*

NON-JUDGMENT DAY

Here’s what slipped into my heart:

that crested yellow tongue

down the runway of parched truth:

and those petals’ pulsing blue,

the excitable color of now:

like coming on a meadow of wild iris.

Long ago in dank woods,

I blundered on a dell

of lilies-of-the valley:

white lovers palm to palm

between leaves. That’s why God

must be forgiven, and why Dante puts

those who weep when they should

rejoice in a muddy pocket of hell

near the wood of suicides. After youth’s

‘love is pain’, that blue-purple flight.

On Non-Judgment Day, in the Valley

of Saved Moments,

I will bloom, the wildest iris.

~ Oriana

One flower redeems the world — yes, I believe this. Against all suffering, the beauty of one iris.

Because pain passes, but beauty remains.

To me beauty is the kind of consolation that religion never was. Religion was about being manipulated by the carrot and stick: the pie in the sky (pardon the mixed metaphor) versus eternal torture in hell. Beauty made no demands. I didn’t have to go down on my knees and beat my breast: my fault, my fault, my most grievous fault. Beauty has been an unconditional gift.

“After youth’s ‘love is pain’, that blue-purple flight.” I wouldn’t be able to find that mountain meadow again, especially now, after so many years of drought. But it is enough to have seen it once.

Still, the most important phrase in the poem is “Non-Judgment Day.” This signals perhaps the most important shift in the history of humanity. As I explain later: “Arguably the most important revolution in modernity has been away from seeing people as evil sinners who need punishment rather than as wounded human beings who need healing.”

Do we have the right to punish people? Billions would reply “Yes” without hesitation. Parents certainly think they have the right to punish children. “Justice” is just a nicer word for revenge. Of course it sounds better to say, “We want justice” than “We want revenge. We want the “bad guy” to suffer enormously. Yes, even forever. Payback!!

And yet I think that at least in terms of the “creeping enlightenment” I’ve observed over the decades, there has been a movement away from cruelty. It is not as legitimate as it used to be.

We seem to have finally understood: THE WISH TO PUNISH STEMS FROM THE DESIRE FOR REVENGE.

*

A strange thing, our punishment! It does not cleanse the criminal, it is no atonement; on the contrary, it pollutes worse than the crime does. ~ Nietzsche, The Dawn

Non-Judgment Day is already a blasphemy, but in keeping with Christ’s “Judge Not.” To make it even more blasphemous (as well as in keeping), it should be called “Mercy Day.”

Too bad nothing of the sort will happen (I think it would be both interesting and “educational”), unless in some way already in this life. I bet someone must have already said, “Every day is Judgment Day.” This I counter with “Every day is Mercy Day.”

The beauty of the world and the tender moments in life are the mercy.

Mary:

A lovely poem, days like that a gift both undeserved and unforgettable, for which, surely, we must forgive god all the rest. That yellow tongue of the iris, the white lovers of the lilies of the valley, in such abundance, and these are springtime flowers, the sudden bounty of resurrection.

My mother loved lilies of the valley, and I had them in Pennsylvania, they won't grow here.But our camellias are blooming, red like full blown roses, and every day I am blessed by birds..today mockingbirds, cardinal, osprey, hawk, pelican, cormorant, ibis, egret, heron, gulls. Such riches!!

*

“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster.

This is the whole of the story and we might have left it at that had there not been profit and pleasure in the telling; and although there is plenty of space on a gravestone to contain, bound in moss, the abridged version of a man's life, detail is always welcome.”

~ Vladimir Nabokov, "Laughter in the Dark”

*

READING LITERARY VERSUS POPULAR FICTION SHAPES OUR GRASP OF COMPLEXITY

~ A study published in PLOS One suggests that the type of fiction a person reads affects their social cognition in different ways. Specifically, literary fiction was associated with increased attributional complexity and accuracy in predicting social attitudes, while popular fiction was linked to increased egocentric bias.

“We learn a lot about ourselves, interpersonal relations, how institutions work, etc., from fiction. In other words, fiction impacts what we think about the world. But in my research, I am interested in the ways in which fiction shapes how we think,” explained study author Emanuele Castano of the University of Trento and the National Research Council in Italy.

“The original work, published with my former student David Kidd in the journal Science, showed that not all fiction shapes how we think in the same way. We distinguished between literary (e.g. Don Delillo, Jonathan Franzen, Alice Munroe) and popular fiction (e.g. Dan Brown, Tom Clancy, Jackie Collins), and showed that it is by reading literary fiction that you enhance your mindreading abilities — you are better at inferring and representing what other people think, feel, their intentions, etc.”

“In the latest article, with my former student Alison Jane Martingano and philosopher Pietro Perconti, we broaden the spectrum of variables we look at, and most importantly we develop our argument about the two types of fiction and their role in our society,” Castano said.

Scholars have typically differentiated between literary and popular fiction. For example, engaging with literary fiction is thought to be active; it asks readers to search for meaning and produce their own perspectives and involves complex characters. Popular fiction, on the other hand, is passive; it provides meaning for the readers and is more concerned with plot than characters.

Consequently, as Castano and team propose, literary and popular fiction likely affect cognition in different ways.

The researchers conducted a study involving 493 individuals with an average age of 34. Subjects completed a version of the Author Recognition Test where they were asked to indicate which authors they were familiar with among an extensive list of authors. Subjects were then given scores based on how many literary fiction versus popular fiction authors they recognized.

Next, the subjects completed a measure of Attributional Complexity, a construct which, “includes the motivation to understand human behavior, along with the preference for complex explanations of it.” They further took part in a false consensus paradigm to measure their egocentric bias — the extent to which they believe others share the same thoughts and attitudes as they do. Finally, their mental state recognition was assessed through the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET), a task measuring their accuracy in recognizing a person’s mental state based on that person’s eyes.

The results revealed key differences between respondents who engaged with literary fiction and those who read popular fiction. As the researchers expected, reading literary fiction was a positive predictor of attributional complexity, while popular fiction was a negative predictor. As the authors discuss, because literary fiction “paints a more complex picture of human affairs, and of the human psyche, than popular fiction . . . we should find that readers of literary fiction develop more complex schemas about others, their behavior, and about the social world they inhabit.”

Also in line with the researchers’ predictions, exposure to literary fiction was linked to reduced egocentric bias, while popular fiction was not. “Compared to popular fiction,” the authors explain, “literary fiction is theorized to encourage the simultaneous entertaining of a multiplicity of perspectives. To take into consideration other perspectives should reduce the tendency to see our own construcls as objective, and thus to rely less on them when making attributions about others and predicting their behavior.”

