*

ALL SOULS

Sometimes I think Warsaw fog

is the dead, coming back

to seek their old homes —

wanting to touch even the walls.

But they cannot find those walls,

so they embrace the trees instead,

lindens and enduring chestnuts;

they embrace the whole city,

lay their arms around the bridges

and the droplet-beaded street lamps;

they pray in the Square of Three Crosses,

kneel among the candles and flowers

under bronze plaques that say

On this spot, 100 people were shot —

they bow, they kiss

even the railroad tracks —

they do not complain, only hold

what they can, in unraveling white.

~ Oriana

*

Mary:

The opening poem is beautiful, and I love the idea that the dead remember the places they loved in life, that if they come back it would be to embrace those beloved places. Somehow this is even more poignant than the idea that the dead remember us, the ones they've left behind, perhaps because we know so well how places change in time, that nothing much may remain, after bombs and fire, reconstruction or simple neglect, that our homes may be gone, unreachable, but the trees may still grow there, the bridges and avenues, and those sacred places where so many were sacrificed. It's a wonderful reversal, that instead of the living visiting the graveyards, as on All Souls Day, to remember the dead, that the dead would visit their lost homes, to remember the living.

Oriana:

Warsaw is a very haunted city, with so much tragic history — of course you could say this of all of Poland. And in my memory at least, Warsaw fog seems to have been more white, more ghost-like, more wind-riven, unraveling, dividing before you as you walk . . . The poem came to me when I woke up in the middle of the night, I forget which year — one of those timeless moments. And now it’s up to the reader to imagine it again.  Warsaw, 1945

Warsaw, 1945

*

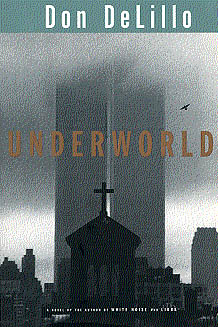

IN THE RUINS OF THE FUTURE: AN INTERVIEW WITH DON DELILLO

~ A permeating paranoia. Profound absurdity. Conspiracy and terrorism. Technological alienation. Violence bubbling, ready to boil. This has long been the stuff of Don DeLillo’s masterly fiction. It’s now the air we breathe. For nearly 50 years and across 17 novels, among them classics like “White Noise,” “Libra” and “Underworld,” DeLillo, who is 83, has summoned the darker currents of the American experience with maximum precision and uncanny imagination. His enduring sensitivity to the zeitgeist is such that words like “prophetic” and “oracular” figure frequently in discussion of his work.

They will very likely figure again in regards to his new novel, “The Silence,” in which a mysterious event on Super Bowl Sunday 2022 causes screens everywhere to go blank. “The way our culture moves along changes the way all of us think,” DeLillo said. “I don’t think it’s a question of better or worse. It’s simply inevitable.”

Let me ask about something that’s not in “The Silence,” at least not anymore. In the first galley copy I read, there’s a scene in which a character is reciting disastrous events and mentions Covid-19. Then I was told there were changes to the book and was sent a second galley. Covid-19 was gone. Why did you take it out?

I didn’t put Covid-19 in there. Somebody else had. Somebody else could have decided that it made it more contemporary. But I said, “There’s no reason for that.”

I’m shocked that an editor or whoever had the chutzpah to jam anything, let alone a Covid-19 mention, into one of your books.

It wasn’t going to stay, that’s for sure.

Still, “The Silence” feels attuned to current anxieties. What planted the seed?

What got me going was the idea of a blank screen. It led everything. Then there was the notion of the Super Bowl, which has been in the back of my mind for some years. Watching the football game joins us together in one aspect and then looking at a blank screen suddenly is a kind of cataclysmic footnote. There was also a flight I was on between Paris and New York, and for somewhat mysterious reasons, I made notes. There was a screen under the overhead bin. So I watched the screen and there was information there like outside air temperature, time in New York, arrival time, speed, etc. I wasn’t accustomed to this.

I hate when I’m on a plane and realize I’m compelled to keep staring at that screen. What intrigued you about it?

What was intriguing is that I was also compelled to look. I’d never experienced this before.

That makes me think of the characters Max and Jim in “The Silence,” who are always looking at screens as a substitute for generating their own thoughts, which a lot of us do these days. In what ways does having the constant cognitive crutch of a screen to look at affect our minds?

Technology has changed the way we think, talk. Everything was different before this somewhat abrupt technological advance. Our thinking is less meditative and somewhat more instantaneous. I don’t use a cellphone, because I want to keep thinking in a traditional manner. It helps me concentrate on words on a page. This has always been an important element in the way I work: simply the appearance of words on a page, letters in the word, words in the sentence. If I can go on for a minute, I think it started with “The Names,” which I wrote in the early 1980s: I recall clearly seeing the visual connection between letters, between letters in a word, words in a sentence. When I started working on “The Names” I decided to limit each page to a paragraph, one paragraph per page, which helped me in a visual sense to concentrate more deeply, and I’ve been doing it more or less consistently ever since.

For example, there’s a phrase I remember at the end of “Underworld”: Raw sprawl. The word “raw” is contained in the word “sprawl.” That sort of thing became more apparent to me after “The Names.” I have to add this: I still use an old Olympia typewriter. It has large type and allows me to see more clearly the letters on a page.

What you’re talking about is a sensitivity to the aesthetics of words and language. Has digital life changed things in that regard? Is it all degradation?

I don’t think of it as degradation. It’s simply what happens. It’s a form of progress. This is the path of technology. I don’t necessarily long to go back to precomputer days. I accept what we have and in many ways I’m astonished by it.

What do you find astonishing?

The enormous thrust forward, if it is forward. Whatever technology is capable of doing becomes what it must do. It’s uncontrollable.

Like, if we can surveil someone through their phone, we will surveil someone through their phone?

Absolutely. If a certain thing can be developed, it will be developed. Many things are being developed to the general advantage of people and civilization and then there are the things that individuals will do because they find a way to do it. This is what causes all sorts of disruptions in technology and people’s lives. Because an individual can find a way to do something technologically, he or she, depending on the kind of person, will do it.

You don’t use smartphones and computers, right?

Very little. I’m more comfortable with an old telephone. I’m speaking to you on an old landline, and this is what I like to do. It makes me feel normal.

Do you often feel abnormal?

[Laughs.] I don’t. Maybe subnormal.

Do you read any websites?

No, I don’t. My wife has a computer, but no, I don’t have any interest in that.

Your fiction, inasmuch as it’s about any one particular thing, is about what makes us uncomfortable. So I’m curious: What gives you comfort?

Writing gives me comfort. Trying to understand can be somewhat self-enlightening, maybe in a self-deceptive way, but that’s helpful. My personal question is, Will I keep writing fiction? The answer is that I’m just going to see what happens. It’s possible that I’ll try to think about arranging a volume of my nonfiction work. I don’t know.

Maybe this is a stupid question — and maybe the answer to it is the novels themselves — but after 50 years of thinking and writing, do you feel as if you have a firm understanding of this American society that in so many ways flummoxes the rest of us?

