skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Tara Turner: The Imagination of Trees. “A window is a transparent partition between my heart and the heart of the world.” ~ Marc Chagall

*

What a homecoming! Her father, a decade

off in distant lands fighting the good war,

expecting open arms, hugs, adulation, parades,

a final end to deployment—one of lucky few

to avoid traumatic brain injury,

or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

And no one to dare to press for details

about civilians shot, homes destroyed,

holy sites desecrated. Electra fails

to let her brother know that their father pillaged

the shrine and corralled a concubine,

not much older than Electra herself,

and crazy as a loon.

Electra fails to mention how, before he set sail,

facing sluggish winds, and because he had insulted

a goddess, he agreed to sacrifice his other daughter,

her sister—Iphigenia. Iphigenia, the real face—

lifeless and drained of blood—that launched

a thousand ships.

~ Leonard Kress, from Inventory of the Everyday Extreme

Iphigenia, the real face—

lifeless and drained of blood—that launched

a thousand ships.

I love the insight that it was Iphigenia's lifeless face that launched a thousand ships. What a fabulous riposte to Marlowe's famous lines.

*

SALLY HORNER, THE “REAL LOLITA”

*

SALLY HORNER, THE “REAL LOLITA”

~ “Sally Horner, a fifth-grade honor student, stole a 5-cent notebook in her local Camden, N.J., Woolworths on a dare by a clique of girls she hoped to join. As she was leaving the store, a "hawk-faced man" in a fedora grabbed her arm, told her he was an FBI agent and threatened her with reform school. Months later, in June 1948, the man, whose current alias was Frank La Salle, intercepted Sally on her walk home from school and convinced her that the government insisted she go with him to Atlantic City. He instructed Sally to tell her mother that he was the father of two school friends who had invited her on vacation. Scared, Sally lied to her mother, who gave her the OK. The next time Sally saw her family was 21 months later, in March 1950, shortly before her 13th birthday.

The man was known to the police as Frank La Salle. He had just been released from prison for raping five girls aged from 12 to 14. He took Sally on a 21-month odyssey from New Jersey to California, pretending she was his daughter. The abuse only ended when she managed to phone her family from San Jose in March 1950: “Tell Mother I’m OK and don’t worry. I want to come home. I’ve been afraid to call before.” La Salle spent the rest of his life in prison. Two years after she escaped, Sally was killed in a car crash. She was 15.

Sarah Weinman [the author of Real Lolita] interweaves the story of Sally's abduction and eventual rescue with Nabokov's writing of Lolita, which he had begun well before Sally's kidnapping and which had stymied him for years. She smartly discusses how the novel's preoccupation with pedophilia and prepubescent girls was presaged in some of Nabokov's earlier work — including Laughter in the Dark, The Gift, and his shockingly graphic 1928 poem, "Lilith," about an older man's intercourse with an "enticing ... unforgotten child." After two attempts to burn the manuscript (intercepted by his wife Véra), Nabokov finished Lolita in 1953, three years after Sally's liberation and a year after her death, at 15, in a car accident. It was first published abroad in 1955, and then in the United States in 1958 — when it became an immediate, incendiary commercial success.

Nabokov always denied that Sally's story influenced his novel, which he insisted was all art. "To admit he pilfered from a true story would be, in Nabokov's mind, to take away from the power of his narrative," Weinman writes. She argues that recognizing the connection doesn't diminish his remarkable achievement, "but it does augment the horror he also captured in the novel." Loaded words like "pilfered" and "strip-mined" clearly convey Weinman's attitude. In fact, Nabokov comes across in her book as an insufferable — if brilliantly inventive — snob, aesthete and egotist.

Weinman approaches her subject as if she were conducting a political inquiry: "My central quest with respect to Nabokov was to figure out what he knew about Sally and when he knew it," she writes. To this aim, she parses notecards on which Nabokov transcribed news of Sally's death in 1952 and Humbert Humbert's parenthetical remark about her in the novel: "Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank La Salle, a 50-year-old mechanic, had done to 11-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?" But she admits repeatedly that her argument relies heavily on circumstantial evidence and indirect proof.

Weinman is also on a mission to correct Lolita's millions of mis-readers, who bought Humbert's suave, wily contention that 12-year-old Dolores Haze was a seductive nymphet — and missed the horror of her nearly two-year ordeal. "Those who love language and literature are rewarded richly but also duped," she writes. "Lolita's trickery and mastery of obfuscation ... continue to make moral mincemeat out of the novel's wider readership."

So, too, does society's tendency to blame rape victims. Weinman reports that Sally suffered taunts and stigma after returning home and flags her mother's tone-deaf statement: "Whatever she has done, I can forgive her." Weinman appreciatively cites Véra Nabokov's diary entry expressing the wish that "somebody would notice the tender description of the child's helplessness ... and her heartrending courage.”

Heinemann unearths plenty of fascinating, often unexpected material, like the fact that the neighbor in the San Jose trailer park who helped rescue Sally ignored her own children's complaints of abuse by the many men in her life.

The Real Lolita stands out for its captivating mix of tenacious investigative reporting, well-chosen photographs, astute literary analysis and passionate posthumous recognition of a defenseless child who — until now — never received the literary acknowledgment she deserved.” ~

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/11/646656280/the-real-lolita-investigates-the-true-crime-story-of-sally-horner

Weinman on Sally after the rescue: ~ “[Her mother] said whatever Sally has done, I can forgive her. And I still remember reading that line for the first time. And every time I read that line, it's like a shiver goes up and down my spine because I can absolutely understand why she would have said that in the context of late 1940s, early 1950s and the fact that people just didn't recognize the effects of that kind of trauma. They didn't necessarily view girls like Sally in that situation as victims. The fact that after Sally came home and reintegrated back into life in Camden and instead of people viewing her with some degree of sympathy, they slut-shamed her. They claim — they said that because she wasn't a virgin anymore that she was essentially worthless, that she had a real hard time making friends. She wanted to have a boyfriend, and that was incredibly difficult.” ~

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/15/648214031/a-true-story-of-kidnap-and-rape-in-the-real-lolita

Sally Horner and her mother. Like Charlotte Haze in Lolita, Sally’s mother was a widow.

Sally Horner and her mother. Like Charlotte Haze in Lolita, Sally’s mother was a widow.

Mary:

I'm sure she was “asking for it.” Stories like this are not at all over. Witness the Kavanaugh debacle. I feel more than that chill. I feel rage.

*

“. . . the stern El Greco horizon, pregnant with inky rain, and passing glimpse of some mummy-necked farmer, and all around alternating stripes of quick-silverfish water and harsh green corn, the whole arrangement opening like a fan, somewhere in Kansas.” ~ Nabokov, Lolita

Oriana:

Lolita happened to be one of the very first novels I read in English, still in Warsaw. I think I just turned 16. One of my mother's friends had the Olympia edition, and with some hesitation lent the book to me (I was interested in the book strictly because it was in English; I didn't know what pedophilia was). I was so virginal that all kinds of naughty things went over my head, and I didn't even notice that evil was definitely at the core. But oddly enough, I did recognize that stylistically it was a masterpiece, and what particularly delighted me was the irony, and the ruthless descriptions of American pop culture.

What particularly unnerves me now that I bought Humbert's put-downs of Lolita as a vulgar teenager, and instantly fell in love with Humbert's eloquence. Humbert was brilliant, and I was in love with him from page one. Ten years later, it took a painful lesson for me to learn that a man can be brilliant yet evil, and that a good heart is more important than being a sparkling conversationalist.

*

~ “We are not much concerned, Mr. Humbird, with having our students become bookworms or be able to reel off all the capitals of Europe which nobody knows anyway.” ~ Headmistress Pratt in Lolita

Vienna

Vienna

*

Mary:

The story of Sally is a tragedy — not only because she was kidnapped and abused, but because her own mother, along with her classmates and her community, found her at fault for the evil that was done to her. Rape makes her guilty and worthless, someone who can at best “be forgiven” and relegated to the class of damaged property, unlikely to have takers in the marketplace where respectable and virtuous women find men to marry. And these judgements are not at all something we have grown out of. The shame, and the shaming, of sexual abuse victims continues at every level of society, all the way, as we have seen, to the highest levels of the judiciary. The confirmation of Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court is evidence of many things, none of them good, but most dramatically to how brutally the victim will be treated when her true testimony challenges the victimizer's right to power.

