*

LIVING WATER

I hurried to the greenest spot

among the lilies, followed

the shiny trail of water back

to the ancestral boulder:

from underneath the vertical face,

water as ancient as inner stone

pulsed forth to braid with light.

Deep fur of moss covered the rocks

in the newborn stream —

Moss! I was so used to desert, drought,

the gray-beige hillsides where I live

spiky with thorn-brush, chaparral,

thirsty, armored survivors —

Here I stood among the moist

corn lilies greener than green:

I will give you living water to drink.

I looked at the living water,

its endless giving of itself,

and memory of younger self

pulsed in me — my onward will.

If it were the fertile north,

this mountain stream would

grow to a great river —

not perish in the desert,

the monotonous miles

in the rain shadow of the Sierra.

And then I thought: They also serve

who perish in the desert.

~ Oriana

*

LIVING WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER

~ Who could live with Isaac Bashevis Singer? The sexual escapades of the most successful Yiddish writer in America — and the one whom most Yiddish literati loved to hate — were public knowledge, in large part because he himself built his reputation as a Casanova in his own fiction, where he was chased into the bedroom by women young and old. His oeuvre might be described as “sex and the shtetl.”

Still, Singer was a married man. In Warsaw, before immigrating to the United States, he had a child out of wedlock — Israel Zamir, Singer’s only son — with one of his mistresses, Runia Shapira, a rabbi’s daughter. She was a Communist expelled from the Soviet Union for her Zionist sympathies. In his 1995 memoir, “A Journey to My Father, Isaac Bashevis Singer,” Zamir recounts how he and his mother ended up in Palestine. But since Singer and Runia separated when Zamir (born in 1929) was little, the report is almost totally deprived of a domestic portrait.

For Singer as homo domesticus, I needed the views of his wife, Alma Haimann, whom I’ll refer to by her first name hereafter. I had read in a 1970s article from The Jewish Exponent that Alma had been at work on an autobiography. “I’m about as far as the first 100 pages,” she told the Philadelphia newspaper. I was also aware, from Paul Kresh’s 1979 biography, “The Magician of West 86th Street,” that Singer didn’t think his wife would ever finish the manuscript. But was there such a manuscript?

Happily, when I last visited Singer’s archives at the Ransom Center, in Austin, Texas, I located the manuscript. Unhappily, it is far less than Alma had promised — not only in length (I came across 13 pages, a number of them only a few lines long,) but also in content. The first page has a title penciled in capital letters: “What Life Is Like With a Writer.”

The material is unformed, the style is clumsy; the scenes are poorly narrated. Of course, it is unfair to depict Alma as a failed writer, for she never aspired to be a writer. Neither is this manuscript a finished product. Yet Alma on occasion did present herself as an author. She wrote at least one short story, which she sent out to magazines. An editor gave her an encouraging response, but asked her to change the ending. Alma never followed up, and dropped the endeavor altogether.

She and Singer met in the Catskills, at a farm village named Mountaindale. Although in the manuscript Alma is elusive about dates, it is known that the encounter took place in 1937. The two were refugees of what Singer’s older brother, Israel Joshua, by then already the successful novelist I.J. Singer, would soon describe as “a world that is no more.” And the two were married to other spouses. Alma and her husband, Walter Wasserman, along with their two children, Klaus and Inga, had escaped from Germany the previous year and come to America, settling in the Inwood section of Manhattan. As for Isaac — as Alma always called him — he arrived in 1935. She portrays their encounters as romantic, although she appears to have been perfectly aware of his reputation.

Alma doesn’t explore the cultural differences that separated them. She was an upper-class German Jew born in Munich, whereas Singer was from Leoncin, a small Polish village northeast of Warsaw. In 1904, when Singer was born, Leoncin was part of the Russian Empire. In Alma’s milieu, Yiddish was a symbol of low caste. Her father had been a textile businessman and her grandfather had been a Handelrichter, a judge specializing in commercial cases. Although Wasserman, her first husband, was nowhere near as rich in America as he had been in Germany, he was certainly far wealthier than Singer, who was known as an impecunious journalist.

After her divorce from Wasserman and subsequent marriage to Singer, Alma worked as a seamstress. She then became a buyer for a Brooklyn clothing firm. From 1955 until the store closed, in 1963, she worked at Saks 34th Street, and then, until retirement, at Lord & Taylor. On occasion she would accompany Singer to his lectures. They also traveled together to Europe, especially England and France. The purpose of one of those trips was for Alma to show Singer the places in Switzerland where she and her parents had stayed before the war. When she returned to America, she felt ecstatic. In the manuscript, she recollects standing on Broadway, looking in wonder at a fruit store and grocery, admiring their abundance.

Alma writes about Israel Joshua Singer admiringly. She talks about writers Aaron Zeitlin and Shaye Trunk, and about Trunk’s wife, Hanna, who she says came over frequently for tea and cake. She paints poet Kadya Molodowsky as pale and dark-haired with trouble keeping her eyes open. And she recounts, in some length, her husband’s feud with Ab Cahan, longtime editor of the Forverts. The episode that captures her imagination was the newspaper’s promise to publish Singer’s novel “The Family Moskat” in installments. After Cahan viewed the first few installments as disappointing, he stopped serialization, according to Alma. In the ensuing fight, the Forward Association sided with Singer, which, according to Alma, forced “a somewhat senile” Cahan “to resign or reassign himself.”

The description of the incident is only partially true. In serialized form, the novel began publication in 1945. By then an aged Cahan was indeed ill. But it is implausible that the altercation surrounding “The Family Moskat” led to the editor’s demise. Incidentally, not only did the Forverts release the whole narrative, but Singer also went on to contribute numerous pieces to the Yiddish daily.

What kind of inner, private life did Alma have? Did she tire of years of cooking, cleaning, ironing and sewing for Singer? Was it difficult to be the wife of a public person? How did she cope with his escapades? About these the manuscript remains silent. After all, Alma belonged to a social class where women weren’t encouraged to explore such details. In an interview, she does represent the younger Singer as easy-going and says how much he changed over time. But she ascribes those changes to how much people wanted from him and not the other way around.

Sadly, nothing in Alma’s narrative hints at the emotional turmoil Singer left in his wake, although in the 1970s she told Kresh that abandoning the Wasserman family left such a sour taste in her mouth that she convinced herself it was better to stay forever with Singer despite his infidelities than to cause another emotional uproar. By most accounts, the lingering effects of her divorce made for bad blood toward Singer among Alma’s children and their extended family.

Alma recounts her relationship with Singer as one of endurance. Her first two lines are: “When I told my friends and relatives that I intended to marry Isaac Singer, they all protested violently that it would not last more than a few weeks, and that the whole thing was a mistake. So far it has lasted for almost forty years, and alt hough it was sometimes stormy, it nevertheless is a record.” Yes, she says it’s a record. The word “love” is nowhere to be found.

Singer’s domestic side is thorny. The Singers kept a Hispanic maid, and Dvora Menashe (later Telushkin), who was Singer’s assistant in his late years — indeed she wrote a memoir, “Master of Dreams” [1997], recounting that time — told me about her. So did Janet Hadda, who wrote the biography “Isaac Bashevis Singer: A Life” (1997). Hadda even provided me with an address, but my letters went unanswered. Lester Goran, who co-taught with Singer at the University of Miami and wrote a memoir about their friendship, “The Bright Streets of Surfside” (1994), couldn’t help me, either.

In the end, as Singer suffered from dementia, his relationships with Goran, Menashe and perhaps even Alma soured. The effects lingered unpleasantly even after his death, and as a consequence it’s hard to track the sirvienta. We don’t even know her name or nationality for certain. The idea of a Spanish-speaking maid as an integral part of Singer’s household is ripe not only for biographical scrutiny, but also for fictional development.

