Kraków is famous for its legend of the Wawel Dragon. Here finally is a snow dragon on the bank of the Vistula. Photo: Anna Stępień

Kraków is famous for its legend of the Wawel Dragon. Here finally is a snow dragon on the bank of the Vistula. Photo: Anna Stępień*

ODYSSEUS IN BARSTOW

If you knew how much suffering awaits you,

you would stay with me and be deathless,

croons Calypso of the Tidy Braids —

but bronze-armed Odysseus

only broods on the beach.

His gaze caresses the watery horizon.

He wants his own life, its breakable glory.

He wants to be Odysseus. We praise forever

the man who chose not to be a god.

I wonder, though: would I choose a life rich

with the journey, yet doomed to lap

at the shores of less and less?

I could sail an infinity of sunsets

shipwrecked in Barstow, California,

in a tract named Desert Meadows,

married beyond return

to a gun collector, TV on loud,

scrawny palm trees rasping in dry wind —

returning home to read about Odysseus.

I build a monument of pebbles

to the pebbles in Barstow, California.

Memorialize a dung beetle’s march.

Every cloudlet with its knife-blade shadow.

Every fissure in the sun-struck ground.

Trace the faces of the dead in the dust.

It’s the silent dead who sing

life’s siren song: the miracle of existence. Even

in Barstow, caressed by the moonlight.

~ Oriana

*

VASILY GROSSMAN: MYTHS AND COUNTER-MYTHS

~ Western readers have long tended to divide Soviet writers into two classes: corrupt time-servers and heroic, dissident martyrs. It has been hard for a Soviet writer to attract widespread attention in the English-speaking world except through some major international scandal. Doctor Zhivago became a best seller because the Soviet authorities coerced Boris Pasternak into declining the Nobel Prize. Joseph Brodsky became known after being tried in court and then sent into exile in the Far North. Alexander Solzhenitsyn became ever more famous as the authorities stepped up the pressure against him and eventually deported him in 1974. Great writers with less dramatic biographies have often gone unnoticed. Andrey Platonov, for example, has only very slowly gained Western recognition. And Vasily Grossman was more or less ignored for several decades — until we learned the story of the KGB “arresting” the manuscript of Life and Fate.

In the Soviet Union, needless to say, it was the other way round. To make a career for themselves, Soviet writers did all they could to embellish their proletarian and socialist credentials. Many had much to hide — and sometimes their attempts at camouflage took surprising forms. The highly successful poet and novelist Konstantin Simonov, for example, was the son of a princess and a tsarist officer; apparently he changed his first name from Kirill to Konstantin because he was unable to pronounce the sound “r” without an aristocratic lisp.

Vasily Grossman, too, had to keep quiet about some aspects of his background; not only did he have two paternal uncles living abroad, but his father had been a Menshevik — that is, a member of a socialist faction opposed to the Bolsheviks. And Grossman, of course, made much of the fact that Maxim Gorky, then the grand old man of Soviet literature, had encouraged him at the beginning of his career.

In 1932, Grossman was struggling to publish his first novel, Glück Auf, set in a mining community in the Donbas region of Soviet Ukraine; an editor had told him that some aspects of the novel were “counter-revolutionary.” Gorky was, at the time, the most influential figure in the Soviet literary establishment, and Grossman tried to enlist his support. In his first letter to Gorky, Grossman wrote, “I described what I saw while living and working for three years at mine Smolyanka-11. I wrote the truth. It may be a harsh truth. But the truth can never be counter-revolutionary.” Gorky replied at length, clearly recognizing Grossman’s gifts but criticizing him with regard to his attitude to truth:

~ It is not enough to say, “I wrote the truth.” The author should ask himself two questions: First, which truth? And second, why? We know that there are two truths and that, in our world, it is the vile and dirty truth of the past that quantitatively preponderates. […] The author truthfully depicts the obtuseness of coal miners, their brawls and drunkenness, all that predominates in his — the author’s — field of vision. This is, of course, truth — but it is a disgusting and tormenting truth. It is a truth we must struggle against and mercilessly extirpate. ~

There is no doubt that this view of truth was anathema to Grossman. He argues against it both in Stalingrad and in Life and Fate. Unsurprisingly, Lipkin puts great emphasis on Grossman’s disagreement with Gorky, since this fits with the way he wishes to portray Grossman — as a proto-dissident. It is equally unsurprising that Lipkin says little about the central role played by Gorky in orchestrating Grossman’s remarkably successful literary debut, since this would conflict with that image. It is clear, however, that Grossman would not have come to prominence in the mid-1930s without Gorky’s help.

In late 1952 and early 1953, however, Grossman truly was in mortal danger. In October 1952, Stalingrad was nominated for a Stalin Prize by the Presidium of the Union of Soviet Writers. [23] Soon after this, Stalin’s anti-Jewish campaign escalated swiftly, and the novel, rather than being feted, was subjected to vicious attacks. But for Stalin’s death on March 5, 1953, Grossman might well have been arrested and shot. Even during those months, however, he can — at least in retrospect — be said to have been fortunate; he was one of only a few writers associated with the wartime Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee who survived. It is curious, incidentally, that such astute figures as Fadeyev and Alexander Tvardovsky (chief editor of the journal Novy Mir) seem to have failed to predict the intensity of the anti-Jewish campaign. They began publishing For a Just Cause during the very month — July 1952 — when most of the leading members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were undergoing secret trial, before being executed in August.

The “arrest” of Life and Fate in February 1961 was, of course, a crushing blow to Grossman. Nevertheless, the often-repeated suggestion that this brought about his death from cancer seems simple-minded. Even the belief that it plunged him into deep depression is questionable. For all Grossman’s trials, the three and a half years from the “arrest” of Life and Fate to his death were a remarkably creative period. As well as his vivid account of his two months in Armenia, he composed the finest of his short stories and around half of Everything Flows, including the trial of the four Judases, the account of the Terror Famine, and the chapters about Lenin and Russian history that constitute one of the greatest passages of historico-political writing in Russian. In a letter to his wife in October 1963, he himself wrote, “I’m in good spirits, and I’m working eagerly. This greatly surprises me — where do these good spirits come from? I feel I should have thrown up my hands in despair long ago, but they keep stupidly reaching out for more work.” ~

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/vasily-grossman-myths-and-counter-myths/

from Wiki:

~ Born to a Jewish family in Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, Grossman trained as a chemical engineer at Moscow State University, earning the nickname Vasya-khimik ("Vasya the Chemist") because of his diligence as a student. Upon graduation he took a job in Stalino (now Donetsk) in the Donets Basin. In the 1930s he changed careers and began writing full-time, publishing a number of short stories and several novels. At the outbreak of the Second World War, he was engaged as a war correspondent by the Red Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda; he wrote first-hand accounts of the battles of Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, and Berlin. Grossman's eyewitness reports of a Nazi extermination camp, following the discovery of Treblinka, were among the earliest accounts of a Nazi death camp by a reporter.

While Grossman was never arrested by the Soviet authorities, his two major literary works (Life and Fate and Forever Flowing) were censored by the Krushchev regime as unacceptably anti-Soviet.

At the time of Grossman's death from stomach cancer in 1964 these books remained unreleased. Hidden copies were eventually smuggled out of the Soviet Union by a network of dissidents, including Andrei Sakharov and Vladimir Voinovich, and first published in the West in 1980, before appearing in the Soviet Union in 1988.

Grossman's first marriage ended in 1933, and in the summer of 1935 he began an affair with Olga Mikhailovna Guber, the wife of his friend, the writer Boris Guber. Grossman and Olga began living together in October 1935, and they married in May 1936, a few days after Olga and Boris Guber divorced. In 1937 during the Great Purge Boris Guber was arrested, and later Olga was also arrested for failing to denounce her previous husband as an "enemy of the people". Grossman quickly had himself registered as the official guardian of Olga's two sons by Boris Guber, thus saving them from being sent to orphanages. He then wrote to Nikolay Yezhov, the head of the NKVD, pointing out that Olga was now his wife, not Guber's, and that she should not be held responsible for a man from whom she had separated long before his arrest. Grossman's friend, Semyon Lipkin, commented, "In 1937 only a very brave man would have dared to write a letter like this to the State's chief executioner." Astonishingly, Olga Guber was released.

