Rabi’a al-Basri, writing in 717 ce: “Kings have locked their doors / and each lover is alone with his love. / Here, I am alone with You.”

my dream about the second coming

when Something drops onto her toes one night

~ Lucille Clifton

*

Paul Klee: City of Dreams

*

THOMAS JEFFERSON AS A WRITER

~ Colonial Americans, especially in Virginia and Massachusetts, were from the start sophisticated tellers of stories about themselves, their origins, their settlements, and their relationship to those who lived there before them, to the people, Red and Black, whom they subjugated or owned. Their stories were also about their connection to the mother country, Great Britain, from which most had come, stressing whom they owed their allegiance to and from whom they got the right to possess the land they had settled.

Usually they knew exactly what they were doing and why. Fact and fiction, reality and desire, action and thought, aspiration and imagination, history, natural science, and theology, the access through language to narrative patterns and claims were part of the American experience from the start. The earliest settlers of Virginia and Massachusetts began the making of American identity. Jefferson was one of its most gifted and influential storytellers.

In 1757, at the age of fourteen, Jefferson inherited a large share of the property his father had amassed, “the lands,” he later wrote, “on which I was born and live.” Peter Jefferson was the largest property owner in Albemarle County in west-central Virginia. A surveyor, cartographer, planter, and slave-owner, he had married upward. A native Virginian, he came from a moderately well-to-do but not wealthy family.

His wife, Jane Randolph, made him and their ten children, two of whom were sons, kin to one of the most influential families in the colony. Peter and Jane Randolph Jefferson’s children belonged to the privileged elite. Peter had an eye for wealth, power, and adventures, for settlement and expansion, and even for books, which his eldest son inherited. In his will, he made customary provision for his wife, his daughters, and his sons. It was an unusually equitable will for its time.

None of Thomas’s sisters inherited land. They inherited domestic slaves, a small amount of money, and their educations at the expense of the estate. Peter Jefferson’s wife got life tenancy of the family home, Shadwell, about three miles from the small village of Charlottesville. The will provided that each son should inherit either one of two large properties, one on the Fluvanna River, about 2,300 acres, the other on the Rivanna River. The Rivanna land, including Shadwell, was on the southern part of the lower ridge of the South Mountains, which ran north to south for about eighty miles, about thirty miles east of the Blue Ridge. Its highest point was almost 1,500 feet above sea level. As the first son to come of age, Thomas chose the land on the Rivanna, about five thousand acres.

*

Rain dripped through the roof of a plantation called Fairfield into the room in which nineteen-year-old Thomas Jefferson was sleeping. It was Christmas Day 1762. He was two years away from coming into his inheritance. He awoke to find his pocket watch, which he had placed by his bedside, floating in water. His “poor watch,” he jokingly complained to his closest friend, John Page, “had lost her speech.” It had also lost a representation, probably a silhouette, of a young lady he was passionate about. His wallet, stored for the night a foot from his head, had also been attacked. It had been eaten through by rats.

Christmas Day was not a religious day in Church of England Virginia. It was a day of social celebration. The first thing on the young man’s mind that morning was his need to communicate with his good friend. One of the first things in his hand, other than the “poor watch” that he rescued, was his pen. He had a story to tell and a state of mind to write about. The rain and rats didn’t spoil his humorous, satirical, and self-revealing mood. Very little he wrote after his school days reveals a notable sense of humor or an inclination toward self-satire. There’s no record of his telling jokes or responding to other people’s.

But on Christmas Day 1762, he had his moment as a humorist, a self-mocking memoirist, the kind of writer he never was to become. Still, the story creator, the exaggerator, the tall-tale teller, the writer who could use language effectively to define himself to himself and others was there from the start. “This very day, to others the day of greatest mirth and jollity,” he wrote to Page, “sees me overwhelmed with more and greater misfortunes than have befallen a descendant of Adam for these thousand years past I am sure.”

Jefferson’s lamentation about the loss of the image in his watch was spontaneous self-expression. Job’s “misfortunes,” he humorously acknowledged, “were somewhat greater than mine, for although we may be pretty nearly on a level in other respects, yet I thank my God I have the advantage of brother Job in this, that Satan has not as yet put forth his hand to load me with bodily afflictions.” At least he was young and healthy. He was also indulging his pen in playful self-mockery. “You must know, dear Page, that I am now in a house surrounded with enemies, who take counsel together against my soul and when I lay me down to rest they say among themselves Come let us destroy him.”

These enemies were a host of aggressive rats in a parodic and comic misfortune, with a semiserious complication. The rats had, he wrote, animating them into playful agency, conspired against him as agents of the devil. “I am sure if there is such a thing as a devil in this world, he must have been here last night and have had some hand in contriving what happened to me. Do you think the cursed rats (at his instigation I suppose) did not eat up my pocketbook which was in my pocket within a foot of my head? And not contented . . . they carried away my . . . silk garters and half a dozen new minuets,” sheet music he needed for his violin practice and pleasure. “But of this I should not have accused the devil (because you know rats will be rats, and hunger without the addition of his instigations might have urged them to do this) if something worse and from a different quarter had not happened.”

To blame the devil was not a religious construction. Jefferson was never to believe in supernatural creatures except for a first cause. That was his view from early on. “When I went to bed I laid my watch in the usual place, and going to take her up after I arose this morning I found her, in the same place it’s true but! . . . all afloat in water . . . and as silent and still as the rats that had eat my pocket-book.”

As a storyteller he could have it both ways: it could not have been accidental, though the denial was an affirmation that it was accidental. He had been unlucky. He also had been careless. It was good fun to make the Devil take the blame. “There were a thousand other spots where it might have chanced to leak as well as at this one which was perpendicularly over my watch. But I’ll tell you: It’s my opinion that the Devil came and bored the hole over it on purpose. Well as I was saying, my poor watch had lost her speech: I should not have cared much for this, but something worse attended it: the subtle particles of the water with which the case was filled had by their penetration so overcome the cohesion of the particles of the paper of which my dear picture and watch paper were composed that in attempting to take them out to dry them Good God! . . . my cursed fingers gave them such a rent as I fear I never shall get over. This, cried I, was the last stroke Satan had in reserve for me: he knew I cared not for anything else he could do to me.”

It was, he mock angrily concluded, his fingers that were “cursed.” But the clumsy fingers whose touch had completed the shredding of the image firmly held the pen that created this expressively imaginative letter. Among his gifts as a writer, he had at times, for eighteenth-century prose, a colloquial and conversational voice.

In Jefferson’s Virginia, courtship between members of the same class was highly ritualized. He was marginally too young to marry; the lady in the silhouette was of marriageable age. The woman whom 19-year-old Jefferson had fallen in love with was 16-year-old Rebecca Burwell. He had attempted to engage with her in Williamsburg, with no significant success. Shy and almost speechless, his first attachment of the heart was strong but recessive. She was the recipient of and the projection of the dialectic between his desires and his shyness. With Rebecca, his body talked awkwardly and mostly in flight. Expressive and bold on paper, in her presence he tended to be irresolute, tongue-tied. Apparently, sex and courtship both enticed and confused him.

Whatever his physical intensity, he gave it no expression for the record. Rebecca seems not to have taken him seriously enough to advance their relationship beyond Williamsburg dances and social gatherings. Much of the relationship was in Jefferson’s head. It was also in his letters to friends. The image that had been enclosed in his watch had been, he wrote to Page, “defaced.” But “there is so lively an image of her imprinted in my mind that I shall think of her too often I fear for my peace of mind, and too often I am sure to get through Old Cooke [Edward Coke’s Institutes of the Lawes of England] this winter: for God knows I have not seen him since I packed him up in my trunk in Williamsburg.” ~

https://lithub.com/how-thomas-jeffersons-writing-established-the-stories-of-colonial-america/?fbclid=IwAR2g39fAM4Cal_bCNWOf4d7_ijXJPeUfZwvKSgRv_L-Eb6I3hBxdPBdXp78

Young Thomas Jefferson

*

“There's nothing in the world for which a poet will give up writing, not even if he is a Jew and the language of his poems is German.” ~ Paul Celan, 23 November 1920 – 20 April 1970

*

“RUSSIA IS A COUNTRY OF LOW EXPECTATIONS” (Misha Firer)

~ According to a recently conducted poll that’s gone viral on Telegram, 30% of Russian families save on foodstuff. My boss also saves on foodstuff: he stopped buying beluga caviar and French champagne.

