All I can tell you is that it’s a banana flower. The rest of this surreal visual poem is up to you, gentle reader.

*

LOT’S WIFE

They took away my name

that was the real punishment

not the thick grains of salt

that sealed my lips and eyes

but black letters that caw

Lot’s wife

My name died with those

not elected for mercy

my name that soft breeze

a twig brushing the wrist

We ran in a rain of fire

boulders shuddered and split

in a drumroll of thunder

hiss of the burned river

a cry of bones

only I obeyed

the human

commandment

only I

turned around and saw

the keepers of the story

took away my name

so I’d be nobody a woman

who once turned around

instead of staring

at her husband’s back

I stand as I was written

blind

but having seen

whose name you

do not know

~ Oriana

Mary:

*

A SMALL ASTEROID MAY HAVE DESTROYED SODOM

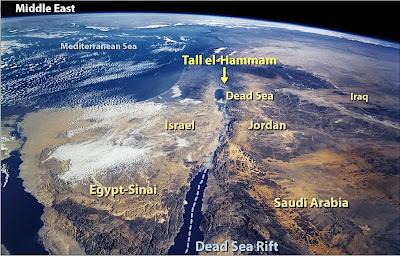

~ As the inhabitants of an ancient Middle Eastern city now called Tall el-Hammam went about their daily business one day about 3,600 years ago, they had no idea an unseen icy space rock was speeding toward them at about 38,000 mph (61,000 kph).

Flashing through the atmosphere, the rock exploded in a massive fireball about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) above the ground. The blast was around 1,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The shocked city dwellers who stared at it were blinded instantly. Air temperatures rapidly rose above 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (2,000 degrees Celsius). Clothing and wood immediately burst into flames. Swords, spears, mudbricks and pottery began to melt. Almost immediately, the entire city was on fire.

Some seconds later, a massive shockwave smashed into the city. Moving at about 740 mph (1,200 kph), it was more powerful than the worst tornado ever recorded. The deadly winds ripped through the city, demolishing every building. They sheared off the top 40 feet (12 m) of the 4-story palace and blew the jumbled debris into the next valley. None of the 8,000 people or any animals within the city survived – their bodies were torn apart and their bones blasted into small fragments.

About a minute later, 14 miles (22 km) to the west of Tall el-Hammam, winds from the blast hit the biblical city of Jericho. Jericho’s walls came tumbling down and the city burned to the ground.

How do we know that all of this actually happened near the Dead Sea in Jordan millennia ago?

Getting answers required nearly 15 years of painstaking excavations by hundreds of people. It also involved detailed analyses of excavated material by more than two dozen scientists in 10 states in the U.S., as well as Canada and the Czech Republic. When our group finally published the evidence recently in the journal Scientific Reports, the 21 co-authors included archaeologists, geologists, geochemists, geomorphologists, mineralogists, paleobotanists, sedimentologists, cosmic-impact experts and medical doctors.

Here’s how we built up this picture of devastation in the past.

FIRESTORMS THROUGHOUT THE CITY

Years ago, when archaeologists looked out over excavations of the ruined city, they could see a dark, roughly 5-foot-thick (1.5 m) jumbled layer of charcoal, ash, melted mudbricks and melted pottery. It was obvious that an intense firestorm had destroyed this city long ago. This dark band came to be called the destruction layer.

No one was exactly sure what had happened, but that layer wasn’t caused by a volcano, earthquake or warfare. None of them are capable of melting metal, mudbricks and pottery.

To figure out what could, our group used the Online Impact Calculator to model scenarios that fit the evidence. Built by impact experts, this calculator allows researchers to estimate the many details of a cosmic impact event, based on known impact events and nuclear detonations.

It appears that the culprit at Tall el-Hammam was a small asteroid similar to the one that knocked down 80 million trees in Tunguska, Russia in 1908. It would have been a much smaller version of the giant miles-wide rock that pushed the dinosaurs into extinction 65 million ago.

We had a likely culprit. Now we needed proof of what happened that day at Tall el-Hammam.

“DIAMONDS” IN THE DIRT

At the site, there are finely fractured sand grains called shocked quartz that only form at 725,000 pounds per square inch of pressure (5 gigapascals) – imagine six 68-ton Abrams military tanks stacked on your thumb.

The destruction layer also contains tiny diamonoids that, as the name indicates, are as hard as diamonds. Each one is smaller than a flu virus. It appears that wood and plants in the area were instantly turned into this diamond-like material by the fireball’s high pressures and temperatures.

Experiments with laboratory furnaces showed that the bubbled pottery and mudbricks at Tall el-Hammam liquefied at temperatures above 2,700 F (1,500 C). That’s hot enough to melt an automobile within minutes.

The destruction layer also contains tiny balls of melted material smaller than airborne dust particles. Called spherules, they are made of vaporized iron and sand that melted at about 2,900 F (1,590 C).

In addition, the surfaces of the pottery and meltglass are speckled with tiny melted metallic grains, including iridium with a melting point of 4,435 F (2,466 C), platinum that melts at 3,215 F (1,768 C) and zirconium silicate at 2,800 F (1,540 C).

Together, all this evidence shows that temperatures in the city rose higher than those of volcanoes, warfare and normal city fires. The only natural process left is a cosmic impact.

The same evidence is found at known impact sites, such as Tunguska and the Chicxulub crater, created by the asteroid that triggered the dinosaur extinction.

One remaining puzzle is why the city and over 100 other area settlements were abandoned for several centuries after this devastation. It may be that high levels of salt deposited during the impact event made it impossible to grow crops. We’re not certain yet, but we think the explosion may have vaporized or splashed toxic levels of Dead Sea salt water across the valley. Without crops, no one could live in the valley for up to 600 years, until the minimal rainfall in this desert-like climate washed the salt out of the fields.

WAS THERE A SURVIVING EYEWITNESS OF THE BLAST?

It’s possible that an oral description of the city’s destruction may have been handed down for generations until it was recorded as the story of Biblical Sodom. The Bible describes the devastation of an urban center near the Dead Sea – stones and fire fell from the sky, more than one city was destroyed, thick smoke rose from the fires and city inhabitants were killed.

Could this be an ancient eyewitness account? If so, the destruction of Tall el-Hammam may be the second-oldest destruction of a human settlement by a cosmic impact event, after the village of Abu Hureyra in Syria about 12,800 years ago. Importantly, it may the first written record of such a catastrophic event.

The scary thing is, it almost certainly won’t be the last time a human city meets this fate.

Tunguska-sized airbursts, such as the one that occurred at Tall el-Hammam, can devastate entire cities and regions, and they pose a severe modern-day hazard. As of September 2021, there are more than 26,000 known near-Earth asteroids and a hundred short-period near-Earth comets. One will inevitably crash into the Earth. Millions more remain undetected, and some may be headed toward the Earth now.

Unless orbiting or ground-based telescopes detect these rogue objects, the world may have no warning, just like the people of Tall el-Hammam. ~

"Earth is protected by a thick atmosphere, the equivalent of 10 meters (30 feet) of seawater. This layer causes small incoming rocks to explode in the atmosphere high above ground and pose no serious threat. These are the meteors or "shooting stars" that we see at night. Asteroid impacts larger than 10 meters (30 feet, 10 kiloton explosion) are much less frequent, arriving once every few years and may sometimes punch down to the ground. The meteor, which exploded above Chelyabinsk, Russia on February 15, 2013, for example, was estimated to be about 15 meters (50 feet) diameter. The explosion in the atmosphere was equivalent to about 440 kilotons TNT. Still larger asteroids are much more dangerous." https://atlas.fallingstar.com/danger.php

*

SUSAN SONTAG: “MY LIFE IS A BRUTAL ANECDOTE”

~ Among the memorable stories in Benjamin Moser’s engrossing, unsettling biography of Susan Sontag, an observation by the writer Jamaica Kincaid stands out indelibly. In 1982, Sontag’s beloved thirty-year-old son David Rieff endured a number of major crises: cocaine addiction, job loss, romantic break-up, cancer scare and nervous breakdown. At that point, Moser writes, Sontag “scampered off to Italy” with her new lover, the dancer and choreographer Lucinda Childs. “We couldn’t really believe she was getting on the plane”, Kincaid told Moser. She and her husband Allen Shawn took David into their home for six months to recover. Later she searched for words to characterize Sontag’s behavior: “Yes, she was cruel, and so on, but she was also very kind. She was just a great person. I don’t think I ever wanted to be a great person after I met Susan”.

