*

THE WOMAN WHO VOWED TO KILL

SEVEN GERMANS

told to my mother by a stranger on the train, 1945

Her husband’s broken body thrust

against the electric fence.

She dressed in black, lit a candle

in church, and swore:

seven Germans, by her own hand.

The days grew. The caw of crows

rang in hoarse, nagging echoes.

One afternoon, a knock on her door:

two German soldiers in retreat,

without food, without sleep.

She let them in.

They slumped down in the chairs.

Frost lilies shrouded the windows.

In the bedroom, a loaded revolver

pressed cold steel into slips and brassieres.

She stared at those frost-red, fear-eaten

young boys’ faces, flecks of snow

on their coats and hair —

then turned toward

the kitchen, and made them tea.

They cupped numb fingers

around the porcelain

and swallowed sips of heat.

A salvo of shooting

ricocheted far-off in the street —

She touched her hand to her mouth.

They nodded and hurried out,

turning into footsteps, then silence.

Sunday, she wanted to light

two more candles, two draft-torn

hearts of flame, but didn’t dare.

~ Oriana

*

‘We were sure the Russian army would protect us’: fury after Ukrainian incursion into Kursk

As tens of thousands flee their homes in border region, many say government downplayed threat of invasion.

Lyubov Antipova last spoke to her elderly parents almost two weeks ago, when she first heard rumors of a Ukrainian incursion, and begged them to leave their village in Russia’s Kursk region.

The threat seemed unreal – Russian soil had not seen invading forces since the end of the second world war – and Russian state media initially dismissed the invasion as a one-off “attempt at infiltration”, so Antipova’s parents, who keep chickens and a pig on a small plot, decided to stay in Zaoleshenka.

The next day, Antipova saw photos online of Ukrainian soldiers posing next to a supermarket and the office of a gas company. She recognized the place immediately: her parents live about 50 meters away.

“All those years my parents didn’t think they would be affected,” Antipova told the Observer by phone from Kursk, carefully avoiding using the word “war”, which has been officially outlawed in Russia. “We were sure the Russian army would protect us. I’m amazed how quickly the Ukrainian forces advanced.”

Ukraine’s incursion into Russia has laid bare the apparent complacency of Russian officials in charge of the border. Many local people accuse the government of downplaying the Ukrainian attack or misinforming them of the danger.

The Kursk incursion caught Alexander Zorin, a custodian of the Kursk Museum of Archaeology, at an excavation site in the village of Gochevo, where he and his colleagues have been digging the 10th- and 11th-century burial mounds every summer for three decades.

Zorin thought the buzz of drones, jets and thud of artillery was routine since his team had witnessed a similar activity during two previous summers. Sudzha, the epicenter of the offensive, was 40km away.

“Officials’ reports were not scary at all: ‘100 saboteurs went in’ – but then it went up to 300, 800 … It was impossible to get a clear picture,” he said. “We decided to leave only after we saw locals who had been evacuated from there and told us to go.”

The official evacuation from the area was declared a day later.

Many in Kursk blame the government and state media for keeping them in the dark in the face of mortal danger, with outraged residents sharing messages on social media.

“I don’t even know who I hate more now: the Ukrainian army that captured our land or our government that allowed that to happen,” Nelli Tikhonova wrote on a Kursk group at the VKontakte website.

On Tuesday evening, when Ukrainian troops were already in Sudzha, Channel One news claimed the Russian army had “prevented the violation of the border”.

The next day President Vladimir Putin kept referring to a “situation in the border area of Kursk”, eschewing any mention of the incursion into Russian territory.

For days, state television has been showing military bulletins, reporting successful Russian attacks on Ukrainian troops in the “border area” without specifying if a foreign army was still on its soil. State media has covered the plight of tens of thousands of displaced Russians who fled their homes before any evacuation was organized – but state TV mostly calls them “temporary evacuated people”, not refugees or IDPs (internally displaced persons).

Russia’s emergency officials eventually put the number of IDPs from Kursk at 76,000. Air raids have become routine in Kursk, a city of about a million people, with many locals ignoring the sirens or sheltering in safer spots, said Stas Volobuyev.

But it was the influx of displaced Russians from the border areas that brought home the reality of war just a few dozen kilometers away.

“Things happened in the past two and a half years but the scale was completely different,” Volobuyev said. “I work in the city center, and every day I see people queueing for humanitarian aid. There are so many refugees, they have nothing. People had to flee in shorts and flip-flops.”

Volobuyev, whose wife is volunteering to help the IDPs, and Antipova, whose parents have not been heard from since the day of the attack, laments the failure to help the refugees and to stop the incursion.

The Kremlin has earmarked 3bn roubles (£26m) on a fortification line in the Kursk region, and a new territorial defense force was supposed to ward off the incursion. Antipova recalled seeing a high number of border guards during her last visit to Sudzha in May but spoke bitterly of the community having to crowdfund for troops stationed there.

“Locals were bringing them supplies. I’m really annoyed that the government and the army keep saying the troops have all they need – while we had to chip in for drones and underwear.”

As Sudzha was plunged into a communications blackout, Antipova went to IDP centers in Kursk to look for her parents. Liza Alert, a nationwide charity for missing people, said on Friday it has missing notices for nearly 1,000 people in the region.

The last thing Antipova heard from the village was that an elderly neighbor had also stayed put, which makes her hope that the man and her parents would “go to the basement and sit it out”. She had little hope of the official response after others saw “there’s a war on, and officials were doing nothing”.

“It’s scary when you see you’re on your own and you have no one to turn to,” she said. “Volunteers are doing the work. Local authorities are nowhere to be seen.” ~

Elena Gold:

It is 11th day of the Ukrainian incursion in the Kursk region, and by now it’s revealed something strategically important: the Russian Federation does not have an army to "advance all the way to the English Channel" as they threatened.

Sure, Russian troops can raze to the ground Ukrainian villages in Donbas with their aerial bombs and fill them with corpses of their stormtroopers, thrown in “meat attacks” by Russian commanders with no pity or count. They can still fire missiles at Ukrainian cities, although most of them get shot down.

But Russia does not have an army to defend its own territory.

It was first shown by Yevgeny Prigozhin, who managed to pass with a military convoy nearly all the way to Moscow (shooting down Russian planes and helicopters as they went).

And now it’s shown by the Ukrainian armed forces. Even in the fortified border regions with Ukraine, after 10.5 years of the military conflict — and 2.5 years of the full-scale war, even there the Ukrainians just rolled in and Russians began surrendering by hundreds.

Truly embarrassing for Putin — and it can get worse.

*

HAMAS AND “RUNNING AMOK”

There is a phenomenon first observed in Malaysia, another Muslim country, called “running amok.” It's actually classified in psychological manuals as “Amok Syndrome.” The sufferer, in the face of unsupportable shame and humiliation and with no possible hope of relief, arms him or herself and goes on a public murder spree intended to result in their own deaths at the hands of the authorities. In the US we call it “suicide by cop.”

Hamas is in an untenable situation. They rely utterly on the charity of others, including their hated enemies, the Jews. All attempts at defeating Israel have been squelched. Their support among their fellow Arabs is fading away and they find themselves increasingly dependent on the hated Shiites and liberal Westerners.

There is no scope for advancement or success in Palestinian society. Things are so bad that strapping on a suicide vest and blowing something up is a legitimate career path for many young Palestinian men. A martyr's death seems preferable to an ignoble, dishonorable existence.

The intent of the October 7 massacre was to commit a crime sufficiently vile as to enrage the Israelis and elicit a no-holds-barred, full-scale attack that would kill everybody in Gaza, man, woman, and child. It's the Freudian Death Wish (another Jewish contribution, goddamit), Muslim style.

They want to die. They want us to kill them. Israel's scrupulously humane prosecution of this urban war campaign (approximately an eighth of the number of civilian deaths expected in this sort of fighting) is even more humiliating. They can't even beg for death right!

