Dali: Marilyn-Mao, 1972, self-portrait with photomontage by Philippe Halsman.

Dali: Marilyn-Mao, 1972, self-portrait with photomontage by Philippe Halsman. EMPIRE OF DREAMS

On the first page of my dreambook

It’s always evening

In an occupied country.

Hour before the curfew.

A small provincial city.

The houses all dark.

The storefronts gutted.

I am on a street corner

Where I shouldn’t be.

Alone and coatless

I have gone out to look

For a black dog who answers to my whistle.

I have a kind of Halloween mask

Which I am afraid to put on.

~ Charles Simic

*

Simic’s Serbian name is Dušan (Doo-shahn — “soulful.” In Slavic languages, “dusha” means soul)

from Wiki: “Dušan Simić was born in Belgrade. In his early childhood, during World War II, he and his family were forced to evacuate their home several times to escape indiscriminate bombing of Belgrade. Growing up as a child in war-torn Europe shaped much of his world-view, Simic states. In an interview from the Cortland Review he said, "Being one of the millions of displaced persons made an impression on me. In addition to my own little story of bad luck, I heard plenty of others. I'm still amazed by all the vileness and stupidity I witnessed in my life."

Simic immigrated to the United States with his brother and mother in order to join his father in 1954 when he was sixteen. He grew up in Chicago."

Oriana:

Our early years may have a strange persistence in our dreams. In my current life, I'm always home; in my dreams, I'm never home. In dreams I've lost my home and my way back to it, repeating my leaving Poland and becoming a stranger in a strange land.

For Simic, it’s “always an evening / in an occupied country. / Hour before the curfew.” He’s split in two: a successful American poet and college professor by day, and, in his dreams, the scared child in an occupied country.” I know something of that . . . the fear, the trauma of losing “home” in the deepest sense — the loss of the familiar.

I keenly remember Simic’s remark about a book on world history — “Could there be a more obscene text?”

*

(a shameless digression: This morning I had a dream about being on a dusky-looking college campus somewhere in Anaheim [known for Disneyland, not academic institutions]. My intention is to enroll in a Ph.D. program, and I've come to check out the library — since I must like the library if I am to enroll. In my hand I'm holding a book, “The Goddesses in Homer” — and I'm looking forward to reading it. The heaven of intellectual stimulation awaits! I wake up happy.)

*

“I feel like I’ve swallowed a cloudy sky.” ~ Haruki Murakami, Sputnik Sweetheart

*

WORDSWORTH AS THE SPIRIT OF THE AGE

~ “Poetry makes nothing happen,” wrote W. H. Auden in his poem on the death of fellow poet W. B. Yeats. He was wrong. Sometimes poetry can change the world.

William Wordsworth was not merely the most admired English poet of the 19th century: his poetry made many things happen. Locally, the ecology and economy of the vale of Grasmere, and the wider Lake District, were changed as a result of his canonization. Nationally, he made new claims for the power of poetry that shaped the minds of the most influential thinkers in Victorian Britain. Globally, his influence extended to John Muir’s passion for the preservation of Yosemite.

Auden did not in fact believe that poetry makes nothing happen. Poets often disagree with themselves, which is one of the things that makes them poets. Having said that poetry makes nothing happen, he went on, later in the same poem, to describe poetry as “A way of happening, a mouth.”

Wordsworth’s poetry was a way of happening because of the new way in which he sought, as Keats put it, to “think into the human heart” by means of an unprecedented examination of the development of his own mind and his sense of belonging in the world. He became the mouth of his generation for what Keats called “the true voice of feeling.”

In Victorian England, and simultaneously in the young United States of America, Wordsworth came to be regarded as a central figure in the revolutionary shift in cultural attitudes that would eventually be called the Romantic movement. He and his fellow poets and philosophers changed forever the way we think about childhood, about the sense of the self, about the purpose of poetry, and especially about our connection to our surroundings.

Hazlitt believed that Wordsworth and Coleridge embodied the spirit of the age. Their imaginative cross-fertilization made them into, to adapt a phrase of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s, a composite “representative man.” Among the “great men” of his own time, Emerson regarded Napoleon as the archetypal “man of the world,” the “representative of the popular external life and aims of the 19th century,” and Goethe as the philosopher of the “multiplicity” of its inner life.

Yet Emerson’s own capacious mind and his vision for American literature were shaped less by Goethe than by the poetry of Wordsworth and the ideas of Coleridge. The composite Wordsworthian–Coleridgean identity began to fracture on that morning of Saturday, December 27th, 1806 when Coleridge saw, or thought he saw, Wordsworth in bed with Sara Hutchinson.

It broke down almost irretrievably after Basil Montagu passed on the gossip about Wordsworth finding Coleridge impossible to live with because of the alcohol and the opium. Though Coleridge would be generous in writing of Wordsworth’s gifts in Biographia Literaria, and Wordsworth would mourn Coleridge’s passing in the “Extempore Effusion on the Death of James Hogg,” it would never be glad confident morning again.

As he settled into fame and a gentleman’s life at Rydal Mount, Wordsworth’s genius deserted him. Yet as his mortal powers waned, he began to achieve immortality: his spirit lived on by means of his inspiration upon the next generation of readers and writers, then far beyond. To use another phrase of W. H. Auden’s in his elegy on the death of W. B. Yeats, Wordsworth became his admirers.

Radical Wordsworth endured through the 19th century in the poetry of Keats and Shelley, John Clare and Felicia Hemans (and, by negative influence, Byron); in the art of Benjamin Robert Haydon and the prose of Thomas De Quincey, William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb; in the ideas of John Stuart Mill, Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin and George Eliot; in the deeds of Canon Rawnsley, Stopford Brooke and Beatrix Potter; and, across the Atlantic, in the visions of Emerson, Thoreau and John Muir.

