*

THE ANGEL IN SAN FRANCISCO

In San Francisco an angel

bears a fluted holy water conch —

a marble smile, celestial.

The Golden Gate Bridge

departs into fog, a harp of bones

of builders and suicides.

Cloud-eaten hills,

views of Alcatraz;

drunks grinning to themselves

in Victorian doorways.

Angel, you smile as if you knew

beauty is the sole excuse.

The city rises, half-dream, half-fog,

here on the slippery

ledge of the continent.

Seagulls blur with white sails.

At the Palace of Fine Arts,

a bronze Perseus lifts

the head of the Medusa,

though he himself is headless.

But you, mild angel, bless

all who enter the dim vestibule.

At the tomb of a dead god,

you change stone into hope.

~ Oriana

*

OLIVER SACKS ON FACING DEATH

“I have been increasingly conscious, for the last 10 years or so, of deaths among my contemporaries. My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself. There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.

“I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.” ~ Oliver Sacks

*

WILLIAM SHATNER ON HIS EXPERIENCE OF GOING INTO SPACE

“Last year, I had a life-changing experience at 90 years old. I went to space, after decades of playing an iconic science-fiction character who was exploring the universe. I thought I would experience a deep connection with the immensity around us, a deep call for endless exploration.

"I was absolutely wrong. The strongest feeling, that dominated everything else by far, was the deepest grief that I had ever experienced.

"I understood, in the clearest possible way, that we were living on a tiny oasis of life, surrounded by an immensity of death. I didn’t see infinite possibilities of worlds to explore, of adventures to have, or living creatures to connect with. I saw the deepest darkness I could have ever imagined, contrasting so starkly with the welcoming warmth of our nurturing home planet.

"This was an immensely powerful awakening for me. It filled me with sadness. I realized that we had spent decades, if not centuries, being obsessed with looking away, with looking outside. I did my share in popularizing the idea that space was the final frontier. But I had to get to space to understand that Earth is and will stay our only home. And that we have been ravaging it, relentlessly, making it uninhabitable.” ~ William Shatner, actor

Joe: SHATNER VERSUS NIMOY; MANIFEST DESTINY

William Shatner has had a change of heart, and that is good. Leonard Nimoy was the one who lived a socially conscious life after leaving Star Trek TV and movies. Leonard returned periodically to the franchise, but he spent most of his life as an artist, a reader of classic prose and poetry. He was active in social justice causes and educating the public about respecting human, animal, and plant life.

Nimoy quit Star Trek because he felt the producers were using the show as a euphemism for Manifest Destiny. They allowed the show to drift from the theme of exploration to conquest. They stopped using logic to promote Democratic ideals and began using force to convince the natives of foreign planets to become a democracy. The writers used Puritans’ belief that if we think you are wrong, we have the right to force you to change.

Inhabitants who resisted the Federation’s demands were treated the way the United States dealt with Native Americans. Roger Williams documented his type of Puritan behavior after his banishment from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for his religious views of tolerance. Today, we see this behavior in conservative Christians, who use the Second Amendment and employ guns to intimidate those with whom they disagree.

Leonard wished that Star Trek would use statesmanship and science to help the inhabitants of distant planets move toward democracy. He agreed to reappear if Spock became a wise sage and advised his younger self to solve problems with a logic based on interpreting science through a Buddhist lens. Nimoy meant us to understand the harm we inflict on each other and the planet and respond to it directly with respect.

Unlike Nimoy, Shatner used his celebrity to promote his Captain Kirk franchise. He allowed himself to be the promoter of capitalism without regard for the social consequences. Therefore, it was no surprise that Elon Musk gave William a free ride in his spaceship, and after returning to Earth, Shatner said that it was great for industry (capitalism) to develop the last frontier, meaning to exploit the universe for profit.

Like many children of the 50s and 60s, I grew up admiring William and Leonard. I understand the look on Shatner’s face when Musk used him and abandoned him in front of the news cameras. Elon’s mistreatment of Shatner was sad. Now, I welcome Captain Kirk to the fight. Because we lack money, we use statesmanship to protect this tiny oasis in the middle of a desert that we named Space.

Oriana:

Yes, it seems that going into space, even to a limited degree, taught us that earth is unbelievably precious — indeed an oasis in the middle of an almost infinite cosmic desert. And, sci-fi movies to the contrary, it appears plausible that we are alone. Intelligent life may indeed exist on some distant planet — but cosmic distances are too great to allow for meaningful contact.

*

WRITERS MEETING CUTE

In 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald sent Edith Wharton, then in her sixties, a copy of his newly-published novel The Great Gatsby. She responded with a letter. “I am touched at your sending me a copy,” she wrote, “for I feel that to your generation, which has taken such a flying leap into the future, I must represent the literary equivalent of tufted furniture and gas chandeliers.” She praised the book, and invited Fitzgerald and Zelda to come up for tea or lunch.

Apparently, Zelda refused, feeling that she would be made to “feel provincial,” and so Fitz went with Teddy Chanler, a mutual friend of he and Wharton’s. But first, obviously, he got drunk. Quite drunk. According to Arthur Mizener’s account of the tea, Fitzgerald first insulted Wharton, then tried to shock her and her other fancy guests with a story about how he and Zelda lived for two weeks in a bordello. Wharton was not shocked. “But Mr. Fitzgerald,” she said when he began to lose his nerve, “you haven’t told us what they did in the bordello.”

Later, Wharton dashed off an entry in her diary: “To tea, Teddy Chanler and Scott Fitzgerald, the novelist—awful.”

Marquez and Hemingway

When Gabriel García Márquez was 28, he saw Ernest Hemingway on the street in Paris. I’ll let him tell the rest:

I recognized him immediately, passing with his wife Mary Welsh on the Boulevard St. Michel in Paris one rainy spring day in 1957. He walked on the other side of the street, in the direction of the Luxembourg Gardens, wearing a very worn pair of cowboy pants, a plaid shirt and a ballplayer’s cap. The only thing that didn’t look as if it belonged to him was a pair of metal-rimmed glasses, tiny and round, which gave him a premature grandfatherly air. He had turned 59, and he was large and almost too visible, but he didn’t give the impression of brutal strength that he undoubtedly wished to, because his hips were narrow and his legs looked a little emaciated above his coarse lumberjack shoes. He looked so alive amid the secondhand bookstalls and the youthful torrent from the Sorbonne that it was impossible to imagine he had but four years left to live.

For a fraction of a second, as always seemed to be the case, I found myself divided between my two competing roles. I didn’t know whether to ask him for an interview or cross the avenue to express my unqualified admiration for him. But with either proposition, I faced the same great inconvenience. At the time, I spoke the same rudimentary English that I still speak now, and I wasn’t very sure about his bullfighter’s Spanish. And so I didn’t do either of the things that could have spoiled that moment, but instead cupped both hands over my mouth and, like Tarzan in the jungle, yelled from one sidewalk to the other: ”Maaaeeestro!” Ernest Hemingway understood that there could be no other master amid the multitude of students, and he turned, raised his hand and shouted to me in Castillian in a very childish voice, ”Adiooos, amigo!” It was the only time I saw him.

Roald Dahl and Kingsley Amis

Roald Dahl and Kingsley Amis met at a party thrown by Tom Stoppard in 1972, and they did not get along. Apparently, Dahl immediately began talking about money, and suggested to Amis that if he really wanted to make the big bucks as a writer, that he should try his hand at writing books for children. The tension was palpable. Donald Sturrock, Dahl’s biographer, wrote that “Amis, who had no interest in children’s fiction, felt he was being patronized by Dahl’s suggestion that his own writing was not bringing him enough money. Dahl, for his part, was in precisely the kind of English literary environment he loathed. He knew that Amis, like most of the guests, did not respect children’s writing as proper literature and this attitude made him feel vulnerable.”

According to his memoirs, Amis demurred, “I’ve got no feeling for that kind of thing,” and Dahl retorted, “Never mind, the little bastards’d swallow it,” before jumping into his helicopter and leaving the scene. “I watched the television news that night,” Amis writes, “but there was no report of a famous children’s author being killed in a helicopter crash.”

