*

LETTER FROM KAFKA

Dear Fräulein K, I can’t believe you ask,

Does God love us? You must joke.

We are the suicidal thoughts of God.

I always have a headache ready,

can easily arrange insomnia.

Today a neighbor coughed twice;

I know tomorrow

he’ll cough even more.

Do I complain too much?

My motto: If we cannot use arms,

let us embrace with complaints.

If only I could be not the nobody I am,

but the nobody I am paid to be.

On a balcony in my mind I leaned

to peony petals rimmed with rain,

when my superior, that good

sober man, asked if we carried

insurance for convicts —

I almost slapped him with both hands.

You see what an impossible

person I am. What strength it takes

to read this letter.

How you must hate me.

But I am unworthy of hate.

My father meanwhile grows and grows,

one colossal leg already in America —

he’s sprawling across the continents.

We have nothing in common, but then

what do I have in common with myself?

I must move away from home:

the sight of my parents’ nightshirts

makes me sick to the stomach.

I think of marriage

even more often than of death.

If only I could spend my life

in a cellar with nothing but paper

and pen, a ribbon of light

seeping in at the edge of the door —

But I won’t torment you by mail;

I’ll save it up until we meet.

If writing is prayer, who am I praying to?

not to the one who hangs

around our neck our daily stone.

Perhaps we shouldn’t meet.

I resent having to talk

when I could be writing you a letter.

You say, I don’t want to make love,

I want to make soul, make art.

Dear Fräulein: there is no art.

There is only the delight of failure.

Kindest Regards, K

~ OrianaKafka and his long-suffering fiancée, Felicia Bauer

*

~ "I promised I'd leave right away. Then he took me through a long hallway and from a large room with dark brown furniture to a narrow room in which on a single bed, under a blanket of white cloth, lay Franz Kafka.

He shook my hand with a smile, and with an informal gesture pointed out to me the chair at the foot of his bed:

—Please take a seat. Probably can only talk very little. Forgive me.

— It's you who has to forgive me for assaulting you in this way, but I thought it was really important to teach you something.

I took the English book out of my pocket, put it on top of the blanket in front of Kafka and told him about the conversation I had with Bachrach. When I told him that Garnett’s book copied the Metamorphosis method, he smiled tiredly and replied with a slight denial:

-No, no! That didn't get it out of me. It's something floating in the atmosphere these days. We've both transcribed it from our own time. Animal is closer to us than man. There goes the bars.

Relationship with animals is easier than with humans.

Kafka's mother entered the room.

—Can I offer you something?

So I stood up.

—Thanks, but I don't want to bother you anymore.

Mrs. Kafka gazed at her son. She had her chin up and her eyes were closed.

And then I said:

— I just wanted to bring you this book.

Franz Kafka opened his eyes and added, staring at the ceiling:

—I'll read it. Maybe next week I'll be back in the office. I'll take it there.

Then he reached out for me and closed his eyes.

But the following week Kafka didn't return to the office. It still had to be ten or fifteen days before I could walk him home again. Then he returned the book to me and said:

~ Everyone lives behind a fence that they always carry with them. That's why so much is written about animals now. It is the expression of nostalgia for a free and natural life. However, for a man natural life is living as far as being human. But no one realizes it. No one wants to see it this way. Human existence is too painful, that's why one wants to avoid it, at least in the field of imagination.

I continued to develop his reflection:

—It's a movement similar to the one before the French Revolution. Back then he was appealing for a return to nature.

—Yes! —Kafka nodded—. But today it goes even further. It's no longer just said, it's done. It's returning to the animal state, which is much easier than human existence. Well tucked in by the herd, the modern man parades the city streets in the direction of work, manger and fun. It's a perfectly matched life, like High School. There are no wonders, only instructions for use, formulas and regulations. Freedom and responsibility are feared. “That is why man prefers to drown behind bars that he has made himself.” ~

Gustav Janouch | Conversations with Kafka

“The living Kafka whom I knew,” Janouch writes in his post-script,

“was far greater than the posthumously published books, which his friend

Max Brod preserved from destruction. The Franz Kafka whom I used to

visit and was allowed to accompany on his walks through Prague had such

greatness and inner certainty that even today, at every turning point in

my life, I can hold fast to the memory of his shade as if it were

solidly cast in steel …. [He] is for me one of the last, and therefore

perhaps one of the greatest, because closest to us, of mankind’s

religious and ethical teachers.”

*

“NATURAL PARENTING” IS A WESTERN INVENTION

~ In the eyes of the Runa people, Western kids grow up indulged, over-mothered and incapable of facing outward to the world. ~

Imata raun paiga? (‘What is she doing?’) – my husband’s grandmother, Digna, asks him. The ‘she’ Digna is referring to is me. What I am doing is rather simple: I am wrapping my four-month-old son in a baby sling, his face toward my chest, in a calm, reassuring embrace. But my husband’s grandmother, who has raised 12 children in a small village in the Ecuadorian Amazon, does not think of this mundane gesture as being anything normal.

‘Why is she wrapping the baby like that?’ she insists, with genuine surprise. ‘This way the baby is trapped! How is he even able to see around?’ Squished inside the wrap, my son immediately starts crying, as if confirming his great-grandmother’s opinion. I bounce him up and down, in the hope of soothing his cries. I turn to Digna and say: ‘This way he is not overstimulated, he sleeps better.’ Digna, who has since passed away, is a wise, dignified woman. She simply smiles and nods, saying: ‘I see.’ I keep bouncing up and down, walking back and forth across the thatched house, until my son eventually snoozes and I can breathe again.

The relief of being able to breathe again: that’s perhaps a feeling familiar to most new parents. Like many other people I know, I also almost lost my mind after the birth of my first child. It’s hard to tell how the madness began: whether it started with the kind and persistent breastfeeding advice of the midwives at the baby-friendly hospital where I gave birth, or with a torn copy of Penelope Leach’s parenting bestseller, Your Baby and Child: From Birth to Age Five, first published in 1977, confidently handed to me by a friend who assured me it contained all I needed to know about childcare. Or maybe it was just in the air, everywhere around me, around us: the daunting feeling that the way I behaved – even my smallest, most mundane gestures – would have far-reaching consequences for my child’s future psychological well-being. I was certainly not the only parent to feel this way.

Contemporary parenting in postindustrial societies is characterized by the idea that early childhood experiences are key to successful cognitive and emotional development. The idea of parental influence is nothing new and, at a first glance, it seems rather banal: who wouldn’t agree, after all, that parents have some sort of influence over their children’s development? However, contemporary parenting (call it what you like: responsive parenting, natural parenting, attachment parenting) goes beyond this simple claim: it suggests that caretakers’ actions have an enormous, long-lasting influence on a child’s emotional and cognitive development. Everything you do – how much you talk to your children, how you feed them, the way you discipline them, even how you put them to bed – is said to have ramifications for their future well-being.

This sense of determinism feeds the idea of providing the child with a very specific type of care. As a document on childcare from the World Health Organization (WHO) puts it, parents are supposed to be attentive, proactive, positive and empathetic. Another WHO document lists specific behaviors to adopt: early physical contact between the baby and the mother, repeated eye contact, constant physical closeness, immediate responsiveness to infant’s crying, and more. As the child grows older, the practices change (think of parent-child play, stimulating language skills), yet the core idea remains the same: your child’s physical and emotional needs must be promptly and appropriately responded to, if she is to have an optimal development and a happy, successful life.

Like other such parents, in the first few postpartum months I also engaged, rather unreflectively, in this craze. However, when my son was four months old, during a period ridden with chaos, parental anxiety, sleep deprivation and mental fogginess, my husband and I made the decision to leave Europe. We packed our clothes and a few other things and hopped on a flight to Ecuador. Our final destination: a small Runa Indigenous village of about 500 people in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Our decision wasn’t as mad as it sounds. The Ecuadorian Amazon is where my husband grew up and where his family currently lives. It is also the place where I have been doing research for more than a decade. We wanted to introduce our newborn to our family and friends in the village, and we didn’t think twice before going. I could not yet imagine the repercussions this decision would have on me, both as a mother and as a scholar.

