HOW TO BUILD A STRADIVARIUS

The masters wrote—to yield the best result,

harvest after a cold winter

the wood condensed by ice and storms

in whose gales the highest notes are born.

From summits of Balkan maple, red spruce

gathered in a valley off the Italian Dolomites,

they carved each instrument’s alluvial curves.

Then came the varnish—one coat

of painter’s oil, another of plain resin.

Only the thinnest layers to obtain

that satin chatoyancy, that liminal reflect.

It’s said Stradivari, playing to the trees

first noticed the straight pines

like strings on a vast, divine violin

absorbing heaven’s vibrations.

The truth could be found in the song itself—

how impossible it was to tell where

the wood ceased and the song began—notes pure

as a mathematical equation.

Transposing mountain. Valley.

Mountain, again.

~ Ilyse Kusnetz

*

Here the message of the poem strangely resembles the message about the plant compounds that stress us the way vitamin pills can’t — hormesis — just the right amount of stress makes us stronger. (“Within the hormetic zone, there is generally a favorable biological response to low exposures to toxins and other stressors.” ~ Wiki)

In this case, the wood for the violin should come from trees stressed by a cold winter —

the wood condensed by ice and storms/

in whose gales the highest notes are born.

Ilyse Kusnetz wrote exquisite poems while struggling with breast cancer. She died in 2016 at the age of 50.

*

“Cherish this book with the tears it will deliver. Treat it as a hymnal, alive with transcendent songs.” — lines in the title poem of Ilyse’s second and last book, Angel Bones.

*

Poetry is a political act because it involves telling the truth. ~ June Jordan

*

THE WIT AND TRAGEDY OF DOROTHY PARKER

~ What are we to make today of this famous woman who, beginning almost a century ago, has fascinated generations with her wit, flair, talent, and near genius for self-destruction? For some, what registers most strongly is her central role in the legend of the Algonquin Round Table, with its campiness of wisecracks, quips, and put-downs—a part of her life she would come to repudiate. For others, it’s the descent into alcoholism, and the sad final years holed up in Manhattan’s Volney Hotel. Pick your myth.

As for her writing, it has evoked ridiculous exaggeration from her votaries, both her contemporaries and her biographers. Vincent Sheean: “Among contemporary artists, I would put her next to Hemingway and Bill Faulkner. She wasn’t Shakespeare, but what she was, was true.” John Keats in his biography of her, You Might as Well Live (1970): “She wrote poetry that was at least as good as the best of Millay and Housman. She wrote some stories that are easily as good as some of O’Hara and Hemingway.” This is praise that manages to be inflated and qualified at the same time.

Certainly she struck a chord with the public: from the start, her voice spoke to a wide range of readers. Her generally sardonic, often angry, occasionally brutal view of men and women—of love and marriage, of cauterized despair—triggered recognition and perhaps even strengthened resolve. She told the truth as she perceived it, while using her wit and humor to hold at arm’s length the feelings that her personal experiences had unleashed in her. An uncanny modern descendant is Nora Ephron in her novel Heartburn, which reimagines her ugly and painful breakup with Carl Bernstein as a barbed comedy.

In 1915, Parker, aged twenty-two, went to work at Vogue (for ten dollars a week), writing captions, proofreading, fact-checking, etc., and after a while moved over to the very young Vanity Fair; her first poem to be published had recently appeared there. She happily functioned as a kind of scribe-of-all-work until three years later she was chosen to replace the departing P.G. Wodehouse as the magazine’s drama critic. She was not only the youngest by far of New York’s theater critics, she was the only female one.

Many amours followed, all of them disastrous and all of them feeding her eternal presentation of herself in her prose and poetry as wounded, heartsick, embittered, soul-weary. Along the way, she had a legal but frightening abortion (she had put it off too long), the father being the charming, womanizing Charles MacArthur, who would go on to cowrite The Front Page and marry Helen Hayes. Parker was crazy about him; his interest waned. The gossip was that when he contributed thirty dollars toward the abortion, she remarked that it was like Judas making a refund.

In 1920 Vanity Fair fired her at the insistence of several important Broadway producers whom her caustic reviews had managed to offend. (Benchley immediately resigned in solidarity with her; Sherwood had already been fired.) Another literary magazine, Ainslee’s, with a far larger readership, took her up and gave her a free hand, and she went on laying waste to the tidal wave of meretricious plays and musicals and revues that opened every year, sometimes ten a week; one Christmas night there were eight premieres. Yet—always just, if not always kind—she recognized and saluted real achievement when she actually came upon it.

Meanwhile, her verses and stories were appearing profusely and everywhere: not only in upscale places like Vanity Fair (which was happier to publish her than employ her), The Smart Set, and The American Mercury, but also in the popular Ladies’ Home Journal, Saturday Evening Post, Life (when it was still a comic magazine), and—starting with its second issue early in February 1925—her old pal Harold Ross’s new venture, The New Yorker, with which she would have an extended on-again, off-again love affair.

Death and suicide are never far from her thoughts—she titled her collections Enough Rope, Sunset Gun, Death and Taxes, and Not So Deep as a Well, the first of them a major best seller in 1926, confirming her fame.

Was her poetry just rhyming badinage dressed up as trenchant, plaintive ruminations on love, loss, and death? Her subjects are serious, but her cleverness undercuts them: there’s almost always a last line, a sardonic zinger, to signal that even if she does care, the more fool she. Even her most famous couplet—“Men seldom make passes/At girls who wear glasses”—bandages a wound, although plenty of men made passes.

She was clear about her versifying. “There is poetry and there is not,” she once wrote in The New Yorker, and she knew hers was not. She thought her stories were superior to her poems (she was right), but that wasn’t good enough for her. She never managed to write The Novel (as at that time every writer dreamed of doing). Did Hemingway like her work? Did he like her? (He didn’t, but she didn’t know it. As she was dying, Lillian Hellman had to assure her that he did.)

Nor did she have much respect for what she and her second husband, the handsome, possibly gay actor and writer Alan Campbell, whom she married twice, did in Hollywood. (She liked referring to him publicly as “the wickedest woman in Paris.”) They worked hard at their assignments and raked in the chips, and she was twice nominated for an Oscar (A Star Is Born, 1937; Smash-Up: The Story of A Woman, 1947), but her view of film writing never changed from her verdict about it when she was first venturing out to California: “Why, I could do that with one hand tied behind me and the other on Irving Thalberg’s pulse.”

A turning point in Parker’s life came in 1927 when she went to Boston to protest the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. It was her first political action, but it came from deep inside her, and she persisted—infiltrating the prison, getting arrested, marching with other writers like John Dos Passos, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Katherine Anne Porter. They didn’t prevail at this low point in the history of justice in America, but she hadn’t backed down. And as time would show, her actions were not just some outburst of what, decades later, would come to be labeled radical chic.

From then on she was committed to liberal or radical causes. She vigorously supported the Loyalists in Spain, even spending ten days with Alan under the bombs in Madrid and Valencia. She helped found the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. Whether she actually joined the Communist Party for a short time remains an unanswered question. Although Hellman claimed she was subpoenaed by HUAC and appeared before the committee, this (like so much else in Hellman’s memoirs) is simply untrue. She was, though, visited by two FBI agents in 1951. When they asked her whether she had ever conspired to overthrow the government, she answered, “Listen, I can’t even get my dog to stay down. Do I look to you like someone who could overthrow the government?” The FBI gave her a pass.

In the 1930s she had raised money for the defense of the Scottsboro boys, and she never relaxed her efforts in the field of civil rights: when she died, in 1967, her literary estate was left to Martin Luther King, and then to the NAACP, and her ashes are buried in a memorial garden at the organization’s headquarters in Baltimore.