Haruki Murakami and Raymond Carver

Murakami was obsessed with Carver long before the two writers met—according to the Seattle Times, it only took reading two of his stories (“So Much Water So Close to Home” and “Where I’m Calling From”) to convince Murakami that Carver was a genius. Murakami, who had already published a couple of novels, which hadn’t yet been translated into English, began to read and translate all the Carver he could get his hands on. So when Murakami asked Carver for a meeting, the latter agreed. Murakami and his wife came to the United States for the first time, visiting two places: Princeton, because it was the alma mater of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Carver’s home in Washington.

They got along, and afterwards, Carver wrote a poem that he dedicated to Murakami. It begins: “We sipped tea. Politely musing / on possible reasons for the success / of my books in your country. Slipped / into talk of pain and humiliation / you find occurring, and recurring, / in my stories. And that element / of sheer chance. How all this translates / in terms of sales.” Carver also promised to visit Murakami in Japan, and reportedly, Murakami and his wife had a bed specially made to accommodate Carver’s large size—but he never came. He died in 1988.

Somehow, at no point during his visit did Murakami tell Carver that he was a writer too. “I guess I should have done that,” he told the Harvard Crimson in 2005. “But I didn’t know he would die so young.”

Rudyard Kipling and Mark Twain

In 1889, a 23-year-old Rudyard Kipling decided to track down Mark Twain, whom he much admired. After much contradictory advice and rumor-chasing, he made his way to Elmira, where a “friendly policeman” told him that sure, he’d seen Twain—“or some one very like him driving a buggy the day before.” Kipling recounts approaching his prey in his essay on the subject:

Then he was within shouting distance, after all, and the chase had not been in vain. With speed I fled, and the driver, skidding the wheel and swearing audibly, arrived at the bottom of that hill without accidents. It was in the pause that followed between ringing [Twain’s] brother-in-law’s bell and getting an answer that it occurred to me, for the first time, Mark Twain might possibly have other engagements than the entertainment of escaped lunatics from India, be they never so full of admiration. And in another man’s house—anyhow, what had I come to do or say? Suppose the drawing-room should be full of people—suppose a baby were sick, how was I to explain that I only wanted to shake hands with him?

Well, there was no sick baby, and Mark Twain welcomed Kipling in, much to Kipling’s delight. “This was a moment to be remembered,” he wrote, “the landing of a twelve-pound salmon was nothing to it. I had hooked Mark Twain, and he was treating me as though under certain circumstances I might be an equal.” But seventeen years later, after Kipling had become famous, Twain had become one of his biggest fans. Show me a salmon that could do that.

Harper Lee and Truman Capote

What’s meet-cuter than the boy next door? When Harper Lee was six, and still going by Nelle, a boy named Truman moved in next door to her family’s home in Monroeville, Alabama. They were total opposites: she an oft-barefoot tomboy running wild, he a clotheshorse who always had a book in his hand. But they were both unlike anyone else in their town, and they both loved Sherlock Holmes, and so they became fast friends. “Nelle was too rough for the girls, and Truman was scared of the boys, so he just tagged on to her and she was his protector,” said one family friend. The rest is history—catty, competitive history, but history nonetheless.

Edward Said and Jean Paul Sartre (+ Simone de Beauvoir + Michel Foucault)

In early 1979, Edward Said received a telegram from Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre, inviting him to “attend a seminar on peace in the Middle East” that March. “At first I thought the cable was a joke of some sort,” Said wrote in the London Review of Books. “It might just as well have been an invitation from Cosima and Richard Wagner to come to Bayreuth, or from T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf to spend an afternoon at the offices of the Dial.” Once he realized that the message was legit, he quickly accepted and readied himself to travel to Paris.

When I arrived, I found a short, mysterious letter from Sartre and Beauvoir waiting for me at the hotel I had booked in the Latin Quarter. ‘For security reasons,’ the message ran, ‘the meetings will be held at the home of Michel Foucault.’ I was duly provided with an address, and at ten the next morning I arrived at Foucault’s apartment to find a number of people—but not Sartre—already milling around. No one was ever to explain the mysterious ‘security reasons’ that had forced a change in venue, though as a result a conspiratorial air hung over our proceedings.

Beauvoir was already there in her famous turban, lecturing anyone who would listen about her forthcoming trip to Teheran with Kate Millett, where they were planning to demonstrate against the chador; the whole idea struck me as patronizing and silly, and although I was eager to hear what Beauvoir had to say, I also realized that she was quite vain and quite beyond arguing with at that moment. Besides, she left an hour or so later (just before Sartre’s arrival) and was never seen again.

When Said finally met Sartre, he was no less disappointed. “Sartre’s presence, what there was of it, was strangely passive, unimpressive, affectless,” he wrote. “He said absolutely nothing for hours on end. At lunch he sat across from me, looking disconsolate and remaining totally uncommunicative, egg and mayonnaise streaming haplessly down his face.

I tried to make conversation with him, but got nowhere. He may have been deaf, but I’m not sure. In any case, he seemed to me like a haunted version of his earlier self, his proverbial ugliness, his pipe and his nondescript clothing hanging about him like so many props on a deserted stage.” Sartre died a year later.

Marcel Proust and James Joyce

Proust and Joyce met when they were set up on a blind date of sorts—a four-way blind date that also included Pablo Picasso and Igor Stravinsky. The party was arranged by British art patrons Sydney and Violet Schiff, who had, according to Craig Brown’s Hello Goodbye Hello, “been plotting to gather the four men they consider[ed] the world’s greatest living artists in the same room.” Proust showed up around 2:30 in the morning, and when Joyce woke up, they were introduced. There are many accounts of what followed, but all of them are bad.

Joyce told his friend Frank Budgen that “Our talk consisted solely of the word ‘No.’ Proust asked me if I knew the duc de so-and-so. I said, ‘No.’ Our hostess asked Proust if he had read such and such a piece of Ulysses. Proust said, ‘No.’ And so on. Of course the situation was impossible. Proust’s day was just beginning. Mine was at an end.” But William Carlos Williams and Ford Maddox Ford, who were both on hand, agree that the two men did exchange more words than that—if only about their many complaints and illnesses.

Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens

Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens met in 1851 when they were introduced by their mutual friend, Augustus Egg. If that isn’t cute enough for you, they were introduced because Egg had recruited the 27-year-old Collins for Dickens’s amateur theater group. Together, they put on a production of Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Not So Bad as We Seem later that year, and became best friends in the process. (Edward Bulwer-Lytton, in case you don’t know, is the fellow who first wrote “it was a dark and stormy night,” as well as “the pen is mightier than the sword.” No one reads him now.)

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-time-murakami-met-carver-and-other-literary-meet-cutes?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

*

PRIGOZHIN’S GANGSTER CULTURE LIVES ON

~ For a moment it seemed that an actual gangster could take on a gangster state. Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian criminal who had served time and spoke in prison slang, thought he could compete with the suit and tie lawyers of Russia’s criminal regime. Just two months ago he was leading his army of mercenaries in a march on Moscow, challenging the authority of the army leadership, claiming he could wage Russia’s imperial, genocidal war against Ukraine better than they could, implicitly questioning Putin’s power. Now, Prigozhin and his lieutenants have been assassinated, their plane crashed outside of Moscow. The assumption is this is Putin’s revenge. But Prigozhin, or rather what he represents, have a larger victory that will outlive the man.

Prigozhin had been such a role model for your average Russian criminal: he’d started in a Soviet prison cell for robbery and risen to a lifestyle of gold-plated riches and Kremlin access. Though he has been killed, the prison and gangster culture that Prigozhin is an expression of has consumed the state. A Soviet joke used to describe the gulag system of labor camps as the ‘little prison’ (Malaya Zona) and the Soviet Union as the ‘big prison’ (Bolshaya Zona)—now the small prison has swallowed the larger one.

