*

MR COGITO AND LONGEVITY

1

Mr. Cogito

can be proud of himself

he surpassed the life span

of many other animals

when the worker bee

goes to its eternal rest

the suckling Cogito

enjoyed the best of health

at the time cruel death

takes the house mouse

he beat whooping cough

discovered speech and fire

if we take the word

of bird theologians

the soul of a swallow

takes wing to paradise

after ten

earthly springs

at that age

young master Cogito

was studying with uneven results

in the fourth grade of high school

and women began to intrigue him

then

he won the Second World War

(a doubtful victory)

just at the point when a goat

strays off to its goat Valhalla

his doings were considerable

despite a couple of dictators

he crossed the Rubicon of a half-century

bloody

but unbowed

he outdid

the carp

the alligator

the crab

now he finds himself

between the twilight

of the eel

and the twilight

of the elephant

here

to be honest

Mr Cogito’s

hopes expire

2

a coffin shared with an elephant

is not a prospect terrible to him

he doesn’t crave the longevity

of the parrot

or the Hippoglossus vulgaris

or for that matter

the soaring eagle

the armored turtle

the fatuous swan

to the end

Mr Cogito would like to praise

the beauty of what is transient

that’s why he doesn’t lap up gelée royale

or drink elixirs

doesn’t make a pact with Mephistopheles

with the care of a good gardener

he cultivates wrinkles in his face

he obediently receives calcium

being deposited in his arteries

he rejoices in memory’s gaps

memory used to torment him

from infancy

immortality

induced in him a state

of tremendum

envy the gods for what?

—sky-blue drafts

—botched management

—insatiable lust

—mighty yawns

~ Zbigniew Herbert

- - - -

Hippoglossus vulgaris = Atlantic halibut, known for its longevity

gelée royale = royal jelly, fed to the long-lived queen bee

tremendum = here it's best translated as "awe"

*

DOSTOYEVSKY IN LOVE

A projection of Dostoevsky’s portrait lights up the side of the house in St Petersburg where he spent the last years of his life

~ The first time he fell in love, Fyodor Dostoevsky was in his mid-30s. He had written two famous novels, Poor Folk and The Double, been arrested for treason, suffered a mock-execution, and served four years of hard labor in Siberia. He was now, in 1854, serving as a private in the army and the object of his desire, Maria Isayeva, was the capricious and consumptive wife of a drunkard called Alexander.

When the Isayevs moved to the mining town of Kuznetsk, 700 versts away in southwestern Siberia (a verst is roughly equivalent to a kilometer), Dostoevsky’s love seemed doomed. But then Alexander died, leaving Maria alone and in poverty. Dostoevsky sent her his last roubles and a proposal of marriage, telling the coachman to wait for her answer before making the week-long journey back through the snow. Maria turned his offer down: she could never marry a penniless private. She then fell in love with a man who was just as poor as Dostoevsky, and also a simpleton: “I barely understand how I go on living,” Dostoevsky wrote, aware that this current melodrama was repeating the plot of Poor Folk.

He eventually married Maria, and had his first full epileptic fit on their wedding night. She never recovered from the sight of his writhing, crumpled body: “The black cat has run between us,” as he put it in The Insulted and the Injured. The couple shared not a single day of happiness, but then it is hard to find many days of happiness in his story at all.

The life of Dostoyevsky was nothing if not Dostoyevskian. It was suffering, he believed, that gave value to existence: “Suffering and pain are always mandatory for broad minds and deep hearts,” he explained in Crime and Punishment. “Truly great people, it seems to me, should feel great sadness on this earth.”

His mother, who was also called Maria, had died of TB when he was 15; soon afterwards his father was found dead in a ditch, possibly murdered by the serfs on his estate. Poor Folk made him a literary sensation but earned him no money, and the little money he did earn was lost on the roulette wheel. While his novels mined the psyche, he did battle with his body: myopia, hemorrhoids, bladder infections, emphysema. By the time he was writing The Devils, his seizures had become so severe that he had no memory, when he regained consciousness, of either the novel’s plot or the names of his characters.

Dostoevsky, who died aged 56, did not write an autobiography but “buried his heart”, as Alex Christofi, puts it, in his fiction. Christofi, also a novelist, describes Dostoevsky in Love as less a biography than a “reconstructed memoir”. His method, he explains, has been to “cheerfully commit the academic fallacy” of eliding Dostoevsky’s “autobiographical fiction with his fantastical life”. This is achieved by blending his authorial voice with that of Dostoevsky, in sections lifted from the letters, notebooks and fiction and stitched seamlessly into the text. So as not to interrupt the narrative flow, the sources are given only at the back of the book. It’s a witty motif which works well, not least because it immerses us in the forcefield of Dostoevsky’s thought, which Christofi also employs to explain his own waywardness. “Facts,” as Dostoevsky reminds us in Crime and Punishment and Christofi reminds us here, “aren’t everything; knowing how to deal with the facts is at least half the battle.”

One example of how Christofi deals with the facts can be seen in the account of the mock execution with which Dosteovsky in Love begins. Segueing together descriptions from Dostoevsky’s letters with passages from The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov and The Insulted and the Injured, Christofi takes us not only into the moment when Dostoevsky faced the firing squad but also into his novelistic response to that moment: “There was no more than a minute left for me to live,” he writes to his brother. “The most terrible part of the punishment,” he reflects in The Idiot, “is not the bodily pain, but the certain knowledge that in a hour, then in ten minutes, then in half a minute, your soul must quit your body and you will no longer be a man.” The effect is of having Dostoevsky in the room with us, reliving the horror of it all while also being aware of what a good story it makes. What becomes clear is that Dostoevsky the lover was not dissimilar to Dostoevsky the epileptic, Dostoevsky the gambler, or Dostoevsky facing his death: each experience was unpredictable, dangerous and thrilling.

An illustration of Raskolnikov and Marmeladov for Crime and Punishment (1874), by Mikhail Petrovich Klodt

In addition to Maria, Dostoevsky had two further serious love affairs. Polina, the beautiful, unhinged daughter of a serf caused him nothing but grief, while Anna, the stenographer who became his second wife, stood by him while he repeatedly pawned their few belongings and then lost the money at the casino. The way he proposed to Anna, Christofi writes, “is so quietly bashful that you can’t help wanting to hug him”. He is quite right, but I won’t give away the plot.

Christofi’s interest, however, is not only in Dostoevsky as a lover of women. It is also in Dostoyevsky as a believer in Christian love. This belief lay at the heart of his novels and by the end of his life he was regarded as a prophet, spreading the gospel of universal harmony. After his famously rousing speech in honor of Pushkin, “strangers sobbed, embraced each other and swore to be better people, to love one another”. Two old men came up to tell him that “for twenty years we’ve been enemies … but we’ve just embraced and made it up. It’s all thanks to you.”

Novelists tend to make good biographers, not least because they know how to shape a story, and it is no mean feat to boil Dostoevsky’s epic life down to 256 pulse-thumping pages. Dostoyevsky in Love is beautifully crafted and realized, but it is the great love that Christofi feels for his subject that makes this such a moving book. ~

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/jan/14/dostoevsky-in-love-by-alex-christofi-review-unpredictable-dangerous-and-thrilling

Oriana:

It’s worth noting that Dostoyevsky’s second marriage was a success. In her memoirs, Anna wrote, “My husband was passionately in love with me.” She stressed that she wasn’t particularly beautiful or intellectually brilliant. As I remember, she appreciated how much both of them respected each other’s independent personalities — today we’d say that they gave each other “space.”

And yes, the story of how Dostoyevsky proposed is both charming and amazing. I’ll reveal only one clue: since Anna worked as his stenographer, he asked her if, in her opinion, it would be realistic if a character in his novel proposed to a younger woman — how would this woman react?

So, amid stories of how writers are monsters in their private lives, we have the counter example of Dostoyevsky, who in his second marriage was a loving husband and father.