So what about art? What about Lolita? I'm not really interested in whether Nabokov knew Sally's story — of course he did, he even mentions it. But there are many many stories of this type, he didn't need to copy this, or any other particular one. And he had already been working on the book prior to Sally's story. What interests me is — why did he try to burn it? (And why did his wife rescue it?)

He wants to tell us “it's all art,” but that beautiful, elegant, wondrous castle of words is built on a very dark foundation. There is definitely “evil at the core.” And Humbert's verbal performance, his intellectual presence, is very much like the predator's elaborate smoke screens, the grooming and seduction of the reader very much like the grooming and seduction of the victim.

Does art have a moral dimension? I believe it does, like any other human production. And this can be recognized without having to resolve in censorship, even of art with that "evil at the core." The challenge is to see and respond to the whole . . . both the castle and its dark cellar, to understand and appreciate the dynamic between art and what it reflects as well as the dynamic between art and audience. All of which changes with time and culture.

Does beauty have a moral dimension? This seems much less evident to me. Evil can be painted, sung, spoken, with great beauty. There's Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Leni Riefensthal, or even the glories of magnificent churches where child predators were sheltered, and victims abandoned. Beauty is not truth, not when you're talking about moral truth, about good and evil. It has its own truths, in forms, order and integrity, and its own capacities to astonish, delight and persuade . Like beauty, with beauty, art seduces.

Oriana:

Leni Riefenstahl — yes, an example that makes me want to cry because feminists would certainly love to claim this gifted female filmmaker, to say, “Here is another great artist who happens to be a woman” — the way we can point to Georgia O’Keeffe. But an artist is not exempt from needing a moral compass . . .

I don’t suppose that Lolita encouraged pedophiles. It may sound odd, but that book is for the lovers of language. Without a doubt, there is evil at the core, a dark cellar in that wondrous castle — and we should be uneasy. I don’t think that a novel of this sort, written from the male point of view, would be published in our times. We do have a lot more understanding of the lifelong scars of sexual abuse — even though, as you point out, victimized women are often still shamed and blamed. So the majority of rapes are simply not reported.

Interestingly, Vera Nabokov always defended Lolita against the negative views of the “vulgar teenager” that were common after the novel was first published. Vera pointed out that Lolita was intelligent and resourceful, and eventually managed to escape. But perhaps the most interesting moment occurs toward the end of the book, when Humbert experiences a surprising (and perhaps not entirely convincing) insight (I hesitate to call it a moral awakening, but that's as close as he gets to it). He is passing a school; the children are outside at recess, and, being children, they are happily noisy in that high-pitched, chirpy way. And Humbert says to the reader: “Lolita’s voice would forever go missing from that concord.”

Leni Riefenstahl on the cover of time, 1936

Leni Riefenstahl on the cover of time, 1936

*

RENÉ GIRARD: THE SCAPEGOAT IDEA UNDERLYING SACRIFICIAL RELIGIONS

~ “The only thing more contagious than desire is violence. René Girard postulates that, prior to the establishment of laws, prohibitions, and taboos, prehistoric societies would periodically succumb to “mimetic crises.” Usually brought on by a destabilizing event — be it drought, pestilence, or some other adversity — mimetic crises amount to mass panics in which communities become unnerved, impassioned, and crazed, as people imitate one another’s violence and hysteria rather than responding directly to the event itself. Distinctions disappear, members of the group become identical to one another in their vehemence, and a mob psychology takes over. In such moments the community’s very survival is threatened by internecine strife and a Hobbesian war of all against all.

Girard interpreted archaic rituals, sacrifices, and myth as the symbolic traces or aftermath of prehistoric traumas brought on by mimetic crises. Those societies that saved themselves from self-immolation did so through what he called the scapegoat mechanism. Scapegoating begins with accusation and ends in collective murder. Singling out a random individual or subgroup of individuals as being responsible for the crisis, the community turns against the “guilty” victim (guilty in the eyes of the persecutors, that is, since according to Girard the victim is in fact innocent and chosen quite at random, although is frequently slightly different or distinct in some regard). A unanimous act of violence against the scapegoat miraculously restores peace and social cohesion (unum pro multis, “one for the sake of many,” as the Roman saying puts it).

[In] Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (1978; the title comes from Matthew 13:35), he argued that the Hebrew Scriptures and the Christian Gospels expose the “scandal” of the violent foundations of archaic religions. By revealing the inherent innocence of the victim —Jesus — as well as the inherent guilt of those who persecute and put him to death, “Christianity truly demystifies religion because it points out the error on which archaic religion is based.”

Girard’s anthropological interpretation of Christianity in Things Hidden is as original as it is unorthodox. It views the Crucifixion as a revelation in the profane sense, namely a bringing to light of the arbitrary nature of the scapegoat mechanism that underlies sacrificial religions.

Girard goes so far as to argue that “Christianity is not only one of the destroyed religions but it is the destroyer of all religions. The death of God is a Christian phenomenon. In its modern sense, atheism is a Christian invention.” The Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo was very drawn to Girard’s understanding of Christianity as a secularizing religion, and the two collaborated on a fine book on the topic, Christianity, Truth, and Weakening Faith: A Dialogue (Columbia University Press, 2010).” ~

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2018/12/20/rene-girard-prophet-envy/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=NYR%20Farmworkers%20in%20fear%20Rene%20Girard%20a%20fathers%20art&utm_content=NYR%20Farmworkers%20in%20fear%20Rene%20Girard%20a%20fathers%20art+CID_ae46916274898ac8a4488f7a37f501da&utm_source=Newsletter

Oriana:

The sacrifice of Iphigenia shows that it putting obedience to an imaginary god first, ahead of obligations to fellow humans, was a mark of archaic mentality in general. The pre-scientific world was filled with invisible beings.

But scapegoating isn’t confined to sacrificial religions. We see it in ideologies as well. Fascism scapegoating Jews is the most flagrant example, but then Jews were being scapegoated in all kinds of crisis situations and by various religions and countries. Whenever a crisis arises, people want to blame someone or a whole ethnic group.

Girard, however, goes beyond pointing out the obvious. To me, the most striking statement is this one:

~ He argued that the Hebrew Scriptures and the Christian Gospels expose the “scandal” of the violent foundations of archaic religions. By revealing the inherent innocence of the victim —Jesus — as well as the inherent guilt of those who persecute and put him to death, “Christianity truly demystifies religion because it points out the error on which archaic religion is based.” ~

*

ROOTS AND WINGS

A sweet and sad memory swam back into my mind . . . I was in my late twenties, sitting on my bumblebee-striped couch in Long Beach with a certain Long Beach poet — not a lover (too many red flags, including drinking), but a kind of shadowy confidant in the category of “harmless” men. It would often get dark as we talked, but we didn’t bother to turn on the light. One time, in a fit of what I now see as a lack of understanding more so than just self-pity (if only I had a fraction of the looks and health I had back then — but how many of us knew what beauty queens we were . . . ), I lamented to this young man that I knew I was different, I knew I was strange, but still, all this trouble I had finding love, being loved. And he very gently replied, “I am surprised that everyone who knows you doesn’t love you.”

Crazy, I know, both my child-like “Nobody loves me” complaint, and his likewise over-the-top reply. But it did me some good at the time. Just my suddenly remembering this seems a minor miracle. The sad part is that the next big news about this man was that he was found dead in a city park. Lethal blood alcohol levels. He was sitting under his favorite tree, drinking bourbon, maybe reading the anthology of his favorite Spanish poets, Roots and Wings. He passed out and never woke up. While he was unconscious, or perhaps already dead, someone stole his wallet, so later the police had trouble identifying his body.

