Jacob Grimmer (ca. 1526-1590): Winter landscape with a village.

*

SMALL KINDNESSES

I’ve been thinking about the way, when you walk

down a crowded aisle, people pull in their legs

to let you by. Or how strangers still say “bless you”

when someone sneezes, a leftover

from the Bubonic plague. “Don’t die,” we are saying.

And sometimes, when you spill lemons

from your grocery bag, someone else will help you

pick them up. Mostly, we don’t want to harm each other.

We want to be handed our cup of coffee hot,

and to say thank you to the person handing it. To smile

at them and for them to smile back. For the waitress

to call us honey when she sets down the bowl of clam chowder,

and for the driver in the red pick-up truck to let us pass.

We have so little of each other, now. So far

from tribe and fire. Only these brief moments of exchange.

What if they are the true dwelling of the holy, these

fleeting temples we make together when we say, “Here,

have my seat,” “Go ahead — you first,” “I like your hat.”

~ Danusha Lameris

Oriana:

“What if they are the true dwelling of the holy, these / fleeting temples we make together” when we say something kind, however small? They are holy not in any supernatural sense, but simply because they are constantly building civilization, holding society together with kindness and cooperation. And yes, civilization is bigger than we are. We are not just separate individuals, but members of humanity.

Poet’s note:

I wrote [this poem] in early 2017 when the world seemed to be imploding a bit, the country fractured in new (and old) ways. It gave me some solace, and so, without much thought, I posted it online rather than seeking publication. I figured we all could use a lift. Then it spiraled around the globe after appearing in the anthology Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness and Connection. And now, it’s in Bonfire Opera [Danusha Lameris’s second poetry collection]. It’s given me a web of new connections that continue to carry me through these odd and challenging times.

Mary:

Lameris's poem points out what's necessary more than ever in these troubled, anxious times. It seems more and more that people are so close to the tipping edge, and so full of anger, the danger of acting out their rage is only a whisper away. The news is full of incidents, at airports and on flights, in store check out lines, restaurants and on the road, of enraged people physically attacking a nearby target, unable to control their anger, leaving a stewardess with broken bones, threatening the lives of cashiers, getting themselves arrested and banned from flights and other venues. The pandemic is in its third year, people's lives have been disrupted, our political world is divided and threatening insurrection and collapse. People have suffered losses, deaths, and illness, all accompanied by the fear that it will never end, and certainly never end well. People are tired.

The encouragement of small kindnesses may seem too simple an antidote, but it is the kind of thing with great healing power, an effect far greater than the small effort it takes. The rewards are substantial, and felt by both parties. The giver and receiver are cheered and heartened. Consciously trying to show kindness to others in daily interactions, the deliberate choice to be kind, can even lead to a habit of kindness, profoundly reshaping your attitude and relationship with the world.

We are so caught up in acrimony it has unfortunately become a habit, and a bad one. Drawing lines in the sand and always being prepared for conflict, generates conflict. Compromise is felt as an evil capitulation. Cooperation is seen as co-optation. Divisions are reinforced by admitting no common ground. Opponents are demonized, reified into “the Enemy.” This is going on in the US big time right now, a pattern and attitude that is self defeating and de-civilizing.

Beginning with kindness is re-humanizing, salutary and, yes, civilizing. We need it now.

*

MIKHAIL IOSSEL: HERE AND THERE

In the seven years that I lived at my last address in the old Soviet Union — in an airy, comfortably cluttered one-room apartment on the sixth floor of a sturdy, massive building (put up by the German POW's in the late '40s) in the southwestern part of Leningrad, on a quiet, tree-lined street (named after a major Red Army Commander during the Russian Civil War, allegedly killed on Stalin's implicit order in the course of a deliberately botched prophylactic ulcer surgery) off the bustling Moskovsky Prospekt, a ten-minute's unhurried walk away from the Park of Victory metro station — not once, whenever (infrequently, irregularly, but still) I would accidentally run into her on the floor landing or share an elevator ride with her, did I detect the slightest sign of unfriendliness or, you know, psychological unease on the part of my next-door neighbor: a diminutive, small-faced, sharp-nosed, bird-featured woman of indeterminate advanced age bearing an endearing resemblance to the legendary comedic actress Rina Zelyonaya as Mrs. Hudson in the terrific Soviet TV-serial "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson" (which, curiously but apropos of nothing, started being aired in 1979, the year I moved into the apartment in question, and ended in 1986, shortly after I left the Soviet Union; it featured excellent performances by Vassily Livanov and Vitaly Solomin), or else (still speaking of Rina Zelyonaya — too long, I agree!) in the role of the ageless Tortilla the Tortoise in the even more popular TV-musical "The Adventures of Buratino." Buratino, yes…

Yes, indeed. Moreover, in those seven long years, never once did she fail to greet me with a sweet little lopsided tight-lipped smile (like many Leningraders, she was severely dentally challenged); and not on a single occasion did she put up as much as a hint of an objection against a constant stream, at any time of day and night, of overwhelmingly young and, not to mince words, kind of party-minded visitors to my place: men, women, foreign students of Russian, you name it... with all the attendant chaotic drinking, boisterous laughter, politically dubious and less than tasteful exclamations, and other manifestations of gratuitously unregulated merry-making. Not one tiny complaint from her, ever. Angelic patience. Total tacit understanding. In short, a perfect next-door neighbor.

But on that wintry early morning in 1986, in the inchoate boreal dawn when I, closing and locking the door of my apartment (by then, completely, dolorously empty: a stranger to me) for the last time in my life, had dragged across the landing's concrete and to the elevator shaft my single large beige fake-leather suitcase with the meager residue of my past and all the insane uncertainty of my future in it, she — that veritable paragon of neighborly forbearance and magnanimity (whose name, incidentally, I never knew... And did she know mine? Oh, I'm pretty sure she did) — unlatched and unbolted her own door from inside with furious cast-iron clanging and fairly flung it open, fully liberated at last, to present me with her glowering visage in a shapeless billowing ghastly, ghostly housecoat, silhouetted grotesquely from within by the dusky yellow glow of an unshaded lightbulb dangling from the unseen ceiling of her narrow hallway.

"Aha! Yes! Finally!" she hissed — spat out in a hissing whisper — with an almost cartoonish venomousness. "The f**king bastard is leaving us, isn't he! Good, good! Good riddance! Now we'll have a cleaner Russian air to breathe, when he, with his f**king den of iniquity, his home syna... gogue for human trash and our class enemies no longer is here. Oh, I've waited for this moment for so f**king long, believe you me! Just to tell you this! I hope you... you... you f**king die like a dog there... there, you dirty f**king…" Well, OK. One gets the idea. I am paraphrasing her outburst a bit, of course. Softening it up a little. It's all good.

My parents were waiting for me downstairs in one car, my friends in the other. We were going to the airport, that frozen farewell place. Everyone was numb with the realization of the day's irreversible finality. Filled with uncertain hope and utmost trepidation, stuporous yet shivering with excitement, I had no time or emotional capacity to spare on the clearly troubled woman's bizarre transformation. "Don't choke on your bile," I told her — or something feebly timid like that — as I pushed the chipped, grimy red plastic button on the elevator door. She spat in my general direction (well short, to be sure, but that was not the point), then slammed her door shut, thus exiting my life forever, ensconced in the new *there-ness* of the floor-landing’s *here* which we had shared, at least nominally, for a good one-fourth of my whole life.

Oh well.

She must have been dead for years, if not decades now — that former next-door neighbor of mine. I don't think of her often — or at all, to be more precise. But I do think about death from time to time, and so today I remembered her. Her *here*, my *there* — and the other way around. Ex post facto, her ardent parting wish of that long-ago wintry morning — that I would die *there* — will be fulfilled, of course, in due course of events: wherever I am going to die, it most certainly will be *there*. No question about it. *There*, you know. There. No matter where I'll end up dying — even if, impossibly enough, it will happen in the onetime *here* of that sixth-floor landing in the massive apartment building in the southwestern part of former Leningrad where we used to be next-door neighbors, etc. — it still will be *there*.

