, flecks of snow

on coats and hair —

then turned toward

the kitchen, and made them tea.

They cupped numb fingers

around the porcelain

and swallowed sips of heat.

A salvo of shooting

ricocheted far-off in the street —

She touched her hand to her mouth.

They nodded and hurried out,

turning into footsteps, then silence.

Sunday, she wanted to light

two more candles, two draft-torn

hearts of flame, but didn’t dare.

~ Oriana

*

THOMAS HARDY: GREAT CHARACTERS DON’T NEED A BACK STORY

I loved Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge from page one. The first three paragraphs alone still make me want to applaud with my hands above my head, like I do when my team take to the field. Exactly 40 years since my O-level English literature exam (passed, with a grade A, since you ask), I decided to re-read it. Some passages feel as familiar as my name and address, while others – concerning the plot, mainly – ring no bells at all. Weird.

I loved it all over again, although one aspect nagged away throughout: the absence of any explanation as to why characters are as they are. Take Michael Henchard [the protagonist of The Mayor of Casterbridge], who is angry, selfish and cruel, but also capable of great kindness and, tormented by guilt and remorse, isn’t lacking in the self-awareness department. I find that my 21st-century self asks questions my 20th-century self didn’t – answers to which the 19th-century author apparently felt no obligation to supply. Why is Henchard this way? What made him so mad and bad most of the time? What made Donald Farfrae so clever and kind?

Today, sure as anything, a writer would be bound to offer some kind of explanation. Not to do so might be deemed lazy – a cop out. If no origin story is supplied, the character might even be regarded as one-dimensional. Hence, we see the likes of Tony Soprano (bad guy) and Ted Lasso (good guy) in therapy, laying out their origin stories in some detail. Poor Michael Henchard never got this opportunity. His behavior would be pathologized to hell and back. It must have been nice for Hardy to be able to devote his literary energies to creating complex characters without getting bogged down in backstories.

There’s a TV series in here somewhere: Great Characters in Fiction – in Therapy. Season one to feature Michael Henchard, Iago, Becky Sharp, Anna Karenina and all of the Famous Five, including Timmy the dog.

Now, in real life and on the page, we are almost impelled to investigate why we are like we are, and why everyone else is like they are. Done something terrible? There must be a reason that goes back a long way. These lines of inquiry probably come from a good place and are generally healthy, but there needs to be a line somewhere. People are often just plain good, plain bad or plain indifferent, in varying degrees of complexity. Just let them be.

If you’ve got the funds, you can spend a lifetime in therapy looking backwards in an effort to find a way forward. This has its place, but if we’re not careful we’ll be mulling over our pasts to make sense of our futures until the very moment the future stops dead as we’re lowered into our graves.

Sorry to end on such a grim note there. Been reading too much Hardy. ~

~ from the opening of The Mayor of Casterbridge, paragraphs 4 and 5

The chief—almost the only—attraction of the young woman’s face was its mobility. When she looked down sideways to the girl she became pretty, and even handsome, particularly that in the action her features caught slantwise the rays of the strongly coloured sun, which made transparencies of her eyelids and nostrils and set fire on her lips. When she plodded on in the shade of the hedge, silently thinking, she had the hard, half-apathetic expression of one who deems anything possible at the hands of Time and Chance except, perhaps, fair play. The first phase was the work of Nature, the second probably of civilization.

That the man and woman were husband and wife, and the parents of the girl in arms there could be little doubt. No other than such relationship would have accounted for the atmosphere of stale familiarity which the trio carried along with them like a nimbus as they moved down the road.

*

WHEN DEMOGRAPHICS AREN’T DESTINY

Most people falsely believe positive outlooks indicate privileged backgrounds.

Many people today are realizing how demographics—such as sex, income, neighborhood affluence, and crime—can shape success and happiness. This awakening is a positive step. Yet a new study also reveals a major way that demographics are not destiny, contradicting what hundreds of researchers, including my own research team, predicted.

PRIMAL WORLD BELIEFS

People hold beliefs about all sorts of things, from politics to family and more. Since 2019, psychologists have studied a special type that researchers call primal world beliefs, or “primals” for short. Primals describe people’s most basic beliefs about the character of the world as, essentially, one whole, huge place.

People have lots of different primals. Take a hundred people on the street and you’re bound to find some who view the world as safe and some who see it as a battleground (that's one dimension of primals, called "safe world belief"). Similarly, some will consider it a barren desert and others think the world is overflowing with abundance (that's "abundant world belief"). Researchers know of 26 dimensions. Most boil down to the belief that the world is usually a good, wondrous place or a bad, miserable place.

Primals matter. A 2022 study showed that positive primals are strongly correlated to many positive outcomes, including well-being (which correlated at around .60, the same correlation as that between Earth's surface temperature and distance from the equator). Much existing theory (like that underlying cognitive behavioral therapy) suggests a chunk of this covariation is causal, and research exploring that possibility continues.

Yet we wondered: Could living an easy, privileged life drive both positive outcomes and positive primals?

Maybe positive worldviews are super great for the rich, for men, and for healthy folks living in safe and wealthy neighborhoods and strolling through life trauma-free, but not for the less privileged among us. To paraphrase a study subject: "I wish I could see the world as abundant, but I grew up poor, and that's just not in the cards for folks like me.”

If primals are indeed mirrors that reflect our backgrounds then, if I know your primals, I know your background. Maybe people who see the world as abundant, for example, have truly experienced more abundance, and people who see the world as more dangerous have been through more danger, etc.

So we ran another set of studies, recently published in the Journal of Personality, exploring the connection between primals and privilege.

We started by asking about 500 professional psychologists and about 500 non-academics to predict the strength of 12 correlational relationships between specific primals and specific indicators of privilege (not including race, unfortunately, due to potential confounds, but that is also being looked into).

They predicted substantial relationships. For example, they thought that men should see the world as much safer than women; people in high-crime neighborhoods should see the world as more dangerous; poor people should see the world as more barren; residents of rich neighborhoods should see the world as more abundant; and so forth.

Then, we ran several large studies (involving ~14,500 people) to determine actual relationships.

THE RESULTS WERE A BIG SURPRISE

Not one prediction was correct or even close. The prediction that was least wrong was 3.5 times bigger than the actual relationship.

Because we were so surprised, we did another study of ~1,000 more people finding, for instance, that even people suffering from terrible illnesses (cancer and cystic fibrosis) didn't see the world more negatively (bad, dangerous, or unjust) compared to control groups.

Just knowing the correlation between primals and privilege is unsatisfactory. A deeper understanding will require longitudinal and experimental research.

Yet a reasonable takeaway is that making life more abundant is unlikely to greatly increase abundant world belief, making life safer likely won't greatly increase safe world belief, and so forth. This is consistent with another study that showed that when the pandemic made the world objectively more dangerous, dangerous world belief did not go up.

But the much bigger takeaway here is the big and consistent gulf between prediction and reality. When it comes to primals, we thought demographics would be destiny, and we were wrong.

For me, this study hammered home the point that humans are really bad at guessing people's primals. Past research shows, for instance, that intuitions can be wrong about the primals of successful people and the primals that separate the political left from the right.

This means if you do learn someone's primals, you can't assume much about their background. For example, if I see the world as more dangerous than you, it'd be reductive and wrong to assume that's because I've experienced more danger than you.

Many of us are wrong about where our own primals come from. We tell ourselves stories—that we see the world like we do because of our experiences of poverty, etc.— that can't all be true.

This means that seeing the world negatively out of a sense of solidarity with those less fortunate might be misguided.

THE GOOD NEWS

Maybe we aren’t stuck. These findings do not mean primals can’t change. It only means that many experiences outside of our control likely don't shape our primals in an inevitable, reductive way.

