*

Only sound, Tomas, slips,

ghost-like, from the body.

Speech is an orphan sound.

Push the lampshade aside,

and by staring straight ahead

you’ll see air face to face:

swarms of those who have stained it

with their lips before us.

~ Josip Brodsky, “Lithuanian Nocturne”

Only sound slips like a ghost from the body, as the soul is supposed to do at the moment of death. “Speech is an orphan sound” — the parent body already left behind. Brodsky doesn’t believe in any other ghosts — only sound — mainly words, but not exclusively. He does believe in a larger community beyond the individual, and our connection with it — call it the “collective psyche.”

As for the tradition meaning of “soul,” I’ve said it several times by now: the ancient Hebrews did not believe in the soul apart from the body — and the word for soul was ruah, “breath.” The breath of life. Life started with the first breath, and ended with the last breath. You were either dead or alive, meaning breathing. That’s why the dead awakened by the angel’s trumpet had to put on bodies in order to be judged at the Last Judgment.

But something does leave the body and “travel” — the sounds we make. Brodsky didn’t want to say “words.” That would be too narrow. He wanted to include laughter and sobbing — hence “sound”:

Only sound, Tomas, slips,

ghost-like, from the body.

Speech is an orphan sound.

Later the word “stained” reminds me of Beckett’s “Every word is a stain on silence.” But that’s not Brodsky’s attitude. He’s more like Rilke, who saw the multitudes of those who loved before us — the geological layers of all the immense loving that preceded us— ancient fathers like ruined mountains, the dried riverbeds of foremothers. There is “tenderness toward existence” in both Rilke and Brodsky.

I am also reminded of the poem by Akhmatova where she imagines a huge column of grieving people walking in the snow behind her and Marina Tzvetayeva. There is a feeling of community with others — with oppressed, grieving multitudes, who follow the poets like a funeral procession.

Aside from that solidarity with others, Brodsky also shows the reality of the mental realm. Millions have lost the notion of a detachable, brain-free soul that keeps on roaming, consciousness intact, "unencumbered" by the body. But what happens after death is gradually becoming less important than our notions of life while it lasts. And the life of the mind, understood as a process, certainly has a strong reality. In fact it's in recent decades that we understood how much of our memory is fictional, and that, conversely, fictional characters may have influenced us more than actual people. Brodsky could be called a "literary atheist" — something I call myself at times.

Known for always cracking jokes, Brodsky had a very stressful life, especially before being expelled from the Soviet Union (that expulsion must have caused a severe heartbreak, considering how much Brodsky loved Russia). He knew a lot about suffering — and about not giving in to despair. I recommend his essays — marvelous writing, and his best work, most readers agree. Too bad he died so young (at 55), of heart disease. He’s buried in Venice, the city he loved, in part because it reminded him of Leningrad (now St. Petersburg again). “Watermark” is a magical collection of his essays about Venice, but the ghost of a different city flits through it here and there — the ghost captured in words, consisting of words. ~ Oriana

*

ON BRODSKY AND HIS CONTRADICTIONS

~ It is hard to guess what brought Brodsky to Morton Street — chance or somebody’s advice. While looking for a New York apartment he probably considered many things, from price to location — it is in the center of Manhattan, with many coffee shops and restaurants, the Hudson River nearby, and scenery with something vaguely European about it. Or perhaps it is what Europeans want to believe, trying to justify choosing America?

The Russian Samovar restaurant on 52nd street — once owned by Joseph Brodsky, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and a Russian-born former language teacher turned restaurateur, Roman Kaplan — occasionally holds poetry readings in a room on the second floor. The dining area is on the first floor. There is a coat room to the left and a toadish-green bar to the right. What strikes the visitor first is a display of huge bottles with various brands of vodka. Further down stands a white Royal piano played by Sasha Izbitser. On the right side there is a brick wall with photographs of celebrities who have visited the restaurant: from Bella Akhmadulina to Miloš Forman.

On the second floor, a full-body bronze statue of Joseph Brodsky stands on a table under samovars in the left corner of the rectangular room where Russian-speaking New Yorkers gather for readings. The statue is based on a well-known photo of Brodsky. The photographer caught him in the middle of the street, with a briefcase under his arm and a scarf around his neck. The scarf and the poet’s long coat are flapping in the wind. The dynamics of the figure captures the poet’s hastiness, and perhaps also his inner unrest.

In the evenings I like to sit next to the statue, making myself comfortable in a soft leather chair creaking like old wood.

Forbidden Brodsky

For my generation, Brodsky’s name probably resounded first at the beginning of perestroika, when a Moscow-based journalist Henrikh Borovik presented a TV documentary about Jewish emigration to Israel and America. The film was obviously propaganda: one weeping family from Israel begged the Soviet government to give them back their Soviet citizenship, and pledged to walk to their country on foot if necessary.

In America, according to the report, senior citizens watch Soviet movies on VHS, and bohemian youths make fun of Pravda headlines chanting “Prav-da-da-da!”

Borovik commented: Look what scum have left our glorious country. But one of those scumbags said: “Well, who needs Russian literature here in America? Except perhaps Solzhenitsyn or Brodsky. ” That was how, at least for me, Brodsky’s name came up for the first time. Of course I could not know then about his trial, or about his exile to the village of Norenskaya, about the circumstances of his departure for America, about his friendship with Auden, or about his poems and essays.

The complete ban on Brodsky was something to be expected from a system that blacklisted everyone who did not acquiesce to it in every possible way. Such was the case of Joseph Brodsky, an exile forced to leave the Soviet Union and seemingly erased from Russian culture forever.

Later, after his Nobel Prize, Brodsky became an object of veneration in the Soviet Union. His figure was inseparably linked with the Nobel aura. Later still, when the transcripts of his 1964 trial were published, together with his memoirs from his Leningrad days, as well as the details of his complicated relationship with Marina Basmanova, his conversations with Akhmatova, his poetic attitude to Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva, his meetings with Auden, and also some facts about his American life — all this deepened my conviction that beyond the text there existed another inter-textual Brodsky who, like it or not, supplemented Brodsky the poet. I also started to think that the idea that each poet’s biography is fully contained in his poems is only half- or even a quarter-true.

To be fair, Brodsky’s lack of publication in the Soviet Union was partly compensated in the west, where unofficial literature in the East was carefully followed, and where his poems and books started to appear in translation. After all, judging by the standards of Soviet citizenship, what were the prospects for a poet who had served a sentence in exile, had spent some time in a mental institution, had no steady employment, was consorting with foreigners, and moved in suspicious circles of Leningrad bohemia constantly surveilled by the KGB, even though he wasn’t really a dissident?

If we look for a similar case, the first person who comes to mind is Vasyl Stus.[Vasyl Semenovych Stus (1938 – 1985) – a Ukrainian poet, translator, literary critic, journalist.] Why Stus? Because of some telling similarities, as well as differences, between him and his Russian counterpart. Although Stus’s poetry is quite unlike Brodsky’s, they both belonged to the same generation and, because of their moral and poetic principles, they both refused to play any games with authorities.

They both rejected the very idea of compromise, and they both explored the deeper layers of poetic language. That is why, in many poems by Stus and Brodsky alike, the dominant motifs are reflection on culture, abstractions, and existential questions. Their poems show a strong inclination toward philosophical contemplation of reality and moral choices, of choosing the right path, and of the relationship between a poet and authority. Their similarities can also be found in the dialogue both Brodsky and Stus conducted with Rilke — an emblematic figure for European modernism and for them personally. Stus translated Rilke, and Brodsky wrote the essay “Ninety Years Later,” a comprehensive analysis of Rilke’s poem “Orpheus, Eurydice, Hermes.”

And what separated them? Well, to begin with, their childhoods in Leningrad and Donbas, Brodsky’s intelligentsia background and Stus’s peasant origins, as well as Brodsky’s Jewish and Stus’s Ukrainian roots that place them differently within the historical and imperial context. Brodsky sees history through the prism of disrupted Jewish history (“The Jewish Cemetery,” “The Jewish Crow-Bird”), through Old Testament motifs (“Flight into Egypt”), and personified Hellenic and Roman history — a culture of vanished empires and recent historical events (“On the Death of Zhukov,” Afghanistan in “Lines on the Winter Campaign, 1980”).