Sucks to be them almost as much as it sucks to deal with them. ~ Marc Clamage, Quora

Ellyn:

Take hate curriculum out of schools and mosques. Allow women to vote and hold jobs, create a market economy as a start. Do not throw unearned money at the problem and watch it funnel into terrorists hiding in Qatar, Iran, Lebanon and Syria. Don't pretend you didn't know the money allowed in was building tunnels and bombs.

Leopoldo Suarez: THE PATH THEY CHOSE 50 YEARS AGO

They are a defeated people who act as such. The path they chose 50 years ago (corrupting the minds and souls of their children) brought them nothing but misery and dishonor.

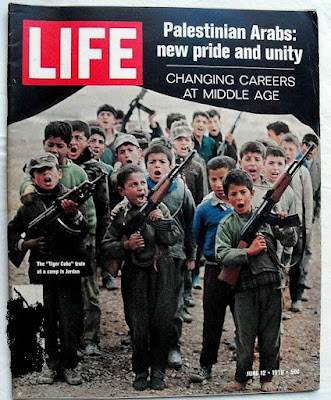

Young Arab boys being trained to kill

*

BEYOND MOTHERING: ANN PATCHETT AND MATERNAL AMBIVALENCE

For a long time, I didn’t realize that my irritation at society’s oppressive prescription for motherhood was anything more than my state of being. This frustration buzzed on the periphery of my awareness so persistently, became a thing so familiar, that I didn’t acknowledge or identify it. When I finally did, it was through literature.

Ann Patchett is one of the most effective novelists today on maternal ambivalence, precisely because she writes compelling, full characters who unapologetically commit to decisions about their own maternity. This distinction from most other novels helped me to see that I was not alone.

Giampietrino: Diana the Huntress

Giampietrino: Diana the Huntress

In 2013, Ann Patchett gave a reading at Politics & Prose bookstore in my hometown of Washington, DC.

In retrospect, I can see I was at an extremely vulnerable place in my life. I was still finding my feet, following a split from my long-time, mortgage-sharing, dog co-parenting boyfriend. I was in my thirties, single, and had achieved none of the life milestones many of my contemporaries already had.

And then Patchett signed my copy of State of Wonder, adding, “Monica, live a life of wonder.”

I went away thinking about how to do that. I had allowed my relationship to limit my choices; I put off grad school at his request, and buried my ambition to be a writer so that I could contribute financially to our lives together. But in the aftermath of our split, I was only lonely. When I confided this to my stepmother, who was home with my two much younger half-sisters, she laughed and said, “I’d love to be lonely sometimes.”

It sparked an idea for me: what if, instead of alone, I was free? It took some time, but I eventually summoned the courage to enroll in an MA in Creative Writing in London.

When I was asked to choose a book for the module on Reading as a Writer, I chose State of Wonder because of its impressive plot and structure. It is a literary adventure, with the protagonist, Marina, searching the Amazon for a missing person who may have discovered a miracle infertility treatment. When I began my doctoral research on literary characters who expose the “maternal instinct” as a myth, I returned to State of Wonder and discovered a new reading of it: Marina does not want children, goes on a life-altering trip, and bonds with an orphaned child. Her decisions about that child’s future are wrenching and complicated, and interrogate many of the tropes we often read about motherhood.

I soon realized that there are more examples of non-maternal characters in Patchett’s novels. Like, almost all of them. And although it took me many years to connect the dots, Patchett’s heroines set an example for me that society broadly does not offer.

Patchett has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, won the PEN/Faulkner Award, and was awarded the National Humanities Medal by President Biden. She is a celebrated author, and yet this prominent element of her work is not widely discussed: most of her novels feature a mother who is missing or a woman who is ambivalent about motherhood. Critically, the reason for the mother’s behavior is rarely explained, and never sufficiently for the children left behind. Generally, the mother is not a bad person. Sometimes she’s even a very good person, objectively speaking.

*

The Patron Saint of Liars, Patchett’s first novel, was published in 1992. Each of three sections of the novel are told from the point of view of a different protagonist, but the first narrator, Rose, is the central character. Rose is young, Catholic, married, and pregnant. When we meet her, she is fleeing her old life for a home for unwed mothers, where she will continue her pregnancy and give the baby up for adoption. She decides that her penance for abandoning her husband and child will be to sacrifice her relationship with her mother—the worst thing she can imagine. She tells no one where she is going, and, of course, tells no one at the home that she is actually married.

This is a dramatic opening for a novel, but things settle down as Rose makes friends in the home. All the other women wish they could keep their babies, but they are unmarried and ashamed of being pregnant. Most plan to labor in secret for as long as possible so that they have more time with their babies before the adoptive parents carry them away.

Rose does not explain herself to anyone—even the reader—but when her friend goes into labor, Rose suddenly marries the only man on the grounds, and they keep her baby. While some may read her decision to keep her child as her “maternal instinct” kicking in, she can’t bear to stay; her initial instinct to leave her first husband and give up her baby were the “right” ones for her. We don’t get an explanation from Rose on her abandonment of her daughter and second husband, but that is because she can’t see her ambivalence as a lack; it was never there.

This is the trait all Patchett’s heroines share: their actions are inexplicable until they suddenly shape into the most predictable behavior we can imagine. Rose’s decisions are driven by a persistent see-saw between guilt and self-preservation. She does not want children or marriage, but she believes she must make these traditional choices. Her need to conform consistently and predictably undermines her own desires, but she can never sustain her adherence to others’ expectations of her.

In The Magician’s Assistant, the protagonist, Sabine, is clearly a caregiving figure, but spends her life fully committed to a gay man, giving up on the hope of having children. The novel Run includes several mothers, but their roles are shifted and traded in such a way that force the reader to question the bounds of maternity and fertility.

Nearly thirty years after The Patron Saint of Liars, Patchett’s eighth novel The Dutch House (2019) features siblings Danny and Maeve, who have been abandoned by their mother, Elna. As adults, they learn Elna’s reasons for leaving. Narrated only by Danny, this novel is less about understanding his mother’s inexplicable actions, and more about whether her children can forgive her.

The disclosure of Elna’s motivation is something of an evolution in Patchett’s work. Like in her first novel, we see how the children were affected by the mother’s desertion, but in this case, even without the benefit of direct narration, we do get an explanation from Elna. Danny is unsatisfied, however, reporting “Of course it wasn’t just the house or the husband. There were the two children sleeping on the second floor who went unmentioned.” This narrative shift leads neatly on to Patchett’s latest novel, featuring the maternal narrator Lara, Tom Lake.

The clever structure of Tom Lake gives the reader access to Lara’s private memories, alongside the slightly censored version of her life as she shares it with her adult daughters. Her life story begins by merely falling into a short-lived acting career and even shorter-lived relationship, but what follows is a series of considered decisions to achieve what she actually wants for herself—not least of which is an abortion. “A nurse stood beside me and held my hand and I’m here to tell you, I felt nothing but grateful.” Her explanation is succinct and powerful, conveying even more conviction than Rose or Elna ever does.

Rose is conflicted and unhappy because she accepts obligatory roles. Elna is more peaceful because she has done what she believes to be right, even while feeling guilty for leaving her children. Lara may seem, on the surface, to have conceded a more traditional role—she works on an orchard, is happily married and has three wonderful daughters. If she were on Instagram, she might be a tradwife. But her life has been full, and she has demonstrated a commitment to pursuing things that make her happy, no matter how others perceive her choices.

Tom Lake is not without maternal ambivalence, however. When Lara’s eldest daughter Emily announces that she will not have children, Lara responds in an all-too-familiar way: “’You never know.’ I try to make my voice neutral. ‘You might change your minds later on.’” She doesn’t mean it in the condescending way this feedback is usually delivered; she means that she has changed her mind about what she wants and doesn’t want Emily to be afraid to do the same.