Average Russian family spends half of their salary on groceries and not because they eat more.

The other half of the wages is for purchasing Chinese off-brand clothes. Unsurprisingly millions of men choose to work for law enforcement agencies and as security guards — free clothes hence disposable income to spend on hobbies like fishing in an ice hole.

A year ago, a third of the families could not afford new footwear in a country where president has stolen every election in the past quarter century on the promise he’ll improve living conditions.

When I first visited my wife’s aunt’s family in Monino, a site of Air Force base, my aunt was impressed that I wear a cotton shirt. It was a telltale sign that I’m wealthy and great husband material. She also believed that America wants to break Russia apart and enslave them. I told her, “in your dreams.”

My wife’s father, a retired Military Intelligence officer, was amazed that I don’t drink vodka and don’t smoke. I told him “I can also juggle with three balls.” Russia is a country of low expectations.

The remainder of the rubles pay the school administration to fix leaking roof and enterprising teachers who blackmail parents with bad grades, and if there’s anything left -- the utility bill.

Millions of households are heavily indebted on their utility bills, and pay them in installments like for a new iPhone. Americans foreclose on a mortgaged property. Russians foreclose on a utility bill.

Young families earn more than middle-aged folks who have life force equal to that of American retirees in Florida, but they’re stuck with the exorbitant mortgage payments for the apartment the size of a kennel in a humongous apartment complex.

More people live in one solid block of vertical real estate in Russia than on five square miles of subdivisions in Suburbia USA. Go green!

Average Russian family does not have a car. That’s why state-owned federal TV pitched a story of a happy family receiving from the government a Lada sedan for the son killed in Ukraine.

Average Russian family does not take vacations. Over 80% have never been abroad. And that does not include people who pop across the border for shopping in Georgia, Kazakstan, China.

Over half of Russians have never visited a medical doctor or dentist. When I travel outside of Moscow, the first thing I notice that people are missing teeth. Like, half a mouth of missing teeth.

There are effectively two classes of Russians: have-teeth (20%) and have-no-teeth (80%).

Those who have no teeth, Putin dubs drunks and suggest sending them to the trenches because it’s better to die for him than from home-brew alcohol. This message is addressed to wives to cash in on good-for-nothing husbands.

But what do Russians think about the mobilized? Let’s ask Google.

At first glance, Russians want to see their favorite actors and musicians in military uniforms and less glamorous surroundings of the war front. Not so much their husbands and sons. And it looks like they don’t care much about salary for the mobilized husband.

Perhaps Putin is wrong about Russians and they are not a bunch of low-life drunks? It’s hard for the people with teeth to admit that people without teeth are human being too. ~ Quora

Tim Orum:

The problem with serfs that have too many teeth is they use them to eat. The less they eat the more for the noblemen and women and their minions. That’s taught in Serfdom 101.

Geoff Caplan:

According to official Russian figures, 25% of households don’t have indoor toilets. This is much the worst figure in the developed world — and according to the Ukrainians many of the orcs who have been billeted in their stolen apartments don’t appear to understand how to use a flush toilet.

Plus a state pensioner has to subsist on around $US 250 a month.

This is what happens when the plutocrats steal all the wealth and leave the people to fester in poverty.

Oriana:

Many have pointed out that the elderly in Russia have it the worst. Apparently they are forced to spend almost all of their income on food.

Kathy Leonhardt:

The thing that perpetually stuns me is the belief by Russia that we (the West) want to INVADE or take her…. honestly— it’s like the last woman (or man ) in the bar at 3:00 am out cold over a barstool — we ARE NOT interested!!!! Absolutely NOT interested!!!

Mary:

I was moved by the descriptions of poverty in Russia, shocked actually, to think of that vast majority living in such misery, and so inured to it they accept it as the norm. In the US a good measure of poverty is the condition of a person's teeth — dental care is very expensive and often, even for those with insurance, not covered. Good dental care can be seen as an expendable luxury rather than a necessity. The very poor often have bad teeth, or no teeth. It seems in Russia this is also true but the proportions are reversed, it's not a minority but the majority of the population that are too poor to afford dental care, going on with poor teeth or no teeth at all. Nothing about this is comical — dental health is integrally connected to one's general health, particularly to the heart, and to risks of infection.

What can inure people to such miseries as are described? Beyond oral health this large majority often lives without indoor plumbing, reliable electric power, or sufficient and affordable food. So many people living like serfs in the 19th century, without hope of anything better. I think the answer is the efficiency and all pervasiveness of the propaganda machine. Information of the world outside the Russian state is limited and tightly controlled. Of course it is also distorted as well, to suit the narrative that the world outside is filled with evil...capitalists and Nazis who want only to steal, invade, repress and destroy everything they can reach.

When these poor Russians, like Putin's conscripted soldiers, see that the outsiders do not live in the same misery, the reaction can be anger, the wish to destroy, the effort to steal, and bewilderment that the world is not what they were told it was. They may very well try to steal washers and refrigerators, or smash them to pieces. Leaving their excrement everywhere may not be simply inability to operate the indoor plumbing, but an angry response to their own deprivation of something so basic everyone else takes it for granted.

I have to also suspect that in terms of Russia's military Putin himself was duped by his own propaganda. I don't think he actually knew how hollow and ineffective his forces had become under the all pervasive sway of corruption at every level of responsibility. I think he was surprised and humiliated, as well as enraged. He seems to have painted himself into a corner, and I wouldn't be surprised if he actually decided to use those nukes he keeps threatening us with.

The actual condition of those weapons is of course also in question. If all the funds for maintenance have been redirected to corrupt officials, can these weapons even be functional...or are they masks of the Kremlin's paper tiger, useless as the cardboard armor of his soldiers?

Oriana:

The good news is that Putin is unlikely to use nukes — NATO’s response is just not worth it.

The bad news is that even though the condition of most of Russia’s nukes may be pretty useless, they’ve got so many of them that if just 10% detonate, the world will be fried. But again, it is VERY UNLIKELY that Putin will use nukes. Nukes are useful as a deterrent, but not really as a battlefield weapon.

Russia is betting on its artillery. Why go into a city and risk fighting in the streets? Let’s level with city with artillery, and afterwards we can search the rubble for anything that could still be looted.

I imagine Putin was indeed shocked to find out the truth about his troops. Let’s remember that this guy, regarded as quite smart, thought that Kyiv would fall in three days!

*

As for poverty in Russia, I remember how shocked I was when I first heard about the food shortages, back in the times of the Soviet Union. I learned about people drinking “keepyatok” — boiled water — because there was no tea or coffee. One Russian emigré mentioned those embarrassing rumblings in her belly — because she was hungry!

In Poland agriculture was in private hands — mostly small family farms — so there was plenty to eat. Yes, occasional trouble getting quality meat, so you had to settle for whatever was available, and stand in line for it . . . But on any Sunday, the streets smelled wonderful — chicken broth, roasts, cutlets . . .

Another bonus of small-farm agriculture was that everything was organic, even though the concept wasn’t yet really born. I was told that German merchants used to cross into Poland, buy food, and then sell it in Germany at good profit as organic. (That was after the wall had fallen, so we are speaking of capitalist Germany here.)

*

*

Which reminds me of one more thing: though much is known about the Russian troops looting and raping as their standard behavior, it’s only recently that I learned how shocked the Russian soldiers were after they entered Germany and saw how rich Germany was. And that made them angry: so this was a rich country invading their hungry homeland . . .

*

*

SHARED RATIONS AND SLEEPING BAGS

~ More are more details are gradually leaking out concerning conditions that the Russian soldiers are facing.

One student who was recently discharged from Russian forces in Ukraine says he was equipped with a Soviet-era bolt-action rifle, and had to share rations and a sleeping bag when first sent to the front.

“When times were hard, we had a certain number of people and there weren’t enough sleeping bags for everyone, you could only cover yourself with a raincoat. We were able to get two or three people into a sleeping bag to keep warm,” said Vladimir. He was a young man who appeared to be in his late teens.