Pope Francis quotes Dostoyevsky:

Mary:

Christofi's project of a biography informed by Dostoyevsky's novels seems like an excellent idea. Dostoyevsky poured his life experiences into his novels again and again...the near execution, the experiences of epileptic seizures, the wild passionate loves and rejections, the intellectual and emotional tensions that can seem wild, even frenzied; the struggles with the problems of evil and faith...all realized in his characters : Ivan Karamazov, Prince Myshkin, Raskolnikov, the Underground man, and all the rest, like personifications of a fragmented, turbulent, suffering, contradictory and struggling self.

There is the sense always of his unflinching honesty in revealing, recording and exploring even the most painful and demanding questions...always clothed in the flesh of his characters and their desperation. Ideas and arguments are not discussed, but lived in his novels, not as abstractions but as existential and living in the world. Yes, nothing more Dostoyevskian than Dostoyevsky's own life.

Reading this, you can't help but breathe a sigh of relief at his comforting second marriage, and can understand his early death...he had to have been utterly used up and exhausted by both his life and his art, having done everything at the very height of intensity. So much of his experience was extreme, from prison, Siberia, the almost execution, through poverty, ill health, and many disappointments in love and in work. And yet, he had that belief in redemptive love...also embodied in his stories and characters: Alyosha, Mishkin, and even Raskolnikov's consumptive prostitute.

*

HOW MODERN RUSSIANS FEEL ABOUT THE MURDER OF THE ROMANOVS

~ There are three main groups of people.

One, mostly young people, don’t feel anything — it’s abstract history for them.

Another follow the Soviet narrative: Nicholas II was evil and weak and deserved killing with his family.

And the third one likes the Tsar and feels that his murder with the family was a horrible crime.

I think the attitude depends on the general idea about the Soviet Union. If a person likes USSR (great industries, a fair state, won the war, launched man into space) they tend to ignore Soviet atrocities, and they need to argue that Russian Empire was so bad that it deserved destruction.

If a person feels that USSR was a bad place, it’s easier to see all the negative sides of it, and understand that you can’t found a good state on murdering people without a trial, with their families.

Personally I think that murder had set a certain value set for the new country. Human rights were cancelled now. The new power had allowed itself to kill those people it didn’t like, with no trial and no laws — and lie about it to the public. After the Tsar, it was done to millions and millions of people, causing unimaginable suffering and damaging the society for hundreds years to come. This was a return to the Middle Ages, and we are still struggling to get out of there. ~ Valentin F, Quora

*

PUTIN, POISON, AND STATE TERROR

[This article was written before the current Russo-Ukrainian war]

A geologist by training, Sergei Lebedev’s fiction excavates the inner lives of earlier generations, buried under layers of official myth and self-deceit

The Russian novelist Sergei Lebedev is currently based in Berlin. But it is the popular uprising in Moscow that hangs darkly over our conversation. Hours before we speak, protesters calling for the release of the jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny take to the streets in towns and cities right across Russia. The Kremlin’s response is a familiar one: thuggish violence.

The TV images make a Mordor-like tableau. Faceless riot police clash their shields together in a rhythmic display of power; demonstrators raise their arms in a plucky counter-clap. There are arrests, many thousands of them. Young men are savagely beaten and dragged through grey slush into waiting police vans. One sets himself alight in an apparent act of rebellion.

After 20 years of repressive rule by Vladimir Putin, and his fellow KGB alumni, discontent is boiling over in Russia. But to what end? Lebedev is optimistic about political change, of a civic thaw after a long winter. “Putin is no Gorby. We are not in perestroika,” he admits. “But our grandparents and parents lived with the idea they would die in the USSR. Then all of a sudden, in two or three years, you are in an absolutely different reality. I think that could happen again.”

It is Russia’s dialectical past – shot through with collaborators and resisters, martyrs and monsters – that inspired Lebedev’s new novel Untraceable. That, and the dramatic events in Salisbury. In 2018 Lebedev was watching news reports of the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal. Two assassins from Moscow smeared the nerve agent novichok on the front door handle of Skripals' home.

Lebedev spotted an overlooked detail. Scientists invented novichok in the closed town of Shikhany, 600 miles south of Moscow, on the banks of the Volga. It was there, in the 1920s, that Soviet and Weimar republic German scientists secretly tested chemical weapons. The cooperation lasted until 1932. “I was fascinated by the dark romance between people of knowledge and people of power,” Lebedev explains.

In Untraceable Lebedev transforms Shikhany into “the Island”, a forbidden history-haunted place that is “everywhere and nowhere”. The novel’s main character, Professor Kalitin, is a talented Soviet youth. He invents “neophyte” – a neurotoxin that cannot be traced – in a special laboratory built within a former Orthodox church. An angel, half scrubbed out, watches him from above. When the USSR falls, Kalitin defects to the west, taking with him a vial of his own unique poison.

An undated photo of the gates surrounding the Shikhany research center near the town of Saratov, Russia

The novel begins with a quote from Faust and the Skripal-like murder of another Russian émigré in a Mitteleuropean restaurant. Kalitin’s hiding place in Germany is discovered and two killers are sent by Moscow to poison the professor with his own creation. Meanwhile, a German priest persecuted under communism wrestles with his own inner ghosts.

The Island, you gather, is the USSR. Its citizens are cut off from the outside world, impersonal elements in a giant, malign social experiment. One of the assassins, Shershnev is a “particle of state power”; Kalitin fails to confront the ethical choices of his scientific work and becomes a kind of human novichok. “His inner essence opens this door so he can work in this lab without any moral issues,” Lebedev says.

Untraceable is Lebedev’s fifth novel, out next month in the UK. He’s had a busy and prolific decade. The New York Review of Books calls him “arguably the best” of Russia’s younger generation of authors – he is 39 – and his work has won praise from Karl Ove Knausgaard and Svetlana Alexievich. For my part, I was captured by the velvet lyricism of his prose and his le Carré-ish plot. Lebedev calls his latest book a “political rather than a spy thriller”. There’s no espionage, he stresses, saying: “It’s something in between.”

One major theme in his fiction is the continuity between the old organs of repression during the 20th century and the new. Stalin regularly wiped out “enemies” at home and abroad. There was a justification of sorts: murders were necessary to defend a progressive state from capitalist wolves. Victims died in ingenious ways, with the killings on a spectrum from the secret to the splashy: silent poisons and cyanide spray-guns versus exploding cakes and ice picks [a reference to the murder of Trotsky].

The Leninist rationale for political murder has disappeared. But Putin has brought back old methods of intimidation and – in certain cases – what the KGB called “physical removal”. Dissidents and troublesome journalists have perished in murky ways. And poison has once again become an exotic instrument of state terror, as evidenced by the Skripal case and the radioactive teapot murder in 2006 of Alexander Litvinenko in London.

Lebedev’s attitude towards these crimes is “deeply personal”, he says. “Between 1917 and 1991 state security wrote my family’s story. We lost about 20 people.” His relatives were targets for Bolshevik persecution. They included Orthodox priests from St. Petersburg, provincial nobles from Kaluga and Vladimir, and the descendants of Germans who emigrated to Russia in the 19th century.

After the Berlin wall fell, Lebedev’s grandmother took him to visit Moscow’s German cemetery. She revealed the family’s hidden backstory: they had German ancestors, a connection that spelled doom during the Stalin period. The episode features in Lebedev’s novel The Goose Fritz, in which a young historian seeks out clues to his roots. A geologist by training, Lebedev’s fiction excavates what lies beneath: the inner lives of earlier generations, buried under layers of official myth and self-deceit.

Lebedev’s personal history features perpetrators too.His grandmother’s second husband was a colonel in the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police. A family friend lived an outwardly non-Soviet life, independent and free-thinking. His job was to devise bioweapons. Lebedev says his books explore these “contradictory moral shapes”, the strange dualism that allows loving fathers to serve tyranny by day and to tuck their children up at night.

One of the Salisbury poisoners, Anatoliy Chepiga, is a father with a young family. In Untraceable the fictional hit-man Shershnev has a difficult relationship with his son Maxim. Lebedev says the liberal Russian media treated Chepiga and his military intelligence colleague Alexander Mishkin as a comedy duo. “It wasn’t funny at all. They did their jobs. I take them seriously,” he observes.