Radical Wordsworth survives today whenever a person walks for pleasure and takes spiritual refreshment in the mountains or when a heart leaps up at the sight of a rainbow in the sky or a tuft of primroses in flower.

*

Thirty years after Wordsworth’s death, and twenty after the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Matthew Arnold recognized which way the wind had blown. Introducing an anthology of The English Poets, he argued, under the deep influence of Wordsworth, that the future spirit of humankind would depend on poetry. Religion had relied on supposed fact; the science of Lyell, Darwin and others had disproved those facts.

The only part of religion to endure would be “its unconscious poetry.” More and more, society would “have to turn to poetry to interpret life for us, to console us, to sustain us”: “Most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry.” Even science itself would appear incomplete without it, “For finely and truly does Wordsworth call poetry ‘the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all science’; and what is a countenance without its expression?”

Arnold’s prose then takes off from another phrase in the preface to Lyrical Ballads:

'Again, Wordsworth finely and truly calls poetry “the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge”; our religion, parading evidences such as those on which the popular mind relies now; our philosophy, pluming itself on its reasonings about causation and finite and infinite being; what are they but the shadows and dreams and false shows of knowledge?

The day will come when we shall wonder at ourselves for having trusted to them, for having taken them seriously; and the more we perceive their hollowness, the more we shall prize “the breath and finer spirit of knowledge” offered to us by poetry . . . the best poetry will be found to have a power of forming, sustaining, and delighting us, as nothing else can.'

Out of Wordsworth comes a manifesto for the enduring value of poetry beyond even that of religion, philosophy and science. There was an unprecedented market for biography in the Victorian era. A notably popular series of literary lives, published by Macmillan under the editorship of the prolific journalist- politician-bookman John Morley, was called “English Men of Letters.”

The volume on Wordsworth was published in 1881, the year after Arnold’s essay on the importance of poetry. It made the startling claim that “the maxims of Wordsworth’s form of natural religion were uttered before Wordsworth only in the sense in which the maxims of Christianity were uttered before Christ”:

The essential spirit of the Lines near Tintern Abbey was for practical purposes as new to mankind as the essential spirit of the Sermon on the Mount. Not the isolated expression of moral ideas, but their fusion into a whole in one memorable personality, is that which connects them for ever with a single name. Therefore it is that Wordsworth is venerated; because to so many men—indifferent, it may be, to literary or poetical effects, as such — he has shown by the subtle intensity of his own emotion how the contemplation of Nature can be made a revealing agency, like Love or Prayer — an opening, if indeed there be any opening, into the transcendent world.

Thirty years after his death, the poet from an obscure nook of northern England, who in the first half of his life was mercilessly derided by the critics, was being compared to Jesus Christ.”

*

“WHATEVER IT IS YOU'RE SEEKING

WON'T COME IN THE FORM YOU'RE EXPECTING.” ~ Haruki Murakami

~ if it comes at all. It seems that nothing in life happens the way we were expecting it to happen. I guess it’s like a writer preparing an elaborate plot of a novel, and then the “characters become alive and take over — start saying and doing things not in the original plan.” And that’s just a novel — and all we need to know is that writing comes from the unconscious — of course we don’t control it! Life comes from everywhere (including “out of the blue”), wild, unpredictable, wonderfully or shockingly surprising.

“When the student is ready, the teacher will come” — never happened to me — unless I start thinking in terms of a “different form.” Then the encounter with the poetry of Rilke could be said to have been that teacher. Otherwise, waiting for a mentor has been in the same category as “one day my Prince will come.”

And now I'm dealing with the knee replacement surgery not having turned out to be the way I expected. This is not minor, since it’s about the ability to walk and the long-awaited freedom from chronic pain — and that “last dance” that life was supposed to become. A beautiful waltz, a soulful tango through the streets of old Europe (ah, my travel plans! so many stairways and bridges!).

So, it won’t be a dance — or else it will be something I recognize as a dance only later — a different kind of dance. The strangeness of it all. At least I finally know better than to try to predict. But the brain never rests, and parallel lives happen inside our head like parallel universes.

So, this constant annihilation of the imagined future . . . with something entirely different emerging instead. This should make Buddhists of us all, free of expectations, living in the present . . . I wonder if we ever achieve such purity.

*

The first half of life is particularly charged with “waiting for life to happen.” Rilke has an unusual poem called “Remembrance.” The first stanza describes this waiting:

And you wait, keep waiting for that one thing

which would infinitely enrich your life:

the powerful, the unique and uncommon,

the awakening of sleeping stones —

depths that would reveal you to yourself.

And then the speaker learns that the “one thing” has already happened — but it was several things — love, travel, work — life itself has happened while we were ostensibly living it, but in some depths still waiting for our “real life.”

Haruki Murakami with his cat, Kafka

Haruki Murakami with his cat, Kafka *

“We don't want to live a frivolous life, we don't want to live a superficial life. We want to be serious with each other, with our friends, with our work. That doesn't necessarily mean gloomy or grim, but seriousness has a kind of voluptuous aspect to it. It is something that we are deeply hungry for, to take ourselves seriously and to be able to enjoy the nourishment of seriousness, that gravity, that weight.” ~ Leonard Cohen

Oriana:

It’s an interesting insight — we don't want a frivolous life; we want seriousness. Seriousness nourishes us — a dedication to a cause, just the right amount of idealism (extreme idealism tends to end in catastrophic evil).

