Cemetery in Rakowice, near Krakow; photo: Anna Stępień

Cemetery in Rakowice, near Krakow; photo: Anna Stępień

*

ALL SOULS

Sometimes I think Warsaw fog

is the dead, coming back

to seek their old homes —

wanting to touch even the walls.

But they cannot find those walls,

so they embrace the trees instead,

lindens and enduring chestnuts;

they embrace the whole city,

lay their arms around the bridges

and the droplet-beaded street lamps;

they pray in the Square of Three Crosses,

kneel among the candles and flowers

under bronze plaques that say

On this spot, 100 people were shot —

they bow, they kiss

even the railroad tracks —

they do not complain, only hold

what they can, in unraveling white.

~ Oriana

Polish cemetery on All Souls'

Polish cemetery on All Souls'

*

“To love. To be loved. To never forget your own insignificance. To never get used to the unspeakable violence and the vulgar disparity of life around you. To seek joy in the saddest places. To pursue beauty to its lair. To never simplify what is complicated or complicate what is simple. To respect strength, never power. Above all, to watch. To try and understand. To never look away. And never, never to forget.” ~ Arundhati Roy, The Cost of Living

*

”When I was young, I was attracted to sorrow. It seemed interesting. It seemed an energy that would take me somewhere. Now I am older, if not old, and I hate sorrow. I see that it has no energy of its own, but uses mine, furtively. I see that it is leaden, without breath, and repetitious, and unsolvable.

And now I see that I am sorrowful about only a few things, but over and over.”

~ Mary Oliver

*

THE DECLINE AND FALL

~ Gibbon is widely regarded as a typical man of the Enlightenment, dedicated to asserting the claims of reason over superstition, to understanding history as a rational process, and to replacing divine revelation with sociological explanations for the rise of religion. He is probably cited most often for his facetious observations about early Christianity. He is particularly severe on the miracles ascribed to the early monastics.

“The favorites of heaven were accustomed to cure inveterate diseases with a touch, a word, or a distant message; and to expel the most obstinate daemons from the souls, or bodies, which they possessed. They familiarly accosted, or imperiously commanded, the lions or serpents of the desert; infused vegetation into a sapless trunk; suspended iron on the surface of the water; passed the Nile on the back of a crocodile, and refreshed themselves in a fiery furnace. These extravagant tales, which display the fiction, without the genius, of poetry, have seriously affected the reason and the morals of the Christians. Their credulity debased and vitiated the faculties of the mind: they corrupted the evidence of history; and superstition gradually extinguished the hostile light of philosophy and science.”

He tells the story of a Benedictine abbot who confessed: “‘My vow of poverty has given me an hundred thousand crowns a year; my vow of obedience has raised me to the rank of a sovereign prince.’—I forget the consequences of his vow of chastity.” He recounts how the practices of penance and the renunciation of the world produced one sect of Anchoret monks who “derived their name from their humble practice of grazing in the fields of Mesopotamia with the common herd.”

More grimly, he reports the murderous zeal with which Christians pursued those of the faith defined as heretics. He produces a document from an inquisition into the heresy of Eutyches in 448 A.D.: “‘May those who divide Christ be divided with the sword, may they be hewn in pieces, may they be burnt alive!’ were the charitable wishes of a Christian synod.”

In contrast to such passion, Gibbon prefers the philosophical temperament of ancient Athens, and he reserves his severest rebukes for two of the men who broke “the golden chain of Platonic succession.” The Archbishop of Alexandria, Theophilus, “a bold, bad man, whose hands were alternately polluted with gold, and with blood,” in 389 A.D. sacked the edifices of the old Roman pagan religion, destroying the library of Alexandria and the two hundred thousand volumes of Greek and Roman literature deposited there by Marc Antony. “The compositions of ancient genius, so many of which have irretrievably perished, might surely have been excepted from the wreck of idolatry, for the amusement and instruction of succeeding ages; and either the zeal or the avarice of the archbishop might have been satiated with the rich spoils, which were the reward of his victory.”

The Emperor Justinian in 529 A.D. suppressed the remaining Greek schools of philosophy in the name of Christ. “The Gothic arms were less fatal to the schools of Athens than the establishment of a new religion, whose ministers superseded the exercise of reason, resolved every question by an article of faith, and condemned the infidel or skeptic to eternal flames.” In the summary of the fall of Rome that he gives midway through his opus, Gibbon includes “the abuse of Christianity” as one of the causes.

“The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity [timidity]; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of military spirit were buried in the cloister: a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers' pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes, who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity… . the church, and even the state, were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody, and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from the camps to the synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny; and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country.”

Gibbon’s modern reputation, accordingly, is largely that of an English Voltaire or Montesquieu, a man warning his country, at a time of its own rising imperial fortunes, of the need to throw off the shackles of superstition and the institutions that produced it. There are aspects of Gibbon’s own career that support this impression. After he left Oxford, his real education took place at Lausanne in French Switzerland, and his first attempts at literary essays were written in French. His own great work, though inspired by his celebrated vision of barefoot monks chanting vespers in the Temple of Jupiter in the Capitol, actually began as an English attempt to better Montesquieu’s earlier history of Rome, Considerations on the Causes of the Grandeur of Rome and its Decline.

Certainly, it was as an Enlightenment radical that Gibbon appeared to my generation who, as undergraduates in the 1960s, read him in the only version of his work then readily and cheaply available, the nine hundred page abridged edition published by Penguin under its old Pelican label. But now, reading the whole thing in this new Penguin Classics edition, a very different Gibbon emerges, one that suggests an alternative view of the Enlightenment in England as well.

Apart from publishing the full text, the major difference between the Penguin Classics and the old Pelican edition is that the former contains all Gibbon’s footnotes, which are so extensive they consume roughly 20 percent of the total printed space. In a few places, they take up no less than three-quarters of the whole page. Gibbon uses his footnotes not only to source his references but also to make lengthy, sometimes acrimonious, sometimes witty, commentaries on the veracity of both his primary and secondary sources. (A sample: “The Dissertation of M. Biet seems to have been justly preferred to the discourse of his more celebrated competitor, the Abbé le Boeuf, an antiquarian, whose name was happily expressive of his talents.”)

Those with the fortitude to read them will find that a considerable number of Gibbon’s notes are devoted to disputing the French version of events, especially those of Baron Montesquieu and several other Enlightenment philosophes. Gibbon corrects Montesquieu in both his detail and his theory of history. He points out that Montesquieu is ignorant of the extent of the penetration Gothic barbarians had made of both Rome’s territory and its mercenary forces—“the principal and immediate cause of the fall of the Western Empire.” And as the Introduction by Penguin’s editor, David Womersley, argues, and the text itself confirms in many places, Gibbon has a completely different interpretation of the nature of history.

Montesquieu was committed to establishing that the surface milieu of history bore an underlying rationale and that there were general causes for the rise and fall of civilizations that transcended the influence of individuals. The Decline and Fall, however, is a demonstration that history is often driven by politics and sometimes by chance and that human passion usually presides over human reason. In their interpretations of the course of empire, the English and French Enlightenments are worlds apart.

Gibbon is well known for the aphorism that “history is indeed little more than the register of the crimes, follies and misfortunes of mankind,” but this expression is rarely taken seriously because his own work appears to contradict it. The Decline and Fall contains some of the earliest versions of what later became the specializations of social history (in his analysis of the character of the barbarians of Germany and Siberia), economic history (the trade between Rome and China), and religious history (the sociology of paganism and Christianity; the institutional and theological development of the church). However, in the realm of Gibbon’s political history, it remains true that “crimes, follies and misfortunes” dominate the scene for long periods of time.