In 2013, when Moser signed up to write Sontag’s authorized biography, he took on a hazardous task: how to recount the eventful life, influential ideas and significant achievements of a legendary public intellectual, and assess the overall legacy of an outrageous, infuriating great person? He was not the first to face these challenges. “Disappointment with her…”, he notes, “is a prominent theme in memoirs of Sontag.” She was avid, ardent, driven, generous, narcissistic, Olympian, obtuse, maddening, sometimes lovable but not very likable. Moser has had the confidence and erudition to bring all these contradictory aspects together in a biography fully commensurate with the scale of his subject. He is also a gifted, compassionate writer. ~

(here I hit a paywall by Times Literary Supplement, https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/susan-sontag-life-benjamin-moser/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR280Kv-6DGe3xuRn1zqy911kNogKNP1cVqGNMJVdCpBCCRNd162yurR5vA#Echobox=1633355382 — so let me continue with a different source, The New Yorker)

~ Two volumes of Susan Sontag’s diaries, edited by her son, David Rieff, have been published, and a third is forthcoming. In the preface to the first volume, published in 2008, under the title “Reborn,” Rieff confesses his uncertainty about the project. He reports that at the time of her death, in 2004, Sontag had given no instructions about the dozens of notebooks that she had been filling with her private thoughts since adolescence and which she kept in a closet in her bedroom. “Left to my own devices,” he writes, “I would have waited a long time before publishing them, or perhaps never published them at all.” But because Sontag had sold her papers to the University of California at Los Angeles, and access to them was largely unrestricted, “either I would organize them and present them or someone else would,” so “it seemed better to go forward.” However, he writes, “my misgivings remain. To say that these diaries are self-revelatory is a drastic understatement.”

In them, Sontag beats up on herself for just about everything it is possible to beat up on oneself for short of murder. She lies, she cheats, she betrays confidences, she pathetically seeks the approval of others, she fears others, she talks too much, she smiles too much, she is unlovable, she doesn’t bathe often enough. In February, 1960, she lists “all the things that I despise in myself . . . being a moral coward, being a liar, being indiscreet about myself + others, being a phony, being passive.” In August, 1966, she writes of “a chronic nausea—after I’m with people. The awareness (after-awareness) of how programmed I am, how insincere, how frightened.” In February, 1960, she writes, “How many times have I told people that Pearl Kazin was a major girlfriend of Dylan Thomas? That Norman Mailer has orgies? That Matthiessen was queer. All public knowledge, to be sure, but who the hell am I to go advertising other people’s sexual habits? How many times have I reviled myself for that, which is only a little less offensive than my habit of name-dropping (how many times did I talk about Allen Ginsberg last year, while I was on Commentary?).”

The world received the diaries calmly enough; there is not a big readership for published diaries. It will be interesting to see whether Benjamin Moser’s authorized biography, “Sontag: Her Life and Work” (Ecco), which draws heavily on the diaries, makes more of a stir. Moser takes Sontag at her word and is as unillusioned about her as she is about herself. The solid literary achievement and spectacular worldly success that we associate with Sontag was, in Moser’s telling, always shadowed by abject fear and insecurity, increasingly accompanied by the unattractive behavior that fear and insecurity engender. The dauntingly erudite, strikingly handsome woman who became a star of the New York intelligentsia when barely thirty, after publishing the essay “Notes on Camp,” and who went on to produce book after book of advanced criticism and fiction, is brought low in this biography. She emerges from it as a person more to be pitied than envied.

“I loved Susan,” Leon Wieseltier said. “But I didn’t like her.” He was, Moser writes, speaking for many others. Roger Deutsch, another friend, reported, “If somebody like Jackie Onassis put in $2,000”—for a fund to help Sontag when she was ill and had no insurance—“Susan would say, ‘That woman is so rich. Jackie Onassis. Who does she think she is?’ ”

Coming out is at issue, in fact. The occasion is Sontag’s thrillingly good essay “Fascinating Fascism,” published in The New York Review of Books in 1975 and reprinted in the book “Under the Sign of Saturn,” in which she justly destroyed Leni Riefenstahl’s newly restored reputation, showing her to be a Nazi sympathizer in every bone. After giving the essay its due, Moser suddenly swerves to the side of the poet Adrienne Rich, who wrote a letter to the Review protesting Sontag’s en-passant attribution of Riefenstahl’s rehabilitation to feminists who “would feel a pang at having to sacrifice the one woman who made films that everybody acknowledges to be firstrate.” Moser holds up Rich as “an intellectual of the first rank” who had “written essays in no way inferior to Sontag’s” and as an exemplar of what Sontag might have been if she had had the guts. At a time when homosexuality was still being criminalized, Rich had acknowledged her lesbianism, while Sontag was silent about hers. Rich had been punished for her bravery (“by coming out publicly, [she] bought herself a ticket to Siberia—or at least away from the patriarchal world of New York culture”), while Sontag had been rewarded for her cowardice.

Later in the book, Moser can barely contain his rage at Sontag for not coming out during the AIDS crisis. “There was much she could have done, and gay activists implored her to do the most basic, most courageous, most principled thing of all,” he writes. “They asked her to say ‘I,’ to say ‘my body’: to come out of the closet.” Moser cannot forgive her for her refusal to do so.

Sontag’s love life was unusual. At fifteen, she wrote in her journal of the “lesbian tendencies” she was finding in herself. The following year, she began sleeping with women and delighting in it. Simultaneously, she wrote of her disgust at the thought of sex with men: “Nothing but humiliation and degradation at the thought of physical relations with a man—The first time I kissed him—a very long kiss—I thought quite distinctly: ‘Is this all?—it’s so silly.’ ”

Less than two years later, as a student at the University of Chicago, she married—a man! He was Philip Rieff, a twenty-nine-year-old professor of sociology, for whom she worked as a research assistant, and to whom she stayed married for eight years. The early years of Sontag’s marriage to Rieff are the least documented of her life, and they’re a little mysterious, leaving much to the imagination. They are what you could call her years in the wilderness, the years before her emergence as the celebrated figure she remained for the rest of her life. She followed Rieff to the places of his academic appointments (among them Boston, where Sontag did graduate work in the Harvard philosophy department), became pregnant and had a then perforce illegal abortion, became pregnant again, and gave birth to her son, David.

There was tremendous intellectual affinity between Sontag and Rieff. “At seventeen I met a thin, heavy-thighed, balding man who talked and talked, snobbishly, bookishly, and called me ‘Sweet.’ After a few days passed, I married him,” she recalled in a journal entry from 1973. By the time of the marriage, in 1951, she had discovered that sex with men wasn’t so bad. Moser cites a document that he found among Sontag’s unpublished papers in which she lists thirty-six people she had slept with between the ages of fourteen and seventeen, and which included men as well as women. Moser also quotes from a manuscript he found in the archive which he believes to be a memoir of the marriage: “They stayed in bed most of the first months of their marriage, making love four or five times a day and in between talking, talking endlessly about art and politics and religion and morals.” The couple did not have many friends, because they “tended to criticize them out of acceptability.”

In addition to her graduate work, and caring for David, Sontag helped Rieff with the book he was writing, which was to become the classic “Freud: The Mind of the Moralist.” She grew increasingly dissatisfied with the marriage. “Philip is an emotional totalitarian,” she wrote in her journal, in March, 1957. One day, she had had enough. She applied for and received a fellowship at Oxford, and left husband and child for a year. After a few months at Oxford, she went to Paris and sought out Harriet Sohmers, who had been her first lover, ten years earlier. For the next four decades, Sontag’s life was punctuated by a series of intense, doomed love affairs with beautiful, remarkable women, among them the dancer Lucinda Childs and the actress and filmmaker Nicole Stéphane. The journals document, sometimes in excruciatingly naked detail, the torment and heartbreak of these liaisons.