*

Women who choose a different path to motherhood have more prevalent role models today than they did even ten years ago, yet since the 1990s, Patchett has portrayed full lives beyond motherhood—providing a counter-narrative to the one prescribed by society. In fact, Patchett has discussed her own decision to not have children and the backlash she faced. In 2011, she told The Guardian “I never wanted children, never, not for one minute, and it has been the greatest gift of my life that even as a young person I knew. It freed me up tremendously. Children are wonderful but they’re not for everybody, and yet it never stopped. To constantly have people tell me that I didn’t know my own mind and I didn’t know my body was kind of outrageous.”

Just because someone can be a mother does not mean they want to be a mother. Patchett’s ambivalent mothers are complete, in spite of their failures. In fact, their lives and their children’s lives are perhaps more full thanks to the mother’s willingness to interrogate her own desires. The beauty of Patchett’s work is that her characters progressively do not bend to societal expectations, but her novels are not explicitly about maternal ambivalence. They are about people in dogged pursuit of their best lives—like us all.

https://lithub.com/beyond-mothering-considering-ann-patchetts-novels-of-maternal-ambivalence/

*

IS DOING ABSOLUTELY NOTHING THE SECRET OF HAPPINESS?

Few of us have the money to take a long pause from work or caring responsibilities. But, as I found, even a day can make a difference.

You might imagine that escaping from your everyday life would involve relocating to a Hebridean croft or attending a series of rejuvenating retreats. But, according to Emma Gannon’s new book project, A Year of Nothing, it could be as simple as staying at home.

“I did nothing,” writes Gannon. “I stopped replying to emails. I used my savings. I slept. I borrowed a friend’s dog. I ate bananas in bed. I bought miniature plants. I read magazines. I lay down. I did nothing. It felt totally alien to me.”

For Gannon, the sabbatical was enforced after she experienced burnout, caused by chronic exhaustion from occupational stress. “All the while, I was keeping diaries,” she says. “Writing down the ‘nothingness’ of my days. I journaled all the things I noticed, the stuff I usually ignored, the people I met, the kindness of strangers, the magical coincidences – the smallest, tiniest uplifting glimmers.”

Am I alone in feeling a surge of envy reading Gannon’s litany of aimlessness? It’s not even as if I’m in need of a break. Recently I went on a relaxing holiday to Málaga. I admired the Pompidou Centre, stared out to sea at the distant blur of Morocco and guzzled bitter-orange-filled dark chocolate from the supermarket. In other words, bliss. On my return after two weeks, I plunged back into my working life recharged and raring to go. But, inexplicably, days later, I found myself intensely craving more time off, and experiencing a low-level discontentment that only intensified in the following days.

Was I having some kind of existential breakdown? I turned to the psychologist Suzy Reading, author of Rest to Reset: The Busy Person’s Guide to Pausing With Purpose, for advice. She suggested that, like many people, I probably struggle to identify what kind of rest I need. “For people who do a lot of socializing and interacting with other people for their work, they might find that what they actually need to replenish is silence and solitude.”

This definitely struck a chord with me, an extrovert who gets energized from being around others, but I was skeptical that spending time alone could possibly be rejuvenating. “If you are struggling to recharge, a good place to start is by thinking about how you normally use your mind and body. Ask yourself, what kind of environments are you in on a daily basis?” says Reading. She cites the example of a teacher who spends all day guiding and directing others. In that case, taking a break might involve allowing someone else to make decisions, even if it’s just where to go for dinner.

“Many people often confuse rest with sitting down quietly. But given that many of us spend our working lives sitting, staring at a screen, for some, a better form of rest might involve listening to music or doing some form of movement. For some people, rest might involve embarking on a creative project, which allows them to express themselves in a new and different way.” Taking a very large chunk of time out, perhaps a year, is obviously not financially viable for most of us. But the good news is, it’s not necessary.

“The key is to allocate some time out from the hurly burly of life to reclaim some headspace,” says Reading. “If we make time to step away from our routines, it gives us a chance to realize what we can’t wait to get back to. It can help us to appreciate the things we actually enjoy.”

This all sounds great but my Calvinist work ethic is too strong to take more than a day or two off.

“Even though my book is called A Year of Nothing, you can just do a weekend of nothing,” suggests Gannon, although she warns that doing so may provoke pushback. “People are always asking me what I’m up to at the weekend and I regularly say: ‘Nothing’. The response is often: ‘Surely you have some plans’, and I reply: ‘Nope, none.’

Indeed, some people find that taking time out prompts a surge in productivity. Tamu Thomas, the author of Women Who Work Too Much, believes that, as a society, we do not value rest. “We need to understand that it is what fuels everything else in our lives. There’s an American sports coaching maxim that states: ‘The rest is just as important as the race.’ It’s so true.”

A former senior social worker, Thomas was conditioned from a young age by her Sierra Leonean family to value productivity and achievement over relaxation. She began researching the mind-body connection of taking adequate rest after she experienced a severe panic attack before giving evidence on a high-profile case. “I discovered the work of physician and researcher Saundra Dalton Smith. Her Ted Talk explains that we actually need seven different types of rest: physical, mental, emotional, sensory, creative, social and spiritual.

” Thomas observes that for many of us, particularly women, emotional rest is often the one that is most overlooked. “For those of us who are conditioned to over-function and who believe that our value comes from caretaking in every sphere of our lives, emotional rest is one of the most necessary types of taking a break. In order to address that, you need to start identifying the people that compromise your emotional well-being and then make choices about whether you want to carry on engaging with those people.”

It can be helpful to make time away from your responsibilities a regular part of your life, even if that presents logistical challenges. Shirley-Ann O’Neill, an art adviser and director of the Visual Artists Association, organizes her life around taking a reset week every seven weeks. “I intentionally leave my diary open without firm plans, allowing for spontaneous moments of rest and rejuvenation. I enjoy a leisurely morning with a cup of tea, going for peaceful walks in nature to clear my mind, engaging in creative pursuits like journaling or painting, and having impromptu outings to explore new places or try new cuisines. I’m a busy mum of three so this really helps to rest me. At first I felt guilty; now it’s an absolute must.”

Sometimes it takes a traumatic life event for someone to realize that they need to step back and reprioritize. When she lost her mother, and then a close friend, health mentor Sophia Husbands decided to make 2023 a reset year. “Circumstances meant it wasn’t appropriate to go jetting off somewhere,” she says. So she took radical steps at home. She used her savings and scaled back her freelance work to allow herself to re-evaluate her life. She reviewed her core values (a coaching exercise favored by personal development authors such as Brené Brown) and conducted a relationship audit.

“I looked at all the people in my life and asked myself whether they were making me feel neutral, depressed or uplifted. I analyzed both old and present relationships and determined who was not making me feel good. I decided to cull people who were not serving my best interests, and felt much better.”

I decide to try a reset of my own, and plan a mini sabbatical one Sunday. Unfortunately, I soon realize that unless I impose a structure of aimlessness from the start, I’m liable to just loll around doomscrolling. I go back to Gannon, who suggests: “Look at your diary and ask yourself, what can you get out of doing? Find things to cancel. You might be surprised because a lot of the stuff we feel obliged to do, we don’t really need to do at all.”

I find this surprisingly difficult. I don’t like letting people down but I press ahead anyway, although I do justify it because it’s for an article. “Sorry, I can’t make it, I’ve got to work,” I tell a family member, and then a good friend I was looking forward to seeing.

I go for an aimless walk to a park that I rarely visit. It’s a gray day yet it is surprisingly beautiful. I sit on a bench and watch the world go by, then head home and wonder how on earth I am going to spend the evening.

I do more ironing than I have done for the rest of this year put together, then I go through the laborious process of repotting a snake plant. How can it only be 7pm?

In truth, I go to bed early with the sense that this has all been a massive time-wasting exercise and feeling pretty grumpy. Next morning, though, it’s a different story. For once, I’ve slept soundly all night and have had an unusually vivid dream that has provided the answer to a problem I’ve been grappling with for some time. That morning, I have an idea for a new project. As I go about my day in an uncharacteristically cheerful mood, I realize something I’m sure wise sages have always known: doing nothing much can be surprisingly productive.