I wrote an elegy for him, Tristan, that I read during a reading to which his mother had been invited as a guest of honor. She was religious and that was one instance in which I could see that religion could indeed provide solace. Afterwards, she sighed with peaceful resignation and said to me, “His kingdom was not of this world.” And in a way, that was the perfect gentle resolution. That was not the time to discuss the high price of refusing to engage with reality, or to try to dissuade her from using a cloud-motif paper on which she wanted his poems printed. At least I had that much wisdom, even though I was shaken by the death of someone slightly younger than I was — the second time in a row. The other man (who died of cancer) was also the gentle kind, and I also treated him as a “harmless” confidant. My definition of a harmless man was the kind I wasn’t attracted to, so he had no power over me. I could relax and be myself. And if he read a poem to me, yes, that was special too.

I felt so safe with a harmless man that I could tell him anything. It reminds me of the father of William Butler Yeats, a sweet and quiet kind. He wrote to his sweetheart, “I tell you more things than I could tell to myself.” That’s because we judge ourselves. The perfect confidant doesn’t judge us. He enjoys just being with us.

Only now I see the strange sad magic of it all. And the only god I can imagine that I’d enjoy being with would be that kind of gentle, harmless man who’d be the ideal, all-accepting confidant — one with an anthology of Spanish poets, who’d now and then would say, “Let me read something to you.”

*

PS. It has occurred to me that in my youth I learned more about love from these “harmless men” than from my actual lovers, who, with one exception, were simply not good human beings.

*

*

“Poutocrats — The poor little billionaires pouting that the tiniest fraction of their wealth goes to public welfare.” ~ Jeremy Sherman

Let’s detox with the frozen waterfall outside Pagosa Springs, Colorado; Mark Heideman

*

RUSSIAN-STYLE KLEPTOCRACY IS SPREADING

~ “For two years, in the early 1990s, Richard Palmer served as the CIA station chief in the United States’ Moscow embassy. The events unfolding around him—the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the rise of Russia—were so chaotic, so traumatic and exhilarating, that they mostly eluded clearheaded analysis. But from all the intelligence that washed over his desk, Palmer acquired a crystalline understanding of the deeper narrative of those times.

Much of the rest of the world wanted to shout for joy about the trajectory of history, and how it pointed in the direction of free markets and liberal democracy. Palmer’s account of events in Russia, however, was pure bummer. In the fall of 1999, he testified before a congressional committee to disabuse members of Congress of their optimism and to warn them of what was to come.

American officialdom, Palmer believed, had badly misjudged Russia. Washington had placed its faith in the new regime’s elites; it took them at their word when they professed their commitment to democratic capitalism. But Palmer had seen up close how the world’s growing interconnectedness—and global finance in particular—could be deployed for ill. During the Cold War, the KGB had developed an expert understanding of the banking byways of the West, and spymasters had become adept at dispensing cash to agents abroad. That proficiency facilitated the amassing of new fortunes. In the dying days of the U.S.S.R., Palmer had watched as his old adversaries in Soviet intelligence shoveled billions from the state treasury into private accounts across Europe and the U.S. It was one of history’s greatest heists.

Washington told itself a comforting story that minimized the importance of this outbreak of kleptomania: These were criminal outliers and rogue profiteers rushing to exploit the weakness of the new state. This narrative infuriated Palmer. He wanted to shake Congress into recognizing that the thieves were the very elites who presided over every corner of the system. “For the U.S. to be like Russia is today,” he explained to the House committee, “it would be necessary to have massive corruption by the majority of the members at Congress as well as by the Departments of Justice and Treasury, and agents of the FBI, CIA, DIA, IRS, Marshal Service, Border Patrol; state and local police officers; the Federal Reserve Bank; Supreme Court justices …” In his testimony, Palmer even mentioned Russia’s newly installed and little-known prime minister (whom he mistakenly referred to as Boris Putin), accusing him of “helping to loot Russia.”

The United States, Palmer made clear, had allowed itself to become an accomplice in this plunder. His assessment was unsparing. The West could have turned away this stolen cash; it could have stanched the outflow to shell companies and tax havens. Instead, Western banks waved Russian loot into their vaults. Palmer’s anger was intended to provoke a bout of introspection—and to fuel anxiety about the risk that rising kleptocracy posed to the West itself. After all, the Russians would have a strong interest in protecting their relocated assets. They would want to shield this wealth from moralizing American politicians who might clamor to seize it. Eighteen years before Special Counsel Robert Mueller began his investigation into foreign interference in a U.S. election, Palmer warned Congress about Russian “political donations to U.S. politicians and political parties to obtain influence.” What was at stake could well be systemic contagion: Russian values might infect and then weaken the moral defense systems of American politics and business.

America could not afford to delude itself into assuming that it would serve as the virtuous model, much less emerge as an untainted bystander. Yet when Yegor Gaidar, a reformist Russian prime minister in the earliest postcommunist days, asked the United States for help hunting down the billions that the KGB had carted away, the White House refused. “Capital flight is capital flight” was how one former CIA official summed up the American rationale for idly standing by. But this was capital flight on an unprecedented scale, and mere prologue to an era of rampant theft. When the Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman studied the problem in 2015, he found that 52 percent of Russia’s wealth resided outside the country.

The collapse of communism in the other post-Soviet states, along with China’s turn toward capitalism, only added to the kleptocratic fortunes that were hustled abroad for secret safekeeping. Officials around the world have always looted their countries’ coffers and accumulated bribes. But the globalization of banking made the export of their ill-gotten money far more convenient than it had been—which, of course, inspired more theft. By one estimate, more than $1 trillion now exits the world’s developing countries each year in the forms of laundered money and evaded taxes.

As in the Russian case, much of this plundered wealth finds its way to the United States. New York, Los Angeles, and Miami have joined London as the world’s most desired destinations for laundered money. This boom has enriched the American elites who have enabled it—and it has degraded the nation’s political and social mores in the process. While everyone else was heralding an emergent globalist world that would take on the best values of America, Palmer had glimpsed the dire risk of the opposite: that the values of the kleptocrats would become America’s own. This grim vision is now nearing fruition.

The warm welcome has created a strange dissonance in American policy. Take the case of the aluminum magnate Oleg Deripaska, a character who has made recurring cameos in the investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. The State Department, concerned about Deripaska’s connections to Russian organized crime (which he has denied), has restricted his travel to the United States for years. Such fears have not stood in the way of his acquiring a $42.5 million mansion on Manhattan’s Upper East Side and another estate near Washington’s Embassy Row.

The defining document of our era is the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in 2010. The ruling didn’t just legalize anonymous expenditures on political campaigns. It redefined our very idea of what constitutes corruption, limiting it to its most blatant forms: the bribe and the explicit quid pro quo. Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion crystallized an ever more prevalent ethos of indifference—the collective shrug in response to tax avoidance by the rich and by large corporations, the yawn that now greets the millions in dark money spent by invisible billionaires to influence elections.

American collusion with kleptocracy comes at a terrible cost for the rest of the world. All of the stolen money, all of those evaded tax dollars sunk into Central Park penthouses and Nevada shell companies, might otherwise fund health care and infrastructure. (A report from the anti-poverty group One has argued that 3.6 million deaths each year can be attributed to this sort of resource siphoning.) Thievery tramples the possibilities of workable markets and credible democracy. It fuels suspicions that the whole idea of liberal [i.e. unregulated] capitalism is a hypocritical sham: While the world is plundered, self-righteous Americans get rich off their complicity with the crooks.

The Founders were concerned that venality would become standard procedure, and it has. Long before suspicion mounted about the loyalties of Donald Trump, large swaths of the American elite—lawyers, lobbyists, real-estate brokers, politicians in state capitals who enabled the creation of shell companies—had already proved themselves to be reliable servants of a rapacious global plutocracy. Richard Palmer was right: The looting elites of the former Soviet Union were far from rogue profiteers. They augured a kleptocratic habit that would soon become widespread. One bitter truth about the Russia scandal is that by the time Vladimir Putin attempted to influence the shape of our country, it was already bending in the direction of his.” ~

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/03/how-kleptocracy-came-to-america/580471/

*

“I have come to believe that the whole world is an enigma, a harmless enigma that is made terrible by our own mad attempt to interpret it as though it had an underlying truth.” ~ Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

That’s like the “meaning of life” — we need to find/create a personal one for our particular life, and not insist that there is THE meaning of life valid for everyone, though of the various answers offered, I like the one that the meaning of life is life itself — just being alive (I think Alan Watts said it). I could go along with that — but then I’d still need my own vocation.

