They didn’t bring me a letter today:

He forgot to write, or he went away;

Spring is like a trill of silver laughter,

Boats are rocking on the bay.

They didn’t bring me a letter today . . .

He was still with me just recently,

So much in love, affectionate and mine,

But that was white wintertime.

Now it is spring, and spring’s sadness is poisonous.

He was with me just recently . . .

I listen: the light, trembling bow of a violin,

Like the pain before death, beats, beats,

How terrible that my heart will break

Before these tender lines are complete.

~ Anna Akhmatova, translated by Judith Hemschemeyer

(By the way, a wonderful selection of Akhmatova’s poems in Hemschmeyer’s translation has been published by Shambala books -- that small-size jewels that fit in a purse or a pocket.)

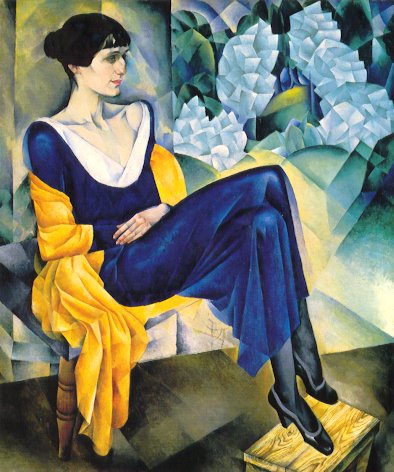

First, let me clarify that I think Akhmatova was a great poet, and the “slave of love” in the title is not meant to disparage her in the slightest. Akhmatova was also one of those lucky individuals who found their vocation early in life. She certainly wasn’t going to stop writing to please a man, though she duly records how some men thought that for a woman to be a poet was “ridiculous.” All the famous poets of her time were men. Eventually Marina Tzvetayeva was to gain recognition, though never the kind of popular acclaim won by Akhmatova.

While Tzvetayeva presents herself as a very unusual woman with whom it may be difficult for other women to identify, Akhmatova speaks in a way that any young woman can identify with. Feminism notwithstanding, and speaking from observation as well as personal experience, it’s hard for a young woman to concentrate on matters such as career choice. Typically, the center of her life is romantic love. Can we blame her? A lot of it is biological: a woman’s brain is wired for empathy and love since her great task is to be a mother. She doesn’t need to apologize for that.

Yes, you may say, but what about the obsessiveness: “They didn’t bring me a letter today” -- and it’s the end of the world. In modern terms: he forgot to call this morning! No email for two days! The technology has changed, but a great need for loving contact remains.

(Something in me says, “Really now!” -- especially when reading the last stanza, which I don’t believe for a minute. But that’s the posthumous self interrupting. Let’s ignore it.)

Byron made the famous observation:

Man’s love is of man’s life a thing apart,

‘Tis woman’s whole existence.

Times have changed, but have they totally changed? Since I don’t want to be accused of making broad statements, let me stay with personal experience. Much had to happen before I could call myself

a woman with two hearts,

one of which doesn’t

need love.

That poem (“Baba Yaga”) was not written until my late thirties. My first poems were mostly poems of obsessive love. Women poets used to joke about the “to be burned” pile to which such efforts should be consigned. We are embarrassed to have sounded so crazy about a man who now strikes us as hopelessly boring, disappointing, and not half as talented as we were. But let’s forgive ourselves: we were young. Romantic love was the most exciting thing in our lives, the most radiant, the last ruined refuge of the sacred and the ideal. Was it possible to live without it? No. We truly believed it, and, at the time, we were probably right.

I wasn’t “really me” until my mid-thirties. That makes me a lost soul until then, and a late bloomer, I know. But I can’t help noticing that I have plenty of company among the women I know. Again, I know I need to beware of broad statements. My story is my own: my early writing efforts came to an end when I heard the verdict, “Maybe the talent just isn’t there.” I didn’t hear the “maybe.” I heard: “The talent is not there,” and my barely awakening desire to be a writer withered.

I tried other fields, and nothing really worked. I couldn’t “find myself.” Then I fell madly in love. Pardon the cliché, but “madly” says it best. And I began writing again. And he who was god said, “You have talent.” And my life changed.

It changed again when I took a class on modern German poetry, and encountered Rilke. Rilke showed me what poetry was. He taught me seriousness. I could say that Rilke changed my life, and conceal the embarrassing idolatry that preceded my falling in love with Rilke’s work, and with poetry in general. But for the sake of honesty I admit: I started out as a “slave of love” and did not get serious about writing until Rilke,

Stevens, Dickinson, lots of suffering, and enough serious work got me to the point where I could say that writing was my vocation and the most important thing in my life.