Because of state persecution, only a few of Grossman's post-war works were published during his lifetime. After he submitted for publication his magnum opus, the novel Life and Fate, 1959, the KGB raided his flat. The manuscripts, carbon copies, notebooks, as well as the typists' copies and even the typewriter ribbons were seized.

Grossman wrote to Nikita Khrushchev: "What is the point of me being physically free when the book I dedicated my life to is arrested... I am not renouncing it... I am requesting freedom for my book." However, Life and Fate and his last major novel, Everything Flows (Все течет, 1961) were considered a threat to the Soviet power and remained unpublished. Grossman died in 1964, not knowing whether his greatest work would ever be read by the public. ~

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasily_Grossman

about Life and Fate

~ A book judged so dangerous in the Soviet Union that not only the manuscript but the ribbons on which it had been typed were confiscated by the state, Life and Fate is an epic tale of World War II and a profound reckoning with the dark forces that dominated the twentieth century.

Interweaving a transfixing account of the battle of Stalingrad with the story of a single middle-class family, the Shaposhnikovs, scattered by fortune from Germany to Siberia, Vasily Grossman fashions an immense, intricately detailed tapestry depicting a time of almost unimaginable horror and even stranger hope.

Life and Fate juxtaposes bedrooms and snipers’ nests, scientific laboratories and the Gulag, taking us deep into the hearts and minds of characters ranging from a boy on his way to the gas chambers to Hitler and Stalin themselves.

This novel of unsparing realism and visionary moral intensity is one of the supreme achievements of modern Russian literature. ~ (introduction on Amazon)

Oriana:

Life and Fate has been called the War and Peace of the twentieth century.

~ Perhaps there is no story more emotionally devastating in the book than the story of Sofya Levinton, a Jewish friend of Lyudmila’s who has the misfortune of being snared by the Nazis and put on a cattle train to Auschwitz. On the train Sofya runs into David, a six or seven year-old boy who also shared the misfortune of being cut off from his mother and put in a ghetto with his grandmother. When his grandmother died of disease, the woman she had entrusted David to was too busy trying to save herself. Like two atomic particles randomly bumping into each other by accident, David and Sofya bump into each other on the train. They have no one else, so they have each other. They accompany each other into the camp, into the dressing room, and finally into the gas chamber where there is no light, no life, no meaning. As the Zyklon B starts hissing from the openings above, David clings to the unmarried, childless Sofya:

“Sofya Levinton felt the boy’s body subside in her hands. Once again she had fallen behind him. In mineshafts where the air becomes poisoned, it is always the little creatures, the birds and mice, that die first. This boy, with his slight, bird-like body, had left before her.

‘I’ve become a mother,’ she thought.

That was her last thought.”

*

~ Ashutosh S. Jogalekar, Amazon

Mary:

Powerful testament to what is most human, that need to connect, to love, even in extremity, even in the last seconds of life.

*

Let’s put God – and all these grand progressive ideas – to one side. Let’s begin with man; let’s be kind and attentive to the individual man – whether he’s a bishop, a peasant, an industrial magnate, a convict in the Sakhalin Islands or a waiter in a restaurant. Let’s begin with respect, compassion and love for the individual – or we’ll never get anywhere.” ~ Anton Chekhov

*

DENIS VILLENEUVE’S HUMANISTIC “DUNE”

~ The appeal of science fiction comes from extrapolating the future of intelligent life from existing patterns in society. These stories can feel as endlessly fascinating as staring into a fun house mirror, marveling at how your face appears reflected across an unfamiliar topography. Where would I fit in if Earth became sentient and rejected humans? What would I do if an alien planet made the dead come back to life?

But this need to extrapolate is also science fiction’s limitation. Many of the human patterns available to authors as the foundations of their worlds are arbitrary—the product of historical contingency, material fact, or luck—or the manifestations of power misunderstood as axioms, especially where they involve race and gender. “Science fiction, more than any other genre, deals with change—change in science and technology, and social change,” Octavia Butler wrote in her 1980 essay “The Lost Races of Science Fiction.” “But science fiction itself changes slowly, often under protest.” The challenge of science fiction is in finding a premise expansive enough to avoid reproducing those errors.

Herbert’s Dune draws on a wide range of references—the idea for the novel began as a magazine article about Oregon’s sand dunes; Herbert also read sociology, poetry, Marxism, the history of 19th-century wars in the Caucasus—and both the novel and film are studded with bits of culture from recent human history, familiar things sealed against the passage of time: bagpipes playing at a military ceremony, bullfighting, the name Duncan Idaho (Paul’s combat trainer, played by Jason Momoa), snippets of Christian verse, religious habits that echo those of medieval nuns worn by a mystical order called the Bene Gesserit. In one scene, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), the powerful companion of Duke Leto Atreides (Oscar Isaac), wears an updated version of chopines, the 16th-century platform shoe that holds associations with nobles and courtesans. These details make the world of Dune feel more convincingly real: 20,000 years into the future, not everything has been replaced, and random artifacts of Earth’s history remain.

Beyond those details, the axiom at the center of the story is relatively simple in its pessimism. People will do incredible things and commit incredible acts of destruction for a charismatic leader; such leaders will use their followers to consolidate power. The political system of Dune, an exponentially more technologically advanced society than our own, is space feudalism built on extractive colonialism. Assassination attempts are common, oppression is an acceptable tool, and dinners matter a great deal. The film ends with Paul pursuing a path that will not fundamentally alter the system that destroyed his family, that instead will merely give him a better place in its hierarchy, while visions of a bloody religious war to be waged in his name loom in the future. (Villeneuve’s adaptation leaves this conflict for a sequel, which will be released in 2023.)

Still, the story takes place at a moment when its motivating axiom and the structures that reinforce it begin to lose their soundness. In an early scene, an elder of the Bene Gesserit, having put Paul through a potentially fatal test to see if he might be the messianic figure the order has worked to produce, rebukes Jessica for her concern about her son’s fate: “Our plans are measured in centuries,” she says, a scale that makes the life of any person other than the predestined leader insignificant.

But the film soon contradicts this longer view: Once Paul and Jessica flee and join the Fremen in the desert, every unit of time matters, and no life is insignificant, even after death—bodies are recovered to preserve the water they retain, essential for survival on the desert planet. Fate is not abstract but an immediate existential problem—a familiar shift in perspective for those living in a time of historic floods, storms, droughts, and fires. This aspect of Dune reminds me of a line from an essay by Garry Wills on a new translation of the Bible, in which he argues that from the rushed, “traffic-jam” prose of the Gospels, one can glean how “every aspect of the New Testament should be read in light of [the] ‘good news’ that the world will shortly be wiped out.” Paul’s arrival on Arrakis bears the same apocalyptic assurance for the Fremen.

Perhaps this is what makes Dune still feel relevant: It offers a view from inside a planetwide cataclysm, when tenets that seemed unshakable fall, and their alternatives—some terrible, some utopian—become newly tangible. “When you have lived with prophecy for so long, the moment of revelation is a shock,” one character tells Jessica. Paul’s arrival signals to Dr. Liet Kynes (Sharon Duncan-Brewster), a state official who secretly occupies an influential position in Fremen society, that her dreams of terraforming the desert planet might become reality: “Arrakis could have been a paradise…but then the spice was discovered. And suddenly no one wanted the desert to go away,” she tells Paul and Jessica. Under the current imperial government, the undertaking was considered too costly and endangered a lucrative market; with the disruption the Atreides bring, altering the planet’s climate becomes conceivable.

