*

THOUGHTS

There’s something dangerous

In being with good talkers.

The fly’s stories of his ancestors

Don’t mean much to the frog.

I can’t be the noisy person I am

If you don’t stop talking.

Some people talk so brilliantly

That we get small and vanish.

The shadows near that Dutch woman

Tell you that Rembrandt was a good listener.

~ Robert Bly, Morning Poems

Rembrandt: Bathsheba

*

ENGLISH ROMANTICISM AND GERMANOPHILIA

~ In September 1798, one day after their poem collection Lyrical Ballads was published, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth sailed from Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, to Hamburg in the far north of the German states. Coleridge had spent the previous few months preparing for what he called ‘my German expedition’. The realization of the scheme, he explained to a friend, was of the highest importance to ‘my intellectual utility; and of course to my moral happiness’. He wanted to master the German language and meet the thinkers and writers who lived in Jena, a small university town, southwest of Berlin. On Thomas Poole’s advice, his motto had been: ‘Speak nothing but German. Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’

After a few days in Hamburg, Coleridge realized he didn’t have enough money to travel the 300 miles south to Jena and Weimar, and instead he spent almost five months in nearby Ratzeburg, then studied for several months in Göttingen. He soon spoke German. Though he deemed his pronunciation ‘hideous’, his knowledge of the language was so good that he would later translate Friedrich Schiller’s drama Wallenstein (1800) and Goethe’s Faust (1808).

Those 10 months in Germany marked a turning point in Coleridge’s life. He had left England as a poet but returned with the mind of a philosopher – and a trunk full of philosophical books. ‘No man was ever yet a great poet,’ Coleridge later wrote, ‘without being at the same time a profound philosopher.’ Though Coleridge never made it to Jena, the ideas that came out of this small town were vitally important for his thinking – from Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s philosophy of the self to Friedrich Schelling’s ideas on the unity of mind and nature. ‘There is no doubt,’ one of his friends later said, ‘that Coleridge’s mind is much more German than English.’

Few in the English-speaking world will have heard of this little German town, but what happened in Jena in the last decade of the 18th century has shaped us. The Jena group’s emphasis on individual experience, their description of nature as a living organism, their insistence that art was the unifying bond between mind and the external world, and their concept of the unity of humankind and nature became popular themes in the works of artists, writers, poets and musicians across Europe and the United States. They were the first to proclaim these ideas, which rippled out into the wider world, influencing not only the English Romantics but also American writers such as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman. Many learned German to understand the works of the young Romantics in Jena in the original; others studied translations or read books about them. They were all fascinated by what Emerson called ‘this strange genial poetic comprehensive philosophy’.

In the decades that followed, the Jena Set’s works were read in Italy, Russia, France, Spain, Denmark and Poland. Everybody was suffering from ‘Germanomania’, as Adam Mickiewicz, one of Poland’s leading poets, said. ‘If we cannot be original,’ Maurycy Mochnacki, one of the founders of Polish Romanticism, wrote, ‘we better imitate the great Romantic poetry of the Germans and decisively reject French models.’

This was not a fashionable craze, but a profound shift in thinking, away from Isaac Newton’s mechanistic model of nature. Despite what many people might think today, the young Romantics didn’t turn against the sciences or reason, but lamented what Coleridge described as the absence of ‘connective powers of the understanding’. The focus on rational thought and empiricism in the Enlightenment, the friends in Jena believed, had robbed nature of awe and wonder. Since the late 17th century, scientists had tried to erase anything subjective, irrational and emotional from their disciplines and methods. Everything had to be measurable, repeatable and classifiable.

Many of those who were inspired by the ideas coming out of Jena felt that they lived in a world ruled by division and fragmentation – they bemoaned the loss of unity. The problem, they believed, lay with Cartesian philosophers who had divided the world into mind and matter, or the Linnaeun thinking that had turned the understanding of nature into a narrow practice of collecting and classification. Coleridge called these philosophers the ‘Little-ists’. This ‘philosophy of mechanism’, he wrote to Wordsworth, ‘strikes Death’. Thinkers, poets and writers in the US and across Europe were enthralled by the ideas that developed in Jena, which fought the increasing materialism and mechanical clanking of the world.

So, what was going on in Jena? And why was Coleridge so keen to visit this small town in the Duchy of Saxe-Weimar that had become a ‘Kingdom of Philosophy’? Jena looked unassuming and, with around 4,500 inhabitants, it was decidedly small. It was compact and square within its crumbling medieval town walls, and it took less than 10 minutes on foot to cross. At its center was an open market square, and its cobbled streets were lined with houses of different heights and styles. There was a university, a library with 50,000 books, book binders, printers, a botanical garden and plenty of shops. Students rushed through the streets to their lectures or discussed the latest philosophical ideas in the town’s many taverns. Tucked into a wide valley and surrounded by gentle hills and fields, Jena was lovingly called ‘little Switzerland’ by the Swiss students.

Back in the 18th century, Jena and its university had been part of the Electorate of Saxony but, because of complicated inheritance rules, the state had been divided up and the university was nominally controlled by no fewer than four different Saxon dukes. In practice, it meant that no one was really in charge, allowing professors to teach and explore revolutionary ideas. ‘Here we have complete freedom to think, to teach and to write,’ one professor said. Censorship was less strict compared with elsewhere, and the scope of subjects that could be taught was broad. ‘The professors in Jena are almost entirely independent,’ Jena’s most famous inhabitant, the playwright Friedrich Schiller, explained. Thinkers, writers and poets in trouble with the authorities in their home states came to Jena, drawn by the openness and relative freedoms. Schiller himself had arrived after he had been arrested for his revolutionary play The Robbers (1781) in his home state, the Duchy of Württemberg.

On a lucky day at the end of the 18th century, you might have seen more famous writers, poets and philosophers in Jena’s streets than in a larger city in an entire century. There was the tall, gaunt-looking Schiller (who could only write with a drawer full of rotten apples in his desk), the stubborn philosopher Fichte, who put the self at the center of his work, and the young scientist Alexander von Humboldt – the first to predict harmful human-induced climate change. The brilliant Schlegel brothers, Friedrich and August Wilhelm, both of them writers and critics with pens as sharp as the French guillotines, lived in Jena, as did the young philosopher Friedrich Schelling, who redefined the relationship between the individual and nature, and G W F Hegel, who would become one of the most influential philosophers in the Western world.

Also in Jena was the formidable and free-spirited Caroline Michaelis-Böhmer-Schlegel-Schelling. She carried the names of her father and three husbands, but she was fiercely independent and had no intention of living according to social conventions. The young poet Novalis, who had studied in Jena, regularly visited his friends there from his family estate in nearby Weißenfels. In the winter months, you might have glimpsed Germany’s most celebrated poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, as he skated on the river – his bulging belly buttoned together with a flowery waistcoat. Older and more famous, Goethe became something like a benevolent godfather to the younger generation. He was inspired, even rejuvenated, by their new and radical ideas, and they, in turn, worshipped him.

These great thinkers attracted students from across Germany and Europe to Jena. Starstruck to see so many famous poets and philosophers sitting in one row at the concerts in the Zur Rose tavern, they couldn’t believe their eyes when seemingly all of Germany’s greatest minds squeezed into one room at a party.

Each of these great intellects lived a life worth telling, but the fact that they all came together at the same time in the same place is even more extraordinary. That’s why I’ve called them the ‘Jena Set’ in my book Magnificent Rebels (2022).

In an age when most of Europe was still held in the iron fist of absolutism, the Jena Set were united by an obsession with the free self. ‘A person,’ Fichte shouted from the lectern during his first lecture in Jena in 1794, ‘should be self-determined, never letting himself be defined by anything external.’ Fichte’s philosophy promised freedom at a time when German rulers presided over the smallest details of their subjects’ lives with an authoritarian delight – refusing marriage proposals, arbitrarily raising taxes, or selling their subjects as mercenaries to other nations. They were the law, police and judge rolled into one.

