*

A FAILED PROPAGANDA MEETING

AT CINEMA DESIRE

bouquets of red gladioli.

like an orchestra conductor,

raising my chin to mime

Long live! the political educator

strains at the top of his amplified voice —

of a few voices from the front row.

moving their lips without making a sound.

The theater is filled with classes

from several schools —

The propagandist shouts even louder,

This time a stumbling chorus

of six or seven voices.

to rouse us to the correct zeal —

then breaks into a run

barely musses the heavy gladioli.

~ Oriana

**

This is finally the right moment for this poem. Readers here can now imagine what Ukrainian schoolchildren would feel like if told to shout, “Long live Russia!” True, there was no active war between Poland and the Soviet Union at the time of this propaganda event, but there was a whispered hostility. Still, I didn’t realize to what extent we were all dissidents. The failed propaganda meeting was a revelation to me.

By the way, a poet-friend advised me to "read this poem at lot" -- while people still remember what communism was. I agree that the younger generations may not have a clear picture of the Soviet Union or much understanding of Lenin and Stalin (forget Trotsky), but now they are learning about Russian fascism and imperialism in a new way. I hope the poem remains comprehensible and oddly timely -- just as my "Eyeglasses" poem seems able to reach people who have only vague knowledge of World War 2 and concentration camps. (One American woman said to me, "To me Auschwitz seems as unreal as the Middle Ages.")

Mary:

The advice to read the poem while people “still remember” what communism was is a cogent reminder of how easily history is forgotten, or re-written. I was always amazed at my students' complete unfamiliarity with even relatively recent history, not to mention WWII. It almost seems deliberate, this degree of ignorance, almost seems designed, to serve a purpose that might be difficult to achieve if everyone knew and remembered the history that shaped the world they live in. This inability to remember certainly makes people vulnerable to the propagation of "false memories," manipulations that convince with lies, with propaganda .

Both amnesia and false memories can occur at the cultural as well as the individual levels, a culture can become deranged and delusional just like an individual.

Oriana:

I suspect that it’s not that people “can’t remember” or are unwilling to remember; it’s that they haven’t been taught even the basics. History was something that I learned tons of in school, before college. Sometimes I resented it (memorizing dates of battles was certainly pointless, aside from the handful of the really decisive ones) — but later I felt grateful for the overall knowledge, for having some idea of, say, the Roman empire, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, Reformation, and so on. It took me a while to get over the shock of how ignorant my American peers were of history, how cocooned in cliches. And yes, imagine hearing from a friend, in reaction to one of my best poems, “To me, Auschwitz is as unreal as the Middle Ages.”

But I didn’t take offense because I knew that she didn’t hadn’t been taught. She knew the gist of American history — but the rest of the world simply didn’t exist, as far as public education was concerned. It’s not the people’s fault that they hadn’t been given adequate education. But it is a shame. Some knowledge of how the modern world emerged should be a part of what every bright, educated person possesses. Among other things, it’s interesting. Fascinating even. But people who are in charge of public education, themselves poorly educated but hardly aware of how ignorant they are, don’t seem to realize that.

Clio, the Muse of History

*

VENICE: EZRA POUND AND JOSEPH BRODSKY

~ The island of San Michele, the municipal cemetery of Venice, lies less than half a mile out in the lagoon. Here Ezra Pound and Joseph Brodsky are buried in the small Protestant section. San Michele is inlaid in the water: almost a perfect square of land bordered by brick walls, in turn punctuated by white arches, with cypresses everywhere dignifying the prospect.

Ezra Pound’s grave is a simple slab lying in the ground, with only his name in the Latin style carved on it. When I visit, an overgrown bush and a vine tangle almost hide the slab, even from a short distance. I stumble around for a quarter of an hour before locating it. A gravestone can be a person’s final signature. This grave has the air of partial abandonment—symbolic for a poet so often disparaged. I move to another grave only about twenty feet away: that of Joseph Brodsky. Brodsky’s upright slab, with his name carved in both Russian and English, is exquisitely tended, with tiny, neatly arranged potted plants and a rose bush, all recently clipped. It is clearly a beloved and much visited site.

Whereas Pound consciously set out to be great, Brodsky, perhaps with more talent, set out merely to record his emotions and the material world as it appeared before his eyes. Whereas Pound was full of ideology, theories, and grand schemes, Brodsky, who served eighteen months of hard labor in internal exile in the far north of Russia—before being actually expelled from his homeland—had only contempt for such things. Whereas Pound’s pungent historical panoramas, with their emphasis on great heroic figures, leave little room for intimacy, in Brodsky’s poetry inner lives and loves, so agonizingly personal, attain almost a numinous state. Brodsky cares about the individual, not merely archetypes. With Brodsky a lover’s embrace is holy; with Pound only a bloody battle seems to be. And yet Brodsky is deeply interested in history. In a poem about the Russian military hero Zhukov, the names of Hannibal, Pompey, and Belisarius pop up in the space of only three lines. Then there is Brodsky’s famous poem about Tiberius, his essay on Byzantium, and so much more.

But Brodsky is great because no other poet, perhaps, has such an unstoppable gift for surprising and revealing metaphors. “Dust is the flesh of time”; the dental cavities of an old man “rival old Troy on a rainy day”; a dense garden is like “jewels closely set”; “darkness restores what light cannot repair.” Trying to explain his technique, Brodsky said that a poem “should be dark with nouns” on the page. Additionally, Brodsky can “see analogies where others do not suspect them,” as the poet Charles Simic wrote, and this is inextricable from his humanity. Simic called Brodsky “the great poet of travel,” saying that he “wanted to be a universal poet, someone at home everywhere, and he largely succeeded.” This is precisely why Brodsky is so crucial to Europe now—the ideal Europe at this perilous moment should yearn for. Yet my story begins not in Brussels, Paris, and Berlin—the usual datelines for writing about Europe—but in Venice.

Scores of literary greats have written about Venice, so that as Mary McCarthy once said, “no word can be spoken in this city that is not an echo of something said before.” Yet it is possible that the most unsurpassable description of Venice is Brodsky’s Watermark, which at a slender 135 pages of large print can count as an epic, for so powerful and devastating are its metaphors and asides that, while technically a work of prose, it reads like a long poem.

It is the inverse of Pound’s Cantos. Whereas that work seeks sprawling greatness and erudition and for the most part fails—despite the enormous labor and organization put into it—Brodsky’s little book hits upon perfection, even as it is clearly intended to be a minor effort. Of course, the brilliance of metaphor is usually a matter of sheer artistry, not hard labor. Just listen to Brodsky reduce the visitor’s Venice to its essentials. True happiness is “the smell of freezing seaweed” at night along “the black oil cloth of the water’s surface”; “beauty at low temperatures is beauty”; “water is the image of time”; and since music evokes time, “water, too, is choral.”

On the boat leaving the stazione, “the overall feeling was mythological, cyclopic,” the Gothic and Renaissance buildings a “bevy of dormant cyclopses reclining in black water, now and then raising and lowering an eyelid.” Marble inlays, capitals, cornices, pediments, balconies “turn you vain. For this is the city of the eye; your other faculties play a faint second fiddle.” Ergo, Venice is materialism and superficiality writ large. Physical beauty is everything here. Venice tempts idolatry.

Brodsky puts you in your place; he exposes your inadequacies by his own metaphorical brilliance, which is so matter-of-fact and almost clinical. (He hates writers and academics with “too many tidy bookshelves and African trinkets.” I am partially guilty on that score.) For Brodsky is the pinnacle: you are a dozen levels below him, at the very least. And because he is such a genius, with such precise taste (he reveres Donizetti and Mozart, not Tchaikovsky and Wagner), every offhand remark he makes carries weight.

Venice cemetery, San Michele in Isola

No doubt he would quietly sneer at my own work ethic, my neat desk, my endnotes, my anxious indulgence in analytical categories and organization, for intellects of his caliber simply don’t require any of it. Their genius can handle disorganization and rise above any system. They can even afford to be lazy (though he certainly wasn’t). They may publish sparingly, in small amounts, and leave a deeper, more lasting imprint than any of us (though, again, in Brodsky’s case his production was prodigious). As for the hardworking, incessantly striving Ezra Pound, in Brodsky’s eyes he is beneath contempt. From the viewpoint of any Russian, Pound’s “wartime radio spiels” in service to the Axis Powers should have earned him “nine grams of lead.”