There’s a reason for this. In the ceaseless chopping and changing of Russian history—with its regular revolutions where the past is constantly re-written; where people are deported and moved across Eurasia in brutal population shifts; where whole peoples have been wiped out and their memories erased; where identity is constantly being remolded by the latest propaganda—prison culture is one of the few constants. From the time of the tsars to the Soviet Union and Putin’s post-modern dictatorship one thing you can rely is getting banged up in a fortress-prison; banished to a labor camp in Siberia; sentenced to the gulag.

Today Russia has the highest rates of prisoners in Europe. While other things in Russia change, prison culture maintains its traditions: hierarchy; codes of loyalty; adherence to authority. At the top of the avtoretiti (authorities), the 'thieves in law’ (vory v zakonye), under which come the "friars," and all the way down to the lowest of the low, the "cockerels", who have their own hierarchies. It has its own rules (zakoni) which you dare break, its own ways to deal with tensions, its own economy based around a sort of criminal sovereign wealth fund (obschyak). It has its own elaborate slang (Fenya). When Prigozhyn launched his quickly abandoned march on Moscow in June his mercenaries, many of whom were convicts he had offered the chance to escape prison by serving in the "meatgrinder" of Ukraine, expressed their support to his avtoritet in Fenya.

In the 1990s, when Russian society was in flux, where the status and solidity of old Soviet social categories, professions, and role models collapsed, criminals were one of the few groups who knew who they were. They could organize, they had a code of violence that passed for structure. In the absence of cops and courts they became the guarantors of business deals (and if you didn’t cut them in they would kill you). From being the dregs of society they became figures of aspiration: kids from nice families aped the way they talked and walked.

When Putin came to power the state resumed the role of master criminal. Just as it had been in the Soviet Union. The secret services took over curating the gangster’s businesses—and took their cut. But the cultural cachet of gangsters continued. Putin—an uncharismatic spy with a law degree who had become a corrupt bureaucrat managing relations with St Petersburg gangsters—imitated their slang when he talked of taking out terrorists "in the shitter." He talked to his governors and ministers down a long table like a mafia boss running a meeting of the Five Families.

When he announced he had ideology he called it "conservatism,"—but one of the few true conservative, as in constant, traditions in Russia is prison culture. Putin’s attacks on LGBTQ people is not informed by religion, Russia is among the least church-going nations. But the passive gay man is the lowest in the prison hierarchy, "the cockerel." So Putin’s anti-LGBT media drives resonated in a nation infused with prison "values." Even Putin’s idea of international relations reflects prison. For Putin you are either a country that dominates or is dominated by others, a thief-in-law or a cockerel.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine attempts to export this prison culture, to expand the Zona. When Russia occupies new territory it appoints local criminals as de facto administrators. Take Vovchansk, a small Ukrainian town just a few kilometers from the border with Russia that was occupied between February and September 2022—and where I was when the news of Prigozhyn’s death came through. When the Russians arrived in Vovchansk a local criminal, nicknamed Chizh, volunteered to be their enforcer. Recently released from prison, he used the new found power to extract money from the locals. The Russian occupiers used him for a while, then sidelined him as they sealed their grip, and proceeded to imprison, torture, and maim anyone they felt like—just to show who was really in charge.

The FSB, the successor to the KGB, soon became the most important authority in the occupied territories. The tradition of the secret police who arrest and oppress ordinary people is almost as constant as that of prisoners—from the tsarist okhranka through the Cheka and the NKVD. In the Gulag the prisoner slang for a particularly effective prison administrator was ‘Old Chekist’. The Old Chekists are still ultimately in charge.

But Putin still had to pay his respects to Prigozhin even after having likely killed him, calling him a “talented businessman” who had “made mistakes.” While many other social groups have atrophied or been rendered powerless, Russia’s secret police and their gangster-prisoners remain, winking at each other in mutual recognition across the centuries. ~

https://time.com/6309039/prigozhin-death-russian-prison-culture/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=sfmc&utm_campaign=newsletter+brief+default+ac&utm_content=+++20230829+++body&et_rid=240553319&lctg=240553319

*

RUSSIA AND THE PRISON CULTURE: MURDEROUS MACHISMO (‘WET WORK’ = KILLING)

Prigozhin’s criminal background—he served time in prison and seems to have killed someone in his youth—was another feature of the Russian power culture. It was the Bolsheviks who merged criminal culture with that of the state. The revolutionary Sergei Nechayev had declared in his 1869 Revolutionary Catechism that “We must unite with the world of adventurous gangs of criminals, the only genuine revolutionists in Russia”—an idea that influenced Lenin, Stalin, and their generation.

Once in power, they endowed their new secret police the Chekas with powers of arbitrary violence unthinkable in the era of the tsars. The Romanovs under Nicholas I had invented modern secret police organs but for all their violent suppression of rebellions, they rarely assassinated enemies or traitors outside or inside Russia. Lenin and Stalin disdained their softness: the end always justified the means.

Before power Stalin raised cash in spectacular bank robberies and protection rackets while liquidating traitors. In power, their Cheka harnessed the esprit of a military-religious order of knights with the atrocious violence of a gangster hit squad. Even as Cheka developed into a vast bureaucracy of the NKVD and later the KGB, it became the elite corps of Soviet state.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, KGB officers, now working for the new organs the FSB and the SVR, regarded themselves as knights—what their director, and now one of Putin’s top henchmen, Nikolai Patrushev, called a new nobility but it was a nobility that encompassed the corruption, greed and murderousness of a Mafia family.

Russian rulers must always exist in a state of ferocious vigilance. The direction of secret police organs is almost their first duty and perennial interest. But also espionage is thrilling for leaders— it is one of the exciting parts of the job for any leader, even in democracies. Stalin personally ran the organs himself, directing everything through henchmen, most famously two NKVD commissars, Nikolai Yezhov, who was untalented, unstable and always out of his depth, and Lavrenti Beria, his fellow Georgian who was highly capable, efficient and sadistic—and almost managed to succeed Stalin as Soviet leader. But Stalin’s NKVD potentates were much more important than Prigozhin— they managed vast organs and many millions of people.

Stalin believed killing was an invaluable political tool—boasting to his Bulgarian ally Georgi Dmitrov—“we do it by bloodletting”—but he was also fascinated by Wet Work, enjoying the devising the complex murder plots such as the killing in a "car accident" of the beloved Yiddish Soviet actor Solomon Mikhoels who was actually kidnapped, given a fatal injection and then placed n the street to look like the victim of a car crash.

The violence that Prigozhin flaunted was very much a part of Putinist culture as it was in Stalin’s time: Putin has never approached the scale of repression that Stalin unleashed during collectivization, his famines and then his Terror. The death toll runs into untold millions—it will never be exactly known.

It is a different time now and Putin is not Stalin in many ways. But targeted killing has always been part of his system: his accession saw a spiral of killings of his enemies or inconveniences to his power, from that of Galina Starovoitnova, the Duma member who promoted western democracy when he was still FBS director, to Anna Politovskaya, the investigative journalist, in 2006 and ex-deputy-premier and critic Boris Nemtsov in 2015, and famously the poisoning of his chief opposition Alexei Navalny in 020. Abroad, dissidents and double-agents from Alexander Litvinenko to Sergei Skripal were targeted for murder with exotic poisons from the biological weapons laboratory.

Since the Ukraine war started, destabilizing and reshaping the secretive tournament of rivals and clans into a frenzied cagefight for money and power, the killing spiral has become unpredictable and widespread: bankers, oil executives, bureaucrats—and sometimes as a gruesome warning, their mistresses—have been murdered—thrown out of windows, drowned in pools, poisoned. Many businessman who expressed skepticism about Putin’s war now found that their rivals—who many well have been FSB potentates—could forcefully grab their companies and sometimes liquidate them, too.

Putin proudly declared in 2018 that betrayal of the secret services was unforgivable and however long it takes, the state and the Organs will take vengeance. Putin and his Chekist potentates adopted the old Stalinist rule that any traitor must be hunted down and killed. The secret police always followed this rule, even spreading the rumor that the '60s double agent GRU Colonel Oleg Pentkovsky was executed by being incinerated alive at a secret police crematorium in a ceremony attended by selected officers. It may even be true.