One of the reasons that Gibbon remains such a good read today is the pace of his story as he narrates the careers of those who ascended to the emperor’s purple robe from what were sometimes very humble origins as common soldiers, peasants, and slaves, or even, as in the case of Justinian’s wife, the Empress Theodora, from the nude cabaret and brothels of Constantinople.

But equality of opportunity was matched by equality of outcome. Rome was plagued for most of its existence by the problem of succession, which was normally accomplished by a civil or military rebellion combined with the assassination of the incumbent. “Such was the unhappy condition of the Roman emperors, that whatever might be their conduct, their fate was commonly the same. A life of pleasure or virtue, of severity or mildness, of indolence or glory, alike led to an untimely grave; and almost every reign is closed by the same disgusting repetition of treason and murder.”

The subjects of these princes sometimes remained immune to the violence of succession but at other times were bound up with it. In just three battles in the civil war of 323 A.D. between Constantine and Licinius, sixty thousand Romans were left dead in the field. When emperors fell, Gibbon notes, they could take whole provinces with them. After the failed revolt in about 265 A.D. of Ingenuus, whose troops in the province of Illyricum [modern Albania and Montenegro] had elevated him to usurp the purple, his rival Gallienus sent a message to one of his ministers.

“It is not enough,” says that soft but inhuman prince, "that you exterminate such as have appeared in arms: the chance of battle might have served me as effectually. The male sex of every age must be extirpated; provided that, in the execution of the children and the old men, you can contrive means to save our reputation. Let every one die who has dropt an expression, who has entertained a thought against me, against me, the son of Valerian, the father and brother of so many princes. Remember that Ingenuus was made emperor: tear, kill, hew in pieces. I write to you with my own hand, and would inspire you with my own feelings."

Gibbon’s analysis is sophisticated enough to recognize that a large-scale political system such as the Roman Empire can itself display relative stability while at the same time suffering continuous turbulence at the level of the palace. In the history of great monarchies, he says, the attention of both the writer and reader of history is naturally drawn to the court, the capital, and the army, while the millions of obedient subjects pursue their lives in obscurity. In less established systems, such as the early republics of Athens or Sparta, the impact of ordinary individuals is much greater and thus attracts more historical attention, even when this is sometimes unwarranted.

In other words, in opposition to the French search for general laws of historical causation, Gibbon argues that explanations need to be appropriate to their subject. In some historical circumstances, such as newly formed or emerging polities, the role of individuals such as founding fathers may be profound; in other circumstances, a system may be so well entrenched that it might survive the worst kind of abuse from apparently powerful political figures.

Similarly, once major internal systemic problems have emerged, neither the fortunes nor adversities of politics may be able to stem the tide. Under Justinian, the general Belisarius recaptured Italy from the Goths and Africa from the Vandals. But the economic decline of Rome, coupled with high taxes and the complete loss of martial spirit among the citizens, meant that new armies could not be raised and so the territorial gains could not be held.

Gibbon deploys a counterfactual (a device that some recent authors imagine has only just been invented) to argue that, under the reign of Justinian’s Byzantine court, Rome had reached the state of economic and political weakness where, even if “all the Barbarian conquerors had been annihilated in the same hour, their total destruction would not have restored the empire of the West.”

Gibbon also argues for the impact upon history of the role of chance, of the perfidy of distant decisions, and of the influence of unintended consequences. The outcomes of the wars between the various German tribes who contested the territories on the periphery of the empire, Gibbon demonstrates, depended as much on luck and ignorance of the enemy’s position as it did on strength of arms and valor. The eventual survival of the Franks in Gaul was due to such accidents and fortune, while the complete extermination of the Gepidae nation was the result of an alliance formed between the Lombard and the Avar kings that was directed more at Rome than at the hapless victim.

Volume Three of the Penguin edition traces the empire from 640 to 1500 when its history is dominated by the emergence of Islam, first by the Arab conquest of the Middle East and Africa, second by the Crusades which were organized in response, and third by the final capture of Constantinople by the Ottomans. The growth of Islam, Gibbon contends, was a matter of chance.

Deploying another counterfactual, he argues that had Justinian’s Abyssinian allies not lost an obscure military conflict in Yemen in the sixth century, Arabia would have been preserved for Christianity and the Islamic uprising that began in Mecca would never have happened.

“Mahomet must have been crushed in his cradle, and Abyssinia would have prevented a revolution which has changed the civil and religious state of the world.”

*

All of Gibbon’s mockery of the miracles claimed for hermit monks, of the celibacy of the clergy, of the worship of images and relics, and of the temporal lust for wealth and power displayed by so many princes of the church, can be explained by his Protestantism. Writing for an English audience, he is making the same kinds of criticism of Roman Catholicism that Protestants had urged since Luther.

To a Protestant audience, all his ridicule is directed at safe targets—the indulgence, myths, and deviations of Popery—and does not call into question the basis of the religion itself. At one point, he even comments that an epistle he cites will be “painful to the Catholic divines; while it is dear and familiar to our Protestant polemics.”

Moreover, his identification of Christianity as one of the causes of the fall of Rome is far from unequivocal. He certainly ascribes some responsibility to the otherworldliness adopted by “the useless multitudes of both sexes” who locked themselves away from society, but in the same passage he goes on to record how Christianity was a “principle of union as well as of dissension” and that the sermons from the pulpits of the empire “inculcated the duty of passive obedience to a lawful and orthodox sovereign.”

Gibbon’s own justification for recording so many of the flaws of the faith is that he is not writing theology, which is “the pleasing task of describing Religion as she descended from Heaven, arrayed in her native purity,” but history, which discovers “the inevitable mixture of error and corruption, which she contracted in a long residence upon earth, among a weak and degenerate race of beings.”

The Christianity for which he acknowledges most sympathy is the simple faith of the gospels, the creed that prevailed before theologians and bishops emerged to generate heresies, inquisitions, schisms, and innumerable sentences of death over fine lines of doctrine which few of the priesthood, let alone their parishioners, fully understood.

He quotes with approval the sentiments of Procopius, the chronicler of the political, military, and religious accomplishments of the age of Justinian: that religious controversy is the offspring of arrogance and folly; that true piety is most laudably expressed by silence and submission; that man, ignorant of his own nature, should not presume to scrutinize the nature of God; and that it is sufficient for us to know, that power and benevolence are the perfect attributes of the Deity.

Though it initially attracted some critics, Gibbon’s work was generally highly praised when it was published. It turned him into a London literary celebrity, and he was one of the most popular authors of his day. In 1776, he said his first volume was “on every table and on almost every toilet.” This means his writing was both an expression and a reflection of enlightened opinion in late eighteenth-century England.

If this is so, then this opinion cannot be equated with that of France at the same time. Besides those already discussed, there are other areas in The Decline and Fall that, if examined in detail, could make the same point. For instance, while the philosophes saw their king as the barrier to freedom, Gibbon argued that a hereditary monarchy was a precondition for a civilized political system since it solved the problem of arbitrary succession that had caused so much and such predictable bloodshed in Rome.

His attitude to the savages and barbarians of Siberia and Africa was also the opposite of his French contemporaries’. In a long passage, he dissects and demolishes Montesquieu’s concept of the “noble savage,” the idea that the natural man is virtuous and that it is civilization that makes him corrupt. For Gibbon, this Romantic idea is the opposite of the truth, as he demonstrates through several extensive examinations of the bleak and lawless pastoral societies of the Goths, Vandals, Huns, Tartars, Mongols, and other nomads of the plains of Siberia and Ukraine who periodically fought their way across the Danube to wreak havoc on the cultivated lands of the Mediterranean.

In short, the intellectual product and legacy of the English Enlightenment is quite different from that of the French. In Gibbon, the spirit of inquiry and the fruits of research confirm the value of the existing institutions of English society, including its religion. In France, these tools were deployed in opposition to the same institutions. In England, Gibbon emphasized the responsibility of individuals and celebrated the virtue and courage of statesmen and churchmen, where they existed, even though he recorded that the natural passions of humanity were likely to leave such qualities in short supply.