In the first weeks of our stay in my husband’s village, family and neighbors quietly observed how I took care of my son. He was never out of my sight, I was there always for him, promptly responding to (and anticipating) any of his needs. If he wanted to be held or breastfed, I would interrupt any activity to care for him. If he cried in the hammock, I quickly ran to soothe his cries. Our closeness soon became the subject of humor, and then, as the months passed, of growing concern. Nobody ever said anything explicitly to me or my husband. Most Runa Indigenous people – the community to which my husband belongs – are deeply humble and profoundly dislike to tell others how to behave. Yet it became clear that my family and neighbors found my behavior bizarre, if not at times utterly disconcerting. I did not really understand their surprise nor did I, in the beginning, give it too much thought.

People, however, started rebelling. They did so quietly, without making a fuss, but consistently enough for me to realize that something was going on. For instance, I would leave my baby with his dad to take a short bath in the river and, upon my return, my son would no longer be there. ‘Oh, the neighbor took him for a walk,’ my husband would nonchalantly say, lying in the hammock. Trying desperately not to immediately rush to the neighbors’ house, I would spend the following hours frenetically walking up and down in our yard, pacing and turning at any sudden noise in the hope that the neighbors had finally returned with my son. I was never able to wait patiently for their return, so I often ended up engaging in frantic searches across the village to find my baby, under the perplexed stares of other neighbors. I usually came back home empty-handed, depressed and exhausted. ‘Stop chasing people! He will be fine,’ my husband would tell me affectionately, giving me the perfect pretext to transform my anxiety into anger for his fastidiously serene and irresponsible attitude. At the end, my son always came back perfectly healthy and cheerful. He was definitely OK. I was not.

On another occasion, a close friend of ours who was about to return to her house in the provincial capital (a good seven hours from our village) came to say goodbye. She took my son in her arms. She then told me: ‘Give him to me. I will bring him to my house, and you can have a bit of rest.’ Unsure whether she was serious or not, I simply giggled in response. She smiled and left the house with my son. I watched her walking away with him and I hesitated a few minutes. I did not want to look crazy: surely she was not taking away my five-month-old son? I begged my husband to go to fetch our baby just in case she really wanted to take him away. When we finally found them, she was already sitting in the canoe, holding my son in her lap. ‘Oh, you want him back?’ she asked me with a mischievous laugh. To this day I am not sure whether she would have really taken him or whether she was just teasing me.

As an anthropologist, I admit, I should have known better. Scholars who work on parenting and child rearing have consistently shown that, outside populations defined as WEIRD (white, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic), children are taken care of by multiple people, not solely their mothers. The dyad of the mother-child relationship upon which so much of psychological theory rests reflects a standard Western view of the family as a nuclear unit – where parents (and, more specifically, mothers) are in charge of most childcare. In most places in the world, relationships with grandparents, siblings and peers are as important as the ones with the parents. As a new mother, however, it was difficult to appreciate this reality, especially when people were not merely claiming my son as their own but also clearly showing to me that what they thought was important for a child’s proper development differed quite dramatically from my own beliefs.

This became clear one day when Leticia, my husband’s aunt, came to visit us. Leticia had in the past affectionately joked about how caring and loving I was toward my son, and how amazed she was at the time and attention I devoted to him. As we were sitting together in our thatched house, Leticia took my son in her arms and started playfully talking with him. She tenderly touched his nose and laughed. ‘Oh poor little baby,’ she exclaimed suddenly. ‘Poor little baby, what will you do if your mother dies?’ She kissed him on the cheek. ‘You will be an orphan! Alone and sad!’ she laughed cheerfully. She then turned around so that I was no longer in my son’s sight. ‘Look! There is no more mama! She is gone, dead! What will you do, my dear?’ She kissed him again and laughed softly.

In her landmark book on Inuit child socialization, Inuit Morality Play (1998), the anthropologist Jean Briggs describes how Inuit adults ask children very similar questions. ‘Want to come to live with me?’ asks an unrelated woman to a toddler whose parents she is briefly visiting. Briggs argues that this kind of difficult teasing – which might sound inappropriate, even offensive to a Euro-American – helps young children think about matters of extreme emotional complexity, such as death, jealousy and loneliness. She describes at great length how, for the Inuit she worked with, this kind of teasing ‘cause[s] thought’. Likewise, I also often hear my family engaging in this kind of teasing with older children: this was, however, the first time I had become the target of it. For if Leticia’s teasing was intended to ‘cause thought’, my son was certainly not the only person she was encouraging to think.

Hers was not just an admonishment on the perils of a too-exclusive attachment, a reminder of the eternal fluctuations of life and death. It was also an invitation for me, as a mother, to take a step back and let my son encounter and be held by others, lest he be ‘alone and sad’. In a place like a Runa village, where cooperation, work and mutual help are so important for living a good life, Leticia seemed to be telling me, my son truly needed to be with other people beyond his mother. Leticia’s episode made me think about Digna’s puzzlement at the way I carried my baby.

Despite the calm, respectful response Digna gave me at the time I was wrapping my son, she must have thought I was crazy. What could the concept of sensory overstimulation have meant to her? Runa children are carried around in a sling with their faces toward the outside, all the time, everywhere, from dawn to night, under the rain and the sun, in the garden and in the forest, at parties that go on for hours where they fall asleep to the sounds of drums, cumbia music, and the excited yells of dancers. When Digna carried my son, she did so the way all Runa women do: either on her back, or on her hip. Digna made sure he could turn his face to the outside world. ‘This way he can see everything,’ she said to me.

I started from the assumption that my child needed to be protected from the world, his face safely turned toward his mother; she thought that a child needs to be turned toward other people, toward the world, because he belongs to it. Overstimulation, for Digna, was just the necessary work a baby has to do to become a participant in a thriving, exciting social life. To let children face the world re-orients their attention towards sociality, toward others.

In one of their papers, the psychologists Barbara Rogoff, Rebeca Mejía-Arauz and Maricela Correa-Chávez beautifully describe how Mexican Mayan children pay more attention to their surroundings and to other people’s actions compared with Euro-American children. They explain the difference with the fact that Mayan children, unlike their Euro-American counterparts, are expected to actively take part in community life from early on. The practice of paying attention to social interactions, this encouragement to turn toward the community, seems to start, at least among the Runa, well before babies can speak or help at home. It starts, as Digna put it, by literally turning their faces toward the world.

If the idea of an exclusive, preponderant relationship between mother and son might have seemed alien to our Runa family, equally strange, if not plain wrong, was the idea that a child’s needs should be always and promptly met by her caretakers. This is another central idea of current parenting philosophies: children’s emotions, needs and desires should be not merely accommodated, but also promptly, consistently and appropriately responded to. This translates into a form of care that is highly child-centered, whereby children are treated as equal conversational partners, praised for their achievements, encouraged to express their desires and emotions, stimulated through pedagogical play and talk, often with considerable investment of time and resources.

These practices encourage the gentle cultivation of what the anthropologist Adrie Kusserow has defined as ‘soft individualism’, in which self-expression, psychological individualism and creativity are core values. It is not a coincidence that these are also qualities promoted in a neoliberal society where entrepreneurship, self-realization and individual uniqueness are deemed paramount for success and happiness.

Taking this worldview up a notch, some people claim that findings from neuroscience support the goal of ‘optimal’ brain development as foundational to a child’s future success and happiness. The ideology is presented as if based on indisputable scientific evidence, but let us not be fooled. The approach fits perfectly with neoliberalism and has its origin in the culture of the US middle-upper class.