The Kremlin, naturally enough, denies it has anything to do with Novichok. This, Lebedev thinks, is part of a wider failure by post-Soviet Russians to admit their misdeeds. After a period out in the cold in the early 1990s, Putin and his KGB friends came back. They carried out a counter-revolution against Russian democracy. Once in power they got rich. Habits of secrecy and conspiratorial thinking returned. Foreign policy became stridently anti-western and xenophobic.

The charge sheet against Putin and his cronies goes beyond rampant personal corruption, showcased by Navalny in his recent video of the president’s secret palace on the Black Sea coast, now watched more than 100m times. The regime’s greatest sins have taken place over the past two decades in Chechnya and in invaded Ukraine, Lebedev suggests. The Russian opposition has largely ignored these war crimes, he says, in which thousands have died.

“An important person is missing from our historical record. It’s the figure of the evil-doer,” Lebedev adds. “Russians don’t want to talk about responsibility for these murders. In the 30 years since Russia became an independent state our law enforcement agencies have committed lots of crimes that can’t be attributed to the Soviet period. Where is the source of this evil? I’m interested in who did this, and why.”

As part of his research, Lebedev went through the archives of the Stasi, East Germany’s surveillance-fixated spy agency. There was plenty of material in the files that demonstrated what Lebedev calls the “creativity of evil”. In Untraceable, the authorities persecute the charismatic GDR pastor by sending him goods he hasn’t ordered: women’s clothes, mannequins, coffins, tins of condensed milk. “Torture through abundance,” the priest discovers.

Putin spent the late cold war as a junior KGB officer in the city of Dresden. The Soviet Union and its East German counterpart both carried out clandestine operations in the 1970s and 1980s but also tried to observe legal technicalities, Lebedev says. These days, he argues, the Putin regime behaves with shameless impunity. “The new evil is rooted in the old evil,” he suggests, adding that Russia is now part of a modern tyrants’ club, with Saudi Arabia and North Korea.

Lebedev hasn’t visited Britain but is a fan of English literature: in 1979 his geologist father traveled to London as part of a Soviet delegation. Dad came back with a suitcase full of Agatha Christies and other detective novels. Growing up, Lebedev immersed himself in an eight-volume translation of Sherlock Holmes. There’s a simplicity about Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories, he thinks – and a “philosophical aspect”. “For me, Holmes embodies the idea of justice. Morality is based on the fact that every crime has its trace,” he says.

As a professional geologist Lebedev roamed around Russia, visiting the far north, with its reindeer herders and frozen tundra, as well as Kazakhstan. He spent 14 years working as a journalist in Moscow on an education newspaper, ending up as its deputy editor in chief. Since 2014 he has written full time, poems and novels. The Kremlin has “mostly ignored” him, he says, despite his growing international reputation.

I ask Lebedev about the state of modern letters in his homeland. He is unimpressed. In the 19th and 20th centuries Russian authors engaged with the great issues of the day. During the Putin era, he says, the intelligentsia has largely shut its eyes to the “reality of what’s going on”: that the country is rapidly turning into a full-blown autocracy. “Consciously or sub-consciously, people are trying to avoid some harsh and important questions,” he thinks.

By way of example, he mentions a list of the 100 best Russian books of the 21st century, compiled by the Moscow literary journal Polka. “There was only one book on the war in Chechnya and nothing from the writings of Anna Politkovskaya,” Lebedev complains. “For me Russian literature at the moment consists of non-written books. I can clearly see the gaps. Writers have a moral and creative responsibility to reflect reality”.

Lebedev finished Untraceable before a group of secret operatives poisoned Navalny last summer in Siberia. The undercover hit squad worked for the FSB, the spy agency that Putin ran before he became PM and president-for-life. According to a confession from one of the team, the assassins applied Novichok to the inner seams of Navalny’s blue underpants. He collapsed on a flight to Moscow. Navalny survived only because a quick-thinking pilot made an emergency landing in Omsk.

Lebedev says there is something “supernatural” in the way Navalny’s case coincides with the release of his latest book. Last week a court jailed the opposition leader for two years and eight months. He’s now in a penal colony. The fate of Putin’s most prominent critic is grimly uncertain; you suspect further vengeance awaits. What will happen? “He will be kept in captivity as a hostage,” Lebedev predicts. He adds: “I don’t know what is possible. I can only wish him stamina, health and resilience.” ~

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/feb/13/in-russia-the-new-evil-is-rooted-in-the-old-evil-novelist-sergei-lebedev-on-putin-poison-and-state-terror

In a court hearing, Navalny called Putin "a naked thieving king."

*

MOSCOW AS A SPECIAL PLACE UNDER “REAL SOCIALISM”

~ Communism as a society of equality, opulence and permanent justice was something in an indefinite future. No one seemed to believe we would see it any time soon. Which is why we were making the best out of Real Socialism, the transitional phase between the “full and finite victory of Socialism” that happened in the 1960s, and Communism.

For making the best out of the imperfect Real Socialism, Moscow was the sweetest of spots on the map.

Double track

From the dawn of Soviet rule, we practiced a double-track approach for managing things in the USSR.

The vanguard thinking of the Bolsheviks dictated that we needed a few oases of magnificence and perfection: the Moscow Metro, the Kremlin, the Bolshoi ballet, the national ice hockey team, the space program, the chess masters. These would inspire awe and envy across the globe, showing the superiority of Marxism-Leninism no bourgeois country could possibly match.

In order to create and maintain them, resources were taken from the rest of the country. Apart from cities with military production and critical infrastructure, the provinces had to make do on the basis of “temporary solutions”. To put it simple, the building of Communism consisted of expanding the “oases” into the territory of “temporary solutions”. The more the provinces became like Moscow, the closer we were getting to Communism.

Why wait for paradise?

A whole lot of people didn’t want to wait for the green sprouts of better life to shoot up in their provinces. They tried to find a way to join the few, the proud, the selected who like me had the privilege of living in Moscow. The most determined succeeded. During my time in the USSR, the population count in the city doubled from 5 to 10 million. [Now it's close to 12 million.]

Apart from a handful of anti-Soviet dissidents, these millions were fully aware of the epic luck they enjoyed being Moscovites. Despite all the rants in the kitchens and dachas (“country cottages”) to the trusted friends and family about the gray drudgery of Soviet life, they were generally loyal Soviet citizens. Like me, many looked forward to a bright career in the service of the Communist state and wanted to earn their stripes more than anything else.

If not for a circle of ambitious modernizers under the tutelage of the KGB boss Andropov, the USSR could have survived until today. We lost the Cold War and abandoned the Communist project not because of popular uprising in Moscow. The city remained the bastion of Soviet rule all the way until the Communist leadership fractured at the very top and turned on itself in August 1991.

*

Despite the ubiquitous “dissident talk”, before the 1990s Moscovites generally acted as loyal Soviet citizens. Good credentials of Communist dedication were a requirement for a smooth career within the State. Incidence of ideological vacillation was duly captured and registered in personal files few of us had a hope to ever look into. In the provinces, especially along the ethnic rim, people had more leeway. But in Moscow, even freethinkers tried to make sure their personal views wouldn’t get in the way of growing in the ranks.

Below, a young woman celebrates 60 years of Komsomol (“The Communist Union of Youth”) in the Red Square. On the celebratory ribbon across her upper body, the text says “The Best at the Production Line”. The banner in the background says “Proletarians of all countries, unite!”. The colleagues behind her check out if the luminaries at the spectator stands beside the Lenin Mausoleum see the degree of their dedication. ~ Dima Vorobiev, Quora

John Jozsa:

Yes, Moscow was kept to be the “show-window” of Communism. Citizens’ movement to go and settle in Moscow was VERY controlled and limited. Only with assignment by the party and government’s special permission was it possible. Yet Moscow’s population nonetheless has doubled. Now even tripled.

Igor Skryabin:

Moscow was privileged, but so were Baltic republics. In the 80s Moscow was perhaps the most anti-communist part of the USSR. Quite often people on the periphery of the USSR were more ideologically hard-line true believers than in the center. It all started in Petrograd, 1917 but ended in Moscow in 1991.

