*

THE OTHER ONE

We meet between no and yes.

She has my voice, my face,

my shadow interrupting

moon-shadow of the blinds.

My dreams belong to her,

the one who stayed behind —

who’ll ride Warsaw streetcars

until the end of time.

The one who married someone else,

the one who had a child —

the one who said,

Why should I sacrifice for art?

She’s been to China

and the Himalayas; divorced

a linguist, met a shaman;

raised a red-haired son.

I show her my rejection slips,

petals from flowers of despair;

ghost children reach toward me

with their unborn arms.

On sleepless nights we hold

our separate ceremonies of regret.

If only we could slip

into each other’s lives,

and close the blinds —

But she’d find my

staring at the wall, fine-tuning

words, no life at all —

she’d rather bathe a baby,

soap the slippery small body.

On milky California mornings

I read and scribble,

sipping hot cocoa as in childhood;

she rushes about the kitchen

before going to work —

suddenly stops, unravels in hoarse sobs.

Mostly we walk the opposite way,

wearing our choices

like a coat of fog.

I’d like to stop her, give her

the black silk rose from Antonina’s hat,

our great-grandmother —

iron lips of a general, the burning

eyes of a heretic or saint.

Will we ever sit together,

I and I, my other one?

When will we speak at last

of all that hasn’t happened?

But she’s more and more

difficult to see, a figure in the crowd,

her footsteps the long dying echoes

on the other side of time.

~ Oriana

Mary:

I think we all may have moments in our pasts where a decision made, for any reason, usually for many reasons, as so much is overdetermined, becomes a sort of crossroads, where we split off from one possible future and move into another, like the idea that every decision splits off into different universes. And we wonder later, and forever, what our life would have been if we had decided otherwise. For me that decision was my move from academia, not completing my PhD...leaving the world of the university and going to nursing school. It was the most radical change in direction I ever made.

Sometimes I wonder what that other life would have been like, but I cant say I longed to return to it, or regretted leaving it. I think my father did though. I think he felt it was a tragedy, that I lost out on having a better life. Not that he valued the academic world that much in itself really, I think in his mind it was of a higher class, a higher status than any work done with your hands, including nursing. He did see intellectual pretension for what it was, basically bullshit...but there still was that sense of that world being higher class, less difficult, less painful, less of a struggle.

Anyway, I like the poem and I like the direction that ending takes: that the imaginary other that might have been, becomes less powerful, vaguer, fades away like the ghost that she is...the choice you didn't make, the road not taken. After all, there is nothing that says that life would have been better, finer, more interesting...there is no way to know what it would have been, whether any of it would have happened as you suppose it might.

Pursuing that ghost is a bit of self torture, where you assume your decision is one you should regret, long after there's any possibility of changing or reversing its effects. I think this is where forgiveness helps...forgive the girl you were and the woman she became. Forgive also the other woman that girl may have become had you not made the choice you did. I think the way you have her suddenly weep in the poem demonstrates your knowledge and admission that either choice leads to both joys and grief, that either choice leads to a rich life, the riches are simply different.

Oriana:

Yes, I can see how shifting away from a PhD program into nursing was huge for you — and how for a while at least one can’t stop imagining that other potential life. For me that was of course coming to the US, bitterly regretting it at times. And yet I also have the strange feeling that had I stayed, I would have died young, hit by a streetcar, perhaps — some idiotic death like that. As if the US didn’t provide the opportunity for being a victim of a senseless shooting — even before the terrorist attacks began for real.

In a way, I did die young — that part of me that didn't yet experience the shattering of my own American dream. Or, to change perspectives, that alternate self that would have had a ball studying in Warsaw, electrified by the city's supercharged intellectual and artistic atmosphere.

A few people have asked, “But if you stayed, would you have become a poet?” I didn’t really “choose” becoming a poet — no poets do; but like practically all poets I had a load of doubt and guilt about spending time perfecting lines (“The Other One” addresses that particular guilt). Was there any time when I didn’t think I was wasting my life, my mind, my education? After all, poetry's audience is so tiny. And of course it didn’t help to hear some people say things like, “Why would you limit your life like that?”

During my stints as an instructor and a free-lance writer, I didn't experience the guilt — and only one poet friend suggested that I was wasting my talent.

At least as a nurse you never needed to doubt your usefulness. You were helping save lives.

Yet now and then I had those moments of grace when someone in the audience strongly reacted to either the beauty or the insight in a poem of mine. Someone needed to hear even just that one line. I was giving readings thinking of that one single person in the audience.

Another painful “splitting off” came when I decided not to have a child. It was an agonizing choice because I had no doubt that having a child would be a great adventure, and can’t forget how one woman doctor told me, “You’d be a fun mother to have.” I didn’t doubt that either. What fun it would be to read at bedtime, to take my child to museums, to the planetarium, or simply to point out Jupiter and Orion in the night sky — to be the child’s first teacher.

I was aware, of course, that this pleasure came at a high cost of handling a lot of chores and stress all by myself (grandmothers weren't available, and no, there were no resources to hire a helper). What helped me decide was reading an article in a women’s magazine (ah, the much mocked women’s magazines! But now and then, life-saving wisdom) that enumerated the conditions under which a woman should not have a child, starting with the obvious: a genetic disease, and ending with “if your work requires a great amount of solitude and quiet.”

I experienced an instant relief: because of the devouring nature of poetry, I was released from an equally devouring duty. Still, it turned out to be impossible not to imagine the other way. But futile. Just creating an imaginary ghost. As if there weren’t already too many real ghosts, meaning our memories of the dead, clanking the chains of our regrets that we weren’t kinder, more generous with affection.

Now we the survivors can only “give forward” to the living. That has become one of my chief commandments. That, combined with the knowledge that (extremes aside), nothing is all good or all bad, supported by more specific specifics such as, “You don’t change men, you change problems.”

And of course I can’t forget the only Buddhist wisdom that ever helped me: “That person makes you suffer because you WANT something from that person.” Or, if it’s not someone but something, remember what my mother taught me, “Immediately tell yourself, “That’s not for me, that’s not for me.” Except that of course one needs the wisdom of knowing when to persist and when to let go. That’s lifelong learning, and even so, after a lifetime of learning from mistakes, you’ll make more mistakes. Forgive yourself in advance.

But why am I suddenly trying to convey, in such compressed form, so much of what I have slowly learned? Am I on the eve of the final departure? Only in the sense that we all are. I think it’s something about one year ending and another beginning. May the blessings of 2021 outweigh its sorrows.

The planet Venus, also known as both the Morning Star and the Evening Star. How amazing that we now have such images!

*

“The first and primary act of the poetic imagination is to create the person who will write the poems. The persona you create is a projection of your daily self, inseparable from it, but significantly greater, more purposeful. If you live intensely enough, at the center of your being, you will eventually become that other. Survival depends on self-renewal.” ~ Stanley Kunitz

Oriana:

I took the name “Oriana” (the rising sun, or, in Buddhism, the “rising mind”) in part to gain that greater self, a poet self. For a while, Oriana was indeed dominant. But the ghost double was all too vivid: the woman who stayed behind, avoiding the trauma of becoming an immigrant, yet showing her spirit by reaching for her her (i.e. mine) young dreams — seeing the Himalayas, meeting a shaman (the Amazon jungle was another dream). The woman who no doubt had a professional career and published in her field, and who also knew the warmth and fulfillment of a normal family life. At the same time she had the courage to get a divorce when needed (interesting that I had to make her a single woman after all). Still, in the poem, the poet persona prevails, making the double sob over her suppressed creative side.

Life, of course, proceeded to happen, as usual, while I was making other plans. But let me not lament — I’ve done it more than enough while in severe depression. Ultimately I revived in yet another format, so to speak. I count my blessings.

Oriana:

Life is perverse that way. Always regrets. But more often over not having acted. Not having taken that opportunity. At least it would have been an adventure.