Proponents describe the intensive care that results from this pursuit as ‘natural’, drawing on idyllic and stereotyped accounts of childrearing in ‘traditional’ non-Western societies. There is a popular book I am often given as a gift by other parents whenever I mention that I work in the Amazon and am interested in children. It is The Continuum Concept: Looking for Happiness Lost (1975) by Jean Liedloff. The back cover of the German edition shows the author in the jungle: she stands, tall and blond, in a shirt and a leopard-print bikini next to a bare-breasted Ye’kuana woman and her sleeping baby. The book – a bestseller in the so-called natural parenting movement – tells the story of Liedloff who, after living for two years with the Carib-speaking Ye’kuana of Venezuela, discovers the recipe for raising well-balanced, independent, happy children. This amazing result is accomplished, we are told, through practices such as co-sleeping, responsive care and natural birth.

Liedloff’s book, like the natural parenting movement, is based on the idea that people in industrialized Western countries have lost touch with the childrearing ways of our ancestors. Bringing together attachment theory, as well as a simplified theory of human evolution and cherrypicked information about childcare in non-Western societies, this approach is premised on the fantasy that there is a ‘natural’ way to raise humans. While responsive parenting and ‘natural’ parenting are not exactly the same, they can be thought of as two dots on a continuum: they both assume there is an optimal way to raise children that, if not followed, has negative consequences.

The type of childrearing that both models encourage is also equally intensive and child-centered.

What these accounts, which claim roots in anthropology, fail to reflect is that, outside of postindustrial affluent societies, no matter how cherished, children are very rarely the center of adults’ lives. For instance, Runa children, while affectionately cared for, are not the main focus of their parents’ attention. In fact, nothing is adjusted to suit a child’s needs. No canoe trip under a merciless sun is modified to meet the needs of a baby, let alone of an older child. No meal is organized around the needs of a young child. Parents do not play with their children and do not engage in dialogical, turn-taking conversations with them from an early age. They do not praise their children’s efforts, nor are they concerned with the expression of their most intimate needs. Adults certainly do not consider them as equal conversational partners. The world, in other words, does not revolve around children.

This is because children are not relegated to a child-only world nor deemed too fragile to engage in difficult tasks. From an early age, Runa children participate fully in adults’ lives, overhearing complex conversations between adults on difficult topics, helping with domestic tasks, taking care of their younger siblings. Participating in the adult world means that sometimes children can get frustrated, or denied what they want, or feel deeply dependent on others. At the same time, there is so much that they gain: they learn to pay close attention to interactions around them, to develop independence and self-reliance, and to forge relationships with their peers.

Most importantly, in this adult world, they are constantly reminded that other people – their parents, their family members, their neighbors, their siblings and peers – also have desires and intentions.

The psychologist Heidi Keller and colleagues wrote that good parenting for many societies is primarily about encouraging children to consider the needs and wants of others. The Runa are no exception. They enormously value qualities such as social responsiveness and generosity – capacities deemed indispensable for living a good life in a closely knit community. These presuppose the ability to acknowledge and respond to other people’s desires and needs. Runa childrearing practices reflect these priorities. The very idea that children’s needs and desires should be always and promptly met by caretakers is completely foreign to the Runa. Instead, not answering to some of these needs and desires might be a valuable practice.

This is evident in an episode that occurred shortly after we arrived in Ecuador. I was then zealously following the breastfeeding instructions I received from the midwives (exclusive and on demand! In a quiet place and without interruptions! As recommended by the WHO! And the baby-friendly hospital initiative!) I was baffled when one day, right in the middle of breastfeeding, our neighbor, Luisa who was sitting next to me, placed her hand on my breast and took the nipple away from my son. He looked at me surprised. He grunted loudly. Luisa laughed. ‘Do you want your milk, little baby? Do you really want it?’ She kept my breast away from him. I watched her teasing him, trying to escape from her without looking rude or excessively defensive. ‘Your poor mama!’ she continued without paying attention to me: ‘Just leave her alone! This is not yours!’ My son became purple with rage and twisted in my arms. Luisa laughed again, removed her hand and kissed his little hand. I did not know how to react: my feelings ranged between confusion and anger. I asked my husband why she would do such a thing. He stared at me blankly. ‘To tease the baby! To let him know that the breast is not really his,’ he answered matter of factly.

Why did Luisa make my son purposefully uncomfortable? What was her goal? The more I reflected on this, the more I began to see the teasing as crystalizing a central moral lesson: in stating ‘this breast doesn’t belong to you, it is your mother’s’, Luisa redirected my son’s attention to the presence and desires of others. The intentional, playful refusal to attend to a baby’s desire for milk invites him (and anyone else present) to acknowledge that he is not the only one who has a will and desires in an interaction. It is exactly by these acts of playful refusal, by not promptly responding to their children’s will, by not making them the center of their world, that the Runa cultivate in their children an awareness of other people’s needs and of their own place within a dense web of relationships. The childrearing goal here is to transform a child into someone who recognizes and acknowledges that her own will is just one among many.

Unlike what parenting books might tell us, there is simply no single recipe for good parenting. This is because each act of parenting is always and inescapably an ethnotheory of parenting: a set of practices that aim to shape a good person in a given society. Of course, one doesn’t need to travel to all the way to the Amazon to realize that. Step out of the privileged space of what Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich in 1979 called ‘the professional-managerial class’, and the kind of debates surrounding childcare are likely to be very different. However, because this is a parenting ideology produced by a cultural and political elite that has a tremendous power in the world, it has quickly become normalized.

What is most worrying is to see this ideology being increasingly exported, under the guise of evidence-based early childhood interventions, to the Global South. Promoted by organizations such as the WHO, the World Bank and UNICEF, such interventions aim to teach low-income families in the Global South to become responsive carers and optimize their children’s cognitive and emotional development through the adoption of ‘appropriate’ behavior. These programs assume optimal childcare to be a universal, objective, neutral fact that can be easily translated into a plethora of handy practices.

This model of childrearing (and its more extreme neuroscientific version, where every act is seen as enhancing or hurting the brain) is anything but apolitical and a-cultural. Instead, it finds its origin in a specific culture and socioeconomic context where everything (including children’s abilities) can be measured and optimized in terms of future life success.

To assume one cultural model of childcare is universally applicable to children everywhere, as WHO and others do, is dangerous. Not only do such programs encourage culturally specific childrearing with little scientific basis, they also depict any type of care that deviates from the norm as in need of correction. Like early missionaries who traveled around the world teaching the natives how to be ‘good’, such interventions assume that parents in the Global South need to be taught how to raise their children properly.

Following current orthodoxy, Runa childrearing – with its casual breastfeeding, abrupt weaning, no extensive parent-child play, no lengthy adult-child talk – would be described as ‘lacking’ in so many respects. And yet, my Runa friends and family thought my own childcare practices were conspicuously inadequate to raise a child in the context of their community life. Their observations, their puzzlement and their quiet defiance of my own childcare practices remind us that, whenever we talk about childrearing, we are not talking about achieving some objective child development based on irrefutable scientific evidence, but rather about a moral project: a moral project about what kind of people we would like our children to become, what society we would like to live in, and what kind of economy we would like to serve. As my Runa friends and family have subtly but relentlessly demonstrated, there is more than one way to flourish as humans in this world. ~

https://aeon.co/essays/why-runa-indigenous-people-find-natural-parenting-so-strange

Sage Coward:

In essence, our society places high value on individualism, creativity, innovation, and capitalism, all of which rely on inner richness and personal drive. However, the challenge arises in the Western context, despite our education and affluence, when we mistakenly conflate these qualities with relationships. It is important to recognize that all relationships, by their very nature of “relating,” involve elements of collectivism. By emphasizing individualism, which is primarily a paradigm of the mind rather than a relational or attachment-based concept, we inadvertently deny the reality of engaging with others.