For centuries, philosophers and thinkers had argued that the world was controlled by a divine hand – but now, Fichte said, there were no absolute or God-given truths, certainly not safeguarded to princes and kings. The only certainty, the fiery philosopher explained, was that the world was experienced by the self. The self (or the Ich, in German), ‘originally and unconditionally posits its own being’ – it basically brings itself into existence. And through this powerful initial act, it also conjures up Fichte’s so-called non-Ich (the external world). According to Fichte, the reality of the external world was simply transferred from the Ich to the non-Ich. This didn’t mean that the Ich creates the external world, but that it creates our knowledge of the world. By making the self the first principle of everything, Fichte recentered the way we understand the world. Not only was the self the ‘source of all reality’, but it was imbued with the most exciting of all powers: free will and self-determination.

Fichte’s Ich-philosophy was lit by the fire of the French Revolution. When the French revolutionaries denounced aristocratic privilege and declared all men equal, they promised a new social order, grounded in freedom. ‘My system is, from beginning to end, an analysis of the concept of freedom,’ Fichte declared: ‘Just as the French nation is tearing man free from his external chains, so my system tears him free from the chains of things-in-themselves, the chains of external influences.’

These ideas were so radical and influential that these few years in Jena became the most important decade for the shaping of the modern mind and our relationship to nature. The story of the Jena Set is one of radical ideas – ideas about the birth of the modern self and the importance of Romanticism – but it also plays out like a soap opera as the young men and women broke conventions and used their own lives as a laboratory for their revolutionary philosophy. They placed a free and emboldened self not only at the nexus of their work but also at the center of their lives. Their lives became a stage on which to experience the Ich-philosophy.

There were passionate love affairs, scandals, and fights with the authorities. Caroline Schlegel, for example, widowed at 24, hung out with German revolutionaries and was imprisoned by the Prussians for being a sympathizer of the French Revolution. In prison, she discovered that she was pregnant after a one-night stand with a young French soldier. After her imprisonment, she was treated like an outcast, but the young writer August Wilhelm Schlegel came to her rescue: he married her, gave her a new name and, with that, a new beginning. The Schlegels had an open marriage, which Caroline explained was ‘an alliance that between ourselves we never regarded as anything but utterly free’. Both of them had lovers. When Caroline fell in love with Friedrich Schelling, 12 years younger than she, Schlegel didn’t mind. In fact, he joked: she ‘isn’t done yet … her next lover is still wearing a little sailor suit!’

The Schlegels were not the only ones who had come to such an unusual arrangement. The Humboldts also had an open marriage and Caroline von Humboldt’s lover moved in with the couple; Goethe lived with his mistress; meanwhile, Friedrich Schlegel outraged the literary establishment and polite society by taking readers into his bedroom to watch him and Dorothea Veit make love. Schlegel had intended to shock, and succeeded. ‘I want there to be a real revolution in my writing,’ he told Caroline.

The group met almost daily. ‘Our little academy,’ as Goethe called it in the spring of 1797, was very busy. They composed poems, translated great literary works, conducted scientific experiments, wrote plays, and discussed philosophical ideas. They went to lectures, concerts and dinner parties. They were interested in everything – art, science and literature. They were thrilled by this communal way of working. As the poet Novalis explained: ‘I produce best in dialogue.’ They called this way of working ‘symphilosophising’, a new term they had invented. They added the prefix ‘sym-’ to words such as philosophy, poetry and physics – it essentially meant ‘together’. ‘Symphilosophy is our connection’s true name,’ Friedrich Schlegel said, because they believed that two minds could belong together.

They often met in Caroline’s sunlit parlor on the ground floor of the Schlegel house near the market square. Caroline had no interest in playing the domestic wife. She simply served some gherkins, potatoes, herrings and a tasteless soup. No one complained. The flavor, one visitor said, was not provided by the ingredients of the meal but by the intellectual menu that Caroline prepared.

Caroline Michaelis-Schlegel-Schelling

Caroline Schlegel steered discussions, demanded opinions and her sharp analytical mind shaped the friends’ thinking. She awakened Friedrich Schlegel’s interest in ancient Greek poetry, for example, editing his essays, suggesting books and teaching him about strong female figures in ancient mythologies. ‘I felt the superiority of her mind over mine,’ he admitted, adding ‘she made me a better person.’ Caroline’s opinions about poetry, Friedrich Schlegel told his brother August Wilhelm, were illuminating, and her passionate support for the French Revolution was infectious.

Caroline also wrote many reviews under her husband’s name, and August Wilhelm Schlegel counted on her literary contributions. Together, they produced the first major German verse translation of Shakespeare, translating 16 plays in six years. It was a close collaboration, with August Wilhelm translating and Caroline scanning the verses in a kind of chant. Their Shakespeare is, to this day, the standard edition in Germany, but her name is still missing from the cover.

August Wilhelm Schlegel’s published lectures on Shakespeare also resurrected the playwright in England. In the 18th century, Shakespeare had become unpopular with critics who described his language as disordered, ungrammatical and vulgar. Voltaire, for example, had declared Hamlet ‘the work of a drunken savage’. For the Jena Set, though, William Shakespeare was the epitome of the ‘natural genius’, the quintessential romantic writer. In contrast to the polished refinement of the French dramatists Jean Racine and Pierre Corneille, who had followed rigid rules, Shakespeare’s plays were emotional and his language unruly and organic – ‘the spirit of romantic poetry dramatically pronounced’. English poets and writers, such as Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Hazlitt and Thomas Carlyle, all read and admired August Wilhelm’s Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature (1809-11). Wordsworth, said Coleridge, had declared that ‘a German critic first taught us to think correctly concerning Shakespeare.’

August Wilhelm Schlegel

At the end of 1797, Friedrich Schlegel convinced his brother August Wilhelm, his sister-in-law Caroline Schlegel and his friend Novalis that they should publish their own literary magazine. It would be of ‘sublime impertinence’, he announced, and they would fight the literary establishment. They called it the Athenaeum, a title that stood for learning, democracy and freedom. Caroline was its editor. Printed on cheap paper without any illustrations, the Athenaeum might have appeared unassuming, but its content was the Jena Set’s manifesto to the world. It was in the pages of the Athenaeum that they first used the term ‘romantic’ in its new literary meaning, launching Romanticism as an international movement. They provided its name and purpose but also its intellectual framework – it was ‘our first symphony’, as August Wilhelm said.

Today, the term ‘Romanticism’ evokes images of lonely figures in moonlit forests or on craggy cliffs – as expressed in Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings – as well as artists, poets and musicians who emphasized emotion and longed to be at one with nature. Some say the Romantics opposed reason; others simply think of candlelit dinners and passionate declarations of love. For the Jena Set, though, Romanticism was something much more complex and radical. Romantic poetry, they said, was unruly and dynamic – a ‘living organism’. They wanted to romanticize the entire world. They strived to unite humankind and nature, art and science. If two elements could create a new chemical compound, so Romantic poetry could bring together different disciplines and subjects, and weld them into something new. ‘By giving the commonplace a higher meaning,’ Novalis said, ‘by making the ordinary look mysterious, by granting to what is known the dignity of the unknown and imparting to the finite a shimmer of the infinite, I romanticize.’ And for that, the friends insisted, one needs imagination.

They elevated imagination as the highest faculty of the mind. They didn’t turn against reason, but believed it insufficient to understand the world. For centuries, philosophers had mistrusted imagination, believing it obscured the truth. The British writer Samuel Johnson had called it ‘a licentious and vagrant faculty’, but the Jena Set believed that imagination was essential for the process of gaining knowledge. Novalis announced that ‘the sciences must all be poeticized’, and scientist Alexander von Humboldt believed that we had to use our imagination to make sense of the natural world. ‘What speaks to the soul,’ he said, ‘escapes our measurements’.

At the center of Romanticism were aesthetics, beauty and the importance of art – terms which, for the Jena group, carried a deeply political and moral meaning. They had all initially embraced the French Revolution but, as hundreds of heads rolled off the guillotines during Maximilien Robespierre’s Reign of Terror, many Germans became horrified. By 1795, Friedrich Schiller was arguing that the Enlightenment’s enshrinement of reason over feeling had led to the bloodshed of the French Revolution. Rational observation and empiricism might have encouraged knowledge, but they had neglected the refinement of moral behavior. All the knowledge in the world could not foster a person’s sense of right and wrong: it might give them the ability to understand natural laws or make medical advances such as smallpox inoculations, even inspire them to wish for universal rights such as liberty and equality, but the horrific excesses of the French Revolution were bloodied proof that this was not enough.