For instance, my research team is exploring possibilities that (a) the things we pay attention to and (b) exposure to people in our lives with very different primals can shape primals. But whatever determines our primals appears to transcend the indicators of privilege and hardship measured in this study.

Considering the well-established link between positive primals and well-being, it’s a good thing. For many of us, viewing the world more positively may not be out of reach.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/primal-world-beliefs-unpacked/202312/when-demographics-arent-destiny

Oriana:

My mother was a die-hard optimist. My father was a devout pessimist. They came from comparable backgrounds, giving me an early hint that you can’t generalize based on gender or income, for instance.

*

THE PALESTINIANS HAVE A PROBLEM . . .

They have lousy leaders.

In the 70’s, Arafat thought that if the PLO launched enough terror attacks, the Israelis would just leave. That was stupid and contained a gross misunderstanding of our nature.

After the Oslo Accords were signed, the Palestinians launched murderous terror attacks, and Arafat did nothing to stop them, as far as I know. Which derailed the accords and helped get Netanyahu elected.

Abbas, who I think is better than Arafat and tried to attain statehood by nonviolent means, is (allegedly) corrupt and a dictator and the people hate him.

Hamas sent their people to commit horrible atrocities on over a thousand Israelis. As a result much of Gaza is rubble and the Palestinians are nearing real humanitarian disaster.

~ Judy Kupferman (lives in Tel Aviv), Quora

Mike Leadsome:

If the people of Gaza don’t want to live in a war zone then they shouldn’t attack the strongest military power in the region!

Ultra Violet:

Thank you Israel! They do the world a service to strike back with deliberate force and decimate the area. I hope the land can usurped, secured, farmed and settled. Gaza should no longer belong to this “country” of drifter Arabs producing gang raping massacres. Israel should get to widen/lengthen their borders by absorbing the rubbled wasteland for their own.

Alter Bar:

The rapists and murderers should be destroyed. If they don't care about their land it should be reduced to rubble. Since no country wants that wretched people who teach their children hate and violence they will stay in the area and they will be taught lessons until they become civilized. They have no other choice.

Oriana:

I just watched a youtube when a former Israeli soldier describes how raids are conducted. (In paraphrase) “You don’t enter through the door because it might be booby-trapped. You throw a racket at the wall to make a big hole, and enter. You see stuff like family photos, and that can make you feel weird.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n0KKHIS9D7I

*

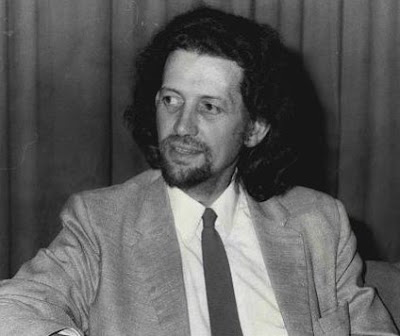

MALCOLM CALDWELL: AN EXAMPLE OF A USEFUL IDIOT

Caldwell is one of the finest examples of a “useful idiot” one could ever think of — a man of books, dedicated fiercely to the people’s revolution. This bookish academic professor was one of the staunchest defenders of the Pol Pot regime. He tried to downplay reports of mass executions by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and was widely criticized by his own country and other academics. He would eventually, in 1978, fly to Cambodia to meet with his hero, Pol Pot, in person…

On 22 December, 1978, Caldwell had a private audience with Pol Pot. Just a few hours later, one hour past midnight, the Scottish intellectual was shot dead in his room. What did he say to Pol Pot, who did he insult, what terrible faux-pas did the Khmer Rouge’s biggest Western fanboy make? We’ll never know. But it did teach us a lesson — if your hero is a genocidal maniac, don’t meet him.

Paul Jones:

Considering Cambodians were systematically murdered for wearing spectacles because they looked intellectual, I imagine Caldwells bookishness and academic leanings were an automatic death sentence.

Borat:

There are useful idiots in every country . For example here in India we have university professors who call Taliban peace activists, freedom fighters and innocents. I have seen the Taliban very closely in 90s Kashmir and i can assure you they are none of that.

Jean-Marie Valheur:

It’s always people who have very little exposure to evil beyond what they’ve read on the internet or heard from second-hand sources. I wouldn’t be surprised if Mr. Caldwell was incredibly shocked, too, when he actually saw Cambodia and met Pol Pot. I wonder if he died a “true believer” or if he grew a spine in his final hours, spoke up and got killed for it…

Oreste Papadopol:

From what I see, Malcolm Caldwell was from the middle class: intellectual, higher education, enough money to travel to Cambodia… that’s a death sentence in Pol Pot’s Cambodia. So not for what he said he was executed but for which social class he was in. That’s what I immediately thought when half way reading the answer. You can meet your hero if your profile doesn’t fit your hero’s enemy. If you’re a Jew, don’t go meet Hitler either.

Cedric Coe:

These types still exist in the West in abundance. They were the one's who would open the gates of Troy, despite knowing what was inside the wooden horse; the kind that gave away the secret location of Hereward’s rebel army;

useful idiots everywhere, tying themselves heart and soul to every cause not their own that actively fights against them and their interests.

[Hereward the Wake: leader of Anglo-Saxon resistance against the invading Normans.]

Matt Bricker:

Prof. Caldwell and the wokesters recognize that their society could be so much better. They lack the perspective to understand that it could also be so much worse.

Diego Velasco de Armas:

He went from "useful idiot" to just "idiot" pretty quickly!

*

RUSSIA TODAY: STANDING IN LINE FOR CHEAPER EGGS

The line to buy eggs.

~ Russians are queuing to buy eggs — standing in the queues, outside, in freezing winter temperatures.

In different Russian cities. Sometimes, they queue before the dawn, in the dark.

Not because there are no eggs in the stores.

They are standing for hours in the queues, because they can save $1 on buying the eggs cheaper than in the store.

The happy faces of those who managed to get cheaper eggs.

The eggs in the market are sold for under $1 for 10 eggs (in Russia, eggs are sold by tens, not dozens).

The eggs in the stores cost $2.20-$8 (some brands are more expensive) for 10 eggs.

The current queues to buy eggs in Russia are not about shortages and not about sanctions.

These queues are about poverty.

About the fact that the majority of Russians still live in deep and hopeless poverty.

What kind of person would freeze in line for hours at dawn just to buy 20 eggs and save $1?

A poor person.

People who live reasonably well wouldn’t be torturing themselves for $1.

The queues that we see are the queues of misery.

These are the queues of those for whom 100-200 rubles ($1–2) is a significant amount of money.

And there are tens of millions of these penniless people live in the “great superpower” of Russia.

But beside poverty, there is another important point.

If you talk to people in those lines, many of them will quite sincerely assure you that Russia is a great country.

The penniless folk are still sincerely convinced that the greatness of a country is measured by the size of its territory and the amount of deadly weapons.

Even more, they sincerely believe that for the greatness of the country, their own well-being can and even should be sacrificed.

“The main thing is that the world fears us, and we the people can endure.”

Over the centuries, these people didn’t understand that the only measure of greatness of a country is the well-being of the ordinary people who live there.

And because they don’t understand it, they resignedly keep standing in queues to buy eggs — for the sake of saving 100 rubles. ~ Elena Gold, Quora

Jonathan Rafalski:

100 rubles for them is like 100 dollars for you, it’s significant.

*

DIMA VOROBIEV ON THE PARADOXES OF COMMUNISM

Communism struggles with the remarkable fact that this collectivist ideology only seems to work for people who believe in individual salvation and personal responsibility.

Communism is basically two things:

No private property. You share with other people the tools, land, trees, ideas, cars, works of art that make your living.

You contribute to the common pot what you can. You get out of the pot what you need.

The idea sprang from Christian monasteries. Monks worked in silence and, amid the prayers, had plenty of time to introspect. Many came to ask themselves and everyone around: why can’t the whole of humanity live the same pious, quiet, and spiritual lifestyle as us? There will be no wars, no angry people, no famines, no suffering.