I think I’ve remained open to whatever happens around us and as confused as other people become by what happens around us. I don’t think that the work I’ve done gives me any great, deep perception about what’s going on. I mean, I couldn’t discuss with you on a certain level of intelligence the current presidential campaigns.

Nor presumably would you want to.

You’re right. Will I be looking at the presidential debate? I may be watching baseball.

Have you been watching the games played in empty stadiums?

I’ve watched some. The empty seats are astonishing. I much prefer the empty seats to other stadiums where they have fake faces in the stands. I think that’s a desecration of baseball. The empty seats, they’re satisfying in a curious way. The simple, traditional game of baseball is almost elevated to an element of art by the lack of people in the stands. It’s all very stylized. I notice things I haven’t usually noticed. People keep hitting foul balls. More than ever, it seems. Foul balls. Foul balls. Three-and-two count, foul ball — almost inevitably on a three-and-two count. The oddness of it all. Hitting a home run to empty stands. Yeah, it becomes a form of art in a way.

If you have written your last novel, which as you suggested remains an open question, how do you feel about what you’ve accomplished?

I never expected my first novel to be published, and it was published by the first publisher to look at it. Ever since then I’ve felt lucky.

I understand your gratitude at being able to make a living as a writer, but from a self-critical perspective have you done what you set out to do?

I could have done better perhaps in the 1970s and, to a lesser extent, since then. But at the time I thought I was doing as well as I could. In retrospect, certain novels probably could have been better. Can I possibly say that I should have resisted the urge to get going on such novels?

Which ones?

[Laughs.] Maybe I could have done better with “The Body Artist”; “Point Omega.” There are enthusiastic responses to these books, particularly “Point Omega,” but when I was working, I don’t think I totally reached the level of enthusiasm that I usually do. But I kept on going.

Is “The Silence” intended at all as a kind of career summary? I ask because it calls to mind a bunch of your other books. Like “Players” it begins in an airplane. The Super Bowl is a football connection to “End Zone.” There’s a cataclysmic event as in “White Noise.” There’s even a quick back-and-forth in which two characters try to remember details about the scientist Celsius, which is close to a back-and-forth in your short story “Midnight in Dostoevsky,” where people are trying to remember something about Celsius. Is that all a coincidence?

I don’t think in terms of connection between books. Except perhaps that the assassination of President Kennedy mysteriously turns up in a roundabout way at the end of my first novel, “Americana.” The character drives his car along the motorcade route that President Kennedy took. Then years later I decided it might be interesting to write a novel based on the assassination of President Kennedy. This was a major decision, and it required me to do an enormous amount of research. Curiously enough I ended up in the Bronx, where I was born and grew up, because I learned that Lee Oswald had spent a year in the Bronx with his mother, living within walking distance of where I lived. I went to visit his old neighborhood. Maybe that is what got me started on “Libra.” I decided to name the novel after his birth sign. I was hoping it was Scorpio, because I liked that word. But his birth sign turned out to be Libra, the scales. I settled for that.

Let me get back to themes from your work: paranoia, conspiracy, information overload. None of these things have become any less potent, which is part of what accounts for the prophetic qualities people see in your books. What do you take from seeing your themes continue to play out in the world with such force?

Well, I thought of the entire set of decades after the Kennedy assassination as the age of paranoia. For people of my age or perhaps a little younger, this is what overtook the entire culture. People were paranoid about everything, and suddenly there were all the books, the studies of the assassination. I have an entire library shelf, including the 26 volumes of the Warren Report, half of which I read fairly thoroughly when I was working on “Libra.” It consumed the culture. That’s not an exaggeration. After 11/22/63 everybody began to think in terms of paranoia. Then it was gone.

You think the culture has not become more paranoid?

We could say that there was a conspiratorial element in the current situation in the pandemic but I’m not sure how seriously the commentators and students of this era take it. Otherwise, I think that sense of conspiracy is less prevalent now than it used to be.

Revisiting the assassination for Rolling Stone in 1983, DeLillo wrote, “What has become unraveled since that afternoon in Dallas is not the plot, of course, not the dense mass of characters and events, but the sense of a coherent reality most of us shared.”

In his Harper’s Magazine essay “In the Ruins of the Future,” published in the wake of the terrorist attacks, DeLillo wrote: “Today, again, the world narrative belongs to terrorists. . . . Our world, parts of our world, have crumbled into theirs, which means we are living in a place of danger and rage.”

In the past you’ve written about how fundamentally JFK assassination and 9/11 altered our understanding of the world. Will the pandemic change our structure of feeling?

Absolutely. The question is how will it change? When we are finally able to live, so to speak, normally again, which is probably a long way off, how will we think back upon the pandemic? Are we going to continue to be affected by it? I think we have to be in some way. We may feel enormous relief, but for many people, it’s going to be difficult to return to what we might term as ordinary. I don’t know how that’s going to feel. I hope that it’s mainly a sense of rediscovered freedoms. You want to go to a movie. You want to go to a museum and eat in a restaurant. Those ordinary things are going to seem extraordinary.

You’ve been in Manhattan during the pandemic. What are your impressions of the city?

If I take a walk, a street that has four people on it will seem almost crowded. We’re supposed to be wearing masks, not everyone does, and one has to veer away from certain people. One has to be consciously aware of who’s coming toward us. Who’s behind us. As much as an individual might look forward to going out for a while, these self-imposed restrictions begin to assert themselves and whatever pleasure one anticipated may not be experienced fully.

That sounds exactly like something from your novels.

Honestly, I’m not aware of that. I’m just babbling.

Characters babble in your novels, too! See, it’s all connected!

It is all connected. ~

Oriana:

There is no arguing with the fact that the JFK assassination, 9/11, and now Covid have had a deep impact on us, and the collective psyche will never be the same. Our attitude toward reality has changed. The old innocent expectation of a stable world that makes sense is gone. Is this indeed a terrorist's narrative? Or is paranoia past its peak?

Even if it's the latter, we have a new sense of our own fragility. We know that the worst could indeed happen.

from another source:

~DeLillo was still a child when he started positioning himself at what he describes in Underworld as "an angle to the moment". His parents moved separately from Italy to New York, where they met and in 1936 had a son. DeLillo supposes his parents' foreignness gave him a sense of detachment, a grain of perspective on American cultural life.

But that didn't register until adulthood. As a child, there wasn't room to cultivate a sense of separateness. "We were in very crowded circumstances, in a skinny little house in the Bronx that still stands. There were five people upstairs - my uncle and aunt and my three male cousins; four of us and my grandparents, so there were 11 of us. No one ever complained, because it was what we knew." Books were not a part of this world. What DeLillo loved was "getting home from school, getting out to play ball. The neighborhood was densely populated, so there was always somebody, always something and always some kind of turmoil, aggression, commotion going on.”

DeLillo populates his books with cranks, drop-outs, recluses, obsessives — in his novel, Cosmopolis, the protagonist a suicidal billionaire named Eric Packer. Above all, these are people who live by the first principle of paranoia: that everything in the world is connected to everything else. Since it is also a principle of the artist, there has been confusion over the years as to which category DeLillo falls into. "History is the sum total of all the things they aren't telling us," he wrote in Libra, his fictionalized account of the Kennedy assassination, although he is personally more in tune with the sentiment: "A shrewd person would one day start a religion based on coincidence, if he hasn't already, and make a million."