Whirled Peas:

I completely understand the inclination to not allow all indigenous (or non-Western) parenting practices to be lumped into one amorphous heading and labeled “natural” parenting. That would be lazy and sloppy thinking.

However, most of us don’t know what else to call the plastic, chaotic, Chuck E Cheese, addicted to screens, isolated, single family home, domination model .. except for “unnatural.”

*

We take it for granted that life is hard and feel

lucky to have whatever happiness we get. We do not look upon happiness

as a birthright, nor do we expect it to be more than peace or

contentment. Real joy, the state in which the Yequana spend much of

their lives, is exceedingly rare among us. ~ Jean Liedoff

*

Oriana:

Ideally, the mode of parenting would make both the parents and the children happy. The parents would be more relaxed, and the children more independent. Alas, we live in a world that’s anything but “natural” — only a commune can replicate a “village” that a child can thrive in.

So the most important first step would be to acknowledge that there is no “ideal” way to rear children. More collective way of caring for small children have been tried (e.g. in Israeli kibbutzim) — only to be discarded in favor of the nuclear family, perhaps with the participation of grandparents. Bruno Bettelheim observed that children raised communally in a kibbutz tend not to be individualistic, but rather have a collective set of mind. They show little individual ambition; rather, they think of what is best for the group. They don't seem to have a rich inner life.

In a culture that values individualism, we want to know the unique talents that a child might have rather than how to enhance the child's sociability. We pay lip service to "team work," but grade the child's individual effort. (Personally, I hated "team work," because one bad apple -- or a child that hasn't yet developed the right competence -- could ruin the whole endeavour.)

Finally, as Una, a poet-friend of mine and a mother of five, used to say, “No matter what you do as a parent, your children will still turn out their own way, each one different.” She had no delusions about shaping a child’s destiny. The took joy in being the child’s first teacher, but fully understood that genes and peers may be more decisive, along with other factors beyond a parent’s control. So Una's "it doesn't matter all that much what you do as a parent" is a dose of humility and common sense that goes counter to many parenting books.

She said she learned a lot from her children. I think I learned a great lesson from dogs and cats: you have to let a dog be a dog and do doggie things, just as a cat better be allowed to choose its own favorite places to sleep. I think you need to let a child be a child -- let go of trying to control everything, and watch with wonder the developmental program unfold.

Mary:

*

THE LAST TZAR, NICHOLAS THE SECOND (SGT. CAREY MAHONEY)

~ Tsar Nicolas was an imbecile. Who else would make the same mistake twice? Once, maybe. In 1905 he started Russian-Japanese war, which he lost miserably, loosing his entire fleet. The defeat led to the 1st Russian Revolution of 1905, which his regime survived, by giving up on complete control over the empire, allowing long overdue reforms — establishing local and central democratic bodies (Duma etc.), independence of the judicial branch, etc.

Russia embraced the reforms and moved forward to catch-up with the rest of the civilized world. Then he decided to go to war again — this time, with the coalition of Central Powers, on the side of Entente Powers. The less than spectacular results of the first 3 years of the WWI, led to the Revolution of February 1917, and the rest is history. So, he was a stubborn fool after all. His demise was of his own making. ~ Quora

Gary Keith:

His wife begged him not to go to war with Germany, but his generals overruled her. A good account of this is given in the book The Hidden History of WWI by Jim MacGregor. The Tsar was so indecisive and vacillating that his generals cut the phone lines so he couldn’t change his mind and countermand their order to mobilize against Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Tsar should have abdicated in 1905 and let a more capable member of the Romanov family rule Russia.

William Garrison:

Russia was defeated soundly by Japan. So, nine years later, Nicholas thought, ‘certainly we can beat the Germans and Austrians'.

Raymond Mickey:

Russia’s greatest chance to become more European and change the world as we know it today. They had another chance with Gorbachev, but I think economic conditions and the legacy of communism were too much for the Russian people to overcome.

Jack Reidhill:

He did believe he had a Divine Right as Tsar. Everything he did was ordained. Every thing he did was an argument for a system that didn’t promote the ruler’s son. Not that the Soviet Union was a whole lot better.

Oscar Rosen:

He thought that that he was the father of Russia and that the peasants loved him. They actually liked feeding their families and harvesting their crops, not going to war with rusty weapons and cloths tied around their feet because they had no boots. Jews disliked him as he sent Cossacks to kill Jews periodically while conscripting Jewish men for many year, even decades.

Alexey II:

In fact, Emperor Nicholas II not at all as bad a ruler as claim many of the miserable historians who simply plagiarized the Bolshevik agenda. From 1905 until WWI, Russia made great progress on all fronts. Even a fledgling democracy had begun. For Europe, WWI and the 1917 coup d'état in Russia were a catastrophe. It was predicted by French economists that Russia would be Europe's leader, political and economic.

Oriana:

The last tsar may not be a particularly inspiring figure, but that's beside the point. The way he and his family were slaughtered was an act of shocking barbarism. Until the Russians can officially admit and repudiate this act -- and the many worse crimes committed under the Soviet rule -- they will remain captive of the "might makes right" mentality, unable to fully join Europe and the West.

*

RUSSIA: WE DON’T APOLOGIZE (Dima Vorobiev)

It’s complicated.

In private, it hugely varies from person to person, from situation to situation. In public, when asking for apologies, you step into a minefield.

To start with, our national idea is power. An apology is too easily misunderstood as a weakness. Apologizing for things corrodes your power. The Chechen strongman Ramzan Kadyrov just loves making people who offended him one way or another record apologies on camera in the presence of his stern-faced bodyguards.

If your name is President Putin, you can afford to apologize for some petty trifles. But for the rest of us mere mortals, Donald Trump’s je-ne-regrette-rien approach may be the safest.

Especially among the movers and shakers, an apology is a kind of an IOU promissory note. They see it as a bit of the post-WW2 thing between the Germans and the Jews. Nice of you to admit you were wrong, when can I expect your check to come?

The ritual

Among pious commoners, there was a habit much celebrated by Tolstoyevsky [sic: possibly to indicate a fused Tolstoy-and-Dostoyevsky model of wisdom] and some Russian philosophers. From time to time, a random man would erupt into verbal self-flagellation in the middle of a marketplace or in front of a church on a day of heavy traffic, and ask for forgiveness for his sinful ways. This was performed kneeling, with a plaintive voice, in tears, and with chaotic open-handed gestures.

For many, unburdening oneself of one’s sins this way was easier than apologizing to particular persons. Orthodox God and the peasant community were probably also better mediators between the offender and the offended.

Upward PC

The Western PC is derided in Russia for its silly logic of not being free to offend those weaker than you. In Russia, we counter it with our own correctness. Our PC is about not offending those stronger than us, those who can hit back with disproportional force.

Our bosses and our State are particularly protected. You can get several years behind bars for saying the wrong things about President Putin. The Orthodox Church, very vocal and righteous in its diatribes against Russia-haters, never raises its voice against our Derzhava (“the mighty State”), no matter if it’s ruled by Marxists, German aristocrats, or career spies.

Profusely apologizing before the superiors is part of this. As long as we call the errors of our bosses our own, stability and peace are upheld. Once we start wagging our fingers toward those in power, chaos and misery creep in. This happened back in 1917 and 1991.

Victims do not apologize

On top of that, as a nation, we consider ourselves some of the most abused and tormented throughout history. In order to not offend our Derzháva, we usually blame foreigners for most of it. “Roads” and “morons” share the rest of the blame. [“Roads” here means “bad roads”; Russian roads are notorious for poor maintenance]

Since we’re true victims of evil fate and malicious foreigners, it would be absurd for us to apologize for anything. Especially after saving the West from Nazism in WW2.