Her emotional life was less consistent. Men had always been in and out of her life, and she inevitably ended up feeling rejected, betrayed, unwanted. She and Campbell loved each other in their way, but their way seems to have been that of a convenient partnership—he could construct stories, she could come up with convincing dialogue; he flattered and cajoled her out of her anxieties and despairs, she legitimized him in the big world. It might have been different if they had had the child she desperately wanted, but in her forties she miscarried more than once, had a hysterectomy, and that was that.

Worst of all, as time went by everybody was dying, and far too young, from her idol Ring Lardner at forty-eight and Benchley at fifty-six to Scott Fitzgerald at forty-four. (“The poor son-of-a-bitch,” she murmured over his coffin at his sparsely attended Hollywood funeral.) Helen, her sister, was gone. Who was left? Edmund Wilson was still around—they had almost had a fling way back in 1919; now he paid occasional painful visits to her at the Volney. (“She lives with a small and nervous bad-smelling poodle bitch, drinks a lot, and does not care to go out.”)

She was still revered, a legend, but she had also become a pathetic relic. Yes, “you might as well live,” but for what? And on what? Not only was she running out of old friends, she was running out of money, though uncashed checks, some quite large, were strewn around her apartment (along with the empty bottles), not helping with unpaid bills.

*

The thirty-one reprinted reviews range in subject from the ludicrous to the sublime. Predictably, Parker is deadly when dealing with nonsense or pretension. Her targets include Nan Britton, who wrote a tell-all book about her love affair (and illegitimate baby) with President Warren Harding, the notorious evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, and Emily Post and her Etiquette. (She did not react positively to Mrs. Post’s suggestion that to get a conversation going with a stranger, you might try, “I’m thinking of buying a radio. Which make do you think is best?”)

So she’s funny. More impressive is her uncannily astute judgment. She admires Katherine Mansfield, Dashiell Hammett (she loved thrillers almost as much as she loved dogs), Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier, Hemingway’s short stories (more than his novels), of course Ring Lardner, Gide’s The Counterfeiters—“too tremendous a thing for praises. To say of it ’Here is a magnificent novel’ is rather like gazing into the Grand Canyon and remarking, ’Well, well, well; quite a slice.’”

Her most impassioned praise is reserved for Isadora Duncan. Despite calling it “abominably written,” she characterized Duncan’s posthumous autobiography, My Life, as “an enormously interesting and a profoundly moving book. Here was a great woman; a magnificent, generous, gallant, reckless, fated fool of a woman. There was never a place for her in the ranks of the terrible, slow army of the cautious. She ran ahead, where there were no paths.”

Parker would always rise to the challenges of greatness and of garbage; it was what fell in between that drove her crazy.

She was too sensible to live in regret, but she certainly understood how much of her life she had spent carousing and just fooling around. The tragedy of Dorothy Parker, it seems to me, isn’t that she succumbed to alcoholism or died essentially alone. It was that she was too intelligent to believe that she had made the most of herself. ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/brilliant-troubled-dorothy-parker?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

I am tempted to say that the had the makings of becoming America’s Oscar Wilde . . . ah, if only she wrote plays or produced an equivalent of Dorian Gray — but perhaps that’s hoping for too much.

*

ARE RUSSIANS DYING FOR LACK OF HOPE?

~ In the seventeen years between 1992 and 2009, the Russian population declined by almost seven million people, or nearly 5 percent—a rate of loss unheard of in Europe since World War II. Moreover, much of this appears to be caused by rising mortality. By the mid-1990s, the average St. Petersburg man lived for seven fewer years than he did at the end of the Communist period; in Moscow, the dip was even greater, with death coming nearly eight years sooner.

In 2006 and 2007, Michelle Parsons, an anthropologist who teaches at Emory University and had lived in Russia during the height of the population decline in the early 1990s, set out to explore what she calls “the cultural context of the Russian mortality crisis.” Her method was a series of long unstructured interviews with average Muscovites—what amounted to immersing herself in a months-long conversation about what made life, for so many, no longer worth living. The explanation that Parsons believes she has found is in the title of her 2014 book, Dying Unneeded.

By the early 1980s, the Soviet economy was stagnant and the Soviet political system moribund. Finally, a younger leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, emerged, but the decrepit structure proved incapable of change and, in short order, collapsed, taking with it the predictable life as hundreds of millions of people had known it. Russia rushed into a new capitalist future, which most of the population expected to bring prosperity and variety. Boris Yeltsin and his team of young, inexperienced reformers instituted economic shock therapy. As far as we know today, this series of radical measures jerked Russia back from the edge of famine but also plunged millions of people into poverty. Over the next decade, most Russian families—like their counterparts elsewhere in the former Soviet Union—actually experienced an improvement in their living conditions, but few who had spent many adult years in the old system regained the sense of solid ground under their feet.

Not only had the retirement system collapsed, but neither the job market nor their own families—those grown children who had once been entirely dependent on their parents—had any use for these people. Gone, too, was the radiant future: communist slogans were replaced with capitalist advertising that didn’t speak to the masses, who were in no position to over-consume. For those over forty, the message of the new era was that no one—not even the builders of an imaginary future—needed them anymore.

Above all, the veil that had hidden the wealth of the few from the incredulous and envious gaze of the many had been ruthlessly removed: for the 1990s and much of the 2000s, Moscow would become the world capital of conspicuous consumption. No longer contributing to or enjoying the benefits of the system, members of the older generations, Parsons suggests, were particularly susceptible to early death.

If we zoom out from the early 1990s, where Parsons has located the Russian “mortality crisis,” we will see something astounding: it is not a crisis—unless, of course, a crisis can last decades. “While the end of the USSR marked one [of] the most momentous political changes of the twentieth century, that transition has been attended by a gruesome continuity in adverse health trends for the Russian population,” writes Nicholas Eberstadt in Russia’s Peacetime Demographic Crisis: Dimensions, Causes, Implications, an exhaustive study published by the National Bureau of Asian Research in 2010.

Eberstadt is interested in the larger phenomenon of depopulation, including falling birth rates as well as rising death rates. He observes that this is not the first such trend in recent Russian history. There was the decline of 1917–1923—the years of the revolution and the Russian Civil War when, Eberstadt writes, “depopulation was attributable to the collapse of birth rates, the upsurge in death rates, and the exodus of émigrés that resulted from these upheavals.”

There was 1933–1934, when the Soviet population fell by nearly two million as a result of murderous forced collectivization and a man-made famine that decimated rural Ukraine and, to a lesser extent, Russia. Then, from 1941 to 1946, the Soviet Union lost an estimated 27 million people in the war and suffered a two-thirds drop in birth rate. But the two-and-a-half decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union are the longest period of depopulation, and also the first to occur, on such a scale, in peacetime, anywhere in the world. “There is no obvious external application of state force to relieve, no obvious fateful and unnatural misfortune to weather, in the hopes of reversing this particular population decline,” writes Eberstadt. “Consequently, it is impossible to predict when (or even whether) Russia’s present, ongoing depopulation will finally come to an end.”

Russia has long had a low birth rate. The Soviet government fought to increase it by introducing a three-year maternity leave and other inducements, but for much of the postwar period it hovered below replacement rates. An exception was the Gorbachev era, when fertility reached 2.2. After 1989, however, it fell and still has not recovered: despite financial inducements introduced by the Putin government, the Russian fertility rate stands at 1.61, one of the lowest in the world (the US fertility rate estimate for 2014 is 2.01, which is also below replacement but still much higher than Russia’s).

And then there is the dying. In a rare moment of what may pass for levity Eberstadt allows himself the following chapter subtitle: “Pioneering New and Modern Pathways to Poor Health and Premature Death.” Russians did not start dying early and often after the collapse of the Soviet Union. “To the contrary,” writes Eberstadt, what is happening now is “merely the latest culmination of ominous trends that have been darkly evident on Russian soil for almost half a century.”