I now stand over Brodsky’s grave and read “The Bust of Tiberius,” written in 1981, nine years after Pound’s death in this city. Here are some excerpts:

All

that lies below the massive jawbone—Rome:

the provinces, the latifundists, the cohorts

plus swarms of infants bubbling at your ripe

stiff sausage. . . .

. . . What does it matter that Suetonius-

cum-Tacitus still mutter, seeking causes

for your great cruelty? . . .

you seem a man more capable of drowning

in your piscina than in some deep thought. . . .

. . . Ah, Tiberius!

And such as we presume to judge you? You

were surely a monster, . . .

Pound would have been jealous. Imagine, beaten at his own game of rendering the earthen texture of history. In a portion I haven’t quoted, there is an implicit allusion to Stalin, putting the poet on firm moral ground: again, beaten. Tiberius’s obscene cruelty was, in all fairness, specific to the second half of his reign, from 23 A.D. until his death in 37 A.D., when the aged emperor—perhaps suffering from mental disease—delegated power to the Praetorian Guard. From 14 A.D. to 23 A.D., Tiberius had been a model of caution who abandoned the gladiatorial games, built few cities, annexed few territories, and used diplomacy rather than force against the German tribes. Of course, this does not weaken Brodsky’s employment of symbols to evoke unbridled power.

Ezra Pound, too, was besotted with Venice. In Canto 17, written in 1924, he writes about

the waters richer than glass,

Bronze gold, the blaze over the silver,

Dye-pots in the torch-light, . . .

In this poem the city appears as “the white forest of marble, bent bough over bough”—so what emerges is a triumph of nature and of the divine. Reading Pound’s Cantos can be like looking at an old fresco: there is the obsession with everything that is old to a naive, ideological, and therefore dangerous degree. There is, for example, the famous fixation on usury, which to him functions as nothing less than the original sin that prevents man from creating a paradise on earth. Pound, in other words, harbors a decidedly utopian streak, which almost always is perilous.

It is impossible to be blind to these tendencies, as Pound’s fascism and anti-Semitism are more than well-known—they are one of the first organizing principles one discovers about him. And this does (must, in fact) undermine his poetry. There are, for example, no mitigating circumstances surrounding Pound’s World War II radio broadcasts in defense of Mussolini. Indeed, he even praised Mein Kampf. Still, as William Carlos Williams once said about Pound’s genius: “It’s the best damned ear ever born to listen to this language!” Or as Hugh Kenner writes at the beginning of his book The Poetry of Ezra Pound (1951), in an obvious reference to Pound’s moral disrepute: “I have had to choose, and I have chosen rather to reveal the work than to present the man.”

But the demolition of Pound has continued apace. Brodsky is only one example. Such literary and intellectual personages as George Orwell, Robert Graves, Randall Jarrell, Clive James, and others—Robert Conquest, notably—have eviscerated Pound both as a person and as a poet, and in some cases they convincingly refute Kenner’s implication that the two can be disentangled. Pound’s Cantos are too often unreadable and make no sense, these poets and critics argue, and some of his translations are even bad: Pound, as one detractor has said, was like an incoherent blogger many decades before his time. And always there is his hate.

What was really at the root of Pound’s demented soul, the starting point of the moral descent that led to his playing a small part in the destruction of mid-twentieth-century Europe? Can we locate its origin in a place or a line of verse? Perhaps we may, by shifting the scene from Venice to Rimini, south of Ravenna on Italy’s Adriatic seaboard, and contemplating a particular church and the man who built it. Please bear with me.

Never does pagan Europe seem so sure of itself as at the entrance to this church. The piazza, polished and lonely in the downpour, is dramatically reduced by the line of other buildings directly at my back. So the Istrian stone encasement of an earlier brick Gothic structure thrusts itself abruptly upon me. The longer I look at it, the more extraordinary it becomes. Between the massive columns mounted on a high stylobate ledge are blind arcades guarding, in turn, a confidently deep triangular pediment. And within that triangular pediment is a lintel that I am barely aware of, yet which anchors the whole façade. Form and proportion take over. In classical architecture beauty is mathematical and equates with perfection.

Passing through the door, rather than a warm and embracing candlelit darkness, one is greeted by a shivery, pounding silence and the perpetual late-afternoon light of an overcast day. I feel like ducking back outside, under the clouds. The world at midnight is less despairing. The loud echo of another pair of footsteps every few minutes reinforces my loneliness. The expansive marble floor overwhelms the meager rows of benches approaching the apse (rebuilt after the World War II bombing). The longer I sit here, the more vast and spare the marble becomes.

More than by the scattered frescoes, I am struck by the white limestone clarity of the interior space—as of an archaeological ruin, albeit one deliberately reconstructed by early Renaissance artists. Not color, but force and volume emanate from the flattened and compressed reliefs. The feast of limestone sculptures in the side chapels takes possession of me. In the cold, these crowded and intricate figures, despite their energy, expressiveness, and flowing movement, achieve an abstract and theoretical intensity. This is art that makes you think as well as feel. It is art that offers a path back to antiquity by way of late-medieval city-states, in which communal survival superseded conventional, individualistic morality. For beauty can often emerge from the celebration of power: the very subject is a register of Europe’s past, present, and future.

This church—this temple, really—was built by Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta (1417–68), the scion of a feudal family that ruled over Rimini from the late thirteenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth, who was allied with the pro-papal Guelphs against the Ghibellines (supporters of the Holy Roman Emperor). Malatesta was a condottiere, that is, a mercenary captain, because he operated according to a contract, a condotta. The ultimate man of action, he lived for years on end under a death sentence in one form or another: he sold his truly remarkable military skills to one city-state after the next, and in the end he lost most of his own city-state of Rimini in the bargain. His image was publicly burnt in Rome. The popes were after his lands, the Medici bank after his money, and yet in spite of his constantly changing alliances and his weakness against the great powers of the papacy, Venice, and Milan—despite defeat, disgrace, and betrayals—he transformed this Franciscan Gothic church into one of the most arresting of Renaissance temples, a “Tempio Malatestiano” filled with bas-reliefs of pagan gods, in order to glorify himself and his longtime mistress and later wife, Isotta degli Atti.

Malatesta was an eruption of life in its most elemental and primitive form: someone who, as several historians have suggested, was without conventional morals, yet who came armed with unlimited supplies of energy and heroism.

For Ezra Pound, Sigismondo Malatesta was the perfect “factive” personality, that is, a symbol of manhood in its entirety, a figure both brutal and treacherous, even as he was supremely cultivated in the arts. Malatesta, in Pound’s formation, represents a harmonious whole created from dissident elements: a personality “imprinting itself on its time, its mark surviving all expropriation,” as Hugh Kenner writes. In Pound’s rendering, Malatesta is a man of virtù—less because of his swashbuckling derring-do than because of the fact that he actually restored and decorated this temple, making it such a perfect work of art. It is the Tempio Malatestiano itself—an epic in its own right and an act of sheer will, much like Pound’s own Cantos—that raises Malatesta above all the other rogues and fighting men of his time. Malatesta’s military exploits would have been wasted, pointless, were it not for the work of art that emerged from them: this tempio. Imperialism and war, in Pound’s view, can only be justified by art. For it is the artistic epic that permits civilization both to endure and to begin anew.

Pound devotes several of his early and most well-known cantos to Sigismondo Malatesta, whom he idealizes with so much biographical detail that the poems (and this is a serious issue with the Cantos in general) “decline into catalogue” in places, in the estimation of the Pound biographer Humphrey Carpenter. Pound in Canto 9 calls Malatesta “polumetis,” a Homeric adjective meaning “many-minded,” a reference to the adaptability and resourcefulness of Odysseus himself. For Malatesta’s adventures are in Pound’s eyes quite comparable. Pound is simply infatuated with Malatesta: the Italian is the toughened warrior whom he critiques but with whom he identifies.