Scientific Communism

Then came Marxists with a very practical answer: we can make it work if we mandate everyone to give up their private property. Everyone will work for everyone’s salvation. To top it, no one will need to die to get Communist salvation. It will all happen in this world, not the next one!

In the 20th century, Communists managed to organize themselves and grab power across much of the world. They met much resistance but ultimately overcame it. The largest and the most populous countries in the world even became a clear and present danger to the most prosperous and strong Capitalist countries. The bourgeois scum got the scare of their lives!

Selfishness pays

One problem kept popping up. Humans are shaped by evolution to be a bunch of lazy, selfish, sneaky predators. It takes the fear of pain, starvation, and death to get us off our idle behinds and make ourselves useful. There is also a tiny minority of people who are driven by curiosity, vanity, and the desire to make a difference. But they are a maddeningly selfish bunch, too. They prefer to do their own stuff and object strongly when other people tell them what to do.

There’s also a powerful, unselfish thing called love. It can do wonders and prevail over everything. But the unselfishness of love makes it the most dangerous enemy of Communism: people eagerly sacrifice the common good for their kids, their lovers, their family, and their friends.

God or perdition

What on Earth can trump our (1) selfishness, greed, laziness, and (2) our loyalty to our loved ones?

There's only one thing that seems to be able to do that. It’s the love of God and faith in individual salvation.

This is what the tale of Abraham and the sacrifice of Isaac is about. For us common people, this means: God is willing to give us individual salvation if we are ready to betray our loved ones for Him. (In the USSR, we had a Communist rendition of Abraham’s Test: “Who do you love more, Soviet rule or your Dad?”)

Enforcement

The history of Communism shows that Marx's idea of the ideal society requires a degree of individual discipline and self-policing that no totalitarian society can ensure. You need a community of people who are obsessed with individual responsibility in the face of God. If you start mixing these pious creatures with lazybones, creeps, and men/women in love with each other, the latter ones get a ginormous unfair advantage. They will be piggybacking, leeching, and stealing for themselves wherever possible, while the self-sacrificing dimwits will be busting their backs to make everyone’s life better.

You may, of course, put the police, worker’s watchers, KGB operatives, and neighbor informants on the task of enforcing Communist morals. What happens next is the lazybones, leeches, and thieves use every trick in the book to become the enforcers. This is exactly what happened everywhere, from Soviet Russia through the Red Khmer’s Kampuchea to the Chavista Venezuela.

Conclusion

The upshot to the story: you may make Communism work, in some places, for some time. To achieve that, you need

People who believe in individual responsibility before God or History

A wall between them and people who don’t believe in God/History

Preferential arrangements from the government in terms of property protection and economic incentives. On even terms, greedy people always outcompete selfless people.

*

Below, a group of Soviet militzionéry (“police”) in Soviet Ukraine in the late 1940s who take a field tour through their precinct. The recurring feature of all Communist projects was the omnipresence of well-armed enforcers. Someone must keep oversight over the poorly disciplined, ideologically wobbly, insufficiently unselfish millions of builders of Communism.

Soviet enforcers in Ukraine

Oriana:

The history of communism in various countries is strangely similar in that it takes coercion to establish a radically new economic and social order. As for monastic communities, I suspect they also use coercion and mind control of a somewhat different and perhaps more terrifying sort: every minute of your daily schedule is prescribed — as is the way you dress (regardless of whether it's summer or winter), the way you address other sisters and the Mother Superior, what you do, where you sit or stand or kneel, what you eat, and so on. Nuns' headgear was meant to be like blinders on a horse: to prevent these women from glancing about and seeing a bit of the world as they walk. That's called the "discipline of the eyes."

*

ALEXEI NAVALNY WRITES FROM PRISON (allegedly; this appeared on Facebook)

December 6, 2023

Prison is the best place to improve your stamina. Here they are constantly trying to annoy you and piss you off in ways that are both sophisticated and so straightforward and stupid that it's sometimes hard not to get angry.

I told you that I have been trying to go to the dentist for a year and a half. At the new trial, I told both the judge and the prison officials: "Let's solve this issue humanely, stop torturing me, I just need to see a doctor.”

The representatives of the colony, surprisingly to me, said right in the process: "You have already collected so many documents, you just need to write one more application and everything is fine.”

Well, okay. I said to the lawyers: "Please write me a statement, and I'll give it to them. "(The statement is large, with lots of attachments, you just can't write it yourself).

The lawyer wrote a statement and gave it to me via our administration.

And then I was waiting for a while...and nothing. I asked the prison guards:

Where is my application for a medical appointment?

Withdrawn by the censors as containing signs of a crime.

And you know, they look at you with such attentive, shining eyes, like a meerkat in all these wildlife TV programs. Let's see: how is he gonna react? Will he yell? Will he get desperate? Will he complain? Will he accept it and begin to be submissive?

And every single day they come up with some bullshit like this to piss off the rebellious prisoner and test his strength.

Now, by the way, 100% of the letters coming from lawyers are withdrawn by the censors as "criminal", so I can't get a single legal document.

I've been working on my inner zen for three years now to just shrug my shoulders in response to all this. In general, I can say that I have already made good progress along this zen path, but I am still far from perfection. Otherwise, I would not be dragged periodically around the prison zone with my hands twisted behind my back.

But after all, every person should have a psychological release.

Photos: Navalny with a guard, and Navalny's most recent photo (2023)

https://www.facebook.com/navalny/posts/pfbid0332ZZurz2RTqNbtSfsB2Ae49JHsc73G9iLv6vFR4uaUorZTZoZP3pNVAHqg1MUspyl

*

As

a consequence of low fertility rates and low immigration, the

population of Russia is projected to fall to 68 million people by the

end of the century. This equals the population of France. ~ M.Firer, Quora

THE CIRCASSIAN GENOCIDE

~ In the early 19th century, the Circassian genocide took place. Russian generals killed or expelled virtually all Circassian people from the Caucasus, considering them subhumans unworthy of life. By the end, between 95 to 97 percent of the total Circassian population was killed or expelled forever from the Caucasus.

Circassians being expelled

As of 2023, no country in the world recognizes the Circassian Genocide, aside from Georgia. In Russia, it is denied to this very day. The percentage of Circassians eradicated by Russia is higher than that of Jewish or gypsy people during the Holocaust, and the genocide lasted longer too, from the early 1800s until around 1870. It was a complete and utter annihilation of a people. Women, raped systematically. Children, infants, butchered. One of the most thorough exterminations of an entire culture and group of people ever committed in history.

A particularly cruel general, Grigori Zass ,pictured above, was more or less Russia’s 19th century equivalent of Hitler. But unlike Hitler, Zass personally participated gleefully in massacres. Taking advantage of the superstitious beliefs of his enemy, he would spread rumors about him turning steel into gold, or being bulletproof… the Circassians believed it. He’d fake his own death, then re-emerge as a phantom from hell, descending down on little towns and butchering everything within sight…

All tribes were absolutely decimated, and some were destroyed so utterly that their numbers were reduced to zero. It’s hard to wrap the mind around: tribes of up to a hundred thousand souls, and not a single one of them left alive just a few years later.

Not only does Russia deny the genocide… some take pride in it. Russian nationalists in the Caucasus region continue to celebrate the day when the Circassian deportation was launched, 21 May (O.S), each year as a "Holy Conquest Day". What did the Circassians do to deserve all this cruelty? They were Muslims, and therefore subhuman.

~ Jean-Marie Valheur, Quora

Michael Burden:

Some of the Circassians ended up in the Levant, and I passed by a Circassian village in Galilee when I visited Israel more than forty years ago now.