“CROSSING”: A JOURNEY TO ACCEPTANCE

Unfolding against the backstreet cobblestones and packed tenements of Istanbul, Levan Akin’s sophomore feature Crossing tells a quietly evocative—if familiar—tale of regret and unforeseen connections.

Retired Georgian teacher Lia (Mzia Arabuli) sets out to fulfill her sister’s dying wish of finding her long-lost transgender niece, Tekla, years after her transphobic parents disowned her. In Lia’s search, she’s saddled with an unlikely companion when a former student’s scrappy, ne’er-do-well younger brother Achi (Lucas Kankava), hungry to leave his tiny Georgian town behind, offers her Tekla’s new address—on the condition that she take him with her to Istanbul.

Despite their easy chemistry, the film’s premise runs the risk of falling into a tired, outdated trope: centering a trans person’s well-meaning yet ignorant cisgender loved ones at the expense of more nuanced explorations of queerness.

It’s the introduction of Crossing’s third lead, trans sex worker–turned–legal volunteer Evrim (Deniz Dumanli), that ultimately elevates it from its more formulaic trappings. Dumanli brings a lived-in warmth to Evrim, whose realistic day-to-day scenes serve as a direct counterpoint to Lia’s assumption that Tekla’s community is defined by isolation and debauchery.

It’s Lia who is most often alone, roaming her niece’s new city like a specter until her two younger companions draw her into the bustling subcultures around her. As Achi enlists Evrim to help them in their search, they find themselves in the homes of Istanbul’s tight-knit trans community, and Lia has no choice but to confront the ways in which she could have showed up for Tekla had she confronted the conservative rationale proliferating around her sooner.

As an opening title card points out, Georgian and Turkish languages are gender-neutral. So if gender is inconsequential in our characters’ languages, why should it matter so much in the real world?

An on-the-nose fantasy-realist climax aside, the film isn’t interested in pat resolutions for its characters’ wanderings. Thanks to Akin’s eloquent character studies, Crossing lingers in the mind far longer than its rudimentary setup would suggest.

https://chicagoreader.com/film/movie-review/review-crossing/

from ebert.com:

“Istanbul is a place…where people come to disappear.” This is the sad conclusion arrived at by late in this moving film by one of its principal characters, Lia, a stern-faced older woman who has crossed over into the Turkish capital from the Black Sea’s Batumi, a desolate-looking spot in Georgia. A retired school teacher, she has left her home after making a promise to her now-dead sister. The promise was to find that woman’s child, who’s living in Turkey. All Lia has to go on is a name, and the fact that the now-adult child is transgender.

The movie, written and directed by Levan Akin, begins in the messy, tumultuous house where Achi, a young man who’s for all intents and purposes still a boy, lives miserably under the thumb of his older brother. Lia happens by the house, is recognized by one of its residents, and on the spot Achi concocts a tale, saying he knows the niece, Tekla, and has an address for her. He attaches himself to Lia, who accepts his company reluctantly, and soon they’re off, settling awkwardly in cheap lodgings and combing the poorer areas of Istanbul with not much to go on but hope.

The two actors who play Lia and Achi, Mzia Arabuli and Lucas Kankava, are marvels. Kankava has a wide-open face that registers Achi’s boundless naivete, which is always there no matter how cocky or obdurate he makes himself. Arabuli’s own expression as Lia is often pinched, but as time wears on her, and as she starts to let herself go in a “what the hell” sort of way — she likes to dip into a bottle of a fermented drink called “chacha,” a habit she initially tries to hide from Achi — a pained vulnerability makes itself felt. These are two lost souls who make an unlikely temporary fishbowl for themselves, far from homes they may never return to.

On one of their ferry rides, Akin’s camera makes a graceful camera move away from the anxious Lia and Achi and settles on the more content-in-the-moment face of a trans woman, whose story the movie then picks up. This is not, as is soon made clear, Tekla. The character’s name is Evrim, and she’s a woman who’s found a purpose. Near to completing a law degree, she works for a trans rights NGO that also looks into various cases in poorer neighborhoods; at one point we see her springing a young boy and his younger sister, who act on the peripheries of the movie’s central story threads, from jail. She’s confident and compassionate, enjoys a fairly robust sex life, but she’s subject to condescension — at best — from the various authority figures she’s obliged to deal with. Deniz Dumanli’s portrayal of the character is extraordinary, grounded, vanity-free.

Lia and Achi’s story will intersect with Evrim’s, but not right away. Akin is here working in a tradition established in Italian Neo-realism — and by the end of the film, he shows he can turn on the viewer’s tear ducts as deftly as De Sica did in his prime — but his narrative approach brings a vivid freshness to the proceedings. The camerawork he concocts with cinematographer Lisabi Fridell, often shooting through windows and doorways, often gives the viewer a “fly on the wall” feeling, but never becomes voyeuristic. It invites empathy, not titillation. And the movie’s portrait of Istanbul — roiling, unglamorous, and yes, packed with stray cats — makes the city a character in and of itself.

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/crossing-film-review-2024

Languages, communities, lifestyles, borders, and values may separate us, but sadness and loneliness are universal, as is the desire to know ourselves and to find acceptance, forgiveness, and togetherness.

Crossing, writer/director Levan Akin’s film about an older Georgian woman searching for her trans niece in Turkey, understands and dramatizes that basic fact with an avalanche of empathy that’s all the more overpowering for being so gentle. Premiering in U.S. theaters on July 19 following its world premiere at February’s Berlin International Film Festival, it’s one of the year’s brightest, and most moving, imports.

In the small coastal Georgian town of Batumi, retired teacher Lia (Mzia Arabuli) arrives on the doorstep of a former student named Zaza (Levan Bochorishvili) who’s busy chastising his younger brother Achi (Lucas Kankava) for taking his car without permission. This is clearly not the first time the siblings have bickered over such matters, yet they pause their fighting long enough to invite Lia inside for a drink, over which she informs them that she’s looking for her niece Tekla, whose mother (Lia’s sister) has recently passed away.

Zaza claims ignorance about Tekla, but Achi remembers that she’s one of the trans girls who lived nearby until they were kicked out of their house. Upon departing, Lia is tracked down by Achi, who admits that he knew Tekla and has her address in Istanbul, where she’s living with friends. Arguing that he can speak a bit of Turkish and English (the latter from YouTube) and must get away from his brother, he convinces Lia to let him tag along on her quest.

With a head of curly black hair, a mole beneath her nose, and a stern expression consistently affixed to her face, Lia carries herself like a person with whom one does not trifle, and the younger Achi proves an initial annoyance to her. A brief trip to Lia’s house indicates that she had cared for her ill sister there. After gathering some tomatoes and cucumbers from the neighbor’s garden (and, in the morning, accepting a generous gift of pelamushi from them), Lia and Achi cross into Turkey, where he has never visited and she has only been once, years earlier. “It was all right” she says about Istanbul in her typically brusque manner. On their ensuing bus ride, Achi foolishly munches on the churchkhela being passed from passenger to passenger, and shortly thereafter winds up puking out the window—a sign of his immature irresponsibility.

Staring at a flirty woman on the bus, Lia remarks that Georgian women have lost all dignity. This suggests that Lia is a conservative with untoward opinions about the world into which she’s entering, and yet Crossing has no interest in being a simplistic scold. Once in Turkey, the duo board a ferry and director Akin’s camera lithely glides up and down stairs, considering the ship’s passengers and employees with the same casual warmth that it extends to its protagonists.

Those, it turns out, also include Evrim (Deniz Dumanli), a trans lawyer who disembarks from the same vessel and meets up with a friend, who chats with her about her latest boyfriend and her volunteering gig at an LGBTQ+-focused NGO. Evrim is in the process of getting her official female ID, and the way in which a doctor refuses to look at her during an office visit illustrates the everyday discrimination she endures, just as her decision to praise his hair on her way out demonstrates the kindness with which she faces it.