Here, there... Every *here* I ever had would eventually turn into a *there*, and that’s just the way it is. I could say that I feel I may have run out of *here's* by this point in my life, but that probably would be overstating and overdramatizing it. All our *here's* eventually, with the passage of time, turn into one endless echoing *there*: a solitary space, non-shareable by default. ~

M. Iossel’s Leningrad apartment, 1985

Oriana:

I love that last paragraph, and especially the last sentence: “All our *here's* eventually, with the passage of time, turn into one endless echoing *there*: a solitary space, non-shareable by default.”

The story itself, is, alas, essentially the opposite of “Small Kindnesses.” The neighbor who at first appears kind and tolerant explodes into anti-Semitic hate speech. She tears down the bonds of humanity that Lameris builds in her deceptively modest poem. How utterly sad that on his last day in the Soviet Union Mikhail was subjected to that outpouring of hatred. And, mind you, he says that his translation of it tones it down.

Now, we could try to psychologize and speculate that this woman had an abused childhood, and that she herself heard how she is no good and will die like a dog and so on. And that obvious scapegoating and displacement is going on: the motherland is idealized while the Jews are demonized. Still, ultimately we are aghast and have the feeling that nothing excuses this vile behavior.

Mary:

Iossel's story about the “here” and “there’s" of our lives is interesting in many ways, and is also seemingly simple and actually quite complex.

“Here” is where we are now, our present, constantly turning into “there” all the places, times and actions of our past. We may share our “here” with others, but never, ultimately, our “there’s.” Because every "there" is a remembered place and time, and the particularity of that cannot be truly communicated and shared. The "there" of that time and that apartment exists for Iossel, his guests, and the anti-Semitic neighbor, but each one is different, always different. For the friends he socialized with there and then the differences may be less pronounced, more nuanced. For the hate-filled neighbor those differences are extreme. Her “there” is radically different from Iossel’s, and it is the shock of that radical difference he presents in the story of when it was revealed to him.

It is very unnerving to have that difference suddenly open up like a chasm at your feet. What is revealed about reality goes against our idea that reality is solid, external and knowable, similar and agreed upon by everyone. Then suddenly the sweet old lady becomes a hate-spitting viper, putting all your assumptions about her, and you, and the world you inhabit, into question.

You are shocked, and may ask your self "how could I be so blind," or "how could I be so wrong, so far off?" The earth shifts. It's frightening.

Oriana:

Fortunately Mikhail is not stewing in resentment over this one particular instance of anti-Semitism that he experienced in the Soviet Union — though the timing of it makes it unforgettable. Note that he didn’t use the post to pour out hate speech against this Hitlerian woman. He’s moved on to a literary and teaching career that makes him a builder, not a hater. This is his latest post, in commemoration of someone he regards as a great literary critic, Terry Teachout, who has just died:

*

LESS ANXIOUS PARENTING: DO LESS

~ In the nineteen-thirties in Budapest, a young mother struggled. “I was amazed at how difficult it was to be a parent. I was angry,” Magda Gerber wrote later. “I thought I was the only one who didn’t know what to do with babies and somehow in my education someone had forgotten to tell me.” Then, one day, she watched in astonishment as a pediatrician treated her four-year-old daughter. The doctor, a Viennese Jew named Emmi Pikler, did something unheard of: she listened to her patient. Gerber was dazzled by Pikler’s insistence that her daughter could speak for herself—that even the youngest children could be enlisted in stunning feats of coöperation. “It made me feel that this was the answer to all my questions and doubts,” Gerber wrote. She devoted the rest of her life to learning from Pikler and disseminating her ideas.

Pikler argued that babies, like seeds growing into plants, did not need any teaching to develop as nature intended; they would learn to walk, speak, sleep, self-soothe, and interact perfectly, if only we would get out of their way. The problem, she wrote in “Peaceful Babies—Contented Mothers,” is that “the child is seen as a toy or as a ‘doll,’ rather than a human being.” Babies are shushed when they try to communicate, clucked at like morons, tickled when they are sad, passed around like objects, and crammed into high chairs in positions their bodies aren’t ready to form. After becoming accustomed to this relentless, invasive attention, a child starts believing that she requires it. “She will, in time, become increasingly whiney and cling to adults,” Pikler cautioned. The result is a kid as desperate for attention as her parents are desperate for peace.

In 1946, the city of Budapest enlisted Pikler to set up an orphanage for children who’d lost their families to the Second World War. Pikler soon fired the nurses, who seemed unable to relinquish their authoritarian focus on efficiency, and replaced them with young women from local villages, whom she trained to treat infants with “ceremonious slowness.” Over time, Pikler codified a philosophy, built around showing babies the same respect that adults reflexively grant one another. Magda Gerber emigrated in 1957, settling in California, where she spread the message in the sunshine, with a program soberly named Resources for Infant Educarers, or RIE.

One breezy recent morning, Janet Lansbury, a sixty-two-year-old protégée of Gerber’s, was leading a class in a back yard in Los Angeles. Seven women and a few of their husbands were sitting by a sandbox, trying not to cave in to their toddlers’ whined demands. “Out!” a pigtailed two-year-old named Jasmine moaned. “Daddy, out!” She was on the second rung of a climbing structure she’d mounted moments earlier.

Her mother and father looked on in concern. “You can tell I’m a hoverer,” the mom said, to general sympathy. Many of the adults were struggling against the urge to parent like helicopters (circling their children, incessantly surveilling) or, worse, bulldozers (plowing aside every obstacle before their kids can encounter a moment’s difficulty). Lansbury and Gerber urge people instead to be a “stable base” that children leave and return to—an idea that many modern parents find intensely difficult to apply.

“My gut is to go to her,” Jasmine’s father said apologetically. “It’s kind of a weird spot.”

“Usually, if they can get there, they can get down from there,” Lansbury told him. She knelt next to Jasmine and said, “You feel like you want your daddy to help? He’s right there. He’s listening to you.” (This is a key element of the RIE approach: you acknowledge everything your child wants, even if you are doing none of it.)

“I’m curious to see what she does,” Jasmine’s father said, with what sounded more like anxiety.

Jasmine said, “Owie.” Then she clambered down.

Her mother looked relieved. “Jazzy, can I get a kiss?”

“Uh, nope,” Jasmine replied, and waddled off.

Lansbury is a Californian’s Californian. She has blond hair and blue eyes and was a model and actress in her youth. She practices Transcendental Meditation and jogs on the beach. She wears a little necklace with a starfish on it. But she isn’t wishy-washy with children. Strict boundaries, enforced with confidence, are what enables them to relax, she counsels. It is our ambivalence about rules that compels children to “explore” them. Kids are fascinated by anything that unsettles their overlords, so they will keep acting out as long as we keep getting upset. “They’re asking a question with this behavior,” Lansbury says. “ ‘Am I allowed to do this? What about when you’re really tired?’ ”

In the back yard, a mom told Lansbury that her two-year-old throws tantrums every time he’s told no, bonking his head against the floor. Lansbury looked at the tiny culprit. “Sometimes you go down on the ground because you don’t like it when someone says no?” she asked. Turning to his mother, she suggested putting a blanket under his head, so he wouldn’t hurt himself. “He’s got a right to object,” she continued. “It’s so healthy for them!”

Lansbury has ascended as a parenting guru by delivering slightly startling advice in a reassuring tone. “Try pretending that everything you say to your child, every decision you make, is absolutely perfect, for one day,” she suggests in an episode of her podcast, “Unruffled,” which has nearly a million listeners a month. “Trust your child” is a frequent refrain. The title of her most recent book is “No Bad Kids.” Emmi Pikler put things less soothingly: “If an otherwise healthy infant is ‘bored,’ ‘bad-tempered,’ or ‘high-strung’ (as it is called) these tendencies always are the result of the behavior of the environment—or, to be more precise, of mistakes in upbringing.” The good news is that there are no bad kids. The bad news is that there are plenty of bad parents.

*

Parents with the inclination—and the time—to contemplate their approach to child rearing have some stark decisions to make. For a generation, the reigning guru has been the pediatrician William Sears, an advocate of “attachment parenting.” Mothers who follow his advice will find themselves sleeping with their babies in their beds, wearing them in a sling or a carrier as much as possible, and breast-feeding whenever they cry. Such a mother, Sears writes, “will feel complete only when she is with her baby.” She has become a kangaroo. Or, perhaps, a caricature of a liberal: no need is too trivial to necessitate her bosomy intervention.