His popularity with a certain pedantic strain of male graduate has seen him characterized, unfairly, as a man who writes about men for men — not in the macho tradition of Philip Roth or Norman Mailer, but as distant and slick, dysfunctionally male, heartless. Reviewing Cosmopolis in these pages, Blake Morrison argued that "The heroes of novels don't have to be likable, and as the epitome of disengagement, cut off from common pursuits and recognizable feelings, Packer isn't someone we're meant to engage with.”

*

DeLillo’s father worked as a payroll clerk in the Metropolitan Life insurance company, "a blue-collar man, who ended up wearing a tie to work". There was no money. The football the children played with in the street was made from newspaper bound with tape. Love of ball games, especially baseball, has been a constant in DeLillo's life, signaling to his peers the "street-level" nature of his interests and surfacing in his books as a preoccupation with crowds, common moods, mass hysteria.

Although he has a college degree in what he scathingly refers to as "something called communication arts", DeLillo is essentially self-taught. His books, he says, are not for academics but for "an anonymous person somewhere in a small town." ~

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2003/may/24/fiction.dondelillo

According to DeLillo, the novel's title came to him as he thought about radioactive waste buried deep underground and about Pluto, the god of death.

*

“In America we have only the present tense.

I am in danger. You are in danger.”

~ Adrienne Rich

*

“It will be easy for us once we receive the ball of yarn from Ariadne (love) and then go through all the mazes of the labyrinth (life) and kill the monster. But how many are there who plunge into life (the labyrinth) without taking that precaution?” ~ Kierkegaard

Oriana:

I suspect that by “monster” Kierkegaard means despair. For me personally, one’s vocation is the kind of love that can guide and protect. But the love in the sense of affection that we give and receive also guides and protects.

By the way, it's not that we “choose” to plunge into the labyrinth of life with or without Ariadne's thread. We are forced to plunge whether or not we have Ariadne's thread, i.e. have received enough love — or have found our vocation/talents already in childhood, and had the ability to develop those talents and pursue that vocation.

*

THE BRAIN-BASED REASON MOTIVATION MAY FAIL IN OLDER AGE

~ A recent Norwegian study (Sigmundsson, 2020) of almost a thousand women and men between the ages of 14 and 77 found that shortly after the early 50s, participants tended to show a sharp decline in passion, perseverance, and positive mindset about the worthwhileness of pursuing new challenges. (See "Passion, Grit, and a Can-Do Attitude Keep the Spark Lit.")

Although Sigmundsson mentions that his findings 'align with neuropsychology,' his research doesn't unearth specific brain-based reasons that may cause people's motivation to fizzle with age. Coincidentally, a new study (Friedman et al., 2020) using specially engineered mice sheds light on how specific circuits in the basal ganglia tied to dopamine-driven, reward-seeking behaviors become less robust with age. These findings were published on October 27 in the journal Cell.

"As we age, it's harder to have a get-up-and-go attitude toward things," senior author Ann Graybiel of MIT's McGovern Institute for Brain Research said in a news release. "This get-up-and-go, or engagement, is important for our social well-being and for learning—it's tough to learn if you aren't attending and engaged."

For their latest study, Graybiel and colleagues used the same strain of mice to investigate how varying degrees of activity in the basal ganglia's striosomes affect the cost-benefit analysis of the pros and cons associated with investing time and energy into a specific endeavor; this type of decision-making dilemma is called an approach-avoidance conflict.

Approach-avoidance conflicts arise when a goal or task has negative and positive characteristics that make pursuing these activities simultaneously unappealing and appealing. For example, vigorous HIIT workouts can feel like a sufferfest when you're huffing and puffing, but breaking a sweat doing cardio is often followed by a euphoric cannabinoid-driven runner's high, which makes the 'blood, sweat, and tears' of high-intensity interval training exercise worth the effort for many people.

When faced with an approach-avoidance conflict, the brain has to decide if "taking the good with the bad" is worth it because the positive and negative elements of an approach-avoidance conflict are inherently linked.

Notably, the researchers found that, much like humans, older mice (of an age equivalent to that of people in their 60s) tend to lose their get-up-and-go enthusiasm about learning new things that require hard work and sacrifice. The researchers also found that older mice have weaker striosomal signals when evaluating high-cost and high-reward options.

In addition to typical age-related motivational declines, mental health factors such as clinical depression, PTSD, or generalized anxiety disorders can skew someone's ability to assess the costs and rewards of approach-avoidance conflicts objectively.

For example, someone experiencing a major depressive episode (MDE) may undervalue the potential reward of taking small steps to achieve goals in day-to-day life. On the flip side, someone with a substance use disorder may overvalue the short-term rewards of using drugs or alcohol but undervalue the long-term expense of addiction in other aspects of their life.

The next phase of striosomes research by Graybiel and colleagues will explore possible pharmaceuticals or drug-free biofeedback interventions that hack into these brain circuits in ways that optimize value-based learning and improve cost-benefit evaluations across a lifespan. ~

Oriana:

Dopamine is the first neurotransmitter to decline with age. This can be somewhat beneficial: we speak about the “mellowing” in the elderly, who become more serotonin-dominant. But there can be a gradual loss of motivation to do basically anything — as in depression, life is simply not rewarding enough. Yet activities that used to be rewarding may be still accessible.

The drop in dopamine levels has so many consequences that it may be a sufficient reason for this drop in motivation.

People who are on serotonin-enhancing antidepressants sometimes report that they no longer care about things that used to be important to them, such as work or family life. Ideally, an anti-depressant shouldn’t affect the dopamine-serotonin ratio to point of loss of motivation.

By the way, if a person either takes cocaine or falls in love, the basal ganglia light up the same way. The same neural networks get activated by falling in love at ninety as at nineteen (yes, it’s possible to fall in love at any age).

Coffee and protein reliably raise dopamine levels. But humans are also guided by their past experience. I have women friends who have decided that "men are just not worth the trouble," and thus they have "retired" from dating. I know only one man who's "retired" from relationships — in his case, two unhappy marriages that ended in divorce seem to have discouraged him. Still, there is love in his life — for his grandchildren.

Mary:

*

WATERWORLD? SUPERIONIC BLACK ICE

~ The discovery of superionic ice potentially solves the puzzle of what giant icy planets like Uranus and Neptune are made of. They’re now thought to have gaseous, mixed-chemical outer shells, a liquid layer of ionized water below that, a solid layer of superionic ice comprising the bulk of their interiors, and rocky centers.

Recently at the Laboratory for Laser Energetics in Brighton, New York, one of the world’s most powerful lasers blasted a droplet of water, creating a shock wave that raised the water’s pressure to millions of atmospheres and its temperature to thousands of degrees. X-rays that beamed through the droplet in the same fraction of a second offered humanity’s first glimpse of water under those extreme conditions.

The X-rays revealed that the water inside the shock wave didn’t become a superheated liquid or gas. Paradoxically — but just as physicists squinting at screens in an adjacent room had expected — the atoms froze solid, forming crystalline ice.