Every autocrat identifies totally with the state and its servants: Putin does not need to choose between state and personal betrayal. But treason is even more bitter if the traitor is a personal friend and protégé like Prigozhin. Peter the Great was outraged by the betrayal of his close long-serving ally Ivan Mazeppa, the Ukrainian Cossack Hetman of Zaporizhian Host and Left-Bank Ukraine for twenty years. His story is very relevant today. Mazeppa feared that Peter was about to grant the Hetmanate to his intimate Russian friend Prince Menshikov so when the Swedish King Charles XII invaded Ukraine in 1708, Mazeppa agonized what to do. Charles offered him independence. Mazeppa defected to the Swedes. Peter was incensed and sent Menshikov to liquidate everyone in Mazeppa’s capital. He was keen to kill Mazeppa too but the Hetman died of natural causes soon after he and Charles lost the battle of Poltava in 1709.

Even more personal was the betrayal of Peter by his own eldest son who plotted against him and then defected, escaping to Vienna in 1716. Peter lured him back promising security—but on his return he tortured him to death. Peter is Putin’s hero. Photographs of his sumptuous yacht were revealed by opposition researchers online and even there he had a statuette of the first emperor of Russia. No matter how close the traitor, the traitor had to die.

Prigozhin was an intimate courtier of Putin and it seems that Putin continued to protect Prigozhin even when he was ranting in his baritone roar against Shoigu and Gerasimov as they played political games, starving his Wagnerians of ammunition and support. But sometime in the meatgrinder of Bakhmut, the desperate fray turned his head: Prigozhin started to identify himself and his Wagner troopers as blood-spattered heroes of Russia’s war against Ukraine —and anyone who held them back as traitors to the Motherland—even Shoigu, maybe even the President himself. Some of the Russian Army’s best fighting generals—General Armageddon Surovikin the most prominent—sympathized with Prigozhin and despised the cowards at headquarters.

The rebellion of June 23 this year crossed every line. It was a humiliation for the President. Not just the personal betrayal of Putin’s protégé on whom he and the state had showered billions but also a political betrayal that exposed to the world the incompetence and corruption of Putin’s command and conduct of the war. Putin spoke of Prigozhin with almost paternal sadness like a son he had had to sacrifice: "I have known Prigozhin from the beginning of the 1990s," Putin said with a strange wistfulness. "He was a man with a complex fate. Sometimes he made mistakes; sometimes he got results--for himself and in response to my requests, for a common cause. He was a talented person.”’

No one believed Prigozhin would remain amongst the living for long. Putin could not punish Prigozhin until the Wagner group was pacified and until he had identified, arrested, and dismissed any sympathetic generals. It seems Surovikin was arrested and sacked as commander of air defense the day before Prigozhin flew too close to the sun.

Then Putin received Prigozhin at a meeting of Wagner commanders. That must have taken some of his arctic self control. He allowed Prigozhin to appear on the sidelines of his conference with African leaders, many of whom would have known the condottiere since Wagner troops were present in their countries. A week ago, Prigozhin was reportedly in Africa, probably Mali boasting that Wagner was “making Russia even greater on all continents, and Africa even more free.” He growled that “the temperature is plus 50 degrees Celsius” in Mali but he did not realize it was getting even hotter at home…

It is said that the FSB had urged Putin to let him liquidate Prigozhin at once; Putin was more cautious. There were loose ends to tie up. But also there was something else there: he was teasing the loudmouthed braggart Prigozhin, letting him feel safe and preen on his online channels, even flaunt that he was still alive, still in business. Stalin did the same with his enemies such Nikolai Bukharin who reflected sadly that Stalin was a “master of dosage.” Putin too is a master of dosage.

In Russia, the mystique of power—from Peter the Great to Lavrenti Beria and on to Putin today—is often won by the capricious deployment of violence. Now with this killing, Putin has to some extent restored his mastery. If Prigozhin was indeed on the plane this was an execution plain and simple. It was not just a bullet in the head but a spectacular strike. It was a state hit—Wet Work gone large. Yet this turbulence in the inner circle, the rise of warlords, the open feuding, the killings, the rebellion by a protégé, now the execution of a courtier by his master—all of this augers ill for Russia and presages the deterioration of the Russian state. Perhaps even a new Smuta—the Time of Troubles that almost destroyed Russia in the civil wars of 1598-1613 and again in 1918-21.

Wagnerites may seek their own vengeance: what if they have admirers in say Putin’s bodyguards? And amongst his exploits Prigozhin has broken Putin’s myth of invulnerability and the taboo against elite revolt. Ultimately if the tsar stumbles it will be those closest who wield the dagger.

Putin is again the master of violence but he is damaged. Yet a weakened tyrant can rule for a long time. And war grinds on…

https://time.com/6308185/yevgeny-prigozhin-death-vladimir-putins-power/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=sfmc&utm_campaign=newsletter+brief+default+ac&utm_content=+++20230826+++body&et_rid=240553319&lctg=240553319

SOVIET HUMOR

Soviet humor is like Soviet bread.

Is dark. Is coarse. And not everyone gets it.

Miss Stripewell:

Don’t they say the same about the Soviet toilet paper? It’s dark, it’s coarse and not everyone gets it.

*

Three men are sharing a cell in a Soviet prison. To pass the time, they are sharing stories of why they are there.

The first man said: “I arrived for work one day five minutes late. I was told that such intolerable inefficiencies might someday cause the West to catch up with us! And so they threw me in prison.”

The second man said: “I arrived for work one day five minutes early. I was told that I must surely be conspiring to overthrow the government! And so they threw me in prison.”

The third man said: “I arrived for work one day on time.”

The other two look at him quizzically and ask: “And?”

“And they kept asking me, over and over: ‘Where did you steal the watch???’ “ ~ Daniel Schwartz, Quora

more from Daniel:

Mikhail Gorbachev, as leader of the Soviet Union, was once asked by a Western reporter (through an interpreter) about the economic future of the Soviet Union. He smiled and said, “You know, there’s a joke that they tell in my country.

“They say that the American President, Ronald Reagan, has one hundred security advisers. — One of them is a terrorist… but he doesn’t know which one.

“They also say that the French President, Francois Mitterrand, has one hundred lovers. — One of them has AIDS… but he doesn’t know which one.

“And they also say that I, Mikhail Gorbachev, have one hundred economic advisers. One of them is clever… but I don’t know which one.”

Mark Chewning:

I was told this one several times when I was working on the USSR for 6 weeks. “KGB has the tallest building in every city and town. Even from the basement you can see Siberia!”

David Coleman:

Why do the KGB work in three’s?

One to do the reading, one to do the writing, and one to keep an eye on the intellectuals.

*

An old Jewish man is sitting in the Moscow public library reading a book, when he’s approached by a KGB agent.

“What are you reading, old man?” the agent asks.

“I’m reading a book that will teach me the Hebrew language.”, he replied.

The KGB man laughed an said, “Old man, there is no way you’ll ever be in Israel to speak Hebrew. You’re old, and it will take years and years for you to get the papers to leave.”

“Oh no”, replied the old man, “ I don’t plan to go to Israel, I’m learning Hebrew so that I can speak with Avraham, Yitzhak, Ya’aqov, and Moshe when I get to Heaven.”

The agent thought for a moment and said, “How do you know you’re going to Heaven? What if you go the other way?”

The old man shot back, “That’s OK, I already speak Russian.”

WHY THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY GOT SMALLER AFTER THE FALL OF THE SOVIET UNION (Dima Vorobiev)

~ Two factors mainly decided the great contraction of our economy due to the collapse of Communist rule.

1. We lost our dependencies—the 14 ethnic “union republics” around Russia. They stood for about 2/5 of the combined Soviet GDP.

2. Collapse of the military-industrial complex. The Soviet project was essentially a military machine with a mobilization-type economy attached to it. When the USSR went bankrupt, tens of thousands of enterprises lost their sole, or main, customer: the Soviet Army.

The size of Russian military-related production was extremely hard to pin down. Two main reasons for it were (1) the token nature of Soviet ruble and (2) the mobilization setup of our economy, where most of the civilian production capacities and infrastructure had an inbuilt military-use component.