With the exception of two brief periods—when Soviet Russia was ruled by Khrushchev and again when it was run by Gorbachev—death rates have been inexorably rising. This continued to be true even during the period of unprecedented economic growth between 1999 and 2008. In this study, published in 2010, Eberstadt accurately predicts that in the coming years the depopulation trend may be moderated but argues that it will not be reversed; in 2013 Russia’s birthrate was still lower and its death rate still higher than they had been in 1991. And 1991 had not been a good year.

Contrary to Parsons’s argument, moreover, Eberstadt shows that the current trend is not largely a problem of middle-aged Russians. While the graphs seem to indicate this, he notes, if one takes into account the fact that mortality rates normally rise with age, it is the younger generation that is staring down the most terrifying void. According to 2006 figures, he writes, “overall life expectancy at age fifteen in the Russian Federation appears in fact to be lower than for some of the countries the UN designates to be least developed (as opposed to less developed), among these, Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Yemen.” Male life expectancy at age fifteen in Russia compares unfavorably to that in Ethiopia, Gambia, and Somalia.

Eberstadt sets out to find the culprit, and before conceding he can’t, he systematically goes down the list of the usual suspects. Infectious diseases, including not only HIV and TB but also normally curable STDs and every kind of hepatitis, have the run of the land in Russia, but do not in fact seem overrepresented in its death statistics; from a demographer’s point of view, as many Russians die of infections as would be expected in a country of its income level. Cardiovascular disease is an entirely different matter:

~ As of 1980, the Russian population may well have been suffering the very highest incidence of mortality from diseases of the circulatory system that had ever been visited on a national population in the entire course of human history—up to that point in time. Over the subsequent decades, unfortunately, the level of CVD mortality in the Russian Federation veered further upward…. By 2006… Russia’s mortality levels from CVD alone were some 30% higher than deaths in Western Europe from all causes combined. ~

And then there are the deaths from external causes—again going from bad to worse. “Deaths from injuries and poisoning had been much higher in Russia than in Western Europe in 1980—well over two and a half times higher, in fact.” As of 2006, he writes, it was more than five times as high.

So why do Russians have so many heart attacks, strokes, fatal injuries, and poisonings? One needs to have only a passing knowledge of Russian history and culture to tick off a list of culprits, and Eberstadt is thorough in examining each of them. True, Russians eat a fatty diet—but not as fatty as Western Europeans do. Plus, Russians, on average, consume fewer calories than Western Europeans, indicating that overeating is not the issue.

The most obvious explanation for Russia’s high mortality—drinking—is also the most puzzling on closer examination. Russians drink heavily, but not as heavily as Czechs, Slovaks, and Hungarians—all countries that have seen an appreciable improvement in life expectancy since breaking off from the Soviet Bloc. Yes, vodka and its relatives make an appreciable contribution to the high rates of cardiovascular, violent, and accidental deaths—but not nearly enough to explain the demographic catastrophe. There are even studies that appear to show that Russian drinkers live longer than Russian non-drinkers.

Parsons discusses these studies in some detail, and with good reason: it begins to suggest the true culprit. She theorizes that drinking is, for what its worth, an instrument of adapting to the harsh reality and sense of worthlessness that would otherwise make one want to curl up and die.

For Eberstadt, who is seeking an explanation for Russia’s half-century-long period of demographic regress rather than simply the mortality crisis of the 1990s, the issue of mental health also furnishes a kind of answer. While he suggests that more research is needed to prove the link, he finds that “a relationship does exist” between the mortality mystery and the psychological well-being of Russians:

Another major clue to the psychological nature of the Russian disease is the fact that the two brief breaks in the downward spiral coincided not with periods of greater prosperity but with periods, for lack of a more data-driven description, of greater hope. The Khrushchev era, with its post-Stalin political liberalization and intensive housing construction, inspired Russians to go on living. The Gorbachev period of glasnost and revival inspired them to have babies as well. The hope might have persisted after the Soviet Union collapsed—for a brief moment it seemed that this was when the truly glorious future would materialize—but the upheaval of the 1990s dashed it so quickly and so decisively that death and birth statistics appear to reflect nothing but despair during that decade.

If this is true—if Russians are dying for lack of hope, as they seem to be—then the question that is still looking for its researcher is, Why haven’t Russians experienced hope in the last quarter century? Or, more precisely in light of the grim continuity of Russian death, What happened to Russians over the course of the Soviet century that has rendered them incapable of hope?

In The Origins of Totalitarianism Hannah Arendt argues that totalitarian rule is truly possible only in countries that are large enough to be able to afford depopulation. The Soviet Union proved itself to be just such a country on at least three occasions in the twentieth century—teaching its citizens in the process that their lives are worthless.

Is it possible that this knowledge has been passed from generation to generation enough times that most Russians are now born with it and this is why they are born with a Bangladesh-level life expectancy? Is it also possible that other post-Soviet states, by breaking off from Moscow, have reclaimed some of their ability to hope, and this is why even Russia’s closest cultural and geographic cousins, such as Belarus and Ukraine, aren’t dying off as fast? If so, Russia is dying of a broken heart—also known as cardiovascular disease.

~ Masha Gessen is the author of “The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia,” which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction in 2017.

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/the-dying-russians?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

Other sources give Russia’s population loss during WW2 as 13 million. In school, we were told 20 million — this included all inhabitants of the Soviet Union, not just ethnic Russians. Even assuming “only” 13 million, that’s still staggering.

But the emphasis of this article is the population decline starting in 1992.

From another source:

~ Between 1976 and 1991, the last sixteen years of Soviet power, the country recorded 36 million births. In the sixteen post-Communist years of 1992–2007, there were just 22.3 million, a drop in childbearing of nearly 40 percent from one era to the next.

On the other/side of the life cycle, a total of 24.6 million deaths were recorded between 1976 and 1991, while in the first sixteen years of the post-Communist period the Russian Federation tallied 34.7 million deaths, a rise of just over 40 percent. The symmetry is striking: in the last sixteen years of the Communist era, births exceeded deaths in Russia by 11.4 million; in the first sixteen years of the post-Soviet era, deaths exceeded births by 12.4 million. ~

https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/upload/AspenItalia_section_5_eberstadt.pdf

Most developed countries are not reproducing at replacement level — it’s a more general phenomenon. Some predict that the size of humanity as a whole will shrink (and I think it should, if humanity is to continue). In Russia the phenomenon of shrinking population seems particularly acute. If we are to believe the article, it's related to the lack of hope for a better life.

But at bottom there is a larger question: is life sufficiently worth living to offset the inevitable suffering? By bringing another human being into existence, we are in effect creating another death-row inmate, metaphorically speaking. Can life’s joys offset that?

In terms of climate change, is it fair to have children when climate disasters grow more numerous and extreme every year?

And, in more immediate terms, why is having a child so expensive? Some parents simply can’t afford to have more than one child. I suspect that affordable quality childcare would make parenting easier and thus might encourage more childbearing.

But it’s the reduced life expectancy that, to me, is a more worrisome phenomenon. An increase in middle-aged men dying of suicide — that should give us a pause.

Charles:

I think another reason the Russians are dying is because they are simply not happy for all the reasons the article mentioned. Bottom line there is nothing to live for. No future for the individuals or families.

I think two charges are needed. If religion was encouraged there would be a boost to the human spirit and population growth. I also believe that with religion people are happier. The other is capitalism.

Oriana:

Russian capitalism is so corrupt, I’m not sure that the small guy has a chance.

As for religion, they have the Russian Orthodox church, which I strongly suspect is out of touch and out of date, and very Putin-friendly.

I imagine SOME Russians are fairly happy — e.g. a surgeon who feels he’s saving lives, a teacher who loves teaching, a dedicated scientist, a passionate artist — people who do what they love doing. That of course holds all over the world.

But being happy with your job/vocation doesn’t always lead to the desire to have children, especially for women. The reasons have been discussed for many decades now. Again, quality childcare could make a difference.