Lia and Evrim’s paths are fated to intersect in Crossing, although Akin’s script takes its time getting to its preordained destination, content as it is to travel alongside the aunt and Achi as they wander through bustling streets, up steep staircases, and down empty alleyways.

At every opportunity, the film reveals clues about its characters’ thoughts, feelings, and pasts through subtle expressions and interactions. That’s true whether it’s an encounter with a Georgian man that compels Lia to briefly come out of her shell (to unsuccessful ends), Evrim’s budding amour with a cabbie, or a chat with a trio of Turkish trans women who can’t understand anything Lia is saying (and vice versa) but who nonetheless share a moment when one of them is prompted to sing a melancholy song. Akin’s soundtrack is filled with similar woeful tunes, all of which reflect these individuals’ regrets, sorrow, and longing.

While Arabuli’s performance begins as an exercise in stone-faced dourness, the actress soon evokes the complex stew of emotions driving Lia forward on her mission. Her anger, despair, disgust, and self-recrimination are believable because they’re largely unarticulated and, moreover, uneasily reconcilable. Lia feels more than one thing about Tekla’s choices, as well as her own role in driving her niece to this place, and the film’s embrace of life’s untidiness bolsters its sympathy for her plight.

That additionally goes for its treatment of Achi and Evrim, who are likewise grappling with issues of rejection, alienation, and yearning for love and companionship. Crossing handles these dynamics with consistent deftness, such that even Lia and Achi’s surrogate mother-child bond resonates not as a schematic device but as an unexpected (if natural) outgrowth of their developing relationship.

Asked what she’ll do once she locates Tekla, Lia states that she has no future and thus no plans; “I’m just here until I’m not.” If she sounds forlorn, however, she isn’t without hope for reconciliation, absolution, and solace.

Crossing passes no judgment on its main characters, instead comprehending them from the inside out in all their knotty, contradictory, and ultimately optimistic glory.

Its spirit is so tender and welcoming that it’s impossible not to have enormous compassion for its wayward souls. Akin’s film is about estranged and adrift people who haven’t quit on mending themselves and the messes they’ve made (or have been saddled with), and its gracefulness and graciousness are equally enchanting.

In its poignant conclusion, Crossing offers little overt resolution but, in a vital sense, finds Lia completing the most important part of her odyssey. Akin doesn’t untangle his main character’s inner life; rather, he simply recognizes that healing is a process that both begins with oneself and is aided by those we allow into our lives and hearts.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/obsessed/crossing-review-years-brightest-and-most-moving-foreign-film

Oriana:

I agree with the reviews: this beautiful, melancholy movie subtly portrays a journey to becoming more accepting and emotionally giving. Lia starts out very hard-hearted; we get to see her gradual softening, opening up, and ultimately becoming accepting of those who choose a different path. In her fantasy* about meeting Tekla on a bridge — not an accidental location — Lia tells her niece that both her mother (in spirit, since she’s now dead) and aunt (i.e. Lia) completely accept Tesla’s right to live her own life, no matter what traditional taboos are broken. The family affection ends up being more important than the rigid views of a conservative society (i.e. Georgia, as contrasted with Istanbul, a vibrant metropolis more open to alternative lifestyles).

However, the movie completely skirts the issue of Islam and its oppressive gender stereotypes. At least once, we do hear a muezzin's call to prayer — but it blends with all the other sounds of the city, a choral symphony that speaks of inclusion rather than orthodoxy. In this city, which stands for humanity, no faith is the only true one — unless the faith in humanity, meaning that we are both good and bad, imperfect, in need of being forgiven and included. Crossing is ultimately a very loving movie.

Thus, even the scant portrayal if Islam is swallowed up by the drama of thousands of faces coming and going. It is indeed a city in which to disappear from those who insist on traditional lifestyle. It is also a city in which to let oneself go and dance, as Lia, once the best dancer in her village, discovers in what is perhaps the most joyful scene of the movie. Even aside from the dance, there is a kind of dance going on throughout the movie — there is a lot of movement, a lot of crossing of space — symbolic of the flexibility we need if we are to be truly a part of the current moment. Lia may be just a transient in Istanbul, but the city’s energy and openness to joy has transformed her and rejuvenated her. The grim older woman who thinks her life is finished becomes a warm and loving human being. We wish her love.

*

I wish to thank Charles Sherman for convincing me it was indeed a fantasy.

*

NARCISSISTS AND AGING

Narcissistic people get more empathetic, generous and agreeable with age, according to new research into the personality trait. But although their unreasonably high sense of self-importance may mellow, they do not fully grow out of it, the study involving more than 37,000 people suggests.

Those who were more narcissistic than their peers as children tended to remain that way as adults, investigators found.

And there are at least three types of narcissistic behavior to look for, they say.

WHAT IS A NARCISSIST?

Narcissist has become an insult often hurled at people who are perceived as difficult or disgreeable. We all may show some narcissistic traits at times.

Doctors use the term to describe a specific, diagnosable type of personality disorder.

Although definitions can vary, common themes shared by those who have it is an unshakeable belief they are better or more deserving than other people, which might be described by others as arrogance and selfishness.

The work, published in the journal Psychological Bulletin, comes from data from 51 past studies, involving 37,247 participants who ranged in age from eight to 77.

Researchers looked for three types of narcissist, based on behavior traits:

Agentic narcissists — who feel grand or superior to others and crave admiration

Antagonistic narcissists — who see others as rivals and are exploitative and lack empathy

Neurotic narcissists — who are shame-prone, insecure and overly sensitive to criticism

They studied what happened to these personality measures over time, based on questionnaires, and found that, generally, narcissism scores declined with age.

However, the changes were slight and gradual.

"Clearly, some individuals may change more strongly, but generally, you wouldn’t expect someone you knew as a very narcissistic person to have completely changed when you meet them again after some years," lead researcher Dr Ulrich Orth, from the University of Bern in Switzerland, told BBC News.

He says some narcissistic traits can be helpful, at least in the short term. It might boost your popularity, dating success, and chance of landing a top job, for example. But over longer periods, the consequences are mostly negative, because of the conflict it causes. "These consequences do not only affect the person themselves, but also the wellbeing of individuals with whom they interact, such as partners, children, friends, co-workers, and employees," he explained.

Dr Sarah Davies is a chartered counseling psychologist who has written a book on how to leave a narcissist. She told the BBC that although people may be arrogant or selfish at times, that should not be confused with true clinical narcissism. "Narcissists tend to be envious and jealous of others and they are highly exploitative and manipulative," she said. "They do not experience remorse or feeling bad, or have a sense of responsibility like other non-narcissistic people do.”

She says there has been a boom in interest about narcissism, driven by social media.

"To some extent that's helpful — it helps inform more people about it and to bring more awareness of this issue. However, like many mental health terms, the clinical meaning can get a little lost.

Dr Davies says we should be more discerning with the term. "I find it much more useful to be specific with naming behaviors and separate them. For example, a friend of mine recently called her ex a narcissist because he had ghosted her after they broke up. "

Being ghosted [suddenly cutting someone out of your life without explanation] is of course horrible, but he may not have been able to deal with a conversation after their relationship came to an end. It doesn’t necessarily mean he is a raging narcissist. "They were together a while and there were no other indications of his ‘narcissism'.

According to Dr Davies, some signs you may be involved with or around a narcissist include:

Constant drama — a narcissist needs to be needed and seeks chaos and conflict ;

No genuine apologies — they never really take full responsibility for their own behaviors ;

Blame game — they manipulate and exploit others for their own selfish gains .

Dr Tennyson Lee is a consultant psychiatrist with the Deancross Personality Disorder Service, based in the London borough of Tower Hamlets. He said the study was well-conducted and the findings were useful. "The good news is narcissism typically reduces with age. The bad news is this reduction is not of a high magnitude. "

Do not expect narcissism will dramatically improve at a certain age — it doesn’t.