Alexander Zheleznev:

Not all the missing people were massacred but a lot of them were expelled. Nowadays there are about 5m Circassians half of them live in Turkey and about 15% still live in Russia others spread mainly over MENA (Middle East and North Africa).

Robert Matthews:

Fortunately, the Circassians were not ALL wiped out. Some are still living in Israel and nearby: Jordan, Syria, and Turkey.

*

Dima Vorobiev:

In the poster below, Stalin, a Georgian, and a great variety of ethnicities. Yet, Stalin pointedly singles out the European-looking man in front of him who wears distinctly Westernized clothes.

Patric O’Leary:

This was also reflected by Stalin’s cronies in the Politburo: many were non-Russian: Beria — a Georgian, Ordzhonikidze — a Georgian, Mikoyan — an Armenian, Kaganovich — a Jew, Rudzutak — a Latvian, Kosior — a Pole…

*

RUSSIAN MILITARY RECRUITMENT CONTINUES

Russia is awash with recruitment posters enticing young men with huge cash bonuses to sign up as cannon fodder, 2nd class in Ukraine. Recruitment numbers are adequate, but only due to a combination of high bonuses, constant pressure to enlist and often a lack of better options to make your ends meet. It’s no secret recruitment in Moscow and St.Petersburg is rather low and most soldiers come from economically depressed regions across Russia.

It should be noted Russian culture and way of thinking is a bit different than what you’re used to. In Russia a bully is often the hero to be respected and the poor soul he mauls every so often is not to be pitied. The Kremlin acts as the ultimate bully everyone fears and secretly admires, but no one dares to stand up to.

Not all Russians function like that, but many do and those who don’t usually leave the country if and when they can. The exodus at the start of the mobilization did inflict serious damage to Russian economy and reduced their pool of recruitable manpower, but it also served to stabilize the regime. Those who stayed behind are less likely to try to change system and more likely to just go along with it, even though they don’t like it one bit.

This is also why Russians are exploring the possibility of persecuting those who fled to avoid the draft. It gives them incentive to stay out of Russia, as well as legal means to do so. If you face prosecution in your home country because you didn’t want to be forced into an illegal war you’re certainly eligible for asylum over political persecution and eventual citizenship of a western country. Russia loses talent sure, but it also gets rid of potential troublemakers and this allows the regime to survive for another generation.

In any event, Russians who were eager to die for Putin already did so for the most part. The ones fighting now are those more willing to be maimed and/or killed in war than to do anything at home.

*

DOES PUTIN CARE ABOUT THE RUSSIAN PEOPLE?

Putin’s “Direct line” this week was a spectacle that was in works for months — actually, years.

In 2022, Putin cancelled the “Direct line”, because of defeats suffered by the Russian troops in Ukraine.

The war became part of the daily life. Like the USSR was fighting in Afghanistan for nearly 9 years — but except for some conscripts who died there while “fulfilling their international obligation” (according to the Soviet propaganda), and their families who were affected by the loss of loved ones, the rest of the Soviet people simply lived their lives. Their lives were getting worse, but not hugely, not at once — gradually, slowly. Just like now.

Yes, there are substantially more Russians affected by the war in Ukraine than during the Soviet “international mission” in Afghanistan.

But not caring about hundreds of thousands of their own soldiers killed or maimed, that’s something that no one expected from Russians.

No one, except Putin and the Russian government.

Even the families of mobilized Russians who are campaigning for demobilization of their husbands and sons, are shocked by the lack of support from other citizens. And the complete disregard of their requests by Putin — the wives sent hundreds (if not thousands) questions for the presidential “Direct line” – some of their questions were even shown on the blue screens during the press-conference.

Putin spent 4 hours at the “Direct line”, pretending that he cares.

That was, apparently, a strategic decision by the presidential PR spinners — show some “sharp questions” on screens (all questions that were shown had been pre-selected), to demonstrate that the president isn’t afraid of critique. But of course, Putin didn’t answer these questions. They were displayed just for the show.

The Russian government, led by Putin, by now only cares about staying in power. It only cares about keeping the serfs subdued and Putin happy.

By now, it’s all about the picture of success, rather than the essence of what is really happening. Everything is for show.

Even the fabled “victory” in the war is about showing off — about proving to the West that Russia can’t be battled against. About proving that Russia is a mighty superpower. How it’s done, at what cost to the Russian people — that’s totally unimportant.

To show off is more important than the lives of hundreds of thousands of Russians — Putin is ready to lose a million of soldiers in the next 5 years, just to prove his point. He’s ready to make that sacrifice.

And for the Russian government, Putin’s demise will be their demise; they are too deeply involved. There is no way out for them. They have to support Putin till the end.

Their end — or the end of the Russian Federation. Whichever comes first. ~ Elena Gold, Quora

Elena Gold:

Putin was a thief and a sadist before he became the chief of FSB and then the president of Russia. He was raised to be a thief and sadist by a “thief in law” and criminal authority from St. Petersburg (spent 20 years behind bars), Leonid Usvyatsev, who was his judo trainer and mentor.

Awake Energy Warrior:

Maybe it's because I had a grandfather that was very interested in history and so heard a lot about the Winter War growing up, but I absolutely expected the Russian government to not care about thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, or even millions of Russian Federation citizens dying, especially if they’re from the provinces. Their basic tactic is to throw bodies into the firing line until something happens.

This lack of caring about their own citizens is one of the clearest differences between Europeans and Russians.

Chris Brisbane:

Dictators only care about power. Chinese and Russian citizens are slave labor.

In Australia or the USA the wage is 700% higher than China. The CCP is running a sweatshop paying workers nothing,

Qeutopia:

I'm skeptical that he is that far gone, else he would have used nukes by now. He still cares, a bit, even if only that he would lose his applauding audience.

This is no doubt fake, but one question I saw — in Russian, against the blue background — was: “So what do the doctors say? How long before you croak?”

Putin is no doubt solidly shielded from this kind of dissent.

*

WHY THE 2007-08 FINANCIAL CRISIS LED CHINA TO GO A DIFFERENT DIRECTION THAN THE U.S. WITH ITS ECONOMIC MODEL

This month, President Joe Biden and President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) met in San Francisco amid trade wars and even the prospect of a catastrophic hot war over Taiwan. Their meeting took place during a nervous period in the history of China. After decades of spectacular growth, the Chinese economic miracle has sputtered, with huge implications for its own population and the world.

And yet, even as the most dire aspects of the Chinese economy make headlines, it remains the case that China is the foundry of the green energy revolution, making more solar panels and wind turbines and electric vehicles than any other country. To help us understand how China thinks about economics, technology, and America, we welcome back to the show writer Dan Wang.

Derek Thompson: So I really wanted to have you on the show to talk about a few themes related to China: what’s gone so wrong with their economy and the purported Chinese Century, but also what’s gone right that the Western media might’ve missed.

So first, let’s talk about the economy. In 2007, you go back to the financial crisis, and you told the writer Ben Thompson, “After the financial crisis, China decided that it doesn’t have too much to learn from the West anymore.” Tell me about that. Why did China 15, 16 years ago decide it was time to chart a totally different course of economic growth than the West?

Dan Wang: I think the global financial crisis in 2007, 2008 was a pretty pivotal moment for the Communist Party in Beijing. I think it would be oversimplifying a bit, but to play up this model, … I think one could have told a story of happy convergence between China and the U.S. prior to 2007, 2008, when there were some green shoots of political liberalism in China. There was a little bit more of a spirit of cooperation between these two countries when George Bush was getting together with Hu Jintao.

And then after 2007, 2008, I think China, along with quite a few other countries in the world, took a look at the U.S. and said, “Well, maybe not.” This was a pretty devastating financial crisis built off of—the popular explanation at the time was excessive housing construction, excessive speculation, people getting loans for houses. And the Chinese, I think, took a look at this model and said, “Well, maybe we shouldn’t have so much of a financialized economy that is prone to these sorts of financial crises.”