In France, the philosophes sought to find general laws of society that would render the actions of individuals irrelevant. The intellectual heritage of the English Enlightenment, as exemplified in Gibbon, clearly goes some of the way to explaining the different political histories of the two countries in the ensuing two centuries. England has enjoyed a stable and peaceful national history marked by a gradual extension of its democracy; France has been periodically racked by revolution, internal collapse, and foreign invasion.

Toward the end of his Introduction, David Womersley advises: “You are on the threshold of one of the greatest narratives of European literature.” Who could disagree? In its own way, The Decline and Fall is as powerful a work of art as King Lear, Hamlet, or Handel’s Messiah. Unlike these three, unfortunately, you cannot pop out one evening to the theater to take it in. It needs a whole summer holiday or a long winter by the fire, a time scale few of us today are likely to commit more than once or twice in a lifetime. Still, like any great work of art, once you have experienced it, you wonder how you could have lived without it. ~

https://newcriterion.com/issues/1997/6/edward-gibbon-the-enlightenment

*

IS A WORLD WITHOUT WORK DESIRABLE?

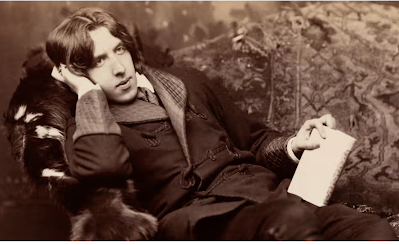

Oscar Wilde thought hard work “the refuge” of those with nothing better to do while he envisaged a society of “cultivated leisure” as machines performed the necessary and unpleasant tasks.

Karl Marx’s dream was of state-regulated general production that allowed liberated workers to “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner” without the drudgery of being tied to one job.

The 19th-century socialist activist William Morris advocated for more pleasurable work, believing that once the profit motive of the factory had been abolished, less necessary labor would lead to a four-hour day.

So Elon Musk’s suggestion to Rishi Sunak that society could reach a point where “no job is needed” and “you can do a job if you want a job … but the AI will do everything” revives a debate on the issue of how we work that has long been discussed.

Yet a world without work, experts question, may be more dystopian than utopian.

“This is an old, old story that never actually happens,” said Tom Hodgkinson, co-founder of the Idler magazine, which for three decades has been a platform to examine issues surrounding work and leisure.

“There was a poem in ancient Greece saying, ‘Isn’t it wonderful that we have invented the watermill so that we no longer have to grind our corn? The women can sit around doing nothing all day from now on.’ It’s that kind of recurrent idea.

“People like Bertrand Russell were talking about this in the 30s. What would we do without work? One view is people wouldn’t know what to do because people are more or less slavish. That they would just sit around watching daytime TV or porn all day.”

In fact, given more free time, such as on furlough during Covid, “they start living better”, Hodgkinson said. “They are starting neighborhood groups, doing more gardening, doing up the house, spending more time with family, doing creative things, playing music, writing poetry, all the things that are part of what I would call a good life.”

Despite that, he said, studies had shown that paid work was beneficial for mental health, for status and identity.

“I think we need to do some sort of work. We should be moving towards a shorter working week, and more leisure-filled society,” Hodgkinson said, adding that a radical overhaul of our economic and education models would be needed to eliminate work on the scale that Musk predicted.

One significant body of research in 2019, led by Brendan Burchell, professor in social sciences and a former president of Magdalene College, Cambridge, established that eight hours of paid employment a week was optimal in terms of benefit in mental health, and that no extra benefit was subsequently accrued.

Setting aside the “awful jobs that really screw you up”, Burchell said, “your average job is good for you” in terms of social interaction, working collectively, giving structure and sense of identity.

A world without work “is a terrible idea of what society would look like for all sorts of reasons, as well as people’s mental health,” he said.

The labor market, as a way of distributing money around the economy, would have to be transformed, as would the education system, “to teach people how to fill their days, by writing poetry or going fishing or whatever, instead of going to the factory or the office”, Burchell continued.

Shifting to shorter working hours was shown to have “massive benefits for people”, said Burchell, but he added: “If we move to a society where lots of people are completely excluded from the labor market, then I get very worried that’s going to be a very dystopian future.”

In his book Making Light Work: An End to Toil in the 21st Century, David Spencer, professor of economics at the University of Leeds, also makes the case for less work, but not its elimination. “It would leave us bereft potentially of things that we value in work,” he said, citing communal enterprise, personal relationships and the development of skillsets.

So in essence, we would be a poorer, sadder, less skilled society. “Yes, there will be some loss through loss of work,” Spencer said. “I realize not all work is good. So we ought to automate drudgery, seek to use AI to reduce the pain of work, and therefore leave work which is good.”

He draws from Morris, who talked about bringing joy to work. “Skillful work is good work and it has a role in the creation of a better society,” said Spencer. “We ought to use technology to create less and better work. In that sense, the future can be really positive.

This was, he added, the future imagined by “Oscar Wilde, William Morris, and a lot of utopian positive thinking, where technology makes work lighter. It’s not eliminating work – it’s bringing light to work.” ~

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/nov/03/experts-question-elon-musk-vision-of-ai-world-without-work

Mary:

A work- free world would be missing too much to be truly satisfying. I know when I was suddenly jobless there was a period of adjustment where I had to figure out what to do with my time, how to fill the days in ways that were interesting, challenging, and productive. Luckily I had many interests and "hobbies," that I now had real time to pursue.

For some, especially those who dedicated almost all their time and energies to their work, retirement can arrive and stir a real sense of panic — a kind of restless emptiness, filled with boredom and a growing unhappiness. People solve this in different ways...some find some sort of work, maybe part time, doing something they enjoy or feel passionate about. Some take up new interests, become artists in one way or another, finding new joy in creating. Some pursue their passions, ones they didn't have time for while working.

For those who don't find solutions in these ways there can be a long decline into passivity and boredom, which I am convinced, makes them more vulnerable to the illnesses and catastrophes of age, more likely to die sooner than those more active and engaged in the world.

Oriana:

I’ve witnessed it myself: when a man’s life is dedicated to his job [usually it’s a man who’s so job-centered], retirement can be a catastrophe. Work provides not only income, but also a purpose in life and social ties at the office. The reaction to the loss of a job through retirement can indeed lead to deep grief, with predictable negative impact on health.

The spouse. used to having the house all to herself during the day, may also be bothered by the husband unwanted presence during what used to be his “working hours.” It’s a huge disruption of the previous routine for both of them. While much is said about “retirement savings,” it seems that finding either volunteer work and/or special hobbies is much more essential.

Some college professors continue to teach part-time until their early eighties. This may seem like a great solution, but it deprives younger faculty of classes they are eager to teach. The same goes for editors and others in senior positions, the long-term alpha males who view retirement with dread. “Retirement? don’t ever mention that word to me!” I remember one grandfatherly editor exclaiming — exploding almost.

Some men take to obsessive fence painting and grass mowing, so that bare ground shows through — yes, I’ve witnessed that too. Others constantly go on cruises or join senior travel groups to places like Las Vegas or Disney World. The despair on the faces of some of these travelers is frightening.

One of the privileges of being self-employed is that you can carry on as long as health allows. If you are truly engaged and connected, you’ll also be healthier and live longer.

On the other hand, people who successfully transition to retirement may find that these are the happiest years of their lives.

Obviously, whether retirement is a virtual death sentence or the happiest period of one’s life depends on the individual — on the richness of life he’s managed to build up.