All this to say that the Yiddish writer’s other women — not the sexy but the stolid, those who accompanied him at home for better or worse, for richer or poorer, in sickness and in health — are crucial to the understanding of how he looked at the world. Alma was his anchor. Despite his betrayals, he always returned to her. Her silence, her resignation, might be disheartening to modern sensibilities. Yet she grounded him, and not only as an artist.

https://forward.com/culture/155296/living-with-isaac-bashevis-singer/

*

“IN ART, A TRUTH WHICH IS BORING IS NOT TRUE”

Singer and his Yiddish readers shared the uncanny experience of being the last bearers of a disappearing culture. For Jewish and non-Jewish readers who encountered him in translation, however, those common religious, political, and personal reference points were obscured. To that larger public, Singer appeared not as a participant in a broader Yiddish culture but as a synecdoche for Yiddish as such, perhaps even a medium with the power to resurrect it. When he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978, the Swedish Academy observed that the world of Eastern European Jewry “has now been laid waste by the most violent of all the disasters that have overtaken the Jews and other people in Poland. It has been rooted out and reduced to dust. But it comes alive in Singer’s writings.”

Singer’s task was to speak on behalf of Yiddish literature and of literature itself. Readers who think of him as a folk writer, specializing in tales of shtetls and dybbuks, will be surprised by the cosmopolitan breadth of his literary references and his engagement with contemporary cultural debates. In “Journalism and Literature,” for instance, published in The Forward in 1965—the year before Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood helped invent the “nonfiction novel”— Singer wrote approvingly of the convergence of the genres, citing Chekhov, Maupassant, and Poe as literary artists who were also practicing journalists.

Singer’s own lifelong identity as a newspaperman informed his thinking about literature, especially his suspicion of the pretentious and the abstract. “No matter how deep a literary work may be, if it bores the reader, it is worthless,” he declared. The job of the novelist isn’t “to analyze or to probe,” but to report something new about the world—“some sort of revelation, a fresh approach, a different mood, a new form.” As he put it in the essay “Who Needs Literature?,” writers “are entertainers in the highest sense of the word. They can only touch those truths which evoke interest, amusement, tension…. In art, a truth which is boring is not true.”

https://www.thenation.com/article/culture/isaac-bashevis-singer-old-truth-journalism/

People often ask me, “Why do you write in a dying language?” […] Firstly, I like to write ghost stories and nothing fits a ghost better than a dying language. The more dead the language, the more alive the ghost. Ghosts love Yiddish and as far as I know, they all speak it.

Secondly, not only do I believe in ghosts, but also in resurrection. I believe that the Messiah will come soon and millions of Yiddish speaking corpses will rise from their graves. Their first question will be: “Is there any new Yiddish book to read?”

~ Isaac Bashevis Singer's speech at the Nobel Banquet, 10 December 1978

*

TED HUGHES ON THE GENIUS OF ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER

Vision seems to be the right word for what Singer is conveying. The most important fact about him, that determines the basic strategy by which he deals with his subject, is that his imagination is poetic, and tends toward symbolic situations. Cool, analytical qualities are heavily present in everything he does, but organically subdued to a grasp that is finally visionary and redemptive.

Without the genius, he might well have disintegrated as he evidently saw others disintegrate—between a nostalgic dream of ritual Hasidic piety on the one hand and cosmic dead-end despair on the other. But his creative demon (again, demon seems to be the right word) works deeper than either of these two extremes. It is what involves him so vehemently with both.

It involves him with both because this demon is ultimately the voice of his nature, which requires at all costs satisfaction in life, full inheritance of its natural joy. It is what suffers the impossible problem and dreams up the supernormal solution. It is what in most men stares dumbly through the bars. At bottom it is amoral, as interested in destruction as in creation, but being in Singer’s case an intelligent spirit, it has gradually determined a calibration of degrees between good and evil, in discovering which activities embroil it in misery, pain, and emptiness, and conjure into itself cruel powers, and which ones concentrate it towards bliss, the fullest possession of its happiest energy.

Singer’s writings are the account of this demon’s re-education through decades that have been—particularly for the Jews—a terrible school. They put the question: “How shall man live most truly as a human being?” from the center of gravity of human nature, not from any temporary civic center or speculative metaphysics or far-out neurotic bewilderment. And out of the pain and wisdom of Jewish history and tradition they answer it. His work is not discursive, or even primarily documentary, but revelation—and we are forced to respect his findings because it so happens that he has the authority and power to force us to do so. ~

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1965/04/22/the-genius-of-isaac-bashevis-singer/

A Dissenting Voice. Chaim Grade was another Yiddish writer, Singer's contemporary. Funny how this seems colorful enough to have been written by Singer himself.

"Every human being, if he is a real, sensitive human being, feels quite isolated. It is only the people with very little individuality who always feel that they belong. Since I believe that the purpose of literature is to stress individuality, I also, unwillingly, stress human lonesomeness.” ~ I. B. Singer

*

ON CHANCE AND HISTORY

“Chance has always been a huge factor in how history plays out. If you don’t believe that, just ask the dinosaurs.”

~ Proverbial

Chance has always been a huge factor in how history plays out. If you don’t believe that, just ask the dinosaurs. But chance, of course, can affect history in innumerable ways besides the odd six-mile-wide meteoroid coming in from outer space.

Here are some of the ways chance has worked on history.

England is separated from the European continent by a mere twenty-one nautical miles of open water. But that fact has had enormous historical consequences. While it was close enough to Europe for considerable interaction, England was, after the Normans, largely safe from foreign invasion behind its watery walls. So the country could develop as a low-tax economy where the king largely left local matters to local landowners. With such a governing system made possible by geography, England proved fertile soil in which the modern concept of liberty could begin to grow, beginning with Magna Carta in 1215.

[. . . the rest is behind a pay wall, but influence of geographical location on history is already made clear thru a powerful example.]

https://newcriterion.com/article/chance-history/

*

THE ORIGIIN OF THE GAY RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN WW1

In the winter of 1915, a German soldier died in a field hospital in Russia. We don’t know his name, but he helped revolutionize the way people advocated for gay rights.

German infantrymen aim machine guns from a trench near the Vistula River in 1916.

One of World War I’s most enduring legacies is largely forgotten: It sparked the modern gay rights movement.

Gay soldiers who survived the bloodletting returned home convinced their governments owed them something – full citizenship. Especially in Germany, where gay rights already had a tenuous footing, they formed new organizations to advocate in public for their rights.

Though the movement that called itself “homosexual emancipation” began in the 19th century, my research and that of historian Jason Crouthamel shows that the war turned the 19th-century movement into gay rights as we know it today.

A Death in Russia

In the winter of 1915, a German soldier died in a field hospital in Russia. The soldier, whose name is missing from the historical record, had been hit in the lower body by shrapnel when his trench came under bombardment. Four of his comrades risked their lives to carry him to the rear. There, he lay for weeks, wracked by pain in the mangled leg and desperately thirsty. But what troubled him most was loneliness. He sent letters to his boyfriend whenever he could manage it.

“I crave a decent mouthful of fresh water, of which there isn’t any here,” he wrote in his final letter. “There is absolutely nothing to read; please, do send newspapers. But above all, write very soon.”

This soldier, who had to keep his relationship hidden from those around him, was just one of the approximately two million German men killed in World War I. His suffering is not unlike what many others experienced. What his loved ones made of that suffering, however, was different, and had enormous consequences.

His boyfriend, identified in surviving documents only as “S.,” watched the man he loved go off to serve in a war that he did not fully endorse, only to die alone and in pain as S. sat helplessly by hundreds of miles away. S. told their story in a letter to the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, which published it in April 1916.

The Scientific Humanitarian Committee was then the world’s leading homosexual emancipation group, boasting a membership of about 100 people. The soldier’s story took a cruel twist at its very end: S.’s loving replies were lost in the chaos of the war and never reached the soldier.

“He died without any contact from me,” S. wrote.

Demanding the Rights of Citizens

After the war, many believed the slaughter had been for nothing. But S. saw a lesson in his partner’s suffering and death.

“He has lost his bright life … for the Fatherland,” wrote S. That Fatherland had a law on the books that banned sex between men. But the sodomy law was just the tip of the iceberg: S. and men like him generally could not reveal their love relationships in public, or even to family members. Homosexuality meant the loss of one’s job, social ostracism, the risk of blackmail and perhaps criminal prosecution.