Finally, being exposed to literary fiction predicted better accuracy in recognizing others’ mental states (via the RMET), while popular fiction did not. “If a tendency to consider and appreciate other perspectives reduces ego-centric biases,” the researchers reason, “it should therefore enhance accuracy, which we define as the capacity to accurately represent others’ opinion, beliefs, intentions, emotion or attitudes at the individual mind level, or at the social level.”

“Exposure to literary fiction, as opposed to popular fiction, predicts the degree of complexity with which you analyze the social world. Exposure to popular fiction seems to, in fact, reduce it. Those who read relatively more literary fiction are also more accurate when they estimate other people’s average opinion,” Castano told PsyPost.

The researchers caution against inferring that literary fiction is inherently better than popular fiction. Instead, they stress that the two types of fiction cultivate different — and, in both cases, meaningful — socio-cognitive processes.

“Most importantly, the reader should take away what we are not saying: We are not saying that literary fiction is better than popular fiction. As human beings, we need the two types of thinking that are trained by these two types of fiction. The literary type pushes us to assess others as unique individuals, to withhold judgment, to think deeply. It is important, but it can paralyze us in our attempt to navigate the social world. The popular type reinforces our socially-learned and culturally-shared schemas; a mode of thinking that roughly corresponds to what Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman calls System 1: fast, automatic, well-practiced,” Castano explained.

“I submit that for a well functioning society a continuous tension between these two types of thinking styles – and thus both types of cultural products that, among other factors, promote them. Too much literary, and we disintegrate as a society. Too much popular, and we ossify. Neither scenario is auspicious.”

“Some of our evidence comes from experimental work, so we are quite confident of the causal effect: reading literary fiction leads to stronger Theory of Mind, for instance. Other findings are correlational: we measure exposure to types of fiction, rather than manipulating exposure experimentally. Therefore, there are potential alternative explanations for our findings,” Castano said.

“The goal is not for me to be right, but for us collectively, as cognitive scientists in this case, to be able to uncover the fascinating relationship between how the very cultural products that we develop in turn affect the way we think,” Castano added. ~

https://www.psypost.org/2020/10/reading-literary-versus-popular-fiction-promotes-different-socio-cognitive-processes-study-suggests-58381?fbclid=IwAR2r8MbY5eVh63qQU09NrWPxJCTJw8wHOQJFzkuoLt4WOkuyGcowx_Kvy-c

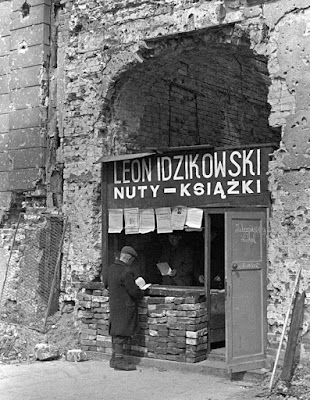

Bookstore in the ruins of Warsaw, 1945

Alta Ifland:

I've always said that it's better not to read than to read bad literature. This article is very interesting and it confirms what I've always known: “Exposure to literary fiction, as opposed to popular fiction, predicts the degree of complexity with which you analyze the social world. Exposure to popular fiction seems to, in fact, reduce it. Those who read relatively more literary fiction are also more accurate when they estimate other people’s average opinion."

Alexandru Baltag

Many people living in communism were much more free spirits, regardless of whether or not they were brave enough to act on it. Their inner lives were as rich and complex and daring as the outside world was poor and simple and oppressive. It is a bit similar to the spread of mysticism and gnostic cults during the decay of the Roman Empire. When people feel powerless and completely lose control over their lives and future, they become more reflexive. Paradoxically, a more grey and oppressive or unidimensional external reality can make people more complex and multidimensional in their inner life. Medieval monasticism used this paradox to create a rich spiritual life through external deprivation and submission. I am not advocating this as a “solution.” God forbid, I love to be really free, externally, and I wouldn’t ever want to return to a totalitarian society or to a medieval monastery. But I am just remarking on a paradoxical feature of human nature…

Oriana:

Based on my Polish experience, I'd like to add that the free spirit showed itself in the arts (Poland was much more free than the Soviet Union). The post-war decades were the Golden Age of modern Polish poetry, avant-garde theater and cinema and the visual arts. Even TV shows were interesting, subtle, ironic. Then came independence and the miasma of Catholicism and right-wing "patriotism."

I also greatly appreciate Alexandru's insight about the rich inner lives in medieval monasteries (which gave us some gorgeous art).

Previous studies showed that reading literary fiction leads to increased empathy (all my friends agree that they bond with literary characters, who become more real to them than actual people; one explanation of that is that a novel gives us access to a character’s inner life).

But fiction no longer has the importance it had in the nineteenth century— the world of Dickens, Tolstoy, Hugo, Flaubert, George Eliot, Henry James, Dostoyevsky, and other giants. What we now have is movies, some of them being closer to literary fiction (in fact some of them are adaptations of great novels), and some being the equivalent of pulp fiction. We have classical music and popular music. Again, the main divide is depth and complexity.

If we studied quality movies vs "popular entertainment" and classical music vs pop, it's an easy guess that the findings on complexity and empathy would be very similar. However, people who don't typically read literary fiction may still be deeply affected by certain movies and TV shows that expand their mental horizons.

Mary: GREAT FICTION BECOMES INEXHAUSTIBLE

Having just reread Jane Eyre I can concur with those saying literary fiction enriches and deepens our knowledge of character, and that deep inward consciousness of the self. Who better as exemplar of character integrity than Jane herself, who insists on her own integrity in every situation, even when she is alone and without hope, and almost falls into the temptation to abnegate herself and be subsumed into the will and life of cold and strictly righteous St John...a choice she knows will mean not only the loss of her own separate and singular identity, but of her life itself, unfit for the rigors of a missionary life in India's climate. The novel may use a romantic trope to accomplish Jane's escape, and her reunion with Mr Rochester, not to mention he has been broken in body, perhaps a punishment for his unlawful attempt to wed Jane while Bertha still lived, but Jane does not subsume herself in Rochester — she rather becomes even more herself, sensible, kind and wise, retaining always her characteristic independence of mind.

As in most great literary fiction, the plot may carry us on, but the heart of the thing is the interior lives of the characters...here principally Jane, our narrator, whose eyes and mind filter all the action and its meaning for us...it is this that is the great attractor here, this the treasure the reader opens, page by page...that identity, mind, heart and soul, that gives both impetus and meaning to all action. We are not simply following the events of a life, we are engaged in its very core, how it is known and felt from the inside.

