Fifty shades of ocean. I haven’t counted, but have seen.

Fifty shades of ocean. I haven’t counted, but have seen.*

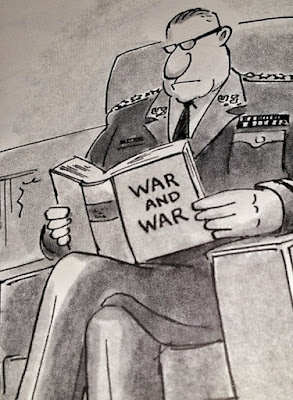

A friend of mine says that every war

Is some violence in childhood coming closer.

Those whoppings in the shed weren’t a joke.

On the whole, it didn’t turn out well.

This has been going on for thousands

Of years! It doesn’t change. Something

Happened to me, and I can’t tell

Anyone, so it will happen to you.

~ Robert Bly

Child abuse is no doubt only one of the many factors contributing to the perpetuation of warfare, but it’s not one that can be easily dismissed. Living one’s childhood in a state of fear, whether of an abusive parent or school bully or both, will lead to greater amount of fear in adulthood — and it’s the stirring up of fear that war mongers rely on.

This is also why I have hope that eventually war will become, if not non-existent, then at least exceedingly rare. Child abuse? That used to be regarded as “normal childrearing” some decades ago. The use of corporal punishment was never questioned. It’s only relatively recently that we’ve come to see every child’s need for affection, for being valued.

*

POETRY AS THE PLOT AGAINST THE GIANT

I shall run before him,

With a curious puffing.

He will bend his ear then.

I shall whisper

Heavenly labials in a world of gutturals.

It will undo him.

~ Wallace Stevens

*

“In jail, poetry was to become something else: a spoon with which to tunnel through the wall.” ~ Bruce Smith

~ “Poetry became the necessary nothing that resisted and also provided—this sounds corny—not an escape but a “plot against the giant” as Stevens said. A way to check, abash, and undo the giant using the feminized means of poetry, whispering “heavenly labials in a world of gutturals.” All this is a way to say that the study and the practice became important to me because of my experience at Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary.

PM: Would you be willing to say more about this line in the poem “Lewisburg”: Poetry is the spill [excess and witness]? I wonder if that line serves as a kind of poetics for you.

BS: Excess, yes, in the way that any poem is superfluous in a market, commodity exchange. Excess is also abundance in the way Seamus Heaney speaks of it, “The work poetry does, the redress it gives, is to keep the reader on the side of abundance and acceptance.” So abundance as a kind of awe and bliss—Whitman in Specimen Days.

But the poem is not just an aesthetic project, but is a witness to the atrocious. Since I’ve spent a good part my life in the 20th century, the book takes on the role as Carolyn Forché and Peter Balakian have pointed out as something between the personal and the political which is a third thing, the social or historical extremity in which we live. Neither reporting nor rhapsody. Eh, this sounds too deliberate, programmatic when it’s a lot of turbulence and mystery and language and angels in the form of barking dogs.”

Dali: The Poetry of America, 1943

Dali: The Poetry of America, 1943https://lithub.com/bruce-smith-on-poetry-in-prison-and-the-poetic-task-of-demystification/?fbclid=IwAR27qqRFOnUIEk0AdRpYvPp_IdU9a2EGDGatiEYBeeb_gGf7LEx_vA6fchU

Oriana:

I love the idea of poetry as the plot against the giant. I first read the poem and the lines quoted here, which happen to be my favorite, when I discovered Stevens in my twenties. Though I instantly liked the poem and remembered it, only this article acutely brought out the meaning. And also only now we see the evil giant with such clarity.

I also like the idea of poetry as a form of wealth, the opposite of verbal poverty (not to be confused with simplicity; simplicity is part of elegance). Art as luxury, beauty as luxury — could there be something more opposite to the deliberate ugliness of a prison cell? Ugliness brutalizes the spirit; beauty nourishes it.

(And that makes me think of fine food — presumably the opposite of what is served in the prison canteen. By now more than one prison has a program to train inmates to be chefs. Not short-order cooks at McDonald’s, mind you. No — someone with training in fine cuisine. To be the best — now THAT is inspiring.)

*

Of course all literature can be subversive. It takes us outside ourselves, makes us see the world in a different way.

Mad Hatter: “Why is a raven like a writing-desk?”

“Have you guessed the riddle yet?” the Hatter said, turning to Alice again.

“No, I give it up,” Alice replied: “What’s the answer?”

“I haven’t the slightest idea,” said the Hatter.

~ Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Dali: A Mad Tea Party

Dali: A Mad Tea Party*

WHITE CROW: “WHAT STORY ARE YOU TRYING TO TELL?”