S. called it “deplorable” that “good citizens,” soldiers willing to die for their country, had to endure the status of “pariahs.” “People who are by nature orientated toward the same sex … do their duty,” he wrote. “It is finally time that the state treated them like they treat the state.”

A New Phase of Gay Rights

Many veterans agreed with S. When the war ended, they took action. They formed new, larger groups, including one called the League for Human Rights that drew 100,000 members.

In addition, the rhetoric of gay rights changed. The prewar movement had focused on using science to prove that homosexuality was natural. But people like S., people who had made tremendous sacrifices in the name of citizenship, now insisted that their government had an obligation to them regardless of what biology might say about their sexuality.

They left science behind. They went directly to a set of demands that characterizes gay rights to this day – that gay people are upstanding citizens and deserve to have their rights respected. “The state must recognize the full citizenship rights of inverts,” or homosexuals, an activist wrote in the year after the war. He demanded not just the repeal of the sodomy law, but the opening of government jobs to known homosexuals – a radical idea at the time, and one that would remain far out of reach for many decades.

Respectable Citizens

Ideas of citizenship led activists to emphasize what historians call “respectability.”

Respectability consisted of one’s prestige as a correctly behaving, middle-class person, in contrast to supposedly disreputable people such as prostitutes. Throughout the 20th century, gay rights groups struggled for the right to serve openly in the military, a hallmark of respectability. With some exceptions, they shied away from radical calls to utterly remake society’s rules about sex and gender. They instead emphasized what good citizens they were.

In 1929, a speaker for the League for Human Rights told an audience at a dance hall, “we do not ask for equal rights, we demand equal rights!” It was, ironically, the ghastly violence and horrible human toll of the World War I that first inspired such assertive calls, calls that characterized gay rights movements around the world in the 20th century.

It would take nearly a century for these activists to achieve one of their central goals – the repeal of sodomy laws. Germany enjoyed a 14-year period of democracy after World War I, but the Nazis came to power in 1933 and used the sodomy law to murder thousands of men. A version of the law remained in force until the 1990s. The United States struck down its sodomy laws only in 2003. ~ Laurie Marhoefer

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-forgotten-origins-of-the-modern-gay-rights-movement-in-wwi?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

*

WHO WAS WORSE, LENIN OR STALIN?

Both were terrible.

Lenin took over the country by force, and robbed it clean. The treasury was spent on paying the mercenaries, and the German Communists for their failed revolution attempt in 1918. The revolution stopped most of the production, as it turned out that to steal is more profitable than to make, and the whole country turned into a bunch of roving armed gangs, fighting one another, frequently with no political agenda — just the resources, as it often happens during civil wars. The ruble tumbled into hyperinflation, it was denominated by 100000 by 1922, as compared to 1918.

The number of people killed in civil war may look small compared to Stalin’s purges. That should not deceive anyone, as Lenin only had 7 years in power, compared to Stalin’s 30.

The Kronstadt mutiny of 1921, one of the Civil War episodes

In addition, during Lenin’s term, anyone could officially be killed on suspicion of counterrevolutionary activity. Yes, just that, suspicion was a reason solid enough for execution on the spot.

Stalin continued the same reign of terror. But he was creative in his maniacal drive to kill. Contrary to the media perception, the terror machine never stopped. There was nothing special about 1937 for a common USSR citizen — they might have been arrested and executed in 1927, 1934, or 1947 (random numbers chosen), or to get starved to death in 1923, 1932–33 or 1947-48.

The only reason they speak about this year is that Stalin became emboldened enough to purge those who previously were believed to be untouchables: the Lenin guard — those who made the revolution together with Lenin (party leaders such as Bukharin) or fought the Civil war (generals Tukhachevsky and Yakir).

The Stalinists frequently say that “Stalin has accepted Russia with a wooden plow, and left it with a nuclear bomb.” And they even misattribute this quote to Winston Churchill. The truth is that a Russian peasant still had the same wooden plow, having to work almost round the clock, having no pay, no vacation and no benefits, for the state to have the nuclear bomb. Not to mention the millions deliberately starved to death in order to sell their food to the West and buy the military capable manufacturing equipment in the 1930s. ~ Timofey Vorobyov, Quora

IN SPITE OF EARTHQUAKES, WE SHOULD BE GRATEFUL FOR PLATE TECTONICS

The outer layer of our planet is a jigsaw puzzle of massive plates that shift, slide, and collide—and make Earth habitable.

I imagine that exceedingly few people like to be unexpectedly jostled about by an earthquake. Whether you’re in an area known to be frequented by modestly powerful temblors, or whether you’re chilling out somewhere that isn’t especially prone to them—say, New York or New Jersey—it can be a disquieting experience. Earthquakes are also famously destructive: If they strike in just the right place, with sufficient shaking, they can ruin villages, towns, even cities and, should they trigger a tsunami, entire coastlines.

But Earth without earthquakes wouldn’t be, well, Earth. It wouldn’t be bursting with biology, nor would it have a clement atmosphere that supports a wealth of lifeforms. A lack of earthquakes would signify that the planet is geologically dead, or at the very least comatose—and things don’t end well for worlds whose innards are anything less than tumultuous.

Before I explain why, it’s important to note that quakes happen on other worlds. Wisely, scientists don’t call them earthquakes. Moonquakes happen, as do marsquakes; the former can cause the lunar surface to quiver for several minutes, while the latter are less dramatic, low-pitch grumbles. As these are the only two worlds (other than Earth) that have been studied with seismometers, we can only speculate about temblors on other planets and moons. But there are almost certainly quakes on hypervolcanic Venus too, as well as on the rime-covered surfaces of a multitude of icy moons, from Jupiter’s frigid Europa to Saturn’s frosted Enceladus.

All these celestial objects are geologically active to varying degrees—and, broadly speaking, that activity is driven by heat trapped within a world. That heat comes about in various ways. It can be generated by the radioactive decay of unstable elements, for example, or the gravitational pull of a massive planet on a wobbling moon can tear up and melt that satellite’s rocky innards—a mechanism known as tidal heating. Some planets and moons even retain a decent amount of heat from their fiery formation eons ago.

An interferogram of Kathmandu shows the amount of land deformation after a 2015 quake: Each color represents about an inch of deformation. In areas that appear speckled, including the large area on the right, the ground deformed more than three feet.

The Moon, being rather small, doesn’t have much heat left in its deep interior. But because the Moon is so cold, it’s shrinking over time, which causes ancient faults to slip and generate shaking. Mars is a bit toastier on the inside, and it probably has a molten core that might be able to churn about a fair bit—enough, at least, to knock the crust about and cause infrequent quivering. And Europa and Enceladus have something more akin to ice quakes: largely thanks to tidal heating mechanisms, both possess liquid water oceans that push and pull at their icy crusts, causing fracturing.

Earth, however, is unique in the solar system—at least as far as planetary scientists know. Its earthquakes have a variety of triggers, but they all ultimately stem from a process known as plate tectonics. Unlike every other relatively solid planet or moon we have observed in our solar system, the upper part of Earth’s geologic layer cake is full of deep schisms. These fractures bound individual tectonic plates—large chunks of crust and the more malleable upper mantle just below it—that constantly shift and jiggle about.

Sometimes these plates move away from one another. Sometimes they dive under or over each other. And sometimes they collide. There is much that scientists don’t yet understand about this process, but what they definitely do know is that, thanks to the churning deeper mantle, these plates go on both destructive and constructive voyages. They make mountain ranges and ocean basins, chains of explosive volcanoes and supercontinents, over and over again.

Plate tectonics make Earth topographically interesting, creating environments that worlds without this infernal jigsaw cannot hope to forge. But what’s crucial is that this process allows the planet to be what us surface dwellers would consider habitable. And that’s because plate tectonics acts as a global thermostat, without which Earth would turn positively apocalyptic.