As we read we in many ways become Jane, share her feelings and her fears, learn as she learns, win and lose with her. She is real to us in ways the characters of most popular fiction are not, because they don't have that same complexity and depth of characterization. The focus is not on communicating or sharing their inner life, but following the chain of events in a plot. The effect on the reader is much different, and in my experience, less rich, more temporary, without the resonance and depth of engagement demanded by literary fiction.

Most popular fiction is a one read affair...not something to return to again and again, always finding there something rich and wonderful, maybe even something different than what we found before, because we are different, and time has passed . Truly great fiction becomes in a way inexhaustible, something not just to be recovered but rediscovered again and again.

Oriana:

Yes, yes, and yes. And the same test of greatness holds for poems: can we return to them again and again, each time finding something new, or a possible new interpretation? Do we find them inexhaustible?

Fiction has more resources: we can indeed become the characters, or at least very close friends of the characters. Some can become more vivid than actual friends! This phenomenon is usually explained by invoking interiority: we know a literary character better than an actual friend because the author gives us access to their inner lives.

And Jane Eyre in particular -- what a role model for women, showing them how to be strong in difficult situations.

The churchly babblings about the sin of despair while it’s the church itself that teaches you that you are “unworthy,” should be examined in the light of child abuse. It’s very hard to completely liberate oneself from the aftermath of that early harm to your self-esteem.

*

Every man has some reminiscences which he would not tell to everyone, but only to his friends. He has others which he would not reveal even to his friends, but only to himself, and that in secret. But finally there are still others which a man is even afraid to tell himself, and every decent man has a considerable number of such things stored away. ~ Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes from the Underground

~ At least half of what it takes to find peace is lowering expectations, finding work-arounds, settling for incomplete satisfaction. ~ Jeremy Sherman

Jeremy continues:

It's not the same challenge for all of us. It's far easier to sing que sera, sera when you know how you're going to pay the rent and aren't trying to guess the better treatment to try for your child's probably-terminal cancer.

And then there's the internal psychological weather. One of the most fortunate people I know suffers high lifelong chronic anxiety. ~

*

MUSCLE COMES FROM THE LATIN FOR "LITTLE MOUSE", MUSCULUS (THE DIMINUTIVE OF MUS).

Two explanations are usually given for the peculiar transformation of mouse to muscle. One has it that the movement of a contracting muscle under the skin is reminiscent of a mouse moving beneath a rug; The biceps brachii is typically used as an example. The other explanation is that, in the abstract at least, some muscles look a bit like mice: specifically those with long, thin tendons (the mouse tails) emerging from oblong muscle bodies. The muscles of the forearm are among many that are illustrative.

The second explanation is as plausible as the first, though neither seems compelling. Why any relatively large muscle would be called a little mouse in the first place remains a mystery. (A sense of humor on the part of early anatomists cannot be ruled out!). In any event, it could easily have been muscles of dissected animals and not humans that were were the inspiration for the name.

Interestingly, mussel (the mollusk) is also derived from musculus, perhaps because some species have the shape of a mouse ear.

The difference in spelling between "muscle" and "mussel" is due to the different post-Latin paths taken by musculus. Muscle comes to us through French; mussel came out of Old English.

http://anatomyalmanac.blogspot.com/2007/07/muscle-comes-from-latin-for-little.html

*

WHY BIRDS LIVE LONGER THAN MAMMALS

~ Why do birds typically live longer than mammals? A new paper offers a hint, albeit not a conclusive answer. Assistant Professors of Biology Cynthia Downs and Ana Jimenez at Hamilton College and Colgate University respectively have co-authored a paper with nine students, "Does cellular metabolism from primary fibroblasts and oxidative stress in blood differ between mammals and birds? The (lack-thereof) scaling of oxidative stress" in press with Integrative and Comparative Biology.

The research group focused on testing whether birds and mammals have differential patterns in cellular metabolism as expected because of their difference in whole-animal rates of energy use. They also tested whether birds had higher antioxidant concentrations to ameliorate the higher concentrations of reactive oxygen species. One of their goals was to determine if birds and mammals differ in the amount of damage caused by the balance of reactive oxygen species and antioxidants concentrations (oxidative stress). Because whole-organism rates of energy use also changes in a predictable manner, another goal was to determine if components of oxidative stress changed with body size.

Their results suggest that cellular rates of energy use, total antioxidant capacity, damage to lipids and an enzymatic antioxidant (i.e., catalase activity) were significantly lower in birds compared with mammals. "We found that cellular rates of energy use and measures of components of oxidative stress didn't differ with body size. We also found that most oxidative stress parameters significantly correlate with increasing age in mammals, but not in birds; and that correlations with reported maximum lifespans show different results compared with correlations with known aged birds," authors Downs and Jimenez explained. "We also conducted a literature search and found that measurements of oxidative stress for birds in basal condition are rare.”

According to the authors, this is one of the first cross-species studies of oxidative stress that compares birds to mammals in an attempt to understand differences in why birds live longer than mammals of the same body mass despite the fact that they have higher rates of energy use. Their results suggest that birds demonstrate overall lower levels of oxidative stress, which may or may not be linked to their longer lifespans. The authors plan to focus on within species differences in oxidative stress and the link to immune defenses in the future. ~

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/05/190501114555.htm

Wisdom the albatross, banded in 1956, just had another chick.

Oriana:

Let's not forget the longevity of bats, in contrast with that of mice.

~ On average, the maximum recorded life span of a bat is 3.5 times greater than a non-flying placental mammal of similar size. Records of individuals surviving more than 30 years in the wild now exist for five species. ~ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12882342/

from another source:

~ Birds are remarkably long lived for their body size when compared with mammals. Since birds have a higher metabolic rate, body temperature, and a higher resting glucose than that of mammals, it is assumed the parameters of aging are increased. These metabolic factors should lead to a reduced, not increased, life span. The exceptional longevity in birds suggests they have evolved special mechanisms to protect them from rapid aging in the wake of their increased metabolic processes. How is it that they are able to do it?

Flying allows escape from predation. Data show that there is an increased life span in birds and in mammals that can fly [bats]. Recent data shows that those animals that routinely undergo exertional exercise have longer life spans than those that do not. Birds have lower levels of oxidative damage in their mitochondrial DNA despite the increased energy required for flight. So what does this mean? These metabolic processes normally cause the release of free radicals and those bind to cellular components — particularly membranes. That causes the membranes to age and the normal processes of the membranes to malfunction or to perform less well.