“At first we didn’t have enough food. After that, everything was fine with supplies, they were completely sufficient, but at first we shared with each other” Vladimir said.

Vladimir said he had, like many others, been given a Mosin sniper rifle — a bolt-action weapon designed in Tsarist Russia in the late 19th century and updated in the 1930s.

This is not the only report. Other reports of young men being sent to fight in Ukraine with inadequate clothing and equipment have stirred deep public concern in Russia. President Putin has given orders for better coordination between government, regions and industry to meet the needs of the military. Whether those orders have been met is still uncertain.

Putin ordered a “partial mobilization” in Russia in September. But in reality, Moscow’s proxies in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine began calling up men of fighting age much earlier.

Vladimir was drafted into the forces of the breakaway Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) on Feb. 23, the day before Russia sent its forces into Ukraine.

On Monday, November 28, he was among dozens of young men who were demobilized at a ceremony in the town of Starobesheve.

Hopefully Vladimir will return to his own home and be able to have a bed to himself. Vladimir is fortunate to be alive after experiencing this. ~ Brent Cooper, Quora

*

THE BATTLE OF BAKHMUT COMPARED TO WW1 BATTLE OF THE SOMME

~ As Russia's brutal, pointless, little-heeded war against Ukraine lurched on, grim images emerged on social media of Ukrainian soldiers caught in the bloody quagmire around Bakhmut, an eastern city that after months of fighting has devolved into a ravaged landscape of splintered, shell-torn trees, yawning artillery craters, strewn dead bodies, and sodden Ukrainian forces hunched in a muddy, freezing, deadlocked trench warfare against relentless enemy barrages that in its desolation and destruction some have likened to "the new Passchendaele." That infamous 1917 clash, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, saw the Allies suffer roughly 300,000 casualties and inflict almost that many on the Germans in one of the most costly battles of World War One; it is remembered not only for its horrific loss of life but its freezing, sucking mud, "a monster," that drew soldiers to their deaths.

In "a bloody vortex for two militaries," Russian leaders desperate for a victory have been focused on moving reinforcements to the killing fields of Bakhmut. After so many reverses for their elite units, fighting has reportedly fallen to a mix of separatist militias, mercenaries and newly mobilized, ill-trained conscripts backed by massive artillery barrages, often aided by drones to make them particularly, lethally accurate. Amidst reports of Russian assaults on a "World War One hellscape," observers cite Russia's stunning disregard for their own troops, with commanders sending "single use" soldiers out in waves "like meat" to find Ukrainian positions; with Russian losses estimated at up to 300 a day, Ukraine "has become one giant graveyard" for them. Others say Ukraine's wet, cold winter is "the biggest killer" for "under-trained, under-supplied, ambivalently led" recruits lacking proper food, gear, boots or shelter, with dozens freezing to death.

For many, Putin's bloody debacle in Ukraine reflects a system "in which medievalism meets Stalinism meets dark farce," the "barbarism to which Russia’s 'new normal' has sunk... part horror movie and part theater of the absurd" in which leaders rant about a "holy war" against Satan and even the few surviving protests have a touch of the surreal. But the remaining, mostly elderly residents of Bakhmut, who make up perhaps 10% of its pre-war population of 80,000, have more concrete concerns: Sheltering in wet basements, they face a winter without adequate power, water, heat, food. Intrepid volunteers have mobilized to deliver wood stoves, chop firewood, gather warm clothes and other necessities; harrowing videos show them evacuating, often under heavy shelling, the ill and infirm. Those who stay are pissed. "Why is Putin so stupid?" asks one woman. "Doesn't he have enough land?”

Over a century ago, H.G. Wells described the First World War as "the war that will end war," though over time the term has morphed into, "the war to end all wars." It was used first hopefully, then desperately, for a conflagration that began for no truly coherent reason in September 1914, lasted over four years, and ended with roughly 40 million casualties, about evenly divided between dead and wounded.

Wells believed the conflict would create a new world order in which future conflicts would be impossible, and a world government would protect individual human rights regardless of sex, creed or color. By crushing the Kaiser's German empire, and the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, the Allies would serve as not just soldiers in war but "crusaders against war." “There shall be no more Kaisers," he wrote. "We are resolved. That foolery shall end! It is the last war.” Oh, what a falling off was there.

"War will only end when people so realize its horrors (that) they prefer to refrain from fighting even when they believe that they have a just cause.” ~ Bertrand Russell on the "more calm and equable courage" peace requires.

https://voxpopulisphere.com/2022/12/01/abby-zimet-ukraines-battle-of-the-somme/

*

MISHA IOSSEL ON THE NEW RUSSIAN EMIGRÉS

~ The Russian-language segment of the FB now is such a Fellini-like choir of previous newly-left and the more recent newly-left. There is something in it from the emigrant cycle of the post-Bolshevik times of the last century: Constantinople-Paris-Berlin-Prague; only now also — Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan.

Photos, sharing impressions and observations, life hacks, jokes about the old and the new, artistic texts, congratulations, family memories, projects, plans for the future…

The future is hidden in darkness. Gradually, the understanding comes that there is no return to the previous life. ~

Oriana:

“You can’t go home again” holds here. Once you step out of the circle of family and friends, you become an outsider. Without knowing it, you have burned the bridges behind you. If you stayed abroad long enough, you’ve become a different person, and so have those you left behind. There is an irreparable gap in shared experience. Nor are your old friends eager to have you tell about those other lands and cities. They are basically interested in their own current lives, not your life. You’ve become a stranger in a strange land — in your own native country, after having been a stranger elsewhere.

Oddly enough, as I sat waiting for my next plane connection at the huge airport in Frankfurt-am-Main, I instantly understood that I was now a different person and could never go back to who I used to be. Not that I could define that difference, or engage in speeches about freedom and Western individualism and/or capitalism. To this day I can't quite explain why I had that sense of having been instantly changed. Was it hearing German spoken around me, and rather liking it? Was it the immense brightness of the fluorescent lights forming their own sky? Or was it rather being on my own, suddenly an adult? I'm content to let the mystery remain: I was changed. And there was no return to my previous life.

*

Getting older -- I mean seriously older -- also bears some similarity to being an immigrant. You are judged to belong to "another era," before iPhones. And you don't have a future. Those who wait to inherit hope you'll soon be gone. That makes being an immigrant seem relatively easy, even if you spent the first year or two crying yourself to sleep.

*

MORE FROM MISHA: MUSINGS ON TIME

~ Time is not our friend, of course. It has no sympathy for us. We don't swim in it the way fish swim in water. We pass through it as its uninvited guests. It ages us, and in the end it kills us. But it is in a race against it that some of us, one in a million or billion in every successive generation, produce the miraculous masterpieces of art and spirituality that time can bring as gifts to its master, and our true homeland -- eternity. The Great Pyramid of Giza or the Cathedral of Chartres, Mona Lisa or the Sistine Chapel, or a Shakespeare play or Tolstoy novel or Dante's epic -- all of these have been created within the bonds and bounds of time. Eternity, to quote one of time's greatest visionaries and diviners, is in love with the productions of time. ~

Oriana:

It was William Blake who said, “Eternity is in love with the productions of time.” Very few paid attention to Blake while he was alive. And yet he stepped into eternity — or, to be more accurate, literary and artistic immortality.

*

GEORGE BALANCHINE VISITS THE SOVIET UNION, 1962

~ On October 6, 1962, the members of New York City Ballet boarded a plane in Vienna, bound for Moscow, the first stop on an eight-week tour that had been arranged by the State Department. The party numbered around ninety, including the dancers, the conductor Robert Irving, two mothers (escorting underage dancers), several translators, the company doctor, and the company’s co-founder and artistic director, George Balanchine.

Balanchine had not wanted to go. Born in St. Petersburg in 1904, during the reign of the last tsar, he had experienced cold and starvation in revolutionary Russia, before fleeing the country, in 1924, going first to Europe and then, in 1933, to America. The U.S.S.R. filled him with dread, and his return brought to light one of the great themes of his life: he had set his own path away from the Marxist materialism of the Bolshevik Revolution, and quietly built, in N.Y.C.B., a village of angels and a music-filled monument to faith and unreason, to body and beauty and spirit. It was his own counter-revolutionary place, an alternative vision of the twentieth century.