For Stus, the sense of history is rooted in the memory of defeat (“A Hundred Years Since the Sich Died,” “From the Chronicle of Samovid,” “N.G. Chernyshevsky’s Laments”), which explains his attitude towards the Empire. That is why their poems containing “imperial” motifs (directly or indirectly expressed) place both poets on opposite sides of the barricade.

Jewish Brodsky and Ukrainian Stus see the empire, their own relationship to it, and also the Empire’s future in a radically different way. For Brodsky, the transformation of the Soviet Union into post-Soviet Russia was perfectly natural. In Stus’s case, the issue is more complicated. I am not sure what he thought about the complete emancipation of Ukraine from Russia, but he was convinced that “amicable” relations between Russia and Ukraine should cease at some point until Ukraine liberates itself from this forced love. That is why the Empire, though it rejected Brodsky’s poetic gift, considered him, through the mediation of Russian language and culture, its own delinquent, someone who went astray. On the other hand, the Empire always considered Stus a delinquent outsider who dared to question its hallowed existence. Under those circumstances, just forcing Stus beyond the Empire’s borders was simply out of the question. He had to be destroyed.

I have no doubt that Brodsky was “fortunate.” He was fortunate with his internal exile, because that is how the West has learned about him; he was fortunate with his milieu, which influenced him in good measure (Leningrad, Akhmatova); he was fortunate with America (Auden, Miłosz, Paz, Sontag, Strand, Hecht, and Walcott). Certainly all these “fortunate” elements would amount to nothing were it not for his poetry.

Brodsky the Poet

After reading several of Brodsky’s poems for the first time, I felt as if an electrical current had run through my body. His poetics was unlike anything offered by prominent Russian Shestydesatniky (“The Sixties Generation”) — it did not resemble Akhmadulina’s melos or Voznesensky’s futurism/avant-gardism, or the op-ed style of Yevtushenko. The nature of Brodsky’s poetry, it seemed, was clearly at variance with the well-established and celebrated poetics of his contemporaries.

Entire treatises are written today about the influence of Yevgeny Baratynsky and John Donne on Brodsky. It was established that his versification carries on certain rhythmic and melodic traditions of Russian poetry. For me, the important thing was Brodsky’s sense of an idea in poetry — of his poetry’s metaphysical roots in the tenets of Christianity and Judaism. In fact, Brodsky’s idiolect, his unique literary personality, manifests itself also in his conceptual approach to the composition of his own books. We get the impression that rather than choosing his poems randomly, shuffling them like cards in a deck, he wrote those poems working from a specific concept and from a common general idea.

That is why Brodsky is a poet of unique resonance, timbre, and melos — a poet of the city, of human existence and nature, a poet who personalizes history, and reflects on culture. This, in turn, links him to his contemporaries — to Russians and other Slavic poets such as Miłosz, Herbert, Szymborska, Stus [Vasyl Semenovych Stus (1938 – 1985) – a Ukrainian poet, translator, literary critic, journalist], and even English-language poets, from marginalized domains where history — imperial or colonial — still occupies a prominent place in the collective and individual memory. It links him to them, yet at the same time sets him apart.

Brodsky wrote about the Leningrad landscapes of his life in his famous 1985 essay “In a Room and a Half.” It was composed in English, and the choice of the language was absolutely deliberate. According to Brodsky, only English could protect the text from the erosion of time.

A room-and-a-half was the space assigned by Russian authorities to the war veteran Alexander Brodsky. It was the space in which his son, the future poet, grew up and developed. Brodsky’s essay, however, is dedicated to memory more than space. In it, he grows the muscle of guilt about his parents, who were never allowed to visit their son in America, and the muscle of memory about the objects that surrounded him in those rooms, about the smell of communal apartments, about their residents, about streets and sacral architecture — and tests this muscle’s strength by stretching it like a bow-string over his contemporary condition as a denizen of America.

The city in which Brodsky grew up was an imperial city. It was apparent, first of all, in its architecture whose visual impact, grandeur, and might influenced the residents’ subconscious, many Soviet proletarian neighborhoods notwithstanding. This could not be without an impact on Brodsky’s future inclinations.

For Brodsky, self-expression in poetry was less important than something else. The form of his poetry is rather traditional, although he would loosen and innovate it by using inventive stanza patterns, enjambments, the possibilities of different sound registers present in Russian speech, by mixing up landscapes, sensations, intellectual stimuli. Brodsky wrote at a time when the greatest Slavic poets, most significantly Poles (Miłosz, Herbert, Różewicz, Szymborska) had freed themselves from the encumbrances of rhythm and rhyme and considered history – memory – time the real cornerstones of their poetry. Their personalized history differed from the Russian one, although their nation had endured no lesser cataclysms.

The Empire According to Brodsky

Among the reasons for writing this essay was not only my desire to re-read Brodsky following Irena Grudzińska-Gross and Lev Loseff, who almost simultaneously published books about Brodsky in Polish and Russian, or my wish to contribute something to the body of Brodsky criticism. One of the reasons was a certain problem Grudzińska-Gross and Loseff did not ignore, but did not fully resolve either — the poem “On the Independence of Ukraine.”

I was prompted to write these notes by something very simple: an article titled “Shocked by Brodsky” I found on the Sem40 website. The author, Sonia T., describes what must have been Brodsky’s last public reading in New York in 1996. She shares her impressions about the evening and how, when the poet read “On the Independence of Ukraine,” she walked out in protest during the last lines.

Grudzińska-Gross touches upon this problem in her book, stating that, “[Brodsky’s] Russian patriotism is affirmed by […] the poem “Nation,” as well as another poem that attacks Ukraine from imperial and great-Russian positions.”

“He has read this poem to Tomas Venclova,” she continues, “who informed me in a conversation that he had advised against publishing it.”

In my opinion, Brodsky’s worldview is too complicated and self-contradictory to hastily appoint accents that would be acceptable to all. We are not talking here primarily about his poetic and aesthetic sympathies or antipathies, or about his purely human faults and virtues, but about a position from which he is observing the world and commenting on political as well as daily occurrences. The crux of the problem is how does one separate — in Brodsky or anybody else — one’s aesthetic from social orientation, one’s purely human sympathies from established, generally accepted, politically correct opinions?

It would appear that since Brodsky suffered at the hands of the Empire, which condemned him to exile, prevented him from realizing himself as a poet, and even refused to allow his parents to see their only son — any defeat of that Empire, its destruction and death, should evoke a sense of happiness or at lease of personal victory, not a desire to defend it.

Indeed, Ukraine’s independence did spell the death of the Empire, no matter how hard the Empire tried to prevent it.

From what vantage point does Brodsky try to view Ukraine? From the position of Russian patriotic intelligentsia? From the position of a Western Slavophile? From the position of a cosmopolitan?

And there is another problem, equally difficult to resolve but relatively easy to define. Living in America, where everything is so politically correct, and communicating with his friends who brought with them their complexes of victimhood by communism (Miłosz) or colonialism (Walcott), Brodsky challenges in his poem every possible rule of required public etiquette. He has produced a text which, in the event of its publication, would clearly define his position not only toward Ukraine, but also toward Lithuania and Poland — countries that he truly loved and whose cultural representatives he befriended.

On the one hand, Brodsky — a spokesman for Russian language and literature — was under no obligation to love Ukraine, even though, as his name indicates, his paternal ancestors must have harkened from Brody in Ukraine. Because of this fact, at least, he might have shown some sympathy for Ukraine. But he didn’t. As Brodsky affirms, for obvious reasons his family hardly ever mentioned their life before the Revolution. It is likely that Brodsky never heard family tales about distant ancestors from Volhynia, once within the borders of the Polish Crown, although he was quite familiar with centuries of common Ukrainian-Jewish history.