*

*

FORGET FASCISM: WE ARE WITNESSING THE RISE OF CAESARISM

~ “In contrast to a monarchy, in a Caesarist regime the institutions of the republic remain intact and all the magistrates retain their old titles. Julius Caesar rejected the trappings of monarchy that his followers wished to heap on him. Nor was “Caesar” his title; that was simply his family name. It’s his adopted son, Augustus, who is considered the first caesar of the Roman Empire.

The regime of the Roman Republic was completely different from a modern democracy. Nevertheless, comparisons between such governments and Rome have been put forward persistently over the years. The sociologist Max Weber argued that mass democracy necessarily leans toward Caesarism, in terms of the existence of a direct connection between a charismatic leader and the people, which undermines the power of parliament.

Modern Caesarism is not entirely distinct from democracy, but springs up within it. A moderate form of Caesarism is discernible in some of the outstanding leaders of modern democracy, such as Abraham Lincoln and Charles de Gaulle. But in its extreme form, Caesarism deteriorates into sheer autocracy, as with Napoleon Bonaparte or his nephew, Napoleon III. The Caesarist ruler becomes an emperor, and the republic an empire. And if all goes well, a new, quasi-royal dynasty is engendered. A “dictator anointed with oil of democracy,” as the historian Theodor Mommsen put it.

It’s been claimed, in recent months, that Caesarism has returned to politics. Donald Trump’s supporters from the alt-right see him as the “American Caesar” they longed for. His election is portrayed as the fulfillment of the prediction made by their prophet, the German historian and philosopher Oswald Spengler, who foresaw a century ago that Western democracy would evolve into Caesarism in the 2000s. In any event, even outside far-right circles, there are those who argue that Caesarism is a more accurate description of the essence of the dominant model of rule of the Trump era than the badly worn term “fascism.” According to this view, the American republic began to crack during the terms of the two past presidents, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, who, unable to reach agreement with Congress, resorted to presidential decrees in order to govern. But even before he takes the oath of office, Trump is already showing signs of far more radical Caesarism. His direct appeal to the masses via Twitter and YouTube is only a preliminary expression of this.

Trump is not alone. Political commentators in the United States have noted several other countries in which Caesarism has arisen: Putin’s Russia, Erdogan’s Turkey, Modi’s India and Duterte’s Philippines. It’s interesting, in this context, to consider Benjamin Netanyahu’s Israel as a republic skewed by Caesarism. Netanyahu, too, enjoys popular support that only grows stronger the more he clashes with the republic’s traditional institutions: the courts, the media and the cultural elite. He too concentrates in his hands a large portion of the executive roles, and in particular dominates propaganda mechanisms such as the free newspaper Israel Hayom and the Israel Broadcasting Authority. And in his case as well, many forces in society prefer that he hold the reins of power, for fear that without him things would only be worse.

In this connection, particular significance attaches to the rising power of the prime minister’s son, Yair Netanyahu. Already after the last election, in March 2015, Netanyahu began to introduce Yair to the public – for example, when he was positioned behind his father at the Western Wall after the election victory. “Phase II of Sara and Bibi’s plan was launched this week, namely the measured presentation to the public of the intended heir,” Yossi Verter wrote in Haaretz at the time. In recent months, the plan seems to be moving ahead. As reported in Haaretz earlier this month, Yair is deeply involved in the propaganda apparatus of his father’s bureau, particularly with regard to messages in the social networks. Unlike Omri Sharon before him, the young Netanyahu does not draw his power from the Likud Central Committee; the source of his power is his parents.

At a certain stage, the dynasty demonstrates its strength through rulers who are actually idiots, sadists or suffering from insanity. They manifest their power through grotesque behavior and brutal actions. The fact that they continue to rule despite their unfitness proves that the decisive factor is not ability but blood. Thus, two generations after Julius Caesar, the Roman Empire was led by the depressive Tiberius, who closeted himself on the island of Capri, where he pursued his addiction to sexual depravity. He was followed by his insane brother, Caligula, who established a brothel in the palace and dressed and actually fought as a gladiator. Yet, throughout a large part of his reign, Caligula enjoyed great popularity among the Roman masses. They loved dancers, and Caligula knew how to dance – and also how to humiliate the upper classes.

At one point in Robert Graves’ novel “I, Claudius,” the eponymous protagonist extracts a fateful confession from his grandmother, Livia, Augustus’ uninhibited wife. She tells him that she killed Augustus, doing so by means of poisoned figs. The reason, she says, is that her husband intended to restore the republic. “And it’s no use arguing with you republicans,” she tells him. “You refuse to see that one [cannot] reintroduce republican government at this stage.”

It’s noteworthy that Augustus’ poisoning by Livia, “the woman who pulls the strings,” seems not to be based on solid historical evidence. Graves wronged Livia, but also made her the central character in his book.” ~

https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-forget-fascism-in-the-u-s-and-israel-caesarism-is-on-the rise-1.5474399?fbclid=IwAR2ATqsZ2euOP8_qwB8HtiCteJcdZj_yEQ73UVLYvONHrp0cezmn

hnA3_9c

“I

have known in various countries a good many politicians who have

attained high office. I have continued to be puzzled by what seemed to

me the mediocrity of their minds.” ~ Somerset Maugham, The Summing Up

It seems that already Plato commented that only mediocre minds are

attracted to politics. True, there have been exceptions: an occasional

Jefferson or Lincoln, but on the whole, alas . . .

I can't resist reposting my favorite image of Somerset Maugham, 1941

*

DOES CHRISTIANITY HAVE A FUTURE?

“I do think the Church, as I have known it, is dying. But I also see a new Church being born. I prefer to call that new entity, not the Church but the "Ekklesia," which is a transliterated Greek word that means "Those who are called out." I see the membership of the Church of tomorrow to be those who have been called out of tribal identity, out of prejudice, out of gender definitions of superiority and inferiority and even out of religion. That Ekklesia will also be constituted by people who have been called into a new humanity, beyond the primitive boundaries that now bind the Church inside its prevailing cultural prejudices. I expect this new Church to grow as the old Church dies. I have no further desire to seek to stop the death of yesterday's Church. It fulfilled its purpose quite well, but now its day has passed. A new day is dawning, ushering in a new Christian future. I welcome it.” ~ Bishop John Shelby Spong

Oriana:

Ekklesia indeed means being called out, while “church” comes from Kyrios, the Lord — the place of the Lord, and by extension the people who attend that place. For the ex-Catholics here, you are probably also reminded of Kyrie Eleison, a prayer that is (or was, “in my days”) part of the mass.

I love what Spong is saying, but whether Christianity in any form has a future is yet to be seen.

*

THE SURPRISING BENEFITS OF THE MEASLES VACCINE

~ “Back in the 1960s, the U.S. started vaccinating kids for measles. As expected, children stopped getting measles.

But something else happened.

Childhood deaths from all infectious diseases plummeted. Even deaths from diseases like pneumonia and diarrhea were cut by half.

Scientists saw the same phenomenon when the vaccine came to England and parts of Europe. And they see it today when developing countries introduce the vaccine.

"In some developing countries, where infectious diseases are very high, the reduction in mortality has been up to 80 percent," says Michael Mina, a postdoc in biology at Princeton University and a medical student at Emory University.

"So it's really been a mystery — why do children stop dying at such high rates from all these different infections following introduction of the measles vaccine," he says.

The team obtained epidemiological data from the U.S., Denmark, Wales and England dating back to the 1940s. Using computer models, they found that the number of measles cases in these countries predicted the number of deaths from other infections two to three years later.

"We found measles predisposes children to all other infectious diseases for up to a few years," Mina says.

And the virus seems to do it in a sneaky way.

Like many viruses, measles is known to suppress the immune system for a few weeks after an infection. But previous studies in monkeys have suggested that measles takes this suppression to a whole new level: It erases immune protection to other diseases, Mina says.

So what does that mean? Well, say you get the chicken pox when you're 4 years old. Your immune system figures out how to fight it. So you don't get it again. But if you get measles when you're 5 years old, it could wipe out the memory of how to beat back the chicken pox. It's like the immune system has amnesia, Mina says.