When the State strangled the military spending, this had a cascading effect.

A large part of existing production capacities went idle. The drop in the GDP in the early 1990s suggests that the real share of the industries involved fully or partially in defense-related production in Soviet economic output was somewhere between 30–50%.

In the absence of the government’s readjustment programs, stalled industrial activity led to millions of people going unpaid for months and years in a row. This led to a collapse in the consumer sector, that, according to the official data, constituted about 60% of the Soviet GDP.

The management and personnel went about stealing inventory. A lot of stuff was sold for pennies, and the proceeds were funneled out of the country. St. Petersburg, under the leadership of Putin’s liberal boss Sobchak, was one of the main hubs for shipping out our national wealth. This was an epic nationwide disinvestment, not captured by the official stats.

Many engineers and other key personnel left the country, taking with them their expertise. This was a huge loss of human capital, hard to quantify, which further People who lost their jobs or went unpaid in their “official” jobs went into the “grey” and black” sectors of the economy. The “Second Economy” exploded, eating away at the stats of the official economy. (A part of the GDP growth under Putin in the early 2000s was simply “black” and “grey” economic activity turning “white.”)

The Soviet poster below says: “Heavy industry is the foundation of our Motherland’s might!” Heavy industry was the Communist term for enterprises that assured our self-reliance in arms production and military infrastructure. It all was too rigid to be swiftly re-oriented to civilian production. Before it had time to do so, most was already stolen by former Party and Communist functionaries, chopped up and sold piecemeal. ~ Dima Vorobiev, Quora

Soviet steel worker

Martin Jacob Kristoffersen:

Dima is commiting blatant heresy against the official Russian version — that Russia was «forced» to this selloff by the scheming West — that was the price Russia had to pay to be a member of WTO and get aid from World Bank.

Dima:

President Putin greatly benefited from what happened in the 1990s, and the Russian patriots you refer to didn’t.

Who would they blame for their misfortune? Certainly not our President.

Myron Krajnyk:

Your whole system“ was based on a “house of cards”. Your Marxist system of 5-year plans as well as your farcical economic system was exposed, once and for all, in the early 1990s disintegration of your “Soviet socialist” experiment. Unable to maintain the subjugation of the many servile “states”, the Moscovite state was exposed for its deep-rooted, depraved, and flawed system of corruption. It’s really that simple. If the reconfigured federation showed any inclination of attempting to reform itself into a credible free market system with an independent judicial system as well as an atmosphere of democratic institutions, the outcome would have been different. Western companies do not invest in unstable, unreliable business opportunities.

Fred Smith:

My experience of being in Russia is that Putin’s regime is a Potemkin regime. When he dies there will be a surge of liberalism. Not quite like western liberalism but maybe more like the conservative liberalism we see in Eastern Europe today.

*

AMERICA’S WEALTHIEST 10% GENERATE 40% OF THE NATION’S PLANET-HEATING POLLUTION

~ America’s wealthiest people are also some of the world’s biggest polluters – not only because of their massive homes and private jets, but because of the fossil fuels generated by the companies they invest their money in.

Coal-fired power plant in West Virginia

A new study published Thursday in the journal PLOS Climate found the wealthiest 10% of Americans are responsible for almost half of planet-heating pollution in the US, and called on governments to shift away from “regressive” taxes on the carbon-intensity of what people buy and focus on taxing climate-polluting investments instead.

“Global warming can be this huge, overwhelming, nebulous thing happening in the world and you feel like you’ve got no agency over it. You kind of know that you’re contributing to it in some way, but it’s really not clear or quantifiable,” said Jared Starr, a sustainability scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a report author.

This study helps build a clearer picture of individual responsibility by going beyond what people consume, he told CNN.

A private jet at Santa Fe Municipal Airport, New Mexico

To do this, the researchers analyzed huge datasets spanning 30 years to connect financial transactions to carbon pollution.

They looked at the planet-heating pollution produced by companies’ direct operations, as well as those relating to companies’ climate impacts further down the supply chain – for example, the bulk of an oil company’s emissions comes when its customers burn the oil it extracts.

That gave a carbon footprint for each dollar of economic activity in the US, which the researchers linked to households using population survey data that showed the industries people work for and their income from wages and investments.

They found the wealthiest 10% in the US, households making more than about $178,000, were responsible for 40% of the nation’s human-caused, planet-heating pollution. The income of the top 1% alone – households making more than $550,000 – was linked to 15% to 17% of this pollution.

The report also identified “super-emitters.” They are almost exclusively among the wealthiest top 0.1% of Americans, concentrated in industries such as finance, insurance and mining, and produce around 3,000 tons of carbon pollution a year. To put that in perspective, it’s estimated people should limit their carbon footprint to around 2.3 tons a year to tackle climate change.

“Fifteen days of income for a top 0.1% household generates as much carbon pollution as a lifetime of income for a household in the bottom 10%,” Starr said.

Climate impact is not just about the size of the people’s income but the industries that generate it. A household making $980,000 from certain fossil fuel industries, for example, would be considered a super-emitter, according to the report. But a household making money from the hospital industry would need to bring in $11 million to produce the same amount of planet-heating pollution.

The report’s authors call on policymakers to rethink how they use taxes to tackle the climate crisis.

Carbon taxes that focus on what people buy – the food we eat, the cars we drive, the clothes we buy – “disproportionately punish the poor while having little impact on the extremely wealthy,” said Starr. They also miss the chunk of wealth rich people spend on investments rather than buying things.

Governments instead should focus on taxes that target shareholders and carbon-intensive investments, the report said. Although it will be “a hard political ask,” Starr acknowledged, especially as the wealthiest tend to have disproportionate political power.

Many ideas for taxing carbon have been floated around the world including windfall taxes on fossil fuel companies and wealth taxes, but few have been politically viable.

Kimberly Nicholas, associate professor of sustainability science at Lund University in Sweden, who was not involved in the report, said the study helps reveal how closely income, especially from investments, is tied to planet-heating pollution.

Sometimes when people talk about ways to tackle the climate crisis, they bring up population control, said Mark Paul, a political economist at Rutgers University who was also not involved in the study. But studies like this “shine light on the outsized responsibility that the rich have in generating and perpetuating the climate crisis,” he told CNN.

Identifying the main actors behind the climate crisis is vital for governments to develop policies that cut planet-heating pollution in a fair way, he added. Although he disagreed with the study’s assertion that carbon taxes on consumption disproportionately affect the poor, saying there were ways to implement them fairly.

The outsized climate impact of the rich is, of course, far from just a US problem.

Globally, the planet-heating pollution produced by billionaires is a million times higher than the average person outside the world’s wealthiest 10%, according to a report last year from the nonprofit Oxfam.

“At the moment, the way the economy works is that it takes money and turns it into climate pollution that is destabilizing life on Earth,” Nicholas said. “And that fundamentally has to change.” ~

Spanish activists vandalize the yacht of a Walmart heiress

https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/17/business/rich-americans-climate-footprint-emissions/index.html

*

OPPENHEIMER: HIS NUCLEAR WEAPONS KEEP SAVING LIVES

(Excerpted from Ben Shapiro, daily@mailer.dailywire.com)

~ Everyone was worried about Oppenheimer’s communist ties. But they had no choice because most of the best nuclear scientists had sympathy with communists. Albert Einstein himself said of Vladimir Lenin, “I honor Lenin as a man who completely sacrificed himself and devoted all his energy to the realization of social justice. I do not consider his methods practical, but one thing is certain: men of his type are the guardians and restorers of humanity.”

One reason for the sympathy for communists was because most of Europe at this point was divided between fascists and communists. A lot of people who opposed the Nazis fell into the communist camp because the communists very often would promise equality of man and brotherhood. For a lot of Jewish expatriates who had been victimized by Nazis on the basis of race, they looked at communism, which suggested equality, and were sympathetic. So Oppenheimer was brought to Los Alamos; despite serious suspicions about his security, he was given security clearance. After the war, he became an ardent opponent of the development of the hydrogen bomb, saying it would lead to an arms race and perhaps the United States should share technology with the Russians. Then everyone would put down their weapons.