This stands in contrast to the top-down, conservative style of parenting that tells children to cry it out and pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Achievement is rewarded (“If you’re good, you can have ice cream”), hierarchy is unquestioned (“Because I said so”), and personal responsibility is enforced with the threat of consequences (“I’ll give you something to cry about”). RIE might be compared to a kind of weirdly loving libertarianism: children are expected to solve their own problems; parents are expected to affirm their kids’ feelings, even the ugly ones. “As completely counterintuitive as this is for most of us, it works,” Lansbury writes. “How can your child continue to fight when you won’t stop agreeing with her?”

Lansbury’s style is inclusive; her podcast’s tagline is “We can do this.” But, as much as we crave expert guidance, many of us still resent any intimation that what we’re doing with our kids is wrong. “Janet is the Martha Stewart of the millennials—she’s ubiquitous, I can’t get away from her,” Tori Barnes, a thirty-four-year-old mother of three in a Denver suburb, told me. “When I was in middle school, my mom loved Martha—watched her on the Home Garden Network all the time, read all her books. Then one day my mom slammed her book shut and said, ‘That’s it. Martha Stewart just told me to go pick dandelions and make dandelion wine. I don’t have time for this shit.’ ”

Barnes had her dandelion-wine moment when she heard Lansbury describe diaper changes as an opportunity to connect with her baby. RIE adherents believe that parents should deliver care with undivided attention, so that diapering, nursing, and bathing become times of relationship-building. Lansbury suggests performing diaper changes with exquisite slowness, describing every action, and seeking the child’s participation by asking questions like “Will you lift your legs now, so I can wipe you?”

“It’s, like, There’s poop,” Barnes said. “Get in and get out! This is not the time for a loving, connecting opportunity—do this disgusting task and move on.”

Unlike Spock, RIE tells parents that they know less than they think they do. Most people share some basic assumptions about child rearing. Babies eat in high chairs. “Good job!” is a nice thing to say when your kid achieves a little something. If your infant starts to sob, redirect his attention. (Heidi Murkoff’s “What to Expect the First Year,” which has sold more than ten million copies, assures parents, “With distraction, everyone wins.”)

None of this flies in RIE. Reflexive praise is discouraged, because it impedes “inner-directed” decision-making. Swaddling is out, because freedom of movement encourages gross-motor development. Pacifiers are proscribed. “Magda would always say, ‘Babies have a right to cry,’ ” Lansbury told me. High chairs are frowned upon: instead, feed your kid at a little table as he sits on the floor or a stool. That way, it becomes obvious when he’s hungry (he crawls over to the table) and when he’s full (he crawls away, or starts playing with his food). There are YouTube videos of toddlers at RIE class, waiting around tables for snack with the aplomb of tiny diplomats.

*

These days, Lansbury estimates, eighty-five per cent of the questions she gets are from parents whose children are acting out in response to the arrival of a new baby. Lansbury urges parents to empathize with the older children’s feelings, while resisting the fear that they’ve suddenly become possessed. “It’s devastating for them—their whole world has just collapsed,” she said.

*

I asked Lansbury if she had any regrets about her own parenting. After a very long pause, she said no. “It’s not like I think I’m perfect, but I’m proud of how I am as a parent, and it’s a good feeling to have,” she said. “Magda gave me something to feel really confident about. My whole goal is, I want people to believe in themselves that much.”

So does it work? It’s difficult to prove parenting choices right or wrong. Spock told people to put babies down on their bellies, so that they wouldn’t choke on their spit-up. Pikler believed that they should always be on their backs, where they’d have more control. It is estimated that some fifty thousand babies in the U.S., Europe, and Australasia could have been saved from SIDS if Pikler’s guidance had prevailed. But, for the most part, to know what “works” with kids, we’d first have to agree on what that means. Is success a child who is obedient? Or highly motivated? Or just happy?

Whatever your goals, and whatever your style—respectful or authoritarian, bulldozer or kangaroo—it’s not clear that any of it ultimately matters. “From an empirical perspective, parenting is a mug’s game,” Alison Gopnik writes. “It is very difficult to find any reliable empirical relation between the small variations in what parents do—the variations that are the focus of parenting—and the resulting adult traits of their children.” Tiger moms don’t have an edge on producing future world leaders; Francophiles bringing up bébés are no more likely than the rest of us to have their kids win the Légion d’Honneur.

Lansbury, though, does not promise that her approach will lead to the best possible kid; what she’s selling is the best possible relationship. If you just believe in yourself, and believe in the method, then your child will believe in you, too, and everyone can relax. (A mantra of Gerber’s was “Do less, enjoy more.”) This has an element of catechism—but so do Sears, and Spock, and “What to Expect.” All parenting is a faith-based initiative.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/01/17/janet-lansburys-gospel-of-less-anxious-parenting?

Oriana:

I remember that my friend Una, a mother of five, told me, "No matter what you do, they all turn out different, and different from what you expected." But any advice that will make parents less anxious seems to be moving in the right direction.

*

THE AMAZING HELEN DORTCH LONGSTREET

~ By the time Helen Dortch married Gen. James Longstreet in September 1897, she was already quite accomplished. A newspaper account described her as “one of the most conspicuous among the progressive women of the new south.” She began working as a newspaper reporter and editor at fifteen. In 1894 she became the first woman to hold office in Georgia when she was appointed assistant state librarian. The state legislature had to change the law before she could assume office.

The papers made much of the difference in their ages – Longstreet was 76 and she was 34 – but theirs was by all accounts a happy marriage for the seven years they shared together. She was his constant companion until the moment of his death, and she fiercely defended his legacy until her own death in 1962. She labored to achieve equal rights for women and for African Americans, even mounting a write in campaign for Governor of Georgia where she promised to “unhood the ruffians” of the Ku Klux Klan. “I’ll make this state a place where even the humblest Negro can go to sleep at night and be assured of waking up in the morning, unless the Almighty calls.”

The “frail but vivacious” widow Longstreet was 80 years old when she went to work as a riveter building B-29s at the Bell Aircraft plant in Atlanta. The year was 1943, and she was determined to do her part to bring World War II to an end. “This is the most horrible war of them all. It makes Gen. Sherman look like a piker. I want to get it over with. I want to build bombers to bomb Hitler.” In 1947, Helen Dortch Longstreet became the first woman to have her portrait placed in the Georgia State Capitol. She died in 1962 at the age of 99. ~

posted on Facebook, 1-12-22

and here Helen, the beautiful bride

*

THE MYSTERY OF ULTRA-LOW VELOCITY ZONES IN THE EARTH’S INTERIOR

~ Deep under Africa and the central Pacific lie clusters of geological mysteries—nearly 1,800 miles (2,890 kilometers) below, down at the bottom of the mantle. Scientists typically use seismic waves generated by earthquakes to peer into Earth’s interior. But such waves aren’t especially enlightening in these parts, where seismic waves slow down as if they’re caught in jelly.

Those regions, potentially hundreds of kilometers wide, are called ultra-low velocity zones (ULVZs), and so far, their origins have remained a mystery. But now, a team of geologists has an idea. Simulating the formation of these mysterious zones, the geologists have evidence that the features are actually patches of ancient material, billions of years old, that sank to the bottom of the mantle over the years.

For years, scientists hadn’t been sure what, exactly, ULVZs were, or what created them. These areas occur at the base of the mantle, at the edge of Earth’s outer core. Scientists knew that these zones were much denser than the surrounding mantle, but that only raised more questions than answers.

“We can see these features in many different locations of the lower mantle, but we still don’t know the answers to many basic questions about them,” says Thorne. According to him, we don’t know what they’re made of, how big they are, or even where they’re all located.

Thorne, Pachhai, and their colleagues focused on one area of ULVZs: located deep under the Coral Sea, northeast of Australia, home to the Great Barrier Reef. It’s an ideal location, since earthquakes are a frequent occurrence there. Those earthquakes give plenty of seismic waves that scientists can use to visualize the inside of the Earth.

But the seismic wave signatures they observed, from thousands of miles below even the deepest depths of the ocean, offered only blurry and uncertain pictures of ULVZs, so the scientists turned to simulations. They created theoretical models of Earth’s interior that include ULVZs, and they simulated seismic waves trembling through them to determine what those waves would look like to an observer on their virtual Earth. Running simulations under scores of conditions, they compared the results to what they’d observed under the Coral Sea to see how well each model matched.