*

The risk of a wrong decision is preferable to the terror of indecision. ~ Maimonides

Statue of Maimonides in Cordoba

*

THE GREAT GATSBY AS A NOVEL OF IDEAS: THE “AMERICAN DREAM”

~ I have read The Great Gatsby four times. Only in this most recent time did I choose to attack it in a single sitting. I’m an authority now. In one day, you can sit with the brutal awfulness of nearly every person in this book—booooo, Jordan; just boo. And Mr. Wolfsheim, shame on you, sir; Gatsby was your friend. In a day, you no longer have to wonder whether Daisy loved Gatsby back or whether “love” aptly describes what Gatsby felt in the first place. After all, The Great Gatsby is a classic of illusions and delusions.

In a day, you reach those closing words about the boats, the current, and the past, and rather than allow them to haunt, you simply return to the first page and start all over again. I know of someone—a well-heeled white woman in her midsixties—who reads this book every year. What I don’t know is how long it takes her. What is she hoping to find? Whether Gatsby strikes her as more cynical, naive, romantic, or pitiful? After decades with this book, who emerges more surprised by Nick’s friendship with Gatsby? The reader or Nick?

In this way, The Great Gatsby achieves hypnotic mystery. Who are any of these people—Wilson the mechanic or his lusty, buxom, doomed wife, Myrtle? Which feelings are real? Which lies are actually true? How does a story that begins with such grandiloquence end this luridly? Is it masterfully shallow or an express train to depth? It’s a melodrama, a romance, a kind of tragedy. But mostly it’s a premonition.

Each time, its fineness announces itself on two fronts. First, as writing. Were you to lay this thing out by the sentence, it’d be as close as an array of words could get to strands of pearls. “The cab stopped at one slice in a long white cake of apartment-houses”? That line alone is almost enough to make me quit typing for the rest of my life.

The second front entails the book’s heartlessness. It cuts deeper every time I sit down with it. No one cares about anyone else. Not really. Nick’s affection for Gatsby is entirely posthumous. Tragedy tends to need some buildup; Fitzgerald dunks you in it. The tragedy is not that usual stuff about love not being enough or arriving too late to save the day. It’s creepier and profoundly, inexorably true to the spirit of the nation. This is not a book about people, per se. Secretly, it’s a novel of ideas.

Gatsby meets Daisy when he’s a broke soldier and senses that she requires more prosperity, so five years later he returns as almost a parody of it. The tragedy here is the death of the heart, capitalism as an emotion. We might not have been ready to hear that in 1925, even though the literature of industrialization demanded us to notice. The difference between Fitzgerald and, say, Upton Sinclair, who wrote, among other tracts, The Jungle, is that Sinclair was, among many other things, tagged a muckraker and Fitzgerald was a gothic romantic, of sorts. Nonetheless, everybody’s got coins in their eyes.

This is to say that the novel may not make such an indelible first impression. It’s quite a book. But nothing rippled upon its release in 1925. The critics called it a dud! I know what they meant. This was never my novel. It’s too smooth for tragedy, underwrought. Yet I, too, returned, seduced, eager to detect. What—who?—have I missed? Fitzgerald was writing ahead of his time. Makes sense. He’s made time both a character in the novel and an ingredient in the book’s recipe for eternity. And it had other plans. The dazzle of his prose didn’t do for people in 1925 what it’s done for everybody afterward. The gleam seemed flimsy at a time when a reader was still in search of writing that seeped subcutaneously.

The twenties were a drunken, giddy glade between mountainous wars and financial collapse. By 1925, they were midroar. Americans were innovating and exploring. They messed around with personae. Nothing new there. American popular entertainment erupted from that kind of messy disruption of the self the very first time a white guy painted his face black. By the twenties, Black Americans were messing around, too. They were as aware as ever of what it meant to perform versions of oneself—there once were Black people who, in painting their faces black, performed as white people performing them. So this would’ve been an age of high self-regard. It would have been an age in which self-cultivation construes as a delusion of the American dream. You could build a fortune, then afford to build an identity evident to all as distinctly, keenly, robustly, hilariously, terrifyingly, alluringly American. Or the inverse: the identity is a conjurer of fortune.

This is the sort of classic book that you didn’t have to be there for. Certain people were living it. And Fitzgerald had captured that change in the American character: merely being oneself wouldn’t suffice. Americans, some of them, were getting accustomed to the performance of oneself. As Gatsby suffers at Nick’s place during his grand reunion with Daisy, he’s propped himself against the mantle “in a strained counterfeit of perfect ease, even of boredom.” (He’s actually a nervous wreck.) “His head leaned back so far that it rested against the face of a defunct mantelpiece clock.” Yes, even the clock is in on the act, giving a performance as a timepiece.

So again: Why this book—for ninety-six years, over and over? Well, the premonition about performance is another part of it, and to grasp that, you probably did have to be there in 1925. Live performance had to compete with the mechanical reproduction of the moving image. You no longer had to pay for one-night-only theater when a couple times a day you could see people on giant screens, acting like people. They expressed, gestured, pantomimed, implied, felt. Because they couldn’t yet use words—nobody talked until 1927 and, really, that was in order to sing—the body spoke instead. Fingers, arms, eyes. The human gist rendered as bioluminescence. Often by people from the middle of nowhere transformed, with surgery, elocution classes, a contract, and a plainer, Waspier name, into someone new. So if you weren’t reinventing yourself, you were likely watching someone who had been reinvented.

The motion picture actually makes scant appearances in this book but it doesn’t have to. Fitzgerald was evidently aware of fame. By the time The Great Gatsby arrived, he himself was famous. And in its way, this novel (his third) knows the trap of celebrity and invents one limb after the next to flirt with its jaws. If you’ve seen enough movies from the silent era or what the scholars call the classical Hollywood of the thirties (the very place where Fitzgerald himself would do a stint), it’s possible to overlook the glamorous phoniness of it all. It didn’t seem phony at all. It was mesmerizing. Daisy mesmerized Gatsby. Gatsby mesmerized strangers. Well, the trappings of his Long Island mansion in East Egg, and the free booze, probably had more to do with that. He had an aura of affluence. And incurs some logical wonder about this fortune: How? Bootlegger would seem to make one only so rich.

A third of the way into the book, Nick admits to keeping track of the party people stuffed into and spread throughout Gatsby’s mansion. And the names themselves constitute a performance: “Of theatrical people there were Gus Waize and Horace O’Donavan and Lester Meyer and George Duckweed and Francis Bull,” Nick tells us. “Also from New York were the Chromes and the Backhyssons and the Dennickers and Russel Betty and the Corrigans and the Kellehers and the Dewars and the Scullys.” There’s even poor “Henry L. Palmetto, who killed himself by jumping in front of a subway train in Times Square.” This is a tenth of the acrobatic naming that occurs across a mere two pages, and once Fitzgerald wraps things up, you aren’t at a party so much as a movie-premiere after-party.

Daisy’s not at Gatsby’s this particular night, but she positions herself like a starlet. There’s a hazard to her approximation of brightness and lilt. We know the problem with this particular star: She’s actually a black hole. Her thick, strapping, racist husband, Tom, enjoys playing his role as a boorish cuckold-philanderer. Jordan is the savvy, possibly kooky, best friend, and Nick is the omniscient chum. There’s something about the four and sometimes five of them sitting around in sweltering rooms, bickering and languishing, that predicts hours of the manufactured lassitude we call reality TV. Everybody here is just as concocted, manifested. And Gatsby is more than real—and less. He’s symbolic. Not in quite the mode of one of reality’s most towering edifices, the one who became the country’s forty-fifth president. But another monument, nonetheless, to the peculiar tackiness of certain wealth dreams. I believe it was Fran Lebowitz who called it. Forty-five, she once said, is “a poor person’s idea of a rich person.” And Gatsby is the former James Gatz’s idea of the same.