*

Societies in Europe were driven by profit, productivity and consumption. ‘Utility is the great idol of our time,’ Schiller bemoaned, ‘to which all powers pay homage.’ The arts had been pushed aside. In his ‘Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man’ (1795), Schiller claimed that only beauty would lead us towards ethical principles and make us morally mature, for beauty protected us against brutality and greed. Maybe the French had simply not been ready for freedom and equality, he suggested, because in order to be truly free, one had to be morally mature. He didn’t mean a morality such as fidelity to a spouse or an individual’s sexuality – because, in that department, the Jena Set definitely had some fun. What Schiller meant was the morality of a society that was ready to govern itself. The French Revolution and the ensuing atrocities had shown how urgent was the need for a philosophy of beauty. ‘Art is a daughter of freedom,’ Schiller said, and ‘it is through beauty that we reach freedom.’

The younger generation admired Schiller’s ideas. They believed, Friedrich Schelling said, in a ‘revolution brought about by philosophy’ – which is exactly what Schelling set out to do. At just 20, he had already published his first philosophical book, followed each year by another one. By 23, he was so famous that he became the youngest professor at the University of Jena in 1798, enthralling students with his revolutionary ideas. There was a ‘secret bond connecting our mind with nature,’ he said. Rather than dividing the world into mind and matter as philosophers had done for centuries, Schelling told his students that everything was entangled into one living organism.

His students were so enraptured that their letters home described an almost religious epiphany. Schelling’s new world was filled with a ‘new, warm, glowing life,’ wrote one: it was alive. Instead of a mechanistic world where humans were little more than cogs in a machine, Schelling conjured a world of oneness. The self was identical with nature, he insisted, and being in nature – be it in a forest or meadow, or scrambling up a mountain – was therefore always also a journey into oneself. ‘Since we find nature in the self,’ one of Schelling’s students concluded, ‘we must also find the self in nature.’ Schelling’s philosophy of oneness became the heartbeat of Romanticism, influencing the English Romantics and the American Transcendentalists both. It flared out of Jena into the wider world.

*

Schelling’s impact on Coleridge’s thinking is graphically illustrated by the changes the English poet made to ‘The Eolian Harp’, a poem he had originally written in 1795. After studying Schelling’s works intensely, Coleridge republished the poem in 1817 with these new lines to the second verse:

O! the one Life within us and abroad,

Which meets all motion and becomes its soul,

A light in sound, a sound-like power in light,

Rhythm in all thought …

After Coleridge learned German, he continued to read the works of the Jena Set. Though he studied Fichte’s Ich-philosophy, Coleridge was a ‘Schellingianer’, said one of his friends (who had studied under Schelling in Jena), someone who ‘metaphysicized à la Schelling’. So obsessed was Coleridge that he translated big chunks of Schelling’s work, then passed them off as his own. He was particularly fascinated by Schelling’s idea of the unity between mind and nature. Page after page, paragraph by paragraph, Coleridge inserted Schelling’s sentences into his literary autobiography Biographia Literaria, describing how he had moved from the materialistic view of British empiricists to German idealistic philosophy. A child of the Enlightenment, Coleridge had initially agreed with the empiricists that the mind was like a blank sheet of paper that filled up over a lifetime with knowledge that came from sensory experience alone. But, after studying the works of the Jena Set, he became a proponent of Idealism – a school of thought that believed that ‘ideas’ or the mind, not material things, constitute our reality.

When his Biographia Literaria was published in 1817, Coleridge’s friend Thomas De Quincey accused him of ‘bare-faced plagiarism’, insisting ‘the entire essay, from the first word to the last, is a verbatim translation from Schelling.’ But Coleridge did the same thing with August Wilhelm Schlegel’s Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, from which he imported long passages for his own Shakespeare lectures in London.

Having failed to travel to Jena in 1798, Coleridge, together with Wordsworth, finally met August Wilhelm Schlegel 30 years later in 1828. Showing off his German skills, Coleridge told August Wilhelm that never had any translation of any kind of work in any language been as great as his of Shakespeare. To which August Wilhelm pleaded: ‘Mein lieber Herr, would you speak English? I understand it; but your German I cannot follow.’ Percy Bysshe Shelley, too, studied August Wilhelm Schlegel’s work. In March 1818, as he and his wife Mary Shelley were traveling through France to meet Lord Byron in Switzerland, he read aloud Schlegel’s Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature for six long days.

Coleridge was not the only one to learn German in order to study the works of the Jena Set. The American Transcendentalists, who gathered in the small Massachusetts town of Concord in the 1830s and ’40s, were equally keen to master the language. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s elder brother had impelled him to ‘learn German as fast as you can.’ Reading lists included Goethe, Immanuel Kant, Fichte, Schelling and, later, Novalis and Humboldt. And those who couldn’t read German studied the works through English editions such as Madame de Staël’s bestselling book Germany (1810), Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria and Thomas Carlyle’s widely read essays, reviews and translations in Foreign Review and other journals.

Emerson’s library was filled with books by Goethe, Schiller, Novalis, Humboldt, Fichte, Schelling and the Schlegel brothers. His famous essay Nature (1836), which became the Transcendentalists’ manifesto, was deeply influenced by Schelling’s philosophy of oneness. Each leaf, crystal or animal was part of the whole, Emerson explained, ‘[e]ach particle is a microcosm, and faithfully renders the likeness of the world.’ We are nature, Emerson wrote, because ‘the mind is a part of the nature of things.’

Emerson’s friend Henry David Thoreau was equally immersed in the ideas coming out of Jena, and in particular Alexander von Humboldt’s work. He filled his journal with observations about the natural world – from the chirping of crickets and the effortless movements of fish to the first delicate blooms of the year. Thoreau’s daily entries record his visceral sense of his synchrony with nature and the changing seasons – or what he called the ‘mysterious relation between myself & these things’. At one with nature, he felt the unity the Jena Set had described. ‘Am I not partly leaves and vegetable mold myself?’ he asked in Walden (1854). For Thoreau, the study of nature ultimately became a study of his own self. After his years at Walden Pond, for example, he described a lake as ‘earth’s eye’ and, by looking into it, the ‘beholder measures the depth of his own nature’.

There were many other Jena acolytes: Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville. Poe’s last major work, for example, the 130-page prose poem Eureka (1848) was dedicated to Alexander von Humboldt, and a direct response to Humboldt’s international bestseller Cosmos (1845). It was Poe’s attempt to survey the Universe – including all things ‘spiritual and material’ – echoing Humboldt’s approach of including the external and the internal world. Like Coleridge, Poe also lifted several pages from August Wilhelm Schlegel’s Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature, and published them verbatim under his own name. Whitman’s poetry collection Leaves of Grass (1855) is another example of the Jena Set’s international appeal. Whitman thought of it as a poetic distillation of the ‘great System of Idealistic Philosophy in Germany’. In one poem, he introduced himself as ‘Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos’ – perhaps a nod to Humboldt’s Cosmos, which the poet reportedly kept on his desk as he composed Leaves of Grass.

Romantic poetry, August Wilhelm Schlegel had argued in Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature was ‘the expression of the secret attraction to a chaos … which is perpetually striving after new and wonderful births.’ It was a sentiment that appealed to American Transcendentalists and British Romantics alike, just as much as Schelling’s unity of mind and matter, and Humboldt’s concept of nature as a living organism.