The best match to their work corresponded to a scenario in which ULVZs don’t have single layers, but rather multiple ones. Pachhai says that, to their knowledge, this is the first study that’s shown evidence of this.

Their models also show that the layers aren’t uniform. There’s a lot of unevenness in their composition and in their structure. Those layers, the researchers think, must have formed early in Earth’s history.

“They are still not well mixed after 4.5 billion years of mantle convection,” says Pachhai.

The researchers think this could be related to a cataclysm when Earth was quite young. Four-and-a-half billion years ago, a planetoid that some call Theia collided with Earth—the same impact that might have kicked up a patch of debris that later coalesced into the moon.

The enormous energy of the impact would have taken a giant chunk out of Earth and left behind an ocean of mixed molten rock, stuffed and spiced with all sorts of gases and crystals. As this ocean cooled and sorted itself out, becoming today’s mantle and crust, denser material might have dropped to the bottom without mixing.

That dense material, then, would form the basis of what are today ULVZs.

Of course, this is only one theory, and limited to one stop of the globe. By gleaning more details from ULVZs, the researchers say they could learn a lot more about what that ancient magma ocean was like.

“With all of these various unknown questions remaining, there is still a lot of room for basic discovery, and this is what keeps sucking me back in to study them,” says Thorne, “the potential to add to the fundamental knowledge about what our Earth is made of and how it works.” ~

https://www.popsci.com/science/earths-mantle-regions-explained/?fbclid=IwAR3EIuLyvqY2kNa0Ds665DQwaX0YcSTuTkeGG_kS4lqQedRqzeVtX5v5B3I

*

EARTH’S OLDEST OCEANIC CRUST: THE BOTTOM OF AN ANCIENT OCEAN, TETHYS

~ At the bottom of the eastern Mediterranean Sea lies the world’s oldest oceanic crust, according to a new study.

Dr. Roi Granot of the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel has discovered that an oceanic crust that has been hiding in the sea’s sediment-ridden waters may have been part of the ancient Tethys Ocean, according to a release from the university.

Granot believes the 60,000-square-mile crust may have also been formed around the time Earth’s landmasses formed the supercontinent Pangea, reports Business Insider.

With the use of magnetic data, Granot and his research team analyzed the crust’s structure in the basin and discovered that the rocks are characterized by magnetic stripes, the hallmark of oceanic crust that formed at a mid-ocean ridge, according to the release. As magma at a mid-ocean ridge axis cools off, magnetic minerals in the newly forming rocks align in the direction of Earth’s magnetic field.

Over time, changes in the field’s orientation are recorded in the ocean floors, creating a unique “barcode” that provides a timestamp of when the crust formed.

“I use the shape, or skewness, of these magnetic anomalies to constrain the timing of crustal formation and find that it formed about 340 million years ago,” Granot wrote in the study.

“I suggest that this oceanic crust formed either along the Tethys spreading system, implying the Neotethys Ocean came into being earlier than previously thought, or during the amalgamation of the Pangaea Supercontinent.”

Oceanic crust has a high density, which causes it to be recycled back into the Earth’s mantle relatively fast at subduction zones, according to the release. This means most of the crust is less than 200 million years old – significantly younger than the mass found by Granot.

“We don’t have intact oceanic crust that old … It would mean that this ocean was formed while Pangaea, the last supercontinent, was in the making,” Granot told Business Insider.

"But we are not sure that it is really part of the Tethys Ocean,” he added. “It could be that this oceanic crust is not related at all.”

The Tethys Ocean was a former tropical body of salt water that existed during much of the Mesozoic Era.

It separated the supercontinent of Laurasia, which is now North America and the portion of Eurasia that lies north of the Alpine-Himalayan mountain ranges, and the Gondwana, which is present-day South America, Africa, peninsular India, Australia, Antarctica and those Eurasian regions south of the mountain chain. ~

https://www.geologyin.com/2016/08/geologist-unearths-340-million-year-old.html?fbclid=IwAR2vk6f-2uu5BllcXvGhEiL6v2DCTxcbzgzwKpGjbjyUV6HcQco2Zh8L6GM

Oriana:

Think of it! The Himalayas were once underwater, in an ancient ocean.

In Greek mythology, Tethys was the daughter of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth), and mother of numerous water-related offspring.

Mary:

It is fascinating to hear about both the ultra low velocity areas in the earth and the discovery of a remaining fragment of ocean crust from before the continents formed. These are the kinds of questions and discoveries that lead us seeking deeper into time, building toward understanding earth’s history, which is of course, in time, our history. To think on this timescale is to gain perspective, to have a clearer and more detailed grasp of a time before there were either any "here's " or “there’s" — but it was crucial for the development of the here and now.

mountains on ocean floor

*

THE DARK SECRET OF ANTS THAT DO NO SEEM TO AGE

~ Deep in the forests of Germany, nestled neatly into the hollowed-out shells of acorns, live a smattering of ants who have stumbled upon a fountain of youth. They are born workers, but do not do much work. Their days are spent lollygagging about the nest, where their siblings shower them with gifts of food. They seem to elude the ravages of old age, retaining a durably adolescent physique, their outer shells soft and their hue distinctively tawny. Their scent, too, seems to shift, wafting out an alluring perfume that endears them to others. While their sisters, who have nearly identical genomes, perish within months of being born, these death-defying insects live on for years and years and years.

They are Temnothorax ants, and their elixirs of life are the tapeworms that teem within their bellies—parasites that paradoxically prolong the life of their host at a strange and terrible cost.

A few such life-lengthening partnerships have been documented between microbes and insects such as wasps, beetles, and mosquitoes. But what these ants experience is more extreme than anything that’s come before, says Susanne Foitzik, an entomologist at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, in Germany, who studies the ants and their tapeworms. Infected Temnothorax ants live at least three times longer than their siblings, and perhaps much more, she and her colleagues report in a study published in Royal Society Open Science. No one is yet sure when the insects’ longevity tops out, but the answer is probably in excess of a decade, approaching or even matching that of ant queens, who can survive up to 20 years.

“Some other parasites do extend life spans,” Shelley Adamo, a parasite expert at Dalhousie University, in Nova Scotia, who was not involved in the study, told me. “But not like this.”

Under typical circumstances, Temnothorax ants live as most other ants do. They reside in communities ruled by a single fertile queen attended by a legion of workers whose professional lives take a predictable trajectory. They first tend the queen’s eggs as nurses, then graduate into foraging roles that take them outside the nest. Apart from the whole freaky parasite thing, “they are pretty boring,” Foitzik told me.

Normalcy goes out the door, however, when Temnothorax larvae ingest tapeworm-egg-infested bird feces trucked in by foragers. The parasites hatch and set up permanent residence in the young ants’ abdomens, where they can access a steady stream of nutrients. In return, they offer their host an unconventional renter’s fee: an extra-long life span that Foitzik and her colleagues managed to record in real time.

The researchers spent three years monitoring dozens of Temnothorax colonies in the lab, comparing the fates of workers who’d fallen prey to the parasites and those who remained infection-free. By the end of their experiment, almost every single one of the hundreds of worm-free workers had, unsurprisingly, died. But more than half the parasitized workers were still kicking—about the same proportion as the colonies’ ultra-long-lived queens. “That was amazing to see,” Biplabendu Das, an ant biologist and parasite expert at the University of Central Florida, who wasn’t involved in the study, told me. And despite their old age, the ants’ bodies still bore the hallmarks of youth. They were difficult to distinguish from uninfected nurses, who are usually the most juvenile members of the colony’s working class.

The tapeworm-laden ants didn’t just outlive their siblings, the team found. They were coddled while they did it. They spent their days lounging in their nest, performing none of the tasks expected of workers. They were groomed, fed, and carried by their siblings, often receiving more attention than even the queen—unheard of in a typical ant society—and gave absolutely nothing in return.

The deal the ants have cut with their parasites seems, at first pass, pretty cushy. Foitzik told me that her team couldn’t find any overt downsides to life as an infected ant, a finding that appears to shatter the standard paradigm of parasitism. Even the colonies as a whole remained largely intact. Workers continued to work; queens continued to lay eggs. The threads that held each Temnothorax society together seemed unmussed.

Only when the researchers took a closer look did that tapestry begin to unravel. The uninfected workers in parasitized colonies, they realized, were laboring harder. Strained by the additional burden of their wormed-up nestmates, they seemed to be shunting care away from their queen. They were dying sooner than they might have if the colonies had remained parasite-free. At the community level, the ants were exhibiting signs of stress, and the parasite’s true tax was, at last, starting to show.