*

THE RISE IN LATER-YEARS DIVORCE

~ The instance of mature couples divorcing is on the rise. Are over 50s less inclined to stay together than their parents, and what makes a ‘good uncoupling’? ~

“I went through this process of feeling like my future had been stolen from me,” says 53-year-old Kate Christie about the end of her 22-year marriage. “He said to me, ‘I don’t love you any more. I want to leave our marriage. I want the chance to meet and fall in love with someone else while I’m still young.’ And that was that.”

“I felt really blindsided. I was angry, upset and resentful.”

Christie is one of a growing number of over 50s navigating life after separation and divorce.

“[There’s] definitely an uptick in mature age divorces compared to even 10 years ago,” says clinical psychologist, Dr Rashika Gomez. It’s an observation supported by the most recent research from the Australian Institute of Family Studies, which shows that the proportion of divorces among couples married for 20 years and longer has increased from about 20% in the 1980s and 1990s, to over 25% in 2021.

Dr Gomez has also noticed an increase in the number of those in mature marriages seeking relationship advice. “They’re seeking that outside opinion on [whether] something is wrong, because you can’t see it when you’re in it.”

It was a counselor that helped Brodie see her roller-coaster marriage for what it was – emotional abuse. “She was my savior,” says the 63-year-old of her counselor. But family and friends were shocked Brodie was calling it quits after 32 years. “We were known as the golden couple.” She shakes her head. “It was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do.”

Brodie says life on the other side has never been better. “Bloody amazing. I can feel the sunshine. I can hear the birds. I’ve rediscovered myself.” And despite her experience, she is not anti-relationships or anti-marriage. “But I can assure you I will never have anyone live with me again.

“I’d rather be on my own than unhappy,” she insists. “I’ve got my friends. I’ve got my sons.”

*

Recently divorced, Raymond is grateful he has the support of a boatload of good friends, but the 71-year-old longs for that special someone. “A lot of people think friends are enough. But I don’t think they are. You’ve got to have someone special that turns into a partner.”

And after 24 years of marriage, he thought he had that person, but the fear and uncertainty circulating during the pandemic tipped the relationship upside down. The final straw came after restrictions eased. His ex-wife was averse to him returning to the job he’s loved for over 43 years. “If you go, don’t come home.” So, ultimately, he moved out.

REACHING THE THRESHOLD

Dr Gomez describes the point Raymond reached as a “threshold,” a common reason those in mature marriages suddenly go “I can’t do this any more”.

Relationship therapist Clinton Power agrees reaching a threshold is when couples may see separation and divorce as inevitable. “Sometimes if there’s been a lot of hurt or betrayal or there’s an enormous distance from growing apart, the idea of working on the relationship feels more overwhelming than separating and starting anew.”

In his experience, the lack of a shared focus or a realization that the couple has fewer common interests are key contributors to mature age separation. It often occurs at the time the couple’s children reach early adulthood or leave home.

Another is midlife, when individuals in a relationship may undergo significant personal change or question the direction of their lives. “So that’s when I see some individuals in a relationship start to think, ‘hang on, I’m not completely happy here, this relationship is not fulfilling my needs’,” says Power.

“If you just look at life expectancy, for example, in the past, people didn’t live as long as we’re living now. Now we’re hitting 90, 100, with relatively fewer issues. So when you’re hitting your 50s, you’re no longer looking at 15 years more with someone you might find annoying, or you don’t get along with, you’re now looking at another 50 years with someone like that,” says Dr Gomez. “And that can feel really confronting, and overwhelming, and you just might not want to do that any more.”

Lawyer Brad Saunders, who has specialized in family law for 25 years, says the over 50s are less inclined to stay together and ‘grin and bear it’ than their parents. “More choose to separate and it is more acceptable to separate,” he says.

But he sees one major difference in the way older couples, in general, approach separation compared to younger couples. “Older couples are better at planning their separation more amicably.”

Power says he’s found many mature aged couples aim for a “good uncoupling” so that they can maintain a healthy relationship. “So maybe ‘we can be in each other’s lives and have a healthy relationship’, whereas sometimes that slash and burn approach happens in the younger couples.”

With his divorce finalized earlier this year, Raymond and his ex are rebuilding their friendship. “I can’t see the point in being filthy angry with anybody. All it does is eat you away as well.” But he’s adamant they’ll never get back together again. “Life’s too short, anyway.”

Christie agrees: “Life is too short to be angry, or sad, or lonely, or resentful, or unfulfilled.” By March 2020, Christie and Dan had found a new way of being. “We were starting to form the basis of our new friendship,” she says. And “we were co-parenting really well”. One month later, Dan was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, then 11 months later, he passed away. “It was so brutally fast,” recalls Christie. He was 54.

Alongside the grief, Dan’s passing ignited in Christie a desire to live life differently. “I had this really clear resolution, which I honestly feel was a gift from him, that I wanted to live very differently from that point on.” She wrote a list of things she wanted to do, experience or change. Today, Kate’s list is a structured set of goals and plans to achieve them. Earlier this year, she published a book on her new approach, called The Life List.

She found the act of writing cathartic. “Phenomenally healing.” It’s helped her order her thoughts into words and to reflect on her separation. She can now admit that she didn’t fight to save her marriage. “I didn’t once say to him, ‘Well, fall back in love with me honey, let’s work on this.’ I didn’t suggest counseling. I didn’t try and talk him out of it. I think I was relieved … I could get on with my own life.” She’s proud she found the courage to show her vulnerability. “We all have a backstory and I’m proud of myself for letting people in.”

Learning to let her guard down is something that 50-year-old Anne McCrea is struggling with after an irreparable breakdown of trust in her marriage. She and her husband had been married for 18 years. All in one moment, things fell apart. “I kind of just, you know, froze. I was at the beach with the kids and the dog and kind of just sat quietly crying to myself for a little while.”

Separating at this life stage can rarely be a clean or complete break. “We had to talk to each other, we had no choice. I couldn’t just ignore him; we had three children [aged 10, 15 and 18] that we needed to manage day to day.” McCrea adds, “so we kind of got functioning and working very quickly.”

Functioning included traveling with her ex-husband on a planned European family holiday shortly after her grandmother’s funeral. It would only be on their return that they would confirm what McCrea admits the kids already knew, that they were separating. But she insists, “it was good for them to see that we could travel together”. From day one, McCrea’s priority has been her children’s well-being and maintaining their bond with their father. “[Maybe] it’s not worth saving the relationship, but it’s worth saving the future for the kids, you know, so they don’t have to have those uncomfortable Christmases.”

After returning from Europe, McCrea was diagnosed with cancer. Treatment would delay her sharing the news of her separation with her parents. “It was at least another year before I actually told my mother and father.”

Dating and divorce parties

McCrea says her trust in people has diminished and she’s developed a “bullshit radar”. She’s kept some friends, made new ones and said goodbye to others she’d shared with her ex-husband for more than 25 years. Does she want to get married again? “Who knows?” She’s dating again but admits it’s hard. She’s pickier now. “Dating in your 50s is brutal.”

Raymond is also dating again. He’s listed on a couple of online dating sites and is hoping to find that someone special to travel and enjoy life with. But he’s found mature aged dating challenging. “There are a ton of nice ladies out there, but once bitten, twice shy.” Raymond sighs: “I’ll just plod along. I think she’ll have to trip over me.”

Christie’s updated goals include finding a new love. She’s proud she hasn’t rushed into anything. “I wanted a period of time to understand me and what makes me tick as a person on my own.” What she found was a woman who is confident, tenacious, resilient and happy. “We’ve had some really hard years, but I think that the sadness and loss has made me the strongest that I am. I feel great.”