Dima Vorobiev:

“In the 80s Moscow was perhaps the most anti-communist part of the USSR.” Not before being publicly anti-Communist became relatively safe in 1989.

The three days of the August coup were dangerous. But in 1991 the entire country turned anti-Soviet. Moscow was no outlier here.

Attempted coup against Gorbachev

*

MISHA IOSSEL ON THE DRONE ATTACKS IN MOSCOW

The recent (May 30) massive drone attack on the outskirts and suburbs of Moscow, pointedly targeting Putin's residence and the luxurious mansions of his coterie of billionaire friends, sends the latter a clear message: “Hey, Russia's ‘elites' — the clock is ticking. Keep waiting, keep procrastinating, keep doing nothing about that crazy bastard Putin of yours — and we're afraid (not afraid) things might start going really badly for you.”

Oriana:

This war, itself a terrible surprise, almost consists of surprises — drones over the luxury suburbs in Moscow, the evacuation of civilians in Belgorod . . . At least some of it seems to be the work of the anti-Putin resistance that wants freedom for Russia. The only certainty: there will be more surprises.

Mary:

The history we are now witnessing has been full of surprises, and I feel that more will be coming...maybe even things we thought not possible...as not possible as a stand up comic becoming a heroic leader in a war against an invading power, as not possible as the supposed military might of a great power revealed as a paper tiger, woefully inadequate, unprofessional, and lacking in even the basics of arming and supplying its forces. These kind of surprises...I look eagerly forward to...even greater changes may be coming.

Oriana:

And think how bizarre it is: Prigozhin, an ex-con, leading a private mercenary army that calls itself an "orchestra; Prigozhin, in his videos, screaming in vulgar language about the incompetence of the Russian leadership and the lack of ammunition; Putin, a closeted gay man, carrying on about "traditional family values"; Putin's paranoia about his life (though he has good reason to be paranoid); and yes, Zelensky as a stand-up comic turned hero; the whole weirdness of this out-of-time colonial war. Who would have ever imagined? Another example of how reality outdoes art . . . for one thing, if war didn't happen to be a tragedy, this particular war would be an astonishing black comedy.

*

“The Kremlin often claimed it had the second strongest military in the world — and many believed it. Today, many see Russia's military as the second strongest in Ukraine.” ~ US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken in Helsinki, 6-2-23

*

CAN RUSSIA EVER BECOME A DEMOCRACY?

~ Putin’s war against the West is a war against liberal democratic values.

Putin calls the invasion of Ukraine a special military operation because he thinks that it's only one battle in a greater war.

In preparation for the showdown against the democratic world, military training has been extended from cadet schools to regular schools. Indoctrination now starts at kindergarten. The next generation of Z soldiers should be of age by the early to mid-2030s.

That will be part of Putin's legacy. A legacy intended to ensure that Russia will not become a democracy in our lifetime.

Russia, as we know it, will never be democratic.

A democratic Russia would be so different that it would hardly be recognizable. It would be a Russia without an FSB, KGB, or NKVD type organization repressing people.

It would be a low corruption, high trust society instead of being paranoid, vindictive, and corrupt to the core.

I don't want to say that democracy in Russia is impossible, but it would require something completely unexpected to happen because all the trends I'm seeing are pointing to the other direction — tyranny. ~ Henriikka Keskinen, Quora

*

There were states in history that had mafia, but I think Russia is the only state owned by the mafia.

Mafia

stole Russia from Russians; stole freedom of speech and freedom of

knowing, replaced it by hateful propaganda, and hired enforcers to keep

people subdued and in the dark. ~ Elena Gold

THE IDEOLOGY OF PUTINIST RUSSIA

According to President Putin, the national idea of Russia is patriotism.

Historically, “patriotism” in our country has always been government-endorsed nationalism. President Putin calls other versions of nationalism kvasnóy.

Kvas is an essential peasant drink made of fermented old bread. In other words, non-government versions of Russian nationalism are uneducated and primitive, at best. In order to avoid it, we need to look to the government for the latest update on what’s best for the nation.

Because, in the words of President Putin, true patriots are those who work for the “development of the country.” And no one knows what kind of development we need better than whoever holds the Kremlin.

However, many around the Presidential Administration feel this definition is too general. For example, if two members of the government disagree on how best to win the Ukraine war, how to decide which of them is more patriotic?

Also, President Putin is now 70+. More and more movers and shakers around him silently wonder what’s patriotic when our President’s superior opinion on the matter is no longer available?

Attempts are being made to build a kind of coherent ideology on the nugget of Putin’s wisdom.

Russian paratroopers in 2021; Russia has lost half of its elite paratroopers in 2022

One of the latest and most articulated attempts to eliminate the “non-ideological” 13th clause of our Constitution was made by a group commissioned by the leading “liberal” Putinist Mr. Kiriyenko. He takes care of Russia’s political parties on behalf of the President. His men called the proposed ideology “Pentabasis.”

This Pentabasis consists of five parts:

“Patriotism” for everyone, everywhere, at all times.

“Trust in societal institutions”. In practical terms, all political activity shall happen inside the corporatist structure of our state and the associations, unions, and parties it has allowed.

“Accord.” De-confliction, no adversarial critique of the system, political competition only between loyalists and only between individuals and approved political platforms.

“Traditions.” No liberal nonsense when noisy minorities are allowed to set the agenda, get funding, and promote their interests. Hierarchical power structures. Perpetuation of our millennial-old political tradition with top-heavy, Moskva-centric bureaucratic organization of all aspects of the society.

“Creation” as the cornerstone of individual lifestyles. This is a counterweight to Western consumerism and Eastern absorption in inward-looking, meditative self-improvement that excludes individuals from our State’s edifying guidance.

Below, a painting by Cossack artist Andrey Lyakh. It visually expresses the spirit and letter of Russian Pancha Shila [a Buddhist term for the five main principles]

What you see is the epic colonization of the vast Russian provinces (“creation”). Several historical periods meet each other, from medieval battles to the 21st-century petroleum extraction beyond the Urals (“traditions”). People of all kinds of professions, ages, and ethnicities interact and work together (“accord”). The oversized owl to the left as well as the monastery domes to the right, bless the scene that is suffused with harmony, cooperation, and the “trust for societal institutions.”

For a Russian seeing this, it’s obvious that nothing of it would have been possible without the assured hand of our Derzháva (“the mighty State”). Without the State and our patriotic dedication to whatever it does, who knows what could have happened to us? ~ Dima Vorobiev, Quora

Orlin Stoyanov:

Its interesting because in some other countries patriotism implies being against the government. Especially countries which have to free themselves of some yoke every 100 years.

*

MISHA FIRER ON THE “Z” IDEOLOGY

“‘The city has become a giant cemetery,’ say residents of Mariupol.

The port has emptied out. The populace of a bustling, industrial, rich city is condemned to a slow extinction.

The closer battles are getting to Mariupol, the more fierce and ferocious Germans become, the more they lash out their rage upon the innocent people.

Numerous public and residential houses have been burned down and blown up.”

Izvestiya 11/09/1943

Deja vu, anyone?

Nazis in Mariupol, 1943

In May 2022, this same bustling industrial city was reduced to ruins by a semi-Swastika bearing army of aggressors.

They are driven by an evil [z stands for zlo, evil in Slavic languages] ideology of the national superiority and Lebensraum (via Germanophile philosopher Alexander Dugin): annexation of new lands whose natives must be forcefully removed and re-populated with the superior race.

On May 9 that marks the defeat of the Nazi Germany by the Soviet Union, Rushists will stage a military parade in defeated Mariupol. [PS: the parade was called off shortly before May 9]

Half-swastika bearing military hardware will trundle along the main city thoroughfare, which is now being cleaned out of rubble and corpses of the civilians.

In their primitive rendition of German Nazism, the Rushist state has turned to antisemitism to incite hatred and unite the populace around a common enemy within.

On May 2nd, minister of foreign affairs Lavrov said that Hitler was a Jew.

Next day, ministry of foreign affairs announced that Israel supports Nazis in Ukraine.