There are two ways to read that. Oppenheimer’s fans would suggest he was so stunned by the power of the bomb that he turned against the use of nuclear weapons. The other perspective is that he was perfectly fine using the bomb on Japan when the Soviets wanted the bomb to be used on Japan. But then as soon as the war was over, he didn’t want the United States leaping far ahead of the Russians in terms of nuclear technology, so he wanted to stop the development of the hydrogen bomb.

These suspicions led Lewis Strauss to organize a removal of Oppenheimer’s security clearance. In the movie, this is played as a McCarthyite scare, as if everyone was overwrought. But there is good evidence suggesting that Oppenheimer probably should not have had security clearance in the aftermath of the war because he had been given it simply as an emergency measure. Every woman he ever slept with was a communist. All of his friends were communists. He gave money to communist causes.

The entire premise of the movie is that Oppenheimer has created the means for the world to destroy itself, and he can’t deal with it. All of the counterarguments to him — mutually assured destruction, we have to bomb Japan because a million men will die on the beaches of Japan if we don’t, we have to beat the Soviets — are treated as bad concerns. History proves all of Oppenheimer’s critics basically correct. The reality is that nuclear power has been one of the greatest achievements in the history of science, maybe the greatest achievement in the history of science.

Why? Not only because of the development of nuclear energy, which is essentially endless and clean, but also because the development of the nuclear bomb itself has made wartime death extraordinarily less of a mathematical issue. The number of American soldiers who were killed in World War II was 405,000. 116,000 Americans died in World War I. Then the nuclear bomb was developed. The number of wartime deaths on planet Earth went down dramatically in the aftermath of the development of the bomb. Because if you’re going to fight a proxy war, it better not escalate into anything that approaches a nuclear exchange. ~ Ben Shapiro

*

*

INVENTING HEAVEN

~ The Description of Heaven (1623), by the astronomer Conrad Aslachus, feels close to many ideas about the afterlife still common in Christianity today: heaven is ‘a stately citie, where we shall be secure from all hurt,’ he wrote. There the virtuous dead will see God face to face: ‘we shall behold the bright companies of Angels; there shall wee view the radiant assemblies of sacred Patriarkes, Prophets, and Apostles; there shall wee observe the infinite number of Crownes, of joyfull and tryumphant Martyrs, and Saints.’ Heaven, for Aslachus, was a place of ‘wisdome without ignorance, memory without oblivion, understanding without errour, and reason resplendent without darknesse.’ Aslachus argued against anyone insisting that heaven was ‘in no place, but everywhere diffused’. Instead, his heaven was a distinct place in the universe, a specific locale – crucial for an astronomer working at a time when radical new ideas about the universe were challenging traditional beliefs.

The Christian concept of heaven, so familiar today from popular depictions of clouds and haloed angels, was an invention – one that came about as early Christians interpreted their religious writings in the context of the Greek culture in which their movement grew up. Christian writers combined Plato’s ideas about the soul’s ascent to the sky at death with Aristotle’s understanding of the structure of the universe, a combination that allowed them to apply a cosmological framework to terms like ‘heaven of heavens’, as well as the ascents, described in the New Testament, of both Jesus and Paul.

If I asked my astronomy students where heaven was located, I would no doubt receive a classroom full of bewildered stares, despite the fact that I teach at a Christian university – where the majority of students believe in both heaven and the afterlife. When pressed, they might offer thoughts about heaven being a different plane of reality or perhaps another dimension. They believe, but they don’t conceptualize heaven as a location; it is not a part of their spatial understanding of the universe. For most of the history of Christianity, though, the opposite was true.

The first ideas of heaven that show up in the Bible are consistent with eastern Mediterranean culture: humans dwelled in the middle level of a flat, three-storied universe. The underworld below is the place of the dead, and the heavens above are the place of God or the gods. Even with its unique emphasis on monotheism, the Old Testament maintained hints of a heavenly pantheon in descriptions of the ‘host of heavens’ and language about God keeping council among the gods or stars.

Humans ventured into these heavenly realms only rarely. Enoch, an ancestor of Noah described in the book of Genesis (written around 1000 BCE), was said to have been ‘taken’ by God, often interpreted as meaning he went directly to heaven; and the prophet Elijah, in the Old Testament book of Kings, was described as ascending to heaven in a fiery chariot in approximately the 9th century BCE. But both of these were notable as exceptions. The heavens were not the destination of those who lived a virtuous life. Good or evil, the dead dwelt in Sheol, the underworld.

The idea of ascent to heaven after death was more common among Greek philosophers, such as Plato. In Platonic thought, human souls originally came from the stars and re-ascended to them after death. The visible heavens, with their ceaseless, regular and uniform motions, were separate from the regions of physical change and decay below on Earth. For Plato, the heavens and their motions provided the model for the ideal, orderly motion of rational thought. Studying astronomy was a way for the human soul to reorient itself to the pure rationality of the heavens and prepare for return there after death.

Aristotle, a student of Plato, helped formalize Plato’s division between Earth and the heavens. The universe that Aristotle outlined in his writings was Earth-centered, with the four terrestrial elements – earth, water, fire and air – filling the regions below the Moon. The heavens were composed of a fifth element, the ether. This division of substance explained why the terrestrial regions were imperfect and subject to decay, whereas the heavens were eternal and unchanging. Within the heavens, seven wandering objects (the five visible planets, plus the Sun and the Moon) each had their own motion, but the stars moved together as though embedded on a sphere. This sphere of the fixed stars became the outermost boundary of the Earth-centered universe and was essential to eventual beliefs of the location of the Christian heaven.

For Aristotle, the region beyond the fixed stars was only a non-physical potentiality, defined by ‘neither place nor void nor time’. This may be why philosophers continued to place the realm of the dead within, not beyond, the starry heaven. Cicero, the Roman philosopher and politician, for instance, articulated a Platonic heaven in his On the Republic, in which the character Scipio dreams of the afterlife:

How long will your thoughts be fixed upon the lowly earth? Do you not see what lofty regions you have entered? These are the nine circles, or rather spheres, by which the whole is joined? The outermost sphere is that of heaven; it contains all the rest, and is itself the supreme God, holding and embracing within itself all the other spheres … Below the Moon there is nothing except what is mortal and doomed to decay, save only the souls given to the human race by the bounty of the gods.

Early Christians, trying to make sense of accounts of the life of Jesus of Nazareth and the writings of his first followers in the 1st century, formulated their views of the afterlife in this Greek and Roman philosophical context. Plato provided the idea of souls ascending into heaven, but the texts that would become the Christian scriptures (the New Testament) emphasized a physical, bodily resurrection – most importantly in their claim that Christianity’s founder was himself resurrected in the body and ascended physically to heaven. If Jesus dwelled in heaven, with New Testament texts indicating his followers would join him there, the radical hope of Christianity needed not a Platonic realm of rational thought, but a physical place – a material heaven. Aristotle’s view of the universe, with its outermost sphere of the stars, gave Christians the conceptual framework to locate heaven on a map.

Yet the creation account in Genesis introduces confusion because it speaks of the heavens in two different ways. First, it describes God creating the heavens and Earth. But then it goes on to describe God creating a ‘firmament’ by dividing waters below from waters above.

Reconciling the discrepancy was Basil of Caesarea, the 4th-century Cappadocian writer and bishop. The first of these heavens was the starry heaven and the dwelling of the virtuous dead, Basil explained, whereas the second was only the airy heaven, or sky.

Basil’s arguments pushed heaven from the clouds to the stars, but the final step in the invention of heaven went even further, placing the Christian heaven in a location beyond the stars. Again, precedent came not from scripture or theology but from non-Christian writers – in this case, Martianus Capella, the 5th-century Roman author. In his work On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury, Capella described an ‘Empyrean realm of pure understanding’ beyond the stars. From the 7th century, Christian writers such as Isidore of Seville and Bede took up this idea and, by the 12th century, the identification of the Christian heaven with the empyrean (from the Greek word for ‘fire’) was cemented. The Glossa ordinaria, a medieval collection of commentaries on the Bible, identified this third heaven, the empyrean heaven, with the realm first created by God in the Genesis account: ‘In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.’