“ON THE CUSP” BETWEEN YOUNG SELF AND WRITER

I remember the time when I first refused to meet my lover because I would rather spend the time by myself, reading and writing. It was a revelation to both of us. Eventually, and for reasons that had nothing to do with me, that young man committed suicide. For me, part of the shock was realizing that all men were ultimately going to let me down -- or rather, they were not going to achieve anything for me; I had to walk my own path. That’s when I realized that I wasn’t as dependent on romantic love as I used to be; now I had something else to live for. I barely hint at it in this poem:

COLD CITY

When it’s green after winter rains,

I imagine you straining away

from roots that seek to pierce

your chest, nail down your hands.

You shape yourself back,

Adam from the earth;

the skin stitches itself,

regathers loose fibers.

And I, on the other shore

of the river of breath,

read the bronze plaque

as if I couldn’t understand

that you are now a dash

between two dates.

The hills shimmer so green,

I almost reach to pull you up –

and for a minute the sky stops.

Then the wind brings the sharp

tang of eucalyptus leaves,

the traffic’s hum and drone,

its prayer to move on, move on.

I straighten and walk away,

down the mowed slopes

toward the cold city.

~ Oriana © 2013

*

The setting here is Los Angeles, the Holy Cross Cemetery where walkways between gravestones have names such as Lane of the Most Precious Blood. And it was at this cemetery that I stumbled on a stone that said: Bela Lugosi. It was startling. First, I was beginning to realize that someone with a lot of pathology was an energy vampire, and I was no longer willing to waste my time and energy on the wrong man, dead or alive. Second, even though I was no particular fan of Lugosi’s, he was a real artist who did what he did at the level of excellence.

And that was precisely what I was now interested in: excellence. Art.

I was changed. Love was no longer my “whole existence.” What happened to the romantic fantasies that used to sweep over me every night as soon as I lay down? “He” no longer appeared to play the piano for me, dance with me, sweep me away with tender whispers. Instead -- I know this will sound funny -- I was pondering the right title for the poem I was still working on. I was obsessing over a line that didn’t work, or even a single word.

“I’m no longer waiting for my ‘Twin Flame’,” I confided in a friend. “So what kind of man are you interested in?” she inquired. I wasn’t sure. “A PUBLISHER!” she triumphantly exclaimed. I didn’t deny it.

Not long after “Cold City,” I wrote this poem:

IN THE HUMMINGBIRD PAVILION

on raw concrete past an iridescent

veil of morpho butterflies,

wings not trembling nor folded

in prayer, but spread like a cape,

black silk, two yellow eyes –

the Bela Lugosi moth.

Bela, whose tombstone

I found in Los Angeles,

at the Cemetery of the Holy Cross.

Engraved in strict granite,

only name and dates –

slow syllables welling up,

in black flight swooping down,

in a crimson hush:

a shadow, a shudder, a hiss –

I mean kiss –

*

Bela, perhaps this moth

is your true memorial.

Something of you, with black wings –

Fear too has its rituals, dresses

in capes and fastens fangs.

But when they taunt, “You never

loved. You cannot love” –

the vampire confesses,

I too can love –

a crucifixion, even as I linger

in the Hummingbird Pavilion,

happier than all the children

whose memory is daylight

and will self-destruct –

while I watch the Bela Lugosi

head-down on the false stone.

Taste is caution. Style is

daring. On black wings

the false eyes warn

art is love and will uncloak

hidden self you didn’t know,

waiting in the vivid dark,

the Great Undead

watching from the wall.

~ Oriana © 2013

This is a poem I like to read around Halloween. But it’s not meant to be frivolous. At a deeper level the “Great Undead” are all the immortals who inspired me: not really Bela Lugosi but the likes of Rilke and Dickinson.

I realize I could end the post right here: the triumph of art. A woman “finds herself,” becomes a poet and a writer, and is no longer so much at the mercy of romantic love. Alas, a worse vampire emerged: what is commonly known as “po-biz.”

Ideally, an artist should be pure of heart and not desire recognition. Alas, and poetry is said to be the worst this way, there are plenty of poets and writers who start by falling in love with books and writing, but end up bitter and disillusioned after dealing with, ahem, “the market.”

I was no exception. I had published and won some awards, but seemed to hit the same kind of ceiling that so many others were to storm in vain. We’d get together and lament how it’s “all about who you know.” There were times when I felt nothing short of despair. The overcoming of that despair led me to a much happier stage: what I call “being posthumous.”

still not the right species . . .