Mary:

*

Peter Brueghel Superbia (Pride). I chose this to illustrate the arrogance of imagining that we can engineer an ideal society. Alas, after the heroics of the idealists, the psychopaths take charge. The Reign of Terror and/or extreme corruption are the expected outcomes.

*

FROM “SHE” TO “HE” — AND BACK AGAIN

~ Studies suggest that most people who transition to another gender do not have second thoughts. But after two trans men met and fell in love, their personal gender journeys took an unexpected turn, to a destination neither had foreseen.

Ellie is 21 and Belgian. Her German partner, Nele, is 24. Both took testosterone to become more masculine, and they had their breasts removed in double mastectomy surgery. Now they have detransitioned, and live again as female — the gender they were assigned at birth.

"I'm very happy I didn't have a hysterectomy," reflects Nele. "It means I can stop taking hormones, and my body will return to looking feminine.”

Last year, they both made the decision to end their use of testosterone and start using the female pronouns "she" and "her" again. Slowly their own natural oestrogen has begun to re-feminize their bodies.

"I'm very excited to see the changes," says Ellie.

Their faces have softened, their bodies become curvier. But years of taking testosterone has had one profound, irreversible effect.

"My voice will never come back," says Nele. "I used to love singing and I can't sing any more - like my voice is just very monotone, it works very differently. When I call someone on the phone, I get gendered as male.”

The stories of these two young people are complex.

They may not be typical of people who have transitioned to another gender. And they are not a judgement on the decisions of other trans people, be they trans men, trans women or non-binary.

Ellie does not remember being uncomfortable as a girl when she was a child. But that changed as she became adolescent.

"I realized I was doing a lot of boy things, and some people weren't fine with that - especially other kids. I remember being called things like ‘hermaphrodite'."

Tall and athletic, Ellie's love of basketball was identified as, "a boy thing" too. At 14, she realised she was attracted to other girls, and later came out to her parents.

"I was dating girls and happy about it," she says.

Then Ellie told her sister she was a lesbian.

"My sister told me she was proud of the woman I was becoming. And somehow that rang a bell for me. And I remember thinking, 'Oh, so I'm a woman now? I don't feel comfortable with that.' It wasn't that I wanted to be a boy - I just didn't want to be a woman. I wanted to be neutral and do whatever I wanted.”

At 15, Ellie believed becoming a woman might limit her choices in life. For Nele too, growing up female was not fun.

"It started with puberty, when I was around nine years old - with getting breasts before I even realized what it means to have them. My mother forbade me from going outside bare-chested. We had a lot of fights because I was like, 'Why can my brother go out bare-chested?' Obviously, my mother wanted to protect me, but I couldn't understand at the time.”

As Nele matured, there were also lecherous men to contend with.

"I experienced a lot of catcalling. There was a street next to mine, and I couldn't go down there without a man hitting on me. I'm slowly realizing now that I internalized all of that - that I was perceived in society as something sexy, something men desire, but not a personality.”

With her body developing fast, Nele saw herself as too large. She would later develop an eating disorder.

"Too fat, too wide - the thoughts about needing to lose weight started very early.”

Nele was attracted to women, but the thought of coming out as a lesbian was terrifying.

"I really had this image that I would be this disgusting woman, and that my friends wouldn't want to see me anymore because they'd think I might hit on them.”

At 19, Nele came out as bisexual — that seemed safer. But the experience of unwanted male attention and the discomfort she felt with her female body stayed with her. Nele fantasized about removing her breasts. Then she learned trans men get mastectomies.

"And I was like, 'Yeah, but I'm not trans.' And then I was like, 'Maybe I could fake being trans?' And then I was doing a lot of research and I realized a lot of those things trans men say are very similar to what I experienced — like 'I always felt uncomfortable with my body, and as a kid I wanted to be a boy.’"

The distress trans people feel because there is a mismatch between their gender identity and their biological sex is called gender dysphoria. Nele thinks her own dysphoria began around this time.

"I thought, actually, 'I don't have to fake being trans. I am transgender.’"

Nele could see only two options - transition or suicide. She sought help from a transgender support organization. They sent her to a therapist.

"When I arrived, I was like, 'Yeah, I think I might be trans.' And he directly used male pronouns for me. He said it was so clear I'm transgender - that he's never been as sure with anyone else.”

Within three months, Nele was prescribed testosterone.

Ellie too became determined to access male hormones - in her case when she was just 16.

"I watched some YouTube videos of trans guys who take testosterone, and they go from this shy lesbian to a handsome guy who is super-popular. I liked thinking of myself having that possibility - it felt like I should have a male body.”

But being so young, she needed parental approval for any medical intervention. The first doctor she visited with her parents said Ellie should wait - she thought that was transphobic and found another medic who was positive about her desire to transition.

"He told my parents that all the effects were reversible - which is the biggest lie. I had done my research, and I knew that this doctor could not be trusted. But I was just so happy that he said that, because then my parents were OK with it.”

Ellie's dad, Eric, was worried about the impact testosterone would have on his child's health, but the doctor reassured him.

"We were still in shock from having a girl who wanted to be a boy," he remembers. "And the doctor said hormones would be better for her."

Eric and Ellie's mum felt all at sea in this new world of changing genders.

"I would've liked to have met someone to give me the words and find arguments to make her wait and think about it longer, but there was no-one," he reflects.

At first, testosterone made Ellie feel emotionally numb. Then she felt much better. At 17, she had a double mastectomy. Later, she graduated from high school, and left Belgium to go to university in Germany.

Transitioning to male had not ended Nele's feelings of despair. She was still suicidal, and her eating disorder was manifesting itself in extreme calorie-counting, and an obsession with her diet. Nele began to think testosterone was the only good thing in her life - and she still wanted a mastectomy. But she did not feel she could be totally honest with her gender therapist.

"I was very ashamed of my eating disorder. I mentioned it in the beginning, but I didn't dare talk about it more because of the shame - I think that's normal with eating disorders.”

Nele was worried her transgender treatment might be halted if there was any doubt about her mental health.

"It's a very tricky situation in Germany, because the therapist is the one who gives you the prescriptions for hormones and for surgery."

There are few studies exploring the link between eating disorders and gender dysphoria. One review of the UK's Gender Identity Development Service in 2012 showed that 16% of all adolescent referrals in that year had some kind of "eating difficulty". But bear in mind that most referrals are young people assigned female at birth — natal girls, as they are called, who are more vulnerable to eating disorders than their natal male counterparts.

As a new student and trans man in Germany, Ellie thought her own dysphoria was a thing of the past, and she was getting on with life.

"I was passing as a man — I was passing so well. I got so many comments from people telling me my transition was such a success, because they couldn't tell I was trans.”

But an ambivalence about her male identity crept in.

"I started to feel like I had to hide so many aspects of my life, and not talk about my childhood as a girl. I didn't feel comfortable being seen as a cis man, and I started to feel like I didn't fit in anywhere.”

Dating was problematic.

"I wasn't comfortable dating women because I didn't want to be taken for a straight guy. And this discomfort I had with my own body parts… Well, I started to see female bodies as less good-looking, less valuable in a way.”

Ellie began to be attracted to men and identified as pansexual.

"I think that came about because of internalized misogyny. But I never really felt any connection with any cis men. Then I thought, maybe dating another trans man would make me feel close to someone and attracted at the same time."

Did it work?

"It totally worked!”

So Ellie went on a dating app and met Nele — who was not especially looking for romance with another trans man.

"But it was definitely a plus when I started texting with Ellie. We share a lot of experiences, and I feel very comfortable around her.”

After a first date in Düsseldorf, their relationship moved swiftly. Nele got the go-ahead for a long-desired mastectomy, and Ellie was a great support. The couple moved into a flat together.

And it was around this time that Ellie, a gender studies student, became interested in the culture war between trans activists and radical feminists that often erupts in the social media ether.