And on May 4th, Kremlin invited a delegation of the anti-Israel terrorist organization Hamas.

Lavrov’s three grandchildren are Israeli citizens, like his son in law, all of whose family are registered in Natanya, Israel, not in Moscow.

Will Lavrov denounce his family too when it becomes politically expedient?

Rushist [“Russian” + “fascist”] propagandists have finally hit the nail on the head. They found a true symbol of Putin’s Russia.

A poor decrepit babushka whose husband died long ago from alcoholism, wears old mismatched clothes, because she spends all of her meager pensions on utility bill and expired supermarket food, grips a flag of the Soviet Union, a country that doesn’t exist anymore.

A made in China no-brand track suit and a pair of worn out felt boots is all she got to her name.

She’s a perfect symbol of a country that has no future. [The word behind her, pobyeda, means "victory."]

A patriotic man took a photo next to a mural of the Soviet flag-waving babushka whose painted house looks way better than the two-story hovel of the residents who live next to it.

Putin has reached the pinnacle of what no other thief has ever managed to accomplish: he stole the future from 144 million people while attempting to steal a neighboring country. ~ Misha Firer, Quora

[144 million stands for the population of Russia — though given the prevalence of lying, the true number may be smaller; the war is definitely not improving the demographics.]

Rob Stuart:

This post by Misha is a starkly accurate portrayal of the excruciating tragedy that is the fascist-imperialist kleptocracy over which the narcissistic Machiavellian psychopath Vladolf Putler presides like a malignant metastasized tumor in the head of a dying bear that, hopefully, will soon be a rotting carcass to be devoured by maggots.

Mika Timonen:

I thought Putin's ideology was kleptocracy: stealing from the people while letting them think he was a nationalist.

Dima Vorobiev:

Patriotism in Russia is a government-endorsed nationalism. Everything that strengthens our mighty State (Derzháva) is good. Everything that weakens it is bad. Delving too deeply into the topic (e.g. what should citizens do if the State starts incarcerating and killing them) is risky and divisive—therefore discussions about external enemies are encouraged instead. Ukrainian Nazis, thankless Poles and Balts, Muslim-loving and gay-embracing European liberals, Anglo-Saxon plutocrats, Washington hawks, what have you, new suggestions are welcome.

The national idea of Russia has invariably been power. The Russian state, ever since the time of Czars, has always tried to shape it into a narrative of unselfish service to the current top ruler.

It started with Rurikid rulers in Muscovy, with their “Moscow is the Third Rome”.

Continued with “Monarchy, Orthodoxy, Nativism (Naródnost)” in the XIX century’s Romanovs Empire.

Culminated in the totalitarian ideology of everyone serving the global Communist project led by the Soviet Communist party.

The collapse of the USSR and secession of our colonies and dependencies in 1991 provoked a deep ideological crisis. The void felt so bottomless that President Yeltsin even summoned a special commission tasked with finding a new national idea. It took Putin’s rule and his total control over the country’s political landscape and mass media to re-establish the traditional Russian narrative of everyone serving the top ruler in the Kremlin.

Right now, our national ideology is called patriotism, which means government-endorsed nationalism. Nationalism that runs counter to the Kremlin’s policy is considered extremism, if it’s not an outright collusion with foreign players.

Putin considers it every Russian’s “sacred duty” to be patriotic. Non-patriotism is viewed as a sad consequence of negligence in one’s upbringing, a deep moral flaw, or an evil influence of Russophobe (Russia-hating) forces. There are either overt agents of foreign influence, or fifth-columnists, i.e. people who declare their loyalty to the government, but secretly crave Russia’s demise and subjugation to outside players. (Liberals, environmentalists, LGBT activists and human rights defenders are the known examples of fifth-columnists.)

Impeccable patriotism in Russia is demonstrated by:

1. Undivided loyalty to President Putin

2. Veneration of the USSR as the ultimate victor in WW2

3. Public condemnation of liberal democracy, globalism and Nazism/Fascism as ugly exports from the decadent West

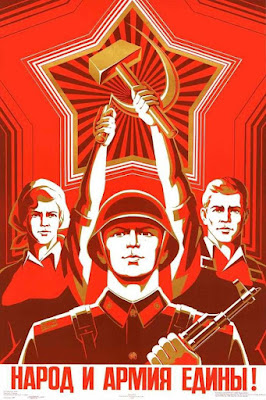

The Soviet poster below from the 1970s is called “The nation and the military are one!” It demonstrates the inspired might of Communist ideology in a solid military-industrial armor. If you substitute the man’s and woman’s workshop clothes with modern office attires, and the proletarian hammer and sickle with an oil rig and a gas pipeline, this poster can be instantly recycled for glorifying the patriotism of Putinist era. ~ Dima Vorobiev, Quora

Oriana:

For me the moment of real enlightenment was being reminded that “z” is the first letter of the pan-Slavic (I think) word for evil — zlo.

Now, there is no coherent explanation for why Russia adopted the letter “z” to as its national logo in this war. It would make more sense if Ukraine had adopted it — Z for Zelensky, or for “Zapad” — the West.

In the absence of a coherent explanation, I stay with my own Quora-induced “aha” moment: Z for zlo, meaning evil.

I realize that this makes little sense on the conscious level, but once in a while history turns strange indeed.

On the other hand, one could argue (but only in hindsight) that the history of Russia was actually predictable, starting with Ivan Grozny (translated as Ivan the Terrible, but a more accurate translation would be Ivan the Terrifying). Yes, ultimately it’s a terrifying history.

“But never forget that the first and greatest victim have been the Russian people,” I remember reading or hearing somewhere. I have not forgotten. I don’t hate Russia. But I feel sad — not just about Russia, but for all of humanity.

*

WHY SOCIETIES HAVE BECOME MORE LIBERAL OVER TIME

~ That’s only true of western societies (and some in other parts heavily influenced by the west) and if you go to certain places you’ll find that liberalism is not tolerated.

It’s because we have largely eradicated real problems. Western societies tend to have a lot of relatively rich people in them; if you live in Western Europe, North America, Japan, or South Korea there is a very good chance that you are in the top five per cent richest in the world, whatever it might feel like.

Where you’ve got no real problems you can relax a bit. It’s not a daily struggle to survive any more, more a pleasant cruise through life, and that’s really no good for talking fauna as it needs something to occupy its highly evolved brain with. So it invents all sorts of problems which, to a man or woman living in some of the properly poverty-ridden places I’ve seen in the past, would be about No. 10,623 on their list of worries. In these poor places you execute criminals, because theft of anything is denying resources to the rest of the community, and you jealously guard your crops, livestock, and water, because if you don’t you’ll starve and thirst.

It’s easy to be liberal when you’re rich and in the midst of plenty. When bounty is not so magnanimous, you’ll find that people tend to take harder attitudes to life.

This is what Guardian readers fail to understand. You can vote Remain when you have a protected job and there’s so much bacon on the table that you can afford to buy an Audi too. But when you are on a low wage with no job security and the bacon gets a bit lesser whilst you’re struggling to run your twenty-year old Hyundai, or you have no Hyundai at all, then attitudes get a bit less liberal and you vote Leave.

The bacon-on-the-table theory of political economics isn’t one that’s en vogue on sociology courses. But it is in fact the only one that fits all available observations. Strange that. Must be those high levels of education we keep hearing about. Educated out of their senses, shouldn’t wonder.

I blame the EU. Ursula where’s me Bacon. ~ Ian Lang, Quora

*

WHERE HAVE ALL THE HIPPIES GONE?

~ Conservativism is based on fear, Liberalism is based on curiosity. See Biology and political orientation - Wikipedia. Conservatives tend to have bigger amygdala, Liberals tend to have bigger anterior cingulate cortex. Note that both fear and curiosity are definitely necessary emotions: fear avoids you getting killed while curiosity enables you to evolve.

The more threatening the milieu is — high crime, violence, diseases, external enemies, state terror, low respect of laws, Patriarchalism or broken families, unstable economy, oppression, highly volatile society, dangerous animals, extreme weather phenomena — the more the milieu favors Conservativism. Military must be the utmost example as soldiers face death by default.