"The immune system kind of comes back. The only problem is that it has forgotten what it once knew," he says.

So after an infection, a child's immune system has to almost start over, rebuilding its immune protection against diseases it has already seen before.

This idea of "immune amnesia" is still just a hypothesis and needs more testing, says epidemiologist William Moss, who has studied the measles vaccine for more than a decade at Johns Hopkins University.

But the new study, he says, provides "compelling evidence" that measles affects the immune system for two to three years. That's much longer than previously thought.

"Hence the reduction in overall child mortality that follows measles vaccination is much greater than previously believed," says Moss, who wasn't involved in the study.

That finding should give parents more motivation to vaccinate their kids, he says. "I think this paper will provide additional evidence — if it's needed — of the public health benefits of measles vaccine," Moss says. "That's an important message in the U.S. right now and in countries continuing to see measles outbreaks."

Because if the world can eliminate measles, it will help protect kids from many other infections, too.

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2015/05/07/404963436/scientists-crack-a-50-year-old-mystery-about-the-measles-vaccine?fbclid=IwAR2DidhqAQylYr8CSpJ128nnJqgfKHhbOsHub-6MZ4qiGvSlNqdb2akaR14

Maurice Hilleman's measles vaccine is estimated to prevent 1 million deaths per year.

Maurice Hilleman's measles vaccine is estimated to prevent 1 million deaths per year.

ending on beauty:

Everywhere is home to the rain.

~ Li-Young Lee, Hurry Toward Beginning.

California hasn’t been home to the rain for a while, but this year is different. May the reservoirs fill up.

California hasn’t been home to the rain for a while, but this year is different. May the reservoirs fill up.

“Death blowing bubbles,” 18th century. The bubbles symbolize life's fragility. This plaster work appears on the ceiling of Holy Grave Chapel in Michaelsberg Abbey, Bamberg, Germany. After the monastery’s dissolution in 1803, the buildings were used as the city's hospital.

“Death blowing bubbles,” 18th century. The bubbles symbolize life's fragility. This plaster work appears on the ceiling of Holy Grave Chapel in Michaelsberg Abbey, Bamberg, Germany. After the monastery’s dissolution in 1803, the buildings were used as the city's hospital.

*

A BOOK OF MUSIC

Coming at the end, the lovers

Are exhausted like two swimmers. Where

Did it end? There is no telling. No love is

Like an ocean with the dizzy procession of the waves' boundaries

From which two can emerge exhausted, nor long goodbye

Like death.

Coming at the end. Rather I would like to say, like a length

Of coiled rope

Which does not disguise in the final twists of its lengths

Its endings.

But, you will say, we loved

And some parts of us loved

And the rest of us will remain

Two persons. Yes,

Poetry ends like a rope.

~ Jack Spicer

Frida tells them the truth about love

Frida tells them the truth about love

Oriana:

All romantic love ends — it either becomes transformed into a deep attachment, which arguably can be called “true love,” or the lovers part. But if they part, ideally they should remember that there was a time they truly loved each other, and they should honor this memory by refraining from vengefulness or any hostile acts. “We loved each other,” they should say, and hopefully understand how sacred those words are.

Mary:

Of course no better subject for Valentine's week than love. Something essential, it seems, for survival, for a life clear, strong and untwisted, for confidence in one's own worth and right to exist. If infants are not loved, especially if they are not touched, it does seemingly irreparable damage to their ability to feel, even understand, and certainly to experience this one essential. Those whose early times were loveless or traumatic may be ever hungry, ravenous, for love, and in their need and desperation, can overwhelm and devour their chosen, swallowing lives in an endlessly unfilled chasm of need. These are love's vampires. And they are legion.

Rather than that "two become one" idea of love that involves the unending search for that perfect 'other half' that will 'complete you,' I prefer Spicer's

......we loved

And some parts of us loved

And the rest of us will remain

Two persons.

Much better than all those jumbled fragments of bone, like a disarticulated jigsaw puzzle muddled up together in the grave. That image seems the ultimate of the romantic one and only, let us merge together and dissolve in each other kind of thinking, that, sooner or later, becomes a tragedy. For example: Bronte's Cathy and Heathcliff.

And even with all the varieties of dangerous and predatory love, the false and manipulative, the delusional and narcissistic, there is that sense always that love is what we want and need, what we must have, simply to be human.

Oriana:

Yes. Oddly enough, the most dangerous adult is someone who was seriously deprived of love as a child. Or rather, I should correct that to “who was abused as a child.” A friend who worked in in a maximum-security prison told me that they had a scholar interview the inmates: 100% of them were sexually abused as children. 100%!

And the abusers were very likely themselves victims of abuse. The astonishing and hope-giving thing is that some victims decide to break the chain. That’s what we should celebrate: that at least some people manage not to keep on acting out of their wounds, but break through to their essential humanity. And perhaps the most marvelous thing about humans is that no matter what our wounds, most of us don’t lose the capacity for love.

As for remaining two separate people, even some maturity and experience shows us that no, we don’t find the “missing half” or the soulmate. We don’t really “complete each other.” Those are destructive myths that have done harm. We have the grant our partner the freedom to be his own person — just as a cat has to do cat things and a dog has to sniff around. If we can respect the animal’s true nature (sadly, I’ve encountered people who just can’t let go of control, with people or animals), how much more this applies to humans.

Yes, we are separate and unique, and “two people who love each other is a miracle” ~ Adrienne Rich. But we need to shed harmful myths — “soulmate” is an example, especially if anyone believes that there is only one true soulmate out there in the world, and we must find that missing person. No, love is a process — a complex process which includes a lot of learning and growing up. And perhaps the greatest gift we can give to a lover, aside from affectionate nurturing, is being mature enough to give that person the space and freedom to be who they are. If we try to mold the partner to be closer to what we’d like them to be, then we are getting dangerously close to the kind of “delusional and narcissistic” love that Mary mentions. Healthy love is based on deep respect for the partner’s unique being — and wanting what is best for them.

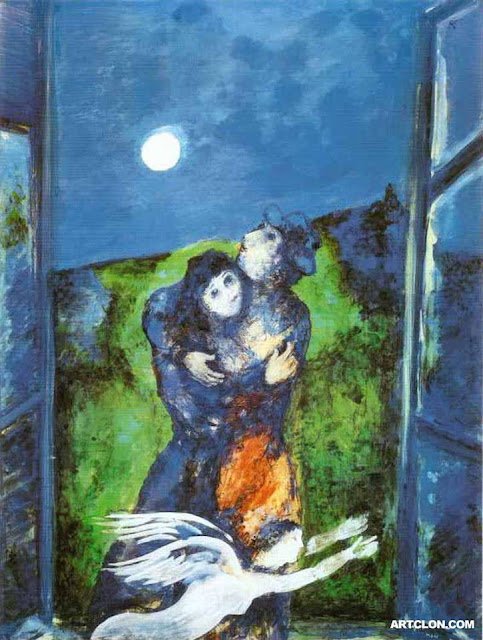

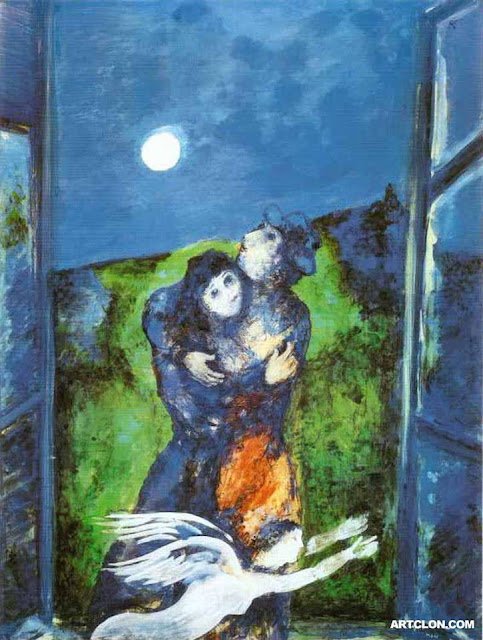

Though I don't know if Chagall intended the winged figure to mean fleeing Eros, that's how I think of this painting.

Though I don't know if Chagall intended the winged figure to mean fleeing Eros, that's how I think of this painting.