Carbon dioxide, that most notorious of greenhouse gases, dissolves in bodies of water and gets locked up in carbon-bearing minerals. If those minerals are in the ocean, then they eventually get dragged down by one tectonic plate sliding beneath another at sites known as subduction zones. When this happens, that carbon spends millions of years imprisoned in the lower mantle until, one day far into the future, it reaches the surface again through volcanic eruptions. Water, which is also a potent greenhouse gas in vapor form, gets buried and unleashed in a similar manner.

Thanks to a variety of forcing mechanisms, Earth’s climate has fluctuated wildly over geologic time. As our planet orbits the Sun, it gradually shifts back and forth a little in a few different ways, orienting the planet in such a way that it receives more or less solar radiation—and which, in turn, can cook or chill the world for a spell. A massive asteroid impact can blanket the atmosphere in dust and aerosols that reflect sunlight, temporarily refrigerating the planet.

Extremely rare but astoundingly epic volcanic eruptions that can last for hundreds of thousands of years can pump greenhouse gases into the sky, triggering warming spikes. And a certain species can, through the burning of fossil fuels, add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere at unprecedented speeds, ushering in chaotic climate change.

Nevertheless, on geologic timescales, plate tectonics ensures that Earth won’t grow so catastrophically hot that its surface becomes unlivable. Without plate tectonics, Earth would turn into Venus. And no planet aspires to be more like Venus.

Planetary scientists suspect that, billions of years ago, Venus had a significant amount of water on its surface in some form, perhaps as several seas or an ocean. It would have been an uncomfortably hot world by human standards, but not lethally so to various forms of life as we know it. And Venus also may have had plate tectonics not dissimilar from the sort that Earth has now.

Venus today is an arid wasteland—but in the deep past, it may have been more similar to Earth thanks to plate tectonics not unlike our own.

But a series of volcanic eruptions, lasting many millennia, expelled far too much carbon dioxide and may have broken the planet’s thermostat. Such a sudden (on geologic timescales, anyway) injection of greenhouse gases would have caused the temperature to rise too high, too quickly.

Those seas and oceans would have started boiling off into a gas, creating a lot of water vapor. And all that gaseous water would have caused temperatures to rise even faster. Without sufficient liquid water left on the surface to absorb that carbon dioxide, it would have lingered in the atmosphere.

Subducting tectonic plates normally are able to bury lots of carbon but, without the water crucial to that carbon capture, the plates cannot bend and break properly. The entire process may have come to a halt. And if that happened, Venus would have lost its thermostat, causing its temperature to jump by hundreds of degrees and transforming the surface into a baked, arid wasteland.

That’s how the leading theory goes, anyway. Nobody is quite sure what Venus was once like, nor what triggered its runaway greenhouse effect. And, had it not been for—among other things—our world’s endlessly shifting tectonic plates, Earth could have shared the same grim fate as Venus.

Yes, those tectonic plates buckle and stretch, slip and slide, creating faults that jolt and snap, which generate earthquakes—sometimes devastatingly so. But these tremors are the vital sign of a planet with a beating geologic heart, an orb with a transmogrifying face. They are, for better or worse, one of the prices we pay for having a planet that sustains life as best as it can. They may rarely be something to be thankful for, but they do serve as a reminder that things could be a whole lot worse. ~

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/plate-tectonics-make-earth-habitable?utm_source=pocket-newtab-en-us

*

HOMO SAPIENS CAUSED THE EXTINCTION OF NEANDERTHALS BY INTRODUCING NEW DISEASES

Less than a decade ago, the American anthropologist James C Scott described infectious diseases as the “loudest silence” in the prehistoric archaeological record. Epidemics must have devastated human societies in the distant past and changed the course of history, but, Scott lamented, the artefacts left behind reveal nothing about them.

Over the last few years, the silence has been shattered by pioneering research that analyses microbial DNA extracted from very old human skeletons. The latest example of this is a groundbreaking study that identified three viruses in 50,000-year-old Neanderthal bones. These pathogens still afflict modern humans: adenovirus, herpesvirus and papillomavirus cause the common cold, cold sores, and genital warts and cancer, respectively. The discovery may help us resolve the greatest mystery of the Palaeolithic era: what caused the extinction of Neanderthals.

Recent advances in the technology used to extract and analyze ancient DNA has given us incredible insights into the ancient world. With the exception of time travel, it is difficult to imagine a technology capable of so profoundly changing our understanding of prehistory.

The first major developments in the ancient DNA revolution came from human genetic material. A study that analyzed DNA from burial sites across Britain revealed that Stonehenge was built by dark-haired, olive-skinned farmers originating from modern-day Turkey, and that their descendants died out a few centuries after the megaliths were raised.

When a team led by Nobel laureate Svante Pääbo sequenced the Neanderthal genome, they realized that modern humans with European, Asian or Native American ancestry inherited about 2% of their genes from Neanderthals. Then, during the pandemic, it became apparent that several Neanderthal gene variants that are particularly common among South Asians influenced the immune response to novel coronavirus, making carriers much more likely to get very sick and die. It is wild to think that inter-species trysts that occurred tens of thousands of years ago impact the health of people alive today.

When scientists extract human DNA from human skeletons, they also pick up traces of the microbes that were in the bloodstream at the time of death. Some of the most interesting research in this field focuses on Yersinia pestis, the bacteria responsible for the plague. Not long ago, the oldest evidence of Y pestis came from the mid-14th century, when the Black Death killed around 60% of Europe’s population.

We now know that the plague goes back much further. Between 4,000 and 5,000 years ago it was widespread across Europe and Asia, including – as a recent study showed – in Somerset and Cumbria. Around this time, northwest Europe’s population fell by as much as 60%. It is likely that a “Neolithic black death” contributed to the demographic crash, which coincided with the disappearance from Britain of the farmers who built Stonehenge and the arrival of another group that contributes more than any other to the DNA of modern Britain.

Ancient microbial DNA also offers tantalizing insights into the private lives of our distant ancestors.

Scientists have found Methanobrevibacter oralis, a bacteria-like organism associated with gum disease in modern humans, in the calcified plaque on 50,000-year-old Neanderthal teeth. By comparing the prehistoric strain with the contemporary one, researchers calculated that their last common ancestor lived about 120,000 years ago. Since this is several hundred millennia after Neanderthals and Homo sapiens diverged, the germ must have been transmitted between the species. The most likely way this happened was through inter-species smooching.

It is technically challenging to extract and analyze viral DNA from ancient bones. As viruses are much smaller than bacteria, they contain less genetic material, and because they are less robust, it degrades more quickly. This makes the recent news that scientists have sequenced 50,000-year-old viral DNA so exciting.

While the discovery that Neanderthals were infected by adenovirus, herpesvirus and papillomavirus will not, on its own, change our understanding of the distant past, it hints at a solution to the great mystery of the Palaeolithic era.

Until about 70,000 years ago, Homo sapiens lived in Africa while Neanderthals inhabited western Eurasia. Then everything changed. Our ancestors migrated northwards, spreading quickly across much of the world. Not long after, Neanderthals disappeared.

Since the late 19th century, when the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel proposed calling Neanderthals Homo stupidus to distinguish them from Homo sapiens (wise human), the dominant explanation for this transformation is that our ancestors outcompeted other human species using their superior cognitive abilities. This argument has become increasingly untenable, however, thanks to mounting evidence that Neanderthals were capable of all sorts of sophisticated behaviors, including burying their dead, painting cave walls, using medicinal plants and seafaring between Mediterranean islands.

The discovery of the 50,000-year-old viruses points to an alternative explanation for Neanderthals’ demise: deadly infectious diseases carried by Homo sapiens. Having been separated for more than half a million years, the two species would have evolved immunity to different infectious diseases. When they encountered one another during Homo sapiens’ migration out of Africa, pathogens that caused innocuous symptoms in one species would have been deadly to the other, and vice versa.