Maybe we keep reading this book to double-check the mythos, to make sure the chintzy goose on its pages is really the golden god of our memories. It wasn’t until reading it for the third time that I finally was able to replace Robert Redford with the blinkered neurotic that Leonardo DiCaprio made of Gatsby in the Baz Luhrmann movie adaptation of the book. Nick labels Gatsby’s manner punctilious. Otherwise, he’s on edge, this fusion of suavity, shiftiness, and shadiness. Gatsby wavers between decisiveness and its opposite. On a drive with Nick where Gatsby starts tapping himself “indecisively” on the knee. A tic? A tell? Well, there he is about to lie, first about having been “educated at Oxford.” Then a confession of all the rest: nothing but whoppers, and a tease about “the sad thing that happened to me”—self-gossip. Listening to Gatsby’s life story is, for Nick, “like skimming hastily through a dozen magazines.”

This is a world where “anything can happen”—like the fancy car full of Black people that Nick spies on the road (“two bucks and a girl,” in his parlance) being driven by a white chauffeur. Anything can happen, “even Gatsby.” (Especially, I’d say.) Except there’s so much nothing. Here is a book whose magnificence culminates in an exposé of waste—of time, of money, of space, of devotion, of life. There is death among the ash heaps in the book’s poor part of town. Jordan Baker is introduced flat out on a sofa “with her chin raised a little, as if she were balancing something on it which was quite likely to fall.” It’s as likely to be an actual object as it is the idea of something else: the precarious purity of their monotonous little empire.

We don’t know who James Gatz from Minnesota is before he becomes Jay Gatsby from Nowhere. “Becomes”—ha. Too passive. Gatsby tosses Gatz overboard. For what, though? A girl, he thinks. Daisy. A daisy. A woman to whom most of Fitzgerald’s many uses of the word murmur are applied. But we come back to this book to conclude her intentions, to rediscover whether Gatsby’s standing watch outside her house after a terrible night portends true love and not paranoid obsession.

And okay, if it is obsession, is it at least mutual? That’s a question to think about as you start to read this thing, whether for the first or fifty-first time. Daisy is this man’s objective, but she’s the wrong fantasy. It was never her he wanted. Not really. It was America. One that’s never existed. Just a movie of it. America. ~

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2021/01/11/why-do-we-keep-reading-the-great-gatsby/?fbclid=IwAR1z_zf5xZIaVWin6q8_OPy9azn6rV3JHKgtJOBp1kO1VyrHk5InbGAqLx8

Oriana:

I thought the writing was a tad overloaded with symbolism. But it's certainly a memorable American dream story, and Nick's narration is the perfect framing.

Not that Nick is a saint (e.g. his anti-Semitism, probably “natural” during the nineteen twenties). He too is a product of his era and his social class — but he has a heart and a conscience, and is aware of his privilege. He can see dishonesty and pretense. It may be hard to sympathize with Gatsby himself because of his deluded obsession with gaining wealth in order to gain (“buy” might be a more precise word) Daisy and all she symbolizes. Fortunately, it feels natural to trust Nick. And in a novel full of mere appearances, we simply must have at least one person we can trust.

And of course there's that tell-all line about Daisy's voice (compressed here): “Her voice was full of money.”

Mary:

In the discussion of Gatsby the American Dream is described as a process of invention and performance. It is not enough to simply "be yourself" in this world where everything is more mythology and performance than fact and action. Here you are free to recreate yourself for an audience of actors and poseurs, who have done the same..life becomes a movie set, each character in their chosen role. Truth and integrity grow slippery and thin, and finally irrelevant.

It's eerie how apt this seems for our current situation, where the unreality of "reality TV" has replaced our apprehension of the world so completely it seems there is no bedrock of fact beneath all the invented scripts, one chooses whatever "alternate facts" fit their script, then "performs" ones life, taking selfies and waiting for applause. When it's all performance nothing seems particularly serious, so a treasonous mob can attempt a coup, violating laws, causing mayhem, even murder, with a sort of crazy glee, like misbehaving adolescents, full of their own daring and not expecting any serious consequences. If it's all performance you need take no responsibility, fear no real punishment, and, why not, take lots of pictures and videos with no thought of self incrimination...only the bragging rights and upvotes from an audience you'll impress.

This world becomes increasingly surreal, capricious, violent and inhumane. If everyone's an actor and life a performance, if the goal is to be a great star, with the constant adulation of an audience, truth, reason, empathy, responsibility, ethical behavior all become not only unnecessary, but actual roadblocks to the success of the performance. The Star is a supreme narcissist, the world a stage for his performance. This is Trump and his "American Dream”… certainly an extreme, but also part of what has been here for a long time. His style is very much that " poor man's idea of a rich person," vulgar and off the mark, gilded and ostentatious, hilariously wrong....think of the golden toilet. He fits with the American adulation of the wealthy, and is supremely concerned with his concocted image, inventing lie after lie to "look good," and impress the audience. Nothing matters more than how things look.

On the plus side, we can also choose an identity and performance that is better than this. Better than ego and entertainment, insisting on fact and evidence, and with a script whose stars are the ordinary people, no longer consigned roles as extras and shifted instead to the center stage. Right now, with the sickening destruction visible and in the open, we have the opportunity to retake the stage, rewrite the script, re-affirm the principles and structure of democracy, turn the tide on the trend toward autocracy in our own nation, become again a leader in the world.

THE GOLDEN LOCKET (Joseph Milosch remembers the day Trump became president)

On the night Donald Trump became president, I walked to an Ethiopian pizza parlor in Normal Heights. Streetlights made the street appear as if it rained. As I reached the parlor’s door, the traffic light turned red, giving the crimson-brick building an angry look. Inside, I sat by one a large window. As I waited, I studied the eatery’s Roman-styled arches, then a mural of an African sunset.

Above it, a television set delivered the news. As I ate, I watched two elderly women in lavender blouses. They cried as the news woman gloated over Trump’s victory. I couldn’t console them, and my pizza lost its flavor. After, they left, I placed the memory of those woman in a gold locket. Storing it in the pantry of my heart, I took it everywhere with me ― to ballgames ― picnics ― and the island off the west coast of Ireland.

On a rainy morning, I rode the ferry and hired a horse-drawn cart. My guide, a retired merchant-marine drove around the island. He stopped at the rusted hull of a ship grounded on the rocky shore. “In ’42 the Nazis ran it a shore,” he said, knocking his pipe against the cart’s dashboard. Up the hill and to left, he stopped by a church. “The British blew it to bits,” he said, “Cromwell thought he could enslave us, but we got the last laugh.”

Down the lane, he stopped and said, “That place over there is still farmed the old way. By hand.” Then, he spit downwind. As he drove, he talked mostly about his horses. “The male’s name is Blackie,” he said pointing at the white horse. “And the other, her name is Not-so,” he’d shortened it from Not-so Black. She was a roan and both were Belgium draft-horses. “Blackie is the lazy one,” he said, and to prove his point he clucked “Up. Up.”

“No-so is the worker,” and he slapped her rump with his whip. That’s how the early morning went. He told me nothing else about the island as he coddled Blackie and lashed Not-so. After the tour, I paid him and went into a pastry shop. After buying a donut and coffee, I walked to the pier, sat on a concrete bench and watched the cloud cover break apart. The sun warmed the day and made the white caps sparkle.

Watching the ships follow ancient trade routes, I thought at this very moment it is almost possible to believe the past is contained in the rusted hull of a ship or in a disemboweled church. Surrounded by the music of the waves rocking the moored ships ― the music of their creaking chains, I could almost believe in my country. Except for a memory captured in a gold locket, I could almost believe.

But I couldn’t forget the two women crying as the news of a reinvigorated hatred descended like a menacing fog over the heart of my country.

Oriana:

Thank you, Joe, for sharing those memories. I know I felt devastated and had strange nightmares for weeks. I was posting a lot of art, hoping beauty could detox the deep grief of those of us who were mourning. But ultimately only another election could undo the pain. It’s been the longest four years . . . But now, at last, a president who is a normal human being, so normal that many say it’s going to be boring . . . and boring never felt so good and reassuring.