But birds, particularly psittacines (parrots), live much longer than they are supposed to live. In fact the large macaws live on average four times their predicted life spans! Birds in general have a reduction in oxidative damage. This signifies that birds have lower levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or have developed strategies to reduce the damage associated with them. Birds also have a complex array of mechanisms to reduce damage from oxidative processes. For example, male quail show plasticity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis despite the reduced fertility associated with aging. If only we could do that when we age! White matter tracts in the CNS of passerines regrow neurons related to song seasonally, which defies current mammalian dogma. If we could understand how they regrow tracts in their spinal cord and brain, it could help stroke victims and those with spinal cord injuries.

https://lafeber.com/pet-birds/birds-live-long/

parrot and chick

WHY DOGS LIVE SHORT LIVES COMPARED WITH WOLVES

~ This is something that has baffled scientists and dog owners for ages.

They have been bred by humans (not nature)

One theory is that our domesticated dogs have been cross-bred many times. Nature didn’t do this election for them. Humans did.

Nature, as we know, has a tendency to select the strongest breed over the weaker breed. But the dogs we have today are mostly bred according to what humans think is appropriate for work tasks or what we think is looking cute.

A good example here is the English bulldogs. Really cute fellas, but in fact, they aren’t even able to breathe naturally without making snoring sounds!

People have typically favored looks over strength and when we wanted to breed strong dogs we often just judge them by the looks. Nature tends to naturally select the strongest genes and make sure that the race gets stronger and stronger over time.So by choosing cuteness over the life span and ability to survive, we may have been part of the reason why dogs do not live as long as their ancestors: wolves.

Another theory is that dog breeder has a tendency to favor “pure breeds” over mixed breeds.

Prices have gone up and up for “pure dog breeds” where you are absolutely sure they are not mixed with any other breed. People will go to great lengths to make sure their dog is a pure breed champion!

This level of selective breeding is not good for making sure we have the best gene pool.

In nature, dogs would naturally cross-breed over and over again and we would have newer and (probably) stronger breeds over time.

Too much vaccination and bad food

Other scientists argue that the reason why dogs live shorter lives should be found in the way we use the medicine.

Veterinarians are using vaccines on dogs and other pets which causes them to survive even though they may not be strong animals. That means we have weak dogs and pets mixed into our breeds. Maybe the puppy would have better genes if its parents were the strongest they could be.

But vaccination is one of the primary income sources for veterinarians so it would be very hard to decrease the number.

Dog food is not what it used to be.

Back in the good old days, dogs would eat whatever was left over from the meal. That would be crops and other good stuff from local farm production.

Today we feed our pets pre-fabricated pet food with GMO ingredients. They are often pumped with unnatural elements because the rules regarding pet food are less strict than the rules we have for our own food. And our own food is not that good, to begin with!

So if you want to prolong the life of your pet and give it the best possible conditions for long life you should avoid pre-fabricated pet food.

Evolution tends to favor bigger creatures

Another theory is in relation to the size of dogs. Because dogs are smaller than humans they also live shorter lives.

Let’s take an elephant for example. The elephant doesn’t have many natural enemies and therefore it lives a very long life. The same goes for the Blue Whale, Giant Tortoise, and a lot of older bigger, and huge animals.

So because they don’t have many natural enemies (or any at all) the “evolutionary pressure” is lower and they get favored by nature.

But if you ask me this is a pretty silly argument. But nonetheless, it is a theory and we do not know for sure why dogs do not live as long as humans or other bigger mammals.

Dogs may have lived longer ages ago

Dogs evolved from wolves and wolves live almost twice as long as dogs when you take their size into consideration.

Wolves live up to 20 years in the wild and a dog the size of a wolf would normally only live around 10 years!

Why Do Smaller Dogs Have a Longer Lifespan?

The smaller they are, the longer they tend to live. So your Golden Retriever will not get as old as your Chihuahua.

It is actually pretty weird because normally bigger mammals live longer than smaller mammals. This is true for a lot of animals but among dog breeds, it seems to be the opposite.

Even though there are exceptions to this rule.

Let’s take parrots, for instance. Some of the Macaws can get up to 80 years of age. And they are pretty small compared to your Labrador!

The reason small dogs have a longer life span is still unknown but let’s take a look at some of the theories around this.

One theory is that bigger dogs are more prone to get age-related illnesses. There’s no good explanation for this theory, however, so it’s just pushing the question forward. Because why would bigger dogs be more prone to get age-related illnesses?

Larger dogs grow faster to reach a bigger size

This is another theory. Because larger dogs have to grow faster in order to get bigger they might be more likely to develop tumors and abnormal cell behavior. This could cause them to die prematurely from cancer.

My own theory is that smaller dogs have smaller bodies and therefore they have less body mass to be exposed to danger like radiation (over time) or even roadkill etc. This could cause them to live longer but probably not TWICE as much as bigger dogs.

Scientists have found out that for every 4,4 pounds (2 kilograms) of body mass a dog’s life is reduced by a month.

This actually means that smaller dogs can live twice as long as huge dogs.

The winner here is the Miniature Dachshund with an impressive lifespan of around 14 years. (man-years that is, in dog years that would be almost 108 years!).

We have to look among the biggest dog breeds to find the poor dog with the shortest lifespan.

At the bottom of the chart, we find the Bulldog. It will typically only live for around 6 years. That’s 48 years in dog years. That’s less than half the lifespan of the lucky Miniature Dachshund.

From what we found out about size and lifespan we would expect the dog with the shortest lifespan to be a really big dog.

That’s surprisingly enough we find the bulldog at the bottom of the list which is not one of the really big dogs.

The reason we find a Bulldog to have the shortest lifespan among the dog breeds is found in how the nose is constructed. The Bulldogs often have trouble breathing right. Especially the English Bulldog which is a perfect example of breeding gone wrong.

https://animalhow.com/why-dogs-live-short-lives/

Oriana:

The phenomenon of smaller breeds living longer isn’t confined to dogs. Ames Dwarf Mice and Snell Dwarf Mice also live longer than full-size mice. Their longevity is assumed to derive from low growth hormone and low insulin levels.

When it comes to breeds of horses, the bigger the horse, the shorter the lifespan.

With humans, it’s been hypothesized that the main reason women tend to live longer than men is their smaller size. If you compare women with men of the same size, the difference in longevity supposedly disappears.

“In Japan you see those tiny old ladies running up the many steps to a temple like nothing,” I remember someone saying. The advice I got from a Japanese neighbor: Drink a lot of tea.

“In people, height is negatively correlated with longevity; that is, taller individuals don’t tend to live as long.“ Shorter people have been found to be more resistant to cancer, but basically we don’t really understand why smaller size is a factor (one of many) in longer life expectancy." (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/when-bigger-mammals-live-longer-smaller-ones-why-do-taller-humans-die-younger-a7614436.html)

Still, we should bear in mind that in humans, the best predictor of longevity is high IQ. On average, Harvard athletes don’t live as long as Harvard professors. And smartest breeds of dogs, such as the poodle, are also known to live longer.