So I think they started to take a little bit of a pivot onto the other side, really much more to double down on much greater political authoritarianism, much greater centralization of power, as well as what I think is a little bit more of a retro view of the economy. And if I want to fast-forward to today, the way I’ve described Xi Jinping’s view of a lot of economics would be actually a pretty boring, traditional manufacturing superpower along the lines of Germany today.

Or maybe you can talk about the United States back in the 1950s, in which you have a very large manufacturing sector employing a lot of workers in these kind of traditional, boring manufacturing/high-capital industries because they don’t create too many political problems, [in] that they are not prone to financial crises, that they are not agitating for a lot of social change on the internet, and that people are pretty happy earning a wage turning wrenches, to put it simply, for a lot of different manufacturing models.

And so I think the Chinese government really decided to double down: less financialization, a little bit less of the Silicon Valley disruptive model, and much more of this kind of boring, traditional manufacturing-led growth.

Thompson: So before the crisis, the story of happy convergence. After the global financial crisis, it’s the story of purposeful divergence. Give me some texture on what that looked like, what that felt like living in China. You no longer live in China; you now live in Connecticut. But what did the kind of political centralization that you’re describing feel like to residents of China?

Wang: Well, to residents of China—I wasn’t in China at the time in 2008—there were two, I think, major pieces of divergence that we can think about today. The first is there was a lot more political centralization in the five years after the financial crisis that led to the elevation of Xi Jinping as the general secretary of the Communist Party. So Xi Jinping came to power with a party that felt, and that self-acknowledged in a way, … pretty diffident, that it had a lot of these factions, that it had a security chief that was running his own fiefdoms, that there were a lot of other members of the Chinese elite that were simply not really listening to the leader.

And then Xi Jinping arrived with this mandate to really try to clean house, really try to make sure that there is much more centralization of power, which he did with not extreme effectiveness, to the extent that I think it is pretty likely that he will be the ruler of China for life, at least for the next five to 10 years.

The other manifestation of the economic divergence was—I think back in 2008, I’m sure you were covering, Derek, these debates about the stimulus, how much America should have been investing. I think there is a little bit of an economic consensus now that the administration under President Obama didn’t quite invest enough, that there should have been a much more vigorous fiscal response to the financial crisis.

And in China, they did not really have anything like this underinvestment response. They had this enormous infrastructure building spree. They built about 20 Japans’ worth of high-speed track in the aftermath of 2008. They built about 140 million housing units. I just saw this estimate from a bank about the population, let’s say half the population of America: They built that over the course of a decade. They built roads and highways. They built enormous bridges. And so there was an enormous infrastructure boom really to build up the country after the financial crisis. ~

https://www.theringer.com/2023/11/28/23979075/china-economy-technology-green-energy

*

MAESTRO: A MUST-SEE MOVIE WHATEVER ITS FLAWS MAY BE

Let’s start with an even-handed Ebert review:

~ With “Maestro,” Bradley Cooper tells the story of a generation-defining artistic innovator in the most traditional way possible: through the familiar tropes and linear narrative of a standard biopic.

Directing and starring as the legendary composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, Cooper has crafted a film that’s technically dazzling but emotionally frustrating. The script he co-wrote with Josh Singer (“Spotlight”) follows a well-trod, episodic path: This happened, then this happened, then this happened. Ultimately, it falls into the same trap as so many biopics, especially prestige pictures with major award aspirations: In covering a huge swath of an extremely famous person’s life, it ends up feeling superficial.

And yet, you should see it. Yes, this sounds contradictory, but “Maestro” is so consistently spectacular from an aesthetic perspective that it’s worth watching. The cinematography, costumes, and production design are all evocative and precise as they evolve with the times over 40 some-odd years of Bernstein’s life. Behind the camera, Cooper takes a big swing in making you feel as if you’re watching a movie that was made in the ’40s and continues to do so with each era.

Shooting in high-contrast black and white and Academy ratio, Matthew Libatique — an Oscar nominee as director of photography on Cooper’s debut feature, “A Star Is Born”— works wonders with a single light bulb on a barren stage, for example. There’s a shot where Carey Mulligan as Felicia Montealegre, who will become Bernstein’s wife, steps off a bus at night and walks up the street to the party where she’ll meet him for the first time, and it’s breathtaking in its cinematic authenticity. The lush Technicolor of scenes set in the ‘60s and ’70 offers its own vibrant allure. And inspired transitions from editor Michelle Tesoro carry the story across time and place in thrilling fashion.

Cooper has clearly taken great care in getting the details right, big and small. That includes spending six years learning how to conduct to perfect a particularly essential scene: a six-plus minute recreation of Bernstein leading the London Symphony Orchestra in Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony No. 2 at Ely Cathedral in 1973. (Yannick Nézet-Séguin was Cooper’s crucial conducting consultant.) The camera roams fluidly across the orchestra, choir, and soloists, the music overtaking his entire body and booming throughout this majestic edifice. Bernstein is passionate and rapturous with perspiration; this is the apex of his joy. The whole film is worth seeing in a theater before it begins streaming on Netflix on Dec. 20, but this lengthy, cathartic moment is one you’ll want to experience with the best possible picture and sound.

But while Bernstein’s music is woven throughout — including an amusing use of his “West Side Story” prologue during a period of marital discord — we never truly understand him deeply as a musician or a man. He’s a legend, a larger-than-life cultural force in mid-century America whose persona extends far beyond the rarefied circles of the classical music world. But the necessarily performative nature of Bernstein’s existence, as a closeted gay man, keeps us at a distance as viewers, too. Fully aware of his brilliance and increasing celebrity, he was always “on.” We spy a few glimmers of his intimate happiness with various men, including Matt Bomer as a clarinetist ex-boyfriend, with whom he shares a heartbreaking, tearful farewell on a Manhattan sidewalk. But a tantalizing, unfulfilled quality to the characterization lingers throughout.

Lenny’s relationship with Felicia was complicated, yet “Maestro” rarely digs far beyond the surface. The two share a bubbly, infectious chemistry as they meet and fall in love — and Cooper the director wisely lets these scenes, and later the couple’s arguments, play out in long, single takes. The affection between them feels genuine, and Mulligan is frequently magnificent, finding avenues in her portrayal of Felicia that elevate it beyond the mere woman-behind-the-man notion.

And yet, the Costa Rican-Chilean actress is often literally in Bernstein’s shadow; one image finds her standing in the wings as her husband conducts, with the exaggerated shape of him swallowing her up as if he were a monster. (Mulligan is also the beneficiary of costume designer Mark Bridges’ most exquisite fashions throughout the film.) But how does Felicia truly feel about sharing her husband with a series of men, most younger and fawning? She catches him kissing a party guest in the hallway of their apartment in the historic Dakota building and icily scolds him: “Fix your hair. You’re getting sloppy.” That comes close to the real, raw emotion that would have given “Maestro” more heft.

Speaking of the skin-deep nature of the movie, much has been made about Cooper’s decision to wear elaborate prosthetics to make his transformation into Bernstein more complete. The prominent nose, in particular, has been a source of consternation, as Cooper is not Jewish. (Bernstein’s children have defended the choice.) Makeup guru Kazu Hiro, who won Academy Awards for turning Gary Oldman into Winston Churchill for “The Darkest Hour” and Charlize Theron into Megyn Kelly for “Bombshell,” does thoroughly convincing work here, especially when Bernstein appears as a 70-year-old man at the very beginning and end of the film.