She started to question whether she was really transgender. "Or is this just a way I found to go through life?" she wondered.

Ellie and Nele had intense discussions about their own identities.

And there was something else - both were diagnosed with vaginal atrophy, a soreness and dryness commonly found in menopausal women, but also a side-effect of taking testosterone. The remedy was estrogen cream.

"But it didn't really help," says Nele. "And I thought, 'I'm putting my body full of hormones, when my body can make those on its own.’"

Ellie felt the same way.

That is when they stopped taking testosterone. But the decision to detransition was daunting.

"I was afraid of ending the hormones and going back to my body. I didn't even know my natural body because I transitioned so early," says Ellie.

"The thought of going back was scary, because I transitioned to escape my problems. Detransitioning means facing the things I never managed to overcome," says Nele.

There is little academic research about detransition. The studies that have been done suggest the rate of detransition is very low — one put the proportion of trans people who return to the gender they were assigned at birth at less than 0.5%. But so far, researchers have not taken a large cohort of transitioning people and followed them over a number of years.

"The longitudinal studies just haven't been done," says Dr Catherine Butler, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath.

"But on social media - for example on Reddit — there's a detransitioning group that has over 9,000 readers. There will be academics like myself who are part of that, but even so, it is a huge number of people.”

The lack of academic research in this area has an impact for those re-thinking their gender journeys.

"It means there aren't guidelines or policy that informs how statutory services can support detransitioners. So they've had to self-organize, to establish their own networks," she says.

And that is what Nele and Ellie did. Using Nele's skills as a professional illustrator, they created post-trans.com — an online space where people like them can get in touch and share their experiences.

Both of these young people are conscious of how stories of detransition have been used by transphobic organizations and commentators to invalidate the experience of trans and non-binary people, and attack their hard-fought access to health care. Neither Ellie nor Nele deny the rights of trans people. They do, however, question whether transition is always the right solution.

Now, just months into their detransition, they are adjusting to life as female and lesbian. And so are their friends and family.

"It was hard for her to call us and tell us," says Eric, Ellie's father, who is still getting used to using female pronouns for his once-again daughter.

"It's not black or white for me. I knew from the start when she first transitioned she would never be a man - she never had the idea of having the complete operation. So now it's a new in-between somewhere, but it's always her.”

So does his daughter regret her choices — her mastectomy, for example?

"All those physical changes I experienced during my transition helped me develop a closer relationship with my body — they're just part of my journey," says Ellie.

Nele is similarly sanguine.

"Bodies change through ageing and accidents — I don't feel sad my breasts are gone.”

Neither plans to have reconstructive surgery. More difficult sometimes is the experience of once again being gendered as female — especially by men on lonely station platforms at night, who might be a threat.

"Because if he perceives me as a man, I wouldn't feel that… But if I'm seen as a woman, maybe I'm in danger and have to watch out," says Nele.

But her experience — from "she" to "he" and back to "she" again — has also had a positive impact, especially on Nele's career.

"I always perceived myself as, 'Well, I'm just a girl who draws — I couldn't be a professional, self-employed illustrator.' And then I transitioned to become a man, and suddenly I was like, 'Oh, I can do those things.' It's something I hear a lot, that trans men feel more confident. I had the same experience. So I will take that and keep it."

Ellie and Nele boarded a gender rollercoaster when they were still teenagers. It has not been an easy ride.

Now they are moving on, looking forward to life — perhaps with the addition of some pet cats.

https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-51806011

Charles:

The two of them are perfect for each other. Both always change their identity in growth. At this point they realized the best thing was to get cats.

Oriana:

I agree. They look so happy in the photo, in a way that can’t be faked. I wish them the best.

*

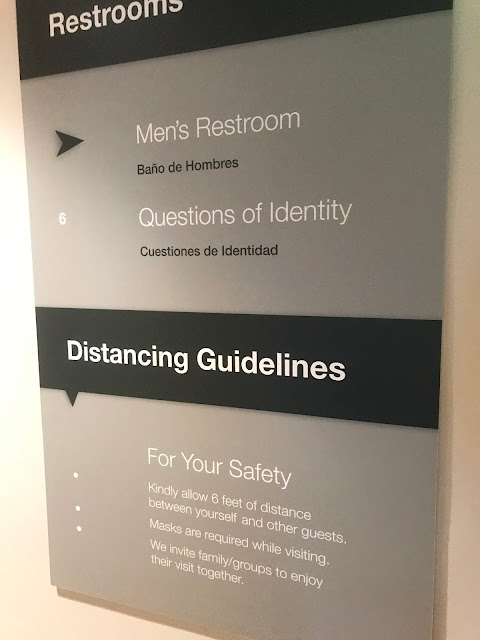

Sign in the San Diego Museum of Art

*

WILL COVID RESULT IN SAFER CITIES?

~ On December 16, 1835, New York’s rivers turned to ice, and Lower Manhattan went up in flames. Smoke had first appeared curling through the windows of a five-story warehouse near the southern tip of Manhattan. Icy gales blew embers into nearby buildings, and within hours the central commercial district had become an urban bonfire visible more than 100 miles away.

Firefighters were helpless. Wells and cisterns held little free-flowing water, and the rivers were frozen solid on a night when temperatures plunged, by one account, to 17 degrees below zero. The fire was contained only after Mayor Cornelius Lawrence ordered city officials to blow up structures surrounding it, starving the flames of fuel.

A new Manhattan would grow from the rubble—made of stone rather than wood, with wider streets and taller buildings. But the most important innovation lay outside the city. Forty-one miles to the north, New York officials acquired a large tract of land on both sides of the Croton River, in Westchester County. They built a dam on the river to create a 400-acre lake, and a system of underground tunnels to carry fresh water to every corner of New York City.

The engineering triumph known as the Croton Aqueduct opened in 1842. It gave firefighters an ample supply of free-flowing water, even in winter. More important, it brought clean drinking water to residents, who had suffered from one waterborne epidemic after another in previous years, and kick-started a revolution in hygiene. Over the next four decades, New York’s population quadrupled, to 1.2 million—the city was on its way to becoming a fully modern metropolis.

The 21st-century city is the child of catastrophe. The comforts and infrastructure we take for granted were born of age-old afflictions: fire, flood, pestilence. Our tall buildings, our subways, our subterranean conduits, our systems for bringing water in and taking it away, our building codes and public-health regulations—all were forged in the aftermath of urban disasters by civic leaders and citizen visionaries.

Natural and man-made disasters have shaped our greatest cities, and our ideas about human progress, for millennia. Once Rome’s ancient aqueducts were no longer functional—damaged first by invaders and then ravaged by time—the city’s population dwindled to a few tens of thousands, reviving only during the Renaissance, when engineers restored the flow of water.

The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 proved so devastating that it caused Enlightenment philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau to question the very merits of urban civilization and call for a return to the natural world. But it also led to the birth of earthquake engineering, which has evolved to make San Francisco, Tokyo, and countless other cities more resilient.

America’s fractious and tragic response to the COVID-19 pandemic has made the nation look more like a failed state than like the richest country in world history. Doom-scrolling through morbid headlines in 2020, one could easily believe that we have lost our capacity for effective crisis response. And maybe we have. But a major crisis has a way of exposing what is broken and giving a new generation of leaders a chance to build something better. Sometimes the ramifications of their choices are wider than one might think.

The Invention of Public Health

As Charles Dickens famously described, British cities in the early years of the Industrial Revolution were grim and pestilential. London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds—they didn’t suffer from individual epidemics so much as from overlapping, never-ending waves of disease: influenza, typhoid, typhus, tuberculosis.

They were also filled with human waste. It piled up in basements, spilled from gutters, rotted in the streets, and fouled rivers and canals. In Nottingham—the birthplace of the Luddite movement, which arose to protest textile automation—a typical gallon of river water contained 45 grams of solid effluent. Imagine a third of a cup of raw sewage in a gallon jug.