And perhaps the most interesting thing that Cohen is saying here is that “seriousness has a kind of voluptuous aspect to it.” It’s profoundly satisfying.

*

“It seems to me now that the plain state of being human is dramatic enough for anyone; you don't need to be a heroin addict or a performance poet to experience extremity. You just have to love someone.” ~ Nick Hornby

Oriana:

Yes, that's guaranteed unpredictability. "Now the storm begins."

Or at least that is so with new love. Long-term love is closer to contentment and tenderness.

Calla lilies; Robert Mapplethorpe

Calla lilies; Robert Mapplethorpe*

A CONTROVERSIAL RUSSIAN THEORY CLAIMS FORESTS DON’T JUST MAKE RAIN—THEY MAKE WIND

~ It is simple physics with far-reaching consequences, describing how water vapor exhaled by trees drives winds: winds that cross the continent, taking moist air from Europe, through Siberia, and on into Mongolia and China; winds that deliver rains that keep the giant rivers of eastern Siberia flowing; winds that water China’s northern plain, the breadbasket of the most populous nation on Earth.

With their ability to soak up carbon dioxide and breathe out oxygen, the world’s great forests are often referred to as the planet’s lungs. But Nastassia Makarieva and Victor Gorshkov, who died last year, say they are its beating heart, too.

“Forests are complex self-sustaining rainmaking systems, and the major driver of atmospheric circulation on Earth,” Makarieva says. They recycle vast amounts of moisture into the air and, in the process, also whip up winds that pump that water around the world. The first part of that idea—forests as rainmakers—originated with other scientists and is increasingly appreciated by water resource managers in a world of rampant deforestation. But the second part, a theory Makarieva calls the biotic pump, is far more controversial.

If correct, the idea could help explain why, despite their distance from the oceans, the remote interiors of forested continents receive as much rain as the coasts—and why the interiors of unforested continents tend to be arid. It also implies that forests from the Russian taiga to the Amazon rainforest don’t just grow where the weather is right. They also make the weather. “All I have learned so far suggests to me that the biotic pump is correct,” says Douglas Sheil, a forest ecologist at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. With the future of the world’s forests in doubt, “Even if we thought the theory had only a small chance of being true, it would be profoundly important to know one way or the other.”

Many meteorology textbooks still teach a caricature of the water cycle, with ocean evaporation responsible for most of the atmospheric moisture that condenses in clouds and falls as rain. The picture ignores the role of vegetation and, in particular, trees, which act like giant water fountains. Their roots capture water from the soil for photosynthesis, and microscopic pores in leaves release unused water as vapor into the air. The process, the arboreal equivalent of sweating, is known as transpiration. In this way, a single mature tree can release hundreds of liters of water a day. With its foliage offering abundant surface area for the exchange, a forest can often deliver more moisture to the air than evaporation from a water body of the same size.

The biotic pump theory suggests forests not only make rain, but also wind. When water vapor over coastal forests condenses, it lowers air pressures, creating winds that draw in moist ocean air. Cycles of transpiration and condensation can set up winds that deliver rains thousands of kilometers inland.

The importance of this recycled moisture for nourishing rains was largely disregarded until 1979, when Brazilian meteorologist Eneas Salati reported studies of the isotopic composition of rainwater sampled from the Amazon Basin. Water recycled by transpiration contains more molecules with the heavy oxygen-18 isotope than water evaporated from the ocean. Salati used this fact to show that half of the rainfall over the Amazon came from the transpiration of the forest itself.

By this time, meteorologists were tracking an atmospheric jet above the forest, at a height of about 1.5 kilometers. Known as the South American Low-Level Jet, the winds blow east to west across the Amazon, about as fast as a racing bike, before the Andes Mountains divert them south. Salati and others surmised the jet carried much of the transpired moisture, and dubbed it a “flying river.” The Amazon flying river is now reckoned to carry as much water as the giant terrestrial river below it, says Antonio Nobre, a climate researcher at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research.

For some years, flying rivers were thought to be limited to the Amazon. In the 1990s, Hubert Savenije, a hydrologist at the Delft University of Technology, began to study moisture recycling in West Africa. Using a hydrological model based on weather data, he found that, as one moved inland from the coast, the proportion of the rainfall that came from forests grew, reaching 90% in the interior. The finding helped explain why the interior Sahel region became dryer as coastal forests disappeared over the past half-century.

Globally, 40% of all precipitation comes from the land rather than the ocean. Often it is more. The Amazon’s flying river provides 70% of the rain falling in the Río de la Plata Basin, which stretches across southeastern South America. Van der Ent was most surprised to find that China gets 80% of its water from the west, mostly Atlantic moisture recycled by the boreal forests of Scandinavia and Russia. The journey involves several stages—cycles of transpiration followed by downwind rain and subsequent transpiration—and takes 6 months or more. “It contradicted previous knowledge that you learn in high school,” he says. “China is next to an ocean, the Pacific, yet most of its rainfall is moisture recycled from land far to the west.”

Even those who doubt the theory agree that forest loss can have far-reaching climatic consequences. Many scientists have argued that deforestation thousands of years ago was to blame for desertification in the Australian Outback and West Africa. The fear is that future deforestation could dry up other regions, for example, tipping parts of the Amazon rainforest to savanna. Agricultural regions of China, the African Sahel, and the Argentine Pampas are also at risk, says Patrick Keys, an atmospheric chemist at Colorado State University, Fort Collins.