McCrea is rebuilding her confidence. “It’s taken a bit of a beating.” In anticipation of receiving her divorce papers, she’s planning a party – a divorce party. “A celebration of the next phase and next chapter.” She’s looking forward to drawing a line under the last six years of separation. “I can’t change anything in the past. I can only change what I can for the future.” ~

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/nov/04/i-think-i-was-relieved-life-on-the-other-side-of-mature-age-divorce

*

In breaking marriage you break more than your own personal narrative. You break a whole form of life that is profound and extensive in its genesis; you break the interface between self and society, self and history, self and fate as determined by these larger forces. ~ Rachel Cusk

*

IN CASE YOU DIDN’T KNOW, HAMAS MAKES IT CLEAR

~ In an interview, Ghazi Hamad of the Hamas political bureau expressed the organization’s readiness to repeat the October 7 “Al-Aqsa Flood” Operation as many times as necessary, with the ultimate goal of Israel’s annihilation. Hamad emphasized that Palestinians are prepared to bear the costs and proudly sacrifice martyrs for their cause, […], stating that they view everything they do as justified.

(From United with Israel, Nov 1, 2023)

And here is that XXI-century idealist:

~ Henryk Grynberg, Facebook

*

A BETTER WAY TO ELIMINATE HAMAS (CNN opinion)

~ Israel’s strategy for defeating Hamas — destroying its military and political capabilities to the point where the terrorist group can never again launch major attacks against Israeli civilians — is unlikely to work.

Indeed, Israel is likely already producing more terrorists than it’s killing.

To defeat terrorist groups like Hamas, it is important to separate the terrorists from the local population from which they emerge. Otherwise, the current generation of terrorists can be killed, only to be replaced by a new, larger generation of terrorists in the future. (This is described by experts as “counterinsurgency mathematics.” )

Although the principle — of separating the terror group from the broader population — is simple, it is incredibly difficult to achieve in practice.

This is why Israel and the United States have waged major military operations that killed large numbers of existing terrorists in the near term — but ultimately led to the rise of many more terrorists, often in a matter of months.

Exactly this pattern happened in the past when:

1.) Israel invaded Southern Lebanon with some 78,000 combat troops and almost 3,000 tanks and armored vehicles in June 1982.

The goal was to smash PLO terrorists, and Israel achieved significant near-term success. However, this military operation caused the creation of Hezbollah in July 1982, led to vast local support for Hezbollah and waves of suicide attacks and ultimately led to the withdrawal of Israel’s army from much of southern Lebanon in 1985 and the growth of Hezbollah ever since.

2.) Israel maintained a heavy military occupation of Gaza and the West Bank from the early 1990s to 2005.

These operations succeeded in killing many terrorists from Hamas and other Palestinian groups, but also triggered vast local support for the terrorist groups and massive campaigns of suicide attacks against Israelis that stopped only when the heavy Israeli military forces left. Far from defeated, Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian elections.

3.) Israel launched a ground offensive into Lebanon in July-August 2006.

Although the goal was to completely destroy Hezbollah’s leaders and fighters so that it could never again kidnap Israeli soldiers and launch missiles at Israeli cities, the Israeli offensive failed, and Hezbollah is vastly stronger today as a result.

4.) The United States invaded and occupied Iraq in 2003 with 150,000 combat troops.

American forces completely defeated Saddam Hussein’s army within 6 weeks. However, these heavy military operations led to the largest suicide terrorist campaign in modern times, a major civil war in Iraq and ultimately, the rise of ISIS.

A US Marine pulls down a picture of Saddam Hussein at a school in Al-Kut, Iraq, 2003.

*

IS HISTORY REPEATING IN GAZA 2023?

In Gaza, this tragic pattern is probably already happening. Right now, we are witnessing not the separation of Hamas and the local population, but the growing integration of the two, with likely growing recruitment for Hamas.

The Israeli order for 1.1 million Palestinians — the population of northern Gaza — to move south is not going to create meaningful separation between the terrorists and the population.

Many thousands cannot move because they are too young, too old, or too sick or injured and dependent on specialized care and hospitals. Hence, evacuating the entire civilian population of northern Gaza is not possible. Even if the civilian population did move, many Hamas fighters would simply go with them.

Moreover, Hamas has ordered civilians not to evacuate. Since Hamas and the civilian population remain tightly integrated, it is no surprise that Israeli operations to kill Hamas terrorists has led to the death of over 8,000 civilians, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Health in Ramallah, citing sources from Hamas-controlled Gaza. Virtually all have family members who are already likely being recruited by Hamas in large numbers.

We should expect that Hamas is thus growing stronger, not weaker, with every passing day.

So, what does work?

To defeat terrorist groups, it is crucial to engage in long campaigns of selective pressure, over years, not simply a month (or two, or three) of heavy ground operations, and to combine military operations with political solutions from early on.

Indeed, the very effort to finish off the terrorists in just a month or two militarily with little idea of the political outcome — as Israel appears to be doing now — is what ends up producing more terrorists than it kills.

The only way to create lasting damage to terrorists is to combine, typically in a long campaign of years, sustained selective attacks against identified terrorists with political operations that drive wedges between the terrorists and the local populations from which they come.

Israel is drawing comparisons with the defeat of ISIS, but it is important to remember that Muslim ground forces made an enormous difference by applying military pressure against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, over years, in ways that did not galvanize the local population to replace them, by allowing the local populations to effectively govern the area cleansed of terrorists.

The campaign that defeated ISIS joined military and political operations together practically from the beginning.

Going forward, Israel needs a new strategic conception for defeating Hamas. The only viable way to separate Hamas from the local population is politically.

Israel’s strategic vision has been to go in heavily militarily first and then figure out the political process later. But this is likely to integrate Hamas and the local population together more and more and to produce more terrorists than it kills.

Furthermore, Israel doesn’t appear to have a political plan for the period after eliminating Hamas. Since 2006, Hamas has been the only government in Gaza. Israel claims it does not want to govern Gaza, but Gaza will need to be governed, and Israel has yet to explain what a post-Hamas Gaza will look like.

What will prevent Hamas 2.0 from filling the power vacuum? Given the absence of serious political alternatives to Hamas, why should Palestinians abandon Hamas?

There is an alternative: now, not later, start the political process toward a pathway to a Palestinian state, and create a viable political alternative for Palestinians to Hamas.

This could, over time, separate Hamas from the local population more and more, and so lead to significant success. It must be the Palestinians who decide who leads Gaza.

This new strategic conception is the best way to defeat Hamas, secure Israel’s population and advance America’s interests in the region. ~ Robert A. Pape, a professor of political science and director of the University of Chicago Project on Security and Threats. He is the author of several books on air power and terrorism, including “Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War.”

https://www.cnn.com/2023/11/01/opinions/israel-flawed-strategy-defeating-hamas-pape/index.html

Oriana:

For decades, some of the best minds have tried to offer solutions to the conflict — to no avail. Obviously, if the underlying idea of is the total elimination of the state of Israel, which came into being as a safe refuge from genocide, it’s a no-go from the start.

Joe:

Oriana:

You speak for an ideal: that everyone recognize that each ethnic group adds to the richness and flavor. America's greatness derives from its diversity, and no ethnic group should be put down.

Mary:

Arundhati Roy's words seem particularly relevant now...we certainly are witness to "unspeakable violence" that we must struggle to understand, and "never, never forget." After Hamas horrific attack on October 7 it seems futile and blind to talk of peace. Such evil cannot be tolerated--and I mean Evil..outside all laws of reason, justice and humanity. No one can excuse this under any circumstances. Innocents were violated, tortured and killed, bodies desecrated and brutalized, and all done with relish, with a demonic glee, with satisfaction in their own barbarism. Hamas stated goal, stated and repeated again and again, is the extermination of all jews and the jewish state.