Something does happen toward the film’s conclusion, though, that deserves criticism. It’s the late 1980s, and the frame has expanded to widescreen. Bernstein drives his Jaguar convertible, blaring R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine).” Just as he zooms into the center of the shot, lead singer Michael Stipe yells the lyric “Leonard Bernstein!” Maybe this is something Bernstein did in real life; he clearly thought quite highly of himself, so maybe he was so tickled to be mentioned in this capacity. But in a movie, this choice was eye-rollingly on the nose. I groaned audibly.

Bernstein took chances with his work; that’s what made him great. “Maestro” would have been stronger if it had done the same.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/maestro-movie-review-2023

Misha Iossel:

I enjoyed the movie in spite of the female lead, Carey Mulligan as Felicia Monteallegre, Bernstein’s wife and mother of his three children. Not that hers was a bad performance; she convincingly depicts the strain of being the spouse of a famous person, and there is nothing objective I can fault her for. It was just a personal antipathy at first sight.

I resented her very presence in the movie. I wanted to stay with Lenny and him alone — and of course the music, his real great love. I wanted to watch this particular Lenny so much that she seemed an annoying intruder. I felt profound relief after she’s gone from the movie (she dies of a particularly painful form of metastatic lung cancer) and the screen fills with ecstatic greenery — gone at last, gone at last, thank god she’s gone at last!

Let me repeat that of course I understand that it’s very difficult to be a spouse of a famous person. Everyone wants him, not her — she's like a piece of furniture obtruding the way. On top of that, Leonard was bisexual and had affairs with men, e.g. his favorite clarinetist with the lush dark hair (I wanted to know more about that).

Of course the gay affairs must have added to Felicia's stress, for all her protesting about understanding him completely. Her lung cancer may have had something to do with her living in a state of concealed resentment (and the constant smoking that practically saturates this movie; alcohol and cocaine pale next to the incessant cigarettes).

In fact he left her once and settled with a male lover in California (no, not the clarinetist) — but returned to Felicia when he learned that she had terminal cancer. Hardly a “selfish monster” — artists are so frequently accused of being that. And sometimes they are — Picasso is a perfect example of a famous artist who was a rat with women.)

I also badly wanted to see at least a bit of Bernstein’s creative struggle when composing, his moments of despair, the tossing out of a day’s work— any creative person is familiar with that agony. Showing only the ecstasy and the triumphs is too one-sided.

And why is he always shown with other people? I wanted him on the screen alone, just for me.

My favorite part of the movie was the opening — young Lenny in bed with a male lover gets a phone call that Bruno Walter is sick, and Bernstein literally jumps out of bed and rushes to conduct in Bruno Walter’s stead — without having had the chance to rehearse. He’s an instant star and the audience’s darling — so handsome and energetic. Add to this that he was American-born (unlike other famous conductors of that era), soulful, charismatic, ageless.

Please disregard my idiosyncratic antipathy toward the wife, and do go to see Maestro — a wonderful movie, a mental detox for this time of year.

*

AN ISOLATED HUNTER-GATHERER COMMUNITY IN AFRICA PROVIDES INSIGHTS ON CHILD CARE

Mothers in the distant past may have had much more support than they do today, according to a study of an isolated community in the Republic of Congo that practices a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

Researchers found that infants in the group, known as the Mbendjele, receive attentive care and physical contact for about nine hours per day from around 14 different caregivers.

“We lived as hunter-gatherers for 95% of our evolutionary history. It was only 10,000 years ago that we stopped,” said study coauthor Nikhil Chaudhary, a researcher at the Leverhulme Centre of Human Evolutionary Studies at the University of Cambridge.

“Contemporary hunter-gatherer societies can offer clues as to whether there are certain child-rearing systems to which infants, and their mothers, may be psychologically adapted,” Chaudhary said.

Part of the region’s nomadic BaYaka population that live in the Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic, the Mbendjele are a highly mobile and egalitarian group that live in multifamily camps of 20 to 80 people. The study, which published this week in the journal Developmental Psychology, described them as “immediate-return” hunter-gatherers because they don’t store food for future use.

Responses to crying

They extrapolated their observations for a typical 12-hour stretch when parents might be going about their work. For example, if a child was held for four and a half hours of the nine hours of observation (accounting for researchers’ breaks), the child was assumed to be held for six out of 12 consecutive daylight hours.

The team noticed that caregivers responded to crying rapidly, via comforting, soothing, feeding, holding or affection, never scolding. The children had a high degree of physical contact and care for most of time they were observed.

The team recorded 220 bouts of crying, and caregivers responded to all but three cases — the vast majority within 25 seconds. Two situations where cries didn’t elicit a response were resolved without input from a caregiver in just a minute, but in one case, a child was left to cry for 13 minutes. Infants rarely spent time alone, and for more than nine hours of the observational period they were in close contact with a caregiver, and they were held for more than five hours.

Toddlers — between 1 ½ and 4 years — were alone for 35.7 minutes of the time studied and were in close physical contact with a caregiver for more than half the day.

What was notable, Chaudhary said, wasn’t necessarily the amount of care children received, but that mothers weren’t responsible for all of it. Other caregivers — fathers, older siblings and nonrelatives — were responsible for 38% to 46% of close care, according to the study.

While the mother responded alone to just under half of the crying bouts, more than 40% of crying episodes were resolved without any input from the mother. The mean number of caregivers other than a child’s mother was 14.4, but these weren’t all adults. Often it was an older sibling.

The study found that while young children benefited from a wide set of caregivers, they had a smaller number of key caregivers within this network, particularly when it came to responding to crying, which, the researchers said, still allowed strong attachments to form.

“The sheer number of people involved in looking after a kid. … It’s so different from the nuclear family system,” Chaudhary said.

“I think the starkest difference is how young the kids are when they start looking after babies. It is really not uncommon to see a 4- or 5-year-old soothing a (younger) child.”

WHAT WE CAN LEARN

Parenting experts not involved in the study said looking at different cultures offered an opportunity to reexamine assumed norms around parenting.

“Historically, parents (and especially mothers) in high-income Western countries have sometimes felt guilty for putting their children in childcare because they felt that they were somehow letting the child down by not being an exclusive caregiver,” said Jennifer Lansford, the S. Malcolm Gillis distinguished research professor of public policy and the director of the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University in North Carolina, via email.

“I think the perspective from this paper suggests that children are not necessarily primed to function best with just a single caregiver and that sensitive, responsive caregiving roles can be filled by a number of people in a child’s life,” Lansford said.

Carlo Schuengel, a professor specializing in child and family studies at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, found it notable that “even in a hunter-gatherer society in which young children are in the proximity of large numbers of adults, close care is predominantly provided by a low number of selected caregivers.”

“This is yet another set of observations that show how attachment — a form of selective proximity seeking in times of stress — develops across a wide range of cultures and societies,” Schuengel said.

“The research is fascinating and important because it lets us consider alternative solutions for the conflicting demands placed on parents in other societies such as our own.”

However, he emphasized that studies of other cultures “cannot replace careful testing and evaluation of efforts we might make to further improve child care.”

Marc Bornstein, editor of the academic journal Parenting: Science and Practice, agreed. He cautioned that it was important not to overreach in interpreting such a study, given that only 18 children — eight girls and 10 boys — were involved. “How representative would a day care center with 18 children in inner-city London be of childhood … anywhere?” he asked.

He noted that child mortality was high among hunter-gatherer groups and said that the study painted “a rather rosy picture of life among the hunter-gatherer Mbendjele.”

Not living fossils

The researchers acknowledged in the new paper that sample size is small, and a larger sample would strengthen the reliability of the findings — as would following children over longer periods.

They also noted that present-day hunter-gatherers are not “living fossils.” They are still very much modern populations, even if their ways of life might offer clues about ancient parenting techniques.

“We need to be very careful when making claims about human evolutionary history based on living hunter-gatherers. We certainly can’t take for granted that we’re adapted to that way of life,” Chaudhary said.