In 2018, Keys and his colleagues used a model, similar to van der Ent’s, to track the sources of rainfall for 29 global megacities. He found that 19 were highly dependent on distant forests for much of their water supply, including Karachi, Pakistan; Wuhan and Shanghai, China; and New Delhi and Kolkata, India. “Even small changes in precipitation arising from upwind land-use change could have big impacts on the fragility of urban water supplies,” he says.

Some modeling even suggests that by removing a moisture source, deforestation could alter weather patterns beyond the paths of flying rivers. Just as El Niño, a shift in currents and winds in the tropical Pacific Ocean, is known to influence weather in faraway places through “teleconnections,” so, too, could Amazon deforestation diminish rainfall in the U.S. Midwest and snowpack in the Sierra Nevada, says Roni Avissar, a climatologist at the University of Miami who has modeled such teleconnections. Far-fetched? “Not at all,” he says. “We know El Niño can do this, because unlike deforestation, it recurs and we can see the pattern. Both are caused by small changes in temperature and moisture that project into the atmosphere.”

Two years ago, at a meeting of the United Nations Forum on Forests, a high-level policy group on which all governments sit, David Ellison, a land researcher at the University of Bern, presented a case in point: a study showing that as much as 40% of the total rainfall in the Ethiopian highlands, the main source of the Nile, is provided by moisture recycled from the forests of the Congo Basin. Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia are negotiating a long-overdue deal on sharing the waters of the Nile. But such an agreement would be worthless if deforestation in the Congo Basin, far from those three nations, dries up the moisture source, Ellison suggested. “Interactions between forests and water have been almost entirely ignored in the management of global freshwater resources.”

The biotic pump would raise the stakes even further, with its suggestion that forest loss alters not just moisture sources, but also wind patterns. The theory, if correct, would have “crucial implications for planetary air circulation patterns,” Ellison warns, especially those that take moist air inland to continental interiors.

Even if Makarieva’s ideas are fringy in the West, they are taking root in Russia. Last year, the government began a public dialogue to revise its forestry laws. Aside from strictly protected areas, Russian forests are open to commercial exploitation, but the government and the Federal Forestry Agency are considering a new designation of “climate protection forests.” “Some representatives of our forest department got impressed by the biotic pump and want to introduce a new category,” she says. The idea has the backing of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Being part of a consensus rather than the perennial outsider marks a change, Makarieva says.

This summer, the coronavirus lockdown put the kibosh on her annual trip to the northern forests. Back in St. Petersburg, she has settled down to respond to yet another round of objections to her work from anonymous peer reviewers. She insists the pump theory will ultimately prevail. “There is a natural inertia in science,” she says. With a dark Russian humor, she invokes the words of the legendary German physicist Max Planck, who is said to have once remarked that science “advances one funeral at a time.” ~

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/06/controversial-russian-theory-claims-forests-don-t-just-make-rain-they-make-wind

My thanks to Mary for having sent me this article.

*

"All the armies in the world can't stop an idea whose time has come." ~ Victor Hugo

*

ASIMOV ON HUMANISM

~ “David Frost said, “Dr. Asimov, do you believe in God?”

And I said, “Whose?”

He said, a little impatiently, “Come, come, Dr. Asimov, you know very well whose. Do you believe in the Western God, the God of the Judeo-Christian tradition?”

Still playing for time, I said, “I haven’t given it much thought.”

Frost said, “I can’t believe that, Dr. Asimov.” He then nailed me to the wall by saying, “Surely a man of your diverse intellectual interests and wide-ranging curiosity must have tried to find God?”

(Eureka! I had it! The very nails had given me my opening!) I said, smiling pleasantly, “God is much more intelligent than I am — let him try to find me . . .”

I certainly don’t believe in the mythologies of our society, in Heaven and Hell, in God and angels, in Satan and demons. I’ve thought of myself as an “atheist,” but that simply described what I didn’t believe in, not what I did.

Gradually, though, I became aware that there was a movement called “humanism,” which used that name because, to put it most simply, Humanists believe that human beings produced the progressive advance of human society and also the ills that plague it. They believe that if the ills are to be alleviated, it is humanity that will have to do the job. They disbelieve in the influence of the supernatural on either the good or the bad of society, on either its ills or the alleviation of those ills.

There is nothing frightening about an eternal dreamless sleep. Surely it is better than eternal torment in Hell and eternal boredom in Heaven. And what if I’m mistaken? The question was asked of Bertrand Russell, the famous mathematician, philosopher, and outspoken atheist. “What if you died,” he was asked, “and found yourself face to face with God? What then?”

And the doughty old champion said, “I would say, ‘Lord, you should have given us more evidence.’” ~

http://www.brainpickings.org/2013/08/13/isaac-asimov-religion-science-humanism/?utm_source=buffer&utm_campaign=Buffer&utm_content=bufferdcc89&utm_medium=twitter

*

*

THE OBESITY ERA — IS IT SOMETHING OUT THERE IN THE ENVIRONMENT?

~ For the first time in human history, overweight people outnumber the underfed, and obesity is widespread in wealthy and poor nations alike. The diseases that obesity makes more likely — diabetes, heart ailments, strokes, kidney failure — are rising fast across the world, and the World Health Organization predicts that they will be the leading causes of death in all countries, even the poorest, within a couple of years. What’s more, the long-term illnesses of the overweight are far more expensive to treat than the infections and accidents for which modern health systems were designed. Obesity threatens individuals with long twilight years of sickness, and health-care systems with bankruptcy.

THE TRADITIONAL EXPLANATION: LACK OF SELF-DISCIPLINE

Moral panic about the depravity of the heavy has seeped into many aspects of life, confusing even the erudite. Earlier this month, for example, the American evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller expressed the zeitgeist in this tweet: ‘Dear obese PhD applicants: if you don’t have the willpower to stop eating carbs, you won’t have the willpower to do a dissertation. #truth.’