Israel must take them at their words, judge them by their acts, and answer as they have done. Terrorists can't be bargained with, trusted, or allowed to flourish and continue in their stated goal of genocide. They have embedded themselves in the population, strategically, so that any action against them involves by necessity harm to the general population, including innocents. Not to act is only to invite them to more barbarism, more horrific evils, committed on their part not with reluctance but with relish.

I think the left sympathizers with Palestine are missing the necessities of this situation, the structure of this war. They make a false equivalency between Israel and a colonizer state. Hamas is not waging a revolution but a genocidal reign of terror. It sees advantage in the deaths of civilians — civilians they commanded not to flee, because those deaths are good propaganda to use against Israel. And that propaganda is working, is having an international effect in turning sentiment against Israel...accompanied by a frightening rise in open antisemitism and antisemitic attacks.

What is very telling is that bordering Arab nations do not want Palestinian refugees at all — because they are sure to come with embedded Hamas terrorists who have incited violence and conflict when allowed in before. Does the war radicalize, create more terrorists than it eliminates? That’s certainly a possibility. But there is no time and little appetite for a slow, years long campaign to separate the terrorists from the general population. That may be the only real solution, but the exigencies of war are making it less and less likely with every passing day.

*

WHY THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION IS DEAD (Jason Greenblatt)

I spent nearly three years at the Trump White House attempting to reach a peace deal between Israel and its Palestinian neighbors. But I always understood that among the many reasons it was unachievable then, and unlikely to be for the foreseeable future, was not just the seemingly unbridgeable positions on land, Jerusalem and other well-known obstacles. (Indeed, the peace plan we crafted was rejected by the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah before they even read it.)

Even if we had come up with a solution that was acceptable to the parties, though, there were still far too many Palestinians who were intent on massacring Jews and destroying the Jewish State of Israel.

That desire was on full display in October 7th unprecedented, devastating attack. Palestinian terrorists invaded Israel and killed at least 1200 people, wounded thousands and took hostage up to 200 (no official number has been released). The captives will surely be spread out and hidden all over the Gaza Strip, making their rescue extraordinarily challenging.

I was supposed to be in the Middle East this week for work, but postponed my trip in light of what’s going on. Almost every single one of my Arab colleagues and friends understood immediately why and expressed outrage, concern or disgust over what happened. Clearly, many Arabs oppose such horrific violence. But I also heard a minority of voices blaming Israel.

Unless and until Palestinians of good will and their leaders fully and unequivocally condemn and repudiate this hatred and the glorification of the slaughter of Jews, Palestinians will not achieve any of their aspirations because Israel cannot, and should not, compromise on the security of its citizens. No country should.

Israel cannot achieve peace with Palestinians when a segment of the Palestinian population still intends to destroy it. Israel cannot make peace when the leaders of the Palestinians include Hamas. Or when a member of Fatah, Hamas’ political opponent and the party that runs the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, expresses not sorrow over the loss of innocent life, but celebrates a “morning of victory, joy, and pride” and urges all Palestinians to participate in the terror against Israel.

Many of the would-be peacemakers I spoke to during my time in the White House ignored the deep-seated hatred in this subset of the Palestinian population intent on ruining any chance for peace.

They told me that as long as the Palestinians were given a fully autonomous state of their own, this would all go away, or they pretended away this hatred in the first place. After the events of the last few days, I think they finally have to accept the truth.

Israel, like communities of Jews throughout history, will always need to protect itself from haters. As a consequence, any solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, if ever one is to present itself, must always address the need for Israel to defend itself, control security over whatever the Palestinian areas might become and do what it needs to protect its citizens.

I am heartened by the tremendous support for Israel from around the world. Scenes of the Israeli flag being displayed on the façade of 10 Downing Street and on Germany’s Brandenburg Gate are inspiring in these dark days. As was President Joe Biden issuing strong, appropriate remarks. I hope this support will be unwavering and be followed up by serious assistance to Israel for whatever it needs. I hope the Biden administration also recognizes the Iranian regime’s suspected role in this carnage and acts accordingly.

Indeed, the focus of the world must be to support Israel in its quest to punish those who perpetrated these dastardly acts and to work to prevent attacks like this in the future. Any human being who values life must condemn these acts unequivocally, with no moral equivalence.

Accordingly, the world must recognize that Israel is now defending itself in Gaza, as any country would, and that the fault for the unfortunate casualties that will inevitably occur among innocent Palestinians lies with Hamas. War is a terrible thing. But it’s not Israel that asked for this war.

Those who gather in cities around the world to celebrate the death and destruction perpetrated by Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, including in my former home state of New York, are in essence saying they believe in the slaughter of innocent individuals, that it’s okay to shoot children in front of their parents, that it’s acceptable to parade women naked and to massacre grandparents.

They are saying that they are the enemy of Jews. But they are also saying that they are the enemies of peace and of the Palestinians as well for so deeply hurting their cause. These people should tell their loved ones, including their own grandparents, that this is what they stand for — death, destruction and misery. ~

https://www.cnn.com/2023/10/10/opinions/israel-gaza-hamas-biden-greenblatt/index.html

*

ISRAEL’S HIGH-TECH SECURITY SYSTEM

~ Over the last few years, Israel spent more than $1.1 billion to construct a sprawling security barrier along the entirety of its nearly 40-mile border with Gaza. This was, allegedly, to be the fence to end all fences. In addition to 20-foot-high multi-layered wire, steel, and concrete barriers, the “smart fence” integrated a vast network of cameras, motion and other sensors, radars, and remote-controlled weapon systems, all monitored by dozens of towers that served as data hubs and high-tech observation and listening-posts.

An underground wall and sensor system, designed to stop infiltration by tunnels, was extended far below the earth along the whole border, at great expense. Meanwhile, Israel’s advanced, exceptionally costly “Iron Dome” missile defense system protected the skies. “The barrier is reality-changing. What happened in the past won’t happen again,” the then-IDF chief of staff Aviv Kohavi declared at a ceremony marking its construction in 2019.

Some former members of the IDF have in recent days testified on social media that the fence really was a technological marvel. Not so much as a stray cat could get anywhere near the border without setting off alarms, they recalled. And the Israeli government and military certainly seem to have believed it was impenetrable, which partly explains why, by the start of this month, they had redeployed most of their regular military forces to guard the West Bank and northern border instead.

But of course, on 7 October, this great wall of silicon proved almost totally useless, overcome in a matter of minutes by Hamas, which was then left to rampage across southern Israel almost unopposed. At least 1,400 Israelis lost their lives as a result. What happened? Let’s lay aside Israel’s broader strategic intelligence failure — having been falsely convinced that Hamas had been successfully pacified and was no longer interested in attempting attacks — which this certainly was. The border’s defenses were expected to detect and repel even an unexpected assault — or at least were billed as such. How and why did they fail?

At the simplest level, we could say the IDF was overconfident in its defenses and underestimated its enemy. “The thinning of the forces [stationed near the Gaza border] seemed reasonable because of the construction of the fence and the aura they created around it, as if it were invincible, that nothing would be able to pass it,” recounts Brig. Gen. Israel Ziv, a former head of the IDF’s Operations Division and ground forces commander in the south.

We could also say that the IDF had allowed itself to become strategically rigid and was ill-prepared to adapt flexibly when things went wrong. From the moment the fence was proposed, some military officers warned that pouring resources into it — along with the Iron Dome — was a mistake, because it would ultimately degrade the military’s ability to maneuver offensively and pre-emptively neutralize the enemy’s capacity to conduct attacks.

Col. Yehuda Vach, commander of the IDF’s Officer Training School, warned in 2019 that “because we don’t cross the fence, the other side has become strategically stronger”, as they’d been handed operational initiative. “The enemy will seek in the next campaign to carry out an operation to kidnap soldiers and harm civilians in the towns near the fence, thus enjoying the first achievement of the campaign,” he ominously predicted. “The fence creates an illusion and gives a false sense of security to both the soldiers of the Israel Defense Forces and the residents near the fence,” he said.