If Moser’s feelings about Sontag are mixed—he always seems a little awed as well as irked by her—his dislike for Philip Rieff is undiluted. He writes of him with utter contempt. He mocks his fake upper-class accent and fancy bespoke-looking clothes. He calls him a scam artist. And he drops this bombshell: he claims that Rieff did not write his great book—Sontag did. Moser in no way substantiates his claim. He merely believes that a pretentious creep like Rieff could not have written it. “The book is so excellent in so many ways, so complete a working-out of the themes that marked Susan Sontag’s life, that it is hard to imagine it could be the product of a mind that later produced such meager fruits,” Moser writes.

Sigrid Nunez, in her memoir “Sempre Susan,” contributes what may be the last word on the subject of the authorship of “The Mind of the Moralist”: “Although her name did not appear on the cover, she was a full coauthor, she always said. In fact, she sometimes went further, claiming to have written the entire book herself, ‘every single word of it.’ I took this to be another one of her exaggerations.”

*

Geniuses are often born to parents afflicted with no such abnormality, and Sontag belongs to this group. Her father, Jack Rosenblatt, the son of uneducated immigrants from Galicia, had left school at the age of ten to work as a delivery boy in a New York fur-trading firm. By sixteen, he had worked his way up in the company to a position of responsibility sufficient to send him to China to buy hides. By the time of Susan’s birth, in 1933, he had his own fur business and was regularly traveling to Asia. Mildred, Susan’s mother, who accompanied Jack on these trips, was a vain, beautiful woman who came from a less raw Jewish immigrant family. In 1938, while in China, Jack died, of tuberculosis, leaving Mildred with five-year-old Susan and two-year-old Judith to raise alone. By all reports, she was a terrible mother, a narcissist and a drinker.

Moser’s account is largely derived from Susan’s writings: from entries in her journal and from an autobiographical story called “Project for a Trip to China.” Moser also uses a book called “Adult Children of Alcoholics,” by Janet Geringer Woititz, published in 1983, to explain the darkness of Sontag’s later life. “The child of the alcoholic is plagued by low self-esteem, always feeling, no matter how loudly she is acclaimed, that she is falling short,” he writes. By pushing the child Susan away and at the same time leaning on her for emotional support, Mildred sealed off the possibility of any future lightheartedness. “Indeed, many of the apparently rebarbative aspects of Sontag’s personality are clarified in light of the alcoholic family system, as it was later understood,” Moser writes, and he goes on:

Her enemies, for example, accused her of taking herself too seriously, of being rigid and humorless, of possessing a baffling inability to relinquish control of even the most trivial matters. . . . Parents to their parents, forbidden the carelessness of normal children, they [children of alcoholics] assume an air of premature seriousness. But often, in adulthood, the “exceptionally well behaved” mask slips and reveals an out-of-season child.

In his account of Sontag’s worldly success, Moser shifts to a less baleful register. He rightly identifies Mildred’s remarriage to a man named Nathan Sontag, in 1945, as a seminal event in Susan’s rise to stardom. In an essay from 2005, Wayne Koestenbaum wrote, “At no other writer’s name can I stare entranced for hours on end—only Susan Sontag’s. She lived up to that fabulous appellation.” Would Koestenbaum have stared entranced at the name Susan Rosenblatt? Are any bluntly Jewish appellations fabulous? Although Nathan did not adopt Susan and her sister, Susan eagerly made the change that, as Moser writes, “transformed the gawky syllables of Sue Rosenblatt into the sleek trochees of Susan Sontag.” It was, Moser goes on, one of “the first recorded instances, in a life that would be full of them, of a canny reinvention.”

Sontag would later write in a more accessible, though never plain-speaking, manner. “Illness as Metaphor” (1978), her polemic against the pernicious mythologies that blame people for their illnesses, with tuberculosis and cancer as prime exemplars, was a popular success as well as a significant influence on how we think about the world. Her novel “The Volcano Lover” (1992), a less universally appreciated work, became a momentary best-seller. But in the sixties Sontag struggled to survive as a writer who didn’t teach. A protector was needed, and he appeared on cue. He was Roger Straus, the head of Farrar, Straus, who published both “The Benefactor” and “Against Interpretation” and, Moser writes,

. . . made Susan’s career possible. He published every one of her books. He kept her alive, professionally, financially, and sometimes physically. She was fully aware that she would not have had the life she had if he had not taken her under his protection when he did. In the literary world, their relationship was a source of fascination: of envy for writers who longed for a protector as powerful and loyal; of gossip for everyone who speculated about what the relationship entailed.

“They had sex on several occasions, in hotels. She had no problems telling me that,” Greg Chandler, an assistant of Sontag’s, had no problems telling Moser.

A final protector was the photographer Annie Leibovitz, who became Sontag’s lover in 1989 and, during the fifteen years of their on-again, off-again relationship, gave her “at least” eight million dollars, according to Moser, who cites Leibovitz’s accountant, Rick Kantor. Katie Roiphe, in a remarkable essay on Sontag’s agonizing final year, in her book “The Violet Hour: Great Writers at the End,” pauses to think about the “strange, inconsequential lies” that Sontag told all her life. Among them was the lie she told “about the price of her apartment on Riverside Drive, because she wanted to seem like she was an intellectual who drifted into a lovely apartment and did not spend a lot of money on real estate, like a more bourgeois, ordinary person.” But by the time of Annie Leibovitz’s protectorship her self-image had changed. She was happy to trade in her jeans for silk trousers and her loft apartment for a penthouse.

*

In “Swimming in a Sea of Death,” David Rieff’s brilliant, anguished memoir of Sontag’s last year, he writes of the avidity for life that underlay her specially strong horror of extinction—a horror that impelled her to undergo the extreme sufferings of an almost sure-to-fail bone-marrow transplant rather than accept the death sentence of an untreated (and otherwise untreatable) form of blood cancer called myelodysplastic syndrome. “The simple truth is that my mother could not get enough of being alive. She reveled in being; it was as straightforward as that. No one I have ever known loved life so unambivalently.” And: “It may sound stupid to put it this way, but my mother simply could never get her fill of the world.”

Moser’s biography, for all its pity and antipathy, conveys the extra-largeness of Sontag’s life. She knew more people, did more things, read more, went to more places (all this apart from the enormous amount of writing she produced) than most of the rest of us do. Moser’s anecdotes of the unpleasantness that she allowed herself as she grew older ring true, but recede in significance when viewed against the vast canvas of her lived experience. They are specks on it.

The erudition for which she is known was part of a passion for culture that emerged, like a seedling in a crevice in a rock, during her emotionally and intellectually deprived childhood. How the seedling became the majestic flowering plant of Sontag’s maturity is an inspiring story—though perhaps also a chastening one. How many of us, who did not start out with Sontag’s disadvantages, have taken the opportunity that she pounced on to engage with the world’s best art and thought? While we watch reruns of “Law & Order,” Sontag seemingly read every great book ever written. She seemed to know that the opportunity comes only once. She had preternatural energy (sometimes enhanced by speed). She didn’t like to sleep.

In 1973, Sontag wrote in her journal:

In “life,” I don’t want to be reduced to my work. In “work,” I don’t want to be reduced to my life.

My work is too austere

My life is a brutal anecdote ~

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/23/susan-sontag-and-the-unholy-practice-of-biography

Susan Sontag, 1965; photo by Diane Arbus

Oriana:

I attended one of her readings and admit to being enchanted by Sontag’s persona. She was a beautiful, charismatic woman — though I also agree with whoever called her a Dark Prince. Not a princess, no. A prince, with connotations of more power.

She was fascinated with style. “Fascinating Fascism” is my favorite essay.

And next to her brilliance and her publishing triumphs, her brutal encounters with cancer. And let’s not forget that her mother was a narcissistic alcoholic.

*

And here is another creative Prince, the movie director François Truffaut (400 Blows, Jules and Jim, The Wild Child).