Just as Malatesta was a patron of the arts and of philosophy, Pound, consciously modeling himself after his hero, was well-disposed toward other writers and artists. There was clearly a Malatesta-like gallantry to Pound’s own efforts. Pound famously tried to help James Joyce find a publisher for Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and, later, a magazine to serialize Ulysses. This was at a time when Joyce was living in exile in near-poverty in Trieste.

Pound also assisted T. S. Eliot in publishing “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” It was Pound who had helped discover Eliot, in fact, and who, as we all know, edited The Waste Land. Pound grasped early on both the artistic potential and the epic quality of the work of both writers. For Pound, manly risk was almost inseparable from the creation of the artistic tour de force: thus the image of the larger-than-life, violent Malatesta, who helped produce this masterpiece of a temple where I ache in the cold, ironically became central to Pound’s own nascent fascism. In fact, Pound’s infatuation with Mussolini, another Italian man of action, can be traced directly to his infatuation with Malatesta. With Malatesta, Pound turned a corner in a disastrous direction.

Pound’s writing in the Malatesta Cantos is superficially infectious. It is panoramic and relentlessly obscure, sending you constantly to the encyclopedia. I’ll never forget reading Canto 9 for the first time as a young person, and coming back to it periodically over the years. For it begins mid-gallop, in wide screen:

One year floods rose,

One year they fought in the snows, . . .

And he stood in the water up to his neck

to keep the hounds off him, . . .

And he fought in Fano, in a street fight,

and that was nearly the end of him; . . .

And he talked down the anti-Hellene,

And there was an heir male to the seignor,

And Madame Ginevra died.

And he, Sigismundo, was Capitan for the Venetians.

And he sold off small castles

and built the great Rocca to his plan,

And he fought like ten devils at Monteluro

and got nothing but the victory

And old Sforza bitched us at Pesaro; . . .

And he, Sigismundo, spoke his mind to Francesco

and we drove them out of the Marches.

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, 1417-1469, by Piera della Francesca

I am quoting but fragments of a canto that goes on for eight long pages, assaulting the reader as it does with a deluge of factual minutiae that, however admirably researched, sometimes border on the incomprehensible (at least for the layman) for lack of context; yet they are at once both aromatic and cinematic, even as they express within Malatesta’s own person the evil, wasteful forces of an entire age. Whether this makes for good—that is, disciplined—poetry, I am not sure. There is an air of dilettantism about it. Kenner rises to Pound’s defense: “This was a poetry of fact, not of mood or response, or of disembodied Overwhelming Questions.” I have grown out of much in life, but never out of what I consider the very best of Ezra Pound’s sometimes very bad poetry—which is evident in his early cantos, before he lost his way.

Back to Venice. To be buried here is a signal honor, and no one can deny Pound’s influence on twentieth-century poetry. But this is a case in which the very condition of the two gravestones indicates a moral and artistic hierarchy. Pound, with his obsession with the strong man of action and manly virtù, now represents the authoritarian vision, lately manifested by Russia’s Vladimir Putin, whose political and economic shadow continues its ascent over Europe. Contrarily, Brodsky, the dissident Russian, concerned with universalism and the personal life of the individual, represents a Europe of sovereign, mutually respectful nations, and the rule of law over arbitrary fiat. Here in this Venetian cemetery, two iconic forces stand a few feet apart from each other. Here are the two paths that Europe can tread. May it choose the right one.

https://newcriterion.com/issues/2022/3/idol-temptations-on-the-adriatic

Mary:

Venice 1964; Ikko Narahara

*

SVIATOSLAV RICHTER’S TOUR OF SIBERIA

~ In 1986, Richter embarked on a six-month tour of Siberia with his beloved Yamaha piano, giving perhaps 150 recitals, at times performing in small towns that did not even have a concert hall. It is said that after one such concert, the members of the audience, who had never before heard classical music performed, gathered in the middle of the hall and started swaying from side to side to celebrate the performer. (~ Wiki)

Oriana:

Isn’t this a wonderful anecdote? Starting of course with the fact that this world-famous piano virtuoso and conductor, born in Odessa, was willing to give concerts in small towns in Siberia.

*

IVAN ILYIN’S CHRISTIAN FASCISM: A MYSTICAL VISION OF RUSSIA’S GREAT DESTINY

~ A key figure in shaping Putin’s ideas on [Russia’s destiny] is Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954), a philosopher who left Russia after the Russian Revolution and lived most of his life in Germany and Switzerland. Putin routinely quotes Ilyin, has instructed Russian elites to study his writings, and has brought Ilyin’s archives from Michigan State University and his remains from Switzerland to Russia.

In Ilyin’s view, Russia is an innocent and pure nation that has repeatedly been victimized by invasions and the infiltration of alien ideas designed to weaken and destroy the nation. As outlined by Western historians such as Timothy Snyder, Ilyin provided a metaphysical and moral justification for an authoritarian state of the sort that Putin is now trying to build.

Such a state rejects representative democracy and the rule of law as direct threats to Russian purity. Instead, what’s needed is an indomitable leader, fortified by strong Russian Orthodox spirituality, who is unafraid to take brutal action to repel foreign enemies and root out domestic ones.

For Putin and his followers today, Ilyin has become something of a guru with a road map to a fiercely proud, spiritually pure, unconquerable Russia of the future.

The view of Russia as the perpetual target of alien enemies has been touted by many Russian thinkers other than Ilyin. And popular memory in Russia is in sync with such notions. Most Russians can easily reel off a list of invasions such as the Mongols in the 13th century, the French in the 19th century, and the Germans in the Great Patriotic War, as Russians call World War II, to name just a few.

These accounts have coalesced into a general narrative template about how an alien enemy invades and nearly destroys Russia, but eventually is repelled by the sacrifice and heroism of Russians. This way of thinking is reinforced daily through stories from parents, schools, the church and the media.

The narrative encourages Russians to see existential threats from armies and ideas where others do not. It was the tool Putin used in 2008 to justify a massive invasion of Georgia, a small country of 3.7 million, which he viewed as the tip of a Nato spear aimed at the heart of Russia.

In Georgia then, and in Ukraine today, the existential threat that Putin sees is the model they present of rising democracies that could tempt the Russian population to question their own government.

It is reasonable to wonder why Putin, and Ilyin before him, rely so heavily on Christianity as an essential part of defending Russia. This, too, is an old idea in Russia. Most Russians today are very familiar with the notion of Moscow as the “Third Rome”, as formulated by the monk Filofei of Pskov in 1510.

The assertion is that after corruption and moral decay caused the downfall of Rome and then Constantinople, Moscow rose to become the center of pure Christianity.

This idea comes as a surprise to most Western readers, but that is the point. Without knowing about this narrative and the tenacious hold it has on Russian thinking, we miss the context which holds clues to what Putin wants in Ukraine – and beyond.

This is not to say that Putin’s actions are wholly driven by Christian fascism. Like any leader, he must also worry about the real, practical world. Russians, like people everywhere, are generally less interested in philosophy than in the price of food and rent and how their children will fare in years ahead.

The grand idealistic mission Putin sees for Russia is one that triumphs over democracy and encourages the rise of Christian fascism everywhere. It may take decades or even centuries to fulfill, but it provides a backdrop for decisions in the present.

The good news for the West is that the handiest argument against such mystical yearnings is hardcore pragmatism. People need to eat and pay rent. Economies need investment and development. Possibly, the West’s threat of major new sanctions may tip the balance.

In the long run, though, we would do well to remember that, in Russia, there is an animating grand narrative behind most decisions. Putin did not invent this narrative, and the narrative will not die with him. Whenever we try to predict Russia’s next move, we must try to game it out through a very Russian mindset. ~

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3167918/grand-narrative-driving-putins-vision-strong-and-spiritually-pure

~ At first, Ilyin perceived the February Revolution as the liberation of the people. Along with many other intellectuals he generally approved of it. However, with the October Revolution complete, disappointment followed. On the Second Moscow Conference of Public Figures he said, "The revolution turned into self-interested plundering of the state”.