As our world-famous winner of a Nobel Prize in literature, exiled poet Joseph Brodsky said back in 1988:

The only reason the West shows interest in us is the fate of our country. Our country has a completely unique experience. Specifically, how people were made to live in the most constrained circumstances imaginable: barefoot, hungry, and so on.

In other words, it’s our misery that really counts. Apologizing? What for?

*

Below is a painting by Vladimir Sizov, "The heroes of Donbas" from 1987. Young men in military pants bring our wheelbarrows of coal in the area where Russia is now fighting back against the Ukrainian Judeo-Nazis [sic: this are Dima’s words; perhaps he's being sarcastic, but I'm not sure]. The red flag means they have shown an exemplary work spirit for the cause of Soviet rule.

These men don’t feel like saying sorry for anything. Whatever apology quota they may have had was fully spent on their bosses. ~

Oriana:

Alas, this seems to confirm what I remember from childhood on: The Soviet Union never apologized. Russia never apologized. Germany apologized, imagine! — but never Russia.

Germany even paid reparations. Never Russia.

Willy Brandt famously knelt down at the monument to the heroes of the Jewish Ghetto uprising.

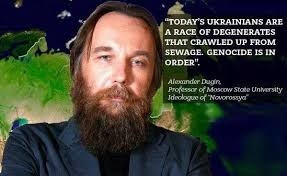

But Alexander Dugin never apologized for his incitement to genocide:

I can't imagine any Western politician or public intellectual, even the most reactionary, making a statement calling for the genocide of Mexicans, for instance. This is unbelievably sick. Are we back in Hitler’s Germany? No, in today’s Russia. That’s where “might makes right” and you never apologize.

*

THE OTHER RUSSIA

"Germans have understood that the lesson of their history is not that Germany must remain forever pacifist. The lesson is that Germany must defend democracy and fight the modern version of fascism in Europe when it emerges". (...) (In Russia) The unpopularity of this war is going to grow, and as it gets bigger, the other Russia—the different Russia that has always been there—will grow larger, too.” ~ Anne Applebaum

Oriana:

So glad that she reminded us of the "other Russia." Not the hypernationalist, militarized, pro-Putin Russia, but those who oppose Putin’s imperialist ambitions. These “other Russians” may be too scared of prison and torture to do it in public, but then it's only exceptional people who are heroic. The most brave among them remind us that the “other Russia” exists.

On the other hand, I don’t judge those who chose to leave Russia. Most people simply want to live a normal life. Those who leave are often the best and the brightest, who would rather use their talents and skills to contribute to the West (Israel is part of the West; it’s not a matter of geography, but of values — e.g. human life is not cheap; human rights are important; might doesn’t make right).

*

THE BRONZE AGE COLLAPSE: A MYSTERIOUS MULTIPLE CATASTROPHE

In the 13th century BC, the Eastern Mediterranean was a home to bustling, advanced civilizations. They built great cities, large monuments, and were all connected by an intricate trade network. In just 50 years, a complete reversal occurred and nearly every city from Greece to Judea was annihilated. At the time, this arc, Egypt, and Mesopotamia constituted the vast majority of the planet’s advanced societies. The devastation was so complete that historians have no written record of what happened and have to put together hypotheses purely based on archaeological evidence.

In Greece, around 90% of towns were abandoned or destroyed. The more famous Dark Age that followed Rome’s fall never came close to this level of desolation. In those supposed Dark Ages, some areas, like England and Germany actually became more developed and populous than they ever had been. During the Bronze Age Collapse, writing completely disappeared from Greece for centuries until Phoenician traders arrived in the late 9th century, inspiring a completely new writing system. Even things as simple as pottery became simple and unadorned. This was a common theme, with civilizations being completely destroyed, re-emerging in different forms centuries later or being replaced with new ethnic groups.

The only areas to survive were Egypt, which was pushed to the brink by foreign invasion, and Assyria. However, both kingdoms would succumb to internal strife a few decades later. Still, the destruction visited upon most of the world’s civilized lands took centuries to recover from.

All of this devastation, and there are only unproven hypotheses. Traditional theories revolved around the Sea Peoples, who destroyed a lot of cities and killed a lot of people. But it's hard to reconcile an invasion, as brutal as it is, with the unmatched devastation of the era.

Several major natural disasters might have greatly contributed to the chaos. There was a large volcanic eruption, a string of earthquakes, and a mass region wide drought all within a matter of decades. Expanding populations could have also pushed delicate ecosystems too far, exhausting the soil and causing famine as crops failed. Then the introduction of ironworking made it easier to equip large armies of peasants, destabilizing the noble-run system of small elite armies of the Bronze Age.

None of these single disasters by themselves ever caused as much damage to later societies. Chances are, only a perfect storm of all these factors together could have caused so much destruction. But again, we don’t know, because while the Romans left us written stories of their demise at the hands of Goths, Franks, Saxons and others, the Bronze Age Collapse only left us the deafening silence of bone and demolished brick. ~ Brandon Li, Quora

John Bard:

The BAC is probably the most interesting single event in the history of western Eurasia, and its telling that the only description we've managed for it so far is “systems collapse” which is a posh way of saying “literally everything went to hell for some reason”.

Zachary Reids:

It always amazed me that we know so little about the Sea Peoples. Where exactly did they come from, and why? How did an armada of people on small boats from distant shores wreak such havoc on vast urban civilizations?

One of those tribes (the Sherden) likely came from Sardinia, and probably some were from Greece, but we’re unsure about most of them as far as I’m aware. Apparently there were pretty severe droughts making agriculture untenable across much of the northern Mediterranean, and this may have triggered the alliance of sea peoples.

Stuart Bunt:

Could it have been something like the Black Death? Malaria is now thought to have hastened the fall of Rome.

David Rendahl:

Deafening silence or myth to be unlocked. The siege of Troy especially feels like memories of a dark age, a man made disaster — the travails of Odysseus and Perseus and the Golden Fleece — all hint at something lost and wanted back — much to do with man overstepping his mark and brought down by pettiness. I think they left us loads of clues.

Angela Noske:

I believe the most impressive indicator of the sudden end of Bronze Age are the ruins on the Greek island of Knossos. A very impressive indicator of how advanced human society was around 1750 BC.

Chris Bruenn:

There was an outbreak of the Black Death. It came out of Africa and wiped out the Phoenecian mercantile fleet, as well as everyone who ate grain from Egypt. It is actually mentioned in the Iliad.

Since that time modern human brains shrank, on average. Life was harder in the Iron Age.

[Oriana: There is no evidence for the supposed shrinkage.]

Jan Steinman:

I’m surprised you didn’t mention the deforestation of the Peloponnesian Peninsula.

Greece essentially clear-cut their forests to build warships. This caused a regional extended draught, which turned the entire area into the semi-desert it still is today. Farmers could no longer supply the quantities of food they had previously supplied to the cities.

“Civilization is proceeded by forests and followed by deserts.” — David Holmgren, who writes of the fall the Greek city states in Permaculture: Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability

Mark Sieving:

The kingdom of Israel arose out of the power vacuum left by the Bronze Age Collapse. Without the collapse that area would have remained under Egyptian or Assyria control, and it's likely that the Abrahamic religions would not have developed.

Wayne Scoble:

A virus emerging such as smallpox, for the first time would be utterly devastating; it was certainly bad enough in later centuries. Still, who knows? A series of catastrophic events usually brings the 4 horsemen.

*

THINGS YOU WERE TAUGHT THAT ARE JUST PLAIN WRONG

The older you get the more you realize that a lot of things you were taught in your youth are just plain wrong.

You can be anything you want to be. No, no you can’t. There are tests you won’t score high enough and that will prevent you from being accepted into whatever program you desire. All this despite having the intelligence and skill needed to excel at whatever the profession may be. Even if you have the right credentials and experience, if they are not hiring for what you want to do…well…you may be out of luck. There are miles of reasons why you can’t be whatever you want to be.