These are both classic military mistakes, warned against repeatedly by strategists from Carl von Clausewitz to Sun Tzu. In this case, however, the even greater mistake may have been that the IDF came to rely far too heavily on technological solutions, methods, and ways of thinking.

One of the most famous sayings of the U.S. Air Force pilot and strategist Col. John Boyd, who helped to develop modern maneuver warfare, was: “People, ideas, machines — in that order!”

While war-fighting devices were and are important, as are doctrines, tactics, and stratagems, these are all less important than the people doing the fighting, planning, and organizing — as well as being far less adaptable and reliable. As Boyd would often harangue generals in the Pentagon, usually to no avail: “Machines don’t fight wars… Humans fight wars!”

Boyd had seen for himself the perils of over-reliance on Big Brain tech wizardry in Vietnam. The latest generation of US aircraft, designed by geniuses who insisted that the age of aerial gunfights was long over, had been stripped of their guns and maneuverability — and built to be flying missile and bomb platforms. But in combat, the missiles proved horrifically unreliable — and the planes were no use at all in a dogfight. When they ran into lightweight North Vietnamese MIGs, they got destroyed: the US air-to-air kill ratio fell from 10:1 in the Korean War to 1:1 in 1967.

While technologies can certainly offer solutions to discrete problems, they are typically not flexible and adaptable enough to function as intended when things go sideways. Moreover, fragile technological solutions can produce entirely new liabilities that did not even exist before. In the current case, the widespread reliance of the IDF’s defenses on wireless data transmission became a critical weakness that the enemy was able to exploit to great effect.

In fact, it seems likely that Israel was actually worse off with all its high-tech border gadgetry than it would have been without it. These over-engineered solutions to guarding the border were not cost-effective, instead representing an opportunity cost that could have been better spent elsewhere — such as on maintaining a far greater number of disciplined, sharp-eyed soldiers with guns. When the tech failed, it was only such men who were able, eventually, to adapt and respond. By reversing Boyd’s admonition and putting machines first and people last, the IDF actively degraded the capability of those people to respond to disaster when it most mattered.

But even this understates the bigger problem exposed by the folly of the “smart fence”. Israel’s smart border defenses should be understood as the adoption of a needlessly complex system. “Complexity” here must not be mistaken to just mean “complicated”. Rather, a complex system is a technical term defining a system composed of such a great quantity of component parts, in such intricate relationships of dependency and interaction with each other, that its composite behavior in response to entropy cannot be predictively modeled.

When things go wrong in a complex system it can’t be easily solved, because each sub-system relies on many other sub-systems, and pulling any one lever to try to solve one problem will produce entirely unexpected effects. This means complex systems are vulnerable to failure cascades, in which the failure of even a single part can set off an unpredictable domino effect of further failures. Even if the original failure is fixed this cannot reverse the cascade, and the whole system may soon face catastrophic collapse.

This is essentially what happened to Israel’s border defense system. The replacement of low-tech solutions with high-tech ones needlessly added additional layers of complexity to the system, making it more, not less, fragile. Under pressure, the system then collapsed more completely and with more devastating consequences than if a simpler, more robust system had been used.

On close inspection, those technologies that have the most transformative and lasting impact are almost always those that are the most simple, robust, adaptable, and scalable, and which generally work in accord with the human element, rather than attempt to totally replace him with a complex system. The cheap little drones that Hamas used so successfully, and which have already revolutionized warfare in Ukraine and elsewhere, are a perfect example of this.

This is true, too, beyond the world of warfare. In all aspects of life, we have come to worship technology and complexity for its own sake, believing it to be the sorcery that can solve our problems once and for all. Except far too often, it doesn’t — it just creates the illusion of having done so, while our own capacities have diminished and our vulnerabilities to systematic collapse have increased. In this way, technology has become a false idol, squatting in the place of or even preventing genuine human ingenuity, innovation, and adaptability.

Just as complex systems are vulnerable to collapse, so are empires and civilizations. And empires fall the same way most complex systems do: by becoming too complex to bear their own weight. They come to span the globe, and have too many alliances and commitments, too many “vital national interests”, too many IOUs, too many enemies, to ever handle at once. This is what “imperial overstretch” really means: not just that there is too much budgeted for the treasury to pay for, but that overall complexity has reached such a level that the empire has become impossible to manage. Trying to solve one problem only creates another. The empire may still appear strong, but it has become fragile. The potential for even a single point of failure to ignite a catastrophic failure cascade grows more and more acute.

Naturally, a wiser method would be to simplify: to deliberately pare back commitments and overextended positions, concentrating on conserving strength and defending only the most critical nodes of the system, until the balance of capabilities and commitments can reach a stable new equilibrium. But reform of this kind is extremely difficult, as untangling the imperial Gordian Knot one thread at a time often proves to be impossible. Historically, this type of impasse is typically only ever resolved, and simplicity restored, with one decisive stroke: by systemic collapse. ~

https://unherd.com/2023/10/israels-illusion-of-security/?tl_inbound=1&tl_groups

Dali: The Face of War, 1941

*

THE JEWISH DREAM AND THE JEWISH NIGHTMARE

~ In the Israeli imagination, this land should have been empty when Jews immigrated here to settle it in the first half of the twentieth century: the vacant land of Israel, waiting for its children to return to it after two millennia in exile, to find refuge from their troubles. This land, we were raised to believe, is the one place Jews can claim as their own, the one place where we belong.

But, as history would have it, the land was not empty and the people who lived here were reluctant to leave and hostile to the Zionist project. The existence of Palestinians in this land and their resistance to Israel was always seen as the main obstacle to realizing the Israeli dream, and Israel has responded to it by using force to push Palestinians away and to keep those who remain at bay.

The full acknowledgment of Palestinians as equal citizens would have required a substantial change in the conception of Israel as a Jewish project, while the founding of an independent Palestinian state would have required Israel to give up parts of the land that are also widely seen as essential to the Israeli project.

Furthermore, many Israelis see violent Palestinian resistance to the growing Jewish community in the first decades of the twentieth century and, later, to the founding of Israel in 1948 as proof that Palestinian political freedom poses an intolerable risk to Israel’s existence. What the majority of Israelis find impossible to accept is that many Palestinians see this land as their home— that those here are deeply committed to staying here and that those who are refugees aspire to return.

The conflict became even more acute when, in 1967, Israel conquered the West Bank from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, thereby taking control of millions of Palestinians, many of whom had escaped as refugees to Jordan and Egypt in 1948. Israel wanted the land it conquered, not the Palestinians who lived on it. Again, force was used to control and expel Palestinian existence without recognizing the basic rights of Palestinians, who have since lived under military rule in these territories and the overwhelmingly majority of whom were not granted citizenship.

In the 1990s, following the Oslo Accords, partial civil control over certain parts of the West Bank and Gaza was handed to the Palestinian Authority, a Fatah-controlled government body that, in many ways, serves as a contractor of the Israeli government.

In 2005 Israel dismantled its settlements in Gaza and withdrew its permanent ground forces, though it retained control of the borders, sea, air space, customs, currency, water and electricity supply, population registration, and much else. Two years later, after Hamas came to power in Gaza, Israel imposed a blockade, severely restricting movement of people and products into and out of the Strip. Periodically, Hamas has fired rockets into Israel, and Israel has conducted military campaigns in Gaza. Large-scale military campaigns occurred in 2008–9, 2012, 2014, and 2021.

Force has continued to be Israel’s primary mode of engagement with Palestinian existence in this land. But the force exercised against Palestinians, though often brutal, was restrained in various ways so as to accommodate—sometimes only in appearance—some of the demands of international law, Western politics, and Israelis’ own sense of justice. Most importantly, Israelis perceived Israel’s use of force as restrained.