First, while only Nureyev could be Nureyev, the Ukrainian dancer Oleg Ivenko does some splendid dancing in this movie. I only wish the movie showed us more of this dancing and fewer of his sullen, silent moments, which get to feel repetitious. We get it early on: Rudi has a difficult personality, bad manners (if we are to trust the movie, he never even bothers to call and thank Clara, his long-suffering friend who played a critical role in helping him defect), and inexplicable temper tantrums for which he never apologizes. As a human being, he seems the opposite of his wise and gentle teacher, Alexander Ivanovich Pushkin (played by Ralph Fiennes, who astonishes us with his fluent Russian).

It’s Pushkin who says to the almost crazily driven Rudi: “Technique is not enough. You have to decide what story you are trying to tell.” I suspect that those who weren’t satisfied with the movie (it’s not a masterpiece, but I think it can be recommended) weren’t sure what story it was trying to tell. Rudi’s hard struggle to establish himself? The extent of KGB’s surveillance of the Soviet artists and the overall stifling effect of politics on art? All the factors, beginning in childhood, that led to Rudi’s defection? More clarity about the dominant story would have probably led to better editing — and perhaps given us more dancing instead of the excess close-ups of that sullen silence.

Perhaps because of my interest in psychology, I found myself interested chiefly in Rudi’s seemingly inexplicable temper tantrums. True, great achievers are known to be “difficult” people, sometimes plagued by genuine mental illness — but Rudi’s overreacting to perceived insults (especially the scene involving the Russian waiter) seems to call for an explanation that doesn’t dismiss it with a shrug: Well, you know, artists . . . — or else settle for an easy answer: “He had a bad relationship with his father, so afterwards he had trouble with any obedience to authority.” Rudi has no such trouble when it comes to learning from his “good father” teacher, Pushkin. He’s very intelligent and can intuit which rules can help him and which hamper him, and thus should be broken.

My first inkling of it came when I first saw Rudi’s father. It’s obvious that this man is not a Slavic Russian, i.e. what so many assume is a “real Russian.” The Asian ethnicity is obvious. Now, I can’t claim any actual knowledge of the extent of ethnic prejudice in Russia, and especially the former Soviet Union, but Rudi’s assumption that the Slavic-Russian waiter sees him as a contemptible peasant from a backward part of the country is probably based on some exposure to this kind of bigotry.

Rudi’s mother’s name is Farida, and his father’s — Khamid. These are Tatar names. Nor is the family’s religious background Russian Orthodox. Is being a Tatar an important factor in shaping Rudi’s personality? The movie doesn’t really throw light on it, but it’s one of the reasons Rudi feels he’s different. And for a child and adolescent to feel different means to feel insecure.

(A lot of people are unaware that Rudi was a Tatar. Yes, he was the dazzling “flying Tatar.” But again, such is the power of the dominant culture that of course the world saw him as not only Russian but even “super-Russian” — all the stereotypes of the “melancholy Slav” and that mysterious “Russian spirit” that one French character in the movie decides is the secret of the Russian excellence in ballet.)

Another source of insecurity is having grown up in poverty. Rudi comes from a very poor family. A typical meal consists of boiled potatoes. He doesn’t have the advantage of having affluent, educated parents (although his mother loves music, and smuggles him in, along with his three sisters, to an opera performance — which is the beginning of his dream of “another world”). He manages to educate himself as best he can, but being around “cultured” people who had the privilege of attending elite schools must have been a strain — at least at times. And perhaps it also provided part of the extraordinary ambition to be better than they thought themselves to be, to excel at something which the Russians revered: ballet.

But trying to become the best-ever male ballet dancer creates another layer of difficulty for Rudi. Back when Rudi was training, ballet was typically perceived as feminine. Of course Rudi’s macho father would disapprove of his only son’s unmasculine pursuit. Khamid is a military man and a hunter. His son in a ballet school? It’s easy to imagine Khamid’s loud, blatant contempt.

And then, as if we didn’t have enough sources of “differentness,” there is Rudi’s sexual orientation. Though he did have a few relationships with women early on, his homosexuality is an established fact (alas, he even died of AIDS).

And for a while at least there is also the suffocating guilt about his affair with Pushkin’s wife, who shamelessly forces herself on him. “It’s killing you,” his (first?) gay lover tells him. Feeling guilty would increase any feelings of inferiority. And the wife refuses to be discreet. Rudi grows even more sullen and bad-tempered. The affair is indeed killing him.

But at least that’s a temporary factor, unlike belonging to an ethnic minority. But simply not being Western is another strike against him, Rudi feels. He knows that the Westerners feel themselves superior — they are the masters of the world. They may swear that they are not racist, but they were raised with certain stereotypes. And again Rudi feels like an outsider — not so much in the world of ballet, but when dealing with ordinary Frenchmen, for instance.

And, last but not least, he’s short. Men who are below average in stature — well, I won’t quote the numerous studies. We know.

(By the way, Rudi’s defensive outbursts might have some viewers call him “feisty.” But note that “feisty” is applied to women rather than men, and dogs like the chihuahua rather than German shepherds; to flyweight boxers, not to the heavyweight ones.)