Later, he assessed the revolution as the most terrible catastrophe in the history of Russia, the collapse of the whole state. However, unlike many adherents of the old regime, Ilyin did not emigrate immediately. In 1918, Ilyin became a professor of law in Moscow University; his scholarly thesis on Hegel was published.

After April 1918, Ilyin was imprisoned several times for alleged anti-communist activity. His teacher Novgorodtsev was also briefly imprisoned. In 1922, he was eventually expelled among some 160 prominent intellectuals, on the so-called "philosophers' ship". He settled in Berlin, and later in Zurich.

In exile, Ivan Ilyin argued that Russia should not be judged by what he called the Communist danger it represented at that time but looked forward to a future in which it would liberate itself with the help of Christian fascism. Starting from his 1918 thesis on Hegel's philosophy, he authored many books on political, social and spiritual topics pertaining to the historical mission of Russia. One of the problems he worked on was the question: what has eventually led Russia to the tragedy of the revolution? He answered that the reason was "the weak, damaged self-respect" of Russians.

As a result, mutual distrust and suspicion between the state and the people emerged. The authorities and nobility constantly misused their power, subverting the unity of the people. Ilyin thought that any state must be established as a corporation in which a citizen is a member with certain rights and certain duties. Therefore, Ilyin recognized inequality of people as a necessary state of affairs in any country. But that meant that educated upper classes had a special duty of spiritual guidance towards uneducated lower classes. This did not happen in Russia.

The other point was the wrong attitude towards private property among common people in Russia. Ilyin wrote that many Russians believed that private property and large estates are gained not through hard labor but through power and maladministration of officials. Therefore, property becomes associated with dishonest behavior.

In his 1949 article, Ilyin argued against both totalitarianism and "formal" democracy in favor of a "third way" of building a state in Russia.

Facing this creative task, appeals of foreign parties to formal democracy remain naive, light-minded and irresponsible.

For Ilyin, any talk about a Ukraine separate from Russia made one a mortal enemy of Russia. He disputed that an individual could choose their nationality any more than cells can decide whether they are part of a body.

All these factors led to egalitarianism and to revolution. The alternative way of Russia according to Ilyin was to develop due "consciousness of law" of an individual based on morality and religiousness.

Ilyin developed his concept of the "consciousness of law" for more than 20 years until his death. He understood it as a proper understanding of law by an individual and ensuing obedience to the law.

Ilyin was a monarchist. He believed that monarchical consciousness of law corresponds to such values as religious piety and family. His ideal was the monarch who would serve for the good of the country, would not belong to any party and would embody the union of all people, whatever their beliefs are.

However he was critical of the monarchy in Russia. He believed that Nicholas II was to a large degree the one responsible for the collapse of Imperial Russia in 1917. His abdication and the subsequent abdication of his brother Mikhail Alexandrovich were crucial mistakes which led to the abolition of monarchy and consequent troubles.

VIEWS ON FASCISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM

A number of Ilyin's works (including those written after the German defeat in 1945) advocated fascism, Ilyin initially saw Adolf Hitler as a defender of civilization from Bolshevism and approved of the way Hitler had, in his view, derived his antisemitism from the ideology of the Russian Whites. In 1933, he published an article titled "National Socialism. A New Spirit" in support of the takeover of Germany by Nazis.

Ilyin was accused of antisemitism by Roman Gul, a fellow émigré writer. According to a letter by Gul to Ilyin, the former expressed extreme umbrage at Ilyin's suspicions that all those who disagreed with him were Jews.

Ilyin's views influenced other 20th-century Russian authors such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Aleksandr Dugin as well as many Russian nationalists. As of 2005, 23 volumes of Ilyin's collected works have been published in Russia.

The Russian filmmaker Nikita Mikhalkov, in particular, was instrumental in propagating Ilyin's ideas in post-Soviet Russia. He authored several articles about Ilyin and came up with the idea of transferring his remains from Switzerland to the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow, where the philosopher had dreamed to find his last retreat. The ceremony of reburial was held in October 2005.

Ilyin has been quoted by Russian President Vladimir Putin, and is considered by some observers to be a major ideological inspiration for Putin. Putin was personally involved in moving Ilyin's remains back to Russia, and in 2009 consecrated his grave. ~

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Ilyin

“Politics is the art of identifying and neutralizing the enemy.” ~ Ivan Ilyin, 1948

“The Russian looked Satan in the eye, put God on the psychoanalyst’s couch, and understood that his nation could redeem the world.” Timothy Snyder, “God is a Russian” ~

https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2018/03/16/ivan-ilyin-putins-philosopher-of-russian-fascism/

Ivan Ilyin

*

TIMOTHY SNYDER’S VIEWS ON ILYIN

~ Ilyin’s theoretical works argued that “the world was corrupt; it needed redemption from a nation capable of total politics; that nation was unsoiled Russia.” Ilyin’s, and Putin’s, Russian nationalism has had a paradoxically global appeal among a wide swath of far right political parties and movements across the West, as Snyder writes in his latest book, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America. “What these ways of thinking have in common,” write The Economist in their review of Snyder’s book, “is a quasi-mystical belief in the destiny of nations and rulers, which sets aside the need to observe laws or procedures, or grapple with physical realities.”

Ilyin, Snyder says, is “probably the most important example of how old ideas”—the fascism of the 20s, 30s, and 40s—“can be brought back in the 21st century for a postmodern context.” Those ideas can be summarized in three theses, he says, the first having to do with the conservative reification of social hierarchies. “Social advancement was impossible because the political system, the social system, is like a body… you have a place in this body. Freedom means knowing your place.”

“A second idea,” says Snyder, relates to voting as a ratification, rather than election, of the leader. “Democracy is a ritual…. We only vote in order to affirm our collective support for our leader. The leader’s not legitimated by our votes or chosen by our votes.” The leader, instead, emerges “from some other place…. In fascism the leader is some kind of hero, who emerges from myth.” The third idea might immediately remind US readers of Karl Rove’s dismissal of the “reality-based community,” a chilling augur of the fact-free reality of today’s politics.

Ilyin thought that “the factual world doesn’t count. It’s not real.” In a restatement of gnostic theology, he believed that “God created the world but that was a mistake. The world was a kind of aborted process,” because it lacks coherence and unity. The world of observable facts was, to him, “horrifying…. Those facts are disgusting and of no value whatsoever.” These three ideas, Snyder argues, underpin Putin’s rule. They also define American political life under Trump, he concludes in his New York Review of Books essay.

Ilyin “made of lawlessness a virtue so pure as to be invisible,” Snyder writes, “and so absolute as to demand the destruction of the West. He shows us how fragile masculinity generates enemies, how perverted Christianity rejects Jesus, how economic inequality imitates innocence, and how fascist ideas flow into the postmodern. This is no longer just Russian philosophy. It is now American life.” There are more than enough homegrown sources for American authoritarianism and inequality, one can argue. But Snyder makes a compelling case for the obscure Russian thinker as an indirect, and insidious, influence. ~

https://www.openculture.com/2018/06/an-introduction-to-ivan-ilyin.html

Highly worth watching:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s31VFwO-6u0

Joe: THE PARADOX OF WAR

War turns love of country to anger at the enemy to hatred of the opposition. Hatred leads to a joyous killing of the enemy, then, remorse, finally, self-loathing (PTSD). ~ Preacher, a homeless veteran

To prevent ourselves from dealing with this statement, we hide it in religious and political behavior. The Ku Klux Klan is one example of this behavior. They wear masks like a uniform that hides their faces. This face covering identifies them as a member keeping them safe from mistaken identity and friendly fire. Also, it prevents them from seeing their comrade’s reaction to torture and murder.

By wearing masks and terrorizing at night, they can pretend their criminal acts are good. Their conscience knows the difference. Therefore, they self-medicate by drinking and bragging about their deeds. They reiterate false logic to cloak their remorse. I served in the Army and worked in construction with whites with varying levels of bigotry. Many times, I heard: African-Americans are like children. They expect whites to punish them like parents.