For all its futuristic technology and sandworms, Dune is deeply humanistic, which does not mean it necessarily celebrates humanity, but rather in the sense that Greek tragedies of hubris and self-annihilation are humanistic. Its contribution to the sci-fi canon is the idea that the new order that replaces the old is never purely liberating; it cannot be indifferent to its revolutionaries’ self-interest. The ideals that orient change are human inventions and always, on some level, are made in the image of their creators. Jessica describes the messianic figure her order seeks as one transcending biological limitations, possessing “a mind powerful enough to bridge space and time, past and future. Who can help us into a better future.” Villeneuve’s Dune shows its protagonist before he assumes that power, and it maintains a sense of ambivalence, an outlook that asks how the future a revolution produces will be better than what came before. ~

https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/dune-film-review/

ROGER EBERT’S COMPLEX REVIEW

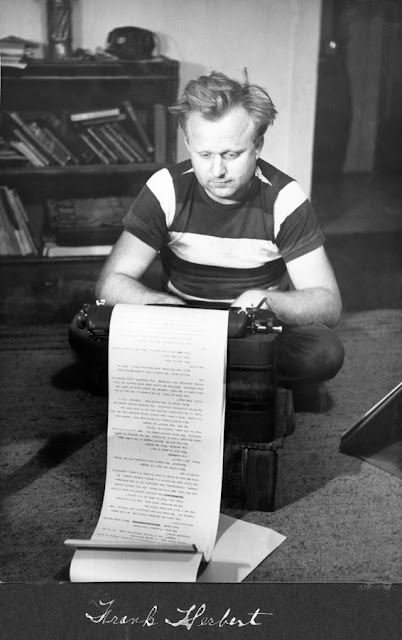

~ Back in the day, the two big counterculture sci-fi novels were the libertarian-division Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert Heinlein, which made the word “grok” a thing for many years (not so much anymore; hardly even pops up in crossword puzzles today) and Frank Herbert’s 1965 Dune, a futuristic geopolitical allegory that was anti-corporate, pro-eco-radicalism, and Islamophilic. Why mega-producers and mega-corporations have been pursuing the ideal film adaptation of this piece of intellectual property for so many decades is a question beyond the purview of this review, but it’s an interesting one.

“Dune” is set in the very distant future, in which humanity has evolved in many scientific respects and mutated in a lot of spiritual ones. Wherever Earth was, the people in this scenario aren’t on it, and the imperial family of Atreides is, in a power play we don’t become entirely conversant with for a while, tasked with ruling the desert planet of Arrakis. Which yields something called “the spice”—that’s crude oil for you eco-allegorists in the audience—and presents multivalent perils for off-worlders (that’s Westerners for you geo-political allegorists in the audience).

Throughout, the filmmaker, working with amazing technicians including cinematographer Greig Fraser, editor Joe Walker, and production designer Patrice Vermette, manages to walk the thin line between grandeur and pomposity in between such unabashed thrill-generating sequences as the Gom Jabbar test, the spice herder rescue, the thopter-in-a-storm nail-biter, and various sandworm encounters and attacks. If you’re not a “Dune” person these listings sound like gibberish, and you will read other reviews complaining about how hard to follow this is. It’s not, if you pay attention, and the script does a good job with exposition without making it seem like EXPOSITION. Most of the time, anyway. But, by the same token, there may not be any reason for you to be interested in “Dune” if you’re not a science-fiction-movie person anyway. The novel’s influence is huge, particularly with respect to George Lucas. DESERT PLANET, people. The higher mystics in the “Dune” universe have this little thing they call “The Voice” that eventually became “Jedi Mind Tricks.” And so on.

Villeneuve’s massive cast embodies Herbert’s characters, who are generally speaking more archetypes than individuals, very well. Timothée Chalamet leans heavily on callowness in his early portrayal of Paul Atreides, and shakes it off compellingly as his character realizes his power and understands how to Follow His Destiny. Oscar Isaac is noble as Paul’s dad the Duke; Rebecca Ferguson both enigmatic and fierce as Jessica, Paul’s mother. Zendaya is an apt, a better than apt, Chani. In a deviation from Herbert’s novel, the ecologist Kynes is gender-switched, and played with intimidating force by Sharon Duncan-Brewster. And so on.

The movie is rife with cinematic allusions, mostly to pictures in the tradition of High Cinematic Spectacle. There’s “Lawrence of Arabia,” of course, because desert. But there’s also “Apocalypse Now” in the scene introducing Stellan Skarsgård’s bald-as-an-egg Baron Harkonnen. There’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.” There are even arguable outliers but undeniable classics such as Hitchcock’s 1957 version of “The Man Who Knew Too Much” and Antonioni’s “Red Desert.” Hans Zimmer’s let’s-test-those-subwoofers score evokes Christopher Nolan.

These will tickle or infuriate certain cinephiles dependent on their immediate mood or general inclination. I thought them diverting. And they didn’t detract from the movie’s main brief. I’ll always love Lynch’s “Dune,” a severely compromised dream-work that (not surprising given Lynch’s own inclination) had little use for Herbert’s messaging. But Villeneuve’s movie is “Dune.” ~

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/dune-movie-review-2021

Oriana: INADEQUATE “WISDOM” PART

What struck me is how so many things in this movie reminded me of other movies, especially Lawrence of Arabia, a masterpiece compared to this Dune. Ebert (or whoever wrote this particular review) enumerates the many influences.

For me the most fascinating character was Lady Jessica. As the story unfolded, I wished for a different and more intellectually satisfying movie, with Jessica as the main character. I wanted to learn more about the Bene Gesserit’s breeding program and their mental and physical training. Would there be echoes of the Nietzsche-Nazi dream of the Overman? Or something more subtle, suffused with genuine wisdom?

While at least some Star Wars movies successfully combined the thrills of action and special effects with the mysterious wisdom training of the Jedi, the 2021 Dune merely hints at the superpowers to be gained by a rigorous quasi-religious practice. Buddhist? But the movie is already overly emotionally aloof (except for the exuberant Duncan Idaho, who seems to have wandered in from Zorba).

*

EVERYONE’S FAVORITE CHARACTER IN DUNE, DUNCAN IDAHO

~ If you’ve read Frank Hebert’s seminal 1965 novel (or further into the six-book series), it will come as little surprise that Duncan Idaho, the swordmaster who served House Atreides, is on his way to becoming as popular a character as he was in the books. There’s a lot to like about Duncan Idaho, even among those who might not love the newest adaptation of Dune; Jason Momoa, who plays Duncan in the 2021 film, compared him to Han Solo, which feels apt. He’s loyal, friendly, unyielding in battle, and he has the earliest and one of the more absurd names in Dune—and this comes in a book centered around a teenage boy who may or may not be the messiah named Paul.

Duncan Idaho is a name that sounds like sci-fi nonsense or the result of a Twitter prompt, i.e. “Your Dune name is your first pet’s name plus your home state.” Duncan is a Scottish name (and cited as an anglicized version of the Scottish-Gaelic name Donnchadh) that’s been in use for centuries and was the name of a character in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. An initial claim about the name Idaho in the 19th century is that it came from a Native American word meaning “gem of the mountains,” but those claims were debunked by contemporaneous sources, who claimed it was a made-up word; a recent column on the name Idaho’s possible origins leave more questions than answers. And Dune is set so far in the future that the state of Idaho may be little more than a fleeting memory that a Mentat (a human-computer used in lieu of an actual computer in a society that bans them) could recite off the top of their heads.

Mashed together, Duncan Idaho just might be one of the all-time great sci-fi names. [Oriana: It reminded me of “Indiana Jones.” Also, his Samurai invocation made me recall the Samurai Deli, one of the best SNL sketches ever.]

In Jason Momoa’s hands, Duncan is a charming shit-stirrer, someone who isn’t afraid to make fun of Timothée Chalamet’s Paul Atreides by making Paul think that he has muscles. He can easily pick Paul up and swing him around in a bone-crushing yet comforting hug, and every time Duncan shows up, everyone seems happy to see him. He’s also a key component in Duke Leto Atreides’ (Oscar Isaac) plan to rule Arrakis: Duncan is sent early to propose an alliance with the indigenous Fremen population, where he quickly learns their ways and is able to explain them to House Atreides.

“Duncan Idaho is a cross-mix between a samurai and one of the best knights in the galaxy, and also is known to be a beautiful man,” Villeneuve told Entertainment Weekly in September 2020. “So I needed all those elements. Jason also brought calm. It’s a Duncan who is very calm, very patient, with the deep soul of an explorer. He’s someone where you feel that if s— hits the fan, you want to be behind that guy! You know he will protect you.”

Duncan loves adventure and risk as much as anyone but he knows better than to let Paul head to Arrakis early even though Paul, haunted by one of his prophetic dreams, is trying to stop something terrible from happening to Duncan. And as we find out toward the end of Dune, Paul’s vision of Duncan Idaho’s death comes to pass.