*

You may say that this is all exaggerated — who thinks of Nureyev not as a fantastic dancer but rather as an uncouth Tatar peasant? Does anyone actually call him that? No — at least not in this movie (although he imagines that this is what the Russian waiter thinks of him). But it’s enough that certain stereotypes exist, and even though at the rational level the person may know that such stereotype are false, at the emotional level they do affect self-image and self-esteem. There is simply no escaping the dominant culture. Add to this the problems with his father, and you can see why Rudi craves to be valued with such intensity that he perceives insults where none are intended.

To say that he feels different is an understatement. He is doomed to be a perpetual outsider, a “white crow.” The movie’s very title states its main theme: this man sees himself as different — to put it mildly. On the other hand, if the compensation for that differentness is one of the factors that lead a person to become the best male dancer of his generation, there is more reason to celebrate than to lament.

Rudolph Nureyev in 1961, after his defection.

Rudolph Nureyev in 1961, after his defection. Mary:

When I think of Nureyev's story I think of the phrase "against all odds." It has the shape not only of a Balzac novel, but of a classical play: the hero coming from obscure, humble, origins, outside the mainstream of the dominant society, and through sheer talent, will and determination, with the assistance of a wonderful mentor, reaches the pinnacle of his heart's desire. Then, at the end, tragedy, loss, and a horrible death.

He was so many ways an outsider — in his ethnicity, nationality, sexuality, and his art. He transformed the possibilities of his own life, making them larger, greater, wider, moving Moscow to Paris to London. He changed the art of the male dancer in ballet with his passion, strength and athleticism. I remember seeing him in The Corsair — his performance electric, an almost impossible soaring … powerful and physical… not the ethereal movement of traditional ballet.

And when he partnered in those years with Fonteyn… exquisite, heartbreaking, tender perfection.

And then the end, a tragedy of our times, the ruin of his instrument, the body, in a merciless modern plague, before anyone understood much about it, and no one knew how to treat it, or even slow the march of its relentless progress. Those early days of the AIDS epidemic were full of mystery and terror, and for the victims on that raft, no hint of rescue on the horizon.

Oriana:

At the very end of White Crow, with the credits rolling, we get a bit of black-and-white film footage of Nureyev’s leaps and pirouettes. He is indeed flying. Unforgettable.

*

Given all his disadvantages, how did Rudi get to be a great dancer? Hard work and self-discipline — and the support of a wise teacher. And his almost incredible drive: he wouldn’t leave the school building until he “got it right” — he was always trying to improve his dancing. Thanks to Pushkin, he also understood that dancing feeds on the performer’s understanding of life, so he was trying to broaden his life as well — to understand masterpieces of visual art, for instance.

A friend explains to him why he’s so fascinated with Gericault’s “Raft of the Medusa”: Because it starts with something ugly and creates beauty out of it. And that, in the main, was the story of Nureyev’s life: against all the deprivations and obstacles, through his hard work he got to the point of effortless-seeming “flying.” On the stage at least, he created that enchanted world he craved since childhood. The rest is the mystery of greatness.

But there is something more about Gericault’s painting: it represents not only desperation, but hope. It’s shows the moment the men in front of the raft spot a ship on the horizon. The ship is barely visible — I’ve always missed it before — but the movie highlighted it with a close-up. That’s why the two men who can still stand tall are waving banners of cloth. And we know from history that the ship did rescue the survivors — only fifteen of them still alive out of the original 150 who boarded the raft (the higher-status crew and passengers got into the lifeboats, but the lower-status people were put on a make-shift raft, which was supposed to be towed by the captain’s boat; when the captain saw that the towing slowed down the boat, he cut the rope). Five of the fifteen survivors died shortly after being rescued, so only ten were left to tell the horrific tale.

Théodore Gericault: The Raft of the Medusa, c. 1819

Théodore Gericault: The Raft of the Medusa, c. 1819When Rudi keeps visiting the Hermitage while he lives in Leningrad, he’s fascinated with Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son. This is stage of his life where the “good father” — his teacher Pushkin — is of great importance. But in Paris he’s ready for the terror and hope of The Raft of the Medusa.

*

By the way, I can’t help but notice that this movie has a classic Balzacian plot: a poor young man from the provinces arrives at the capital (Leningrad fits the category). The “provinces” are also the Soviet Union compared to the West. Hence Rudi’s defensive outburst when Clara expresses surprise that he’s read Malraux’s The Human Condition: “We are not savages! We read!”