Zbigniew Herbert had more reasons to write about Ukrainians and Lviv, where he grew up and spent much of World War II. It is even possible to consider Herbert a poet of the borderlands, who could have nursed a painful memory of the Kresy, the once-Polish eastern lands, and the complex of defeat. Czesław Miłosz, another poet of the borderlands, might have had equal grounds to blame Lithuania for its desire to separate itself from the Soviet Union but not to re-join Poland. But in both cases such propositions would sound quite ridiculous.

As a matter of fact, during the 1988 Lisbon Conference, to which Brodsky, Miłosz, Rushdie, Sontag, and Walcott were invited, Brodsky vehemently defended Russia, not just as an empire of culture, but as a political empire. He took some liberties with the definition of Central Europe and its historical and spiritual foundations, which provoked strong objections from his colleagues. Derek Walcott tried to moderate the conflict, but he was not particularly well-versed in European affairs. Therefore the poets from former empires and from borderlands diverged in their assessments of the current situation.

The imperial idea appears quite frequently in Brodsky’s poems, usually in the Greco-Roman context. These classic imperial models evoke in the poet if not awe at least admiration, presumably not on account of constant wars and territorial conquests, but culture — the pride of every empire.

The Soviet empire was dying, a large part of it — Ukraine — was breaking away, and Brodsky’s reaction seemed quite natural. Already in 1985 he entered into a polemic with Milan Kundera. No matter what has been said about this exchange, especially by Russian commentators, one thing was obvious and undeniable: It was a skirmish between two opposite worldviews of Europe and Asia represented by Kundera and Brodsky — between rational European thought and Asiatic emotional turmoil and mystical probing of the fathomless depths of the human soul. For Kundera, the very thought of Russia aroused a sense of threat. Russia signified aggression and belligerence. What is more, Brodsky decided to base his arguments against Kundera on Dostoyevsky, which was probably the most unfortunate way to settle historical and cultural scores. And what if Kundera resolved to respond with Kafka?

One may agree with Irena Grudzińska-Gross that Brodsky was born and raised in one empire (the USSR), lived in a second (America), and found his eternal peace in the third (Rome). This, however, does not negate the fact that, in the simple human sense, Brodsky was able to accept some imperial borderlands, such as Poland and Lithuania, and to dismiss others, such as Ukraine.

Brodsky’s poets

Brodsky frequently expressed his views on poetic subjects and constructed his own canon of poets who were important to him. He contributed in this way to the world-renown of Tsvetayeva and Mandelstam. He carefully watched over the quality of the English translations of Akhmatova, and harshly denounced what he perceived to be faulty interpretations of her poetry.

Of course, at the core of his poetic predilections was the poetry of Pushkin, Baratynsky, Pasternak, Zabolotsky, together with John Donne, Auden, and Frost. He never said a single word about the poets of the New York School, Allen Ginsberg, or Laurence Ferlinghetti — they were obviously not his cup of tea.

For me, the verse in which he contrasts “the lines of Alexander” with “Taras’s gibberish,” are especially intriguing and revealing. Alexander Pushkin and Taras Shevchenko were two prominent poets who also suffered at the hands of the empire: Pushkin was exiled to “the South” while Shevchenko suffered a more severe punishment — military service in the steppes of Orenburg. Brodsky, who was also exiled to the Arkhangelsk district after he served a prison term, must have compared — if he thought about it at all — his feelings about imprisonment and exile with Shevchenko’s. As a poet, even without reading Shevchenko’s cycle “In the Dungeons,” he could intuitively sense that he was repeating the Ukrainian poet’s fate a hundred years later.

Brodsky’s rejection of Shevchenko, however, did not result simply from the clichés about Shevchenko’s revolutionary views, or about him being a commonplace, home-grown talent. There was probably something deeper here. Incidentally, Pushkin was also against the independence of Poland, although he befriended Mickiewicz.

What does “Taras’s gibberish” mean?

Marina Temkina and I made an appointment to meet in the Russian Samovar at one of their poetry readings. It didn’t work out because someone brought a group of students, the room was incredibly packed, and we just nodded to each other from a distance and moved our meeting to another time and place.

From our email exchanges it became clear that Marina knew Brodsky quite well, translated his essays into English, and was familiar with the details of the poet’s life in New York. She invited me to her place, which was in the Chelsea neighborhood in Manhattan. Using this opportunity, I turned onto Twenty Third Street to have a look at the Chelsea Hotel, the façade of which was covered, like a veteran’s chest full of medals, with plaques commemorating writers who had lived and worked there.

Marina set the table and quickly prepared a meal. Cheese, a bottle of French wine, and candlesticks with candles occupied an honorary place on the table even before my arrival. A quiet New York street seemed to be well-protected from the noise of Seventh Avenue.

I learned from Marina about the visit of Brodsky’s son in New York and about the poet’s death at his home in Brooklyn Heights, which he had bought and where he had moved in with his family. Coincidentally or not, the neighborhood was once the home of Walt Whitman, Tom Wolfe, W. H. Auden, Arthur Miller, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer.

When I asked Marina what she thought about the poem “On the Independence of Ukraine,” she responded with her characteristic radiant sadness that his anti-Ukrainian feelings could be explained by Jewish post-Holocaust trauma. The poet seemed to have forgiven Poland and Lithuania, but not Ukraine.

I then remembered an episode from the conversation between Russian journalist Solomon Volkov and Brodsky about Italy. Brodsky mentioned Ezra Pound in reference to his visit to Pound’s longtime lover Olga Rudge. Brodsky attended some festival with Susan Sontag, who by pure chance had met Pound’s aged companion in the street and asked Brodsky to accompany her on a visit to her place. As Brodsky recollects, throughout the evening Rudge tried to correct what she considered misunderstandings about Pound’s fascism and anti-Semitism. At some point, Sontag made a reasonable comment that she absolutely could not accept those explanations because they make Pound look like another Tokyo Rose, an opportunistic collaborator who conducted propaganda broadcasts from Tokyo meant to demoralize American soldiers fighting with the Japanese.

Why is Brodsky Wrong About Shevchenko?

Shevchenko was not one of Brodsky’s favorite poets.

If Brodsky had known Shevchenko’s biography at all, he would probably have known it only in general terms. But, paradoxically, the two poets were linked by at least several circumstances: their confrontational position of “a poet against authority,” their arrests, exiles, oppression by authorities, prohibitions imposed on them (for Shevchenko to write, for Brodsky to publish), the location of important parts of their lives (Shevchenko’s Saint Petersburg and Brodsky’s Leningrad), and, to a certain degree, also by the language, because Shevchenko also wrote poetry and prose in Russian.

In the last line of his poem “On the Independence of Ukraine,” after a long tirade full of historical ruminations, Brodsky turns to poetry as the highest authority to judge history, and calls up two names — Pushkin and Shevchenko. For Brodsky, it is both characteristic and perfectly understandable: considering poetry the highest form of artistic expression and the highest form of language, he absolutely could not limit himself to historical arguments or to his personal emotional reactions. Pushkin and Shevchenko are the two judges Brodsky appeals to in order to justify or reject Ukrainian independence and to assess its achievability. Isn’t this why his neutral-positive statements about Pushkin and extremely negative statements about Shevchenko become synonymous with his view on the whole national traditions that stand behind those names?

Brodsky condemns “Taras’s gibberish” not only from the point of view of his poetic or aesthetic standards. We don’t even know which of Shevchenko’s works he had read, or if he had read any. Perhaps he just imagined Shevchenko’s writing, or he had read something in the Soviet press in 1961, during the centennial of Shevchenko’s death. Or maybe he came across some selection of his work in literary textbooks. Was that enough to say that everything in Taras is “gibberish,” that his Ukrainian history, or his Ukrainian perspective on history, is a myth, that a direct response to Shevchenko’s treatments of history and mythology (“The Dream,” “The Caucasus”) is Pushkin’s poem “Poltava”? [Poltava was the site where Peter the First defeated Charles the Twelfth of Sweden, establishing Russian supremacy in Eastern Europe.]

“The material a poet uses is his personal history; this material, if you want, is itself history,” Brodsky once said.