Finally, it seems that wolves are lean, while dogs tend to be overfed and become obese.

(A shameless digression: A friend of mine once acquired a Great Dane. The dog jumped on me and almost knocked me down to the floor. And that huge, slobbering muzzle . . . But the next news I received was that the dog was sick and had to be put down. He wasn't even five years old yet. But I heard that a Great Dane is "old enough to die" already at the age of five.)

Lilith:

I had a friend who always had Great Danes, all of them gentle giants, and none of them lived more than five or six years. When one died, within a couple days she would get a new Great Dane puppy and start the process all over again. Losing a loved dog is one of the saddest experiences, and I guess her way of dealing with it was by immediately turning all her attention to the new puppy, all the while knowing that it would have a short life expectancy too.

Oriana:

It's not only that they die so young; it's also that you watch them age. Rather than play with a frisky 5-year-old Husky, for instance, you have to take care of an elderly, dying dog. I simply don't understand it. Or those giant Irish Wolfhounds . . . I saw one that must have been in its old age, and it looked just awful, its large size making a big display canvass for matted fur, difficulty walking, etc.

And then having to dispose of that giant carcass, if the dog dies at home rather than at the vet's.

*

HUMBLE NARCISSISM

~ Who would you rather work for: a narcissistic leader or a humble leader?

The answer is more complicated than you think.

In a Fortune 100 company, researchers studied whether customer service employees were more productive under narcissistic or humble leaders. The least effective bosses were narcissists — their employees were more likely to spend time surfing the Internet and taking long breaks. Employees with humble bosses were a bit more productive: they fielded more customer service calls and took fewer breaks. But the best leaders weren’t humble or narcissistic.

They were humble narcissists.

How can you be narcissistic and humble at the same time? The two qualities sound like opposites, but they can go hand in hand. Narcissists believe they’re special and superior; humble leaders know they’re fallible and flawed. Humble narcissists bring the best of both worlds: they have bold visions, but they’re also willing to acknowledge their weaknesses and learn from their mistakes.

Humble narcissists don’t just have more productive employees — they’re rated as more effective too. It’s not just true in the US: new research also shows that humble narcissists make the best leaders in China. They’re more charismatic, and their companies are more likely to innovate.

Narcissism gives you the confidence to believe you can achieve great things. It’s hard to imagine someone other than Steve Jobs having the grandiose vision of creating Apple. And we’re all drawn to that confidence — it’s why narcissists are more likely to rise up the ranks of the corporate elite and get elected to political office. But alone, narcissism is dangerous. Studies show that tech companies with narcissistic CEOs have more fluctuating, volatile performance. Narcissists tend to be overconfident. They’re prone to dismissing criticism and falling victim to flattery. They surround themselves with yes-men and take unnecessary risks. Also, narcissistic presidents are more likely to engage in unethical behavior and get impeached.

Adding humility prevents capriciousness and complacency. It helps you remember that you’re human. Humble narcissists have grand ambitions, but they don’t feel entitled to them. They don’t deny their weaknesses; they work to overcome them.

As an organizational psychologist, I study leaders and teams, and I’ve been struck that there are three kinds of humility that matter.

The first kind of humility is humility about your ideas. Take Rufus Griscom (TED Talk, given with Alisa Volkman: Let’s talk parenting taboos). When he founded the parenting blog Babble, he did something I’ve never seen an entrepreneur do. He said, “Here are the three reasons you should not invest in my company” — and he walked away with $3.1 million in funding that year. Two years later, he went to pitch Babble to Disney, and he included a slide in his pitch deck that read, “Here are the five reasons you should not buy Babble.” Disney acquired it for $40 million.

By speaking candidly about the downsides of his idea, Rufus made his comments about the upsides more credible. Admitting the flaws outright also made it tougher for investors to come up with their own objections. The harder they had to work to identify what was wrong with the company, the more they thought was right with the company. The conversation changed: his investors proposed solutions to the problems.

If you ever took a debate class, you were taught to identify the weaknesses in your argument and address them out loud. But we forget to do this when we pitch our ideas: we worry that they’re fragile and we don’t want to shoot ourselves in the foot. We overlook the fact that we’ll actually seem more credible and trustworthy — and other people will see more potential in our ideas — if we have the humility to acknowledge their limitations.

Of course, it seems like there are times when this won’t work, like at a job interview. But actually, people are about 30 percent more interested in hiring candidates who answer the question about their greatest weakness honestly, instead of pulling a Michael Scott: “I have weaknesses. I work too hard, and I care too much.” But you might not want to go as far as George Costanza: “I’m unemployed and I live with my parents.”

The second kind of humility is performance humility. It means admitting that we fall short of our goals, we make mistakes, sometimes we even fall flat on our faces. Scientist Melanie Stefan has pointed out that our bios and résumés only highlight only our accomplishments — we scrub out all the stumbles and struggles along the way. In response, a Princeton professor made a failure résumé: a list of all the degree programs that rejected him, all the journals that turned him down, and all the fellowships and awards that he didn’t win. (He has since lamented that it’s gotten more attention than all his academic work combined.)

You might not want to put your failures out there that openly. But every leader can take steps toward showing performance humility. At Facebook, marketing VP Carolyn Everson decided to take her own performance review from her boss and post it in an internal Facebook group for her team — 2,400 people — to read.

Carolyn wanted to signal to them that she isn’t perfect; she’s a work in progress. She figured that if she let people know where she was working to improve, they’d give her better feedback. What she didn’t expect is that her humility would be contagious: other managers started doing it, too, recognizing that it would help to strengthen a culture of learning and development.

That can be true across the hierarchy — not just in leadership, but at the entry level. The evidence is clear: employees who seek negative feedback get better performance reviews. They signal that want to learn, and they put themselves in a stronger position to learn.

The third kind of humility is cultural humility. In many workplaces, there’s a strong focus on hiring people who fit the culture. In Silicon Valley, startups that prize culture fit are significantly less likely to fail and significantly more likely to go public. But post-IPO, they grow at slower rates than firms that hire on skills or potential.

Hiring on culture fit reflects a lack of humility. It suggests that culture is already perfect — all we need to do is bring in people who will perpetuate it. Sociologists find that when we prize culture fit, we end up hiring people who are similar to us. That weeds out diversity of thought and background, and it’s a surefire recipe for groupthink.