The findings confirm the existence of “superionic ice,” a new phase of water with bizarre properties. Unlike the familiar ice found in your freezer or at the north pole, superionic ice is black and hot. A cube of it would weigh four times as much as a normal one. It was first theoretically predicted more than 30 years ago, and although it has never been seen until now, scientists think it might be among the most abundant forms of water in the universe.

Across the solar system, at least, more water probably exists as superionic ice — filling the interiors of Uranus and Neptune — than in any other phase, including the liquid form sloshing in oceans on Earth, Europa and Enceladus. The discovery of superionic ice potentially solves decades-old puzzles about the composition of these “ice giant” worlds.

Including the hexagonal arrangement of water molecules found in common ice, known as “ice Ih,” scientists had already discovered a bewildering 18 architectures of ice crystal. After ice I, which comes in two forms, Ih and Ic, the rest are numbered II through XVII in order of their discovery. (Yes, there is an Ice IX, but it exists only under contrived conditions, unlike the fictional doomsday substance in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle.)

Superionic ice can now claim the mantle of Ice XVIII. It’s a new crystal, but with a twist. All the previously known water ices are made of intact water molecules, each with one oxygen atom linked to two hydrogens. But superionic ice, the new measurements confirm, isn’t like that. It exists in a sort of surrealist limbo, part solid, part liquid. Individual water molecules break apart. The oxygen atoms form a cubic lattice, but the hydrogen atoms spill free, flowing like a liquid through the rigid cage of oxygens.

Depending on whom you ask, superionic ice is either another addition to water’s already cluttered array of avatars or something even stranger. Because its water molecules break apart, said the physicist Livia Bove of France’s National Center for Scientific Research and Pierre and Marie Curie University, it’s not quite a new phase of water. “It’s really a new state of matter,” she said, “which is rather spectacular.”

https://www.quantamagazine.org/black-hot-superionic-ice-may-be-natures-most-common-form-of-water-20190508/

Ice XVIII is "an oxygen ion crystal swimming in a sea of protons" ~ Chemistry World

*

OUR CHANGING NOTION OF THE NEANDERTHAL

~ That another sort of human entirely had once walked the Earth was a deeply shocking fact, one among a volley of disturbing threats lobbed by science against the notion that the cosmos centered on us, Homo sapiens. From 1856—the year they were first noticed—until the present day, Neanderthals have consistently been framed in opposition to us, not as fellow travelers along evolution’s swift and mighty cataract.

But archaeology as a discipline wasn’t paying attention to the role we wished to cast Neanderthals in. Instead, it was busily learning how to do more than simply collect beautiful stony trinkets and arrange them in shape order. Now, we can zoom out from the micro-layers of a single hearth whose embers last glowed in Iberia 90,000 years ago, to the secrets of continental-scale population movements buried in DNA from a Neanderthal woman living around the same time, thousands of miles east in Siberia. Today’s vision of these ancient relations is as distant from old views of Neanderthals—unintelligent cave thugs, the losers of our family tree—as modern astronomy is from the idea of a universe bounded by the Milky Way. And what 21st century archaeology paints is a truly compelling portrait, of another kind of human, traveling their own path.

Particularly in the last three decades, many conventional theories about Neanderthals have been exploded. For example, for much of the past 160 years, it was believed they were specifically adapted to extreme cold; now we know that their environmental range was far broader, and they didn’t really enjoy hyper-frigid conditions. This variety of environments brought with it a massive diversity in ways to make a living. Neanderthals were top hunters who took on prey ranging from true mega-fauna like mammoths and woolly rhinos to small game. Whether hunting or foraging, a deep knowledge of the world guided them—they knew the best way to take apart a reindeer, how to roast a tortoise or where to gather water-lily roots.

Neanderthals were also keenly concerned with the characteristics of materials—most obviously rock. Stone tools connected every aspect of life. They sliced, chopped and scraped the food they ate, the clothing they wore, the fuel that kept the darkness at bay. Patterns from many hundreds of archaeological sites show they understood how different rock types required varying approaches for knapping, and were flexible enough to alter and combine techniques for acquiring the sorts of flakes—and sometimes blades and points—they were after. Study of other materials, such as wood, reveals the same impression of knowledgeable craft. Nor did they use that knowledge for tools alone. While standards of proof are justifiably high (although often more stringent than we demand from early H. sapiens contexts), there do seem to be some striking hints that their material engagements went beyond the functional. For example, a fossil shell from an Italian site dating around 55,000 years ago must have been originally found by a Neanderthal some 60 miles away from the site, and its outer surface bears red pigment, itself sourced from 25 miles away.

Recent discoveries even challenged the Neanderthal “fact” about which we were most certain: their extinction. That changed when in 2010 the first nuclear genome revealed that, rather than their being distant cousins we’d shoved aside by 40,000 years ago, ancient interbreeding had left a genetic Neanderthal legacy in most living people. Of course, it’s obvious that Neanderthals aren’t “still here” in a full sense; since we still look like ourselves, there cannot have been a total Borg-style assimilation. But neither are they totally extinguished.

Indeed, the story we like to tell ourselves about our success and their failure is looking less clear-cut in other ways. It now seems that the span of time during which early H. sapiens dispersed out of Africa is far greater than once believed, reaching back before 150,000 years ago and featuring many phases of baby-making. Yet those early explorers of Eurasia vanished into evolutionary oblivion, leaving virtually no surviving DNA lineages visible in people today, and were replaced themselves by multiple waves of later populations. Early Homo sapiens, in other words, weren’t fundamentally better at surviving than Neanderthals were.

What does this new view of Neanderthals teach us? In many ways they were super resilient. We know they were flexible, adaptable survivors who weathered repeated and extreme climate change. Around 120,000 years ago, this even included a world warmer than today, by some 2–4°C and with sea-levels up to 8 meters higher—precisely where we are headed in the next few centuries if we don’t make a drastic change now.

But something did shift during their final ten millennia, between 50-40,000 years ago. Rather than a single cause for their dying out, it’s looking as if Neanderthals were caught in a many-angled vise. Intensifying climate chaos was part of that. And there probably was something qualitatively different in their H. sapiens contemporaries, potentially better hunting technologies and greater social connectivity, which crowded them out. Perhaps, even as the last hybrid babies were being conceived, something else more dangerous was exchanged; finishing writing my book about Neanderthals in spring 2020 made it impossible to disregard the possibility that our species may have brought some deadly pathogen into the equation. Or it might all however have come down to nothing more dramatic than a slow fading away, and whatever the details, the Neanderthals’ end undoubtedly unfolded in different ways across their huge geographic realm, from France to Central Asia and beyond.

By 30,000 years ago, there were no more Neanderthals. Nor were there any of the other ancient hominin species who had populated Eurasia. From the Cape of Good Hope to the Blue Mountains of Australia, our H. sapiens ancestors were alone on Earth. This point has typically been framed as a victory of our species, a vision in which we are the successful explorers or conquerors, but maybe it was the opposite. We once witnessed—perhaps caused—the elimination of our closest relations. Now, tens of millennia later, we are waking up to what else we’re on the brink of losing. For the sake of both the future and past generations we bear within us, let’s learn a new way to be resilient while treading lightly—a new path to being human.