Pushkin, incidentally, belonged to Brodsky’s canon. In Akhmatova’s circle, Pushkin generally occupied a prominent place. In addition, the physical environment — Tsarskoye Selo, Saint Petersburg, the Moyka River — enhanced Pushkin’s presence in the group’s conversations about poetry and poets. In a picture taken in New York by Marianna Volkova we see Brodsky, dictionaries, and a bust of Pushkin. While talking about Akhmatova’s circle, known as the Four Akhmatova Orphans, he draws the following parallels: Yevgeny Reyn is Pushkin, Dmitry Bobyshev is Delvig, Anatoly Nayman — Viazemski, and he, Brodsky, is Baratynsky. Irena Grudzińska-Gross finds a number of Pushkin motifs in Brodsky — first of all the motif of Ovid and the empire from Pushkin’s “Kishinev” cycle and Brodsky’s references to Pushkin in the poem “Sophia.” She remembers that in Brodsky’s opinion the Poles had an innate aspiration for independence. Why didn’t he see such an aspiration in Ukrainians? He did not want to? He couldn’t?

Brodsky’s article in The New York Times was prompted by Milan Kundera’s essay on the nature of totalitarianism, on the Prague events of 1968, on Dostoyevsky, and on Kundera’s own anti-Russian feelings. Brodsky’s response had a polemical title, “Why Milan Kundera Is Wrong about Dostoyevsky.” Its polemical character clearly suggested that the author will try to build his own argument by countering the arguments of his opponent. Kundera did not attack Russian culture. He merely expressed the feelings of a Central European who had suffered the consequences of a violent death of this culture, even though it can boast the names of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy. Brodsky, as a representative of a culture which was imperial to the core, and which was rolling its tanks into Prague, reacted mainly in defense of his own comfortable feelings about this culture and its place. It was a defense of his private well-being.

Poetry, of course, is not an essay, and by its very nature a poetic text is a confluence of many different intellectual and emotional stimuli. “On the Independence of Ukraine” is just one of many episodes in Brodsky’s wrestling with his historical and political beliefs, which he tends to elevate to the aesthetic domain. Shevchenko and Ukraine, Kundera and the Czech Republic, provoke his hostility because the content of these notions does not agree with the content of his own views on history. The polemic in Lisbon between Miłosz and Brodsky about Central Europe was yet another piece of evidence that Brodsky wasn’t particularly concerned about the rules of polite behavior; his emotions sometimes got the better of his common sense.

Finally, it must be said that Brodsky’s poem is in fact a provocation and not a polemic (there is no use debating him in this particular case, not least because he firmly shuts down the possibility of such debate). If this is true, then the poet has expressed the collective subconscious of a certain part of Russian intelligentsia, which takes a similar position toward Ukraine. Such attitudes have been revived in contemporary Russia and reached the level of official discourse because of the weakening and waning of Ukrainian pro-European forces.

*

Joseph Brodsky’s frequent visits to Italy opened before him a vista of imperial artifacts mutilated by history — the broken teeth of the Colosseum — as well as the panorama of eternity. In a sense, the same panorama can be found in New York, but is forever linked to Venice, with its constant floods, its watery element, its ships, docks, harbor cranes, the smell of seaweed, and the crying of seagulls. The poet, born in Leningrad, caught by death in New York, and put to rest in Venice, strung these cities together on the thread of his biography — a biography tied to architecture and water that rises and falls not only with yachts in their moorings, but with the rhythms of history, the wavelike sinusoids of time, the fates of poets, and the fishing corks of local anglers.

Joseph Brodsky was full of contradictions in his poetry as well as in his life with its poetic myths, farewells and returns, streets and cities, the Russian word and the Jewish fate. “I was blamed for everything but the weather.” I don’t want to blame the poet Brodsky, but want to understand him.

When his son visited him in New York, Brodsky wanted to take him and the whole company to dinner in Chinatown, which was not far from Morton Street. For quite some time he couldn’t decide whether to walk there or go there by car. Finally they went by car, but Brodsky wanted to give his son a farewell present and stopped by a store with military apparel where he bought a quite expensive leather U.S. Air Force jacket. His son and the other guests were baffled by this gesture because for the same money one could buy many pairs of jeans, sneakers, and t-shirts — exactly what his son wanted and asked for. But handing him the store bag with the jacket, Brodsky said: “I have never had such a jacket, and I always dreamt about it.”

Poets tend to make mistakes, take quick offense, and ignore obvious facts when their own histories are contradicted by the history of others.

After Brodsky’s death, his beloved Venetian lions with faces soaked in salty seawater stand as silent witnesses and guardians of his poetry, channels glimmer in the moonlight like rings on Venice’s aged hand, floods submerge the island of Saint Michaele, and the lions’ bronze wings cast their shadows on the encroaching waters.

Sometimes I think that poetry flows higher than the water that advances, like barbarians, upon a Rome long-gone.

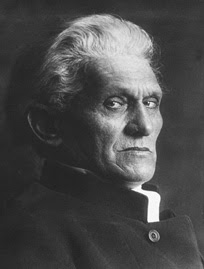

Brodsky on his balcony in Moscow, 1963

https://www.arrowsmithpress.com/venetian-lion?fbclid=IwAR16qgPcEmBVKnBVypgxmjlwwVkQDv_Lwp1cfx4wAmzBFkR2al9AtL9gcPs

*

PUTIN WANTS A LARGER WAR, NOT AN OFF-RAMP

~ “These amendments are written for a big war and general mobilization. And the scent of this big war can already be smelled,” Andrei Kartapolov, the head of the Duma’s defense committee, said this week as the Russian parliament rushed to adopt a new law. The legislation enabling the Kremlin to send hundreds of thousands more men into combat reveals a sad truth: that far from seeking an off-ramp from his disastrous war in Ukraine, Vladimir Putin is preparing for an even bigger war.

It is understandable that many in Ukraine and the west want to believe that Russia’s president is cornered. The Ukrainian army is gradually reconquering lands occupied by the Russians and has shown itself capable of striking deep into enemy territory — even into the Kremlin itself. The sanctions pressure on Russia is mounting. For now, the west remains united in support of Kyiv, and streams of modern weaponry and money sustain the Ukrainian war effort. Finally, the mutiny staged by the Wagner mercenary boss Yevgeny Prigozhin and visible conflicts among senior Russian military commanders add to hopes that the Kremlin’s war machine will break down.

Things likely look very different to the Kremlin, which believes that it can afford a long war. The Russian economy is forecast to record modest growth this year, mostly thanks to military factories working around the clock. Critical components such as microchips needed for the defense industry are arriving from China and other sources. Despite sanctions, the Kremlin’s war chest is still overflowing with cash, thanks to windfall energy profits last year and also to the adaptability of Russian commodities exporters, who have found new customers and who settle payments mostly in yuan. If budgetary pressures were to become more acute, Russia’s central bank could further devalue the ruble, making it easier to pay soldiers, defense industry workers and the internal security forces who keep the Russian elite and public repressed and largely in line with Putin’s disastrous course. When it comes to the war itself, the Kremlin still seems unperturbed by the Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Even if Kyiv makes more advances, the Kremlin may brush them off as temporary. Putin is banking on the fact that the Russian manpower that can potentially be mobilized is three to four times bigger than Ukraine’s, and the only pressing task is to be able to tap into that resource at will: to mobilize many more men, arm them, train them and send them to fight. This is precisely the purpose of the new law, which should help the Kremlin to avoid another official mobilization.

From now on, the government can quietly send draft notices to as many men as it deems necessary. The upper age limit for performing mandatory service will be increased from 27 to 30, and could be raised again in future. Once an electronic draft notice is issued, Russia’s borders will be immediately closed to its recipient in order to prevent a massive exodus of military-age men like the one Russia witnessed last autumn. The punishments for refusing to serve have also been ramped up. These moves, combined with massive state investment in expanding arms production, should help Putin to build a bigger and better equipped army.