"This has implications for the long-suffering spouse who thinks 'an improvement is just around the corner'," he told BBC News.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c2v0qq7z12qo

*

THE POLITICS OF MARRIAGE

The institution of marriage isn’t doing so hot. In the United States, fewer Americans are getting married than ever before, while many are getting married later in life, if at all. What’s to be done about it? According to journalist Lyz Lenz, blow it all up and start over.

In This American Ex-Wife, a blistering memoir-meets-manifesto about the fraught gender politics of marriage and divorce, Lenz details how the end of her marriage became the beginning of her life. Raised religious and married at a young age, Lenz walked away from an unsatisfying partnership to rebuild her life on her own terms, only to discover that happiness, liberation, and freedom lay on the other side. “I believed that I would be a sad sack single mom, like you see in all the movies, but when I got to the other side, I realized, ‘This is actually great,’” Lenz tells Esquire.

Weaving together a detailed history of marriage, sociological research, cultural commentary, and a frank dissection of her own personal experiences, Lenz paints a damning portrait of marriage in America: “an institution built on the fundamental inequality of women,” as she describes it. Yet the book is also a rousing and exuberant cry for a reckoning—one where couples can love freely, leave freely, and build meaningful partnerships based on the full and equal humanity of men and women alike.

ESQUIRE: You write, “Divorce is both personal and political. Our governments sponsor and prop up the institution of marriage with tax breaks and incentives, while making it nearly impossible to be a single parent.” In what ways is divorce political?

LYZ LENZ: Heterosexual marriage is the way we organize our society. It's a political system, and you don't have to look far to see policy solutions that rely on marriage as opposed to funding SNAP benefits, funding Medicaid, and so on. This isn't just a Republican thing, either—Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama have all promoted marriage programs in order to combat poverty and save the government from having to fund necessities like healthcare and childcare. Marriage also forms the foundation for our tax base; this is how we determine who gets tax breaks and who doesn't, who's contributing to society and who isn’t.

Divorce cuts at the heart of our social order. If you set up your society around heterosexual marriage, then women realize that society relies on their unpaid labor, that's destabilizing. We're living through a time of political backlash where states across America are trying to pass policies that make it harder to get divorced. The party line is, "We have to support the American family," but if that was ever going to solve our problems, then we wouldn't have problems as an American society. There are studies out there that say, "If you want strong relationships, if you want marriages to last longer, if you want to decrease the rates of domestic violence, if you want kids to stay in school, then you liberalize divorce laws.”

When women have options, they make better choices, but that's getting lost in this discourse. Right now, it's incredibly hard to get a divorce—a 16-year-old has an easier time getting married in America than a 42-year-old woman does getting divorced. Divorce is political, but it's also personal, because it's where our politics meet the bedroom. It's really hard to parse out.

I'm reminded of what you write in the book about how our social order essentially relies on the subjugation of women: “We need women to buy into romantic partnerships so that they will become the social safety net that our leaders and politicians refuse to create.”

We create all these fantasies of love and happiness and equal partnership to get women's buy-in. Relationships are worth trying for—love is beautiful and valuable! But when it gets wrapped up into a political system, that's a problem. I know so many couples who say, "We're going to do this equally. We love each other and it's going to be wonderful." Then they get five years in, have two babies, wake up one day, and say, "Wait a minute, how did we get here?" In a society that makes it impossible to afford childcare, they were always going to reach this point. In a society with a wage gap, the person whose job takes the hit will always be the wife. None of this is an accident. We would love to believe that we could love our way out of fundamental inequality, but we can't. We need to fundamentally rethink the system of marriage, and one of the best ways to do it is to liberalize divorce laws.

What makes getting divorced so hard, and what policy changes would make it easier?

It's hard culturally. People treat you like a pariah without even meaning to. I have wonderful friends, but I had to have some tough conversations with some of my coupled friends. I had to say, "You stopped inviting me to stuff and that really hurt my feelings. I miss you and I miss our friendship." Being vulnerable and rebuilding those relationships was really difficult. A lot of them said, "Oh my God, I'm so sorry. I thought you would be uncomfortable around couples."

So culturally, it gets really uncomfortable. So many women have asked me, "Why? What happened?" They wanted to know how bad it got in case they ever needed to leave. It becomes this destabilizing thing where you have to walk through people's insecurities while you're also going through your own tough stuff.

Politically, it's hard to get divorced, too. Even if it's amicable, there are waiting periods and laws. It takes a long time. It's expensive. You can roll into a courthouse to get a marriage certificate and roll back out, but with a divorce, you have to wait.

I'm sure you've seen the wave of op-eds advocating for more people to prioritize marriage; it all started with a David Brooks piece titled, "To Be Happy, Marriage Matters More Than Career." What do you think of this wave of discourse?

I'd love to fight David Brooks in the street over this column. He's basing this on some really flawed data from The Institute for Family Studies, which is a group that admitted to messing with their data during the gay marriage debate. They released all this data arguing that gay parents were bad for children, which was used in public policy discussions—then they later admitted that the data was flawed, and intentionally so. Journalists should think more critically about the data that they use. I'm an English major from a mid-tier college and even I can think more critically about this data than a New York Times opinion columnist.

That said, I think it's very telling that these cultural commentators latch onto flawed data. It makes them feel more comfortable. Nothing makes our society more uncomfortable than a liberated woman. We can't forget that 2017 was a huge year for women—we elected women at unprecedented levels and the #MeToo movement got a lot of men fired. That was deeply destabilizing, so it's not shocking to see this rollback. Marriage is a conservative institution that upholds social order, so whenever I see someone saying, "People just need to get married," or, "Marriage is hard work," my challenge is, "Who are you asking to sacrifice?" You make it sound egalitarian, but what you're asking is for women to give up their careers and take on additional labor.

The average man adds seven hours of labor to a woman's weekly workload. So what are you actually asking? "Marriage is hard work"—hard work for who? Who's making the therapy appointments? Who's hiring the babysitter? Who's cleaning the house and making dinner? I don't like to be gender essentialist, but when people say, "Marriage makes you happy," I do think it's important to ask, "Who? Why? How? Who is being made happy, and who's actually being made miserable?" A happy marriage makes you happy, but happy singlehood makes you happy, too.

The whole discourse is so anti-intellectual. I just wish we would think harder and have smarter conversations about it, but this isn't anything new. If shoving people into the institution of marriage fixed our society, we would have a fixed society. It's not about empowering people to be happy; it's about men being happy and women existing to support that happiness. I want better for my life. I want better for my children's lives. I was not put on this earth to be the crutch for someone else. I don't think you need a romantic relationship to live a full, happy life; you can find connection and joy in so many other ways.

The other thing we often hear in the op-ed industrial complex is that men are increasingly single and lonely, and apparently women should do something about that. What’s your response to that discourse?

Women's bodies are always the solution for male problems. Get a therapist like the rest of us! Women are also sad and lonely—we had a worldwide pandemic, millions of people died, everyone is sad and lonely, and somehow we're confused about why. If the requirement for your happiness is that someone else be miserable and make you food, is that real happiness? Your freedom should not rest on other people's unfreedoms. Your happiness should not rest on someone else's unhappiness. Men will feel alienated by that. Female liberation is always blamed for male alienation, but I refuse to believe that this is true. Again, the data shows that when women have freedom, everybody benefits. I hate this discourse because it's designed to shame women for being free. I think being happy is the most radical thing you can do. Fighting for a happy life, that shit is hard—it's harder than being married!

There's a whole industry designed to make women feel less miserable. I keep joking that if we liberalized divorce laws, the scented candle industry would tank, because women would suddenly be happy and wouldn't need all these products anymore. Men, have you tried reading a self-help book? Have you tried going to therapy? Have you tried texting your buddies and saying, "Hey, I feel sad. Anybody want to grab a beer?" There are very simple solutions for alienation. They should involve community; they shouldn't involve my inequality.