So we appear to have a public consensus that excess body weight (defined as a Body Mass Index of 25 or above) and obesity (BMI of 30 or above) are consequences of individual choice. It is undoubtedly true that societies are spending vast amounts of time and money on this idea. It is also true that the masters of the universe in business and government seem attracted to it, perhaps because stern self-discipline is how many of them attained their status. What we don’t know is whether the theory is actually correct.

Yet the scientists who study the biochemistry of fat and the epidemiologists who track weight trends [do not agree]. In fact, many researchers believe that personal gluttony and laziness cannot be the entire explanation for humanity’s global weight gain. As Richard L Atkinson, Emeritus Professor of Medicine and Nutritional Sciences at the University of Wisconsin and editor of the International Journal of Obesity, put it in 2005: ‘The previous belief of many lay people and health professionals that obesity is simply the result of a lack of willpower and an inability to discipline eating habits is no longer defensible.’

OBESOGENS: THE CHEMICALS THAT ALTER METABOLISM

Consider, for example, this troublesome fact, reported in 2010 by the biostatistician David B Allison and his co-authors at the University of Alabama in Birmingham: over the past 20 years or more, as the American people were getting fatter, so were America’s marmosets. As were laboratory macaques, chimpanzees, vervet monkeys and mice, as well as domestic dogs, domestic cats, and domestic and feral rats from both rural and urban areas. In fact, the researchers examined records on those eight species and found that average weight for every one had increased. The marmosets gained an average of nine per cent per decade. Lab mice gained about 11 per cent per decade. Chimps, for some reason, are doing especially badly: their average body weight had risen 35 per cent per decade. Allison, who had been hearing about an unexplained rise in the average weight of lab animals, was nonetheless surprised by the consistency across so many species. ‘Virtually in every population of animals we looked at, that met our criteria, there was the same upward trend,’ he told me.

It isn’t hard to imagine that people who are eating more themselves are giving more to their spoiled pets, or leaving sweeter, fattier garbage for street cats and rodents. But such results don’t explain why the weight gain is also occurring in species that human beings don’t pamper, such as animals in labs, whose diets are strictly controlled. In fact, lab animals’ lives are so precisely watched and measured that the researchers can rule out accidental human influence: records show those creatures gained weight over decades without any significant change in their diet or activities. The trend suggests some widely shared cause, beyond the control of individuals, which is contributing to obesity across many species.

Many other aspects of the worldwide weight gain are also difficult to square with the ‘it’s-just-thermodynamics’ model. In rich nations, obesity is more prevalent in people with less money, education and status. Even in some poor countries, according to a survey published last year in the International Journal of Obesity, increases in weight over time have been concentrated among the least well-off. And the extra weight is unevenly distributed among the sexes, too. In a study published in the Social Science and Medicine journal last year, Wells and his co-authors found that, in a sample that spanned 68 nations, for every two obese men there were three obese women. Moreover, the researchers found that higher levels of female obesity correlated with higher levels of gender inequality in each nation. Why, if body weight is a matter of individual decisions about what to eat, should it be affected by differences in wealth or by relations between the sexes?

A number of researchers have come to believe, as Wells himself wrote earlier this year in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, that ‘all calories are not equal’. The problem with diets that are heavy in meat, fat or sugar is not solely that they pack a lot of calories into food; it is that they alter the biochemistry of fat storage and fat expenditure, tilting the body’s system in favor of fat storage. Wells notes, for example, that sugar, trans-fats and alcohol have all been linked to changes in ‘insulin signaling’, which affects how the body processes carbohydrates. This might sound like a merely technical distinction. In fact, it’s a paradigm shift: if the problem isn’t the number of calories but rather biochemical influences on the body’s fat-making and fat-storage processes, then sheer quantity of food or drink are not the all-controlling determinants of weight gain. If candy’s chemistry tilts you toward fat, then the fact that you eat it at all may be as important as the amount of it you consume.

More importantly, ‘things that alter the body’s fat metabolism’ is a much wider category than food. Sleeplessness and stress, for instance, have been linked to disturbances in the effects of leptin, the hormone that tells the brain that the body has had enough to eat. What other factors might be at work? Viruses, bacteria and industrial chemicals have all entered the sights of obesity research. So have such aspects of modern life as electric light, heat and air conditioning. All of these have been proposed, with some evidence, as direct causes of weight gain: the line of reasoning is not that stress causes you to eat more, but rather that it causes you to gain weight by directly altering the activities of your cells. If some or all of these factors are indeed contributing to the worldwide fattening trend, then the thermodynamic model is wrong.

We are, of course, surrounded by industrial chemicals. According to Frederick vom Saal, professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri, an organic compound called bisphenol-A (or BPA) that is used in many household plastics has the property of altering fat regulation in lab animals. And a recent study by Leonardo Trasande and colleagues at the New York University School of Medicine with a sample size of 2,838 American children and teens found that, for the majority, those with the highest levels of BPA in their urine were five times more likely to be obese than were those with the lowest levels.

It’s also possible that chemical disrupters could affect people’s body chemistry on longer timescales — starting, for instance, before their birth. Contrary to its popular image of serene imperturbability, a developing fetus is in fact acutely sensitive to the environment into which it will be born, and a key source of information about that environment is the nutrition it gets via the umbilical cord. As David J P Barker, professor of clinical epidemiology of the University of Southampton, noted some 20 years ago, where mothers have gone hungry, their offspring are at a greater risk of obesity. The prenatal environment, Barker argued, tunes the children’s metabolism for a life of scarcity, preparing them to store fat whenever they can, to get them through periods of want. If those spells of scarcity never materialize, the child’s proneness to fat storage ceases to be an advantage. The 40,000 babies gestated during Holland’s ‘Hunger Winter’ of 1944-1945 grew up to have more obesity, more diabetes and more heart trouble than their compatriots who developed without the influence of war-induced starvation.