Jena’s intellectual reign was brief and vital, and its influence was lasting. The Jena Set put the self at the center of their thinking, redefined our relationship with nature, and heralded Romanticism as an international movement. These ideas have seeped deeply into our culture and behavior: the self, for better or worse, has remained center stage ever since, and their concept of nature as a living organism is the foundation of our understanding of the natural world today. We still think with the minds of these visionary thinkers, see with their imaginations, and feel with their emotions.

https://aeon.co/essays/english-romanticism-was-born-from-a-serious-germanomania?utm_source=Aeon+Newsletter&utm_campaign=d48f193f8f-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_12_21_12_49&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-d48f193f8f-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D

William Thomas Sherman:

The fundamental problem with romanticism and transcendentalism as philosophy is its almost complete ignoring of the issue and existence of evil (and I mean hard core, truly diabolical evil), and, whether intentionally or no, their simply leading to a moral relativism that either ignores evil or else is incapable of dealing with evil realistically. If the world is ALL ONE (as some of them averred Spinoza-like), then are we to assume evil has a rightful place in it? And if so, does that mean we, like Goethe’s Faust, simply make a deal with it?

William Taylor:

As I see this central role of the Self, my first thought is, did this movement lead to the blind, selfish instinct of mere egotism? Some of the article seems to say it did. Not much progress there, in my mind. Or was it individualism, which is at the root of much of our social tragedy today, as expressed in a narcissistic fool like Donald Trump? All the ecstasy and enthusiasm expressed in this article falls to nothing if it erases social connections and a sense of the common good. The author says all this eventually spawned Emmanuel Kant. Now there is progress. We end up trapped in our minds, unable to establish any real contact with the outer world, the world of phenomena. Difficult to develop any real oneness with nature within that context.

Franca Collozo:

The Sturm und Drang (storm and impetus) was one of the most important German cultural movements and dates from 1765 to 1785. The name derives from the drama Wirrwarr (chaos), published in 1776 by Friedrich Maximilian Klinger. [Oriana: I lean to translating Sturm und Drang as Storm and Drive]

Sturm und Drang contributed, together with Neoclassicism, to the birth of German Romanticism, and, together with Neoclassicism and Romanticism, represents a cultural movement often referred to as the ‘Age of Goethe’ (1749-1832), a term coined, in 1830, from the German Heinrich Heine.

In this way, the very famous cult of genius developed more and more and one of the first figures identified with this ideal was William Shakespeare. The opposite, therefore, of the cold and academic imposition of norms and rules.

The Sturm und Drang was also a political movement, since the bourgeoisie, in opposition to the nobility, chose nationalism against the cosmopolitanism of the nobility, thus preferring the culture of the people over that of the literary tradition.

All this profoundly characterized European culture, spreading from Germany to France and Italy, spreading like wildfire in all European countries, with a greater or lesser impact also on the various social structures. Surely, the patriotic and nationalist uprisings, in particular the Italian Risorgimento, took their cue from the same impetus that distinguishes the hero, a brilliant figure or patriot with a noble soul and a vocation for sacrifice. “Historia docet”.

Mary: THE ROMANTIC HERO WAS ESSENTIALLY AN OUTLAW

The Romantics' rejection of a clockwork world, operating on fact and reason, was indeed more than a change in style and fashion. Remember the execution of the British king under Cromwell was then reversed and the monarchy restored...there was little taste for the disorderly horrors of revolutionary change. A century later the American and French revolutions rode on a wave of cultural changes there was no turning back from. The influence of revolutionary thought and action cannot be ignored, it permeated international culture, society and the arts. Nature was no longer an object to be tamed and exploited, but the source of inspiration, the means to spiritual evolution, the vital connection between the individual and the living universe. The wild, majestic, mysterious, untamed, disordered and sublime world of nature was part of the human soul as well as its origin and home.

This is both the magical generative and liberating force of Romanticism and its essential fault. Romanticism does have a problem with evil from its very inception. Think of the Romantic ideal as seen in how they elevated and admired Milton's Satan, think of Heathcliff in Bronte's Wuthering Heights. The Romantic hero, in all his wild splendor, is a source of pain, destruction and chaos. He approaches the kind of terror nature can inspire, irresistible beauty, indiscriminate power to destroy. It's dangerous to fall completely under his spell, dangerous to ignore his disruptive power, his rejection of the fetters of established law. The Romantic hero is essentially an Outlaw, and we're still in love with him.

This was all evident even at the inception of Romanticism...so many were breathless admirers of the French revolution, the upset of an oppressive order, the promise of freedom, glorious and triumphant. Then the guillotine blade kept falling, more and more enemies were found, denounced, and executed. The Revolution was followed by the Terror, just as later revolutions would also be followed by reigns of terror.

Part of the problem is the difficult issue of balance, of creating an order that is not soulless and dead as clockwork, not oppressive and stifling to the individual, yet disallows extremes of action and thought that can threaten to devolve into chaos, rivers of blood, orgies of slaughter, genocides, mass starvation, and the elimination of dissent. Freedom becomes its opposite, still nominally in the service of a glorious, freer, better world. Think ideologues, tyrants, totalitarians, Robespierre, Hitler, Stalin, Mao — the end results of Heathcliff and Satan. Fatal glories.

Oriana: ADOLESCENTS ASPIRING TO BE SOLITARY HEROES

Romanticism as a precursor of fascism, with its cult of the Great Man, an Übermensch beyond good and evil — certainly the dark side of Romanticism can’t be denied. But mostly we think of the marvelous works of literature, art, and music. Yes, there is something adolescent in the cult of feeling, passion, wilderness. The creators of Romantic art were . . . so young. Still untouched by the diminishing perspectives of growing older. Still full of hope, still imagining themselves destined to be solitary heroes. The compromises required when working as part of a team were distasteful to them. They failed to see how even a “solitary” work of art is in fact a product not of a single inspired mind, but of a complex collective culture.

But adolescents often stylize themself as misunderstood loners. It’s part of the cult of feeling — you have to have enough solitude to process your emotions. As you said, the question of balance is difficult and crucial at the same time. Anything taken to an extreme usually ends up as evil, out of touch with the lives of others. The adolescent contempt for those prosy others must be overcome. Fortunately we can enjoy romanticism in the arts without needing to emulate the dubious romantic hero.

The idea that we are here to be useful, to be of service to others, and to build a common good seems strangely absent . . . That too can be taken to harmful extremes — think of Tolstoy in his last years. I suspect the enemy is simply extremism, no matter where we start. “Metron ariston,” the ancient Greeks counseled — moderation is best.

*

PREDICTIONS FOR 2023 MADE IN 1923

~ Forget flying cars. When scientists and sociologists in 1923 offered predictions for what life might look like in a hundred years, their visions were more along the lines of curly-haired men, four-hour workdays, 300-year-old people and "watch-size radio telephones."

That's according to Paul Fairie, a researcher and instructor at the University of Calgary who compiled newspaper clippings of various experts' 2023 forecasts in a now-viral Twitter thread.

They include projections about population growth and life expectancy, trends in personal hygiene, advances in industries from travel to healthcare and even some meta-musings on the future of journalism itself.

"In reading a forecast of 2023 when many varieties of aircraft are flying thru the heavens, we do not begin the day by reading the world's news, but by listening to it for the newspaper has gone out of business more than half a century before," wrote one newspaper (which was neither identified nor entirely off-base).

Paul Fairie thinks it's revealing that many of these century-old predictions were about things people worried about at the time and that remain a source of concern for some today.

For instance, predictions about men curling their hair appear to stem from "a general worry about anything that challenges gender norms," while talk of a four-hour workday is seemingly part of a larger conversation about the promise of automation.

Some predictions proved way more prescient than others (consider it a sliding scale between smartwatches and telepathy). Fairie says his big takeaway is "just to be modest about the certainty of predictions a century out.”

"If there's one thing I've learned from putting this together," he writes, "it's that I have absolutely no idea what a century from now will be like.”

Here's a selection of the — understandably rose-tinted — 2023 predictions he found, and how they panned out.

ADVANCES IN HEALTH AND BEAUTY

Several seers described a world full of healthier and more beautiful people (though only one explicitly linked those two ideas).

One writer predicted the eradication of cancer, as well as tuberculosis, infantile paralysis (also known as polio), locomotor ataxia and leprosy.

Another went with the headline "Fewer Doctors and Present Diseases Unknown; All People Beautiful.”

"Beauty contests will be unnecessary as there will be so many beautiful people that it will be almost impossible to select winners," they continued. "The same will apply to baby contests."