*

“Success is not final. Failure is not fatal. It is courage to continue that counts.” ~ Winston Churchill

*

“It isn’t that the evil thing wins — it never will — but that it doesn’t die.” ~ John Steinbeck

*

HOW FASCISM WORKS

“Part of what fascist politics does is get people to disassociate from reality. You get them to sign on to this fantasy version of reality, usually a nationalist narrative about the decline of the country and the need for a strong leader to return it to greatness, and from then on their anchor isn’t the world around them — it’s the leader.” ~ Jason Stanley, How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them

~ “Fascist politics – which evoke a mythic past, which rely on a sense of unreality and victimhood, and which use the cloak of “law and order” to hide corruption and attack scapegoats – can be used to flexible ends, writes Stanley, a professor of philosophy at Yale whose previous book was an analysis of propaganda.

What if a regime, for example, used a dismal us-versus-them divide in national politics to destroy faith in institutions capable of containing its power – elections, an independent judiciary, the public forum – thereby eliminating checks on its own self-enriching schemes?

“Publicizing false charges of corruption while engaging in corrupt practices is typical of fascist politics, and anti-corruption campaigns are frequently at the heart of fascist political movements,” Stanley writes, helpfully, without once mentioning “Drain the swamp”.

What if the regime used the same divisive politics to build popular support for a tax system that preserves wealth for the most privileged while creating no new opportunities for everyone else? Would that warrant the term “fascism”?

“Since I am an American,” writes Stanley, “I must note that one goal appears to be to use fascist tactics hypocritically, waving the banner of nationalism in front of middle-and working-class white people in order to funnel the state’s spoils into the hands of oligarchs.”

Underlying Stanley’s equanimous appraisal of the contemporary political moment is a weighty personal history. Both of his parents arrived in the US as Jewish refugees, his mother from eastern Poland and his father from Berlin, where his grandmother posed as a Nazi social worker to free Jewish prisoners from Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

“My family background has saddled me with difficult emotional baggage,” he writes. “But it also, crucially, prepared me to write this book.”

“In all fascist mythic pasts,” Stanley writes, “an extreme version of the patriarchal family reigns supreme, even just a few generations ago …

“In the rhetoric of extreme nationalists, such a glorious past has been lost by the humiliation brought on by globalism, liberal cosmopolitanism, and respect for ‘universal values’ such as equality. These values are supposed to have made the nation weak in the face of real and threatening challenges to the nation’s existence.”

Stanley’s acute awareness of the power of the term, and the subtlety of his argument here, must contribute to the fact that he does not explicitly brand Trump a “fascist”. Nor does he harp on “Make America great again”.

It is a misfortune of yet-unknown dimensions that he does not have to.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/oct/15/how-fascism-works-jason-stanley-review-trump

*

MEMORIAL DAY TRIES TO HIDE THE UNBEARABLE TRUTH ABOUT WAR

~ “All the history books I’ve ever read and all the history I’ve lived through suggests what that is: Wars are less about conflicts between societies than about conflicts within societies. Every country has a militaristic right-wing, and nothing helps that right-wing triumph over their domestic enemies more than a state of war. And just like a pharmaceutical company that doesn’t want to cure diseases when managing them is so profitable, their top priority is never bringing the war to an end, but maintaining and expanding their power within the country.

Amazing enough, Donald Trump recently told the National Governors Association exactly this, even if neither he nor they understood what he was saying. “We never win. And we don’t fight to win,” Trump declared. “$6 trillion we’ve spent in the Middle East … and we’re nowhere.”

But obviously Trump himself is somewhere: He’s in the White House. And lots of that $6 trillion is somewhere too, in the bank accounts of defense contractors. So if you understand who the real “we” are, we in fact have won the war on terror and are still winning. U.S. politics have been shoved hard to the right, making Trump possible, and since 2001 the value of Lockheed Martin stock has sextupled. The real we likewise have no interest in “fighting to win” in the sense Trump means — because that would require raising taxes on billionaires and drafting their children out of Stanford and Yale to go die in the sand, something that would quickly lead to the defeat of any president who tried it.

This perspective on the purpose of war was directly expressed by George W. Bush and his circle before he ever became president. Texas journalist and Bush family friend Mickey Herskowitz was hired to write a Bush biography for the 2000 campaign, and spent hours interviewing him. Herskowitz later said that Bush was already thinking about attacking Iraq — because, Bush said, “One of the keys to being seen as a great leader is to be seen as a commander in chief.” According to Herskowitz, people around Bush, including Dick Cheney, hoped to “start a small war. Pick a country where there is justification you can jump on, go ahead and invade.” Why? Because, Bush told Herskowitz, that would give him “political capital” that he could use to “get everything passed that I want to get passed.”

In other words, the actual country of Iraq had little to do with the Iraq War. Its main purpose wasn’t beating Saddam Hussein, it was beating Americans who wanted to stop Bush from privatizing Social Security.

Meanwhile, the motivations of our official enemies are the same: i.e., they’re consumed with gaining power in their own societies, and from their perspective we exist mainly as bit players in that drama. Part of Osama bin Laden’s motivation was that he believed the attack would benefit Al Qaeda “by attracting more suicide operatives, eliciting greater donations, and increasing the number of sympathizers willing to provide logistical assistance.” Just excise the word “suicide” and bin Laden sounds exactly like George W. Bush, planning to inflict spectacular ultra-violence thousands of miles away in hopes of getting bigger campaign contributions.