*

THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF DOGS AND CATS

~ We all know the numbers by now. Industrial meat production is the single biggest cause of global deforestation.

It creates an estimated 14.5 percent of all human-made greenhouse gas emissions — more than the combined emissions from all forms of transport. In the face of these alarming numbers, there has been a groundswell of people attempting to eat zero, or less, meat.

But what about the little carnivores that share our homes, our beloved pets?

In the US alone, at least 70 percent of households own pets, according to the 2020-2021 APPA National Pet Owners Survey, and many of them are dogs. There are an estimated 77 million individual dogs in America — the highest number since the American Veterinary Medical Association began counting in 1982. Worldwide, more than 470 million dogs live with human families.

But as the food packaging and poop baggies pile up, some owners have begun to wonder about the impact their furry friend is having on the planet. What do we know about dogs’ environmental paw print, and are there things we can do to mitigate it?

Far and away the biggest environmental impact our canine companions exert is through their diet. The global pet food market was worth almost $97 billion in 2020. More than one-third of that food was purchased in the US, with other large markets in the UK, France, Brazil, Russia, Germany and Japan.

US dogs and cats snarf down more than 200 petajoules (a unit that measures the energy content of food) worth of food per year — roughly the same as the human population of France, according to Gregory Okin, a researcher at UCLA’s Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. “We’re talking about animals whose consumption is on the order of nations,” he says.

For the typical American dog, about 33 percent of those calories come from meat. According to Okin’s calculations, dogs and cats eat about one-quarter of all the meat-derived calories consumed in the US — which means their diets account for one-quarter of all the land, water, fossil fuel, fertilizer and pesticide use associated with producing that meat.

The result: An additional 64 million tons of greenhouse gases are being pumped into the atmosphere each year. That’s equivalent to 13.6 million cars being driven for a year.

Keep in mind, too that Okin’s numbers only reflect the environmental impacts of producing animals for meat. They don’t include the energy costs of transporting, slaughtering or processing those animals to become food. “And the processing with pet food is intense,” he says. Meat and meat by-products are typically heat-sterilized, extruded or rendered before being packaged, put on a truck and shipped around the country. All of which means that Okin’s numbers represent just a portion of the problem.

Of course, what goes in must come out. US dogs and cats produce as much feces as 90 million American adults, Okin found. Most of that ends up in landfill, and by mass it rivals the total trash generated by the state of Massachusetts. No-one has even attempted to calculate the carbon cost of transporting it all there.

Dog poop contains pathogens including bacteria, viruses and parasites that can transmit disease to people and persist in the soil for years. It also contains nitrogen and phosphorus — nutrients which, when they’re washed into nearby lakes and streams during storms, can fuel an explosion of algae. The growing algae deplete the water of vital oxygen, causing fish and other aquatic life to suffocate and die.

Dog and man in Tbilisi. Photo: Mikhail Iossel

Then there’s the plastic waste. If you’re a responsible owner who dutifully picks up after your pooch, you may feel conflicted as you plow through hundreds of petroleum-based plastic baggies — at least 700 per year if your dog “does her business” twice per day. Even the “biodegradable” alternatives aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. That’s because they’re designed to break down under specific compost conditions, not in a landfill. But composting dog waste in your backyard is tricky and risky, and most municipal facilities do not accept pet waste. It’s a crappy predicament, all told.

And while food and feces are two immutable facts of dog ownership, all the little extras add up too. Toys are important to dogs’ mental and physical health, but many are made of plastic or contain elements that are difficult to recycle — and their durability is often poor.

Pet parents of all stripes spent almost one-third as much again on discretionary treats as they did on regular food in 2020. At least half of US owners bought Christmas and birthday gifts for their dogs in the past year. And then there are the outfits: More than 40 percent of dog owners admit to buying clothing or costumes for their dogs. All this discretionary stuff must be produced, packaged, shipped and, in many cases, delivered to our doors.

Our relationships with our pets enrich our lives on so many levels. So, what is an environmentally-conscious dog lover to do?!

First and foremost, says Okin: Buy cheaper food with a lower overall meat content. “A lot of the marketing is like: ‘Your dog is a wolf, and he needs to eat like a wolf!’,” he says, citing recent consumer trends towards premium foods built from human-grade cuts of meat. “He is not a wolf. His ancestors were wolves, but your dog is a dog,” he says, adding, “Dogs have been evolving with us for 15,000 years, to the point where their dietary needs are actually very similar to our own.”

Notably, dogs are better able to digest starches, an ability thought to be tied to three key genes: AMY2B, MGAM and SGLT1. While wolves, coyotes and jackals typically have just two copies of AMY2B, domestic dogs tend to have at least five times that — some with as many as 22 copies.

In fact, while cats are considered “obligate carnivores” — meaning that their diet requires nutrients found only in animal flesh — modern dogs are such omnivores that plant-based foods, including non-meat protein sources such as yeast, insects and (soon!) lab-grown protein, are realistic and healthy alternatives. (In fact, major pet food companies are already developing insect-based dog and cat foods.) Talk to your vet about how much protein your particular dog needs and go from there.

If you’re not ready to make the leap to vegan, you can make smaller tweaks such as being careful not to overfeed your dog and choose foods based on chicken or sustainably sourced fish instead of more environmentally taxing beef or lamb.

At the very minimum, says Okin, leave the human-grade cuts for humans. Advertisers have persuaded us to be leery of budget brands made of “meat by-products,” suggesting these are poor-quality fillers that humans wouldn’t eat, so why give them to our dogs? “Most of the time, they’re confusing ‘wouldn’t’ with ‘couldn’t’,” Okin explains. A by-product is, after all, a culturally-defined concept — something that doesn’t make it to supermarket shelves. But meat by-products’ nutritional value remains high, and your dog will not know the difference.

Your next priority should be to eliminate non-essential purchases. Your dog feels like part of the family, and it’s only natural you want to spoil him. But remember, he has no idea if it’s Halloween or Tuesday, and there are plenty of ways to express your love that don’t involve gifts. Chances are, nothing would make him happier than a trip to the shore or mountains or an indulgent extra 10 minutes at the dog park with his pals.

If your dog gets bored of new toys quickly, set up an exchange with other owners. Pick toys made of durable, natural materials such as sisal rope, or get creative and make your own out of household items or clothing that is beyond repair. You can even have a go at making dog treats yourself.

Planet-conscious buying behaviors that apply to other aspects of your life will work here too: Buy local so that you can pick up supplies yourself, on foot. If you need to order for delivery, buy in bulk to reduce packaging and delivery frequency.

Finally, if you’re thinking of getting your first dog — or you are “between dogs,” as Okin puts it — consider a small breed. “Instead of a 40-pound dog, get a 10-pound dog,” he says, because smaller dogs both consume less and produce less waste. “Or instead of a 10-pound dog, get a parrot. Dogs and cats are not the only intelligent, long-living companion animals.”

Ultimately, being a good planetary steward does not mean forgoing our dogs, Okin stresses. There are plenty of choices we can make, both small and large, to limit our doggos’ environmental impact while helping both them and the planet to thrive.

https://ideas.ted.com/the-environmental-impact-of-dogs-and-cats-and-how-to-reduce-it/?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

Small breeds live longer — as long as they are not the squashed-nose kind that can hardly breathe (I think breeding those should be outlawed as cruelty to animals). Jack Russell or a toy poodle, a Pomeranian, a beagle . . . or any small dog from a rescue center (preferably a mixed breed — less inbreeding improves the dog’s health and longevity).

Oh well, I know that dog lovers seem to go by criteria other than longevity. But perhaps it’s time that more of them became aware of the environmental effect of large breeds.

*

YOUNG COLLEGE-EDUCATED STAFFERS THREATEN TO RUIN THE CHANCES OF THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY

~ According to Shor, the problem with this permanent class of young staffers [in the infrastructure of the Democratic party] is that they tend to hold views that are both more liberal and more ideologically motivated than the views of the coveted median voter, and yet they yield a significant amount of influence over the party’s messaging and policy decisions. As a result, Democrats end up spending a lot of time talking about issues that matter to college-educated liberals but not to the multiracial bloc of moderate voters that the party needs to win over to secure governing majorities in Washington.