THE SURPRISING BLISS OF BEING POSTHUMOUS

“Post-humous” -- “after the dirt” (thank you, Phil Boiarski, for this enlightening translation). After the toil and soil of youth (and beyond), after the lost illusions and shattered ambitions.

“Posthumous”: the stage of life and the state of mind where you no longer feel you “should” do anything. Been there, done that. It’s an incredible relief to realize that I’ve been published in over one hundred magazines, so I don’t need to strive for more magazine publications for my resumé. I’ve published, I’ve won awards, it’s enough. I no longer feel that I need to accomplish anything -- what relief! Done with striving, straining, cracking a whip over yourself. Done with the desperate need to prove myself -- to whom? My mother, even after her death? To the woman who said I had no talent? To the man who said I did? To the shaking seventeen-year-old I was, boarding a Russian-made jet that would take me to the first airport in the West?

Dead, all dead.

Posthumous: a Buddhist and Taoist ideal that always sounded like a deep truth to me, but I despaired of ever being able to relax into it.

Who knew aging could be so wonderful? For one thing, it’s no longer possible to have a child, so the torment caused by the idea that I “should” have at least one child is history. Now I know that I don’t need a child anymore than I need to climb Mt. Everest. Admirable, yes, but the “need” and “should” are history.

I don’t even need to die with honor.

Let it be, let it be . . .

In the posthumous state of mind, it’s not just that finally you know you can’t have everything; it’s that you no longer want to have everything. And this is the gift of growing older: torment and anxiety fall away because possibilities close, the options are behind you -- and that’s fantastic. Some doors have closed for good -- hurray! How wonderful not to have the burden of choice. Now I understand what people mean when they praise the wisdom of closing your options as early as possible. Keeping the doors open creates the constant draft of anxiety.

Basically, this is the “heaven of no desire.” I’ve had glimpses of it earlier. It was wonderful to roam around Saks Fifth Avenue looking at this or that luxury item and feel no desire whatsoever to buy it. I left the store feeling buoyant, floating: there was nothing in that storehouse of vanities that I needed or wanted: not the $250 moisturizing creams nor the $1,000+ dresses. In fact the place struck me as ridiculous: there were much better ways to spend money (hint: “buy experiences, not things”).

Being a poet and writer also gave me many wonderful glimpses of what it’s like to write with hardly any effort, trusting that the best things will well up from my cognitive-creative unconscious -- those neural circuits that are the “back burner” of the brain. Actually all cognitive function is unconscious -- note how thoughts simple rise up like foggy blossoms. But one can mess it up by obsessing and getting anxious, as if the perfect title or the perfect ending had to be coined instantly. Every writer eventually learns that the greatest mistake is trying too hard.

As Leonard Kress observed, all this sounds like moving away from the Path of Desire to the Path of Renunciation. If so, long live renunciation! It feels more like the path of finally doing what I want to do most, without wasting time and money on trivia.

Could I have found this path sooner, say at twenty-five? No, I had to waste a lot of time and some money on trivia before figuring out what was important. Youth was a terrible struggle precisely because I didn’t know what was important. Maybe wisdom could have come earlier -- but maybe not, and so what? It takes what it takes: making lots of mistakes and learning through suffering. The doors of perception are cleansed with tears.

The Joy of Harvesting

One reason that makes it relatively easy for me to forgive my younger self her endless mistakes is the fact that somehow, between migraines and heartbreaks and rejection slips, or rather increasingly after the heartbreaks, after the dirt, miraculously or merely inevitably, I did manage to write a lot. The one bit of wisdom I obeyed was trying to get a lot of writing done while I could; I realized that later on I might not be able to keep on writing. Except for rare instances of white-heat inspiration, writing from scratch is never easy. But it’s almost always possible to revise a bit, to polish. Sometimes it’s even possible to deepen and to add insight. And that daily work is a joy.

I always wanted an unfailing, reliable source of joy. Thanks to my tormented younger self, I have this joy. I like to think of it as “harvesting.”

As Mary Oliver puts it in this passage from “At the Lake” (White Pine):

Inside every mind

there's a hermit’s cave

full of light,

full of snow,

full of concentration.

I’ve knelt there,

and so have you,

hanging on

to what you love.

**

I am not saying that “post-youth”/“post-dirt” is a carefree paradise. That’s not how life works. “Shit happens” is still the First Noble Truth (thanks, Dave Bonta!) But now you know what’s important, and you have more resources. “It’s only money” gains reality, as you realize that time and not being stressed (health!) are vastly more important than trying to avoid paying for valet parking. And, knowing what is important, you can go to that hermit’s cave in your mind and stay close to what you love.