The dancers had stocked up on peanut butter, candy, tuna, Spam, toilet paper, and other necessities. Balanchine had also asked that they please dress well, since he wanted his company to present an elegant image. When they landed at Sheremetyevo, Balanchine emerged from the Jetway in a suit and bow tie, a trenchcoat draped casually over his arm. A full-court reception awaited him, with klieg lights, flashing cameras, Soviet officials, American diplomats, and a press corps eager to record his return. The sparring began immediately: “Welcome to Russia, home of classical ballet,” one of his hosts began, and Balanchine proudly responded, “No, Russia is home of Romantic ballet, America is the home of classical ballet,” by which he meant his modern ballet.

It was Cold War code: culturally, the war was being fought in part on the battlefield of abstraction, and Balanchine was taking a defining role. Stalin’s doctrine of socialist realism had long defined art in the U.S.S.R., and in dance this meant lavish narrative “drambalets,” often with socialist themes. Balanchine had pushed classical technique and the human body to new physical extremes, especially in his recent plotless dances, “Agon” (1957) and “Episodes” (1959), performed in simple practice clothes on an empty stage. In the U.S.S.R., such abstraction was still deemed a political threat, a slippery artistic form dangerously free of any fixed meaning that could be approved or censored. (Who could say exactly what “Agon” was about?) Balanchine flashed his American passport in case anyone didn’t get the message. But his attention was not fully there. He had seen his brother Andrei, who was standing patiently to one side, waiting.

“Andruska! It’s you,” he said, as they embraced, and his expression softened with emotion. They had not seen each other for some forty years, since the Revolution had torn their family apart. He was surprised that Andrei was so short, and it was true that Balanchine, who thought of himself as small, seemed to tower over him. At fifty-seven, Andrei was already gray, and next to his dapper sibling he appeared aged and shy, in a rumpled suit with drooping, oversized pockets (stuffed with tobacco, cigarette papers, and homemade filters composed of cotton and sugar). Although he was younger than George, he looked like an old man.

Andrei, who lived in Tbilisi, had followed the path of their father, Meliton Balanchivadze, a Georgian composer who had spent his career collecting traditional Georgian music and forging a style influenced by it. By now, Andrei was a well-known composer in Georgia, but his life had nonetheless been constrained by the harsh realities of Soviet existence—and by his brother’s American success. In the eyes of the state, Balanchine was a traitor, and a curtain of fear had fallen between him and his family. Fear, in his mind, of recrimination; in theirs, of association and disappearing into a Soviet night. Since leaving, Balanchine had received only one letter from his brother, and it had been delivered to him by a man he suspected of being an agent of the secret police. In it, Andrei had implored George to return to the U.S.S.R., but George sensed, correctly, that his brother had written the letter under duress and ignored it. Andrei had also sent a terse cable notifying him of their mother’s death. That had been the extent of their communication. It was a peculiar fact of exile and the Cold War that, in order to care for each other, they couldn’t know each other. The only protection they had was silence—its own kind of family tie.

The brothers went to dinner together at a nearby restaurant that served Georgian food. Balanchine eagerly selected favorite dishes from the menu, only to be told each time that the item was not available, so they finally settled on coriander chicken—all that was on offer that evening. The Hotel Ukraina, where Balanchine was staying with the company, had a similar empty grandeur. It was monumental, a fortresslike complex in yellow stone with eight turrets and a central tower with a high spire topped by a Soviet star. One of the “Seven Sisters” commissioned by Stalin to compete with American skyscrapers (and modeled in part on the Manhattan Municipal Building), the Hotel Ukraina was devoid of human scale, built in a style that Lincoln Kirstein, the company’s co-founder, called “Stalinoid Gothic.” Completed in 1957, it already felt old and run-down.

The enormous gray marble lobby resembled a train station, with a large restaurant emitting a pervasive Soviet smell of onions and cabbage. The thirty-seven floors and more than a thousand rooms were served by only a few very slow elevators, manned by stolid ladies in suits, and the wait could be more than half an hour to travel a few floors. The thirteenth floor was said to house the bugging apparatus for the whole building, and on each floor a uniformed matron sat at all times (with a cot for sleeping), controlling keys and entry. Once a guest passed muster, the walk to a room could seem miles long, down dreary carpeted corridors, and the rooms themselves were decorated in a worn Biedermeier style with Oriental throws. Everyone had been told that the ceilings were lined with bugging devices, and the dancers made a sport of discovering them.

They ate at the restaurant in the lobby: pirozhki, dark bread, cucumbers, pickles, borscht, chicken Kiev (“gray leather,” one of the dancers said), bottled sweet sodas, Russian ice cream. Balanchine asked for Borjomi, a sulfurous mineral water he remembered from childhood; to the dancers, it reeked of rotten eggs, but he guzzled it down. A pall of surveillance hung over everything. Their movements outside the hotel were tightly controlled, and buses carried them to rehearsals every morning, as well-wishers shouted, “No politic, no politic!”

A few of the dancers ignored the restrictions and walked through the wide streets and crowded markets anyway. The requisite “interpreters” (undercover secret police) were their constant companions and occasional adversaries in chess matches, played with ice hockey blaring on TV in the background. Contact with family back home was difficult. Mail arrived erratically via diplomatic pouch, usually already opened, and making an international phone call could take hours. If the caller was lucky enough to get a connection, it was often only one-way—the person in Moscow could hear but not be heard, as operators seemed to be controlling the flow of information leaving the U.S.S.R.

The response to the performance, by this audience of officials, was polite but restrained, and Balanchine found himself devastated, confused, and angry that he was angry or that he cared at all. Once the official contingent finally cleared out, however, a group of students from the upper balconies rushed enthusiastically to the front and applauded the dancers. A fancy reception followed, hosted by the American Ambassador, Foy D. Kohler, at his elegant residence, Spaso House, formerly a merchant’s palace. The gracious, imperial-style rooms were crowded with dancers and the Soviet artistic and political élite—including, it was noted, Khrushchev’s son-in-law, whom Balanchine studiously avoided in order to minimize any political complications.

The next day, the production moved to the gigantic, six-thousand-seat Palace of Congresses, which had been sold out for days. It was an impressive, if cold, new theater, a huge stone-and-glass structure originally built to host the Twenty-second Congress of the Communist Party, in 1961. The dancers were amazed to find air-conditioning, a fully stocked restaurant, and marble bathrooms with plenty of toilet paper.

Seeing the cavernous stage, Balanchine immediately pulled the planned dancers for “Serenade,” who could barely be seen in the vast auditorium, and replaced them with taller ones. This time, and for most of the rest of the run, the Soviet people stood and cheered for the company, urging on their favorite artists by chanting their names (“Meetch-ell! Meetch-ell!” for Arthur Mitchell) and, at the end, calling for Balanchine to take a bow—“Ba-lan-chine! Ba-lan-chine! Spa-si-bo! Spa-si-bo!”—until he appeared from the wings and bowed modestly. As the Russian crew began to extinguish the lights, he gently implored the audience to go home; the dancers needed to rest.

He had to admit his immense satisfaction that audiences especially loved “Episodes” and “Agon,” his new abstract dances to largely atonal Webern and Stravinsky scores. The dancer Allegra Kent was even dubbed “the American Ulanova,” a reference to the beloved Soviet dancer Galina Ulanova. Critics were more ideologically constrained and complained that these dances were cold and lacked the warmth of theatrical dress and a human story. Balanchine patiently endured interview after interview, tirelessly explaining his approach to beauty and the human figure. His un-Sovietized Russian flowed, and, at times, even the facial tic that had been with him since childhood—a kind of nervous sniffing and nose twitching—melted away as he meticulously answered in his native tongue those who called his work mechanical, grotesque, or “repulsive.” But when a prominent critic told him that his ballets had no soul he sharply retorted that since Soviets didn’t believe in God they couldn’t know about the soul. And, when a delegation from the Ministry of Culture asked him, please, to cancel “Episodes” because “the people” couldn’t understand it, he responded, in a rare show of temper, with a Russian equivalent of “Fuck you” and walked out.