Nevertheless, Chaudhary said that studies of child-rearing among groups such as the Mbendjele suggest that for much of human history raising a child involved large numbers of people and that “mothers aren’t meant to manage alone.”

“The narrative around motherhood, ironically, often has

sort of evolutionary and biological tones to it … women have this maternal instinct and just know how to look after a baby,” he said.

“It could not be further from the truth in terms of how much of a cooperative venture child-rearing is (among the Mbendjele) and how much support mothers have.”

https://www.cnn.com/2023/11/17/health/parenting-childcare-hunter-gatherers-wellness-scn/index.html

*

THE ENDS OF KNOWLEDGE

~ Right now, many forms of knowledge production seem to be facing their end. The crisis of the humanities has reached a tipping point of financial and popular disinvestment, while technological advances such as new artificial intelligence programs may outstrip human ingenuity. As news outlets disappear, extreme political movements question the concept of objectivity and the scientific process. Many of our systems for producing and certifying knowledge have ended or are ending.

We want to offer a new perspective by arguing that it is salutary – or even desirable – for knowledge projects to confront their ends. With humanities scholars, social scientists and natural scientists all forced to defend their work, from accusations of the ‘hoax’ of climate change to assumptions of the ‘uselessness’ of a humanities degree, knowledge producers within and without academia are challenged to articulate why they do what they do and, we suggest, when they might be done. The prospect of an artificially or externally imposed end can help clarify both the purpose and endpoint of our scholarship.

Some may be quick to point out that past efforts at ending often appear quixotic or ludicrous with the advantage of hindsight. For literary scholars, the paradigmatic examples of this are Jorge Luis Borges’s short story ‘The Library of Babel’ (1941) and the character of Edward Casaubon in George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch (1871-2). Casaubon’s work on his Key to All Mythologies is literally unending; he dies before completing it, leading his young wife Dorothea to worry that he will guilt her into promising to continue the work after his death.

Scientists too have sometimes conceived of their ends as providing, as Philip Kitcher wrote in his essay ‘The Ends of the Sciences’ (2004), ‘a complete true account of the universe’, but the idea that such an account could exist, or that, if it did, we could comprehend it, remains very much in doubt. The aspiration for a global end is generally delusive and potentially dystopian.

Of course, knowledge production does not take place solely within the ivory tower. It was precisely during the Enlightenment that writers such as Joseph Addison called for philosophy to be brought ‘out of Closets and Libraries, Schools and Colleges, to dwell in Clubs and Assemblies, at Tea-tables, and in Coffee-houses’. The period saw the takeoff of ‘improvement’ societies, which initially focused on agricultural and public infrastructure but soon expanded to include the arts and sciences more broadly. Some of these organizations, such as Britain’s Royal Society (originally the Royal Society for Improving Natural Knowledge), remain important institutions for bridging the continuing gap between universities and the public.

But other extra-academic efforts have had the goal of repudiating the university, rather than connecting with it. The Thiel Fellowship, founded by the Right-wing venture capitalist Peter Thiel, provides recipients with a two-year $100,000 grant on the condition that they drop out of or skip university in order to ‘build new things instead of sitting in a classroom’. For many, academic organizations appear moribund and continuing improvement requires new institutional arrangements. Ending one institutional arrangement often happens in the name of starting something new.

As we noted, our survey found four ideas of the ends of knowledge: telos, terminus, termination and apocalypse. The 19th-century formation of the university established our three primary divisions of the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences. Now, we are proposing a thought experiment of a new four-part structure. What might a department or division of unification or conceptualization look like? We are asking how knowledge production might change to fit the present moment if we organize ourselves not by content – English, physics, computer science and so on – but by how we understand our ends.

Returning to the Enlightenment shows how concerns over disciplinary divisions have been present since their inception. In 1728, Ephraim Chambers, editor of the Cyclopædia, wondered ‘whether it might not be more for the general Interest of Learning, to have all the Inclosures and Partitions thrown down, and the whole laid in common again, under one undistinguish’d Name’.

By the end of the century, the redivision of knowledge had been formalized in the proto-disciplinary ‘Treatises and Systems’ of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. In 1818, the rise of specialist groups like the Linnean Society and the Geological Society of London led the eminent naturalist Joseph Banks to write: ‘I see plainly that all these new-fangled Associations will finally dismantle the Royal Society.’ Disciplinarity was seen as ending some kinds of knowledge while not fulfilling their ends.

The boundaries established in the mid-19th century and hardened throughout the 20th are now maintained managerially and financially as well as through methods and curricula; they are often reified by architecture and geography, with humanities and STEM departments housed in buildings on opposite ends of campuses.

For a long time, these tactics and strategies worked: they gave the new disciplines that emerged from the Enlightenment time and space to grow. Disciplinarity offers an important means to certify knowledge production.

The strategies that got us this far, however, may not be the ones we need to move forward. Can we escape the discourse of competition and crisis, which tends to keep us focused on the health of individual disciplines or college majors, by reorganizing knowledge production around questions or problems rather than objects of study? What if, instead of endlessly attempting to analyze and remedy the troubles of a particular division, we turn our attention to the system of division itself?

Our volume is an initial attempt to see what the advancement of learning could look like if it were to be reoriented around emergent ends rather than inherited structures. The question of ends must continue to be pursued at increasing scales, from the individual researcher, to the office or department, to the discipline, to the university, to academia and to knowledge production as a whole. The shared project of considering the end(s) of knowledge work reveals the rich history and scholarly investments of individual disciplines as well as the larger goal of producing accurate knowledge that is oriented toward a more ethical, informed, just and reflective world. We are, in many ways, only at the beginning of the end.

https://aeon.co/essays/should-academic-disciplines-have-both-a-purpose-and-a-finish-date?utm_source=Aeon+Newsletter&utm_campaign=45c8d99023-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2023_09_29&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-b43a9ed933-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D

*

This is certainly not the deity I was indoctrinated to worship. Mine was the god of punishment. Sin and punishment were the defining center of the old-time Catholicism.

*

*

Solaris (1976) Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, based on a novel by Stanislaw Lem

*

THE DAYDREAMING MICE: WHAT HAPPENS IN THEIR BRAINS

You are sitting quietly, and suddenly your brain tunes out the world and wanders to something else entirely — perhaps a recent experience, or an old memory. You just had a daydream.

Yet despite the ubiquity of this experience, what is happening in the brain while daydreaming is a question that has largely eluded neuroscientists.

Now, a study in mice, published Dec. 13 in Nature, has brought a team led by researchers at Harvard Medical School one step closer to figuring it out.

The researchers tracked the activity of neurons in the visual cortex of the brains of mice while the animals remained in a quiet waking state. They found that occasionally these neurons fired in a pattern similar to one that occurred when a mouse looked at an actual image, suggesting that the mouse was thinking — or daydreaming — about the image. Moreover, the patterns of activity during a mouse's first few daydreams o

f the day predicted how the brain's response to the image would change over time.

The research provides tantalizing, if preliminary, evidence that daydreams can shape the brain's future response to what it sees. This causal relationship needs to be confirmed in further research, the team cautioned, but the results offer an intriguing clue that daydreams during quiet waking may play a role in brain plasticity — the brain's ability to remodel itself in response to new experiences.

"We wanted to know how this daydreaming process occurred on a neurobiological level, and whether these moments of quiet reflection could be important for learning and memory," said lead author Nghia Nguyen, a PhD student in neurobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS.

An overlooked brain region

Scientists have spent considerable time studying how neurons replay past events to form memories and map the physical environment in the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped brain region that plays a key role in memory and spatial navigation.

By contrast, there has been little research on the replay of neurons in other brain regions, including the visual cortex. Such efforts would provide valuable insights about how visual memories are formed.

"My lab became interested in whether we could record from enough neurons in the visual cortex to understand what exactly the mouse is remembering — and then connect that information to brain plasticity," said senior author Mark Andermann, professor of medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and professor of neurobiology at HMS.