*

THE AMERICAN ADAM

~ The fundamental myth at hand, that of the authentic American as Adam, posits "an individual emancipated from history, happily bereft of ancestry, untouched and undefiled by the usual inheritances of family and race; an individual standing alone, self-reliant and self-propelling, ready to confront whatever awaited him with the aid of his own unique and inherent resources". Lewis examines several incarnations of this Adamic figure and addresses the philosophical, theological, and cultural implications of the nascent American mythology. In doing so he combines an analysis of historical trends with the close reading of various representative literary texts, nearly all of which treat the theme of American individualism or question the principles behind it.

Of course, there are multiple ideologies to consider as this picture unfolds. Lewis adopts Ralph Waldo Emerson's terminology for the two opposing groups—the party of Hope and the party of Memory—and introduces his own, that of Irony, to include those individuals who situated themselves between the two extremes. The debate between these three camps would refine and polish the Adamic ideal, transforming it from an adolescent fantasy into a full-fledged American myth, thus discovering its redemptive power and creating some of the finest American literature to date. ~

~ Intellectual history is viewed in this book as a series of "great conversations"—dramatic dialogues in which a culture's spokesmen wrestle with the leading questions of their times. In nineteenth-century America the great argument centered about De Crèvecoeur's "new man," the American, an innocent Adam in a bright new world dissociating himself from the historic past.

Mr. Lewis reveals this vital preoccupation as a pervasive, transforming ingredient of the American mind, illuminating history and theology as well as art, shaping the consciousness of lesser thinkers as fully as it shaped the giants of the age. He traces the Adamic theme in the writings of Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, Henry James, and others, and in an Epilogue he exposes their continuing spirit in the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, J. D. Salinger, and Saul Bellow. ~

~ Lewis' contention asserts that early American literature (from Crevecoeur's "Letters from an American Farmer" to Melville's "Moby-Dick") plays on the symbol of the American Man as the "New Adam." The New Adam, in essence, was what Crevecoeur described as the man liberated from past, heritage, history — the "old world" or "sin" (so to speak) — to make himself innocent, independent, and adventurous. The world was his for the taking.

Lewis, however, also shows how this archetype of the New Adam was wrestled with by various authors. Some enthusiastically endorsed the "myth" of the New Adam as a hero not bound by the burdens of the past or sin or whatever other concept you wish to insert as bearing down on an individual. Others critiqued the Myth of the American Adam and showed the idea to be tragic and fantastical (like Hawthorne). Others yet blend the innocent and heroic Adam with the tragic wherein the innocent Adam character becomes a sage of wisdom over the complexities of life (as with Melville).

Lewis' work is a great introductory summary and analysis of the classics of American Literature that preserve the awe and wonder we should have toward our literary patrimony. Unlike modern day criticism which is poisoned by the usual suspects of political correct yelling run amok, Lewis' book returns us to the fundamental themes and messages that abounded in early American consciousness and found itself into literature.

In many ways, we are still haunted by the prospect of the American Adam, which is somewhat ironic given the American Adam was supposed to be free of burdens. Many, I think, can look at the American Adam with ironic enchantment. In trying to create the "new Adam" (the "new man") with boundless opportunities in the New World, we are still burdened by that perpetual myth which we now call "the American Dream." There is a direct line, in my opinion, from the "American Adam" to the "American Dream."

In sum, the American Adam's Myth and Symbol critique is this: America is the "land of opportunity" where an individual can free themselves from the burdens of the past and be whatever he wants to be. This constitutes the "Myth" (the Story) that we're familiar with. The Symbol of this story is the New Man ("The American Adam") who is a farmer, a soldier, a sailor, a preacher, whoever and whatever. Lewis then proceeds to show in an overview of select early nineteenth century writers how this Myth and Symbol is pervasive but in different contexts that the writer chose.

Thus we have the Innocent Adam. We also the Tragic Adam. We also have the Heroic Adam. But, ironically, according to Lewis -- whether celebratory or critical of this "American Adam" archetype and myth of boundless exceptionalism, they all follow the "tradition" of the American Adam Myth and Symbol. ~ (from Amazon reviews)

Oriana:

Funny how it all bears resembles to the New Soviet Man, the bearer of all virtues including patriotism.

The Party of Memory vs the Party of Hope sounds quite fitting for our times, as long as we remember that memory is mostly False Memory.

Mary:

Sounds romantic and mistaken…a mythology that denies history makes a fatal mistake. Sounds like Rousseau.

*

AND WHAT HAS BECOME OF THE INNOCENT AMERICAN ADAM

~ Kerry Shawn Keys has shared some disquieting thoughts about what the recent insurrection forebodes for the future: “I don't think it is just the safety of this inauguration we need to worry about — it will be about all public appearances to come, and the beginning of closed-in presentations. There are a lot of grassy knolls out there. There are thousands of folks trained to kill in An Evil Empire's brutal wars that have been "manifesting" for 300 years, and an unchecked NRA, and so on. Hyenas come home to brood and/or breed. The chicken/roost saw. How to lock up 10 percent of the country with another 30 percent silently backing them —my statistics of the moment. The continuous wars, many for oil and greed, have entitled most of us to a modicum of prosperity and others to the trash bins of their country.... Pandora's Box is open.”

~ The lid of Pandora's box has been slowly lifting for the last two decades, with school shootings and massacres all over the place. So the D.C. riot only marks the country's movement to another level of decadence, accompanied by larger and more numerous outbreaks of mayhem and madness. ~ Mel Kenne

*

THE BIG LIE, PART 2

~ Among the thousands of falsehoods Trump has uttered during his presidency, this one in particular [that Trump won the 2020 election] has earned the distinction of being called the "big lie." It's a charged term, with connotations that trace back to its roots in Nazi Germany.

Hitler used the phrase "big lie" against Jews in his manifesto Mein Kampf. Later, the Nazis' big lie — claiming that Jews led a global conspiracy and were responsible for Germany's and the world's woes — fueled anti-Semitism and the Holocaust.

Given that history, it was striking that President-elect Joe Biden chose the term when he slammed two Republican senators — Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley — who have amplified Trump's falsehood.

"I think the American public has a real good, clear look at who they are," Biden told reporters two days after the Capitol was attacked. "They're part of the big lie, the big lie."

Biden nodded to the term's origin in Nazi Germany, as embodied in Hitler's propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

"We're told that, you know, Goebbels and the great lie. You keep repeating the lie, repeating the lie," Biden said. "The degree to which it becomes corrosive is in direct proportion to the number of people who say it."

A BIG LIE TEARS THE FABRIC OF REALITY

A big lie has singular potency, says Timothy Snyder, the Levin Professor of History at Yale University, whose books include studies of Hitler, Joseph Stalin, the Holocaust and tyranny.

"There are lies that, if you believe in them, rearrange everything," he says.

"Hannah Arendt, the political thinker, talked about the fabric of reality," Snyder says. "And a big lie is a lie which is big enough that it tears the fabric of reality."

In his cover story for The New York Times Magazine this week, Snyder calls Trump "the high priest of the big lie."

As for where big lies lead, Snyder writes: "Post-truth is pre-fascism, and Trump has been our post-truth president."

"When I say pre-fascism, I mean when you take away facts, you're opening the way for something else," Snyder tells NPR. "You're opening the way for someone who says 'I am the truth. I am your voice,' to quote Mr. Trump — which is something that fascists said, as a matter of fact. The three-word chants, the idea that the press are the enemy of the people: These are all fascist concepts."

"It doesn't mean that Trump is quite a fascist himself," Snyder adds. "Imagine what comes after that, right? Imagine if the big lie continues. Imagine if there's someone who's more skillful in using it than he is. Then we're starting to move into clearly fascist territory."

As for ways to undo the destruction of a big lie, Snyder suggests one remedy would be a reinvigorated media ecosystem, with a robust force of local reporting.

"The big lie fills in this space which used to be taken up by a lot of little truths, by hundreds and thousands and millions of little truths," Snyder says. "We've let that slip away. And then the big lie comes in and fills in the gap."