Cultural humility is about recognizing that your culture always has room for growth, just like we do. When Larry Page returned as the CEO of Google, he told me that he didn’t want it to become a cultural museum. Great cultures don’t stand still; they evolve.

At the innovative design firm IDEO, instead of cultural fit, they emphasize cultural contribution, a term coined by Diego Rodriguez. The goal isn’t to find and promote people who clone the culture; it’s having the humility to bring in people who will stretch and enrich the culture by adding elements that are absent. That’s something every organization needs to revisit every year, because what’s missing from the culture changes over time.

After IDEO designed the mouse for Apple, they started working on a wider range of projects — from bringing Sesame Street into the digital age to reimagining shopping carts for grocery stores. They realized that while they had great designers, they were short on people who were skilled at going into foreign environments and making sense of them. That’s what anthropologists do for a living, so they created a new job title: anthropologist.

Cultural humility forces you to ask what else is missing. In IDEO’s case, they realized it was storytellers: people gifted in translating new insights back to designers and clients. So they started hiring screenwriters and journalists. The moment you get excited about a new background, a new skill set or a new base of experience is the moment you have to diversify again, and this requires real humility.

Even if you don’t start your career as a narcissist, success can go to your head. Maintaining humility requires you to surround yourself with people who keep you honest, who tell you the truth you may not want to hear but need to hear, and who hold you accountable if you don’t listen to them.

I think that’s what happened to Steve Jobs at Apple. He had the grand ambition to build a great company. But after the launch of the Mac was a flop in 1985, he refused to listen to his critics about what needed to change, and he was forced out of his own company.

I’ve heard from his close collaborators that the Steve Jobs who came back to Apple in 1997 was more humble. Reflecting on the revitalization of the company, he once said, “I’m pretty sure none of this would have happened if I hadn’t been fired from Apple. It was awful-tasting medicine, but I guess the patient needed it.”

That’s what a humble narcissist sounds like:. “I believe I can do extraordinary things, but I always have something to learn.” ~

*

RELIGION AND MENTAL HEALTH

~ It seems that when it comes the mental health, religion is a double-edged sword.

Sigmund Freud described religion as an “obsessive-compulsive neurosis” and Richard Dawkins once also claimed it could qualify as a mental illness.

Studies have shown there is a complex connection between religion and mental issues. A 2014 study found that people who believe in a vengeful or punitive god are more likely to suffer from mental issues such as social anxiety, paranoia, obsessional thinking, and compulsions. According to Dr. Harold Koenig, professor of psychiatry from Duke University’s Medical Center in North Carolina, one-third of psychoses involve religious delusions. The American Psychiatric Association issued a mental health guide for faith leaders to help those preaching the word differentiate between devout belief and dangerous delusion or fundamentalism. The guide includes sections discussing how a person with a mental illness might believe they are receiving a message from a higher power, are being punished, or possessed by evil spirits, and notes the importance of distinguishing whether these are symptoms of a mental disorder or other distressing experience. In May this year a report released as part of the Vietnam Head Injury Study found damage in a certain part of the brain was linked to an increase in religious fundamentalism.

It’s also possible that the beliefs and teachings advocated by a religion for example forgiveness or compassion, can become integrated into the way our brain works, this is because the more that certain neural connections in the brain are used, the stronger they can become. Of course, obviously then the flip-side is true too, and a doctrine that advocates negative beliefs, such as hatred or ostracization of non-believers, or even belief that certain health issues are a ‘punishment’ from a higher power, detrimental effects to an individual’s mental health can occur.

If we take time to consider the connection we can find between religiosity and aspects of mental health we might not immediately consider there are plenty examples to be found. Addictive behaviors are an example. To some a casino is their church, and a recent study from the University of Utah showed that religion can activate the same areas of the brain that respond to drug use, or even other addictive behaviors, like gambling. The ritualized and repetitive nature that draws church-goers to Sunday sermons activates the same areas of the brain that a problem gambler experiences when they play the slot machines.

When it comes to the doctrines themselves, most religions denounce gambling outright. But there are some established links between religion and gambling that may not seem apparent at first. According to research from 2002 cited by Masood Zangeneh of the Center for Research on Inner City Health in Canada, a strong correlation can be found between attending church services and purchasing lottery tickets.

That isn’t to say there isn’t plenty of research that also shows the opposite can be true. Researchers at the University of Missouri reported in 2012 that better mental health is “significantly related to increased spirituality,” regardless of religion. In terms of which religions seem to be the most resistant towards the lures of gambling and other risky behaviors, a 2013 study undertaken in Germany found that Muslims in Germany to be less risk taking in general than Catholics, Protestants, and non-religious people.

A Korean study exploring the relationship between mental health and religiosity provides a good illustration of the duality between the two. The research team’s findings showed that spirituality is most often associated with current episodes of depression, and seems to suggest that individuals with currently experiencing depressive symptoms have a stronger tendency to place importance on spiritual values.

In other words, a depressive episode often motivates patients to seek out religion as a way of coping with their illness. Several studies have suggested that religious activities, such as worship attendance, may play a role in combating depression, in part thanks to the community aspect and the extended support networks which worship attendance provides. Social support accounts for about 20-30 percent of the measured benefits. The rest comes from aspects such as the sort of self-discipline encouraged by religious faith, and the optimistic worldview that it can support.

Likewise, a study from March this year showed that those who held devout religious beliefs were less afraid of death than those with uncertain ones. Interestingly, devout atheists also held little anxiety about death and the after-life.

There is other evidence to suggest that spirituality benefits mental health. Focusing on spiritual and religious practices such as meditation or community service in contrast to a focusing on materialism can contribute to feeling more fulfilled and satisfied in everyday life.

It seems that while there are some negative links between religion and mental illness, there’s no evidence to support categorizing it as a disorder, regardless of Freud’s opinion on the matter.

Oriana:

My mental health improved after I stopped going to church at 14. I ceased to worry about being a worthless sinner destined for hell. I never saw god as good; he was a god of judgment and vengeance, extending to eternal damnation.

According to what I've read, only about a quarter of Christians believe in a benevolent god. I wasn't in this happy minority, and worried that my inability to love god means automatic assignment to eternal damnation.

This focus on sin and damnation was quite oppressive. I ceased to believe in spring, when lilacs were in bloom and birds were singing. It was a rebirth for me too.

Mary:

St. Mary's basilica, Kraków

*

YUVAL HARRARI: LESSONS LEARNED FROM A YEAR OF COVID

~ How can we summarize the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge.

Why, then, has there been so much death and suffering? Because of bad political decisions.