Mary:

*

COLORING BOOKS: NOT CREATIVITY BUT SUBMISSION?

~ What if the recent popularity of coloring books comes not from the creativity they purportedly inspire, but from the submission they induce? This, after all, has been their mission from the start. It may be lost to the fans of coloring books that their success peaked in the 19th century, when such publications taught children how to behave. And obedience seems to be what many of us crave in these pandemic days. The Little Folks Painting Book—often described as the first coloring book—invited one to paint the illustrations of songs and tales about the harms of waking up late, being selfish, or playing a trick on your well-mannered cousin.

The last story of the book is particularly revealing. It is about a brother and sister who wish to fly away from their boring, secluded life and are magically held captive on flying carpets that take them on a journey that never ends, a Dantesque hell of punishment that comes with the warning: “Never be discontented, never wish for anything you cannot have.” Doesn’t this sum up what coloring books are about: Stay within the lines?

Historically, coloring has often been considered inferior to drawing. In Renaissance Florence, when artists dissected their differences as a way to show that they were not artisans but intellectuals mastering their craft, drawing was singled out as the artistic equivalent of thinking. Artists were expected to spend hours working out compositions because it is through them—where to place figures? how to draw them?—that they won praise.

Coloring did matter. Reddening the cheeks of figures brought the miracle of life to a work of art. Yet colors were applied at a second stage, a lesser stage, as shown by a Leonardo da Vinci sketch of a hanged renegade, next to which he listed the dyes of his fur-trimmed outfit.

Such bifurcation was not lost on Henry Peacham, author of The Compleat Gentleman of 1622, perhaps the first book to advertise the benefits of coloring. Peacham believed that a well-educated gentleman had to master drawing. Still, he also recommended spending time coloring, “for the practice of the hand doth speedily instruct the mind, and strongly confirm the memory beyond anything else.” Which is to say: Painting is a way not to invent but to learn and internalize. In particular, Peacham recommended painting maps as a way to learn capital cities and geopolitical boundaries (this at a time when borders were more violently contested than today). He promoted coloring as a way to accept a world assembled by rulers, and not just accept it but to yearn for it and delight in its preservation. Coloring was for him, as it was becoming to me, a means to maintain the political status quo.

To color is to inhabit a world designed by others, to dwell in an environment where you are left with no options but to memorize what is already there. But I am in no need to be reminded of what a small, limited life feels like: I live it and am tired of it. I am even more tired of the tamed fantasies that coloring books want me to make my own.

They are mostly consolatory, rather than empowering. In the early 1980s, we colored automobiles, the dreams of careerists. A few years ago, we colored Ryan Gosling, asking you out on a date. Today we color unicorns, campfires, and storefronts full of stuff.

After days of coloring these diminutive dreams, I came to see the energy I spent on it as dimming my capacity to imagine how a future can be conceived and built. So I deleted my app. And if in these days of stillness and isolation you are offered a coloring book, my suggestion is: Rip it up and reassemble its fragments as a collage. That is the true artistic outlet for those who do not want to accept the world as it is but want to make it wildly anew without depleting its resources. ~

https://slate.com/culture/2020/08/coloring-books-history-coronavirus.html?utm_source=pocket-newtab

THE GRAMMAR OF SOUL — NOUN OR VERB?

Nicholas of Tolentino (Italian: San Nicola da Tolentino) (c. 1246 – September 10, 1305), known as the Patron of Holy Souls, was an Italian saint and mystic. He is particularly invoked as an advocate for the souls in Purgatory, especially during Lent and the month of November. In many Augustinian churches, there are weekly devotions to St Nicholas on behalf of the suffering souls. November 2, All Souls' Day, holds special significance for the devotees of St. Nicholas of Tolentino. [Oriana: November 1 is All Saints' Day. All Souls' is officially celebrated the day after All Saints; regional practice may differ]

San Nicolas de Tolentino; Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, 1601.

The idea of Purgatory has been very lucrative for the church, which charges for the masses for the dead. I won’t go into the history of indulgences (a purchased reduction of the soul’s term in Purgatory), which ultimately led to the Reformation.

The basic error is to think of the soul as a thing, a noun — rather than as a process, a verb. The prevalent Christian idea of a soul is that of a something that gets inserted into the body at conception (or shortly after), and that something leaves the body at the moment of death to meet with judgment (not yet the Last Judgment) that will assign it to hell, purgatory, or heaven.

In ancient Judaism, the soul died with the body. Life began with the first breath and ended with the last one. God had the power to resurrect the dead, but this a rather exceptional phenomenon.

The modern secular idea of the soul (if that word is ever used) is that it’s a brain function, comparable to a candle flame. When a candle burns out, we don’t ask “Where does the flame go?” The flame was a process going on as long as there was enough fuel in the wick and enough oxygen to sustain the burning.

After a movie is over, we don’t ask, “Where did the movie go?” We know it ceased to be projected.

It’s said that the dead live in our memory and “visit us” in our dreams; famous authors and artists are said to live in their works; the Founding Fathers live on in history. But we understand that in those cases the verb “live” is used in a metaphorical way.

The idea that the dead actually continue to lead an independent, body-free existence is a form of wishful thinking so common that it’s pretty hopeless to oppose it. Our language is permeated with the idea of the immortal soul. In addition, many Americans (especially Republicans, according to Newsweek) literally believe in ghosts, demons, vampires, and other supernatural entities.

And that idea is so attractive and magical (e.g. communicating with the dead) that even secular writers and poets use it — including me in the opening poem of this blog. I could defend the poem by invoking the power of image, the power of metaphor — but let’s face it, the notion of ghosts has been a boon to literature (like mythology in general). Even people who are willing to admit that all religions are a fiction may be reluctant to extend the label of “fiction” to the disembodied soul. Again, the problem is seeing the soul as a thing or a being — in any case, a noun.

Diego Rivera, Day of the Dead, 1944

*

PASCAL WASN’T THE ONLY ONE TO FORMULATE THE WAGER

It turns out that Pascal wasn’t the only one to formulate the wager. “Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali, was narrated as having said: "The astrologers and the physicians both said the dead will never be resurrected. I said, 'Keep your council. If your idea is correct, I will come to no harm by my belief in the Day of Judgement, but if my belief is correct then you will be a sure loser by not believing in that day.'" (Narrated in Ihya of Al-Ghazali)”

The mention of Islam of course brings up the “many religions” objection to Pascal’s wager. I’ve discovered only now that Pascal was aware of this counterargument. He dismissed pagan religions as manifestly wrong as can be seen by their extinction and/or by the inferiority of the cultures that practice them. Judaism has been superseded by Christianity. And as for Islam — Pascal is at his weakest here — well, if we examine it carefully, Islam just can’t be true.

Of course if we examine it carefully, Christianity can’t be true either — hence the pitiful state of uncertainty that Pascal mentions. Pascal was a brilliant thinker, but in this realm he was too intimidated by the threat of hell to keep pressing. As for the very recent argument that says, “The extent of god’s mercy toward the dead is not known to us,” it was too early for such advanced thinking in the spirit of kindness. The child of the brutal severity of his times, Pascal settled for the wager.