And yes, you realize you are moving toward the no-self, toward being literally post-humous . . . And there is a purity about writing from the place of that knowing.

*

The wonder of waking up to white wet mist. The air clean after rain, and the sharp smell of autumn -- the closest, in California, that we get to winter.

Sunday: deep mist:

trees floating above the trees

Sunday: deep ash

a willingness to be words

fading from the page

~ Sutton Breiding

Hyacinth:

Hyacinth:I am a fan of Akmatova. Her lines are alive like electricity . . . “spring a trill of silver laughter” (I typed “trickle of laughter”!!)

and "light, trembling bow of a violin"

I admire Tsvetayeva too. I read her biography and it made me want to cry --disbelief about all that happened to her and her children. I knew she was an admirer of Rilke and that endears her to me even more. She wrote to him: "You are not my favorite poet. You are poetry."

In your “Cold City,” I especially like the line "now (you are) a dash between two dates.”

I think when we are young, we are in love with being in love rather than with a person. We are into romance.

I was able to call my self a poet for the first time at Squaw Valley poetry conference. I was 70.

I think poetry is meant to be shared even if not published.

Sutton's “Sunday" is as always touchingly beautiful.

Oriana:

Akhmatova has a great sense of music. Her poems are exquisite in Russian. They are formal, but her content is modern. She is very personal and intimate.

Tzvetayeva and Rilke: perhaps the only time when Rilke was corresponding with another great poet. Alas, he was already ill with leukemia, and Marina didn’t know it.

The thrill of infatuation is certainly a factor in itself; I think that’s what you mean by “being in love with love.” As to the love object, the young aren’t usually that fussy. They don’t yet know that there is a huge difference between just being in love and being in love with the right person -- when you know that it is the right person, and you want to make it last.

Of course in a way you have been a poet since childhood, but in terms of a steady output of serious work -- that always takes maturity, though you certainly outdo everyone else in your late blooming. But when you started blooming, wow! You keep astonishing us.

Poetry is definitely to be shared. I was never happy with publication in magazines, because there is no response. Readings give me a greater sense of sharing, and now of course the blog. I love having readers not just in the US, but also in Poland, Russia, India, Australia, Japan . . .

Charles:

This is so encouraging to young poets.

Then the blog becomes inspiring to every aging person.

Favorite line: "The doors of perception are cleansed with tears."

Oriana:

Alas, no substitute for living and learning through mistakes. No self-help books can do it for us, no gurus. But some suffering is needless, self-imposed. As I keep saying, I’m so thrilled and amazed to see that older really means happier!

For one thing, you do close the door on a lot of trivia and concentrate on what you can do best, and that which brings the most happiness. As for health, avoid fructose and, when a problem strikes, seek out the best specialists. Family practitioners are pretty useless, in my opinion, and can even be dangerous.

Scott:

Great post and a nice addition to your last one on aging. It is indeed a blessing to know that either age, or talent or ability has taken so much off the table by 50; at least it has for me. A great Clint Eastwood line states 'A man has to know his limitations.' I would add to that it's a very wise man who learns that, and the younger the better.

I know now there will be many things I can't do anymore; many goals are just not attainable. But there is enough left to do, to enjoy, and the pleasant memories of the past to reflect on. That it's enough, it truly is. The love of wife and child, my friends, the 'warm river of books and black coffee' and of course my Nantucku project. Of course it's frivolous and lighthearted but at the same time the most serious thing I have ever done and will be the greatest of Quioxtic quests as it will never be completed. Oh how true Melville was when he said “God keep me from ever completing anything.” To have work to do -- and I mean 'pleasurable' work -- is truly a gift.

Oriana:

The work we love doing for me comes ahead of romantic love because work is a reliable source of life-sustaining pleasure and meaning. Romantic love always ends -- it’s simply too intense. The brain can produce its own amphetamines and other pleasure-related chemicals only for so long --maybe it’s protection against getting too exhausted from being on “speed,” i.e. the infatuation stage. Long-term love is another matter. Mutual emotional support is a great treasure.

At the same time, the ability to fall in love does not seem to decrease with age. The same neural circuits are ready to be activated even at eighty and beyond. The problem is finding someone to fall in love with. But then you read of nursing-home romance.

Still, for me work is where the meaning is. I hope never to run out. But I’ve already started taking it easy, without striving, without pressuring myself with deadlines. How sweet it is.

No comments:

Post a Comment