It all wore on him—the daily petty humiliation of waiting in the freezing cold while some guard, who by then knew exactly who Balanchine was, double- and triple-checked his papers before allowing him into the Kremlin or the theater. One day, he forgot his official pass, and the guard turned him away, leaving a gaggle of frustrated journalists shouting from the other side of the barrier, a scene that delighted him by exposing the comedy of Soviet officialdom.

Everything seemed grim and gray, he said—the food, the dress, the way people warily checked their every movement, even while walking down the street. His stomach clenched when an old friend invited him to his home, two cramped and dingy rooms, and proudly showed him that he had his own bathroom. Balanchine complained that the phone in his hotel room rang mysteriously in the middle of the night and that the radio would suddenly turn on. He was haunted by nightmares about losing his passport or being thrown into prison or suffocating. “A little green devil is following me,” he said, and he was not joking. He was losing weight fast and looked noticeably gaunt, and bursitis was making his shoulder inflamed and painful.

His temper flared. One night, after a bravura technical performance by Edward Villella in “Donizetti Variations,” the cheering audience called Villella back for bow after bow, until he finally performed an impromptu encore. Balanchine was beside himself with rage and stood in the wings fuming. Such a deviation from the score was everything he had fought against, and he was as angry as the company had ever seen him. As he later put it, “This is not circus.”

The dancers were on edge, too: one got so drunk at a reception that he started smashing glasses and bad-mouthing “America of purple mountains majesties,” until he was escorted out and put on a plane back to the United States. Allegra Kent recalled “horsing around in crazy ways,” and other dancers remembered her performing an “improvised beatnik twist” for a gathering crowd of astonished Russians. There were whispers of dancers having affairs with their K.G.B. handlers and falling in love with Soviet musicians. The dancer Shaun O’Brien was arrested for taking pictures of pigeon tracks in the snow and held in custody for hours, where he was questioned at length about Little Rock, Marilyn Monroe—and Cuba.

Cuba. On October 22nd, in the middle of the company’s Moscow run, President Kennedy went on national TV to inform the American people that the U.S.S.R. had installed offensive nuclear missiles in Fidel Castro’s Cuba that were capable of reaching American cities. He coolly announced a strict quarantine of the island and the readiness of the United States to retaliate on Soviet soil in the event of a nuclear strike. When the news of this terrifying standoff reached the Embassy in Moscow, Kirstein, Balanchine, and a couple of others were informed of the situation.

Kirstein and Betty Cage, who helped run the company, quickly came up with a disaster strategy. Plan A was to charter a plane; if the word came from the Embassy, the dancers could board waiting buses to the airport and take off immediately. If they couldn’t get to the airport, they’d resort to Plan B: get everyone inside the Embassy. Plan C was to then arrange a “prisoner swap” with the Bolshoi dancers, who were on a cultural-exchange tour in New York. When Kirstein shared these wildly unrealistic scenarios with the Ambassador’s staff, the response was swift: “The first thing we will know at the Embassy is that the phone will be cut off.”

For the moment, he was told, there were no plans for evacuation, and the Ambassador would attend rehearsals to allay any panic. As a comfort, the Embassy kitchen was made available to the dancers, who occupied themselves eating hamburgers and steaks, and in a touching sign of solidarity the staff at the Ukraina placed vats of flowers on the tables for the company. While N.Y.C.B. continued to perform at the Palace of Congresses, Khrushchev and other officials went to see an American singer at the Bolshoi Theater—a way of signalling calm while still snubbing Balanchine. (Kirstein nervously scuttled back and forth.)

On October 27th, “Black Saturday,” an American U-2 reconnaissance aircraft was shot down over Cuba and the pilot killed. Information was not widely available, and secret negotiations were under way, but the surprise downing of the plane (by a local commander) further frayed nerves in Washington, Moscow, and Havana. By then, the United States was already at DEFCON 2, one level below war; U.S. long-range missiles and bombers were on alert; and planes carrying atomic bombs were taking off around the clock, prepared to move on targets in the U.S.S.R. In Cuba, surface-to-surface missiles and nuclear warheads were ready in the event of war, accidental or otherwise.

In Moscow that afternoon, in a separate incident, Soviet troops moved into place around the American Embassy to protect protesters who were throwing ink and eggs in a large demonstration against the imperial capitalist United States. (The protest was staged, it later transpired, by Soviet authorities, who bused in confused students and workers for the event and supplied them with posters and things to throw.) The American Embassy told the dancers to stay away and informed Kirstein that, if war broke out, it would be powerless to help them, and they would all have to use their wits to survive. Officials warned that the audience that night might rush the stage and advised the company to be prepared to immediately bring down the heavy safety curtain in the event of a riot.

That evening, the dancers, aware of some vague but imminent danger, nervously gathered at the theater. Balanchine was strangely calm and commented dryly that he hadn’t yet seen Siberia. He never believed there would be a war, he later explained, because neither Khrushchev nor Kennedy wanted one, but there was more to his detachment than that. Russia had held a gun to his head once before, with the Revolution, and this time he had been training himself for years to expect death and to live only in the present moment. That “now” for him was one of the greatest skills in ballet. (He liked to say to his dancers, “What are you saving it for? You might be dead tomorrow!”)

As the curtain rose on Bizet’s “Symphony in C,” the dancers stood for a moment in disciplined anticipation, staring into the blackened house of the theater. Irving was poised at the podium, baton raised for the downbeat, and at that moment the audience suddenly grew larger than itself and rose in spontaneous applause. With the first note, an adrenaline rush brought on by pent-up fear and relief flowed through the dancers’ bodies, and they danced with the energy of life-giving release. At the end of the piece, Bizet and Balanchine’s exuberant and decisive close elicited rhythmic chanting from the audience, until finally Balanchine, looking small and thin, stood center stage and spoke quietly into the hushed auditorium. He thanked them all and then asked them to please go home; the dancers were tired and would be back tomorrow.

When tomorrow came, Armageddon had been averted. Kennedy and Khrushchev had reached an agreement, and late that afternoon the news was broadcast in Russia and around the world. As it happened, that night was N.Y.C.B.’s last performance in Moscow, and after the cheering and chanting at the end of the show Balanchine took the stage again. This time, he graciously invited the audience to follow the company to its next destination, which would be Petrograd, he said, deliberately using a name for St. Petersburg that predated the Revolution. Despising Lenin, Balanchine refused to use the name Leningrad for his beloved native city.

*

The moment they arrived and checked into the Hotel Astoria, Balanchine grabbed a couple of company friends, saying, “Let’s go to my old house”—by which he meant his aunt’s old rooms on Bolshaya Moskovskaya, across from the old Vladimir Cathedral, which he had often visited while a student at the Imperial Theater School. The apartment building was still there, and he could see his aunt’s window, but his heart sank when he saw that the once beautiful house of worship across the street was now a factory. Worse, the mighty Kazan Cathedral, which they had passed on the way, had been converted into an anti-God museum. Still, he raced to the Imperial Theater School, on Rossi Street—but to his companions’ surprise he stopped short at the entrance. His mind locked, and he couldn’t go inside. How would he manage the memories that were so tightly packed inside this old building? He found a small church that was still open and lit a candle there instead.

The people he had known were still alive; he just didn’t recognize them—didn’t want to recognize them, perhaps. His once beautiful young teacher Elizaveta Gerdt, for example, was now an old woman, he sadly noted. He had wanted to see the choreographer Kasyan Goleizovsky, an idol of his youth, but when he saw Goleizovsky’s “Scriabiniana” performed by the Bolshoi he was so embarrassed that he cancelled the visit. He didn’t want to meet a feeble and wrinkled old man and preferred his memories of this crucial iconoclast. In Leningrad, he met a few members of his first dance company, Young Ballet, but now they just seemed to him “old and brown and bent like mushrooms. How can you feel affectionate and sentimental about a mushroom?” He did want to see Fyodor Lopukhov, whose “Dance Symphony” had been such a formative influence, but the old choreographer declined a visit. Balanchine’s obsession with aging was irrational, of course, and he was older, too, but he couldn’t stand that his colleagues, who had been so lovely and vibrant, had grown old and “dumpy,” as if the ruin of their bodies was part of the ruin of Russia itself.