A parallel tactic is the strangulation of Ukraine’s economy. Knowing that the Ukrainian budget is on life support provided by its western allies, the Kremlin wants to deny Kyiv all sources of revenue. Moscow has therefore not only pulled out of the grain deal that had enabled Ukrainian agricultural exports via the Black Sea, it has also launched massive air strikes against Ukrainian ports to destroy any possibility of reviving the agreement. The same logic underpins Russia’s air strikes against civilian infrastructure: they are aimed at making Ukrainian cities uninhabitable and preventing reconstruction efforts.

The Kremlin hopes that the rapid rebuilding of the Russian army and gradual decimation of the Ukrainian economy and armed forces will result in growing western frustration and a decline in material support for Kyiv. To speed up this process and break the west’s will, Moscow is using threats of escalation, including expansion of the conflict towards Nato territory via Belarus with the help of Wagner mercenaries based there.

Putin has made plenty of fatal mistakes. But as long as he is in charge, Moscow will dedicate its still vast resources to achieving his obsession with destroying and subordinating Ukraine. As western leaders think about policies to support Ukraine into the third year of this ugly war, any long-term strategy must take this reality into account.

Mansion of Baron Kelch in St. Petersburg

This mansion, built for Alexander Kelch, in his day one of Russia's richest men, was designed by three different architects each of whom contributed their own ideas and solutions. The splendid facade takes its inspiration from French Renaissance models, the courtyard is predominantly Gothic, the servants' quarters are art nouveau, while the interiors opt for the ornate luxury of baroque and rococo. All of this was put together in 1903, making the Kelch Mansion an archetypal example of the turn-of-the-century trend for eclecticism in Russian architecture, especially in St. Petersburg. (Photographer: Elisio Pina)

THE COMIC ASPECTS OF PUTIN’S RUSSIA

~ Russian state TV is comedy gold. And Russian propaganda is hilariously bad, cringeworthy and funny. It is just lie after lie after lie. If people truly believe that crap, and clearly they do, then there is a serious education problem in that country. And that’s just for starters.

The constant crying and whining about nobody liking them and the whole ‘Russophobia’ thing I find hilarious. They claim everybody, or a select few it depends on whether they decide a country is in the “friend zone” or an “unfriendly country”, hates them — whilst being the most combative, spiteful and hateful country on the planet earth. Hello? Irony?

Russia: “We hate everyone, cause they’re satanic and evil, and we are the saviors of the universe.”

Erm, yeah right, okay. Whatever floats your boat. Or in the case of mother ruzzia, sinks it. Through no fault but their own by the way. Russia is psychologically disturbed with superiority tendencies and inferiority complexes. Hilarious. ~ Frances Neil, Quora

Mykola Banderachuk:

Ruzzia has some top grade comedy writers and comedians — a comedy club with nukes.

Sean Brisbane:

Russian propaganda isn't meant to be believed outside of Russia. The intent is to make people doubt whether there is an objective truth that can be known. In that it has been quite successful at least in US and UK, France.. I'm sure many more.

Frances Neil:

Their imperialist thoughts and delusions of grandeur and superiority betray them every time. Karma is coming.

Carol Bewick:

Russia IS the most evil, spiteful and hateful country on the earth, and I am saying this with a poker straight face. Russia is the cancer of the world.

Horst von Brand:

They know it’s all smoke, mirrors and blatant lies. But keeping the mouth well shut is prudent under a dictatorship in dire straits.

Chris Brisbane:

Putin is turning Russia into a third world country.

The only thing left will be lots of lonely wives and mothers.

And some nice architecture in St Petersburg. Perhaps as a museum for people to visit, to see what Russia may have been without corruption.

*

THE WORST THING ABOUT COMBAT

Most civilians have watched enough war movies or read books to know about the technical aspects of warfare and how it looks like.

However, what you can’t imagine unless you have experienced it by yourself is the enormous fear during combat. This is a completely different level of fear than anything that you can experience in civilian life:

Imagine the feeling in your guts when you are driving a car and you have just avoided a collision or a serious accident with another vehicle. Take this moment of fear and multiply it by a hundred.

Unlike in an accident situation, however, battlefield fear doesn't subside after a few moments. It stays with you and gets stronger. It completely wears you out, eats up your soul, and slowly drives you crazy. ~ Roland Bartetzko, former soldier, Quora

*

“SECRET GERMANY”: THE VALKYRIE PLOT TO ASSASSINATE HITLER

~ In the film Valkyrie, Tom Cruise plays Colonel Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, the man who, on 20 July 1944, placed a bomb next to Hitler in his east Prussian headquarters, the Wolf's Lair. The bomb failed to kill Hitler, merely blowing his trousers to ribbons. That night, when the coup was seen to have failed, Stauffenberg was shot in the courtyard of the army headquarters in Berlin on the orders of General Fromm, his superior, who was in on the plot and hoped — in vain — to save himself. Sandbags were piled in the courtyard and the lights of staff cars illuminated the victims. Von Haeften, his aide, threw himself in front of Stauffenberg. He and two others were also shot that night and their bodies quickly buried. Stauffenberg died with the words "Long live our sacred Germany" on his lips, or perhaps — some heard — "Long live our secret Germany”.

The producers of Valkyrie have muffled his last words; the story behind secret Germany does not figure in their script, but they were clearly aware of its significance. Within a few weeks, 80 plotters had been executed in Plötzensee prison by slow strangulation, hung from meathooks; in all, at least 3,000 were killed and many children, including Stauffenberg's, were taken from their families and placed in orphanages. Many of those executed were from Germany's most distinguished families, people who, like Stauffenberg, were appalled by the direction Germany had taken, both in relation to the Jews and to the disastrous war in the east.

The film is true to most of the facts of the plot, but fails to convey any sense of the catastrophic moral and political vortex into which Germans were being drawn. Nor does it give much sense of the immense charisma of Stauffenberg, to whom generals and politicians deferred and who had for some time been tipped as a future chief of staff. A revealing private memoir I was given, which describes a visit shortly before the bomb plot by Stauffenberg to one of the other resister's houses, suggests that the female staff were sent into paroxysms of adoration by the wounded hero. And the film gives no indication at all of Stauffenberg's background and philosophy: he fitted perfectly into the German tradition of Dichter und Helden, poets and heroes. For a start, he looked the part, tall with classical features; he was often compared to a medieval statue of a knight in the cathedral at Bamberg, his home town, and his wedding in this cathedral in 1933 to Nina von Lerchenfeld was a huge social event. Even Hitler believed that Stauffenberg was the embodiment of a German hero.

So when the generals failed in their plots against Hitler — there were as many as 15 of them — someone was needed to head the disparate but substantial resistance, which extended from the army into the Foreign Office, the secret services and to important clerics and trade unionists. Stauffenberg was persuaded by his uncle, Nikolaus Graf von Üxküll, long disenchanted with the Nazis, that he should lead the movement. It seemed that he was the man who unmistakably wore the mantle of a near-mystic German past, a warrior Germany, a noble Germany, a poetic Germany, a Germany of myth and longing.

There is nothing in the script or in Cruise's performance that explores these particularly German preoccupations. At times Cruise looks and sounds like the troublesome cop who has been given a tricky assignment, with 24 hours to get the bad guy before he has to hand in his badge: the assassination attempt is treated as a thriller. It lacks the intelligent understanding that Florian von Donnersmarck brought to The Lives of Others (2006), as people from different backgrounds, and with wildly different ideas of what Germany should become, tried to work together.

Stauffenberg's stroke of genius was to subvert the emergency plan for defending Berlin against insurrection, Valkyrie, into a plan for a putsch after Hitler had been killed. As Hitler became more paranoid, it seemed that Stauffenberg was the only one who had both the access and the resolve to kill him. He was fully aware that the chances of success were slim, but he felt that he needed to demonstrate to the world that there was a better Germany — what he thought of as secret Germany — and perhaps that he was the agent of history.