In previous eras, when humans faced a plague such as the Black Death, they had no idea what caused it or how it could be stopped. When the 1918 influenza struck, the best scientists in the world couldn’t identify the deadly virus, many of the countermeasures adopted were useless, and attempts to develop an effective vaccine proved futile.

It was very different with Covid-19. The first alarm bells about a potential new epidemic began sounding at the end of December 2019. By January 10 2020, scientists had not only isolated the responsible virus, but also sequenced its genome and published the information online. Within a few more months it became clear which measures could slow and stop the chains of infection. Within less than a year several effective vaccines were in mass production. In the war between humans and pathogens, never have humans been so powerful.

Moving life online

Alongside the unprecedented achievements of biotechnology, the Covid year has also underlined the power of information technology. In previous eras humanity could seldom stop epidemics because humans couldn’t monitor the chains of infection in real time, and because the economic cost of extended lockdowns was prohibitive. In 1918 you could quarantine people who came down with the dreaded flu, but you couldn’t trace the movements of pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic carriers. And if you ordered the entire population of a country to stay at home for several weeks, it would have resulted in economic ruin, social breakdown and mass starvation. In contrast, in 2020 digital surveillance made it far easier to monitor and pinpoint the disease vectors, meaning that quarantine could be both more selective and more effective. Even more importantly, automation and the internet made extended lockdowns viable, at least in developed countries.

While in some parts of the developing world the human experience was still reminiscent of past plagues, in much of the developed world the digital revolution changed everything. Consider agriculture. For thousands of years food production relied on human labour, and about 90 per cent of people worked in farming. Today in developed countries this is no longer the case. In the US, only about 1.5 per cent of people work on farms, but that’s enough not just to feed everyone at home but also to make the US a leading food exporter. Almost all the farm work is done by machines, which are immune to disease. Lockdowns therefore have only a small impact on farming.

Imagine a wheat field at the height of the Black Death. If you tell the farmhands to stay home at harvest time, you get starvation. If you tell the farmhands to come and harvest, they might infect one another. What to do? Now imagine the same wheat field in 2020. A single GPS-guided combine can harvest the entire field with far greater efficiency — and with zero chance of infection. While in 1349 an average farmhand reaped about 5 bushels per day, in 2014 a combine set a record by harvesting 30,000 bushels in a day. Consequently Covid-19 had no significant impact on global production of staple crops such as wheat, maize and rice.

To feed people it is not enough to harvest grain. You also need to transport it, sometimes over thousands of kilometers. For most of history, trade was one of the main villains in the story of pandemics. Deadly pathogens moved around the world on merchant ships and long-distance caravans. For example, the Black Death hitchhiked from east Asia to the Middle East along the Silk Road, and it was Genoese merchant ships that then carried it to Europe. Trade posed such a deadly threat because every wagon needed a wagoner, dozens of sailors were required to operate even small seagoing vessels, and crowded ships and inns were hotbeds of disease.

In 2020, global trade could go on functioning more or less smoothly because it involved very few humans. A largely automated present-day container ship can carry more tons than the merchant fleet of an entire early modern kingdom. In 1582, the English merchant fleet had a total carrying capacity of 68,000 tons and required about 16,000 sailors. The container ship OOCL Hong Kong, christened in 2017, can carry some 200,000 tons while requiring a crew of only 22. True, cruise ships with hundreds of tourists and airplanes full of passengers played a major role in the spread of Covid-19. But tourism and travel are not essential for trade. The tourists can stay at home and the business people can Zoom, while automated ghost ships and almost human-less trains keep the global economy moving. Whereas international tourism plummeted in 2020, the volume of global maritime trade declined by only 4 per cent.

Automation and digitalization have had an even more profound impact on services. In 1918, it was unthinkable that offices, schools, courts or churches could continue functioning in lockdown. If students and teachers hunker down in their homes, how can you hold classes? Today we know the answer. The switch online has many drawbacks, not least the immense mental toll. It has also created previously unimaginable problems, such as lawyers appearing in court as cats. But the fact that it could be done at all is astounding. In 1918, humanity inhabited only the physical world, and when the deadly flu virus swept through this world, humanity had no place to run. Today many of us inhabit two worlds — the physical and the virtual. When the coronavirus circulated through the physical world, many people shifted much of their lives to the virtual world, where the virus couldn’t follow.

Of course, humans are still physical beings, and not everything can be digitalized. The Covid year has highlighted the crucial role that many low-paid professions play in maintaining human civilization: nurses, sanitation workers, truck drivers, cashiers, delivery people. It is often said that every civilization is just three meals away from barbarism. In 2020, the delivery people were the thin red line holding civilization together. They became our all-important lifelines to the physical world.

THE INTERNET HOLDS ON

As humanity automates, digitalizes and shifts activities online, it exposes us to new dangers. One of the most remarkable things about the Covid year is that the internet didn’t break. If we suddenly increase the amount of traffic passing on a physical bridge, we can expect traffic jams, and perhaps even the collapse of the bridge. In 2020, schools, offices and churches shifted online almost overnight, but the internet held up. We hardly stop to think about this, but we should.

After 2020 we know that life can go on even when an entire country is in physical lockdown. Now try to imagine what happens if our digital infrastructure crashes. Information technology has made us more resilient in the face of organic viruses, but it has also made us far more vulnerable to malware and cyber warfare. People often ask: “What’s the next Covid?” An attack on our digital infrastructure is a leading candidate. It took several months for coronavirus to spread through the world and infect millions of people. Our digital infrastructure might collapse in a single day. And whereas schools and offices could speedily shift online, how much time do you think it will take you to shift back from email to snail-mail? What counts?

The Covid year has exposed an even more important limitation of our scientific and technological power. Science cannot replace politics. When we come to decide on policy, we have to take into account many interests and values, and since there is no scientific way to determine which interests and values are more important, there is no scientific way to decide what we should do. For example, when deciding whether to impose a lockdown, it is not sufficient to ask: “How many people will fall sick with Covid-19 if we don’t impose the lockdown?”

We should also ask: “How many people will experience depression if we do impose a lockdown? How many people will suffer from bad nutrition? How many will miss school or lose their job? How many will be battered or murdered by their spouses?” Even if all our data is accurate and reliable, we should always ask: “What do we count? Who decides what to count? How do we evaluate the numbers against each other?” This is a political rather than scientific task. It is politicians who should balance the medical, economic and social considerations and come up with a comprehensive policy.

Similarly, engineers are creating new digital platforms that help us function in lockdown, and new surveillance tools that help us break the chains of infection. But digitalization and surveillance jeopardize our privacy and open the way for the emergence of unprecedented totalitarian regimes. In 2020, mass surveillance has become both more legitimate and more common. Fighting the epidemic is important, but is it worth destroying our freedom in the process? It is the job of politicians rather than engineers to find the right balance between useful surveillance and dystopian nightmares.