I called it whiskey logic. Yet those men refused to acknowledge the equality of all men so long as they remained in their group. They quoted their preacher, who supported and sanctified their bigotry. He asked them to join in a war against God’s enemies. Because (white) Christians were the chosen, they must destroy the patrons and the clinics offering prenatal care. They must give tough love and punish those incapable of moral decisions.

It seems Christian racists celebrated the bombings of women’s health clinics like the United States rejoiced in the bombings of Dresden, Hiroshima, and Vietnamese villages. Blinded by his bigotry, the preacher failed to notice his turn away from Christ’s love. Imperceptibly, his anger grew to hatred towards those called God’s enemies. Then, his church joined him in an almost unconscious but mutually desired conduct.

Christ’s love and God’s love becomes an idea of love without sacrifice. Without love, we can’t make the sacrifices needed to relieve the social/economic problems leading to abortions. If we use racism to prevent ourselves from loving, is it possible to follow Christ’s example and comfort people? On the other hand, Christian love does not give us that joyous surge that killing in the name of God and country does.

How strange the joy of killing is — and it seems it is at its strongest when racist behavior initiates it. Using a Holy Text to sanctify racism is not only a Christian behavior. Every country in modern times goes to war with the blessing of its religious leaders. Fighting for God & Country against the enemies of God and Country is what racists insist they do. It doesn’t matter if the racist is Christian, Muslim, Hindu, or Jewish.

Our Trojan Horse is the psychological tie between religion and country: racism and war. It allows racist beliefs to worm their way unnoticed into our hearts and against our wishes. When people point out our racist behavior, we hide behind the same racist clichés used to defend God and war: You don’t see how good our God or our country is to you. You haven’t experienced God’s love or our country’s love.

Oriana: LOVE THY ENEMY

That last sentence reminded me of an article I read years ago, trying to explain the decline in religion: people leave the church because they have failed to experience the love of Christ. But obviously the statue on the cross is not going to love them; the ideal he stands for — and presumably died for — must be embodied in how the living treat one another.

Much has been written on the psychology of bigotry: the need to feel superior to someone, anyone. And ignorance. You can’t really know people in any depth and deny that, first of all, they are just people like you. They can rise to being heroic, and they can be sucked in by the downward spiral. They rejoice, they despair. And their greatest weakness — our universal greatest human weakness — is susceptibility to falling for abstractions used to justify wars.

Historians have noted that aeons ago wars needed no moral justification. If there was an opportunity to grab some land or sack a city, why not. But Christianity imposed a certain moral requirement to justify a predatory behavior that went counter to the pacifism of Jesus. LOVE THY ENEMY! IMAGINE THAT!

Alas, the human mind can always manufacture some “divine mission.” Russia, the Third Rome, must save the world from the decadent West. By the same token, America must save the world from Godless Russia. And so it goes . . .

*

another great influence on Putin: the neofascist ideologue Aleksandr Dugin:

“Dugin’s mix of fascist and Soviet communist ideas make use of a scholarly façade, but behind this lie Christian notions of good and evil, as well as references to the occult and myths that also obsessed the Nazis, including Atlantis.

Dugin’s messianic narrative of a sacred mission sees the West as the Antichrist and Russia as being akin to the Roman empire.

Dugin envisages a “new world” centered around Russia, and Putin’s victorious press release about Ukraine was similarly titled the “offensive of Russia and the New World”. According to Ukraine’s Page News, its proud publication had been scheduled for two days after the Ukraine invasion. With efficiency typical of the Soviet era, somebody forgot to remove it from the automated timer function.

The fight is far greater than we imagine. The goal for Putin and his ideological guru, Dugin, is “new world” dominance with the reversal of progress. Ukraine is just the tip of the iceberg.

Some would describe Dugin’s philosophy as a death cult because he seeks the total destruction of his opponents.”

Aleksandr Dugin. Note the portrait of the last Tzar.

Mary:

Snyder’s analysis of what drives Putin seems chillingly correct. It is a brand of fascism at one with far-right evangelism, with the Messianic sense of mission determined to reverse progress, freeze and make permanent social hierarchies that allow no movement, and establish, or as Fascist evangelism would see it, fulfill, Russia's destiny as a world-dominating power. And yes it is much like the Evangelical Fascism of the Trumpists. Trump and Putin's programs share the same slogan even, the goal to “Make (America/Russia) Great Again.” The first enemy to be defeated is democracy...wherever it may exist.

Another thing that seems similar to me is that after the fall of the Soviet Union there was a promise people felt went unfulfilled...Not everyone had a better life; for many it was worse. Income inequality increased in the same dangerous way it did, and continues to do, in the US. People feel cheated, disappointed, ready for change. No matter how they get it.

One way is to leave Russia for the West...in droves. In this country we have Trump and his contingents, the rural folks who feel left out and threatened by progressives, and robbed of that great promised American Dream of success, backed and egged on by the wealthy one percent, who want only to increase their own wealth and power. The dynamic is similar — mostly rural, very disappointed people, a very wealthy and powerful one percent with their own agenda, and the megalomaniac leaders seen as having Messianic missions to fulfill.

Messiahs are ruthless as gods. Witness Ukraine.

Oriana:

The critical word in the MAGA slogan is AGAIN. There was a time when we were great; then an enemy, internal (e.g. the liberals) or external (in Russia's case, the West) took our greatness away. Full speed back to the mythical past that never was!

I want to throw up my hands. Democracy is messy and inevitably full of mistakes. It’s not a glorious vision of a powerful empire that goes from victory to victory, from wealth to more wealth — with no embarrassing problems like the homeless, say (true fascism, by the way, would simply kill the homeless, especially those unfit for military duty).

Democracy and human rights, and especially women’s rights — it seems that the battle is never won. For one naive moment, we thought that all this was settled a century ago, if not earlier. But there is the frustrated dream of greatness, if not personal, then national and/or military — a perennial problem to which we have not managed to find a solution.

M. IOSSEL ON RUSSIA'S DELUSIONAL VIEW OF ITSELF

Nothing will ever be the same again. Russia will never be called a "great country" in the surrounding world, and also in Russia itself, it will never be called "a great country," even more so -- a "superpower." "She lost the right to it.

Russia, of course, has no right to sit in the Security Council, as it itself is the main threat to security in the world.

Russia under Putin had been inching towards the edge of the bottomless abyss of fascism for quite a while — and then the country just fell into it, head first.

*

POST-SOVIET EUROPE; THE TRANSITION WORKED OUT BETTER FOR SOME COUNTRIES AND SECTIONS OF THE POPULATION

“Revolutions in Eastern Europe and the USSR three decades ago gave hope to those societies that democracy and capitalism will lead to better life. For a lot of people, this did not happen — and their justified frustration now feeds reactionary anti-democratic forces in countries like Hungary, Poland, Russia, or Germany, argues American researcher Kristen Ghodsee.”

~ Taking Stock of Shock: Social Consequences of the 1989 Revolutions, a recent book Ghodsee co-wrote with Mitchell Alexander Orenstein, gives a comprehensive 30-year review of how the societies of 27 post-socialist countries survived transition to market economy.

Using economic, demographic, polling data and ethnographic research, the book traces a complex and ambiguous landscape. Although many in the region today can enjoy freedoms, opportunities, and standards of living unavailable to previous generations, this is by no means true for all. Even after recovering from the deep economic recession of the 1990s, these societies remained traumatized by the transition, as evidenced by drops in life expectancy, rise in alcoholism, and dramatic rates of emigration. “The social impacts of transition were severe, despite frequent attempts [...] to deny this,” conclude Ghodsee and Orenstein.

In an interview with LRT.lt [Lithuanian Radio and Television], Ghodsee, who is a professor of Russian and East European studies at the University of Pennsylvania, discusses why disappointment with capitalism gives rise to right-wing movements even in nominally successful post-socialist countries, what is at stake in Eastern Europe’s memory wars, and why women had better sex under socialism.