When I was writing my book The Song Before it is Sung, about a conspirator in the bomb plot, I was puzzled for some time that the British refused to trust the various overtures from the resistance in Germany. Stauffenberg was a close friend and confidant of Adam von Trott, the Rhodes scholar who was also deeply involved in the resistance and executed a few weeks after the July plot. I also pondered the question of why Trott's friend at Oxford, Isaiah Berlin, a magnanimous and generous man, came to distrust him, and I wondered why, 30 years later, he wrote in a letter to Shiela Grant Duff, who knew them both well, saying that Trott was no hero and "not on our side". What he saw, I think, is that in ideas of a mythic German past, and in the belief in a historical destiny, lay the genesis of Nazism.

The idea of a noble Germany, uncorrupted by racial inferiors and alien philosophies, a Germany that would be led by a world figure, was not invented by Hitler. Long before he came along, the simple word Führer — leader — had been turned into something messianic, and I think Berlin knew where the blame lay. During their walks and discussions in Oxford, Berlin often said to Trott that when he was at a loss, he turned to Hegel. Hegel believed, essentially, that history had a forward motion to a point where all contradictions would be resolved.

It is ironic that Stauffenberg's son should have been contemptuous of the notion of Tom Cruise playing his father, on the grounds that he is a cultist, because Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg and his two brothers, Berthold and Alexander, were themselves members of a cult that formed around a mythical secret Germany; their master was the poet Stefan George. George is a sinister figure, but in an American newspaper article of the 1920s he was rated one of the most important men in the world. Hardly remembered and little read today, he was a poet who rivaled Hölderlin and Schiller in his fame.

The Stauffenberg family had held the title of "Schenk", which meant "cup-bearer", since the 13th century, an honor bestowed on them by the Hohenstaufens, the legendary monarchical family of Swabia who also ruled Sicily in the Middle Ages. At the time of Stauffenberg's birth in 1907, his family was to be found at the Altes Schloss in Stuttgart, in the service of the Württemberg monarchy. The Stauffenbergs were a family steeped in tradition, highly cultured, highly regarded.

It was hardly surprising that Stefan George welcomed these good-looking and aristocratic brothers into his circle. This may in part have been because of the homoerotic element in his movement, but it was also because the Stauffenbergs represented everything George felt had been lost in Germany — the medieval greatness of the Hohenstaufen Friedrich II and the warrior qualities of the Teutonic Knights. Poetry was to lead the way back to greatness, and George was Germany's poet; he and his disciples propagated the notion of a unique German-ness, Deutschtum, which was traced back to Friedrich II.

Members of the George circle were subject to some bizarre rules. Only Claus von Stauffenberg kept his own name, presumably because of its flattering historical resonances. His brother Berthold was told not to marry the woman he loved, and he obeyed, at least until George was dead. But even after the war, the surviving brother, Alexander, eulogized George as the spokesman of something uniquely German. Göring revered him too, and after the Nazi takeover of 1933 wanted to instate him as the head of an academy of poetry. George replied that he had for a long time been the leader of German poetry, and didn't need an academy. His circle had many Jewish members, but his views became broadly antisemitic as the Nazis became more important. None the less, he fled to Switzerland and died before it was completely clear where he stood on national socialism.

The Stauffenberg brothers were made George's heirs, and after his death tended his grave in Switzerland and continued to organize candlelit readings of his poetry.

As the war progressed, Stauffenberg enjoyed a rapid rise in the army. He was at first enthusiastic about military successes on the eastern front, but had for some time been deeply alarmed by Hitler: Kristallnacht had disgusted him, particularly as his brother was married to someone of Jewish descent. He quickly became aware that the SS, the SD and the Gestapo were creating a lasting legacy of hatred that would one day be avenged. He began to seek out like-minded officers and spoke at times quite openly about his fears for Germany and the army. Sometimes he recited George's poem "The Antichrist" to support his argument.

As the advance east was halted, it became more urgent to end the war with at least something of Germany intact. Stauffenberg had particular cause for alarm: he was in charge of logistics for the 10th Panzers and knew that for every thousand casualties, only 300 replacements could be found — disaster was inevitable. At the same time he found himself increasingly appalled by the indiscriminate killing of Jews, Slavs and Russian prisoners, and by the SS battalions' unbridled lust for murder, which was having a corrupting effect on the army too. He often ignored or changed orders: he managed to thwart an order that all Russian prisoners should be tattooed on their buttocks.

After Stalingrad, his outspokenness caused some of his superiors to decide that he should be sent to north Africa, which was relatively free of the SS. There he was severely wounded, losing part of his right arm, one eye and two fingers on his left hand. Through determination he made a dramatic recovery and found himself second in command of the home army in Berlin, under General Fromm, and was also appointed to the general staff, which gave him access to Hitler.

After his first visit to the Berghof, he described the atmosphere there as "stale, paralyzing, rotten and degenerate". A few months later, he primed the bomb with the three fingers of his left hand and placed it beside Hitler.

The question the film does not raise is what kind of Germany Stauffenberg envisaged had the coup succeeded, which in all probability it would have, had Hitler been killed. Stefan George's poem "Secret Germany" was the inspiration for Stauffenberg's oath of mutual intent for the conspirators, which was typed by his brother Berthold's secretary:

We want a new order which makes all Germans responsible for the state and guarantees them law and justice; but we despise the lie that all are equal and we submit to rank ordained by nature. We want a people with roots in their native land, close to the powers of nature, finding happiness and contentment in the given environment, and overcoming, in freedom and pride, the base instincts of envy and jealousy. We want leaders who ... are in harmony with the divine powers and set an example to others by their noble spirit, discipline and sacrifice.

When Stauffenberg's body was burned, a ring was lost with it. Engraved on it were the words FINIS INITIUM, which is drawn from another of George's poems with the final line "I am the end and the beginning”.

This wasn't the Germany that the allies had in mind.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jan/10/valkrie-tom-cruise-hitler-plot

Joe:

The book The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich discusses Valkyrie’s plot to assassinate Hitler. Since the publication of this book, some historians and journalists have romanticized the Valkyrie conspirators as men who challenged Hitler’s vision of a new Germany. Their description of the plot is not accurate. These men believed in Hitler’s vision of a German Empire stretching from the Sea of Japan (East Sea) to the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. They did not disagree with the Holocaust or the enslavement of the Slavic nations, but they disagreed with the ineffectiveness of Hitler’s military strategy.

Their plan was to keep as much of the territory that Germany had conquered before their early losses to the Allied forces. They thought that Hitler was negating the army’s chances by refusing to change his positions on death instead of withdrawing to regroup for a counterattack and reestablish their supply chain. They hoped to hold out until the American Republican Party came to power and changed their support from the Allied armies to Germany. Their belief centered on two lines of thinking. One was that the Charles Linberg wing of the Republican Party was Nazi sympathizers.

Oriana:

I happened to visit the “Wolf’s Lair” in Pomerania where the attempted assassination took place (Koszalin; it’s now a tourist attraction). Seems that Stauffenberg wasn’t able to place the suitcase with the bomb close enough to Hitler, and that a thick table leg blocked enough of the bomb’s explosion so that Hitler ended up being tossed out of the window by the force of the explosion, and ended up with just bruises. Hitler decided that “Providence” was protecting him in a Gott mit uns manner.

Poles saw the swastika as a "Broken Cross," a blasphemy. This also happpened to fit with one of the prophecies of Nostradamus. In a desperate situation, this helped the morale. Hitler as anti-Christ is almost too obvious.Yes, just as you point out, Staufffenberg also believed in Hitler's racist theories. He was very brave., but alas, we can't revere him as a hero because he was a dedicated Nazi.

*

OPPENHEIMER ON EINSTEIN

“Though I knew Einstein for two or three decades, it was only in the last decade of his life that we were close colleagues and something of friends. But I thought that it might be useful, because I am sure that it is not too soon—and for our generation perhaps almost too late—to start to dispel the clouds of myth and to see the great mountain peak that these clouds hide. As always, the myth has its charms; but the truth is far more beautiful.

Late in his life, in connection with his despair over weapons and wars, Einstein said that if he had to live it over again he would be a plumber. This was a balance of seriousness and jest that no one should now attempt to disturb. Believe me, he had no idea of what it was to be a plumber; least of all in the United States, where we have a joke that the typical behavior of this specialist is that he never brings his tools to the scene of the crisis. Einstein brought his tools to his crises; Einstein was a physicist, a natural philosopher, the greatest of our time.