The more he was fêted, applauded, and celebrated, the more depressed, self-controlled, and in charge he became. When he learned that students and artists couldn’t get tickets for the company’s performances, he arranged a free performance of his most radical works at the Palace of Culture: “Apollo,” “Agon,” and “Episodes.” He met with Soviet choreographers to discuss the principles of his art, and when the youngest among them asked for more he met them again informally at the theater. When Konstantin Sergeyev, the artistic director of the Kirov Ballet (and an apparatchik), obsequiously presented him with a silver samovar and flowers onstage, noting that Leningrad was Balanchine’s home town, Balanchine pointedly accepted on behalf of New York and America. It all reminded Kirstein of the coronation scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s “Ivan the Terrible.” “Do you remember that scene?” he said to a journalist. “Ivan is on his throne. The nobles bow down before him; they heap gold upon him. And he sits there, implacable—he is absolutely implacable.”

Balanchine was also tense, moody, competitive, and despondent. When he taught class at the theater, he seemed distracted, and the dancers watched quietly as he peered out the window in a daze, vacantly recalling how he had watched the tsar’s uniformed parades out of these very windows as a child. Ironically, the company happened to be there for the anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, which brought out the Soviet fleet, flags, tanks, banners, huge photographs of Lenin, parades, loud slogans, and carousing crowds. What Balanchine remembered of the Revolution were piles of bodies in the street, and people eating dead horses and rats.

At the theater, the celebrations were marked by the cancellation of “Episodes” because the musicians were too drunk. It was hard for Balanchine not to see everything through the lens of 1917, or else through the rose-tinted glass of the tsar’s empire, and he angrily complained that the theater was full of dowdy working-class people who ate and drank noisily during the performance and didn’t care a whit for what they were seeing—something that was manifestly untrue.

One night, he stood immobilized in the wings as the crowds chanted, and when one of the dancers urged him to go onstage he refused to move, saying, “What if I were dead?” Betty Cage thought that Balanchine was on the verge of collapse and had already arranged for him to skip Kyiv, the company’s next stop, and return to New York for a week before rejoining the company for its final performances, in Tbilisi and Baku. He needed a break. For him, Kirstein said, being in Russia was “a kind of crucifixion.”

*

Balanchine flew to Helsinki on November 8th, spent the night, and left the next morning for New York. Eugenie Ouroussow, a White Russian princess who ran Balanchine’s school, met him at Idlewild, and reported in a letter to her son the two “main points” he had made on the car ride home: that the company had produced an artistic revolution in Russia, and that Russia had “crushed” Balanchine. That week, he and his wife, Tanaquil Le Clercq, entertained guests constantly, as if cooking and hospitality could repair his battered mind. Barely a week later, he departed again for the U.S.S.R., bags stuffed with extra pointe shoes for the dancers.

He rejoined the company in Kyiv just in time to board the plane for Tbilisi, where, again, Andrei was waiting, this time with family in tow. It was a looking-glass moment, the life he might have had. Suddenly, he was little Georgi, and he met the relatives he did not know: Andrei’s glamorous wife, their darkly handsome sons (one named after Balanchine), and their daughter, a dancer. There was also Apollon Balanchivadze, George’s half-brother from his father’s first marriage, whom he had known briefly as a child.

Talking freely was difficult. They were shadowed, and at Andrei’s apartment George nervously pointed to the ceiling, indicating that everything was bugged and they couldn’t speak. Still, in snatches and pieces, he learned the story of his family’s sad fate.

Worst of all: his sister, Tamara. His voice later turned ashen when he spoke of her, in the only recording we have of his account of her tragic end. George had last seen her as a child, and, in the years after he left Russia, Tamara had grown tall and angular, with intense, skeptical eyes and none of her mother’s fragile beauty. She had become a set designer and, after marrying a German who deserted her to return to Germany, ended up working in theater in Moscow and Leningrad. The last the family heard from her was in 1941, just days before the German siege of Leningrad began. She may have been killed during the siege, or she may have died of illness or starvation or perhaps on a train in the war zone trying to get back to Georgia. No one quite knows. She simply disappeared.

Andrei was a survivor. Like his father, Meliton, he was outgoing and prone to excessive toasts and speeches, and he had a wonderful singing voice. He won Soviet medals and honors for his Georgian-style music, and occasionally enjoyed arraying them on his jacket like a general’s insignia. At the right moment, he would strip them off, grinning, make some loud anti-Soviet declaration, and then restore them all again. He played at the margins, calculating in part that the cost to the authorities of arresting the brother of the famous George Balanchine would be too high. But in fact he also did everything he was supposed to do: led the composers’ union, taught at the academy in Tbilisi, composed music in the correct style, and won the requisite awards. So they let him play the jester—within limits. His career was celebrated, but he was rarely permitted to travel to the West. He must not defect, and he never tried.

Apollon was older and less fortunate. Arrested and indicted in 1924 for fighting in a special gendarmes unit of the White Army, he had spent years in prison, in isolation, and although he was eventually released, he was arrested again in 1942 and this time sent for ten years of hard labor in Kazakhstan. Upon his release, he became a quietly practicing priest, and kindly organized a vespers service at a local church specially for George.

George knew that his mother, Maria, had died three years earlier, but he knew little of her sad life. He had last seen her when he was eighteen, in 1922, when she left Petrograd to join Meliton in Tbilisi. Meliton was away much of the time, and she ended up living modestly on a small street in an old church converted by the Bolsheviks into apartments. The frescoes were still on the walls, and some of the nuns who had once made fresh Communion bread in the front rooms resided there, too. Often alone, she wore a brooch with pictures of Tamara, George, and Andrei, and would sit anxiously by the radio listening for word of her Georgi—would they ever let him come home? She watched the mail closely and couldn’t understand why he wrote to say how much he hoped to receive letters from her but didn’t send a return address. In a letter to Andrei, she worried that they had lost the “thread of connection to Georgi. Where is he?!” She faded away as quietly as she had lived, and Andrei arranged a small plot in a large and prestigious cemetery in Tbilisi, as befitting his stature as a famous Georgian composer.

*

Balanchine wanted to visit his father’s grave. Not his mother’s—she had always been a kind of spirit figure in his mind, and he didn’t need her bones. He had her snowy ethereality instead. It was his father whose photo had sat propped on his bedside table for years, and yet Meliton had often been absent as a father, and he had doted not on George but on Andrei, as his musical son and successor. The image of his father, next to his icons, perhaps wasn’t really there for comfort; rather, it was there so that George could show him. See me. Watch me. I am a musician, too.

And now George wanted to see his father’s grave. Not because he loved him—seeing is not the same as loving—but because his father was music, which was what he had become, whereas his mother was the soft inner sanctum that was destroyed, or left behind, that he could get to only through women and dance. Besides, his father was his roots, his soil, and he wanted to see and smell the Georgian heritage he had claimed for so long as his own. Meliton was buried in Kutaisi, near the Balanchivadze family enclave of Banoja, some few hours west of Tbilisi, and George went there with Andrei, Apollon, and his colleague Natasha Molostwoff, accompanied by the inevitable K.G.B. posse. They departed by train at 7 A.M., and Molostwoff later recalled that their car was full of “wild Georgians,” who flocked around Balanchine, taking pictures, talking, touching, celebrating their lucky encounter with this famous artist. When they finally arrived in Kutaisi, exhausted, Balanchine insisted that he and his brothers go alone to Meliton’s grave, at the Green Flower Monastery (Mtsvane Kvavila). Their escorts waited at the tall iron gates to the cemetery.

The story of Meliton’s death, it turned out, was not simple. Andrei told George that Meliton had died, in November, 1937, of a gangrenous leg he’d refused to have amputated, and recalled finding their father lying in bed at home saying that death was a beautiful girl who was coming to take him in her arms, and that he was looking forward to it. But it was later whispered among grave keepers that Meliton had been taken away in the night and shot before being ceremoniously buried—not here, but in the “Pantheon” of famous Georgians under a large pine tree at the foot of the Bagrati Cathedral, a magnificent church turned into a museum by the Bolsheviks.