The reason that Homo sapiens survived while Neanderthals disappeared is simple. Our ancestors lived closer to the equator. As more of the sun’s energy reaches the Earth, plant life is more abundant there. This provides a habitat for more dense and varied animal life, which in turn supports more microbes that are capable of jumping the species barrier and infecting humans. Consequently, Palaeolithic Homo sapiens would have carried more deadly pathogens than Neanderthals.

The ancient DNA revolution is not only transforming our understanding of prehistory – it also has important implications for the present. If infectious diseases played such a critical role in Neanderthals’ disappearance and Homo sapiens’ rise to world domination, then pathogens are far more powerful than we ever realized. Our ancestors 50,000 years ago had germs on their side, but we might not be so lucky in the future. ~

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/may/30/50000-year-old-herpes-virus-humans-dna-homo-sapiens-neanderthals

Mary: THE POWER OF MICROBES: MEASLES

The power of microbes cannot be underestimated in terms of their effects on our history. The devastations of plague on the European population certainly created the conditions for the transition from feudal society to the kind of society based on transactions of labor for hire rather than serf labor tied to the land and the lord, the rise of a powerful merchant class, and a cash economy.

The great genocide of the native American population was effectively carried out not with guns and armies, though those certainly kept it going, but with the pathogens Europeans brought with them, that indigenous people had no experience with and thus no defense against. Smallpox, notably, burned through the tribes like a wildfire that kept killing en masse well into the 19th century.

Of course we don't know for sure, but I believe it is reasonable to think Sapiens pathogens could have overwhelmed Neanderthal immune systems...herpes viruses can do more than cause cold sores...they can be virulent enough to cause blindness or to kill with encephalitis in the immuno-compromised...and, in organisms that had no prior experience, no defenses, they could have been extremely deadly.

Oriana: THE POWER OF MICROBES: SYPHILIS

So true, both ways. Syphilis became rampant in Europe in no time after that history-changing voyage, reaching epidemic levels already by 1500. “ The most widely accepted theory is that the venereal form of the disease arrived on the shores of Europe along with Christopher Columbus's crew, when they returned in 1493 from a journey to the New World.” https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/the-syphilis-enigma-background/7042/

*

JUNG ON THE FIVE PILLARS OF HAPPINESS

In

1960, journalist Gordon Young asked Jung, "What do you consider to be

more or less basic factors making for happiness in the human mind?" Jung

answered with five elements:

1. Good physical and mental health.

2. Good personal and intimate relationships, such as those of marriage, the family, and friendships.

3. The faculty for perceiving beauty in art and nature.

4. Reasonable standards of living and satisfactory work.

5. A philosophic or religious point of view capable of coping successfully with the vicissitudes of life.

Jung,

always mindful of paradox, added, “All factors which are generally

assumed to make for happiness can, under certain circumstances, produce

the contrary. No matter how ideal your situation may be, it does not

necessarily guarantee happiness.”

I did disagree strongly with Jung on one point. He said, “The more you deliberately seek happiness the more sure you are not to find it." I know, Carl Jung vs. Gretchen Rubin, who is the authority? But though many great minds, such as John Stuart Mill, make the same point as Jung, I don't agree.

For me, at least, the more mindful I am about happiness, the happier I become. Take Jung's five factors. By deliberately seeking to strengthen those elements of my life, I make myself happier.

What

do you think of Jung's list? Would you add anything else, or

characterize any element differently? And do you think it's helpful to

think about happiness directly, or not?

Oriana:

I

prefer Freud’s succinct answer about the most important things in life:

Love and work. And I suspect that by “satisfactory work” Jung meant vocation.

I’m

tempted to reply that if you have love and work (the kind of work you

mostly love, that is), it doesn’t matter all that much if you are poor

or sick. But having experienced both poverty and illness (a lot of

illness), I grudgingly nod to what Jung is saying about good health and

comfortable income. Sensitivity to beauty and maintaining communion with

beauty, yes. A life philosophy that helps you cope with adversity, yes.

A friend once said, “Religion is autobiographical.” So is one’s

life philosophy. Both are obviously influenced by culture, but personal

experience is critical. It’s a constant evolution, like everything

else in life.

When in doubt, I go back to what Freud said ("Love

and work"), since everything else follows. But another friend said: “I

seek peace. Everything else follows.” And I can see that too. The answer

is personal, autobiographical. Books on happiness? Typically useless,

though I like the ones that are written in a soothing style. There is such a thing as “comfort language,” just as there is stress-inducing language.

A message can be phrased either way, but is it really the same message?

Nietzsche: to improve one’s style is to improve one’s thinking.

Ravi Chandra, M.D., a San Francisco psychiatrist, proposed the following six elements of happiness:

1.unconditional self-acceptance, and self-love. Metta (lovingkindness) should first be extended to oneself, and then extended to others. Win or lose, succeed or "fail", your self worth should not based on external valuations, but rather on your basic existence as a person. Albert Ellis (proponent of Unconditional Self-Acceptance) remarked that even Hitler was acceptable as a human being; it's only his actions we deplore.

Where

Dale Carnegie urged the reader never to criticize others, Louise Hay says,

“Stop criticizing yourself!” Unconditional self-acceptance (acronym:

USA) is the foundation of happiness . . . Please read the rest here: http://oriana-poetry.blogspot.com/2012/04/falling-sandal-self-help-then-and-now.html

2. a sense of interdependence, and connectedness with others and even all life.

This breaks down our inherent sense of independence, which turns

pathologically into isolation, loneliness, and even devaluation of

others and over-valuation of self, as well as what Buddhists would call

mental poisons of greed, anger, jealousy, and ignorance, springing out

of a mistaken belief in a fixed, permanent self. Some people even call

interdependence their "higher power".

3. mindful awareness of thoughts and feelings, without identifying with them. Developing the "inner observer" allows us to cultivate an inner reservoir of calm with which to meet the world.

4. acceptance of change. Everything is impermanent, all things will transform.

5. an acceptance that life is difficult, and no one is free from adversity and pain. Knowing this allows us to cultivate wisdom, patience, forgiveness, compassion, equanimity and other healing emotions. I'm reminded of Stephen Hawking's statement that he became happier after developing his disability ("Life and the Cosmos, word by painstaking word").

6. a sense of meaning or purpose in life.

Certainly, setting goals and achieving them can give a sense of

accomplishment. But having a deeper sense of purpose gives a sense

of resilience and an ability to withstand the "squalls" and tempests

that are inevitable in life.

*

“Religions are not claims to knowledge, but ways of living with what cannot be known.” ~ John Gray

JMW Turner: Angel Standing in the Sun, 1846

Then I saw an angel standing in the sun, and he cried out in a loud voice to all the birds flying overhead, “Come, gather together for the great supper of God, so that you may eat the flesh of kings and commanders and mighty men, of horses and riders, of everyone slave and free, small and great.”… ~ Revelation 19:17

Oriana:

I've read that this "angel standing in the sun" is the Archangel Uriel. whose name means "the light of God," and who is the angel of wisdom.

*

LIVING ALONE: FOR SOME, THE AMERICAN DREAM

Not many of Jess Munday's San Francisco friends live alone. But Munday, a 29-year-old who works in tech marketing, was able to swing it.

It took living with her parents for a few months during the pandemic, during which time she saved some money. Then, she struck in January 2021 when, according to Zillow, rent prices in the city were the lowest they've been in the past five years.

She pays about $2,600 for a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco's Mission neighborhood and makes $175,000 annually. It's a deal compared with the median rent of about $2,900 for a one-bedroom apartment in San Francisco.

"I even know people who are a lot older than me who are living with roommates in San Francisco," Munday said. "I'm thankfully in a financial situation where I don't have to do that."

The 30-something American dream used to look a little like this: You're married, you have two or three kids, and you own your starter house (white picket fence optional).

But things have shifted. Millennials are getting married later, if at all. They're having kids later, if at all. And forget owning a sprawling suburban home.

That's helping establish a new millennial milestone for some: Ditching roommates, moving out from the family home, and landing on living alone.