"It could happen here"

Historian Fiona Hill has spent decades studying Russia and the former Soviet Union, looking at how disinformation and lies are woven into authoritarian regimes. The patterns in such states are clear, Hill says: purging staff seen as disloyal, demonizing the checks and balances of civil society, attacking the media.

"At every turn in other countries where I've seen this happen, we're starting to see the same signs here in the United States," Hill says. "So we're suddenly in the company of many others. I think the main thing is that we've had a really hard time realizing that it could happen here."

Hill brings the perspective of having served on the National Security Council under President Trump. In the 2019 impeachment hearing, she memorably swatted down what she called the "fictional narrative" embraced by Trump and Congressional Republicans that Ukraine, not Russia, interfered in the 2016 election.

Given the big lie's roots in Nazi Germany, is it a stretch, a poor analogy, to call Trump's claim that he won the 2020 election a big lie? No, says Hill: "It's not a stretch when it's intended to subvert the democratic order or it's intended to pit one group against another, which is what exactly happened in this setting."

Don't get bogged down in the terminology, Hill advises. "I don't actually think that we should get caught up in the origins of where this term — the big lie — comes from," she says, "because this is clearly a lie on a large scale that was meant to have political consequences, and was also intended to pit one group of people within society against another."

Trump has told so many falsehoods that he's effectively normalized lying, Hill says, and he's taken his cues from the autocrats he publicly admires.

She recalls: "President Trump was also talking openly about removing term limits. 'Wouldn't that be great?' And the thing is, everyone thought he was joking. But as I learned from observing him, he says things in these throwaway manners, but he's deadly serious. He's not joking at all."

Neutralizing the big lie won't be easy, Hill says. "Some people will always believe it. That is also an element of the big lie. It takes root. And no matter what you do, it becomes extraordinarily hard to refute it for some people.

Trump's use of the big lie comes from an age-old authoritarian playbook, says Ruth Ben-Ghiat, history professor at NYU and author of the book "Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present."

"It's part of a much larger discourse of throwing any mechanism of democracy, any democratic institution into doubt," she says.

Ben-Ghiat says while Trump will soon be gone from the White House, "he's also going to carry his victimhood cult with him, which will be stronger than ever. So we haven't seen the last of those lies and the pernicious effects they're going to have on our democracy."

Put another way, as historian Timothy Snyder writes, "the lie outlasts the liar.” ~

https://www.npr.org/2021/01/16/957291939/can-the-forces-unleashed-by-trumps-big-election-lie-be-undone

*

IT COULD HAVE BEEN MUCH WORSE

~ As shocking as last week’s pro-Trump storming of the Capitol was, it’s becoming clearer by the day how much worse it could have been. For the first time, federal prosecutors have stated their view that the Trumpist mob broke into Capitol with the intention of capturing and assassinating government officials. In a filing asking a judge to detain Jacob Chansley—the Arizona man whose horned outfit led him to be dubbed the “QAnon Shaman”—prosecutors wrote: “Strong evidence, including Chansley’s own words and actions at the Capitol, supports that the intent of the Capitol rioters was to capture and assassinate elected officials in the United States government.” The lawyers pointed to a note that Chansley left on Mike Pence’s desk warning the veep: “It’s only a matter of time, justice is coming.” Chansley has not responded to the latest allegations. ~ (the Daily Beast)

(cont. at Reuters): “Strong evidence, including Chansley’s own words and actions at the Capitol, supports that the intent of the Capitol rioters was to capture and assassinate elected officials in the United States government,” prosecutors wrote.

The prosecutors’ assessment comes as prosecutors and federal agents have begun bringing more serious charges tied to violence at the Capitol, including revealing cases Thursday against one man, retired firefighter Robert Sanford, on charges that he hurled a fire extinguisher at the head of one police officer and another, Peter Stager, of beating a different officer with a pole bearing an American flag.

In Chansley’s case, prosecutors said the charges “involve active participation in an insurrection attempting to violently overthrow the United States government,” and warned that “the insurrection is still in progress” as law enforcement prepares for more demonstrations in Washington and state capitals.

They also suggested he suffers from drug abuse and mental illness, and told the judge he poses a serious flight risk.

“Chansley has spoken openly about his belief that he is an alien, a higher being, and he is here on Earth to ascend to another reality,” they wrote.

The Justice Department has brought more than 80 criminal cases in connection with the violent riots at the U.S. Capitol last week, in which Trump’s supporters stormed the building, ransacked offices and in some cases, attacked police.

Many of the people charged so far were easily tracked down by the FBI, which has more than 200 suspects, thanks in large part to videos and photos posted on social media.

Michael Sherwin, the Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, has said that while many of the initial charges may seem minor, he expects much more serious charges to be filed as the Justice Department continues its investigation. ~

*

WHAT KIND OF PERSON BELIEVES IN QANON?

~ Here's an interview I conducted for Julia Sachs's article about QAnon for GritDaily:

Have you noticed specific traits in people that become QAnon believers?

First of all, about half the population believes in at least one conspiracy theory, so conspiracy theory beliefs are "normal." That said, psychology research has shown greater degrees of certain cognitive quirks among those who believe in conspiracy theories—like need for uniqueness; needs for certainty, closure, and control; and lack of analytical thinking. But the best predictor of conspiracy theory belief may be mistrust, and more specifically, mistrust of authoritative sources of information. Which means that those most likely to become QAnon believers mistrust mainstream sources of information, spend a lot of time on the internet and social media looking for alternative answers, and are devotees of President Trump.

QAnon also includes other facets that are appealing to some that can serve as "hooks" that lure people into the world of QAnon. There's obviously a central pro-Trump/anti-liberal component, but there's also considerable overlap with evangelical Christianity and its looming apocalyptic battle between good and evil. And now there's overlap with people who are concerned about child sex trafficking, with QAnon highjacking #SaveTheChildren. Curiously, however, those who are "hooked" from this angle are able to turn a blind eye to President Trump's own friendship with Jeffrey Epstein or the several charges made against him about sexual assault of minors, which amounts to a classic case of cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias.

In what ways does this conspiracy theory impact relationships?

In order to maintain fringe beliefs, it's often necessary to turn away from the mainstream, including any family and friends who disagree with you. In "falling down the rabbit hole," QAnon followers have often found a new world, and to some extent a new "family" of like-minded believers that make previous relationships less rewarding and more fraught. Similar to differences in political beliefs, arguments about QAnon can definitely break up marriages or cause significant strain on other relationships.

Immersing oneself in the internet world of QAnon can also resemble a behavioral addiction to pursuits like video games or gambling. QAnon is a complex world of interrelated conspiracy theories; it takes significant effort to follow. And so, devotees often end up spending more and more time on it, at the expense of in-person relationships, work, or more traditional recreational activities.

How should someone approach speaking to a loved one about their belief of QAnon?

Is that different from clashing political or religious beliefs? How scared should someone be of an aunt who believes in QAnon come Thanksgiving?

I wouldn't use the word "scared." If you're not looking for a fight, don't argue and don't engage. If they bring it up, try saying something like, "I know this is really important to you, but I'd prefer to not talk about this... can we talk about something else tonight?” ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psych-unseen/202009/what-kind-person-believes-in-qanon

“The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down a very deep well… Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do…” ~ Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL NEEDS THAT QANON FEEDS

Where we go one, we go all. —QAnon mantra

Ever since I started writing about conspiracy theories, readers have occasionally written in to ask for advice about a family member who has fallen down the rabbit hole of belief. To be honest, beyond expressions of sympathy and referring them back to my posts about why people are attracted to conspiracy theories in the first place, I often feel at a loss to offer anything helpful. The stark reality is that becoming obsessed with conspiracy theory beliefs has significant potential to drive a wedge between loved ones that can irreparably damage relationships.

Understanding the Psychological Needs That QAnon Feeds

QAnon is a curious modern phenomenon that’s part conspiracy theory, part religious cult, and part role-playing game.