You’ve been working quite a while in Eastern Europe, mostly in Bulgaria. How do people there relate to their history of socialism and of the transition to market economy?

I happen to be old enough that I was in Eastern Europe in the summer of 1990. I was actually in the GDR right after the Berlin Wall fell, before it ceased to exist. And I traveled extensively through the region.

I’ve watched for the last 30 years as the narrative has developed and changed. Obviously, in the immediate aftermath of 1989, and 1991 in the former Soviet Union, there was this real happiness and euphoria around democracy and capitalism, and the end of these oppressive states with centrally planned economies, shortages, travel restrictions, and secret police. There was a real sense of hope – that there would be this thing called “the peace dividend”, that the world would be a more equitable and peaceful place.

And that didn’t happen. I also think that there was a concomitant feeling that life for ordinary people in most of these former socialist countries would improve substantially. And these hopes met with reality, a very unfortunate reality, throughout the 1990s.

And so, I think there’s a lot of amnesia around the transition, partially because it was so painful, partially because there really hasn’t been any systematic regional analysis of the last 30 years. I would argue that this book was really the first attempt to do an interdisciplinary analysis of 27 countries over the last 30 years.

What we see is a complicated story. The transition was really good for some people and it was really bad for a lot of others – and it remains bad for a lot of people. The problem with the narrative is that the winners get to tell the story. And the losers, their voices are just lost.

And to the extent that we hear the losers, we hear them at the polls in Hungary and Poland, in places where there are more right-wing governments coming into power. They’re often discredited as backward or nostalgic, uneducated, rural voters. There are all sorts of ways in which these voices are marginalized, because they’re basically speaking to the fact that the last 30 years of democracy and capitalism didn’t turn out quite the way that people in 1989 or 1991 thought they would.

Which promises in particular would you say were frustrated and undelivered?

I would say that, first of all, the promise of democracy. There was a hope about the future, that you wouldn’t just have the creation of oligarchs – in some countries, they never really even pretended to have a democracy.

Other countries really did build democracy. But if you read Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes’s book The Light That Failed, they argue that you could elect governments in Eastern Europe that still had to do whatever Western governments or the EBRD, the World Bank, or the IMF told them to do. They were told to implement these reforms, or implement certain kinds of austerity measures, or implement a flat tax, or whatever.

That wasn’t really democracy. You had elections and then the leaders that you elected had to do what the West said no matter what, so there was a disconnect between the discourse of democracy, self-determination and independence, and the reality of doing what the West told you to do. I think that’s a big problem, people were very disappointed, and they expressed that anger very early on.

The other real issue is the economic one. We’ve seen an incredible amount of income inequality arise in that region, partially as a result of the capture of many of the formerly state-owned resources by a new class of oligarchs. We see an increasing percentage of national wealth going to the top one percent.

We found in our book that at the peak year of poverty, which was in 1998, there were 191 million people in the former socialist world living on less than 5.5 dollars a day, which was the World Bank poverty rate for Eastern Europe at the time. That’s almost half of the region in poverty. Much more than there had been before the transition.

And so, if you think of it in those terms, both capitalism and democracy failed to deliver on their promises. A lot of people were angry and disillusioned. And I think that a lot of the frustration that you see in the region today is not only about the way that the transition has been carried out, but also a reaction to the dominant narrative of economists and liberal elites insisting that the transition, in fact, has been successful. There’s this constant insistence that we’re way better off than we were before, that it’s not even worth talking about the past. We’re going to blow up all these monuments and change all these street names and pretend like that didn’t happen. I think that a lot of people are just really frustrated by that.

Are there any significant variations across the region, say, between former Soviet republics, Warsaw Pact countries in Eastern Europe, former Yugoslavia?

It really depends on which indicators you’re looking at: the economy, demography, public opinion, everyday life experiences. It’s very different for different regions. The one thing that I will say is that there are some interesting regional patterns.

From a demographic point of view, we see a massive population decline. Demographers call it the “demographic death spiral,” where countries are hemorrhaging people either because of high death rates, low fertility rates, or massive out-migration – in the worst case, a combination of all three. And Lithuania, I think, has got the second fastest shrinking population in the world.

The demographic problem is just not the same in Russia and in Central Asia. It’s horrible in places like Latvia, Lithuania, Bulgaria and Romania; there’s massive hemorrhaging of population in Croatia, Slovenia, too. The migration crisis has hit harder those countries that are closer and more integrated into Europe than it has hit countries further away.

We also see a big difference between vodka-drinking cultures and wine-drinking cultures. Particularly when we look at the male mortality crisis, it tends to be concentrated in what we call the vodka belt (Russia, Ukraine). And because of their high male mortality, it also has a depressive effect on fertility. Whereas in Central Asia, they’re actually having a baby boom, because they don’t drink and tend, for cultural reasons, to have lots of children.

Moreover, obviously, some countries have natural resources, other countries do not. Some countries are more economically developed. Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, Slovenia had a bigger industrial base, they’ve really done well economically. But they’re still facing a massive population decline. They are still hemorrhaging young people. They’re still hemorrhaging doctors and nurses. Young people still want to make their lives in the West rather than staying at home.

In your book, you look at economic indicators, GDP growth – which seem to show a picture of growth and development – but on the other hand, even “successful” countries are hemorrhaging their populations. So what’s the story there, what is hidden behind the GDP?

Inequality is what’s hidden there. It’s very clear. I have the statistic here: in 1990, 6.14 percent of Lithuanian wealth before taxes and transfers went to the top one percent. By 2015, that figure is 10.18. That’s a pretty large gap, one tenth of national wealth goes to one percent of the population. And that’s really visible in a small country. And so, GDP per capita hides income inequality.

And to the extent that people look at GDP per capita as an indicator of economic success, they’re ignoring the fact that a lot of people have, to this day, a worse standard of living than they did prior to 1989 or 1991. That’s a huge story that we don’t hear.

And I think it’s important to highlight this inequality. I mean, Lithuania is not as bad as Russia or Romania in terms of inequality, but it’s also a lot worse than Albania or Slovakia. It’s in the middle of the pack and people feel inequality very differently.

Sure, a lot of people are better off than they were before 1989 or 1991, there’s no doubt about that, especially if you were a young person who left Lithuania in the 1990s and made a life for yourself in England or the United States or Germany. Your life is just way better than your parents’ or grandparents’. I don’t think there’s any question about that. But for all those people living in the villages in eastern Lithuania where some of this massive depopulation is happening – their lives aren’t better off, and they really feel it. And, at the end of the day, they vote.

So I think it’s essential to not only look at the economic indicators – demographic indicators also tell you a story, which is that if I were a young person, I wouldn’t want to live in Lithuania or Bulgaria, I’d have a better life in the West. And I think that tells you that this is not an ideal, democratic capitalist society, because if it was, people would want to stay and have babies.

And not only young people feel the pressure to leave. I lived in Serbia, Belgrade, for a month last November. Some of my colleagues there, female professors around my age, they too are feeling pressure to migrate. They see their friends do it. Their children are now going off to university and they feel like, okay, now I can move to Germany or the UK, because they don’t need me here anymore. And so this pressure is ubiquitous in these societies – if you’re anybody, you get out.

That’s not a healthy society. That’s not a sustainable society in the long run. If anybody who has intelligence and initiative and drive feels like their opportunities are better in another country than in their own country – I think that’s a real problem. And that is a reflection of the disappointments of the last 30 years.

Do you think the recent backsliding of democracy in Poland and Hungary are also linked to this botched transition?

Absolutely. Unequivocally. And in former East Germany, the Alternative für Deutschland party actually uses the slogan “Vollende die Wende”, complete the change. Part of their campaign strategy has been to stir up people’s anger about the reunification and the loss of East German culture.

Definitely, there’s anger and frustration in places like Poland and Hungary, which, by the way, are countries that did well in the transition. Economically, data shows that they were some of the most successful countries. But they’re facing this backlash precisely because people were promised a certain bill of goods. And they didn’t get it. In 1990, Helmut Kohl, who was the chancellor of Germany at the time, told East Germans – and implicitly he told Eastern Europeans – no one will be worse off than before, but it will be much better for many.