No outbreak during the industrial age shocked British society as much as the cholera epidemic in 1832. In communities of 100,000 people or more, average life expectancy at birth fell to as low as 26 years. In response, a young government official named Edwin Chadwick, a member of the new Poor Law Commission, conducted an inquiry into urban sanitation. A homely, dyspeptic, and brilliant protégé of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham, Chadwick had farsighted ideas for government. They included shortening the workday, shifting spending from prisons to “preventive policing,” and establishing government pensions. With a team of researchers, Chadwick undertook one of the earliest public-health investigations in history—a hodgepodge of mapmaking, census-taking, and dumpster diving. They looked at sewers, dumps, and waterways. They interviewed police officers, factory inspectors, and others as they explored the relationship between city design and disease proliferation.

The final report, titled “The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain,” published in 1842, caused a revolution. Conventional wisdom at the time held that disease was largely the result of individual moral shortcomings. Chadwick showed that disease arose from failures of the urban environment. Urban disease, he calculated, was creating more than 1 million new orphans in Britain each decade. The number of people who had died of poverty and disease in British cities in any given year in the 1830s, he found, was greater than the annual death toll of any military conflict in the empire’s history. The cholera outbreak was a major event that forced the British government to reckon with the costs of industrial capitalism. That reckoning would also change the way Western cities thought about the role of the state in ensuring public health.

The source of the cholera problem? All that filthy water. Chadwick recommended that the government improve drainage systems and create local councils to clear away refuse and “nuisance”—human and animal waste—from homes and streets. His investigation inspired two key pieces of national legislation, both passed in 1848: the Public Health Act and the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act. A new national Board of Health kept the pressure on public authorities. The fruits of engineering (paved streets, clean water, sewage disposal) and of science (a better understanding of disease) led to healthier lives, and longer ones. Life expectancy reached 40 in England and Wales in 1880, and exceeded 60 in 1940.

Chadwick’s legacy went beyond longevity statistics. Although he is not often mentioned in the same breath as Karl Marx or Friedrich Engels, his work was instrumental in pushing forward the progressive revolution in Western government. Health care and income support, which account for the majority of spending by almost every developed economy in the 21st century, are descendants of Chadwick’s report. David Rosner, a history and public-health professor at Columbia University, puts it simply: “If I had to think of one person who truly changed the world in response to an urban crisis, I would name Edwin Chadwick. His population-based approach to the epidemics of the 1830s developed a whole new way of thinking about disease in the next half century. He invented an entire ethos of public health in the West.”

Why We Have Skyscrapers

Everyone knows the story: On the night of October 8, 1871, a fire broke out in a barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary in southwest Chicago. Legend blames a cow tipping over a lantern. Whatever the cause, gusty winds drove the fire northeast, toward Lake Michigan. In the go-go, ramshackle era of 19th-century expansion, two-thirds of Chicago’s structures were built of timber, making the city perfect kindling. In the course of three days, the fire devoured 20,000 buildings. Three hundred people died. A third of the city was left without shelter. The entire business district—three square miles—was a wasteland.

On October 11, as the city smoldered, the Chicago Tribune published an editorial with an all-caps headline: cheer up. The newspaper went on: “In the midst of a calamity without parallel in the world’s history, looking upon the ashes of thirty years’ accumulations, the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that Chicago shall rise again.” And, with astonishing speed, it did. By 1875, tourists arriving in Chicago looking for evidence of the fire complained that there was little to see. Within 20 years, Chicago’s population tripled, to 1 million. And by the end of the century, the fire-flattened business district sprouted scores of buildings taller than you could find anywhere else in the world. Their unprecedented height earned these structures a new name: skyscraper.

The Chicago fire enabled the rise of skyscrapers in three major ways. First, it made land available for new buildings. The fire may have destroyed the business district, but the railway system remained intact, creating ideal conditions for new construction. So much capital flowed into Chicago that downtown real-estate prices actually rose in the first 12 months after the fire. “The 1871 fire wiped out the rich business heart of the city, and so there was lots of money and motivation to rebuild immediately,” Julius L. Jones, an assistant curator at the Chicago History Museum, told me. “It might have been different if the fire had just wiped out poor areas and left the banks and business offices alone.” What’s more, he said, the city used the debris from the fire to extend the shoreline into Lake Michigan and create more land.

Second, a combination of regulatory and technological developments changed what Chicago was made of. Insurance companies and city governments mandated fire-resistant construction. At first, Chicago rebuilt with brick, stone, iron. But over time, the urge to create a fireproof city in an environment of escalating real-estate prices pushed architects and builders to experiment with steel, a material made newly affordable by recent innovations. Steel-skeleton frames not only offered more protection from fire; they also supported more weight, allowing buildings to grow taller.

Third, and most important, post-fire reconstruction brought together a cluster of young architects who ultimately competed with one another to build higher and higher. In the simplest rendition of this story, the visionary architect William Le Baron Jenney masterminded the construction of what is considered history’s first skyscraper, the 138-foot-tall Home Insurance Building, which opened in 1885. But the skyscraper’s invention was a team effort, with Jenney serving as a kind of player-coach. In 1882, Jenney’s apprentice, Daniel Burnham, had collaborated with another architect, John Root, to design the 130-foot-tall Montauk Building, which was the first high steel building to open in Chicago. Another Jenney protégé, Louis Sullivan, along with Dankmar Adler, designed the 135-foot-tall Wainwright Building, the first skyscraper in St. Louis. Years later, Ayn Rand would base The Fountainhead on a fictionalized version of Sullivan and his protégé, Frank Lloyd Wright. It is a false narrative: “Sullivan and Wright are depicted as lone eagles, paragons of rugged individualism,” Edward Glaeser wrote in Triumph of the City. “They weren’t. They were great architects deeply enmeshed in an urban chain of innovation.”

It is impossible to know just how much cities everywhere have benefited from Chicago’s successful experiments in steel-skeleton construction. By enabling developers to add great amounts of floor space without needing additional ground area, the skyscraper has encouraged density. Finding ways to safely fit more people into cities has led to a faster pace of innovation, greater retail experimentation, and more opportunities for middle- and low-income families to live near business hubs. People in dense areas also own fewer cars and burn hundreds of gallons less gasoline each year than people in nonurban areas. Ecologically and economically, and in terms of equity and opportunity, the skyscraper, forged in the architectural milieu of post-fire Chicago, is one of the most triumphant inventions in urban history.

Taming the Steampunk Jungle

March 10, 1888, was a gorgeous Saturday in New York City. Walt Whitman, the staff poet at The New York Herald, used the weekend to mark the end of winter: “Forth from its sunny nook of shelter’d grass—innocent, golden, calm as the dawn / The spring’s first dandelion shows its trustful face.” On Saturday evening, the city’s meteorologist, known lovingly as the “weather prophet” to local newspapers, predicted more fair weather followed by a spot of rain. Then the weather prophet went home and took Sunday off.

Meanwhile, two storms converged. From the Gulf of Mexico, a shelf of dark clouds soaked with moisture crept north. And from the Great Lakes, a cold front that had already smothered Minnesota with snow rolled east. The fronts collided over New York City.

Residents awoke on Monday, the day Whitman’s poem was published, to the worst blizzard in U.S. history. By Thursday morning, the storm had dumped more than 50 inches of snow in parts of the Northeast. Snowdrifts were blown into formations 50 feet high. Food deliveries were suspended, and mothers ran short on milk. Hundreds died of exposure and starvation. Like the Lisbon earthquake more than a century before, the blizzard of 1888 was not just a natural disaster; it was also a psychological blow. The great machine of New York seized up and went silent. Its nascent electrical system failed. Industries stopped operating.