Some of the psychological quirks that are thought to drive belief in conspiracy theories include need for uniqueness and needs for certainty, closure, and control that are especially salient during times of crisis. Conspiracy theories offer answers to questions about events when explanations are lacking. While those answers consist of dark narratives involving bad actors and secret plots, conspiracy theories capture our attention, offer a kind of reassurance that things happen for a reason, and can make believers feel special that they’re privy to secrets to which the rest of us “sheeple” are blind.

With an invisible leader (it’s not even clear if “Q” is a single individual or several), no organizational structure, and no coercive element for membership (people are free to “come and go” as they please), it would be a stretch to call QAnon a religious cult. But it has been increasingly modeled as something of a new religious movement, especially inasmuch as it’s often intertwined with an apocalyptic version of Christianity.

Previous research on cults has revealed that people who join them are more likely to have symptoms of anxiety and depression and are often lonely people looking for emotional and group affiliation. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a similar psychological profile may also account for why some might find QAnon appealing.

Beyond conspiracy theory and online cult, QAnon has also been described as “an unusually absorbing alternate-reality game” where online players who refer to themselves as “bakers” eagerly await the chance to decipher cryptic clues in the form of “bread crumbs” or “Q-drops.” These rewards are dispensed within an irregular "variable ratio reinforcement schedule" that highlights how QAnon represents an immersive form of entertainment that, like online gaming or gambling, provides an ideal set-up for a kind of compulsive behavior that resembles addiction.

The puzzle-solving, role-playing dimension of QAnon acts as another reinforcing intoxicant of sorts, providing believers with an exciting new identity as a "Q Patriot." Back in the 1980s, parents worried that kids playing Dungeons and Dragons would get so invested in their magical role-playing characters that they might lose touch with the real world. Today, QAnon is a kind of live-action role-playing game in which the conflation of fantasy and reality isn’t so much a risk as a built-in feature.

Understanding the multifaceted aspects of QAnon in this way helps to understand its appeal as well as why believers might be unwilling to unplug and walk away. For those immersed in the world of QAnon, climbing out of the rabbit hole could represent a significant loss—of something to occupy one’s time, of feeling connected to something important, of finally feeling a sense of self-worth and control during uncertain times.

Without replacing QAnon with something else that satisfies one's psychological needs in a similar way, escape may be unlikely. Of course, leaving QAnon would allow believers to reclaim significant time and energy that might be better channeled into healthier real-life relationships, work, and recreational pastimes. But for many, the very lack of such sources of meaning might have led them to seek out QAnon in the first place, such that there would be little guarantee of finding them anew.

From that perspective, life down in the rabbit hole might look pretty good. As one QAnon believer put it, “Q is the best thing that ever happened to me.”

How can we convince our loved ones to walk away from that?

*

People who believe in conspiracy theories, however “crazy” they might sound, are no more delusional than those who believe in literal interpretations of religious texts like the Bible or the Quran. And so QAnon—the increasingly popular “right-wing” belief about the secret nefarious machinations of the Satan-worshipping, child-trafficking “Deep State” and President Trump’s destiny to thwart them—is a classic conspiracy theory, not a delusion. Now, if someone were to believe not only in QAnon dogma, but also in the false and unshared belief that they are Q, that would suggest a delusion. Note that it’s possible to believe in both conspiracy theories and delusions at the same time, with some overlap.

Moving along a continuum of conspiracy theory belief, dimensions like conviction, preoccupation, extension, and distress would be expected to increase across it, along with mistrust in authoritative and mainstream sources of information. As believers go deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole, more and more time is spent “researching” conspiracy theories and immersing oneself in online discussions with other conspiracy theory believers, with less and less time spent on work, relationships, or other recreational pursuits. As this happens, believers increasingly turn their back on previous friends and family who don’t agree with their beliefs and don’t “inhabit” their new world.

Similar to how physicists understand light as both “particle” and “wave,” it can also be helpful to conceptualize belief intensity as discrete points along a continuum, like colors in the visible light “spectrum.” Conspiracy theory researcher Dr. Bradley Franks and his colleagues have proposed just such a spectrum model, with 5 “types” or stages of conspiracy theory belief. Their model goes something like this (with additional comments added by me):

Type/stage 1: People feel like “something isn’t right,” but keep an open mind as they seek answers to questions.

Type/stage 2: People feel as if “there’s more to reality than meets the eye,” are skeptical about official explanations, and start to seek out alternative sources of information.

Type/stage 3: Mistrust of authoritative sources of information increases to the point of definitive belief that some official narratives are untrue. As a result, people continue to seek information and engage with like-minded people from whom they gain a sense of belonging and group membership. They’re also more likely to get involved in “political action.”

Type/stage 4: At this point, nearly all official and mainstream accounts are rejected so that people turn away from the mainstream in favor of affiliation with an “enlightened” community of conspiracy theory believers. Non-believers are dismissed as “sheep” who are “asleep.”

Type/stage 5: In the final stage, authoritative and mainstream accounts are rejected to such an extent as to embrace belief in not only improbable, but frankly supernatural explanations for events (e.g. aliens, lizard people, etc.). At this stage, conspiracy theories and delusions may begin to overlap with self-referential aspects.

Dr. Franks’ proposed spectrum of conspiracy theory believers is a novel framework to help understand just how far down the rabbit hole conspiracy theory believers have gone. But for the purpose of deciding how to intervene within that continuum, it may be more useful to more simply divide conspiracy theory believers into two stages: “fence-sitters” and “true believers.”

Fence-Sitters and True Believers

The mentally healthy way to hold most of our beliefs is with “cognitive flexibility,” acknowledging that we might be wrong and remaining open to other people’s perspectives. It’s likewise a good idea to maintain a healthy level of skepticism about new information that we encounter lest we succumb to our cognitive biases and merely reinforce preexisting beliefs.

This is especially true when we’re talking about theories where supporting evidence is modest or preliminary, and in the case of religious or political beliefs, where a lack of objective evidence often leads to many equivocal perspectives, such that faith becomes necessary to sustain belief.

In the early stages of conspiracy theory belief, people are “fence-sitters” who are looking for answers and haven’t yet made up their minds. Cognitive flexibility and open-mindedness may be intact, but skepticism is already closely linked with mistrust of authoritative sources of information. At this stage, conspiracy theories are appealing as expressions of, or even metaphors for, that mistrust—for the idea that both information and informants are unreliable—without necessarily having a significant degree of belief conviction. This preliminary stage explains why some people might endorse Flat Earth conspiracy theories without actually believing the Earth is flat.

Farther down the rabbit hole, conspiracy theories are embraced with greater belief conviction and become entwined with a new group affiliation and personal identity (e.g. within QAnon, adherents identify as “anons,” “bakers,” and “Q-patriots”) that makes it increasingly difficult to maintain previously established social ties. As such “true believers” move away from the mainstream and in turn are estranged because of their fringe beliefs, they often feel increasingly marginalized and under threat.

In order to protect themselves and resolve cognitive dissonance, they often “double down,” ramping up belief conviction further and diving even farther into a new ideological world. Many will increasingly feel the need to take action, whether spending more time posting on social media in order to “spread the word” or at the extreme, through more drastic and potentially dangerous measures like arming themselves in order to “self-investigate” a child pornography ring at a pizza parlor.

When people’s beliefs become so enmeshed with their identities, giving them up can be viewed as an existential threat akin to death. Needless to say, that's a bad prognostic sign.

1. Understand That "QAnons" Don’t Want to Be Saved

The greatest hurdle in trying to help a loved one who’s fallen down the conspiracy theory rabbit hole is that they probably don’t want to climb out. Extending a hand isn’t likely to help if a loved one doesn’t reach out and grab it or meet you halfway.

A similar perspective comes from an old psychiatry joke:

“How many psychiatrists does it take to change a lightbulb? ~ “Only one, but the lightbulb has to really want to change.”

QAnon is part conspiracy theory, part religious cult, and part alternate reality role-playing game. Thinking about QAnon based on these different facets helps to understand why followers don’t want to escape—doing so might mean giving up a form of recreation, a sense of belonging, or even a new identity and mission in life. But these facets also suggest possible interventions.