“THE FAVOURITE”: FAKE LOVE VERSUS REAL LOVE

There is a Russian saying about the difference between fake and true love. Upon seeing you bareheaded during snowfall, the person who only pretends to love you says, “You look beautiful with snowflakes in your hair.” The true lover says, “Where is your cap, stupid?”

The saying strikes me as quite perceptive. I don’t know if “stupid” is a requirement here, and that’s where Queen Anne’s original “favourite,” Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough, perhaps overplays her hand. To prove that the affection of her rival, Abigail, is fake, Sarah says, “Sure, she tells you, ‘You are so beautiful. You look like an angel. I tell you that sometimes you look like a badger.”

This, again, is an accurate observation, but the sickly queen, who is certainly no beauty, doesn’t need to hear that she looks like a badger. A genuine lover should be able to tell the truth, even if it may displease the partner, but . . . there are limits. Sarah will not play with the queen’s rabbits and says, “Love has its limits.” But so does honesty. There is no need for cruel comparisons.

Queen Anne. Note the pendant of St. George and the Dragon.

Queen Anne. Note the pendant of St. George and the Dragon.

The queen needs to feel cherished, even if it means falling for Abigail’s flattery. She knows she isn’t beautiful, but . . . what woman doesn’t like being told she’s beautiful? Or being paid compliments in general? Both men and women seem to thrive on certain amount of flattery, but since this movie concentrates so much on women, let’s leave male-female comparisons out of the discussion. It could be said that the movie is about love in general: to what extent should we perhaps think more about kindness than about truthfulness in long-term relationship?

The Favourite does not claim to be historically accurate, as critics have pointed out. To this day we aren’t sure if Queen Anne had any lesbian relationships. She did seem to rely on the advice of female friends more so than male advisers — though in the end she made up her own mind, according to historians. The current view of her is not that of weak, timid, ignorant monarch with no views of her own, who did not rule so much as did the bidding of the Duchess of Marlborough and the favorites who succeeded her; rather, Queen Anne presided ably enough over England’s rise from a minor power to a major power, and the country unification as Great Britain.

She was also a patron of the arts, especially music (think Handel), but that’s a separate issue. The movie doesn’t concern itself with the complexities of the historical Queen Anne. It’s a movie about the nature of love.

The tragedy here is that fake love wins: Abigail triumphs while Sarah falls into disfavor — to the point of being dismissed from the court and seeing that it would be better for her and her husband, the Duke of Marlborough, to leave England. First, she has to surrender the huge gold key that is symbol of her power: the ceremonial Key to the Royal Bedchamber.

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

Reading the history of the court intrigues of those years is dizzying. The rivalry between Sarah and Abigail was real, as was the rise of Abigail from a domestic servant to an influential courtier. The pet names of Mrs. Morley (Anne) and Mrs. Freeman (Sarah) were real too, attesting to the existence of a private language and real affection between the two women. Abigail’s alleged attempt to poison Sarah seems fictional. Sarah’s domineering nature and her wicked tongue caused quarrels, and that seems to have been the chief cause of her downfall.

Still, it was a genuine long-term relationship — Sarah was in fact Anne’s childhood friend, and the two appear to know each other very well. Nevertheless, Sarah seems to have been insensitive to the queen’s emotional needs. Love does indeed have limits, but it’s not love without kindness and deep respect. Sarah’s quest for power ultimately takes precedence, and she loses the queen’s heart.

Both Sarah and Abigail are ruthless manipulators, but Abigail, perhaps because she is a survivor of all kinds of abuse, turns out to be a greater expert. She understands the queen’s desperate need to be loved, and caters to it. She is dripping with flattery and sweetness. The queen eats up the sweetness — even in the symbolic form of gorging herself on cake.

The scene that reveals how mean Abigail truly is is the one in which she torments a little rabbit — one of the queen’s “children.” The queen is asleep, but the rabbit’s squeal under Abigail’s shoe wakes her up and she witnesses her new favorite’s cruelty. “This really showed Abigail’s hatred of the queen,” my friend remarked. Yes. In the movie, Abigail ends up paying a high price for this. But the queen wakes up too late, so to speak. She has already lost the woman who truly cared for her, and with whom she’d built a long-term relationship.

The scene with the rabbit is the turning point: not only for the queen, but also for the audience. At first we may sympathize with Abigail and are willing to see her as a victim first, a schemer second. But now we see she is evil — or rather, she is an extremely damaged human being. She is incapable of true affection — not even for a tiny rabbit.

One of the lessons of my youth was: if you meet someone who’s had a truly horrible childhood, run for your life. Such people, I discovered, can be cruel and dangerous. They can perhaps be rehabilitated by a gifted therapist, but the average person better stay away. It’s much too easy to fall for the sugary sweetness of fake love.

Abigail Masham

Abigail Masham

I realize that some viewers may insist that all we have here is fake love: neither Sarah nor Abigail can be said to love the queen. Each pursues her own agenda, and merely uses the queen for her own purposes. But I defend my thesis: while Sarah offered too little tenderness or even simple kindness, she did have a genuine long-term relationship with Anne, a deep intimacy they had built over the decades. The way the queen yearns for a letter from her is quite telling, as is Sarah’s ultimate choice of “My dearest Mrs Morley” as the heading of the conciliatory letter that Abigail intercepts. Abigail is excellent at pretending love, but she loves no one.

Also telling is the way Sarah and Anne can laugh together. True, they quarrel, but they also know how to enjoy being together. With Anne, Abigail is always performing, always trying to be sweet — which must be a strain. Even before the rabbit-torture scene, Abigail shows her true personality when she gets drunk (we don’t get to see chamber pots in this movie, but we do see the vomit vases).

By the way, the movie is visually splendid. It’s not only the costumes and the decor; it’s also the gorgeous horses, always either black or white. And a duck race. And all those outrageous wigs.

I should also mention the powerful acting. This is Emma Stone’s best performance ever.

*

The holiest of holidays are those kept by ourselves in silence and apart; the secret anniversaries of the heart. ~ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

This looks so Dickensian, but it's a snowy night in Moscow. This is what all Europeans seem to understand, but not all Americans: one can fall in love with a city. Below: a sunset in Trieste.

This looks so Dickensian, but it's a snowy night in Moscow. This is what all Europeans seem to understand, but not all Americans: one can fall in love with a city. Below: a sunset in Trieste.

*

“What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare?” ~ Captain Ahab, toward (so to speak) the whale, Ahab’s only Valentine

*

“What reconciles me to my own death more than anything else is the image of a place: a place where your bones and mine are buried, thrown, uncovered, together. They are strewn there pell-mell. One of your ribs leans against my skull. A metacarpal of my left hand lies inside your pelvis. (Against my broken ribs your breast like a flower.) The hundred bones of our feet are scattered like gravel. It is strange that this image of our proximity, concerning as it does mere phosphate of calcium, should bestow a sense of peace. Yet it does. With you I can imagine a place where to be phosphate of calcium is enough.” ~ John Berger

Oriana:

“Against my broken ribs your breast like a flower” — that sounds so good, but there would be no breast left, only the bones. This is a prose poem about bones, and in principle it should stick to the bones. But every poet knows this problem: you find a great-sounding line that doesn’t quite fit, that is really its own separate poem — but you’re too in love with it to let it go, to “murder your darling.” And you hope that the readers will forgive you, and also fall in love with that line.

As for the rest of this peculiar valentine, it seems to hint that with men, sex drive truly never ends, not even in the grave. But one could object that Berger makes it sound “only physical.”

John Berger

John Berger

*

KINDNESS: ANOTHER MODERN VALUE

I'm pondering Kent Clark’s statement: "Today, if we asked people what quality is most important, the majority would say “kindness.” Yet Dante or St. Francis would not say that. St. Francis would have probably replied, “Chastity, obedience, and poverty.” Chastity more important than kindness? Apparently so.

Others in earlier centuries might have named courage, virtue, piety. Or endurance and self-control (Stoicism). John Milton would probably put obedience first. Depending on social class, other possible supreme values might be hard work and thrift. It was not until the 19th century that revulsion against cruelty (including slavery) began emerging. The novels of Dickens had an immense social influence — perhaps the most proud chapter in the history of literature, a showcase of how a novel can expand empathy.