“It is descriptively true that people who work in campaigns are extremely young and much more liberal than the overall population, and also much more educated,” said Shor who at the advanced age of 30 says he feels practically geriatric in professional Democratic politics. “I think that this is pushing them to use overly ideological language, to not show enough messaging or policy restraint and, from a symbolic perspective, to use words that regular voters literally don’t understand — and I think that that’s a real problem.”

People who paid close attention to the 2016 presidential campaign probably remember the most-watched Democratic campaign commercial from the cycle, Hillary Clinton’s “Mirrors” ad, which featured images of young women gazing at themselves in mirrors intercut with footage of Donald Trump making disparaging comments about women. It was powerful stuff — at least among the young liberals on Clinton’s staff.

The “Mirrors” ad featured prominently in a series of experiments that Shor did with Civis to evaluate the effect of various Democratic campaign commercials on voters’ decisions. The findings of the experiments were not encouraging. For one, they found that a full 20 percent of the ads — including “Mirrors” — made viewers more likely to vote for Republicans than people who hadn’t seen the same ads. And after his team started polling members of Civis’s staff, they made an even more troubling discovery. On average, the more that the Civis staff liked an ad, the worse it did with the general public.

“The reason is that my staff and me, we’re super f---ing different than than the median voter,” said Shor. “We’re a solid 30 years younger.”

And while Shor is the most prominent proponent of the theory that young liberals wield too much power within the Democratic Party, he is hardly the first one to propose it. In 2015, the political scientists Ryan Enos and Eitan Hirsh published a paper in the American Political Science Review analyzing the results of a survey they conducted among staffers on Obama’s 2012 re-election campaign. Based on the results of their survey, Enos and Hirsh concluded that “in the context of the campaign widely considered most adept at direct contact, individuals who were interacting with swing voters on the campaign’s behalf were demographically unrepresentative, ideologically extreme, cared about atypical issues, and misunderstood the voters’ priorities.”

In reality, Shor says, young party staffers are far to the left of the median Democratic voters on relatively uncontroversial, bread-and-butter Democratic priorities like combatting income inequality or addressing climate change. In their 2015 paper, for instance, Enos and Hirsch found that 23 percent of Obama staffers cited income inequality as the single most important issue facing the country, whereas polls from that election cycle found that fewer than one percent of all voters listed “the gap between rich and poor” as the most important issue. Enos and Hirsch also found that campaign workers were more likely to cite health care and inequality as an important issue to voters — even though most voters did not list those as high-priority issues and said they were more concerned about things like war and inflation.

Shor knows that this theory can sound a bit conspiratorial — as if he’s asserting that a militant vanguard of Millennials and Gen-Zers have hijacked the Democratic Party for their own narrow purposes — but he is careful to specify that the reality is neither so sinister nor so complex. In fact, the mechanism that allows the views of young party staffers to exert a disproportionately strong influence over public perception of the Democratic Party is pretty straightforward.

Shor concedes that some version of this class of highly-educated neophytes has been a permanent feature of Democratic Party politics since at least the 1960s, but he argues that the downstream political effects of this demographic imbalance have gotten worse as the rise in education polarization — i.e. the tendency of highly educated voters to lean Democratic and less-educated voters to lean Republican—has exacerbated the ideological divide between Democratic staffers and the median voter.

“It’s always been true that this group was higher socioeconomic status and younger and all these other things, but the extent to which those biases mattered has changed a lot in the past ten years,” said Shor.

The way to compensate for these biases, Shor says, is twofold. The first is for Democratic candidates and their staff members to engage in more rigorous messaging discipline — in short, to “talk about popular things that people care about using simple language,” as Shor has defined his preferred brand of messaging restraint before. This approach would not preclude Democrats from talking about progressive-coded policy ideas that enjoy broad popular support, such as adopting a wealth tax on high earning individuals or mandating that workers receive representation on corporate boards.

In the longer term, however, the party will have to elevate the policy and messaging preferences of its moderate Black, Hispanic and working-class supporters over the preferences of young, highly-educated and liberal staffers.

“We are really lucky that we have a bunch of relatively moderate, economically progressive people in the Democratic Party who have close to median views on social issues and religiosity and all this other stuff, and the only thing is, most of them aren’t white,” Shor said. “Someone derisively told me that what I was saying is that we should be booking Maxine Waters instead of random [Black Lives Matter] activists, and I think that’s right. I think we should probably care what [Congressional Black Caucus] members think about things.”

The highly-educated young liberals who serve as the standard-bearers of the party’s platform are leading Democrats down a path toward political obscurity. Unfortunately for Democrats, this cadre of young people isn’t likely to disappear anytime soon.

“The reality is that highly educated people run almost every institution in the world, and that is like a very difficult thing to swim against,” as Shor put it. “A lot of what I’m saying is that people like me have too much power and too much influence.” ~

https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/10/09/david-shor-democrats-privileged-college-kid-problem-514992?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Mary:

Even with the knowledge that an asteroid probably was what destroyed Sodom and flattened the walls of Jericho, melting and atomizing everything in a large area, and the certainty that such destructive visitations will inevitably occur again, even knowing that our love of our pets is again one more way we increase our burden of waste and pollution on the earth, even with these large and legitimate concerns, what alarms me most is the assessment of the effect young liberals have on the Democratic party. Social justice crusaders and the left leaning staffers, all those young folk and their eagerness for change...if that becomes the face and the voice of the Democratic Party, it is certain to lose the support of moderates simply by skewing the message away from the priorities of the moderate majority. In some ways it's very simple, identity politics and virtue signaling are not core issues for the majority. Economic opportunity, health care, social security are all more important to the older and more moderate voters.

This is not to say that equality and respect for all genders is unimportant, that racial justice , equal opportunity and human rights does not demand our attention, but that the majority does not see these as the most primary and essential urgencies. The most liberal, most highly educated, and most ideologically motivated, may lose the attention, and the support, of the less liberal, less educated, less ideological, more moderate majority.

Divided as we are, polarized and seemingly ready to push even farther apart, these political culture wars may bring us to an impasse that invites a violent resolution. And that would be a social calamity big as an asteroid strike.

Oriana:

I shuddered reading the article; this crazy skew could certainly lead to major setbacks for the Democrats and to more Trumpism. After such a narrow escape! Still, how odd that our political asteroid would be out-of-touch young progressives — the obnoxious WOKE crowd hated by the majority of the country’s population; the privileged youngsters obsessed with which pronouns to use while humanity is threatened with extinction with more disasters than ever, and accelerating.

*

I remember my shock when I first heard (or read) that "All men were created equal" actually referred only to "all white male property owners." But since each age interprets important documents differently, there is no need to cling to the original meaning. Fortunately the language of this statement is vague enough (perhaps deliberately) as to easily allow it.

*

THE BIG BANG WASN’T THE BEGINNING

~ THE EXPANDING UNIVERSE

In the 1910s, astronomer Vesto Slipher started observing certain nebulae, which some argued might be galaxies outside of our Milky Way, and found that they were moving fast: far faster than any other objects within our galaxy. Moreover, the majority of them were moving away from us, with fainter, smaller nebulae generally appearing to move faster.

Then, in the 1920s, Edwin Hubble began measuring individual stars in these nebulae and eventually determined the distances to them. Not only were they much farther away than anything else in the galaxy, but the ones at the greater distances were moving away faster than the closer ones. As Lemaître, Robertson, Hubble, and others swiftly put together, the universe was expanding.

Georges Lemaître was the first, in 1927, to recognize this. Upon discovering the expansion, he extrapolated backward, theorizing — as any competent mathematician might — that you could go as far back as you wanted: to what he called the primeval atom. In the beginning, he realized, the universe was a hot, dense, and rapidly expanding collection of matter and radiation, and everything around us emerged from this primordial state.