For example, modeling QAnon as a kind of role-playing game that has the potential to become a behavioral addiction like video gaming or gambling suggests that some principles of addiction therapy could be applied to help those obsessed with QAnon. In addiction therapy, quantifying motivation for behavioral change is a core concept, with specific interventions matched to each stage of motivation. When that motivation is lacking in the so-called “precontemplation” stage, often the best intervention is to simply maintain contact, express concern, and let people know you’re there for them if they need you. That’s a great strategy for the friends and family of QAnon conspiracy theory believers who aren’t looking for help.

In a type of psychotherapy called “motivational interviewing” (MI), therapists are taught to be on the lookout for any statements that might suggest that a compulsive behavior is causing problems in someone’s life and to use that to encourage change without arguing about it. So, if someone were to say, “I’m getting in trouble at work for spending so much time online, but no one understands that QAnon is more important than anything else,” an MI therapist might reply with a reflective comment like, “other people don’t appreciate how important QAnon is to you and that’s starting to negatively affect your life.” This is a non-confrontational way of echoing distress caused by QAnon that can hopefully nudge someone closer to the “contemplation” stage of thinking about whether it might be worth trying to “unplug.”

Since QAnon is largely an online phenomenon, “unplugging” is a key step in walking away, but is best done willingly. Modeling QAnon as a cult suggests that “deprogramming” techniques—a kind of "unbrainwashing"—could be helpful, but when deprogramming was used in its 1970s heyday, it usually began with families forcibly removing their loved ones from the physical confines of a cult. It’s nearly impossible to prevent access to the internet these days, aside from taking internet privileges away from a child or refusing to pay someone’s internet bill. Social media companies like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter are slowing coming around to doing their parts by unplugging QAnon groups from their platforms, but such measures may have limited efficacy.

2. Be a “North Star”

More than anything, what a QAnon-obsessed loved one probably needs is support and to stay connected to something tangible and meaningful in the real world. Depending on circumstances, that might be possible without having to talk about QAnon. Focus on other common bonds instead—and if the conversation comes around to QAnon, try saying something like, "I know this is really important to you, but I'd prefer to not get into politics... can we talk about something else?" Of course, that kind of boundary-setting is less possible when people who are living together or in a romantic relationship are in daily contact.

The common tactic of ridiculing conspiracy theory beliefs is usually counterproductive but may depend on how far down the rabbit hole your loved one has gone. Research has shown that ridicule and rational arguments can be effective under some circumstances, especially for “fence-sitters” who have not yet decided exactly what to believe.

But for “true believers” whose identity has become wrapped up in QAnon, ridicule and argument will usually just make them dig their heels in deeper. For “true believers” then, it’s best to avoid those easy traps—they’re much more likely to end in impasse than any progress modifying beliefs.

3. Refer to Debunking Experts

Another form of psychotherapy that could be applied to conspiracy theory beliefs is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is designed to challenge “cognitive distortions” and false beliefs by looking at evidence to disconfirm them. However, success in CBT requires not only that the “lightbulb wants to change,” but also that the therapist is adequately equipped to objectively analyze the evidence. That means that in order to engage in “reality testing” about QAnon, you'll have to venture down the conspiracy theory rabbit hole yourself.

But the QAnon rabbit hole is so deep and tangled that it’s not particularly realistic—or healthy—for family and friends to jump in with their loved ones. In the 1998 movie What Dreams May Come, the late Robin Williams plays a man who, in order to rescue his wife from hell, has to go there himself to pull her out. In the end, her salvation requires that he give up on rescue in favor of committing to staying in hell forever and losing his mind.

With conspiracy theory believers, that’s often exactly what’s wanted from their loved ones based on the belief that they’ll see the light and want to stay there together. But while “joining them to save them” might make for a great Hollywood ending, it isn’t particularly likely to work in the real world.

I would never recommend that someone try to rescue a loved one from drug addiction by becoming a drug addict themselves nor would I recommend that they try to “wing it” as a psychotherapist to treat a loved one’s psychiatric disorder. Just so, I don’t recommend that friends and family jump down the rabbit hole to debate the legitimacy of QAnon, especially if their loved ones are “true believers” who are deep in the hole. What I do recommend is referring their loved ones to accounts of those who have left the conspiracy theory world or to experts who know about QAnon and have experience and success with debunking.

One “referral” option is to point QAnon believers to the Reddit subforum r/QAnonCasualties where they can read other accounts of just how much havoc QAnon has wreaked on other people’s lives and relationships so that they can better understand why you’re concerned.

Encourage your loved one to check out the discussion forums of conspiracy theory debunker Mick West’s website Metabunk.org. West has detailed knowledge of conspiracy theories and has debunked several QAnon claims, but also likes to point out real-life conspiracies worthy of our attention. He has a kind of infectious enthusiasm for debunking that he believes could satisfy some of the needs that conspiracy theories fulfill for believers.

In that vein, you might suggest that your loved one “do their own research” and spend more time investigating the identity of “Q” rather than accepting what “he” says at face value. In fact, there’s more evidence that QAnon has been perpetuated as a kind of hoax for financial gain (e.g. Google “Jim Watkins”) than there is to support that Q is a reliable source of information. All too often a simple, real-life conspiracy theory lurks behind the more outlandish ones.

4. Get Help for Yourself

If your loved one has fallen down the QAnon rabbit hole, help them by helping yourself. Visit r/QAnonCasualties for support and share your story there.

Arm yourself with knowledge. Here’s a recommended reading list:

“How to talk to conspiracy theorists—and still be kind” by the moderators of the Reddit r/ChangeMyView subforum.

"My father, the QAnon conspiracy theorist" by Reed Ryley Grable.

Escaping the Rabbit Hole: How to Debunk Conspiracy Theories Using Facts, Logic, and Respect by Mick West.

Freedom of Mind: Helping Loved Ones Leave Controlling People, Cults and Beliefs and The Cult of Trump by ex-cult member turned cult expert and counselor Steven Hassan.

David Neiwert’s forthcoming book Red Pill, Blue Pill: How to Counteract the Conspiracy Theories That Are Killing Us also looks to be a worthwhile read. ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/psych-unseen/202009/4-keys-help-someone-climb-out-the-qanon-rabbit-hole

*

THE THWARTED CAPITOL RIOT OF 1861

~ 13 February 1861 a mob-like "militia" gathered outside the Capitol determined to prevent the Electoral College certification of Abraham Lincoln. Winfield Scott, a Virginia gentleman and head of the army, foresaw militia action. He was ready. His soldiers drove the militia back. The Southerners shouted invective at Scott calling him, among other things, a "Free State Pimp!"

Inside the Capitol another Southerner also helped save the Republic. John C. Breckenridge, the defeated presidential candidate, happened to be Vice President. He was supposed to deliver the certificates and preside over his own defeat. Like Mike Pence he did his duty. A week from Wednesday Trump will be out of office. It can't come soon enough. ~ Michael Andre

~ Lincoln rode with Buchanan to the inaugural. This in spite of all Buchanan's treachery. Buchanan told Lincoln that he hoped, he, Lincoln, was as happy to gain the White House as he, Buchanan, was to be leaving it. ~ James M. Cory

on a lighter note: ~ On January 15, 2019, the White House hosted the Clemson football team, who trounced Alabama 44 to 16 on their way to a National Championship.

For their victory, the Clemson Tigers were offered an extravagant meal of assorted selections from various fast food restaurants, including McDonald's, Wendy's, and Burger King.

President Trump told gathered media, "I think that would be their favorite food, so we'll see what happens. We have some very large people that like eating. So I think we're going to have a little fun.”

. Oriana: while Lincoln in the portrait looks on

https://www.radio.com/alt1037dfw/blogs/luckey/president-trump-treats-college-football-champs-gourmet-feast-fast-food

*

Oriana:

This made me think of the sculptures of Greek gods, some missing arms etc. -- except those would show the god in the nude, an idealized male body.

The photo comes from the abandoned theme park, Holy Land USA, in Waterbury, Connecticut.