And it wasn’t true. Many people were better off, but the vast majority of people were worse off. In our book, we basically say that if you look at all 27 countries over the last 30 years, about a third of the population did really well, and about two thirds of the population did poorly, meaning that they either have the exact same standard of living or worse than they did in 1989 or 1991.

Why do people who feel left behind then go and vote for the far right or nationalists?

Because there are no leftist parties in Eastern Europe, or they’re very few. To people in Eastern Europe, communism or socialism or any kind of leftist redistributive politics is totally anathema. So to the extent that there are redistributive politics, it’s taking the form of nationalism.

If you look at the platform of the Law and Justice party in Poland or Orban policies in Hungary they both have interesting redistributive socialist aspects, but they’re wrapped in the language of nationalism. So I just think that in Eastern Europe redistribution is more palatable if it’s done under the banner of the far right, rather than the left, let alone far left.

But is that constructive? Will the nationalists really deliver?

No, of course not. They never do. They always use the language of populism to shore up the economic and political interests of the elites, that’s just the way it works.

There may be some good policies. Look at Poland, what is called the Family 500+, which is a redistribution program to give money to Polish women who have children. It’s not that different from what they did under socialism. At the same time, they’ve banned abortion, and women have to stay home. It is a very conservative policy, but it turns out that it’s very popular, especially in rural areas.

So the nationalists don’t completely abdicate responsibility – some of the policies that they propose, they actually do it. And we have some evidence, for instance, that child poverty in Poland has in fact been reduced by this. So they’re not completely disingenuous, but, given the abortion politics, for the most part you can’t really trust these far-right parties, because their agenda is different from what they say it is.

Another important strand of your work is about women’s rights. One of your books is called, intriguingly, Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism. What is your main argument?

My thesis is basically that socialist countries got some things right. They got a lot of things wrong. I’m not trying to whitewash it. I’m very clear that I recognize the secret police, the travel restrictions, the shortages, censorship and things that were wrong with these societies. But there were some things that they got right. And one of the things that they got right, I think, was the promotion of gender equality, women’s equality very specifically, and the support for the family.

People had babies in Soviet Lithuania. It does tell you something about the world when there were people having babies – and then people stopped having babies. Why? Especially given that, as we know, abortion was legal on demand in the Soviet Union, before and after the Stalinist era, and that many Soviet women had four or five abortions in their lifetime. So it’s not like it was in Romania, where there was no birth control or access to reproductive freedoms after 1966. In Lithuania, there were plenty of opportunities to terminate a pregnancy if you wanted to, and yet people still had babies.

So that tells you that there was something about that society that made people feel comfortable enough, that made them care enough about the future, that they were ready to bring children into the world. And so my argument is simply that we shouldn’t discount some of the policies that were put into place that supported women as workers and mothers, and which supported families.

It could be as simple as, well, everything else in life sucked, so the only thing we could do was have sex and hang out with our friends and family in dacha and drink vodka. Fine, you could say that this might be part of what was going on. And now everybody’s hustling. We all want to go on vacation to Ibiza or are working three jobs, nobody has time for kids. And it’s better because we have more stuff now than we did before.

I realize that in a place like Lithuania this is very controversial. But it’s occasionally worth looking back and saying: we could get rid of the bad and keep some of the good stuff that made people feel like they had more stable lives – so that they would not want to leave the country the first opportunity they get. What was it that made you want to have a family and raise children? Why did it change? And I think a lot of it has to do with a deterioration in women’s rights and support for the family.

Which rights in particular have deteriorated most profoundly?

The one thing I do want to say, because I know that everybody in Eastern Europe always says this: There was a double burden, women worked and they still had responsibility for the home, they had to clean, cook, take care of the kids, so women worked a lot. And that’s not necessarily ideal.

However, there was an expectation that women would make real contributions to society, as well as being mothers, and that they weren’t primarily useful for their sexuality. Look at a place like Ukraine, where you had a really high percentage of women that were very educated in the sciences and mathematics. And what are Ukrainian women doing today? They’re renting their wombs out to Western families to make babies. And that’s on top of the mail order bride stuff.

I reviewed a great book called Soviet Signoras (by Martina Cvajner) about Eastern European women in Italy who worked as carers for elderly people. Often these women, Ukrainian or Romanian, who are working in Italy, are better educated than the people they’re looking after. You have a situation in which the right of women to be intellectual workers, to contribute to society in a non-sexual or non-caregiving way, has evaporated because of the economic situation. And because privatization and new liberalization has reduced the social safety net – you don’t have the same level of job protection, paid maternity leaves, child allowances.

So I just think that there are all sorts of ways in which when we think about women’s rights and opportunities, there were many opportunities that women had before. And I really want to emphasize that I’m not saying this was some perfect world – only that there were policies that we could take. We could think about ways of organizing our society so that we emphasize women’s rights, and also care and respect for the family, whatever form the family takes. ~

https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1619050/post-socialist-transition-was-good-for-some-people-and-really-bad-for-many-others-interview-with-kristen-ghodsee

Oriana:

I went back to Poland twice after the fall of Communism. The availability of consumer goods was immediately noticeable; the lifting of political oppression was a joy to see. An unexpected side effect (or at least I didn’t expect it) was more politeness, a return to greater respect for other people, which showed itself in better manner and softer speech. What was painful to see was the shortage of jobs, especially for professional women such as engineers or language teachers. Some managed to transition to self-employment in their field of expertise, opening their own private offices. Others, alas, went to places like Germany or UK to work as housekeepers and care-takers (including the wife of one of my cousins, who used to work as an engineer). Some elderly women found themselves living in poverty.

The government knew better than to dismantle the social safety network, especially the access to medical care. But it cut back on affordable childcare, for instance. Some couples chose to leave for the west, for countries with more jobs and better social security benefits. That was part of the “catastrophic demographic spiral” that the article talks about. Not enough jobs for young people — a problem not unique to Eastern Europe — is perhaps at the very heart of all the other problems.

*

*

~ This woman, glancing furtively around, says to a random interviewer: A country where the closing of the McDonald's is considered a tragedy but the loss of freedom means nothing, has no future. ~ (from the Facebook page of M. Iossel)

*

UKRAINE AND DRONE WARFARE

~ Ukraine has proven a turning point in the age of drone warfare. The first great drone

superpower, the United States, used its unmanned aerial vehicles in places like Afghanistan where few fighters had the technology to shoot them down. But Ukraine isn’t primarily using drones to hunt people, loitering over targets for days; rather, it's using them to go after Russian armored vehicles and supply columns. This seems like a strategy designed particularly for Russia. Moscow's military theory has always been to establish just enough territory to set up its ferocious artillery units, using heavy armor primarily to defend ranged firepower before storming in once enemy positions have been flattened. Drones have fundamentally shaken that Russian strategy.

Kyiv learnt first-hand the value of this new military technology during the 2014 invasion of eastern Ukraine. When I visited the Donbas frontlines in 2017, there was an incessant buzzing overhead. These were mostly quadcopters, much like the ones you can buy off the shelf, used for low-level surveillance to direct artillery fire. Moscow was able to use the combination of drones and artillery to keep Ukrainian forces hunkering down, unable to push back against Russian-sponsored forces.

Now the tables seem to have been turned. A group of Ukrainian model airplane enthusiasts has been embedded in the Kyiv general staff, using their knowledge of remote-controlled aircraft to deadly effect. According to one recent estimate, Ukraine has over a hundred drones, with the armed forces were using at least 13 different types, including some developed locally. Ukraine has also acquired the Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drone, capable of firing four missiles from its fixed-wing undercarriage. Despite weeks of war, Russia can’t seem to stop them.

Ukrainian forces have been able to challenge Russian tanks to a far greater degree than most military analysts had thought possible. The combination of cheap anti-tank missiles, many of which have come from Britain, and drone reconnaissance have made Russian heavy armor far less effective. Tanks obviously require huge amount of fuel to keep them moving – that means regular resupplying from logistics corps, which in turn means secure travel corridors between Russian depots and the frontline. That hasn't happened.