“The cost is in the division of labor,” Das said. The worms were tapping into not just “individual [ant] physiology, but also social interactions,” Farrah Bashey-Visser, a parasitologist at Indiana University who wasn’t involved in the study, told me.

Scientists think of social insects not as single bugs, but as interlaced parts of a giant “superorganism,” Manuela Ramalho, an ant biologist at Cornell University, who wasn’t involved in the study, told me. When one individual acts, others around it react; in a colony, no ant can truly act alone. Parasites of these communities automatically extend their reach to multiple animals at once, a rippling mind-control effect that spreads and amplifies the consequences of infection. Although the tapeworms had infected only a fraction of the Temnothorax workers, they were puppeteering the entire society.

That altered existence might play directly into the parasite’s hands. Tapeworms of these species can’t mature into adults and produce eggs until their ant host is consumed by a bird—a fate that insects in full possession of their faculties try to avoid. But ants who spend all their time lazing around the house make for easy prey; hosts who are pampered and long-lived have a high chance of surviving until they’re eaten. The worm’s most ingenious move might play out in some ants’ final moments, as they trade their natural fear of intruders for a dollop of ennui. When Foitzik and her students crack open infected Temnothorax colonies, the parasitized workers do little more than stare expectantly skyward. “Everyone else is just taking the larvae and running,” Foitzik said. “The infected workers are just like, Oh, what’s going on?”

Down to the molecular level, the parasite is pulling the strings. Sara Beros, Foitzik’s former doctoral student and the paper’s first author, told me she has split open Temnothorax abdomens and counted up to 70 tapeworms inside. From there, the worms can unleash a slurry of proteins and chemicals that futz with the ant’s core physiology, likely impacting their host’s hormones, immune system, and genes. What they achieve appears to be a rough pantomime of how ant queens attain their mind-boggling life span, a feat humans still don’t understand. (The tapeworms’ grasp of ant aging is far more advanced than ours.) The parasites are effectively flash-freezing their host into a preserved state—one that will up their own chances of survival, and help guarantee that their species lives on.

The worms’ MO is subtle and ingenious. They are agents not of disaster, but of an insidious social sickness that sets reality only slightly, barely perceptibly, askew. Infected workers get a taste of invincibility and status, swaddling themselves in youth and the benefits it brings. They also form resource sinks that sap the energy of those around them. They become echoes of the microorganisms they harbor. They are, in the end, parasites themselves. ~

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/05/ant-tapeworm/618919/?utm_campaign=the-atlantic&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR01qIzNhJaYBxU0lul0x1bHt8eMO8vnRAKLsaio6KHbTQlei6tRvab8QtE

*

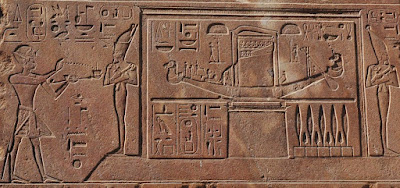

THE ARK OF COVENANT WAS MODELED AFTER THE EGYPTIAN SACRED BARK

The best non-Israelite parallel to the Ark of the Covenant comes not from Mesopotamia or Arabia, but from Egypt. The sacred bark was a ritual object deeply embedded in the Egyptian ritual and mythological landscapes. It was carried aloft in processions or pulled in a sledge or a wagon; its purpose was to transport a god or a mummy and sometimes to dispense oracles. The Israelite conception of the Ark probably originated under Egyptian influence in the Late Bronze Age.

The Ark of the Covenant holds a prominent place in the biblical narratives surrounding the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt. Its central role as a vehicle for communicating with Yahweh and as a portable priestly reliquary distinguishes it from all other aspects of the early cult. In varying detail, biblical texts ascribe to the Ark a number of functions and powers, which have led scholars to see the Bible’s portrayal of the Ark as the result of historical development and theological reinterpretation.

Biblical texts describe the Ark of the Covenant as a sacred object containing five major features.The first is a wooden box (Heb. ʾaro ̄n), roughly4 ft. 2.5 2.5, and overlaid with gold. The second is a lid (Heb. kappo ̄reth), made entirely of gold, not plated like the box, which contains a molding running along its top edge. Its third component is a pair of gold kerubıˆm, i.e., “sphinxes,”4 that rest on top of the lid and face each other with their wings touching. Note that the lid was understood as God’s “throne,” whereas the box was viewed as his “footstool.”

The Ark’s fourth feature was its wooden poles, which were inserted through four gold rings and never removed. Only the priestly tribe of Levi was permitted to carry the Ark, and even then, only after they had veiled it (Exod 40:3, 40:21).6 No one of non-priestly descent was allowed to touch it. The Ark’s fifth feature was its contents: the tablets of the law, a jar of manna, and possibly the rod of Aaron.

In addition to serving as a reliquary, texts attribute two other functions to the Ark. Most prominently, it served as the symbolic presence of Yahweh. In times of war, Yahweh led as the Lord of Hosts, seated upon the kerubıˆm, surrounded by standard bearers preceding him. Each standard was topped with a banner representing an Israelite tribe or family line.

As the symbolic presence of Yahweh, the Ark was connected to miracles and oracles. Thus, when the priests carried the Ark into the Jordan River the waters parted (Josh 3:8–17), and Moses, Phinehas, Samuel, Saul, and David each received divine direction from the Ark.

Before the temple was built, the Ark stayed at a number of sanctuaries including Gilgal, Bokhim, Bethel, and Shiloh. During the visits Yahweh would accept sacrifices and bless his sanctuaries. Finally, the Ark acquired a ritual function. On Yom Kippur the high priest would sprinkle bull’s blood onto and in front of the Ark’s lid (Lev 16:14).

As Michael Homan has shown, the strongest parallels for the tabernacle in which the Ark was placed are ancient Egyptian military and funerary tents including the tent-like coverings for funerary barks. This suggests even greater propriety in looking to Egypt for an analogue.

With this in mind, I should like to propose that the Egyptian sacred bark offers a more compelling and complete parallel for the Ark. Of course, the bark was not merely a boat, but a sacred ritual object deeply embedded in the ritual and mythological landscapes of the Egyptians. Though they resembled boats, they rarely, if ever, were set in water. Even when they needed to cross the Nile, they were loaded onto barges. Usually, they were carried by hand or in some cases dragged on a sledge or placed on a wagon. The bark’s most basic function was to transport gods and mummies. When transporting gods, the bark was fitted with a gold-plated naos containing a divine image seated on a block throne, which was veiled with a thin canopy of wood or cloth.

Many barks were decorated with protective kerubıˆm, such as the naos of the bark of Amun found on Seti I’s mortuary temple in Qurna and the bark of Horus in the temple at Edfu.

Like the Ark of the Covenant, sacred barks were carried on poles by priests, the so-called pure ones (Egyptian: wʿbw), who had performed purification rituals in order to hoist the bark. Though most Egyptian rituals were never witnessed by the public, the procession of the sacred bark was an important exception. It was the focus of an intense series of festivals throughout the year, as many as five to ten per month, which involved loud music and dancing. During the celebrations, priests carried the bark from one shrine to another, and made stops along the way, during which they dramatized mythological scenes. The route and length of the processions varied depending on the gods they carried and their mythologies.

The bark also gave oracles. While resting at one of the stations it could be consulted by written oracles, and while en route during the procession, it could be asked a question to which it would respond yes or no by bowing fore or aft.

Some priests marched before the bark wafting incense and others alongside and behind. Some bore standards representing nomes, much like the tribal procession of the Ark of the Covenant.

Of interest here is that the coffins often housed copies of the Book of the Dead or small corn mummies. While the Ramesside letter and statue are not exact parallels to the Ark, they share the concept of texts placed beneath the feet of a god.

Like their divine counterparts, funerary barks functioned as a means of transport and mythological invocation. However, rather than transport images, they ferried the deceased to their tombs. As in the festivals, loud music accompanied burial processions. These

processions too were public, though the number of attendees naturally varied.

The bark’s trip to the tomb invoked the journey of the sun as it sailed to the land of the west. Like Ra in his solar bark, the deceased hoped to sail on a cycle of renewal and emerge with him at dawn.