But guess what, you can be the best at the opportunities life presents to you.

Hard work is rewarded.

No, not always. Sometimes the power of the universe conspires against hard working individuals and unfairly rewards our lazy, short cut seeking, less intelligent friends, co-workers, and acquaintances.

But if you knuckle down, don’t let the unfairness of the world ruin your attitude, show up everyday, and do your best, then because of your hard work you definitely increase the odds of having a fulfilling life.

Money and wealth are your greatest asset.

No, no they are not. They are important and provide security and freedom.

But your health is your greatest asset. If you have terminal cancer or some other horrifying condition, all the money in the world does not matter. In fact, if you get type 2 diabetes or heart disease, what you can do is radically impacted. So invest in your health daily.

That others care about your house, your clothes, your toys, and you in general.

No, no they do not. We all think others are concerned with what we have or don’t have. They’re not. In fact the people we think are thinking about us, usually are not thinking about us at all. The world doesn’t really care about you.

But, if you are lucky, you have a few people who do truly care about you. It’s usually a very small number of people. They are the people that truly matter in your life and they probably could care less about all your toys.

That we will all live forever. No, no you won’t. Sure, no one ever comes out and blatantly tells you that you will live forever. But every message we get on TV, social media, or culture in general seems to want us to believe we are immortal. Worse yet, our own minds seem to lead us around as if we are going to see the next two centuries.

But, you are going to die. Everyone you know is going to die. That should not scare us. It should free us. Free us to be present in every moment because this moment is all we really have. The past is gone. The future is not guaranteed. We have today. Embrace it and allow it to grow the love you have inside you. Then share that love.

Joseph Santagatha:

That formal education makes a difference. No, no, no difference. Who you know is of utmost importance.

Oriana:

Certainly true of the poetry business — and I was told that “po-biz is worse than show-biz.”

*

THE END OF HOME OWNERSHIP? (AT LEAST IN CANADA)

I was born in Vancouver in 1987, and I’ve lived here nearly all my life. Anyone of my generation who grew up in this city spent their youth hearing constantly about the twin dangers that imperiled our future: a city-annihilating earthquake, and the always-rising cost of housing. Either might one day make living here impossible. Both felt vast and inevitable, forces beyond our control. So we carried on in the face of disaster, doing our best to ignore it.

In 1992, the year I did my first earthquake drill in kindergarten, Vancouver overtook Toronto as the most expensive housing market in the country. After finishing an undergraduate degree in Victoria, I returned in 2009 and spent my 20s moving from one rental to another—seven apartments, six neighborhoods and five roommates in all. Fourteen years ago, it was still possible to find an apartment for $650 or $700 a month, especially if you were willing, as I was, to tolerate a gas leak, a creepy landlord or a solarium repurposed as a bedroom in exchange for below-market rent.

A few of my friends even made the leap into ownership in their 20s, almost always with the help of family. In the early 2010s, you could get a small one-bedroom or a studio apartment for $300,000 or so. That was a significant downgrade from my parents’ generation, for whom an equivalent inflation-adjusted sum would have bought a single-family home nearly anywhere in the city. But it was a foothold on the property ladder, and I believed then that it would be possible for all of us to do the same, to make our homes in this city we loved. We would, somehow, follow the upward trajectory of previous generations, whose rising incomes allowed them to graduate to homeownership in due course.

Besides, the market had to correct eventually, right? How could it not, as the chasm between incomes and cost of living kept growing? In 2012, when the benchmark property price in metro Vancouver was $638,000, Yale University economics professor and housing analyst Robert Shiller predicted a crash: “Just because it’s a nice place to live doesn’t mean prices are going to go up forever,” he said.

But they haven’t stopped climbing yet. The benchmark property now costs $1.2 million, propelled upward year after year by low interest rates, constrained supply, investor speculation and a growing population. And year after year, I’ve watched as more friends have left Vancouver for smaller towns, or Alberta, where they could afford a dog, a yard, a baby.

In retrospect, they were lucky to have left when there was still somewhere else to go. While an impending big earthquake remains a localized source of dread, the fear and anxiety surrounding housing has exploded into a national phenomenon. The benchmark property price across Canada more than doubled between 2015 and 2022, from $409,000 to $861,000. In the same period, average wages increased only 23 per cent, not accounting for inflation.

Cities large and small, from Victoria to Toronto to Windsor to Moncton, are now grappling with the same intractable problems. There is too little housing, far too little affordable housing and far too many investors bidding houses up and out of reach, creating a rapidly widening divide between Canada’s housing haves and have-nots. Those fortunate enough to already own property have watched their net worth soar along with the value of their homes, even as millions of others have been shut out. In 1986, a young adult working full time could expect to save for a down payment in five years. Now, they’d have to save for 17 years—nearly 30 in Vancouver or Toronto.

For decades, Canadian society has positioned homeownership as a promise, a sure path to security and prosperity. As it slips out of reach, young Canadians are struggling to build community, start families and plan for the future. At this scale, the problem doesn’t resemble an earthquake so much as a more human-caused catastrophe. Like climate change, it’s the result of policy choices and behaviors that have tipped the scales toward disaster for decades.

The result is a pervasive sense of what I’ve come to think of as housing nihilism, especially among those under 40—millennials and Gen Z—who are most affected. In conversations with thwarted would-be homeowners across the country while writing this story, I heard the same feelings reiterated time after time. There was anger at the ever-growing unattainability of homeownership, at the loss of the stability it represents and of an inheritance for the next generation. There was resentment at being relegated to indefinite renting in a cutthroat market controlled by an increasingly exclusive cohort of the housing haves. And there was despair at their straitjacketed circumstances—because the rental market has gone just as haywire, and many can’t afford to move. If they do, they’ll be forced to leave their cities altogether, and their careers, friends and families.

We talk about the housing crisis all the time—in headlines, on playgrounds, at dinner parties, on social media. We talk about how our government should fix it: radical rezoning, more supply, more public housing, taxes on speculation and foreign owners and empty houses. There are lots of solutions, but none are silver bullets. All will take years or decades to make a difference. In the meantime, the disparity between property owners and everyone else is already eroding generational ties and stoking bitter resentment. It risks distorting our politics, the functioning of our cities and younger Canadians’ financial security. If nothing changes, homeowners will keep getting wealthier, but even they won’t be able to kick the costs down the road forever.

*

Canada hasn’t always been a nation obsessed with homeownership. Before the Second World War, fewer than half of Canada’s city dwellers owned their own property. The authors of the 1931 census report even declared that the advantages of homeownership were “undermined in urban areas by the convenience and attractiveness of modern multiple-unit dwellings”—renting, in other words.

After the war, everything changed. To accommodate returning veterans and an influx of immigrants, and to create jobs that would sustain the postwar economy, the federal government made massive investments in housing. It built nearly 45,000 homes across the country and, in 1946, created the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The CMHC administered housing programs, making loans to builders and homeowners and overseeing social housing. It also extended favorable mortgage terms to borrowers. In 1954, the government began insuring private mortgages. With loans guaranteed by the government, banks were more willing to lend money. That lowered barriers to homeownership and helped spawn an explosion in single-family housing in Canada’s rapidly growing suburbs.

The combination of accessible mortgages and cheap housing quickly turned Canada into a homeownership society, making middle-class Canadians into masters of their own little domains. In metro Toronto, the homeownership rate grew from 40 per cent of households in the 1930s to a peak of nearly 70 per cent in 2011. A home became one of the primary foundations on which individual Canadians built their financial well-being—not just a place to live, but a rock-solid financial asset.

Of course, the benefits of homeownership were never truly democratic. Low-income Canadians, disproportionately racialized, have always had lower rates of ownership, and Indigenous people have been particularly excluded from its benefits. Under the Indian Act, First Nations people on reserve don’t own the land where they live. They’ve never been able to build intergenerational wealth through housing the way non-Indigenous homeowners have.