Sometimes Israel’s purported restraint was a source of pride, other times a source of frustration. For example, in 1994, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin explained the importance of the newly formed Palestinian Authority by noting that, unlike Israel, Yasser Arafat could fight Hamas “without Bagatz [Israel’s supreme court] and Betselem [a prominent Israeli human rights organization]” — that is, without being constrained by legal and moral considerations. In other words, somewhat-restrained force was Israel’s modus operandi. The “Palestinian problem” was contained or managed, not resolved, but this was a compromise most Israelis felt they could live with. It is not so anymore.

If the Israeli fantasy has always been a land empty of Palestinians, the Israeli nightmare has always been a Palestinian massacre of Jews. The reason for Israel’s existence is said to be the prevention of such attacks on defenseless Jews. The October 7 massacre was the greatest, most damning failure of the State of Israel in this regard: its force was not enough to defend Israelis against their own nightmares. Immediately following the massacre, comparisons to the pogroms and the Holocaust were made. The massacre is, for us, the end of history: an event that refuted the premise of our existence in this place.

The conclusion most Israelis draw from this situation is not that the use of force is limited in what it can achieve, but that we were mistaken to ever limit our use of force to begin with (another fantasy, another nightmare). Many find it difficult not to interpret the events of October 7 as a decisive confirmation of the longstanding Israeli suspicion that the Palestinians will slaughter us if they get the chance — in other words, as proof that the existence of one people can only come at the expense of the other.

The fact that the Israeli nightmare became a reality leads many to conclude that the Israeli fantasy must also be achieved: we must use force to wipe “them” out, simply in order to survive.

But ethnic cleansing and genocide are not only morally reprehensible; they are impossible. Palestinians will continue to exist in this land, and there is nothing Israel can do about it. I think most Jewish Israelis know this, but given what happened, they find it impossible to accept. The compromise that allowed for some bare form of Palestinian existence under Israel’s rule of force can no longer be sustained, but the idea that force is our only savior is as entrenched as it ever was in the Israeli psyche.

I do not accept the dichotomy of recognition and the genocidal conclusion it leads to. I believe that force on its own is not power, and that power requires recognition of those who exist alongside us—recognition that their existence and dignity should be protected. To protect its own existence and dignity, Israel must fight Hamas while giving Palestinians hope for a decent life, hope for recognition without violence. We must not view the massacre of October 7 as an act committed by all Palestinians or as an expression of innate hatred of Jews, and we must not conflate it with the Palestinian demand for freedom, which is just.

And yet I confess that I too feel the widespread terror and panic that make such distinctions fall on deaf ears. I feel the terror of knowing it could have been me: I could have easily been one of the people who were slaughtered, one of the people kidnapped, one of the people who lost a child or a parent. Like most Israelis, I know people to whom this happened, and I know people whose friends and family were directly affected. I feel the terror, the grief, and the rage; I see these feelings in the eyes and movements of the people I meet; I hear these feelings in their voices.

When terror and brutality are as rampant as they are now, they possess us. Resisting them feels as futile as resisting a force of nature — a giant wave, an avalanche, a blizzard. We are compelled to exercise force by the force that terrifies us. Yet this observation, that we do not possess force but are possessed by it, is significant. It might, in the words of Simone Weil, “interpose, between the impulse and the act, the tiny interval that is reflection.” “Where there is no room for reflection,” Weil writes, “there is none either for justice or prudence.”

*

In The Iliad, or the Poem of Force, published in the winter of 1940, Weil argued that force is the true hero of the Iliad. Force determines human affairs, but it belongs to no one; even when it serves our ends, it is never ours: “Force is as pitiless to the man who possesses it, or thinks he does, as it is to its victims; the second it crushes, the first it intoxicates. The truth is, nobody really possesses it.

“When force is on our side, it blinds us to the existence of others and to our own vulnerability. Thus, the Iliad describes “men in arms behaving harshly and madly.” A sword driven into the breast of a disarmed enemy pleading at his knees; Achilles cutting the throats of twelve Trojan boys on the funeral pyre of Patroclus “as naturally as we cut flowers for a grave.” Under the spell of the force they exercise, these men cannot see that they, too, will succumb to force. “Thus it happens that those who have force on loan from fate count on it too much and are destroyed.”

In war, Weil says, force takes hold of us and traps us inside the terror of death. It effaces even its own goals as well as the notion of it ever coming to an end. This is not easy to understand. There is a rift between those who look upon war from the outside and those who inhabit it. “To be outside a situation so violent as this is to find it inconceivable; to be inside it is to be unable to conceive its end,” she writes.

In the presence of an armed enemy, what hand can relinquish its weapon? The mind ought to find a way out, but the mind has lost all capacity to so much as look outward. The mind is completely absorbed in doing itself violence. Always in human life, whether war or slavery is in question, intolerable sufferings continue, as it were, by the force of their own specific gravity, and so look to the outsider as though they were easy to bear; actually, they continue because they have deprived the sufferer of the resources which might serve to extricate him.

It is now 9 p.m., Thursday, October 19. The mind is doing violence to itself. We are inside war, inside terror, but we must envision the end of war and terror. We must ask ourselves how we can bring about a reality in which life is possible, and we must accept the unalterable fact that life will not be possible for us unless it be possible for those who share this place with us. In the words of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, translated by Munir Akash:

“It’s either him or me!”

That’s the way war starts. But

it ends with the embarrassing confrontation:

“Him and me!”

There is darkness outside and darkness inside, there is inconceivable loss, unfathomable evil. This land is beautiful and its people are good. ~

Oded Na’aman, Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is a longtime member of Breaking the Silence, an Israeli non-governmental organization established in 2004 by veterans of the Israel Defense Forces. It is intended to give serving and discharged Israeli personnel and reservists a means to confidentially recount their experiences in the Occupied Territories (Wikipedia)

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/letter-from-israel/

*

DO ISRAEL’S CRITICS UNDERSTAND EVIL?

~ After the Holocaust, academics and others tried to make sense of the murder of six million Jews. Historians pointed to the rise of nationalism following the First World War; the dismal state of the German economy when Hitler rose to power; the dehumanizing abstraction of Enlightenment rationality. Some rabbis argued that the Holocaust was a punishment from God, but they could not agree on why it was merited. Was it because the Jews of Europe sought to found a state of their own? Or because they didn’t? Others more prudently followed Wittgenstein’s observation: “That of which we cannot speak, we must consign to silence.”

Many historical and societal factors set the stage for the Holocaust. But none of these, individually or collectively, can explain the kind of violence to which the Nazis subjected their Jewish victims.

Jewish children and babies were, for a time, thrown alive into fire pits at Auschwitz. It has been calculated that, in this manner, the SS saved approximately two-fifths of a cent per child on Zyklon-B, the insecticide they used in the gas chambers. Were the children burned alive to save money? It would be obscene to suppose that economy explains such a horrific method of murder. The same holds for sealing people in a boxcar for as much as a week without telling them to bring water and food, neither of which the Nazis provided. Or sewing twins together back-to-back, as Dr Mengele once did at Auschwitz. (Gangrene immediately set in and they died in three days.)

In fact, nothing could explain such abominations. Primo Levi’s distinction between “useful” and “useless” violence makes this clear. Useful violence has an aim outside itself. A thief kills a witness to a crime in order to avoid capture. The victim would otherwise have been unmolested, but was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Such violence is evil, but useful in that it serves a purpose outside of itself. The thief might say: “I never wanted to hurt anybody, but then she came out of the back.” Perhaps he really is just unusually callous and stupid; he didn’t go looking for evil, but he found it. This explanation makes some sense, but does not excuse: the thief is going to prison for homicide, and rightly so.