Shown to perform a primary role in the processing of memory, decision making, and emotional responses (including fear, anxiety, and aggression), the amygdalae are considered part of the limbic system. Such milieu where fear and terror are the primary emotions, favors conservatism. It is the flip side of the American concept of “freedom” of which they are so proud, but also the Russian — the Russians tend to be utterly conservative.

Conversely, a milieu where there are a lot of opportunities and few external and internal threats, the more prevalent Liberalism is. Such milieu enhances the anterior cingulate cortex, risk taking, curiosity, innovativeness, empathy, tolerance, free will and emotions. Societies which are justice states, where Gini index is low, which are peaceful, where rule of law prevails and where there is low crime and state is experienced as common property and not as enemy or oppressor, tend to favour Liberalism. The European concept of “freedom” promotes liberalism.

The good thing on Liberalism is that it provides a greater degree of freedom than Conservativism and cultural evolution is faster and more profound in such societies. You might say Liberalism is the accelerator pedal of the society while Conservativism is the brake pedal. Conversely, being Conservative is about avoiding reckless risk-taking which may prove disastrous. Both accelerator and brake are needed to control the society.

There was once a question in Quora: where have all the Hippies gone? The answer is that the Hippies won and we are all Hippies now. The value set which they represented proved more successful in the cultural evolution than the rivals.

But not all chances are for good. Novelties like Fascism, Communism, Social Darwinism, Eugenics etc were most strongly opposed by Conservatives — and their radar was right: those were dangerous things. They sensed danger where the Liberals didn’t. This is why we need Conservatives too — not to return back to the bad old days, but to warn of the stray paths which may lead into a disaster. ~ Susanna Viljanen. Quora

HOW RELATIONSHIPS BREAK DOWN — AND THE SCOURGE OF THE SMARTPHONE

~ I’ve been doing couples and family therapy for over twenty-five years. I like it more than individual counseling because you see the interplay and dynamic between people. My clients mainly fall into two buckets: couples with kids under five and couples whose youngest child has just left home.

The biggest change I’ve seen in relationships is the damn smartphone: texting, internet, instant communication. Smartphones have caused more upheaval than anything I’ve seen in my career. We’ve normalized them being intrusive and taking precedence when people are lying in bed, playing Wordle or scrolling through TikTok rather than talking to each other. And we’ve gotten used to communication being instantaneous when a healthy relationship requires you to slow down and listen to each other. But our lives don’t really allow for that; especially if you have young children, it’s often go, go, go.

When the COVID-19 pandemic started, I saw an immediate plummet in the demand for counseling as many people went into survival mode. A lot of people can go into emergency mode and do well with one another. But as time went on, people realized the pandemic was going to last much longer. What I saw was a pressure cooker. Many existing issues were in stasis as people hunkered down, and meanwhile, more things were being stuffed into the pot. This put more pressure on families. Two years into the pandemic, something shifted. That’s when I was getting inundated with people who were in crisis and on the brink of divorce.

In the next few years, I think, we’ll see the aftershock of the pandemic on couples. I think it’ll be coming in the next year or two, maybe three, especially for couples with younger kids who lost time in school, or people who lost their jobs or had to start new careers. Will the stress levels just keep going up with these couples until they break?

The lid of the pressure cooker is still too tight. Many of us have gotten used to new levels of stress, and it’s had an enormous impact on couples. In this pandemic era, couples have to reconsider the balance of power: Who’s working? Who’s the primary parent? And that’s coming with a lot of renegotiations.

At the start of the pandemic, I saw people fall into old gender-role stereotypes without even talking about it—women giving up their careers to stay home with the kids even though they made more money than their husbands. Instead of saying we’re returning to normal, start asking, “What are we creating that’s going to work and be healthy for couples, families, and kids?”

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that the pandemic has shone a light on mental health awareness. Especially for younger generations, it seems to be much more normalized to go to therapy. And as these people grow up, they’ll likely have much healthier relationships because of it.

While there’s greater awareness of mental health issues, there’s still a lot of confusion about what it means to treat them. People will often say, “Just go see a therapist.” But that’s like saying, “Just go see a doctor.” Do you need knee surgery or do you have cancer? Do you need an expert in depression or in couples therapy? You need someone who is specialized. And when the house is already on fire, the only thing a therapist can do is get out the fire extinguisher.

I can’t do any deep transformative work when the fire is raging. We need preventive care. If people come in when something is starting to be an issue between them instead of when they’re at a breaking point, I’d love that. Because then, in two or three sessions, you can be good to go—see you later! ~ Andrew Sofin

https://thewalrus.ca/what-breaks-up-couples/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

*

WHY WOMEN INITIATE DIVORCE

~ There are a few big reasons why 70% of divorces in the United States among heterosexual couples are filed by women. Women have more economic opportunities than in decades past and are better positioned to care for themselves and their children without a husband’s income.

Another big reason is that even though the world has become much more egalitarian than in the past, women still bear the brunt of most of the emotional labor in the home. Gilza Fort-Martinez, a Florida, US-based licensed couples’ therapist, told the BBC that men are socialized to have lower emotional intelligence than women, leaving their wives to do most of the emotional labor.

Secondly, studies show that women still do most of the domestic work in the home, so many are pulling double duty for their households.

A TikTokker with two children (@thesoontobeexwife) shared why she decided to leave her husband of two decades and her story recounts a common theme: She did all the work and her husband did little but complain.

The video, entitled “Why women leave,” has received over 2 million views.

“So for the men out there who watch this, which frankly I kind of hope there aren’t any, you have an idea maybe what not to do,” she starts the video. “Yesterday, I go to work all day, go pick up one kid from school, go grocery shopping, go pick up the other kid from school, come home. Kids need a snack – make the snack. Kids want to play outside – we play outside.”

Her husband then comes home after attending a volunteer program, which she didn’t want him to join, and the self-centeredness begins. “So he gets home, he eats the entire carton of blueberries I just purchased for the children’s lunch and asks me what’s for dinner. I tell him I don’t know because the kids had a late snack and they’re not hungry yet,” she says in the video.

She then explains how the last time he cooked, which was a rare event, he nearly punched a hole in the wall because he forgot an ingredient. Their previous home had multiple holes in the walls. Dr. Gail Saltz, a psychiatrist and host of the Power of Different podcast, says that when THEY punch walls it’s a sign that they haven’t “learned to deal with anger in a reasonable way.”

“Anyway, finally one kid is hungry,” the TikTokker continues. “So I offered to make pancakes because they’re quick and easy and it’s late. He sees the pancake batter and sees that there’s wheat flour in it and starts complaining. Says he won’t eat them. Now I am a grown adult making pancakes for my children who I am trying to feed nutritionally balanced meals. So yes, there’s wheat flour in the pancake mix.”

Then her husband says he’s not doing the dishes because he didn’t eat any pancakes. “Friends, the only thing this man does around this house is dishes occasionally. If I cook, he usually does the dishes. I cook most nights. But here’s the thing. That’s all he does. I do everything else. Everything. Everything.”

She then listed all of the household duties she handles.

“I cook, I clean the bathrooms, I make the lunches, I make the breakfasts, I mow the lawn, I do kids’ bedtime. I literally do everything and he does dishes once a day, maybe,” she says.

The video received over 8700 comments and most of them were words of support for the TikTokker who would go on to file for divorce from her husband.

“The number of women I’ve heard say that their male partners are only teaching how to be completely independent of them, there’s going to be so many lonely men out there," Gwen wrote. “I was married to someone just like this for over 35 years. You will be so happy when you get away from him,” BeckyButters wrote.

"The way you will no longer be walking on eggshells in your own home is an amazing feeling. You got this!" Barf Simpson added. ~

https://www.upworthy.com/why-women-leave-husbands?mc_cid=83f1174781&mc_eid=362fe951ca

*

If one of us should die, I shall move to Paris ~ Sigmund Freud, in a letter to his future wife

*LUCK IS IN THE MIND OF THE BEHOLDER

“Luck is believing you’re lucky.” ~ Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire

In 1995, a wounded 35-year-old woman named Anat Ben-Tov gave an interview from her hospital room in Tel Aviv. She had just survived her second bus bombing in less than a year. “I have no luck, or I have all the luck,” she told reporters. “I’m not sure which it is.”