Just to double down on the complexity of the question, a number of researchers also think that industrial compounds might be affecting these signals. For example, Bruce Blumberg, professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California, Irvine, has found that pregnant mice exposed to organotins (tin-based chemical compounds that are used in a wide variety of industries) will have heavier offspring than mice in the same lab who were not so exposed. In other words, the chemicals might be changing the signal that the developing fetus uses to set its metabolism. More disturbingly, there is evidence that this ‘fetal programming’ could last more than one generation. A good predictor of your birth weight, for instance, is your mother’s weight at her birth.

THE “THERMONEUTRAL ZONE”

Lurking behind these prime suspects, there are the fugitive possibilities — what David Allison and another band of co-authors recently called the ‘roads less travelled’ of obesity research. For example, consider the increased control civilization gives people over the temperature of their surroundings. There is a ‘thermoneutral zone’ in which a human body can maintain its normal internal temperature without expending energy. Outside this zone, when it’s hot enough to make you sweat or cold enough to make you shiver, the body has to expend energy to maintain homeostasis. Temperatures above and below the neutral zone have been shown to cause both humans and animals to burn fat, and hotter conditions also have an indirect effect: they make people eat less. A restaurant on a warm day whose air conditioning breaks down will see a sharp decline in sales (yes, someone did a study). Perhaps we are getting fatter in part because our heaters and air conditioners are keeping us in the thermoneutral zone.

DISRUPTION OF THE LIGHT CYCLE

And what about light? A study by Laura Fonken and colleagues at the Ohio State University in Columbus, published in 2010 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reported that mice exposed to extra light (experiencing either no dark at all or a sort of semidarkness instead of total night) put on nearly 50 per cent more weight than mice fed the same diet who lived on a normal night-day cycle of alternating light and dark. This effect might be due to the constant light robbing the rodents of their natural cues about when to eat. Wild mice eat at night, but night-deprived mice might have been eating during the day, at the ‘wrong’ time physiologically. It’s possible that widespread electrification is promoting obesity by making humans eat at night, when our ancestors were asleep.

ADENOVIRUS-36 AND OBESITY-CAUSING GUT BACTERIA

There is also the possibility that obesity could quite literally be contagious. A virus called Ad-36, known for causing eye and respiratory infections in people, also has the curious property of causing weight gain in chickens, rats, mice and monkeys. Of course, it would be unethical to test for this effect on humans, but it is now known that antibodies to the virus are found in a much higher percentage of obese people than in people of normal weight. A research review by Tomohide Yamada and colleagues at the University of Tokyo in Japan, published last year in the journal PLoS One, found that people who had been infected with Ad-36 had significantly higher BMI than those who hadn’t.

As with viruses, so with bacteria. Experiments by Lee Kaplan and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston earlier this year found that bacteria from mice that have lost weight will, when placed in other mice, apparently cause those mice to lose weight, too. And a study in humans by Ruchi Mathur and colleagues at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism earlier this year, found that those who were overweight were more likely than others to have elevated populations of a gut microorganisms called Methanobrevibacter smithii. The researchers speculated that these organisms might in fact be especially good at digesting food, yielding up more nutrients and thus contributing to weight gain.

The researcher who first posited a viral connection in 1992 — he had noticed that the chickens in India that were dead of an adenovirus infection were plump instead of gaunt — was Nikhil Dhurandhar, now a professor at the Pennington Biomedical Research Centre in Louisiana. He has proposed a catchy term for the spread of excess weight via bugs and viruses: ‘infectobesity’.

**

WE SIMPLY DON’T KNOW WHICH FACTOR IS MOST IMPORTANT

Today’s priests of obesity prevention proclaim with confidence and authority that they have the answer. So did Bruno Bettelheim in the 1950s, when he blamed autism on mothers with cold personalities. So, for that matter, did the clerics of 18th-century Lisbon, who blamed earthquakes on people’s sinful ways. History is not kind to authorities whose mistaken dogmas cause unnecessary suffering and pointless effort, while ignoring the real causes of trouble. And the history of the obesity era has yet to be written. ~

https://aeon.co/essays/blaming-individuals-for-obesity-may-be-altogether-wrong

an obese marmoset

an obese marmoset*

WHY IT WAS EASIER TO BE SKINNY IN THE 1980S

A study finds that people today who eat and exercise the same amount as people 20 years ago are still fatter.

~ A 2016 study published in the journal Obesity Research and Clinical Practice found that it’s harder for adults today to maintain the same weight as those 20 to 30 years ago did, even at the same levels of food intake and exercise.

The authors examined the dietary data of 36,400 Americans between 1971 and 2008 and the physical activity data of 14,419 people between 1988 and 2006. They grouped the data sets together by the amount of food and activity, age, and BMI.

They found a very surprising correlation: A given person, in 2006, eating the same amount of calories, taking in the same quantities of macronutrients like protein and fat, and exercising the same amount as a person of the same age did in 1988 would have a BMI that was about 2.3 points higher. In other words, people today are about 10 percent heavier than people were in the 1980s, even if they follow the exact same diet and exercise plans.