Still, as long as housing prices tracked upward in line with incomes, the central promise of an ownership-driven society remained intact for Canada’s mainstream middle class. If you put in the hard work, you too could buy a home.

That was still the case until relatively recently, even in our biggest cities. After a price run-up in the 1980s, the average home in the Greater Toronto Area declined in value during the first half of the ’90s, dropping from $255,000 in 1990 to $198,000 in 1996. Prices settled modestly higher by the end of the decade, at $228,000. But in the early 2000s, as mortgage rates continued to fall, prices began climbing faster. By 2005, the average GTA home cost $336,000. By 2011, the figure was $465,000. Suddenly, being a homeowner, at least in certain cities, was a license to print money.

In hindsight, that marked the point of departure. Spurred on by low interest rates, growing populations and an inadequate supply of new housing, home prices started rising much, much faster than incomes. From 2001 to 2011, the average GTA home more than doubled in value, while incomes stagnated—the median household income in the area rose from $59,000 in 2001 to only $70,000 in 2011. (That looks like an 18 per cent increase on paper, but it’s actually a decrease in real terms, slightly below the rate of inflation.)

That decoupling accelerated in 2009, after the Bank of Canada dropped interest rates further to shield Canada from the kind of housing crash that decimated the United States. It worked. Home prices climbed faster than ever, propping up the Canadian economy. This lopsided national reliance on real estate has only grown in the past 15 years. Today, buying, selling and leasing property represents the largest segment of our national GDP, at 13 per cent. More than a fifth of our national wealth is tied up in housing.

Property owners have always enjoyed more wealth than renters, but that disparity has grown too. In 2019, their average net worth, at $685,400, exceeded that of renters by 29 times. As housing inflation has made property owners richer, many have leveraged that equity to buy more, concentrating more Canadian property in fewer hands. Multiple-property owners now own nearly one-third of homes in Ontario and B.C., and around 40 per cent in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Arguably, the downfall of our precarious system began in 2011, when the homeownership rate nationally peaked at 69 per cent. Or at some point in the years since, as housing prices in cities across Canada climbed to new heights of unattainability. But there’s another factor that has recently poured fuel on the flames, and turned a smoldering crisis, primarily in a few cities, into a nationwide wildfire: the pandemic.

*

In March of 2020, two things happened: across the country, people sheltered at home from COVID-19, and the Bank of Canada dropped interest rates from 1.75 to 0.25 per cent to quell the economic shockwaves by making it easier to borrow money. The CMHC, around the same time, warned that a pandemic-induced financial shock could cause home prices to plunge by up to 18 per cent, causing one-fifth of mortgage holders to default and triggering years of economic chaos. Many banks lowered mortgage rates below two per cent to bolster sales. In December of 2020, HSBC offered a variable mortgage rate of just 0.99 per cent, the lowest in Canadian history.

Instead of the predicted crash, the market exploded. Many Canadians struggled financially during the first year of the pandemic, but others took advantage of those low rates to go house shopping. As the rise of remote work loosened ties between urban cores and white-collar employees, many decamped from expensive regions in search of cheaper housing, spreading unaffordability outward. In the second half of 2021, more than 123,000 Canadians moved provinces—the highest rate of interprovincial migration since 1991.

What happened next was a nationwide game of musical chairs, as everyone stood up at the same time, looking for a new place to land. In Toronto and Vancouver, unremarkable homes routinely sold for half a million dollars or more over asking. Houses in Ontario’s cottage country went for double their listed prices. By March of 2022, Canada’s benchmark property price across the country was $861,000—28 per cent more than a year before, 54 per cent more than two years before and 130 per cent more than 10 years before. A detached house in a large city would set you even further back. In Vancouver, the benchmark price for a single-family house reached nearly $2.1 million.

For many hopeful buyers, this was when the music stopped and they found themselves without a place to sit. The hardest-hit communities weren’t the already unaffordable big cities, with their multi-million-dollar homes, but the smaller cities and towns upon which hordes of bargain seekers had descended. The result was a rapid distortion of local housing markets from coast to coast. In Chilliwack, a sleepy city in B.C.’s Fraser Valley, prices rose 40 per cent in 2021. New Brunswick’s price increases outpaced Ontario’s, up 25 per cent in 2021, with Prince Edward Island close behind. Millions of mostly young Canadians living in such places saw their long-standing expectations for homeownership vanish nearly overnight.

Because Canada has spent the past three-quarters of a century putting most of its housing eggs in the homeownership basket, the country hasn’t built enough new rental housing. Back in the 1940s, homeownership was supposed to be the engine that would drive the postwar economy, says Andy Yan, an urban planner and director of the city program at Simon Fraser University. “But we also introduced the belief that this was the only way to provide long-term housing for households.” In particular, the focus on building single-family homes—and protecting the wealth of their owners—led many cities to limit the construction of apartment buildings and reserve most residential land for detached houses, generating value for homeowners but dramatically restricting the supply of new rental housing.

New rentals instead are increasingly found in condos, owned by both corporate investors and independent landlords. They are, on average, much smaller than the purpose-built apartments of decades past, and often poorly suited to the needs of family life—the average new-build condo in Ontario today is only 700 square feet. Because the federal and provincial governments have mostly stopped building social housing, low-income tenants are often left competing with the growing ranks of frustrated prospective homeowners for the same rental stock. And mobility, the great purported advantage of renting, has disappeared as rents have risen. Renters are shackled in place not by a mortgage, but by the certainty that moving will mean paying far more every month.

GENERATIONAL LUCK

My parents were entering their 70s and thinking about downsizing out of their by then ultra-valuable home. The solution became obvious. After a year of cleaning, packing and renovating, they moved into the newly refurbished garden level. My husband and I moved upstairs, a few months before our daughter was born.

This living arrangement marks me as a member of an under-discussed demographic: the nepo babies of the housing market. Since 1977, homeowners have acquired more than $3.2 trillion dollars in wealth, which today is flowing downward to their children, amplifying inequality across generations. I’m grateful for my circumstances, but I know it has nothing to do with my own virtue or achievement. Canada’s housing market is no more meritocratic than a lottery—and some of us hold winning tickets printed long before we were born.

Shortly after moving, I noticed something striking about the neighborhood: there were no kids around. Or far fewer than there used to be, anyway. When I was young, there was always someone to play with at the park, and tiny princesses and superheroes crowded the streets at Halloween. Today, when I take my daughter to the playground, she’s often the only one there. It’s not just my imagination: in the past few years, my neighborhood has lost residents of all ages, and young ones especially. Since 2001, the number of children under 15 in the census tract surrounding my home has shrunk by 25 per cent. Vancouver overall is increasingly bereft of the very young, with fewer children per capita than any other Canadian city of more than 250,000 people.

This isn’t only my neighborhood, or my city. In 2021, there were 20,000 fewer children under 15 in the Greater Toronto Area than in 2016. Toronto proper has been losing kids for even longer, largely to cheaper cities. And as bargains become harder to find, there’s good reason to believe that the size and structure of Canadian families will change. One of the most widely cited studies on the relationship between homeownership and fertility comes from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research, which found in 2012 that a 10 per cent increase in housing prices led to modestly higher birth rates—but only for homeowners, who enjoyed a bump in their net worth.

Birth rates fell among renters. Consider that homeownership among Canadians of child-rearing age is rapidly declining, and the implications become clear. In 2011, 44 per cent of people 25 to 29 were homeowners; by 2021 that had declined to 36.5 per cent. In B.C. and Ontario, our most expensive provinces, the data shows that people wait longer than elsewhere to have children—in B.C., the average age at which women bear their first child is 31.6, the highest in the country.

Falling birth rates and aging cities mean more than empty playgrounds. They mean, over time, added stress on a labor market that will stagger under the burden of an older population. And they mean reduced tax revenues thanks to a shrinking working-age population, even as the costs of health care and pensions go up.