Of course, I am not suggesting that the Ark of the Covenant was in fact a bark; only that the bark served as a model, which the Israelites adapted for their own needs. Thus, the Israelites conceived of the Ark not as an Egyptian boat with a prow and stern and oars, but as a rectangular object, more akin to the riverine boat that informs the shape of Noah’s Ark (6:14–16). Nevertheless, some of the bark’s other aspects remained meaningful in Israelite priestly culture. It still represented a throne and a footstool and so it still served as a symbol of the divine presence.

It continued to be a sacred object that one could consult for oracles, and its maintenance continued to be the exclusive privilege of the priests.

Moreover, there is evidence that it retained the chthonic [underworld] import of its Egyptian prototype. In part this comes from the very name that the Israelites gave the object, an ʾaro ̄n, which also, and perhaps primarily, means “coffin.” As such it appears in the narratives concerning the deaths of the patriarch Jacob (Gen 50:1–14) and his son Joseph (Gen 50:26), both of whom were embalmed according to Egyptian practice and placed in an ‘aron.

Like the Egyptian ʾaro ̄n in which the patriarchs were buried, the Ark of the Covenant was associated with new grain and the threshing floor. Thus, we find that the Ark’s miraculous crossing of the Jordan took place during harvest time (Josh 3:15).50 Later, when the Philistines captured the Ark they placed it in the temple of Dagon (1 Sam 1:5). Like Osiris, Dagon was associated with new grain and fertility and possessed chthonic aspects, with titles linking him to rites for the dead. Clearly, the chthonic aspect of the Israelite Ark and its association with grain were not lost on the Philistines. Moreover, when the Philistines found their god dismembered before the Ark, they sent it back on a newly constructed wagon. When it reached Beth-Shemesh, the villagers were harvesting grain.

I have argued that Egyptian sacred barks served as models for the Israelite Ark of the Covenant and that consequently the two objects share much in common in design, function, and cosmic import. While no particular bark can be singled out as a prototype for the Ark’s design, the object’s associations with death and fertility, its close relationship with the threshing floor, and the mention of the Israelites’ practice of Egyptian embalming in conjunction with the ʾaro ̄n are suggestive of the cult of Osiris.

Ptah-Sokar-Osiris was at once the creator, the sun, and judge of the underworld, and he was the patron god of craftsmen. Like Yahweh, he created the world by fiat and was a god of justice who rewarded the righteous and punished sinners with death.

It is in this context of Egyptian-Canaanite exchange, Israelite religious syncretism, and Levantine interest in Ptah-Sokar-Osiris that I envision the Israelites’ adaptation of the bark. Those features, functions, and associations that the Ark shared with its prototype represented facets of a shared taxonomy, aspects that made sense in both Egyptian and Israelite religious contexts before the object was integrated.

Thus, the Ark retained its significance as a throne and footstool and as the symbol of God’s presence, and it continued to be a source of oracles. By calling the object an ʾaro ̄n, the Israelites retained the Ark’s chthonic associations that resonated with the priestly conception of El Yahweh as a creator god to whom the first fruits are offered (Lev 23:9–14).

On the other hand, those features that did not resonate with the priestly conception of God were refashioned or reconceptualized. Thus, the object’s connection to a boat was obscured by referring to it as a “throne and footstool” and by naming it an ʾaro ̄n, which suggested its use as a coffin.

As a throne without a statue, the Ark visually conveyed the aniconic nature of Yahweh. As a casket without a body, it engrained the notion of Yahweh as a god who cannot die. Concomitantly, the deposition of the tablets into the ʾaro ̄n replaced any suggestion of a divine judge of the underworld with objects that represented Yahweh’s role as divine judge and lawgiver. Thus, Yahweh became the ruler of the entire cosmos from the heavens to the underworld, and “threshing” became an idiom for the judgment and dismemberment of Yahweh’s enemies.

By the time of the early Israelite monarchy, the Ark, like the god Yahweh, was perceived as entirely Israelite, though memory of its origins likely remained and required negotiation. Hence, it was integrated retroactively into the national epic of the Exodus and intimately tied to Egypt and the first harvest festival. This gave the object an etiology that distinguished it from Egyptian religious practice, one that served the needs of the priesthood, the royal house, and the national epic.

As the centerpiece of the Israelite sanctuary, the Ark of the Covenant stood as the symbolic presence of Yahweh and his legitimation of the Levitical priesthood. As the Lord of Hosts who rides upon the kerubıˆm, the Ark legitimated the royal house and its wars. As an Egyptian object transformed and detourned, it offered visual and literary validation of the Exodus. ~

https://faculty.washington.edu/snoegel/PDFs/articles/noegel-ark-2015.pdf

more on the Ark of Covenant:

~ The ark has a number of seemingly magical powers, according to the Hebrew Bible. In one story, the Jordan River stopped flowing and remained still while a group of priests carrying the ark crossed the river. Other stories describe how the Israelites took the ark with them into battle where the powers of the ark helped the Israelites defeat their enemies.

When the ark was captured by the Philistines, outbreaks of tumors and disease afflicted them, forcing the Philistines to return the ark to the Israelites. Some stories describe how death would come to anyone who touched the ark or looked inside it.

There are two biblical stories describing the construction of the ark. The first, and most famous version, is found in the Book of Exodus and describes how a large amount of gold was used to build the ark. The second version, found in the Book of Deuteronomy, briefly describes the construction of an ark made just of wood.

The story of the construction of the ark told in the Book of Exodus describes in great detail how God ordered Moses to tell the Israelites to build an ark out of wood and gold, with God supposedly giving very precise instructions.

"Have them make an ark of acacia wood — two and a half cubits [3.75 feet or 1.1 meters] long, a cubit and a half [2.25 feet or 0.7 meters] wide, and a cubit and a half [2.25 feet] high. Overlay it with pure gold, both inside and out, and make a gold molding around it." Exodus 25:10-11.

Poles made of acacia wood and gold were used to carry the ark and two cherubim were to be sculpted out of gold and placed on the lid of the ark. "The cherubim are to have their wings spread upward, overshadowing the cover with them. The cherubim are to face each other, looking toward the cover." Exodus 25:20. Tablets engraved with the Ten Commandments were placed inside the ark.

The Hebrew Bible directed that the Ark of the Covenant be placed within a movable shrine known as the tabernacle. A curtain that prevented people from viewing the Ark of the Covenant was set up within the tabernacle and an altar and incense burners were placed in front of the curtain. The incense was made of gum resin, onycham, galbanum and frankincense, and was to be burned by Aaron, the brother of Moses, and his sons at morning and sunset.

A man named Bezalel was chosen by God to build the Ark of the Covenant and furnishings located within the tabernacle, according to the Hebrew Bible. "I have filled him with the Spirit of God, with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge and with all kinds of skills — to make artistic designs for work in gold, silver and bronze, to cut and set stones, to work in wood, and to engage in all kinds of crafts." Exodus 31:3-5. Oholiab was chosen by God to be Bezalel's assistant, with skilled craftsmen helping them, the Hebrew Bible says.

During the reign of King Solomon, the First Temple, which is the holiest place in Judaism, was constructed in Jerusalem and the Ark of the Covenant was placed in an inner sanctuary covered in gold, the Hebrew Bible says.

The Book of Deuteronomy, on the other hand, tells the story of the construction of a much more modest Ark of the Covenant. The book says that at one point the Israelis were worshiping a golden calf instead of God. Moses was so enraged by this that he smashed the stone tablets engraved with the Ten Commandments. God ordered Moses to help create new tablets engraved with the Ten Commandments and create a wooden ark that they could be placed in.

"Chisel out two stone tablets like the first ones and come up to me on the mountain. Also make a wooden ark. I will write on the tablets the words that were on the first tablets, which you broke. Then you are to put them in the ark." Deuteronomy 10:1-2.

"So I [Moses] made the ark out of acacia wood and chiseled out two stone tablets like the first ones, and I went up on the mountain with the two tablets in my hands. The Lord wrote on these tablets what he had written before, the Ten Commandments he had proclaimed to you on the mountain…." Deuteronomy 10:3-4. Moses then put the tablets inside the wooden ark.

The ark vanished when the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem in 587 B.C.

It's not known what happened to the ark after the First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonians. According to the Book of Maccabees, the ark was hidden in a cave on Mount Nebo by the prophet Jeremiah who said that this "place shall remain unknown until God gathers his people together again and shows his mercy." 2 Maccabees 2:7.