Einstein is often blamed or praised or credited with these miserable bombs. It is not in my opinion true. The special theory of relativity might not have been beautiful without Einstein; but it would have been a tool for physicists, and by 1932 the experimental evidence for the inter-convertibility of matter and energy which he had predicted was overwhelming. The feasibility of doing anything with this in such a massive way was not clear until seven years later, and then almost by accident. This was not what Einstein really was after. His part was that of creating an intellectual revolution, and discovering more than any scientist of our time how profound were the errors made by men before then. He did write a letter to Roosevelt about atomic energy. I think this was in part his agony at the evil of the Nazis, in part not wanting to harm any one in any way; but I ought to report that that letter had very little effect, and that Einstein himself is really not answerable for all that came later. I believe he so understood it himself.”

~ Robert Oppenheimer, 1965

Einstein and Oppenheimer, 1930s

*

BARBIE AND MAKING DECISIONS

~ The Barbie movie is a huge hit. Not just with critics, but also with the audiences, especially young audiences. In some ways, this is not that surprising, given the enormous global promotion the movie got and the ongoing nostalgia for anything Barbie-related. On the other hand, neither the ad campaign nor the nostalgia explains why the Barbie movie has become not just a box office success, but also a cultural reference point that people keep on rewatching. Another explanation has to do with the ways in which the film paints a picture of the psychology of Barbie's decisions that is relatable to all generations.

The Barbie nostalgia is, in any case, limited to the first couple of minutes of the film, where we get introduced to the almost painfully pink world of Barbieland, where every day is perfect. But no matter where you were hiding recently, you probably knew these images from the trailers and posters anyway. The problem with Barbieland from a narrative point of view, is that it is difficult to put together a feature-length story arc in a perfect world. After all, what kind of conflicts and dilemmas could there be in a world where every day is perfect?

And here the film employs a surprising twist of making Barbie face decisions that make her relatable to all of us: decisions where she has to choose between something extremely familiar and something unknown. What is even more surprising is that Barbie faces such dilemmas not once, not twice, but three times. First, when she needs to choose between staying in Barbieland and going to the Real World to fix things. Second, when she is facing the dilemma of going back to the box or not. At the end of the movie, the choice between living in Barbieland and living in the Real World.

The structure of these three decisions is extremely familiar to all of us. We face decisions of that kind, between something we know and something entirely unfamiliar. When you contemplate getting married, having kids, getting divorced, taking a new job, moving to a different country or city, or even an apartment, all these decisions have the same structure. You know one option very well. You know the disadvantages, but also the advantages. And you only have some very faint ideas about the other option.

How do we actually make decisions of this kind? Here, we have a fair amount of findings in the psychology of decision-making and they all point in the same direction: given that we have no firm information about one of these options, it is imagination that plays a significant role in these decisions. You imagine yourself in your new job in an unknown country and see how that feels. Of course, imagination is not a particularly reliable guide to how things actually are, which makes these decisions not exactly rational.

But rationality is not the point of these decisions either. It is not even clear what would count as a rational decision in these contexts. When we make these decisions, we imagine our future selves in these situations, but the future self is, to a large extent, the product of exactly the decision we are making now. In some of the most important decisions we make, there is no right or wrong decision. These decisions mold your future self.

And this is exactly the way Barbie makes her grand decisions between Barbieland and the Real World. Her first decision, with allusions to the Matrix-esque blue pill versus red pill dilemma, turns out not to be a real decision as she has to go to the Real World to fix things. But in her other decisions, she faces the choice between something that feels familiar and cozy (the box or Barbieland) on the one hand, and something scarily unfamiliar and not at all cozy (the Real World) on the other. She consistently chooses the unfamiliar option, and, in the dramatic climax of the movie, does so very explicitly with the help of her imagination.

On a very simple level, the main narrative challenge of a film about Barbie is to make Barbie relatable to the audiences of today. The problem is that Barbie's life is perfect, but our lives are far from perfect. How and why would we then relate to Barbie's ideal life? And the surprising solution to this narrative puzzle is to make Barbie face decisions we all face and struggle with them the way we struggle with them. This psychological complexity may not be what many spectators went to see this movie for, but this is a big part of what makes this film an unlikely audience favorite. ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psychology-tomorrow/202308/why-is-the-barbie-movie-so-popular

*

TO BE HAPPY, THINK LIKE AN OLD PERSON

It’s counterintuitive that old people can be happier. As we move closer to death, we become invisible and are considered a drain on the economy.

When I turned 60, all I saw ahead of me was decline. Then I met a man who said, “I’m 82 and this is the best time in my life.” I wondered, What does he know that I needed to learn?

Laura Carstenson studies aging and happiness. She found older people are happier than middle-aged and younger people. Many researchers have replicated her findings.

Changing Demographics

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, since 2010 the 65-and-older population has increased by 34 percent. It reported that over the last decade, the growth of the “non-working-age, dependent” population has outpaced the growth of the working-age population.

I object to the characterization of this population as “non-working” and “dependent.” Adults aged 65 and older are twice as likely to be working today compared with 1985. Many of them are making good money. More than 20 percent of adults over age 65 are either working or looking for work. The Census Bureau paints a picture of a smaller group of young people caring for helpless old people. Politicians have taken note as they threaten to raise the age for Social Security.

Old people are a reservoir of wisdom and experience. They may work at a slower pace but they are a valuable contribution to the workforce. Old people are a resource that can solve some of the problems of workforce shortage.

An encore job gives life meaning. I’m now 80 years old and I work. Work gives my life meaning. I wrote two books after I turned 65. I am not dependent! Of course, how much education we have and what type of work we do shapes our being able to work past the traditional retirement age.

The Paradox of Aging

In the 1980s, society considered old age pathological: depression, anxiety, and the loss of cognitive function and memory were inevitable consequences of aging.

Americans worship youth and spend billions of dollars annually in the pursuit of youth. We’re told: To avoid a descent into despair, buy this product.

The paradox of aging is that even though people's physical health and functions decline in later adulthood, happiness does not. Many studies show that depression, anxiety stress, worry, and anger all decrease with advancing age.

Recognizing we won’t live forever changes our perspective in positive ways.

Mental Health Improves with Aging

Aging is not a disease; dementia is. Unfortunately, dementia and aging are often used interchangeably. Dementia is not an inevitable consequence of aging. It is ominous to consider 10 percent of the aging population has dementia. But it looks much different when we acknowledge that 90 percent of the elderly are not demented.

Old people process information more slowly. This can frustrate the older person and cause them and their loved ones to worry about dementia. But a longer response time decreases impulsivity; we have more time to think through the problem and give a considered response.

Chronological age is just a number. We have a physical age, a psychological age, and a sexual age. They vary from individual to individual and from time to time.

In many areas, things improve as we age:

Acceptance of self and others

The desire for a deeper connection

Wisdom and empathy

Capacity for forgiveness

Gratitude

Resilience

Less emotional volatility and impulsivity

Don’t measure time; experience it

As we age, our time horizons grow shorter and our goals change. Older people direct their cognitive resources to positive information more than to negative.

I learned from that 82-year-old man that we can either measure or experience time. I was always busy, and in America, being busy is a badge of honor. I rushed from appointment to appointment, meeting to meeting.

Then, I recognized the oppressive power of ambition. I began to think, "Do I want to spend the rest of my life the way I’ve lived the first part?" My priorities changed as I moved closer to death.

Time still carries a sense of urgency, but the urgency of time has been transformed. I no longer see time as an endless series of appointments moving from one goal to the next. Now the urgency is to experience every moment and not waste the time that remains.

Perceiving the future

Younger people focus more on goals linked to learning, career planning, and new social relationships that may pay off in the future. As a young person, I felt no constraints on my time.

Every day, things happen to remind me of my mortality, and they seem to come at me with increasing frequency. As I grew older, I began to focus my attention on the positive aspects of my world. My goals shifted to ones that have emotional meaning. I live in the moment and let the future take care of itself.