Some focused on the personal grooming and style trends that made up the standard of beauty itself.

One anthropologist, reportedly versed in masculine and feminine trends, declared "curls for men by 2023." A similar prediction appeared in the Savannah News, which also forecast that women will "probably" be shaving their heads.

"Also the maidens may pronounce it the height of style in personal primping to blacken their teeth," it added. "Won't we be pretty?”

LIVING LONGER AND WORKING SMARTER

Some newspapers predicted that the average person would live longer in 2023, though the exact amount varies based on whom you ask.

One said the average lifespan could reach 100 years, though certain individuals could make it to 150 or even 200. Another cited a scientist who put the average at 300 years.

For context, the expected lifespan of someone born in the U.S. decreased last year to 76.4 years — the shortest it's been in nearly two decades.

In another optimistic outlook, mathematician and electrical engineer Charles Steinmetz predicted that people would spend even less time working ("No More Hard Work By 2023!" that headline blared).

Steinmetz believed "the time is coming when there will be no long drudgery and that people will toil not more than four hours a day, owing to the work of electricity," the paper declared, adding that in his vision "every city will be a 'spotless town.'

And where exactly would all these people be spending their (long and leisurely) lives?

Several publications posited that technological and industrial advances would make more parts of North America more habitable, estimating the U.S. population at 300 million and Canada at 100 million in 2023.

Yes and no: The latest estimates from Worldometer put the U.S. population at 335 million and Canada at more than 38 million.

GIZMOS, GADGETS, AND OTHER INNOVATIONS

Naturally, there were also advances to dream about in science, technology, transportation, communications and other fields.

First, the products: One writer proposed that people will be wearing "kidney cosies," which they compared to teapot cozies for one's internal organs. Another posited that utensils and dwellings will be made largely of "pulps and cements."

Next, the flying: Aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss predicted that by 2023 "gasoline as a motive power will have been replaced by radio, and that the skies will be filled with myriad craft sailing over well-defined routes," which the Minneapolis Journal deemed "an attractive prophecy.”

Elsewhere, the opening of a new "Polar airline" was cheered for making it possible to fly from Chicago to Hamburg — via the North Pole — in just 18 hours (as opposed to the roughly 13 hours most direct flights take nowadays).

There was also considerable excitement about the prospect of wireless and paperless communications.

One writer envisioned a world in which Pittsburgh and London take orders "on talking films" from merchants in Peking, and "1,000-mile-an-hour freighters" deliver goods before sunset.

"Watch-size radio telephones will keep everybody in communication with the ends of the earth," they added, hitting the nail on the head.

Archibald Low — the British scientist and author who invented an early version of TV and the first drone, among other things — wrote that "the war of 2023 will naturally be a wireless war," thanks to "wireless telephony, sight, heat, power and writing.”

He went a step further, according to one newspaper account:

"Professor Low concludes that it is quite possible that when civilization has advanced another century, mental telepathy will exist in embryo, and will form a very useful method of communication.”

Low, an esteemed "futurologist" of his era, made many other — and more accurate — predictions about the 21st century.

They include the rise of smartphones and dictation, contemporary department stores, the internet and, arguably, British TV phenomenon Strictly Come Dancing.

https://www.npr.org/2023/01/02/1146569895/2023-predictions-from-1923?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Mary: THE FUTURE WILL BE DIFFERENT THAN WE CAN IMAGINE

While some predictions may come close to the mark, most do not, and what is most sure is that the future world will be very different than we can imagine. They may have come close with wristwatch radio/telephones, and shorter travel times through aviation, but quantum shifts have been much more difficult to foresee. You may very well have been able to see the development of more sophisticated calculating machines, but even in the early days of real computers it was impossible to see that computers, then taking up whole rooms, requiring special temperatures and the learning of special languages, would shrink to pocket size, and smaller, while their capacity would become immeasurably greater, and just about everyone would have one of their own, small, powerful, portable and connected to that other unimaginable development — the World Wide Web.

Technology transforms the world and how we live in profound and far reaching ways. This was always true. Electric light transformed how we live, work and sleep, changing patterns and habits that had been the same for most of our history. Industrialization transformed our relation to time — life’s rhythms dictated by shift work, time clocks, school room schedules.

Railways, and then automobiles, transformed landscapes and our experiences of distance, travel, and cities. Cars not only made the great interstate system possible, they made it necessary. Calamaties like storms, pandemics, new diseases, and our attempts to survive them, all shape the future in unexpected ways. Think of the social changes following the Black Death...revolutionary changes that made medieval social hierarchies, habits and thinking no longer possible. Similarly, our current pandemic is still in the process of changing how we work and how we live in cities. Big office buildings are standing empty as more and more work is done remotely, meetings done virtually, work done and delivered digitally.

These may lead to changes in many parts of daily living, from school to fashion, entertainment to medicine...change is the constant we can be sure of, and the pace of change is likely to increase. Old systems and old solutions become obsolete faster and faster. The possibilities are endless, and I envy those who will see them, the wonders we can barely imagine.

Oriana:

We need to bear in mind that technological and social changes are not 100% positive. You and I have both experienced medical personnel standing with their back to the patient, engrossed in filling out an overly detailed, mostly irrelevant computer chart. And there is much talk of robots taking the place of humans, with a strange absence of concern for what happens to the human need for connection in this brave new dehumanized world.

Somehow I don’t think the pendulum will swing back to more human interaction. But at some point there will be a reaction against anything pushed to an extreme. Yes, I too am inconsolable when I think of the fascinating changes I won’t live enough to see. But who knows? Something awful like a horrible war or a pandemic worse than covid may be already in the making. And no, nobody expected a lowly virus to disrupt our lives and change the nature of work. Nobody thought there could be a major war in Europe. Perhaps the most profound changes are always beyond what we can imagine.

The only thing I know for sure is that, for all our current problems, I am so glad not to have been born in the past — even fifty years earlier, much less one hundred or more. Some aspects of our era will no doubt be seen as barbarous — our homeless, our toxic medical treatments, the income inequality — but we can see progress nevertheless. Still a long way to go toward a truly civilized world.

*

WHAT THE RUSSIAN SOLDIERS ARE DYING FOR IN UKRAINE (Misha Firer)

~ That’s how many Russian soldiers, not counting PMC Wagner inmates and volunteers, died in Ukraine War in 2022.

What did they die for? It depends when they died.

In February, they died for de-nazification and de-militarization of Ukraine.

In March, they died “to stop the planned aggression in Crimea and Donbas.” Thousands perished defending Donbas hundreds of miles away in Kyiv, Chernihiv, Kharkiv.

In April, they died for de-Satanization of Ukraine.

In June-August, they died for “unacceptable security conditions.”

In September, they died because of “coup and NATO expansion to the east.”

In November, they died because “West is trying to drive Russia into a corner.”

In December, they died in an all-out war with NATO.

Cherepovetz, Vogoda oblast. Population: 315,000

That’s how many Russian people were wounded in Ukraine war. Thousands lost their limbs and will remain apartment-ridden for the rest of their lives.

Volgograd. Population: 1 million.

That’s how many people have left Russia in 2022 in two waves: right after the beginning of war, and after partial mobilization was announced. Among them — famous artists, doctors, IT specialists, civil pilots, and other high in demand professionals.

As the war drags on with no end in sight, most of them started building new lives abroad and won’t return.

Armed Forces mobilize the generation of the 1990s - early 2000s, which is the smallest segment of the demographics.

A little more than 2% of the young people of this generation have been mobilized and they will be targeted again in the second and third waves.

In addition, 2–3% of them have already left Russia, and more will leave. This will reduce the number of births by a few percent already starting next year.

Low fertility rates due to economic instability, dwindling population of the child-bearing age, and non-stop conveyor belt of war create a perfect storm for 2023.