Once I was delighted by the “many religions” refutation of Pascal’s wager. But a more general refutation posits that all religions are human inventions; they are archaic philosophy and “theory of everything.” Not one has sufficient evidence to support supernatural claims.

There remain two strong theological arguments against Pascal’s wager. First, a deity worthy of worship would probably judge on the basis of ethics rather than correct doctrine, which is chiefly an accident of birth: those born in Saudi Arabia are Muslim, those born in Ireland are Catholic, those born in Greece are Greek Orthodox, and so on. Second, there is no hell. The barbarous idea has been dismissed even by Pope John Paul 2, who has redefined heaven and hell as not places, but states of mind that can be experienced right here on earth. Heaven is a loving state of mind, while hell is a state of mind filled with hatred and negativity.

While the Pope added that “Heaven is also the person of God,” that doesn’t seem as convincing as the statement that heaven is not a place, but a loving state of mind. It might even be argued that a loving state of mind IS god — “the kingdom of heaven is within you.” A state of mind filled with loving kindness can be attained without any dogmatic beliefs about virgin birth or resurrection in the body. Thus, we don’t need Pascal’s wager: we can enjoy heaven right here on earth.

*

THE GREAT PLAGUE OF ATHENS

~ One such description [of the plague] sits at the very beginning of western literature. Homer’s Iliad, (around 700 B.C.), commences with a description of a plague that strikes the Greek army at Troy. Agamemnon, the leading prince of the Greek army, insults a local priest of Apollo called Chryses.

Apollo is the plague god – a destroyer and healer – and he punishes all the Greeks by sending a pestilence among them. Apollo is also the archer god, and he is depicted firing arrows into the Greek army with a terrible effect:

Apollo strode down along the pinnacles of Olympus angered

in his heart, carrying on his shoulders the bow and the hooded

quiver; and the shafts clashed on the shoulders of the god walking angrily. …

Terrible was the clash that rose from the bow of silver.

First he went after the mules and the circling hounds, then let go

a tearing arrow against the men themselves and struck them.

The corpse fires burned everywhere and did not stop burning.

Plague Narratives

About 270 years after the Iliad, or thereabouts, plague is the centerpiece of two great classical Athenian works – Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, and Book 2 of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War.

Thucydides (c.460-400 B.C.) and Sophocles (490-406 B.C.) would have known one another in Athens, although it is hard to say much more than that for a lack of evidence. The two works mentioned above were produced at about the same time. The play Oedipus was probably produced about 429 B.C., and the plague of Athens occurred in 430-426 B.C.

Thucydides writes prose, not verse (as Homer and Sophocles do), and he worked in the comparatively new field of “history” (meaning “enquiry” or “research” in Greek). His focus was the Peloponnesian war fought between Athens and Sparta, and their respective allies, between 431 and 404 B.C.

Thucydides’ description of the plague that struck Athens in 430 B.C. is one of the great passages of Greek literature. One of the remarkable things about it is how focused it is on the general social response to the pestilence, both those who died from it and those who survived.

The description of the plague immediately follows on from Thucydides’ renowned account of Pericles’ Funeral Oration (it is important that Pericles died of the plague in 429 B.C., whereas Thucydides caught it but survived).

Thucydides gives a general account of the early stages of the plague – its likely origins in north Africa, its spread in the wider regions of Athens, the struggles of the doctors to deal with it, and the high mortality rate of the doctors themselves.

Nothing seemed to ameliorate the crisis – not medical knowledge or other forms of learning, nor prayers or oracles. Indeed “in the end people were so overcome by their sufferings that they paid no further attention to such things”.

He describes the symptoms in some detail – the burning feeling of sufferers, stomachaches and vomiting, the desire to be totally naked without any linen resting on the body itself, the insomnia and the restlessness.

The next stage, after seven or eight days if people survived that long, saw the pestilence descend to the bowels and other parts of the body – genitals, fingers and toes. Some people even went blind.

Words indeed fail one when one tries to give a general picture of this disease; and as for the sufferings of individuals, they seemed almost beyond the capacity of human nature to endure.

Those with strong constitutions survived no better than the weak.

The most terrible thing was the despair into which people fell when they realized that they had caught the plague; for they would immediately adopt an attitude of utter hopelessness, and by giving in in this way, would lose their powers of resistance.

Lastly, Thucydides focuses on the breakdown in traditional values where self-indulgence replaced honor, where there existed no fear of god or man.

As for offenses against human law, no one expected to live long enough to be brought to trial and punished: instead everyone felt that a far heavier sentence had been passed on him.

The whole description of the plague in Book 2 lasts only for about five pages, although it seems longer.

The first outbreak of plague lasted two years, whereupon it struck a second time, although with less virulence. When Thucydides picks up very briefly the thread of the plague a little bit later (3.87) he provides numbers of the deceased: 4,400 hoplites (citizen-soldiers), 300 cavalrymen and an unknown number of ordinary people.

Nothing did the Athenians so much harm as this, or so reduced their strength for war.

A Modern Lens

Modern scholars argue over the science of it all, not the least because Thucydides offers a generous amount of detail of the symptoms.

Epidemic typhus and smallpox are most favored, but about 30 different diseases have been posited.

The lessons that we learn from the coronavirus crisis will come from our own experiences of it, not from reading Thucydides. But these are not mutually exclusive. Thucydides offers us a description of a city-state in crisis that is as poignant and powerful now as it was in 430 B.C. ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/thucydides-and-the-plague-of-athens-what-it-can-teach-us-now?utm_source=pocket-newtab

from Wikipedia:

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, the historian Thucydides, who was present and contracted the disease himself and survived, describes the epidemic. He writes of a disease coming from Ethiopia and passing through Egypt and Libya into the Greek world and spreading throughout the wider Mediterranean; a plague so severe and deadly that no one could recall anywhere its like, and physicians ignorant of its nature not only were helpless but themselves died the fastest, having had the most contact with the sick. In overcrowded Athens, the disease killed an estimated 25% of the population. The sight of the burning funeral pyres of Athens caused the Spartans to withdraw their troops, being unwilling to risk contact with the diseased enemy. Many of Athens' infantry and expert seamen died. According to Thucydides, not until 415 BC had Athens recovered sufficiently to mount a major offensive, the disastrous Sicilian Expedition.

The first corroboration of the plague was not revealed until 1994-95 where excavation revealed the first mass grave. Upon this discovery, Thucydides' accounts of the event as well as analysis of the remains had been used to try and identify the cause of the epidemic.

Accounts of the Athenian plague graphically describe the social consequences of an epidemic. Thucydides' account clearly details the complete disappearance of social morals during the time of the plague:

...the catastrophe was so overwhelming that men, not knowing what would happen next to them, became indifferent to every rule of religion or law.”

— Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

The perceived impact of the Athenian plague on collective social and religious behavior echoes accounts of the medieval pandemic best known as the Black Death, although scholars have disputed its objective veracity in both instances, citing a historical link between epidemic disease and unsubstantiated moral panic that bordered on hysteria.'