Going solo as a younger worker has become increasingly popular in the past few decades, though it's still relatively uncommon in the US. Census data indicates that in the late 1960s and early 1970s, under 3% of Americans between 18 and 34 lived alone; by 2023, that number had tripled. Business Insider's analysis of American Community Survey microdata from IPUMS found that 10.5% of millennials lived alone in 2022.

"I personally like living alone. I can control the space, how I decorate," Munday said. "I do enjoy having space and being able to clean or leave it messy depending on my mood.”

The singles tax

Aria Velasquez, 32, lives alone in her one-bedroom apartment in Chicago, paying about $1,500 in rent and service fees. She was laid off from her journalism job earlier this year.

She said the biggest challenge is taking on the financial burden alone. Her partnered friends, on the other hand, get a break.

"Now that we're in our early to mid-30s, a lot of people are getting married or partnering up so they're moving in with their partners even if they're not married," Velasquez said. "They will cite living with someone to split the bills with as a benefit of moving in with someone.”

Zillow recently estimated that people living alone in one-bedroom rentals spent over $7,000 more annually on housing costs than people living with others — a difference often described as the singles tax.

Velasquez said that she loves living alone and that it has always been her goal. She values privacy and quiet and loves coming home to nothing but the "hum of the fridge." At the same time, she acknowledged that the cost of many items, including groceries, had risen, adding that there's "no discount for single-person shopping.”

"You buy a loaf of bread, but you may not eat the entire loaf in a short period of time because maybe you don't want a sandwich every day," Velasquez said.

Though she's able to rent on her own, buying her own place feels like a distant dream: "I view it the same way people think about winning the lottery.”

More millennials living with Mom and Dad

Erica Charles, 28, a publicist in Washington, DC, said that while she and many of her peers live alone, others had moved back in with family in recent years. She said she's considered it as well.

"I could save $700 a month," Charles said, adding that it could go toward saving for her graduate school tuition. "I'm thinking about how I can scale back a lot. I'm thinking about jobs that pay more and how to bring in more money through freelancing.”

Rick Fry, a senior researcher at Pew, said the share of 18- to 34-year-olds living in their families' homes has been slowly rising since 1971 "and particularly kind of picked up during the Great Recession," per Pew's research. As of 2023, he said, it was about 32%.

"If you look at the metro areas that have the highest median rents, those are the metro areas where you see the young adults most likely to be living with Mom and/or Dad," Fry said. Per BI's analysis of American Community Survey data via IPUMS, 16% of millennials lived with at least one parent as of 2022. (The data doesn't specify if that means they're living with their parents or if their parents are living with them.)

Charles said that before the pandemic, she liked living alone. "I thought it was a rite of passage into young adulthood," she said.

This year, Charles has been rethinking her living situation. Her lease is ending in June. She says she's been laid off three times since 2020. Because of finances, she's put plans to pursue a Ph.D. in media communications on hold, and she's not planning to have children anytime soon. She'd also like to buy a house in the next three years. Housing prices in Florida, where she's from, have increased significantly over the past five years.

She's thought about whether she wants to move in with her family or with a roommate. She's been cutting back on spending and has been doing more budgeting. She's even taken on part-time food-delivery and freelancing gigs.

"It's really a privilege to live alone," Charles said. "Now it's become a luxury.”

Subsidized solo living

Some lower-earning millennials are able to get assistance reaching the solo-living milestone — but it's not always easy.

Garak Clibborn, 39, a veteran in California, has been homeless before. He's also cycled through at least eight roommates while renting a room in a house and applying for housing assistance so he could live on his own. After waiting nearly a year, his name was called for a housing voucher, he said — and he was told he had 60 days to find a place before it expired.

Many apartments had yearslong waitlists, and others wouldn't accept vouchers, which is government rental assistance. After calling over 350 places, he finally found a spot. He's been living alone there since 2012. His rent just went up, to over $1,900. With his subsidy, he pays about $380 a month; he uses the money from his VA pension to help cover the cost.

"Even with a subsidy, it's extraordinarily difficult" to live alone, Clibborn said. He added that he still has to cover many other expenses on his own.

"If I run out of money, I'm screwed. I don't have anything to help me," he said.

Way behind in homeownership

Chaz Zimmer, a 28-year-old who sells cars at a Subaru dealership, has lived alone in his apartment in Waverly, New York, since February 2021. He pays $550 a month in rent. He tried to purchase a home last year, but interest rates made it expensive. He'd eventually like to move to a bigger place, but his rent is so cheap that it's hard to justify moving, he said.

An analysis of American Community Survey data published last year found that non-college-educated millennials were half as likely to own homes at 30 as non-college-educated baby boomers were at that age. It also found that 38% of college-educated millennials owned homes at 30, less than the 54% of college-educated boomers who owned a home at that age.

Tomasz Piskorski, a professor of real estate at Columbia Business School, said it's become more difficult to buy a home because of the increases in home prices and interest rates after 2022.

"For the millennial generation, it could take years to catch up in homeownership," Piskorski said.

Zimmer hasn't given up hope. "Some of it comes down to opportunity and timing," Zimmer said. He works on commission, so his salary has ranged from $62,000 to $79,000 in the last couple of years. He said he's "fortunate to have a pretty good job that makes a decent enough salary.”

Rent versus a mortgage

James Paniagua, 30, lives in Oakland, California. Throughout college, he lived at home and stayed there until right before the pandemic. He briefly lived in Los Angeles with a roommate, but the pandemic sent him back home.

"I have essentially been living at home for the majority of my twenties," he said. Last year, he decided to move up north for work and was lucky enough to find his own place in Oakland. Before making that move, a few financial pieces had to fall into place: He had to fix his credit score, and he needed to find a job that paid him enough to move out.

Today, he makes around $125,000; his 700-square-foot apartment with a parking spot costs him around $2,100 in monthly rent.

"Starting to pay rent was the biggest adjustment, which is obviously a huge payment adjustment, but I took the time to plan out that as much as possible and shift some things around to be able to live alone, but still live the lifestyle that I had had before," he said.

He's stopped making weekly mall trips and eats at home more regularly now. He said he likes to stay at home and wants to make his space as cozy as possible.

While he said he's getting a good deal for what he has, some older adults can't believe how much he's paying for rent, "they're shook.”

"It's more than some of my relatives' mortgages," Paniagua said.

The experience of living alone has evolved

For those who are able to buy, snagging a solo property is a pivotal life event, and may provide comfort amid the uncertainty of other traditional milestones.

After attending graduate school in London, Julia Mazur, now 30, moved back home with her parents for two years. She worked a tech job that paid a six-figure salary and offered a generous equity package, she said. At age 25, she saved up enough to buy her own condo in Los Angeles.

During the pandemic, she refinanced her mortgage and got a lower rate; she said her monthly costs totaled about $3,000. Now she's swapping homes with a couple in Austin who have a similarly priced mortgage.

For her, living alone is empowering. She said she thinks some millennials are finding their person and settling down while others, including her, are finding fulfillment in different aspects of their lives.

"For me, I like the ability to move around and to travel, to get to experience what living on my own is like and the responsibilities that come with it. I feel very fulfilled by that," she said. "And I also think that with living alone, there does come a need to connect with humans in real life. And so I kind of make myself go and do things to try and connect with people, go to tennis classes, go sit up alone at bars, go to meetups and friend dates.”

DePaulo said the experience of living alone has changed significantly in the past few years. She's found that people living alone are more likely to be connected to more diverse people — and more people overall — and engage more with civic life and community institutions.

Living alone is worth it for many, despite the challenges

Kathy Pierre, 31, pays $1,280 a month in base rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Charlotte, North Carolina. When she moved to Charlotte, she didn't know anyone there and didn't want to take risks with living with a stranger after past experiences with roommates. "I needed to make myself afford it," she said.

At the same time, she says if she lived with family or a roommate, she'd be able to save money and get closer to buying a home. All the bills, including food, utilities, and rent, are her own when living alone. What's more, it can be easy not to talk to another human in person while working from home.