At the end of his tenure, Vladimir Putin shot Russia in the head. It will take mighty efforts of millions of people to undo all the damage he has done and will do this year in pursuit of personal glory. ~

*

MISHA: “A 19TH CENTURY LAND GRAB”

~ Russia started its catastrophic war against its neighbor and once-brotherly nation under the stated goal of Ukraine's "denazification" — that is, wholesale regime change in Kyiv, the country's total subjugation to Russia and its effectively ceasing to exist as an independent state entity. Now, ten months later, that deliberately amorphous and pointedly meaningless justification of the unjustifiable has been replaced by the Kremlin propaganda's near-open admission of Russia's real — admittedly, a lot less toxically grandiose — ambition vis a vis Ukraine: to steal and try to hold on to more Ukrainian territory; yes, the crudely banal, brazenly imperialistic, 19th-century land grab.

How pathetic. More land? Why does Russian need more land? To befoul and make uninhabitable a few additional hundred thousand square miles of neighborly territory? Russia doesn't know what to do with the enormous excess of its own current territory as it is. This enormous, nightmarish surfeit of largely empty land, scarcely populated by impoverished, deeply unhappy people, has been the bane of Russia existence in the world throughout its history.

Yes, but it also happens to be the sole remaining source of Russian people's nationalistic pride: indeed, we know we are poor, miserable, backward, perennially angry and have no unifying purpose on Earth — but... But! We are by far the largest country in the world! Isn't that something? We have the greatest amount of landmass... which, in truth, we have no idea what to do with. And we want more land!

Yes! The more unmanageable, empty land we have, the better we feel about ourselves! Let people in some small European countries, Switzerland or Denmark or some such, enjoy their countless creature comforts and high incomes and wonderful living standards — those are not for us. We don't want to be a happy, wealthy small country. We don't need to have a good life — we wouldn't know how to go about having it. No. Just let us stand, fuming with diffuse resentment and looking about us in confusion, in the middle of our senseless eleven time zones. That's our lot in history. ~

Oriana:

It's super-human resilience that Ukrainians are managing among the rubble. Seems that Putin, seeing he can't conquer Ukraine, decided to turn it into rubble — to cause the maximum destruction he possibly can. Pure evil — after WW2, this just wasn't imaginable, we thought.

We underestimated how much history repeats itself after all. First Putin's small land grabs, ignored by the West. Then a shameless big grab. If victorious, it will be followed by another and another. Russia’s great dream is to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific (“from Lisbon to Vladivostok”). Barring that, at least restoring the Soviet Union, which would mean annexing the Baltics and other former republics, with puppets governments installed in Poland, Czechia, etc. It would be called “the Russian World.”

Russia is not a normal European country that left old imperialist ambition behind the way Sweden, for instance, did centuries ago. Or the way that the British Empire shrank to become the UK -- not even “Great Britain” any more. Funny, we never saw such developments as a collapse and resentment-breeding defeat. We saw them as a peaceful, orderly transition. But we don’t expect this from Russia. We expect violence and chaos, with the rich and powerful falling out of windows.

*

ANTI-SEMITISM IN THE SOVIET UNION

~ In the grander European scheme of things of the 20th century, the Soviet Union wasn’t particularly anti-Semitic. I’d rather say we were close to the middle of normal distribution.

The reason the USSR gained the notoriety as a flagship of anti-Semitism in Europe was our confrontation with Israel after their triumph in the Six-Day War in 1967. This gave rise to a wall of “anti-Zionist” propaganda, now enthusiastically recycled by many detractors of Israel in the West and the Middle East.

Soviet “anti-Semitism” is perfectly encapsulated in an apocryphal story about the witty British orchestra conductor Thomas Beecham. He had a conversation with a Communist minder of a Soviet cultural delegation visiting Great Britain in the late 1950s.

Soviet bureaucrat: “This talk about anti-Semitism in the USSR is absurd. Look at us, our orchestra has 30 Jews. How many have you got in yours?

Thomas Beecham: “No idea. Never occurred to me to count them.”

*

Jews were a late arrival to our part of the world. They came in a package with the part of Poland that we annexed at the end of the 18th century. From there anti-Semitism metastasized to the rest of Imperial Russia. In the early 20th century, the Black Hundreds

fused grassroot anti-Semitism with nationalistic imperial ideology, beating the Nazis to it by more than a decade.

A Black Hundred procession, 1907

But soon the Communist revolution happened.

An ambitious minority, the Jews played a central role in the victory of the Communists and the rebuilding of the country. This not least because they were almost 100% literate in the midst of a peasant country where most of the old educated classes were murdered, imprisoned or exiled.

Using their foreign contacts, they became prominent in building the OGPU/NKVD/KGB international spy network, the revolutionary cells of Comintern, and proliferating our agents of influence inside the movements for peace and disarmament. They also were very important in our education, science and research, and mass culture.

Great turnaround

In WW2, we played a unique role in saving Jews from annihilation at the hand of the Nazis. And yet, a few years after the victory the love story between Soviet rule and Jews took an abrupt end.

The state of Israel was formed. Despite our help and all the accumulated goodwill, they turned out to be staunchly Zionist. Stalin watched the loyalty of our own Jews to shift toward Israel — and considered this a treason. Preparations were made for a nationwide ethnic cleansing of Jews, just like what happened to ethnic Germans, Poles, Greeks, Chechens and other minorities before the war. Only Stalin’s death prevented it from happening.

Glass walls and ceilings

Yet, this opened the valve through which the grassroot anti-Semitism started to permeate the Soviet system from underneath. The “uncertain” loyalty of Jews led to an undeclared quota system and glass ceilings that barred them from many attractive careers. They kept inventing things, building weaponry and winning chess titles for Soviet rule — but among my 40+ strong class of International Journalism in the Moscow State University there was only one of them, and even he was only half Jewish.

Then I started my career in propaganda—and never did I meet a single Jew among the myriad of KGB and GRU spies either inside or outside of the perimeter. Pretty amazing, if you think about it, against the long list of Jewish operatives in the service of the Soviet Union before the war.

Foreign agents

By the time I entered the business of propaganda, the emigration of Jews had already picked enough steam to cause serious problems for the USSR internationally. The Refuseniks brought upon us a series of economic sanctions (Jackson–Vanik amendment). In the eyes of the mass of commoners this made even loyal Jews “foreign agents”. People were upset by the fact that the Jews were “privileged”: they were allowed to legally emigrate, while it was totally impossible for the rest of us.

Enter Russian ethnic nationalism, long suppressed by the Communists. By the 1980s, the Czarist-era narrative of “Jews hurting Russian people” resurfaced across all classes of society. Glasnost not only uncovered dirty secrets of Soviet rule. Anti-Semitic reading became kosher. Unlike the previous decades, by the late 1980s you as an upwardly-mobile Communist functionary no longer risked to taint your personnel file by publicly voicing anti-Semitic grievances.

No wonder hundreds of thousands of Jews headed for the exit once the perimeter became porous around 1988–89. The exodus also took in its wake many people from other ethnicities. Looking back, it’s easy to see how this drained the country of the future middle class, the backbone of a robust democracy and powerful civil society comparable to what Israel has built.

The current narrative of Russian nationalists about “Ukrainian Nazis and their Jewish masters” is a rehashed Soviet propaganda construct. ~

*

MORE ON THE SOVIET NOSTALGIA

~ Putin’s plan to rebuild USSR through invasion of Ukraine was a consensus of the silent majority, and handing Ukraine and Moldova on a silver platter in 2022 to his constituents would have skyrocketed Putin’s ratings.

That’s what Levada-Center, a Russian non-governmental research organization dubbed “foreign agent” indirectly concluded shortly before the beginning of the special military operation in Ukraine: 75% of Russians believed that the Soviet era was the best time in the history of the country, only 18% of respondents did not agree with this judgment.

The number of Russians who rate Russia as a great power was 64% vs 82% who rated the Soviet Union as a great power.

Putin could do no wrong with annexation of former Soviet republics — more annexations, more greatness in the hearts of the Russian people, more historical glory to him.

While 64% graded Russia as a great country, only 15% of respondents are satisfied with modern Russian healthcare.

They sincerely believe that hospitals without plumbing and unavailability of meds do not bear on the greatness of their country.

National greatness, therefore, is not measured in concrete terms like state of the art hospitals and longevity due to advanced meds but it is rather a wholly religious construct.