The New York now buried under snow had been a steampunk jungle. Elevated trains clang-clanged through neighborhoods; along the streets, electrical wires looped and drooped from thousands of poles. Yet 20 years after the storm, the trains and wires had mostly vanished—at least so far as anyone aboveground could see. To protect its most important elements of infrastructure from the weather, New York realized, it had to put them underground.

First, New York buried the wires. In early 1889, telegraph, telephone, and utility companies were given 90 days to get rid of all their visible infrastructure. New York’s industrial forest of utility poles was cleared, allowing some residents to see the street outside their windows for the first time. Underground conduits proved cheaper to maintain, and they could fit more bandwidth, which ultimately meant more telephones and more electricity.

Second, and even more important, New York buried its elevated trains, creating the country’s most famous subway system. “An underground rapid transit system would have done what the elevated trains could not do,” The New York Times had written in the days after the blizzard, blasting “the inadequacy of the elevated railroad system to such an emergency.” Even without a blizzard, as Doug Most details in The Race Underground, New York’s streets were becoming impassable scrums of pedestrians, trolleys, horses, and carriages. The year before the blizzard, the elevated rails saw an increase of 13 million passengers. The need for some alternative—and likely subterranean—form of transportation was obvious. London had opened the first part of its subway system several decades earlier. In New York, the 1888 blizzard was the trigger.

Finding Our Inner Chadwick

Not all calamities summon forth the better angels of our nature. A complete survey of urban disasters might show something closer to the opposite: “Status-quo bias” can prove more powerful than the need for urgent change. As U.S. manufacturing jobs declined in the latter half of the 20th century, cities like Detroit and Youngstown, Ohio, fell into disrepair, as leaders failed to anticipate what the transition to a postindustrial future would require. When business districts are destroyed—as in Chicago in 1871—an influx of capital may save the day. But when the urban victims are poor or minorities, post-crisis rebuilding can be slow, if it happens at all. Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans in 2005 and displaced countless low-income residents, many of whom never returned.

The response to COVID-19 could be far-reaching. The greatest lesson of the outbreak may be that modern cities are inadequately designed to keep us safe, not only from coronaviruses, but from other forms of infectious disease and from environmental conditions, such as pollution (which contributes to illness) and overcrowding (which contributes to the spread of illness). What if we designed a city with a greater awareness of all threats to our health?

City leaders could redesign cities to save lives in two ways. First, they could clamp down on automotive traffic. While that may seem far afield from the current pandemic, long-term exposure to pollution from cars and trucks causes more than 50,000 premature deaths a year in the United States, according to a 2013 study. Respiratory conditions aggravated by pollution can increase vulnerability to other illnesses, including infectious ones. The pandemic shutdowns have shown us what an alternative urban future might look like. Cities could remove most cars from downtown areas and give these streets back to the people. In the short term, this would serve our pandemic-fighting efforts by giving restaurants and bars more outdoor space. In the long term, it would transform cities for the better—adding significantly more room for walkers and bicycle lanes, and making the urban way of life more healthy and attractive.

Second, cities could fundamentally rethink the design and uses of modern buildings. Future pandemics caused by airborne viruses are inevitable—East Asia has had several this century, already—yet too many modern buildings achieve energy efficiency by sealing off outside air, thus creating the perfect petri dish for any disease that thrives in unventilated interiors. Local governments should update ventilation standards to make offices less dangerous.

Further, as more Americans work remotely to avoid crowded trains and poorly ventilated offices, local governments should also encourage developers to turn vacant buildings into apartment complexes, through new zoning laws and tax credits. Converting empty offices into apartments would add more housing in rich cities with a shortage of affordable places to live, expand the tax base, and further reduce driving by letting more families make their homes downtown.

Altogether, this is a vision of a 21st-century city remade with public health in mind, achieving the neat trick of being both more populated and more capacious. An urban world with half as many cars would be a triumph. Indoor office and retail space would become less valuable, outdoor space would become more essential, and city streets would be reclaimed by the people. ~

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/10/how-disaster-shaped-the-modern-city/615484/

Mary:

As for catastrophe sometimes bringing positive changes...it makes sense, because catastrophe interrupts the usual and habitual, and thus makes it very visible and subject to question. If we can't do what we always did, can't expect the world to continue as it was, we have to make adjustments. Those adjustments can be the seeds of greater changes, of solutions to old problems and even problems we didn't know were problems.

We won't make it past this pandemic without change, some temporary but some that may be permanent. I think we will not only lose a lot of small businesses and restaurants, but some industries may even disappear completely. Like Cruise ships..those exercises in indulgence that have become prisons full of sick passengers and crew, longing to get home.

Air travel, vacations, how we work all may undergo profound changes in directions still not perfectly clear. Virtual health care, virtual meetings and forums are still pretty new, but already widely used. One thing we know for sure, we'll never get back to the pre-pandemic norms. The future will be different, surprising, and hopefully better for us all.

Oriana:

I mourn the loss of personal contact, the "human touch." And yet I'm willing to mask my face beyond the official end of the pandemic -- it makes sense, since respiratory pathogens are constantly around, and a new pandemic is only a matter of when, not if. Oh those smart Asians who showed us the way with masks (the most effective prevention).

*

THE SKIN MICROBIOME: SHOULD WE SHOWER LESS?

James Hamblin is tired of being asked if he's smelly.

Hamblin, a physician and health reporter, has been fielding the question since 2016, when the article he wrote about his decision to stop showering went viral. The piece outlines compelling reasons why one might want to spend less time sudsing up: Cosmetic products are expensive, showering uses a lot of water, and the whole process takes up valuable time.

Perhaps most importantly, bathing disrupts our skin's microbiome: the delicate ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, mites and viruses that live on (and in) our body's largest organ. Most of these microbes are thought to be benign freeloaders; they feast on our sweat and oils without impacting our health. A small number cause harmful effects, ranging in severity from an irksome itch to a life-threatening infection. And some help us out by, for example, preventing more dangerous species from taking up residence.

Researchers are in the early days of developing the full picture of just how substantially this diverse living envelope influences our overall health, and many of their findings suggest that the microbes on our skin are even more important than was previously understood. Skin has long been considered to be our first line of defense against pathogens, but new studies suggest that the initial protection may come from the microbes that live on its surface.

Meanwhile, the health care and cosmetics industries are already at work developing new categories of "prebiotic" treatments and skin care products that claim to cultivate our skin's population of beneficial microbes and banish the troublemakers.

Hamblin's new book, Clean: The New Science of Skin, is a documentary survey of this pre-dawn moment in our understanding of the skin microbiome. Hamblin spoke with people from a wide range of specialized perspectives: a collector of historic soap advertisements, the dewy-cheeked megafans of a minimalist cosmetics brand, several CEOs, many types of scientists, including a "disgustologist," and the founder of a style of addiction recovery treatment centered on the therapeutic potential of human touch.

But, Hamblin says, most of the time when people learn that he hasn't showered in five years, they just want to know if he stinks. He dutifully explains that he still washes his hands with soap frequently, occasionally wets his hair to get rid of bedhead and rinses off any time he's visibly dirty. But he finds the question tiresome — and also revealing.

"We've gotten a lot better, culturally, about not judging people about all kinds of things, but when people smell or don't use deodorant, somehow it's OK to say, 'You're gross' or 'Stay away from me!' and it gets a laugh," he says. "I'm trying to push back against the sense of there being some universal standard of normalcy."

We spoke to Hamblin, who is a staff writer and the co-host of the podcast Social Distance for The Atlantic, about the benefits and social dynamics of showering less, and the coming wave of microbially-optimized cosmetics.

Your book sets out to challenge some cultural norms about hygiene. What types of cleansing do you think are overdue for reexamination, and which are critical?