The Book of Revelation claims that the ark will not be seen again until the end times. "Then God's temple in heaven was opened, and within his temple was seen the Ark of his Covenant. And there came flashes of lightning, rumblings, peals of thunder, an earthquake and a severe hailstorm." Revelation 11:19. ~

https://www.livescience.com/64932-the-ark-of-the-covenant.html

Oriana:

So, first there is a tremendous fuss about the Ark — but after it vanishes during the Babylonian conquest, no one seems to make a big deal about it. The most sacred object, once placed in the Holy of Holies, was gone — so what!! It’s in an unknown location — or so we assume, since it's never mentioned in the Bible again.

I always found this rather astonishing, but then it’s only one of the many puzzles that the bible presents us with. I feel a sudden affection for the nun who "explained" why god no longer speaks to us by saying, with a sad little smile, "The times were different then."

I realize that the source of this article is not stellar, to put it mildly, but the explanation seems clear and simple. The Ark vanishes during the Babylonian conquest and is never seen again. End of story.

(What is the literal meaning of "ark"? It's an archaic word for a chest or box. It can also mean a large, flat-bottomed boat. But just think if we said, "The Box of Covenant." The romance and the mystery would be shattered.)

*

“JESUS WITHOUT LIES” VERSUS “CHRIST CONSCIOUSNESS” VERSUS “COSMIC CONSCIOUSNESS”

I wonder if some salvaging of Jesus is possible — "Jesus without lies." But so much text would have to removed that it's easier to leave behind the doctrine and stories, and think in terms of "Christ consciousness." It could be defined as non-judgment, compassion, kindness, and "the kingdom is within." An ideal, not a person — but the initial connection with a person gives it more power for those of us who could be called “cultural Christians.”

Thus the story of the woman taken in adultery, and spared not only death, but condemnation (“Neither do I condemn thee), even though it’s a later addition, need no be regarded as “forgery.” No matter how the story originated, it is a perfect illustration of Christ consciousness. You can be an atheist and love the story.

Buddha consciousness is pretty much the same ideal, with freedom from desire as part of it. When a friend said, “You are suffering because you want something from her,” I experienced at least partial enlightenment. And it worked: I decided there was nothing I wanted from a certain person, and the suffering dissolved. As an unexpected bonus, I also suddenly began “getting respect” from that person.

"Cosmic consciousness" is just too abstract for me, and I suspect it’s too abstract and uncuddly for most people. And "cosmic consciousness" does not imply kindness. (And I doubt that it grants your requests, no matter how often New Age believers state, "I put it forth to the Universe that I need a new job.")

Returning to the subject of Christ versus Jesus, I’d totally remove the crucifix and of course any notion of the “bloody ransom.” Christ consciousness is the opposite of a vengeful deity who requires anyone’s death under torture “because someone has to pay the price.” Christ consciousness is the opposite of that idea.

On the other hand, I can imagine a supportive “Elohim consciousness” that breaks away from wrath, jealousy, vengefulness, narcissism, etc.

For me this meditation on the difference between “Jesus” and “Christ” goes back a long time. Already in childhood I noticed that the two words seemed to carry different overall meanings. Jesus was a person, Yoshua, a name like Tom or Bill. Christ was more abstract and mysterious. Only now I feel I've clarified it for myself: Christ is a concept, an ideal, and that ideal is meaningful to me.

Christ in the Sepulcher, Blake, 1805. Though this doesn't quite fit my message, I couldn't resist the angels here.

*

Hawaii's three active volcanoes provide a magnificent show, creating an eerie landscape with rivers of lava and molten rock. Why am I posting this? Alas, I no longer remember. Possibly to say that now we have science that can explain volcanic eruptions better than the idea of an angry volcano god or goddess.

But more likely, because I fell in love with the colors, especially that gorgeous deep blue in the sky.

*

WILL COVID GROW MILDER AND MILDER AS THE VIRUS EVOLVES?

~ The pandemic has been awash with slogans, but in recent weeks, two have been repeated with increasing frequency: “Variants will evolve to be milder” and “Covid will become endemic”. Yet experts warn that neither of these things can be taken for granted.

Those stating that viruses become less deadly over time often cite influenza. Both of the flu viruses responsible for the 1918 Spanish flu and 2009 swine flu pandemics eventually evolved to become less dangerous. However, the 1918 virus is thought to have become more deadly before it became milder. And other viruses, such as Ebola, have become more dangerous over time.

“It’s a fallacy that viruses or pathogens become milder. If a virus can continue to be transmitted and cause lots of disease, it will,” said Prof David Robertson, head of viral genomics and bioinformatics at the University of Glasgow’s Centre for Virus Research.

Viruses aim to create as many copies of themselves and spread as widely as possible. Although it is not always in their best interests to kill their hosts, so long as they are transmitted before this happens, it doesn’t matter. Sars-CoV-2 doesn’t kill people during the period when it is most infectious; people tend to die two to three weeks after becoming ill. Provided it does not evolve to make people so ill that they do not, or cannot, mix with other people while they are infectious, the virus doesn’t care if there are some casualties along the way.

Neither is it clear that Sars-CoV-2 is becoming progressively milder. Omicron appears to be less severe than the Alpha or Delta variants – but both of these variants caused more severe illness than the original Wuhan strain. Importantly, viral evolution is not a one-way street: Omicron did not evolve from Delta, and Delta didn’t evolve from Alpha – it is more random and unpredictable than that.

“These [variants of concern] are not going one from the other, and so if that pattern continues, and another variant pops out in six months, it could be worse,” said Robertson. “It’s important not to assume that there’s some inevitability for Omicron to be the end of Sars-CoV-2’s evolution.”

There is a possibility that Omicron is so transmissible that it has hit a ceiling whereby future variants will struggle to outcompete it. But just a few months ago, people were saying the same thing about Delta. Also, Omicron is likely to keep evolving. “What might play out is that as Omicron infects so many people, it’s harder for that first Omicron [variant] to continue to be as successful, and so that creates a space for a virus that’s better at evading the immune response,” Robertson said.

What about the idea that Sars-CoV-2 could become endemic? Politicians tend to use this as a proxy for getting on with our lives and forgetting that Covid-19 exists. What endemic actually means is a disease that’s consistently present, but where rates of infection are predictable and not spiraling out of control.

“Smallpox was endemic, polio is endemic, Lassa fever is endemic, and malaria is endemic,” said Stephen Griffin, associate professor of virology at the University of Leeds. “Measles and mumps are endemic, but dependent on vaccination. Endemic does not mean that something loses its teeth at all.”

As more and more people develop immunity to Sars-CoV-2, or recover from infection, the virus may become less likely to trigger severe disease. But it could then evolve again. The good news is that this becomes less likely the more of the world’s population is vaccinated – because the fewer people who are infected, the fewer chances the virus has to evolve – but we’re not close to that yet. Even in the UK, there are large numbers of unvaccinated individuals, and it’s unclear how long the protection from boosters will last.

“The idea that we will achieve endemicity anytime soon also seems a little bit counter to the fact that we’ve just had several weeks of massively explosive exponential growth, and prior to that, we were still seeing exponential growth of Delta,” Griffin said.

Transforming Covid into a disease that we can truly live with requires more than a national vaccination campaign and wishful thinking; it requires a global effort to improve surveillance for new variants, and supporting countries to tackle outbreaks at source when they emerge. It also requires greater investment in air purification and ventilation to reduce transmission within our own borders, if we’re mixing indoors.

Everyone hopes that the coronavirus will evolve to become milder, and that Covid becomes endemic – or rather, manageable enough not to blight our daily lives. But these are hopes, not facts, and repeating these mantras won’t make them happen any faster. ~

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/11/will-covid-19-become-less-dangerous-as-it-evolves?utm_source=pocket_discover

Oriana:

People are getting awfully tired of this pandemic. But we should still wear a mask when indoors. Luckily, a simple mask protects not only from Covid (or at least severe Covid), but also from flu and air-borne allergens.