A while ago I was astonished by an article insisting that Christianity is not about kindness. All those years I thought that Christianity WAS about kindness. In fact the teachings on kindness were Christianity’s saving grace, outweighing the barbarous human sacrifice, the “bloody ransom” that stood as the foundation. But it was possible to put the gory salvationism out of one’s mind and just follow the teachings on kindness. Forgiveness, compassion, non-revenge, helping the less fortunate — that, I thought, was the beauty of Christianity.

How misguided and un-Christian, the article argues. This sentence says it all: “To make kindness into an ultimate virtue is to insist that our most important moral obligations are those we owe are to our fellow human beings” (and to animals, I would add, who are also our brothers and sisters).

Our most important moral obligations AREN’T to our fellow human beings??

Well, no. To use my own lingo now, according to religious conservatives, your highest moral obligation is not to real beings, but to an imaginary being.

And it’s tricky to define our moral obligations to that imaginary being. Are we to wage crusades? If not going to mass on Sunday is a mortal sin, is it a greater obligation than taking the time to play with your children? Obviously everything depends on interpretation, meaning which century you happen live in, and which church you belong to.

I also remembered that for a long time numerous thinkers have argued that the divinity of Jesus was open to question, and he should rather be honored as a teacher of ethics. After all, that was the premise of Unitarianism.

Perhaps not surprisingly, though somehow I was surprised, what followed in that article trying to define Christianity was a sermon on sin and fearing god and obeying the commandments. As for kindness, the author reminds us that “Jesus did not heal everyone who asked to be healed.” Sometimes, apparently suffering from kindness fatigue, Jesus would go off by himself to rest and pray. (True. Christianity doesn’t insist on excessive, pathological altruism that would destroy our health. Only “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” Not more so.)

But somehow the commandment of love is never mentioned in the article — though I admit that the command to love god caused me much grief since I could not feel the slightest affection for the mean old man in the sky who threw children into hell by the million (all the non-Catholic children, back then). But I loved St. Paul’s “though as speak with the tongues of men and angels . . .” If only it had occurred to me back then (as it did much later) that a nun threatening children with hell is like the clashing of cymbals.

But at the time, it didn’t yet occur to anyone that threats of hell were a form of child abuse. A mild form, I admit, compared to severe beatings, and worse, that used to be normal child rearing practices in past centuries. The levels of stress had to go down for cruelty to lessen too. Dickens and Victor Hugo had to write his novels about the sufferings of children and the poor, so that “kindness” could take root in the collective psyche.

The early deities were cruel. Times were harsh, and this was reflected in the various religions. The preaching of loving kindness by the Buddha and Jesus was indeed revolutionary. But for kindness to become more of a reality, life had to become less harsh — and that is fairly recent. The levels of violence had to go down, as has indeed happened in a significant portion of the world. When we feel secure and when our physical needs are taken care of due to greater prosperity, we then have the luxury (in contrast with the past centuries) of practicing kindness. We can even speak out against spanking and other cruelty against children. We grow intolerant (and justly so) of even petty violence and malice. We start imagining a world at peace, a world where everyone is kind.

Pessimists might reply that that is an unachievable ideal. Cynics might laugh — but not as loud as they would have during the Middle Ages. Against many odds, progress has been made. One indicator of it is indeed the high value we place on kindness. The gap between the ideal and the practice is undeniably there, but I argue that the very visibility of the ideal is already a fact to be celebrated.

As for the concept of hell, I'm told that in liberal Protestantism hell is not even mentioned anymore. Mark my words: eventually hell will go. Theists still believe in angels, but the percentage believing in the devils is decreasing. It is a trend, one that reflects the great value that we moderns have learned to place on kindness.

Mary:

If kindness and empathy have become more possible as we have become more able to afford them . . . perhaps becoming more valued, even required of each other, as we move farther away from having to spend all energies in the struggle to survive . . . what bright hopes arise! For all the violence and injustice we see, it is yet a world away from what was commonplace and unremarkable even 100 years ago. Values, norms, expectations, have shifted, and even the resurgence in open hate speech evident in the US today appears like something pulled up from history's old root cellar, coarse and grotesque — most importantly — not invisible — not just part of the scenery — no longer accepted as the usual and even necessary order of things.

Oriana:

“For all the violence and injustice we see, it is yet a world away from what was commonplace and unremarkable even 100 years ago.” Yes! There is less acceptance of cruelty and overt racism and bigotry of any kind. It may seem irrelevant to bring up the success of the anti-smoking campaign here, but I don’t think it is. When a vigorous effort is made to raise awareness that something is harmful, most people eventually “get it.”

I think even without a coordinated effort, the very fact that we are exposed to “the other” on mass media is tremendously significant. A close-up of a human face, regardless of the person’s color, still shows a face that we recognize as similar to our own — the soulful eyes with fear and hope in them, the soft lips made for kissing. If we love animals the way we do — but note, cruelty toward animals also used to be commonplace — if we recognize ourselves in animals too, recognize their capacity of affectionate attachment — how much more so our own kind.

I must have said it a hundred times by now — progress in medicine and technology has made life less harsh, and child rearing has become less harsh as well. No doubt there have also been other changes that combined to produce this effect, but simply receiving more love in childhood leads to an improvement in the person’s capacity to love — to recognize the humanity of others.

St. Francis in ecstasy; Giovanni Bellini, 1480. Note the wonderful landscape and the animals — and the city in the background, with a castle on the hill.

St. Francis in ecstasy; Giovanni Bellini, 1480. Note the wonderful landscape and the animals — and the city in the background, with a castle on the hill.

*

REASON AND PROGRESS: THE CRYSTAL PALACE

“You believe in a crystal palace that can never be destroyed—a palace at which one will not be able to put out one's tongue or make a long nose on the sly. And perhaps that is just why I am afraid of this edifice, that it is of crystal and can never be destroyed and that one cannot put one's tongue out at it even on the sly.” ~ Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground

from Wiki: ~ The Crystal Palace was a cast-iron and glass building originally erected in Hyde Park to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. Following the success of the exhibition, the Palace was moved and reconstructed in 1854 in a modified and enlarged form in the grounds of the Penge Place estate at Sydenham Hill. The buildings housed the Crystal Palace School of Art, Science, and Literature and Crystal Palace School of Engineering. It attracted visitors for over seven decades.

Sydenham Hill is one of the highest locations in London; 109 metres (357 ft) above sea level; and the size of the Palace and prominence of the site made it easy to identify from much of London. This led to the residential area around the building becoming known as Crystal Palace instead of Sydenham Hill. The Palace was destroyed by fire on 30 November 1936 and the site of the building and its grounds is now known as Crystal Palace Park. ~

For Dostoyevski, the Crystal Palace was a symbol of blind belief in progress and the triumph of the values of the Enlightenment. D was a great psychologist who understood the power of the irrational. Reason too is a slave of passions, many writers and some philosophers have concluded. Indeed, emotions are crucial to our decision making, and the intellectually gifted, contrary to the stereotype, tend to be emotionally intense.

Hamlet to Horatio:

Give me that man

That is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him

In my heart’s core, ay, in my heart of heart.

~ Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

PRELIMINARY RESULTS OF FINLAND’S BASIC PERSONAL INCOME TRIAL

~ “Tuomas Muraja’s life took an unexpected turn at the end of 2016. He received a letter telling him that he would be getting a monthly sum of €560 ($640) from the Finnish government, no strings attached, for two years.

“It was actually like winning the lottery,” said Muraja, who was one of 2,000 people randomly selected from a pool of 175,000 unemployed Finns, aged 25 to 58, to take part in one of the most prominent universal basic income trials in the world.

The trial ended in December. While final results won’t be available until 2020, preliminary results were revealed on Friday.

On employment, the country’s income register showed no significant effects for 2017, the first year of the trial.

The real benefits so far have come in terms of health and well being. The 2,000 participants were surveyed, along with a control group of 5,000. Compared with the control group, those taking part had “clearly fewer problems related to health, stress, mood and concentration,” said Minna Ylikännö, senior researcher at Kela. Results also showed people had more trust in their future and their ability to influence it.