Extrapolating back to as far as your evidence can take you is a tremendous success for science. The physics that took place during the earliest stages of the hot Big Bang imprinted itself onto the universe, enabling us to test our models, theories, and understanding of the universe from that time. The earliest observable imprint, in fact, is the cosmic neutrino background, whose effects show up in both the cosmic microwave background (the Big Bang’s leftover radiation) and the universe’s large-scale structure. This neutrino background comes to us, remarkably, from just ~1 second into the hot Big Bang.

But extrapolating beyond the limits of your measurable evidence is a dangerous, albeit tempting, game to play. After all, if we can trace the hot Big Bang back some 13.8 billion years, all the way to when the universe was less than 1 second old, what’s the harm in going all the way back just one additional second: to the singularity predicted to exist when the universe was 0 seconds old?

The answer, surprisingly, is that there’s a tremendous amount of harm — if you’re like me in considering “making unfounded, incorrect assumptions about reality” to be harmful. The reason this is problematic is because beginning at a singularity — at arbitrarily high temperatures, arbitrarily high densities, and arbitrarily small volumes — will have consequences for our universe that aren’t necessarily supported by observations.

For example, if the universe began from a singularity, then it must have sprung into existence with exactly the right balance of “stuff” in it — matter and energy combined — to precisely balance the expansion rate. If there were just a tiny bit more matter, the initially expanding universe would have already recollapsed by now. And if there were a tiny bit less, things would have expanded so quickly that the universe would be much larger than it is today.

And yet, instead, what we’re observing is that the universe’s initial expansion rate and the total amount of matter and energy within it balance as perfectly as we can measure.

Why?

INFLATION

If the Big Bang began from a singularity, we have no explanation; we simply have to assert “the universe was born this way,” or, as physicists ignorant of Lady Gaga call it, “initial conditions.”

Similarly, a universe that reached arbitrarily high temperatures would be expected to possess leftover high-energy relics, like magnetic monopoles, but we don’t observe any. The universe would also be expected to be different temperatures in regions that are causally disconnected from one another — i.e., are in opposite directions in space at our observational limits — and yet the universe is observed to have equal temperatures everywhere to 99.99%+ precision.

In 1922, Alexander Friedmann discovered the solution for a universe that's the same in all directions, and at all locations, where any and all types of energy, including matter and radiation, were present.

That appeared to describe our universe on the largest scales, where things appear similar, on average, everywhere and in all directions. And, if you solved the Friedmann equations for this solution, you’d find that the universe it describes cannot be static, but must either expand or contract.

Inflation says, sure, extrapolate the hot Big Bang back to a very early, very hot, very dense, very uniform state, but stop yourself before you go all the way back to a singularity. If you want the universe to have the expansion rate and the total amount of matter and energy in it balance, you’ll need some way to set it up in that fashion. The same applies for a universe with the same temperatures everywhere.

Inflation accomplishes this by postulating a period, prior to the hot Big Bang, where the universe was dominated by a large cosmological constant (or something that behaves similarly): the same solution found by de Sitter way back in 1917. This phase stretches the universe flat, gives it the same properties everywhere, gets rid of any pre-existing high-energy relics, and prevents us from generating new ones by capping the maximum temperature reached after inflation ends and the hot Big Bang ensues. Furthermore, by assuming there were quantum fluctuations generated and stretched across the universe during inflation, it makes new predictions for what types of imperfections the universe would begin with.

But things get really interesting if we look back at our idea of “the beginning.” Whereas a universe with matter and/or radiation — what we get with the hot Big Bang — can always be extrapolated back to a singularity, an inflationary universe cannot. Due to its exponential nature, even if you run the clock back an infinite amount of time, space will only approach infinitesimal sizes and infinite temperatures and densities; it will never reach it. This means, rather than inevitably leading to a singularity, inflation absolutely cannot get you to one by itself. The idea that “the universe began from a singularity, and that’s what the Big Bang was,” needed to be jettisoned the moment we recognized that an inflationary phase preceded the hot, dense, and matter-and-radiation-filled universe we inhabit today.

This new picture gives us three important pieces of information about the beginning of the universe that run counter to the traditional story that most of us learned. First, the original notion of the hot Big Bang, where the universe emerged from an infinitely hot, dense, and small singularity — and has been expanding and cooling, full of matter and radiation ever since — is incorrect. The picture is still largely correct, but there’s a cutoff to how far back in time we can extrapolate it.

Second, observations have well established the state that occurred prior to the hot Big Bang: cosmic inflation. Before the hot Big Bang, the early universe underwent a phase of exponential growth, where any preexisting components to the universe were literally “inflated away.” When inflation ended, the universe reheated to a high, but not arbitrarily high, temperature, giving us the hot, dense, and expanding universe that grew into what we inhabit today.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we can no longer speak with any sort of knowledge or confidence as to how — or even whether — the universe itself began. By the very nature of inflation, it wipes out any information that came before the final few moments: where it ended and gave rise to our hot Big Bang. Inflation could have gone on for an eternity, it could have been preceded by some other nonsingular phase, or it could have been preceded by a phase that did emerge from a singularity. Until the day comes where we discover how to extract more information from the universe than presently seems possible, we have no choice but to face our ignorance. The Big Bang still happened a very long time ago, but it wasn’t the beginning we once supposed it to be.

https://bigthink.com/starts-with-a-bang/big-bang-beginning-universe/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR2thvoo0te9KC4cLpEMeer7pO8WoZh2a1W4_wSz6qVil2jM6hVL9v9SczM#Echobox=1634132183-1

The modern cosmic picture of our universe’s history begins not with a singularity that we identify with the Big Bang, but rather with a period of cosmic inflation that stretches the universe to enormous scales, with uniform properties and spatial flatness. The end of inflation signifies the onset of the hot Big Bang. (Credit: Nicole Rager Fuller/National Science Foundation)

CYCLES OF BIG BANGS

~ A 2020 Nobel Prize winner in physics named Sir Roger Penrose believes that the universe goes through cycles of death and rebirth.

He believes that there have been multiple Big Bangs and that more will happen. Penrose points to black holes as holding clues to the existence of previous universes. Sir Roger Penrose is a mathematician and physicist from the University of Oxford, and he believes in the future there will be another Big Bang. Penrose won the Nobel Prize for working on mathematical methods proving and expanding Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

His work on black holes also helped him win the prestigious award showing that objects that become too dense undergo gravitational collapse into singularities, which are points of infinite mass. He believes that the universe will expand until all matter ultimately decays, and a new Big Bang will bring a new universe into existence.

He calls his theory, “conformal cyclic cosmology.” Penrose says he discovered six “warm” sky points known as “Hawking Points” first discovered by the late Prof. Stephen Hawking. Hawking believed that black holes leak radiation and eventually will evaporate. That evaporation could take longer than the current age of the universe, according to the scientist.

Penrose believes that we can observe what he calls dead black holes left by past universes. If he’s correct, it would validate some of Hawking’s theories. The theory is controversial, and like many theories, it may never be proven to be true or false. If he is right, the universe we know will one day explode, and a new one will come into existence. ~

https://www.slashgear.com/nobel-prize-winner-says-the-universe-has-gone-through-multiple-big-bangs-10641825/

a reader’s comment:

~ A Big Bang is such a biblical concept. Even scientists can’t escape the idea of creation. Maybe it’s because we are born & die that we can’t shake this. But in reality, there is no creation, just matter & energy transference. There have been multiple big bangs, but it’s not creation. The matter has simply compacted to a point before then exploding. It’s like a giant tidal wave that expands & then contracts. The universe is in a constant state of expansion & contraction. Big bangs... multiple big bangs are a constant.... but nothing is created. We need to think in terms beyond out human lives... or we will just end up never really understanding what is actually going on. ~

Oriana:

The writer of the above obviously has not read the article on inflation, which argues against a “single point.” But that’ perhaps minor, considering the continuity, rather than “creation.”

And with that I'm back to what my father, a university professor who taught theoretical physics, told me when I was eight or so and pestered him with Big Questions: the Universe has probably always existed. I was also sent to my first religion lessons just about the same age, and now I no longer remember if I first heard of the concept of no beginning and no end from a nun or from my father. Strange how it all converged.