Although the Sardaukar soldiers eventually kill him, Duncan Idaho manages to get up even after he’s been stabbed multiple times to kill a few more soldiers and goes out in a blaze of glory. (According to Children of Dune, Duncan Idaho took down 19 soldiers before he died.) ~

https://www.dailydot.com/unclick/dune-duncan-idaho/

Oriana:

Duncan Idaho is the only character who has warmth and a sense of humor in this otherwise very aloof movie. Unfortunately he’s such an exception that his warm personality only points out the lack of camaraderie and affection in the rest of the movie. It’s impossible not to like him. But it’s rather hard to like the rest of the characters. Paul is handsome in a boyish way, and that is saving grace; otherwise he too would be unbearable. Lady Jessica is borderline — a Wonder Woman of sorts. The Mother Superior is downright nasty. Is Bene Gesserit a crypto Catholic church, except in the female version (now that would be worth developing!)?

Basically it’s difficult to relate to anyone except Duncan Idaho, the lovable samurai.

*

How would I describe the movie in fewest words? TOO LOUD, TOO LONG, TOO VIOLENT, TOO DERIVATIVE, TOO ALOOF

Dune is an exhausting movie to watch on the large IMAX screen, with amplified sound that I found stressful. It’s the kind of action movie from which it takes a while to recover.

I'm tempted to say it’s not a movie for introverts, even though Paul Atreides, the main character, seems at least somewhat introverted. He’s definitely not the “life of the party” kind of person. He’s very pale and rather scrawny — my mother would have called him glista, the Polish word for earthworm — the negativity is lost in the translation, unless we settle simply for “worm.”

The movie is supposed to belong to Paul, but the only character who truly intrigued me was his mother, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson). She belongs to the religious society of Bene Gesserit. Like the Jedi, the women of Bene Gesserit possess unusual powers. For one thing, they can use The Voice, which compels the listener to carry out the speaker’s command. They can presumably choose the sex of their offspring, and this is where Jessica goes wrong in the eyes of the Reverend Mother: “You chose to waste the power on a male” (my favorite line in the whole movie, otherwise rather flat in dialogue).

The ponderous score mainly added to the movie’s overall noise. The dragonfly-based helicopters were interesting if not especially convincing. On the other hand, the personal shield protecting a warrior’s whole body seemed like an “of-course!” kind of invention.

The Fremen, the desert tribe that lives on the planet Arrakis (Iraq? and is the House of Atreides derived from the House of Atreus?), instantly reminded me of the Arabs in Lawrence of Arabia, one of the big influences on Herbert’s Dune. I'm afraid that in this movie too many things reminded me of other movies, so it just didn’t feel fresh. But Lady Jessica as a disobedient nun and Paul’s devoted mother did hold some fascination. She seemed to be the main character equally with Paul, though only he was the emergent Messiah (or Mahdi, to use the Freman — or, let's face it, Arabic — word for it). She was Paul’s Yoda, but without Yoda’s charm and endearing appearance. (Speaking of charm, this movie could badly use an equivalent of Star Wars’ R2D2.)

Another disappointment: lots and lots of hand-to-hand combat and the use of swords. With all the tremendously advanced technology, come on . . .

And why do we have to have Dukes and Emperors? "Baron Vladimir Harkonnen" sounds bizarre.

The only character who has emotional warmth is Duncan Idaho, the “samurai.” This is a cold, cold movie. If an emotional connection with the characters is important to you, you’ll be disappointed. The last words, “This is only the beginning,” will sound like a threat.

Part II is slated for 2023 or 2024. And perhaps next time there will be some actual Arab actors among the Fremen, and maybe even some desert animals (we got only brief flickers this time).

*

Mahdi — (Arabic: “guided one”) in Islamic eschatology, a messianic deliverer who will fill earth with justice and equity, restore true religion, and usher in a short golden age lasting seven, eight, or nine years before the end of the world. The Qurʾān does not mention him.

The concept of the Mahdi is a central tenet of Shi'a theology, but many Sunni Muslims also believe in the coming of a Mahdi, or rightly guided one, at the end of time to spread justice and peace. He will also be called Muhammad and be a descendant of the Prophet in the line of his daughter Fatima (Ali's wife).

*

Denise: (Facebook)

Uh...disappointed on several levels. First and most importantly, I felt that the actresses chosen for both Jessica and Chani were extremely poor choices and since the women in the story are so important, this bothered me. The story seemed to somehow have been neutered a bit, this affected the film's ability to really tell the story of who the characters are. And it bothers me no end that most of the Fremen were played by non-Middle Eastern-ancestry actors. Come on, folks; the way Arabs and other Middle Eastern desert dwellers have learned to live in the desert is a HUGE part of the storyline that Herbert based his Fremen on!!!!

And I guess it's not politically correct to have a villain be anything other than fat — Hollywood is fine with this stereotype but didn't dare to "do" Baron Harkonnen the way he really is. And I so wish they had allowed Dave Bautista to chew the scenery as the Beast Rabban. There was no sign that the Harkonnens are descended from Russians, either; I mean, why not? They made it clear that the Atreides are descended from the Spanish. And everything was so damn conventional. So not nearly science-fictional enough for me. I'll see the other films in the series just to finish it up, but it gets a C+ from me. Quite disappointed. The Lynch version will stand as the definitive version for me. This one was too much like that unwatchable bland TV version.

Oriana:

As you can imagine, there were quite a few comments in response to this brief review. This is a polarizing movie: some people love it, others can't endure it. It makes Lawrence of Arabia and the first episode of Star Wars (not the sequels and "prequels") look like masterpieces — especially Lawrence of Arabia, perhaps because it's based on history. As the Polish historical novelist Jozef Mackiewicz said, "Only the truth is interesting." I suspect this is correct. It's just that truth is messy and hard to get at, and art needs to simplify.

Spoiled as we are by Lawrence of Arabia, perhaps we need to be kinder to any movie-maker faced with adapting this sprawling material.

Charles:

I don't plan to see the second part.

Mary :

*

HOW AMERICA’S FIRST POLICEWOMAN TOOK DOWN AN INSIDIOUS L.A. CULT

~ For three months the world searched for Lily Maud Allen, who had vanished from her London home in November 1910. Some looking for her were convinced she was actually the mistress — and probable accomplice — of a man convicted of poisoning his wife. Others who hunted for her believed she was kidnapped by religious fanatics. Conniving seductress, or helpless victim: women were often put into one box or the other.

The following month, Allen reappeared on the other side of the Atlantic, arriving aboard the ocean liner St. Paul at Ellis Island. There she was detained by U.S. immigration officials at the request of British diplomats but slipped from their custody and once again was in the wind. Dockhands reported seeing her whisked away by men and women wearing dour, dark-blue uniforms. Their caps bore, in silver gilt, the words “Pillar of Fire.”

On February 4, 1911, Los Angeles police chief Charles Sebastian received an urgent letter from his counterpart in Denver. Rumor had it the missing young woman had traveled west from New York under an assumed name, Ruth Allen. The Pillar of Fire, a religious sect, had been founded ten years prior in Denver, but the city’s police chief couldn’t find her there. His message to Sebastian suggested that she might instead be hiding in the City of Angels, where the Pillar of Fire had burned strong for years.

Chief Sebastian knew just who should handle this case. The officer moved with ease through religious circles, could blend in among the cult’s mostly female ranks, and had already caused holy hell by petitioning to join the police. Her name was Alice Stebbins Wells. Widely regarded as America’s first female police officer, no one could have imagined she would be exactly what the city needed.

Alice, 36, explained that she didn’t aspire to use physical force, nor did she particularly want to make arrests. “I want to keep people from needing to be arrested.”

Alice pointed out that young men and women were visiting “undesirable cafes” and places of amusement in increasing numbers. “A woman could often stop that sort of thing,” she told the mayor, “where a man would only arouse antagonism. A woman knows better how to deal with situations where a girl’s welfare is concerned.”

Across America, female suspects suffered beatings and worse at the hands of arresting officers. The newspapers were full of such stories. The previous February, a German immigrant prostitute was battered during a routine arrest at a downtown Los Angeles barber shop that doubled as a boarding house. Rape was not unheard of. If the circumstances called for taking a woman into custody, Alice believed, female officers could do far better.

The mayor pointed out that no ordinance permitted a woman on the police force.

“I know that, but this,” she said, gesturing to a document she brought with her, “is the first step toward securing one.”