What’s most surprising isn’t that politicians start wars to consolidate their own power, but that the people don’t always simply assume that leaders choose war for that reason. Of course, the main calculation for politicians when making decisions is whether or not those decisions will help tighten their grip on the levers of society.

That’s why we need a Memorial Day, I believe, and so does seemingly every country on earth. At Arlington and at all the world’s solemn military cemeteries you can witness the endless ocean of young men and women who have been shot, gassed, incinerated, ripped limb from limb, shredded, driven to suicide. In the best of situations they died because of talented warmongers in other countries. In the worst it’s because we ourselves were so weak that we handed over power to killers who were delighted to see us die if it gave them a three week bump in their Gallup approval rating. We have to draw a veil of consecration across all of it, because looking at it directly is unbearable.” ~

https://theintercept.com/2017/05/29/we-need-memorial-day-to-obscure-the-unbearable-truth-about-war/?fbclid=IwAR0VuMlwMHeUpJeD2QbhkRU1-S6hc6pdkqxAKyasZjNJ_ctIT4NJCNjdOsw

OUR UNDERSTANDING OF SLAVERY IS FAIRLY RECENT

~ “Since the middle of the twentieth century, our understanding of the American past has been revolutionized, in no small part because of our altered conceptions of the place of race in the nation’s history. And that revolution has taken place largely because of a remarkable generation of historians who, inspired by the changing meanings of freedom and justice in their own time, began to ask new questions about the origins of the racial inequality that continued to permeate our segregated society nearly a century after slavery’s end.

Published in 1956, just two years after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board decision called for school integration, Kenneth Stampp’s pathbreaking The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South turned prevailing wisdom on its head. His history, written with a premise of fundamental black and white equality, yielded insights about slavery quite unlike the conclusions of earlier writings based on unquestioned assumptions of black inferiority. The leading early-twentieth-century historian of slavery, Ulrich B. Phillips, had portrayed a benevolent system designed to uplift and protect benighted Africans. Stampp, deeply affected by the emerging civil rights movement, painted a very different picture. With vivid archival detail, he demonstrated that slavery was harsh and exploitative of those who, he explained in words that rather startlingly reveal both the extent and limits of midcentury white liberalism, were after all “white men with black skins, nothing more, nothing less.”

But the outpouring of research and writing about slavery in the years that followed went far beyond simply changing assumptions about race and human equality. It yielded as well an emerging recognition of the centrality of slavery in the American experience—not just in the South, but in northern society too, where it persisted in a number of states well into the nineteenth century. It also fundamentally shaped the national economy, which relied upon cotton as its largest export, and national politics, where slaveholding presidents governed for approximately two thirds of the years between the inaugurations of Washington and Lincoln.

Prominent among the new historians was David Brion Davis. Davis did not focus his primary attention on the experience of slaves or the details of the institution of slavery, but about what he defined in the title of his influential Pulitzer Prize–winning 1966 book The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (PSWC): slavery as a problem and contradiction in human thought and human morality, not just in American history but across both world history and geography from the Greeks onward.

Davis had himself experienced something of an epiphany on these issues during his military service at the end of World War II. A peripatetic childhood had taken him to five high schools across the North, yet he had never shared a classroom with an African-American. A training camp in Georgia introduced him to the injustices of southern segregation, but an incident on a troop ship carrying him to Germany at the very conclusion of the war made an even more forceful and lasting impression. Ordered to descend into the hold and enforce the prohibition against gambling among those quartered below deck, Davis discovered with dismay hundreds of black soldiers—who he had not even known were on board—segregated in conditions he believed not unlike those of a slave ship. Davis’s experiences in the army introduced him to the realities of racial prejudice and cruelty that he had never imagined existed in America’s twentieth-century democracy. The shock of recognition rendered these impressions indelible, but it was a chance circumstance of his graduate school years that seems to have transformed them into a scholarly commitment.

Davis came to see that slavery and its abolition offered an extraordinary vehicle for examining how humans shape and are shaped by moral dilemmas and how their ideas come to influence the world.

Historians are interested in change, and the history of slavery provided Davis an instance of change in human perception of perhaps unparalleled dimensions and significance. Understanding and explaining that change became his life’s work. Why, he wondered, did slavery evoke essentially “no moral protest in a wide range of cultures for literally thousands of years”? And then, “what contributed to a profound shift in moral vision by the mid- to late eighteenth century, and to powerful Anglo-American abolitionist movements thereafter?”