I prefer to think in terms of the universe, because it implies no malice, no seeing every sinful thought in everyone's head, no constant (or delayed) punishment. If a child dies of brain cancer, that’s just laws of nature and the current state of medicine, rather than a cosmic monster who torments both the child and the parents in this particular way, and other human beings, along with animals, in other ways.

*

The Scottish Highlands and the Appalachians are the same mountain range, once connected as the Central Pangean Mountains. Remnants of this massive mountain range include the Appalachian Mountains of North America, the Little Atlas of Morocco, Africa, Ireland, much of the Scottish Highlands and part of Scandinavia. These are the oldest mountains in the world.

Oriana:

My fascination with tectonic plates goes back to childhood and an ancient paleontology textbook that I found on my parents' bookshelf. I learned about Pangea and more. It was a revelation much more interesting than the bible stories.

Mary:

That the Scottish Highlands and the Appalachian mountains are part of the same original range, split and separated by the movement of tectonic plates carrying the continents away from each other, is both a wonder and a comfort. A wonder because it is so enormous and surprising a conclusion, a comfort because it shows connections, similarities, congruences. All these mountains that have been such a part of literature, song and romance, the wild and beautiful countries that have shaped the imagination and the lives of all who lived there, or traveled through them, older than any of us, the oldest mountains in the world. Takes your breath away.

*

JESUS AS AN APOCALYPTIC PROPHET; THE CONCEPT OF MYTHOLOGY AS THE START OF THE SLIPPERY SLOPE

When it comes to atheist awakening, I’m thinking of my favorite epiphanies. The priest who lost his faith while re-reading the proofs of god’s existence is still #1, but in second place I’d put Bart Ehrman’s moment, which happened in the parking lot after Bart and friends had watched Monty Python’s The Life of Brian.

No, it wasn’t the chorus of the crucified singing and whistling “Always look on the bright side.” It was the line-up of apocalyptic preachers spouting their nonsense that was Ehrman’s, then a fundamentalist seminarian, neural lightning. Afterwards, in the parking lot, he was saying to his friend that of course Jesus wasn’t anything like those apocalyptic preachers — but as he was saying that, deep within, he saw that, on the contrary, Jesus was one of those apocalyptic preachers. After you’ve been hit by lightning, you can’t go back to the pre-lightning condition.

That ruined what remained of Jesus for me — Bart Ehrman’s fully convincing argument that Jesus was, first and foremost, an apocalyptic preacher typical of his times. Passages that previously didn’t make sense (e.g. "Let the dead bury the dead") now lit up with meaning. Of course I’d been an atheist since the age of 14, but some remnant affection for Jesus still glimmered. Now the words “A RELIGIOUS NUT CASE” lit up in neon. (Only in the modern context, and not in the context of the Ancient Near East — being an apocalyptic preacher was a respectable profession, I assume.)

Of course fundamentalists stubbornly cling to the literal reading, and there is no point telling them, “Jesus is never coming back. Never never never never.” If only one could somehow show them The Life of Brian, or explain the second coming metaphorically, e.g. “it can only take place in your heart.”

Now, considering my own “mythology” epiphany, I can’t help remembering that Dante and Milton did not reject classical mythology as “not real.” On the contrary, they carefully integrated various figures of pagan myth into their work (note, for instance, canto 26 of the Inferno, the Ulysses Canto). I wonder: did these great poets and great minds sense that as soon as we say, “Classical mythology is not real; it’s just made-up stories,” we cast doubt on Judeo-Christianity as well?

Did they sense that when we say, “Zeus did not really exist,” or "Wotan did not really exist," we are in danger of seeing that Yahweh did not really exist either? Perhaps we might as well get rid of the whole thing, starting with the creation in six days, the seventh being included because “on the seventh day God rested.” Why did God rest? Was he tired?

And when did that ultimately take place, this dismissal of classical mythology as fiction and “outworn creeds”? Soon after Milton, I suspect. And the more classical mythology was adored and used in literature, the more firmly it was accepted that all those stories were simply invented. — or, if they were based on some true events, the overlay of legend and supernaturalism was too deep to to remove.

But once you even have the concept of mythology, it’s a slippery slope. And once “comparative mythology” is born (18th century), and scholars begin to unravel layers upon layers of myth, the whole structure of religion begins to crumble.

*

The Second Coming is the greatest non-event in the history of humanity... and still people believe it! ~ Ken Homer

Oriana:

Yes, millions still believe it, even though Jesus foretold that his Second Coming was imminent (“Some standing here will not taste death”). Instead of Christ, what came was the Catholic church and other forms of organized Christianity. True believers don’t seem to be discouraged by mere reality.

*

HAS HUMAN LIFE SPAN INCREASED? LIFE EXPECTANCY VERSUS LIFE SPAN

~ While medical advancements have improved many aspects of healthcare, the assumption that human life span has increased dramatically over centuries or millennia is misleading.

Overall life expectancy hasn’t increased so much because we’re living far longer than we used to as a species. It’s increased because more of us, as individuals, are making it that far.

“There is a basic distinction between life expectancy and life span,” says Stanford University historian Walter Scheidel, a leading scholar of ancient Roman demography. “The life span of humans – opposed to life expectancy, which is a statistical construct – hasn’t really changed much at all, as far as I can tell.”

Life expectancy is an average. If you have two children, and one dies before their first birthday but the other lives to the age of 70, their average life expectancy is 35.

This averaging-out is why it’s commonly said that ancient Greeks and Romans, for example, lived to just 30 or 35. But was that really the case for people who survived the fragile period of childhood, and did it mean that a 35-year-old was truly considered ‘old’?

If one’s thirties were a decrepit old age, ancient writers and politicians don’t seem to have got the message. In the early 7th Century BC, the Greek poet Hesiod wrote that a man should marry “when you are not much less than 30, and not much more.” Meanwhile, ancient Rome’s ‘cursus honorum’ – the sequence of political offices that an ambitious young man would undertake – didn’t even allow a young man to stand for his first office, that of quaestor, until the age of 30 (under Emperor Augustus, this was later lowered to 25; Augustus himself died at 75). To be consul, you had to be 43 – eight years older than the US’s minimum age limit of 35 to hold a presidency.

In the 1st Century, Pliny devoted an entire chapter of The Natural History to people who lived longest. Among them he lists the consul M Valerius Corvinos (100 years), Cicero’s wife Terentia (103), a woman named Clodia (115 – and who had 15 children along the way), and the actress Lucceia who performed on stage at 100 years old.

Then there are tombstone inscriptions and grave epigrams, such as this one for a woman who died in Alexandria in the 3rd Century BC. “She was 80 years old, but able to weave a delicate weft with the shrill shuttle,” the epigram reads admiringly.

Not, however, that aging was any easier then than it is now. “Nature has, in reality, bestowed no greater blessing on man than the shortness of life,” Pliny remarks. “The senses become dull, the limbs torpid, the sight, the hearing, the legs, the teeth, and the organs of digestion, all of them die before us…” He can think of only one person, a musician who lived to 105, who had a pleasantly healthy old age. (Pliny himself reached barely half that; he’s thought to have died from volcanic gases during the eruption of Mt Vesuvius, aged 56).

In the ancient world, at least, it seems people certainly were able to live just as long as we do today. But just how common was it?

AGE OF EMPIRES

Back in 1994 a study looked at every man entered into the Oxford Classical Dictionary who lived in ancient Greece or Rome. Their ages of death were compared to men listed in the more recent Chambers Biographical Dictionary.

Of 397 ancients in total, 99 died violently by murder, suicide or in battle. Of the remaining 298, those born before 100BC lived to a median age of 72 years. Those born after 100BC lived to a median age of 66. (The authors speculate that the prevalence of dangerous lead plumbing may have led to this apparent shortening of life).

The median of those who died between 1850 and 1949? Seventy-one years old – just one year less than their pre-100 BC cohort.

Of course, there were some obvious problems with this sample. One is that it was men-only. Another is that all of the men were illustrious enough to be remembered. All we can really take away from this is that privileged, accomplished men have, on average, lived to about the same age throughout history – as long as they weren’t killed first, that is.