Ashley Jardine is one young parent who had to choose between space for a growing family and life in the city. In March of 2020, at 34 years old, she and her partner moved to Bowen Island, a 20-minute ferry ride from Vancouver, where they could afford to size up from a one-bedroom loft to a rented house, with room for two young kids and a rambunctious dog. They fell in love with the folksy island community and worked hard to save a down payment for a home there.

But here the same old story repeated itself. By the following spring, prices had risen well over 30 per cent, and their landlords seized the hot market to sell. They offered Jardine the chance to buy the house privately, but she couldn’t afford the $850,000 asking price. Even that was a bargain, with most houses on the island selling for more than $1 million. They found another rental, but they know that isn’t a permanent situation either. Today, a sense of precariousness looms over the family’s otherwise idyllic situation.

And as a renter, Jardine senses an invisible wedge between her family and the neighbors. She wonders why she’s putting so much into a community she knows she’ll one day be forced to leave: “I feel a kind of desperation. And I’m also very bitter about it. I don’t want to go.”

That bitterness is not unique to her. In May of 2023, a survey conducted for the Globe and Mail found that more than half of respondents between 20 and 40 were “angry” or “furious” about the housing market. Alex Ullman, describing the way investors have gobbled up new housing in Waterloo, keeping out prospective young buyers like himself, echoed that outrage. “It pisses me off,” he says.

A TD Economics report released last year made starkly clear the consequences for individuals and families of this growing division. “Wealth inequality in Canada is not just a story of rich versus poor, it is one of homeowners versus non-homeowners,” the authors wrote. “With affordability now at its worst level in decades, the current generation of prospective homebuyers is facing the fate of missing out on housing wealth.” That wealth is a key instrument by which Canadians have—by design, since the 1940s—built their financial security.

“Even someone who owns a 450-square-foot apartment has access to all these tools that a renter doesn’t,” says Andy Yan. Consider, he says, the tax credits and forgivable loans the government lavishes on buyers for renovations. Or the fact that a home is one of the few investments Canadians can sell without paying capital gains tax. There’s also the small fortune available to many owners in home equity credit, and, of course, the equity itself.

Economists and personal finance experts have long warned that our over-reliance on a single asset for financial security invites disaster, especially in a crash. The effort we put into building housing equity may be better invested in the stock market, some argue. But with the dramatic escalation of rents, it’s hard to imagine that very many of those households shut out of homeownership have enough money to pay rent and invest as much as they’d otherwise spend on a mortgage.

As the promise of homeownership is denied to Canadians, new fractures will grow: between young and old, between neighbors, between regions and between political factions. That frustration Alex Ullman and countless others feel will boil over in a hundred different ways. It already has.

You can see it in the way it has inflamed tensions between provinces, as homeowners from more expensive areas flock to cheaper ones. Nearly 89,000 Ontarians left that province in the first years of the pandemic, many in search of cheaper housing, driving up unaffordability elsewhere and stoking resentment against perceived interlopers. One Toronto couple, who started a TikTok to document their renovation of a Victorian house in Nova Scotia—after selling a 490-square-foot Toronto condo—garnered furious messages from some locals. “Congratulations, you’re what every single Nova Scotian hates right now,” went one missive. “Thanks for destroying our home.”

“We’ve screwed over young people, and we’ve screwed over newcomers of every age,” says Kershaw. “The group we need to tap into is the older demographic, who have been securely housed and made wealthier. We need to have a moral conversation about what it means to be on the sidelines.”

Otherwise, the outcome is clear. More and more Canadian neighborhoods will begin to resemble mine: quiet and lonely communities accessible only to the privileged few who have already acquired or inherited housing wealth, and who seek to get richer still. Ultimately, all of us will pay the price.

https://macleans.ca/longforms/the-end-of-homeownership/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

a Calgary suburb; Rocky Mountains in the background

Oriana:

Inheritance makes a huge difference. On the other hand, these days parents may live to a very old age, and while they (the parents) may have started living in their own house almost as soon as they got married, today’s prices of real estate are beyond the reach of the average young couple. Delaying child-bearing while waiting for the parents to die is not a healthy situation.

Charles:

The housing shortage won't last forever. as population decreases more and more homes will become available at lower costs.

Oriana:

Perhaps, but not within our lifetime. Also, houses take a lot of maintenance. I wouldn't be surprised by a shift toward more rentals, away from single-family homes. The boomer generation still enjoys a luxury that will become more and more scarce. We are already witnessing young couples (and affluent singles) populating the once-abandoned downtowns. And those urban condos and apartments show no sign of getting less expensive. Alas, it's always location, location, location.

Also, the population will not shrink all that much given the influx of immigrants, needed as labor force. And once you have apartment buildings, you don't demolish them in order to build single units. America is still living their fairy-tale, but it won't last forever. City space is too valuable.

Mary:

*

GOBEKLI TEPE, 6,000 YEARS OLDER THAN STONEHENGE

~ When German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt first began excavating on a Turkish mountaintop 25 years ago, he was convinced the buildings he uncovered were unusual, even unique.

Atop a limestone plateau near Urfa called Gobekli Tepe, Turkish for "Belly Hill", Schmidt discovered more than 20 circular stone enclosures. The largest was 20m across, a circle of stone with two elaborately carved pillars 5.5m tall at its centre. The carved stone pillars – eerie, stylized human figures with folded hands and fox-pelt belts – weighed up to 10 tons. Carving and erecting them must have been a tremendous technical challenge for people who hadn't yet domesticated animals or invented pottery, let alone metal tools. The structures were 11,000 years old, or more, making them humanity's oldest known monumental structures, built not for shelter but for some other purpose.

The stone tools and other evidence Schmidt and his team found at the site showed that the circular enclosures had been built by hunter-gatherers, living off the land the way humans had since before the last Ice Age. Tens of thousands of animal bones that were uncovered were from wild species, and there was no evidence of domesticated grains or other plants.

Schmidt thought these hunter-gatherers had come together 11,500 years ago to carve Gobekli Tepe's T-shaped pillars with stone tools, using the limestone bedrock of the hill beneath their feet as a quarry.

After a decade of work, Schmidt reached a remarkable conclusion. When I visited his dig house in Urfa's old town in 2007, Schmidt – then working for the German Archaeological Institute – told me Gobekli Tepe could help rewrite the story of civilization by explaining the reason humans started farming and began living in permanent settlements.

Carving and moving the pillars would have been a tremendous task, but perhaps not as difficult as it seems at first glance. The pillars are carved from the natural limestone layers of the hill's bedrock. Limestone is soft enough to work with the flint or even wood tools available at the time, given practice and patience. And because the hill's limestone formations were horizontal layers between 0.6m and 1.5m thick, archaeologists working at the site believe ancient builders just had to cut away the excess from the sides, rather than from underneath as well. Once a pillar was carved out, they then shifted it a few hundred meters across the hilltop, using rope, log beams and ample manpower.

Schmidt thought that small, nomadic bands from across the region were motivated by their beliefs to join forces on the hilltop for periodic building projects, hold great feasts and then scatter again. The site, Schmidt argued, was a ritual center, perhaps some sort of burial or death cult complex, rather than a settlement.

That was a big claim. Archaeologists had long thought complex ritual and organized religion were luxuries that societies developed only once they began domesticating crops and animals, a transition known as the Neolithic. Once they had a food surplus, the thinking went, they could devote their extra resources to rituals and monuments.

Gobekli Tepe, Schmidt told me, turned that timeline upside down. The stone tools at the site, backed up by radiocarbon dates, placed it firmly in the pre-Neolithic era. More than 25 years after the first excavations there, there is still no evidence for domesticated plants or animals. And Schmidt didn't think anyone lived at the site full-time. He called it a "cathedral on a hill”.