I focus more on current and emotionally important relationships. I work, but only where and when I choose to. I decided never to sit through a boring lecture and never to go to cocktail parties to network. I would never wear a necktie because I refused to do what others expected of me.

I didn’t worry about dying but only how I would die. I wanted to avoid a lingering death, and I discussed that with my family and my doctor.

My social network shrank, but I pursued the most important relationships. I began to savor life, ignore trivial matters, appreciate others more, and found it easier to forgive. The more I did this, the happier I felt.

I experienced losses, but I became more comfortable with the sadness. Life became more than a series of painful events. I experience more joy, happiness, and satisfaction.

I no longer believe there’s always tomorrow. I have no promise of a tomorrow, so I’m going to make the best I can of today. I will let the future surprise me; it will unfold as it will.

*

Do you value being busy more than an adventure or spending time with your family? If you’re still years away from retirement, don’t wait until you’re 65 to experience the urgency of time. Why spend 30 to 40 years in retirement? Borrow time from our retirement years while you’re young.

Get off the treadmill now. Be happy like old people.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/finally-out/202307/to-be-happy-think-like-an-old-person

*

A WORLD WITHOUT MARRIAGE?

~ Nearly three decades ago, Princess Diana famously said, “There were three of us in the marriage,” and the world has never forgotten. But in the U.S. (and other places, too), there are three entities in every marriage—the two spouses and the government.

What’s the government doing there? In her just-published book, Moving Past Marriage: Why We Should Ditch Marital Privilege, Eschew Relationship-Status Discrimination, and Embrace Non-marital History, literature professor Jaclyn Geller of Central Connecticut State University makes a compelling case for getting the government out of the marriage business. Of course, in the U.S., that is a highly unlikely possibility, at least in the short run. But individuals can make the choice not to marry.

But why should two people who love each other, and want to commit to each other, choose not to marry? The subtitle says it all, and those three arguments are presented compellingly, and with considerable wit, throughout the book.

First, ditching marital privilege: Government-sanctioned marriage unfairly privileges married people. I have often mentioned the hundreds of benefits and protections that people get just for being legally married. The legalities are just the start: married people are privileged in many other ways as well.

Second, ending relationship status discrimination: The disadvantaging of people who are not married, and the people who matter to them, is the flip side of advantaging married people.

Third, embracing non-marital history: Geller scours centuries of history to unearth the unheralded place of people who have never married:

“Such individuals kept showing up as achievers, community builders, and thought leaders. I discovered never-married forbearers whose numbers were substantial; they were neither a tiny minority nor a lunatic fringe. Their impact on culture was incalculable.”

It’s Personal: How Singlist Laws and Policies Matter in Our Lives

About those ways in which married people are elevated above all others and people who are not married are devalued—to Geller, all that is personal. She has deep, long-lasting, and sustaining friendships; she is very close to her sister; and she has been in a romantic relationship for years. But legally (and informally, too), none of those people count, not the way a spouse would.

Rather than just reciting the laws and policies that separate the married from the not-married, Geller shows us, in dozens of ways, how they matter in her own life. For example, she has paid into Social Security with every paycheck. She wants to name her sister as her beneficiary. Surprise! She has never been married, so she can’t name a beneficiary. When she dies, her contributions go back into the system, a system that uses that money to pay benefits to married people’s surviving spouses and maybe even an array of ex-spouses, if they meet certain requirements.

If Geller’s sister, or her romantic partner, or one of her cherished friends falls ill, she cannot take time off under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act to care for them—and they cannot do the same if she needed their care. The issue isn’t just that the important people in the lives of the never married are not protected in this significant way and so many others; it is also that, much more broadly, they just aren’t regarded as important. Friends are seen as “just friends.” No matter how close a lifelong single person may be to a friend or relative, no matter that their relationship may have lasted far longer than many marriages, no matter how interconnected their lives may be, none of those people will count as a “significant other.”

Marital status discrimination goes beyond just federal laws. There are state and local laws, too, that unfairly privilege married people and disadvantage never married people. There is singlism in many policies and practices—in workplaces, marketplaces, religious institutions, and just about every significant domain of life. For example, do you think spousal hires are a good idea? Geller has a thing or two to say about that.

Her one-sentence answer to the question of why we should move past marriage is this: “Pushing for a marriage-free society, we nonmarital Americans can celebrate our lives, savoring the joys of living alone; creating fluid, loving families; and giving our partnerships respect that the current marriage system withholds.”

Moving Past Marriage is chock full of points worth pondering. Here I’ll mention just a few.

Progress Happens, But Sometimes It Is Rendered Invisible:

Laws and policies and practices do sometimes change in the direction of greater fairness for people who are not married. For example, Geller notes that in 2010, the Obama administration updated hospital visitation rules, such that hospitals participating in Medicaid or Medicare would need to honor patients’ wishes about visitors. “Spouses would no longer get automatic top billing.” The president’s memorandum about these new rules, though, never mentioned this provision. The relevance of the rules for race, sex, sexual orientation, and religion was noted, but marital status did not make it into the memorandum.

Change Toward Greater Fairness:

Slow and Steady? I’ve always imagined that change toward greater fairness for singles would be incremental. Geller believes that something different may happen—that there will be a “galvanizing moment after which nothing is the same,” comparable to what happened after Stonewall or the Seneca Falls Convention.

How Marriage Gets Elevated and Stays That Way:

“Transhistorically,” Geller argues, marriage has often gotten propped up by “legal force, social pressure, religious dicta, economic rewards, status accorded those who conform, and punishments imposed on people who dissent or renege.”

Freedom from Some Financial Risks:

Divorce can be expensive. But if we were to move past marriage, Geller notes, “No one will have to worry that a truncated romance might drain them financially.”

People Who Resist Marriage Get Treated Condescendingly:

Geller’s critique of marriage is longstanding, dating back at least as far as when she published Here Comes the Bride: Women, Weddings, and the Marriage Mystique. She has thought deeply, researched extensively, and written forcefully. And yet, she has been subject to some of the same dismissive reactions that some of us who are Single at Heart know all too well—for example, she’s been told that her resistance to marriage is just a phase.

What About the Children?

Anyone who dares to challenge the special place of marriage is likely to hear that the dismantling of marriage would hurt children. Rather than just saying that children would not be harmed, Geller makes a bolder statement—she says that there will be benefits for children: “The state will remain obligated to protect minors from physical and emotional abuse. Its duty will warrant an interest in capable adult caretakers, not spouses. . . No one will be made to feel second-rate for being born out of wedlock. Without matrimony as the dividing line between family and nonfamily, nonmarital households will not be considered second rate.”

Moving Past Marriage Doesn’t Reduce Our Choices, It Multiplies Them

In 2010, Rachel Buddeberg and I shared here at Living Single the perspectives of dozens of people and organizations already arguing, in their own ways, for moving past marriage. Michael Kinsley was one of them. In “Abolish marriage: Let’s really get the government out of our bedrooms,” he explained how freeing this could be:

“End the institution of government-sanctioned marriage […] Privatize marriage […] Let churches and other religious institutions continue to offer marriage ceremonies. Let department stores and casinos get into the act if they want. Let each organization decide for itself what kinds of couples it wants to offer marriage to. Let couples celebrate their union in any way they choose and consider themselves married whenever they want. Let others be free to consider them not married, under rules these others may prefer. And, yes, if three people want to get married, or one person wants to marry herself, and someone else wants to conduct a ceremony and declare them married, let ‘em. If you and your government aren't implicated, what do you care?”

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/living-single/202306/a-world-without-marriage

Oriana:

This doesn't seem to consider the central fact: marriage is a legal contract. It delineates the obligations, privileges (in many cases, this pertains to taxes and health insurance) and protections for spouses and children.

Marriage also announces to others: we (the two spouses) are committed to each other: for better and for worse, for richer and for poorer, in sickness and in health. I call it the "covenant of non-abandonment." Getting married is the opposite of "having a fling."