The news story caught the eyes of Norwegian psychologist Karl Halvor Teigen, now an emeritus professor at the University of Oslo. He had been combing through newspapers to glean insights into what people consider lucky and unlucky. Over the following years, he and other psychologists, along with economists and statisticians, would come to understand that while people often think of luck as random chance or a supernatural force, it is better described as subjective interpretation.

“One might ask, do you consider yourself lucky because good things happen to you, or do good things happen to you because you consider yourself lucky?” says David J. Hand, author of The Improbability Principle, emeritus professor of mathematics and a senior research investigator at Imperial College, London.

Psychology studies have found that whether you identify yourself as lucky or unlucky, regardless of your actual lot in life, says a lot about your worldview, well-being, and even brain functions. It turns out that believing you are lucky is a kind of magical thinking—not magical in the sense of Lady Luck or leprechauns. A belief in luck can lead to a virtuous cycle of thought and action. Belief in good luck goes hand in hand with feelings of control, optimism, and low anxiety. If you believe you’re lucky and show up for a date feeling confident, relaxed, and positive, you’ll be more attractive to your date.

Feeling lucky can lead you to work harder and plan better. It can make you more attentive to the unexpected, allowing you to capitalize on opportunities that arise around you. In a study comparing people who consider themselves lucky or unlucky, psychologist Richard Wiseman of the University of Hertfordshire, author of the 2003 book The Luck Factor, asked subjects to count the pictures in a newspaper. But there was a twist: He put the solution on the second page of the newspaper. “The unlucky people tended to miss it and the lucky people tended to spot it,” he writes.

On the other hand, feeling unlucky could lead to a vicious cycle likely to generate unlucky outcomes. Psychologist John Maltby of the University of Leicester hypothesized that beliefs in being unlucky are associated with lower executive functioning—the ability to plan, organize, and attend to tasks or goals. In a 2013 study, he and colleagues found a link between a belief in being unlucky and lower executive function skills like switching between tasks and creative thinking. Then in 2015, he and other colleagues found more electrical activity related to lower executive function in the brains of 10 students who believed themselves very unlucky than in the brains of 10 students who believed themselves very lucky. “People who believe in bad luck didn’t necessarily engage in some of the processes that are needed to bring about positive outcomes,” Maltby says.

He offers a simple example of running out of ink in the middle of a print job. “The lucky person will have got a spare cartridge just in case because they have planned ahead. When the cartridge runs out they’ll say, ‘Oh, aren’t I lucky, I bought one earlier, that’’ fantastic,’ ” Maltby says. “However, the unlucky person won’t have planned ahead, won’t have done the cognitive processes, so when the printer cartridge runs out and they’re left with something to print, they go, ‘Oh, I’m so unlucky.’ ”

If this kind of vicious cycle takes hold, it can make a big difference. Economists Victoria Prowse and David Gill of Purdue University think responses to bad luck might even explain part of the gender gap seen in the workforce. In a lab experiment using a competitive game that involved both skill and luck, they found that women were more discouraged by bad luck than men. After experiencing bad luck, women had a greater tendency to reduce the amount of effort they put into the next round of the competition, even when the game’s stakes were small.

Luck frequently plays a role in careers, Prowse points out. Whether you get a job could depend on how much time a manager has to look at resumes, or whether she likes a color you wear to the interview. Companies often hold competitions that pit employees such as salespeople against each other. “Even a small reduction in the effort of a woman after one interaction, where she gets unlucky, could potentially mean you miss the opportunity of getting promoted and getting to the next level, which has all sorts of future repercussions,” she says. “It would be dangerous to dismiss these small differences as something that couldn’t potentially accumulate to something we really care about.”

While personality and gender seem to play a role, random events could also kick-start a virtuous lucky cycle or a vicious unlucky cycle. Economist Alan Kirman of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris realized this could be the case when he worked in an office with relatively few parking places nearby. One guy on his team always seemed to get lucky with parking spots close to the office, while another always had to park far away and walk. To figure out why, the team created a simple game-theory model to simulate the situation. It revealed that if would-be parkers happened to find spots near work early on, they continued to search in a narrow radius in the following days.

If they didn’t find spots near work early on, they began to search in a wider radius. Guess who had lucky streaks when it came to finding spots near work? The ones who were actually looking for them.

At least in the simulation, the parkers quickly sorted themselves into lucky and unlucky groups, without any reference to personality or gender, Kirman says. That means that a good or bad luck cycle could happen to anybody without their conscious knowledge. It also means that, to the extent that life is a zero-sum game like parking, our bad luck cycle could be facilitating someone else’s good luck cycle—and that’s maddening. “The unlucky guys learn to choose the spots far back and leave the spots for other spots for the guys who are ‘lucky,’ ” Kirman says.

Of course, believing in your own good luck isn’t always a good thing. In gambling, for example, lucky streaks are never what they seem. Take the case of online sports betting. Juemin Xu, a graduate student at University College London, and her advisor, experimental psychologist Nigel Harvey, analyzed a 2010 database of 565,915 sports bets made by 776 online gamblers. In all those bets, they found something apparently at odds with laws of probability: Bettors were more likely to win after winning.

Those lucky streaks weren’t supernatural, Xu says; they were generated by the “gambler’s fallacy”—the widespread but misguided notion that your luck must eventually change. Thinking that a loss was imminent after a run of wins, bettors would make safer and safer bets, generating an even longer run of wins. Unfortunately, the bettors didn’t make much money off of these streaks; over time, they still tended to lose to the house. “The best strategy in gambling is to control loss,” Xu says.

Teigen points out that, in many activities, lucky is the opposite of safe. In one study he found that people who have lucky stories are often those who have taken a lot of serious, often careless, risks. For example, a woefully inexperienced paraglider told him about having averted a crash. Ultimately, that approach to courting luck could backfire. “I am a little bit careful about wishing people good luck,” he says. “I’d rather they be safe than lucky.”

The trick, then, may be to find the areas of life where you can be both safe and lucky. In the early 2000s, Wiseman capped his long study of lucky people with the creation of what he called a “luck school,” in which he gave unlucky people exercises that taught them to spot chance opportunities, listen to their guts, take an optimistic view, and not dwell on mistakes—in other words, to do the things that lucky people do. He reported that, a month later, 80 percent of the unlucky people in his school said they were happier and luckier.

One of the easiest measures you can take to improve your luck is to shake things up. Think about the case of looking for parking. If you always default to the areas with merely tolerable spots, you’ll never find a really good spot. Similar types of routines can settle in at work, at home, or in your social life. To introduce variety, one of Wiseman’s subjects picked a color before going to a party and then introduced himself to all of the people wearing that color. Another frequently took different routes to work.

More difficult, perhaps, is to learn how to not dwell on bad luck. Studies have found that people who are victims of assaults and accidents tend to ruminate on questions like “Why me?” or “What did I do wrong?” This strategy is adaptive only if the victim can learn something that will help them avoid a similar disaster in the future. But that’s often not the case, and people are left with envy, self-blame, and useless, invasive thoughts.

However, certain kinds of unfortunate events—even very serious ones—seem to result in the mirror-opposite of this line of thinking. Teigen and his colleagues read interviews with 85 Norwegian tourists who took family vacations in Southeast Asia in the winter of 2004. When the devastating earthquake and tsunami hit, their and their children’s lives were at risk, their Christmas holidays ruined. Unlucky, right? Well, not from their perspective. Two years later, 95 percent of them said they had been lucky to survive, not unlucky to have picked that moment to travel there. (The remaining 5 percent said they had been a combination of lucky and unlucky.)

The key to deciding whether an event is lucky or unlucky is the comparison you make between the actual event and the “counterfactual” alternative you’re imagining, Teigen says. The people asking “Why me?” are making an upward comparison to other people who weren’t assaulted or who avoided an accident. The people who feel lucky to have survived are comparing themselves downwardly to people who had a worse fate. Both are valid interpretations, but the downward comparison helps you to hold on to optimism, summon the feel-good emotion of gratitude, and to weave a larger narrative in which you are the lucky protagonist of your life story.