PSWC launched Davis’s inquiry with a focus on the “problem” at the heart of the institution in all its appearances across time and space: “the essential contradiction in thinking of a man as a thing,” at once property and person, object and yet undeniably an agent capable even of rebelling against his bondage and destroying the master who would deny his agency. Grappling with this contradiction vexed every slave society, but only in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did these inconsistencies begin to yield substantial opposition to the institution itself. After tracing the cultural heritage of these ideas from Plato and Aristotle, through the evolution of Christianity, into the thought of the Enlightenment and the seemingly paradoxical strengthening of both rationalist and evangelical impulses in the course of the eighteenth century, the first volume of Davis’s trilogy introduces the origins of modern antislavery thought.

It is hard to think of any scholar who has made a better case for the proposition that ideas matter and can even override power and wealth, as Davis makes clear in his oft-repeated point that emancipation ultimately triumphed even though slavery was in fact flourishing economically in the nineteenth-century world that abolished it.

Davis begins by introducing what he identifies as the “central theme” of the book: “dehumanization and its implications,” a theme that has indeed been central to his work since he was writing about homicide long ago. The debates over slavery in the era of the American Revolution, he had shown in the preceding volume of the trilogy, had left a perception of black “incapacity for freedom” as the fundamental justification for the perpetuation of slavery. These assumptions of black inferiority, variously characterized as innate in a discourse that allocated increasing importance to race, or acquired through the oppressions of the slave system itself, were held not only by whites. They deeply affected blacks as well, Davis writes, in a form of “psychological exploitation” that yielded “some black internalization and even pathology” but also “evoked black resistance.” As escaped slave and black abolitionist Henry H. Garnet described the “oppressors’ aim”: “They endeavor to make you as much like brutes as possible. When they have blinded the eyes of your mind,” then slavery has “done its perfect work.”

In both Britain and the United States, however, antislavery forces helped create the conditions for an emancipation that was, as Davis describes it, “astonishing…. Astonishing in view of the institution’s antiquity…, resilience, and importance.” Hailing this example of human beings acting so decisively against both habit and self-interest, Davis proclaims abolition to be “the greatest landmark of willed moral progress in human history.”

David Brion Davis has spent a lifetime contemplating the worst of humanity and the best of humanity—the terrible cruelty and injustice of slavery, perpetuated over centuries and across borders and oceans, overturned at last because of ideas and ideals given substance through human action and human agency. He concludes his trilogy by contemplating whether the abolition of slavery might serve as precedent or model for other acts of moral grandeur.

His optimism is guarded. “Many humans still love to kill, torture, oppress, and dominate.” Davis describes the narrative of emancipation to which he has devoted his professional life as “astonishing.” But even in his amazement, he has written an inspiring story of possibility. “An astonishing historical achievement really matters.” And so does its history.” ~

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/03/20/scholar-who-shaped-history

Mary:

The discussion of slavery and its long history, ending very recently — officially abolished and yet leaving remnants behind in modern “ human trafficking”, still no longer sanctioned but considered criminal — brought to my mind the idea of a kind of evolution in ideas and morality. Something present in human societies for thousands of years becomes, in a matter of a few centuries, no longer possible to defend and maintain. We are in no way done with this process, witness the upsurge in prejudice, hate and hate crimes, no doubt encouraged by the Trogdolyte-in-chief and his minions … which could not have happened were it not always there, ready to erupt when the situation allowed and encouraged it.

The hope encouraged by this historical change, the abolition of legally and socially sanctioned slavery, is that this process of moral evolution will continue, and allow for the development of a better world. Despite everything. Knowing no ground ever was or will be gained without setbacks, dangers, the threat of regression, there is yet great reason here for hope.

Oriana:

Yes. This article made me realize the same thing: if after thousands of years, the “peculiar institution” of slavery was abolished (at least in the legal sense; we know remnants remain, but that’s a far cry from having slave auctions in, say, New Orleans), then further progress is certainly possible. As always, it will be a bitter struggle against those who do not care about the misery of others as long as they preserve their privilege. There will be setbacks, and there will be hate crimes — some people really have to find a scapegoat, and basically must find someone, anyone to feel superior to. I wish schools made an effort to track children’s natural talents and then made it possible for those children to excel in at least one area. I’ve noticed that people who know they are doing excellent work — no matter how humble (I saw this with hospice aides, for instance) — are happy and fulfilled and uninterested in ranting against immigrants or defacing Jewish tombstones with swastikas. Such people have secure self-esteem — you don’t see them join hate groups.

*

~ “It occurred to me recently WHY RACIST "WHITE PEOPLE" HATE JEWS.

It's because historically they're used to being the ruling class, with no effort at all on their part. Laze their way through school, and graduate to a high position. "Let the lesser people do all the work, and I'll reap the profit."

But along came Jews, Chinese, etc, who actually work hard to improve their lives. And they earn it very well by making the world better. That must annoy the hell out of lazy, entitled people.” ~ Nathan Mattor

YELLOWSTONE FROM THE SPACE STATION

In Warsaw at the Square of Three Crosses there used to be a store dedicated strictly to maps -- including wonderful topographical maps, some of which were displayed in the shop window. To me those were just enchanting. But it's photos like these that provide an even greater enchantment — you see the "ribs," the whole fractal structure of the terrain -- and the delicate colors, and the thin veil of clouds in upper right.