Basic rules can go a long way in protecting us from digital dictatorships, even in a time of plague. First, whenever you collect data on people — especially on what is happening inside their own bodies — this data should be used to help these people rather than to manipulate, control or harm them. My personal physician knows many extremely private things about me. I am OK with it, because I trust my physician to use this data for my benefit. My physician shouldn’t sell this data to any corporation or political party. It should be the same with any kind of “pandemic surveillance authority” we might establish.

POLITICS

The unprecedented scientific and technological successes of 2020 didn’t solve the Covid-19 crisis. They turned the epidemic from a natural calamity into a political dilemma. When the Black Death killed millions, nobody expected much from the kings and emperors. About a third of all English people died during the first wave of the Black Death, but this did not cause King Edward III of England to lose his throne. It was clearly beyond the power of rulers to stop the epidemic, so nobody blamed them for failure. But today humankind has the scientific tools to stop Covid-19. Several countries, from Vietnam to Australia, proved that even without a vaccine, the available tools can halt the epidemic. These tools, however, have a high economic and social price. We can beat the virus — but we aren’t sure we are willing to pay the cost of victory. That’s why the scientific achievements have placed an enormous responsibility on the shoulders of politicians.

Unfortunately, too many politicians have failed to live up to this responsibility. For example, the populist presidents of the US and Brazil played down the danger, refused to heed experts and peddled conspiracy theories instead. They didn’t come up with a sound federal plan of action and sabotaged attempts by state and municipal authorities to halt the epidemic. The negligence and irresponsibility of the Trump and Bolsonaro administrations have resulted in hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths. In the UK, the government seems initially to have been more preoccupied with Brexit than with Covid-19. For all its isolationist policies, the Johnson administration failed to isolate Britain from the one thing that really mattered: the virus. My home country of Israel has also suffered from political mismanagement. As is the case with Taiwan, New Zealand and Cyprus, Israel is in effect an “island country”, with closed borders and only one main entry gate — Ben Gurion Airport. However, at the height of the pandemic the Netanyahu government has allowed travelers to pass through the airport without quarantine or even proper screening and has neglected to enforce its own lockdown policies.

Both Israel and the UK have subsequently been in the forefront of rolling out the vaccines, but their early misjudgments cost them dearly. In Britain, the pandemic has claimed the lives of 120,000 people, placing it sixth in the world in average mortality rates. Meanwhile, Israel has the seventh highest average confirmed case rate, and to counter the disaster it resorted to a “vaccines for data” deal with the American corporation Pfizer. Pfizer agreed to provide Israel with enough vaccines for the entire population, in exchange for huge amounts of valuable data, raising concerns about privacy and data monopoly, and demonstrating that citizens’ data is now one of the most valuable state assets.

While some countries performed much better, humanity as a whole has so far failed to contain the pandemic, or to devise a global plan to defeat the virus. The early months of 2020 were like watching an accident in slow motion. Modern communication made it possible for people all over the world to see in real time the images first from Wuhan, then from Italy, then from more and more countries — but no global leadership emerged to stop the catastrophe from engulfing the world. The tools have been there, but all too often the political wisdom has been missing.

One reason for the gap between scientific success and political failure is that scientists co-operated globally, whereas politicians tended to feud. Working under much stress and uncertainty, scientists throughout the world freely shared information and relied on the findings and insights of one another. Many important research projects were conducted by international teams. For example, one key study that demonstrated the efficacy of lockdown measures was conducted jointly by researchers from nine institutions — one in the UK, three in China, and five in the US. In contrast, politicians have failed to form an international alliance against the virus and to agree on a global plan. The world’s two leading superpowers, the US and China, have accused each other of withholding vital information, of disseminating disinformation and conspiracy theories, and even of deliberately spreading the virus. Numerous other countries have apparently falsified or withheld data about the progress of the pandemic.

The lack of global co-operation manifests itself not just in these information wars, but even more so in conflicts over scarce medical equipment. While there have been many instances of collaboration and generosity, no serious attempt was made to pool all the available resources, streamline global production and ensure equitable distribution of supplies. In particular, “vaccine nationalism” creates a new kind of global inequality between countries that are able to vaccinate their population and countries that aren’t. It is sad to see that many fail to understand a simple fact about this pandemic: as long as the virus continues to spread anywhere, no country can feel truly safe. Suppose Israel or the UK succeeds in eradicating the virus within its own borders, but the virus continues to spread among hundreds of millions of people in India, Brazil or South Africa. A new mutation in some remote Brazilian town might make the vaccine ineffective, and result in a new wave of infection. In the present emergency, appeals to mere altruism will probably not override national interests.

However, in the present emergency, global co-operation isn’t altruism. It is essential for ensuring the national interest. Arguments about what happened in 2020 will reverberate for many years. But people of all political camps should agree on at least three main lessons. First, we need to safeguard our digital infrastructure. It has been our salvation during this pandemic, but it could soon be the source of an even worse disaster. Second, each country should invest more in its public health system. This seems self-evident, but politicians and voters sometimes succeed in ignoring the most obvious lesson. Third, we should establish a powerful global system to monitor and prevent pandemics. In the age-old war between humans and pathogens, the frontline passes through the body of every human being. If this line is breached anywhere on the planet, it puts all of us in danger. Even the richest people in the most developed countries have a personal interest to protect the poorest people in the least developed countries. If a new virus jumps from a bat to a human in a poor village in some remote jungle, within a few days that virus can take a walk down Wall Street.

Many people fear that Covid-19 marks the beginning of a wave of new pandemics. But if the above lessons are implemented, the shock of Covid-19 might actually result in pandemics becoming less common. Humankind cannot prevent the appearance of new pathogens. This is a natural evolutionary process that has been going on for billions of years, and will continue in the future too. But today humankind does have the knowledge and tools necessary to prevent a new pathogen from spreading and becoming a pandemic. If Covid-19 nevertheless continues to spread in 2021 and kill millions, or if an even more deadly pandemic hits humankind in 2030, this will be neither an uncontrollable natural calamity nor a punishment from God. It will be a human failure and — more precisely — a political failure. ~

https://www.ft.com/content/f1b30f2c-84aa-4595-84f2-7816796d6841

WHAT MOVES US ALWAYS COMES FROM WHAT IS HIDDEN

We are all a sun-lit moment

come from a long darkness;

what moves us always

comes from what is hidden,

what seems to be said

so suddenly,

has lived in the body

for a long, long time.

~ David Whyte

No comments:

Post a Comment