As of August 2020, Russians voted Military as the most trusted institution of power, well ahead of the President, at second place, the FSB (former KGB) and other political police entities at third. Russian Orthodox Church is at the fourth place (statehood is Russians religion, not Christianity).

Should one be surprised then that Putin stopped paying any attention to Russia’s economy ten years ago relegating that responsibility to prime minister while focusing almost entirely on making Russia great again through military conquest of territories of a sovereign state as the armed forces was the most trusted institution according to the vast majority of Russians?

The largest demonstration in the late Soviet period was not against USSR, the so-called “prison of peoples,” but for not letting the bankrupt Soviet Union fall apart.

Russians demanded to be kept in the prison indefinitely -- although they subsidized almost every republic and couldn’t even travel abroad without an exit visa -- they didn’t want to be let out!

It's a huge mistake to think otherwise! Mikhail Gorbachev is the most vilified leader in Russian history for a reason.

In 2012, before Putin transformed Russia into a totalitarian country, Levada asked respondents how they place freedom from the list of 12 common values. Freedom was voted exactly in the middle of this list, in sixth place.

In the first place were order and security followed by the rule of law. Third, human dignity, social justice, the desire to achieve more and personal responsibility.

This corresponds to my answer to my friend’s question how Putin managed to destroy freedom of speech in Russia: Russians didn’t value freedom of speech in the first place.

A thief always steals what’s the easiest to steal. Freedom was an easy steal as Russians didn’t care much for it.

Russians that I’ve spoken with do not understand why Ukrainians are dying for freedom.

To them, order and stability, even when ruled by a criminal gang are considerably more important, and they’d rather die for Putin, a guarantor of stability, than for freedom. ~ Misha Firer, Quora

Kenneth Coville:

“National greatness, therefore, is not measured in concrete terms like state of the art hospitals and longevity due to advanced meds but it is rather a wholly religious construct.”

It's the same for the “Make America Great Again” crowd. When you ask what Makes America Great it is never having a lower cost universal health care system, or having a living wage for all workers, or having adequate affordable housing for all, etc. It’s always about punishing persons different than themselves and maintaining a special status for their self defined group of adherents as in

“Jews will not replace us!”

and ironically to this thread

“I’d rather be Russian than Democratic”

etc.

*

PUTIN AT A CHRISTMAS SERVICE

~ Look at that bloodthirsty human insect. Scared for his useless, ugly life to the point of coming for the Christmas service in his house church all alone and just standing there in complete isolation, hoping God doesn't exist. ~ Misha Iossel

Place: the Kremlin Cathedral of Annunciation.

Anca Garcia (Facebook):

What

I dislike the most about him is his obvious hypocrisy. I saw a video of

this. As always, he is never still, looking around with the attitude of

a bored apparatchik who is there on official business, twitching and

turning with a face that says he is thinking of

something official and stringent. I just don't understand how they buy

it. He is obviously so fake in his religious sentiment, yet for some

reason nobody tells him how bad his attitude looks. You don't have to

watch the video. He is always that way. He is always awkward in

everything he does. What a despicable creature!

*

HOW ORDINARY RUSSIANS VIEW AMERICA

~ Ordinary Russians’ views and opinions on America are shaped by our wall-to-wall patriotic propaganda.

In their mind, the US very much reminds of how American Conservatives view their Libs. It’s a bunch of rich, arrogant d*cks who look for any opportunity to grab things at someone else’s expense. Despite their inflated sense of entitlement, they turn into whiny snowflakes the moment they face anyone tough—for example, Russia.

Through the lens of ordinary Russians, right now President Putin is busy cutting these guys down to size in Ukraine. Across the world, the silent majority holds their breath in the hope the Americans will be defeated in the end.

The way to greatness, the key to redemption for an average Russian is the mighty State (Derzháva). Without it, everything withers and crumbles in the end. Americans, in their unrelieved ignorance, are too dumЬ to see it.

[According to the Russian view,] American anti-Statism is part of the same global evil that inspired the Ukrainian Maidan revolution. ~ Dima Vorobiev

*

WHY COMMUNISM WAS DOOMED TO FAIL

~ First, the premise. “To each according to their needs, from each according to their abilities” sounds nice on paper and works well in fiction such as Star Trek’s utopian United Federation of Planets. In reality, us human beings are selfish bastards. Sure, some are more selfish than others, but self-preservation is a fundamental trait. The utopian “socialist man” exists only in the imagination.

There’s a reason why humans invented money and trade. Societies that pursue utopian ideals inevitably resort to coercion. If you do not measure up to their impossible standards, you are an enemy of the people or the community. You are, essentially, a criminal who needs to be controlled. Sure, some regimes might choose more benign means of control than others, say, fines and administrative action instead of incarcerating you to do forced labor in a re-education camp, but the end result is the same: the ideals of the regime are upheld through coercion and the regime necessarily becomes a police state, complete with a massive security force and a network of informants to weed out its perceived enemies.

Second, the planning. Oh, the basic idea is great. Markets react to the immediate. The economy is optimized “locally” (in a mathematical sense), short term, responding to the needs of the moment. It’s like trying to climb a hilly terrain at night, simply seeking the steepest slope: you find the highest spot in the vicinity, but it’s almost certainly not the tallest mountain peak of the land. Planning is like having a map of the whole countryside: you no longer rely on short-term, blind market forces but pursue long-term economic goals with full foresight of the consequences. Surely it is superior! Except… first, planners are not that smart. They may not understand all aspects of the economy. Most importantly, they often cannot foresee changes that are beyond their control. A natural disaster. An epidemic. A new discovery.

Say, you are an engineer at the #3 Car Factory of Capital City and come up with a new way to build automobiles. Cheaper, requiring less labor. But wait… what happens to the labor force? What happens to the raw materials you no longer need? The plans must be rewritten. Not just for the #3 Car Factory but entire sectors of the economy. You pull one string and the whole fabric unravels. No, comrade, we cannot allow you to implement your innovation. Maybe in the next Five-Year Plan. Surely you can’t expect us to redo years of planning work on a whim?

And there you have it. The result was the stagnation of the Brezhnev era. Life in most East Bloc countries was not horrible. Shortages were not rampant. Basic necessities, even some luxuries were available. There was some progress: more automobiles, new technologies slowly trickling in. But… life was… gray. We were condemned to live behind an Iron Curtain whose main function was not to protect us from evil Western imperialists but to prevent us from fleeing. And everything was second-rate. Our cars used the technologies of yesteryear. The infrastructure was old and ill-maintained. Things… just generally sucked. And the gap between East and West appeared to widen with each passing year.

Gorbachev, I suspect, understood this. Which explains his attempts at reform. But these attempts only hastened the collapse of the regime. I suspect that by the time he became the leader of the USSR, the regime was already irreversibly doomed. It was simply a question of whether it goes with a bang or a whimper, keeping in mind that a bang would have brought down much of the world along with it. Thanks to Gorbachev, we got a whimper, and it happened sooner than expected. I say we were lucky to have him, even if this wasn’t his intent when he embarked on his reform agenda. ~ Viktor T. Toth, Quora

*

It may be that in the future, 30 years from now or more, historians will write that although the USSR formally dissolved in 1991, it didn’t die as an idea until 2022. ~ Tomaž Vargazon

*

WHY THE SOVIET UNION COLLAPSED (Dima Vorobiev)

~ With the USSR, it’s like the Roman Empire: you can fill an entire library with books and articles explaining why it declined and crumbled, and not one of them would alone give a definitive answer. But one answer may give you an intuitive understanding of what all the other books in the library “The Rise and Fall of the USSR” contain:

The Soviet project lost its momentum.

A revolutionary undertaking like Communism must keep moving forward at any price. It’s exactly like riding a bike: once you stop, it’s only a matter of time before you fall.

Both Stalin and Trotsky were acutely aware of this, even though both attacked the issue from different angles. Mao Zedong knew this, as did Che Guevara. The real Communism, the way Lenin and Stalin implemented it, was based on a Raubwirtschaft [looting, kleptocracy] concept: you grab a resource, you use it to build economic strength and armed muscle, and then use it to move on the next resource.