“It's just very lovely to be able to live on my own and have my own space,” Pierre said. “I don't have to negotiate with other people about what happens here. I think that is really awesome. I say jokingly, but not jokingly, I would move out of Charlotte before I look for a roommate.”

https://www.businessinsider.com/millennials-live-alone-status-symbol-rents-housing-homeownership-expensive-2024-5

Mary:

I think we are in a serious housing crisis now, with home ownership increasingly out of reach, and apartment rents higher than mortgage payments were for past generations. People have to work multiple jobs, live with room mates, live with family...or become homeless. There may be a housing shortage...but there definitely is an affordable housing shortage. Some are opting to live in RVs in parks like trailer parks as an affordable solution.

This scarcity of affordable choices will inevitably lead to an increase in the homeless population...an increase I believe we are already seeing. This does not bode well for us as a civilization.

*

STEAM LOOPS VS DOOM LOOPS

How an underground maze of abandoned pipes can save America's cities

Tucked beneath a 48-story San Francisco skyscraper, at the far end of the parking lot on the first subbasement level, is a door with a keypad lock. An unimposing sign reads "Utility Meter Room." Behind the door is a tangled clot of pipes: yellow, blue, and orange, each one as wide as a 100-pound barbell plate. The pipes — along with thousands more just like them, winding their way under more than 600 American cities, campuses, hospitals, and airports — are more than a blast from our industrial past. They're a steampunk vision of the future.

I've come to 345 California Center, a postmodern hexagon that towers over San Francisco's financial district, to get a look at the hottest new idea for how to break the urban doom loop — the post-pandemic, remote-work apocalypse that is hollowing out America's cities. And when I say "hottest," I don't mean it metaphorically. It's like a sauna down here. Because the Utility Meter Room doesn't run on a self-contained, industrial-sized boiler, like most big buildings.

Instead, it's drawing a feed of blistering, high-pressure, vaporized water from a century-old loop of steam pipes that runs beneath the city's streets. The steam loops are a relic of the 19th century, as forgotten as the pneumatic tubes that used to shoot mail all over American cities. But unlike the pneumatic tubes, the steam loops are still there — and they can provide enough heat to keep a building like 345 California Center nice and toasty, even on the coldest of days.

The steam loops are part of an antiquated system known as "district energy." It was basically a shared-services model: a utility would make steam at a central location and then pipe it out to every building in the city. Nobody had to provide their own heat — it was way more convenient, and cheaper, to get it from a common source.

But then cities began to abandon district energy. Buildings, businesses, and homes started making their own hot water in boilers fueled by coal, then oil, then natural gas. Sometimes it was cheaper, and maybe it was more convenient. But it also set the planet on fire. More heating meant more greenhouse gases, and more global warming.

Which brings me back to our steampunk future. Today, cities are starting to price the looming climate catastrophe into their energy costs. Starting this year, commercial buildings in New York City will be slapped with steep fines if they're emitting too much carbon. Boston and Washington have similar "decarbonization" laws in place, and San Francisco isn't allowing natural gas in any new construction. That means businesses need to find a cleaner, cheaper source of heat.

And those ancient steam loops beneath the streets are starting to seem like a ready-made solution.

"The real benefit of a district-energy system, especially in cities, is the distribution system," says Kevin Hagerty, the CEO of Vicinity Energy. "If a city wants to decarbonize, and they have a district-energy system, it's much easier. They don't have to change things on a building-by-building basis.”

The most convincing evidence that steam loops make economic sense comes from who's getting into the district-energy game. Vicinity, the nation's biggest clean-steam provider, is owned by Antin Infrastructure Partners, a leading private-equity firm. Cordia, an energy provider operating in 10 cities, is partially owned by the private-equity giant KKR. Everyone needs heat — which makes it a highly bankable investment. "These private-equity funds come in and find areas where they can put capital into a business and get a nice steady rate of return," Hagerty says. "Decarbonizing takes capital, and private equity is a great source of capital."

In the long run, of course, private equity may decide to do what it always does and load up these new energy businesses with massive amounts of debt before dismantling them for parts. But for now, the big money sees big profits to be made from America's forgotten infrastructure. Outside of places like airports and college campuses, the idea of district energy fell out of favor long ago. We let the systems go fallow — but fortunately, all the accumulated infrastructure we buried on top of the old steam loops made it impossible to dig their little-used pipes out of the ground. So the whole thing was still down there, waiting, when COVID drove millions of city dwellers to head for the countryside. Now, by drawing heat from their old steam loops, America's cities have an opportunity to jump-start all the downtown commerce that was crippled by the pandemic.

And it could happen all over the place! Dozens and dozens of cities have steam loops they can use, from New York and Chicago to Miami to San Diego and Portland and Milwaukee. What's more, lots of companies these days are looking for greener buildings, both to save money and to burnish their environmental bona fides. From AI startups to biotech companies, steampunk-heated buildings could become the cool new place to be.

"Forward-minded companies want to be in a building that doesn't have any on-site fossil-fuel combustion," says Costa Samaras, the director of the Scott Institute for Energy and Innovation at Carnegie Mellon. "The best, greenest buildings will be net-zero buildings. They'll be considered a premium asset. The challenge is, are we going to get enough premium assets in time?" Meaning: Can we use steam loops to fix the urban doom loop before the climate doom loop dooms us all?

https://www.businessinsider.com/reverse-america-urban-doom-loop-downtown-decline-abandoned-steam-pipes-2024-5

Oriana:

The problem I foresee is that the pipes are old, and thus prone to leakage and worse. And pipes have to be maintained, which can be costly (but not as costly as dealing with a burst pipe). The potential for a large-scale disaster is certainly there.

I keep wondering if solar power could be made efficient enough to be used for heating. Electric heat is very clean and pleasant, but unless you have a gazillion solar panels, it's also expensive. I hope the cost of panels will keep going down, while their efficiency goes up.

*

OLDER ADULTS SLOW THEIR MOVEMENTS TO CONSERVE ENERGY

Researchers recruited 84 healthy participants, including younger adults ages 18 to 35 and older adults ages 66 to 87.

During the study, participants were asked to reach for a target on a screen holding a robotic arm in their right hand. The robotic arm operated similarly to a computer mouse.

Through analyzing the patterns of how study participants performed their reaches, scientists found that older adults modified their movements at certain times to help conserve their more limited amounts of energy, compared to younger adults.

“With age, our muscle cells may become less efficient in transforming energy into muscle force and ultimately movement,” Alaa A. Ahmed, PhD, professor in the Paul M. Rady Department of Mechanical Engineering in the College of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Colorado Boulder and senior author of this study explained to Medical News Today.

“We also become less efficient in our movement strategies, possibly to compensate for lower strength. So we recruit more muscles, which costs more energy, to perform the same tasks.”

Does the brain’s reward circuit still function in older adults?

Ahmed and her team also wanted to see how aging might affect the “reward circuitry” in the brain, as the body produces less dopamine as we grow older.

Once again, participants were asked to use the robotic arm to operate a cursor on a computer screen. The objective was to reach a specific target on the screen. If they hit the target, participants were rewarded with a “bing” sound.

Researchers found both young and older adults arrived at the targets quicker when they knew they would hear the “bing.”

However, scientists say they achieved this differently — younger adults just moved their arms faster while older adults improved their reaction times, starting their reach with the robotic arm about 17 milliseconds sooner on average.

“The fact that the older adults in our study still responded to reward by initiating their movements faster tells us that the reward circuitry is to some extent preserved with age, at least in our sample of older adults. However, there is evidence from other studies that reward sensitivity is reduced with increasing age. What the results do tell us is that while older adults were still similarly sensitive to reward as young adults, they were much more sensitive to effort costs than younger adults, so age seems to have a stronger effect on sensitivity to effort than sensitivity to reward, ” according to Alaa A. Ahmed, PhD, senior study author.

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/why-do-people-move-slower-as-they-get-older-study#Does-the-brains-reward-circuit-still-function-in-older-adults?

Oriana:

I can testify to the kind of aging-related change that the article describes. Imagining the rewards of a certain activity has become heavily tempered by the awareness of its cost in stress. The reward seems less enticing, whereas avoiding or at least lessening the stress is becoming more and more important.