The evolution of the virus, never predictable, is not the only factor here. Our immune system also evolves and learns how to fight the virus, whether by means of an infection or vaccination. The immunity acquired through infection appears to be stronger than the relatively short-lasting immunity due to a vaccine. Still, vaccines are very helpful in preventing severe illness, hospitalization, and death. Anti-vaxxers always manage to bring up anecdotes to the contrary, but even if true, those cases are exceptions. Unless you have an underlying condition such as significant obesity and/or diabetes, there is no reason to expect the average vaccinated person to be an exception.

Will omicron be it, the last wave of the pandemic? Maybe. Perhaps it's more important to consolidate our lessons so that we can be prepared for the next pandemic. Alas . . .

*

DO DIETARY LECTINS CAUSE DISEASE?

~ In 1988 a hospital launched a “healthy eating day” in its staff canteen at lunchtime. One dish contained red kidney beans, and 31 portions were served. At 3 pm one of the customers, a surgical registrar, vomited in theater. Over the next four hours 10 more customers suffered profuse vomiting, some with diarrhea. All had recovered by next day. No pathogens were isolated from the food, but the beans contained an abnormally high concentration of the lectin phytohemagglutinin.

Lectins are carbohydrate binding proteins present in most plants, especially seeds and tubers like cereals, potatoes, and beans. Until recently their main use was as histology and blood transfusion reagents, but in the past two decades we have realized that many lectins are (a) toxic, inflammatory, or both; (b) resistant to cooking and digestive enzymes; and (c) present in much of our food. It is thus no surprise that they sometimes cause “food poisoning.” But the really disturbing finding came with the discovery in 1989 that some food lectins get past the gut wall and deposit themselves in distant organs. So do they cause real life diseases?

This is no academic question because diet is one part of the environment that is manipulable and because lectins have excellent antidotes, at least in vitro. Because of their precise carbohydrate specificities, lectins can be blocked by simple sugars and oligosaccharides. Wheat lectin, for example, is blocked by the sugar N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) and its polymers. These natural compounds are potentially exploitable as drugs should lectin induced diseases be identified.

Wheat gliadin, which causes celiac disease, contains a lectin like substance that binds to human intestinal mucosa, and this has been debated as the “celiac disease toxin” for over 20 years. But celiac disease is already managed by gluten avoidance, so nothing would change were the lectin hypothesis proved. On the other hand, wheat lectin also binds to glomerular capillary walls, mesangial cells, and tubules of human kidney and (in rodents) binds IgA and induces IgA mesangial deposits. This suggests that in humans IgA nephropathy [kidney disease] might be caused or aggravated by wheat lectin; indeed a trial of gluten avoidance in children with this kidney disease reported reduced proteinuria and immune complex levels.

Of particular interest is the implication for autoimmune diseases. Lectins stimulate class II HLA antigens on cells that do not normally display them, such as pancreatic islet and thyroid cells. The islet cell determinant to which cytotoxic autoantibodies bind in insulin dependent diabetes mellitus is the disaccharide N-acetyl lactosamine, which must bind tomato lectin if present and probably also the lectins of wheat, potato, and peanuts. This would result in islet cells expressing both class II HLA antigens and foreign antigen together—a sitting duck for autoimmune attack. Certain foods (wheat, soya) are indeed diabetogenic in genetically susceptible mice. Insulin dependent diabetes therefore is another potential lectin disease and could possibly be prevented by prophylactic oligosaccharides.

Another suspect lectin disease is rheumatoid arthritis. The normal human IgG molecule possesses carbohydrate side chains, which terminate with galactose. In rheumatoid arthritis much of the galactose is missing, so that the subterminal sugar—N-acetyl glucosamine—is exposed instead. These deficient IgG molecules feature strongly in the circulating immune complexes that cause fever and symptoms. In diet responsive rheumatoid arthritis one of the commonest trigger foods is wheat, and wheat lectin is specific for N-acetyl glucosamine—the sugar that is normally hidden but exposed in rheumatoid arthritis. This suggests that N-acetyl glucosamine oligomers such as chitotetraose (derived from the chitin that forms crustacean shells) might be an effective treatment for diet associated rheumatoid arthritis. Interestingly, the health food trade has already seized on N-acetyl glucosamine as an antiarthritic supplement.

Among the effects observed in the small intestine of lectin fed rodents is stripping away of the mucous coat to expose naked mucosa and overgrowth of the mucosa by abnormal bacteria and protozoa. Lectins also cause discharge of histamine from gastric mast cells, which stimulates acid secretion. So the three main pathogenic factors for peptic ulcer—acid stimulation, failure of the mucous defense layer, and abnormal bacterial proliferation (Helicobacter pylori) are all theoretically linked to lectins. If true, blocking these effects by oligosaccharides would represent an attractive and more physiological treatment for peptic ulcer than suppressing stomach acid. The mucus stripping effect of lectins also offers an explanation for the anecdotal finding of many allergists that a “stone age diet,” which eliminates most starchy foods and therefore most lectins, protects against common upper respiratory viral infections: without lectins in the throat the nasopharyngeal mucus lining would be more effective as a barrier to viruses.

But if we all eat lectins, why don’t we all get insulin dependent diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, IgA nephropathy, and peptic ulcers? Partly because of biological variation in the glycoconjugates that coat our cells and partly because these are protected behind a fine screen of sialic acid molecules, attached to the glycoprotein tips. We should be safe. But the sialic acid molecules can be stripped off by the enzyme neuraminidase, present in several micro-organisms such as influenzaviruses and streptococci. This may explain why diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis tend to occur as sequelae of infections. This facilitation of lectins by micro-organisms throws a new light on postinfectious diseases and makes the folklore cure of fasting during a fever seem sensible.

Alternative medicine popularizers are already publishing articles about dietary lectins, often with more enthusiasm than caution, so patients are starting to ask about them and doctors need to be armed with facts. The same comment applies to entrepreneurs at the opposite end of the commercial spectrum. Many lectins are powerful allergens, and prohevein, the principal allergen of rubber latex, is one. It has been engineered into transgenic tomatoes for its fungistatic properties, so we can expect an outbreak of tomato allergy in the near future among latex sensitive individuals. Dr Arpad Pusztai lost his job for publicizing concerns of this type. ~

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1115436/

*

FOODS HIGH IN LECTINS

These six foods are some of the worst sources of lectins in the American diet when consumed raw.

1. Raw Kidney Beans

Red kidney beans are a great source of plant-based protein and they are a low-glycemic-index food. However, it’s critical that you boil them thoroughly before you eat them. Eating raw or undercooked kidney beans exposes you to an incredibly high level of phytohemagglutinin. Cooking beans thoroughly reduces the activity of this lectin to undetectable levels.

2. Peanuts

Peanuts are another form of legume, and like kidney beans, they contain lectins. Peanut lectins can be detected in the blood after eating peanuts in large amounts. While no studies have been done to determine whether this has health effects, it does show that peanut lectins are absorbed by the body.

3. Whole Grains

Raw wheat and other whole grains are high in lectins. Raw wheat germ, which is often sold as a source of fiber, can contain as much as 300 mcg of wheat lectins per gram. If you’re trying to avoid lectins, do not eat raw whole grains.

4. Raw Soybeans

Soybeans are another legume that’s full of lectins. However, unlike some other legumes, soybeans are often eaten toasted or roasted. This type of dry heat does not appear to be as effective at breaking down lectins as boiling. Be cautious when eating raw or toasted soybeans if you are avoiding lectins.

5. Raw Potatoes

Potatoes are part of the nightshade family and contain high levels of lectins. Raw potatoes, in particular the skin, appear to contain potentially harmful lectins that may affect your health.

All of the above foods have associated health benefits as well as lectins. In most cases, cooking these foods with “wet” heat, such as stewing, boiling, cooking in sauce, or mixing into dough and baking, breaks down lectins to negligible levels. Simply avoid eating raw legumes, grains, or potatoes, and eat these foods cooked instead. ~

https://www.webmd.com/diet/foods-high-in-lectins#1

Oriana:

I would say the same for tomatoes, another member of the nightshade family. To eat them raw, you should ideally remove the skin and seeds. The skin is easy to removed after pouring boiling water on the fruit. But I know, I know. It’s easier just to avoid raw tomatoes.

I remember when wheat germ was the hottest superfood, and some people claimed that all food should be eaten raw; cooked food is doom. But not so long ago it’s become popular knowledge that lectins exist in raw plant food with peels and seeds (no need to worry leafy greens) and can cause disease (in the case of ricin, a lectin in castor beans, death).