It wasn’t true that he was shot: Meliton most likely died of gangrene, as Andrei had said, but the rumors were a sign of the violence engulfing Georgian life at the time, and they cast an additional pall over Meliton’s passing. It was the height of the Great Terror, led in Georgia by Lavrentiy Beria, one of Stalin’s cruelest henchmen and, like Stalin, a Georgian. In the year before Meliton’s death, Beria had begun purging the local Party and intelligentsia, a process which accelerated in the next two years. Thousands were killed or sent to the Gulag, including family and friends of Meliton and Andrei. In 1936, at a dinner before a performance of Andrei’s ballet “Heart of the Mountains,” Beria allegedly poisoned the Party stalwart Nestor Lakoba (who had fallen from Stalin’s favor) and then escorted him to the elegant Moorish-style opera house, where the Tbilisi élite witnessed the spectacle of his agonized convulsions as the ballet continued; he died the following morning.

Friends of Meliton whom Georgi and Andrei had met in their home as children had been victims, too. Mamia Orakhelashvili, who had become highly placed in the Party, was arrested on June 26, 1937, and tortured and shot in front of his wife, Maria. By one account, she was forced to watch as her husband’s eyes were gouged out and his eardrums perforated before his execution. She and her daughter were then arrested and sent to the Gulag, and her daughter’s husband, the famous conductor Evgeni Mikeladze, was blindfolded, tortured, and eventually executed. There were show trials broadcast by radio, and Beria’s agents had quotas and routinely slaughtered hundreds of “enemies” in a single night. No one was safe. Closer to home, Meliton’s nephew Irakli Balanchivadze was arrested later that year for “Trotskyism” and shot.

But not Meliton, who was probably too old and too studiously apolitical to matter. Official reports did not mention his gangrene and merely noted that his dead body lay in state in the main hall of the music school he had founded in Kutaisi, and that a small service was performed by a local folk choir before he was interred under the pine tree at Bagrati. Then, in 1957, in a macabre finale, Meliton’s bones were dug up and reinterred in a new, official Pantheon at the Green Flower Monastery, where he now lay near a small church used by the Bolsheviks, it was said, to store cement. His grave, unlike the others around it, was left unmarked except for a large rock and a miniature carving of piano keys. The K.G.B. didn’t give George or Andrei much time with their father, but before they left the brothers poured some wine and spilled the first glass over the grave in the Georgian way.

They also visited the medieval Gelati Monastery, high on a mountain above Kutaisi. Founded in 1106, it had been closed by the Communists in 1923 but preserved as a historical monument, because kings were buried there. Among them was the king who ordered the monastery’s construction, David IV, revered by Georgians as “the builder,” the architect of their country’s medieval Golden Age. David envisioned Gelati as a “second Jerusalem,” and it became a center of Christian culture and especially of Neoplatonism. Its misty grounds, practically in the clouds on a wooded hillside, include the Church of St. George, the Church of St. Nicholas, and the astonishing Church of the Nativity of the Virgin. This was what Balanchine came from and believed in—these were his saints—and although formal worship was not permitted and the monks had long since dispersed, he and his entourage were allowed inside the Church of the Nativity. There they found themselves under a massive arch that seemed to reach as high as Heaven, with light flooding in through the small windows onto the faded but still colorful ancient frescoes. An intricate mosaic of the Virgin and Child with the archangels Michael and Gabriel appeared high in the apse, and a photo shows George in his trenchcoat standing stoically before them.

By the time they left Kutaisi, on the night train back to Tbilisi, it was pouring rain, but Balanchine had seen what he had come for: his father’s Georgia was now his own. It felt to him primal, a Biblical land, and he even enthused to some of the dancers that after Noah’s flood there had been a flight to the Caucasus. Ancient Greece, he said, was settled by Georgian tribes, and these were his tribes, his people. Being Georgian was another way, too, of setting himself against Russia. No wonder some of the dancers were sure that he had been born there. He had told them so. At moments, he may even have believed it.

None of this seemed to deepen his relations with Andrei, who enthusiastically proposed that they make a ballet together, as they had put on shows as children. After dinner one evening at his home, Andrei hopefully played recordings of his music for George and even sat at the piano and regaled his brother with his prize-winning compositions. Balanchine sat bent, with his head buried in his hands, and said nothing. Finally, in frustration and despair, Andrei stopped and waited in painful silence, before awkwardly changing the subject. Natasha Molostwoff, who was there, was appalled: couldn’t Balanchine just say something nice, anything at all? He couldn’t.

The N.Y.C.B. performances were sold out, and on opening night the streets around the opera house were thick with crowds. A sea of people parted for Balanchine as he made his way into the theatre, as if he were some kind of Christ figure—or movie star. The police had been summoned, in anticipation of a crush of people pushing their way in, but the crowds were orderly and civil as, night after night, they pressed into the packed house. On the last night, after the final curtain fell, Balanchine stepped onto the apron of the stage to thank them all. Before the dancers boarded the train to Baku, they piled their extra tights, leotards, leg warmers, and pointe shoes into a bin and left them for the local dancers, who had none.

“Baku or bust”: for the company, Baku was a countdown. They marched through four days of performances, and on the final night a group of them stayed up until dawn dancing and playing strip poker with no heat and the hot-water faucets running full blast until the walls sweated. On December 2nd, the company packed into buses to the airport, then departed on a rickety plane for Moscow. It was snowing hard as they changed for a flight to Copenhagen, destination New York, and by this time the dancers were all chanting in unison: “Go, go, go, go!” As the jet lifted off the icy tarmac at Sheremetyevo, the exhausted company broke into cheers, relieved to, as one of the dancers later put it, “get the hell out of the U.S.S.R.” No one was more relieved than the gaunt Balanchine. “That’s not Russia,” he said. “That’s a completely different country, which happens to speak Russian.”

Soon after landing at Idlewild, Balanchine made a trip to Washington, D.C., for a debriefing at the State Department. By all accounts, the tour had been a personal and political victory, but Balanchine was unmoved. To him, the company’s success meant nothing. Instead, this was the moment when a mirror broke in his mind. He could no longer hold a nostalgic reflection of himself and an imagined tsarist past. That image, which had sustained him even as he also stood against it, no longer existed, and for all his proclamations of Americanness he was left feeling even more homeless and unmoored than he had felt before he set out. Russia really had disappeared. There was no more place to be exiled from. Exile was no longer a state of being; it was a flight—a flight into the pure glass-and-mirrored realm of the imagination, its own kind of home. ~

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/09/12/george-balanchines-soviet-reckoning?fbclid=IwAR2Z8CShHijBkMphVyU3YYL3zAfiPhiwtjc3BNM3cx3TIKWLyJoU28qtqzo

*

Soviet elections poster: "Women workers and women peasants, all to the polls." Below: "Under the red flag — in one row with men — we bring fear to the bourgeoisie!" How terribly dated this language is now. Also, let's remember that there was only one party and one candidate.

*

HOW THE WAR IS AFFECTING ORDINARY RUSSIANS (Misha Firer)

~ Russian president said to mothers of mobilized soldiers: “men live useless lives and die from vodka.”

“There’s no higher goal than to get killed in Ukraine while dispatching Ukies.”

“No greater valor than to die for motherland rather than from liver cirrhosis pooping tiny diamonds in a villa on Lake Como,” confessed propagandist Vladimir Adolphovich Soloviev.

“A man who died in Ukraine has not lived his life in vain.”

“I foresee the beginning of the collapse of the West in spring 2023,” psychic Svetlana Dragana on Channel One.

“We should reduce the world to smithereens not to face war tribunal in The Hague,” head of RT Margarita Simonyan.

“We are hitting infrastructure, and it will be destroyed. Ukraine will be sent to the 18th century,” Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Pyotr Tolstoy in an interview with French TV.

“Russia is a nuclear power, and you must understand that a nuclear power cannot lose a war. I am not threatening with nuclear weapons. West, better get ready, you will feel a lot of pain.”

“The next target after energy facilities should be banking infrastructure facilities. The goal is to sow chaos, leave Ukrainians without work, without livelihood.” General of the Russian Federation Andrey Gurulev.

That said, buckwheat is also very good. ~

Tim Kennedy:

It must take a severe kind of mental sickness to repeatedly threaten the whole world with annihilation. That includes oneself, family etc. Thanks Misha for another comic horror article.

Alan Taylor:

Sanctions relief should be tied to Russian denuclearization. Russia has repeatedly demonstrated that it is not grown-up enough to play with dangerous toys.