In the new study, the researchers repeatedly showed mice one of two images, each consisting of a different checkerboard pattern of gray and dappled black and white squares. Between images, the mice spent a minute looking at a gray screen. The team simultaneously recorded activity from around 7,000 neurons in the visual cortex.

The researchers found that when a mouse looked at an image, the neurons fired in a specific pattern, and the patterns were different enough to discern image one from image two. More important, when a mouse looked at the gray screen between images, the neurons sometimes fired in a similar, but not identical, pattern, as when the mouse looked at the image, a sign that it was daydreaming about the image. These daydreams occurred only when mice were relaxed, characterized by calm behavior and small pupils.

Unsurprisingly, mice daydreamed more about the most recent image — and they had more daydreams at the beginning of the day than at the end, when they had already seen each image dozens of times.

But what the researchers found next was completely unexpected.

Throughout the day, and across days, the activity patterns seen when the mice looked at the images changed — what neuroscientists call "representational drift." Yet this drift wasn't random. Over time, the patterns associated with the images became even more different from each other, until each involved an almost entirely separate set of neurons. Notably, the pattern seen during a mouse's first few daydreams about an image predicted what the pattern would become when the mouse looked at the image later.

"There's drift in how the brain responds to the same image over time, and these early daydreams can predict where the drift is going," Andermann said.

Finally, the researchers found that the visual cortex daydreams occurred at the same time as replay activity occurred in the hippocampus, suggesting that the two brain regions were communicating during these daydreams.

To sit, perchance to daydream

Based on the results of the study, the researchers suspect that these daydreams may be actively involved in brain plasticity.

"When you see two different images many times, it becomes important to discriminate between them. Our findings suggest that daydreaming may guide this process by steering the neural patterns associated with the two images away from each other," Nguyen said, while noting that this relationship needs to be confirmed.

Nguyen added that learning to differentiate between the images should help the mouse respond to each image with more specificity in the future.

These observations align with a growing body of evidence in rodents and humans that entering a state of quiet wakefulness after an experience can improve learning and memory.

Next, the researchers plan to use their imaging tools to visualize the connections between individual neurons in the visual cortex and to examine how these connections change when the brain "sees" an image.

"We were chasing this 99 percent of unexplored brain activity and discovered that there's so much richness in the visual cortex that nobody knew anything about," Andermann said.

Whether daydreams in people involve similar activity patterns in the visual cortex is an open question, and the answer will require additional experiments. However, there is preliminary evidence that an analogous process occurs in humans when they recall visual imagery.

Randy Buckner, the Sosland Family Professor of Psychology and of Neuroscience at Harvard University, has shown that brain activity in the visual cortex increases when people are asked to recall an image in detail. Other studies have recorded flurries of electrical activity in the visual cortex and the hippocampus [brain structure involved in memory] during such recall.

For the researchers, the results of their study and others suggest that it may be important to make space for moments of quiet waking that lead to daydreams. For a mouse, this may mean taking a pause from looking at a series of images and, for a human, this could mean taking a break from scrolling on a smartphone.

"We feel pretty confident that if you never give yourself any awake downtime, you're not going to have as many of these daydream events, which may be important for brain plasticity," Andermann said. ~

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/12/231213112457.htm

*

HOW THE IMMUNE SYSTEM FIGHTS TO KEEP THE HERPES VIRUS AT BAY

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is extremely common, affecting nearly two-thirds of the world’s population, according to the World Health Organization.

Once inside the body, HSV establishes a latent infection that periodically awakens, causing painful blisters on the skin, typically around the nose and mouth. While a mere nuisance for most people, HSV can also lead to dangerous eye infections and brain inflammation in some people and cause life-threatening infections in newborns.

Researchers have long known that the virus and the host immune system are in a perpetual competition, but why does this battle reach a stasis in most people while causing serious infections in others?

More important, precisely how does the battle unfold at the level of cells and molecules? This question has continued to bedevil scientists and hamper the quest for treatments that prevent or cure infections.

A recent study by researchers at Harvard Medical School, conducted using lab-engineered cells and published in PNAS, unveils the precise maneuvers used by host and pathogen in the fight for dominance of the cell.

Furthermore, the research shows how the immune system keeps the virus at bay in a battle taking place at the control center of the cell — its nucleus.

Immune signaling proteins issue a call to arms

The research reveals a key role for a group of signaling proteins called interferons, which recruit other protective molecules and block the virus from establishing infection.

Once inside the host, HSV multiplies by making copies of itself inside the nuclei of cells, using the host’s genetic machinery. For that to happen, the virus must outcompete the host’s immune system. But many of the tactics the virus and the immune system use in this contest have remained a mystery, making it challenging to design medicines to help patients defeat the virus.

Interferons — named for their ability to interfere with pathogens’ attempts to infect cells — are signaling molecules released when the immune system detects the presence of microbes, such as viruses. The distress signals sent by interferons activate genes in that cell and other cells that produce proteins, which in turn block viruses from establishing infection in the first place.

Several different mechanisms that interferons use to thwart viruses within the cytoplasm, the gelatinous liquid that fills cells, are well known. But how interferons work against DNA viruses — those launching their attack within the cell nucleus — has remained elusive.

“We know a lot about how interferon and immune stimulants work against viruses in the cytoplasmic body of the cell, but up until now, we knew very little about how the immune system blocks viral infection in the cell’s nucleus,” said study senior author David Knipe, the Higgins Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS. “Our findings define the mechanisms of action of any treatment that induces interferons and how they can prevent and treat infections from HSV, as well as other herpesviruses and nuclear DNA viruses.”

Knipe said the insights from this work could also help researchers understand — and perhaps eventually develop treatments for — other nuclear DNA viruses, including well-known troublemakers like the Epstein-Barr virus, which causes mononucleosis; human papillomavirus; hepatitis B; and smallpox.

These results define the mechanisms of action of interferon treatments for herpesvirus diseases and other treatments such as toll-like receptor ligands that have been tested for herpes, the researchers said. Other new activators of interferons such as cGAS agonists could also be used to induce herpes resistance through the newly defined mechanisms, the researchers added.

The researchers caution that any new potential therapies for HSV and other DNA viruses are purely conceptual at this point. Any such approaches should be first tested in small animals such as mice, then in larger animals and, finally, in humans.

Mapping the steps of a viral arms race

In the new study, Knipe and co-author Catherine Sodroski, an HMS PhD graduate now at the National Institutes of Health, discovered that a host protein called IFI16 is recruited by interferon to help block the virus from reproducing in several ways.

One of the strategies used by IFI16 to fend off HSV involves building and maintaining a shell of molecules around the viral DNA genome. This molecular “bubble wrap” prevents the virus from unfurling. With the virus wrapped up, it can’t activate its DNA to express its genes and make copies of itself.

To counter these protective maneuvers, however, the virus produces molecules called VP16 and ICP0 that can remove the wrapping, deactivate the host cell’s protective molecules, and enable the virus to reproduce.

Another mechanism used by IFI16 to fight HSV infection is to neutralize VP16 and ICP016. Under normal circumstances, when the cell is not preparing to repel a viral invader, there is some IFI16 present within the nucleus. But this background level of IFI16 isn’t enough to fight off the viral helper proteins and keep the virus wrapped and restrained.

Without interferon’s call to the cell to send in more IFI16, the virus wins the arms race and infects the cell. However, the experiments showed, when interferon signals recruit higher levels of IFI16, the immune system wins.

This current study echoes similar findings that found elevated levels of IFI16 in clinical samples of tissues where the immune system appeared to be successfully controlling symptoms of the closely related HSV-2 virus, providing crucial insights about the molecular machinery at work in staving off outbreaks of symptoms.

Using insights from the lab to improve human health