During the Revolution ’17 and Civil war, the Bolsheviks grabbed the military, communication, transport, financial and mineral resources of the Russian empire.

They built their strength on that and moved in 1928–1933 on private peasants and the Church.

Having confiscated almost all private wealth in the country, the Bolsheviks used it to buy from the West and put into use the industrial and military backbone of the USSR that after WW2 brought into the realm of Communism almost all of East Asia and half of Europe.

Reparations after WW2 also brought to us vast financial resources and at least 5,500 new industrial objects confiscated in Manchuria, Germany and some other countries. We used it to assure our nuclear capability and achieve some spectacular breakthroughs in the space race and a major upgrade of many other industrial capacities.

And then it all slowly ground to a halt. Discovery of vast petroleum reserves in West Siberia helped us chug along for another two decades, but no more. We stopped, and everything came crashing down in 1991.

In retrospective, the poster below from 1983 was a premonition of the coming defeat. A young worker warns the US for their Strategic Defense Initiative (aka Star Wars): “Wouldn’t advise you to test our strength, Mister Reagan!” Despite the defiant text, the bellicose red and a wedge-like composition, a lot of things in this motif are alarmingly off, seen from the height of traditional Communist propaganda canon:

Communists never feared confrontation with the oppressive classes. On the contrary, we always challenged them to challenge us. Why such a reticence now?

There’s no weapons in the picture. Behind the man there are only the letters U.S.S.R. in Russian—formed like a Polish hussar’s wings, and probably as useless in a real fight.

The man’s clothes and hair suggest he’s a civilian. His posture in the one of a Hyde Park speaker, not a martial arts expert. His face is concerned, not threatening or scary. Does he even know how to disassemble and clean an AK-47?

The Pravda newspaper he holds in his fist—is this how he’s going to fight Reagan’s space ships?

The paper at the time consisted of three broadsheets (i.e. six pages), which means rolled tight into a paper stick it was laughingly flimsy against the New York Times rolled the same way.

No apparent heresy here, of course. It weaved into the overarching narrative of weakening the West through the Peace Movement and our agents of influence attached to it. However, all in all, the fact that such a poster was greenlighted by the Central Committee for internal use, somewhere on a propaganda meta-level definitely signaled: “The end is nigh, comrades!” ~

Translation:

“Wouldn’t advise you to test our strength, Mr. Reagan.”

“Raubwirtschaft” = plunder economy, sometimes also translated as “robber economy” or “kleptocracy.” The president is the thief-in-chief.

*

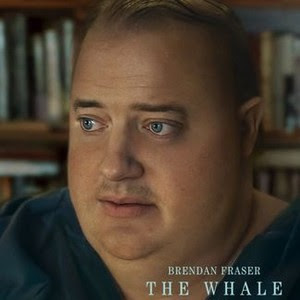

BEFORE YOU HAVE ANOTHER COOKIE, WATCH “THE WHALE”

~ The main character in "The Whale" is killing himself in the slowest, most painful way he can think of.

It's more a filmed play than a movie and no one would call it perfect for the holidays but "The Whale" is an unusual character portrait. Charlie is an online teacher who is confined to the apartment where the entire movie takes place. Weighing 600 pounds and with blood pressure double the recommended level, Charlie joylessly wolfs down a bucket of chicken, as if it's his job rather than dinner. But the ray of hope in Darren Aronofsky's adaptation of Samuel Hunter's play is when Charlie says, "I need to know I have done one thing right with my life.”

A series of people try to help Charlie. There's a nurse, played by Hong Chau, who gradually reveals other connections to her patient. There's his estranged daughter, who drops in to tell him to drop dead. There's the pizza delivery man, who speaks to Charlie through his door. And there's an evangelist who insists, "God brought me here for a reason.”

All of those characters have secrets, which is one way "The Whale" feels more theatrical than cinematic, along with the conveniently timed entrances and exits into the set — er, Charlie's apartment. Just about everything in "The Whale" feels like a metaphor, something that works better in the theater, but it poses a bunch of interesting questions that can be interpreted in wildly different ways.

For instance, is the nurse helping Charlie or, since she accedes to his wish to avoid hospitals and often brings food, is she enabling him? When the vituperative daughter betrays the evangelist, is it to help him or hurt him? Is the main character's problem mental illness or something more pervasive? Is a "Moby Dick" essay that Charlie loves (it gives the film its title) the key to the whole thing because of its insistence that everything can be interpreted at least two ways?

One thing there's no question about is Brendan Fraser's committed, award-worthy performance as sad, desperate Charlie. The extensive prosthetics he wears could be a distraction but they're not. Fraser's choices are so subtly intelligent that we barely notice what amounts to his costume, so attuned are we to the way his Charlie teeters on the brink of life and death. He's an angry, fearful character and, somehow, he seems to be trying to take control of the only thing within his grasp.

Anyway, that's how I see "The Whale," which plays out like a horror movie in which the villain is already inside the victim when we meet him. ~

https://www.startribune.com/review-brendan-fraser-is-an-oscar-frontrunner-in-the-whale/600237986/

MISERY PORN (from The Daily Beast)

~ Adapted from Samuel D. Hunter’s highly divisive play, the film stars Brendan Fraser as Charlie, a homebound 600-lb. professor attempting to reconcile with his estranged, cruel daughter (Sadie Sink) as he anticipates his death. Over the course of the film, we learn Charlie’s full heartbreaking situation: an affair with a male student that ended his marriage, the religious self-hatred that drove his lover to suicide, and Charlie’s feelings of guilt over his death. We are meant to see him more humanely than we did when we met him. But The Whale wants to put the audience and Charlie through the wringer.

Aronofsky is no stranger to depicting the human body horrifically, whether through the ravages of addiction in Requiem for a Dream or turning Natalie Portman into a bloody, horny swan. In terms of depicting a character’s willingness to commit self-harming acts at risk of their possible demise, The Wrestler might be Aronofsky’s empathic magnum opus.

Comparing that film (which shares copious parallels to The Whale, from father-daughter estrangement to the intended second coming of its star) to Aronofsky’s latest only further highlights the latter’s deficiency in this regard. The Wrestler’s Randy the Ram was a tragic figure who was given complicated dimension that makes us understand, and even love, him; Charlie in The Whale is granted complexity of pain, but not personhood.

The film would rather make Charlie a divine saint, willingly accepting his daughter’s constant epithets and speaking like a motivational cat poster (his hushed “people are amazing!” features prominently in the trailer) than a complete person. This makes the character as written feel hollow, no matter how charismatic the actor who plays him. Fraser is tasked with pulling our heartstrings throughout in a ceaseless torrent of tears, but he’s not given the luxury of an arc to play. The film might think it is distinguishing Charlie by his unconditional love, but Hunter’s script defines Charlie purely through his suffering.

The Whale also thinks its pleading for compassion, while stylistically enacting the opposite. Aronofsky and cinematographer Matthew Libatique shoot the film in the square Academy ratio (where the images you see are a claustrophobic box, rather than a wide rectangle to absorb more of the environment) so that Charlie’s body fills the frame. The film leers at his naked body while showering. Aronofsky plays a night of Charlie’s self-punishing binge eating like the stuff of a monster movie, complete with howls and lightning crashes.

The title itself is a troll, dodging a slur with the film’s flimsy allusions to both Moby Dick and the biblical Jonah. Meanwhile, Rob Simonsen’s boomingly mournful score projects all of the pitying emotions at us that the film demands we feel. Rather than creating authentic empathy from the audience, the film is more interested in making a spectacle of Charlie’s suffering and his body.

Why would the film do all this if it thinks it is operating from a place of compassion, or that it earns it from judgmental viewers? Is it because it is laying a trap for the kind of fat-hating judgment for Charlie it flatly assumes the audience possesses? If so, it illustrates why the film is so fundamentally compromised: It is utterly certain that no one in the theater could have compassion for Charlie before the film begins, let alone that someone like Charlie might be in the audience. All the film’s posturings towards empathy come out looking phony. ~

https://www.thedailybeast.com/obsessed/from-the-whale-to-the-son-the-year-movies-became-misery-porn?ref=author