Consider George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life. He embraces life again after an angel takes him on a tour of what the world would have been like had he never been born. In a 2008 study, researchers found that subjects who took themselves on a similar mental journey—thinking about a counterfactual life path in which a positive event like meeting a future spouse never happened—ended up “a little bit happier” than those who simply thought about the positive event itself. The jolt of happiness, which they called the “George Bailey effect,” comes from being surprised that a good thing can and did happen to you.

When times are tough, it might seem frivolous to cultivate a belief in luck. But that belief, psychologists say, can cast a spell that heals our wounds and gives us another shot at success, whether we’ve survived a bombing or just been on a bad date. ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/how-to-be-lucky?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Mary:

The research seems to say that luck is all in the interpretation. After any major event, from an earthquake to an illness, how do you see yourself—unlucky to have been there, or been injured, or suffered losses, or lucky to have survived, endured, witnessed.

I can think of a personal tragedy, my younger brother who had just found his first real solid relationship, and was soon after diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Unlucky to have such a short life, such a terrible illness, so much suffering, and so little time with his beloved. Or lucky to have such a true and faithful love for all the time he had left, something some live long and never have.

If you are always bemoaning your bad luck, it will follow you, like a cloud above your head, a cloud you tend and foster. If you are alert to possibilities, opportunities, good chances, you can pursue your own success, your good luck. Like so much else, luck is what you make it.

Oriana:

And, as with so much else in life, some people tend to take too little responsibility for what happened, while others take too much responsibility. Since I fall into the second group, I have to keep reminding myself of the power of circumstances. Yes, we make our own luck — but only to some extent.

*

COVID AND FERTILITY RATES

~ Experts have found that at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020, Americans chose not to become pregnant as they grappled with stay-at-home restrictions, anxiety, and economic hardship. Now, a new study led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine shows that some states actually experienced steeper decreases in fertility than others.

The findings revealed that 9 months after the pandemic began, there were 18 fewer births a month per 100,000 women of reproductive age across the United States compared with the year before. However, after the second wave in 2021, fertility fell by roughly 9 monthly births per 100,000 women, which was similar to the rate at which national fertility had been decreasing before the pandemic.

“Our findings suggest that while the overall national fertility rate rebounded remarkably quickly after the initial COVID-19 wave, the initial declines by state were as polarized as the country as a whole,” said study co-lead author Sarah Adelman, MPH, a research associate in the Department of Pediatrics at NYU Langone Health.

According to the state-specific results, New York experienced a massive fertility rate decline following the first wave, plunging from a pre-pandemic annual trend of 4 fewer monthly births per 100,000 women of reproductive age to roughly 76 fewer monthly births per 100,000 women. Delaware saw about 64 fewer monthly births for the same number of women and Maryland about 55 fewer monthly births per 100,000 women. As they had been in New York, annual fertility rate decreases in these states were in the single digits before the coronavirus outbreak.

By contrast, following the first wave, Idaho, Montana, and Utah experienced a boost of up to 56 additional births each month per 100,000 women of reproductive age — despite the fact that fertility rates in these areas had also been trending downward in the years leading up to the pandemic.

Adelman says that while previous research has documented national fertility-rate declines following COVID-19, the new study, published online April 11 in the journal Human Reproduction, goes a step further, comparing changes among individual states and examining factors that may account for the different rates.

For the research, the study team analyzed data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Bureau of Vital Statistics, the 2020 U.S. Census, and the University of Virginia 2021 population estimates to calculate fertility rate trends after each COVID-19 wave. The team then examined whether coronavirus case rates or other factors were the main drivers of fertility rate changes.

Contrary to their expectation, the severity of the coronavirus wave in each state appeared to have had little bearing on changes in that state’s fertility rate, the researchers say. Rather, demographic factors like racial composition and economic factors, including greater income inequality, higher percentage of college-degree earners, and large drops in employment at the start of the pandemic, negatively impacted rates.

The research team then examined states’ political leaning and a measure called the social distancing index (SDI), which tracked changes in people’s mobility following the first wave. They found that states with stronger social distancing responses and that were politically liberal had larger fertility rate declines following the first wave of the pandemic. When plotted on a graph, politically liberal places such as New York and the District of Columbia had the highest SDIs and lowest fertility rates, while more conservative states such as Idaho and Montana had the reverse.

“These results suggest that changes in a state’s fertility rates were not driven by COVID-19 cases themselves but rather by existing social, economic, and political disparities,” said co-lead author Mia Charifson, MA, a doctoral student in the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone.

“While these issues have always been linked with decisions about having children, they were clearly magnified by the pandemic, highlighting the need to address underlying social factors that constrain people’s ability to grow their families, especially during times of crisis,” added study senior author Linda G. Kahn, PhD, MPH.

Dr. Kahn, an assistant professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Population Health, cautions that since the researchers used state-level, population-wide data in their study, their findings cannot explain choices made by individuals.

Future research, she says, might examine more personal factors that influence decisions around pregnancy during times of crisis, such as student debt, job security, and access to childcare, in addition to existential concerns about climate change and political instability. ~

https://nyulangone.org/news/impact-coronavirus-states-fertility-rates-tracked-economic-social-political-divides

Oriana:

The article I really wanted was the one showing a pandemic-related baby boom in red states and a baby bust in blue states, but I was unable to open it:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-pandemic-caused-a-baby-boom-in-red-states-and-a-bust-in-blue-states/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

In the end, however, the article above also shows the differences between liberal and conservative states. Fascinating.

*

GODLIKE OR “TOTAL DEPRAVITY”?

”It’s not for me — religion. It seems like a redundancy for a poet.” ~ May Swenson.

My own sense of the sacred has two sources: the awe of the beauty of nature, and the awe of the collective human genius (as my mother, a neuroscientist, said, “The human brain is the most magnificent thing in the universe.”)

I wonder if to add another source — my “continual astonishment” at the creative process, the workings of inspiration and insight.

Goethe said:

He who has his art has no need of religion.

He who doesn’t have art, let him have religion.

And others have also said things to the same effect, e.g. An artist’s religion is art.

It certainly demands more devotion than any religion I know. A true artist is the saint and martyr of his/her religion. Van Gogh didn’t need to go to church. The funny thing is that he started out as a missionary preacher to the poor (Belgian coal miners). He wasn’t successful. His sermons were allegedly confused and convoluted. In any case, after his termination he never set foot in church again. But scholars think that he believed in Victor Hugo’s maxim, “Religions pass, God remains.”

From an article in Los Angeles Times:

“Van Gogh's melding of art and spirituality reflected the traditions of a family of both art dealers and religious thinkers. His grandfather, father and uncle were all ministers. They were influenced by two trends within the Dutch Reformed Church. One rejected the Calvinist view of original sin, salvation for a select few and predestination in favor of a belief in humankind's godlike nature, universal salvation and free will, Erickson said.

The other trend rejected miracles and supernatural events and sought instead to seek the divine more realistically in nature and community through painting, poetry and other forms of art. Later, the naturalistic tendencies of Zen Buddhism, which reached Europe late in the 19th century, added their influence to Van Gogh's thinking.”

My (Catholic) church certainly did not preach “man’s godlike nature.” We were told we were sinners, already at the age of eight. Human nature was allegedly sinful from birth (actually starting at conception — ours was not immaculate). I’m envious of those who had more enlightened religious instruction.

The first time I felt this envy was when another Protestant friend. I talked about the Catholic guilt (Nietzsche’s “a hangman’s metaphysics”) — the obsession with sin and punishment. She said, “My church told me god was love and would help me whenever she turned to him in a time of need.” I think she eventually became an agnostic — she never spoke about going to church. But she never spoke of having left it, and showed no hostility toward religion. I intuitively agree with the view that the quality of people’s atheism — militant or just indifferent or even benevolent toward religion — depends on the harshness or mildness of their childhood indoctrination.