Alice had not marched into the red sandstone City Hall that day empty-handed. For months, she had courted leading citizens to her cause, eventually persuading 35 of them, preachers and bankers, rabbis and temperance activists, to affix their names to a petition demanding that a woman be allowed to serve as police officer.

She also brought with her a history of social work and gender breakthroughs. After high school, Kansas-born Alice Bessie Stebbins had moved to Chicago to work the World’s Columbian Exposition. While there, she was surrounded by a terrifying mystery: at least 9 but possibly as many as 200 young women like her, drawn to the Windy City by the fair, went missing. By the time the truth was revealed — the missing women had been murdered and cremated by one of American history’s most notorious serial killers, the charming doctor H. H. Holmes — Alice had begun a lifelong devotion to the welfare of vulnerable urban populations.

Working from settlement houses within Chicago’s working-class neighborhoods, she and other volunteers dispensed childcare, medicine, education, and other badly needed services to the Windy City’s poor. The next stop was Brooklyn’s famously progressive Plymouth Church. After apprenticing for a minister, she graduated from seminary, broke barriers preaching from the pulpit, and led her own congregation back in the Midwest. There she met Frank Wells, a farmer from Wisconsin, and on December 23, 1905, the couple married. She resigned from the ministry to raise a family — Alice and Frank had three children — and around 1909 a business opportunity for Frank landed the entire Wells family in California.

The disappearance of Lily Maud Allen was only the latest in a series of troubling events connected to the Pillar of Fire sect, led by a woman who preached radical equality of the sexes. Alma Bridwell White —48, tall and heavyset, with sunken eyes and grey hair — was a study in contradictions. She originally founded the Pillar of Fire in Denver, Colorado, after a group of Methodist ministers admonished her that a woman’s place was at home. She later reflected: “Men had held the reins of government in the church for nearly two thousand years, and it was time for a change.”

On the surface, the Pillar of Fire might have seemed a minor civic nuisance to most of Alice’s fellow Angelenos, no more dangerous than the food faddists and snake-oil salesmen who soapboxed in Central Park. Holy Jumpers, as its followers were called for their convulsive stomping, could be seen going door to door or standing on street corners in dour uniforms, selling gospel literature, like any number of fringe religious groups. Their views on modern life were considered amusing. According to one news report, Jumpers were “opposed to dancing, drinking, smoking, theatre-going, divorce, card-playing, novel reading, pretty clothes, rouge pots, Christmas trees, taxi-cabs, joy rides, hobble-skirts, peach basket hats, poodle dogs, massage parlors, manicure maids, chorus ladies, straight front corsets, artificial teeth, make-believe hips and busts, and highly seasoned mince pies” — all works of the devil.

Alma White attracted the attention of the Los Angeles Police Department soon after she arrived in town in spring of 1904 as leader of the Burning Bush movement, a forerunner to the Pillar of Fire. A cacophony of noise emerging from 315 South Olive Street — shouting, shrieking, moaning, and wailing, all set to the incessant thump of a bass drum — announced the arrival of this bizarre new faction. Noise continued day and night and was so loud, neighbors complained they couldn’t even hear the ringing of the steel cables that pulled the nearby Angels Flight funicular up Bunker Hill’s eastern slope. When police officers arrived on May 29, however, no one was willing to swear out a warrant against White and her fellow leaders, who included her husband, “Elder” Kent White, and “Brother” William Edward Shepard. The cult projected an aura of intimidation, and the police had no choice but to let them be.

On the outskirts of the city’s banking district, White and her followers soon raised a revival tent — the kind encountered in rural America — and the din continued unabated. For weeks hundreds of curious Angelenos packed themselves beneath the canvas. In a typical scene, witnessed by a Los Angeles Times reporter, White strutted — one observer likened her clumsy movement to the “gamboling of an elephant” — across a platform that elevated her from the sawdust floor. She singled out a face in the crowd. “Stand up there!” she boomed. “You are the one, I seen you last night. Hey, you fellow over there. I got you spotted, stand up!” A 16-year-old golden-haired boy in blue overalls stepped forward, fell to his knees at the platform, and cried convulsively as men and women placed their hands on his shaking body, shouting “Amen” and “Glory Hallelujah.” The boy wailed with all his lungs for ten minutes, beating his hands on a bench until they were red and bruised. Eventually, he collapsed from exhaustion. Later, as the boy lay unmoving on the sawdust, White’s husband informed the Times reporter matter-of-factly that “it is the spirit of God possessing his soul.”

In his report, the Times journalist suggested that White and the other leaders of her movement were unleashing a form of mass hypnosis. Whispers spread about strange sacrificial rites, in which cult members tossed their cherished possessions into a bonfire. There was even hushed talk of human sacrifice.

By late 1909, White cast her net wider, leading a delegation of 20 missionaries across the Atlantic to London. Soon after, Lily Maud Allen wandered into one of the revival meetings in Bedford Chapel, Camden Town, and heard White preaching. “I knew it was the right thing for me,” the recruit later recalled. After she announced her intention to enlist as a Pillar of Fire missionary, her father forbade it. When she sailed across the Atlantic anyway, she was playing out an already familiar, if dangerous, pattern where dreamers fell under White’s spell, leaving panic and desperation in their wake.

Only a few years earlier, Angelo Vitagliano of Los Angeles had summoned police when his sixteen-year-old daughter Annie disappeared into the Burning Bush. Now, a frantic J. C. Allen drew upon his connections as a prominent London merchant. He cabled the British consul in New York and alerted the American immigration authorities, explaining that his daughter was a minor and ailing from tuberculosis. Allen’s distressed pleas launched a dragnet that mobilized law enforcement agencies on two continents.

When the Los Angeles police got intelligence that the young Englishwoman could be in their jurisdiction, the chief immediately summoned Alice to his office.

“Mrs. Wells,” he said, “here is your first big case.”

“I am ready, chief.”

On this cool, rainy Saturday, Alice stepped up to the cult’s address. She could barely see the building through the dense vegetation that screened the compound from prying eyes. But it was a large lot, and there were rustic remnants of the property’s former life as a family farm: chicken coops, outhouses, grazing cattle. A windmill once towered over the grounds, too, but it burned down shortly after the cult took possession.

As Galloway pinned the badge on her, he made light of the situation. He was “sorry to offer a woman so plain an insignia of office.” When he had “a squad of Amazons, he would ask the police commission to design a star edged with lace ruffles.”

Other men in the department didn’t know how to behave around Alice, either. When she reported to her sergeant, George Curtin, he was sitting in his shirtsleeves — inappropriate in the presence of a lady. Curtin jerked to his feet and shoved his arms into his coat sleeves as Alice approached his desk. “Either you’ll have to get used to this,” he muttered, “or we will.”

Alice prioritized having an office space that provided refuge for women in trouble. The top brass at Central Station apparently could not make room for her — or didn’t want to. Instead, the bailiff offered up his spare courtroom, its shelves stacked with court records, its floor crawling with rats, on the condition that she vacate it whenever it was needed by a judge.

Members of the public also balked at a female police officer. Soon after joining the force, Alice boarded a streetcar and flashed her Los Angeles Police star, numbered 105, to the conductor in lieu of paying a fare. In those days street railways were obligated by law to provide free rides to officers; horses were too messy, and automobiles puttered along too slowly. But the conductor refused to believe the tiny woman standing before him was a plainclothes police officer. Instead, he reprimanded her for stealing her husband’s badge and ordered her off his trolley. Alice quickly hit upon a solution. Soon, she was walking her beat with a new Los Angeles Police star, engraved with the word “Policewoman” to prevent any confusion. Fittingly, the badge bore the number 1.

Staking out the Pillar of Fire headquarters, Alice’s lack of a police uniform helped her. “The less you are known the better chance you have to operate successfully,” she explained to reporters about her approach. “I will have many costumes to be used on different occasions.” For this assignment, she chose a demure outfit.

Alice navigated through the mass of shrubbery to the front porch, and knocked on the door.

When the door to the cult opened, Alice could hear women chanting above the sound of dull pounding. A sharp-featured woman stepped into view.

“What do you want?” she barked.

She told the woman she was in search of “the truth,” that she wanted to join the Pillar of Fire and needed to learn more about it.