“Our study results suggest that if you are 25, you’d have to eat even less and exercise more than those older, to prevent gaining weight,” Jennifer Kuk, a professor of kinesiology and health science at Toronto’s York University, said in a statement. “However, it also indicates there may be other specific changes contributing to the rise in obesity beyond just diet and exercise.”

Just what those other changes might be, though, are still a matter of hypothesis. In an interview, Kuk proffered three different factors that might be making harder for adults today to stay thin.

First, people are exposed to more chemicals that might be weight-gain inducing. Pesticides, flame retardants, and the substances in food packaging might all be altering our hormonal processes and tweaking the way our bodies put on and maintain weight.

Second, the use of prescription drugs has risen dramatically since the ‘70s and ‘80s. Prozac, the first blockbuster SSRI, came out in 1988. Antidepressants are now one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the U.S., and many of them have been linked to weight gain.

Finally, Kuk and the other study authors think that the microbiomes of Americans might have somehow changed between the 1980s and now. It’s well known that some types of gut bacteria make a person more prone to weight gain and obesity. Americans are eating more meat than they were a few decades ago, and many animal products are treated with hormones and antibiotics in order to promote growth. All that meat might be changing gut bacteria in ways that are subtle, at first, but add up over time. Kuk believes the proliferation of artificial sweeteners could also be playing a role.

“There's a huge weight bias against people with obesity,” she said. “They're judged as lazy and self-indulgent. That's really not the case. If our research is correct, you need to eat even less and exercise even more” just to be same weight as your parents were at your age. ~

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/why-it-was-easier-to-be-skinny-in-the-1980s?utm_source=pocket-newtab

Oriana:

The importance of microbiome in regulating weight was revealed when fecal transplants came into use. A fecal transplant basically transfers the donor’s microbiome to the recipient. It turned out that a fecal transplant from an overweight person would make the recipient start gaining excess weight.

If you ever need a fecal transplant (which is a treatment of last resort), make sure that the donor is slender and in good physical and mental health. (Do schizophrenics have a different microbiome? Of course they do.)

Seriously, is there something you can do to improve your microbiome? Yes: avoid sugar and eat fermented foods such as sauerkraut and kimchi. Consume plenty of fiber to keep your gut microbes well-fed. Be good to your bacteria, and they'll be good to you.

*

BLOOD TYPE AND DISEASE RISK

Heart Attack and Heart Disease

It may seem obvious that your blood type is related to your heart, since your heart pumps blood to the rest of your body. But your blood type can actually put you at a higher risk for conditions such as heart attack and heart disease. This is because of a gene called the ABO gene — a gene that’s present in people with A, B, or AB blood types. The only blood type that doesn’t have this gene is Type O.

If you have the ABO gene and you live in an area with high pollution levels, you may be at a greater risk of heart attack than those who don’t have the gene.

Dr. Guggenheim said, “The ABO gene can also increase your risk of coronary artery disease (CAD). CAD develops when the arteries that supply blood to and from your heart harden and narrow — which can cause a heart attack if they become blocked.”

Brain Function and Memory Loss

The ABO gene is connected with brain function and memory loss. People who have blood types A, B, and AB are up to 82 percent more likely to develop cognition and memory problems — which can lead to dementia — compared to those with Type O.

One possible reason for this memory loss is the fact that blood type can lead to things like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes. These conditions can cause cognitive impairment and dementia.

Blood type has been connected with stroke, too, which can occur when the blood flow to the brain is disrupted.

Cancers

There are plenty of factors that have been connected with a higher risk of cancer, and it can sometimes be hard to know which ones to look into more seriously than others. However, people with Type A blood have been found to have a higher risk of stomach cancer specifically, compared to those with other blood types.

The ABO gene may play a role with a heightened cancer risk, as well. This gene has been connected to other cancers, including lung, breast, colorectal, prostate, liver, and cervical cancers. This correlation has been studied for more than 60 years, and while research continues to show a correlation, there is no definitive explanation as to why the ABO gene may put you at a higher risk for some cancers.

https://www.pennmedicine.org/updates/blogs/health-and-wellness/2019/april/blood-types

Oriana:

If you are type O, congratulations! that’s the blood type associated with the lowest risk of heart disease. Type O has the lowest levels of proteins associated with clotting. Type B and AB show the highest risk.

Type O also has the lowest risk of dementia, while type AB has the highest risk (but type AB is rare — only 4% of people have it).

If you are type A, B, or AB, you have a higher risk for pancreatic cancer, which is a truly infernal kind of cancer. (As for stomach cancer, it’s now rare in the Western countries.)

People who are type A tend to have high levels of cortisol, which is not good.

When it comes to covid-19 the O blood type wins again, having the lowest risk of infection in general.

It’s important to remember that the risk for any disease is multi-factorial. Smoking and obesity, a diet high in junk food and carcinogenic processed meat or meat cooked at high temperature, and the amount of exercise are typically better predictors than blood type alone. Still, if you have type O blood, I imagine you’re jubilant after reading this article — and positive emotions are certainly linked to better health.

*

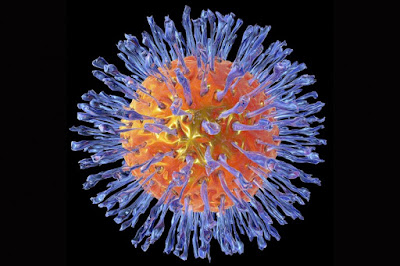

COLD SORES AND ALZHEIMER’S: HERPES VIRUS ASSOCIATED WITH DEMENTIA RISK

~ The virus implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1), is better known for causing cold sores. It infects most people in infancy and then remains dormant in the peripheral nervous system (the part of the nervous system that isn’t the brain and the spinal cord). Occasionally, if a person is stressed, the virus becomes activated and, in some people, it causes cold sores.