*

THE EVOLUTION OF THE HUMAN FACE

“~ NYU News: How does the human face differ from that of our predecessors – and our closest living relatives?

Rodrigo Lacruz: In broad terms, our faces are positioned below the forehead, and lack the forward projection that many of our fossil relatives had. We also have less prominent brow ridges, and our facial skeletons have more topography. Compared to our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees, our faces are more retracted and are integrated within the skull rather than being sort of pushed in front of it.

NYU News: How has our diet played a role?

Lacruz: Diet has been considered as an important factor, especially when it comes to the mechanical properties of foods consumed – soft versus hard objects. For instance, some early hominins had bony structures that suggested the presence of powerful muscles for mastication, or chewing, and they had very large chewing teeth, indicating that they were likely adapted for processing harder objects. These fossils had unusually flat faces. In more recent humans, the transition from being hunter-gatherers to settlers also coincides with changes in the face, specifically the face becoming smaller. However, many of the details of this interaction between diet and facial shape are unclear because diet affects certain parts of the face more than others. This reflects how modular the face is.

NYU News: A raised eyebrow, grimace, and squint all signal very different things. Did the human face evolve to enhance social communication?

Lacruz: We think that enhanced social communication was a likely outcome of the face becoming smaller, less robust, and with a less pronounced brow. This would have enabled more subtle gestures and hence enhanced non-verbal communication. Let’s consider chimpanzees, for example, which have a smaller repertoire of facial expressions compared to us, and a very different facial shape. The human face, as it evolved, likely gained other gestural components. Whether social communication by itself was the driver for facial evolution is much less likely.

NYU News: Climate also plays a role in evolution. How have factors like temperature and humidity influenced the evolution of the face?

Lacruz: We see that perhaps more clearly in Neanderthals, which adapted to live in colder climates and had large nasal cavities. This would have enabled an increased capacity for warming and humidifying the air they inhaled. The expansion of the nasal cavity modified their faces by pushing them somewhat forward, which is more evident in the midface (around and below the nose). The likely ancestors of the Neanderthals, a group of fossils from the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain that also lived in somewhat colder conditions, also showed some expansion of the nasal cavity and a midface that jutted forward. While temperature and humidity affect the parts of the face involved in breathing, other areas of the face may be less impacted by climate.

NYU News: In the Nature article, you mention that climate change could affect human physiology. How could a warming planet change our faces?

Lacruz: The nasal cavity and upper respiratory tract (the area at the back of the nose near the pharynx) influence the shape of the face. Part of this knowledge derives from studies in modern people by some of our collaborators. They have shown that the shape of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx differ between people living cold and dry climates and those in hot and humid climates. After all, the nose helps warm and humidify inhaled air before it reaches the lungs.

The expected rise in global temperatures could have an effect on human physiology – specifically, how we breathe – over time. The extent of these changes in the face will depend, among other things, on how much warmer it grows. But if predictions of a 4 degrees C (about 7 F) rise in temperatures are correct, changes in the nasal cavity might be anticipated. In these scenarios, we should also take into account the high mobility

of gene flow, which is an important factor as well, so the effects of climate change can be difficult to predict.” ~

https://earthsky.org/human-world/how-why-human-face-evolved-to-look-as-it-does-today?utm_source=EarthSky+News&utm_campaign=ddef4bbdf8-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_02_02_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c643945d79-ddef4bbdf8-394935141

WHY DO DOGS MAKE US FEEL GOOD?

One big reason: They stimulate our brains to create oxytocin.

Oxytocin is a hormone that the brain excretes during certain social interactions. Specifically, it’s created in the hypothalamus and released by the pituitary.

Scientists have found that oxytocin:

helps us bond with our friends, romantic partners, and family (especially children)

prompts our bodies to heal themselves

helps us trust each other

reduces anxiety, fear, and stress

THE DARK SIDE OF OXYTOCIN: US VERSUS THEM

~ “According to research by Carsten De Dreu:

Human ethnocentrism—the tendency to view one's group as centrally important and superior to other groups—creates intergroup bias that fuels prejudice, xenophobia, and intergroup violence. Grounded in the idea that ethnocentrism also facilitates within-group trust, co-operation, and co-ordination, we conjecture that ethnocentrism may be modulated by brain oxytocin, a peptide shown to promote co-operation among in-group members. … Results show that oxytocin creates intergroup bias because oxytocin motivates in-group favoritism and, to a lesser extent, out-group derogation. These findings call into question the view of oxytocin as an indiscriminate “love drug” or “cuddle chemical” and suggest that oxytocin has a role in the emergence of intergroup conflict and violence.