“Constant stress and financial stress for the long term – it’s unbearable. And when we give money to people once a month they know what they are going to get,” said Ylikännö. “It was just €560 a month, but it gives you certainty, and certainty about the future is always a fundamental thing about well being.”

“When you feel free you are creative, and when you are creative you are productive, and that helps the whole of society,” said Muraja, who has written a book about his experiences with the trial.

The policy has supporters on both sides of the political spectrum. Those on the left say it will help tackle poverty, reduce yawning inequality and help people fend off the threat of their job being automated. For advocates on the right, UBI is seen as an attractive way to simplify complex systems of welfare payment and reduce the size of government.

Tech billionaires, such as Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk, have thrown support behind the idea amid anger over their own extreme wealth. It’s also caught the attention of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez (D.-N.Y.) who has floated UBI as part of a Green New Deal – the umbrella name for a host of policies to tackle climate change and reduce inequality.

The end of the scheme was a shock, [one recipient] said, for everyone who participated in the trial. “We all are in big trouble now to be honest, because what would happen to you if your income decreased by €600?”

She’s still working at her job, but is already running up debt and desperately searching for better-paying work.

The end of Finland’s scheme was also a blow to those who had hoped the trial would be expanded and extended. Politicians “wasted the opportunity of a lifetime to conduct the kind of trial that Finnish social policy experts had done preliminary research for for decades,” said Antti Jauhiainen, a director of the think tank Parecon Finland.

But there are experiments that are still going. A program in Kenya, for example, run by the charity GiveDirectly, has been giving out unconditional money since 2016 to more than 21,000 people in villages across the country in a trial set to last 12 years. Initial results show a boost to the well being of participants.

And there are others on the horizon. In the U.S., a trial is about to kick off in Stockton, California, that will give $500 a month to 100 low-income families. And in Oakland, the tech incubator Y Combinator intends to start a UBI trial this year that would hand $1,000 a month with no strings attached to 1,000 people across two U.S. states for three years. In India, the main opposition party is running on a pledge to introduce a guaranteed minimum income for the country’s poor.

Finland is readying itself for elections in two months, and some hope that UBI could be back on the table. Kauhanen is among them. “I loved the basic income experience,” she said, “and I wish that it would be for all people in Finland. I know it’s expensive, but on a smaller scale, I think it would be just what we need because right now in Finland, the poor people are the ones who are getting cut off.” ~

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/universal-basic-income-finland-ontario-stockton_us_5c5c3679e4b00187b558e5ab

No surprises here: people’s mental and physical health improves as financial stress decreases. School performance tends to go up, and young people tend to remain in school longer. With less pressure to provide a second income, new mothers tend to choose staying home with their newborns. Money can’t buy happiness? Yes it can — up to a point.

President Nixon, of all people, has proposed a negative income tax: those earning less than a certain amount would receive a monthly payment. But the proposal didn’t pass.

Finland: Osterskar Island

Finland: Osterskar Island

*

“Basic income would give people the most important freedom: the freedom of deciding for themselves what they want to do with their lives.” ~ Rutger Bregman, author of Utopia for Realists

“A map of the world that does not include utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always landing. And when humanity lands there, it looks out and seeing a better country sets sail. Progress is the realization of utopias.” ~ Oscar Wilde

Shangri-La(the movie’s actual title was Lost Horizon, directed by Frank Capra; I loved the movie)

Shangri-La(the movie’s actual title was Lost Horizon, directed by Frank Capra; I loved the movie)

AMERICA IS FINALLY FALLING OUT OF LOVE WITH BILLIONAIRES

~ “Our emerging political debate over taxing the rich seems to be getting bogged down in details — how high a tax rate, should we tax income or wealth, etc., etc. But this fixation on nuts and bolts is obscuring what may be the most important aspect of the discussion: America is becoming fed up with its billionaires.

Since the Reagan administration, the political establishment has strived to convince Americans that extreme wealth in the hands of a small number of plutocrats is good for everyone. We’ve had the “trickle-down” theory, the rechristening of the wealthy as “job creators” and their categorization invariably as “self-made.” We’ve been told, via the simplistic Laffer Curve, that if you raise the tax rate you get less revenue.

There are three main subtexts of these arguments, all of which show up in the email in-box whenever I write about wealth and taxation. First: The extreme wealth of the few creates wealth all along the income scale, for the masses. Second: It’s immoral — confiscatory — to soak the rich via taxation, at least above a certain level that never seems to be precisely defined. And third: If we torment the wealthy with taxes, they’ll pack up their wealth and leave us, whether for some more accommodating nation on Earth or some Ayn Randian paradise.

Experience has shown us that the first argument is simply untrue — extreme wealth begets only more inequality. The second argument raises the question of where reasonable taxation turns into confiscation, although the level of taxation of high incomes today is nowhere near as high as it was in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, when economic gains were shared much more equally with the working class. As for the third, Warren’s answers to capital flight include stepping up IRS enforcement resources, which have been eviscerated by political agents of the wealthy, and imposing an “exit tax” on any plutocrat renouncing his or her U.S. citizenship to evade U.S. taxes.

Why are billionaires beginning to be treated so skeptically?

One reason surely is the evidence that extreme wealth has a corrosive effect on the economy. Wealth inequality places immense resources in the hands of people unable to spend it productively, and keeps it out of the hands of those who would put it to use instantly, whether on staples or creature comforts that should be within the reach of everyone living in the richest country on Earth.

Multimillionaires and billionaires love to describe themselves as “self-made,” but the truth is that every fortune is the product of other people’s labor — the minimum-wage workers overseas who assemble Michael Dell’s computers or the low-wage baristas in Howard Schultz’s Starbuck stores, or the taxpayers who fund the roads, bridges and airports that help keep their businesses profitable.

Examples have been proliferating of the inability of the super-rich to spend their money productively or for the common good. Last week it was reported that Daniel Snyder, the owner of the NFL’s Washington Redskins, was spending $100 million on a 305-foot super-yacht complete with an on-board IMAX screening room. It’s his second yacht, after a 220-foot version.

At the same moment, hedge fund owner Ken Griffin was disclosed as the buyer of the most expensive home in America, a $238-million Manhattan penthouse. According to Bloomberg, he already owns two floors of the Waldorf Astoria hotel in Chicago ($30 million), a Miami Beach penthouse ($60 million), another Chicago penthouse ($58.75 million) and another apartment in Manhattan ($40 million).

Griffin, to be fair, also deploys some of his wealth philanthropically. But that only raises the question of why that sort of spending should go to the recipients personally favored by a billionaire, even with the best intentions.

Computer entrepreneur Dell unwittingly raised exactly this question during a panel discussion at the recent financial powwow in Davos, Switzerland, where he dismissed calls for higher taxes on the super-wealthy by declaring that he contributed to society via a family foundation. “I feel much more comfortable with our ability as a private foundation to allocate those funds,” he said, “than I do giving them to the government.”

The only answer to that is: Sez who? As I observed at the time, Dell’s multibillion-dollar fortune is based on mail and online orders of computers — in other words, on infrastructure created and funded by the government he disdains.

People like (Starbuck’s) Schultz “live what is, for almost all practical purposes, a post-scarcity existence,” Paul Campos observes aptly at the Lawyers, Guns & Money blog. “If you have three billion dollars, then you can buy almost anything without even bothering to consider what it costs, since what it costs is, to you, practically indistinguishable from ‘nothing.’ Given that everything is for you already basically free, why would you even care if your tax bill goes up?

Especially given that you live in a society in which, despite what is by ... historical standards an almost inconceivable amount of total social wealth, lots of people still have to worry about getting enough to eat, not freezing to death in the next polar vortex, etc?”

Keynes today is treated as an icon of liberal economics, but he was a capitalist through and through. His theme here was that the accumulation and investment of capital had created a world in which the economic struggle — the “struggle for subsistence” — would be won within 100 years.

That brought Keynes to a critique of “the money motive.” He looked ahead to a world in which “the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance” and society could rid itself of “many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues.”

Chief among these was “the love of money as a possession — as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life.” The pursuit of excess wealth, he projected, “will be recognized for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease.”