We discovered in 1991 that in many elderly people HSV1 is also present in the brain. And in 1997 we showed that it confers a strong risk of Alzheimer’s disease when present in the brain of people who have a specific gene known as APOE4.

The virus can become active in the brain, perhaps repeatedly, and this probably causes cumulative damage. The likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease is 12 times greater for APOE4 carriers who have HSV1 in the brain than for those with neither factor.

Later, we and others found that HSV1 infection of cell cultures causes beta-amyloid and abnormal tau proteins to accumulate. An accumulation of these proteins in the brain is characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease.

We believe that HSV1 is a major contributory factor for Alzheimer’s disease and that it enters the brains of elderly people as their immune system declines with age. It then establishes a latent (dormant) infection, from which it is reactivated by events such as stress, a reduced immune system and brain inflammation induced by infection by other microbes.

Reactivation leads to direct viral damage in infected cells and to viral-induced inflammation. We suggest that repeated activation causes cumulative damage, leading eventually to Alzheimer’s disease in people with the APOE4 gene.

Presumably, in APOE4 carriers, Alzheimer’s disease develops in the brain because of greater HSV1-induced formation of toxic products, or less repair of damage.

In an earlier study, we found that the anti-herpes antiviral drug, acyclovir, blocks HSV1 DNA replication, and reduces levels of beta-amyloid and tau caused by HSV1 infection of cell cultures.

It’s important to note that all studies, including our own, only show an association between the herpes virus and Alzheimer’s – they don’t prove that the virus is an actual cause. Probably the only way to prove that a microbe is a cause of a disease is to show that an occurrence of the disease is greatly reduced either by targeting the microbe with a specific anti-microbial agent or by specific vaccination against the microbe.

Excitingly, successful prevention of Alzheimer’s disease by use of specific anti-herpes agents has now been demonstrated in a large-scale population study in Taiwan. Hopefully, information in other countries, if available, will yield similar results. ~

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20181022-there-is-mounting-evidence-that-herpes-leads-to-alzheimers

*

VIRUS THEORY OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

~ Schizophrenia is a severely debilitating mental illness with no known cause or cure, although there is a strong genetic correlation. Interestingly, there is additionally a significant relationship between season of birth and the development of schizophrenia, as individuals born during late winter and spring have a significantly increased risk for developing schizophrenia. One hypothesis to explain this phenomenon is that this is due to prenatal viral infection, which is more likely to occur in the winter months. It is hypothesized that viral infections occurring during the third trimester of pregnancy result in the increased risk for developing schizophrenia. However, there is currently debate as to how this happens— is it due to a direct viral infection of the fetus, or due to maternal cytokines in response to infection?”

A study by Faterni et al (2012) found that the placenta may be a site of pathology in viral infections. Using pregnant mice infected with a sublethal dose of influenza on the seventh day of pregnancy (E7), they found that viral infection resulted in many histological abnormalities in the placentae. These abnormalities included an absence of the labyrinth zone, the region of the maternal placenta in which nutrients and oxygen are exchanged between the maternal and fetal blood, the presence of thrombi, and an increased number of inflammatory cells.

The deletion of a labyrinth zone could result in a reduction of oxygen delivered to the developing fetus and result in neural abnormalities, which may be ultimately caused by an inflammatory immune response.

Importantly, H1N1 viral genes were not detected in either the placenta or brains of offspring whose mothers were infected, suggesting that the virus did not cross the placenta to directly infect the offspring. This consequently implicates that the changes found in gene expression as well as the structural abnormalities of the placenta were most likely due to the production of maternal or fetal cytokines, most likely due to an increase in inflammatory cells in infected placenta. ~

https://pages.vassar.edu/viva/?p=918

~ The results of the study by Brown et al revealed a dramatic 7-fold increase in the risk of schizophrenia among the offspring of women who were exposed to influenza during their first trimester of pregnancy. Further analysis suggested a 3-fold increase of risk in women who were exposed to influenza from the midpoints of their first and second trimesters. ~

(Brown AS, Begg MD, Gravenstein S, et al. Serologic evidence of prenatal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):774-78015289276)

HERPES AND SCHIZOPHRENIA?

~ [A recent] study evaluated pregnant women between 1959 and 1966 and identified 27 surviving offspring who were later diagnosed with schizophrenia. Analysis of stored blood samples showed an association between high levels of maternal antibody to HSV-2 and subsequent development of adult psychosis. No association was found between HSV-1 infection and psychosis. There is also evidence that human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) may play a role in schizophrenia, as antibodies to these agents have been found at a greater frequency in the sera of affected individuals compared with controls. This is supported by the presence of reverse transcriptase, a retroviral marker, at levels four times higher in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of people with recent onset schizophrenia compared with controls, and by its elevated presence in long-term schizophrenic patients. ~

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15319094/

Note: HSV-1 is the virus that causes cold sores. HSV-2 is the genital herpes. HSV-1 can cause genital herpes, but most cases are due to HSV-2.

Oriana:

It’s possible that the kind of virus doesn’t really matter; what matters is that the pregnant woman experienced an infection and acute inflammation.

Schizophrenia remains a mystery, and no one claims that viral infection during pregnancy directly causes schizophrenia in the offspring; case solved. But we can’t exclude the possibility that a virus may be involved in at least some cases of schizophrenia.

*

ending on beauty:

time makes pebbles of us all,

smooth and rounded to perfection

though we once were hard-edged,

angry chunks of rock

~ Magdalena Paśnikowska