The introduction of the empyrean into Christian cosmology was the final articulation of heaven as a specific location in the Aristotelean universe. The division of the cosmos into terrestrial regions (subject to change, death and decay) and celestial regions (perfect and eternal) already aligned well with theological ideas of a fallen world below and a perfect God above. It supported a three-fold view of the heavens – airy, starry and empyrean – that seemed to have a Biblical basis as well. An empyrean heaven beyond the heaven of air and the heaven of stars was obviously the ‘heaven of heavens’ of the Old Testament. It also fit New Testament passages referring to heaven. For instance, after resurrection, Christ was said to ascend to a place ‘above all the heavens’; the apostle Paul wrote of being caught up into the ‘third heaven’.

In this Christian cosmology, the first heaven was the heaven of the air, which extended from Earth’s surface to where the Moon separated the terrestrial and celestial realms. Above the airy heaven was the second heaven – the starry or celestial heaven – which extended from the Moon to the sphere of the stars, the boundary of the visible universe. Beyond this was the empyrean heaven, which was identified as the dwelling of God, the saints and the angels.

Indeed, by the 1240s, ecclesiastical authorities in Paris specified that it was theologically erroneous to locate the Blessed Virgin Mary or the saints in any heaven except the empyrean. Others said that to deny the existence of the empyrean was to deny the foundations of Christianity. By the 13th century, the major theologians of medieval Europe, including Albertus Magnus, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus, embraced the concept.

The fact that the empyrean heaven was unobservable was not an issue because its existence had become a matter of faith. Campanus of Novara, the 13th-century astronomer and a contemporary of Aquinas, admitted that we could not know by rational argument whether there was anything beyond the sphere of the stars, but that ‘we are informed by faith, and in agreement with the holy teachers of the Church we reverently confess that, beyond it, is the empyrean heaven in which is the dwelling place of good spirits.’ Aquinas admitted the same: the empyrean could not be argued by sight or motion, like the celestial heavens, but rather was ‘held by authority’.

The empyrean heaven as the dwelling place of God and the saints became a significant facet of the Christian world. It was a common theme in art, and Dante Alighieri glimpsed it at the climax of his Divine Comedy (c1308-21) after he was led up from the center of the cosmos through the lower heavens. Theologians speculated about how bodies could inhabit the empyrean, whether it extended infinitely, and whether it was created by God, or pre-existed God and provided the location of God’s creative acts. If you had asked a Christian from the Middle Ages before the time of Galileo where the heaven mentioned twice in the Lord’s prayer was, they would have pointed upward, toward the unseen empyrean heaven beyond the sky.

Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the Empyrean; Gustave Doré. At the very end of Dante's Paradiso, Dante visits God in the Empyrean.

For these observers, looking into the night sky was not looking into an infinite abyss; it was looking upward at an edifice of vast but limited extent, beyond which was the promised dwelling place of the Christian dead. As C S Lewis puts it:

[T]o look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest – trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building. The ‘space’ of modern astronomy may arouse terror, or bewilderment or vague reverie; [but] the spheres of the old [astronomy] present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony.

Understanding how theology mapped onto location in this Earth-centered cosmos gives a sense of why the transition to a Sun-centered one was so disruptive. With the acceptance of Copernicus’s new view of the universe, Earth was dethroned from a position of ‘privilege’ at the center of the universe but, more than that, heaven itself was dislocated – or rather, was shown to have no location at all. Telescopic observations from the time of Galileo indicated that the stars were scattered in a limitless space, not placed on a sphere surrounding the Earth. The celestial heavens were not enclosed, and there was no boundary to the universe beyond which the empyrean could be placed.

From the 16th century, many astronomers who accepted Copernicus’s new view of the universe nonetheless espoused the idea of a Christian heaven. Johannes Kepler believed the stars were arranged spherically around the Sun, leaving room for the empyrean beyond. Philip Lansbergen argued that the stars were God’s armies in the ‘forecourt’ of heaven and that the empyrean was still the third, unseen heaven. Thomas Digges, one of the first proponents of the Copernican system in England, made the infinite starry realm itself the ‘very court of celestial angelles … and … the habitacle for the elect’.

Giordano Bruno, on the other hand, was famously executed by the Catholic Church for envisioning an infinite not beyond the stars but within them.

Otto von Guericke (1602-1686), a German inventor and natural philosopher, summarized changing ideas about the cosmos in 1672, noting:

There are so many and such different opinions that there is no sound way of reconciling them. Some would have it that the stars are bounded by the outermost heaven … some say that they are bounded by the Supercelestial Waters; some say that they are bounded by the Empyrean Heaven; some by a plurality of Worlds, some by Imaginary Space; some by Nothing and some by a Void.

By the 17th century, in the wake of revelations of the telescope, consensus over the location of heaven was gone. The new astronomy of Copernicus and Galileo ultimately fractured ideas about the empyrean heaven and gave rise to widely different assumptions regarding its location or even its existence.

Eventually, as a more detailed understanding of the starry realms developed, the empyrean heaven was displaced completely. By the end of the 18th century, a Catholic dictionary of theology could dismiss speculations about the physical location of heaven: ‘It should be the object of our desires and of our hopes and not of our speculations.’ The airy heaven became the atmosphere – a term first coined by 16th- and 17th-century astronomers; the celestial heaven became space, and the empyrean heaven – the ‘heaven of heavens’ and the dwelling place of God – disappeared from the universe.

In The Celestial Worlds Discover’d (1698), the astronomer Christiaan Huygens wrote about the inhabitants of the planets, speculating about their appearance, nature and sciences. The universe, Huygens was certain ‘is infinitely extended’ but filled with inhabited planets:

What a wonderful and amazing Scheme have we here of the magnificent Vastness of the Universe! So many Suns, so many Earths, and every one of them stock’d with so many Herbs, Trees, and Animals, and adorn’d with so many Seas and Mountains!

Heaven had disappeared from the universe, replaced by something much closer to a science-fiction vision of outer space.

Viewed from one perspective, the dislocation of the empyrean heaven from the physical universe is simply an example of the progress of science dismantling religious belief. But belief is seldom static, and the relationship between science and faith is one of dialogue as often as of conflict.

Ideas about the Christian heaven were constructed in dialogue with contemporary knowledge of the world – at the time, Aristotelian ideas about the physical universe. When this view of nature was shown to be incorrect, ideas of heaven were modified accordingly. Astronomy forced Christian thinkers to admit that the empyrean heaven was never a central tenet of their faith to begin with and return to what contemporary theologians such as N T Wright consider a view closer to original Christianity: salvation not as an escape to a heaven beyond the universe but a stranger, more radical hope of renewal and re-creation of this one. An empyrean heaven was no more essential to Christianity, it turned out, than a motionless Earth – despite scriptures that seemed to argue for both. ~

https://aeon.co/essays/how-heaven-became-a-place-among-the-stars?utm_source=Aeon+Newsletter&utm_campaign=6d1820c68e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2023_09_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-b43a9ed933-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D

Lilith:

My mom talked about being ready to “go live in heaven,” as though it was a specific location where people actually “lived,” perhaps that meant sleeping, eating, going to the bathroom, etc. She was concerned about how she would find my dad because there would be so many people. Her visions of heaven were often going through crowds and crowds of people looking for him.

Oriana:

This is so wonderfully romantic! Love in the afterlife.

The closest two things my mother said on the subject:

(Trying to lessen my childhood anxiety about going to hell): There is no hell. God wouldn’t be so cruel.

(Close to the time of her death) They say God accepts everyone.

During one of our two visits to Poland, she heard the phrase “brain-free consciousness,” and burst out in wild laughter. It just happened; she couldn’t control it.

What she also couldn’t control was reaching out with her right arm, a gesture so familiar to me from hiking trips — waiting for my father to pull her across a narrow mountain stream. A simple gesture of love and kindness. I guess we never cease wanting that, even a minor token of being loved, or at least valued.