I really loved the chapter of the book about good men, and about the pervasive belief among not just men, but also the women in their lives, that they are “one of the good ones.” What’s your response to men who might read this book and think, “But I’m one of the good ones”?

If you have to insist upon your goodness, you do not have it. What's the bar for being a good man? We've got a really fucked up set of requirements for what it means to be "good," so if you're checking off all the masculinity boxes, that's not great. I have a newsletter and I'm always a little surprised when subscribers get defensive with me. I turn it back on them and ask, "Why are you insisting on your goodness to an internet stranger? What is it about what I’ve said that's made you feel so defensive?" Look at the statistics: there's a ton of data showing that even if you love your wife, you're still not doing the work you need to do, so go do it! If you're feeling defensive, go ask your wife, "Do I contribute?" If she says, "Thank you so much for asking—actually, you don't," then get better.

My publisher has been fantastic, but there was a conversation about how the title and cover of my book would make men feel. I said, "I'm done bending and pleading and trying not to step on the landmine of male feelings." I want men to feel uncomfortable when they see this book. I want them to feel on blast and on notice. Men's good feelings are not my job. My job is my liberation, and you can either get on board or not. I'm glad you liked the "not all men" chapter, because it was really important for me to write it. I actually don't care if you're good or not; I'm not always good! I don't think that life requires our goodness. We just have to be human, and I want to be just as human as any man is. To me, it's really not about the goodness of men—it's about the liberation and full humanity of women.

You do such a wonderful job of capturing why people fear and avoid divorce; I thought it was especially poignant when you wrote about how getting divorced means publicly saying to your community, “I was wrong,” and how hard that can be. How do you suggest that we as a culture reframe the way we think about divorce?

It requires reframing what we think of as a good relationship. We still have this cultural bias toward believing that a good relationship is a long relationship, and that's not always true. You can have a good, short relationship. We need to rethink, "What does success look like? What does happiness look like?"

If we learned one thing from 2020, it's that life is to be enjoyed, but we don't tell women to enjoy themselves. As a mother and as a wife, you always have to be nailing yourself to the cross or you're not good enough. My job is to get women off that cross. We need to rethink what a good relationship is and separate it from the idea of longevity, because not everything lasts forever, and that's okay. It's okay to quit and it's okay to change your mind. It's okay to say, "This was great, but it's not what I want anymore.”

What would you say to anyone out there who's divorce-curious?

I think there are a lot of people who are divorce-curious, and for a lot of them, the question is, "How bad does it have to be before I can leave?" I identify with that; I write about how I was looking at other people's miserable marriages and thinking, "I'm not as miserable as Shirley Jackson, so I can stay." I always say what my friend Anna told me; she said, "Your life is not a game of chicken. You don't have to wait for someone else to blink first before you swerve. Your happiness is enough of a reason." Your partner doesn't have to be a villain for you to be unhappy. That's why I wanted to write about the system of marriage, rather than making it an individual problem.

To the divorce-curious, I say: you're in a system that doesn't serve you, so of course it feels hard and of course you're unhappy. There are better ways to live. When I left my marriage, it's not because I thought being a single mom would be so fun. It was because I was so miserable that I couldn't stay. I believed that I would be a sad sack single mom, like you see in all the movies, but when I got to the other side, I realized, "This is actually great." According to a Pew study, 43% of Americans think that single motherhood is ruining our society, but being a single mom is the best thing I've ever done. Your happiness is not frivolous. You don't have to wait for someone else to blink first.

And I promise you, it's great on the other side. If you're divorce-curious, that's already telling you something about where you are and what you feel. I think that's a lot of people in America, and I wish them luck.

https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/books/a46789002/lyz-lenz-this-american-ex-wife-divorce-marriage-interview/

Mary:

It is undeniably true that our social system is built on the foundation of marriage and the nuclear family, and that marriage is based on the subjugation of women — easily demonstrated by the legal and tax structures, the economics of women's work and women's pay, and the frustrating failures of those couples trying to work out marriage as an equal partnership. The forces at work are historical, social and biological. They have existed for so long the "rules" and assumptions are almost unconscious, only obvious as constructs when analyzed from opposition...otherwise they seem simply "natural." That oppositional analysis has been the work of Feminists...oppression and injustice are seen, felt and lived by those on the bottom, and remain stubbornly invisible to those that benefit from the inequality. This remains true even after generations of struggle for equality.

I believe there can be no full freedom and equality for women as long as we remain unable to control and choose our reproductive lives. Without that power all other choices are circumscribed, limited and denied. Contraception and birth control are key to body autonomy — and that includes the ability to choose and have available safe and legal abortion. The lack of these things kept women from full and active agency in the world for most of history...made us limited and too often temporary creatures, who died or were physically depleted by constant pregnancies and childbirth, ignorance about the risks and dangers involved, and the complacency of men and their religions dictating that these trials and dangers were no more than woman's god ordained and inevitable lot.

Science and medicine have made women's freedom and equality possible. What we are witnessing now in the US is the fear of that freedom expressed by the Right wing male patriarchy in their determination to subvert those rights and freedoms, and force women back generations...back to where she has no choice nor ability to control her reproductive life. They even shore their repression up with fears about population decline — wanting to force, cajole, or bribe women back into producing lots of babies for the state. China and Russia have tried this to little effect. Here in the US they are working to eliminate choice by outlawing contraception (oh yes, they will) and abortion.

I believe motherhood should be a choice not a sentence. In order for that to come true many things must change, not just people's attitudes. Among the changes are all that has been mentioned, most importantly, social support for child care and child welfare, and support for mothers who are also workers and career women. We have a long hard way to go, but in many ways the current backlash is a measure of how much the unfreedom and inequality of women has been challenged. And we're not ready or willing to go back.

I could go on about the inequality embedded in marriage — another long hard struggle worked out by individuals with less than great success — and probably one of the most prevalent causes of conflict and dissatisfaction. But people still seem to want what marriage promises, even as long term unions seem to become rarer and rarer. It is hard for me to imagine a world without families.

Oriana:

Marriage is here to stay because it is a social contract. The state is supposed to enforce the financial obligations of the parents toward their offpsring. By the way, I know two women who kept paying child support; one (an artist) said that she wanted to experience pregnancy and giving birth, but not the daily chores of child rearing. As more and more people keep saying nowadays, she wanted to live her own life. She was fortunate to meet a man who was fine with that, and I think his parents (the child's grandparents) were supportive as well.

That support — and I mean doing the chores of child rearing, not just the money — is crucial if we want women to want to have children. Just yesterday I read in a mainstream source that only 45% of women wanted children. And it has become socially acceptable for a mother to say that if she could do it over, she wouldn't have had kids. That would have been unimaginable in the fifties or early sixties, where such an attitude would be regarded as "sick" or "selfish." Back then children were always "cute" and "sweet." Now it's OK to say that children are a lot of trouble and expense.

Perhaps it's become too normal to say that, from the point of view of collective welfare. Not that we should go back to the sexist fifties, but perhaps there should be some sincere voices in praise of parenthood. Above all, there should be more social support in the form affordable childcare and parental leave. And yes, easy access to birth control and abortion so that all children could know the joy of being wanted children.

I also like the saying that the abortion debate is not about whether a fetus is a person, but about whether a woman is. If she doesn't own her body and has no right to put education or career ahead of motherhood (which can be delayed until the circumstances are right), then she is a slave.

*

JOE: A NON-TRADITIONAL DIVISION OF LABOR IN MARRIAGE

Oriana:

*

HOMELESSNESS ISN’T ONLY ABOUT LACK OF HOUSING

Most of us have walked or driven by someone camped out on the sidewalk. Those of us who are parents might have heard this question from our kids: “Why do we have a home and that person doesn’t?”

You probably didn’t have a good answer. Bad luck? A shortage of housing supply and exploding prices? Mental illness? Addiction? Some combination of the four? But mostly you wish the answer wasn’t: “Because we live in an unfair society and we look the other way so that we can function.”