Still, says Scheidel, that’s not to be dismissed. “It implies there must have been non-famous people, who were much more numerous, who lived even longer,” he says.

Not everyone agrees. “There was an enormous difference between the lifestyle of a poor versus an elite Roman,” says Valentina Gazzaniga, a medical historian at Rome’s La Sapienza University. “The conditions of life, access to medical therapies, even just hygiene – these were all certainly better among the elites.”

In 2016, Gazzaniga published her research on more than 2,000 ancient Roman skeletons, all working-class people who were buried in common graves. The average age of death was 30, and that wasn’t a mere statistical quirk: a high number of the skeletons were around that age. Many showed the effects of trauma from hard labour, as well as diseases we would associate with later ages, like arthritis.

Men might have borne numerous injuries from manual labor or military service. But women – who, it's worth noting, also did hard labor such as working in the fields – hardly got off easy. Throughout history, childbirth, often in poor hygienic conditions, is just one reason why women were at particular risk during their fertile years. Even pregnancy itself was a danger.

“We know, for example, that being pregnant adversely affects your immune system, because you’ve basically got another person growing inside you,” says Jane Humphries, a historian at the University of Oxford. “Then you tend to be susceptible to other diseases. So, for example, tuberculosis interacts with pregnancy in a very threatening way. And tuberculosis was a disease that had higher female than male mortality.”

Childbirth was worsened by other factors too. “Women often were fed less than men,” Gazzaniga says. That malnutrition means that young girls often had incomplete development of pelvic bones, which then increased the risk of difficult child labor.

“The life expectancy of Roman women actually increased with the decline of fertility,” Gazzaniga says. “The more fertile the population is, the lower the female life expectancy.”

MISSING PEOPLE

The difficulty in knowing for sure just how long our average predecessor lived, whether ancient or pre-historic, is the lack of data. When trying to determine average ages of death for ancient Romans, for example, anthropologists often rely on census returns from Roman Egypt. But because these papyri were used to collect taxes, they often under-reported men – as well as left out many babies and women.

Tombstone inscriptions, left behind in their thousands by the Romans, are another obvious source. But infants were rarely placed in tombs, poor people couldn’t afford them and families who died simultaneously, such as during an epidemic, also were left out.

And even if that weren’t the case, there is another problem with relying on inscriptions.

“You need to live in a world where you have a certain amount of documentation where it can even be possible to tell if someone lived to 105 or 110, and that only started quite recently,” Scheidel points out. “If someone actually lived to be 111, that person might not have known.”

As a result, much of what we think we know about ancient Rome’s statistical life expectancy comes from life expectancies in comparable societies. Those tell us that as many as one-third of infants died before the age of one, and half of children before age 10. After that age your chances got significantly better. If you made it to 60, you’d probably live to be 70.

Taken altogether, life span in ancient Rome probably wasn’t much different from today. It may have been slightly less “because you don’t have this invasive medicine at end of life that prolongs life a little bit, but not dramatically different,” Scheidel says. “You can have extremely low average life expectancy, because of, say, pregnant women, and children who die, and still have people to live to 80 and 90 at the same time. They are just less numerous at the end of the day because all of this attrition kicks in.”

Of course, that attrition is not to be sniffed at. Particularly if you were an infant, a woman of childbearing years or a hard laborer, you’d be far better off choosing to live in year 2018 than 18. But that still doesn’t mean our life span is actually getting significantly longer as a species.

ON THE RECORD

The data gets better later in human history once governments begin to keep careful records of births, marriages and deaths – at first, particularly of nobles.

Those records show that child mortality remained high. But if a man got to the age of 21 and didn’t die by accident, violence or poison, he could be expected to live almost as long as men today: from 1200 to 1745, 21-year-olds would reach an average age of anywhere between 62 and 70 years – except for the 14th Century, when the bubonic plague cut life expectancy to a paltry 45.

Did having money or power help? Not always. One analysis of some 115,000 European nobles found that kings lived about six years less than lesser nobles, like knights. Demographic historians have found by looking at county parish registers that in 17th-Century England, life expectancy was longer for villagers than nobles.

“Aristocratic families in England possessed the means to secure all manner of material benefits and personal services but expectation of life at birth among the aristocracy appears to have lagged behind that of the population as a whole until well into the eighteenth century,” he writes. This was likely because royals tended to prefer to live for most of the year in cities, where they were exposed to more diseases).

But interestingly, when the revolution came in medicine and public health, it helped elites before the rest of the population. By the late 17th Century, English nobles who made it to 25 went on to live longer than their non-noble counterparts – even as they continued to live in the more risk-ridden cities.

Surely, by the soot-ridden era of Charles Dickens, life was unhealthy and short for nearly everyone? Still no. As researchers Judith Rowbotham, now at the University of Plymouth, and Paul Clayton, of Oxford Brookes University, write, “once the dangerous childhood years were passed… life expectancy in the mid-Victorian period was not markedly different from what it is today.” A five-year-old girl would live to 73; a boy, to 75.

Not only are these numbers comparable to our own, they may be even better. Members of today’s working-class (a more accurate comparison) live to around 72 years for men and 76 years for women.

“This relative lack of progress is striking, especially given the many environmental disadvantages during the mid-Victorian era and the state of medical care in an age when modern drugs, screening systems and surgical techniques were self-evidently unavailable,” Rowbotham and Clayton write.

They argue that if we think we’re living longer than ever today, this is because our records go back to around 1900 – which they call a “misleading baseline,” as it was at a time when nutrition had decreased and when many men started to smoke.

PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE

What about if we look in the other direction in time – before any records at all were kept?

Although it is obviously difficult to collect this kind of data, anthropologists have tried to substitute by looking at today's hunter-gatherer groups, such as the Ache of Paraguay and Hadza of Tanzania. They found that while the probability of a newborn’s survival to age 15 ranged between 55 percent for a Hadza boy up to 71 percent for an Ache boy, once someone survived to that point, they could expect to live until they were between 51 and 58 years old. Data from modern-day foragers, who have no access to medicine or modern food, write Michael Gurven and Cristina Gomes, finds that “while at birth mean life expectancies range from 30 to 37 years of life, women who survive to age 45 can expect to live an additional 20 to 22 years” – in other words, from 65 to 67 years old.

Archaeologists Christine Cave and Marc Oxenham of Australian National University have recently found the same. Looking at dental wear on the skeletons of Anglo-Saxons buried about 1,500 years ago, they found that of 174 skeletons, the majority belonged to people who were under 65 – but there also were 16 people who died between 65 and 74 years old and nine who reached at least 75 years of age.

Our maximum lifespan may not have changed much, if at all. But that’s not to delegitimize the extraordinary advances of the last few decades which have helped so many more people reach that maximum lifespan, and live healthier lives overall.

Perhaps that’s why, when asked what past era, if any, she’d prefer to live in, Oxford’s Humphries doesn’t hesitate.

“Definitely today,” she says. “I think women’s lives in the past were pretty nasty and brutish – if not so short.”

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/do-we-really-live-longer-than-our-ancestors?utm_source=pocket-newtab

*

*

A SIX-WORD MANTRA TO COMBAT ANXIETY

~ Back in 1927, 24-year-old Claire Weekes, a brilliant young scholar on her way to becoming the first woman to attain a doctorate of science at the University of Sydney, had developed an infection of the tonsils, lost weight and started having heart palpitations. Her local doctor, with scant evidence, concluded that she had the dreaded disease of the day, tuberculosis, and she was shunted off to a sanatorium outside the city.

‘I thought I was dying,’ she recalled in a letter to a friend.

Enforced idleness and isolation left her ruminating on the still unexplained palpitations, amplifying her general distress. Upon discharge after six months, she felt worse than when she went in. What had become of the normal, happy young woman she was not so long ago?

Flash forward to 1962 and the 59-year-old Dr Claire Weekes was working as a general practitioner, having retrained in medicine after an earlier stellar career in science during which she earned an international reputation in evolutionary biology. That year she also wrote her first book, the global bestseller Self-Help for Your Nerves.