Fear of the law

Thucydides states that people ceased fearing the law since they felt they were already living under a death sentence. Likewise, people started spending money indiscriminately. Many felt they would not live long enough to enjoy the fruits of wise investment, while some of the poor unexpectedly became wealthy by inheriting the property of their relatives. It is also recorded that people refused to behave honorably because most did not expect to live long enough to enjoy a good reputation for it.

Care for the sick and the dead

Another reason for the lack of honorable behavior was the sheer contagiousness of the illness. Those who tended to the ill were most vulnerable to catching the disease. This meant that many people died alone because no one was willing to risk caring for them. The dead were heaped on top of each other, left to rot, or shoved into mass graves. Sometimes those carrying the dead would come across an already burning funeral pyre, dump a new body on it, and walk away. Others appropriated prepared pyres so as to have enough fuel to cremate their own dead. Those lucky enough to survive the plague developed an immunity and so became the main caretakers of those who later fell ill.

A mass grave and nearly 1,000 tombs, dated between 430 and 426 BC, have been found just outside Athens' ancient Kerameikos cemetery. The mass grave was bordered by a low wall that seems to have protected the cemetery from a wetland. Excavated during 1994–95, the shaft-shaped grave may have contained a total of 240 individuals, at least ten of them children. Skeletons in the graves were randomly placed with no layers of soil between them.

Excavator Efi Baziotopoulou-Valavani, of the Third Ephoreia (Directorate) of Antiquities, reported that "[t]he mass grave did not have a monumental character. The offerings we found consisted of common, even cheap, burial vessels; black-finished ones, some small red-figured, as well as white lekythoi (oil flasks) of the second half of the 5th century BC. The bodies were placed in the pit within a day or two. These [factors] point to a mass burial in a state of panic, quite possibly due to a plague.”

During this time refugees from the Peloponnesian war had immigrated within the Long Walls of Athens, inflating the populations of both the polis of Athens and the port of Piraeus. The population had tripled in this time increasing the chance of infection and worsening hygiene.

Religious strife

The plague also caused religious uncertainty and doubt. Since the disease struck without regard to a person's piety toward the gods, people felt abandoned by the gods and there seemed to be no benefit to worshiping them. The temples themselves were sites of great misery, as refugees from the Athenian countryside had been forced to find accommodation in the temples. Soon the sacred buildings were filled with the dead and dying. The Athenians pointed to the plague as evidence that the gods favored Sparta, and this was supported by an oracle that Apollo himself (the god of disease and medicine) would fight for Sparta if they fought with all their might. An earlier oracle had warned that “A Dorian [Spartan] war will come, and bring a pestilence with it.”

Thucydides is skeptical of these conclusions and believes that people were simply being superstitious. He relies upon the prevailing medical theory of the day, Hippocratic theory, and strives to gather evidence through direct observation. He observed that carrion-eating birds and animals disappeared, though he leaves it an open question whether they died after eating the corpses or refused to eat them and were driven away:

All the birds and beasts that prey upon human bodies, either abstained from touching them (though there were many lying unburied), or died after tasting them. In proof of this, it was noticed that birds of this kind actually disappeared; they were not about the bodies, or indeed to be seen at all.

Aftermath

The plague was an unforeseen event that resulted in one of the largest recorded loss of life in ancient Greece as well as a breakdown of Athenian society. The balance of power between citizens had changed due to many of the rich dying and their fortunes being inherited by remaining relatives of the lower class. According to Thucydides, those who had become ill and survived were the most sympathetic to others suffering: believing that they could no longer succumb to any illness, a number of survivors offered to assist with the remaining sick. The plague had also contributed to Athens' overall loss of power and ability to expand. Many of the remaining Athenians were found to be metics (non-citizens) who had forged their documents or had bribed officials to hide their original status. A number of these people were reduced to slaves once they were caught. This resulted in stricter laws dictating who can become an Athenian citizen, reducing both their number of potential soldiers and amount of political power, but also a decline in treatment and rights for metics in Athens.

The plague dealt massive damage to Athens two years into the Peloponnesian War, from which it never recovered. Their political strength had weakened and morale among their armies as well as the citizens had fallen significantly. Athens would then go on to be defeated by Sparta and fall from being a major power in Ancient Greece.

Symptoms

According to Thucydides, the Plague of Athens, the illness began by showing symptoms in the head as it worked its way through the rest of the body. He also describes in detail the symptoms victims of the plague experienced.

Fever

Redness and inflammation in the eyes

Sore Throats leading to bleeding and bad breath

Sneezing

Loss of voice

Coughing

Vomiting

Pustules and ulcers on the body

Extreme thirst

Insomnia

Diarrhea

Possible causes

Historians have long tried to identify the disease behind the Plague of Athens. The disease has traditionally been considered an outbreak of the bubonic plague in its many forms, but reconsideration of the reported symptoms and epidemiology have led scholars to advance alternative explanations. These include typhus, smallpox, measles, and toxic shock syndrome.

Based upon striking descriptive similarities with recent outbreaks in Africa, as well as the fact that the Athenian plague itself apparently came from Africa (as Thucydides recorded), Ebola or a related viral hemorrhagic fever has been considered.

Given the possibility that profiles of a known disease may have changed over time, or that the plague was caused by a disease that no longer exists, the exact nature of the Athenian plague may never be known. In addition, crowding caused by the influx of refugees into the city led to inadequate food and water supplies and a probable proportionate increase in insects, lice, rats, and waste. These conditions would have encouraged more than one epidemic disease during the outbreak.

Typhus

In January 1999, the University of Maryland devoted their fifth annual medical conference, dedicated to notorious case histories, to the Plague of Athens. They concluded that the disease that killed the Greeks was typhus. "Epidemic typhus fever is the best explanation," said Dr. David Durack, consulting professor of medicine at Duke University. "It hits hardest in times of war and privation, it has about 20 percent mortality, it kills the victim after about seven days, and it sometimes causes a striking complication: gangrene of the tips of the fingers and toes. The Plague of Athens had all these features.” In typhus cases, progressive dehydration, debilitation and cardiovascular collapse ultimately cause the patient's death.

Viral hemorrhagic fever

Thucydides' narrative pointedly refers to increased risk among caregivers, more typical of the person-to-person contact spread of viral hemorrhagic fever (e.g., Ebola virus disease or Marburg virus) than typhus or typhoid. Unusual in the history of plagues during military operations, besieging Spartan troops are described as not having been afflicted by the illness raging near them within the city. Thucydides' description further invites comparison with VHF in the character and sequence of symptoms developed, and of the usual fatal outcome on about the eighth day.

Outbreaks of VHF in Africa in 2012 and 2014 reinforced observations of the increased hazard to caregivers and the necessity of barrier precautions for preventing disease spread related to grief rituals and funerary rites. The 2015 west African Ebola outbreak noted persistence of effects on genitalia and eyes in some survivors, both described by Thucydides.

With an up to 21-day clinical incubation period, and up to 565-day infectious potential recently demonstrated in a semen-transmitted infection, movement of Ebola via Nile commerce into the busy port of Piraeus is plausible. Ancient Greek intimacy with African sources is reflected in accurate renditions of monkeys in art of frescoes and pottery, most notably guenons (Cercopithecus), the type of primates responsible for transmitting Marburg virus into Germany and Yugoslavia when that disease was first characterized in 1967.