Kevin Adler is an activist and author of the book When We Walk By: Forgotten Humanity, Broken Systems, and the Role We Can Each Play in Ending Homelessness in America. He isn’t afraid of our children’s questions. In fact, he believes he has compelling and effective answers. Flying in the face of the learned helplessness that so many of us feel these days about the unhoused neighbors in our cities, Adler argues that we can stop compartmentalizing and actually do something about it.

I spoke with Adler about his book and how each one of us can be part of building a more hospitable country.

Courtney Martin: One of the fundamental arguments of this book is that homelessness isn’t just a result of economic poverty, but relational poverty. Can you explain what that is and why it’s so rampant?

Kevin Adler: Eleven years ago, I met a person experiencing homelessness named Adam who first attuned me to the concept of relational poverty. I’ll never forget his words: “I never realized I was homeless when I lost my housing, only when I lost my family and friends.”

Adam was in a very tenuous situation in life, but had been able to get by for a while through the support of his loved ones—staying with family, relying on friends for a bit of work or money, etc. When Adam’s access to social capital ran dry—perhaps due to an argument with a loved one, the unexpected death of a family member, or the like—his situation went from bad to worse.

Though we often think of poverty as a lack of financial resources, what Adam was describing was relational poverty, or the profound lack of nurturing relationships which, when combined with stigma and shame, leads to nearly unimaginable levels of isolation and loneliness among many individuals experiencing homelessness. As one unhoused neighbor put it in the early months of the pandemic, “You don’t need to teach me about social distancing, that’s my life already.”

Stories like Adam’s are not unique: As many as one in three individuals experiencing homelessness in the United States have lost their social support systems, attributing the immediate cause of their homelessness to a falling-out with or loss of a loved one.

Homelessness is a housing problem, but it is not only a housing problem. Aside from the lack of stable housing, relational poverty may in fact be the most universal characteristic of experiencing homelessness. As Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern have indicated in their recent book, “Homelessness risk is far greater for people with limited support from a community, low self-esteem, and a lack of belonging.” This is why [the Housing First model is not called] Housing Only: Indeed, one of the five principles of the Housing First strategy is social and community integration.

Finally, to better understand the significance of relational poverty for so many of our unhoused neighbors, we can look upstream toward our housing insecurity neighbors more generally. With 40% of Americans self-reporting that they would not know where to get $400 for an unexpected emergency, and over one in two Americans one paycheck away from not being able to pay rent, it is actually surprising that more people are not experiencing homelessness. Given these stats, how is it possible that “only” 1-2% of people in the U.S. experience homelessness at some point over the course of the year, rather than 10 to 20 times that? I believe one of the main reasons is due to family, friends, faith-based groups, and other forms of social support helping people get by.

To paraphrase Bill Withers, we all need somebody to lean on. We ignore relational poverty at our own peril.

CM: I really appreciated how you delineated the different reasons that this kind of disconnection can go on for so many years—barriers to access, like internet and cell phone, and administrative issues, for example—but also the emotional fractures. Your nonprofit reconnects folks by jumping over some of the accessibility barriers, but how do you help people deal with the emotional depths of reconnection? Seems like a tall order.

KA: We consider our work to be a first step toward reconnection, and try to set expectations and provide support on all sides accordingly.

For example, in most of the reunion cases that our community of volunteer digital detectives work on each week, it has been years or even decades since the last contact occurred. Thus, the messages we deliver (and encourage) from our unhoused neighbors tend to be openers to re-engage: “I love you,” “I miss you,” “I’m sorry,” “I’m thinking of you,” “I want you back in my life,” “I’m still alive.”

Our staff and global community of volunteers have a mantra (well, several, but here’s one of them): You know your relationships better than we do. Sometimes, reconnecting is not appropriate or in the best interest of one or both parties; tragic cases abound of homelessness resulting from domestic violence, LGBTQ+ youth escaping an unsafe home environment, etc. Sometimes, bridges have been burned between a person experiencing homelessness and most of their loved ones, and family members choose not to reconnect. We don’t believe reconnecting is a one-size-fits-all solution to homelessness. But we know that for many of our unhoused neighbors, it is an essential step toward lasting stability and well-being.

Finally, I think it’s important to note that though the process of reconnecting can be incredibly emotional, the experience of homelessness itself is incredibly emotional, physically devastating, and very isolating—the most heartbreaking cardboard sign I ever saw read, “At least give me the finger.”

When I started this journey by spending a year helping a few dozen of our unhoused neighbors share their stories, I was struck by how many folks talked at length about loved ones who often were no longer in their lives—beloved siblings, favorite teachers, children who are now adults. In other words, it’s not like family isn’t on the minds of our unhoused neighbors.

CM: I was so sad to learn that homelessness is growing among those over 65 and that a quarter of people experiencing homelessness are under 25. What does it say about our society that we tolerate such harsh lives for our most vulnerable? Are there contemporary societies where this is not the case, and what can we learn from them?

KA: Homelessness is a policy choice. Thus, there are plenty of other places where homelessness is not nearly as prevalent as it is today in the United States.

As one example, Finland has received widespread recognition for successfully providing permanent housing without preconditions and wraparound support services to most of its people experiencing homelessness. In 1987, there were 18,000 people experiencing homelessness in Finland. In 2023, the figure had dropped to 3,429.

By contrast, in 1987, there were 500,000 to 600,000 experiencing homelessness in the U.S. According to the 2023 PIT Count in the U.S., that figure has increased to 653,104 people. If we prioritized affordable housing and a robust social safety net for our most vulnerable residents, we would have a much smaller population of people forced to live in shelters and on our streets.

CM: Why do we accept such a broken, costly status quo in the United States?

KA: I believe in large part it is due to another form of relational disconnection: Many of us “housed people” are just as disconnected from our unhoused neighbors as many of them are from their loved ones.

When I give a talk, I tend to ask my audience two questions: “First, how many of you care about the issue of homelessness?” Every hand shoots up. “Second, how many of you know someone who is currently experiencing homelessness?” In response to this question, never more than 5–10% of hands remain in the air.

I believe this disconnection is part of the problem, for we don’t know who “they” are, as the mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, sons and daughters, friends and neighbors that they are. Instead, we largely see people experiencing homelessness as problems to be solved, not people to be loved. I believe we have a duty to keep reminding ourselves of the fundamental humanity of our unhoused neighbors, lest we lose a bit of our own.

Consider the aftermath of a flood or wildfire. For a brief period of time, we tend to rally around those who were affected, organizing food drives, building shelters, creating online fundraisers and advocacy campaigns, or passing emergency ordinances, in what sociologist Charles E. Fritz described as the emergence of the therapeutic community. We don’t look at survivors of these disasters as deserving of their situation—very few would ask, “Well, did they have the right kind of flood insurance? Why did they choose to live in such a vulnerable area?”

And yet, when it comes to homelessness in the U.S., we maintain a mindset of rugged individualism, and wonder what the person did or what is wrong with the person to result in their situation.

I believe the way to overcome this narrow-mindedness is through relationships and storytelling.

CM: You make a lot of structural suggestions, but one of them is guaranteed income, based on your own successful pilot. Tell us more about that.

KA: I began as a skeptic about basic income. Not so much whether our unhoused neighbors would use the money in a way we might consider wise, but whether a few hundred dollars a month would be enough to help people experiencing homelessness meaningfully improve their lives, much less get off the streets.

Fortunately, our volunteer community was wiser than me. In 2020, we created a phone buddy program, which matches unhoused neighbors with trained volunteers for weekly phone calls and texts. Within a few months of its creation, our volunteers began asking whether we could provide some money to their unhoused friend. Through their interactions, trust was built, relationships were built, and, with it, the desire to see their friend succeed and an understanding of the multitude of barriers keeping them from doing so.

And so, in December 2020, we created what turned out to be the first basic income pilot for individuals experiencing homelessness in the U.S.