This is a war of resistance: Ukrainians are able to attack behind what Russia sees as the frontline before melting back into their motherland. All Ukrainian forces need is a cheap, battery-powered quadcopter to survey the battlefield and a well-placed fighter with a shoulder-launched anti-tank weapon and a Russian tank costing anywhere up to £3 million can be effectively destroyed.

And that's before you consider attack drones such as the Bayraktar, costing as little as £750,000. The Turkish drone has the advantage of developed, NATO-grade night-vision – far superior to anything the Russians have – which allows them to pick off the Kremlin's armor in the dead of night. Reports suggest that Kyiv-based command centers are launching over a hundred bombing runs every night.

Russia doesn't seem to have learnt its lesson quickly enough. Azerbaijan used Turkish drones to huge effect during last year's conflict with Russian ally Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh. A combination of Israeli and Ankara-supplied drones gave the country a kind of instant air force that was much more cost-effective than trying to acquire expensive modern aircraft. You don’t need to train or risk pilots if you invest in drones, especially the modern-style kamikaze drones that are used more like cruise missiles to slam into air defense systems and tanks. Baku crushed Armenia’s army using drones, leading some to wonder whether the era of the tank was now over.

Russia, by comparison, appears to lack any attack drones of its own, although the country does plan to start developing them by 2023. What it does have is a 2,000-strong fleet of reconnaissance drones used primarily for target acquisition, including the Orlan series of unmanned aerial vehicles which can cost as little as £80,000.

The problem, though, seems to be that Russia has relied on military tactics that are rooted in the 20th century: legions of tanks and columns of vehicles, pounding cities into submission with artillery and rockets, while not embracing the latest technologies. Russia had ample time to invest in drones the way Azerbaijan and other smaller countries have, but it rested on its laurels. Modern militaries need to incorporate drones across all their units, from small tactical drones to the largest surveillance UAVs.

There is still much that is unknown about Ukraine’s success with drones. How many Bayrtakars remain flying and how many vehicles have been destroyed is still unclear. Washington is supposed to supply new Switchblade kamikaze drones to Ukraine, which could give Kyiv even more firepower in the air.

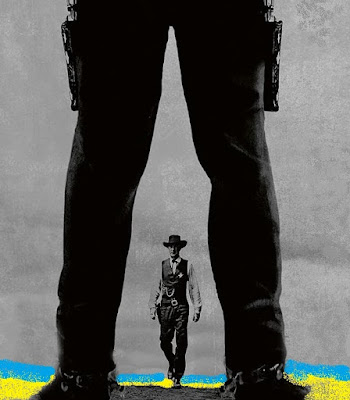

But what's clear now is that the drone is now no longer the preserve of only a few advanced countries; they are the weapon of choice for countries that need an instant air force. It has become the sling in the proverbial David and Goliath fight taking place in Ukraine. Future militaries will need to invest heavily in these weapons if they want to win. ~

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-drone-era-has-arrived?fbclid=IwAR1XtxqmC4mJWO_FPN9vkNXXuI5JodPAC1OlDEokniNA2WPVFspPOYNTwg4

Oriana:

A great image, but I think the story of David and Goliath is more applicable here.

Misha:

Putin effectively has brought a 20th — or even 19th — century war into the 21 century. Tanks, artillery... He was trying to reenact WWII in Ukraine, and he failed spectacularly. He and his inner circle are a bunch of arrogant and sinister, superannuated reenactors who, unfortunately for the humankind, happen to be in possession of a giant country and the world's largest nuclear arsenal. I never liked reenactors, but now I fairly loathe them.

Bernie:

I hope Putin reenacts Hitler's final scene in the bunker too.....right now!!!

Michael:

“Sanctions really began to prove their worth in war-fighting when the Russian tank manufacturer Uralvagonzavod was forced to cease production this week. The factory, located in the town of Nizhni Tagil in the Ural mountain range about a thousand miles from Moscow, has more than 30,000 employees and is said to be the largest maker of tanks in the world.

What caused this modern plant to cease operation? You guessed it: they ran out of computer chips. So did another factory in the same town that makes tractors. They ran out of chips, too.

On Monday, the Ukrainian military claimed that it had destroyed or captured 509 Russian tanks and armored personnel carriers. Without replacements for those fighting machines, the Russian army combat capability is severely limited. Ukrainian forces have been able to take out Russian tanks using the Javelin anti-tank missile system being supplied by the U.S., and a lighter, more easily transportable missile supplied by Great Britain. The Ukrainian military has also used drones carrying “smart” bombs supplied by Turkey to take out armored vehicles.”

https://luciantruscott.substack.com/p/russian-tank-manufacturer-shuts-down?fbclid=IwAR2695M46_K-igYi75F_DPzFzeV3f8A69sqjv_QckiFjKkU129RgupX8uJ0&s=r

*

IS THE PARIS COMMUNE RELEVANT AGAIN?

~ In 2018, as railway workers demonstrated in Paris against proposed government reforms, a banner in the crowd offered a blast from France’s revolutionary past: “We don’t care about May ’68,” read its slogan. “We want 1871.”

It was a message that the protesters meant business. These days, the students’ revolt of 1968, and its injunctions to “Be realistic … demand the impossible”, are remembered with fond nostalgia. But in the annals of French revolutionary upheavals, the memory of the Paris Commune of 1871 and its bloody barricades has a darker, edgier status. “Unlike 1789, the Commune was never truly integrated into the national story,” says Mathilde Larrère, a historian specializing in the radical movements of 19th-century France.

Wild, anarchic and dominated by the Parisian poor, the Commune was loathed by the liberal bourgeoisie as well as by the conservatives and monarchists of the right. Its savage suppression by the French army, and its own acts of brutal violence, created wounds that never healed. “The Commune of 1871 didn’t become part of a consensual collective memory,” says Larrère. In respectable society, it was viewed as beyond the pale.

But 150 years later, the “communards” are making a comeback, dividing Paris all over again. To mark the anniversary, the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, will plant a memorial tree in Montmartre, the crucible of the revolt in March 2021. Place Louise Michel, named after the most famous female communard, will be filled by Parisians carrying lifesize silhouettes of the bakers, shoemakers and washerwomen who seized control of the capital in 1871. Entitled Nous La Commune (We the Commune), the event will kick off a series of exhibitions, lectures and concerts, plays and poetry readings, lasting until May 2021. According to Laurence Patrice, the Paris counselor charged with overseeing the anniversary, it’s time the revolutionaries of 1871 were recognized as radical pioneers: “We are talking about a large group of citizens who came together to take their destiny into their own hands,” she said. “There was a modernity to what the Commune stood for and its aspirations were close to what some people want today.

“The communards battled to have legitimate, accountable political representatives. They wanted to give the vote to women, who played a huge role in the Commune. They defended equal pay and requisitioned empty homes to house the homeless. The Commune offered citizenship to foreigners and free access to the law. There are lots of echoes with today.”

This analysis has not, to put it mildly, met with universal approval. The tributes have enraged conservatives, including Rudolph Granier, a councillor in Montmartre and fellow member of Paris city council. Granier intends to boycott the Place Louise Michel event. “It’s a provocation,” he told the Observer. “I’m fine with commemoration, but not with a celebration. Listen, when the left defends the Commune, it’s the same as when the left defends communism. They say the ideas were beautiful, it’s just that they weren’t carried out properly.

But whether one talks about communism or the Commune it ends up with bloodshed, and if an ideology encompasses killing, then in my opinion it’s not the place of politics to celebrate that ideology.”

In February 2021, during a fiery meeting at Paris’s Hôtel de Ville, Granier accused Hidalgo of exploiting the anniversary to bolster her standing on the left ahead of next year’s presidential election. Parisian conservatives are also objecting to council subsidies for the Association of the Friends of the Commune, an organization which Granier claims “glorifies its most violent events”. As tempers have flared, Le Monde devoted a page to the row, headlined: “The 1871 Commune: an extremely tense anniversary.” The latest edition of the weekly political magazine L’Express asks: “Should the 150th anniversary of the Commune be celebrated?”