Even Pope John 2 officially (i.e. infallibly) announced that heaven and hell are not places, but states of mind. In addition, heaven is also “the person of God.” This is a needless piling on of “mysteries” (ahem) . . . I think I could accept the “state of mind” definition, but states of mind tend to be transient.

Eating, sleeping, and going to the bathroom . . . in heaven? No one has suggested that before! (I mean especially going to the bathroom.) (In Islamic heaven there is feasting, so it would be plausible . . . I know I better stop right there.)

*

Oriana: PS: Milosz on heaven as a place.

An interesting discussion of the loss of heaven as an actual place can be found in the last volume of poems by Czeslaw Milosz:

SECOND SPACE

How spacious the heavenly halls!

Approach them on aerial stairs.

Above white clouds, the hanging gardens of paradise.

A soul tears itself from the body and soars.

It remembers that there is an up.

And there is a down.

Have we really lost faith in that other space?

Have they vanished forever, both Heaven and Hell?

Without unearthly meadows how to meet salvation?

And where will the damned find suitable quarters?

Let us weep, lament the enormity of the loss.

Let us smear our faces with coal, loosen our hair.

Let us implore that it be returned to us,

That second space.

~ Czeslaw Milosz, translated by the author and Robert Hass

In an earlier volume, Milosz observed,

“There is only one theme: an era is coming to an end which lasted nearly two to thousand years, when religion had primacy of place in relation to philosophy, science and art; no doubt this simply meant that people believed in Heaven and Hell. These disappeared from imagination and no poet or painter would be able populate them again, though the models of Hell exist here on earth.” ~ Unattainable Earth, 1986, p. 78.

For an extended discussion, please go to http://oriana-poetry.blogspot.com/2011/03/miloszs-second-space.html

Mary:

The problem with heaven is that it is bodiless. All of our experience is rooted in and filtered through the body —including the shape and scope of imagination. Without a body there is nothing even to imagine. I think that is why the idea of heaven is so bland and sketchy, not really appealing —in fact more boring than anything. The idea of choirs of disembodied spirits endlessly singing praise sounds like a long snooze. The part that does have appeal is the idea of reuniting with those we loved...that is a solid human longing, and the promise of reunion is compelling.

Hell, however, is something we know well, something experienced here on earth in many forms, again and again, both in personal and collective history. Suffering is familiar, something we have a knack for, something we recognize and understand. It is not hard to imagine.

Both places, or states, we know in and through the body, not in some ghostly immaterial otherworld. They are real only as we create them in this world, with our living bodies. Hell comes easy. Heaven is a never ending struggle, but one not easily abandoned. Many have imagined and worked toward a better human world, have seen the potential to realize that heaven on earth: the only one possible, the only one worth fighting for. This is a dream with actual potential, that can only be realized...created...in the here and now, by physical bodies in the physical world. There is no time to waste waiting for the afterlife.

Oriana:

Ah, but according to most Christian denominations, eventually, when the graves open and we step out for the Last Judgment, we will have bodies again. The body is all kinds of trouble, but "resurrection in the body" is part of the dogma. Some insist that those will be perfect bodies, without any defects or disease.

And once we have bodies again, it seems logical that there'd be the pleasures of eating and love-making. But only Islam was daring enough to describe paradise in terms of bodily pleasure — don't forget the seventy-two virgins. I'd also hope for seventy-two experienced male lovers.

*

*

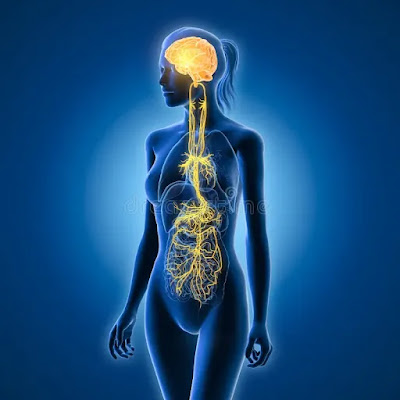

WHY THE VAGUS NERVE IS SO IMPORTANT

Serving as a two-way ‘electrical superhighway’, the vagus nerve – which is actually a pair of nerves – allows for communication between the brain and the heart, lungs and abdominal organs. And because of this, it has been shown to help control things such as the heart rate, breathing, digestion and even immune responses. Now, scientists are asking whether stimulating the vagus nerve could transform physical and mental health.

~ I’ve made a cup of coffee, written my to-do list and now I’m wiring up my ear to a device that will send an electrical message to my brainstem. If the testimonials are to believed, incorporating this stimulating habit into my daily routine could help to reduce stress and anxiety, curb inflammation and digestive issues, and perhaps improve my sleep and concentration by tapping into the “electrical superhighway” that is the vagus nerve.

From plunging your face into icy water, to piercing the small flap of cartilage in front of your ear, the internet is awash with tips for hacking this system that carries signals between the brain and chest and abdominal organs.

Manufacturers and retailers are also increasingly cashing in on this trend, with Amazon alone offering hundreds of vagus nerve products, ranging from books and vibrating pendants to electrical stimulators similar to the one I’ve been testing.

Meanwhile, scientific interest in vagus nerve stimulation is exploding, with studies investigating it as a potential treatment for everything from obesity to depression, arthritis and Covid-related fatigue. So, what exactly is the vagus nerve, and is all this hype warranted?

The vagus nerve is, in fact, a pair of nerves that serve as a two-way communication channel between the brain and the heart, lungs and abdominal organs, plus structures such as the esophagus and voice box, helping to control involuntary processes, including breathing, heart rate, digestion and immune responses. They are also an important part of the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs the “rest and digest” processes, and relaxes the body after periods of stress or danger that activate our sympathetic “fight or flight” responses.

In the late 19th century, scientists observed that compressing the main artery in the neck – alongside which the vagus nerves run – could help to prevent or treat epilepsy. This idea was resurrected in the 1980s, when the first electrical stimulators were implanted into the necks of epilepsy patients, helping to calm down the irregular electrical brain activity that triggers seizures.

As more people were fitted with these devices, doctors began to spot an interesting pattern. “They noticed that even if the device didn’t help their epilepsy, some of these patients started to have a better outlook on life,” says Kevin Tracey, a professor of molecular medicine and neurosurgery at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York.

Today, vagus nerve stimulators are increasingly being investigated as an alternative to antidepressants in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Surgically implanted stimulators are also an approved treatment for epilepsy – although they only seem to work in a subset of patients.

Using electrical stimulation to treat brain disorders such as epilepsy and depression makes intuitive sense – nerves and brain cells communicate using electricity, after all.

However, in the late 1990s, Tracey and his colleagues made a surprising discovery. They were testing an experimental drug that they expected to dampen inflammation in rats’ brains, but when they injected it, it dampened inflammation throughout the body.

This was puzzling, because the brain is physically separated from the rest of the body by the blood-brain barrier – a tightly packed layer of cells that regulates the passage of large and small molecules into the brain, to help keep it safe. Tracey and his colleagues tried severing the vagus nerve and repeated the experiment. This time, the drug’s anti-inflammatory effects were confined to the brain.

It was an extraordinary discovery: conventional wisdom held that there was no connection between the nervous and immune systems – but the vagus nerve appeared to provide that link. Further research revealed that the brain communicates with the spleen – an organ that plays a critical role in the immune system – by sending electrical signals down the vagus nerve. These trigger the release of a chemical called acetylcholine that tells immune cells to switch off inflammation. Electrically stimulating the vagus nerve with an implanted device achieved the same feat.

Tracey immediately recognized the therapeutic implications, having spent years trying to develop better treatments for inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, arthritis and Crohn’s disease. Existing drugs dampen inflammation, but carry a risk of serious side effects. Here was a technique with the potential to switch off inflammation without the need for drugs.

Tracey’s discovery also caught the attention of mind-body practitioners, including the Dutch motivational speaker and “Iceman” Wim Hof, who claimed that he could control inflammation in his body through a combination of breath work, meditation and cold water immersion. “He wanted me to study him,” Tracey says.