*

A LOW-CARB DIET MAY HELP IBS MORE THAN DRUGS

Dietary changes relieved abdominal pain and other symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome more effectively than medications, a new study shows.

Seven out of 10 study participants reported significant reductions in IBS symptoms after adopting either a type of elimination diet called the FODMAP diet or the simpler-to-follow low-carb diet.

“Diet turned out to be more effective than medical treatment,” said dietician Sanna Nybacka, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. “It's probably more cost effective to provide foods and guidance on how to eat to people than giving them a lot of very expensive medications.”

Moreover, the diet need not be complicated, according to the study published last month in The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology. A low-carbohydrate diet provided nearly as much symptom relief as traditional IBS dietary advice, which limits a group of short-chain carbohydrates known as FODMAPs, found in many common foods including dairy, legumes, onions and garlic and grains.

An estimated 6% of Americans, the majority of them women, suffer from IBS. Symptoms include abdominal pain coupled with diarrhea or constipation or both and no visible signs of disease in the digestive tract. Chronic stress can trigger symptoms.

Researchers randomly divided 294 Swedish adults, mostly women, with moderate to severe IBS symptoms into three groups. One group received traditional IBS dietary advice — including eating regular meals, limiting consumption of coffee, alcohol and soda — along with free home-delivered groceries and recipes for a diet low in FODMAPs, an acronym for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols.

A second group received free home-delivered groceries and recipes for a diet low in carbohydrates. A third group received free optimized pharmaceutical treatment.

After four weeks, participants in both the diet groups reported significantly reduced symptoms — a 76% reduction with the low FODMAP diet and a 71% reduction with the low-carbohydrate diet. The medication group reported a 58% reduction in symptoms.

Two weeks after the study began, one participant, a woman in her 50s on the FODMAP diet, cried as she described the relief from abdominal pain she felt for the first time in her adult life, Nybacka told NPR.

Others in both dietary groups also said they felt better than they had for as long as they could remember, she said.

In addition to IBS symptom relief, participants in all three groups reported less anxiety and depression and an improved quality of life.

After six months, study participants had resumed some of their previous eating habits, but a majority continued to report fewer IBS symptoms.

Researchers were surprised that the low-carbohydrate diet worked as well as it did, Nybacka said. They added the diet to the study after patients who had tried it in an effort to lose weight or control diabetes told them it had reduced their IBS symptoms. A low-carbohydrate diet is easier to follow than a more complicated and restrictive FODMAP diet.

Dr. Lin Chang, a gastroenterologist and a professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said the study supports the long-term benefits of diet in treating IBS. And the study informed her that a low-carb diet, high in protein and fat, could reduce IBS symptoms. “That was new,” she said.

But she believes the study might have biased diet over medicine. “It wasn’t completely a fair comparison,” said Chang, who wasn’t involved with the study.

Patients often need to be on medications for longer than four weeks, the length of the study, to see benefits, Chang said. In addition, American doctors prescribe IBS medications that are unavailable in Sweden, she said.

“Medications are still effective,” she said in a Zoom interview. “And I wouldn't necessarily say that this study to me proved definitively that diet was better or more effective than medication.”

Nybacka agreed that a few additional weeks on some of the prescribed medications might have allowed them to reach their full potential. “But we cannot ignore the fact that the dietary treatment led to a twice as large symptom reduction in just four weeks,” she wrote in an email.

Chang also noted that behavioral therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, which the new research did not study, can reduce IBS symptoms. Some doctors are now prescribing apps that offer mind-body support.

Diets are not for everyone, Chang added. She would not put a patient with disordered eating on an elimination diet, for example.

Following these diets without free grocery and recipe deliveries could be challenging but Chang pointed to meal-services companies, including one in which she owns stock.

ModifyHealth delivers prepared meals designed for people to comply with dietary restrictions. Unlike in the Swedish study, enrollees pay for the food.

https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2024/05/30/g-s1-372/ibs-treatment-diet-low-fodmap-carb

Oriana:

“No sugar, no bread” is my most condensed diet advice. A low carb diet eliminates bread and sugar (including fruit; grapefruit may be one exception).

The carnivore diet eliminates pretty much all the baddies, and can be the end of autoimmune miseries, but it takes very strong motivation to stay with it.

“No bread” is a simplified way of saying “no grains.” That definitely includes oatmeal. Even if oatmeal doesn’t make you sick (I’m probably in a tiny minority), it still raises your blood sugar.

Unfortunately many people, including myself some years ago, fell into the trap of believing that oatmeal was a superfood. I remember one artists’ colony where oatmeal was served every morning. Consequently, after each breakfast I’d get belly cramps and feel so awful I had to lie down. (So much useless suffering and health damage is caused by sheer ignorance and listening to the "experts" instead of your own body).

Fortunately I can eat rice. White basmati rice remains my “rescue food” if I develop any food-related discomfort. Note that I said “white rice.”

After white rice, eggs are another miracle rescue food — especially egg yolks. You can toss the white. It’s the yolk that is the super-nutritious “superfood.”

I avoid “whole grains” in any form. I wonder what percentage of people tolerate “whole grains.”It also the awful taste; I'm thinking of whole-wheat pasta in particular. Perhaps the body is trying to tell us something.

Table sugar (sucrose) is bad because it’s half fructose. The list of detrimental effects of fructose deserves its separate post. A quick reminder: hibernating animals eat fruit to fatten up for winter.

Fruit juice is like fruit squared. An absolute no-no. Maybe grapefruit juice and tomato juice could be claimed as exceptions to the fructose overload

Ripe bananas — forget it. But a greenish banana can be an occasional treat. Because they contain resistant starch, they are supposed to be great food for the gut microbiome.

(Pears are supposed to be excellent for kidney health. That’s why I hesitate to make it “no sugar, no bread, no fruit” — though this could be tried to a while as a weight loss diet. Dietary fructose is converted into fat. High-fructose fruit include bananas [ripe], grapes, mangos [ripe], pineapple, and watermelon. Blueberries contain double the sugar of blackberries. Raspberries are relatively low in sugar. Dried fruit is very high in sugar and calories. On the other hand, dried apricots provide pectin, a soluble fiber that nourishes the good gut bacteria.)

Portion size is also important. Moderation in all things — those ancient Greeks thought of everything.

If you really love sweetness and hate to part with sugar, try allulose. It's found in small amounts in figs, jackfruit, dried fruit, and molasses. The commercial product is made from fructose (obtained from corn), but it won't lead to tooth decay, obesity, or destroy your arteries. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/allulose

Another overarching piece of advice: listen to your body, not to the “experts.” Your body will let you know whether or not you can tolerate oatmeal, for instance. As for the “experts,” every five years or so they seem to change course.

*

Ending on beauty:

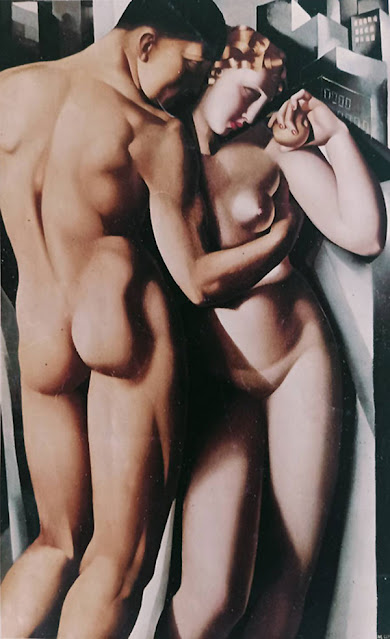

There is not the slightest doubt that the couple in Paradise

were a one-time event.

Just think! Not to be committed to the law of dissolution!

There was no “I.” Only wonder.

The earth just lifted out of chaos.

Grass intensely green, riverbank mysterious.

And a sky in which the sun means love.

~ Czeslaw Milosz, Second Space

Image: Tamara Lempicka, Adam and Eve

No comments:

Post a Comment