Alexander Paunovsky:

I have seen people being sent to mental institutions for a lot less than what Vlad The Mad is doing.

Pity.

Brad Walker:

I like how Misha chose to represent the Russian love of vodka with Stolichnaya, a brand long synonymous with Russia but which has been headquartered and made in Latvia since Putin took office and whose corporate leadership are staunchly anti-Putin.

*

Putin is a very rich man trapped in a poor man’s body and mind. ~ Warner Moelders, Quora

He

really could have just chilled and lived out the remainder of his days

on yachts with supermodels….now it seems he'll most likely experience

one of those Russian mystery deaths in the next few years. ~ Steve Bailey, Quora

It was important to Putin that he would be remembered, and he has definitely assured that will happen. ~ Daniel Aaron

Putin is presiding over the final decline of the Russian empire as it gets firmly consigned to mid-tier regional power status. A journey that Russia has been on since the dissolution of the USSR. His attempt to “make Russia great again” by invading Ukraine has fallen at the fist hurdle.

He’s going to end up being more of a footnote in history. A man who failed to stop the rot and lost a last desperate gamble. ~ Matt Clark

*

*

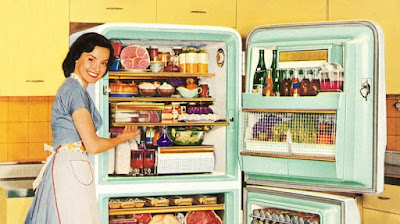

THE COOKBOOK THAT SHAPED THE IMAGE OF THE AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE

~ When my grandmother was a young girl and expressed interest in learning to bake cakes, she was gifted a copy of Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book. In 1950s America, Betty Crocker was the epitome of cake, and her cookbook was its most expert guide. With its 449 pages of recipes and photograph after photograph of bright pink chiffon cake and fluffy angel food cake, the book was impressive.

“I was starstruck,” my grandmother told me. “And I was proud that I owned it. It was my own cookbook.”

As she flipped through the book’s pages, she noticed something about the dozens of illustrations of pearl-bedecked, apron-clad women taking cakes out of the oven: “They didn’t look at all like my mother,” my grandmother, née Elena Maria Fiorello, told me. Her mother, Eleanor, was a Sicilian immigrant with a tomboy-meets-Audrey Hepburn style; she wore peg pants with ballet flats or jeans with loafers.

“I don’t think my mother owned an apron,” my grandmother said. “And she wouldn’t be caught dead in a house dress.”

Eleanor Fiorello, my great-grandmother, was an anomaly for her time in more ways than one. Much like her daughter would later do, she balanced raising children and keeping a home with a strong presence in public life. Eleanor had been forced to drop out of high school to work in a shirt factory but went on to become a respected leader in local politics, serving as a selectman and then as deputy sheriff (she was also a champion sharpshooter). As an immigrant, a woman, and an outspoken Democrat, Eleanor Fiorello was an unlikely combination in 1950s Connecticut. She still put food on the table every night—and spent hours simmering homemade red sauce on Sundays—but she hardly fit the Betty Crocker mold. And neither would her daughter.

Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book is the best-selling cookbook in American history, with approximately 75 million copies sold since 1950. Not only did it guide generations of women in the kitchen; it was a cultural force, functioning as a blueprint for what it meant to be a good wife and mother. Cookbooks are one of those banal texts that we might ignore or dismiss, but this one, like so many others‚ tells a story about U.S food and everything that is wrapped up in it: family, power, class, culture, ethnicity, gender—and what it means to be American.

When eight-year-old Eleanor arrived to the US from Sicily in 1920, anti-Italian sentiment still gripped the nation.

“There was a lot of pressure for them to assimilate,” my grandmother said of her family. “My grandfather demanded that more than anything—if his wife slipped back into being too not American, or not American enough, he would remind her that that was important.”

Her grandmother’s English was poor and heavily accented, and despite her dresses and high heels—“she looked like Betty Crocker,” my grandmother remarked—some people still stared at her as if she were “less than a human.” The family took pains to assimilate, and by the time my grandmother was growing up the message was clear: We are Americans.

Around the same time my Sicilian family arrived on the East Coast, Betty Crocker was “born” in Minneapolis to the Washburn Crosby company (what would soon merge with other milling companies to become General Mills). Betty’s birth had been something of an accident. In an advertisement for their signature product, Gold Medal Flour, Washburn-Crosby included a puzzle that readers could solve and send in for a prize. Much to the surprise of the all-male advertising team, thousands of women included letters alongside their completed puzzles, asking why their dough was lumpy or how to make their cakes rise.

The male employees were loath to sign their names to any letters in response, and so they invented a new name—Crocker for William G. Crocker, a recently retired executive, and Betty because they thought it sounded wholesome. After an informal contest among the women of the office to sign the letters, a secretary’s signature was chosen. With that, a handful of businessmen selling flour invented a fictional homemaker—and the perfect woman for the first half of the 20th century was born.

With the rise of radio in the early 1920s, Betty Crocker quickly became a star, with actresses and staff of General Mills bringing her to life on the airwaves. The arrival of World War II skyrocketed Betty to a new level of fame. General Mills distributed millions of pamphlets on the war effort, while Betty broadcast a message of community and patriotism on her widely popular radio show. In 1945, Betty Crocker was named the second-most influential woman in America by Fortune magazine—just behind Eleanor Roosevelt. At her height, she received as many as 5,000 letters per day.

Many of the women who wrote to Betty Crocker believed she was a real person. They often addressed their letters as “dear friend.” And they wrote not just of their cooking but of their marital problems, their children, sometimes their feelings of inadequacy or a lack of purpose.

For millions of women, Betty Crocker was not just a name on a cake mix: she was the guide to whom they turned for support about everything in their lives, both in and outside of the kitchen. As such, her cookbook had an unprecedented impact on women’s lives: for many, the messages that they received about how to be a wife and mother came from the trusted friend they had known for years.

By the time Crocker’s comprehensive cookbook was published in 1950, she had been a national sensation for nearly three decades. In the first weeks after the cookbook was published, it was selling a staggering 18,000 copies per week. This cookbook is 1950s domesticity incarnate: encouraging women to strive for perfection in their kitchens and to see homemaking as an “art.” But for immigrants and the children of immigrants, Betty also seemed to teach another kind of lesson.

Looking back, my grandmother explained: “Of course I was American because I was born here, but I can see that it Americanized people. I look at what a strong influence that cookbook had because it taught you how to be an American woman.”

*

A little more than ten years after receiving the cookbook, my grandmother got married at age 18, and Betty Crocker continued to accompany her in the kitchen. Meeting her husband’s Irish-American family proved to be a clash of cultures, especially around meals.

“There were certain assumptions, that my food had to be strange,” she said. “I was trying to make their food, which to me was tasteless,” she added. Her family, for their part, jokingly referred to my grandfather (David McHugh), as “Davie Mercuto,” and quickly introduced him to their homemade wine that my grandmother described only as “strong.”

My grandmother never became a Betty Crocker devotee, though the cookbook did bridge the cultural divide. After an effort to impress my grandfather with her family’s red sauce failed—he said it was good but didn’t taste like Chef Boyardee—my grandmother turned to the cookbook.

“Here I was chasing my tail trying to do something good, so I did refer to the Betty Crocker cookbook.” She made roasts—and even Irish soda bread.

But the constraints of the suburban lifestyle espoused by Betty Crocker—the mandate to have a home-cooked meal every night and new hors d’oeuvres for the dinner parties—chafed my grandmother. After her husband graduated law school, my grandmother found herself thrown into the competitive world of young lawyers. The word she used to describe this period of their lives was “plaid.” The men wore plaid pants, and the women wore long plaid skirts. In an effort to fit in, she donned the requisite plaid skirt and turtleneck sweaters at every law firm party.

“It made me feel like I was choking, because I was like my mother, and I was uninhibited like her,” she said. She soon started to wear what she wanted, to do what she wanted to do: my grandparents sometimes took their young sons out for day trips on their twin motorcycles.

After her children were grown, my grandmother started searching for more. She attended classes at her local community college, and it was there that a friend passed along an advertisement in the New York Times: Yale was accepting adult students. After a year of wavering, she applied on a whim: “I needed to prove that I could do it,” she told me.