Circumstantially tantalizing is the requirement for the large quantity of ivory used in the Athenian sculptor Phidias’ two monumental ivory and gold statues of Athena and of Zeus (one of the Seven Wonders), which were fabricated in the same decade. Never again in antiquity was ivory used on such a large scale.

A second ancient narrative suggesting hemorrhagic fever etiology is that of Titus Lucretius Carus. Writing in the 1st century BC, Lucretius characterized the Athenian plague as having "bloody" or black discharges from bodily orifices.

Unfortunately DNA sequence-based identification is limited by the inability of some important pathogens to leave a "footprint" retrievable from archaeological remains after several millennia. The lack of a durable signature by RNA viruses means some etiologies, notably the hemorrhagic fever viruses, are not testable hypotheses using currently available scientific techniques. ~

A DRAMATIC DROP IN COVID MORTALITY RATES

~ "We find that the death rate has gone down substantially," says Leora Horwitz, a doctor who studies population health at New York University's Grossman School of Medicine and an author on one of the studies, which looked at thousands of patients from March to August.

The study, which was of a single health system, finds that mortality has dropped among hospitalized patients by 18 percentage points since the pandemic began. Patients in the study had a 25.6% chance of dying at the start of the pandemic; they now have a 7.6% chance.

That's a big improvement, but 7.6% is still a high risk compared with other diseases, and Horwitz and other researchers caution that COVID-19 remains dangerous.

The death rate "is still higher than many infectious diseases, including the flu," Horwitz says. And those who recover can suffer complications for months or even longer. "It still has the potential to be very harmful in terms of long-term consequences for many people.”

Studying changes in death rate is tricky because although the overall U.S. death rate for COVID-19 seems to be dropping, the drop coincides with a change in whom the disease is sickening.

"The people who are getting hospitalized now tend to be much younger, tend to have fewer other diseases and tend to be less frail than people who were hospitalized in the early days of the epidemic," Horwitz says.

So have death rates dropped because of improvements in treatments? Or is it because of the change in who's getting sick?

To find out, Horwitz and her colleagues looked at more than 5,000 hospitalizations in the NYU Langone Health system between March and August. They adjusted for factors including age and other diseases, such as diabetes, to rule out the possibility that the numbers had dropped only because younger, healthier people were getting diagnosed. They found that death rates dropped for all groups, even older patients by 18 percentage points on average.

Doctors around the country say that they're doing a lot of things differently in the fight against COVID-19 and that treatment is improving. "In March and April, you got put on a breathing machine, and we asked your family if they wanted to enroll you into some different trials we were participating in, and we hoped for the best," says Khalilah Gates, a critical care pulmonologist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. "Six plus months into this, we kind of have a rhythm, and so it has become an everyday standard patient for us at this point in time."

Doctors have gotten better at quickly recognizing when COVID-19 patients are at risk of experiencing blood clots or debilitating "cytokine storms," where the body's immune system turns on itself, says Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease, critical care and emergency medicine physician who works at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

He says that doctors have developed standardized treatments that have been promulgated by groups such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

But Horwitz and Mateen say that factors outside of doctors' control are also playing a role in driving down mortality. Horwitz believes that mask-wearing may be helping by reducing the initial dose of virus a person receives, thereby lessening the overall severity of illness for many patients.

And Mateen says that his data strongly suggest that keeping hospitals below their maximum capacity also helps to increase survival rates. When cases surge and hospitals fill up, "staff are stretched, mistakes are made, it's no one's fault — it's that the system isn't built to operate near 100%," he says.

For these reasons, Horwitz and Mateen believe that masking and social distancing will continue to play a big role in keeping the mortality rate down, especially as the U.S. and U.K. move into the fall and winter months.

And many people will continue to die, even if the rate has dropped. A recent estimate by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation suggests the total death count could reach well over 300,000 Americans by February. ~

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/10/20/925441975/studies-point-to-big-drop-in-covid-19-death-rates

Oriana:

Though new cases have risen to record highs in the Midwest and Southeast, the covid mortality rate really is much lower now. In New York hospitals in August, it was 8%, down from 26% in March.

Again, increased mask-wearing may be a factor. As the article points out, mask-wearing may be helping by reducing the initial dose of virus a person receives, thereby lessening the overall severity of illness for many patients.

I'm still shocked by how many people wear their masks incorrectly, treating them as a weird chin holder, exposing their mouths and nose. It’s particularly important to cover the nostrils — that’s the main entry route for the virus.

Mary:

*

LOW-DOSE ASPIRIN SIGNIFICANTLY LOWERS COVID MORTALITY

~ Risk of complications and death among hospitalized COVID-19 patients who were taking prophylactic daily low-dose aspirin were significantly lower compared to patients who were not taking aspirin, according to findings of a study published on October 31, 2020 in the journal Anesthesia and Analgesia.

According to study authors from the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM), patients taking aspirin also were less likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) or to be placed on mechanical ventilation.

“If our finding is confirmed, it would make aspirin the first widely available, over-the-counter medication to reduce mortality in COVID-19 patients,” said study leader Jonathan Chow, MD, assistant professor of anesthesiology at UMSOM, in a university statement.

The retrospective observational cohort study tracked data from more than 400 patients (mean age 55 years) admitted with COVID-19 to one of 4 US hospitals between March 2020 and July 2020. Nearly 24% of patients received low-dose (81 mg) aspirin within 24 hours of hospital admission or 7 days prior to admission.

Researchers observed a 47% reduction in overall risk of in-hospital mortality in patients taking daily low-dose aspirin, a 44% reduction in risk of being placed on mechanical ventilation, and a 43% reduction in risk of ICU admission.

Adjustment for confounding variables included presence of age, gender, BMI, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, renal disease, liver disease, and home beta blocker use.

In the study’s Discussion the authors suggest that aspirin may mitigate the well-described hypercoagulable and prothrombotic state associated with CVOID-19 and also point to an earlier study that showed systemic anticoagulation with heparin can reduce mortality in mechanically ventilated patients.

But, until a large, randomized controlled trial can be conducted to confirm the study’s findings and asses the extent to which a causal relationship can be attribute to the one observed here, the authors say it is “imperative to exercise cautious optimism” and to always balance the known risks of aspirin against what could be a potential benefit in COVID-19 patients. ~

Oriana:

The risks of low-dose aspirin as compared to the risks of Covid, which include dying? The statement strikes me as absurd.

As for beta-blockers, it turns out that all types of drugs prescribed for hypertension reduce covid mortality.

*

ending on beauty:

Sometimes, when a bird cries out,

Or the wind sweeps through a tree,

Or a dog howls in a far-off farm,

I hold still and listen a long time.

My world turns and goes back to the place

Where, a thousand forgotten years ago,

The bird and the blowing wind

Were like me, and were my brothers.

My soul turns into a tree,

And an animal, and a cloud bank.

Then changed and odd it comes home

And asks me questions. What should I reply?

~ Hermann Hesse

No comments:

Post a Comment