The woman studied Alice with piercing blue eyes. Several moments passed before she pressed a button on the wall by the door. The strange noises inside ceased. Alice was invited in.

Inside, the curtains were drawn and the room shrouded in darkness, except for one corner where the sunlight snuck in. The woman, taking a seat in the darkened part of the room, motioned for Alice to sit in the light.

Soon the other residents of the house emerged; as many as ten men and women shared this old farmhouse. They started into their hymns, most of which were written by Alma White herself: compositions such as “Soon I Shall Be Bloodwashed” and “The Cry of the Soul.” Alice found the hymns, whose lyrics often evoked fountains of blood, “outlandish,” but she sang along anyway.

Some thro’ the waters, some thro’ the flood, Some thro’ the fire, but all thro’ the Blood.

Alice stood firm in her mission to avoid violent confrontation. She succeeded in persuading the followers that she was ready to join. In order to undermine Alma White, Alice embraced the part of disciple. But there was no sign of Lily Maud Allen among the chanting followers, nor in any of the chambers Alice entered.

The Jumpers served Alma White through fear, but they came to engage Alice with a different feeling: trust. By the end of that night inside the cult’s hive, Alice convinced a member to divulge Allen’s whereabouts at an 81-acre Pillar of Fire compound near Bound Brook, New Jersey. There, on a strip of land along the Delaware and Raritan Canal, some 125 members sequestered themselves from the sinful world in gloomy buildings with small windows. Allen was washing dishes and scrubbing floors, simultaneously unhappy and content with her new life. “They give the impression,” the New York Times said of the communal houses, “of being places to discipline people in.” On this campus in the coming years, White would permit burning crosses, host a Klan meeting, and set off a riot.

Alice said her goodbyes and rushed to notify the chief, who passed along word to Allen’s desperate father and the New Jersey police.

Alice’s breakthrough detective work won respect from a group that had treated her as an object of curiosity: the press. The Los Angeles Herald celebrated its policewoman locating someone “for whom sleuths of two continents searched.” The Daily Oklahoman’s headline touted a “Clever Ruse to Find Lost Girl,” and newspapers in Boston, Baltimore, Colorado Springs, and Detroit added endorsements.

As for Lily Maud Allen, in spite of Alice’s triumph, the Englishwoman ultimately remained with the Holy Jumpers. It turned out White’s camp had a secret at their disposal. Allen was not seventeen, as her father claimed. He had lied about her being a minor to spread alarm. She was actually twenty-six, and could not be removed against her will. She resurfaced some two years later in Washington, DC, as a Pillar of Fire missionary, supporting Alma White’s announcement of the Second Coming of Christ. Alice may have triumphed in the battle to track down young Allen, but White’s war was far from over.

Alice, too, had just begun, a long road of breakthroughs and challenges awaiting her. The Pillar case cemented confidence in Alice from her newest booster, Chief Sebastian. The thirty-seven-year old had cut his teeth in farming and as a streetcar conductor before entering police work, and he had no trouble embracing practical, outside-the-box thinking. That November, he paid the ultimate compliment to Alice. He made his first formal request for additional policewomen. The police commission granted it — as well as several subsequent requests. By the end of 1912, the Los Angeles Police Department passed a remarkable milestone by boasting four women officers.

In 1913, the police chief traveled to Washington, DC, to make a forceful case to his most skeptical audience: his peers. At the convention, he declared that the experiment Alice had launched three years prior had succeeded. “[Policewomen’s] worth has passed the experimental stage, and I would not, if I could, dispense with their services.” Crime abated citywide. Policewomen, per capita, were making more arrests than policemen.

Within a few more years, Los Angeles made pay for policemen and policewoman uniform, sending Alice home every month with the same $120 as her male peers.

In New Orleans, a brawny, 6’2” man who worked in the city clerk’s office approached Alice. He pleaded for a favor.

“I want to be arrested by a lady.” ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/pillars-of-fire-truly-adventurous?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

Women had to fight a hard struggle to gain basic human rights. The astonishing thing is that the struggle continues, and women are still fighting for their basic rights, encountering some of the same medieval mentality — for instance, if a woman gets pregnant because of rape, that’s obviously god’s will, and she must bear the rapist’s child. During her fertile years, she doesn’t even own her body.

Several years before Obama's presidency, I predicted that we'll have a black president a lot sooner than a woman president. I'm not sure that I'll live long enough to see a woman president. This seems to be the most ingrained of all bigotries. And the funny thing is that one could argue the opposite: that it's men who are not fit to be president. They are too emotional.

Mary: WE ARE STILL FIGHTING THE SAME BATTLE

We look at the story of the first woman police officer, and realize that we are still fighting the same battle for basic human rights, that her "win" for women's rights was not a permanent one. We are fighting the same battle over and over again, now in the most basic arena of all, the right to control your own body. It's quite possible the hard won battle for abortion rights will be reversed, and we'll be pushed back to the dark ages on this, like people rewarded for denouncing witches, what these lawmakers are proposing rewards for those who denounce any woman seeking or obtaining an abortion, and denouncing anyone who helped her do this. This feels like nothing less than a new kind of state sponsored witch hunt. So here we are repeating medieval stories again. Maybe not as a failure of imagination, but a failure to progress, to move beyond the worst ideas and acts of human history — a failure to allow for freedom and equality for all human beings.

Oriana:

The bigotry against women seems the deepest of them all. Sometimes I can't help but despair. After all, it's already been shown that the country is "ready" for a black president — but for a woman president? Sooner a gay man, I suspect.

What the suffragists showed us is that persisting in the battle makes sense after all. Women have won the vote, and there isn't (so far) an open proposal to take the vote away from them. It took not just marches and speeches, but going to jail and hunger strikes . . . But to let a woman own her own body, now that's too radical by far . . .

*

LAWS OF LINGUISTICS THAT APPLY TO MANY FIELDS

~ Linguists have known for quite some time that certain “laws” seem to govern human speech. For instance, across languages, shorter words tend to be more frequently used than longer words. Biologists have taken notice, and many have wondered if these “linguistic laws” also apply to biological phenomena. Indeed, they do, and a new review published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution elaborates on their discoveries.

PATTERN 1: BEING TWICE AS BIG AS THE NEAREST RIVAL

The first linguistic rule concerns the frequency of the most used words in a language. It is known as “Zipf’s rank-frequency law”, and it maintains that “the relative frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its frequency rank.” In other words, the most frequently used word will be twice as common as the second most frequent word, three times as common as the third most frequent, and so on. For instance, in English, “the” is the most common, making up seven percent of all the words we use. The next common is “of,” which is roughly 3.5 percent.

The incredible thing is that this law applies also to a whole range of non-linguistic things. It is seen in the size of proteins and DNA structures. It is seen in most of the noises animals use to communicate, as well as primate gestures. It is found in the relative abundance of plant and animal species. In your garden, the flora and fauna very likely will be distributed by Zipf’s rank-frequency law.

Recently, it has been observed in COVID infection rates, where the largest outbreaks (if there are similar demographics across a country) will be double the size of the next largest region. The law is so reliable that it is being used to call out countries who are doctoring their COVID infection numbers.

PATTERN 2: SMALLER THINGS ARE MORE COMMON

The second linguistic rule we can apply to life is known as “Zipf’s law of abbreviation,” which “describes the tendency of more frequently used words to be shorter.” It is true across hundreds of diverse and unrelated languages, including sign. In English, the top seven most common words are all three letters or fewer, and in the top 100, there are only two words (“people” and “because”) that are more than five letters. The words we use most regularly are short and to the point.

It is also a law seen all over nature. Communication among birds and mammals tend to be short. Indeed, it is seen in the songs of black-capped chickadees, call duration of Formosan macaques, vocalizations of indri, gesture time of chimpanzees, and length of surface behavioral patterns in dolphins. Apparently, it is not just humans who want their language to be efficient.

The law appears in ecology, as well: the most numerous species tend to be the smallest. There are many, many more flies and rats in New York City than there are humans.