Considering the rapid decline in religiosity, maybe the gap between the modern world and the the story about an invisible man in the sky has finally grown too wide. Popular culture is the #1 shaper of values and beliefs. There will always be the destitute and the desperate for whom religion is important, but that's not an argument for the validity of any mythology.

I mean "validity" in the sense of literal, historical truth, not in the metaphoric sense of whatever wisdom we can distill from the stories, and as part of cultural heritage.

*

SPIDERS CAN “BALLOON” HUNDREDS OF MILES USING THE EARTH’S ELECTRIC FIELD

~ On October 31, 1832, a young naturalist named Charles Darwin walked onto the deck of the HMS Beagle and realized that the ship had been boarded by thousands of intruders. Tiny red spiders, each a millimeter wide, were everywhere. The ship was 60 miles offshore, so the creatures must have floated over from the Argentinian mainland. “All the ropes were coated and fringed with gossamer web,” Darwin wrote.

Spiders have no wings, but they can take to the air nonetheless. They’ll climb to an exposed point, raise their abdomens to the sky, extrude strands of silk, and float away. This behavior is called ballooning. It might carry spiders away from predators and competitors, or toward new lands with abundant resources. But whatever the reason for it, it’s clearly an effective means of travel. Spiders have been found two-and-a-half miles up in the air, and 1,000 miles out to sea.

It is commonly believed that ballooning works because the silk catches on the wind, dragging the spider with it. But that doesn’t entirely make sense, especially since spiders only balloon during light winds. Spiders don’t shoot silk from their abdomens, and it seems unlikely that such gentle breezes could be strong enough to yank the threads out—let alone to carry the largest species aloft, or to generate the high accelerations of arachnid takeoff. Darwin himself found the rapidity of the spiders’ flight to be “quite unaccountable” and its cause to be “inexplicable.”

But Erica Morley and Daniel Robert have an explanation. The duo, who work at the University of Bristol, has shown that spiders can sense the Earth’s electric field, and use it to launch themselves into the air.

Every day, around 40,000 thunderstorms crackle around the world, collectively turning Earth’s atmosphere into a giant electrical circuit. The upper reaches of the atmosphere have a positive charge, and the planet’s surface has a negative one. Even on sunny days with cloudless skies, the air carries a voltage of around 100 volts for every meter above the ground. In foggy or stormy conditions, that gradient might increase to tens of thousands of volts per meter.

Ballooning spiders operate within this planetary electric field. When their silk leaves their bodies, it typically picks up a negative charge. This repels the similar negative charges on the surfaces on which the spiders sit, creating enough force to lift them into the air. And spiders can increase those forces by climbing onto twigs, leaves, or blades of grass. Plants, being earthed, have the same negative charge as the ground that they grow upon, but they protrude into the positively charged air. This creates substantial electric fields between the air around them and the tips of their leaves and branches—and the spiders ballooning from those tips.

This idea—flight by electrostatic repulsion—was first proposed in the early 1800s, around the time of Darwin’s voyage. Peter Gorham, a physicist, resurrected the idea in 2013, and showed that it was mathematically plausible. And now, Morley and Robert have tested it with actual spiders.

First, they showed that spiders can detect electric fields. They put the arachnids on vertical strips of cardboard in the center of a plastic box, and then generated electric fields between the floor and ceiling of similar strengths to what the spiders would experience outdoors. These fields ruffled tiny sensory hairs on the spiders’ feet, known as trichobothria. “It’s like when you rub a balloon and hold it up to your hairs,” Morley says.

In response, the spiders performed a set of movements called tiptoeing—they stood on the ends of their legs and stuck their abdomens in the air. “That behavior is only ever seen before ballooning,” says Morley. Many of the spiders actually managed to take off, despite being in closed boxes with no airflow within them. And when Morley turned off the electric fields inside the boxes, the ballooning spiders dropped.

It’s especially important, says Angela Chuang, from the University of Tennessee, to know that spiders can physically detect electrostatic changes in their surroundings. “[That’s] the foundation for lots of interesting research questions,” she says. “How do various electric-field strengths affect the physics of takeoff, flight, and landing? Do spiders use information on atmospheric conditions to make decisions about when to break down their webs, or create new ones?”

Air currents might still play some role in ballooning. After all, the same hairs that allow spiders to sense electric fields can also help them to gauge wind speed or direction. And Moonsung Cho from the Technical University of Berlin recently showed that spiders prepare for flight by raising their front legs into the wind, presumably to test how strong it is.

Still, Morley and Robert’s study shows that electrostatic forces are, on their own, enough to propel spiders into the air. “This is really top-notch science,” says Gorham. “As a physicist, it seemed very clear to me that electric fields played a central role, but I could only speculate on how the biology might support this. Morley and Robert have taken this to a level of certainty that far exceeds any expectations I had.”

“I think Charles Darwin would be as thrilled to read it as I was,” he adds. ~

*KNOWLEDGE VERSUS FAITH

After my first religion lessons, I was filled with the question, If god exists, why doesn't he just show himself? Maybe he could open a window in the sky and show his face? Or at least say something? He did talk to Adam and Eve, and later to Moses . . . Why not to us, now?

I wasn’t the only one. Other children were apparently also confused by the invisibility of “Mr. God,” as we politely called him in Polish. Why was Mr. God hiding? One little boy was actually brave enough to ask the nun just that: why did god speak to Adam and Eve, to Noah and Abraham and other people in the stories, but never to us?

(Perhaps god didn't speak Polish, was one of possible reasons that occurred to me; that would also explain why our prayers were not answered.)

The nun smiled in a sad way. Nuns didn't normally smile, so that smile, even if sad, was striking. "The times were different then," she said.

Yes, those were the eras filled with supernaturalism. People believed in gods and demons as the main cause of events. Those who heard voices were often called prophets rather than being seen as mentally ill.

**

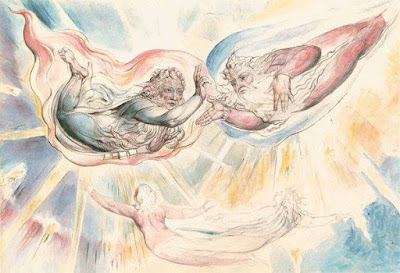

Flying figures with long flowing beards are hard to resist. Since I already had the image, I checked on the part of Dante’s Paradiso in which St. Peter and St. James appear, wondering if I’d find some beautiful lines to quote for the Poetry Salon. Alas, I found those cantos dreadfully boring, the language flat and didactic rather than subtle and imagistic.

(The canto that follows is more interesting: the original Adam appears and supplies information on the age of the earth -- not much over 6,000 years -- and on the language that he spoke -- no, not Hebrew, as Dante earlier claimed, but a language that became extinct even before the building of the Tower of Babel.)

St. Peter examines Dante’s faith, asking about evidence. Dante gives the official scholastic proofs: first cause, the unmoved mover, etc. — and miracles. The scholastic arguments have all been invalidated. As for miracles, I’ve never read or heard of any that could be categorically ruled out as coincidence or natural healing. In fact Dostoyevski’s Grand Inquisitor condemns Christ for not having established undeniable miracle as the basis of religion, having instead condemned humanity to believe or not believe in the absence of convincing evidence for the supernatural.

Actually I never understood why it would be so bad if god, assuming such an all-powerful and all-good being exists somewhere in the cosmos and cares about human beings, gave us some clear proof of his (or “its’) own existence (many would settle for even a weak proof, just as long as there IS a proof). The usual answer seems to be: then we would not need faith because we’d have knowledge, and god prefers us to believe without proof rather than to have knowledge. If he provided evidence of his existence, then faith would not have the great merit that it has. As soon as compelling evidence is produced, faith ceases to be faith and becomes knowledge. Faith is faith only because it’s not knowledge.

Thus knowledge as opposed to faith is even seen as a bad thing, depriving faith of merit. But wouldn’t religious wars cease since the whole world would have the proof as to which god is the true one? Is there indeed a single bad effect that such knowledge would have?