Indeed, in another study de De Dreu reports

the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment showing that the hormone oxytocin promotes group-serving dishonesty. Compared with participants receiving placebo, participants receiving oxytocin lied more to benefit their groups, did so quicker, and did so without expectation of reciprocal dishonesty from their group members. A control setting ruled out that oxytocin drives self-serving dishonesty. These findings support the functional approach to morality and reveal the underlying biological circuitries associated with group-serving dishonesty.

Annus argues that the facilities for both religion and nationalism are implicitly given by modules in brain architecture. Religious and national feelings emerge as natural products of the pro-socially wired brain. Therefore, he thinks that a human society without a religion or national feelings is impossible.

An authority on the ancient Near East, Prof Annus notes that in Mesopotamia Ishtar was both a goddess of love and also of war. The goddess of war and love might seem contradictory for the Western taste as we know that the Christian Madonna makes no war. The reference to oxytocin makes excellent sense of this seeming contradiction in the nature of ancient Near Eastern goddesses and reveals that people in antiquity already well observed what modern science is only beginning to discover.” ~

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-imprinted-brain/201610/the-dark-side-oxytocin

*

UNSAFE CHEMICALS IN BREAD

~ “Give us this day our daily foam expander. It may sound odd, but in America, your loaf of bread can contain ingredients with industrial applications – additives that also appear in things like yoga mats, pesticides, hair straighteners, explosives and petroleum products.

Some of these chemicals, used as optional whiteners, dough conditioners and rising agents, may be harmful to human health. Potassium bromate, a potent oxidizer that helps bread rise, has been linked to kidney and thyroid cancers in rodents. Azodicarbonamide (ACA), a chemical that forms bubbles in foams and plastics like vinyl, is used to bleach and leaven dough – but when baked, it, too, has been linked to cancer in lab animals.

Other countries, including China, Brazil and members of the European Union, have weighed the potential risks and decided to outlaw potassium bromate in food. India banned it in 2016, and the UK has forbidden it since 1990. Azodicarbonamide has been banned for consumption by the European Union for over a decade.

But despite petitions from several advocacy groups – some dating back decades – the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) still considers these to be Gras or “generally recognized as safe” to eat, though plenty of experts disagree.

“The system for ensuring that ingredients added to food are safe is broken,” said Lisa Lefferts, senior scientist at the consumer advocacy group Center for Science in the Public Interest. Lefferts, who specializes in food additives, said that once a substance was in the food supply, the FDA rarely took further action, even when there was evidence that it isn’t safe.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest petitioned the FDA to ban potassium bromate two decades ago due to cancer concerns, but the FDA’s response, according to a letter from the agency, was that it couldn’t examine the issue due to “limited availability of resources and other agency priorities”.

That has spurred consumers to take matters in their own hands. Bowing to pressure from a petition started by Vani Hari, author of the popular blog FoodBabe.com, numerous chains including Subway, Wendy’s, McDonald’s and White Castle dumped azodicarbonamide in 2014. That same year, the not-for-profit Environmental Working Group (EWG) released a list of more than 500 products containing ACA. Today, that number is about 200.

EWG has also found potassium bromate, sometimes appearing on food labels as bromated flour, in at least 100 items sold in the US, including Swanson’s chicken pot pie, Goya’s chorizo croquettes and Nathan’s pepperoni and provolone stromboli.

As more American consumers become savvy to these ingredients, more companies are phasing them out – but not everyone. Arby’s still has ACA in its croissants, French bread sticks, and sourdough breakfast bread while Pillsbury includes it in tubes of breadstick dough.

It’s not just so-called dough conditioners in bread. Two preservatives, BHA and BHT, subject to strong restrictions in the EU, are widely used in baked goods in the US. These emulsifiers keep fats and oils from spoiling, but the International Agency for Research on Cancer suggests there is sufficient evidence that BHA causes tumor growth in lab animals, with more limited evidence for the same in BHT.

While some companies are removing controversial ingredients, their replacements aren’t necessarily much better or all that different. “A number of other companies have switched from potassium bromate to potassium iodate in their bread, but potassium iodate is not well tested and may also pose a slight cancer risk,” Lefferts said. “It might also lead to excessive iodine intake. While iodine is an essential trace element that the body needs, too much can be harmful.”

The World Health Organization has recommended against adding potassium iodate to flour since 1965, yet the EWG lists more than 600 products that include potassium iodate, including Sara Lee hot dog buns, Safeway’s Signature Select whole wheat bread and Oroweat Italian bread.

For the past two years, the Environmental Defense Fund has been challenging the Gras rule in federal court, seeking to have the regulatory process declared “unlawful”. As of April 2019, the request is awaiting a judge’s ruling. In the meantime, consumers concerned about additives in bread may have to resort to Hari’s strategy: petition the companies themselves.” ~

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/28/bread-additives-chemicals-us-toxic-america?utm_source=pocket-newtab

ending on beauty:

A liquid moon

moves gently among

the long branches.

~ William Carlos Williams, Winter Trees

No comments:

Post a Comment