There's a distinction between "hygiene" and "cleansing rituals" that's especially important in this moment. "Hygiene" is the more scientific or public health term, where you're really talking about disease avoidance or disease prevention behaviors. Removal of mucus, vomit, blood feces ... any behavior that signals to people "I am thoughtful about not transmitting diseases to you, and I'm a safe person to be around." That would include hand-washing, brushing your teeth, cleaning of open wounds, even mask-wearing. I don't think any of that stuff is due for questioning.

But a lot of the other things that we do are class and wealth signifiers — like combing your hair or whitening your teeth or wearing deodorant — which actually have nothing to do with disease avoidance or disease transmission. They're really much more of a personal or cultural preference. And that's where people are experimenting with doing less.

Why do you think that some of these cultural practices deserve to be reexamined?

So many reasons. We're spending a lot of money (or at least we were pre-pandemic, I don't have new data) on products and practices in this enormous industry-complex of self-care, skin care, hygiene and cosmetics — which is barely regulated, which is a huge and important part of people's daily lives, which people worry a lot about, which people get a lot of joy from, which people bond over, which people judge, and which causes a lot environmental impacts in terms of water and plastic.

And there's the emerging science of the skin microbiome. Being clean [has historically] meant removing microbes from ourselves, so it's an important moment to try to clarify what, exactly, we're trying to do when we're doing the hygiene behaviors.

Some people are misconstruing the central thesis of your book as "shower less like I did." And that's not what you're advocating.

So is there a thesis statement or call to action in your mind?

I think that many people — not everyone — could do less, if they wanted to. We are told by marketing, and by some traditions passed down, that it's necessary to do more than it actually is. Your health will not suffer. And your body is not so disgusting that you need to upend your microbial ecosystem every day.

If you could get by doing less without suffering social or professional consequences, and [your routine] isn't bringing you any value or health benefit, that's the space where I say, "Why not? Why not try it out?"

You wrote that you think we're at the edge of a radical reconception of what it means to be clean. What do you mean by that?

That's harder to answer now because I don't know how the current moment is going to change things. But I believe there's a shift in the very near future upon us, similar to what we saw with the gut microbiome.

Twenty years ago, the idea of kombucha, and probiotics, and trying to have a healthy biome in your gut were really fringe hippie concepts. And now we're doing clinical trials of fecal transplants. It's very mainstream to think about your microbiome. People are being more conscious about things like antibiotic overuse because they don't want to potentially disrupt the gut microbiome. That has been a really radical shift.

And something like that [for] the skin would be even more radical in terms of the effect on our daily lives, and consumer behaviors and spending, because a lot of what has been done traditionally [in terms of hygiene] is predicated on eradicating microbes.

After reading your book, I'm bracing myself for an avalanche of new probiotic and prebiotic cleansing products to hit shelves in the near future. What do you think the average consumer should know as they evaluate whether or not a product is likely to be useful?

Well, if things like acne, eczema and psoriasis are the result of an interplay between your immune system and the microbes on your skin, it is, indeed, scientifically a very promising and cool hypothesis to think that we can shift that microbiome and help people through their flares or outbreaks. That science is supersound.

But if it's possible that we can [use products to] make things better, then it's possible we can make things worse. If a product does meaningfully shift your biome, then it has the capacity to create effects that you didn't want.

We're really riding a fine line between drugs and beauty products here, which makes it very hard for consumers to know.

What's the danger of that fine line?

Most likely these products are not doing anything. Because there's so little regulatory oversight on this type of product, we don't even know for sure that they contain what they claim to contain. And if they were significantly changing your skin microbes, I would want to be extremely careful that there was indeed evidence to back up that that change was good and worth making.

I think a lot of people buy products like this thinking, "It can't hurt, right?" And I would suggest keeping in mind that if something can help, that it can hurt.

So just because scientists are learning that the microbiome might be important for our health, the solution to skin problems is not necessarily "go to the drugstore and buy a probiotic shampoo."

I think that's a great takeaway. And actually, I think we are too culturally inclined to seek topical solutions most of the time. I certainly have been. The skin is very often an external manifestation of our overall health. Very rarely is something limited to the skin.

Everyone has experienced that when you're stressed out, not eating well, haven't exercised, not sleeping, you look — and quite possibly smell — worse than at other times. And our inclination is to go seek a product to cover that up. Sometimes that's the only course of action.

But in an ideal world, we would be able to take that as a sign that something was off, and needed attention in our overall approach to health. We can miss important signals when our immediate inclination is to go find a product to cover things up.

How did your identity as a cisgendered white male influence your reporting on this subject?

Probably one of the main reasons I've been able to go so long without using [shampoo and deodorant] is because of the privilege of my position in American society. To the degree that these standards are culturally determined, I am coming from the group that has created these norms. That is why I believe I was able to push against them without more discriminatory consequences. I mean, people call me "gross." But I didn't suffer professionally to my knowledge. And other people would have.

I'm not telling anyone that they should do less, basically. I'm only trying to understand why we do the things that we do.

Where do you stand on the most controversial question on the Internet: washing your legs in the shower?

Personal preference. From a scientific hygiene perspective, it's an elective practice. It might be something people enjoy doing or feel better for having done. If it brings you value, then it's absolutely worth doing. ~

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/09/26/917019912/in-the-era-of-hygiene-clean-author-makes-the-case-for-showering-less

*

ROBERT WRIGHT: THE EVOLUTION OF RELIGION

~ According to Wright’s theory, although religion may seem otherworldly—a realm of revelation and spirituality—its history has, like that of much else, been driven by mundane “facts on the ground.” Religion, that is, changes through time primarily because it responds to changing circumstances in the real world: economics, politics, and war. Like organisms, religions respond adaptively to the world.

As technologies, particularly transportation, improved throughout history, cultures collided and human beings encountered more and more of these non-zero-sum opportunities. Religion, Wright says, responded rationally to these encounters. For example, religious doctrine grew more tolerant of other faiths when tolerance helped smooth economic or political interactions that were potentially win-win: it’s wise to respect the other fellow’s gods when you want to trade or form military alliances with him. ~ (I’ve lost the link, but thought this nugget is worth mulling over.)

*

THE PROBLEMS WITH “BE NOT AFRAID”

~ The brand of Christianity to which my family, neighbors, and co-workers all belong disparages all emotional extremes save for those that make the faith look like it’s doing what they were told it would do.

For example, ambition isn’t good because it means you think you’re all that—I mean without God—and that’s not okay. Sadness can’t be validated beyond a certain threshold, either, because above that line you must not be believing hard enough. Depression is downright inexcusable for a child of God because he or she is indwelled by the Holy Spirit. If he’s not comforting you, it must mean you are doing something wrong. Either way, it’s your fault.

The same goes for fear. I have been warning people about this virus since late February, but my concerns kept getting minimized or dismissed by those within earshot. One of the refrains I’ve heard from them again and again is that God is in control, so when we allow fear to overtake us, it demonstrates a failure on our part to have faith.

Illicit Emotions

For nearly a decade now, I’ve debated with fellow skeptics about the functional value of religion in general. Traditionally, I’ve sided with those who acknowledge that religion serves social and psychological functions so central to the human psyche that if you were to eradicate every religion known to humankind from the face of the planet, several new ones would immediately show up to take their place.

I think we are wired by our history to want something like religion. Some find more sophisticated versions of each religion from which to derive their values, which helps a little, but even then there are still downsides to each religion. For example, the evangelical Christian faith of my youth generally disapproves of a wide spectrum of natural (and useful!) human emotions, and that is a problem since emotions are what motivate people to action, and sometimes action is what’s needed, not prayer.

When a pandemic arrives, for example, and you are convinced an Invisible Protector will maintain his control of events no matter how far afield the world begins to veer, you learn to stuff those illicit feelings deep down inside. The moment they begin to surface, something kicks in that shuts off the most extreme emotions within an evangelical Christian. You can sometimes see it move across their faces when it happens. I remember doing the same thing myself back when I was still a believer, but now it just seems unhealthy to me looking in from the outside.