PATTERN 3: THE LONGER SOMETHING IS, THE SHORTER ITS COMPONENT PARTS

Let’s take a sentence, like this one, with all its words, long and short, strung together, punctuated by commas, nestled in with each other, to reach a final (and breathless) finale. What you should notice is that although the sentence is long, it is divided into pretty small clauses. This is known as “Menzerath’s law,” in which there is “a negative relationship between the size of the whole and the size of the constituent part.” It is seen not only in sentence construction; the law applies to the short phonemes and syllables found in long words. “Hippopotamus” is divided into lots of short syllables (that is, each syllable has only a few letters), while, ironically, the word “short” constitutes one giant syllable.

As with the previous laws, it is observed in most languages but is perhaps not as widespread. There are several counterexamples, but not nearly enough to discredit the general principle. In nature, it is well documented. In molecular biology, we see “negative relationship[s] between exon number and size in genes, domain number and size in proteins, segment number and size in RNA, and chromosome number and size in genomes.” but also on a macrobiological scale. But, just as with humans, Menzerath’s law is not nearly as common as Zipf’s.

In ecological terms, the more species you find in any given locale, the smaller they all tend to be. So, if a square mile of rain forest contains hundreds or thousands of species, then they all will tend to be much smaller than, say, a square mile of a city.

LINGUISTIC LAWS IN BIOLOGY AND BEYOND

While the paper focuses largely on these three laws, it hints at others that might yet be found (ones which are, as yet, understudied and underexplored). For instance, “Herdan’s law” (a correlation between the number of unique words and the length of a text) is seen in the proteomes of many organisms, and “Zipf’s meaning-frequency law” (in which more common words have more meanings) is seen in primate gestures.

The sheer scale of how applicable and versatile these laws are is remarkable. Laws that were discovered in linguistics have applications in ecology, microbiology, epidemiology, demographics, and geography.

https://bigthink.com/life/linguistic-laws-biology/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR13wMpUhGZGTTXG0Z5WS99-seiW1476CqYkf4lmSQcBtvk_fEDCte8GhlI#Echobox=1634932870

Mary:

That the patterns found in languages are also found in many other places, in biology, in the structures of atoms and cells, is a matter for wonder, but does not really surprise me. It seems to me order is inherent in matter itself, order and design, the patterns we see everywhere, are determined by the order of atoms and their structure. That is the beauty of the periodic table, that matter is ordered in the mathematics of neutrons and electrons, and that numbering is the definition of each element and how and if it will react with other atoms. This order was not imposed, but discovered.

And I think this order is also part of the argument against entropy...that things do not just decay into chaos but actually interact to become more organized, more coherent, to form molecules, then structures more complex, up to the structures and organs that are living creatures, from single to multi-cellular, multi-cellular to multi-systemic. These changes are mathematical, can be described in mathematics, and are constrained by the mathematics of structure, determined by the electrons number and position in the atoms of each element.

In language, iconicity, the connection between the word/sound and its meaning, I think can possibly be related to the shape the mouth and tongue make in the pronunciation, as well as the duration, and sharpness or softness of the sounds. Most obvious in the one example given of "bouba" and "kiki." Most vocabulary may be arbitrary, but maybe some very basic words are rooted in this mouth/shape/sound...for instance "mama" in all its variations in many languages.

*

BUDDHISM AND SELF-CONTROL

One day Buddha was walking through a village. A very angry and rude young man came up to him and began insulting him.

"You have no right to be teaching others!!!" he shouted.

"You are as stupid as everyone else. You are nothing but a fake!!”

Buddha was not upset by these insults. He just smiled. The man insulted him again and again but the only reaction he could get back from the Buddha was a smile and silence. Finally he stomped his feet and left cursing.

The disciples were feeling angry and one of the them couldn’t keep quiet and asked the Buddha, “Why didn’t you reply to the rude man?”

The Buddha replied, “If someone offers you a gift, and you refuse to accept it, to whom does the gift belong?”

“Of course to the person who brought the gift,” replied the disciple. “That is correct,” smiled the Buddha.

*

BUT SOME ACTIONS ARE BEYOND CONTROL: WHY DARWIN JUMPED

"At one point of his career, Darwin wanted to test his survival reactions and see if he could control them in the face of danger. He undoubtedly asked himself, “Just how strong are my survival instincts? Can my modern brain take charge?” He went to the reptile house at the London Zoo and put his face against the glass cage containing a puff adder, a highly venomous African snake, intending to provoke the snake into trying to bite him. He was determined, he wrote in his diary, not to flinch or move.

Suddenly the snake lunged at him, hitting the glass barrier. Darwin described his reaction: “. . . as soon as the blow was struck, my resolution went for nothing, and I jumped a yard or two backwards with astonishing rapidity.”

It made no difference, he wrote, knowing that the snake could not reach him through the glass. His thoughts were powerless; instinct propelled him with “. . . An imagination of a danger which [he] had never experienced.”

The snake’s attempt to bite Darwin launched a primitive reaction beginning with visual stimuli registering the snake’s movement and ending with a message to the brain’s AMYGDALA. The result was Darwin jumping or, put another way, survival behavior. The cortex had no role in the reaction. Darwin could not control the reflex, even though the glass between him and the snake meant the danger was not genuine. His instinctive jump backward was automatic, happening without thought or awareness of what he was doing.”

~ Theodore George, M.D., “Darwin Tries to Outwit His Amygdala,” in “Untangling the Mind: Why We Behave the Way We Do”

Oriana:

I wish this book were more lively since it deals with important issues: subcortical reactions and the mayhem they may produce due to irrational fear and/or anger. T. George also discusses the brain's reward system, addiction, psychopathy, and depression (“shut-down”).

puffer adder

Oriana:

No, you can’t outwit your amygdala when it comes to survival responses. Nor should we feel guilty about it. But there are many situation (such as being insulted by a verbal bully) when the cortex can be trained to take over — when we don’t have to “react” but, in Buddhist terms, we can just “witness.”

But not if you see someone (or an animal) in the slightly crouched position, about to lunge forward and attack. Fortunately we don’t have to think; our amygdala will make us jump back. But even so, a training in martial arts relies on the unexpected: when being pushed, don’t push back — pull.

*

ICONIC COMMUNICATION AND THE ORIGIN OF LANGUAGE

~ Language gives us the power to describe, virtually without limit, the countless entities, actions, properties and relations that compose our experience, real and imagined. But what is the origin of this power? What gave rise to humankind’s ability to use words to convey meanings?

Traditionally, scholars interested in this question have focused on trying to explain language as an arbitrary symbolic code. If you take an introductory course in linguistics, you are certain to learn the foundational doctrine known as ‘the arbitrariness of the sign’, laid out in the early 20th century by the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. This principle states that words are meaningful simply as a matter of convention. As the psychologists Steven Pinker and Paul Bloom have explained it: ‘There is no reason for you to call a dog dog rather than cat except for the fact that everyone else is doing it.’ The corollary of arbitrariness is that the forms of words do not bear any resemblance to their meaning; that is, they are not iconic. ‘The word “salt” is not salty nor granular; “dog” is not “canine”; “whale” is a small word for a large object; “microorganism” is the reverse,’ observed the linguist Charles Hockett in his classic article ‘The Origins of Speech’ (1960).

But this raises a conundrum – what is known in philosophy as ‘the symbol grounding problem’. If words are arbitrary and purely a matter of convention, then how did they come to be established in the first place? In practical terms: how did our ancestors create the original words? This is a challenging question to answer. Scientists have little direct knowledge of the prehistoric origins of today’s approximately 7,000 spoken languages, at least tens of thousands of years ago. We do, however, know an increasing amount about how people create and develop new sign languages.

Sign languages – which are articulated primarily by visible gestures of the hands, body and face – turn out to be far more common than previously realized, with a roughly estimated 200 such languages used by Deaf and hearing people around the globe. Crucially, sign languages are, absolutely, languages, every bit as complex and expressive as their spoken counterparts. And sign languages are much younger than spoken languages, just a few hundred years old at most, making their origins more transparent. Indeed, within just the past few decades, scientists have actually observed the early formation of entirely new sign languages – a process that happens spontaneously when Deaf people who are deprived of a sign language have the opportunity to live together and communicate freely with each other.

So how do they do it? How do Deaf people first establish a shared set of meaningful signs? Their solution is an intuitive one. Without access to a sign language, Deaf people communicate in essentially the same way that people do when they travel to a place where they don’t speak any of the local languages, or when they play a game of ‘charades’. Tasked to communicate without words, the human strategy is universal: we act out our meaning, pantomiming actions and using our hands and bodies to depict the sizes, shapes and spatial relationships of referents. The first signers of the Nicaraguan Sign Language, for example, appear to have established the sign for ‘watermelon’ by first pantomiming the action of holding and eating a slice of the fruit, and then the action of spitting out a seed, using their index finger to trace its imaginary path from the signer’s mouth to the ground. Once understanding is achieved – a recognizable mapping between form and meaning – signers can turn a pantomime into a conventional symbol that is shared within their community.

Key to this process of forming new symbols is the use of iconicity – the creation of signs that are intrinsically meaningful because they somehow resemble what they are intended to mean. Iconicity, that connection between form and meaning, is a powerful force for communication, enabling people to understand each other across linguistic divides. Notably, iconicity is not limited to gesturing; it pervades our graphic communication too. Traffic signs, food packaging, emojis, instruction manuals, maps… wherever there are people communicating, you will find iconicity. What’s more, the ability to create and understand iconicity appears to be a distinctly human capability. There is scant evidence of iconic symbol formation in the communication of other animals. (Although there are some illuminating exceptions in language-trained and human-enculturated apes such as the gorilla Koko and the chimpanzee Viki.)

These facts regarding the ubiquity and the uniqueness of iconicity in human communication might seem at odds with the reigning theory that speech is an arbitrary code that is characteristically lacking in iconicity. That the sounds we produce do not resemble what they mean. How could it be that iconicity is such a defining feature of human expression, except when we speak? A common (and, as we will see, wrong) explanation for this is that the voice does not offer the potential for iconicity that exists in visual media such as gesture and drawing. The idea is that our voices might be able to connect form and meaning in limited instances – say, imitating an animal’s sound to refer to the animal – but that for wider iconic representations of our experience, our voices are mostly useless.

As it turns out, this idea had, until recently, never been put to rigorous scientific test. However, a series of studies by my collaborators and me show that, in fact, iconic vocalizations can be a powerful way for people to communicate when they lack a common language. This could help explain how the forms of spoken words were first devised.

Our investigation began with a contest in which we invited the contestants to record a set of vocal sounds to communicate 30 different meanings. These included an array of concepts that might have been relevant to the lives of our paleolithic ancestors: living entities such as ‘child’ and ‘deer’, objects like ‘knife’ and ‘fruit’, actions like ‘cook’ and ‘hide’, properties like ‘dull’ and ‘big’, as well as the quantifiers ‘one’ and ‘many’ and the demonstratives ‘this’ and ‘that’. The winner of the contest was determined by how well listeners could guess the intended meanings of the sounds based on a set of written options. Critically, the sounds that contestants submitted had to be non-linguistic – no actual words were allowed, a rule that also excluded conventional onomatopoeias. And although contestants might have imitated animal sounds in a few instances (growling for ‘tiger’ or hissing for ‘snake’), such direct vocal imitations were not obvious for most of the items.

Listeners were remarkably good at interpreting the meanings of the sounds – significantly better than chance for each of the meanings we tested. Yet, this study had a limitation: all of the contestants and listeners were speakers of English. Thus, it was possible that listeners’ success relied on some cultural knowledge that they shared with the vocalizers. The crucial test would require that we determine whether the vocalizations were also understandable to listeners from completely different cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

That was our next step. In a follow-up study, our international team of linguists and psychologists tested the vocalizations with listeners from around the world in two different comprehension experiments. The first involved an internet survey translated into 25 different languages. In this experiment, participants listened to each vocalization from the English speakers and guessed the meaning, choosing from among six written words. Guessing accuracy for the different groups ranged from 74 per cent for English speakers to 52 per cent for Thai speakers – well above the chance rate of 17 per cent. In a second experiment, we tested the vocalizations with populations living in predominantly oral societies, including, for example, Portuguese speakers living in the Amazon forest of Brazil and Daakie speakers in a village in the South Pacific island country of Vanuatu. Participants responded by pointing at one of a set of 12 printed images. Here, the Portuguese speakers registered 34 per cent accuracy and Daakie speakers 43 per cent. Far from perfect, but well above the chance rate of 8 per cent. Thus, findings from both experiments showed that, no matter what language they spoke, participants were able to interpret the vocalizations with a notable degree of accuracy.

Remarkably, people are also able to use their voices to communicate about things that ostensibly have nothing to do with sound. In our online survey, we also tested the well-documented ‘bouba/kiki effect’. Participants listened to recordings of someone saying one of two made-up words, either ‘bouba’ or ‘kiki’, as they viewed two shapes side by side, one rounded and one pointy. After listening to each word, they selected which of the shapes they thought better matched the sound of the word. You can probably guess the results: the great majority of participants around the world matched ‘bouba’ with the rounded shape and ‘kiki’ with the pointy one. There is, apparently, a widely recognizable resemblance between the sounds of these words and the corresponding shapes.

Taken together, these studies show that, just like in gesture and drawing, there is considerable potential for iconicity in vocalization after all. Modern words might look arbitrary through the lens of classic linguistic analysis, their origins obscured by many thousands of years of historical development. But dig far enough back in time and there is at least a possibility that the forms of many spoken words began – like the symbols of sign languages – as iconic representations of their meanings. (Indeed, we don’t need to look back into prehistory: linguists are documenting widespread evidence of iconicity in modern spoken languages, too.)

This route to the formation of new spoken words is still active today. Consider the recently coined English word cheugy – widely used by TikTokers – which, according to Urban Dictionary, means ‘The opposite of trendy’. Credited with creating the new word, Gaby Rasson explained to The New York Times: ‘It was a category that didn’t exist … There was a missing word that was on the edge of my tongue and nothing to describe it and “cheugy” came to me. How it sounded fit the meaning.’ It is possible that many thousands of years ago our ancestors did something very similar when they created the first spoken words.

Turning back to the question of what gave rise to our unique ability for linguistic communication: although the complete answer is undoubtedly complex, scientific findings suggest that our capacity for iconic communication has played a critical role. Whether it is with gesture, drawing or the sound of our voice, humans are virtuosos at the game of charades. Without this special talent, language – that vastly flexible symbolic system capable of expressing just about anything – would likely never have gotten off the ground. ~

https://psyche.co/ideas/humans-gift-for-charades-helps-explain-the-origin-of-language

definitely "kiki"

*

THE CITY AND MENTAL HEALTH

~ Back in the 1930s, two sociologists noticed a striking pattern amongst the people being admitted to Chicago’s asylums. Rates of schizophrenia, they reported, were unusually high in those born to inner-city neighborhoods. Since then, researchers have discovered that mental illnesses of all kinds are more common in densely populated cities than in greener and more rural areas. In fact, the Center for Urban Design and Mental Health estimates that city dwellers face a nearly 40 percent higher risk of depression, 20 percent higher chance of anxiety, and double the risk of schizophrenia than people living in rural areas.

Some of the burden on city dwellers’ mental health can be traced to social problems such as loneliness and the stress of living cheek-by-jowl with thousands or even millions of other people. But there’s something about the physical nature of cities that also seems to put a strain on the emotional wellbeing of their inhabitants. City life means dealing with stressors like air and noise pollution stemming from traffic, construction, or your neighbors. However, it’s only in recent years that scientists have begun to seriously study the mechanisms through which exposure to various environmental stressors could be wounding our mental health, says Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg, director of the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany. “It’s an emerging field,” he says.

A key part of improving our collective mental health will be making our cities more livable, says Meyer-Lindenberg. He and van den Bosch published their findings in 2019 in the journal Annual Review of Public Health. More than half the world’s population already lives in cities and this number is expected to rise to nearly 70 percent by 2050.

In their review, Meyer-Lindenberg and van den Bosch found that some potential threats had been examined more thoroughly than others. For some, including pollen, there wasn’t enough information yet to show a convincing link to depression. However, the team did find a number of studies suggesting that heavy metals like lead, pesticides, common chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA), and noise pollution may contribute to depression, although further research is still needed to confirm that this is the case.

Even more compelling was the evidence condemning air pollution. In addition to causing respiratory and cardiovascular problems that kill millions of people each year, this particular menace raises our risk for a number of psychiatric problems. Poor air quality has been associated with depression, anxiety, and psychotic experiences such as paranoia and hearing voices.